Abstract

Background

College students are at increased risk for invasive meningococcal disease, but which students are most at risk is unclear.

Methods

US meningococcal disease cases in persons aged 18–24 years during 2014–2017 were included. Patients were classified as undergraduate students or other persons. Incidence in different student and non-student populations was compared.

Results

During 2014–2017, 229 meningococcal disease cases were reported in persons aged 18–24 years; 120 were in undergraduate students. Serogroup B accounted for 74% of cases in students. Serogroup B disease incidence was 4-fold higher in undergraduate students, 11.8-fold higher among first-year undergraduate students, and 8.6-fold higher among residence hall residents versus non-undergraduates. During outbreaks, students affiliated with Greek life had a 9.8-fold higher risk of disease compared to other students. A significantly higher party school ranking was observed for schools with sporadic or outbreak cases when compared to schools with no cases.

Conclusions

The findings of increased disease risk among first-year students and those living on campus or affiliated with Greek life can inform shared clinical decision-making for serogroup B vaccines to prevent this rare but serious disease. These data also can inform school serogroup B vaccination policies and outbreak response measures.

Keywords: Meningococcal disease, MenB vaccine, College students

This study identifies risk factors for serogroup B meningococcal disease among college students and considers how healthcare providers and schools might use them to prevent disease.

Meningococcal disease, caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis, is a rare but serious illness with a 10%–15% case-fatality ratio. Another 10%–20% of survivors may have long-term sequelae [1, 2]. The pathogen is spread through respiratory droplets between people who have close or lengthy contact with one another. Since the late 1990s, the incidence of meningococcal disease in the United States (US) has steadily declined [3]. Although the overall incidence of meningococcal disease is low, young adults remain at increased risk of disease predominantly caused by serogroup B [4]. The risk of serogroup B disease in young adults aged 18–24 years is approximately 3-fold higher in college students compared to non–college students [5]. In addition, during 2013–2018, 10 college-based outbreaks of serogroup B disease were reported [6].

Quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate (MenACWY) vaccine is routinely recommended for all adolescents at age 11–12 years with a booster dose at age 16 years. In contrast, serogroup B meningococcal (MenB) vaccine is recommended for young adults aged 16–23 years based on shared clinical decision-making, with a preferred age of 16–18 years [7]. Although the recommendation for shared clinical decision-making gives patients and providers flexibility in determining the best approach for each patient, providers have found this recommendation challenging to implement due to confusion about insurance coverage and how to explain the recommendation to patients [8]. In addition, although limited guidance on factors to consider as part of shared clinical decision-making has been published [7], there is little evidence available to inform the shared clinical decision-making process and assess which adolescents would benefit most from vaccination.

Both MenACWY and MenB vaccines are also recommended for groups at increased risk for meningococcal disease, including persons at risk during an outbreak [7]. MenB vaccination campaigns have been used in college serogroup B outbreaks with campaigns conducted at most of the affected schools [6]. However, achieving high MenB vaccine coverage during outbreaks has been challenging, especially for large schools. While some colleges have attempted to prioritize vaccination efforts among groups perceived to be at increased risk, the small size of most university meningococcal disease outbreaks (range, 2–9 cases) [6] makes it difficult to determine risk factors for disease within any given outbreak. Information on risk factors for meningococcal disease observed across college outbreaks would be valuable to inform priority groups for vaccination in future outbreaks.

In the 1990s, evaluations showed that college students residing in dormitories, particularly first-year students, were at increased risk for meningococcal disease in the US [9, 10]. Greek life association and partying have been shown to be risk factors among students at least during outbreaks [11, 12]. However, most of these studies describe cases predominantly due to serogroup C, not B, and occurred in a setting of 8- to 10-fold higher overall meningococcal disease incidence. Given both the large changes in meningococcal disease epidemiology and significant societal changes over the past several decades, there is a need to reassess meningococcal disease risk factors among college students. We therefore characterized potential factors associated with increased risk for meningococcal disease related to both sporadic and outbreak cases among college students during 2014–2017. This analysis may help to inform shared clinical decision-making for serogroup B vaccine use in adolescents, targeted prevention and response measures during outbreaks in schools, and vaccination policies for matriculating students.

METHODS

Surveillance

Meningococcal disease surveillance data are routinely reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). All confirmed and probable meningococcal disease cases in persons aged 18–24 years reported to NNDSS between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2017 were included in this analysis. Cases were defined as confirmed or probable according to the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists’ surveillance case definition [13, 14]. In brief, confirmed cases included those with detection of N meningitidis by polymerase chain reaction or culture from a normally sterile body site, while probable cases included those with N meningitidis detected through immunohistochemistry in fixed tissue or latex agglutination in cerebrospinal fluid [13]. Patients with meningococcal disease were classified as either undergraduate students or all other persons in this age group (hereafter called non-undergraduate students) as part of enhanced meningococcal disease surveillance activities. For cases determined to have occurred in undergraduate students, jurisdictions submitted supplemental information to CDC, including the student's school name and type of school (4-year or 2-year); student's class year, extracurricular participation, and residence type; and whether the case was associated with an outbreak. For this analysis, outbreaks were defined as ≥2 cases caused by the same meningococcal strain and associated with a single college in a 3-month period [15]. All other cases were classified as sporadic.

Denominator Data for Risk Calculations

Denominator data were obtained from multiple sources, including the National Center for Education Statistics, US Census, and several independent organizations such as the College Board and Princeton Review that conduct routine surveys of colleges (Supplementary Table 1). While there are in some cases other organizations that also collect and report similar data, we selected these specific data sources as they included data that were comprehensive, freely available, and categorized and tabulated in a way that aligned with the available meningococcal case data and specific analytic questions.

To estimate relative risk of meningococcal disease in undergraduate college students versus non-undergraduate students, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Digest of Education Statistics was used to estimate the total number of undergraduate students aged 18–24 years enrolled in 4-year and 2-year colleges in 2015 and 2017. NCES denominator data were only available for these 2 years, so we estimated the number of undergraduate students for the other years of the analytic period using the 2015 data (because those data are likely similar to 2014 and 2016) as previously described [5]. In brief, we first divided the total undergraduate student population for 2015 (NCES data) by the 2015 census estimates [16] for persons aged 18–24 years. The proportion of undergraduate students was then multiplied by the annual census estimates of the total number of persons aged 18–24 years to obtain the estimated number of undergraduate students for 2014 and 2016.

To calculate the relative risk by class year among 4-year college students, the 2018 NCES survey provided the number of first-time degree-seeking students attending 4-year colleges during 2014–2017. First-time degree-seeking students were used as a proxy for first-year college students.

To estimate the relative risk by residence type, College Board data from 2015–2016 [17] were used to estimate the number of undergraduate college students living on campus among 4-year students attending public (36%), private nonprofit (58%), and private for-profit (3%) colleges. These percentages were multiplied by the total of undergraduate students for each category from the NCES data and summed to estimate the total number of undergraduate students living on campus.

To calculate denominators for outbreak-related cases, NCES school-level enrollment data were obtained for first-time degree-seeking students and total undergraduate students for the specific schools affected by outbreaks during the year each outbreak was reported. Estimates for the number of students living on campus and participating in Greek life for each school were obtained from school websites, Princeton Review, and/or U.S. News & World Report. To calculate the number of undergraduate students living on campus, the percentage of undergraduates living on campus was multiplied by the total number of undergraduate students. For Greek life, data were reported as the percentage of students affiliated with sororities and fraternities. To determine the overall number of students participating in Greek life for each school, NCES data were used to determine the number of males and females at each school. The percentage of female students participating in sororities was then multiplied by the total number of female students, and this process was repeated for male students in fraternities. Because of a high percentage of missing data for Greek life participation among sporadic cases, incidence among Greek versus non-Greek students could only be assessed in outbreak settings.

School-Level Analysis

To assess whether school characteristics are associated with increased risk of having a meningococcal disease case or an outbreak at that school, we compared school-level data for schools that experienced sporadic serogroup B cases (48 schools), serogroup B outbreaks (8 schools), and no meningococcal disease cases (100 schools). We created the comparison group of 100 colleges with no reported meningococcal disease cases during 2014–2017 by using the NCES College Navigator tool to first generate a list of 2251 public and private nonprofit 4-year schools. Colleges were then randomly selected from this list using a computer-based random number generator. Selected colleges were excluded, and a replacement school chosen at random, if the selected college had a sporadic case or outbreak during 2014–2017, the campus was permanently closed, additional information (eg, percentage of students living on campus) could not be obtained, or the college offered only online courses. As described above, school websites, Princeton Review, and U.S. News & World Report were used to determine the type of school (public, private), student body size, the percentage of undergraduate students living on campus, and the percentage affiliated with Greek life. School-level data on party school ranking were obtained from the website www.niche.com. Rankings were reported as letter grades (eg, A+, A, A−). A number ranging from 0 to 9 was assigned to each letter grade from A+ (9) to D+ (0).

Statistical Methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using R 4.1.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) software. The incidence of meningococcal disease overall and by serogroup was calculated for all undergraduate students, undergraduate students attending 4-year and 2-year schools, and non-undergraduate students. We assumed that point estimates of denominator sizes remained relatively constant during any given year and could therefore be used to calculate person time.

Multiple imputation was used to fill in missing data for class year and residence type for cases of serogroup B disease in students attending 4-year colleges. Multiple imputation was conducted using fully conditional specification with the patient's age in years and the percentage of all undergraduates and freshmen living on campus at the patient's school used to inform the imputation.

Poisson regression with robust standard errors was performed to estimate the relative risk associated with Greek life participation, class year, and on-campus residence, with generalized estimating equations for outbreak cases to account for within-cluster correlations. Differences (P < .05) among characteristics of schools that had sporadic, outbreak, or no meningococcal disease cases were assessed using 1-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey posttest (residence type, Greek life), Wilcoxon signed-rank test (party school ranking), Poisson regression (private vs public), and Wilcoxon rank-sum test (median number of students).

RESULTS

During 2014–2017, 229 confirmed and probable meningococcal disease cases were reported in persons aged 18–24 years in the United States for an incidence rate of 0.18 per 100 000 person-years. Of these, 226 (99%) had known college status; 120 of 226 (53%) were undergraduate college students. Serogroup information was available for 116 of 120 (97%) of these cases. The incidence in undergraduate students (0.27) was >2 times higher than in non-undergraduate students (0.13). This increased risk of disease was observed only among undergraduate students attending 4-year colleges. Two-year college students did not have an elevated risk of disease compared to non-undergraduate students (Table 1).

Table 1.

Incidence and Relative Risk of Meningococcal Disease Cases by Serogroup in Undergraduates and Non-undergraduates Aged 18–24 Years—United States, 2014–2017

| Characteristic | All Serogroups | Serogroup B | Other Serogroupsa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cases | Incidenceb | RR (95% CI) | Cases | Incidence | RR (95% CI) | Cases | Incidence | RR (95% CI) | |

| All 18–24 y | 226 | 0.18 | … | 129 | 0.10 | … | 97 | 0.08 | … |

| Non-undergraduate | 106 | 0.13 | Ref | 40 | 0.05 | Ref | 67 | 0.08 | Ref |

| Undergraduate | 120 | 0.27 | 2.04 (1.57–2.66) | 89 | 0.20 | 4.01 (2.79–5.89) | 30 | 0.07 | 0.81 (.52–1.23) |

| 4-year | 105 | 0.34 | 2.59 (1.98–3.39) | 80 | 0.26 | 5.23 (3.60–7.72) | 24 | 0.08 | 0.94 (.58–1.47) |

| 2-year | 12 | 0.09 | 0.66 (.34–1.15) | 7 | 0.05 | 1.02 (.42–2.13) | 5 | 0.04 | 0.43 (.15–.97) |

| Missing | 3 | … | … | 2 | … | … | 1 | … | … |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

aOther serogroups in undergraduate students: C = 4, W = 3, Y = 7, nongroupable = 12, missing = 4.

bCases per 100 000 person-years.

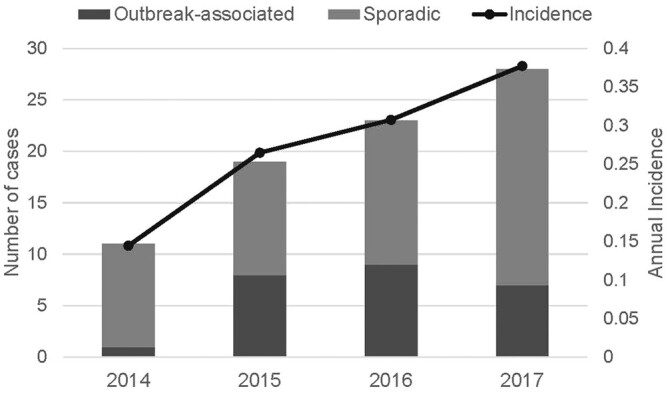

Serogroup B disease accounted for 89 of 120 (74%) of cases in undergraduate students. The overall incidence of serogroup B disease in undergraduate students was 4 times higher than the incidence in non-undergraduates. This elevated risk was seen only in undergraduate students attending 4-year colleges (Table 1). Annual incidence rate of serogroup B disease in undergraduate students attending 4-year colleges increased during the evaluation period from 0.14 cases per 100 000 in 2014 to 0.38 cases per 100 000 person-years during 2017 (Figure 1). For all other serogroups combined (C, W, Y, nongroupable, and missing), similar incidence was observed in undergraduate and non-undergraduate students (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Number of serogroup B disease cases classified as sporadic or outbreak-associated and annual incidence by year—United States, 2014–2017. The one 2014 outbreak case was a college student, but the student did not attend the school where the outbreak occurred, so this case was not included in the outbreak analyses in this manuscript.

Of the 80 serogroup B cases among 4-year college students, 30% were associated with a college outbreak in 8 schools and 70% were sporadic cases in 48 schools. Overall, 65% of serogroup B cases were reported in patients aged 18–19 years, including 59% of sporadic cases and 79% of outbreak cases (Table 2). First-year undergraduate students were 3.8 times more likely to develop serogroup B disease than non-first-year students. These students had increased risk for sporadic disease and for developing disease as part of an outbreak compared to their upper-class counterparts (Table 3). A majority of patients with either sporadic or outbreak-associated meningococcal disease lived on campus (Table 2). The risk of serogroup B disease for students who lived on campus was 2.9 times higher than for those who did not live on campus and was higher both for sporadic cases and outbreak cases (Table 3). Serogroup B incidence was 11.8 times higher among first-year undergraduate students than in non-undergraduates and 8.6 times higher among residence hall residents versus non-undergraduates. Among outbreak cases, 54% were in students affiliated with Greek life, giving them a 9.8 times higher risk of infection compared to students not affiliated with Greek life (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Serogroup B Disease Cases Among Undergraduate Students Attending 4-Year Colleges in the United States, 2014–2017a

| Characteristic | All Serogroup B | Sporadic | Outbreak-Associatedb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cases | 80 (100) | 56 (100) | 24 (100) |

| Age, y | |||

| 18–19 | 52 (65) | 33 (59) | 19 (79) |

| 20–21 | 24 (30) | 19 (34) | 5 (21) |

| 22–24 | 4 (5) | 4 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Class year | |||

| First-year | 30 (38) | 14 (25) | 16 (67) |

| Non-first-year | 23 (29) | 15 (27) | 8 (33) |

| Missing | 27 (34) | 27 (48) | 0 (0) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 31 (39) | 16 (29) | 15 (63) |

| Female | 49 (61) | 40 (71) | 9 (38) |

| Race | |||

| White | 62 (78) | 46 (82) | 16 (67) |

| Black | 6 (8) | 3 (5) | 3 (13) |

| Asian | 3 (4) | 2 (4) | 1 (4) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2 or more races | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 8 (10) | 4 (7) | 4 (17) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 5 (6) | 3 (5) | 2 (8) |

| Non-Hispanic | 63 (79) | 46 (82) | 17 (71) |

| Missing | 12 (15) | 7 (13) | 5 (21) |

| Residence type | |||

| On campus/residence halls | 50 (63) | 33 (59) | 17 (71) |

| Off campus | 23 (29) | 16 (29) | 7 (29) |

| Missing | 7 (9) | 7 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Greek life participation | |||

| Yes | 23 (29) | 10 (18) | 13 (54) |

| No | 16 (20) | 5 (9) | 11 (46) |

| Missing | 41 (51) | 41 (73) | 0 (0) |

Data are presented as No. (%).

aSome percentages do not sum to 100% due to rounding.

bOne outbreak case was a college student, but the student did not attend the school where the outbreak occurred, so this case was not included in the outbreak analyses in this manuscript.

Table 3.

Incidence and Relative Risk of Serogroup B Disease in Undergraduate Students by Class Year, Residence Type, and Greek Life Participation—United States, 2014–2017

| Characteristic | All Serogroup B | Sporadic | Outbreak-Associateda | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidenceb,c | RR (95% CI) | Incidenceb,c | RR (95% CI) | Incidenceb,d | RRe (95% CI) | |

| Class year | ||||||

| First-year | 0.59 | 3.76 (2.35–6.01) | 0.37 | 3.03 (1.70–5.38) | 54.98 | 8.22 (5.65–11.95) |

| Non-first-year | 0.16 | Ref | 0.12 | Ref | 6.62 | Ref |

| Residence type | ||||||

| On campus | 0.43 | 2.88 (1.80–4.63) | 0.29 | 2.66 (1.52–4.67) | 30.45 | 4.47 (2.82–7.07) |

| Off campus | 0.15 | Ref | 0.11 | Ref | 7.44 | Ref |

| Greek life participationf | ||||||

| Yes | … | … | … | … | 71.68 | 9.84 (4.57–21.18) |

| No | … | … | … | … | 8.35 | Ref |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

a2014 outbreak case was not included in analyses.

bCases per 100 000 person-years.

cTotal number of undergraduate students in the United States used to calculate denominators.

dTotal number of undergraduate students at schools with outbreaks used to calculate denominators.

eRR calculated by Poisson regression using generalized estimating equations to account for clustering by school.

fCould not calculate Greek life participation for sporadic cases.

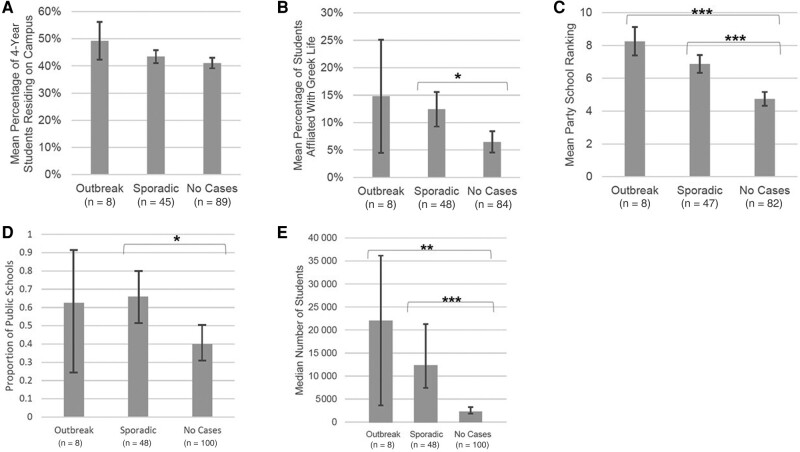

There was no difference in the mean percentage of students living on campus between schools with sporadic cases, outbreak cases, and no cases (Figure 2). Colleges with sporadic cases had a significantly higher percentage of students participating in Greek life when compared to colleges with no cases (P < .05) (Figure 2). A significantly higher mean party school ranking (P < .05) was observed for colleges with either sporadic or outbreak cases when compared to colleges with no meningococcal disease cases. Schools with sporadic cases were significantly more likely to be public schools when compared to schools with no cases (P < .05) (Figure 2). Finally, schools with sporadic cases and outbreak cases had significantly larger undergraduate populations compared to schools with no cases (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Characteristics of colleges with serogroup B disease outbreaks (8 schools), sporadic cases (48 schools), and without serogroup B disease cases (100 schools)—United States, 2014–2017a,b. A, Mean percentage of 4-year students residing on campusc. B, Mean percentage of students affiliated with Greek lifec. C, Mean college party school rankingsd. D, Proportion of public colleges per college categorye. E, Median number of undergraduate studentsf. Notes: aSchools where the characteristic could not be determined were excluded from the analysis. Of the 56 college students with sporadic serogroup B disease, 7 students came from 3 colleges; 3 others had an unknown school name and were therefore excluded from this analysis. bComparisons are between outbreaks and no cases and sporadic and no cases. Vertical error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals, and horizontal brackets with asterisks identify comparisons that are statistically significant at P < .05. cAnalysis of variance test. dWilcoxon signed-rank test. ePoisson regression. fWilcoxon rank-sum test. *P < .05; **P < .001; ***P < .0001.

DISCUSSION

While the overall incidence of meningococcal disease in the US is low and only 56 colleges were affected, undergraduate college students aged 18–24 years attending 4-year colleges are at increased risk for serogroup B disease. The majority of cases occurred in students aged 18–19 years, students living on campus, and, for outbreak cases, students with Greek life affiliation. Certain characteristics of colleges were associated with having sporadic cases, outbreaks, or both, including being public schools, having large undergraduate student bodies, having a high percentage of students affiliated with Greek life, and having a high party school ranking. These findings help define which college students are at highest risk for serogroup B disease and may therefore have a more favorable balance of costs and benefits when considering serogroup B vaccination.

These higher risk groups share a few important characteristics. First-year students and Greek life participants frequently live in communal housing, where close contact is common. Similarly, students attending 4-year schools tend to have more opportunities for communal living arrangements and more often attract students from different regions of the country where unique strains of N meningitidis might be circulating. This could increase the likelihood of exposure of naive populations to new strains. Close contact in shared bedrooms, bathrooms, and dining halls, as well as during parties, creates ample opportunity for pathogen transmission from asymptomatic carriers.

These findings might be useful for patients, parents, and clinicians when discussing whether to vaccinate adolescents against serogroup B before they go to college. Adolescents planning to live on campus at a 4-year college, particularly ones planning to engage in Greek life or attend schools known for their social life, may benefit more from vaccination. Immunity from MenB vaccines is known to wane quickly [7], but concentration of risk among first-year college students means there is an opportunity to prevent relatively more disease by vaccinating students shortly before they go to college so that the timing of maximum protection overlaps with the highest period of risk. As of 2021, only 31% of 17-year-olds received the first dose of MenB vaccine [18], and it is likely that only about half of those young adults received the second dose, which is needed to complete the series [19]. Only receiving the first dose does not provide the maximum protection afforded by vaccination, so our findings also might be helpful to clinicians when they are explaining to patients and parents why it is important to complete the MenB series.

After MenB vaccines became available in the US in 2015, some colleges began recommending or requiring vaccination for all incoming first-year students [20]. Requiring or recommending vaccination against serogroup B disease might not be a tenable policy decision for all colleges, but our findings suggest that 4-year colleges with large numbers of students participating in Greek life or with a high party school ranking might be most likely to benefit from such policies, as these schools were significantly more likely to experience serogroup B cases or outbreaks. If a serogroup B outbreak were to occur, affected colleges could target their vaccination efforts to students with the highest risk for disease, particularly during the early stages of a response when the scope of the outbreak might not yet be fully understood or during small outbreaks when specific risk factors cannot be identified. Administrators could host vaccination events at freshman residence halls or in the Greek life areas of campus to hopefully increase vaccine coverage among these student populations.

This analysis has the following limitations. First, the data for college students living on campus and participating in Greek life as well as party school ranking were collected from multiple sources and were not specifically collected for this analysis. While these data sources appear reliable based on publicly available methodology information [21–23] and comparison with individual school websites, the details of the data collection and therefore validity of these data are ultimately unknown. Second, NCES data from adjacent years were used to calculate undergraduate student totals for 2014 and 2016; this could result in incorrect estimates, but we would not expect it to substantially affect the conclusions of our analysis. Third, the analysis is limited by the high percentage of missing data for Greek life participation, especially among sporadic cases, which prevented an assessment of whether Greek life participation was associated with sporadic illness. Fourth, student class year and residence type were missing for many of the patients and had to be imputed based on student age and other variables, so there could be some misclassification of these 2 variables. Fifth, this analysis considers a period from before the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Meningococcal disease incidence in the US declined sharply during the pandemic and there were no reported meningococcal disease college outbreaks. We have no reason to think, however, that the risk factors have become substantially different compared with prior to the pandemic now that most physical distancing measures have ended.

These limitations notwithstanding, this analysis helps clarify our understanding of the risk factors for serogroup B disease among college students, specifically those in their first-year of school, those who reside in dormitories, and those who attend large schools with prominent Greek life. These findings can support additional efforts to prevent disease among this population, including provider and patient education on factors increasing disease risk that can inform discussions about MenB vaccination. These data can also inform school decisions on whether to institute MenB vaccination recommendations or requirements and targeted vaccine response measures during outbreaks in schools.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Lauren M Weil, Epidemic Intelligence Service Program, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA; Division of Bacterial Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Samuel J Crowe, Division of Bacterial Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Amy B Rubis, Division of Bacterial Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Heidi M Soeters, Division of Bacterial Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Sarah A Meyer, Division of Bacterial Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Susan Hariri, Division of Bacterial Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Lucy A McNamara, Division of Bacterial Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. L. M. W., S. J. C., and L. A. M. analyzed the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. A. B. R. collected the data, carried out initial analyses, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. H. M. S., S. A. M., and S. H. helped design the study and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Patient consent. This study does not include factors necessitating patient consent.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1. Pace D, Pollard AJ. Meningococcal disease: clinical presentation and sequelae. Vaccine 2012; 30(Suppl 2):B3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacNeil JR, Blain AE, Wang X, Cohn AC. Current epidemiology and trends in meningococcal disease—United States, 1996–2015. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:1276–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Meningococcal disease surveillance. 2022. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/surveillance/index.html. Accessed 9 February 2023.

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Enhanced meningococcal disease surveillance report, 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/downloads/ncird-ems-report-2018.pdf. Accessed 9 February 2023.

- 5. Mbaeyi SA, Joseph SJ, Blain A, Wang X, Hariri S, MacNeil JR. Meningococcal disease among college-aged young adults: 2014–2016. Pediatrics 2019; 143:e20182130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Soeters HM, McNamara LA, Blain AE, et al. University-based outbreaks of meningococcal disease caused by serogroup B, United States, 2013–2018. Emerg Infect Dis 2019; 25:434–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mbaeyi SA, Bozio CH, Duffy J, et al. Meningococcal vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep 2020; 69(No. RR-9):1–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kempe A, Allison MA, MacNeil JR, et al. Knowledge and attitudes regarding category B ACIP recommendations among primary care providers for children. Acad Pediatr 2018; 18:763–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harrison LH, Dwyer DM, Maples CT, Billmann L. Risk of meningococcal infection in college students. JAMA 1999; 281:1906–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bruce MG, Rosenstein NE, Capparella JM, Shutt KA, Perkins BA, Collins M. Risk factors for meningococcal disease in college students. JAMA 2001; 286:688–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mandal S, Wu HM, MacNeil JR, et al. Prolonged university outbreak of meningococcal disease associated with a serogroup B strain rarely seen in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:344–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Imrey PB, Jackson LA, Ludwinski PH, et al. Outbreak of serogroup C meningococcal disease associated with campus bar patronage. Am J Epidemiol 1996; 143:624–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Meningococcal disease (Neisseria meningitidis) 2015 case definition. Available at: https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/meningococcal-disease-2015/. Accessed 9 February 2023.

- 14. Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists . Revision of the national surveillance case definition for meningococcal disease. Available at: https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cste.org/resource/resmgr/2014PS/14_ID_06upd.pdf. Accessed 9 February 2023.

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Guidance for the evaluation and public health management of suspected outbreaks of meningococcal disease. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/downloads/meningococcal-outbreak-guidance.pdf. Accessed 9 February 2023.

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Bridged-race population estimates, United States, July 1st resident population by state, county, age, sex, bridged-race, and Hispanic origin, on CDC WONDER online database. Available at: https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/datarequest/D143;jsessionid=1B0414E219B6FCA7759271D7A010. Accessed 9 February 2023.

- 17. College Board . Trends in college pricing 2018. Available at: https://research.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/trends-college-pricing-2018-full-report.pdf. Accessed 9 February 2023.

- 18. Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—National Immunization Survey–Teen, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71:1101–08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Packnett E, Irwin DE, Novy P, et al. Meningococcal-group B (MenB) vaccine series completion and adherence to dosing schedule in the United States: a retrospective analysis by vaccine and payer type. Vaccine 2019; 37:5899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oliver SE, Patton ME, Hoban M, et al. Evaluation of meningococcal vaccination policies among colleges and universities—United States, 2017. J Am Coll Health 2021; 69:554–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niche . The top party schools methodology. Available at: https://www.niche.com/about/methodology/top-party-schools/. Accessed 21 August 2023.

- 22. U.S. News & World Report . How U.S. News calculated the 2022–2023 best colleges rankings. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/how-us-news-calculated-the-rankings. Accessed 21 August 2023.

- 23. College Board . Trends in college pricing 2018. Available at: https://research.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/trends-college-pricing-2018-full-report.pdf. Accessed 21 August 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.