Abstract

Objectives

imPROVE is a new Health Information Technology platform that enables systematic patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) collection through a mobile phone application. The purpose of this study is to describe our initial experience and approach to implementing imPROVE among breast cancer patients treated in breast and plastic surgery clinics.

Materials and Methods

We describe our initial implementation in 4 phases between June 2021 and February 2022: preimplementation, followed by 3 consecutive implementation periods (P1, P2, P3). The Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies statement guided this study. Iterative Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles supported implementation, and success was evaluated using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance framework.

Results

Qualitative interviews conducted during the preimplementation phase elicited 4 perceived implementation barriers. Further feedback collected during each phase of implementation resulted in the development of brochures, posters in clinic spaces, and scripts for clinic staff to streamline discussions with patients, and the resolution of technical issues concerning patient login capabilities, such as compatibility with cell phone software and barriers to downloading imPROVE. Feedback also generated ideas for facilitating provider interpretation of PROM results. By the end of P3, 2961 patients were eligible, 1375 (46.4%) downloaded imPROVE, and 1070 (36.1% of those eligible, 78% of those who downloaded) completed at least 1 PROM.

Discussion and Conclusion

Implementation efforts across 2 surgical departments at 2 academic teaching hospitals enabled collaboration across clinical specialties and longitudinal PROM reporting for patients receiving breast cancer care; the implementation effort also highlighted patient difficulties with mobile app-based PROM collection, particularly around initial engagement.

Keywords: improve, breast cancer, implementation, patient-reported outcomes, clinical care

Introduction

Improving healthcare quality depends on the clinician’s ability to address concerns that are most important to patients. While metrics such as morbidity and mortality have traditionally taken precedence in evaluating patient outcomes, there has been an increasing emphasis on obtaining information directly from patients related to their quality of life (QOL). Current standards for physician-patient encounters and medical tests do not consistently evaluate nor do they address QOL outcomes, with physicians often underestimating the severity of symptoms.1

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) enable clinicians to understand QOL outcomes, such as physical and psychosocial well-being and satisfaction with care, from the patient’s perspective.2 While PROMs have traditionally been used in research,3 their use in routine clinical care enhances the quality of care delivered to patients, clinician–patient interactions, and patient outcomes.3–10 In addition, routine PROM collection enables more accurate symptom measurement.11–18 For this reason, there is increasing interest in using PROMs to inform care delivery.19

Despite the appeal of incorporating PROM collection in routine clinical care, several challenges prevail, limiting their uptake and use. First, the perceived value of PROMs is not unanimous. Negative perceptions of PROMs and the lack of knowledge about their positive impact on care delivery can impede their successful uptake and use. Second, there is no transferrable tool available to support real-time collection, storing, analyzing, or reporting PROMs.20,21 Third, existing platforms and electronic health records (EHR) currently supporting the collection of PROMs are widely underutilized due to their inability to meet the providers’ information needs and poor integration and synchronization with the EHR.22 Finally, successful and sustainable PROM implementation initiatives have been difficult to achieve.22 Some studies report a lack of time to appropriately integrate PROMs into clinical practice as a barrier to their use.22

In recognizing the value of PROM collection in routine clinical care, our team recently developed a new Health Information Technology (HIT) platform called imPROVE, which enables the systematic collection of PROMs through a mobile phone application (app).23 imPROVE was designed and developed using best practices in user-centered design, agile development, and qualitative methods described in detail elsewhere.23 In this article, we describe our initial experience and approach to implementing imPROVE among patients in breast and plastic surgery clinics over 9 months. We present recruitment and completion rates and key barriers and facilitators to implementation.

Methods

imPROVE

imPROVE is a mobile application wherein patients can complete PROMs, view their results over time, and receive links to tailored resources (support groups, informational videos about surgery, etc.). imPROVE also has a clinician dashboard component wherein providers can view individual patient profiles with their PROM data displays and links to patient resources.23 imPROVE incorporates the breast cancer standard outcome set of the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM)24,25 and the complete BREAST-Q Breast Cancer Module.26 Algorithms for PROM scoring are embedded within the application. PROMs are administered preoperatively and postoperatively at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and every 6 months thereafter, as per ICHOM recommendations.24,25 Patients can also complete PROMs at any time on demand.

Implementation and study design

The Standards for Reporting Implementation (StaRI) Studies statement27 guided this study. We describe our initial implementation in 4 phases: preimplementation, and 3 consecutive implementation periods (P1, P2, P3) between June 2021 and February 2022, and each implementation period spanned 3 months. We implemented imPROVE in breast and plastic surgery clinics at 2 academic hospitals (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute [DFCI] and Brigham and Women’s [BWH]), consisting of 4 separate sites.

During the preimplementation phase, a trained qualitative researcher conducted 1-h qualitative interviews with a breast surgeon, administrative assistant, nurse practitioner, and a plastic surgery research staff member involved in prior PROM implementation initiatives. The interviewer used a semi-structured guide to probe each participant about clinic workflows, their perceived value of PROMs, and potential barriers to PROM implementation. Interviews were audiorecorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded inductively within Microsoft Word (2020) using top-level domains and themes. A qualitative description was used to guide the analysis.28,29

We used findings from the preimplementation phase to design our initial implementation strategy. Implementation was supported by iterative Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles,30 involving weekly (plastic surgery) and biweekly (breast surgery) meetings led by the imPROVE project manager. The meetings consisted of the core project team (including information technology support that maintained active communication with the software vendor), breast and plastic surgery “clinic champions” (dedicated staff who raised awareness and served as points of contact in clinics), and research assistants. Within meetings, we reviewed enrollment and PROM completion trends, discussed implementation challenges, and planned strategies for the coming week(s). We developed tableau dashboards to monitor implementation success, including data displays of patient enrollment, activation, and PROM completion rates.

The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework31,32 guided the evaluation of implementation success, defined as obtaining activation and PROM completion rates of 70% or higher. For the present study, reach, effectiveness, and adoption were evaluated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primary outcomes to evaluate reach, effectiveness, and adoption.

| RE-AIM domain | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Reach |

|

| Effectiveness |

|

| Adoption |

|

| |

|

This study was a quality improvement initiative at BWH and DFCI and was not formally supervised by their Institutional Review Board, per their policies. No formal consent was obtained; patients were informed of this new program as part of routine clinical care and had the option to decline enrollment without any impact on the quality of care received.

Study participants

All patients receiving care for breast cancer in one of the participating clinics over the age of 40 were eligible for imPROVE, regardless of treatment status (ie, pre/post-operative or long-term follow-up). A parallel research study at our institution precluded participation for participants under the age of 40. Patients who were nonsurgical candidates had poor English proficiency, cognitive impairment, or a health condition preventing their ability to use a mobile application, had no smartphone access, or had poor proficiency in mobile app use/download (ie, trouble downloading applications or navigating technology) were excluded. The study team screened patients for eligibility using EHR reports and sent eligible patients a text message invitation to download imPROVE and complete an assessment (ie, their PROMs) before their clinic visit.

At clinic visits, staff (medical and administrative assistants) and clinicians (physician assistants, registered nurses, and breast and plastic surgeons) reminded patients about imPROVE—assisted by handout brochures and posters hung in communal areas.

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe the imPROVE cohort. We compared patient disease and treatment characteristics between active and pending groups using the Chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and the independent Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Before statistical tests were conducted, Kurtosis and Skewness were used to assess the normality of the data,33 and nonparametric tests were applied when values exceeded +2.0.34P-values≤.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical tests were performed in SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk NY, USA for Windows/Apple Mac).

Results

Preimplementation

Qualitative interviews conducted during the preimplementation phase elicited the following perceived implementation barriers: (1) clinic workflow and wait times, (2) compliance from patients and clinic staff, (3) data access and visualization, and (4) education and training of clinic staff. Representative statements for each barrier are listed in Table 2. We used these findings to guide the PDSA cycles in the subsequent implementation periods.

Table 2.

Qualitative barriers to PROM implementation.

| Barrier | Representative statement |

|---|---|

| Clinic workflow and wait times | “it’s just that the time of arrival is variable, and then the room crunch is the big thing that when you are in a room, you basically are only allowed to have 1, possibly 2 rooms at any given time and you have a very full schedule and like once that patient is done they really need to leave that room or it backs up everything” |

| Compliance from patients and staff | “I worry that patients will not want to fill it out if they feel that their surgeon is not even looking at it” |

| Data access and visualization | “I think the other piece is the ability to actually use the data with the patient which we really can’t in this current form um and the ability to get the data out” |

| Education and training of clinic staff | “I think one of the other big challenges is that um the front desk staff is very willing, but this is very new to them they don’t totally know what they are doing, and it wasn’t going off without a hitch, um and because of that they were really looking for support if we are going to be doing it” |

P1, June to August 2021

Our team first implemented imPROVE in 1 surgeon’s clinic (plastic surgery) at the start of P1 to intensively study and optimize integration in the clinic and ease adoption by clinic staff before expanding out to additional clinics. During this time, a dedicated research assistant supported implementation efforts in the clinic. Throughout this period, daily feedback reports from clinic staff conveyed concerns about the time needed to explain imPROVE to patients, low levels of clinic staff awareness of imPROVE and its functionality, and insufficient education or supporting materials to support clinic staff discussions with patients. To address these concerns, we developed brochures to serve as an adjunct for clinic staff in discussing imPROVE with patients and as an additional informational resource. Our team also developed and hung posters in clinic spaces and disseminated scripts to clinic staff to streamline the discussion of imPROVE with patients.

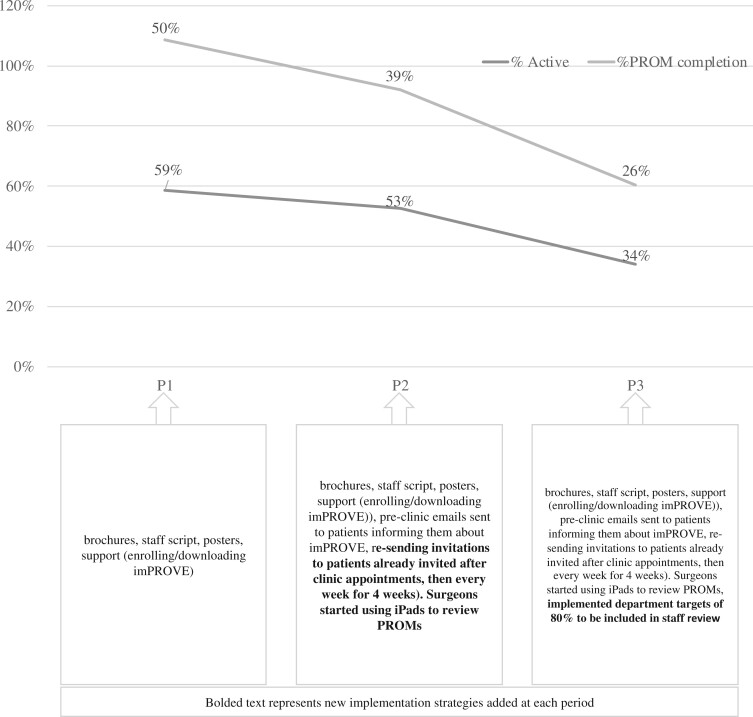

By the end of P1, 7 plastic surgeons and 1 breast surgeon with their respective care teams were enrolling patients in imPROVE. Of the 561 eligible patients, 329 (59%) downloaded imPROVE, and 280 (50% of those eligible and 78% of those who downloaded) completed at least 1 PROM (Figure 1). Among patients who downloaded imPROVE, on average, it took 19 days (range 0-161) for patients to download after they were first notified.

Figure 1.

Patient enrollment from June 2021 to February 2022.

P2, September to November 2021

During phase 2, 1 additional plastic surgeon and 3 additional breast surgeons began enrolling patients in imPROVE. During this phase, clinic staff feedback mainly involved technical issues concerning patient login capabilities, such as compatibility with cell phone software and barriers to downloading imPROVE (eg, patients forgetting passwords). To address these concerns, we established active troubleshooting and documentation of technical issues, which facilitated streamlined communication with the software vendor to address any problems. In addition, PDSA feedback informed changes to workflows which needed to be optimized and tailored to the unique clinic designs and staffing structures of breast and plastic surgery clinics (Figure 2). The project team began sending text message reminders to eligible patients who had not yet downloaded imPROVE after their initial encounter to increase download rates.

Figure 2.

Recruitment and clinic workflows. Note: Patients are mutually exclusive for each period. P1, period 1, June to August 2021; P2, period 2, September to November 2021; P3, period 3, December to February 2022.

Of the 1222 eligible patients, 644 (53%) downloaded imPROVE, and 482 (39% of those eligible, 75% of those who downloaded) completed at least 1 PROM. Among patients who downloaded imPROVE, it took 7 days on average (range 0-97) for patients to download after initial notification (Figure 1).

P3, December 2021 to February 2022

By the end of P3, all breast (n = 11) and plastic (n = 8) surgeons at the 4 clinic locations were enrolling patients in imPROVE. Feedback during this period mainly involved ideas for facilitating provider interpretation of PROM data both in terms of optimal provider-facing dashboards (desktop, tablet, or mobile phone) and contextualizing results within clinical care and available supportive resources. To address this, our team created monthly enrollment and feedback reports for clinic staff and developed instructions for providers regarding access to PROM results on desktop dashboards and mobile phones. Clinic “champions” routinely encouraged faculty to discuss PROMs as critical assessments for clinical care rather than research tools and to elicit and discuss PROM data at each clinical encounter with patients.

Of the 1178 eligible patients, 402 (34%) downloaded imPROVE, and 308 (26% of those eligible, 77% of those who downloaded) completed at least 1 PROM. Among patients who downloaded imPROVE, on average, it took 1 day (range 0-28) for patients to download after being notified (Figure 1).

Overall implementation and patient characteristics, June 2021 to February 2022

Table 3 demonstrates the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients throughout implementation. Between June 2021 and February 2022, 3031 patients were identified as candidates for imPROVE. Of these, 2961 were eligible, 1375 (46.4%) downloaded imPROVE, and 1070 (36.1% of those eligible, 78% of those who downloaded) completed at least 1 PROM (Figure 1). Figure 3 provides a run cart that outlines the number of patients who downloaded imPROVE and those who completed a PROM from P1 through P3.

Table 3.

Clinical and demographics information of eligible patients (total = 2961; P1 = 561; P2 = 1222; P3 = 1178) invited to imPROVE.

| Total | P1 | P2 | P3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age (years) | ≤49 | 781 (26.4) | 182 (32.4) | 309 (25.3) | 290 (24.6) |

| 50-59 | 952 (32.2) | 206 (36.7) | 403 (33.0) | 343 (29.1) | |

| 60-69 | 739 (25.0) | 119 (21.2) | 306 (25.0) | 314 (26.7) | |

| ≥70 | 489 (16.5) | 54 (9.6) | 204 (16.7) | 231 (19.6) | |

| Race | White | 2481 (83.8) | 487 (86.8) | 1034 (84.6) | 960 (81.5) |

| Black or African American | 127 (4.3) | 23 (4.1) | 50 (4.1) | 54 (4.6) | |

| Asian | 105 (3.5) | 16 (2.9) | 35 (2.9) | 54 (4.6) | |

| Other | 68 (2.3) | 9 (1.6) | 35 (2.9) | 24 (2.0) | |

| Prefer not to say | 43 (1.5) | 5 (0.9) | 19 (1.6) | 19 (1.6) | |

| Missing | 137 (4.6) | 21 (3.7) | 49 (4.0) | 67 (5.7) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 101 (3.4) | 21 (3.7) | 48 (3.9) | 32 (2.7) |

| Non-Hispanic | 2613 (88.2) | 503 (89.7) | 1076 (88.1) | 1034 (87.8) | |

| Prefer not to say | 24 (0.8) | 4 (0.7) | 12 (1.0) | 8 (0.7) | |

| Missing | 223 (7.5) | 33 (5.9) | 86 (7.0) | 104 (8.8) | |

| Education completed | Less than high school | 21 (0.7) | 5 (0.9) | 8 (0.7) | 8 (0.7) |

| High school | 530 (17.9) | 58 (10.3) | 241 (19.7) | 231 (19.6) | |

| College/trade/university | 1464 (49.4) | 204 (36.4) | 659 (53.9) | 601 (51.0) | |

| Graduate school | 213 (7.2) | 28 (5.0) | 89 (7.3) | 96 (8.1) | |

| Post-graduate school | 227 (7.7) | 17 (3.0) | 99 (8.1) | 111 (9.4) | |

| Prefer not to say | 64 (2.2) | 5 (0.9) | 34 (2.8) | 25 (2.1) | |

| Other | 42 (1.4) | 4 (0.7) | 23 (1.9) | 15 (1.3) | |

| Missing | 400 (13.5) | 239 (42.6) | 75 (6.1) | 86 (7.3) | |

| Marital status | Single | 433 (14.6) | 75 (13.4) | 176 (14.4) | 182 (15.4) |

| Married/common law | 1965 (66.4) | 383 (68.3) | 808 (66.1) | 774 (65.7) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 433 (14.6) | 87 (15.5) | 181 (14.8) | 165 (14.0) | |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Missing | 126 (4.3) | 16 (2.9) | 54 (4.4) | 56 (4.8) | |

| Type of surgery | Planning | 531 (17.9) | 56 (10.0) | 218 (17.8) | 257 (21.8) |

| Lumpectomy | 953 (32.2) | 80 (14.3) | 337 (27.6) | 536 (45.5) | |

| Mastectomy | 215 (7.3) | 45 (8.0) | 78 (6.4) | 92 (7.8) | |

| Reconstruction | 1262 (42.6) | 380 (67.7) | 589 (48.2) | 293 (24.9) | |

| Laterality | Unilateral | 241 (8.1) | 114 (20.3) | 41 (3.4) | 86 (7.3) |

| Bilateral | 2073 (70.0) | 384 (68.4) | 921 (75.4) | 768 (65.2) | |

| Missing | 116 (3.9) | 7 (1.2) | 42 (3.4) | 67 (5.7) | |

| Not applicable | 531 (17.9) | 56 (10.0) | 218 (17.8) | 257 (21.8) | |

Figure 3.

Run cart of the number of patients who downloaded imPROVE and completed a PROM from P1 through P3.

The mean age of eligible patients was 58 years (SD = 11; range = 40-94). Among those who did and did not download imPROVE, the mean age was 56 (SD = 10) and 60 (SD = 11), respectively. When comparing patients who did or did not download imPROVE, significant differences were identified by age group (P <.001), marital status (P =.004), surgery type (P <.001), and laterality (P <.001) (see Table 4), with patients aged up to 59 years who were married, had reconstruction surgery and had bilateral breast cancer more likely to download imPROVE.

Table 4.

Clinical and demographics information of patients who did/did not download imPROVE.

| Did not download imPROVE (N = 1586) |

Downloaded imPROVE (N = 1375) |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Age (years) | <49 | 352 | 22 | 429 | 31 | <.001 |

| 50-59 | 491 | 31 | 461 | 34 | ||

| 60-69 | 398 | 25 | 341 | 25 | ||

| ≥70 | 345 | 22 | 144 | 10 | ||

| Race | White | 1314 | 83 | 1167 | 85 | =.513 |

| Black or African American | 77 | 5 | 50 | 4 | ||

| Asian | 54 | 3 | 51 | 4 | ||

| Other | 36 | 2 | 32 | 2 | ||

| Missing | 105 | 7 | 75 | 5 | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 55 | 3 | 46 | 3 | =.809 |

| Non-Hispanic | 1391 | 88 | 1222 | 89 | ||

| Missing | 140 | 9 | 107 | 8 | ||

| Education completed | Less than high school | 12 | 1 | 9 | 1 | =.080 |

| High school | 281 | 18 | 249 | 18 | ||

| College/trade/university | 694 | 44 | 770 | 56 | ||

| Graduate school | 113 | 7 | 100 | 7 | ||

| Post-graduate school | 122 | 8 | 105 | 8 | ||

| Other | 17 | 1 | 25 | 2 | ||

| Missing | 347 | 22 | 117 | 9 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 245 | 15 | 188 | 14 | =.004 |

| Married/common law | 1018 | 64 | 947 | 69 | ||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 260 | 16 | 173 | 13 | ||

| Missing | 63 | 4 | 67 | 5 | ||

| Type of surgery | Planning | 354 | 22 | 177 | 13 | <.001 |

| Lumpectomy | 547 | 34 | 406 | 30 | ||

| Mastectomy | 134 | 8 | 81 | 6 | ||

| Reconstruction | 551 | 35 | 711 | 52 | ||

| Laterality | Unilateral | 185 | 12 | 56 | 4 | <.001 |

| Bilateral | 1000 | 63 | 1073 | 78 | ||

| Missing | 47 | 3 | 69 | 5 | ||

| Not applicable | 354 | 22 | 177 | 13 | ||

Similar results were evidenced when comparing patients who downloaded imPROVE and those who did or did not complete a PROM. Significant differences were evident by age group (P <.001) and type of surgery (P <.001), with patients aged up to 59 years who had a reconstruction surgery more likely to complete a PROM. Table 5 demonstrates the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients who downloaded and completed at least 1 PROM (vs those who did not).

Table 5.

Clinical and demographics information of patients who downloaded imPROVE and did/did not complete at least 1 PROM.

| Downloaded imPROVE and did not complete a PROM (N = 334) |

Downloaded imPROVE and completed at least 1 PROM (N = 1041) |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Age (years) | <49 | 68 | 20 | 361 | 35 | <.001 |

| 50-59 | 125 | 37 | 336 | 32 | ||

| 60-69 | 86 | 26 | 255 | 24 | ||

| ≥70 | 55 | 16 | 89 | 9 | ||

| Race | White | 282 | 84 | 885 | 85 | =.948 |

| Black or African American | 13 | 4 | 37 | 4 | ||

| Asian | 12 | 4 | 39 | 4 | ||

| Other | 9 | 3 | 23 | 2 | ||

| Missing | 18 | 5 | 57 | 5 | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 6 | 2 | 40 | 4 | =.077 |

| Non-Hispanic | 298 | 89 | 924 | 89 | ||

| Missing | 30 | 9 | 77 | 7 | ||

| Education completed | Less than high school | 3 | 1 | 6 | 1 | =.591 |

| High school | 62 | 19 | 187 | 18 | ||

| College/trade/university | 191 | 57 | 579 | 56 | ||

| Graduate school | 21 | 6 | 79 | 8 | ||

| Post-graduate school | 20 | 6 | 85 | 8 | ||

| Other | 7 | 2 | 18 | 2 | ||

| Missing | 30 | 9 | 87 | 8 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 43 | 13 | 145 | 14 | =.780 |

| Married/common law | 228 | 68 | 719 | 69 | ||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 45 | 13 | 128 | 12 | ||

| Missing | 18 | 5 | 49 | 5 | ||

| Type of surgery | Planning | 53 | 16 | 124 | 12 | <.001 |

| Lumpectomy | 121 | 36 | 285 | 27 | ||

| Mastectomy | 17 | 5 | 64 | 6 | ||

| Reconstruction | 143 | 43 | 568 | 55 | ||

| Laterality | Unilateral | 14 | 4 | 42 | 4 | =.682 |

| Bilateral | 243 | 73 | 830 | 80 | ||

| Missing | 24 | 7 | 45 | 4 | ||

| Not applicable | 53 | 16 | 124 | 12 | ||

Overall, 19 care teams, consisting of a plastic or breast surgeon, and their respective staff (administrative, medical and physician assistants, or registered nurses), implemented imPROVE during the study period.

Discussion

This article describes our initial experience implementing imPROVE, a new HIT platform for PROM collection among surgical breast cancer patients in breast and plastic surgery clinics over 9 months. We employed iterative PDSA cycles to address the many and varied barriers to implementation that changed throughout the study period, ultimately refining the implementation of systematic PROM collection in clinical care across 19 clinics in 4 locations. These results inform existing and future implementation efforts for routine PROM collection in clinical care using smartphone-based HIT platforms.

Throughout the 9-month implementation period, PDSA cycles proved essential for elucidating and addressing the most salient barriers to implementation at a given time. Initial feedback broadly highlighted gaps in clinic staff knowledge of imPROVE and a need for more comfort with its functionality, which was addressed with informational brochures, posters, scripts for administrative staff, and ongoing in-person facilitation by research assistants. Subsequently, technical issues at the patient level became notable and were resolved with iterative problem-solving with the software vendor. In the latest phase (P3), feedback identified the need to facilitate provider-level engagement and application of PROs during a clinic encounter which we did with several added features. These findings suggest that, while optimization of technical issues and logistics are critical, successful implementation also depends on adequate staff onboarding and a culture shift in clinical operations, whereby routine PROM collection is recognized as a standard of care procedure among providers and staff. These findings are supported by research that has shown a lack of awareness of PROMs within the workplace to be among the most significant barriers to their implementation.35 In addition, these findings highlight the need for adaptable implementation strategies that can be iterated in real-time. As each issue was addressed, others emerged as most salient for further optimization.

While PDSA cycles guided day-to-day operations and long-term strategies, the RE-AIM framework allowed us to gauge implementation success over time. In pre-defining reach, effectiveness, and adoption goals (Table 1), for example, we were able to better focus our efforts across many different providers and clinical settings. This framework also allowed us to structure PDSA cycles around common goals and elucidate barriers, facilitators, and lessons learned for critical metrics of implementation success.

Regarding reach, we observed that the time between notification of imPROVE and subsequent download was shortened for each implementation period. This finding may be explained, in part, by the longer follow-up time of patients notified within the initial implementation periods, as these patients may have had multiple appointments and text message reminders to download imPROVE at later timepoints. It is also likely due to greater technology optimization, workflows, and communication throughout implementation. Nonetheless, we found routine reminders, both in the form of text messages to patients and from front desk staff at follow-up appointments, to be critical for the ongoing enrollment of patients.

Our study also revealed notable differences in clinical and demographic characteristics between patients who did and did not download imPROVE and between those who did and did not complete at least 1 PROM. Patients who did not download imPROVE were significantly older, unmarried, and had lower educational attainment than patients who downloaded improve and were more likely to have had a mastectomy and unilateral surgery. Similar differences were observed for age and type of surgery between patients who did and did not complete at least 1 PROM. Notably, however, there was no significant difference in race between those who did and did not download imPROVE and those who completed at least 1 PROM. Studies investigating PROM implementation in diverse and underrepresented patient populations have demonstrated disparate response rates, which may be partly explained by the unique concerns and preferences of these populations.36 A better understanding of the concerns of these patients will be the topic of future investigation to guide further implementation efforts and achieve equitable PROM collection.

The effectiveness of our implementation was primarily assessed through weekly clinic feedback obtained as part of our PDSA cycles. In our experience, optimizing clinic workflows, utilizing PROM “champions” in the clinic, and the cultural shift of using PROMs as a routine assessment rather than a research tool were critical for effective implementation. PROM implementation programs in routine clinical care have been noted previously to incur additional costs, with additional staffing resource requirements.21,37 Accordingly, our study highlighted the need for collaboration among providers, research assistants, technical support staff, and the data management team. In attempting to integrate imPROVE into standard clinical care workflows, for example, efforts were needed to ensure that all care team members were aligned. We identified care team members whose involvement was essential for implementation success. These included administrative assistants and front desk staff, who were often the patients’ first point of contact regarding the mobile app; medical assistants, who were able to confirm and encourage app usage during rooming and vital signs intake; physician assistants and physicians, who discussed app usage and individual PROM results during appointments; and research assistants, who provided valuable feedback on implementation efforts and individualized technical support to patients and providers while the mobile app was being optimized.

Concerning adoption, although most patients who downloaded imPROVE eventually completed at least 1 PROM, the primary attrition rate in our study among eligible patients was in the initial download step. Indeed, we observed that the overall percentage of patients who downloaded imPROVE declined over time as we expanded to more clinics and providers, despite ongoing optimization efforts and steady PROM completion rates among those who did download the app. Many patients reported not remembering their app store account password, which precluded imPROVE download. The decline in the overall percentage of patients who downloaded imPROVE may also be explained by fewer opportunities for follow-up and text message reminders for patients recruited in P3. But this barrier aside, our experience revealed that some patients might have been overwhelmed in the context of their clinic visit and preferred not to download the app. Further, some patients prefer to use their hospital patient portals and may have found the additional mobile application onerous.

Although routine PROM collection using mobile applications has been successful in other clinical settings,33,38 our results suggest that there may be better ways to engage with all patients other than mobile applications. Instead, mobile-friendly web-apps may enable greater integration with existing patient portals and EHR systems to reduce barriers to PROM completion and will be an important area of future study for our team.

There is a pressing need for acceptable and effective ways to collect PROMs in routine clinical care, to improve patient outcomes, enhance patient-provider communication, and inform quality improvement and reimbursement policies.21,39,40 Our study adds to the growing body of literature describing the implementation of PROMs in routine clinical care. Notably, our study details implementation efforts across 2 surgical departments at 2 academic teaching hospitals, which allowed for collaboration across clinical specialties and longitudinal PROM reporting for patients undergoing breast cancer care. The implementation effort highlighted patient difficulties with mobile app-based PROM collection, particularly around initial engagement.

There were limitations to our study. First, although research assistants were instrumental in supporting patients and providers during the initial stages of implementation, this was an additional resource needed for successful implementation. While the need for additional staffing and resources has been cited as a barrier to routine PROM collection,21 the level of support provided by research assistants in our study reassuringly lessened over time as technical components of the app were optimized to the point where certain providers no longer required support. Second, the imPROVE app was not integrated within the patient portal or EHR at the time of this study and was only accessible via smartphones, which may have served as a barrier to patient use. However, smartphone ownership has become increasingly prevalent among adults, and reliance on smartphones for internet access is particularly common among racial and ethnic minorities, low income, and low education adults.41 Third, this study was limited to adults aged 40 and older, which limited our results generalizability. Nonetheless, because smartphone ownership and mobile app usage are more common among younger adults,41,42 we believe implementation would be as much, if not more, successful in this younger population and will be an important focus of future research.

This study lays the groundwork for several critical next steps. Given our initial success in breast cancer and plastic surgery clinics at 2 large academic medical centers, we hope to expand these efforts to patients receiving care in community cancer centers. As PROM collection in routine clinical care becomes increasingly more common, it will be imperative to ensure that PROM data are being collected from all patients, especially those who have been historically excluded from research to date, such as racial and ethnic minorities and patients with low socioeconomic status.43,44 In addition, we will explore alternatives to third-party mobile-app-based PROM collection and to expand across medical specialties, departments, and institutions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients who enrolled and provided data for this important initiative. We would further like to acknowledge the clinic staff who provided support throughout implementation.

Contributor Information

Elena Tsangaris, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, United States.

Colby Hyland, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, United States.

George Liang, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, United States.

Joanna O’Gorman, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, United States.

Dany Thorpe Huerta, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, United States.

Ellen Kim, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, United States.

Maria Edelen, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, United States.

Andrea Pusic, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115, United States.

Author contributions

E.T. and A.P. conceived and designed the study. E.T., C.H., G.L., J.O.G., D.T.H., conducted the study methodology. A.P. and M.E. provided oversight to methodology. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

Dr Andrea Pusic is a co-developer of the BREASTQ which is owned by Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (50%), Brigham and Women’s Hospital (25%), and McMaster University (25%). Dr Pusic receives a portion of licensing fees (royalty payments) when the BREASTQ is used in industry-sponsored clinical trials. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Laugsand EA, Sprangers MA, Bjordal K, Skorpen F, Kaasa S, Klepstad P.. Health care providers underestimate symptom intensities of cancer patients: a multicenter European study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):104. 10.1186/1477-7525-8-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weldring T, Smith SM.. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Health Serv Insights. 2013;6:61-68. 10.4137/HSI.S11093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Basch E. Patient-reported outcomes—harnessing patients’ voices to improve clinical care. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(2):105-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marshall S, Haywood K, Fitzpatrick R.. Impact of patient‐reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(5):559-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, et al. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(4):575-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Branch WT, Malik TK.. Using ‘windows of opportunities’ in brief interviews to understand patients’ concerns. JAMA. 1993;269(13):1667-1668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McHorney CA, Tarlov AR.. Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res. 1995;4(4):293-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gibbons C, Porter I, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, et al. Routine provision of feedback from patient‐reported outcome measurements to healthcare providers and patients in clinical practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;10(10):CD011589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xiao C, Polomano R, Bruner DW.. Comparison between patient-reported and clinician-observed symptoms in oncology. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(6):E1-E16. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318269040f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, et al. Adverse symptom event reporting by patients vs clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009; 101(23):1624-1632. 10.1093/jnci/djp386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cleeland C, Vaporcian A, Shi Q, et al. A computerized telephone monitoring and alert system to reduce postoperative symptoms: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl 15):9536. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cleeland CS. Symptom burden: multiple symptoms and their impact as patient-reported outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2007;2007(37):16-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89(7):1634-1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cleeland CS, Reyes-Gibby CC.. When is it justified to treat symptoms? Measuring symptom burden. Oncology. 2002;16(9 suppl 10):64-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Basch E, Iasonos A, Barz A, et al. Long-term toxicity monitoring via electronic patient-reported outcomes in patients receiving chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(34):5374-5380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Basch E, Iasonos A, McDonough T, et al. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: results of a questionnaire-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(11):903-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duman-Lubberding S, van Uden-Kraan CF, Jansen F, et al. Durable usage of patient-reported outcome measures in clinical practice to monitor health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(12):3775-3783. 10.1007/s00520-017-3808-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Basch E. New frontiers in patient-reported outcomes: adverse event reporting, comparative effectiveness, and quality assessment. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65:307-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Users’ guide to integrating patient-reported outcomes in electronic health records. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-JHU-Users-Guide-To-Integrating-Patient-Reported-Outcomes-in-Electronic-Health-Records.pdf

- 21. Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(8):1305-1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Duncan EA, Murray J.. The barriers and facilitators to routine outcome measurement by allied health professionals in practice: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:96. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsangaris E, Edelen M, Means J, et al. User-centered design and agile development of a novel mobile health application and clinician dashboard to support the collection and reporting of patient-reported outcomes for breast cancer care. BMJ Surg Interv Health Technol. 2022;4(1):e000119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM). (2020). About Patient-Centered Outcome Measures. Accessed April 1, 2020. https://www.ichom.org/standard-sets/#about-standard-sets

- 25. Ong WL, Schouwenburg MG, van Bommel ACM, et al. A standard set of value-based patient-centered outcomes for breast cancer: the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) initiative. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(5):677-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, et al. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):345-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pinnocṅk H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. ; StaRI Group. Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI) statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neergaard MA, Olesen F, Andersen RS, et al. Qualitative description—the poor cousin of health research? Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Directions and Examples. Content last reviewed September 2020. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/tool2b.html

- 31. Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM.. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, et al. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44(2):119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pickens R, Cochran A, Tezber K, et al. Using a mobile application for real-time collection of patient-reported outcomes in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery within an ERAS® pathway. Am Surg. 2019;185(8):909-917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim H-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38(1):52-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nguyen H, Butow P, Dhillon H, et al. Using patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in routine head and neck cancer care: what do health professionals perceive as barriers and facilitators? J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2020;64(5):704-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hyland CJ, Guo R, Dhawan R, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes in routine clinical care for diverse and underrepresented patients in the United States. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2022;6(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loo S, Grasso C, Glushkina J, et al. Capturing relevant patient data in clinical encounters through integration of an electronic patient-reported outcome system into routine primary care in a Boston Community Health Center: Development and implementation study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e16778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ben-Ali W, Lamarche Y, Carrier M, et al. Use of mobile-based application for collection of patient-reported outcomes in cardiac surgery. Innovations (Phila). 2021;16(6):536-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kruse CS, Goswamy R, Raval Y, Marawi S.. Challenges and opportunities of big data in health care: a systematic review. JMIR Med Inform. 2016;4(4):e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Squitieri L, Bozic KJ, Pusic AL.. The role of Patient-Reported outcome measures in value-based payment reform. Value Health. 2017;20(6):834-836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pew Research Center. Mobile fact sheet. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/#who-owns-cellphones-and-smartphones

- 42. Dittrich F, Back DA, Harren AK, et al. Smartphone and app usage in orthopedics and trauma surgery: survey study of physicians regarding acceptance, risks, and future prospects in Germany. JMIR Form Res. 2020;4(11):e14787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ortega G, Allar BG, Kaur MN, et al. Prioritizing health equity in patient-reported outcome measurement to improve surgical care. Ann. Surg. 2022;275(3):488-491. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sisodia RC, Dewdney SB, Fader AN, et al. Patient reported outcomes measures in gynecologic oncology: a primer for clinical use, part I. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158(1):194-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.