Abstract

Background and Objectives

The American Academy of Neurology has developed quality measures related to various neurologic disorders. A gap exists in the implementation of these measures in the different health care systems. To date, there has been no electronic health care record nor implementation of quality measures in Antigua. Therefore, we aimed to increase the percent of patients who have epilepsy quality measures documented using standardized common data elements in the outpatient neurology clinic at Sir Lester Bird Medical Center from 0% to 80% per week by June 1, 2022 and sustain for 6 months.

Methods

We used the Institute for Health care Improvement Model for Improvement methodology. A data use agreement was implemented. Data were displayed using statistical process control charts and the American Society for Quality criteria to determine statistical significance and centerline shifts.

Results

Current and future state process maps were developed to determine areas of opportunity for interventions. Interventions were developed following a “Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle.” One intervention was the creation of a RedCap survey and database to be used by health care providers during clinical patient encounters. Because of multiple interventions, we achieved a 100% utilization of the survey for clinical care.

Discussion

Quality improvement (QI) methodology can be used for implementation of quality measures in various settings to improve patient care outcomes without use of significant resources. Implementation of quality measures can increase efficiency in clinical delivery. Similar QI methodology could be implemented in other resource-limited countries of the Caribbean and globally.

Introduction

Problem Statement

Quality measures are developed based on available evidence to support care processes and outcomes. These measures are applied when gaps in implementation are identified.1 The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) created and updated quality measures to assist in addressing such gaps. These include quality measures directed to improve care of people with epilepsy.2,3 However, there are processes, which are required to implement or to improve performance on quality measures. There is also need of specific resources and technology to assist in implementation of quality measures into daily clinical practice. Unfortunately, many neurology practices outside the United States, lack technology, such as electronic health records (EHRs). This technology facilitates standardized data collection and visualization.4 In addition, data sharing and analysis need standardized codes and terminology that are often used only in US-based EHR systems.4 Even countries with access to these resources face challenges with implementation of measures directed to improve epilepsy care.5

Available Knowledge

Recently, a workgroup from the American Academy of Neurology created quality measures related to seizure frequency documentation and outcome.5 Previous projects directed at implementation of datasets or guidelines to improve epilepsy care have demonstrated feasibility of this methodology.6,7 Introduction of common data element has been successfully implemented in various systems in the United States, with the goal of improving epilepsy care.7 Quality improvement (QI) methodology has also been used in various projects, showing a positive impact in the medical care of people with epilepsy.6,8-11

Data implementation and visualization is a key component to QI projects, and various databases have been created for this purpose. One of these resources is the “Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).” The REDCap was created in 2004 and used as an instrument to enter key clinical questions or data, and it is used mostly for research purposes.12 Use of the REDCap improves efficiency of data entry,13 and it can be used successfully in international collaborative programs. The REDCap could be implemented for measurement-based pathway implementation and QI purposes even when technology resources are scarce.14-17

Rationale

QI methodology is effective in implementing epilepsy and child neurology quality measures. Collection of critical epilepsy data using a standardized format in a care setting outside the United States was felt possible, despite the lack of an EHR platform.

Specific Aim

The aim of the QI project was to implement epilepsy quality measures, during epilepsy outpatient clinic visits from a baseline of 0%–80% by June 2022 and sustain results for 6 months.

Methods

Setting

The Neurology Department where our project was conducted is located at Sir Lester Bird Medical Center in St. John's, Antigua W.I. The workforce consists of nearly 500 employees with a medical staff of more than 200 and has a 185-bed hospital offering a full range of services, from primary care to advanced critical care.

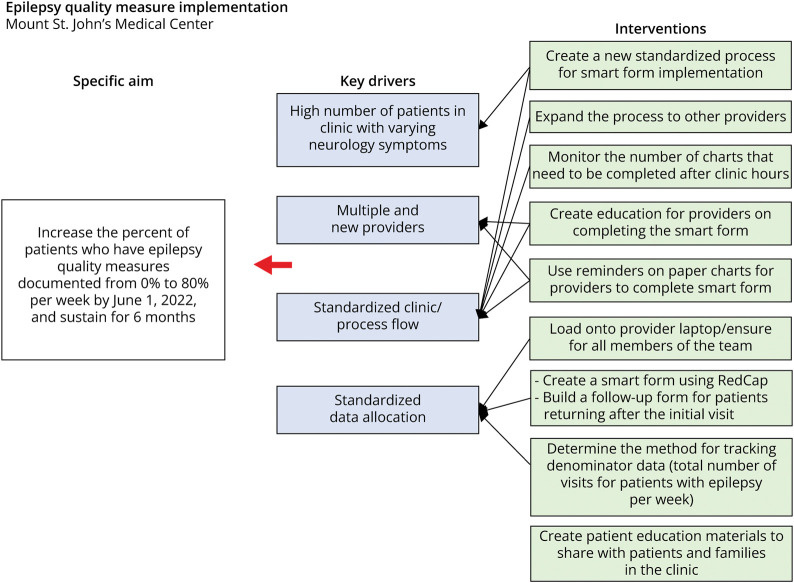

Using QI methodology based on the Institute for Health care Improvement (IHI) Model for Improvement,18 a multidisciplinary team was convened to develop a project aim and Key Driver Diagram (KDD) (Figure 1). Key drivers were determined using process mapping and group brainstorming. After developing the KDD, interventions were tested using Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles. The multidisciplinary team consisted of neurology providers, nursing, and QI specialist. This article was prepared using the SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Reporting Excellence) 2.0 guidelines.19

Figure 1. Key Driver Diagram for Quality Improvement Project.

Interventions

A multidisciplinary care team was formed at Sir Lester Bird Medical Center. The members were led by the neurologist, board certified in neurology and clinical neurophysiology. Other key members included a nurse/EEG technician and house officers. House officers are physicians who have completed an intern year and are assigned to the neurology service and a neurology assistant. The house officers see and evaluate the patients and staff with the neurologist, much like it is done in any established neurology training program. The neurology assistant has a master's degree in neuroscience and conducts the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) for depression and anxiety screening, respectively. In addition, the neurology assistant performed a satisfaction survey with patients and/or families after the clinic encounter. A virtual 2-hour training session was given locally to the entire team on the basics of QI. The training consisted of presentations about QI methodology and science using IHI methodology including creation of an aim statement, key drivers, and interventions. Education related to epilepsy-related quality measures was provided.

The first intervention was the development of a REDCap survey and database for documentation of AAN quality measures and other clinical information (Table). The database was developed in March 2022 to mirror the standardized documentation used in EHR for documenting AAN quality measures, as published in previous literature.7 The team added new clinical information related to seizure action plan implementation, water safety, and driving, which was uniquely important to the patient population in Antigua. Once all elements were added into the REDCap, providers and the nursing team conducted a PDSA in mid-April 2022 to ensure completeness and accuracy of the process. Additional modifications were made to the database in June 2022.

Table.

RedCap Data Elements

| Question |

| Does the patient have an epilepsy diagnosis? |

| Was SUDEP discussed at this visit? |

| Was the patient counselled on driving with epilepsy at this visit? |

| Was the patient screened for anxiety and/or depression at this visit? |

| Was the patient counselled regarding water safety at this visit? |

| Was the patient/caregiver counselled on epilepsy, and how its treatment may affect contraception and/or pregnancy? |

| For infantile spasms—what treatment was given as first line? |

| Did the patient have a normal physical examination? |

| If the patient's examination was abnormal, please list findings here: |

| When was the patient's last generalized tonic-clonic seizure? |

| Recently, what is the frequency of generalized tonic-clonic seizures? |

| In the past 12 mo, have any generalized tonic-clonic seizures occurred at night or from sleep? |

| When was the patient's last MOTOR seizure (not including GTCs)? |

| Recently, what is the frequency of MOTOR seizures (not including GTCs)? |

| When was the patient's last nonmotor seizure (for example, absence seizure or seizures with impaired awareness only)? |

| Recently, what is the frequency of nonmotor seizures? |

| When was the patient's last epileptic spasm (single spasm or cluster)? |

| Has the patient had status epilepticus requiring an emergency department visit in the past 12 mo? |

| Think of patient's usual routines, how often in the past 2 wk have seizures significantly changed it? |

| Think of patient's usual routine, how often in the past 2 wk have medication side effect changed it? |

| Epilepsy type: (best guess, taking into consideration history and diagnostic findings) |

| Is this child's epilepsy treatment resistant? |

| Is this child's epilepsy new onset? (i.e., the first unprovoked seizure was less than 6 mo ago) |

| What was the patient's age at first unprovoked seizure? |

| Current epilepsy syndrome: |

| Specific conditions associated with epilepsy: |

| Has the patient ever had epilepsy surgery? (including devices) |

| What kind of surgery? (can choose multiple) |

| Is the epilepsy etiology known? |

| Most recent brain imaging studies: |

| Please list any other imaging findings here: |

| Has genetic testing been conducted? |

| What is the genetic or chromosomal abnormality? |

| Is there a metabolic etiology? |

| Is there an infectious etiology? |

| Is there an autoimmune etiology? |

| What imaging studies have been performed? |

| Additional imaging study notes: |

| What were the results of the patient's EEG? |

| Does the patient have a developmental delay? (based on clinical impression/history) |

| Psychiatric/behavioral/cognitive Does the patient have any of the following comorbidities? (select all that apply) |

| Neurologic/heme Does the patient have any of the following comorbidities? (select all that apply) |

| Technology dependent Does the patient have any of the following comorbidities? (select all that apply) |

After determining accuracy and functionality of the REDCap system, 2 more PDSA cycles were conducted in April and May to integrate documentation of quality measures into the current clinic flow. Subsequently, the team concluded that the best time for documentation was after each clinic visit, based on available resources. Occasionally, the documentation was performed after the clinic ended due to busy schedules before project onset.

The team ensured that patient information could be tracked in a meaningful and accurate way by using a function in the REDCap to show how many patients had the necessary information documented during the clinic visit. Nurses used a separate spreadsheet for tracking number of clinic visits completed each week. These 2 data sources were used to measure the percent of patients with epilepsy who had information documented during their outpatient clinic visit.

We hypothesized that visual cues may be needed as a reminder to providers to complete the REDCap during clinic visits. However, with the immediate success of the project, additional reminders were not necessary.

After the REDCap database was implemented, the team developed a “follow-up” documentation in July 2022 for subsequent patient's visits. Follow-up documentation could be linked to the REDCap database using a unique identification number. After ensuring this new process was successful, the team shifted focus to integrating patient's education materials into clinic visits. Education has been the most impactful with 6 months of follow-up.

Patient and caregiver resources around specific process measures were adapted from existing resources and used to provide important education related to epilepsy care. Objective measurements have been difficult without electronic medical record (EMR), but subjective improvements have been described in Sudden Unexpected death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) education, driving, water safety, and women issues related to their participation in their reproductive health. This measurement was initially overlooked in the first 6 months of follow-up but will be implemented in the 1-year follow-up plan.

Study of the Interventions

Data were generated from 2 sources, the REDCap reporting system and manually maintained spreadsheets. Each week, a REDCap report was produced, showing the total number of patients who had the quality measures documented at clinic visits. This report included a unique patient identifier, date, and time of completion and visit provider's name. This was compared with a spreadsheet created by nursing staff to track the total number of clinic visits completed that week. A data use agreement was developed for data integrity.

Measures

The measure used for this project included the percent of patients with epilepsy seen weekly who had complete documentation of the “care items” based on the epilepsy-related quality measures.

Analysis

A QI specialist collected and analyzed the data on a weekly basis in Microsoft Excel. Pivot tables were generated to determine how many patients seen in clinic had the AAN quality measures documented in the REDCap. A statistical process control (SPC) chart20 was used to show changes in project performance over time and distinguish between common and special cause variation. The American Society for Quality21 rules for calculating special cause variation were used in the analysis of the SPC chart. A p chart was used to show the percentage of patients seen in clinic with AAN measures documented. p Values were calculated using the Minitab Statistical software.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

Institutional review board approval was not required for this project because it was for QI purposes. A data use agreement was created and implemented between the data hub at Nationwide Children's Hospital and Sir Lester Bird Medical Center.

Data Availability

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

As of end of July 2022, there have been a total of 68 unique patients screened since the project began in April 2022. Of the 68 patients, 3 patients also had follow-up documentation completed for subsequent clinic visits. Forty-seven percent reported being male and 53% female. Ten percent of patients were 15 years or younger. Sixty-eight percent of patients were between 15 and 64 years of age and 22% were 65 years and older.

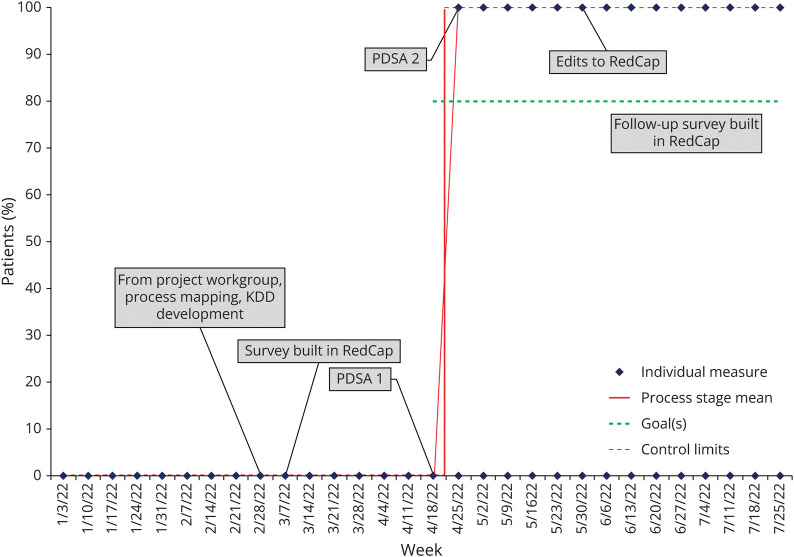

The overall proportion of outpatient epilepsy clinic visits with a screening completed increased from a baseline of 0%–100% within the first week of intervention implementation in April 2022, and results have been sustained (p < 0.001). The p chart represents a total of 68 patients with epilepsy who were seen in outpatient clinic since April 2022 through the end of July 2022 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Control Chart Showing the Percentage of Patients Seen in Outpatient Epilepsy Clinic With AAN Measures Documented During the Visit.

Following the first PDSA cycle, a centerline shift was noted. Subtle changes were made to the form to allow for more streamlined administration to mirror clinical workflow. The changes assisted in the continued 100% performance on measure implementation. Educational materials were developed based on previous similar tools created at an outside institution. Patients were given these materials for the respective quality measure. By implementation of the RedCap form, a 50% improvement was noted for educational material and counseling being provided. Furthermore, clinical note completion time was reduced by approximately 75% because of using the form with very few notes needed completed following normal clinic hours. Provider satisfaction was not officially measured; however, input from the clinical team was collected with demonstration of improved workflow, easier completion of documentation, and implementation of quality measures.

Discussion

Using QI methodology, the team was able to implement a new clinical process and successfully complete documentation of important epilepsy-related clinical information7 based on existing AAN measures.2,3,5 This occurred during ongoing outpatient epilepsy clinic visits in Sir Lester Bird Medical Center. The completion rate was 100% success exceeding the projected goal of 80%.

Facilitating access to medical information and improving delivery of care are some of the benefits of electronic health information systems and EHRs. These systems are designed with the intention to be user-friendly and cost-effective.22,23 Despite wide availability of EHRs in countries with scarce resources, there are still substantial challenges in successful implementation. Some of these challenges include provider-specific documentation habits, complexity of the data elements, and intrinsic variability of epilepsy health records.24 Provider documentation habits have shown to be one of the most difficult barriers to overcome. Additional challenges include physician burnout, provider and physician institutional changes, and physician consistency.25 EHRs may, however, provide a useful tool for the complex management of different epilepsy syndromes and the associated comorbidities, with an ultimate focus on improving quality of care. Implementation of QI methodology directed to improve seizure-epilepsy documentation, using timely interactive EHRs, has been proven to substantially improve seizure and epilepsy-related documentation.6

Implementation of successful EHR systems in resource-poor settings present additional challenges. Lack of adequate infrastructure, privacy and security issues, public distrust, absence of developmental strategies, and lack of political will are some of the main hurdles to overcome. Cost of available systems are also an important limitation for implementation of EHRs in resource-limited settings. Ideally, a continuous supply of electricity and internet access should be available, but this is not a guarantee in many regions globally. Sustainability of external records and data retrieval must be of utmost importance.

As an example, the implementation of iSante', Haiti's national EHR, sourced and funded externally, exemplified both concerns and benefits of implementation in a less than ideal setting.26 Over 10 years of implementation, the system revealed difficulties in sustainability of different components, including technical, organizational, political, ethical, financial, training, and functionality. Despite all these hurdles, the application of quality measures by standardizing documentation and data collection could improve care delivery and alleviate the inconsistent documentation and poor standardization of paper records.

Our QI project may not be successfully implemented in other health care systems because our project was dependent on engaged and energized personnel at Sir Lester Bird Medical Center. However, the medical team reported improved efficiency in data collection and documentation in the outpatient clinic setting. In addition, documentation has not been linked to improved patient outcomes in epilepsy within this care setting and will be followed over time to determine ultimate success. In addition, we applied questions based on US quality measures, and these may not be relevant to all countries. It is important to have cultural awareness and cultural sensitivity of questions asked and gain input from those using the smart form and quality measures. For our project, we therefore, incorporated additional safety measures that were felt important to the local team, but not official AAN quality measures.

We recognize the results show our success in the short term, and there is need to continue with the monitoring process and sustainability to confirm long-term success in implementation of the quality measures. Nevertheless, this initial pilot project demonstrated that this type of intervention can be achieved in a country outside the United States that does not have all our resources in health care. Further integration of other data from additional centers wishing to participate in similar work has not been established.

QI methodology has been shown to be useful in the field of epilepsy specifically related to implementation of quality measure to improve patient care.6,9-11 Such implementation is possible in various care settings including neurology and epilepsy practices internationally. Further work in dissemination of similar methodology among other care settings is a potential opportunity to improve outcomes for people with epilepsy regardless of where care is sought or obtained.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Ashley Young for her assistance in the preparation of this article.

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Gaden Osborne, MD | Neurology Department, Sir Lester Bird Medical Centre, St. John’s, Antigua, West Indies | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and study concept or design |

| Olivia Valenti, MPH | The Center for Clinical Excellence, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Juniella Jarvis, MSc | Neurology Department, Sir Lester Bird Medical Centre, St. John’s, Antigua, West Indies | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and study concept or design |

| Evelynne Wentzel, RN | Division of Neurology, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and study concept or design |

| Jorge Vidaurre, MD | Division of Neurology, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and study concept or design |

| Dave F. Clarke, MD | Pediatric Neurology, Dell Medical School, the University of Texas at Austin | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; and study concept or design |

| Anup D. Patel, MD | The Center for Clinical Excellence; Division of Neurology, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

→ Epilepsy and Child Neurology quality measures were created by workgroups led by the American Academy of Neurology.

→ A framework can be created to use quality improvement in neurology practices caring for people with epilepsy.

→ Creation and implementation of standardized data entry around important quality measures in epilepsy be implemented in countries outside the United States.

References

- 1.Adirim T, Meade K, Mistry K, Council on Quality Improvement and Patient Safety, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Management. A new era in quality measurement: the development and application of quality measures. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20163442. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel AD, Baca C, Franklin G, et al. Quality improvement in neurology: epilepsy quality measurement set 2017 update. Neurology. 2018;91(18):829-836. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel AD, Berg AT, Billinghurst L, et al. Quality improvement in neurology: child neurology quality measure set: executive summary. Neurology. 2018;90(2):67-73. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shivers J, Amlung J, Ratanaprayul N, Rhodes B, Biondich P. Enhancing narrative clinical guidance with computer-readable artifacts: authoring FHIR implementation guides based on WHO recommendations. J Biomed Inform. 2021;122:103891. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2021.103891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munger Clary H, Josephson SA, Franklin G, et al. Seizure Frequency process and outcome quality measures: quality improvement in neurology. Neurology. 2022;98(14):583-590. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones FJS, Smith JR, Ayub N, et al. Implementing standardized provider documentation in a tertiary epilepsy clinic. Neurology. 2020;95(2):e213-e223. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grinspan ZM, Patel AD, Shellhaas RA, et al. Design and implementation of electronic health record common data elements for pediatric epilepsy: foundations for a learning health care system. Epilepsia. 2021;62(1):198-216. doi: 10.1111/epi.16733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel AD, Terry D, Moore JP, et al. Reduction of emergency department visits using an urgent clinic for children with established epilepsy. Neurol Clin Pract 2016;6(6):480-486. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel AD, Wood EG, Cohen DM. Reduced emergency department utilization by patients with epilepsy using QI methodology. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20152358. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel AD, Debs A, Terry D, et al. Decreasing emergency department visits for children with epilepsy. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021;11(5):413-419. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000001109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel AD, Herbst J, Gibson A, et al. Using quality improvement to implement the CNS/AAN quality measure on rescue medication for seizures. Epilepsia. 2020;61(12):2712-2719. doi: 10.1111/epi.16713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obeid JS, McGraw CA, Minor BL, et al. Procurement of shared data instruments for research electronic data capture (REDCap). J Biomed Inform. 2013;46(2):259-265. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gesell SB, Halladay JR, Mettam LH, Sissine ME, Staplefoote-Boynton BL, Duncan PW. Using REDCap to track stakeholder engagement: a time-saving tool for PCORI-funded studies. J Clin Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):108-114. doi: 10.1017/cts.2019.444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawley S, Yu J, Bogetic N, et al. Digitization of measurement-based care pathways in mental health through REDCap and electronic health record integration: development and usability study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(5):e25656. doi: 10.2196/25656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris PA, Delacqua G, Taylor R, Pearson S, Fernandez M, Duda SN. The REDCap mobile application: a data collection platform for research in regions or situations with internet scarcity. JAMIA Open. 2021;4(3):ooab078. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooab078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyman WB, Passeri M, Murphy K, et al. The next step in surgical quality improvement: outcome situational awareness. Can J Surg. 2020;63(2):E120-E122. doi: 10.1503/cjs.000519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12):986-992. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolfe HA, Taylor A, Subramanyam R. Statistics in quality improvement: measurement and statistical process control. Paediatr Anaesth. 2021;31(5):539-547. doi: 10.1111/pan.14163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(6):458-464. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.6.458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldzweig CL, Towfigh A, Maglione M, Shekelle PG. Costs and benefits of health information technology: new trends from the literature. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(2):w282-w293. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond L, Paré G, Ortiz de Guinea A, et al. Improving performance in medical practices through the extended use of electronic medical record systems: a survey of Canadian family physicians. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:27. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0152-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth CP, Lim YW, Pevnick JM, Asch SM, McGlynn EA. The challenge of measuring quality of care from the electronic health record. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(5):385-394. doi: 10.1177/1062860609336627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson SL, Robinson MD, Reid A. Electronic health record effects on work-life balance and burnout within the I(3) population collaborative. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):479-484. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00123.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.deRiel E, Puttkammer N, Hyppolite N, et al. Success factors for implementing and sustaining a mature electronic medical record in a low-resource setting: a case study of iSanté in Haiti. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(2):237-246. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data not published within this article will be made available by request from any qualified investigator.