Abstract

Purpose of Review:

Veterans are a large population that is disproportionately affected by various physical and mental health conditions. The primary aim of this review is to provide a concise overview of recent literature on the prevalence of cannabis use and cannabis use disorder (CUD) among US Veterans, and associations with mental and physical health conditions. We also addressed gaps in the literature by investigating associations between CUD and mental and physical health conditions in 2019 data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA; N=5,657,277).

Recent Findings:

In total, 25 studies were reviewed. In 2019, the prevalence of Veteran cannabis use ranged from 11.9%–18.7%. Cannabis use and CUD were associated with bipolar disorders, psychotic disorders, suicidality, pain conditions, and other substance use, but less consistently associated with depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Analyses of 2019 VHA data indicated that CUD was strongly associated with a broad array of physical and mental health conditions and mortality.

Summary:

Cannabis use and CUD are prevalent and highly comorbid with other conditions among US Veterans. Harm reduction methods tailored to these populations are needed.

Keywords: cannabis, cannabis use disorder, Veterans, Veterans Health Administration, mental health, pain

1. INTRODUCTION

Cannabis is one of the most widely-used psychoactive substances[1, 2], and approximately one-third of regular users develop cannabis use disorder (CUD)[3]. Since 1996, many states have legalized medical and recreational cannabis use, the THC potency of cannabis products has increased substantially, and the prevalence of cannabis use and CUD has risen[3, 4].

Although cannabis is increasingly perceived as a safe substance[5], its use is associated with many adverse consequences[6, 7], e.g., falls[8], injuries, emergency department visits[9], and physical[10] and mental health conditions[7]. Compared to the general population, Veterans have higher general morbidity[11], including conditions such as chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that are associated with medical and non-medical cannabis use[12]. Consequently, understanding the differences in physical and mental health conditions between Veterans who use cannabis or have CUD and those who do not is an important public health priority.

A previous review[12] found that Veterans with cannabis use or CUD were more likely than Veterans without to have psychiatric disorders, more severe symptoms, poorer functioning, and use other substances or have other substance use disorders (SUD). This review provided important information, but studies used a wide variety of methods and measures, and left gaps in some areas, e.g., relationships of CUD to painful medical conditions and mortality. Since then, additional studies were published. We therefore had two aims in this report. The first was to conduct an updated review to expand and update findings from the previous review[12] and identify emerging inconsistencies and continuing gaps in knowledge. The second was to address some of the gaps with new analyses using electronic health record (EHR) data from Veterans receiving care within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in 2019. These analyses examined a range of conditions previously associated with CUD, but using consistent methodology across all conditions.

2. METHODS

2.1. Review strategy

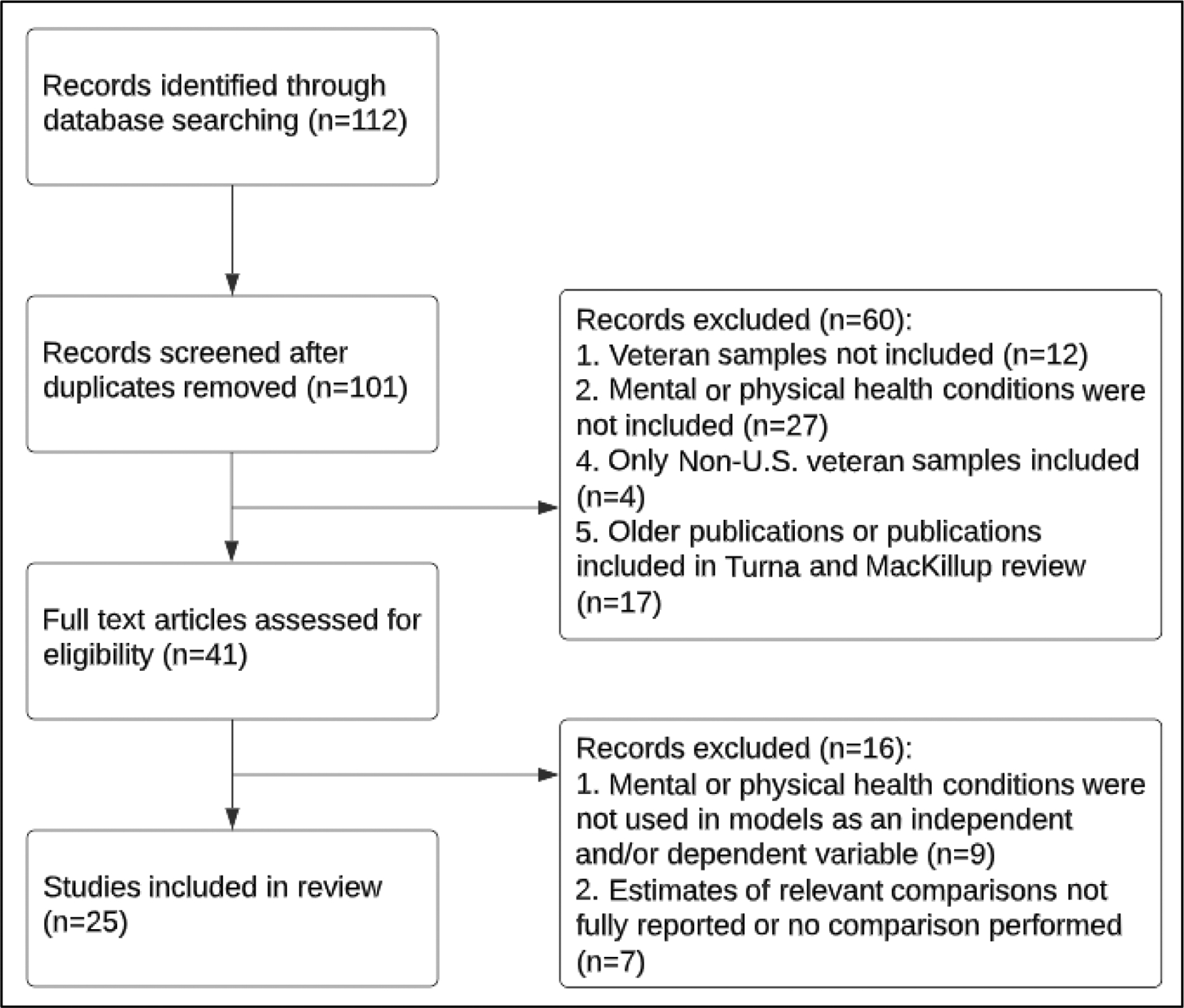

Our review complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)[13]. We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Google Scholar and Web of Science for peer reviewed studies using these search terms: (veteran OR veteran health) AND (cannabis OR marijuana) AND (psychiatric disorder OR mental health OR psychopathology OR pain OR mortality). The previous review[12] included publications through December 2019. We therefore included publications from January 2020 through August 2022. Titles and abstracts from the searches were screened by two reviewers for suitability for full-text review and inclusion (OL and DS) (Figure 1). Additional inclusion criteria were: (a) study used US data; (b) available in English; (c) cannabis use or CUD was an independent or dependent variable; (d) psychiatric disorders (i.e., depressive, anxiety, PTSD, bipolar, psychotic spectrum), suicidality (ideations or attempts), pain conditions, or other substance use/SUD were independent or dependent variables; and (e) sample of Veterans. Included studies are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Studies investigating cannabis use, CUD, psychiatric disorders, pain conditions, and other substance use.

| Year | Authors | Study Design | Sample size (n) | % Malea | Cannabis use measureb | Assessment of use/CUD | Psychiatric disorders | Pain conditions | Other substance use/SUD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use (timeframe) | CUD (timeframe) | ||||||||||

| Nationally representative samples | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2022 | Waddell et al. | Cross-sectional analyses of NSDUH data (2002–2019) | 706,897 | 88.3 | ✓ (Past-year) |

-- | -- | -- | -- | ✓ (Alcohol) |

| 2 | 2022 | Browne et al. | Cross-sectional analysis of NESARC-III (2012–2013) subsample of U.S. veterans | 36,289 | 90.2 | ✓ (Lifetime/past- year) |

✓ (Lifetime/past- year) |

DSM-5 | ✓ (Depressive disorders, Anxiety disorders, PTSD, Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol, Tobacco, other drugs) |

| 3 | 2022 | Enkema et al. | Cross-sectional analysis of NESARC-III (2012–2013) subsample of U.S. veterans | 36,289 | 90.2 | ✓ (Lifetime/past- year) |

✓ (Lifetime/past- year) |

DSM-5 | -- | ✓ | -- |

| 4 | 2022 | Hill ML et al. | Cross-sectional analysis of a veteran sample from NHRVS | 4,069 | 90.2 | ✓ (Past 6 months) |

✓ (Past 6 months) |

CUDIT-SF | ✓ (Depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, PTSD) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol, Tobacco) |

| 5 | 2021 | Hill ML et al. | Cross-sectional analysis of a veteran sample from NHRVS | 4,069 | 90.2 | ✓ (Past 6 months) |

✓ (Lifetime/past 6 months) |

CUDIT-R, CUDIT-SF, MINI | ✓ (Depressive disorders, PTSD, Suicidality) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol) |

| 6 | 2021 | Hill et al. | Cross-sectional analysis of a veteran sample from NHRVS | 4,069 | 81.2 | ✓ (Past 6 months) |

-- | CUDIT-R | ✓ (Depressive disorders, Anxiety disorders, PTSD, Suicidality) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol, Tobacco) |

| 7 | 2021 | Hill et al. | Cross-sectional analysis of a veteran sample from NHRVS | 3,157 | 92.0 | ✓ (Lifetime) |

✓ (Lifetime) |

MINI | ✓ (Depressive disorders, Anxiety disorders, PTSD, Suicidality) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol, Tobacco) |

| 8 | 2020 | Agaku et al. | Cross-sectional analyses of NSDUH data (2015–2017) | 128,720 | 92.3 | ✓ (Past 30 days/past-year) |

-- | -- | -- | -- | ✓ (Alcohol, Tobacco, Other drugs) |

| VHA-based samples | |||||||||||

| 9 | 2022 | Livingston et al. | Longitudinal analyses (span of 7 years) of a sample of returning combat-deployed veterans identified through a VHA database | 1,649 | ?? | -- | ✓ (Lifetime) |

ICD-9 | ✓ (Depressive disorders, Anxiety disorders, PTSD) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol) |

| 10 | 2022 | Kearns et al. | Longitudinal analyses (span of 1 year) of a sample of veterans recruited from a VHA facility | 361 | 93.4 | ✓ (Past 30 days) |

-- | TLFB, MPS | -- | -- | ✓ (Alcohol) |

| 11 | 2022 | Browne et al. | Cross-sectional analyses of a sample of veterans recruited from VHA primary care clinics | 1,072 | 95.5 | ✓ (Past 30 days) |

-- | -- | ✓ (PTSD) |

✓ | ✓ (Alcohol, Tobacco, Other drugs) |

| 12 | 2022 | Grove et al. | Cross-sectional analyses of a sample of Gulf War veterans recruited from the VHA Healthcare system | 1,126 | 78 | ✓ (Past-year) |

-- | -- | ✓ (Suicidality) |

-- | -- |

| 13 | 2022 | Metrik et al. | Longitudinal analyses (span of 1 year) of a sample of veterans recruited from a VHA facility | 361 | 93 | -- | ✓ (Lifetime/past- year) |

SCID-NP | ✓ (PTSD) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol, Tobacco, Other drugs) |

| 14 | 2022 | Selloni et al. | Cross-sectional analysis of a veteran sample from the VHA Cooperative Studies Program | 254 | 84.6 | ✓ (Current and past use) |

-- | -- | ✓ (PTSD, Bipolar disorder) |

-- | ✓ (Other drugs) |

| 15 | 2021 | Hoggatt et al. | Cross-sectional analyses of a sample of veterans recruited from 30 VHA healthcare facilities | 6,000 | 91.0 | ✓ (Lifetime/past 30 days) |

-- | ASSIST 3.1 | -- | -- | ✓ (Alcohol, Other drugs) |

| 16 | 2020 | Gunn et al.. | Longitudinal analyses (span of 1 year) of a sample of veterans recruited from a VHA facility | 361 | 93.0 | ✓ (Past 6 months) |

-- | TLFB | ✓ (Depressive disorders) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol) |

| 17 | 2019 | Metrik et al. | Cross-sectional analysis of data from a larger ongoing prospective study on veterans recruited for a VHA facility | 143 | 93.0 | ✓ (Lifetime) |

-- | MMPQ | ✓ (Depressive disorders, PTSD) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol, Other drugs) |

| 18 | 2021 | Bryan et al. | Cross-sectional analysis VHA EMR data (2010–2016) | 46,268 | 92.9 | -- | ✓ (Lifetime) |

ICD-9-CM, ICD-10 | ✓ (Depressive disorders, Anxiety disorders, PTSD, Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol, Tobacco, Other drugs) |

| 19 | 2021 | Dillon et al. | Cross-sectional analysis of VHA patients (post-deployment Iraq/Afghanistan-eraveterans) | 3,028 | 79.5 | -- | ✓ (Lifetime) |

SCID | ✓ (Depressive disorders, PTSD) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol, Other drugs) |

| Other samples | |||||||||||

| 20 | 2022 | Tran et al. | Cross-sectional analyses on an online sample of U.S. veterans recruited via social medial | 1,230 | 89.0 | ✓ (Past 30 days) |

-- | -- | ✓ (Anxiety disorders) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol, Tobacco) |

| 21 | 2022 | Reilly et al. | Cross-sectional analyses on an online sample of U.S. veterans via a Qualtrics panel | 409 | 76.5 | ✓ (Lifetime) |

-- | Modified ASSIST |

✓ (Depressive disorders, Anxiety disorders, PTSD, Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder) |

✓ | ✓ (Alcohol, Tobacco, Other drugs) |

| 22 | 2021 | Kang et al. | Cross-sectional analysis of veterans enrolled in the Illinois Medical Cannabis Patient Program | 3,272 | 92.1 | ✓ (Past-year) |

-- | -- | -- | ✓ | ✓ (Other drugs) |

| 23 | 2021 | Pedersen et al. | Cross-sectional analyses on an online sample of veterans recruited via social media | 1,230 | 88.7 | -- | ✓ (Past 6 months) |

CUDIT-R | ✓ (Depressive disorders, Anxiety disorders, PTSD) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol) |

| 24 | 2021 | Pedersen et al. | Longitudinal analyses (span of 6 months) of an online sample of veterans recruited via social media | 1,025 | 89.5 | ✓ (Lifetime) |

✓ (Past 30 days) |

-- | ✓ (PTSD) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol) |

| 25 | 2021 | Fitzke et al. | Cross-sectional analyses on an online sample of veterans recruited via social media | 1,230 | 89.5 | ✓ (Past 30 days) |

-- | -- | ✓ (Depressive disorders) |

-- | ✓ (Alcohol) |

Percent males of total number of veterans included in analyses.

Frequency (%) of cannabis use measure among veterans included in the study sample.

Abbreviation: CUD=Cannabis use disorder; DSM-5= Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; NSDUH= National Survey on Drug Use and Health; NESARC-III= National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III; NHRVS= National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study; PTSD=Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; CUDIT-R= The Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test -Revised; MINI= Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; VHA=Veterans Health Administration; ICD-9/CM= International Classification of Diseases,Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; TLFB= The Timeline Followback; MPS= Marijuana Problems Scale Marijuana Problems Scale; ASSIST 3.1= Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test version 3.1; MMPQ= Medical Marijuana Patient Questionnaire; SCID/-NP= Structured Clinical Interview for DSM non-patient edition; EMR=Electronic Medical Record.

2.2. New analyses

2.2.1. Sample and procedures

EHR data from 1/1/2019 to 12/31/2019 were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse, a repository containing patient-level data for care received at VHA facilities or paid for by VHA. Veterans with ≥1 primary care, emergency department, and/or mental health outpatient visit at a VHA facility in 2019 were identified. Veterans were excluded if they received hospice/palliative care (n=80,440) or resided outside the 50 US states or Washington DC (n=54,840) for a final sample size of N=5,657,277. The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at the VHA Puget Sound, New York Harbor Healthcare Systems, and New York State Psychiatric Institute.

2.2.2. Measures

Diagnoses of psychiatric and substance use disorders and chronic pain were based on ICD-10-CM diagnoses (Supplementary Table 1) made by providers during a 2019 encounter at a VHA facility or at a community care visit covered by the VHA. Diagnoses excluded remission codes.

Cannabis Use Disorder.

ICD-10-CM codes for abuse (F12.1X) and dependence (F12.2X) were combined to form a CUD variable.

Psychiatric and other substance use disorders.

These included bipolar, depressive, psychotic, generalized/other anxiety, panic, PTSD, and phobias. SUD diagnoses included alcohol, nicotine, opioids, cocaine, stimulants, sedatives, and other drugs.

Chronic pain.

Medical conditions associated with chronic pain (Supplementary Table 1) were identified using Mayhew et al.’s ICD-10-CM classification system[14]. A dichotomous variable was created indicating any chronic pain condition, and a categorical variable indicating 0, 1 or ≥ 2 chronic pain conditions, to assess the effect of multiple conditions[15].

Elevated suicide risk.

Defined as any of the following: suicide attempt diagnosis, a patient suicide high-risk flag in the EHR, or suicide risk assessment note completed[16].

Mortality.

Coded positive for those with dates of death in 2019, obtained from the VHA Vital Status File, which combines VHA and non-VHA (Medicare, Social Security) death data for Veterans seen in VHA.

Demographic characteristics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of Veterans in 2019 VHA EMR data

| Overall | No CUD | CUD | Difference Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=5,657,277) | (n=5,548,674) | (n=108,603) | ||||||||

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | |||||

| Cannabis use disorder | 1.92 | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |||

| Continuous age (mean) | 61.92 | 0.01 | 62.15 | 0.01 | 50.36 | 0.04 | t (114206) = 262.34* | |||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 9.24 | 0.01 | 9.24 | 0.01 | 8.97 | 0.09 | X 2 (1) = 9.25 | |||

| Male | 90.76 | 0.01 | 90.76 | 0.01 | 91.03 | 0.09 | ||||

| Race and Ethnicity | X 2 (4) = 13682.14* | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 70.33 | 0.02 | 70.60 | 0.02 | 56.80 | 0.15 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 17.98 | 0.02 | 17.72 | 0.02 | 31.14 | 0.14 | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 6.05 | 0.01 | 6.04 | 0.01 | 6.74 | 0.08 | ||||

| Other/Multiple Race and Ethnicity | 3.32 | 0.01 | 3.32 | 0.01 | 3.32 | 0.05 | ||||

| Unknown | 2.31 | 0.01 | 2.32 | 0.01 | 2.00 | 0.04 | ||||

| Marital Status | X 2 (4) = 41618.96* | |||||||||

| Married | 55.13 | 0.02 | 55.65 | 0.02 | 28.51 | 0.14 | ||||

| Divorced/Separated | 24.82 | 0.02 | 24.50 | 0.02 | 41.13 | 0.15 | ||||

| Never Married | 14.11 | 0.01 | 13.85 | 0.01 | 27.41 | 0.14 | ||||

| Widowed | 4.47 | 0.01 | 4.51 | 0.01 | 2.26 | 0.05 | ||||

| Unknown | 1.47 | 0.01 | 1.49 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.03 | ||||

| Initial Period of Service | X 2 (5) = 48724.17* | |||||||||

| Pre-Vietnam | 13.53 | 0.01 | 13.78 | 0.01 | 0.58 | 0.02 | ||||

| Vietnam | 38.19 | 0.02 | 38.50 | 0.02 | 22.14 | 0.13 | ||||

| Post-Vietnam | 14.32 | 0.01 | 14.12 | 0.01 | 24.48 | 0.13 | ||||

| Persian Gulf | 14.84 | 0.01 | 14.83 | 0.02 | 15.52 | 0.11 | ||||

| OIF/OEF/OND | 18.95 | 0.02 | 18.59 | 0.02 | 37.19 | 0.15 | ||||

| Unknown | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.01 | ||||

| Unstable Housing Status | 4.17 | 0.01 | 3.67 | 0.01 | 29.60 | 0.14 | X 2 (1) = 179251.00* | |||

| Urbanicity | X 2 (2) = 3307.92* | |||||||||

| Urban | 65.18 | 0.02 | 65.02 | 0.02 | 73.31 | 0.13 | ||||

| Rural | 30.86 | 0.02 | 30.99 | 0.02 | 24.19 | 0.13 | ||||

| Highly Rural | 3.96 | 0.01 | 3.99 | 0.01 | 2.50 | 0.05 | ||||

| Cannabis State Law Status | X 2 (2) = 7.66 | |||||||||

| No state cannabis legalization | 37.43 | 0.02 | 37.43 | 0.02 | 37.12 | 0.15 | ||||

| State legalization of medical cannabis use only | 40.02 | 0.02 | 40.02 | 0.02 | 40.02 | 0.15 | ||||

| State legalization of recreational cannabis use only | 22.55 | 0.02 | 22.55 | 0.02 | 22.87 | 0.13 | ||||

Notes:Difference test degrees of freedom appear in parentheses;

= p<.0001;

OIF/OEF/OND = Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation New Dawn.

These included age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, initial service period, unstable housing status, urbanicity and 2019 cannabis state law status based on last recorded residence.

2.2.3. Statistical Analysis

First, unadjusted chi-square tests of independence were run for categorical sociodemographic variables and t-tests for comparison of means were run for a continuous age variable to examine whether there were any overall differences detected between Veterans with and without CUD. Second, logistic regression models examined the association of CUD (predictor) with each diagnosis (outcomes), adjusted for sex, age, race and ethnicity. The predictive margins from each model were used to estimate the prevalence of the outcome among Veterans with and without CUD. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) from each model are reported.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of the literature.

We reviewed 25 studies (Figure 1, Table 1); 20 were cross-sectional and 5 were longitudinal. Samples included: 1) respondents of nationally representative US surveys of the general population (n=4) and Veterans (n=4); 2) Veterans receiving care at a VHA facility or recruited for a VHA study (n=11); 3) Veterans recruited through non-VHA healthcare settings or online (n=6). All samples were predominantly male (77%–96%). Cannabis use measures were included in 20 studies, 10 studies included CUD measures, and 5 studies included both. Psychiatric disorders were included in 19 studies, pain in 4 studies, and other substance use or SUD in 23 studies. A variety of measures of all these conditions were used across the studies. No study assessed mortality.

3.2. Prevalence of cannabis use and/or CUD among Veterans.

A study of the Veteran subsample of a 2012–2013 survey of the US adult general population showed a past-year prevalence of 7.3% and 1.8% for cannabis use and CUD, respectively[17]. A 2019 study of a nationally representative sample of US Veterans showed prevalences of past 6-month cannabis use and CUD as 11.9% and 2.7%, respectively[18]. Among Veterans receiving primary care within VHA facilities between 2012–2014, the prevalence of past-year cannabis use was 18.7%[19]. Finally, among 6,000 Veterans recruited from 30 VHA healthcare facilities in 2018–2019, rates of past-year cannabis misuse (defined as using cannabis to get high, to get a buzz, to feel elated, or to change a mood), and past 3-month daily use were 11.5% and 4.5%, respectively[20]. For context, note that the overall past-year prevalence of cannabis use and CUD in US adults in 2012–2013 was 9.5% and 2.9%, respectively[3], and a 2019 survey of US adults showed that 12.9% of adults had past-year cannabis use[21]. Thus, recent rates of cannabis use and CUD in Veterans were generally within the range seen in the adult general population.

3.3. Depressive disorders

In the prior review[12], heavy cannabis use was consistently associated with increased risk of depression, as also found in reviews of non-Veteran studies[22]. We found 13 additional studies of cannabis use or CUD and depression among Veterans (Table 1). Regarding cannabis use, 5 studies showed a positive association with depressive disorders. These included a study of the Veteran subset in a 2012–2013 nationally representative adult survey showing that any lifetime mood disorder (including depressive and bipolar disorders) was associated with lifetime cannabis use (aOR=2.90)[17], and also two surveys of nationally representative Veteran samples showing that MDD was associated with any cannabis use (compared to no cannabis use; aOR=1.65) and frequent use (compared to no use; aOR=3.48) [23, 24]. Additionally, a study of VHA EHR data showed that Veteran cannabis users with comorbid PTSD were more likely to be diagnosed with depressive disorders than non-users[25]. A longitudinal study of an online-recruited Veteran sample showed that cannabis use predicted more severe symptoms of depression over a 6-month period[26]. Regarding CUD, 4 studies showed positive associations with MDD, including the 2012–2013 study of the Veteran subset of the U.S. adult sample (aOR=4.37)[17] and three surveys of nationally representative veteran samples (aOR range=2.76–2.79) [18, 23, 24]. In contrast, 4 studies did not show significant associations of cannabis use and/or CUD with depression. Such differences may stem from variations in methodologies, sample designs and characteristics, timeframes and measures used to assess cannabis use/CUD. For example, one of these 4 studies used any frequency of cannabis use as a measurement of use[18], whereas another study[23], utilizing a slightly different subsample from the same dataset, showed significant associations with depressive disorders utilizing greater than weekly cannabis use as a measurement of use. In another example, two studies showed no significant associations between CUD and depression variables, one a cross-sectional study[27] and the other a longitudinal study[28] utilizing, in part, VA data. However, these studies used subsamples of Iraq/Afghanistan-era Veterans as opposed to other VA studies (including the sample we analyzed in this report), that showed significant associations with depressive disorders in samples that were not focused on a specific era of service.

3.4. Anxiety disorders.

Although a large literature addresses the relationship of cannabis use/CUD to anxiety disorders in the general population[29, 30], only 2 empirical studies used Veteran samples[31, 32] at the time of the previous review[12]. However, in both studies, anxiety disorder measures were included only as mediating variables. Since the prior review, 9 additional studies were published focused on relationships of cannabis use or CUD to anxiety disorders, with one of these reporting only descriptive results[33]. Six studies showed associations of cannabis use or CUD with anxiety disorders. For example, a cross-sectional nationally representative study of US adults showed that Veterans with any anxiety disorder (e.g., panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder [GAD]) were more likely to use cannabis than those without anxiety disorders (aOR=2.27)[17]. Two additional cross-sectional studies, both relying on a representative sample of US Veterans, showed that GAD was associated with cannabis use in a dose dependent manner in Veterans with underlying PTSD (frequent cannabis use vs. no use: aOR=3.81)[23] as well as with CUD in all Veterans (aOR range=2.75)[24]. Two studies[34, 35], relying on online samples of Veterans showed longitudinal associations of cannabis use/CUD to GAD. In contrast, two studies did not show significant associations between cannabis use and anxiety disorder, including a cross-sectional study[18] of past 6-month cannabis use and current GAD among a national sample of US Veterans, and a longitudinal study[28] showing that Veterans with prior CUD at baseline had greater rates of GAD than others, but longitudinally, GAD trajectories did not differ significantly between those with and without CUD. While the recent literature has begun to report on relationships of cannabis use/CUD to anxiety disorders among Veterans, with some, but not all, studies indicating significant positive associations, more studies that focus on anxiety disorders among cannabis using Veterans are needed. The additional analyses provided herein aim to expand the literature.

3.5. Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Among Veterans, PTSD has been strongly associated with cannabis use, as shown by many studies included in the previous review [12]. Since January 2020, 15 additional studies were published focused on relationships of cannabis use or CUD to PTSD. Seven studies showed associations of cannabis use or CUD with PTSD. For example, a cross-sectional study that used a nationally representative sample of adults (Veterans and non-Veterans)[17] showed that lifetime cannabis use and CUD were significantly associated with lifetime PTSD. Four cross-sectional studies[18, 23, 24, 36] of nationally representative samples of Veterans indicated significant associations between cannabis use/CUD and PTSD; one of these studies reported that the prevalence of past-month PTSD among those with CUD was 12.6%, compared to 7.2% among those without CUD (p<.001)[24]. Two additional cross-sectional studies using samples of VHA patients indicated significant associations between cannabis use/CUD and PTSD[25, 37]. One longitudinal study showed that over a period of 7 years, Veterans with CUD had a slower rate of improvement in PTSD symptom severity compared to those without CUD[28]. Similar longitudinal findings were demonstrated, albeit across shorter time periods, in an additional study[38]. In the only study that used VHA EHR data (2010–2016), PTSD was the most common comorbidity among Veterans with CUD (72.3%), however associations between PTSD and CUD were not examined[25]. In contrast, 3 studies did not provide evidence for significant associations of cannabis use or CUD to PTSD. In s nationally representative sample of US adults (Veterans and non-Veterans), although significant associations with PTSD were observed for lifetime cannabis use and CUD, similar associations were not observed for 12-month cannabis use/CUD[17]. In another study utilizing a nationally representative sample of Veterans, associations of past 6-month cannabis use and CUD to current PTSD were not significant[18]. Additionally, in a sample of VHA patients, differences in prevalence of current PTSD between Veterans with (32.5%) and without (30.4%) lifetime CUD were not significant[27]. While most of the studies in this review, including longitudinal studies, indicated strong associations between cannabis use/CUD and PTSD diagnoses and/or symptomatology, others did not. Mixed results are likely related to variations in timeframes and measures of cannabis and PTSD variables that were used across the different studies.

3.6. Bipolar disorders.

In the general population, CUD is strongly associated with bipolar disorders, particularly Bipolar I[3]. However, to our knowledge, only three studies examined bipolar disorder and cannabis use/CUD in VHA samples, two[39, 40] included in the previous review[12] and one published subsequently[37]. In two studies of bipolar patients[37, 39], rates of CUD/cannabis use were descriptively higher than in general population subsamples with bipolar disorder[40], and among Veterans with CUD[40], rates of bipolar disorder were higher than in the general population. However, these associations were not formally tested, so the literature continued to leave a gap in knowledge.

3.7. Psychotic disorders.

Although a large literature addresses the relationship of cannabis use/CUD to psychotic disorders, we know of only two reports on this in Veterans. In a paper included in the prior review[12], 6.7% of VHA patients diagnosed with CUD had psychotic disorder diagnoses[40], a higher rate than in the adult general population. In a more recent report, among returning war Veterans diagnosed with CUD between 2010–2016[25], 4.2% had a schizophrenia diagnosis; other psychotic disorders were less common and not reported. Thus, surprisingly little information is available on the association of cannabis use/CUD and psychotic disorders in Veterans.

3.8. Suicidality.

The previous review[12] showed in three studies of Veterans that CUD was associated with suicidality. In three new studies published since the prior review, data were examined from nationally representative surveys of Veterans. One study showed that Veterans with CUD were over twice as likely as non-cannabis users to endorse suicidal ideation, and over 3 times as likely to have made a suicide attempt[24]. Additionally, compared to Veterans with only alcohol use disorder (AUD), past-year and lifetime suicidal ideation was more likely in Veterans with CUD and with AUD+CUD[36]. In Gulf War Veterans[41], cannabis use was also associated with past-year suicidal ideation and elevated risk for suicidal behavior. Thus, findings have been consistent in showing that CUD is associated with suicidality.

3.9. Pain disorders.

The previous review[12] included one study on CUD and pain conditions[42], but only patients receiving opioid treatment for pain were included in this study with no comparison/control group not receiving opioids. We found four additional studies that all demonstrated associations of more severe pain with cannabis use/CUD, as well as prevalent use of medical cannabis for pain management among Veterans. In a general population study of adults with moderate to severe pain, Veterans were more likely than non-Veterans to use cannabis and to endorse CUD[43], and the prevalence of frequent cannabis use was greater among those with moderate or severe pain than those with none or mild pain. Similar findings came from a study of VHA primary care patients, in whom more severe pain was associated with any past-year cannabis use[19]. VHA patients using medical cannabis had more severe pain than those using recreational cannabis; cannabis use for pain management was common and perceived as effective[19, 44]. Two studies examined associations between pain and CUD in older data (collected prior to enactment of cannabis legislation in many states)[19, 43], and no study examined whether CUD risk differed by presence of more than one chronic pain condition, which is associated with more severe pain and disability[15].

3.10. Other substance use/SUD.

The previous review[12] showed that cannabis use/CUD was highly associated with other substance use/SUD in Veterans, consistent with general population findings[45]. Our review of 23 additional studies yielded generally similar findings. Approximately 33% of Veterans with CUD also met criteria for alcohol use disorder (AUD) in a nationally representative sample of US Veterans[36]. AUD was significantly more prevalent among those with cannabis use than others among Iraq/Afghanistan-era Veterans[36], VHA patients[19], and Veterans with underlying psychiatric conditions[23, 37]. Additionally, compared to Veterans without cannabis use/CUD, those with cannabis use/CUD demonstrated higher rates of tobacco use, tobacco use disorder (TUD), illicit drug use, opioid use disorder (OUD), and other drug use disorders[23, 24, 36]. A longitudinal study showed associations between more severe alcohol use and CUD[28], and data from a large cross-sectional study that demonstrated that past 12-month AUD, OUD, TUD, and other drug use disorder were associated with greater odds of past 12-month cannabis use or CUD[17]. However, associations between cannabis/CUD and other substance use differed depending on whether Veterans used medical or recreational cannabis[19, 46]. For example, VHA patients in primary care settings using only medical cannabis had lower odds of alcohol and drug use, drug use disorders, and alcohol or drug-related problems compared to Veterans using only recreational cannabis[19], consistent with another study showing that lifetime medical cannabis users had significantly fewer days of any alcohol use and heavy alcohol use in the past month than lifetime recreational cannabis users[46].

3.11. New analyses

3.11.1. Demographic characteristics (Table 2).

Of the 5,657,277 Veteran patients, most were male (90.8%), and non-Hispanic White (70.3%), with a mean age of 61.9. Approximately 2% had been clinically diagnosed with CUD in 2019. Except for sex and cannabis state law status, significant differences (p<.0001) between Veterans with and without CUD were observed across all sociodemographic variables; Veterans with CUD were significantly younger, with increased likelihood of being non-Hispanic Black, divorced/separated or never married, post-Vietnam Era or OIF/OEF/OND, living in urban areas, and with unstable housing, compared to those without CUD.

3.11.2. Psychiatric disorders (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of CUD and psychiatric, chronic pain, and substance use disorders among veterans

| No CUD* | CUD** | CUD v. No CUD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=5,548,674) | (n=108,603) | |||||||

| Adj. %a | SEb | Adj. %a | SEb | aORc | 95% CId | |||

| Psychiatric Disorders | ||||||||

| Any Psychiatric Disordere | 28.30 | 0.02 | 75.62 | 0.14 | 8.85 | 8.71, 8.99 | ||

| Psychotic Disorders | 1.55 | 0.01 | 10.34 | 0.09 | 7.44 | 7.29, 7.58 | ||

| Bipolar Disorder | 2.00 | 0.01 | 13.71 | 0.10 | 8.13 | 7.98, 8.27 | ||

| Depressive Disorders | 15.59 | 0.02 | 41.50 | 0.15 | 4.04 | 3.99, 4.09 | ||

| PTSD | 14.32 | 0.01 | 37.77 | 0.14 | 3.88 | 3.83, 3.92 | ||

| Panic Disorders | 0.77 | 0.00 | 2.42 | 0.04 | 3.23 | 3.12, 3.35 | ||

| Phobias | 0.39 | 0.00 | 1.16 | 0.03 | 2.98 | 2.84, 3.14 | ||

| General/Other Anxiety Disorders | 9.10 | 0.01 | 28.05 | 0.13 | 4.13 | 4.08, 4.19 | ||

| Elevated Suicide Risk | 1.16 | 0.00 | 10.95 | 0.08 | 11.18 | 10.97, 11.39 | ||

| Chronic Pain Conditions | ||||||||

| Any Pain Condition | 53.56 | 0.02 | 69.90 | 0.14 | 2.03 | 2.00, 2.05 | ||

| Single | 25.26 | 0.02 | 24.66 | 0.13 | 1.40 | 1.38, 1.43 | ||

| Multiple | 25.08 | 0.02 | 40.67 | 0.14 | 2.34 | 2.31, 2.38 | ||

| Substance Use Disorders | ||||||||

| Any SUDf | 6.38 | 0.01 | 51.15 | 0.15 | 16.71 | 16.50, 16.93 | ||

| Alcohol | 5.20 | 0.01 | 40.10 | 0.15 | 13.02 | 12.85, 13.18 | ||

| Opioid | 0.85 | 0.00 | 9.68 | 0.08 | 12.68 | 12.41, 12.95 | ||

| Cocaine | 0.59 | 0.00 | 14.01 | 0.10 | 31.96 | 31.31, 32.61 | ||

| Other Stimulants | 0.38 | 0.00 | 10.22 | 0.09 | 30.51 | 29.82, 31.22 | ||

| Sedatives | 0.12 | 0.00 | 3.09 | 0.05 | 25.75 | 24.70, 26.85 | ||

| Nicotine | 19.18 | 0.02 | 56.80 | 0.15 | 5.61 | 5.55, 5.68 | ||

| Other Substancesg | 0.54 | 0.00 | 10.75 | 0.09 | 23.08 | 22.60, 23.58 | ||

| Mortality | 1.81 | 0.01 | 2.96 | 0.08 | 1.69 | 1.59, 1.79 | ||

Notes:

No CUD = Veterans without a cannabis use disorder.

CUD = Veterans with a cannabis use disorder.

Adj. % = percent estimate based on predictive margin of adjusted logistic model (i.e., sex, age, and race and ethnicity included as covariates).

SE = standard error of adjusted percent estimate.

aOR = odds ratio based on adjusted logistic model.

95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

Any disorder listed under psychiatric disorders except elevated suicide risk.

Any substance use disorder other than cannabis use disorder.

Other Substances = substance use disorders not included in substance use disorder category (e.g., hallucinogens, inhalants).

Veterans with CUD were more likely to have a psychiatric diagnosis compared to those without CUD, across disorders (aOR range: 2.98–11.18). Among patients with CUD, 75.6% were diagnosed with at least one co-occurring psychiatric disorder compared to 28.3% in the no-CUD group (aOR=8.9). Depressive disorders, PTSD, and generalized/other anxiety (excluding panic disorder and phobias) were the most prevalent psychiatric disorders among those with CUD (41.5%, 37.8%, and 28.1%, respectively). Further, 11.0% of Veterans with CUD had elevated suicide risk compared to only 1.2% without CUD (aOR=11.18).

3.11.3. Chronic pain (Table 3).

The CUD group had greater odds of any chronic pain diagnosis (aOR=2.0), such that almost 70% of Veterans with CUD had a co-occurring pain diagnosis compared to 53.6% of Veterans without CUD. Veterans with and without CUD had similar prevalence of only one pain diagnosis (aOR=1.4), however, Veterans with CUD had higher rates of multiple pain conditions (40.67%) compared to Veterans without CUD (25.1%; aOR=2.34).

3.11.4. Substance use disorders (Table 3).

CUD was associated with increased odds of having a SUD across substances. Over half of the CUD group had SUD other than CUD, compared to only 6% of the no-CUD group (aOR=16.71). The most prevalent SUDs in the CUD group were nicotine, alcohol, and cocaine use disorder (56.8%, 40.1%, and 14.0%, respectively). Given the opioid crisis, it is important to note that CUD was associated with increased odds of an opioid use disorder (aOR=12.7), such that 9.7% of Veterans with CUD had OUD compared to less than 1% of Veterans without CUD.

3.11.5. Mortality (Table 3).

Among Veterans with and without CUD, 3.0% and 1.8% respectively died in 2019; Veterans with CUD had greater odds of mortality (aOR=1.7).

4. DISCUSSION

Cannabis use and CUD are prevalent among Veterans, a population disproportionally affected by many health conditions. Our review of the recent literature of a variety of Veteran samples suggests that cannabis use and CUD are significantly associated with several mental and physical health conditions. Nevertheless, findings were inconsistent for certain psychiatric disorders. In addition, in new analyses of 2019 VHA data, we provide important information showing that after adjusting for key sociodemographic characteristics, Veterans with CUD diagnosis were at increased odds of all included physical and mental health conditions. Strongest associations were observed with substance use disorders, followed by mental health conditions, chronic pain, and mortality.

Determining the prevalence of cannabis use and CUD from the different studies of Veterans remains challenging due to wide variations in sample types, assessment measures of cannabis use/CUD, and timeframes used. However, despite these, several studies among Veterans suggested that the prevalences of cannabis use and CUD were similar to those in the general population.

In our review of the relationship of cannabis use/CUD to psychiatric disorders, some disorders were consistently related to cannabis use/CUD, but a few were not. This review indicates that Veterans with cannabis use/CUD are at an increased risk of co-occurring psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, suicidality, and pain conditions, contributing to the limited literature on these specific associations. However, while findings indicate that depressive disorders are prevalent among Veterans with cannabis use/CUD, studies of associations in different sample types using different diagnostic criteria provided somewhat mixed results. While many studies did show positive associations of cannabis use and CUD with depressive disorders, others did not, including one VHA study[28] of longitudinal associations between cannabis use variables and depression. Similarly, anxiety disorders, which until recently were almost not investigated in relation to cannabis use/CUD among Veterans, were generally shown to be positively associated with cannabis use/CUD in this population. As beliefs in the therapeutic benefits of cannabis use become increasingly common[47], investigating causal associations between cannabis use, and depression and anxiety will be essential for risk assessment. Care for Veterans should include screening for all the disorders reviewed here as well as suicide risk. In addition, considering the disproportionally high rate of chronic pain among Veterans, future studies should examine longitudinal associations between cannabis use/CUD and chronic pain.

Studies of associations of cannabis use/CUD to PTSD provided surprisingly inconsistent results. As cannabis use becomes more popular as a treatment for PTSD symptoms in this population, priority research areas should include investigations of causal associations with cannabis use/CUD, and evaluation of motivations for use (medical vs. nonmedical) and of potential effect of state-specific laws on associations.

Consistent with the prior review[12], the studies we reviewed showed that Veterans with cannabis use/CUD are at a greater risk for other substance use/SUD, especially alcohol. Due to the substantial burden of disease associated with such other substance use, prevention and harm reduction interventions (e.g., patient and healthcare provider education, improving access to healthcare services, and enhancing skills for coping with drug misuse) are of crucial importance to implement in VHA settings.

By addressing associations of CUD to mental and physical health conditions in a large (>5.5 million) sample of Veterans, using consistent analytical methods across all conditions examined, we provide additional valuable information. Our findings that all conditions included in this analysis are significantly more likely to be diagnosed in Veterans with CUD than in those without CUD are consistent with findings from past studies. For example, our finding that Veterans with CUD had significantly higher rates of any chronic pain diagnosis than Veterans without CUD corroborate findings from two studies included in our review of the literature[19, 43], while our finding that those with CUD had higher rates of multiple pain conditions than others adds new information to this literature. In another example, our findings of high rates of CUD comorbid with anxiety disorders are consistent with previous findings from a relatively limited literature, where only 3 studies showed associations between CUD and anxiety disorders in veteran populations[24, 35, 36]. Findings from our analyses also contribute important information to the literature on conditions for which associations with CUD remain controversial, depressive disorders and PTSD, two common psychiatric disorders in Veterans for which investigations on associations with CUD in veteran populations yielded mixed results. Further, no previous studies utilizing data on VHA patients assessed associations between these disorders and CUD. Notably, we provided data on associations for which there is very little or no data at all in veteran populations. For example, psychotic disorders and bipolar disorders were shown to be significantly more prevalent among Veterans with than without CUD. Our findings demonstrating that Veterans with CUD are at increased risk of mortality are important and may have individual and public health implications, especially given increasing rates of cannabis use[5, 48] and CUD[3, 49]. One prior study using electronic health record data from a non-VA system found that among patients with opioid use disorder, those who also had comorbid CUD exhibited higher mortality rates compared to those without CUD[50], which is consistent with our current finding of increased mortality among patients with CUD. Veterans with CUD have substantially higher rates of co-occurring substance use[12, 23, 24, 36], psychiatric disorders[23, 24, 40], and poorer physical health[12, 31, 43] that likely contribute to their increased risk of mortality. Further studies of VHA data are needed to parse out whether the increased mortality we found can be attributed to these co-occurring conditions, or whether CUD additionally contributes to the risk for mortality in its own right. In addition, studies using non-VHA samples are needed to determine the generalizability and robustness of our findings. If our findings do replicate, then future studies should investigate potential mediators should be investigated, including some of the variables used in the current study (e.g., chronic pain, other SUD, and suicidality), to better understand underlying mechanisms.

Limitations of the review section of this report are noted. First, meta-analysis was not conducted because of between-study variation in methodology. Second, very few studies accounted for dose-dependent effects of cannabis (e.g., frequency) on associations with correlates. Third, most studies included in this review had a cross-sectional design, and thus, the direction of effect between cannabis use/CUD and clinical correlates remains unclear. Limitations in the new analyses performed in this study are also noted. First, VHA patients are largely White males of middle age or older with high rates of medical comorbidities. Therefore, our findings may not generalize to specific Veteran populations (e.g., women) or non-VHA Veterans. Second, as with other studies using EHR data, diagnoses were based on ICD-10-CM patient encounter codes placed by VA providers. Therefore, our diagnoses likely include provider error. Third, the VA EHR does not have measures of cannabis use patterns (e.g., motives [recreational vs. medical]), so these could not be included. Fourth, subclinical psychiatric symptomatology and pain intensity are not captured in VA EHR data. Finally, findings from descriptive analyses showed relatively similar rates of CUD among Veterans in states with no cannabis legalization and in states with only medical cannabis legalization. Recently, studies have begun to investigate associations between medical and recreational law enactment and CUD prevalence in the VHA population[51], suggesting that these contribute, to some extent, to higher diagnosed CUD prevalence in Veterans. However, further comprehensive investigations of these complex relationships, especially in the context of comorbid psychiatric disorders, are needed and are currently underway.

5. CONCLUSION

Based on synthesis of the recent literature, and additional analyses carried out in this study, Veterans with cannabis use/CUD are significantly more likely to suffer from psychiatric disorders, suicidality, pain conditions, mortality, and other substance use/SUD, compared to those without cannabis use/CUD. Implications of these findings affect both clinical practice and policymaking. Changes in the legal cannabis landscape in the US will likely continue to lead to increased prescriptions of cannabis by healthcare providers and increased recreational use by Veterans. While cannabis may provide medical benefits to some, patients and healthcare professionals should be informed about the physical and mental health comorbidities associated with cannabis use. Further, policy makers should consider the growing body of evidence that raises questions about the benefit-risk ratio of cannabis use, especially among populations with increased morbidity such as Veterans.

Supplementary Material

Funding and/or Conflicts of interests/Competing interests

This study was funded by the following grants for the National Institute on Drug Abuse: R01DA048860, 1R01DA050032, T32DA031099. Dr. Saxon has received travel support from Alkermes, Inc., honorarium from Indivior, Inc., and royalties from UpToDate, Inc. Dr. Hasin has received funds from Syneos Health for an unrelated project to measure opioid addiction in chronic pain patients.

Statements and Declarations:

Dr. Saxon has received travel support from Alkermes, Inc., honorarium from Indivior, Inc., and royalties from UpToDate, Inc. Dr. Hasin has received funds from Syneos Health for an unrelated project to measure opioid addiction in chronic pain patients.

Funding:

Hasin: R01DA048860, 1R01DA050032, T32DA031099; Livne: K23DA057417.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Cannabis (Marijuana) Research Report 2020. [cited 2022 Oct 26]. Available from: https://nida.nih.gov/download/1380/cannabis-marijuana-research-report.pdf?v=7fc7d24c3dc120a03cf26348876bc1e4.

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20–07–01–001, NSDUH Series H-55) Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020. [cited 2022 Oct 26]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/.

- 3.Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Zhang H, et al. Prevalence of Marijuana Use Disorders in the United States Between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1235–42. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, Church JC, Freeman TP, ElSohly MA. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008–2017). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269(1):5–15. 10.1007/s00406-019-00983-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2021. [cited 2022 Oct 27]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/.

- 6.Hall W, Degenhardt L. The adverse health effects of chronic cannabis use. Drug Test Anal. 2014;6(1–2):39–45. 10.1002/dta.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasin DS. US Epidemiology of Cannabis Use and Associated Problems. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(1):195–212. 10.1038/npp.2017.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Workman CD, Fietsam AC, Sosnoff J, Rudroff T. Increased Likelihood of Falling in Older Cannabis Users vs. Non-Users. Brain Sci 2021;11(2). 10.3390/brainsci11020134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi NG, Marti CN, DiNitto DM, Choi BY. Older adults’ marijuana use, injuries, and emergency department visits. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(2):215–23. 10.1080/00952990.2017.1318891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han BH, Sherman S, Mauro PM, Martins SS, Rotenberg J, Palamar JJ. Demographic trends among older cannabis users in the United States, 2006–13. Addiction. 2017;112(3):516–25. 10.1111/add.13670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betancourt JA, Granados PS, Pacheco GJ, Reagan J, Shanmugam R, Topinka JB, et al. Exploring Health Outcomes for U.S. Veterans Compared to Non-Veterans from 2003 to 2019. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(5). 10.3390/healthcare9050604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turna J, MacKillop J. Cannabis use among military veterans: A great deal to gain or lose? Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;84:101958. 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayhew M, DeBar LL, Deyo RA, Kerns RD, Goulet JL, Brandt CA, et al. Development and Assessment of a Crosswalk Between ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM to Identify Patients with Common Pain Conditions. J Pain. 2019;20(12):1429–45. 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page MG, Fortier M, Ware MA, Choiniere M. As if one pain problem was not enough: prevalence and patterns of coexisting chronic pain conditions and their impact on treatment outcomes. J Pain Res. 2018;11:237–54. 10.2147/JPR.S149262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Veteran Affairs. VHA directive 2008–036–Use of patient record flags to identify patients at high risk for suicide 2008 [cited 2022 Oct 26]. Available from: https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=1719.

- 17.Browne KC, Stohl M, Bohnert KM, Saxon AJ, Fink DS, Olfson M, et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Cannabis Use and Cannabis Use Disorder Among U.S. Veterans: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC-III). Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(1):26–35. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.20081202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill ML, Loflin M, Nichter B, Norman SB, Pietrzak RH. Prevalence of cannabis use, disorder, and medical card possession in U.S. military veterans: Results from the 2019–2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Addict Behav. 2021;120:106963. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Browne K, Leyva Y, Malte CA, Lapham GT, Tiet QQ. Prevalence of medical and nonmedical cannabis use among veterans in primary care. Psychol Addict Behav. 2022;36(2):121–30. 10.1037/adb0000725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoggatt KJ, Harris AHS, Washington DL, Williams EC. Prevalence of substance use and substance-related disorders among US Veterans Health Administration patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;225:108791. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Compton WM, Han B, Hughes A, Jones CM, Blanco C. Use of Marijuana for Medical Purposes Among Adults in the United States. JAMA. 2017;317(2):209–11. 10.1001/jama.2016.18900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lev-Ran S, Roerecke M, Le Foll B, George TP, McKenzie K, Rehm J. The association between cannabis use and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2014;44(4):797–810. 10.1017/S0033291713001438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill ML, Loflin M, Nichter B, Na PJ, Herzog S, Norman SB, et al. Cannabis use among U.S. military veterans with subthreshold or threshold posttraumatic stress disorder: Psychiatric comorbidities, functioning, and strategies for coping with posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Trauma Stress. 2022;35(4):1154–66. 10.1002/jts.22823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill ML, Nichter BM, Norman SB, Loflin M, Pietrzak RH. Burden of cannabis use and disorder in the U.S. veteran population: Psychiatric comorbidity, suicidality, and service utilization. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:528–35. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryan JL, Hogan J, Lindsay JA, Ecker AH. Cannabis use disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder: The prevalence of comorbidity in veterans of recent conflicts. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;122:108254. 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunn RL, Stevens AK, Micalizzi L, Jackson KM, Borsari B, Metrik J. Longitudinal associations between negative urgency, symptoms of depression, cannabis and alcohol use in veterans. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;28(4):426–37. 10.1037/pha0000357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillon KH, Van Voorhees EE, Elbogen EB, Beckham JC, Workgroup VAM-AM, Calhoun PS. Cannabis use disorder, anger, and violence in Iraq/Afghanistan-era veterans. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;138:375–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livingston NA, Farmer SL, Mahoney CT, Marx BP, Keane TM. Longitudinal course of mental health symptoms among veterans with and without cannabis use disorder. Psychol Addict Behav. 2022;36(2):131–43. 10.1037/adb0000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stiles-Shields C, Archer J, Zhang J, Burnside A, Draxler J, Potthoff LM, et al. A Scoping Review of Associations Between Cannabis Use and Anxiety in Adolescents and Young Adults. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2021. 10.1007/s10578-021-01280-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urits I, Gress K, Charipova K, Li N, Berger AA, Cornett EM, et al. Cannabis Use and its Association with Psychological Disorders. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2020;50(2):56–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart KL, Farris SG, Jackson KM, Borsari B, Metrik J. Cannabis Use and Anxiety Sensitivity in Relation to Physical Health and Functioning in post-9/11 Veterans. Cognit Ther Res. 2019;43(1):45–54. 10.1007/s10608-018-9950-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Metrik J, Jackson K, Bassett SS, Zvolensky MJ, Seal K, Borsari B. The mediating roles of coping, sleep, and anxiety motives in cannabis use and problems among returning veterans with PTSD and MDD. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(7):743–54. 10.1037/adb0000210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reilly ED, Chamberlin ES, Duarte BA, Harris JI, Shirk SD, Kelly MM. The Impact of COVID-19 on Self-Reported Substance Use, Well-Being, and Functioning Among United States Veterans: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Psychol. 2022;13:812247. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.812247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tran DD, Fitzke RE, Wang J, Davis JP, Pedersen ER. Substance Use, Financial Stress, Employment Disruptions, and Anxiety among Veterans during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol Rep. 2022:332941221080413. 10.1177/00332941221080413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedersen ER, Davis JP, Prindle J, Fitzke RE, Tran DD, Saba S. Mental health symptoms among American veterans during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021;306:114292. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill ML, Nichter B, Loflin M, Norman SB, Pietrzak RH. Comparative associations of problematic alcohol and cannabis use with suicidal behavior in U.S. military veterans: A population-based study. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;135:135–42. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selloni A, Bhatia G, Ranganathan M, De Aquino JP. Multimodal Correlates of Cannabis Use among U.S. Veterans with Bipolar Disorder: An Integrated Study of Clinical, Cognitive, and Functional Outcomes. J Dual Diagn. 2022;18(2):81–91. 10.1080/15504263.2022.2053264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metrik J, Stevens AK, Gunn RL, Borsari B, Jackson KM. Cannabis use and posttraumatic stress disorder: prospective evidence from a longitudinal study of veterans. Psychol Med. 2022;52(3):446–56. 10.1017/S003329172000197X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauer MS, Altshuler L, Evans DR, Beresford T, Williford WO, Hauger R, et al. Prevalence and distinct correlates of anxiety, substance, and combined comorbidity in a multi-site public sector sample with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;85(3):301–15. 10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ecker AH, Lang B, Hogan J, Cucciare MA, Lindsay J. Cannabis use disorder among veterans: Comorbidity and mental health treatment utilization. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;109:46–9. 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grove JL, Kimbrel NA, Griffin SC, Halverson T, White MA, Blakey SM, et al. Cannabis use and suicide risk among Gulf War veterans. Death Stud. 2022:1–6. 10.1080/07481187.2022.2108944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hefner K, Sofuoglu M, Rosenheck R. Concomitant cannabis abuse/dependence in patients treated with opioids for non-cancer pain. Am J Addict. 2015;24(6):538–45. 10.1111/ajad.12260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enkema MC, Hasin DS, Browne KC, Stohl M, Shmulewitz D, Fink DS, et al. Pain, cannabis use, and physical and mental health indicators among veterans and nonveterans: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. Pain. 2022;163(2):267–73. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang H, Hunniecutt J, Quintero Silva L, Kaskie B, Bobitt J. Biopsychosocial factors and health outcomes associated with cannabis, opioids and benzodiazepines use among older veterans. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(4):497–507. 10.1080/00952990.2021.1903479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasin D, Walsh C. Cannabis Use, Cannabis Use Disorder, and Comorbid Psychiatric Illness: A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2020;10(1). 10.3390/jcm10010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Metrik J, Bassett SS, Aston ER, Jackson KM, Borsari B. Medicinal versus Recreational Cannabis Use among Returning Veterans. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2018;4(1):6–20. 10.1037/tps0000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sexton M, Cuttler C, Finnell JS, Mischley LK. A Cross-Sectional Survey of Medical Cannabis Users: Patterns of Use and Perceived Efficacy. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016;1(1):131–8. 10.1089/can.2016.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, Hughes A. Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002–14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(10):954–64. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C. Cannabis use disorders among adults in the United States during a time of increasing use of cannabis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107468. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hser YI, Mooney LJ, Saxon AJ, Miotto K, Bell DS, Zhu Y, et al. High Mortality Among Patients With Opioid Use Disorder in a Large Healthcare System. J Addict Med. 2017;11(4):315–9. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hasin DS, Wall MM, Choi CJ, Alschuler DM, Malte C, Olfson M, et al. State Cannabis Legalization and Increases in Cannabis Use Disorder in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration, 2005 to 2019. JAMA Psychiatry. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.