Abstract

Introduction

Medical educators have often perpetuated misunderstandings about race-based medicine and at times failed to create safe educational environments for diverse learners who frequently experience mistreatment. It is imperative that family medicine faculty be equipped to recognize and mitigate bias and inequities in our teaching, research, and clinical care.

Methods

Our residency formed a diversity, equity, inclusion, and antiracism (DEIA) faculty work group to address the need for faculty training. We developed and administered a 32-item needs assessment survey in 2020 to determine gaps in antiracist knowledge and skills among our faculty members. Over the following year, faculty members designed and implemented a series of faculty training sessions including a half-day faculty retreat to address the highest need areas. We reassessed faculty confidence and skills using a follow-up survey in 2021.

Results

Faculty respondents demonstrated increased confidence in their knowledge of various DEIA topics and ability to intervene when observing biased or culturally insensitive behaviors from colleagues. Participants also reported increased confidence in their ability to mitigate bias in their teaching and clinical work.

Conclusions

Our longitudinal DEIA faculty training series, embedded into the existing structure of the residency, resulted in improvements in DEIA-related confidence and skills among faculty members. This training model could be adapted to a variety of residency settings as one step toward dismantling racism in medical education and clinical practice.

Introduction

Historically, medical curricula have sometimes perpetuated misunderstandings about race1. When we teach about racial differences in medicine as race-based biological differences rather than reflections of the impact of systemic racism, health disparities are exacerbated.2,3 As medical educators, we must be adept at teaching and speaking up about racism and its impact on our patients, learners, and ourselves.4

A previous study found that most family medicine residency program directors believe racial justice curricula should be included during residency; however, lack of faculty training was the greatest barrier to implementation.5 There is also a need for more robust faculty development in addressing mistreatment of trainees.6–9 An annual climate survey in our residency found higher burnout rates for underrepresented minorities, persons of color, and LGBTQ+ respondents, and significant racial and gender differences in reporting discrimination and harassment.10 Our program’s diversity, equity, inclusion, and antiracism (DEIA) faculty work group formed in 2020 in response to these needs.

Methods

In the fall of 2020, our DEIA faculty work group developed and administered an anonymous, 32-item needs assessment survey, adapted from existing surveys from other institutions, to assess faculty attitudes, knowledge, and skills necessary for addressing health inequities and racism (Jennifer Edgoose, MD, MPH, e-mail communication, August 2020).11–13 Demographic data, including ethnicity, and gender, were collected. The survey was pretested for comprehension and feasibility among a small group of faculty then distributed via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) to a residency faculty list serv.14,15

Initial survey results revealed that faculty had lower confidence in their ability to describe intersectionality and the origins of racial classification, and less confidence and skills to facilitate conversations about bias and racism with learners and patients. Over the next year, faculty work group members designed and implemented a series of faculty development sessions on these topics, including an interactive workshop during an annual faculty retreat where participants assessed our institution as an antiracist organization and practiced upstander behaviors (Table 1)10,16–22 Faculty participation in the training sessions was optional, though they occurred during standing meeting times where most core faculty and some adjunct faculty were present. We chose a longitudinal approach, rather than single-day trainings or modules, in hopes of creating more durable cultural change.23–25

Table 1.

Faculty Training Sessions

| Date | Setting | Title | Duration (min) | Description and Key Resources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aug, Sept 2020 | Faculty meetings; virtual | White Privilege in Medicine | 45 |

|

| Nov 2020 | Initial survey administered | |||

| Nov 2020, Feb 2021 | Faculty meetings; virtual | Microaggressions | 45 | |

| Feb, May 2021 | Faculty meetings; virtual | Race and Medicine | 60 | |

| June 2021 | Joint faculty and resident racial affinity caucusing | Intersectionality | 45 |

|

| Sept 2021 | Annual faculty retreat; in person | Assessing Institutional Antiracism | 45 |

|

| Microaggressions and Upstander training | 120 | |||

| Sept–Oct 2021 | Follow-up survey administered | |||

| Nov 2021 | Annual inpatient medicine attending retreat; hybrid | Addressing Learner Mistreatment | 60 | |

Abbreviations: URM, underrepresented minority: Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, or Native American or Alaskan Native; 4 D’s, Direct, Distract, Delegate, Debrief

In the fall of 2021, at the conclusion of the faculty retreat and over the following month, we disseminated the same survey to the residency faculty list serv. We analyzed survey results using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS, Inc, Cary, NC). In addition to descriptive statistics, we used Fisher’s Exact test to determine whether there were any statistically significant changes in responses from the pre- to postsurvey, using a P value of .05 for significance. Individual pre- and postsurvey responses could not be matched as the survey was distributed through an anonymous link. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board determined this evaluation to be exempt due to the focus on quality improvement.

Results

Faculty presence at our training sessions was on par with usual attendance at those meetings. Response rates for the pre- and postsurveys were 54% (39/72) and 32% (28/87), respectively (notably, additional adjunct faculty were added to the list serv in the interim period). The demographics of respondents were reflective of our residency faculty overall: the majority were White and female (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic Profile of Survey Respondents

| Characteristics | Pre (N=39) n (%) |

Post (N=28) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color (yes) | 2 (5.1) | 1 (3.6) |

| White (non-Hispanic) (yes) | 31 (79.5) | 20 (71.4) | |

| Latinx (yes) | 4 (10.3) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Asian (yes) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (7.1) | |

| Biracial or multiracial (yes) | 3 (7.7) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Professional role | Administrative staff | 1 (2.6) | 2 (7.1) |

| Faculty | 37 (94.9) | 26 (92.9) | |

| Other | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Gender identity | N/A | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Female | 25 (64.1) | 20 (71.4) | |

| Male | 12 (30.8) | 8 (28.6) | |

| Choose not to disclose | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Length of time in profession | 0–5 years | 13 (33.3) | 11 (39.3) |

| 6–10 years | 8 (20.5) | 8 (28.6) | |

| 11–15 years | 5 (12.8) | 2 (7.1) | |

| >15 years | 13 (33.3) | 7 (25.0) | |

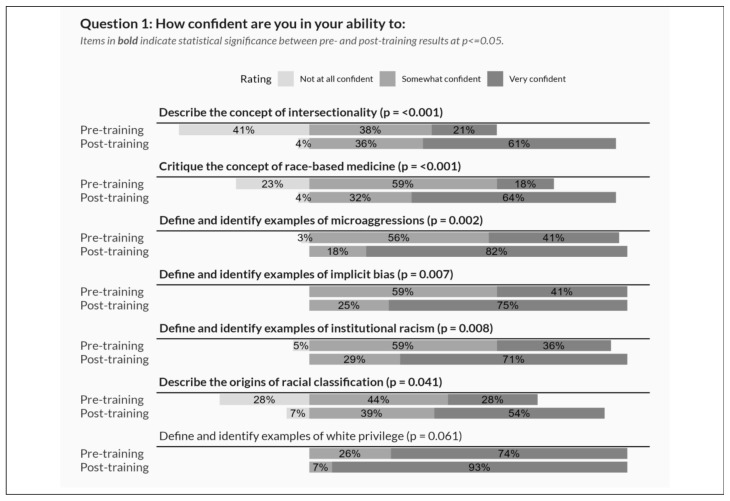

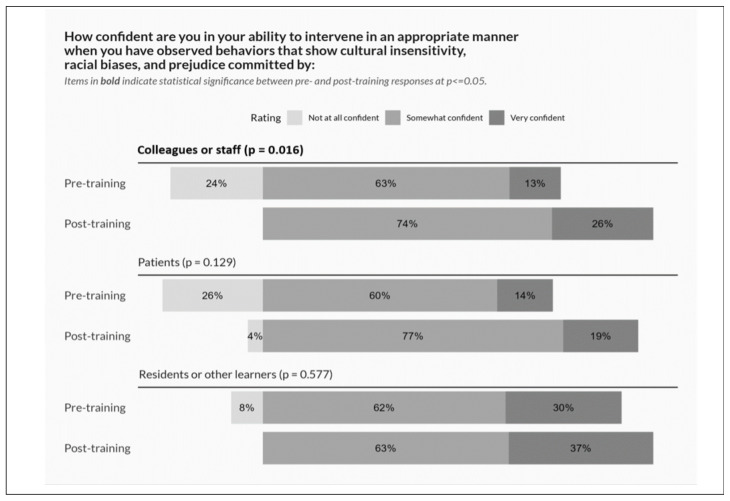

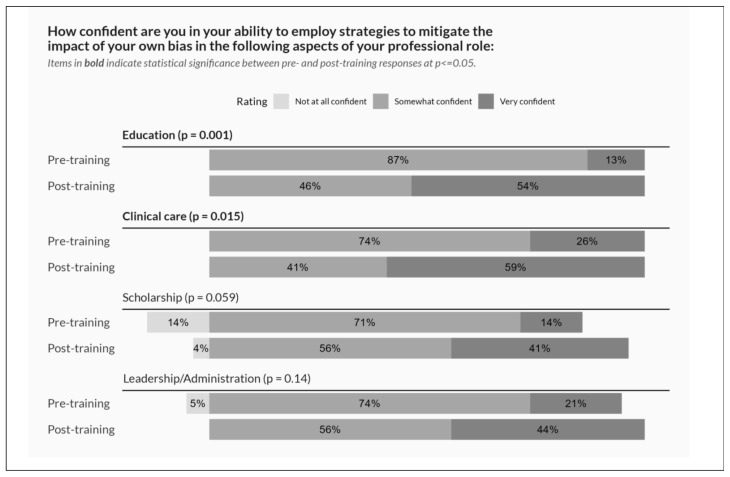

Participants showed increased confidence between the pre- and postsurveys on six of the seven items that assessed familiarity with DEI concepts, including the ability to describe intersectionality and institutional racism (Figure 1). Participants rated their confidence in intervening when observing behaviors that show cultural insensitivity, racial biases, and prejudice. There were statistically significant increases when addressing behaviors exhibited by colleagues/staff, but not by residents/learners or patients (Figure 2). Participants also reported increased confidence in their ability to mitigate the impact of their own bias in the areas of education and clinical care, but not in scholarship or leadership/administration (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Confidence in knowledge of DEI topics

Figure 2.

Confidence in intervening on acts of bias, prejudice

Figure 3.

Confidence in Ability to Mitigate Bias

A series of questions that assessed personal development of antiracist skills (such as reflecting on cultural context in one's professional role, educating oneself on the culture and experience of others, and developing inclusive practices) did not change significantly between pre- and postsurveys. All respondents reported that they were somewhat or very likely to incorporate learnings from the topics presented at the retreat into teaching and clinical practice.

Conclusions

Following a series of faculty development sessions, residency faculty reported increased confidence in knowledge of DEIA concepts, confidence in intervening on acts of bias committed by colleagues or staff, and ability to mitigate their own bias and address inequity in their educational and clinical roles. Our approach demonstrates the feasibility of improving faculty confidence and skills in DEIA work through relatively brief sessions that are integrated into existing residency structures.

Our study has several key limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. We developed our survey in 2020 amidst national racial justice movements with a keen awareness of the urgent need to improve DEIA work in our residency. Our assessment of self-reported confidence and behaviors provided us with a quick snapshot of our current state and allowed for efficient planning and implementation of educational sessions in which we already had some degree of faculty buy-in. However, this study design limited the robustness of our postintervention assessment to the lowest levels of the Kirkpatrick Model of Assessment.26 Future research in this area should assess higher-level outcomes, such as such as peer and learner assessments of faculty behavior (ie, response to microaggressions), learners’ educational outcomes (ie, ability to critique race-based medicine), and health outcomes (ie, racial health disparities among patients). Other limitations include (1) implementation at a single residency, (2) social desirability and selection biases that may have influenced participants’ responses, (3) pre/postsurvey responses that were not matched to each participant, and (4) administering the postintervention survey soon after the retreat rather than at an extended interval.

Family medicine residencies must equip their faculty to examine and respond to the racism and injustice that are embedded in medicine and medical education27,28 In turn, faculty members can train residents in antiracist principles and begin to address misunderstandings of race perpetuated in medical curricula. Our longitudinal, multipronged approach to DEIA faculty training could be adapted to a variety of residency settings as one step toward dismantling racism in medical education and clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dionisia de la Cerda, MPA for assistance with survey creation and administration, Elizabeth Staton, Corey Lyon, Jodi Holtrop and Carlee Kreisel for manuscript review, and our residency program leadership for their continued support of diversity, equity, inclusion, and antiracism initiatives.

Presentations: This study was presented at the STFM Annual Spring Conference, May 4, 2022 in Indianapolis, Indiana.

References

- 1. Amutah C, Greenidge K, Mante A, et al. misrepresenting race - the role of medical schools in propagating physician bias. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):872–878. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2025768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1125–1128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight - reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):874–882. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2004740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peek ME, Vela MB, Chin MH. Practical lessons for teaching about race and racism: successfully leading free, frank, and fearless discussions. Acad Med. 2020;95(12S Addressing Harmful Bias and Eliminating Discrimination in Health Professions Learning Environments):S139–S144. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wusu MH, Baldwin M, Semenya AM, Moreno G, Wilson SA. Racial justice curricula in family medicine residency programs: a cera survey of program directors. Fam Med. 2022;54(2):114–122. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.189296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bullock JL, O’Brien MT, Minhas PK, Fernandez A, Lupton KL, Hauer KE. No one size fits all: a qualitative study of clerkship medical students’ perceptions of ideal supervisor responses to microaggressions. Acad Med. 2021;96(11S):S71–S80. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldenberg MN, Cyrus KD, Wilkins KM. ERASE: a new framework for faculty to manage patient mistreatment of trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(4):396–399. doi: 10.1007/s40596-018-1011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guh J, Harris CR, Martinez P, Chen FM, Gianutsos LP. antiracism in residency: a multimethod intervention to increase racial diversity in a community-based residency program. Fam Med. 2019;51(1):37–40. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.987621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vela MB, Chin MH, Peek ME. Keeping our promise — supporting trainees from groups that are underrepresented in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):487–489. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2105270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith R, Johnson A, Targan A, Piggott C, Kvach E. Taking our own temperature: using a residency climate survey to support minority voices. Fam Med. 2022;54(2):129–133. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.344019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehn C, Kvach E, Piggot C, et al. Faculty DEI Knowledge and Skills Survey 2023. STFM Resource Library. [Accessed July 5, 2022]. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/faculty-dei-confidence-and-skills-s?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments .

- 12.Anti-Defamation Leagure. Personal Self-Assessment of Anti-Bias Behavior. https://lit-together.org/wp-content/uploads/personal-self-assessment-of-anti-bias-behavior-online-version_0.pdf .

- 13.Wheat S, Wright K, Edberg D.Social justice curriculum: one step toward change. STFM Education Column. [Accessed July 5, 2022]. Published June 2022. https://stfm.org/publicationsresearch/publications/educationcolumns/2022/june/

- 14. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Race & Medicine Caucusing Activity: White Privilege. [Accessed June 13, 2023]. https://www.raceandmedicine.com/white-physician-privilege .

- 17.Edgoose J, et al. Toolkit for Teaching About Racism in the Context of Persistent Health and Healthcare Disparities. STFM Resource Library; May, 2017. [Accessed July 25, 2022]. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/toolkit-for-teaching-about-racism-i?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments . [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race-based to race-conscious medicine: how anti-racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1125–1128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Amutah C, Greenidge K, Mante A, et al. Misrepresenting race - the role of medical schools in propagating physician bias. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):872–878. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2025768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The University of Texas at El Paso DOT Initiative. The Three D’s of D.O.T Intervention: Direct, Distract, and Delegate. [Accessed July 25, 2022]. https://www.utep.edu/initiatives/dot/about/green-dot-programs.html .

- 21.Willoughby B.Speak Up at School: How to Respond to Everyday Prejudice, Bias, and Stereotypes. Teaching Tolerance: A Project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. 2018. [Accessed July 25, 2022]. https://www.tolerance.org/sites/default/files/2019-04/TT-Speak-Up-Guide.pdf .

- 22. Bullock JL, O’Brien MT, Minhas PK, Fernandez A, Lupton KL, Hauer KE. No one size fits all: a qualitative study of clerkship medical students’ perceptions of ideal supervisor responses to microaggressions. Acad Med. 2021;96(11S):S71–S80. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. White-Davis T, Edgoose J, Brown Speights JS, et al. addressing racism in medical education an interactive training module. Fam Med. 2018;50(5):364–368. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.875510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Washington JC, Rodríguez JE. Racism education is needed at all levels of training. Fam Med. 2018;50(9):711–712. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.424750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Edgoose J, Brown Speights J, White-Davis T, et al. Teaching about racism in medical education: a mixed-method analysis of a train-the-trainer faculty development workshop. Fam Med. 2021;53(1):23–31. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.408300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels. 3rd ed. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Acosta D, Ackerman-Barger K. breaking the silence: time to talk about race and racism. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):285–288. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sotto-Santiago S, Poll-Hunter N, Trice T, et al. A framework for developing antiracist medical educators and practitioner-scholars. Acad Med. 2022;97(1):41–47. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]