Abstract

Objective

Jaw symptoms can be a vital clue to the diagnosis of GCA. Guidelines recommend more intensive treatment if jaw claudication is present. We sought to explore how patients with GCA described their jaw symptoms.

Methods

We carried out a secondary, qualitative analysis of interview data from 36 participants from the UK (n = 25) and Australia (n = 11), originally collected in order to develop a patient-reported outcome measure for GCA. In all cases, GCA had been confirmed by biopsy/imaging. Interview transcripts were organized within QSR NVivo 12 software and analysed using template analysis. Themes were refined through discussion among the research team, including a patient partner.

Results

Twenty of 36 participants reported jaw symptoms associated with GCA. The median age of these 20 participants was 76.5 years; 60% were female. Five themes were identified: physical sensations; impact on function; impact on diet; symptom response with CSs; and attribution to other causes. Physical sensations included ache, cramp, stiffness and ‘lockjaw’. Functional impacts included difficulty in eating/chewing, cleaning teeth, speaking or opening the mouth. Dietary impacts included switching to softer food. Response to CSs was not always immediate. Jaw symptoms were initially mis-attributed by some participants to arthritis, age or viral illnesses; or by health-care professionals to a dental cavity, ear infection or teeth-grinding.

Conclusion

Jaw symptoms in GCA are diverse and can lead to diagnostic confusion with primary temporomandibular joint disorder, potentially contributing to delay in GCA diagnosis. Further research is needed to determine the relationship of jaw stiffness to jaw claudication.

Keywords: giant cell arteritis, temporal arteritis, jaw claudication, symptoms

Key messages.

Jaw symptoms in GCA include stiffness, in addition to claudication.

Both stiffness and claudication can affect jaw function, leading to dietary modification.

Jaw symptoms of GCA may be mis-attributed to other causes, causing diagnostic delay.

Introduction

GCA is the commonest primary systemic vasculitis. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment with high-dose glucocorticoid are crucial to avert visual loss. Jaw claudication in GCA was originally described by Horton as pain that ‘occurred only with chewing and promptly disappeared with rest’ [1]. It has been formally defined as ‘development or worsening of fatigue in the muscles of mastication while eating’ [2] and is understood as a manifestation of ischaemia to these muscles. In a recent meta-analysis, jaw claudication was the GCA feature with highest diagnostic odds ratio [3]. Furthermore, patients presenting with jaw claudication are more likely to have visual loss at presentation [4].

EULAR recommends that return of active GCA accompanied by jaw claudication constitutes ‘major relapse’ and requires treatment as for new-onset disease, whereas ‘minor relapses’ can be treated by returning to the last effective glucocorticoid dose [5]. For disease relapse with symptoms of cranial ischaemia, the ACR guidelines recommend adding a non-glucocorticoid immunosuppressant and increasing the glucocorticoid dose [6]. Jaw claudication, by definition a cranial ischaemic symptom, thus has major implications for both diagnosis and treatment of GCA.

In 1962, Horton wrote: ‘I finally realized, during the years 1942–44, that the pain of chewing referred to by patients as difficulty in chewing or “lockjaw” is an exercise phenomena and represents intermittent claudication of the jaw’ [7]. Reminiscent of Horton’s words, a recent international qualitative study [8] to develop a patient-reported outcome measure reported that patients with GCA described jaw stiffness in addition to jaw pain. In this study, we conducted a secondary analysis of this qualitative dataset with the aim of exploring the range of patient-reported jaw symptoms in GCA.

Methods

Design

We conducted a secondary analysis of qualitative data from interviews conducted for a study to develop a patient-reported outcome measure for GCA [8]. The primary analysis found that participants described a variety of jaw symptoms; this secondary analysis was therefore conducted to explore this aspect further. The original study obtained ethical approval in the UK (South Central—Oxford B Research Ethics Committee; REC reference: 16/SC/0697, IRAS project ID: 217748) and Australia (Central Adelaide Local Health Network; HREC reference: HREC/17/TQEH/275 and CALHN reference: Q20170906). All patients provided written informed consent.

Data collection and participants

In the original study, participants were recruited using purposive sampling from two rheumatology clinics and one ophthalmology clinic in the UK (n = 25) and Australia (n = 11). All participants had a definite diagnosis of GCA confirmed by at least one diagnostic test (temporal artery biopsy, temporal artery US, CT angiogram or PET scan). Interviews were recorded, transcribed and anonymized. In the present study, transcripts were organized within one QSR NVivo 12 database.

Analysis

A priori themes, namely description of jaw symptoms, impact on daily activities and impact on diet, were determined from initial discussion among the researchers (J.L., E.D., J.R. and S.L.M.) to facilitate the initial coding process. These were selected based on clinical significance and relevance to the research question. J.L. read all the anonymized transcripts and coded segments of text related to the research question and topic. A subset of transcripts was initially coded. Codes were then grouped into themes and sub-themes, and the whole dataset of interviews was re-reviewed to ensure completion of data.

J.L. discussed the analysis with J.R., E.D., S.L.M. and a patient partner (L.F.B.) to ensure that different viewpoints were considered. Themes were redefined and revised following these discussions.

Results

Of the 36 participants with GCA, 20 (58%) reported jaw symptoms. Of these, the median age was 76.5 years; 60% were female. Specific demographics have been described previously [8].

Physical sensations

Physical sensations reported were primarily in the jaw and, to a lesser extent, in the ear and face.

Participants commonly reported jaw pain/ache/cramp that occurred when eating and resolved with rest.

To eat a meal, I’d have to keep stopping, because my jaw ached…and I’d have to stop, rest and then eat a bit more and stop and rest and carry on like that. (Female, 83 years old, UK)

I could only do a few attempts at chewing something and swallowing it. Internally, deep inside, it became sore and a sort of cramp… (Male, 79 years old, Australia)

Several participants described jaw stiffness or ‘lockjaw’.

…because my first symptom of all was the jaws, very stiff jaws, very painful to eat… (Female, 72 years old, UK)

…and a very stiff jaw, which affected my eating. (Male, 81 years old, UK)

I get a lock in the jaw up here sometimes, which is the same side as what I had, you know. (Male, 72 years old, UK)

Jaw symptoms were sometimes associated with other non-headache symptoms, including pain or altered sensation in the ear (or around the back of the ear), face, teeth and tongue. Some participants reported ‘swelling’ of the mouth or tongue.

Impact on function

Jaw symptoms impacted oral functions including chewing, cleaning the teeth, opening the mouth and speaking.

Yes, the jaw ache, that was what worried me then, and then I could hardly bite an apple… (Female, 78 years old, UK)

…I got to the stage when occasionally I couldn’t open my mouth to, er, clean with a small electric toothbrush, I guess… (Female, 78 years old, UK)

When pain was severe, it could impact on sleep.

…it was difficult to sleep. Oh, everything, and it was absolutely excruciating, I told him what such pain I’m in, I said, ‘I can hardly speak, I can hardly open my mouth’… (Female, 64 years old, UK)

Impact on diet

Dietary modifications reported by participants included a shift to a soft or liquid diet. This was not only attributable to classical jaw claudication symptoms but also to their difficulty in opening the mouth wide enough to accommodate a sandwich or even a large spoon.

All me jaws was hurting, oh that was painful.… So, I was living on soups and tins of rice. (Female, 79 years old, UK)

…and I was having to use a teaspoon for cereal… (Female, 78 years old, UK)

Some participants reported eating less and losing weight, whereas others reported eating more slowly but not necessarily eating less.

Response to glucocorticoid therapy

Some participants reported an immediate response of jaw symptoms to glucocorticoid therapy. For others, the symptoms were much slower to resolve.

Attribution to other causes

Participants attempted to make sense of their symptoms in various ways, often attributing their jaw symptoms to arthritis, old age or intercurrent infection.

I probably put up with it for a long time, because of other aches and pains, and I’ve got arthritis in my jaw now, sort of thing. (Female, 66 years old, UK)

I just—I think it’s something to do with my age, you know, you don’t go to the doctor. (Female, 71 years old, Australia)

I just put it down to, you know, being in the cabin at the, erm, aircraft, how you often get these viruses and things, erm, and so I didn’t take a lot of notice of it. (Female, 73 years old, UK)

One participant with PMR initially surmised that their jaw symptoms were attributable to their glucocorticoid therapy:

Pain in the teeth and jaw, terrible pain; I woke up at about 3 o’clock every morning thinking these are probably the side effects of the medication I’m taking for the polymyalgia—I hadn’t been warned at that stage that I could have got giant cell. (Female, 71 years old, Australia)

On seeking advice from health-care professionals, jaw symptoms were not always recognized as GCA immediately.

Because I had an actual appointment within a few days. And the dentist said, ‘There’s nothing really wrong, unless you may have, um, a cavity or something’. And she said, ‘Gargle with salt water.’. (Female, 64 years old, UK)

‘No, it’s fine’, he [eye doctor] said, went like this, whatever, ‘Grinding your teeth’, he said, ‘That’s the problem, nothing’s wrong, off you go’… (Female, 64 years old, UK)

…he [general practitioner] thought the antibiotics would have cured, ’cos he thought I had an infection. (Female, 64 years old, UK)

They said, ‘Well, perhaps it’s middle ear infection’. (Female, 67 years old, UK)

Table 1 provides further illustrative quotations under these themes.

Table 1.

Overview of themes and sub-themes with illustrative quotes

| Themes | Selected quotations |

|---|---|

| 1. Physical sensations | |

| Jaw pain |

|

| Cramp |

|

| Jaw stiffness |

|

| Lockjaw |

|

| Ear pain |

|

| Face pain |

|

| Teeth pain |

|

| Tongue ache, felt too big |

|

| Swelling |

|

| 2. Impact on function | |

| Jaw/mouth opening |

|

| Moving face |

|

| Chewing/Eating |

|

| Cleaning teeth |

|

| Speaking |

|

| Sleeping |

|

| 3. Impact on diet | |

| Change in food consistency |

|

| Change in cutlery |

|

| Eating less |

|

| Eating slower |

|

| 4. Symptom response with steroids | |

| Fast response |

|

| Slower response |

|

| 5. Attribution to other causes | |

| Health-care professionals: dental cavity, infection, teeth grinding |

|

| Patient: arthritis, age, viral illness |

|

Discussion

We conducted a secondary analysis of interview data and found a wide range of jaw symptoms in GCA. For some participants, ‘stiffness’ of the jaw affected functions related to mouth opening, including talking, teeth cleaning or accommodating cutlery. Other authors have previously reported that reduction in jaw opening (trismus) is ‘an overlooked feature of GCA’ [9, 10]. This could be detected upon clinical examination of the jaw or might also be described by patients as difficulty in mouth or jaw opening [10]. For some participants, difficulty in opening the mouth had an even greater functional impact than difficulty in exerting force during chewing; some participants compensated for this by eating more slowly, whereas others shifted to a soft or liquid diet. Some reported weight loss. Misattribution of jaw symptoms not typical for ‘textbook’ jaw claudication might have contributed to diagnostic delay in some patients. Many of the accompanying symptoms of the tongue or ear would have been compatible with GCA but might also have served as ‘red herrings’ until the GCA diagnosis was suspected.

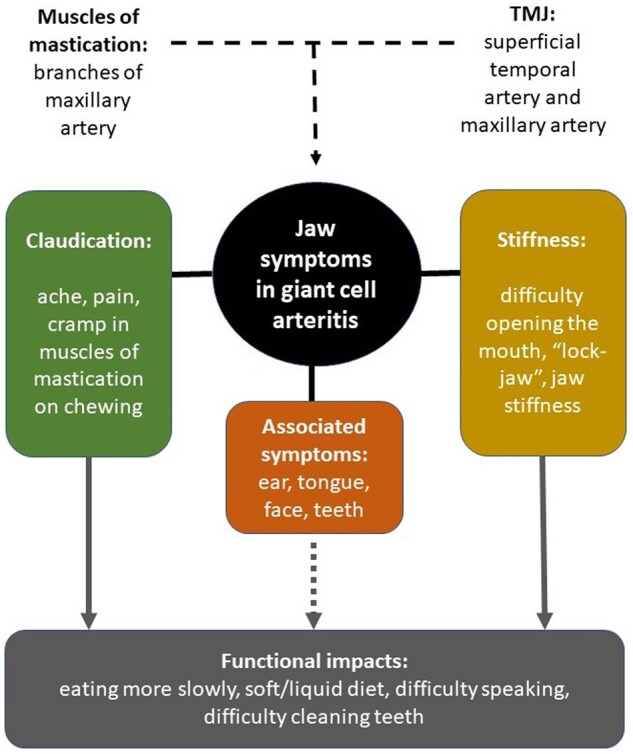

The external carotid artery has two terminal branches: the superficial temporal artery and the maxillary artery. Branches of the second part of the maxillary artery (deep temporal artery, masseteric artery and pterygoid branch) supply the muscles of mastication (temporalis, masseter and medial pterygoid), which are responsible for biting down with force, likely to be involved in the ‘textbook’ jaw claudication symptoms commonly reported by patients with GCA. The pterygoid branch of the maxillary artery also supplies the lateral pterygoid muscle, assists in opening the mouth and is necessary for the precise positioning of the mandible required for speaking [11] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A proposed typology of jaw symptoms in giant cell arteritis

Mouth opening can usually be accomplished by gravity alone; therefore, ‘stiffness’ or difficulty in opening the mouth suggests that the temporomandibular joint itself might sometimes be affected in GCA. In line with Horton’s original suggestion, this too could be an ischaemic phenomenon. The temporomandibular joint itself is supplied by a rich arterial plexus, mostly from the superficial temporal artery, with some contribution from the maxillary artery [12].

Jaw claudication has a well-established association with visual loss, but the same might be true of jaw stiffness: reduced jaw opening (trismus), present in 7% of GCA patients, is associated with visual manifestations in GCA [10]. It is currently unclear whether jaw stiffness should be considered an ischaemic manifestation with the same diagnostic and treatment implications as jaw claudication in GCA.

A limitation of our study is that it was a secondary analysis; the original data collection was not designed to answer our specific question, and clarifying questions about jaw symptoms were not part of the original interview protocol. Therefore, although all participants had GCA confirmed by biopsy or imaging, we did not ask about a history of prior temporomandibular joint disorder. However, the symptoms were all glucocorticoid responsive. Lastly, participants came from the South of England and Australia; language used for jaw symptoms might differ elsewhere.

This is the first study to describe jaw symptoms in GCA from the perspective of patients. Participants recruited had different demographics, educational levels and disease characteristics, ensuring that perspectives from various backgrounds were considered [13]. People with GCA reported not only jaw claudication but also jaw stiffness and difficulties with mouth opening that affected many important everyday functions. In the context of previous literature, it appears likely that these are part of the spectrum of GCA symptoms of which clinicians, including dentists and ophthalmologists, should be aware. Confirmation of this suggestion and investigation of the implications for disease stratification and treatment require further research.

Contributor Information

Joyce Lim, Department of Rheumatology, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, UK.

Emma Dures, School of Health and Social Wellbeing, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK; Academic Rheumatology, Bristol Royal infirmary, Bristol, UK.

Lawrence F Bailey, Patient and Public Involvement Group, Leeds Biomedical Research Centre, Leeds, UK.

Celia Almeida, School of Health and Social Wellbeing, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK.

Carlee Ruediger, Rheumatology Unit, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Woodville, South Australia, Australia; and the University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

Catherine L Hill, Rheumatology Unit, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Woodville, South Australia, Australia; and the University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

Joanna C Robson, School of Health and Social Wellbeing, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK; Academic Rheumatology, Bristol Royal infirmary, Bristol, UK.

Sarah L Mackie, Leeds Biomedical Research Centre, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, UK; Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Data availability

Data are available upon request, please contact Dr Joanna Robson.

Funding

No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Disclosure statement: S.L.M. reports: consultancy on behalf of her institution for Roche/Chugai, Sanofi, AbbVie, AstraZeneca; investigator on clinical trials for Sanofi, GSK, Sparrow; speaking/lecturing on behalf of her institution for Roche/Chugai, Vifor, Pfizer, UCB and Novartis; chief investigator on STERLING-PMR trial, funded by NIHR; patron of the charity PMRGCAuk. No personal remuneration was received for any of the above activities. Support from Roche/Chugai to attend EULAR2019 in person and from Pfizer to attend ACR Convergence 2021 virtually. S.L.M. is supported in part by the NIHR Leeds Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the NIHR Leeds Biomedical Research Centre, the National Health Service or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. The remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Horton B. Symposium: head and face pain; medicine. Tr Am Acad Ophth 1944;49:22–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Michel BA. et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1122–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van Der Geest KSM, Sandovici M, Brouwer E, Mackie SL.. Diagnostic accuracy of symptoms. Physical signs, and laboratory tests for giant cell arteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:1295–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hočevar A, Ješe R, Tomšič M, Rotar Z.. Risk factors for severe cranial ischaemic complications in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2020;59:2953–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hellmich B, Agueda A, Monti S. et al. 2018 Update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of large vessel vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maz M, Chung SA, Abril A. et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation guideline for the management of giant cell arteritis and Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73:1349–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horton BT. Headache and intermittent claudication of the jaw in temporal arteritis. Headache J. Head Face Pain 1962;2:29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robson JC, Almeida C, Dawson J. et al. Patient perceptions of health-related quality of life in giant cell arteritis: international development of a disease-specific patient-reported outcome measure. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2021;60:4671–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kraemer M, Metz A, Herold M, Venker C, Berlit P.. Reduction in jaw opening: a neglected symptom of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol Int 2011;31:1521–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nir-Paz R, Gross A, Chajek-Shaul T.. Reduction of jaw opening (trismus) in giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:832–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coskun Akar G, Govsa F, Ozgur Z.. Examination of the heads of the lateral pterygoid muscle on the temporomandibular joint. J Craniofac Surg 2009;20:219–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilkie G, Al-Ani Z.. Temporomandibular joint anatomy, function and clinical relevance. Br Dent J 2022;233:539–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA. et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res 2015;42:533–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request, please contact Dr Joanna Robson.