Abstract

Background

The real-world clinical effectiveness of sotrovimab in preventing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–related hospitalization or mortality among high-risk patients diagnosed with COVID-19, particularly after the emergence of the Omicron variant, needs further research.

Method

Using data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system, we adopted a target trial emulation design in our study. Veterans aged ≥18 years, diagnosed with COVID-19 between December 1, 2021, and April 4, 2022, were included. Patients treated with sotrovimab (n = 2816) as part of routine clinical care were compared with all eligible but untreated patients (n = 11,250). Cox proportional hazards modeling estimated the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for the association between receipt of sotrovimab and outcomes.

Results

Most (90%) sotrovimab recipients were ≥50 years old, and 64% had ≥2 mRNA vaccine doses or ≥1 dose of Ad26.COV2. During the period that BA.1 was dominant, compared with patients not treated, sotrovimab-treated patients had a 70% lower risk of hospitalization or mortality within 30 days (HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.23–0.40). During BA.2 dominance, sotrovimab-treated patients had a 71% (HR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.08–0.98) lower risk of 30-day COVID-19-related hospitalization, emergency room visits, or urgent care visits (defined as severe COVID-19) compared with patients not treated.

Conclusions

Using national real-world data from high-risk and predominantly vaccinated veterans, administration of sotrovimab, compared with contemporary standard treatment regimens, was associated with reduced risk of 30-day COVID-19-related hospitalization or all-cause mortality during the Omicron BA.1 period.

Keywords: COVID-19, monoclonal antibodies, prevention, real-world data, SARS-CoV-2

Sotrovimab, a recombinant human monoclonal antibody targeted against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), received Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) on May 26, 2021, for treatment of mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19 [1]. Among sotrovimab EUA–eligible outpatients, a single 500-mg intravenous dose, compared with placebo, was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of a composite end point of 29-day all-cause hospitalization or death (COMET-ICE) [2]: 3 patients (1%) in the sotrovimab group, vs 21 patients (7%) in the placebo group, with a relative risk reduction of 85%. These findings supported sotrovimab as a treatment option for high-risk outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19 caused by the SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating through March 2021: Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Lambda [3]. SARS-CoV-2 variant tracking data from the US Centers for Disease Control and prevention (CDC) showed the rise of the Delta variants during 2021, followed by Omicron variant dominance (BA.1, BA.2 and BA.2.12.1, BA 4/5) in 2022. On March 25, 2022, due to concerns for resistance (Supplementary Table 1) [4] of the increasingly prevalent SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 subvariant, sotrovimab was removed as a therapeutic option by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in any US region with a prevalence >50%. Sotrovimab de-authorization was extended nationwide on April 5, 2022.

The quick withdrawal of the sotrovimab EUA was due to lower neutralizing ability in vitro for Omicron BA.2 compared with the BA.1 sublineage. With other treatments such as nirmatrelvir/ritonavir available (starting in January 2022 at the Department of Veterans Affairs [VA]) and effective, the sudden withdrawal by the FDA was prudent in terms of patient care, but it rendered evaluation of sotrovimab using real-world data in the United States difficult and scattered. Some regional retrospective analysis was done; however, examination of national real-world evidence during the Delta- and Omicron-predominant periods is needed to inform whether monoclonal antibody therapies such as sotrovimab could still provide an important COVID-19 treatment option [5, 6]. Our objective was to assess the effectiveness of sotrovimab related to hospitalization or all-cause mortality within 30 days of treatment during the period of Omicron BA.1 dominance using electronic health record (EHR) data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the largest integrated health care system in the United States.

METHODS

Study Setting

We analyzed EHR data using the VA Corporate Data Warehouse—which contains patient-level information on clinical encounters for nearly 9 million veterans served in the VA's 171 medical centers and 1113 outpatient clinics—including procedures, prescriptions, vaccinations, laboratory results, health care utilization, and vital status [7, 8]. We identified VA use of sotrovimab through the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management EUA prescription dashboard, which captures and links records of recipients, date, and dosage. Sotrovimab was available for administration at the VA from December 2021 to April 2022; first dose administered on December 1, 2021, last dose on April 4, 2022.

Before data collection for deidentified analysis, this study was approved by the institutional review board of the VA Medical Center in White River Junction, Vermont.

Study Design

We employed a target trial emulation (TTE) design [9]. The TTE approach incorporates clinical trial elements into observational studies by using clinical trial terminologies (eg, eligibility) instead of those from observational studies (eg, inclusion/exclusion criteria). To mimic randomization, TTE matches eligible persons on individual factors—most importantly, on treatment date.

To explore the possibility of residual confounding (eg, by unmeasured health care–seeking behavior or underlying conditions), we used clinical visits for urinary tract infection (UTI) as a negative control [10] for falsification testing. We chose UTI as a negative control because while no causal link exists between sotrovimab and UTI, similar biases could affect sotrovimab's association with both UTIs and COVID-19 outcomes [11]. A UTI event is defined by either a primary diagnosis of UTI at an outpatient visit or a discharge diagnosis after a hospitalization.

Eligibility Criteria

We included veterans who were aged ≥18 years, who had either been diagnosed with COVID-19 (detected via antigen or PCR testing) or received sotrovimab or both, from December 1, 2021, to April 4, 2022, and continuously received Veterans Health Administration benefits for at least 2 years before enrollment (using the nomenclatures of clinical trials) to improve the likelihood that their medical history was complete. To evaluate the effect of sotrovimab vs no treatment, we included positive laboratory tests and documented home testing of veterans with SARS-CoV-2 infection, which made patients eligible for sotrovimab. Strictly following sotrovimab EUA eligibility criteria, we identified patients not requiring hospitalization or new supplemental oxygen, yet at high risk of disease progression, using diagnosis codes during the 2 years before their SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis date.

Eligible patients were further restricted to those who met at least 1 criterion for sotrovimab use under the EUA [12]. Then they were grouped according to whether they received (hereafter, “treated”) or did not receive sotrovimab or any early antiviral treatment (oral antivirals or monoclonal antibodies; hereafter, “not treated”) during the same week they tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. For every treated individual, we identified eligible study participants who were alive and infected with SARS-CoV-2 on the same day as the treated individual, but who were untreated during the 7 days after their infection.

Stratifying Criteria

To ensure balance between the treated and not treated, eligible patients were randomly assigned to a group within strata defined according to calendar date (1-day span), vaccination status (unvaccinated, vaccinated with a primary series [2 mRNA or a single Janssen], or primary series plus booster), and US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) region (due to the FDA de-authorizing sotrovimab dissemination by HHS region following the rise of the Omicron BA.2 variant) (Supplementary Table 1). The specific underlying conditions stratified were chronic kidney disease or renal disease, immunosuppressive disease or immunosuppressive treatment, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (the most prevalent chronic lung disease in the VA) or asthma, and cardiovascular disease or hypertension. The index date was the first of positive SARS-CoV-2 lab test date or documented home test. If either was missing, for treated individuals, the index date was their diagnosis date for COVID-19 (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10], code U07.1).

We included baseline characteristics (eg, demographics, significant comorbidities, and health care utilization) documented within 2 years before the index date. We included additional variables (Table 1) such as age categories (18–49, 50–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80+ years) and sex (male or female) as covariates in our survival analyses. Covariates were measured before the initiation of sotrovimab to avoid adjustment for potential mediators. Rather than removing subjects with missing data, indicator variables were generated to capture missing or unknown values for any matching criteria to retain patients in the study. To assess the robustness of matching, we calculated standardized mean difference, and a difference of ≥10 was used to identify imbalance between treated and untreated matched comparators.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Unmatched | Matched | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | Sotrovimab | Untreated | Sotrovimab | |||

| (n = 145 346), No. (%) | Recipients (n = 2868), No. (%) | SMD | (n = 11 250), No. (%) | Recipients (n = 2816), No. (%) | SMD | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–49 y | 42 520 (29) | 288 (10) | −49.8 | 1416 (13) | 278 (10) | −8.6 |

| 50–69 y | 57 794 (40) | 1099 (38) | −3.0 | 4747 (42) | 1074 (38) | −8.3 |

| 70–74 y | 21 204 (15) | 711 (25) | 25.9 | 2299 (20) | 705 (25) | 9.7 |

| 75–79 y | 12 942 (9) | 424 (15) | 18.3 | 1489 (13) | 418 (15) | 6.1 |

| ≥80 y | 10 886 (7) | 346 (12) | 15.4 | 1299 (12) | 341 (12) | 1.7 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 18 838 (13) | 253 (9) | −13.3 | 917 (8) | 247 (9) | 2.2 |

| Male | 126 508 (87) | 2615 (91) | 13.3 | 10 333 (92) | 2569 (91) | −2.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Black: non-Hispanic Black | 32 211 (22) | 468 (16) | −14.9 | 2471 (22) | 459 (16) | −14.4 |

| Hispanic any race | 13 225 (9) | 181 (6) | −10.5 | 838 (7) | 179 (6) | −4.3 |

| Other | 12 043 (8) | 197 (7) | −5.4 | 827 (7) | 190 (7) | −2.4 |

| White: non-Hispanic White | 87 867 (60) | 2022 (71) | 21.3 | 7114 (63) | 1988 (71) | 15.7 |

| No. of vaccinations | ||||||

| 0 doses of vaccine | 60 920 (42) | 1037 (36) | −11.8 | 3911 (35) | 1015 (36) | 2.7 |

| 2 doses of vaccinea | 84 426 (58) | 1831 (64) | 11.8 | 7339 (65) | 1801 (64) | −2.7 |

| 3 doses of vaccine | 37 116 (26) | 967 (34) | 18.0 | 3820 (34) | 957 (34) | 0.1 |

| Other | ||||||

| Nursing home use | 4369 (3) | 104 (4) | 3.5 | 592 (5) | 103 (4) | −7.8 |

| Rural | 38 241 (26) | 993 (35) | 18.1 | 3215 (29) | 977 (35) | 13.2 |

| Priority 1–4 | 63 419 (44) | 1262 (44) | 0.7 | 4879 (43) | 1241 (44) | 1.4 |

| BMI category | ||||||

| Missing | 9822 (7) | 107 (4) | −13.6 | 444 (4) | 101 (4) | −1.9 |

| Normal | 32 100 (22) | 675 (24) | 3.5 | 2682 (24) | 666 (24) | −0.4 |

| Overweight/obese | 103 424 (71) | 2086 (73) | 3.5 | 8124 (72) | 2049 (73) | 1.2 |

| Health and Human Services region | ||||||

| Other | 1998 (1) | 27 (1) | −4.1 | 129 (1) | 25 (1) | −2.6 |

| Regions 1, 2 | 14 873 (10) | 282 (10) | −1.3 | 1092 (10) | 281 (10) | 0.9 |

| Regions 3, 4, 6, 7, 8 | 84 600 (58) | 1619 (56) | −3.5 | 6376 (57) | 1595 (57) | −0.1 |

| Regions 5, 9, 10 | 43 875 (30) | 940 (33) | 5.6 | 3653 (32) | 915 (32) | 0.0 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||||

| Mean (median) | 1.1 (0.0) | 2.2 (2.0) | … | 2.2 (2.0) | 2.3 (2.0) | … |

| CAN score | ||||||

| CAN mortality 1 y, mean | 0.04 | 0.07 | … | 0.07 | 0.07 | … |

| Underlying conditions | ||||||

| Any immunocompromising condition | 23 319 (16) | 1002 (35) | 44.4 | 3935 (35) | 999 (35) | 1.0 |

| Immunosuppressive disease or immunosuppressive treatment | 39 743 (27) | 1399 (49) | 45.3 | 5536 (49) | 1386 (49) | 0.0 |

| Asthma | 6256 (4) | 186 (6) | 9.7 | 706 (6) | 184 (7) | 1.1 |

| Cancer | 8674 (6) | 389 (14) | 25.8 | 1461 (13) | 389 (14) | 2.4 |

| Cancer, metastatic | 913 (1) | 49 (2) | 10.1 | 156 (1) | 49 (2) | 2.8 |

| Cardiovascular disease or hypertension | 67 616 (47) | 1962 (68) | 45.4 | 7827 (70) | 1957 (69) | −0.2 |

| Congestive heart failure | 9079 (6) | 354 (12) | 21.1 | 1406 (12) | 353 (13) | 0.1 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11 409 (8) | 581 (20) | 36.3 | 2355 (21) | 579 (21) | −0.9 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 19 754 (14) | 648 (23) | 23.5 | 2559 (23) | 641 (23) | 0.0 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 6323 (4) | 196 (7) | 10.8 | 828 (7) | 195 (7) | −1.7 |

| Dementia | 3242 (2) | 92 (3) | 6.0 | 437 (4) | 91 (3) | −3.5 |

| Diabetes mellitus w/ complications | 14 406 (10) | 598 (21) | 30.7 | 2063 (18) | 596 (21) | 7.1 |

| Diabetes mellitus w/o complications | 21 500 (15) | 590 (21) | 15.2 | 2682 (24) | 587 (21) | −7.2 |

| HIV | 1000 (1) | 35 (1) | 5.5 | 174 (2) | 33 (1) | −3.2 |

| Hypertension | 65 272 (45) | 1881 (66) | 42.5 | 7587 (67) | 1876 (67) | −1.7 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 1115 (1) | 68 (2) | 12.9 | 221 (2) | 68 (2) | 3.1 |

| Liver disease mild | 6279 (4) | 182 (6) | 9.0 | 772 (7) | 182 (6) | −1.6 |

| Liver disease severe | 595 (0) | 19 (1) | 3.5 | 72 (1) | 18 (1) | 0.0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 3288 (2) | 135 (5) | 13.4 | 488 (4) | 134 (5) | 2.0 |

| Obesity | 24 018 (17) | 603 (21) | 11.5 | 2487 (22) | 601 (21) | −1.9 |

| Para/hemiplegia | 1014 (1) | 26 (1) | 2.3 | 124 (1) | 26 (1) | −1.8 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 777 (1) | 35 (1) | 7.4 | 105 (1) | 35 (1) | 3.0 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 7721 (5) | 277 (10) | 16.6 | 1136 (10) | 275 (10) | −1.1 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2167 (1) | 130 (5) | 17.9 | 331 (3) | 130 (5) | 8.8 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CAN, Care Assessment Needs; SMD, standardized mean difference.

aTwo doses of mRNA vaccine or 1 dose of Janssen vaccine.

We used the VA-assigned priority group for health care, which is determined by aggregating medical condition, service experience, and income, to serve as a surrogate measure for socioeconomic status [13]. Information regarding comorbidities was extracted from diagnostic codes recorded in VA electronic data for health care encounters; significant comorbidities were defined according to an adaptation of the Deyo-Charlson comorbidity index (DCCI) [14].

We divided the study period into 3 predominant variant periods: Delta dominance (17 days, December 1–17, 2021), BA.1 dominance (from December 18, 2021, to March 15, 2022), and BA.2 dominance (20 days, March 16 to April 4, 2022) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Our main analysis focuses on the BA.1 period, and the primary outcome was the composite of (1) COVID-19 hospitalization, defined as having both an admission and discharge diagnosis for COVID-19 from a hospital within 30 days of the index (eg, positive SARS-CoV-2 test) date, and (2) all-cause mortality, defined as having a date of death during follow-up, also within 30 days of the index date. Time to event was the time from the index date to the first occurrence of the outcome of interest (30-day hospitalization or mortality). We studied the effectiveness of sotrovimab against the composite outcome stratified by age and high-risk groups—65 or older and patients who are immunocompromised or have renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or cardiovascular disease.

Statistical Analysis

Like intention-to-treat analysis of clinical trial data, incident outcome rates were estimated via the Kaplan-Meier estimator for the maximum 30-day interval post-treatment. We used a Cox proportional hazards regression model to compare patients treated with sotrovimab with those not treated during each of the 3 predominant variant periods as defined above. Patients’ outcomes were assessed within a 30-day period after the index date, censoring on the earliest of: May 4, 2022 (to allow a 30-day postindex observation period for the last sotrovimab administered in the VA), death, or 30 days postindex.

Secondary Analyses

The FDA began to de-authorize sotrovimab (Supplementary Table 1) shortly after BA.2 became the predominant SARS-CoV-2 variant in the United States. Consequently, we observed few sotrovimab administrations and fewer outcomes from March 25, 2022, through April 4, 2022. Similarly, we used a short Delta period (17 days) starting when sotrovimab became available at the VA and ending when Omicron BA.1 became predominant, resulting in a small number of primary end points. As these periods were both too short to garner enough hospitalizations to power statistical analysis, we included COVID-19-related emergency department (ED) or urgent care (UC) visits where COVID-19 was the primary diagnosis during both admission and discharge as a surrogate for severe COVID-19 for our effectiveness estimate of sotrovimab against either the Delta or the Omicron BA.2 SARS-CoV-2 variant. The time to event was from the index date to the first occurrence of the outcome of interest (30-day hospitalization or ED visits or UC visits). Nevertheless, we analyzed the rate of composite outcome during the short Delta and BA.2 periods so the results from all 3 periods can be compared.

Analyses were performed with SAS software, version 8.2 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Study Population

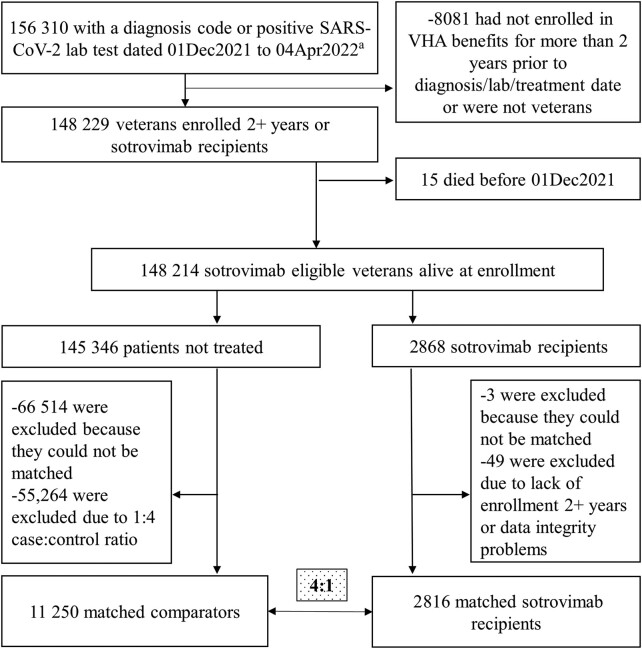

We identified 2868 sotrovimab recipients and 145 346 eligible patients who had no record of receiving any treatment directed at COVID-19, including sotrovimab (Figure 1). Representative of the VA population, we found that among sotrovimab recipients, most were non-Hispanic White (71%) males (91%) over the age of 50 (90%) living in urban areas [15] (65%), most (64%) of whom had received 2 doses of mRNA vaccines or 1 dose of Ad26.COV2 (Janssen). Common comorbidities among treated individuals included hypertension (1876, 67%) and any immunocompromising condition or immunosuppressive treatment (1386, 49%). Applying the additional stratifying criteria listed above, 2816 treated and 11 250 untreated patients (ie, matched comparators, up to 4) were balanced across baseline characteristics (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Attrition. aIncludes those with a sotrovimab prescription and presumed positive lab test (47 patients without a visible lab or dx). Exact matching criteria: had booster at index; control was alive as of the case’s index date; sotrovimab prescription date and control’s diagnosis/positive lab date were within 1 week of each other; HHS category: HHS regions 1 or 2, HHS regions 5, 9, or 10, HHS regions 3, 4, 6, 7, 8; comorbid condition category: kidney (CKD, renal), lung (COPD, asthma), immunosuppressive prescription or diagnosis, cardiac diagnosis (CAD or HTN). Controls had 1 of the following conditions: CKD, renal disease, diabetes, CAD, MI, CHF, dyslipidemia, ILD, sickle cell disease, immunocompromising condition, COPD, asthma, HTN, CVD, hematological cancers. Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HHS, US Department of Health and Human Services; HTN, hypertension; ILD, interstitial lung disease; MI, myocardial infarction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

Main Analysis/BA.1 Period

Compared with untreated matched comparators, sotrovimab recipients had a 66% lower risk of COVID-19-related 30-day hospitalization (HR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.25–0.46) and a 77% lower risk of 30-day all-cause mortality (HR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.14–0.38) during the BA.1-predominant period (Table 2). When these 2 outcomes—hospitalization and mortality—were combined, sotrovimab recipients had a lower incidence of the composite outcome (92/2557, 3.6%) vs untreated matched comparators (735/10 297, 7.1%) and a 70% lower risk (HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.23–0.40). Compared with untreated matched comparators, sotrovimab was associated with a similar risk reduction in the composite outcome among those 65 years of age or older (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.24–0.45) as well as among those immunocompromised or with renal disease (HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20–0.45). By vaccination status (unvaccinated, vaccinated with a primary series or primary series plus booster), sotrovimab-treated patients had a 58% (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.29–0.59), 64% (HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.24–0.54), and 72% (HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.17–0.47) lower risk of 30-day hospitalization or mortality, respectively.

Table 2.

Relative Effectiveness of Sotrovimab vs Untreated Comparators Using Adjusted Analysis

| Untreated | Sotrovimab Recipients (n = 2816) |

Exact Matched Multivariable Survival Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 11 250) | |||

| Total Events (%) | Total Events (%) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Main analysis (BA.1 predominant) | |||

| Composite outcome (30-d COVID-19 hospitalization or all-cause mortality) | |||

| n = 10 297 | n = 2557 | ||

| Overall cohort | 735 (7.1) | 92 (3.6) | 0.30 (0.23–0.40) |

| 65 or older | 571 (9.5) | 82 (4.7) | 0.33 (0.24–0.45) |

| Immunocompromised or have renal disease | 367 (11.4) | 50 (5.8) | 0.30 (0.20–0.45) |

| Cardiovascular | 636 (8.6) | 81 (4.4) | 0.32 (0.24–0.43) |

| COPD | 237 (9.8) | 26 (4.3) | 0.29 (0.18–0.47) |

| Individual outcome (BA.1 dominance) | |||

| COVID-19-related hospitalization | 479 (4.7) | 77 (3.0) | 0.34 (0.25–0.46) |

| All-cause mortality | 288 (2.8) | 21 (0.8) | 0.23 (0.14–0.38) |

| Urinary tract infectiona | 473 (4.6) | 114 (4.5) | 0.94 (0.76–1.15) |

| Secondary analysis—BA.2 predominant (starting March 16, 2022) | |||

| n = 286 | n = 74 | ||

| Composite outcome | 10 (3.5) | 1b (1.4) | 0.38 (0.01–2.74) |

| COVID-19-related hospitalization, ED, or UC | 31 (10.8) | <10b (4.0) | 0.29 (0.08–0.98) |

| Secondary analysis—Delta predominant (before December 18, 2021) | |||

| n = 667 | n = 185 | … | |

| Composite outcome | 52 (7.8) | <10b (4.9) | 0.54 (0.26–1.14) |

| COVID-19-related hospitalization, ED, or UC | 98 (14.7) | 12 (6.5) | 0.46 (0.22–0.95) |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ED, emergency department; UC, urgent care; VA, Department of Veterans Affairs.

aFalsification analysis.

bThe VA has a specific policy that forbids directly publishing sample size between 1 and 10 due to risk of inadvertent identification: https://resdac.org/articles/cms-cell-size-suppression-policy.

Secondary Analyses/Delta and BA.2 Periods

Compared with untreated matched comparators, sotrovimab recipients during the Delta dominance period (December 1–17, 2021) had a 54% lower risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization, emergency department visits, or UC visits (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.22–0.95). Additionally, we examined the impact of sotrovimab during the period of BA.2 and BA.2.12.1 dominance, based on CDC variant tracking. From March 16 through April 4, 2022, 74 patients received sotrovimab. Compared with patients not treated, sotrovimab recipients had a 71% lower risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization, emergency department visits, or UC visits (HR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.08–0.98) during the period of BA.2 and BA.2.12.1 dominance. Lastly, despite small numbers captured during the Delta- and BA.2-dominated periods contributing to wider CIs, treated patients had lower odds for the composite outcome of 30-day hospitalization or all-cause mortality vs matched untreated patients; the BA.2 period had a 62% reduction (0.38; 95% CI, 0.01–2.74), and the Delta period had a 46% reduction (0.54; 95% CI, 0.26–1.14) (Table 2).

Falsification Analysis

Six hundred ninety-seven UTI visits were observed during the follow-up period. The matched analysis demonstrated a similar effectiveness of sotrovimab vs untreated comparator against UTI (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.76–1.15) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Administration of sotrovimab during the BA.1-predominant period was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of COVID-19 hospitalizations and all-cause mortality compared with untreated matched comparators in a study design emulating a clinical trial. Findings were consistent among immunocompromised individuals, patients with renal diseases, and those who were 65 years or older. Studying a different outcome measure, we did not see unequivocal evidence of reduced effectiveness during the rise of the SARS-CoV-2 BA.2 variant in the United States, though the analysis was limited by sample size due to sotrovimab no longer being authorized for use in the United States after BA.2 was predominant.

Aggarwal and colleagues examined sotrovimab effectiveness among high-risk outpatients diagnosed with COVID-19 in Colorado when Delta was predominant and found 63% lower odds of 28-day all-cause hospitalization and 89% lower odds of 28-day all-cause mortality [5]. They also assessed sotrovimab effectiveness during the Omicron BA.1 and BA.1.1 waves but found nonsignificantly lower odds of 28-day all-cause hospitalization or mortality, “28-day hospitalization (2.5% vs 3.2%; adjusted OR 0.82, 95% CI .55, 1.19) or mortality (0.1% vs 0.2%; adjusted OR 0.62, 95% CI .07, 2.78)” [6], among patients with COVID-19 at high risk of disease progression. Finally, a large representative US sample of high-risk COVID-19 patients diagnosed between September 1, 2021, and April 30, 2022, in the FAIR Health National Private Insurance Claims database found that patients receiving sotrovimab had a 55% lower risk of 30-day hospitalization or mortality (RR, 0.45, 95% CI, 0.41–0.49) and an 85% lower risk of 30-day mortality (RR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.08–0.29) [16]. Like Aggarwal et al., Cheng et al. found reduced but nonsignificant sotrovimab effectiveness during BA.2 predominance (RR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.04–2.38) in April 2022, with 68 doses of sotrovimab dispensed in an eligible population >117 000.

On April 5, 2022, the FDA withdrew approval of sotrovimab based on in vitro neutralization results—a decrease in microneutralization titer EC90 of 25–48-fold relative to ancestral SARS-CoV-2—and pharmacokinetic modeling suggesting that the authorized dose was unlikely to be effective against BA.2 [4]. Our purpose for conducting this study was to provide background real-world data around the time of that decision, which were not available to the FDA, as other researchers have done. Piccicacco and colleagues found that a sample of 88 patients “receiving sotrovimab were also less likely to be hospitalized or visit the ED (8% vs 23.3%; OR = 0.28, 95% CI, .11–.71)” [17]. We found almost the same relative risk at 0.29 (95% CI, 0.08–0.98) for COVID-19-related hospitalization, ED visits, or UC visits, although we had a smaller sample size (sotrovimab n = 74), and thus a wider confidence interval. Zheng and colleagues studied sotrovimab effectiveness among 3331 sotrovimab recipients with similar demographics and covering the BA.2-predominant period in the United Kingdom and found sotrovimab to be effective throughout BA.1, BA.2, and BA.4/5 predominance [18]. Martin-Blondel and colleagues, based on data from their prospective real-life cohort study that included mostly severely immunocompromised patients, suggested “the dose administered of sotrovimab might have potentially overcome its decreased neutralizing activity on the BA.2 sublineage.” Furthermore, they reasoned that the “preserved ability of sotrovimab to recruit and engage Fcγ receptor–bearing cells and complement system activator C1q may participate through Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity” and thus maintain its treatment in vivo [19].

In the case of sotrovimab, it is difficult to say whether combined evidence from our study and others using real-world clinical effectiveness data would sufficiently support its continued use against circulating Omicron variants and for how long. The ongoing evolution of SARS-CoV-2 variants and continued global transmission have resulted in a situation where new variants can replace one another within weeks. Regulatory agencies face a challenging environment as clinical data research takes time, while in vitro results might not be applicable in the clinical setting. Examination of real-world patient data could help to avoid scenarios wherein effective monoclonals are available but not offered to clinically vulnerable patients. Several authors from this study have suggested ways to remedy this situation [20].

Our study has several notable strengths. We analyzed 1669 patient-years of observation, making our study one of the largest conducted using electronic medical records to assess sotrovimab effectiveness while it was being utilized to combat a concurrent surge during the pandemic. The large sample allowed us to adjust for more potential confounding variables. Previous studies have shown that EHR data are more likely than insurance claims data to be complete in capturing medical conditions and have a lower risk of up-coding [21, 22]. Nevertheless, conventional analytical strategies like stratification, matching (with or without propensity score), and multivariate regression analysis cannot adequately adjust for unmeasured confounders [23, 24, 25]. By mimicking the randomization in a clinical trial in assigning treatments, and because >90% of the time the VA provided sotrovimab to patients within 1–2 days of their infection, matching those treated and untreated on the day of their infection ensured similar lengths of follow-up between the recipients and those patients not treated, thus reducing immortal bias.

Limitations

First, VA data include only health care encounters occurring in VA medical centers, potentially missing hospitalizations occurring outside the VA (ascertainment bias); assuming missed events were as likely among those treated as among untreated matched comparators, this nondifferential misclassification would have biased our results toward the null. Second, the VA has a unique population (mostly male, older), and our results may not be generalizable to a larger population of patients not treated at the VA (selection bias) [26]. Third, ICD-10 codes from claims data have been shown to inadequately capture comorbidity and functional status [27]. Fourth, we did not have sequencing data for this study to determine the variants of the SARS-CoV-2 infections included in this analysis. Fifth, home testing might have been a better measure of health care–seeking behavior than UTI; unfortunately, documentation was available for only a portion of the tests to accurately determine which tests were home antigen tests. The lack of association between sotrovimab and UTI, nevertheless, seemed to align with our assumption that the protective effects of sotrovimab administration were less likely due to bias or other major methodological flaws. Sixth, we focused on the short-term (within 1 month) effectiveness of sotrovimab to enable comparison with results from COMET-ICE and other studies. Long-term impact, considering our improved knowledge and understanding of COVID-19 recurrence and persistence, deserves more attention. We matched treated and untreated matched comparator patients in regions where sotrovimab was given to ensure comparability between groups for this study, but further research on drivers of prescribing differences is needed as to why patients may not realize the potential benefit and eligibility for this and other COVID-19 treatments [28].

Finally, the 2 periods studied for predominance during Delta (12/1–17/21) and Omicron BA.2 (3/16–4/4/22) were brief, with smaller numbers of treated and untreated patients, as shown in Table 2, highlighting the absence of viral sequence data, which would be even more helpful for the BA.2 period. Despite this brevity, analysis using the composite outcome showed the same protective effect associated with the usage of sotrovimab during the BA.1 period. To improve statistical power, we used a different outcome measure than the one for the BA.1 period, but we believe it serves well as a surrogate for disease progression and provided a reasonable comparison between a period when the efficacy of sotrovimab was certain and a period when it was in doubt. Although the data for the BA.1 period can stand alone, the inclusion of late Delta and BA.2 in the present study contributes to a better understanding of the effectiveness of sotrovimab during its EUA.

CONCLUSIONS

Using national data from veterans, we found that administration of sotrovimab was associated with lower risks of 30-day COVID-19-related hospitalization and all-cause mortality, compared with untreated matched comparators, during the period of Omicron BA.1 dominance. Our real-world results also suggest that sotrovimab administration may have protected vulnerable patients from severe COVID-19 during BA.2 dominance. Ongoing real-world data remain critical to understand the clinical effectiveness of sotrovimab and other monoclonal antibody therapies. These results continue to indicate that monoclonal antibody therapy is an effective strategy for treatment of COVID-19 for certain patient populations with susceptible dominant SARS-CoV-2 strains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Author contributions. Conception and design: Y. Young-Xu, C. Korves, G. Zwain, M. Drysdale, S. Satram, C. Reyes, M.M. Cheng, R.A. Bonomo, L. Epstein, V.C. Marconi, A.A. Ginde. Analysis and interpretation of the data: Y. Young-Xu, C. Korves, G. Zwain, M. Drysdale, S. Satram, C. Reyes, M.M. Cheng, R.A. Bonomo, L. Epstein, V.C. Marconi, A.A. Ginde. Drafting of the article: Y. Young-Xu, C. Korves, G. Zwain. Critical revision for important intellectual content: Y. Young-Xu, C. Korves, G. Zwain, M. Drysdale, S. Satram, C. Reyes, M.M. Cheng, R.A. Bonomo, L. Epstein, V.C. Marconi, A.A. Ginde. Final approval of the article: Y. Young-Xu, C. Korves, G. Zwain, M. Drysdale, S. Satram, C. Reyes, M.M. Cheng, R.A. Bonomo, L. Epstein, V.C. Marconi, A.A. Ginde. Provision of study materials or patients: Y. Young-Xu. Statistical expertise: Y. Young-Xu, C. Korves. Administrative, technical, or logistic support: Y. Young-Xu. Collection and assembly of data: Y. Young-Xu, G. Zwain.

Disclaimer. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government. Medical writing assistance was provided by Tara Krause, BA, of the Clinical Epidemiology Program at the White River Junction VA Medical Center, Vermont, USA.

Patient consent. Patient data were collected anonymously from deidentified medical records. The institutional review board of the VA Medical Center in White River Junction, Vermont, USA, determined that individual informed consent was not required for this study (number 1473972).

Data sharing. Requests for access to the deidentified study data can be via e-mail to yinong.young-xu@va.gov. No supporting documents will be made available. The data will be made available to qualified scientific researchers for specific purposes outlined in a proposal after the researcher enters into a standard data sharing agreement and the proposal is approved. Researchers must commit to transparency in publication.

Financial support. This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development, the VA Office of Rural Health, Clinical Epidemiology Program at the White River Junction VA Medical Center, by Vir Biotechnology in collaboration with GSK, by resources and the use of facilities at the White River Junction VA Medical Center and VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure, and with data from the VA COVID-19 Shared Data Resource.

Contributor Information

Yinong Young-Xu, US Department of Veterans Affairs, PBM, Center for Medication Safety, Hines, Illinois, USA; Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA.

Caroline Korves, US Department of Veterans Affairs, PBM, Center for Medication Safety, Hines, Illinois, USA; White River Junction Veterans Affairs Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont.

Gabrielle Zwain, US Department of Veterans Affairs, PBM, Center for Medication Safety, Hines, Illinois, USA; White River Junction Veterans Affairs Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont.

Sacha Satram, Vir Biotechnology, San Francisco, California, USA.

Myriam Drysdale, GSK, Brentford, Middlesex, UK.

Carolina Reyes, Vir Biotechnology, San Francisco, California, USA.

Mindy M Cheng, Vir Biotechnology, San Francisco, California, USA.

Robert A Bonomo, US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA SHIELD, Veterans Affairs Northeast Ohio Healthcare System, Cleveland, Ohio, USA; Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, USA.

Lauren Epstein, Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Decatur, Georgia, USA; Division of Infectious Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Vincent C Marconi, Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Decatur, Georgia, USA; Division of Infectious Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA; Department of Global Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Adit A Ginde, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado, USA.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. US Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes additional monoclonal antibody for treatment of COVID-19. Updated May 26, 2021. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-additional-monoclonal-antibody-treatment-covid-19. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- 2. Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al. Early treatment for COVID-19 with SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody sotrovimab. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:1941–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al. Effect of sotrovimab on hospitalization or death among high-risk patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2022; 327:1236–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Food and Drug Administration . FDA updates sotrovimab Emergency Use Authorization. Updated April 5, 2022. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-updates-sotrovimab-emergency-use-authorization. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- 5. Aggarwal NR, Beaty LE, Bennett TD, et al. Real world evidence of the neutralizing monoclonal antibody sotrovimab for preventing hospitalization and mortality in COVID-19 outpatients. J Infect Dis 2022; 226:2129–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aggarwal NR, Beaty LE, Bennett TD, et al. Change in effectiveness of sotrovimab for preventing hospitalization and mortality for at-risk COVID-19 outpatients during an Omicron BA.1 and BA.1.1-predominant phase. Int J Infect Dis 2023; 128:310–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Health Services Research and Development, US Department of Veterans Affairs . Corporate Data Warehouse. Available at: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cdw.cfm. Accessed September 24, 2022.

- 8. De Groot K. Ascertaining veterans’ vital status: VA data source for mortality ascertainment and cause of death, Database & Methods Cyberseminar Series, VA Information Resource Center. January 2019. Available at: https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/3544-notes.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2022.

- 9. Hernán MA, Wang W, Leaf DE. Target trial emulation: a framework for causal inference from observational data. JAMA 2022; 328:2446–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pizer SD. Falsification testing of instrumental variables methods for comparative effectiveness research. Health Serv Res 2016; 51:790–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lipsitch M, Tchetgen Tchetgen E, Cohen T. Negative controls: a tool for detecting confounding and bias in observational studies. Epidemiology 2010; 21:383–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. US Food and Drug Administration . Fact sheet for healthcare providers Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of sotrovimab. Updated March 2022. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/149534/download. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- 13. Petersen LA, Byrne MM, Daw CN, et al. Relationship between clinical conditions and use of Veterans Affairs healthcare among Medicare-enrolled veterans. Health Serv Res 2010; 45:762–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45:613–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cromartie J. Rural Urban Commuting Codes, US Department of Agriculture. Updated August 17, 2020. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/. Accessed September 24, 2022.

- 16. Cheng MM, Reyes C, Satram S, et al. Real-world effectiveness of sotrovimab for the early treatment of COVID-19 during SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron waves in the USA. Infect Dis Ther 2023; 12:607–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Piccicacco N, Zeitler K, Ing A, et al. Real-world effectiveness of early remdesivir and sotrovimab in the highest-risk COVID-19 outpatients during the Omicron surge. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022; 77:2693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zheng B, Green ACA, Tazare J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of sotrovimab and molnupiravir for prevention of severe COVID-19 outcomes in patients in the community: observational cohort study with the OpenSAFELY platform. BMJ 2022; 379:e071932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martin-Blondel G, Marcelin A-G, Soulié C, et al. Sotrovimab to prevent severe COVID-19 in high-risk patients infected with Omicron BA.2. J Infect 2022; 85:e104–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Young-Xu Y, Davey V, Marconi VC, et al. Veterans Affairs big data science: a model for improved national pandemic response present and future. Fed Pract 2023; 40:S39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adler-Milstein J, Jha AK. No evidence found that hospitals are using new electronic health records to increase Medicare reimbursements. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014; 33:1271–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Devoe JE, Gold R, McIntire P, et al. Electronic health records vs Medicaid claims: completeness of diabetes preventive care data in community health centers. Ann Fam Med 2011; 9:351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Psaty BM, Koepsell TD, Lin D, et al. Assessment and control for confounding by indication in observational studies. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47:749–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, et al. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60:1487–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A 2001; 56:M146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rogers WH, Kazis LE. Comparing the health status of VA and non-VA ambulatory patients: the Veterans’ Health and Medical Outcomes studies. J Ambul Care Manage 2004; 27:249–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mazzali C, Duca P. Use of administrative data in healthcare research. Intern Emerg Med 2015; 10:517–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kotton CN. Belt and suspenders: vaccines and sotrovimab for prevention of COVID-19 in immunocompromised patients. Ann Intern Med 2022; 175:892–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.