Highlights

-

•

The Canadian DMV/1639 IBV detrimentally affects egg production in infected layers.

-

•

Combined Mass and Conn IB vaccine regimen protects DMV/1639-infected layers.

-

•

Combining autogenous and heterologous IB vaccines enhances DMV/1639 protection.

-

•

Humoral immune response against IBV could be important for tissue protection.

Keywords: Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), DMV/1639, Autogenous vaccine, Layer, Canada

Abstract

The emergence of the Canadian Delmarva (DMV)/1639 infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) type strains was associated with egg production disorders in Eastern Canadian layer operations. While developing vaccines for novel IBV variants is not typically a reasonable approach, the consideration of an autogenous vaccine becomes more appealing, particularly when the new variant presents significant economic challenges. The current study aimed to compare the efficacies of two vaccination programs that included heterologous live priming by Massachusetts (Mass) and Connecticut (Conn) type vaccines followed by either a commercial inactivated Mass type vaccine or a locally prepared autogenous inactivated DMV/1639 type vaccine against DMV/1639 IBV challenge. The protection parameters evaluated were egg production, viral shedding, dissemination of the virus in tissues, gross and microscopic lesions, and immunological responses. The challenge with the DMV/1639 caused severe consequences in the non-vaccinated laying hens including significant drop in egg production, production of low-quality eggs, serious damage to the reproductive organs, and yolk peritonitis. The two vaccination programs protected the layers from the poor egg-laying performance and the pathology. The vaccination program incorporating the autogenous inactivated DMV/1639 type vaccine was more effective in reducing vial loads in renal and reproductive tissues. This was associated with a higher virus neutralization titer compared to the group that received the commercial inactivated Mass type vaccine. Additionally, the autogenous vaccine boost led to a significant reduction in the viral shedding compared to the non-vaccinated laying hens. However, both vaccination programs induced significant level of protection considering all parameters examined. Overall, the findings from this study underscore the significance of IBV vaccination for protecting laying hens.

1. Introduction

Avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) belongs to the gammacoronavirus genus and is responsible for highly contagious infections in chickens, affecting all age groups. IBV consistently demonstrates the ability to disseminate systemically beyond the respiratory tract, leading to urogenital tract diseases. In laying chickens, the major concern lies in the impact on egg-laying performance. Adverse effects on the number and quality of eggs laid as well as long-lasting reproductive tract abnormalities are common consequences of IBV infections in layers and growing pullets (Jackwood et al., 2013; Muneer et al., 1986; Hassan et al., 2021). The global number of IBV variants, that belong to different serotypes or genotypes, is consistently expanding due to the high mutation rate of the virus (Bande et al., 2017; Valastro et al., 2016). This phenomenon imposes an additional burden on chicken farms, as they are required to regularly update their IBV vaccination programs to effectively tackle this ongoing challenge (Jordan, 2017).

IBV has one of the largest ribonucleic acid (RNA) genomes among viruses, which encodes four structural proteins (spike [S], envelope [E], membrane [M], and nucleocapsid [N]), along with a variable number of non-structural proteins. The replication mechanisms of IBV increase its susceptibility to mutation and recombination, primarily due to the limited proof-reading ability and the unique property of discontinuous transcription exhibited by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Jackwood et al., 2012). The primary factor contributing to the emergence of new variants of IBV is the genetic diversity found within the S gene. Traditionally, the identification of strains associated with infectious bronchitis (IB) outbreaks relied heavily on serotypic classification. Recently, Valastro et al. introduced a consistent phylogeny-based classification, which categorizes IBV strains into distinct genotypes and lineages based on the genetic distances observed within the S1 gene (Valastro et al., 2016). In general, viruses belonging to the same genetic type are often serologically related; however, the antigenicity of the virus depends on specific amino acid changes within the S1 protein (Cavanagh et al., 1992).

Vaccination is a common practice employed by poultry producers to control IB. Broilers commonly receive two live attenuated IB vaccinations through their production cycle, which are usually administered two weeks apart. On the other hand, multiple applications of live attenuated vaccines are used for priming layers and breeders before the administration of inactivated IB vaccines just prior to the onset of egg production. Inactivated IB vaccines are essential to provide long-lasting immunity during the laying period. The serotype-specific nature of the immunity induced by IB vaccines should be considered when designing a proper vaccination regimen (Muneer et al., 1987). However, the choice of a particular vaccine serotype is constrained by the number of licensed IB vaccines within a specific region. These limitations can be partially overcome by combining live attenuated IB vaccines of different serotypes, which has the potential to broaden the protection against heterologous IBV challenge (Cook et al., 1999; de Wit et al., 2013). This concept is defined as the “protectotype”, which involves typing the vaccine seed virus through vaccination challenge experiments (Cook et al., 1999).

The role of the inactivated IB vaccines in boosting the immunity in layer-type chickens to combat the adverse outcomes of IBV challenge has been previously discussed (Box et al., 1988; de Wit et al., 2019). While inactivated vaccines are considered safer to use in terms of virulence, transmissibility, and interactions with field infections compared to live vaccines, there remains a restricted selection of antigenic types available for inactivated vaccines. Commercial vaccines are specifically formulated to address significant and consistent challenges faced by the poultry industry (e.g., serotype Massachusetts (Mass) of IBV) (Cook et al., 2012). However, if the infectious agent was found to be antigenically distinct from the conventional strains found in licensed vaccines, an autogenous vaccine option could be considered (Smith, 2004). Unlike standard commercial vaccines that demand extensive testing and rigorous regulatory procedures, autogenous vaccines require more basic testing and a shorter legal process (Palomino-Tapia, 2023). Generally, autogenous vaccines are inactivated and include the isolates recovered from affected flocks. Therefore, autogenous vaccines are most appropriate for layer and breeder birds to elicit enough immunity to protect them throughout their extended production cycle and confer maternal immunity to their progeny during the initial days of life.

In the Canadian veterinary market, only IB vaccines belonging to the Mass and Connecticut (Conn) types (Genotype I-1 lineage) are available (Valastro et al., 2016; Government of Canada 2023). However, since 2015, a genetically distinct IBV strain of the Delmarva (DMV)/1639 type (Genotype I-17 lineage) has been prevalent in Canadian poultry operations (Hassan et al., 2019). This particular IBV strain has been linked to abnormal development of the oviduct and significant drops in egg production in layer flocks in Eastern Canada (Hassan et al., 2021; Hassan et al., 2022a). A comparison between the S1 gene sequence of the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain and the Mass and Conn type strains revealed a low level of similarity (77.2%) (Hassan et al., 2019). However, adding vaccines of different serotypes to the vaccination program was shown to broaden the protection against different IBV variants (de Wit et al., 2019; Hassan et al., 2022b; Habibi et al., 2017). Furthermore, the additional benefit of boosting with an inactivated IB vaccine, following live priming, for protection of laying chickens was clearly demonstrated (de Wit et al., 2019; de Wit et al., 2022; Ali et al., 2023). In the present study, laying hens were primed with live attenuated Mass and Conn vaccines and the efficacies of boosting the birds with either a commercial inactivated Mass type vaccine or a locally prepared autogenous inactivated DMV/1639 type vaccine were compared.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical approval

All procedures were conducted with the formal approval of the Health Science Animal Care Committee (HSACC) of the University of Calgary (Protocol number AC19-0113). Chickens and eggs were obtained from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) located in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

2.2. IB vaccines and challenge virus

One commercial bivalent live attenuated IB vaccine of Mass and Conn types (Bronchitis Vaccine, Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health, Athens, GA, USA) and one commercial inactivated vaccine containing Mass type of IBV, Lasota strain of Newcastle disease virus, and Salmonella enteritidis (Poulvac® SE-ND-IB, Zoetis Inc., Kalamazoo, MI, USA) were used in this study. The live attenuated vaccine was reconstituted in cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and one recommended dose was administered by eyedrop to each bird. The inactivated vaccine was given by intramuscular injection at the 0.3 ml dose advised by the manufacturer.

The challenge strain IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 (IBV DMV/1639 genotype) was isolated from a commercial layer flock with a history of a drop in egg production (Hassan et al., 2019). The virus propagation and titration was performed in 10-day-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) embryonated chicken eggs as previously described (Hassan et al., 2021). The infectious allantoic fluid of the fourth passage had a virus titer of 1 × 107 embryo infectious dose (EID50)/ml.

2.3. Preparation of an IBV DMV/1639 inactivated oil-emulsion vaccine

The allantoic fluid containing the challenge virus was inactivated using formalin (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) at a final concentration of 0.1% (v/v), which was added to the virus stock with a continuous stirring for 24 hours (h) at 37 °C. The effectiveness of the virus inactivation was verified by conducting three successive passages of inoculation using 10-day-old SPF embryonated chicken eggs. Water in oil (W/O) inactivated emulsion vaccine was prepared by a high shear mixing of the inactivated virus with Montanide™ ISA 71 R VG (Seppic, La Garenne-Colombes, Paris, France) at a ratio of 30:70 (v/v), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The adjuvant comprised mineral oil to replicate the composition of the commercial inactivated vaccine. The sterility of the prepared vaccine was tested by the inoculation of Trypticase soy broth, Trypticase soy agar, and Sabouraud's dextrose agar. Moreover, quality control measures were assessed as recommended by the oil-emulsion manufacturer. Each dose of the vaccine (0.5 ml) was adjusted to 1 × 106 EID50 (Erfanmanesh et al., 2020; Al-Ebshahy et al., 2019).

2.4. Experimental design

A total of 54 SPF White Leghorn pullets, at the age of 1-day-old, were assigned randomly into 3 groups of 18 pullets each. These groups were housed in separate negative pressure rooms at the Veterinary Science Research Station (VSRS) of the University of Calgary. Throughout the experiment, the chickens were provided with food and water ad libitum and the lighting scheme was adjusted for layer-type chickens (Hy-Line W36 commercial layers management guide 2020).

Two groups received the live attenuated IB vaccine at 2, 5, and 9 weeks of age. At 16 weeks of age, the first group received the Mass type commercial inactivated vaccine (MV), while the second group was administered the DMV/1639 type in-house prepared inactivated oil-emulsion vaccine (DV). The third group remained as the non-vaccinated control (NV). At 21 weeks of age, 10 hens from each group were bled for serum collection. At 35 weeks of age, 9 hens from each group were transferred to 3 separate rooms and subjected to an oculo-nasal challenge at a dose of 1 × 106 EID50 (MV-C, DV-C, and NV-C groups). The remaining 9 hens in each group were kept as non-challenged controls (MV-NC, DV-NC, and NV-NC groups).

2.5. Clinical observation and antemortem sampling

All groups were closely monitored for clinical signs and egg production over a period of 12 days post-infection (dpi) before being euthanized. At 3, 7, and 12 dpi, oropharyngeal (OP) and cloacal (CL) swabs were collected in 1 ml of cold PBS and stored at −80 °C. At 12 dpi, sera were separated from collected blood and stored at −20 °C.

2.6. Necropsy and postmortem sampling

Following euthanasia, necropsy was conducted to detect the gross lesions, and the length of the oviducts was measured. The oviduct washes were collected by injecting and gently massaging 10 ml of cold PBS along the entire length of the oviduct. Samples were taken from the trachea, lung, kidney, cecal tonsils, ovary, magnum, isthmus, and uterus and preserved in RNA Save® (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel) for storage at −80 °C. Additionally, the samples were also stored in 10% neutral buffered formalin (VWR International, Edmonton, AB, Canada).

2.7. Techniques

2.7.1. Virus neutralization (VN) assay

The β-method of VN test, which involves using constant virus concentration and varying antiserum, was carried out using 10-day-old SPF embryonated chicken eggs. Individual serum samples collected from chickens in each group at 21 weeks of age were pooled, and the complement was inactivated by heating at 56 °C for 30 minutes (min). Two-fold dilutions of the sera were mixed with a 200 EID50 of the challenge virus and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The virus-serum mixtures were then inoculated into 5 eggs, which were incubated for 7 days post inoculation to record embryo deaths and IBV-specific lesions. The VN titers, expressed as the highest serum dilution that neutralized 50% of the virus, were calculated by the Spearman–Kärber method (Cottral, 1978).

2.7.2. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Specific IBV antibodies were assessed in 1:500 dilutions of the serum samples and 1:10 dilutions of the oviduct washes using a commercially available IBV ELISA kit (IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., Westbrook, ME, USA), following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. The manufacturer's specified formula was employed to compute the antibody titers, whereas a titer of ≥ 396 was used as a positive cut-off value.

2.7.3. IBV genome load quantification

Trizol® reagent (Invitrogen Canada Inc., Burlington, ON, Canada) was used to extract total RNA from tissue and swab samples following the manufacturer's instruction. The quantity and purity assessment of the extracted RNA were conducted using a Nanodrop1000 spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) by measuring the absorbance at a wavelength of 260/280 nm. The RNA extracted from swabs and tissues, at quantities of 1 µg and 2 µg respectively, were initially reverse-transcribed with random primers (High-Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit™, Applied Biosystems, Invitrogen Canada Inc., Burlington, ON, Canada) as per the manufacturer's guidelines. The IBV genome was quantified in the cDNA using a qRT-PCR assay that utilizes PerfeCTa SYBR® Green FastMix (Quntabio®, Beverly, MA, USA) and primes designed to detect a specific region of the N gene as previously described (Kameka et al., 2014). The sensitivity of the qRT-PCR assay was determined as 100 copies per 100 ng of RNA. As was previously shown for turkey corona virus quantification, qRT-PCR assay is more sensitive than virus isolation (Breslin et al., 2000).

2.7.4. Histopathology

Tissues samples preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin were embedded in paraffin wax and then sliced into sections measuring 5 µm in thickness. These sections were subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) at the Diagnostic Services Unit (DSU) of the University of Calgary. Finally, the stained sections were examined using a light microscope (Olympus BX51, Center Valley, PA, USA). The IBV- presumptive lesions (Table 1) were evaluated and classified in scores according to a scoring system previously published by Benyeda et al. (Benyeda et al., 2010) and Chousalkar et al. (Chousalkar et al., 2007) with some modifications. The lesions were subcategorized as follows: no change (0), mild (1), moderate (2) or severe (3).

Table 1.

The IBV-assigned lesions for histopathological scores.

| Tissue | Lesions |

|---|---|

| Trachea | Epithelial hyperplasia Dilated mucosal glands Inflammatory cell infiltrations in lamina propria |

| Lung | Peribronchitis Inflammatory cell infiltrations in the interparabronchial septum |

| Kidney | Necrosis of renal tubular epithelium Inflammatory cell infiltrations in the interstitial tissue |

| Ovary | Necrosis of ovarian covering epithelium Heterophilic and/or mononuclear cell infiltrations in the cortical stroma |

| Magnum, isthmus, and uterus | Epithelial cell necrosis Loss of cilia Inflammatory cell infiltrations in lamina propria Edema and/or congestion in lamina propria |

2.7.5. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The paraffin embedded tissue sections were first deparaffinized and rehydrated. The endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersing the tissue sections in a solution of 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min at room temperature. The epitopes were exposed through heat-induced antigen retrieval using a 10 mM citrate buffer with a pH of 6.0. A blocking solution, consisting of 2% goat serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.05% Tween 20 in 0.01 M PBS, was applied to the tissue sections for 1 h at room temperature. The tissue sections were then incubated overnight with mouse anti-chicken CD8a (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) diluted 1:100 in 2.5% goat serum at 4 °C. Subsequently, the tissue sections were treated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and incubated for a duration of 30 min. The tissue sections were then treated with an avidin-biotin complex (ABC) kit (Vectastain® ABC kit, Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) and incubated for 30 min. Finally, the sections were subjected to 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrate solution (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) for visualization, counterstained with Gill's Hematoxylin (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA), and subsequently mounted and cover-slipped. The CD8+ T cells were counted in 5 different microscopic fields per tissue section at 20 x magnification, and the percentages of positive cells were calculated relative to the total nuclei in each field using Fiji software (Schindelin et al., 2012).

2.7.6. Statistical analysis

Data analysis and graph creation were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.0.1 Software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Fisher's exact test was used to compare the proportions of daily egg production and the incidence of yolk peritonitis between all experimental groups. For the comparison of IBV genome loads in swabs over different time points, a 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test was employed. Kruskal-Wallis's test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test was used to compare the mean lesion scores between all experimental groups. All other parameters were compared between all experimental groups using a 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

3. Results

3.1. In-house prepared IBV DMV/1639 inactivated oil-emulsion vaccine

The inactivation of the virus was verified through the absence of specific IBV signs such as death, dwarfism, stunting, and curling of inoculated embryos after three passages. The prepared vaccine was confirmed to be free from any bacterial or fungal contamination. The emulsion type, particle size, viscosity, and stability of the vaccine suspension aligned with the recommendations of the oil-emulsion manufacturer.

3.2. Pre-challenge serum anti-IBV antibody and VN titers

At approximately 5 weeks post-administration of the inactivated vaccines, serum samples were collected from the hens to assess the impact of the vaccination programs on immune responses, employing ELISA and VN techniques. Th results of the ELISA test showed positive antibody titers in MV and DV groups, while no antibodies were detected in the NV group. Additionally, the antibody titer in the MV group was significantly higher than the titer of the DV group (P < 0.05; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

IBV ELISA titers in pre-challenge serum collected at 21 weeks of age. Mean titers were compared using 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test. The error bars represent the standard deviation (SD). Significant differences are denoted by different letters above the bars (P < 0.05).

On the other hand, the VN test showed that the serum of the DV group exhibited a higher VN titer (≥256) compared to the VN titer of the MV group (≥8) against the challenge virus.

3.3. Clinical observations, egg production, and necropsy findings

No overt clinical signs were observed in either the challenged or non-challenged groups. Fig. 2 displays the egg production data recorded for each group from 1 to 12 dpi. Throughout the observation period, all groups maintained egg production rates ranging from 77.8% to 100%, with the exception of the NV-C group, which exhibited a decrease in egg production below these rates starting at 5 dpi. Notably, a statistically significant decline in average egg production was observed in the NV-C group between 7 and 12 dpi (P < 0.05), with the lowest egg production rate of 33.3% recorded on 8, 10, and 11 dpi. Moreover, the hens in the NV-C group produced soft-shelled eggs between 2 and 6 dpi.

Fig. 2.

The daily percentage of egg production in all experimental groups between 1- and 12-days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain. The proportions of daily egg production were compared between all experimental groups using Fisher's exact test. Significant differences are denoted by different letters above each time point (P < 0.05). The dagger symbol represents the percentages of soft-shelled eggs produced by the NV-C group.

During the postmortem examination, ovarian and oviductal activity was documented, along with the detection of free yolk within the abdominal cavity and/or peritonitis. In the NV-C group, 2 hens exhibited inactive ovaries, 3 hens had atrophied oviducts, and 5 hens showed signs of yolk peritonitis (Fig. 3A). Statistically, the NV-C group demonstrated significantly shorter oviduct length compared to the NV-NC group (P < 0.05; Fig. 3B), and a higher incidence of yolk peritonitis compared to all other groups (P < 0.05). One hen in the MV-C group had swollen kidneys. No evident gross lesions were observed in the hens of the remaining groups.

Fig. 3.

(A) Gross lesions observed at 12 days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain. The left image displays a normal ovary (green arrow) and oviduct (red arrow), the middle image exhibits an inactive ovary (green arrow) and atrophied oviduct (red arrow), and the right image illustrates the presence of free yolk in the abdominal cavity accompanied by peritonitis (green arrow). (B) Mean oviduct lengths (measured in centimeters) of all experimental groups at 12 days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/ 17–036989 strain. The mean oviduct lengths were compared between all experimental groups using 1-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test, and the error bars represent the SD. Significant differences are denoted by different letters above the bars (P < 0.05).

3.4. OP and CL viral shedding

The pattern of the IBV shedding through the OP and CL routes is shown in Fig. 4. The non-challenged groups consistently displayed undetectable levels of IBV genome loads in both the OP and CL swabs throughout the entire duration of the study. In contrast, the DV-C group exhibited a significant reduction in IBV genome loads in the OP swabs compared to the NV-C group at 3 and 7 dpi (P < 0.05), while the IBV genome loads in the OP swabs of the MV-C group did not significantly differ from either the DV-C or NV-C groups at the same time points (P > 0.05). By 12 dpi, the IBV genome loads in the OP swabs of all challenged groups had dropped below the limit of detection.

Fig. 4.

IBV genome loads in OP and CL swabs collected from all experimental groups at 3-, 7-, and 12-days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain. The average IBV RNA copies was quantified per 100 ng of the extracted RNA and differences between all experimental groups were identified using 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test, and the error bars represent the SD. Significant differences are denoted by different letters above the bars (P < 0.05).

The DV-C group displayed the lowest IBV genome loads in the CL swabs, which were not significantly higher compared to the non-challenged groups at 3, 7, and 12 dpi (P > 0.05). However, they were also not significantly lower than the IBV genome loads in the CL swabs of the NV-C group (P > 0.05), except for at 7 dpi (P < 0.05). In the MV-C group, the IBV genome loads in the CL swabs were not significantly different from those of the NV-C group at all time points examined (P > 0.05). Notably, in the DV-C group, 4 hens at 7 dpi and 6 hens at 12 dpi had no detectable viral genome, while in the MV-C group, only 2 hens had no detectable viral genome at both time points.

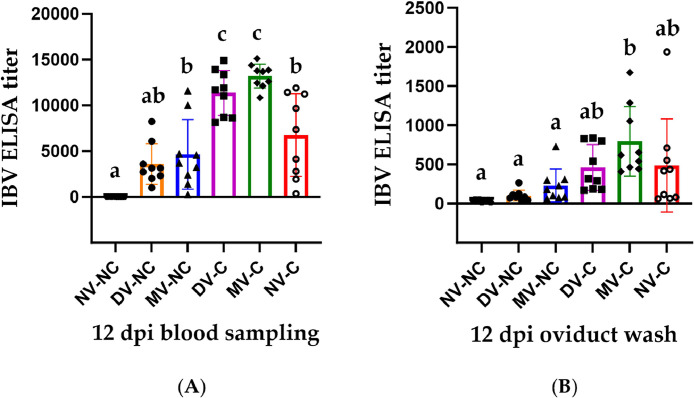

3.5. Anti-IBV antibody titers in serum and oviduct washes at 12 dpi

There was a significant increase in the serum anti-IBV antibody titers in both the DV-C and MV-C groups compared to all other experimental groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 5A). In contrast, the serum anti-IBV antibody titer of the NV-C group was similar to those of the DV-NC and MV-NC groups (P > 0.05; Fig. 5A). In oviduct washes, only the MV-C group demonstrated significantly higher levels of anti-IBV antibodies compared to the non-challenged groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 5B). Additionally, the antibody titers in the DV-C and NV-C groups did not exhibit significant differences when compared to either the MV-C group or the non-challenged groups (P > 0.05; Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

IBV ELISA titers detected in serum (A) and oviduct washes (B) collected from all experimental groups at 12 days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036,989 strain. The mean titers were compared between all experimental groups using 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test, and the error bars represent the SD. Significant differences are denoted by different letters above the bars (P < 0.05).

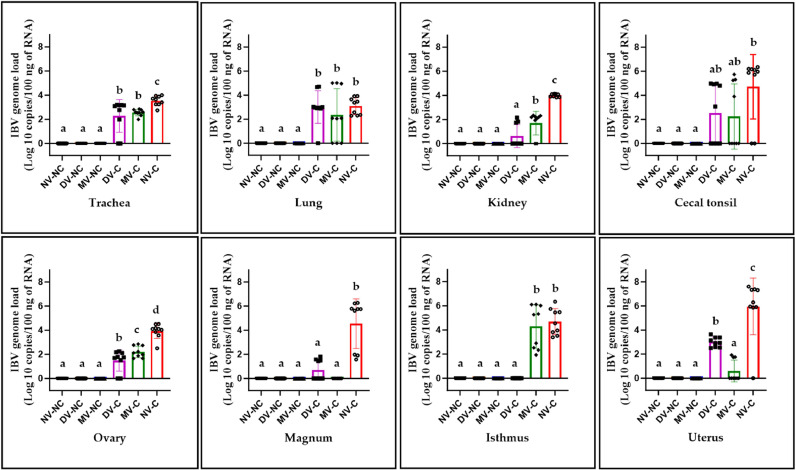

3.6. Quantification of IBV genome loads in tissues

The non-challenged groups had no detectable IBV genome in all tissues examined. The DV-C and MV-C groups demonstrated a significant reduction in the IBV genome loads in the trachea, kidney, ovary, magnum, and uterus compared to the NV-C group (P < 0.05; Fig. 6). However, no comparable reduction was observed in the lung and cecal tonsil (P > 0.05; Fig. 6). Notably, the DV-C group displayed significantly lower IBV genome loads in the kidney, ovary, and isthmus compared to both the MV-C and NV-C groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 6). In the uterus, the DV-C group had statistically significantly higher levels of the IBV genome than the MV-C group (P < 0.05; Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

IBV genome loads in trachea, lung, kidney, cecal tonsil, ovary, magnum, isthmus, and uterus collected from all experimental groups at 12 days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain. The average IBV RNA copies was quantified per 100 ng of the extracted RNA and differences between all experimental groups were identified using 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test, and the error bars represent the SD. Significant differences are denoted by different letters above the bars (P < 0.05).

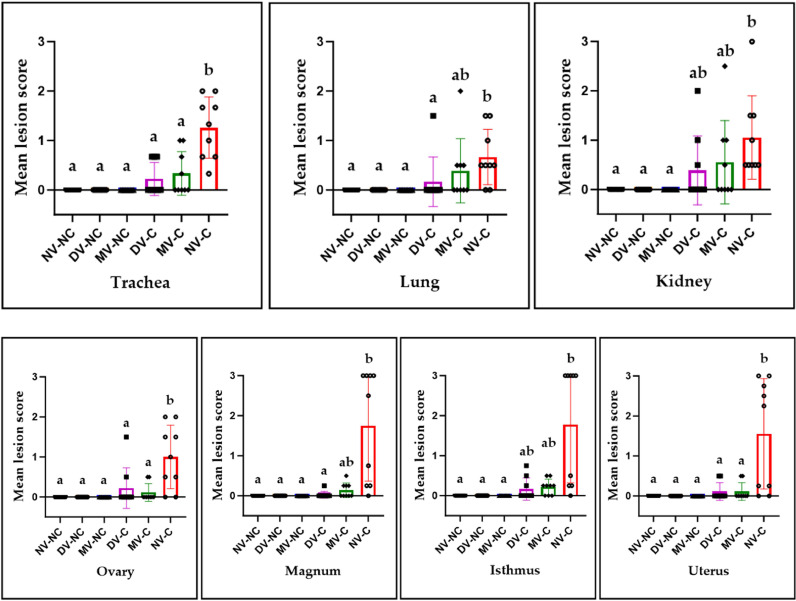

3.7. Histopathology

In the non-challenged groups, no significant histopathological lesions were observed in the trachea, lung, kidney, ovary, magnum, isthmus, and uterus (Fig. 7A a1-c1; Fig. 7B d1-g1).

Fig. 7.

Histopathological lesions observed in all experimental groups at 12 days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain. (A) Representative images of trachea, lung, and kidney. Black arrowhead refers to epithelial hyperplasia; short black arrows indicate dilated mucosal glands; black arrows show inflammatory cell infiltrations; empty triangle reveals atrophied renal tubule. (B) Representative images of ovary, magnum, isthmus, and uterus. Black dotted arrows show epithelial sloughing; white dotted arrow reveals epithelial attenuation; black arrows refer to mononuclear cell infiltrations; white arrows indicate heterophilic cell infiltrations; double black arrows refer to congested blood vessels; short white arrows indicate edema.

In the NV-C group, histopathological examination revealed notable changes in all tissues examined. The trachea exhibited hyperplasia of the lining epithelium accompanied by dilated mucosal glands, while the lamina propria showed infiltration of mononuclear cells, predominantly of lymphocytic type (Fig. 7A a2). In the lung, mononuclear cell infiltrations were observed in the lamina propria of the tertiary bronchi (Fig. 7A b2). The kidney demonstrated marked thickening of the interstitial connective tissue, attributed to lymphoplasmacytic cell infiltrations, with concurrent presence of atrophied renal tubules (Fig. 7A c2). The ovary exhibited focal sloughing of the ovarian epithelium, accompanied by invasion of mononuclear cells in the cortical stroma, either focally or multifocally (Fig. 7B d2). Occasional heterophilic cell infiltrations were observed in some birds. Notable epithelial changes were observed along the oviduct, including attenuation and deciliation in the uterus, and complete loss of epithelial and ciliary structures in the magnum and isthmus. The lamina propria of the oviduct showed multifocal mononuclear cell infiltrations, as well as edema and congestion in certain blood vessels (Fig. 7B e2, f2, g2).

In both the MV-C and DV-C groups, the microscopic alterations observed in the examined tissues were largely similar. The lesions consisted primarily of inflammatory cell infiltrations and/or circulatory changes, while the lining epithelia were intact in all examined tissues. Notably, the trachea exhibited lymphocytic cell infiltrations in the lamina propria (Fig. 7A a3, a4), and the lung displayed mononuclear cell infiltrations in the lamina propria of the secondary bronchi (Fig. 7A b3, b4). The kidney revealed mild to moderate lymphoplasmacytic cell infiltrations in the interstitium (Fig. 7A c3, c4). Heterophilic cells infiltrated the cortical stroma of the ovary (Fig. 7B d3, d4). In the magnum and uterus, congestion of certain blood capillaries and subepithelial tissue edema were observed, respectively (Fig. 7B e3, e4; Fig. 7B g3, g4). Additionally, the isthmus demonstrated evidence of mononuclear cell infiltrations in the lamina propria (Fig. 7B f3, f4).

The mean lesion scores in the MV-C and DV-C groups were generally lower compared to the NV-C group (Fig. 8). The MV-C and DV-C groups demonstrated a significant reduction in mean lesion scores for the trachea, ovary, and uterus compared to the NV-C group (P < 0.05). There was no statistically significant difference in mean lesion scores for the kidney and isthmus observed among the challenged groups (P > 0.05); however, the scores in the MV-C and DV-C groups did not show a significant increase compared to the non-challenged groups (P > 0.05). In the lung and magnum, only the DV-C group exhibited a significantly lower mean lesion scores compared to the NV-C group (P < 0.05). It is worth noting that in all tissues examined only a few hens in the DV-C and MV-C groups demonstrated visible microscopic lesions compared to the NV-C group (Table 2).

Fig. 8.

Mean lesion scores in trachea, lung, kidney, ovary, magnum, isthmus, and uterus at 12 days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain. Mean lesion scores were calculated according to the severity of the observed lesions in 9 hens per group and differences between groups were compared using Kruskal–Wallis’ test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test, and the error bars represent the SD. Significant differences are denoted by different letters above the bars (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

The number of hens with visible microscopic lesions in tissues examined at 12 days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain.

| Group | Tissue | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trachea | Lung | Kidney | Ovary | Magnum | Isthmus | Uterus | |

| NC | 0/9 | 0/9 | 0/9 | 0/9 | 0/9 | 0/9 | 0/9 |

| DV-C | 3/9 | 1/9 | 3/9 | 2/9 | 1/9 | 3/9 | 2/9 |

| MV-C | 4/9 | 4/9 | 4/9 | 2/9 | 4/9 | 6/9 | 2/9 |

| NV-C | 9/9 | 7/9 | 9/9 | 7/9 | 8/9 | 8/9 | 7/9 |

3.8. CD8+ T cell recruitment

Representative images of the CD8+ T cells immune reactivity in the tissues of the NV-C group are shown in Fig. 9. The trachea, ovary, magnum, and uterus of the NV-C group exhibited significantly higher recruitment of CD8+ T cells compared to all other groups (P < 0.05; Fig. 10). Additionally, the NV-C group showed a significant increase in CD8+ T cells recruitment in the kidney compared to all other groups (P < 0.05), except for the MV-C group (P > 0.05; Fig. 10). However, there were no significant differences observed in the cecal tonsil among all groups (P > 0.05; Fig. 10). Notably, no statistically significant differences were found between the DV-C and MV-C groups in all tissues examined (P > 0.05; Fig. 10).

Fig. 9.

Immunohistochemical detection of CD8+ T cells in trachea (a), lung (b), kidney (c), cecal tonsil (d), ovary (e), magnum (f), isthmus (g), and uterus (h) collected at 12 days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036,989 strain. CD8+ T cells were stained with dark brown (indicated with black arrows). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Fig. 10.

Image analysis of CD8+ T cells in trachea, lung, kidney, cecal tonsil, ovary, magnum, isthmus, and uterus collected at 12 days following infection with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036,989 strain. The percentages of CD8+ T cells were compared between all experimental groups using 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test, and the error bars represent the SD. Significant differences are denoted by different letters above the bars (P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

IBV infection in laying chickens is a continuous challenge that needs constant improvements to the implemented control measures in the field (Bhuiyan et al., 2021). In recent years, the Canadian layer industry has experienced an increasing incidence of poor egg-laying performance due to the emergence of the IBV DMV/1639 type strains (Hassan et al., 2021; Hassan et al., 2022a). The aim of this study was to compare the level of protection against the challenge with the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain in layers using vaccination programs incorporating a commercial inactivated Mass type vaccine or a locally prepared autogenous inactivated DMV/1639 type vaccine following heterologous live priming with Mass and Conn IB vaccines. The ELISA and VN antibody responses to vaccination were determined. The number and quality of eggs laid, viral loads in swabs and tissues, gross and microscopic lesions, and humoral and cellular immunological responses were also determined.

The laying chickens used in the current study were at the time of peak egg production. Thus, all experimental groups had an average egg production rate of 95.4% over the first 4 days of the experiment. This confirmed the validity of the study and helped to effectively demonstrate the variations in egg production rates between the groups resulting from the challenge. All challenged groups had no noticeable clinical signs; however, it is not unusual for infected adult chickens to exhibit no apparent respiratory signs, even when experiencing evident egg production disorders (Muneer et al., 1987). The NV-C group showed a marked drop in egg production that began at 5 dpi, with statistically lower egg production rates observed from 7 dpi until the end of the experiment. Additionally, the NV-C group produced soft-shelled eggs between 2 and 6 dpi. In contrast, the MV-C and DV-C groups were protected from the adverse effects on both the quantity and quality of produced eggs observed in the NV-C group. Gross pathological changes in the reproductive organs were only observed in the NV-C group. The damage to the reproductive tract involved regressed ovaries and atrophied oviducts as well as a significantly higher incidence of yolk peritonitis. One hen in the MV-C group showed swollen kidneys, which is not surprising since the challenge strain was associated with urogenital problems both experimentally and in the field (Hassan et al., 2021; Hassan et al., 2019; Hassan et al., 2022a).

Apart from the egg-laying performance, the assessment of other protective parameters associated with virus shedding and its spread to different organs is considered critical. Prolonged virus shedding, particularly through the CL route, could play a crucial role in transmitting the virus to new locations or causing acute infections to reoccur within the same flock (Jones and Ambali, 1987; Alexander and Gough, 1978). In this concern, the vaccination scheme including the autogenous vaccine was effective in reducing the viral shedding through the OP and CL routes compared to the NV-C group. Although in most instances, the viral shedding of the MV-C group did not differ significantly from that of the DV-C group, the latter demonstrated higher proportions of hens displaying undetectable viral shedding at 7 and 12 dpi (Fig. 4). Viral RNA loads were significantly reduced in the tracheal, kidney, ovarian, magnum, and uterine tissues of the MV-C and DV-C groups compared to the NV-C group. However, the DV-C group displayed a higher efficacy in decreasing the IBV loads in the kidney, ovary, and isthmus compared to the MV-C group. Notably, the kidney is a prominent site for potential IBV persistence (Naqi et al., 2003). The evolution of the persistent IBV through mutation and recombination within chicken tissues has serious consequences for disease control (Santos Fernando et al., 2017). Furthermore, the ability of the vaccination program to further reduce the virus dissemination to the reproductive organs could potentially improve the protection had the experiment been extended for a longer period or the hens were infected at a different stage of laying period.

Another crucial aspect to consider in terms of protection is the evaluation of histopathological changes since IBV infection could cause microscopic lesions without any visible macroscopic changes (Winterfield and Albassam, 1984; Najimudeen et al., 2021). The MV-C and DV-C groups had generally lower mean lesion scores compared to the NV-C group, with statistically different scores observed in the trachea, ovary, and uterus. The lung and magnum of the DV-C group also showed significantly lower mean lesion scores compared to the NV-C group. Notably, even when statistically significant differences were absent, higher proportions of the hens in the MV-C and DV-C groups had no detectable microscopic lesions (Fig. 8 and Table 2). Furthermore, the nature of the lesions differed markedly between the challenged groups. While notable epithelial changes were observed in the IBV-susceptible tissues of the NV-C group, the epithelial lining of these tissues looked healthy in the MV-C and DV-C groups. This observation is particularly interesting since IBV is primarily an epitheliotropic virus (Cavanagh, 2007), which emphasizes the effectiveness of the vaccination programs used.

Understanding the immune responses to pathogenic and vaccine IBV strains is important for improving intervention programs (Chhabra et al., 2015). In the current study, the adaptive antibody- and cellular-mediated immune responses were investigated. Both group‐specific and serotype‐specific antibodies were measured in serum samples collected 5 weeks after the application of the inactivated vaccines using ELISA and VN techniques, respectively. While both the MV and DV groups showed a significant increase in their IBV ELISA titers, the MV group displayed a significantly higher titer compared to the DV group. It is well-established that live vaccine priming is necessary for inactivated IB vaccines to generate a potent immune response (Box et al., 1988; de Wit et al., 2022; Ali et al., 2023). Thus, it is not surprising that the homologous inactivated Mass type vaccine induced a higher antibody response than the heterologous inactivated DMV/1639 type vaccine as previously reported (Ladman et al., 2002). Additionally, the commercial ELISA kit may be detecting both group-specific and serotype-specific antibodies in the MV group, especially if the Mass serotype was used to coat the ELISA plates (the specific serotype is undisclosed). In contrast, when serotype-specific antibodies against the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain were measured, the VN titer of the DV group was remarkably higher compared to the VN titer of the MV group. While this observation is inconsistent with the previous findings of de Wit et al. (de Wit et al., 2019; de Wit et al., 2022), it can be deduced that the combinations of vaccines employed might influence the level of VN titers against heterologous IBV strains. Following the challenge, IBV ELISA titers of the MV-C and DV-C groups showed a significant increase compared to all other groups. The challenge resulted in a more rapid and elevated antibody reaction in both vaccinated groups, possibly generated in response to conserved antigenic determinants either within or outside the S glycoprotein (Wang et al., 1995; Williams et al., 1992). Notably, the genome backbone of the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain, except for the spike gene, is highly similar to a Conn-like vaccine strain (Hassan et al., 2019), which constitutes a principal element of our vaccination regimen. Positive titers of specific IBV antibodies were also detected in the oviduct washes of the challenged groups. Although the role of the humoral antibodies in protection against IBV is controversial, the finding of this study and earlier studies are in favor of that high levels of serum and local antibodies could be important for tissue protection (Box et al., 1988; Raj and Jones, 1996). On the other hand, the role of the cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in controlling IBV infection is commonly recognized (Collisson et al., 2000; Seo and Collisson, 1997). In the current study, the recruitment of the CD8+ T cells in most tissues examined was significantly higher in the NV-C group compared to all other groups. This observation aligns with the elevated IBV loads detected in the tissues of the NV-C group, and is consistent with prior research reporting a higher cytotoxic T cell infiltrations concurrently with the increase of IBV antigen levels in the tissues (Hassan et al., 2022a; Kotani et al., 2000).

In summary, the current study was designed to answer an intriguing question that arises when new IBV variants emerge and pose a challenge to the industry: Is it necessary to employ homologous IB vaccines to elicit protection, or can the existing licensed vaccines confer heterologous protection? Despite the slightly higher efficacy of adding an autogenous vaccine, the heterologous vaccination approach, involving live IB vaccine priming followed by inactivated vaccine injection, effectively protected the layers against the IBV/Ck/Can/17–036989 strain infection.

Funding

This research was funded by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Alliance grant (grant #: 10032197) and Egg Farmers of Canada (EFC, grant number 10025236).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohamed S.H. Hassan: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ahmed Ali: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Motamed Elsayed Mahmoud: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Danah Altakrouni: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Shahnas M. Najimudeen: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Mohamed Faizal Abdul-Careem: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Resources, Data curation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the University of Guelph for kindly providing us the IBV-infected samples from which the virus was isolated. We acknowledge the help of the staff including Greg Boorman at the Veterinary Science Research Station at Spyhill campus, University of Calgary for the animal management.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Al-Ebshahy E., Abdel-Sabour M., Abas O., Yanai T. Protection conferred by a vaccine derived from an inactivated Egyptian variant of infectious bronchitis virus: a challenge experiment. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2019;51:1997–2001. doi: 10.1007/s11250-019-01898-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander D.J., Gough R.E. A long-term study of the pathogenesis of infection of fowls with three strains of avian infectious bronchitis virus. Res. Vet. Sci. 1978;24:228–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali A., Hassan M.S.H., Najimudeen S.M., Farooq M., Shany S., El-Safty M.M., Shalaby A.A., Abdul-Careem M.F. Efficacy of two vaccination strategies against infectious bronchitis in laying hens. Vaccines (Basel) 2023;11:338. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11020338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bande F., Arshad S.S., Omar A.R., Hair-Bejo M., Mahmuda A., Nair V. Global distributions and strain diversity of avian infectious bronchitis virus: a review. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2017;18:70–83. doi: 10.1017/s1466252317000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyeda Z., Szeredi L., Mató T., Süveges T., Balka G., Abonyi-Tóth Z., Rusvai M., Palya V. Comparative histopathology and immunohistochemistry of QX-like, Massachusetts and 793/B serotypes of infectious bronchitis virus infection in chickens. J. Comp. Pathol. 2010;143:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan M.S.A., Amin Z., Bakar A., Saallah S., Yusuf N.H.M., Shaarani S.M., Siddiquee S. Factor influences for diagnosis and vaccination of avian infectious bronchitis virus (gammacoronavirus) in chickens. Vet. Sci. 2021;8:47. doi: 10.3390/vetsci8030047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box P.G., Holmes H.C., Finney P.M., Froymann R. Infectious bronchitis in laying hens: the relationship between haemagglutination inhibition antibody levels and resistance to experimental challenge. Avian Pathol. 1988;17:349–361. doi: 10.1080/03079458808436453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslin J.J., Smith L.G., Barnes H.J., Guy J.S. Comparison of virus isolation, immunohistochemistry, and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction procedures for detection of turkey coronavirus. Avian Dis. 2000;44:624–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D., Davis P.J., Cook J.K., Li D., Kant A., Koch G. Location of the amino acid differences in the S1 spike glycoprotein subunit of closely related serotypes of infectious bronchitis virus. Avian Pathol. 1992;21:33–43. doi: 10.1080/03079459208418816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus. Vet. Res. 2007;38:281–297. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra R., Chantrey J., Ganapathy K. Immune responses to virulent and vaccine strains of infectious bronchitis viruses in chickens. Viral Immunol. 2015;28:478–488. doi: 10.1089/vim.2015.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chousalkar K.K., Roberts J.R., Reece R. Comparative histopathology of two serotypes of infectious bronchitis virus (T and n1/88) in laying hens and cockerels. Poult. Sci. 2007;86:50–58. doi: 10.1093/ps/86.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collisson E.W., Pei J., Dzielawa J., Seo S.H. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes are critical in the control of infectious bronchitis virus in poultry. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2000;24:187–200. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(99)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J.K., Orbell S.J., Woods M.A., Huggins M.B. Breadth of protection of the respiratory tract provided by different live-attenuated infectious bronchitis vaccines against challenge with infectious bronchitis viruses of heterologous serotypes. Avian Pathol. 1999;28:477–485. doi: 10.1080/03079459994506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J.K., Jackwood M., Jones R.C. The long view: 40 years of infectious bronchitis research. Avian Pathol. 2012;41:239–250. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2012.680432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottral G.E. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, N. Y.: 1978. Serology. In Manual of Standardized Methods for Veterinary Microbiology; pp. 60–93. ed. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J.J., Boelm G.J., van Gerwe T.J., Swart W.A. The required sample size in vaccination-challenge experiments with infectious bronchitis virus, a meta-analysis. Avian Pathol. 2013;42:9–16. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2012.751485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J.J.S., Malo A., Cook J.K.A. Induction of IBV strain-specific neutralizing antibodies and broad spectrum protection in layer pullets primed with IBV Massachusetts (Mass) and 793B vaccines prior to injection of inactivated vaccine containing Mass antigen. Avian Pathol. 2019;48:135–147. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2018.1556778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J.J.S., De Herdt P., Cook J.K.A., Andreopoulou M., Jorna I., Koopman H.C.R. The inactivated infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) vaccine used as booster in layer hens influences the breadth of protection against challenge with IBV variants. Avian Pathol. 2022;51:244–256. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2022.2040731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erfanmanesh A., Ghalyanchilangeroudi A., Nikaein D., Hosseini H., Mohajerfar T. Evaluation of inactivated vaccine of the variant 2 (IS-1494 /GI-23) genotype of avian infectious bronchitis. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020;71 doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2020.101497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada: Canadian Food Inspection Agency: animal health: veterinary biologics: veterinary biologics licensed in Canada. Avaiable online: https://inspection.canada.ca/active/netapp/veterinarybio-bioveterinaire/vetbioe.aspx (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Habibi M., Karimi V., Langeroudi A.G., Ghafouri S.A., Hashemzadeh M., Farahani R.K., Maghsoudloo H., Abdollahi H., Seifouri P. Combination of H120 and 1/96 avian infectious bronchitis virus vaccine strains protect chickens against challenge with IS/1494/06 (variant 2)-like infectious bronchitis virus. Acta Virol. 2017;61:150–160. doi: 10.4149/av_2017_02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M.S.H., Ojkic D., Coffin C.S., Cork S.C., van der Meer F., Abdul-Careem M.F.Delmarva. (DMV/1639) infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) variants isolated in eastern canada show evidence of recombination. Viruses. 2019;11:1045. doi: 10.3390/v11111054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M.S.H., Ali A., Buharideen S.M., Goldsmith D., Coffin C.S., Cork S.C., van der Meer F., Boulianne M., Abdul-Careem M.F. Pathogenicity of the Canadian Delmarva (DMV/1639) infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) on female reproductive tract of chickens. Viruses. 2021;13:2488. doi: 10.3390/v13122488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M.S.H., Najimudeen S.M., Ali A., Altakrouni D., Goldsmith D., Coffin C.S., Cork S.C., van der Meer F., Abdul-Careem M.F. Immunopathogenesis of the Canadian Delmarva (DMV/1639) infectious bronchitis virus (IBV): impact on the reproductive tract in layers. Microb. Pathog. 2022;166 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M.S.H., Buharideen S.M., Ali A., Najimudeen S.M., Goldsmith D., Coffin C.S., Cork S.C., van der Meer F., Abdul-Careem M.F. Efficacy of commercial infectious bronchitis vaccines against Canadian Delmarva (DMV/1639) infectious bronchitis virus infection in layers. Vaccines (Basel) 2022;10:1194. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10081194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hy-Line W36 commercial layers management guide. Avaialble online: https://www.hyline.com/literature/W-36 (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Jackwood M.W., Hall D., Handel A. Molecular evolution and emergence of avian gammacoronaviruses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2012;12:1305–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackwood M.W., de Wit S. Vol. 13. John Wiley and Sons; Ames, IA, USA: 2013. Infectious bronchitis; pp. 139–159. (Diseases of Poultry). 13th ed.; Swayne, D.E., Glisson, R.J., McDougald, L.R., Nolan, L.K., Suarez, D.L., Nair, V., Eds. [Google Scholar]

- Jones R.C., Ambali A.G. Re-excretion of an enterotropic infectious bronchitis virus by hens at point of lay after experimental infection at day old. Vet. Rec. 1987;120:617–618. doi: 10.1136/vr.120.26.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan B. Vaccination against infectious bronchitis virus: a continuous challenge. Vet. Microbiol. 2017;206:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameka A.M., Haddadi S., Kim D.S., Cork S.C., Abdul-Careem M.F. Induction of innate immune response following infectious bronchitis corona virus infection in the respiratory tract of chickens. Virology. 2014;450-451:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotani T., Wada S., Tsukamoto Y., Kuwamura M., Yamate J., Sakuma S. Kinetics of lymphocytic subsets in chicken tracheal lesions infected with infectious bronchitis virus. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2000;62:397–401. doi: 10.1292/jvms.62.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladman B.S., Pope C.R., Ziegler A.F., Swieczkowski T., Callahan C.J., Davison S., Gelb J., Jr. Protection of chickens after live and inactivated virus vaccination against challenge with nephropathogenic infectious bronchitis virus PA/Wolgemuth/98. Avian Dis. 2002;46:938–944. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086(2002)046[0938:Pocala]2.0.Co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muneer M.A., Halvorson D.A., Sivanandan V., Newman J.A., Coon C.N. Effects of infectious bronchitis virus (Arkansas strain) on laying chickens. Avian Dis. 1986;30:644–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muneer M.A., Newman J.A., Halvorson D.A., Sivanandan V., Coon C.N. Effects of avian infectious bronchitis virus (Arkansas strain) on vaccinated laying chickens. Avian Dis. 1987;31:820–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najimudeen S.M., Hassan M.S.H., Goldsmith D., Ojkic D., Cork S.C., Boulianne M., Abdul-Careem M.F. Molecular characterization of 4/91 infectious bronchitis virus leading to studies of pathogenesis and host responses in laying hens. Pathogens. 2021;10:624. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10050624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqi S., Gay K., Patalla P., Mondal S., Liu R. Establishment of persistent avian infectious bronchitis virus infection in antibody-free and antibody-positive chickens. Avian Dis. 2003;47:594–601. doi: 10.1637/6087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomino-Tapia V. Poultry Farming - New Perspectives and Applications. IntechOpen; Rijeka, Croatia: 2023. Autogenous vaccines in the poultry industry: a field perspective. Tellez-Isaias, G., Ed.Ch. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Raj G.D., Jones R.C. Local antibody production in the oviduct and gut of hens infected with a variant strain of infectious bronchitis virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1996;53:147–161. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(95)05545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos Fernando F., Coelho Kasmanas T., Diniz Lopes P., da Silva Montassier M.F., Zanella Mores M.A., Casagrande Mariguela V., Pavani C., Moreira Dos Santos R., Assayag M.S., Jr., Montassier H.J. Assessment of molecular and genetic evolution, antigenicity and virulence properties during the persistence of the infectious bronchitis virus in broiler breeders. J. Gen. Virol. 2017;98:2470–2481. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S.H., Collisson E.W. Specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes are involved in in vivo clearance of infectious bronchitis virus. J. Virol. 1997;71:5173–5177. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5173-5177.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.A. Autogenous vaccines: current use patterns and end users' needs in the integrated broiler industry. Dev. Biol. (Basel) 2004;117:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valastro V., Holmes E.C., Britton P., Fusaro A., Jackwood M.W., Cattoli G. Monne, I. S1 gene-based phylogeny of infectious bronchitis virus: an attempt to harmonize virus classification. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016;39:349–364. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Parr R.L., King D.J., Collisson E.W. A highly conserved epitope on the spike protein of infectious bronchitis virus. Arch. Virol. 1995;140:2201–2213. doi: 10.1007/bf01323240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A.K., Wang L., Sneed L.W., Collisson E.W. Comparative analyses of the nucleocapsid genes of several strains of infectious bronchitis virus and other coronaviruses. Virus Res. 1992;25:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(92)90135-v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterfield R.W., Albassam M.A. Nephropathogenicity of infectious bronchitis virus. Poult. Sci. 1984;63:2358–2363. doi: 10.3382/ps.0632358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.