Abstract

Background:

Sexual minority individuals experience discrimination, leading to mental health disparities. Physical health disparities have not been examined to the same extent in systematic reviews so far.

Objectives:

To provide a systematic review and, where possible, meta-analyses on the prevalence of physical health conditions in sexual minority women (i.e. lesbian- and bisexual-identified women) compared to heterosexual-identified women.

Design:

The study design is a systematic review with meta-analyses.

Data Sources and Methods:

A systematic literature search in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases was conducted on epidemiologic studies on physical health conditions, classified in the Global Burden of Disease project, published between 2000 and 2021. Meta-analyses pooling odds ratios were calculated.

Results:

In total, 23,649 abstracts were screened and 44 studies were included in the systematic review. Meta-analyses were run for arthritis, asthma, back pain, cancer, chronic kidney diseases, diabetes, headache disorders, heart attacks, hepatitis, hypertension, and stroke. Most significant differences in prevalence by sexual identity were found for chronic respiratory conditions, especially asthma. Overall, sexual minority women were significantly 1.5–2 times more likely to have asthma than heterosexual women. Furthermore, evidence of higher prevalence in sexual minority compared to heterosexual women was found for back pain, headaches/migraines, hepatitis B/C, periodontitis, urinary tract infections, and acne. In contrast, bisexual women had lower cancer rates. Overall, sexual minority women had lower odds of heart attacks, diabetes, and hypertension than heterosexual women (in terms of diabetes and hypertension possibly due to non-consideration of pregnancy-related conditions).

Conclusion:

We found evidence for physical health disparities by sexual identity. Since some of these findings rely on few comparisons only, this review emphasizes the need for routinely including sexual identity assessment in health research and clinical practice. Providing a more detailed picture of the prevalence of physical health conditions in sexual minority women may ultimately contribute to reducing health disparities.

Keywords: bisexual women, lesbian women, meta-analysis, physical health disparities, sexual identity, sexual minority women, systematic review

Introduction

For many years, research on the health of sexual minority adults predominantly focused on sexually transmitted diseases (especially HIV in men) or—more recently—on mental health. 1 Regarding mental health, systematic reviews consistently reported disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals. For example, a meta-analysis found that adults who identify as lesbian or gay have a higher prevalence of mental disorders than their heterosexual counterparts. 2 Another systematic review found a twofold increased rate of suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. The risk for depression, anxiety disorders, and addiction was also 1.5 times higher compared to heterosexual individuals. 3

Today, mental and physical health is no longer understood as distinct entities. Instead, their interconnection or even interdependence is recognized. There are numerous reports from various populations of adverse physical health outcomes due to elevated psychological distress. For example, associations have been found between poorer mental health and immune system dysfunction, 4 decreased antibody responses following vaccinations, 5 increased vulnerability to colds, the flu, and headaches,6,7 as well as increased vulnerability to heart diseases and cancer. 8 Similar evidence has been provided for sexual minority populations specifically: in a US study, the higher distress sexual minority adults experienced compared to heterosexual adults explained most of the physical health differences observed between lesbian and heterosexual women (e.g. digestive symptoms, chronic fatigue syndrome, arthritis). 9

Lick et al. 1 provide a theoretical framework proposing that health disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals are related to minority stress processes that follow exposure to social stigma. Accordingly, elevated minority stress (e.g. discrimination, rejection, internalized homophobia) has been associated with higher numbers of chronic diseases and poorer overall health. 10 Regarding preconditions for good or bad physical health—apart from elevated (minority) stress—sexual minority individuals were found to be more likely to engage in disadvantageous health behavior, 11 such as excessive drinking, 12 smoking, 13 and exercising less. 14 Furthermore, a US study indicated that sexual minority persons have poorer access to health care as well as less insurance coverage. 15 A comprehensive meta-analytic review on perceived discrimination and health concluded that discrimination is associated with mental and physical health both directly as well as indirectly via heightened stress responses and participation in unhealthy and non-participation in healthy behaviors. 11

Only recently, studies on physical health among sexual minority individuals have increased considerably, and systematic reviews covering a broad range of physical diseases are rare. There are three reviews that each comprise selected physical health conditions in sexual minority women (SMW) compared to heterosexual women.16 –18 In one review from 2017, out of five health problems, only asthma was more common in SMW, whereas no significant differences were found for diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and most cancers. 16 The most recent review from 2018 included meta-analyses and found similar results, that is, higher asthma rates in lesbian and bisexual women, but no differences in CVD, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. 17 Another review (2014) including 11 studies found that almost every comparison was in a direction indicating better physical health in heterosexual compared to SMW. 18

Since these reviews have focused on only a few selected diseases each, and a considerable number of further studies have been released since then, there is a need for an up-to-date review that provides a comprehensive summary. Thus, this study aims to provide a systematic review and meta-analyses on the prevalence of physical health conditions, comparing lesbian-identified or/and bisexual-identified women or SMW (lesbian- and bisexual-identified aggregated) to heterosexual-identified women.

Methods

Reporting follows the PRISMA guideline for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. 19 Since this is a systematic review, no ethics approval from the ethics committee of the University was needed. The project was preregistered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42021281490) (Registration includes consideration of women and men; results on men are reported elsewhere.).

Study eligibility and inclusion criteria

Regarding physical health conditions, we followed the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) classification. The GBD is a comprehensive regional and global burden of disease research program that assesses mortality and disability from major diseases, injuries, and risk factors. It was initiated by the Harvard University, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Bank. 20 We included studies on health conditions of all GBD main- and sub-categories as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physical health conditions eligible for inclusion according to Global Burden of Disease classification.

| Cardiovascular diseases |

| Aortic aneurysm, atrial fibrillation, cardiomyopathy, endocarditis, hypertensive heart disease, ischemic heart disease, nonrheumatic valve diseases, other cardiovascular, peripheral artery disease, rheumatic heart disease, stroke |

| Chronic respiratory diseases |

| Asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), interstitial lung disease, other chronic respiratory, pneumoconiosis |

| Diabetes and chronic kidney diseases |

| Acute glomerulonephritis, chronic kidney disease, diabetes |

| Digestive diseases |

| Appendicitis, cirrhosis, gallbladder and biliary, hernia, ileus and obstruction, inflammatory bowel, other digestive diseases, pancreatitis, upper digest diseases, vascular intestinal |

| Enteric infections |

| Diarrheal diseases, invasive non-typhoidal salmonella (iNTS), other intestinal infect, typhoid and paratyphoid |

| Maternal and neonatal disorders |

| Maternal disorders, neonatal disorders |

| Musculoskeletal disorders |

| Gout, low back pain, neck pain, osteoarthritis, other musculoskeletal disorder, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Neglected tropical diseases and malaria |

| African trypanosomiasis, Chagas disease, cystic echinococcosis, cysticercosis, dengue, ebola, food-borne trematodiases, guinea worm, intestinal nematode, leishmaniasis, leprosy, lymphatic filariasis, malaria, onchocerciasis, other neglected tropical diseases (NTD), rabies, schistosomiasis, trachoma, yellow fever, zika virus |

| Neoplasms |

| Bladder cancer (c.), brain c., breast c., cervical c., colorectal c., esophageal c., gallbladder c., hodgkin lymphoma, kidney c., larynx c., leukemia, lip oral cavity c., liver c., lung c., lymphoma, melanoma, mesothelioma, myeloma, nasopharynx c., other malignant neoplasms, other neoplasms, other pharynx c., ovarian c., pancreatic c., prostate c., skin c., stomach c., testicular c., thyroid c., uterine c. |

| Neurological disorders |

| Alzheimer’s disease, headache disorders, epilepsy, motor neuron disease, multiple sclerosis, other neurological, Parkinson’s disease |

| Nutritional deficiencies |

| Dietary iron deficiency, iodine deficiency, other nutritional, protein-energy malnutrition, vitamin A deficiency |

| Other infectious diseases |

| Acute hepatitis, diphtheria, encephalitis, measles, meningitis, other unspecified infectious diseases, tetanus, varicella, whooping cough |

| Other non-communicable diseases |

| Congenital defects, gynecological diseases, endocrine/metabolic/blood/immune diseases, hemoglobinopathies, oral disorders, SIDS, urinary diseases |

| Respiratory infections and tuberculosis |

| lower respiratory infect, otitis media, tuberculosis, upper respiratory infect |

| Sense organ diseases |

| Age-related hearing loss, blindness and vision impairment, other sense organ diseases |

| Skin diseases |

| Acne vulgaris, alopecia areata, bacterial skin disease, decubitus ulcer, dermatitis, fungal skin diseases, other skin diseases, pruritus, psoriasis, scrabies, urticaria, viral skin diseases |

| Transport injuries |

| Other transport injuries, road injuries |

| Unintentional injuries |

| Adverse medical treatment, animal contact, drowning, environ heat and cold, falls, fire and heat, foreign body, mechanical forces, nature disaster, other unintentional, poisonings |

Self-generated table based on the Global Burden of Diseases Classification that is publicly available and was published online by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Washington School of Medicine. 21 (GBD main categories (and their associated subcategories) we did not include were self-harm and interpersonal violence, substance use disorders, mental disorders, and sexually transmitted diseases).

Comparisons have been found on all conditions in italics.

Inclusion criteria were full-text epidemiologic studies (cross-sectional or cohort studies) in English or German published between 1 January 2000 and 27 February 2021 that compared lesbian-identified (lesbian) and/or bisexual-identified (bisexual) women or SMW (lesbian- and bisexual-identified aggregated) to heterosexual/straight-identified (heterosexual) women regarding prevalence of at least one diagnosed (self-reported or examined) health condition according to the GBD classification. Given the steadily evolving nature of research on sexual minority individuals, the year 2000 was chosen as a start date to be in alignment with the current century. Age cutoff was ⩾18 years, as our focus was on sexual minority adults. Furthermore, this aligns with most representative health surveys which conventionally employ the same age cutoff of ⩾18 years.

In those studies that reported gender identity, we focused on cisgender women only since transgender individuals face unique health risks irrespective of their sexual identity, and we sought to minimize confounding. To maximize precision, we considered different dimensions of sexual orientation (identity/attraction/behavior) as distinct units of analysis. Thus, we focused on one of them, that is, identity, since sexual identity was considered particularly relevant in the framework of minority stress 1 as a main predictor of physical health disparities. Previous research also confirmed that sexual identity (vs attraction and behavior) was the measure perceived to be most closely related to discrimination and stigma. 22 Hence, we excluded studies that defined sexual orientation via sexual attraction and/or behavior only. We furthermore excluded studies that consisted of HIV-samples only (to avoid bias, results will be reported elsewhere) and studies that reported only risk factors for the diseases in question.

Database search and screening procedure

An extensive database search in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, CINAHL, and Web of Science (WOS), covering publications released January 2000 to February 2021 was conducted by an information specialist (IM). It included all relevant health conditions individually as well as relevant MeSH terms. The detailed search string is provided in Supplementary Appendix SA1. All studies found were uploaded into the systematic review software Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for abstract screening and full-text screening, which was conducted by two reviewers each: all studies were screened by reviewer L.H. (abstracts and full texts) and screened again by another reviewer A.-K.F., E.L. or K.E. (abstracts) and E.L. (all full texts). Throughout screening process, disagreements or uncertainties on study eligibility were resolved through discussion of at least two reviewers.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted by one review author (L.H., K.E., M.N.) using extraction sheets in Excel (V. 16.66.1), checked afterwards by another (L.H., K.E., M.N.), and then double-checked by a third review author (K.E., M.N.). Extracted information included sampling method (including weighting details), dates of data collection, sample sizes, age range, assessment of sexual identity, assessment of health conditions, and variables adjusted for.

Regarding comparative statistics, we extracted data from all studies that reported either odds ratios (OR) or absolute numbers or percentages of prevalence (to approximate ORs ourselves). If neither ORs nor absolute numbers were reported or if rounding errors were to be expected (when calculating ORs from percentages), we requested primary data from the respective author(s).

For studies with multiple options for data extraction (e.g. OR and percentages given), the following hierarchical order was applied for extracting ORs: (1) copied OR from article, (2) calculated OR from absolute numbers copied from article, (3) calculated OR from received primary data (author-request), (4) calculated OR from weighted percentages, and (5) calculated OR from unweighted percentages. Regarding percentages, we reported weighted percentages when available and unweighted otherwise. In addition, if available, adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were extracted. For articles that reported more than one AOR, we selected those that adjusted for the highest number of demographic variables.

In cases of overlapping sample sources and overlapping data collection dates in two or more articles, we checked whether additional information according to predetermined criteria was given. These criteria, that qualified comparisons for keeping them, were: if they included (1) a health condition (assessed in years) not reported in any other study, (2) numbers for lesbian and bisexual women separately (in contrast to SMW aggregated only), and (3) AORs (in contrast to studies with no or less specified AORs).

Statistical analysis/meta-analysis

Whenever we could extract data from at least two non-overlapping studies per health condition, we conducted a meta-analysis on the respective condition. In meta-analyses, only weighted data were included. In case of overlapping sample sources and overlapping dates of data collection, the larger sample was pivotal for inclusion in meta-analysis (if two or more smaller samples collected in consecutive years cumulatively constituted the largest sample, those samples were included). Since the AORs of the studies did not adjust for the same variables (and thus were less comparable), we conducted meta-analyses on ORs using Review Manager 5.4. 23 As we expected some heterogeneity in the study designs and samples, random-effects models, applying the Mantel–Haenszel method, were calculated. Tests for subgroup differences (lesbian, bisexual, and SMW) were run. Results were considered significant, when p < 0.05 and standard thresholds were applied to assess heterogeneity (I2). 24 The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for cohort studies 25 was used to assess quality of the studies.

Results

General findings and description of included studies

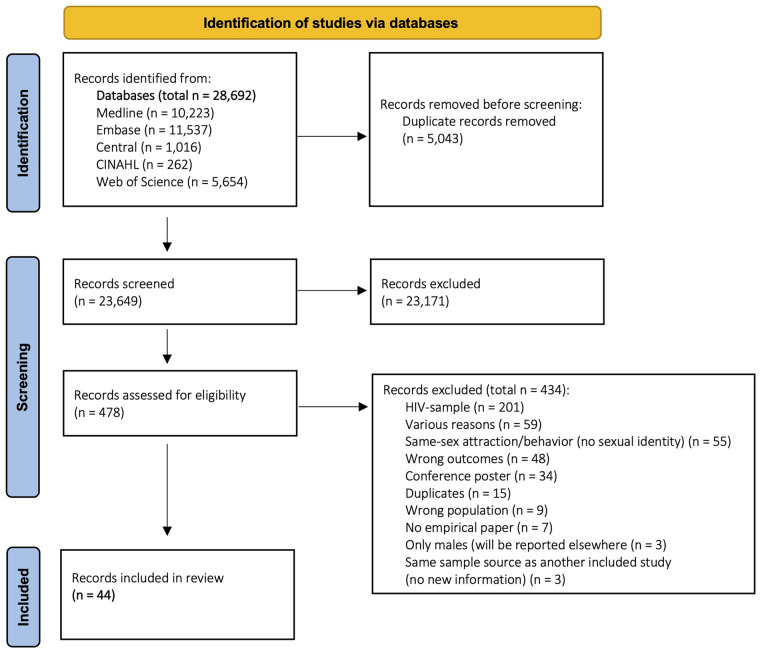

The database search yielded a total of 28,692 references (Figure 1, flow chart). Of those, 5043 were duplicates and removed immediately; titles and abstracts of 23,649 references were screened (title and abstract screening), and of those, 478 were furtherly reviewed (full-text screening). We requested data from 39 authors. Almost half of them (n = 17) replied: 12 authors stated that they no longer had access to the data or that data were no longer available,9,26 –36 and five authors sent data.37–41 Finally, 44 studies were included.9,13,26,28,31,36 –39,41 –74 The vast majority (39/44) derived from large national (or regional) representative health surveys9,13,28,31,36 –39,41 –47,49,50,53 –73 and the remaining (5/44) were single cross-sectional or cohort studies.26,48,51,52,74 The included studies comprise data from four different countries (the United States (n = 39), Australia (n = 2), the United Kingdom (n = 2), Belgium (n = 1)). Total sample sizes ranged between N = 84 74 and N = 12,640,900 41 (weighted estimates); sample size ranges of sexual identity subgroups were: n = 38 39 to n = 194,100 41 for lesbian women, n = 36 50 to n = 314,800 41 for bisexual women, n = 86 66 to n = 2,822 54 for SMW, and n = 42 74 to n = 12,132,000 41 for heterosexual women.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Information on the study sources, dates of data collection, and the sample size of each study are displayed in Table 2. Detailed descriptive information on each study is provided in Supplementary Table S1. There was one study that reported data on cisgender and transgender individuals separately. 47 However, a considerable number of the included studies discussed not having information on gender identity as a limitation.28,36,39,41,49,53,58 –61,66,73 In most cases, this was because publicly available data from the statewide or regional health surveys did not include information on gender identity (assessment).

Table 2.

Study overview: included studies were study source, dates of data collection, and total sample size.

| Code | Study source | Dates of data collection | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cochran and Mays 9 | CHIS, CA, USA | October 2004 to February 2005 | N = 1144, het.: 1058, les.: 48, bi.: 38 |

| Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 13 | Washington BRFSS, USA | 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2010 | N = 58,319, het.: 57,466, SMW: 853 |

| Agrawal et al. 26 | Single cohort study, UK | November 2001 to January 2003 | N = 618, het.: 364, les.: 254 |

| Boehmer et al. 28 | CHIS, CA, USA | 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007 | N = 93,242, het.: 90,608, les.: 1265, bi.: 1369 |

| Caceres et al. 31 | NHANES, USA | 2001–2012 | N = 7503, het.: 7157, SMW: 346 |

| Operario et al. 36 | NHANES, USA | 2001–2010 | N = 5827, het.: 5450, SMW: 377 |

| Garland-Forshee et al. 37 | Oregon BRFSS, USA | 2005–2008 | N = 26,271, het.: 25,602, les.: 347, bi.: 322 |

| McNair et al. 38 | ALSWH, Australia | 2003 | N = 8122, het.: 7959, les.: 63, bi.: 100 |

| Schwartz et al. 39 | NHANES, USA | 2009–2014 | N = 3102, het.: 2950, les.: 38, bi.: 114 |

| Wolstein et al. 41 | CHIS, CA, USA | 2011–2014 | N = 12,640,900, het.: 12,132,000, les.: 194,100, bi.: 314,800 |

| Beach et al. 42 | BRFSS, states including SOM, USA | 2014 | N = 85,939, het.: 83,903, les.: 779, bi.: 1,257 |

| Blosnich et al. 43 | BRFSS, states including SOM, USA | 2010 | N = 52,705, het.: 51,639, les.: 615, bi.: 451 |

| Boehmer et al. 44 | CHIS, CA, USA | 2001, 2003, 2005 | N = 71,112, het.: 69,078, les.: 918, bi.: 1,116 |

| Brown et al. 45 | ALSWH, Australia | 2002, 2005, 2008, 2011 | N = 10,451, het.: 10,200, SMW: 251 |

| Clark et al. 46 | Add Health, USA | 2008, 2009 | N = 5938, het.: 5,713, les.: 71, bi.: 154 |

| Dai and Hao 47 | BRFSS, USA | 2014 | N = 85,739, het.: 83,729 les.: 771, bi.:1,239 |

| De Sutter et al. 48 | Single cohort study, Belgium | January 2002 to June 2006 | N = 311, het.: 161, les.: 150 |

| Diamant and Wold 49 | LACHS, CA, USA | September 1999 to December 1999 | N = 4135, het.: 4,023, les.: 43, bi.: 69 |

| Diamant et al. 50 | LACHS, CA, USA | April 1997 to July 1997 | N = 4697, het.: 4610, les.: 51, bi.: 36 |

| Dibble et al. 51 | Single cross-sectional study, USA | 1999–2002 | N = 381, het.: 278, les.: 103 |

| Dibble et al. 52 | Single cohort study, USA | 1995–1997 | N = 649, het.: 488, les.: 161 |

| Dilley et al. 53 | Washington BRFSS, USA | 2003–2006 | N = 48,655, het.: 47,505, les.: 589, bi.: 561 |

| Eliason et al. 54 | CHIS, CA, USA | 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011–2012 | N = 100,542, het.: 97,720, SMW: 2822 |

| Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 55 | Washington BRFSS, USA | 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009 | N = 50,191, het.: 49,029, les.: 626, bi.: 536 |

| Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 56 | NHIS, USA | 2013, 2014 | N = 18,921, het.: 18,669, SMW: 252 |

| Gao and Mansh 57 | NHIS, USA | 2013, 2014 | N = 38,063, het.: 37,185, les.: 525, bi.: 353 |

| Gonzales and Henning-Smith 58 | BRFSS, states including SOM, USA | 2014, 2015 | N = 179,203, het.: 174,780, les.: 1718, bi.: 2705 |

| Gonzales and Zinone 59 | NHIS, USA | 2013–2016 | N = 73,153, het.: 71,344, les.: 1029, bi.: 780 |

| Han et al. 60 | NSDUH, USA | 2015–2017 | N = 14,004, het.: 13,708, les.: 173, bi.: 123 |

| Heslin 61 | NHIS, USA | 2013–2018 | N = 100,568, het.: 97,909, SMW: 2659 |

| Hutchcraft et al. 62 | NHIS, USA | 2013–2018 | N = 11,066, het.: 10,830, les.: 141, bi.: 95 |

| Kim and Fredriksen-Goldsen 63 | Washington BRFSS, USA | 2003–2009 | N = 4607, het.: 4506, les.: 41, bi.: 60 |

| Lew et al. 64 | BRFSS, USA | 2014–2015 | N = 136,878, het.: 133,546, les.: 1387, bi.: 1945 |

| Mansh et al. (CHIS) 65 | CHIS, CA, USA | 2001, 2003, 2005 | N = 71,143, het.: 69,109, SMW: 2034 |

| Mansh et al. (NHIS) 65 | NHIS, USA | 2013 | N = 18,457, het.: 18,051, SMW: 406 |

| Matthews and Lee 66 | North Carolina BRFSS, USA | 2011 | N = 6196, het.: 6110, SMW: 86 |

| Patterson and Jabson 67 | NHANES, USA | 2009–2014 | N = 4728, het.: 4440, les.: 63, bi.: 225 |

| Saunders et al. 68 | GPPS, UK | 2011–2012 | N = 445,469, het.: 440,698, les.: 2759, bi.: 2012 |

| Simenson et al. 69 | ESTHER, PA, USA | 2015–2016 | N = 483, het.: 213, les.: 270 |

| Singer et al. 70 | BRFSS, USA | 2014–2018 | N = 499,717, het.: 484,341, les.: 5609, bi.: 9767 |

| Smith et al. 71 | ESTHER, PA, USA | April 2008 to August 2008 | N = 211, het.: 97, les.: 114 |

| Strutz et al. 72 | Add Health, USA | 2008 | N = 5815, het.: 5378, SMW: 437 |

| Williams et al. 73 | NHIS, USA | 2013–2017 | N = 58,230, het.: 57,216, les.: 723, bi.: 291 |

| Zaritsky and Dibble 74 | Single cross-sectional study (subset of Dibble, 2004), USA | 1999–2002 | N = 84, het.: 42, les.: 42 |

het.: heterosexual; les.: lesbian; bi: bisexual; CHIS: California Health Interview Survey; BFRSS: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; ALSWH: Australian Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health; Add Health: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health; LACHS: Los Angeles County Health Survey; NHIS: National Health Interview Survey; NSDUH: National Survey on Drug Use and Health; GPPS: General Practice Patient Survey; ESTHER: Epidemiologic STudy of HEalth Risk in Women; SOM: Sexual Orientation Module.

The 44 included studies contained a total of 369 relevant comparisons (236 ORs + 133 AORs) on 21 different health outcomes assigned to these 12 different main categories (GBD): cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes and chronic kidney diseases, digestive diseases, maternal and neonatal diseases, musculoskeletal disorders, neoplasms, neurological disorders, nutritional deficiencies, other infectious diseases, other non-communicable diseases, and skin diseases (see Supplementary Table S2 for counts of ORs and AORs per category).

We excluded some data on arthritis, 47 asthma, 47 cancer,40,47,56,58,75 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other chronic respiratory conditions, 47 CVD, 76 diabetes,40,47,75 hypertension,40,75 miscarriage, 74 and stroke40,75 since none of the above-mentioned criteria for retaining comparisons ((1)–(4), section “Methods”) applied to them. The predetermined threshold to perform meta-analysis (⩾2 non-overlapping weighted studies on the same health condition) was met for eleven health conditions (in order of appearance): heart attacks,47,55,67 hypertension,13,31,37,38,54,60,66,72,73 stroke,47,73 asthma,37,38,43,54 –56,58,60,66,67 chronic kidney diseases,47,60 diabetes,31,37,38,43,46,52,53,60,64,66,73 arthritis,13,28,37,56,58,67 back pain,9,56 cancer,28,38,45,59,60,67,68,70 headache disorders,9,72 and hepatitis.36,38,60 We did not run meta-analyses, but report results narratively on the combined categories other or one out of multiple cardiovascular13,31,37,43,58,69 and chronic respiratory diseases49,58,60,67,72 since these categories summarize conditions with different pathologies that were not considered similar enough to be combined in a meta-analysis.

Findings on health conditions (alphabetical order)

Results of meta-analyses with significant results are shown in Figures 2–9. Meta-analyses without significant differences are provided in Supplementary Figures S1–S3. All results including those of unweighted studies that were not included in meta-analyses are displayed in Table 3.

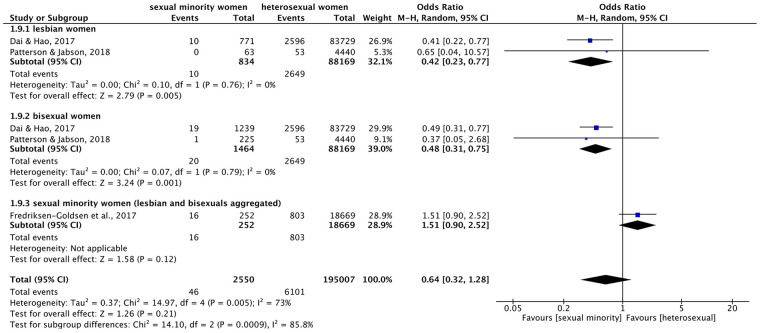

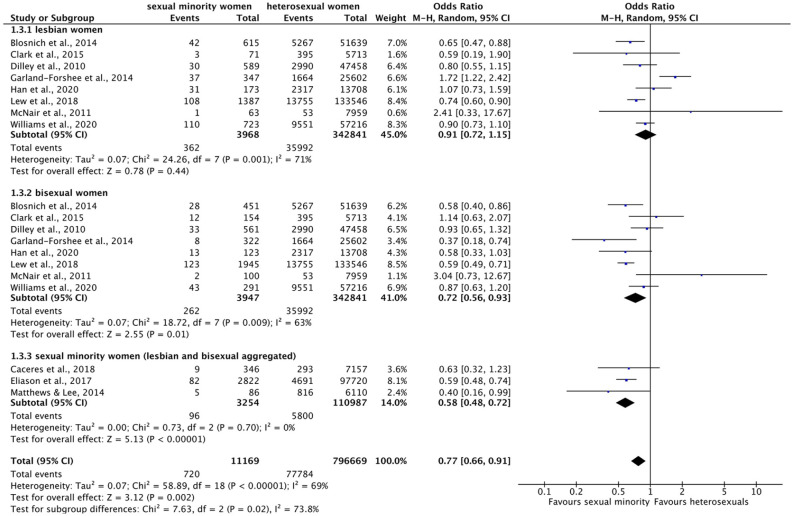

Figure 2.

Forest plot: meta-analysis on heart attacks.

M.-H.: Mantel–Haenszel, CI: confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Forest plot: meta-analysis on hypertension.

M.-H.: Mantel–Haenszel, CI: confidence interval.

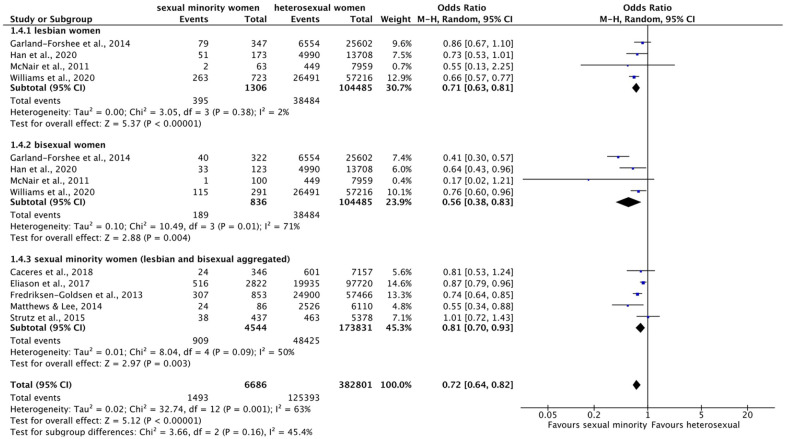

Figure 4.

Forest plot: meta-analysis on asthma.

M.-H.: Mantel–Haenszel, CI: confidence interval.

Figure 5.

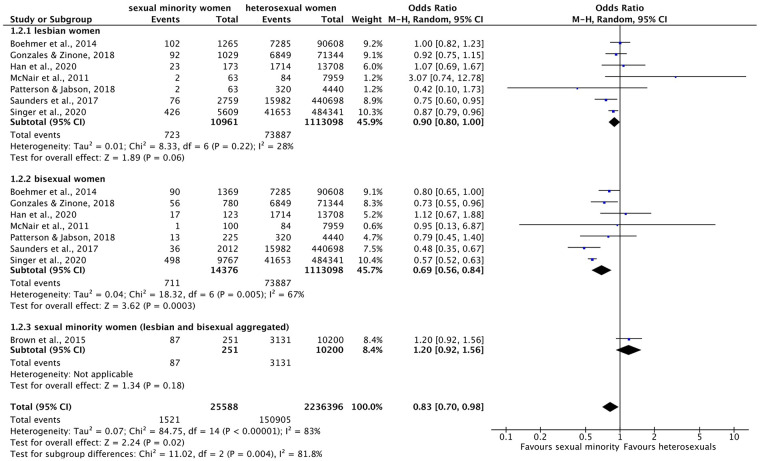

Forest plot: meta-analysis on diabetes.

M.-H.: Mantel–Haenszel, CI: confidence interval.

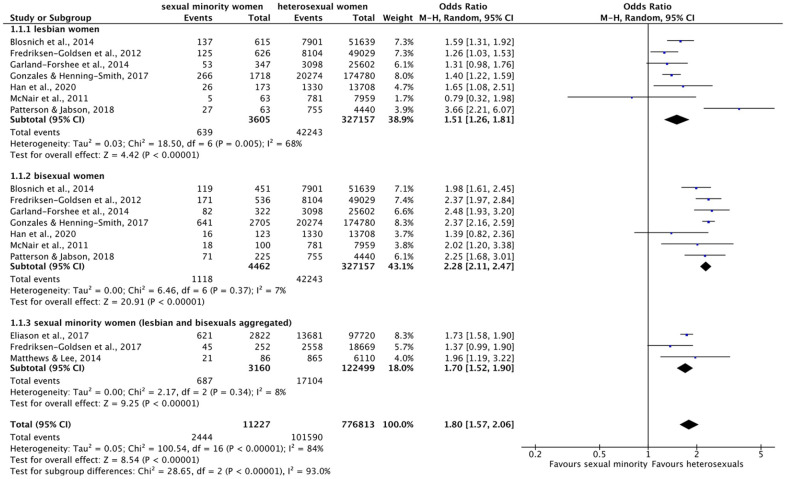

Figure 6.

Forest plot: meta-analysis on back pain.

M.-H.: Mantel–Haenszel, CI: confidence interval.

Figure 7.

Forest plot: meta-analysis on cancer.

M.-H.: Mantel–Haenszel, CI: confidence interval.

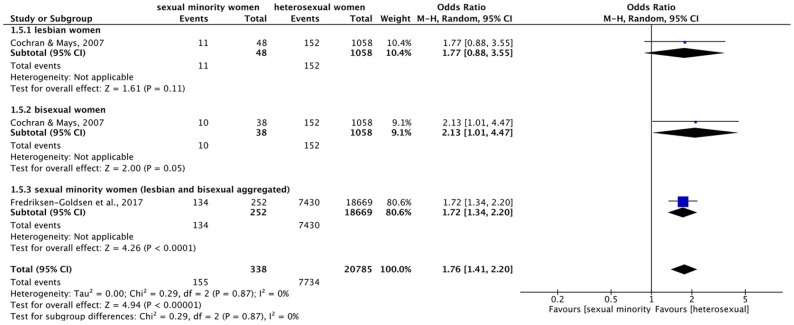

Figure 8.

Forest plot: meta-analysis on headache disorders.

M.-H.: Mantel–Haenszel, CI: confidence interval.

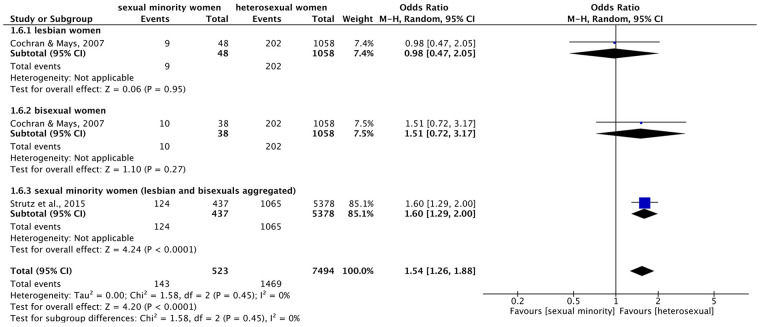

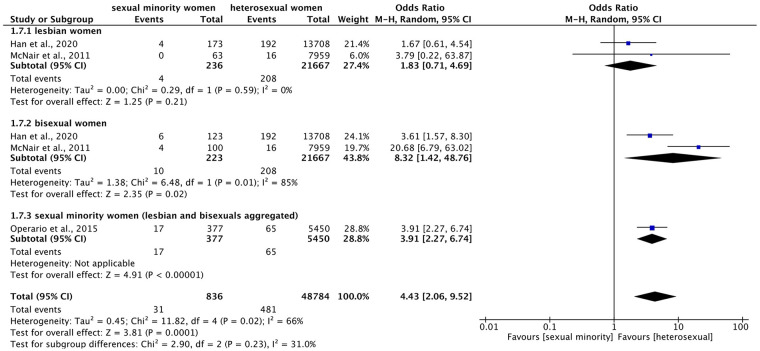

Figure 9.

Forest plot: meta-analysis on hepatitis.

M.-H.: Mantel–Haenszel, CI: confidence interval.

Table 3.

Systematic review results of prevalence, odds ratios, and adjusted odds ratios by sexual identity on physical health diagnoses according to the Global Burden of Disease classification.

| GBD Main category |

GBD subcategory | Author(s), year of publication Health condition as indicated in reference, self-reported unless indicated otherwise |

Prev. (%) | Lesbian women OR (95% CI) AOR (95% CI) |

Bisexual women OR (95% CI) AOR (95% CI) |

SMW OR (95% CI) AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular diseases |

Heart attack (GBD: ischemic heart disease)

(meta-analysis: Figure 2) |

Dai and Hao

47

*Heart attackI,a |

Het: 3.1 Les: 1.3 Bi: 1.5 |

↓ 0.41 (0.22–0.77) | ↓ 0.49 (0.31–0.77) | – |

|

Patterson and Jabson

67

*Heart attackI,a |

Het: 1.2 Les: 0 Bi: 0.5 SMW: 0.4 |

↓ | ↓ 0.37 (0.05–2.68) | ↓ 0.29 (0.04–2.09) ↓ 0.55 (0.10–2.86) |

||

|

Simenson et al.

69

Heart attackII,b |

Het: 1.9 Les: 0.4 |

↓ 0.19 (0.02–1.75) | – | – | ||

| Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 56 *Heart attackI,a | Het: 4.3 SMW: 6.4 |

– | – | ↑ 1.51 (0.90–2.52) ↑ 2.28 (1.58–3.29) |

||

|

Hypertensive heart disease

(meta-analysis: Figure 3) |

Boehmer et al.

28

HBPI,c |

Het: 21.21 Les: 19.02 Bi: 17.57 |

↓ 0.87 (0.76–1.01) ↓ 0.99 (0.77–1.26) |

↓ 0.79 (0.69–0.91) ↑ 1.21 (0.95–1.53) |

– | |

|

Diamant et al.

50

HypertensionII,c |

Het: 17 Les: 8 Bi: 6 |

↓ 0.42 (0.15–1.16) | ↓ 0.29 (0.07–1.20) | – | ||

|

Diamant and Wold

49

HypertensionII,c |

Het: 15.1 Les: 16.3 Bi: 14.5 |

↑ 1.09 (0.48–2.47) ↑ 3.2 (0.4–2.4) |

↓ 0.95 (0.49–1.87) ↑ 3.2 (0.5–2.0) |

– | ||

|

Garland-Forshee et al.

37

*HBPI,a |

Het: 25.6 Les: 22.9 Bi: 12.4 |

↓ 0.86 (0.67–1.10) | ↓ 0.41 (0.30–0.57) | – | ||

|

Han et al.

60

*HBPI,a |

Het: 36.4 Les: 29.5 Bi: 27.2 |

↓ 0.73 (0.53–1.01) | ↓ 0.64 (0.43–0.96) | – | ||

|

McNair et al.

38

*Hypertension (during pregnancy)I,d |

Het: 3.5 Les: 0 Bi: 0 |

↓ | ↓ | – | ||

|

McNair et al.

38

*Hypertension (other than pregnancy)I,d (both types aggregated for meta-analyses) |

Het: 2.1 Les: 3.2 Bi: 1 |

↑ 1.53 (0.37–6.31) | ↓ 0.47 (0.07–3.40) | – | ||

|

Simenson et al.

69

HypertensionII,b |

Het: 28.6 Les: 29.6 |

↑ 1.05 (0.71–1.56) | – | – | ||

|

Williams et al.

73

*HypertensionI,b |

Het: 46.3 Les: 36.4 Bi: 39.5 |

↓ 0.66 (0.57–0.77) | ↓ 0.76 (0.60–0.96) | – | ||

|

Wolstein et al.

41

HypertensionI,d |

Het: 22.56 Les: 21.28 Bi: 18.75 |

↓ 0.93 (0.92–0.94) | ↓ 0.79 (0.78–0.80) | – | ||

|

Caceres et al.

31

*Hypertension, exam.I,e |

Het: 8.4 SMW: 6.8 |

– | – | ↓ 0.79 (0.38–1.62) ↑ 1.12 (0.52–2.41) |

||

|

Caceres et al.

31

Hypertension, sr.I,e |

Het: 23.8 SMW: 18.6 |

– | – | ↓ 0.73 (0.49–1.08) ↓ 0.76 (0.49–1.18) |

||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

13

*HBPI,e |

Het: 43.33 SMW: 36.02 |

– | – | ↓ 0.74 (0.54–1.00) ↓ 0.86 (0.62–1.20) |

||

|

Matthews and Lee

66

*HypertensionI,b |

Het: 33.18 SMW: 21.96 |

– | – |

↓ 0.55 (0.34–0.88)

↔ 1.00 (0.43–2.33) |

||

|

Strutz et al.

72

*HBP/hypertensionI,e |

Het: 8.6 SMW: 8.7 |

– | – | ↑ 1.01 (0.64–1.59) ↓ 0.98 (0.63–1.53) |

||

|

Cochran and Mays

9

HypertensionI,a |

Het: 14.9 Les: 12.6 Bi: 7.4 |

↓ 0.81 (0.34–1.95) ↓ 0.91 (0.35–2.34) |

↓ 0.49 (0.15–1.61) ↓ 0.88 (0.23–3.33) |

– | ||

|

Dilley et al.

53

Hypertension/HBPI,c |

Het: 22.7 Les: 14.7 Bi: 17 |

↓ 0.59 (0.42–0.82)

↔ 1.0 (0.6–1.7) |

↓ 0.70 (0.50–0.96) ↑ 1.6 (1.1–2.5) |

– | ||

|

Eliason et al.

54

*Hypertension (HBP)I,a |

Het: 20.4 SMW: 18.3 |

– | – | ↓ 0.87 (0.79–0.96) | ||

|

Hutchcraft et al.

62

HypertensionI,a |

Het: 30.2 Les: 22.6 Bi: 18.8 |

↓ 0.68 (0.46–1.01) ↓ 0.93 (0.62–1.41) |

↓ 0.54 (0.32–0.90) ↑ 1.41 (0.86–2.3) |

– | ||

|

Patterson

67

HypertensionI,a |

Het: 22.4 Les: 14 Bi: 15.7 SMW: 15.3 |

↓ 0.58 (0.28–1.17) ↓ 0.51 (0.25–1.02) |

↓ 0.64 (0.44–0.92)

↓ 0.87 (0.50–1.48) |

↓ 0.62 (0.45–0.87)

↓ 0.76 (0.50–1.18) |

||

| Other or one out of multiple cardiovascular diseases |

Blosnich et al.

43

CVD symptomsI,a |

Het: 5.8 Les: 5 Bi: 7 |

↓ 0.86 (0.60–1.24) | ↑ 1.24 (0.86–1.78) | – | |

|

Caceres et al.

31

CVD diagnosisI,e |

Het: 3.3 SMW: 2.8 |

– | – | ↓ 0.84 (0.38–1.85) ↓ 0.69 (0.29–1.66) |

||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

13

Cardiovascular diseaseI,e |

Het: 10.71 SMW: 10.51 |

– | – | ↓ 0.98 (0.73–1.31) ↑ 1.37 (1.00–1.86) |

||

|

Garland-Forshee et al.

37

Cardiovascular diseaseI,a |

Het: 6.2 Les: 4 Bi: 1.8 |

↓ 0.64 (0.37–1.09) ↔ 1.0 (0.5–1.9) |

↓ 0.29 (0.13–0.65)

↓ 0.7 (0.2–2.9) |

– | ||

|

Gonzales and Henning-Smith

58

Cardiovascular diseaseI,a |

Het: 5.2 Les: 2.8 Bi: 2.3 |

↓ 0.52 (0.39–0.70) ↓ 0.91 (0.61–1.37) |

↓ 0.43 (0.33–0.55) ↑ 1.02 (0.72–1.44) |

|||

|

Simenson et al.

69

Cardiovascular diseaseII,b |

Het: 4.7 Les: 4.1 |

↓ 0.86 (0.36–2.07) | – | – | ||

| Stroke |

Dai and Hao

47

*StrokeI,a |

Het: 3.1 Les: 3.6 Bi: 3.4 |

↑ 1.18 (0.81–1.72) | ↑ 1.10 (0.80–1.50) | – | |

|

Hutchcraft et al.

62

StrokeI,a |

Het: 2.9 Les: 2.9 Bi: 1.4 |

↓ 0.98 (0.36–2.66) ↑ 2.19 (0.94–5.09) |

↓ 0.36 (0.05–2.56) ↑ 1.16 (0.78–2.84) |

– | ||

|

Simenson et al.

69

StrokeII,b |

Het: 1.4 Les: 0.7 |

↓ 0.52 (0.09–3.15) | – | – | ||

|

Williams et al.

73

*CVA/strokeI,b |

Het: 4.9 Les: 5.5 Bi: 4.1 |

↑ 1.14 (0.83–1.57) | ↓ 0.84 (0.47–1.49) | – | ||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

56

StrokeI,a |

Het: 5.1 SMW: 6.8 |

– | – | ↑ 1.35 (0.82–2.21) ↑ 2.12 (1.57–2.87) |

||

| Chronic respiratory diseases |

Asthma

(meta-analysis: Figure 4) |

Blosnich et al.

43

*AsthmaI,a |

Het: 15.3 Les: 22.2 Bi: 26.4 |

↑ 1.59 (1.31–1.92)

↑ 1.50 (1.04–2.16) |

↑ 1.98 (1.61–2.45)

↑ 1.68 (1.07–2.63) |

– |

|

Boehmer et al.

28

AsthmaI,c |

Het: 13.67 Les: 20.78 Bi: 21.46 |

↑ 1.66 (1.45–1.90)

↑ 1.41 (1.14–1.73) |

↑ 1.73 (1.52–1.97)

↑ 1.52 (1.24–1.87) |

– | ||

|

Diamant and Wold

49

AsthmaII,c |

Het: 10 Les: 16.3 Bi: 14.5 |

↑ 1.75 (0.77–3.96) ↑ 1.7 (0.7–3.9) |

↑ 1.53 (0.77–3.01) ↑ 1.4 (0.7–2.8) |

– | ||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

55

*AsthmaI,a |

Het: 16.53 Les: 19.92 Bi: 31.88 |

↑ 1.26 (1.03–1.53)

↑ 1.23 |

↑ 2.37 (1.97–2.84)

↑ 2.17 |

– | ||

|

Gao and Mansh

57

AsthmaII,b |

Het: 13.92 Les: 24 Bi: 27.20 |

↑ 1.95 (1.59–2.39)

↑ 1.32 (1.02–1.71) |

↑ 2.31 (1.82–2.92)

↑ 1.65 (1.17–2.32) |

– | ||

|

Garland-Forshee et al.

37

*AsthmaI,a |

Het: 12.1 Les: 15.4 Bi: 25.6 |

↑ 1.31 (0.98–1.76) ↑ 1.2 (0.8–1.9) |

↑ 2.48 (1.93–3.20)

↑ 2.4 (1.5–3.6) |

– | ||

|

Gonzales and Henning-Smith

58

*AsthmaI,a |

Het: 11.6 Les: 15.5 Bi: 23.7 |

↑ 1.40 (1.22–1.59)

↑ 1.33 (1.04–1.72) |

↑ 2.37 (2.16–2.59)

↑ 1.99 (1.65–2.40) |

– | ||

|

Han et al.

60

*AsthmaI,a |

Het: 9.7 Les: 15 Bi: 13.1 |

↑ 1.65 (1.08–2.51) | ↑ 1.39 (0.82–2.36) | – | ||

|

McNair et al.

38

*AsthmaI,d |

Het: 9.8 Les: 7.9 Bi: 18 |

↓ 0.79 (0.32–1.98) | ↑ 2.02 (1.20–3.38) | – | ||

|

Patterson and Jabson

67

*AsthmaI,a |

Het: 17 Les: 43.2 Bi: 31.4 SMW: 34.1 |

↑ 3.66 (2.21–6.07)

↑ 3.19 (1.37–7.47) |

↑ 2.25 (1.68–3.01)

↑ 1.70 (1.12–2.58) |

↑ 2.52 (1.95–3.25)

↑ 1.98 (1.32–2.98) |

||

|

Wolstein et al.

41

AsthmaI,d |

Het: 15.04 Les: 22.96 Bi: 21.69 |

↑ 1.68 (1.67–1.70) | ↑ 1.56 (1.55–1.58) | – | ||

|

Matthews and Lee

66

*AsthmaI,b |

Het: 15.71 SMW: 27.69 | – | – |

↑ 1.96 (1.19–3.22)

↑ 1.94 (0.96–3.92) |

||

|

Cochran and Mays

9

AsthmaI,a |

Het: 8.6 Les: 13.1 Bi: 19.2 |

↑ 1.52 (0.63–3.67) ↑ 1.38 (0.57–3.31) |

↑ 2.40 (1.03–5.60)

↑ 2.00 (0.85–4.70) |

– | ||

|

Dilley et al.

53

AsthmaI,c |

Het: 11.2 Les: 17.7 Bi: 21 |

↑ 1.71 (1.38–2.12)

↑ 1.7 (1.3–2.3) |

↑ 2.10 (1.71–2.58)

↑ 2.0 (1.5–2.6) |

– | ||

| Eliason et al. 54 *Adult AsthmaI,a | Het: 14 SMW: 22 |

– | – | ↑ 1.73 (1.58–1.90) | ||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

13

AsthmaI,e |

Het: 15.89 SMW: 20.57 |

– | – |

↑ 1.37 (1.10–1.70)

↑ 1.20 (0.96–1.49) |

||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

56

*AsthmaI,e |

Het: 13.7 SMW: 18 |

– | – | ↑ 1.37 (0.99–1.90) ↑ 1.28 (1.12–1.53) |

||

|

Hutchcraft et al.

62

AsthmaI,a |

Het: 14.4 Les: 21.6 Bi: 24.7 |

↑ 1.61 (1.07–2.41)

↑ 1.45 (0.89–2.37) |

↑ 1.90 (1.18–3.04)

↑ 1.40 (0.74–2.66) |

– | ||

|

Kim and Fredriksen-Goldsen

63

AsthmaI,a |

Het: 12.02 Les: 45.6 Bi: 27.9 |

↑ 6.32 (3.40–11.75) | ↑ 2.89 (1.64–5.11) | – | ||

| COPD |

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

56

COPDI,a |

Het: 6 SMW: 5.2 |

– | – | ↓ 0.85 (0.49–1.49) ↑ 1.08 (0.83–1.41 ) |

|

|

Hutchcraft et al.

62

COPDI,a |

Het: 3.3 Les: 2.7 Bi: 2 |

↓ 0.86 (0.32–2.33) ↑ 1.98 (1.09–3.56) |

↓ 0.63 (0.15–2.57) ↑ 1.44 (0.64–3.25) |

– | ||

|

Simenson et al.

69

COPDII,b |

Het: 3.8 Les: 2.6 |

↓ 0.68 (0.24–1.91) | – | – | ||

|

Williams et al.

73

COPDI,b |

Het: 5.6 Les: 5.5 Bi: 5.8 |

↓ 0.98 (0.71–1.36) | ↑ 1.04 (0.64–1.70) | – | ||

| Other or one out of multiple chronic respiratory diseases |

Diamant and Wold

49

Chronic respiratory con.II,c |

Het: 4.6 Les: 4.7 Bi: 8.7 |

↑ 1.01 (0.24–4.22) ↓ 0.8 (0.2–3.5) |

↑ 1.98 (0.84–4.62) ↑ 1.6 (0.7–3.9) |

– | |

|

Gonzales and Henning-Smith

58

COPD (and others)I,a |

Het: 7.5 Les: 8.1 Bi: 8.6 |

↑ 1.09 (0.91–1.29) ↑ 1.54 (1.11–2.16) |

↑ 1.16 (1.02–1.33)

↑ 1.83 (1.40–2.39) |

– | ||

|

Han et al.

60

Bronchitis/COPDI,a |

Het: 8.9 Les: 15.6 Bi: 12 |

↑ 1.89 (1.25–2.87) | ↑ 1.42 (0.83–2.45) | – | ||

|

Patterson and Jabson

67

Chronic bronchitisI,a |

Het: 6.6 Les: 18 Bi: 8.2 SMW: 10.4 |

↑ 2.99 (1.55–5.80)

↑ 2.64 (1.21–5.72) |

↑ 1.31 (0.80–2.12) ↑ 1.05 (0.60–1.81) |

↑ 1.65 (1.11–2.45)

↑ 1.38 (0.92–2.06) |

||

|

Strutz et al.

72

Asthma/chronic bronchitis/emphysemaI,e |

Het: 16.5 SMW: 24.5 |

– | – |

↑ 1.64 (1.17–2.31)

↑ 1.54 (1.10–2.16) |

||

| Diabetes and chronic kidney diseases | Chronic kidney diseases |

Dai and Hao

47

*Kidney diseaseI,a |

Het: 3 Les: 1.8 Bi: 2.9 |

↓ 0.60 (0.35–1.02) | ↓ 0.97 (0.69–1.35) | – |

|

Diamant et al.

50

Kidney diseaseII,c |

Het: 1 Les: 2 Bi: 3 |

↑ 1.98 (0.27–14.67) | ↑ 2.83 (0.38–21.13) | – | ||

|

Han et al.

60

*Kidney diseaseI,a |

Het: 3.5 Les: 3.1 Bi: 3.7 |

↓ 0.82 (0.34–2.01) | ↑ 1.17 (0.48–2.87) | – | ||

|

Diabetes

(meta-analysis: Figure 5) |

Blosnich et al.

43

*DiabetesI,a |

Het: 10.2 Les: 6.8 Bi: 6.1 |

↓ 0.65 (0.47–0.88) |

↓ 0.58 (0.40–0.86)

↓ 0.75 (0.44–1.29) |

– | |

|

Clark et al.

46

*Diabetes, exam./sr./medI,b |

Het: 6 Les: 1.9 Bi: 6.8 |

↓ 0.59 (0.19–1.90) | ↑ 1.14 (0.63–2.07) | – | ||

|

Diamant et al.

50

DiabetesII,c |

Het: 6 Les: 2 Bi: 14 |

↓ 0.31 (0.04–2.27) | ↑ 2.52 (0.97–6.54) | – | ||

| Diamant and Wold 49 DiabetesII,c | Het: 5.2 Les: 11.6 Bi: 4.4 |

↑ 2.40 (0.94–6.16) ↑ 2.4 (0.9–6.6) |

↓ 0.83 (0.26–2.66) ↑ 3.2 (0.3–3.2) |

– | ||

|

Dilley et al.

53

*Diabetes (ex. Pred. and GD)I,c |

Het: 6.3 Les: 5.1 Bi: 5.8 |

↓ 0.80 (0.55–1.15) ↑ 1.3 (0.8–2.0) |

↓ 0.93 (0.65–1.32) ↑ 1.8 (1.1–2.8) |

– | ||

|

Garland-Forshee et al.

37

*DiabetesI,a |

Het: 6.5 Les: 10.8 Bi: 2.4 |

↑ 1.72 (1.22–2.42)

↑ 2.2 (0.6–7.8) |

↓ 0.37 (0.18–0.74)

↓ 0.8 (0.4–1.6) |

– | ||

|

Han et al.

60

*DiabetesI,a |

Het: 16.9 Les: 18.2 Bi: 10.9 |

↑ 1.07 (0.73–1.59) | ↓ 0.58 (0.33–1.03) | – | ||

|

Lew et al.

64

*DiabetesI,a |

Het: 10.3 Les: 7.8 Bi: 6.3 |

↓ 0.74 (0.60–0.90)

↓ 0.97 (0.67–1.41) |

↓ 0.59 (0.49–0.71)

↓ 0.81 (0.60–1.08) |

– | ||

|

McNair et al.

38

*Diabetes (type 1)I,d |

Het: 0.3 Les: 0 Bi: 1 |

↓ | ↑ 3.08 (0.41–22.94) | – | ||

|

McNair et al.

38

*Diabetes (type 2)I,d (type 1 and 2 aggregated for meta-analyses) |

Het: 0.3 Les: 1.6 Bi: 1 |

↑ 4.74 (0.63–35.42) | ↑ 2.97 (0.40–22.05) | – | ||

|

Simenson et al.

69

DiabetesII,b |

Het: 8.5 Les: 9.3 |

↑ 1.11 (0.59–2.08) | – | – | ||

|

Williams et al.

73

*DiabetesI,b |

Het: 16.7 Les: 15.2 Bi: 14.8 |

↓ 0.90 (0.73–1.10) | ↓ 0.87 (0.63–1.20) | – | ||

|

Caceres et al.

31

*Diabetes, exam.I,e |

Het: 4.1 SMW: 2.7 |

– | – | ↓ 0.64 (0.28–1.50) ↓ 0.90 (0.35–2.31) |

||

|

Caceres et al.

31

Diabetes, sr.I,e |

Het: 5.3 SMW: 6.5 |

– | – | ↑ 1.25 (0.68–2.28) ↑ 1.82 (0.89–3.72) |

||

|

Eliason et al.

54

*Diabetes (type 1 or 2)I,a |

Het: 4.9 SMW: 2.9 |

– | – | ↓ 0.59 (0.48–0.74) | ||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

56

DiabetesI,a |

Het: 15.9 SMW: 10.6 |

– | – |

↓ 0.63 (0.43–0.95)

↓ 0.77 (0.63–0.96) |

||

|

Matthews and Lee

66

*DiabetesI,b |

Het: 11.33 SMW: 4.3 |

– | – |

↓ 0.40 (0.16–0.99)

↓ 0.55 (0.17–1.82) |

||

|

Beach et al.

42

Diabetes (ex. Pred. and GD)I,e |

Het: 10.2 Les: 8.5 Bi: 5.7 |

↓ 0.82 (0.63–1.05) ↑ 1.22 (0.76–1.95) |

↓ 0.53 (0.42–0.68)

↓ 0.88 (0.62–1.26) |

– | ||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

13

Diabetes (ex. Pred. andGD)I,e |

Het: 11.87 SMW: 13.59 |

– | – | ↑ 1.17 (0.91–1.51) ↑ 1.25 (0.96–1.64) |

||

|

Boehmer et al.

28

DiabetesI,c |

Het: 5.71 Les: 4.58 Bi: 4.25 |

↓ 0.79 (0.61–1.03) ↑ 1.07 (0.76–1.50) |

↓ 0.73 (0.56–0.95) ↑ 1.10 (0.79–1.55) |

– | ||

|

Cochran and Mays

9

DiabetesI,a |

Het: 6.9 Les: 2.2 Bi: 1.3 |

↓ 0.29 (0.04–2.11) ↓ 0.41 (0.06–2.95) |

↓ 0.36 (0.05–2.70) ↓ 0.27 (0.02–4.80) |

– | ||

|

Hutchcraft et al.

62

DiabetesI,a |

Het: 9.3 Les: 8.7 Bi: 6.8 |

↓ 0.91 (0.50–1.65) ↓ 0.97 (0.47–2.00) |

↓ 0.66 (0.29–1.51) ↓ 0.73 (0.30–1.74) |

– | ||

|

Patterson and Jabson

67

DiabetesI,a |

Het: 5.9 Les: 3.9 Bi: 3.9 SMW: 3.9 |

↓ 0.52 (0.13–2.15) ↓ 0.79 (0.21–2.91) |

↓ 0.66 (0.34–1.31) ↑ 1.04 (0.45–2.40) |

↓ 0.63 (0.34–1.17) ↓ 0.97 (0.50–1.89) |

||

| Digestive diseases | Cirrhosis |

Han et al.

60

CirrhosisI,a |

Het: 0.4 Les: 0 Bi: 2 |

↓ | ↑ 4.10 (0.99–17.01) | – |

| Maternal and neonatal disorders | Maternal disorders | Dibble et al. 51 Miscarriage (in ever pregnant women)II,b | Het: 24.10 Les: 21.36 |

↓ 0.86 (0.50–1.48) | – | – |

| Dibble et al. 52 Miscarriage (in ever pregnant women)II,b | Het: 78.07 Les: 73.91 |

↓ 0.80 (0.53–1.20) | – | – | ||

| Musculoskeletal disorders | Arthritis (GBD: osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, gout) |

Cochran and Mays

9

ArthritisI,a |

Het: 21.4 Les: 33.5 Bi: 17.7 |

↑ 1.84 (0.99–3.41) ↑ 2.02 (1.00–4.08) |

↓ 0.83 (0.36–1.91) ↑ 1.40 (0.55–3.60) |

– |

|

Boehmer et al.

28

*ArthritisI,c |

Het: 18.1 Les: 25.2 Bi: 17.64 |

↑ 1.53 (1.34–1.73)

↑ 1.46 (1.05–2.03) |

↓ 0.97 (0.84–1.11) ↑ 1.45 (1.09–1.93) |

– | ||

|

Garland-Forshee et al.

37

*ArthritisI,a |

Het: 31.4 Les: 42.9 Bi: 21.4 |

↑ 1.64 (1.33–2.04)

↑ 2.0 (1.2–3.3) |

↓ 0.59 (0.46–0.78)

↑ 1.4 (0.8–2.6) |

– | ||

|

Diamant and Wold

49

ArthritisII,c |

Het: 14.7 Les: 23.3 Bi: 10.1 |

↑ 1.76 (0.86–3.59) ↑ 1.7 (0.8–3.7) |

↓ 0.66 (0.30–1.44) ↓ 0.6 (0.3–1.4) |

– | ||

|

Diamant et al.

50

ArthritisII,c |

Het: 21 Les: 31 Bi: 17 |

↑ 1.72 (0.95–3.12) | ↓ 0.75 (0.31–1.81) | – | ||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

55

Arthritis (several forms)I,a |

Het: 30.72 Les: 33.67 Bi: 22.57 |

↑ 1.15 (0.97–1.35) ↑ 1.55 |

↓ 0.66 (0.54–0.81)

↑ 1.54 |

– | ||

|

Gonzales and Henning-Smith

58

*Arthritis (several forms)I,a |

Het: 31 Les: 29.5 Bi: 20.8 |

↓ 0.93 (0.84–1.03) ↑ 1.58 (1.30–1.91) |

↓ 0.59 (0.53–0.64) ↑ 1.49 (1.24–1.80) |

– | ||

|

Kim and Fredriksen-Goldsen

63

ArthritisI,a |

Het: 12.44 Les: 29.36 Bi: 36.74 |

↑ 2.91 (1.48–5.74) | ↑ 4.07 (2.39–6.93) | – | ||

|

Patterson and Jabson

67

*ArthritisI,a |

Het: 19 Les: 28.5 Bi: 19.3 SMW: 21.4 |

↑ 1.70 (0.98–2.96) ↑ 1.88 (0.93–3.82) |

↑ 1.01 (0.72–1.42) ↑ 1.76 (1.00–3.07) |

↑ 1.17 (0.87–1.56) ↑ 1.79 (1.12–2.86) |

||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

13

*ArthritisI,e |

Het: 52.24 SMW: 53.7 |

– | – | ↑ 1.06 (0.83–1.36) ↑ 1.29 (0.99–1.67) |

||

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

56

*ArthritisI,a |

Het: 44.7 SMW: 50.3 |

– | – | ↑ 1.26 (0.98–1.61) ↑ 1.57 (1.32–1.88) |

||

|

Back pain (GBD: low back pain and neck pain)

(meta-analysis: Figure 6) |

Cochran and Mays

9

*Back problemsI,a |

Het: 14.4 Les: 23.3 Bi: 26.5 |

↑ 1.77 (0.88–3.55) ↑ 1.66 (0.80–3.43) |

↑ 2.13 (1.01–4.47)

↑ 2.39 (1.10–5.20) |

– | |

|

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al.

56

*Low back pain/neck painI,a |

Het: 39.8 SMW: 53 |

– | – |

↑ 1.72 (1.34–2.20)

↑ 1.78 (1.46–2.17) |

||

| Neoplasms |

All kinds of cancer (aggregated)

(meta-analysis: Figure 7) |

Boehmer et al.

28

*Adult cancerI,c |

Het: 8.04 Les: 9.06 Bi: 6.56 |

↔ 1.00 (0.82–1.23) ↑ 1.09 (0.81–1.47) |

↓ 0.80 (0.65–1.00) ↑ 1.14 (0.80–1.61) |

– |

|

Gonzales and Zinone

59

*CancerI,e |

Het: 9.6 Les: 8.9 Bi: 7.2 |

↓ 0.93 (0.72–1.19) ↑ 1.18 (0.90–1.55) |

↓ 0.74 (0.52–1.04) ↑ 1.70 (1.16–2.48) |

– | ||

|

Han et al.

60

*CancerI,a |

Het: 12.5 Les: 13.2 Bi: 13.9 |

↑ 1.07 (0.69–1.67) | ↑ 1.12 (0.67–1.88) | – | ||

|

McNair et al.

38

*CancerI,d |

Het: 1.1 Les: 3.2 Bi: 1 |

↑ 3.07 (0.74–12.78) | ↓ 0.95 (0.13–6.87) | – | ||

|

Patterson and Jabson

67

*CancerI,a |

Het: 7.2 Les: 2.9 Bi: 5.6 SMW: 5 |

↓ 0.42 (0.10–1.73) ↓ 0.34 (0.09–1.29) |

↓ 0.79 (0.45–1.40) ↑ 1.08 (0.53–2.19) |

↓ 0.66 (0.38–1.14) ↓ 0.84 (0.42–1.67) |

||

|

Saunders et al.

68

*Cancer (5 years)I,b |

Het: 3.63 Les: 2.75 Bi: 1.79 SMW: 2.34 |

↓ 0.75 (0.60–0.95) | ↓ 0.48 (0.35–0.67) |

↓ 0.64 (0.53–0.77)

↑ 1.14 (0.94–1.37) |

||

|

Simenson et al.

69

CancerII,b |

Het: 11.7 Les: 14.1 |

↑ 1.23 (0.72–2.11) | – | – | ||

|

Singer et al.

70

*Cancer (ex. Skin C.)I,c |

Het: 8.6 Les: 7.6 Bi: 5.1 |

↓ 0.87 (0.79–0.96) | ↓ 0.57 (0.52–0.63) | – | ||

|

Singer et al.

70

Skin cancer d.III,e |

Het: 6.7 Les: 6.1 Bi: 4.6 |

↓ 0.68 (0.53–0.87)

↑ 1.01 (0.77–1.33) |

↓ 0.28 (0.23–0.35)

↓ 0.75 (0.60–0.95) |

– | ||

|

Zaritsky and Dibble

74

Breast cancerII,b |

Het: 14.6 Les: 29.3 |

↑ 2.41 (0.81–7.23) | – | – | ||

|

Brown et al.

45

*Cancer diagnosis (3 years)I,e |

Het: 30.7 SMW: 34.7 |

– | – | ↑ 1.20 (0.92–1.56) | ||

|

Boehmer et al.

44

Cancer (any kind)I,b |

Het: 7.71 Les: 8.59 Bi: 6.04 |

↔ 1.00 (0.81–1.24) ↑ 1.07 (0.79–1.44) |

↓ 0.67 (0.53–0.84)

↑ 1.11 (0.78–1.57) |

– | ||

|

Cochran and Mays

9

Cancer diagnosis (3 years)I,e |

Het: 2.0 Les: 1.9 Bi: 0 |

↑ 1.05 (0.14–7.98) ↓ 0.76 (0.09–6.48) |

↓ | – | ||

|

Diamant et al.

50

CancerII,c |

Het: 1 Les: 0 Bi: 0 |

↓ | ↓ | – | ||

|

Gonzales and Henning-Smith

58

CancerI,a |

Het: 12.9 Les: 10.4 Bi: 7 |

↓ 0.79 (0.67–0.92) ↑ 1.12 (0.87–1.43) |

↓ 0.51 (0.44–0.59) ↑ 1.25 (0.98–1.59) |

– | ||

|

Mansh et al.

65

All skin cancers (CHIS) III |

Het: 2.6 SMW: 2.3 |

– | – | ↓ 0.84 (0.57–1.23) | ||

|

Mansh et al.

65

All skin cancers (NHIS) III |

Het: 3.1 SMW: 1.6 |

– | – | ↓ 0.53 (0.14–2.03) | ||

|

Williams et al.

73

Breast cancerI,b |

Het: 5 Les: 5.5 Bi: 3.4 |

↑ 1.11 (0.81–1.53) | ↓ 0.68 (0.36–1.27) | – | ||

| Neurological disorders |

Headache disorders

(meta-analysis: Figure 8) |

Heslin

61

Severe headaches/migraines III |

Het: 19.8 SMW: 23.3 |

– | – | ↑ 1.23 (1.12–1.35) |

|

Strutz et al.

72

*Migraine headachesI,e |

Het: 19.8 SMW: 28.4 |

– | – |

↑ 1.61 (1.16–2.24)

↑ 1.53 (1.11–2.11) |

||

|

Cochran and Mays

9

*Migraines or headachesI,a |

Het: 19.1 Les: 18.4 Bi: 26.4 |

↓ 0.98 (0.47–2.05) ↑ 1.22 (0.57–2.62) |

↑ 1.51 (0.72–3.17) ↑ 1.75 (0.82–3.74) |

– | ||

| Nutritional deficiencies | Dietary iron deficiency |

McNair et al.

38

Low ironI,d |

Het: 15.4 Les: 12.7 Bi: 21 |

↓ 0.80 (0.38–1.69) | ↑ 1.46 (0.90–2.38) | – |

| Other infectious diseases |

(Acute) Hepatitis

(meta-analysis: Figure 9) |

Han et al.

60

*Hepatitis B/CI,a |

Het: 1.4 Les: 2.3 Bi: 4.9 |

↑ 1.67 (0.61–4.54) | ↑ 3.61 (1.57–8.30) | – |

|

McNair et al.

38

*Hepatitis B/CI,d |

Het: 0.2 Les: 0 Bi: 4 |

↓ | ↑ 20.68 (6.79–63.02) | – | ||

|

Operario et al.

36

*Hepatitis C antibody, exam.I,a |

Het: 1.2 SMW: 4.6 |

– | – |

↑ 3.91 (2.27–6.74)

↑ 2.99 (1.33–6.73) |

||

| Other non-communicable diseases | Gynecological diseases |

Agrawal et al.

26

PCOS, exam.II,c |

Het: 14 Les: 38 |

↑ 3.79 (2.57–5.60) | – | – |

|

Agrawal et al.

26

FibroidsII,c |

Het: 6.8 Les: 5.6 |

↓ 0.79 (0.40–1.55) | – | – | ||

|

Agrawal et al.

26

EndometriosisII,c |

Het: 3.39 Les: 3.65 |

↑ 1.08 (0.45–2.60) | – | – | ||

|

McNair et al.

38

EndometriosisI,d |

Het: 3.4 Les: 1.6 Bi: 2 |

↓ 0.46 (0.06–3.35) | ↓ 0.59 (0.14–2.39) | – | ||

|

DeSutter et al.

48

PCOS, exam.II,b |

Het: 8.7 Les: 8 |

↓ 0.91 (0.41–2.04) | – | – | ||

|

Smith et al.

71

PCOS, exam.I,b |

Het: 4.1 Les: 7.9 |

↑ 1.99 (0.59–6.69) | – | – | ||

| Oral disorders |

Schwartz et al.

39

PeriodontitisII,d |

Het: 28.88 Les: 47.37 Bi: 37.72 |

↑ 2.22 (1.17–4.21) | ↑ 1.49 (1.01–2.20) | – | |

| Urinary diseases |

McNair et al.

38

Urinary tract infectionsI,d |

Het: 17.7 Les: 7.9 Bi: 28 |

↓ 0.40 (0.16–1.00) | ↑ 1.81 (1.16–2.81) | – | |

| Skin and subcutaneous diseases | Acne vulgaris |

Agrawal et al.

26

AcneII,c |

Het: 9.8 Les: 30 |

↑ 3.89 (2.51–6.02) | – | – |

GBD: Global Burden of Disease; Prev.: prevalence; OR: odds ratio; AOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; Het: heterosexual-identified women; Les: lesbian-identified women; Bi: bisexual-identified women; SMW: sexual minority women (bisexual- and lesbian-identified women aggregated); CVD: cardiovascular disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Pred.: prediabetes; CHIS: California Health Interview; NHIS: National Health Interview Survey; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; exam.: examinated; BFRSS: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; HANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

OR copied from article.

OR calculated from absolute numbers copied from article.

OR calculated from received primary data (author-request).

OR calculated from weighted percentages.

OR calculated from unweighted percentages.

Weighted percentage.

Unweighted percentage.

Age-standardized percentage.

Included in meta-analysis.

Significant differences (ORs, AORs) in bold letters. Hypertensive heart diseases: partial overlaps in: CHIS: Boehmer et al., 28 years: 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, Cochran and Mays, 9 years: 2004, 2005, Eliason et al., 54 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011–2012, and Wolstein et al., 41 years: 2011–2014; NHANES: Caceres et al., 31 years: 2001–2012 and Patterson and Jabson, 67 years: 2009–2014; NHIS: Hutchcraft et al., 62 years: 2013–2018 (subsample of breast cancer patients), and Williams et al., 73 years: 13–17; W.-BRFSS: Dilley et al., 53 years: 2003–2006 and Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 13 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2010; meta-analysis on hypertension: ORs included in meta-analysis with minor deviations due to calculation from reported percentages of original papers in the following cases: Caceres et al., 31 Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 13 and Strutz et al. 72

Other or one out of multiple cardiovascular diseases: partial overlaps in: BFRSS: Blosnich et al., 43 years: 2010 & W.-BFRSS: Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 13 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2010.

Stroke: partial overlaps in: NHIS: Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 56 years: 2013–2014, Hutchcraft et al., 62 years: 2013–2018 (subsample of breast cancer patients), and Williams et al., 73 years: 2013–2017.

Asthma: partial overlaps in: BRFSS: Blosnich et al., 43 years: 10 and W.-BRFSS: Dilley et al., 53 years: 2003–2006, Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 55 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 13 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2010 and Kim & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 63 years: 2003–2009 (Hispanic women only); CHIS: Boehmer et al., 28 years: 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, Cochran and Mays, 9 years: 2004, 2005, Eliason et al., 54 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011–2012, and Wolstein et al., 41 years: 2011–2014; NHIS: Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 56 years: 2013, 2014 (weighted), Gao and Mansh, 57 years: 2013, 2014 (unweighted), and Hutchcraft et al., 62 years: 2013–2018 (subsample of breast cancer patients).

COPD: partial overlaps in NHIS: Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 56 years: 2013, 2014, Hutchcraft et al., 62 years: 2013–2018 (subsample of breast cancer patients), and Williams et al., 73 2013–2017.

Diabetes: partial overlaps in: BRFSS: Beach et al., 42 years: 14 and Lew et al., 64 years: 2014, 2015, Blosnich et al., 43 years: 2010 and W.-BRFSS: Dilley et al., 53 years: 2003–2006 and Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 13 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2010; CHIS: Boehmer et al., 28 years: 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, Cochran & Mays, 9 years: 2004, 2005 and Eliason et al., 54 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011–2012; NHANES: Caceres et al., 31 years: 2001–2012 and Patterson and Jabson, 67 years: 2009–2014; NHIS: Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 56 years: 2013, 2014, Hutchcraft et al., 62 years: 2013–2018 (subsample of breast cancer patients) and Williams et al., 73 years: 2013–2017; meta-analysis on Diabetes: ORs included in meta-analysis with minor deviations due to calculation from reported percentages of original papers in the following case: Caceres et al. 31

Arthritis: partial overlaps in: CHIS: Boehmer et al., 28 years: 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007 and Cochran and Mays, 9 years: 2004, 2005 W.-BFRSS: Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 55 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 13 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009 (⩾50 years of age only), and Kim and Fredriksen-Goldsen, 63 years: 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009 (Hispanic women only).

Neoplasms: partial overlaps (all kinds of cancer) in: BRFSS: Gonzales and Henning-Smith, 58 years: 2014–2015 and Singer et al., 70 years: 14–18; CHIS: Boehmer et al., 44 years: 2001, 2003, 2005, Boehmer et al., 28 years: 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, Cochran and Mays, 9 years: 2004, 2005, and Mansh et al., 65 years: 2001–2005; NHIS: Gonzales & Zinone, 59 years: 2013–2016, Mansh et al., 65 years: 13, and Williams et al., 73 years: 13–17; meta-analysis on Neoplasms: ORs included in meta-analysis with minor deviations due to calculation from reported percentages of original papers in the following case: Gonzales and Zinone. 59

Cardiovascular diseases

In terms of heart attacks, meta-analysis (Figure 2) across the subgroups found no significant overall difference of prevalence by sexual identity (OR = 0.64 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.32–1.28), p = 0.21, I2 = 73%). However, the test for subgroup differences reached significance, since on the subgroup level, significant differences were found in both meta-analyses for lesbian and bisexual women separately: lesbian women were approximately 40% (OR = 0.42 (95% CI = 0.23–0.77), p = 0.005, I2 = 0%) and bisexual women about 50% (OR = 0.48 (95% CI = 0.31–0.75), p = 0.001, I2 = 0%) less likely to have suffered a heart attack than heterosexual women. In contrast, the one study that combined lesbian and bisexual women (SMW) did not find a significant difference (OR = 1.51 (95% CI = 0.90–2.52), p = 0.12, one study only). This study included only older adults ⩾50 years, and after adjusting for demographic variables, SMW here were found to be more than twice as likely to have had a heart attack compared to heterosexual women. 56 Heterogeneity was higher in meta-analysis across subgroups than within subgroups.

Meta-analysis on hypertension (Figure 3) across all subgroups showed that lesbian, bisexual, and SMW were approximately 25% less likely to have hypertension than their heterosexual counterparts (OR = 0.72 (95% CI = 0.64–0.82), p < 0.00001, I2 = 63%). The test for subgroup differences was not significant (χ2 = 3.66, degree of freedom (df) = 2, p = 0.16), since prevalence differences were found in all meta-analyses within subgroups: lesbian women were about 30% (OR = 0.71 (95% CI = 0.63–0.81), p < 0.00001, I2 = 2%), bisexual women about 45% (OR = 0.56 (95% CI = 0.38–0.83), p = 0.004, I2 = 71%), and SMW about 20% (OR = 0.81 (95% CI = 0.70–0.93), p < 0.003, I2 = 50%) less likely to have hypertension than heterosexual women. However, one notable result was found in one study that distinguished between hypertension during pregnancy and hypertension other than pregnancy (aggregated in meta-analysis): regarding hypertension other than pregnancy, lesbian women had (non-significantly) higher prevalence ratios than heterosexual women (Table 3). 38 Again, heterogeneity was higher in meta-analysis across subgroups than within subgroups, except for meta-analysis on SMW.

Concerning strokes, meta-analysis (Supplementary Figure S1) across the subgroups found no significant overall difference (OR = 1.10 (95% CI = 0.92–1.32), p = 0.31, I2 = 0%). This also applied for both meta-analyses on lesbian and bisexual women separately. However, similar to heart attacks, one study (of only older adults ⩾50 years) found SMW to be more than twice as likely to suffer a stroke after adjusting for demographic variables. 56 Heterogeneity was I2 = 0% in meta-analyses on stroke.

Chronic respiratory diseases

Of all conditions included in the systematic review, the most significant differences in prevalence were found for asthma: meta-analysis (Figure 4) revealed a significant overall effect, indicating that across the subgroups, lesbian, bisexual, and SMW were 80% more likely to suffer from asthma than heterosexual women (1.80 (95% CI = 1.57–2.06), p < 0.00001, I2 = 84%). These differences were the largest for bisexual women, who were significantly more than twice as likely to suffer from asthma than heterosexual women (2.28 (95% CI = 2.11–2.47), p < 0.00001, I2 = 7%). Lesbian women were more than 1.5 times as likely to have asthma compared to heterosexual women (1.51 (95% CI = 1.26–1.81), p = 0.005, I2 = 68%). SMW aggregated were about 70% more likely to have asthma than heterosexual women (1.70 (95% CI = 1.52–1.90), p < 0.00001, I2 = 68%). The test for subgroup differences reached significance (χ2 = 28.65, df = 2, p < 0.00001), and overall, heterogeneity was higher in meta-analysis across subgroups than within subgroups. Regarding chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the results were less distinctive: one significant AOR indicated a two times higher prevalence in lesbian women 62 and the other comparisons revealed no significant differences in either direction.56,69,73

In those studies (n = 5) that assessed other or one out of multiple chronic respiratory diseases, results, again, were very consistent: of a total of 18 ratios (ORs and AORs summed), only one AOR was non-significantly lower in lesbian women. 49 All other ratios were >1, with half of them (n = 9) indicating significantly higher odds of chronic respiratory conditions (COPD and others 58 ; bronchitis/COPD 60 ; chronic bronchitis 67 ; asthma/chronic bronchitis/emphysema 72 ) in lesbian, bisexual, or SMW compared to heterosexual women.

Diabetes and chronic kidney diseases

Meta-analysis on chronic kidney diseases (Supplementary Figure S2) found no significant difference by sexual identity (OR = 0.86 (95% CI = 0.67–1.12), p = 0.27, I2 = 0%).

Regarding diabetes, meta-analysis (Figure 5) indicated an overall significant effect across subgroups: overall, SMW were almost 25% less likely to suffer from diabetes than heterosexual women (OR = 0.77 (95% CI = 0.66–0.91), p = 0.002, I2 = 69%). Also, the test for subgroup differences reached significance (χ2 = 7.63, df = 2, p = 0.02): on the subgroup level, significant differences were not found for lesbian (OR = 0.91 (95% CI = 0.72–1.15), p = 0.44), but only for bisexual (OR = 0.72 (95% CI = 0.56–0.93), p = 0.01, I2 = 63%) and SMW compared to heterosexual women (OR = 0.58 (95% CI = 0.48–0.72), p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%). However, when looking at the three studies, that explicitly excluded prediabetes and gestational diabetes13,42,52 (studies have the same sample source (BRFSS), but only minor overlaps in years of data collection (Table 3)), the overall result is less distinctive: with five ratios ⩾1 and five ratios ⩽1 (one significant result each), the findings are equally balanced in either direction. Heterogeneity for diabetes, again, was higher in meta-analysis across subgroups than within subgroups (except for lesbian women).

Digestive diseases

Only one study on digestive diseases (i.e. cirrhosis) was found demonstrating no significant differences by sexual identity. 60

Maternal and neonatal disorders

The two studies (from the same authors) dealing with miscarriages did not find significant differences.50,51

Musculoskeletal disorders

Meta-analysis on arthritis (Supplementary Figure S3) across subgroups found no significant effect (OR = 1.04 (95% CI = 0.82–1.33), p = 0.73, I2 = 96%). Likewise, the meta-analyses within subgroups did not indicate significant differences by sexual identity (lesbian women: OR = 1.38 (95% CI = 0.98–1.94), p = 0.07, I2 = 94%; bisexual women: OR = 0.76 (95% CI = 0.55–1.04), p = 0.09, I2 = 93%). For arthritis, single results diverged considerably, resulting in high heterogeneity. However, two non-significant trends can be observed: overall, prevalence of arthritis tends to be slightly higher in lesbian women than in heterosexual women, and, in contrast, prevalence in bisexual women tends to be slightly lower than in heterosexual women.

Meta-analysis on back pain (Figure 6) found a significant overall effect of higher prevalence of back pain in sexual minority compared to heterosexual women across the subgroups (OR = 1.76 (95% CI = 1.41–2.20), p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%). There were not enough studies to perform meta-analyses within subgroups. However, single results showed that SMW were about twice as likely and bisexual women about 70% as likely to suffer from back pain than heterosexual women. In contrast, the difference between lesbian and heterosexual women was not significant.

Neoplasms

Meta-analysis on cancer (Figure 7) indicated an overall significant effect across subgroups: Overall, SMW were approximately 17% less likely to suffer from cancer than heterosexual women (OR = 0.83 (95% CI = 0.70–0.98), p = 0.02, I2 = 83%). However, this difference was not found for lesbian (OR = 0.90 (95% CI = 0.80–1.00), p = 0.06, I2 = 28%), but only for bisexual women, who were about 30% less likely to have had cancer than heterosexual women (OR = 0.69 (95% CI = 0.56–0.84), p = 0.0003, I2 = 67%). The differences on the subgroup level were also reflected by the significance of the test for subgroup differences (χ2 = 11.02, df = 2, p = 0.0004). There was only one study on SMW, indicating no significant difference (OR = 1.20 (95% CI = 0.92–1.56), p = 0.18). Again, heterogeneity for cancer was the highest in meta-analysis across subgroups compared to within subgroups.

Neurological disorders

Regarding neurological disorders, comparisons were only found for headache disorders: meta-analysis (Figure 8) showed a significant overall effect indicating higher prevalence of headache disorders in sexual minority compared to heterosexual women across subgroups (OR = 1.54 (95% CI = 1.26–1.88), p < 0.0001, I2 = 0%). There were not enough studies to perform meta-analyses within subgroups. However, the two studies comparing SMW and heterosexual women consistently showed significantly higher prevalence ratios for SMW for both severe headaches/migraines 61 and migraine headaches. 72

Nutritional deficiencies

A single study concerned with low iron did not find significant differences. 38

Other infectious diseases

Meta-analysis (Figure 9) on hepatitis revealed a significant overall effect indicating higher prevalence of hepatitis in sexual minority compared to heterosexual women across subgroups (OR = 4.43 (95% CI = 2.06–9.52), p = 0.0001, I2 = 66%). Meta-analysis within subgroups showed that bisexual women were significantly over eight times more likely to suffer from hepatitis than heterosexual women (OR = 8.32 (95% CI = 1.42–48.76), p = 0.02, I2 = 85%). However, for lesbian women, meta-analysis did not show a significant difference (OR = 1.83 (95% CI = 0.71–4.69), p = 0.21, I2 = 0%). Especially with regard to bisexual women, large confidence intervals and high heterogeneity were found.

Other non-communicable diseases

With one exception (one study found that prevalence of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) was about three times higher in lesbian women), 26 no further significant differences were revealed for neither lesbian nor bisexual women compared to heterosexual women concerning gynecological conditions (fibroids, 26 endometriosis,26,38 PCOS).47,71

Regarding oral disorders, we found one study on periodontitis that showed significantly higher prevalence in both lesbian and bisexual compared to heterosexual women. 39 There was one study examining urinary diseases: bisexual women were significantly almost twice as likely as heterosexual women to suffer from urinary tract infections (UTIs), whereas lesbian women were non-significantly less likely to have UTI. 38

Skin and Subcutaneous diseases

The one study that was found on skin and subcutaneous diseases showed that lesbian women were significantly more than three times as likely to have acne as heterosexual women. 26

Risk of bias

Detailed CASP checklist results are provided in Supplementary Table S3. Overall, since 86.67% (39/45) of the included samples rely on large representative health surveys, risk of bias can be considered low.

Comparison of AORs and ORs

Apart from CASP checklist results, one notable result was the considerably greater share of AORs (compared to ORs) indicating higher prevalence in SMW than in heterosexual women across all categories (except for the category diabetes and chronic kidney diseases) (Supplementary Table S2). Particularly large differences (ORs vs AORs) were found for CVDs, musculoskeletal disorders, and neoplasms. This finding suggests that older, financially disadvantaged, and less educated SMW may have been underrepresented in some samples since most common variables adjusted for were age, income, and education (Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

Discussion of main findings

The aim was to provide a comprehensive systematic review on the prevalence of physical health conditions, comparing lesbian or/and bisexual women or SMW (lesbian and bisexual aggregated) to heterosexual women.

The main results are as follows: (1) most striking differences by sexual identity were found for chronic respiratory diseases, particularly asthma: overall, SMW across all subgroups and in almost all studies were significantly 1.5–2 times more likely to suffer from asthma and other chronic respiratory diseases than heterosexual women; (2) evidence of higher prevalence in sexual minority compared to heterosexual women was also found regarding back pain, headaches/migraines, hepatitis B/C, oral disorders, urinary tract infections, and acne; (3) in contrast, lower prevalence in sexual minority compared to heterosexual women was found for heart attacks, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer; (4) concerning strokes, chronic kidney diseases and digestive diseases, maternal and nutritional disorders, sexual minority, and heterosexual women were about equally affected; (5) across categories, we found a trend of bisexual women being more affected than lesbian women by some of the stress-related conditions, such as asthma and headache disorders; and (6) some of the findings rely on only a few comparisons or small samples of SMW.

Findings on asthma are consistent with a previous systematic review (overall higher odds of similar magnitudes), 17 underscoring the robustness of the effect sizes. Previous research has emphasized the importance of psychosocial stress on asthma: interpersonal stress as well as divorce/separation was shown to have strong associations with asthma. 77 Non-heterosexual identity and the associated risk of being discriminated against or offended, interpreted as a psychosocial stressor, has to be considered a risk factor for asthma. As mentioned before, a previous meta-analysis concluded that discrimination is associated with mental and physical health both directly as well as indirectly via heightened stress responses and participation in unhealthy behaviors. 11 Smoking, known to be an unhealthy behavior more common in sexual minority than in heterosexual individuals,13,78 might be a further mediating factor regarding respiratory conditions: a representative study found that minority stressors were independently associated with a higher likelihood of current smoking in US sexual minority adults. 79 Another systematic review of the etiology of tobacco disparities for sexual minorities identified risk factors for smoking that might be considered unique to sexual minorities, including internalized homophobia and reactions to sexual orientation disclosure. 80 In addition, environmental injustice may also contribute: a cross-sectional study found respiratory risk from hazardous air pollutants was nearly 25% greater for same-sex than for heterosexual partners, most likely due to the higher likelihood of sexual minority individuals to live in inner-city neighborhoods with more severe air pollution. 81

As mentioned before, previous research has identified psychosocial stress as a risk factor for asthma. Similar mechanisms might explain the overall greater odds for SMW to suffer significantly more from back pain as well as headaches/migraine. For lower back pain, harassment, discrimination, 82 social isolation as well as social conflicts and perceived long-term stress 83 have been found to be relevant psychosocial risk factors. Previous research indicated that in women in general, lower perceived social status (including self-rated standing in community) is linked to heightened odds of migraines. 33 Due to sexual minority group status, lesbian- and bisexual-identifying women may perceive their social status as lower, increasing their risk for headaches/migraines. In addition, it has also been shown that SMW are at risk of having a lower socioeconomic status. 84 Similar to asthma, the likelihood of headache/migraine has also been found to be elevated due to adverse life circumstances.85,86 Severe mental illness—at least partially—accounted for the excess burden of severe headaches and migraines among SMW in one of the included studies, 61 providing empirical evidence for Lick et al. 1 minority stress model, which includes psychological stress responses as a mediating factor for physical health disparities.

Although hypertension as well as diabetes are also known to be stress-related diseases, we found lower prevalence of hypertension and diabetes in SMW compared to heterosexual women. However, it should be noted that for diabetes, differences in prevalence could not be found in those studies that explicitly excluded prediabetes and gestational diabetes. Up to 10% of all pregnant women develop gestational diabetes during pregnancy (with 50% of those subsequently developing diabetes type 2). 87 Since previous studies showed that heterosexual women are pregnant considerably more often than non-heterosexual women, 88 this might explain the greater odds of diabetes for heterosexual women, when diabetes assessment includes gestational diabetes.

Hypertension is even more likely to occur during pregnancy: it is estimated that up to 13% of all pregnant women develop hypertension during pregnancy89,90. The only study that collected data on hypertension during and other than pregnancy separately, accordingly found heterosexual women to have considerably higher prevalence of hypertension during pregnancy, but in contrast, for lesbian women, the ORs for hypertension other than pregnancy were (non-significantly) 1.5 times higher. 38 This evidence challenges the overall findings of greater odds for hypertension in studies aggregating both forms of hypertension, especially since meta-analyses found that pregnancy is almost 90% less likely for lesbian and 50% less likely for bisexual women compared to heterosexual women. 88

We found evidence that bisexual women have lower prevalence of cancer compared to heterosexual women. The median age at cancer diagnosis is 66 years 91 (and about 50–60 years for hypertension 92 and diabetes), 93 whereas, for example, asthma can occur throughout the entire lifespan, often as early as childhood and adolescence. 94 A similar pattern is known for headaches and migraines (average onset at younger ages). 95 Since older sexual minority adults are particularly hard to reach and, therefore, might be underrepresented in various studies, there is a higher risk of bias in diseases whose likelihood of occurrence increases with age. This assumption is supported by another finding: studies examining only older adults (⩾50 years) in many cases were the only studies showing (significantly) higher prevalence in SMW regarding some of the diseases (cancer,45,60 heart attack, 56 stroke). 56 The differences in average age of onset may explain why more pronounced differences were found for some diseases as opposed to others. This especially applies to unweighted samples and (A)ORs not adjusted for age. Since we found hints that older, financially disadvantaged, and less educated SMW may have been underrepresented in some samples (comparisons of AORs and ORs), prevalence rates might be (even) higher in SMW in several cases. The fact that disparities between AORs and ORs were the largest for CVDs, musculoskeletal disorders, and neoplasms, which are diseases typically known for later onsets, strongly supports this hypothesis.

Socioeconomic status, lower income levels, and limited health insurance might have impacted some results found: previous studies have shown that SMW are at risk of having a lower socioeconomic status, 84 and sexual minority individuals have poorer access to healthcare as well as less insurance coverage (in the USA). 15 There is ample research that these factors adversely affect health outcomes,96,97 underscoring their possible impact on results that were not adjusted for these factors.

There are hints from previous studies that there are higher mean testosterone levels in sexual minority compared to heterosexual women,98,99 which might be a reason for the elevated acne rates in lesbian compared to heterosexual women. However, it has to be considered that a systematic review on sex hormone levels in lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women concluded that data are too scarce to make definitive statements regarding differing hormone levels by sexual identity. 98