Abstract

Background and Objectives

The role of aging biology as a novel risk factor and biomarker for vascular outcomes in different accessible body tissues such as saliva and blood remain unclear. We aimed to (1) assess the role of aging biology as a risk factor of stroke and heart disease among individuals of same chronologic age and sex and (2) compare aging biology biomarkers measured in different accessible body tissues as novel biomarkers for stroke and heart disease in older adults.

Methods

This study included individuals who consented for blood and saliva draw in the Venous Blood Substudy and Telomere Length Study of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). The HRS is a population-based, nationally representative longitudinal survey of individuals aged 50 years and older in the United States. Saliva-based measures included telomere length. Blood-based measures included DNA methylation and physiology biomarkers. Propensity scores–matched analyses and Cox regression models were conducted.

Results

This study included individuals aged 50 years and older, who consented for blood (N = 9,934) and saliva (N = 5,808) draw in the HRS. Blood-based biomarkers of aging biology showed strong associations with incident stroke as follows: compared with the lowest tertile of blood-based biomarkers of aging, biologically older individuals had significantly higher risk of stroke based on DNA methylation Grim Age clock (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 2.64, 95% CI 1.90–3.66, p < 0.001) and Physiology-based Phenotypic Age clock (aHR = 1.75, 95% CI 1.27–2.42, p < 0.001). In secondary analysis, biologically older individuals had increased risk of heart disease as follows: DNA methylation Grim Age clock (aHR = 1.77, 95% CI 1.49–2.11, p < 0.001) and Physiology-based Phenotypic Age clock (aHR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.36–1.90, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Compared with saliva-based telomere length, blood-based aging physiology and some DNA methylation biomarkers are strongly associated with vascular disorders including stroke and are more precise and sensitive biomarkers of aging. Saliva-based telomere length and blood-based DNA methylation and physiology biomarkers likely represent different aspects of biological aging and accordingly vary in their precision as novel biomarkers for optimal vascular health.

Introduction

Despite advances in the management of vascular health, risk of vascular disease including stroke continues to rise in aging populations.1 The pathogenesis of stroke is not fully understood despite established evidence on “classic risk factors” that contribute to the onset of these disorders.2,3 The role of aging biology as a novel risk factor and biomarker of vascular disease including stroke in different body tissues such as saliva and blood remain unclear. Novel biomarkers measured in accessible body tissues are pivotal to improve precision and sensitivity to achieve primary prevention of vascular disease including stroke.4

Aging is a major risk factor of vascular disorders including stroke.2 However, aging based on chronologic age is not a sufficient indicator of morbidity and overlooks varying aging effects between individuals because calendar time does not vary for individuals of the same chronologic age.3 Furthermore, evidence on the role of biological underpinnings in relation to stroke and heart disease in different body tissues remain sparse. New methods make it possible to infer the state of biological aging in an individual by combining multiple molecular and physiologic parameters in algorithms to predict biological age.5 Biological aging biomarkers based on telomere length and DNA methylation and physiologic biomarkers are novel approaches to identify and monitor persons at risk of vascular disease including stroke. These biomarkers, which are potentially modifiable by lifestyle and behavioral factors, may be promising biomarkers for diagnosis and targeted neuroprotective therapies and for identifying high-risk groups for preventative interventions.

In this investigation, we aimed to (1) assess the role of aging biology as a novel risk factor of stroke and heart disease among individuals of same chronologic age and sex and (2) compare aging biology biomarkers measured in different accessible body tissues as novel biomarkers for vascular outcomes in older adults.

Methods

Study Population

The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) is a nationally representative longitudinal survey that recruited more than 37,000 individuals aged 50 years and older in the United States. The survey has been conducted every 2 years since 1992 with a focus on issues related to changes in health and economic circumstances in aging at both the individual and population levels.4 HRS data are linked to records from Social Security, Medicare, Veteran's Administration, the National Death Index, and employer-provided pension plan information. The HRS is coordinated by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study included individuals who consented for blood and saliva draw in the Health and Retirement 2016 Venous Blood Substudy and 2008 Telomere Length Study, respectively.4,6,7 The HRS is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan. The HRS is reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan's Health Sciences IRB. Our study was also approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University. This study has been conducted in accordance with STROBE guidelines for observational studies.8

Biological Aging Measurements

We assessed biological aging based on A-Telomere length, B-DNA Methylation, and C-Physiology measures.

A-Telomere Length Measurement

Telomere length data were available from 5,808 HRS respondents who consented for saliva sample draw during the 2008 interview wave. Telomere length data were available from 5,808 HRS respondents who consented for saliva sample draw during the 2008 interview wave, among whom approximately half had biomarker information in the HRS Venous Blood Substudy (VBS). Assays were performed by Telome Health (Telomere Diagnostics). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was used to assay average telomere length. For each patient’s sample, telomere sequence copy number (T) was compared with a single-copy gene copy number (S). Telomere length mean was proportional to the T/S ratio. Funding was provided through the National Institute on Aging (NIH U01 AG009740 and RC4 AG039029).7

The VBS and Assay Protocol in 2016 HRS

All respondents, with the exception of proxy and nursing home respondents, who completed the HRS interview in 2016 (visit 13) were asked to consent for blood draw.6 There was an excellent response rate to the blood collection protocol in 2016. The consent rate was 78.5%, among whom 82.9% had a completed collection.6 The final VBS sample included 9,934 individuals. Physiology-based biomarkers were assessed on the whole sample of participants who consented for blood draw, while DNA methylation was assessed in a subsample randomly selected and fully representative of the whole sample.6 DNA methylation assays were available for 4,104 individuals who participated in the 2016 VBS, and 4,018 samples passed the QC.9 The VBS DNA methylation subsample is considered fully representative of the HRS sample with 58% female individuals and a median age of 68.7 years.6 We included in this analysis individuals who had complete data for both physiologic and DNA methylation in 2016.

Blood samples were centrifuged and shipped overnight to CLIA-certified Advanced Research and Diagnostic Laboratory (ARDL) at the University of Minnesota. Tube processing was performed within 24 hours of arrival at the laboratory (within 48 hours of collection). All assays were performed at the University of MN ARDL under the direction of Bharat Thyagarajan.

B-DNA Methylation

DNA methylation assessment included the following clocks: Horvath DNA methylation clock10; Hannum11; Pheno Age12,15; and Grim Age.5 The chronologic classification of the clocks can be summarized as follows: the first-generation clocks were developed using machine learning to predict chronologic age. These clocks demonstrated 2 important proofs of concept: they recorded increases in clock age within individuals as they grew older13,14; and more advanced clock age estimates (i.e., clock ages older than chronologic age) were associated with increased mortality risk among individuals of the same chronologic age.15 Second-generation DNA methylation clocks were developed from analysis of mortality risk, incorporating information from DNA methylation prediction of physiologic parameters.5,15 These second-generation clocks are more predictive of morbidity and mortality12 and are proposed to have improved potential for testing impacts of interventions to slow aging.16 We analyzed the first-generation clocks proposed by Horvath10,17 and Hannum et al.,11 referred to as the Horvath Clock and Hannum Clock, respectively, and second-generation clocks proposed by Levine et al.15 and Lu et al.,5 referred to as the Pheno Age clock and Grim Age clock, respectively. The Horvath epigenetic clock is widely used. It predicts age using 353 CpG sites in the DNA methylation profile and has been used to calculate “age acceleration” in various tissues and environments. The Hannum et al. clock was trained and tested on blood-derived DNA; it comprises 71 CpG sites selected from the Illumina 450k array that captures changes in chronologic age, which is partly driven by age-related shifts in blood cell composition. DNA methylation Pheno Age was developed using data from whole blood; it correlates strongly with age in every tissue and cell tested and was based on 513 CpGs. Grim Age was constructed based on surrogate markers for select plasma proteins and smoking-pack years in a two-stage procedure.5

C-Physiology Measures

Among available and validated measures of biological aging based on physiologic parameters, we opted to use Phenotypic Age described in detail by Liu et al.18 This clock uses the following 9 parameters: albumin, creatinine, glucose, [log] C-reactive protein (CRP), lymphocyte percent, mean cell volume, red blood cell distribution width, alkaline phosphatase, and white blood cell count. These parameters were previously validated as predictors of aging in comparable settings.18

Assessment of Outcomes

The primary outcome included presence or absence of stroke. Secondary outcomes included presence or absence of any heart disease. Outcomes were assessed through self-report or proxy report. Although imperfect, the high correlation between self-reported strokes and hospital records is well documented.2,19-22 Stroke subtype specification was not available for this investigation.

Stroke events were ascertained as first-reported event that is nonfatal or fatal based on self-report or proxy report (for fatal events) of a doctor’s diagnosis (e.g., “Has the doctor ever told you that you had a stroke or transient ischemic attack?,” “Has the doctor ever told you that you had a heart problem”). New stroke cases were ascertained using the same question but specific to the wave (“e.g., reports stroke this wave”).23 Participants were also asked about the stroke month and year and when such information was not available, the median stroke month for events reported by other participants in the same interview wave. Individuals who reported a possible stroke/TIA were not included.

Heart disease was assessed as “Has a doctor ever told you that you have had a heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems?”.23 Including the combined heart assessment in this analysis was determined as priori because it has the advantage of minimizing potential recall bias in relation to heart disease subcategory among respondents.24 Measures of health in the HRS including stroke and heart disease have been widely validated in the literature and are suggested to have high rates of construct validity in older adults.25-30

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were assessed as median (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. In addition, tertiles of biological aging were assessed. Survey weights for variables included were used in descriptive analysis.31 Biomarkers were calculated as standardized residuals regressed on age at time of measurement for all eligible individuals for each biomarker.

The direct relationship between biological aging measures and stroke and heart disease, as separate binary outcomes, were assessed in a multimodel approach using propensity score–matched analysis and Cox regression models. We conducted matching of individuals with stroke and heart disease with comparison matched on age and sex using propensity scores with probit link to the nearest neighbor and without replacement.32 Models were conducted conditional on matched pairs.33 Cox regression models were used to account for time to outcomes using age scale between age at biomarker measurement and the subsequent follow-up visits among individuals for which these data were available. Models were tested for proportionality assumption.34-36 Models were adjusted for age, race, and sex including the matched samples to ensure adequate control for confounding effects and to include covariates with the most complete data for the included participants.37 All analyses were conducted using Stata SE V.16.0.

Sensitivity Analyses

To minimize potential biases due to reverse causality, we repeated the analysis after adjusting for prevalent disease before the biomarker measurement. Prior prevalent disease included presence of any of the following: prior stroke, high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, lung disease, or cancer. We tested the models using telomere length (logged) and Telomere length T/S ratio greater than 2.0.38 Potential differences in the relationship between stroke or heart disease and aging according to education attainment were assessed in a stratified analysis (college education or higher vs less education attainment).

Results

The VBS

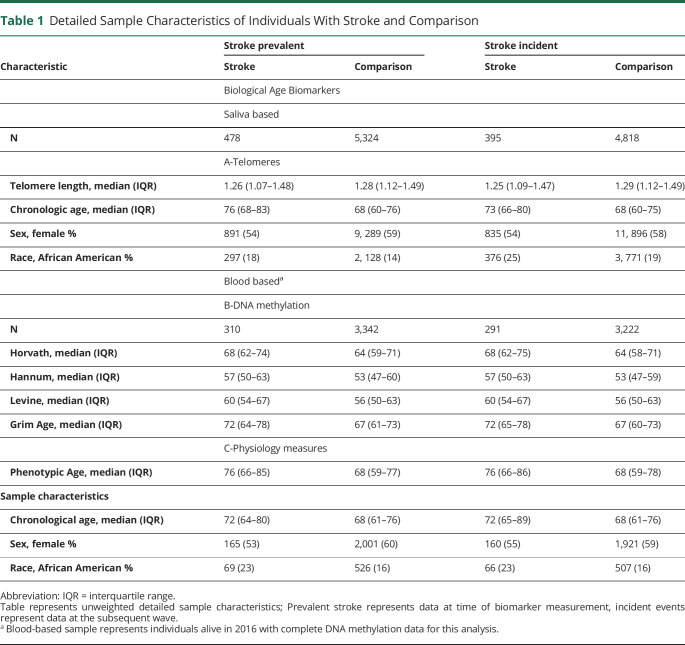

The VBS sample included 9,934 participants from the HRS 2016 wave who consented for blood draw. The stroke sample for this study included 310 and 3,342 individuals with prevalent stroke and comparison at wave 13 and 291 and 3, 222 individuals with incident strokes and comparison in wave 14, respectively (Table 1, eTable 1, links.lww.com/WNL/D215).

Table 1.

Detailed Sample Characteristics of Individuals With Stroke and Comparison

| Characteristic | Stroke prevalent | Stroke incident | ||

| Stroke | Comparison | Stroke | Comparison | |

| Biological Age Biomarkers | ||||

| Saliva based | ||||

| N | 478 | 5,324 | 395 | 4,818 |

| A-Telomeres | ||||

| Telomere length, median (IQR) | 1.26 (1.07–1.48) | 1.28 (1.12–1.49) | 1.25 (1.09–1.47) | 1.29 (1.12–1.49) |

| Chronologic age, median (IQR) | 76 (68–83) | 68 (60–76) | 73 (66–80) | 68 (60–75) |

| Sex, female % | 891 (54) | 9, 289 (59) | 835 (54) | 11, 896 (58) |

| Race, African American % | 297 (18) | 2, 128 (14) | 376 (25) | 3, 771 (19) |

| Blood baseda | ||||

| B-DNA methylation | ||||

| N | 310 | 3,342 | 291 | 3,222 |

| Horvath, median (IQR) | 68 (62–74) | 64 (59–71) | 68 (62–75) | 64 (58–71) |

| Hannum, median (IQR) | 57 (50–63) | 53 (47–60) | 57 (50–63) | 53 (47–59) |

| Levine, median (IQR) | 60 (54–67) | 56 (50–63) | 60 (54–67) | 56 (50–63) |

| Grim Age, median (IQR) | 72 (64–78) | 67 (61–73) | 72 (65–78) | 67 (60–73) |

| C-Physiology measures | ||||

| Phenotypic Age, median (IQR) | 76 (66–85) | 68 (59–77) | 76 (66–86) | 68 (59–78) |

| Sample characteristics | ||||

| Chronological age, median (IQR) | 72 (64–80) | 68 (61–76) | 72 (65–89) | 68 (61–76) |

| Sex, female % | 165 (53) | 2,001 (60) | 160 (55) | 1,921 (59) |

| Race, African American % | 69 (23) | 526 (16) | 66 (23) | 507 (16) |

Abbreviation: IQR = interquartile range.

Table represents unweighted detailed sample characteristics; Prevalent stroke represents data at time of biomarker measurement, incident events represent data at the subsequent wave.

Blood-based sample represents individuals alive in 2016 with complete DNA methylation data for this analysis.

The heart disease sample for this study included 957 and 2, 694 individuals with prevalent heart disease and comparison at wave 13 and 1002 and 2, 510 individuals with incident heart and comparison at wave 14, respectively (eTables 1 and 2, links.lww.com/WNL/D215).

Telomere Subsample and Saliva

The telomere sample included 5,808 participants from the HRS 2008 wave who consented for saliva draw. The stroke sample for this study included 478 and 5, 324 individuals with prevalent stroke and comparison at 2008 wave, 395 and 4, 818 individuals with incident strokes and comparison in 2010, respectively (Table 1, eTable 1, links.lww.com/WNL/D215).

The heart disease sample for this study included 1,443 and 4, 360 individuals with prevalent heart disease and comparison at 2008 wave, and 1,500 and 3, 739 individuals with incident heart and comparison in 2010 wave, respectively (eTables 1 and 2, links.lww.com/WNL/D215).

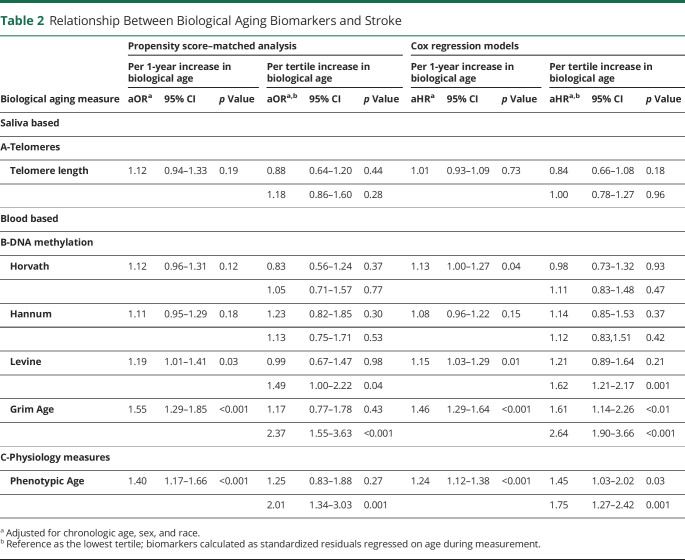

Relationship Between Biological Aging and Stroke

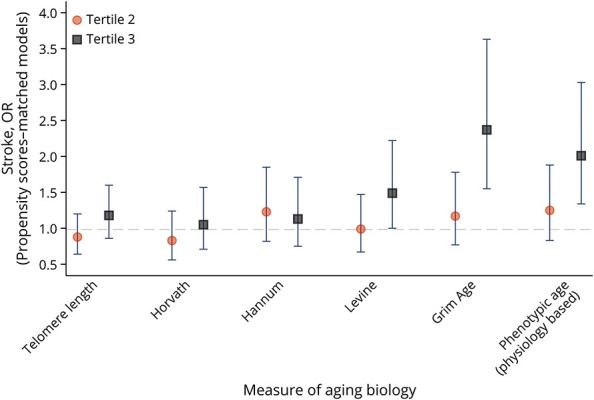

In propensity score–matched analysis, compared with the lowest tertile, the adjusted odds ratios (aORs) of biological aging with stroke showed higher magnitudes for DNA methylation Grim Age clock (aOR = 2.37, 95% CI 1.55–3.63, p < 0.001) and Physiology-based Phenotypic Age clock (aOR = 2.01 95% CI 1.34–3.03, p < 0.001). Telomere length measured in saliva was not associated with stroke (aOR 1.12; 95% CI 0.94–1.33, p = 0.19) (Table 2, eTable 3, links.lww.com/WNL/D215, Figure).

Table 2.

Relationship Between Biological Aging Biomarkers and Stroke

| Biological aging measure | Propensity score–matched analysis | Cox regression models | ||||||||||

| Per 1-year increase in biological age | Per tertile increase in biological age | Per 1-year increase in biological age | Per tertile increase in biological age | |||||||||

| aORa | 95% CI | p Value | aORa,b | 95% CI | p Value | aHRa | 95% CI | p Value | aHRa,b | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Saliva based | ||||||||||||

| A-Telomeres | ||||||||||||

| Telomere length | 1.12 | 0.94–1.33 | 0.19 | 0.88 | 0.64–1.20 | 0.44 | 1.01 | 0.93–1.09 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.66–1.08 | 0.18 |

| 1.18 | 0.86–1.60 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 0.78–1.27 | 0.96 | |||||||

| Blood based | ||||||||||||

| B-DNA methylation | ||||||||||||

| Horvath | 1.12 | 0.96–1.31 | 0.12 | 0.83 | 0.56–1.24 | 0.37 | 1.13 | 1.00–1.27 | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.73–1.32 | 0.93 |

| 1.05 | 0.71–1.57 | 0.77 | 1.11 | 0.83–1.48 | 0.47 | |||||||

| Hannum | 1.11 | 0.95–1.29 | 0.18 | 1.23 | 0.82–1.85 | 0.30 | 1.08 | 0.96–1.22 | 0.15 | 1.14 | 0.85–1.53 | 0.37 |

| 1.13 | 0.75–1.71 | 0.53 | 1.12 | 0.83,1.51 | 0.42 | |||||||

| Levine | 1.19 | 1.01–1.41 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.67–1.47 | 0.98 | 1.15 | 1.03–1.29 | 0.01 | 1.21 | 0.89–1.64 | 0.21 |

| 1.49 | 1.00–2.22 | 0.04 | 1.62 | 1.21–2.17 | 0.001 | |||||||

| Grim Age | 1.55 | 1.29–1.85 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 0.77–1.78 | 0.43 | 1.46 | 1.29–1.64 | <0.001 | 1.61 | 1.14–2.26 | <0.01 |

| 2.37 | 1.55–3.63 | <0.001 | 2.64 | 1.90–3.66 | <0.001 | |||||||

| C-Physiology measures | ||||||||||||

| Phenotypic Age | 1.40 | 1.17–1.66 | <0.001 | 1.25 | 0.83–1.88 | 0.27 | 1.24 | 1.12–1.38 | <0.001 | 1.45 | 1.03–2.02 | 0.03 |

| 2.01 | 1.34–3.03 | 0.001 | 1.75 | 1.27–2.42 | 0.001 | |||||||

Adjusted for chronologic age, sex, and race.

Reference as the lowest tertile; biomarkers calculated as standardized residuals regressed on age during measurement.

Figure. Measure of Aging Biology.

In Cox regression models, a 1-year increase in biological age based on DNA methylation was associated with higher risk of new stroke occurrence with significant results for DNA methylation Grim Age clock (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR ]= 1.46, 95% CI 1.29–1.64, p < 0.001) and Physiology-based Phenotypic Age clock (aHR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.12–1.38, p < 0.001). Similarly, 1-tertile increase in biological age was associated with almost 3 times higher risk of new stroke occurrence compared with the lowest tertile as reference as observed on DNA methylation Grim Age clock (aHR = 2.64, 95% CI 1.90–3.66, p < 0.001) and Physiology-based Phenotypic Age clock (aHR = 1.75, 95% CI 1.27–2.42, p = 0.001. Telomere length measured in saliva was not associated with stroke (aHR: 1.01, 95% CI 0.93–1.09, p = 0.73) (Table 2).

Relationship Between Biological Aging and Heart Disease

In propensity score–matched analysis, compared with the lowest tertile, DNA methylation Grim Age (aOR = 1.95, 95% 1.53, 2.48, p < 0.001) compared with physiology-based biological aging with (aOR = 2.36, 95% CI 1.86–2.99, p < 0.001). Telomere length measured in saliva was not associated with heart disease (aOR = 0.99; 95% CI 0.91–1.08, p = 0.99) (eTables 3, 4, links.lww.com/WNL/D215).

In Cox regression models, older biological age based on DNA methylation showed similar patterns with heart disease with slightly attenuated magnitudes. Statistically significant associations were observed for DNA methylation clocks Levine (aHR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.10–1.24, p < 0.001), Grim Age (aHR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.16–1.32, p < 0.001) Physiology-based Pheno Age (aHR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.18–1.32, p < 0.001). Individuals in the highest biological age tertile had almost 2 times higher risk of new heart disease occurrence as observed by both DNA methylation clocks (Levine, aHR = 1.53, 95% 1.31, 1.79, p < 0.001), Grim Age aHR = 1.77, 95% CI 1.49–2.11, p < 0.001) and Physiology-based clock (Phenotypic Age, aHR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.36–1.90, p < 0.001). Telomere length measured in saliva was not associated with heart disease (aHR = 1.00, 95% CI 0.96–1.05, p = 0.72) (eTable 4, links.lww.com/WNL/D215).

Sensitivity Analyses

Similar associations were observed after adjusting for the presence of any prevalent disease including prior stroke, high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, lung disease, or cancer (eTables 5 and 6, links.lww.com/WNL/D215). Repeating the models using log telomere length and after excluding and telomere length T/S ratio greater than 2.0 showed similar associations.

In stratified sensitivity analysis, higher education level (college education and higher) was associated with higher odds of stroke with every 1-year increase in biological age based on DNA methylation (OR: 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.0), similarly for less education attainment (OR: 1.3, 95% CI 1.2–1.5). Physiology-based biological aging showed higher odds of stroke only among those with less education attainment (OR: 1.2, 95% CI 1.1–1.4) while the association was not statistically significant among those with higher education level (OR: 1.2, 95% CI 0.9–1.6), suggesting potential impact of social health determinants on aging free of stroke.

Discussion

Age is a major risk factor of stroke and related cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases.1 Risk of stroke and heart disease continues to escalate with aging of populations and remains a leading cause of years of life lost.39 Aging biology biomarkers may represent novel screening tools for optimal vascular health through early identification of risk and improved precision for timing-specific evaluation and implementation of preventative measures beyond aging based on chronologic age.40 However, the complexity of addressing these research gaps is amplified by the aging process itself, whose biological underpinnings remain poorly understood in the context of health and disease.41

In this study, we found strong associations between stroke, heart disease, and blood-based aging measures including physiology and some DNA methylation biomarkers, while we found no associations between saliva-based telomere length, stroke, and heart disease. Previous investigations reported similar findings on the relationship between telomere length and diabetes in the HRS.42 Variations in relation to stroke and heart disease were observed in relation to 2 biological measures of aging based on physiology (a system-based measure using Phenotypic Age) and DNA methylation (using Grim Age) approaches. These differences in the associations between the biological aging DNA metrics could be potentially attributed to differences in the set of CPGs represented in each clock. We observed that changes in physiology in patients with or on the trajectory of stroke and heart disease progression in relation to aging processes showed variations compared with DNA methylation.41 These variations were also observed in propensity score-matched samples where individuals were matched on chronologic age and sex, further reducing confounding effects of chronologic age itself. Individuals who were biologically older had 2- to 3-fold increase in likelihood of new stroke or heart disease occurrence. Simultaneously, individuals who already had stroke or heart disease were biologically older compared with the general population, consistent with previous observations on older biological age among those with recurrent stroke.43

The consistent estimates across models and waves provide reassurance regarding the reliability of biological aging metrics as biomarkers for vascular outcomes. The need for novel aging biomarkers that are specific and sensitive for detecting those at risk of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease stems from several key issues; first, the close relatability of aging as a triggering mechanism by itself to vascular outcomes including stroke.43 This is evident by the increase in absolute numbers of these diseases with aging of the population and the increase in associated burden of disease, particularly dementia and cognitive impairment.44 Considering these observations, the measurement of aging based on chronologic age may be imprecise and nonmodifiable. Thus, traditional interventions or “business as usual” that determine risk or prognosis by calendar years are suboptimal for achieving primary and secondary prevention of these disorders and their associated sequelae.1 Second, the increased life span on the account of health span has created a need to revisit our approaches to risk assessments in older individuals.45,46 Therefore, novel biomarkers that may capture aging processes or changes with aging before manifestation of clinical stroke or cardiovascular disease are increasingly important in healthy aging.3 Understanding measures of optimal vascular health are essential routes for investigating opportunities for primary prevention of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disorders.47 The role of social determinants of health such as educational attainment on biological vs chronologic aging may also contribute to disparities as observed in this study and in other settings.48 Third, the recent accumulating evidence on individuals' resilience in aging despite the presence of classic risk factors of stroke and heart disease and their ability to withstand such stressors at multiorgan or system levels including the CNS may reflect factors that extend beyond measures immediately and readily assessed during stroke or heart disease diagnosis.49 In particular, biomarkers that are able to mirror individual differences in lifetime exposures and resiliency are key to understanding the etiology of cerebrovascular-free and cardiovascular disease-free aging to achieve primary prevention and extend health span.

There are several limitations in this study. First, stroke subtype specification was not feasible in this study; however, it is common to analyze stroke outcomes without stratification in the context of epidemiologic cohorts.44 Second, new strokes assessed within each wave were not first-ever strokes; however, similar associations were observed after adjustment for presence of prevalent disease, thus further ascertaining our findings. Third, currently, there is no gold standard for biological aging measures; therefore, comprehensive comparisons provide a rigorous, neutral, and reproducible way to capture biological aging effects. Last, the limited longitudinal follow-up time both in relation to assessments of new events and biological aging measures hinders our ability to understand the dynamic relationship between aging and disease in the setting of stroke and heart disease. However, the presence of strong associations despite the relatively short follow-up provides a solid foundation for extended investigations. Advances in molecular biology enables the measurement of high-dimensional cellular level changes that would aid the understanding of aetiologic pathways and our ability to develop personalized prevention tools for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease and progression to cognitive impairment and dementia as key sequelae in aging populations.

Our data show that biomarkers measured in different tissues may have remarkably different sensitivity to stroke and heart disease. In addition, individuals with similar risk profiles for cardiovascular disease and stroke were shown to have variabilities in aging biology. Such differences may influence their ability to live healthfully or progress to symptomatic disease in advanced age. These aging processes likely reflect rates of aging according to biology.41 In our study, physiology-based processes and some DNA methylation clocks showed strong associations with both existing and new stroke and heart disease. The consistent relationships observed with physiology-based biomarkers could be related to the standardized nature and established best practices in their method of measurement across laboratories. In addition, a previous investigation50 suggested that subclinical changes in physiology are related to cardiovascular disease occurrence in the setting of a randomized controlled trial.

The results of our study suggest that blood-based biological aging measures including physiology and some DNA methylation biomarkers are strongly associated with stroke and heart disease and are more precise and sensitive metrics of aging compared with saliva-based biomarkers, particularly telomere length. Saliva-based telomere length and blood-based DNA methylation and physiology biomarkers of biological aging likely represent different aspects of aging and accordingly vary in their precision as novel biomarkers for the prevention of stroke and heart disease. These variations in precision and sensitivity of aging biomarkers provide novel opportunities for primary prevention of age-related vascular disorders that require extension beyond existing diagnostic frameworks.45,46

Glossary

- ARDL

Advanced Research and Diagnostic Laboratory

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- HRS

Health and Retirement Study

- IQR

interquartile range

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- VBS

Venous Blood Substudy

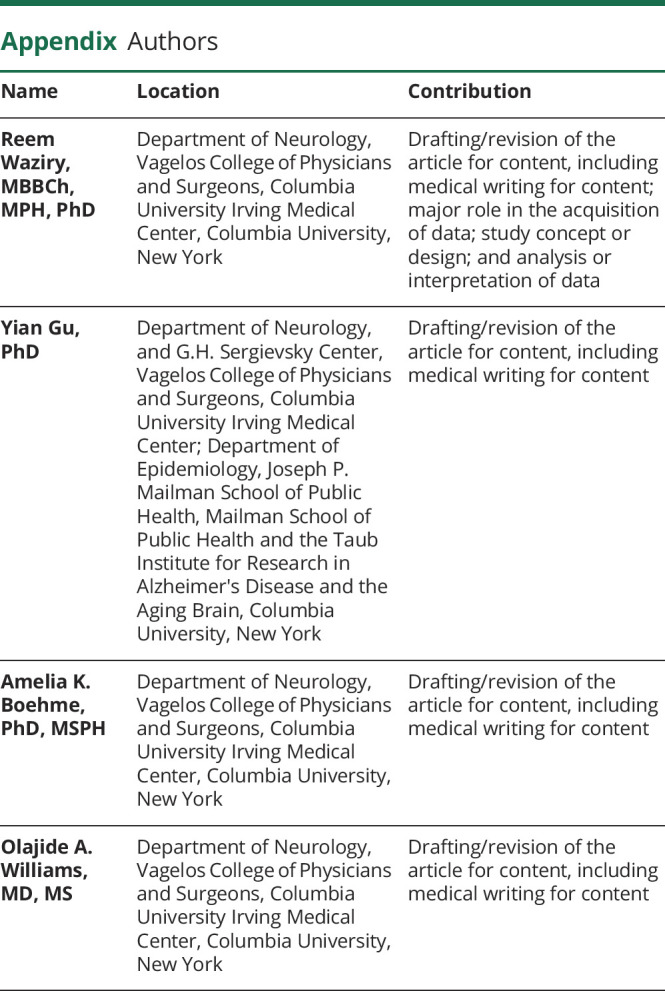

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Reem Waziry, MBBCh, MPH, PhD | Department of Neurology, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Columbia University, New York | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data |

| Yian Gu, PhD | Department of Neurology, and G.H. Sergievsky Center, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Irving Medical Center; Department of Epidemiology, Joseph P. Mailman School of Public Health, Mailman School of Public Health and the Taub Institute for Research in Alzheimer's Disease and the Aging Brain, Columbia University, New York | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Amelia K. Boehme, PhD, MSPH | Department of Neurology, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Columbia University, New York | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

| Olajide A. Williams, MD, MS | Department of Neurology, Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Columbia University, New York | Drafting/revision of the article for content, including medical writing for content |

Footnotes

CME Course: NPub.org/cmelist

Study Funding

A Clinical Translational Scholarship in Cognitive Aging and Age-Related Memory Loss funded by the McKnight Brain Research Foundation through the American Brain Foundation, in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, Grant K99 AG075196 from the National Institute of Aging, and a pilot grant from the Gertrude H. Sergievsky Center at the Department of Neurology of Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

Disclosure

The authors report no relevant disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Norrving B, Mensah GA. Global burden of stroke. Circ Res. 2017;120(3):439-448. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glymour MM, Avendano M. Can self-reported strokes be used to study stroke incidence and risk factors? Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. Stroke. 2009;40(3):873-879. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.529479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waziry R, Gras L, Sedaghat S, et al. Quantification of biological age as a determinant of age-related diseases in the Rotterdam Study: a structural equation modeling approach. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(8):793-799. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00497-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JWR, Weir DR. Cohort profile: the health and retirement study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):576-585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu AT, Quach A, Wilson JG, et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(2):303-327. doi: 10.18632/aging.101684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crimmins E, Faul J, University of Southern California, University of Michigan Bharat Thyagarajan, University of Minnesota David Weir, University of Michigan. Venous Blood Collection and Assay Protocol in the 2016 Health and Retirement Study 2016 Venous Blood Study (VBS); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health and Retirement Study. 2008 Telomere Data; 2013. Accessed October 25, 2022. hrsdata.isr.umich.edu/data-products/2008-telomere-data. [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crimmins E, Kim JK, J Fisher, J. Faul. "HRS epigenetic clocks -release 1." Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14(10):R115-R120. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannum G, Guinney J, Zhao L, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol Cell. 2013;49(2):359-367. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine ME. Assessment of Epigenetic Clocks as Biomarkers of Aging in Basic and Population Research. Oxford University Press US; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belsky DW, Moffitt TE, Cohen AA, et al. Eleven telomere, epigenetic clock, and biomarker-composite quantifications of biological aging: do they measure the same thing? Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(6):1220-1230. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marioni RE, Suderman M, Chen BH, et al. Tracking the epigenetic clock across the human life course: a meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort data. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(1):57-61. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine ME, Lu AT, Quach A, et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;10(4):573-591. doi: 10.18632/aging.101414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahy GM, Brooke RT, Watson JP, et al. Reversal of epigenetic aging and immunosenescent trends in humans. Aging Cell. 2019;18(6):e13028. doi: 10.1111/acel.13028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horvath S, Raj K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(6):371-384. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Z, Kuo PL, Horvath S, Crimmins E, Ferrucci L, Levine M. A new aging measure captures morbidity and mortality risk across diverse subpopulations from NHANES IV: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2018;15(12):e1002718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(10):1096-1103. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engstad T, Bønaa KH, Viitanen M. Validity of self-reported stroke: the Tromsø study. Stroke. 2000;31(7):1602-1607. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bots ML, Looman SJ, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Hoes AW, Grobbee DE. Prevalence of stroke in the general population: the Rotterdam Study. Stroke. 1996;27(9):1499-1501. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergmann MM, Byers T, Freedman DS, Mokdad A. Validity of self-reported diagnoses leading to hospitalization: a comparison of self-reports with hospital records in a prospective study of American adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(10):969-977. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bugliari D, Carroll J, Hayden O, et al. RAND HRS longitudinal file 2020 (V1) documentation. Aging 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coughlin SS. Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(1):87-91. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90060-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace RB, Herzog AR. Overview of the health measures in the health and retirement study. J Hum Resour. 1995;30:S84-S107. doi: 10.2307/146279 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim ES, Sun JK, Park N, Peterson C. Purpose in life and reduced incidence of stroke in older adults: The Health and Retirement Study. J Psychosomatic Res. 2013;74(5):427-432. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim ES, Park N, Peterson C. Dispositional optimism protects older adults from stroke: the Health and Retirement Study. Stroke. 2011;42(10):2855-2859. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hipp SL, Wu YY, Rosendaal NTA, Pirkle CM. Association of parenthood with incident heart disease in United States' older men and women: a longitudinal analysis of Health and Retirement Study data. J Aging Health. 2020;32(7-8):517-529. doi: 10.1177/0898264319831512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crimmins EM, Zhang YS, Kim JK, Levine ME. Changing disease prevalence, incidence, and mortality among older cohorts: the Health and Retirement Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(Suppl_1):S21-S26. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee M, Khan MM, Wright B. Is childhood socioeconomic status related to coronary heart disease? Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study (1992-2012). Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2017;3:2333721417696673. doi: 10.1177/2333721417696673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Health and Retirement Study. Sampling Weights Revised for Tracker 2.0 and Beyond. Survey Research Center, University of Michigan Ann Arbor; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leuven E, Sianesi B. PSMATCH2: Stata Module to Perform Full Mahalanobis and Propensity Score Matching, Common Support Graphing, and Covariate Imbalance Testing; 2018. econpapers.repec.org. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caliendo M, Kopeinig S. Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv. 2008;22(1):31-72. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6419.2007.00527.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Der Net JB, Janssens ACJW, Eijkemans MJC, Kastelein JJP, Sijbrands EJG, Steyerberg EW. Cox proportional hazards models have more statistical power than logistic regression models in cross-sectional genetic association studies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(9):1111-1116. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox DR, Oakes D. Analysis of Survival Data, Vol 21. CRC press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiébaut AC, Bénichou J. Choice of time‐scale in Cox's model analysis of epidemiologic cohort data: a simulation study. Stat Med. 2004;23(24):3803-3820. doi: 10.1002/sim.2098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearce N. Analysis of matched case-control studies. BMJ. 2016;352:i969. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puterman E, Gemmill A, Karasek D, et al. Lifespan adversity and later adulthood telomere length in the nationally representative US Health and Retirement Study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(42):E6335–E6342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525602113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feigin VL, Roth GA, Naghavi M, et al. Global burden of stroke and risk factors in 188 countries, during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(9):913-924. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30073-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turunen MP, Aavik E, Ylä-Herttuala S. Epigenetics and atherosclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790(9):886-891. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194-1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu H-j, Ho M, Chau PH, Geng L, Fong DYT. Salivary telomere length and the risks of prediabetes and diabetes among middle-aged and older adults: findings from the Health and Retirement Study. Acta Diabetol. 2023;60(2):273-283. doi: 10.1007/s00592-022-02004-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soriano-Tárraga C, Giralt-Steinhauer E, Mola-Caminal M, et al. Ischemic stroke patients are biologically older than their chronological age. Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8(11):2655-2666. doi: 10.18632/aging.101028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(11):1006-1018. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70236-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrucci L, Levine ME, Kuo PL, Simonsick EM. Time and the metrics of aging. Circ Res. 2018;123(7):740-744. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1365-1375. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31786-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamczyk MR, Nevado RM, Barettino A, Fuster V, Andrés V. Biological versus chronological aging: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(8):919-930. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chae DH, Wang Y, Martz CD, et al. Racial discrimination and telomere shortening among African Americans: the coronary Artery risk development in Young adults (CARDIA) study. Health Psychol. 2020;39(3):209-219. doi: 10.1037/hea0000832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rayaprolu S, Higginbotham L, Bagchi P, et al. Systems-based proteomics to resolve the biology of Alzheimer's disease beyond amyloid and tau. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46(1):98-115. doi: 10.1038/s41386-020-00840-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kraus WE, Bhapkar M, Huffman KM, et al. 2 years of calorie restriction and cardiometabolic risk (CALERIE): exploratory outcomes of a multicentre, phase 2, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(9):673-683. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30151-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]