Abstract

Uric acid (UA) is a strong endogenous antioxidant that neutralizes the toxicity of peroxynitrite and other reactive species on the neurovascular unit generated during and after acute brain ischemia. The realization that a rapid reduction of UA levels during an acute ischemic stroke was associated with a worse stroke outcome paved the way to investigate the value of exogenous UA supplementation to counteract the progression of redox-mediated ischemic brain damage. The long translational journey for UA supplementation recently reached a critical milestone when the results of the multicenter NIH stroke preclinical assessment network (SPAN) were reported. In a novel preclinical paradigm, 6 treatment candidates including UA supplementation were selected and tested in 6 independent laboratories following predefined criteria and strict methodological rigor. UA supplementation was the only intervention in SPAN that exceeded the prespecified efficacy boundary with male and female animals, young mice, young rats, aging mice, obese mice, and spontaneously hypertensive rats. This unprecedented achievement will allow UA to undergo clinical testing in a pivotal clinical trial through a NIH StrokeNet thrombectomy endovascular platform created to assess new treatment strategies in patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy. UA is a particularly appealing adjuvant intervention for mechanical thrombectomy because it targets the microcirculatory hypoperfusion and oxidative stress that limits the efficacy of this therapy. This descriptive review aims to summarize the translational development of UA supplementation, highlighting those aspects that likely contributed to its success. It includes having a well-defined target and mechanism of action, and an approach that simultaneously integrated rigorous preclinical assessment, with epidemiologic and preliminary human intervention studies. Validation of the clinical value of UA supplementation in a pivotal trial would confirm the translational value of the SPAN paradigm in preclinical research.

Introduction

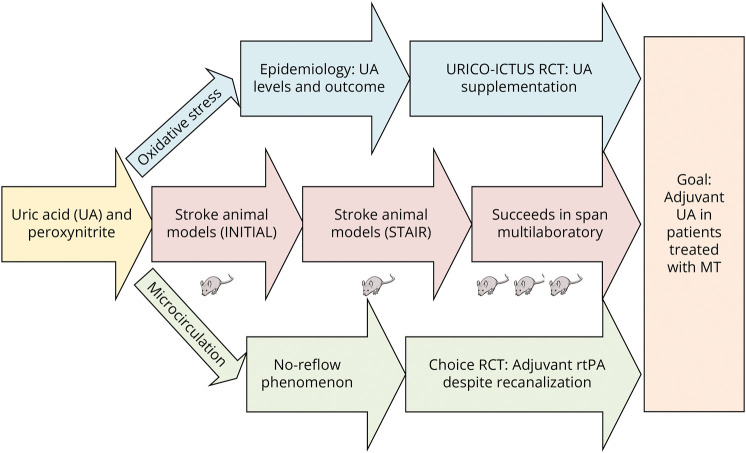

This is a story of achieving cerebroprotection for acute ischemic stroke by capitalizing in an endogenous molecule. It explains how uric acid (UA), the end product of the catabolism of purines, became a compelling candidate to deliver adjunctive cerebroprotection in patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy (MT). This journey started with the identification of oxidative stress in the ischemic penumbra as a main target to foster good outcomes in the era of reperfusion. It was followed by a long and rigorous preclinical development of UA that addressed prior shortcomings of neuroprotection that culminated by showing beneficial effects in a novel NIH preclinical multicenter network. Concomitantly, a UA clinical trial in ischemic stroke strongly supported the safety and efficacy of this drug in patients treated with reperfusion therapy because it addressed the unmet needs of the microvascular circulation. This descriptive review aims to summarize such translational development, including the critical alignment of basic science and human data that likely contributed to its success (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Graphical Depiction of the Translational Journey of UA Supplementation as an Adjuvant Cerebroprotectant.

MT = mechanical thrombectomy; RCT = randomized controlled trial; rtPA = recombinant tissue plasminogen activator; STAIR = Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable; UA = uric acid.

The Identification of a Relevant Target: Peroxynitrite

A rapid failure in energy production follows the onset of brain ischemia, leading to an increased production of reactive species to oxygen and nitrogen by the mitochondria and by the activation of enzymes such as cyclooxygenase, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase, or xanthine oxidase. Ischemia/reperfusion also leads to membrane depolarization, glutamate release, removal of the voltage-dependent Mg2+ block of the NMDA receptor, and increased intracellular Ca2+ levels. Of special translational relevance in the subset of patients treated with MT is that, free radical generation is particularly increased during early reperfusion, both in neurons and in endothelial cells.1 More specifically, the simultaneous generation of nitric oxide and superoxide in anatomical proximity favors the formation of a very toxic reaction product, the oxidant peroxynitrite.2 This generation is more prominent within pericytes and arterioles and whose main consequence is the no-reflow phenomenon or lack of microvascular perfusion despite full restoration of the proximal flow.3 Abnormal microvascular perfusion is mainly due to vasoconstriction of arterioles and pericytes, which facilitate the clogging of capillaries and venules by erythrocytes, leukocyte-platelet aggregates, and microthrombi, both formed in situ or embolized from proximal thrombi.3

In addition to the toxic vascular effects, peroxynitrite exacerbates inflammation by enhancing the activation of toll-like receptor 4 and the proinflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor κB.4,5 Moreover, the generation of peroxynitrite and free radicals also results in toxic effects on lipids, DNA, proteins, and the activation of poly(ADP ribose) polymerase, all of which contribute to neurotoxicity in stroke.2 Thus, peroxynitrite was shown to be a major cytotoxic molecule mediating glutamate-induced neuronal cell injury and apoptotic cell death,2 by inhibition of glutamate transporters mainly in the core of the infarction, but with subsequent spread of glutamate to the penumbra that results in intraischemic depolarizations.6 However, the concept that glutamate release by overexcited neurons leads to short-term and long-term brain cell death after ischemia is neither well demonstrated by basic science6 nor well supported by clinical evidence.1 Importantly, peroxynitrite builds up mostly within the ischemic penumbra, the target of reperfusion stroke treatment and less markedly in the infarct core.7 Furthermore, while glutamate levels rapidly normalize after the onset of brain ischemia,8 the abnormal generation of peroxynitrite may persist for at least 12 hours1,9 and possibly for days. These findings provide a more convenient treatment window for clinical translation based on the modulation of peroxynitrite mediated toxicity.

UA: An Old Foe, a New Friend

UA has both antioxidant and pro-oxidant properties, depending on timing and the level of other oxidants.10 Chronic high UA levels have been associated with gout, nephropathy, and cardiovascular disease,11,12 including worse outcomes after a myocardial infarction.13 The translational development of UA started with the recognition of its role as a natural defense mechanism against peroxynitrite-mediated brain damage during ischemia reperfusion.14 UA scavenges oxygen and nitrogen radicals and protects the erythrocyte membrane from lipid oxidation.10 In highly oxidative stress acute conditions, such as acute ischemic stroke, UA is cerebroprotective.14 The microvascular endothelium was identified as a major site of UA production.15 It protected against reperfusion damage induced by activated granulocytes in isolated organ preparations and preserved the ability of the endothelium to mediate vascular dilation in the face of oxidative stress.15

The potentiation of UA as a barrier against oxidative stress should be credited to human evolution. The hepatic enzyme, uricase, catabolizes UA to the more soluble allantoin.16 The uricase gene, however, has been inactivated during early primate evolution due to 2 mutations.17 As a result, humans have much higher UA levels than most mammals. This has adaptive value to counteract increased oxidative stress conditions.18 In fact, UA is the most potent endogenous scavenger of peroxynitrite and hydroxyl radicals in humans.19 It contributes up to 60% of the total plasma antioxidant activity. However, the UA endogenous levels rapidly drop after acute ischemic stroke and even more so after reperfusion. Clearly, endogenous UA levels are insufficient to counteract the impending redox-mediated challenge induced by stroke.20 This limitation led to the concept of achieving cerebroprotection by emergently supplementing with exogenous UA at the time of an acute stroke.21 The rationale for using UA, instead of other antioxidants such as disodium 2,4-sulphophenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone, is justified by the much larger magnitude of the antioxidant effect of UA as compared with these other molecules.22 Because women have lower UA levels than men, such strategy may also mitigate an existing sex-based disparity in exposure to redox-mediated toxicity and stroke outcomes.

Beneficial Effects in Animal Stroke Models

The biological premise of the effect of UA supplementation in counteracting the effect of peroxynitrite was subsequently shown in multiple preclinical experiments. A dose-dependent beneficial effects of UA therapy to prevent cell death in vitro induced by exposure to glutamate and cyanide in cultured rat hippocampal neurons,23 and a neuroprotective effect in male rats was described.23 A synergistic neuroprotective effects of UA and recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) in a thromboembolic stroke model in rats was found, including a strong reduction of ischemia-induced tyrosine nitration.24 UA improved functional outcomes, produced smaller infarcts, and reduced reactive oxygen species production in mice after transient or permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO).25 Glucose is the requisite electron donor for reperfusion-induced neuronal superoxide production in stroke, a previously unrecognized mechanism by which hyperglycemia can exacerbate ischemic brain injury.26 Inactivating superoxide production prevented the deleterious effects of hyperglycemia.26 Pericyte contraction induced by oxidative-nitrative stress impairs capillary reflow despite successful large vessel recanalization, a phenomenon that is reversed with suppression of peroxynitrite formation.3 Mice treated with UA after MCAO ischemia reperfusion had improved behavioral outcomes and smaller infarcts.27 It also showed that UA-treated animals had reduced superoxide production and nitrotyrosination in brain.27 UA supplementation attenuated MCA wall thickening, induced passive lumen expansion, and reduced brain damage in hyperemic rats, despite not increasing brain UA concentration.28 In that study, UA prevented production of superoxide, nitric oxide, nitric oxide synthases, and interleukin-18 in the MCA. It also reduced brain nitrotyrosination and improved outcome and reduced infarct size.28 Notably, all the animal experiments used a dose of 16 mg/kg, the maximal dose of UA that can be administered given the poor water solubility of the compound at physiologic pH. Altogether, these experimental data greatly supported the mechanistic role of UA in the ischemic penumbra in counteracting the oxidative stress and likely preventing the no-reflow phenomenon in the context of focal cerebral ischemia reperfusion.

Beefing Up the STAIR Pedigree

While these preclinical experiments were highly supportive, they did not fulfill all the recommendations of the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR).29 These recommendations were established after numerous past failures of translation with cerebroprotection.29 They called for additional criteria in preclinical experiments before translation to clinical studies. It was determined that conducting additional UA studies within that framework would be desirable to fully conform with the STAIR recommendations.29 Specifically, it was determined that the need to consider the use of different laboratories, longer periods of observation, blinded interventions, female animals, and animals with comorbidities. Conducting additional studies to beef up the STAIR “pedigree” of an intervention in the academic setting can be challenging because these studies are partly confirmatory. Still, this was accomplished by engaging additional laboratories and investigations toward the goal of advancing a very promising therapy. The University of Iowa group tested the long-term effect of UA in ovariectomized female mice after ischemia and reperfusion with Doppler flow confirmation.30 A randomization and blinding strategy using 2 different laboratories was used.30 Outcomes were determined using both MRI scans and neurologic scales. UA-treated mice had smaller infarct volumes and better neurologic scores at day 7.30 The University of Valencia assessed the effect of UA in ovariectomized female Wistar rats with similar methodological rigor.31 This study showed efficacy of UA reducing infarct size at day 7 in females.31 Additional supportive preclinical evidence of the efficacy of UA therapy in animals with comorbidities was shown in hypertensive rats.32 The intravenous infusion of UA reduced infarct volume and brain edema in transient MCAO mice with hyperglycemia, a comorbid condition particularly relevant to peroxynitrite-related damage.33 The UA supplementation did not prevent vascular intercellular adhesion molecule 1 upregulation and did not significantly reduce the number of neutrophils in the ischemic brain tissue induced by hyperglycemia, suggesting that UA neutralized the pro-oxidant effects of these cells.33

Human Data Translate Best to Humans

The conventional wisdom is that animal studies should be conducted before proceeding to human studies, mostly for safety reasons. However, animal models have limitations given the biological differences with humans.34 Therefore, human data are extremely valuable in cases where there is an endogenous biological parameter that can be easily measured in patients, such as the levels of UA. For example, several epidemiologic observational studies were conducted where UA was measured in patients suffering an ischemic stroke. Those studies strongly supported the positive correlation between baseline UA levels at the time of an ischemic stroke and a favorable clinical outcome.35 That was particularly true of patients treated with thrombolytics, which were more likely to achieve reperfusion.36,37 Accordingly, a meta-analysis of 8,131 patients with AIS showing that high serum UA levels at stroke onset were associated with significantly better outcomes.38

Another theoretical advantage of a normal biological parameter is the presumed safety of its judicious supplementation. The promising preclinical and epidemiologic data led to pilot interventional human studies from Chamorro et al. at the University of Barcelona including dose-escalation studies.39 Those efforts culminated in URICO-ICTUS, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b/3 trial.40 This trial enrolled 421 patients with ischemic stroke treated with alteplase within 4.5 hours of symptom onset. The intervention tested was 1,000 mg of UA intravenously over 90 minutes, equivalent to the 16 mg/kg that was used in all the supportive animal studies. A previous study showed that a dose of 500 mg of UA did show lower efficacy to lower lipid peroxidation levels at follow-up.39 The primary outcome, excellent function at 3 months by modified Rankin score, was achieved by 39% patients who received UA and 33% patients who received placebo (adjusted relative risk 1.23, 95% CI 0.96–1.56; p = 0.099) for the overall population.40 But a goal of a phase 2b/3 trial is to identify the target population likely to benefit from the intervention by exploring efficacy in mechanistically relevant subgroups that were predefined in the protocol. Notably, preplanned analyses of the study showed that UA supplementation improved outcomes in women (odds ratio [OR] 2.09, 95% CI 1.05–4.15), who are known to have lower endogenous UA levels than men.41 Women, but not men, also showed reduced infarct growth in relation with a greater nonenzymatic degradation of UA calculated as the ratio between allantoin and UA levels.41 The beneficial effect of UA compared with placebo was also increased in hyperglycemic patients at the time of therapy.42 In strong support of the ischemia reperfusion mechanism, UA also showed improvement in functional outcomes (OR 6.12, 95% CI 1.08–34.56) in those 45 patients treated with MT in addition to rtPA.43 This prespecified enriched population in this trial is equivalent to the ischemia reperfusion scenario tested in animal studies.44 The efficacy of UA in patients treated with MT supports the relevant participation of redox-mediated mechanisms in limiting the benefits of reperfusion in human stroke, also supporting the role of UA as an ancillary agent to improve microvascular reperfusion and reverse the no reflow phenomenon, as shown in preclinical studies.44 Nonetheless, these promising results need to be confirmed prospectively in further studies, and caution is warranted based on the results of all previous neuroprotection trials.

The SPAN Success Story

The stroke preclinical assessment network (SPAN) is a breakthrough in translational stroke research.45 This NIH infrastructure used an approach to preclinical research that mimics that of a randomized clinical trial.45 It included an intention-to-treat analysis, randomization, and blinding. Long-term functional outcomes were given priority over the short-term imaging gains.45 To minimize biases, those outcomes were determined remotely in a blinded way by investigators at a different center from where the animal was treated. SPAN included 2,615 animals of different sex and species and had comorbidities. Essentially, SPAN augments the STAIR recommendations in a new paradigm that has brought considerable rigor to preclinical cerebrovascular research. Six very promising cerebroprotectant interventions were brought to the network by 6 different research groups. These interventions were selected by a peer review process based on their merits. The SPAN network tested these interventions in parallel through 4 different stages. These interventions advanced or were dropped based on their performance within pre-established boundaries of futility and efficacy. Five of those 6 interventions exceeded the futility boundary in the first 3 stages. On the other hand, UA supplementation was the only intervention that avoided futility and exceeded the stringent prespecified boundary of efficacy in the corner test that was chosen as the primary outcome for this experiment.46 These exciting findings have energized the stroke community and will enable a clinical trial of UA supplementation through the new dedicated StrokeNet endovascular thrombectomy platform (STEP). While the final validation of the SPAN paradigm would require clinical confirmation of the value of UA supplementation in patients treated by MT, the thorough and successful translational journey of UA justifies high hopes for success.

Microcirculation: The Relevant Target for UA During MT

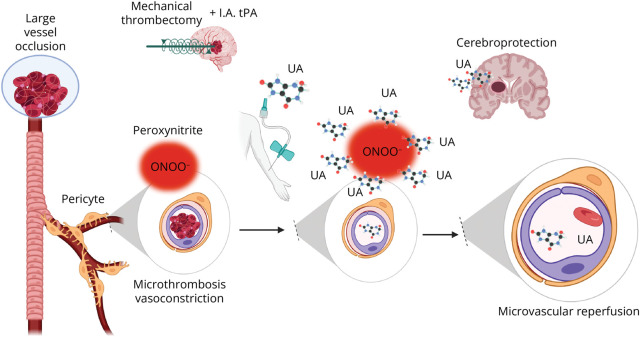

It is uncontroversial that MT significantly increases the likelihood of good outcome compared with best medical treatment in patients with large vessel occlusion (LVO) acute stroke.47 Still, in randomized clinical trials, only one-third of the patients end up disability-free at day 90, and this rate may be even lower in standard clinical practice.48 There is a critical need to unveil interventions that improve the overall benefits of endovascular therapy.49 Arguably, a reason for the limited success of MT, despite impressive rates of large vessel recanalization, can be found in the microcirculation. The recent Chemical OptImization of Cerebral Embolectomy trial demonstrated that neither complete recanalization nor successful angiographic reperfusion of the distal downstream ischemic territory is synonymous of nutritional reperfusion of the ischemic brain in patients treated with MT.50 In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, patients who obtained a modified treatment in cerebral infarction score of 2b or greater after MT had a 18.4% increment in the absolute rate of excellent outcome at 90 days after the administration of adjunctive intra-arterial thrombolysis and with no relevant angiographic differences compared with the group treated with placebo.50 Nonetheless, in a nested-perfusion MRI study performed post-MT, the prevalence of microvascular hypoperfusion (no-reflow phenomenon) was 58% in the placebo group and it was significantly reduced among patients treated with adjunctive thrombolysis.51 These findings underscore the limitation of cerebral angiography in assessing the state of the microcirculation after MT. At the same time, they highlight the contribution of microcirculation to the clinical impact of thrombectomy, thus identifying an important new therapeutic target (Figure 2). It is within this new scenario that UA supplementation emerges as a timely intervention in the ever-growing proportion of patients with stroke treated with reperfusion therapy.

Figure 2. Mechanistic Role of UA in the Current Reperfusion Scenario.

After a large vessel occlusion, the microcirculation is also impaired due in part to peroxynitrite generation in capillary pericytes. UA during thrombectomy scavenges peroxynitrite and other reactive species resulting in improved flow in the microcirculation and improved tissue perfusion and cerebroprotection. Created with BioRender.com. rtPA = recombinant tissue plasminogen activator; UA = uric acid.

Potential Clinical Implications

UA supplementation has a significant potential therapeutic value in patients with stroke, but it requires a prior validation in a properly designed and executed confirmatory clinical trial. The available clinical data support that patients treated with MT have the greatest response to treatment. Although the number of patients who received thrombectomy in URICO-ICTUS was small, the reliability of this finding is supported by the high rate of recanalization described in these patients. MT-treated patients have the greatest exposure to redox mechanisms and reperfusion damage, a scenario that increases the odds for detecting benefits of UA supplementation. Therefore, patients with LVO receiving MT are the target population for such confirmatory clinical trial, expectedly performed within the STEP. For example, a clinical trial with a conservative estimate of an 11% absolute treatment effect of UA supplementation over placebo (the observed absolute treatment effect was 19%) would have an 85% power to declare superiority at a first interim analysis after the recruitment of only 500 patients. Nonetheless, for UA, supplementation could also be useful in other patients who recanalize despite the lack of thrombectomy (i.e., patients treated with thrombolytic therapy only). Clinicians should expect a second testing stage where UA supplementation will be assessed in stroke patients with limited access to thrombectomy that can only receive thrombolytic therapy. Given the 7% absolute treatment effect of UA supplementation over placebo found previously, such a trial would require approximately 1,000 patients to have 85% power to demonstrate clinical superiority in the primary clinical outcome.

Summary

The success of UA supplementation in SPAN consolidates a new paradigm to execute preclinical research with excellent rigor. This is a critical milestone that may serve as a model for future candidate interventions. The UA story emphasizes the importance of identifying a safe intervention with a clear mechanism of action. It also highlights the importance of testing it in different animal models compatible with such mechanisms, in this case ischemia reperfusion with an emphasis in the microcirculation. Given the limitations of animal stroke models, it underscores the value of leveraging human data with preclinical experiments during translational stroke research.

Glossary

- LVO

large vessel occlusion

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- MCAO

MCA occlusion

- MT

mechanical thrombectomy

- OR

odds ratio

- rtPA

recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

- SPAN

stroke preclinical assessment network

- STAIR

Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable

- STEP

StrokeNet endovascular thrombectomy platform

- UA

uric acid

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Enrique C. Leira, MD, MS | Department of Neurology, and Departments of Neurosurgery & Epidemiology, University of Iowa, Iowa City | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Anna M. Planas, PhD | Institute of Biomedical Research of Barcelona (IIBB), Spanish National Research Council (CSIC); August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Anil K. Chauhan, PhD | Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Angel Chamorro, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology, University of Iowa, Iowa City; August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Barcelona; Hospital Clinic, University of Barcelona, Spain | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design |

Study Funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

E.C. Leira has received salary support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke as co-PI of SPAN at the University of Iowa. A.M. Planas reports no relevant disclosure relevant to this manuscript. A.K. Chauhan has received salary support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke as co-PI of SPAN at the University of Iowa. A. Chamorro has a patent in UA use in mechanical thrombectomy and stocks in Freeox biotech. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Lipton SA, Choi YB, Pan ZH, et al. A redox-based mechanism for the neuroprotective and neurodestructive effects of nitric oxide and related nitroso-compounds. Nature. 1993;364(6438):626-632. doi: 10.1038/364626a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(1):315-424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yemisci M, Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Vural A, Can A, Topalkara K, Dalkara T. Pericyte contraction induced by oxidative-nitrative stress impairs capillary reflow despite successful opening of an occluded cerebral artery. Nat Med. 2009;15(9):1031-1037. doi: 10.1038/nm.2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das S, Alhasson F, Dattaroy D, et al. NADPH oxidase-derived peroxynitrite drives inflammation in mice and human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis via TLR4-lipid raft recruitment. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(7):1944-1957. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ziegler K, Kunert AT, Reinmuth-Selzle K, et al. Chemical modification of pro-inflammatory proteins by peroxynitrite increases activation of TLR4 and NF-κB: implications for the health effects of air pollution and oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2020;37:101581. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrew RD, Farkas E, Hartings JA, et al. Questioning glutamate excitotoxicity in acute brain damage: the importance of spreading depolarization. Neurocrit Care. 2022;37(suppl 1):11-30. doi: 10.1007/s12028-021-01429-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabian RH, DeWitt DS, Kent TA. In vivo detection of superoxide anion production by the brain using a cytochrome c electrode. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995;15(2):242-247. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham SH, Shiraishi K, Panter SS, Simon RP, Faden AI. Changes in extracellular amino acid neurotransmitters produced by focal cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 1990;110(1-2):124-130. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90799-f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinuta Y, Kikuchi H, Ishikawa M, Kimura M, Itokawa Y. Lipid peroxidation in focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosurg. 1989;71(3):421-429. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.3.0421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proctor PH. Uric acid: neuroprotective or neurotoxic? Stroke. 2008;39(5):e88; author reply e89. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozkan Y, Yardim-Akaydin S, Imren E, Torun M, Simşek B. Increased plasma homocysteine and allantoin levels in coronary artery disease: possible link between homocysteine and uric acid oxidation. Acta Cardiol. 2006;61(4):432-439. doi: 10.2143/AC.61.4.2017305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaubert M, Bardin T, Cohen-Solal A, et al. Hyperuricemia and hypertension, coronary artery disease, kidney disease: from concept to practice. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):4066. doi: 10.3390/ijms21114066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demiray A, Afsar B, Covic A, et al. The role of uric acid in the acute myocardial infarction: a narrative review. Angiology. 2022;73(1):9-17. doi: 10.1177/00033197211012546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos CX, Anjos EI, Augusto O. Uric acid oxidation by peroxynitrite: multiple reactions, free radical formation, and amplification of lipid oxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;372(2):285-294. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker BF. Towards the physiological function of uric acid. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993;14(6):615-631. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90143-i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amaro S, Jiménez-Altayó F, Chamorro Á. Uric acid therapy for vasculoprotection in acute ischemic stroke. Brain Circ. 2019;5(2):55-61. doi: 10.4103/bc.bc_1_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu XW, Muzny DM, Lee CC, Caskey CT. Two independent mutational events in the loss of urate oxidase during hominoid evolution. J Mol Evol. 1992;34(1):78-84. doi: 10.1007/BF00163854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ames BN, Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Hochstein P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78(11):6858-6862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Squadrito GL, Cueto R, Splenser AE, et al. Reaction of uric acid with peroxynitrite and implications for the mechanism of neuroprotection by uric acid. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;376(2):333-337. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gariballa SE, Hutchin TP, Sinclair AJ. Antioxidant capacity after acute ischaemic stroke. QJM. 2002;95(10):685-690. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/95.10.685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chamorro A, Planas AM, Muner DS, Deulofeu R. Uric acid administration for neuroprotection in patients with acute brain ischemia. Med Hypotheses. 2004;62(2):173-176. doi: 10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00324-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maples KR, Ma F, Zhang YK. Comparison of the radical trapping ability of PBN, S-PPBN and NXY-059. Free Radic Res. 2001;34(4):417-426. doi: 10.1080/10715760100300351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu ZF, Bruce-Keller AJ, Goodman Y, Mattson MP. Uric acid protects neurons against excitotoxic and metabolic insults in cell culture, and against focal ischemic brain injury in vivo. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53(5):613-625. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romanos E, Planas AM, Amaro S, Chamorro A. Uric acid reduces brain damage and improves the benefits of rt-PA in a rat model of thromboembolic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(1):14-20. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haberman F, Tang SC, Arumugam TV, et al. Soluble neuroprotective antioxidant uric acid analogs ameliorate ischemic brain injury in mice. Neuromolecular Med. 2007;9(4):315-323. doi: 10.1007/s12017-007-8010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suh SW, Shin BS, Ma H, et al. Glucose and NADPH oxidase drive neuronal superoxide formation in stroke. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(6):654-663. doi: 10.1002/ana.21511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma YH, Su N, Chao XD, et al. Thioredoxin-1 attenuates post-ischemic neuronal apoptosis via reducing oxidative/nitrative stress. Neurochem Int. 2012;60(5):475-483. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onetti Y, Dantas AP, Perez B, et al. Middle cerebral artery remodeling following transient brain ischemia is linked to early postischemic hyperemia: a target of uric acid treatment. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308(8):H862-H874. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00001.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lapchak PA. Scientific rigor recommendations for optimizing the clinical applicability of translational research. J Neurol Neurophysiol. 2012;3:e111. doi: 10.4172/2155-9562.1000e111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhanesha N, Vazquez-Rosa E, Cintron-Perez CJ, et al. Treatment with uric acid reduces infarct and improves neurologic function in female mice after transient cerebral ischemia. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(5):1412-1416. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aliena-Valero A, Lopez-Morales MA, Burguete MC, et al. Emergent uric acid treatment is synergistic with mechanical recanalization in improving stroke outcomes in male and female rats. Neuroscience. 2018;388:263-273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jimenez-Xarrie E, Perez B, Dantas AP, et al. Uric acid treatment after stroke prevents long-term middle cerebral artery remodelling and attenuates brain damage in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Transl Stroke Res. 2020;11(6):1332-1347. doi: 10.1007/s12975-018-0661-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Justicia C, Salas-Perdomo A, Pérez-de-Puig I, et al. Uric acid is protective after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in hyperglycemic mice. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(3):294-305. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0515-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fluri F, Schuhmann MK, Kleinschnitz C. Animal models of ischemic stroke and their application in clinical research. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:3445-3454. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S56071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chamorro A, Obach V, Cervera A, Revilla M, Deulofeu R, Aponte JH. Prognostic significance of uric acid serum concentration in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2002;33(4):1048-1052. doi: 10.1161/hs0402.105927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amaro S, Urra X, Gómez-Choco M, et al. Uric acid levels are relevant in patients with stroke treated with thrombolysis. Stroke. 2011;42(1 suppl):S28-S32. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X, Liu M, Chen M, Ge QM, Pan SM. Serum uric acid is neuroprotective in Chinese patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(5):1080-1086. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z, Lin Y, Liu Y, et al. Serum uric acid levels and outcomes after acute ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(3):1753-1759. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9134-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amaro S, Soy D, Obach V, Cervera A, Planas AM, Chamorro A. A pilot study of dual treatment with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and uric acid in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2007;38(7):2173-2175. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.480699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chamorro A, Amaro S, Castellanos M, et al. Safety and efficacy of uric acid in patients with acute stroke (URICO-ICTUS): a randomised, double-blind phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(5):453-460. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70054-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Llull L, Laredo C, Renu A, et al. Uric acid therapy improves clinical outcome in women with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(8):2162-2167. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amaro S, Llull L, Renu A, et al. Uric acid improves glucose-driven oxidative stress in human ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(5):775-783. doi: 10.1002/ana.24378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chamorro A, Amaro S, Castellanos M, et al. Uric acid therapy improves the outcomes of stroke patients treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and mechanical thrombectomy. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(4):377-382. doi: 10.1177/1747493016684354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutherland BA, Neuhaus AA, Couch Y, et al. The transient intraluminal filament middle cerebral artery occlusion model as a model of endovascular thrombectomy in stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36(2):363-369. doi: 10.1177/0271678X15606722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyden PD, Bosetti F, Diniz MA, et al. The stroke preclinical assessment network: rationale, design, feasibility, and stage 1 results. Stroke. 2022;53(5):1802-1812. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.038047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lyden PD, Diniz MA, Bosetti F, et al. A multi-laboratory preclinical trial in rodents to assess treatment candidates for acute ischemic stroke. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15(714):eadg8656. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adg8656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387(10029):1723-1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00163-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adcock AK, Schwamm LH, Smith EE, et al. Trends in use, outcomes, and disparities in endovascular thrombectomy in US patients with stroke aged 80 years and older compared with younger patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2215869. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chamorro Á. Neuroprotectants in the era of reperfusion therapy. J Stroke. 2018;20(2):197-207. doi: 10.5853/jos.2017.02901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Renú A, Millán M, San Román L, et al. Effect of intra-arterial alteplase vs placebo following successful thrombectomy on functional outcomes in patients with large vessel occlusion acute ischemic stroke: the CHOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327(9):826-835. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laredo C, Rodríguez A, Oleaga L, et al. Adjunct thrombolysis enhances brain reperfusion following successful thrombectomy. Ann Neurol. 2022;92(5):860-870. doi: 10.1002/ana.26474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]