Abstract

The pbp gene (renamed dacC), identified by the Bacillus subtilis genome sequencing project, encodes a putative 491-residue protein with sequence homology to low-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins. Use of a transcriptional dacC-lacZ fusion revealed that dacC expression (i) is initiated at the end of stationary phase; (ii) depends strongly on transcription factor ςH; and (iii) appears to be initiated from a promoter located immediately upstream of yoxA, a gene of unknown function located upstream of dacC on the B. subtilis chromosome. A B. subtilis dacC insertional mutant grew and sporulated identically to wild-type cells, and dacC and wild-type spores had the same heat resistance, cortex structure, and germination and outgrowth kinetics. Expression of dacC in Escherichia coli showed that this gene encodes an ∼59-kDa membrane-associated penicillin-binding protein which is highly toxic when overexpressed.

The polymerization and cross-linking of peptidoglycan in bacteria is catalyzed by a group of enzymes known as penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). In Bacillus subtilis, a gram-positive bacterium that forms heat-resistant endospores upon nutrient deprivation, PBPs are required not only for synthesis of peptidoglycan in vegetative cells but also for synthesis of the sporulation septum and the spore’s primordial germ cell wall and cortex (7).

Low-molecular-weight PBPs are usually monofunctional dd-peptidases, which regulate the number of peptide cross-links formed in the peptidoglycan (11, 12). To date, three genes from B. subtilis (dacA, dacB, and dacF) encoding polypeptides with high sequence homology to low-molecular-weight dd-peptidases have been cloned and characterized (8, 45, 49). The most well characterized of these is the PBP5*-encoding gene, dacB, which is transcribed around stage III of sporulation from a ςE-dependent promoter (8, 37), suggesting a role for PBP5* in spore cortex synthesis. Indeed, spores of dacB null mutants are heat sensitive (6, 30), and their cortex has more peptide side chains, a higher degree of cross-linking, and less muramic acid lactam residues than that of wild-type spores (4, 29, 30). The gene encoding PBP5, dacA (45), accounts for most if not all dd-carboxypeptidase activity in exponentially growing B. subtilis (22, 45, 47) and is present in lower amounts in stationary-phase and sporulating cells (39). Inactivation of PBP5 is not lethal for the cell (5, 45) and also has no effect on spore heat resistance (6, 30). However, overexpression of Bacillus stearothermophilus dacA in Escherichia coli results in cell lysis (10), and attempts to transform E. coli with a plasmid containing B. subtilis dacA were unsuccessful (45). The dacF gene product has not yet been identified biochemically, but studies using dacF-lacZ transcriptional fusions showed that dacF is transcribed in the forespore compartment of the sporulating cell (49) and that this transcription is ςF dependent (36). Disruption of dacF has no obvious effect on spore formation, spore cortex structure, or spore properties (4, 29, 49), and thus the function of this gene is unclear.

Recently, the B. subtilis genome sequencing project (20, 46) identified the pbp gene (here renamed dacC) encoding a putative 491-residue low-molecular-weight PBP with highest sequence homology to E. coli PBP4 (19) and PBP4 from Actinomadura strain R39 (14). In this work we show that dacC expression is dependent on transcription factor ςH and that dacC does indeed encode a new membrane-bound PBP, which migrates at the position of B. subtilis PBP4*, between PBP4 and PBP5, on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Therefore, we have named this protein PBP4a. While a dacC mutation had no phenotypic effect in B. subtilis, overexpression of dacC was toxic to E. coli.

Transcriptional regulation of dacC.

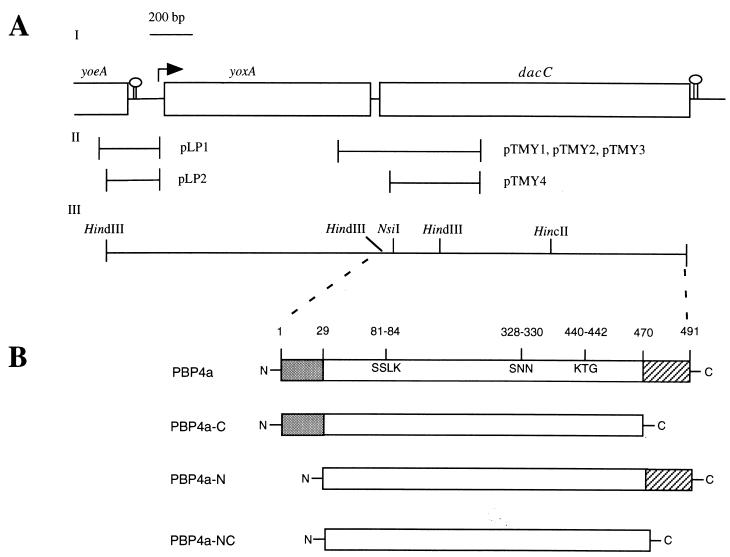

To study the transcriptional regulation of dacC, strain PS2323 carrying a transcriptional dacC-lacZ fusion at the dacC locus was constructed (all B. subtilis strains used in this study are listed in Table 1). PCR was used to generate a 654-bp fragment containing a part of the B. subtilis genome starting 162 nucleotides (nt) upstream and ending 480 nt downstream of the putative dacC translational initiation codon. The primers used for PCR were Y1 and Y2 (Table 2), and the template was chromosomal DNA from strain PS832. Digestion of the 654-bp PCR product with BamHI and EcoRI yielded a 649-bp fragment which was ligated into BamHI/EcoRI-digested plasmid pUC19 to generate plasmid pTMY1 (Fig. 1A). DNA sequencing confirmed that the DNA sequence of the insert was correct. The 649-bp BamHI/EcoRI fragment from pTMY1 was ligated into BamHI/EcoRI-digested plasmid pJF751a (43) to generate plasmid pTMY2 (Fig. 1A), which was used to transform PS832 to generate strain PS2323, which contains a transcriptional dacC-lacZ fusion at the dacC locus. After Southern blot analysis was used to verify that the chromosome structure of PS2323 was as expected (data not shown), cells were sporulated at 37°C in 2× SG medium (24), 1-ml samples were withdrawn at various times, and the β-galactosidase activities of the samples were measured using the substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-galactoside (27). As shown in Fig. 2A, dacC-lacZ expression began shortly after the end of exponential growth and peaked about 2 h into sporulation. However, no β-galactosidase activity was detected in purified spores of PS2323 (results not shown). The level of dacC-lacZ expression detected was also much lower than for most sporulation genes; when o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside was used as a substrate, the maximum β-galactosidase activity measured with strain PS2323 (dacC-lacZ) was only 7 to 8 Miller units compared with 2 to 3 Miller units for cells of the wild-type strain, PS832 (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotypea | Source, reference, or constructionb |

|---|---|---|

| PS832 | Wild type, trp+ revertant of 168 | Laboratory stock |

| AG518 | pheA1 trpC2 abrB::Tn917 Ermr | A. D. Grossman |

| AG558d | pheA1 trpC2 spo0H::pJ0H7d Cmr | A. D. Grossman |

| DZR168 | pheA1 trpC2 spo0A::Ermr | A. D. Grossman |

| MO1615 | spo0H::Kanr | P. Stragier |

| PS258 | trpC2 codY::Ermr | A. L. Sonenshein |

| RL1061 | PY79 ΔspoIIGB::Ermr | R. Losick |

| SM69-1 | PY79 ΔspoIIA::Spr | S. Meyer |

| PS1805 | ΔpbpE::Ermr | 31 |

| PS1840 | spo0A::Ermr | DZR168→PS832 |

| PS2322 | amyE::dacC-lacZ Cmr | pTMY3→PS832 |

| PS2323 | dacC-lacZ Cmr | pTMY2→PS832 |

| PS2324 | dacC::pTMY4 Spr | pTMY4→PS832 |

| PS2459 | dacC-lacZ spo0H::Kanr Cmr | MO1615→PS2323 |

| PS2521 | dacC-lacZ ΔspoIIGB::Ermr Cmr | RL1061→PS2323 |

| PS2522 | dacC-lacZ ΔspoIIA::Spr Cmr | SM69-1→PS2323 |

| PS2627 | dacC-lacZ Ermr | pCm::Ermc→PS2323 |

| PS2628 | spo0H::pJ0H7d Cmr | AG558→PS832 |

| PS2629 | dacC-lacZ spo0H::pJ0H7d Ermr Cmr | AG558→PS2627 |

| PS2630 | dacC-lacZ abrB::Tn917 Ermr Cmr | AG518→PS2323 |

| PS2631 | abrB::Tn917 Ermr | AG518→PS832 |

| PS2632 | dacC-lacZ spo0A::Ermr Cmr | PS1840→PS2323 |

| PS2760 | amyE::yoxA-lacZ Cmr | pLP2→PS832 |

| PS2795 | dacC-lacZ spo0H::Kanrspo0A::Ermr Cmr | PS1840→PS2459 |

| LP41 | dacC-lacZ codY::Ermr Cmr | PS258→PS2323 |

Abbreviations: Cmr, resistance to 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml; Ermr, resistance to 0.5 μg of erythromycin and 12.5 μg of lincomycin per ml; Spr, resistance to 100 μg of spectinomycin per ml; Kanr, resistance to 10 μg of kanamycin per ml.

B. subtilis was transformed as described previously (2), and transformants were selected on 2× SG agar plates containing appropriate antibiotics.

Described in reference 40.

This strain contains a truncated copy of spo0H under the control of its normal promoter and an intact copy of spo0H under the control of Pspac and is therefore spo0H in the absence of IPTG (18).

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used in this study

| Primer | Nucleotide sequencea |

|---|---|

| Y1 | 5′-CGGAATTCCTTACACATGGGTGACAAACGCAGTG-3′ |

| Y2 | 5′-CGGATCCACGTATCATCACCGATCAGATTGCC-3′ |

| pbpy-5′ | 5′-CATATGAAAAAAAGCATAAAGCTTTATG-3′ |

| pbpy-3′ | 5′-GGATCCCTATTATTGATTTGCCAAAATG-3′ |

| pbpy-P5 | 5′-CATATGGCTGAAAAACAAGATGCACTTTC-3′ |

| pbpy-P6 | 5′-GGATCCCTAATTTAGAAGAATAGAGAAAACAAG-3′ |

| yoxa-P2a | 5′-CGCGGATCCTTGATTCATTGCTAG-3′ |

| yoea-3′ | 5′-TCCCCCGGGTGCCTGTCGCTTTC-3′ |

Restriction endonuclease sites are underlined.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the dacC locus, and constructs and protein variants generated. (A) Map of the dacC locus. (I) Putative ORFs are indicated by open boxes, potential transcription terminators are shown as stem-loop structures, and the arrow depicts the predicted transcription initiation site and direction of transcription. (II) Fragments used in plasmid constructs for insertional mutagenesis and for generation of transcriptional dacC-lacZ fusions. (III) Map of selected restriction endonuclease cleavage sites. (B) Schematic depiction of PBP4a variants generated in this work. Amino acids 1 to 29 (gray) constitute a cleavable signal peptide as described in the text. The three regions that constitute the penicillin-binding site (81SSLK84, 328SNN330, and 440KTG442) were inferred by sequence alignment of PBP4a with PBP4 from Actinomadura strain R39 (14) and E. coli PBP4 (19) using GCG software (Wisconsin Package Version 9.1; Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.). Amino acids 470 to 491 (hatched) were predicted by a computer analysis (DNA Strider 1.2) to form an amphipathic α-helix, potentially serving as a membrane anchor. Numbers refer to amino acids of the PBP4a primary sequence. The figure is not drawn to scale.

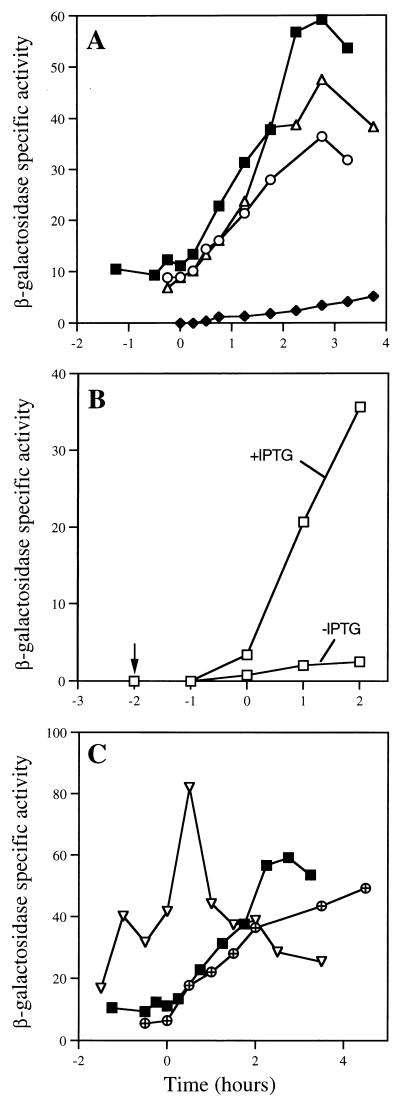

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional regulation of dacC. B. subtilis strains containing transcriptional dacC-lacZ fusions at the dacC locus were grown and sporulated at 37°C in 100 ml of 2× SG medium with no antibiotics (24), the OD600 values of the cultures were measured, and 1-ml samples were withdrawn for measurement of β-galactosidase activity as described in the text at the times indicated (t0 is defined as the end of exponential phase). Values on the y axis are fluorescence units per OD600 unit of the cultures. (A) β-Galactosidase activities in strains lacking sigma factors. Symbols and strains (relevant genotypes) are as follows: ■, PS2323 (wild type); ⧫, PS2459 (spo0H::Kanr); ○, PS2522 (ΔspoIIA::Spr); and ▵, PS2521 (ΔspoIIGB::Ermr). (B) β-Galactosidase activity in strain PS2629 (Pspac-spo0H) with or without IPTG (arrow indicates time of IPTG addition). (C) β-Galactosidase activities in transcription factor mutant strains. Symbols and strains (relevant genotypes) are as follows: ▿, PS2632 (spo0A::Ermr); ⊕, PS2630 (abrB::Tn917); and ■, PS2323 (wild type).

The timing of its expression suggests that dacC may be a stationary-phase- or early-sporulation-specific gene. To test this hypothesis, mutations disrupting the genes encoding ςH (spo0H::Kanr), ςE (ΔspoIIGB::Ermr), or the ςF operon (ΔspoIIA::Spr) were introduced into strain PS2323 and dacC-lacZ expression was monitored as described above. The spo0H::Kanr mutation (PS2459) completely abolished dacC-lacZ expression, while the effects of the spoIIGB (PS2521) and spoIIA (PS2522) mutations were minimal (Fig. 2A). To further analyze the dependence of dacC expression on ςH, a dacC-lacZ fusion strain (PS2629) which contains a truncated copy of the spo0H gene under control of its normal promoter and an intact copy of spo0H under the control of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter Pspac (18, 50) was generated and analyzed. Consistent with the observed lack of dacC-lacZ expression in the spo0H::Kanr mutant (PS2459) no significant β-galactosidase activity was detected when strain PS2629 was grown in 2× SG medium without an inducer (Fig. 2B). In contrast, when 1 mM IPTG was added to an exponentially growing culture of strain PS2629 at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5, the β-galactosidase activity measured increased significantly, but only after more than 2 h of induction, when the cells were well into stationary phase (Fig. 2B). A likely explanation for this delay is that spo0H expression is regulated posttranscriptionally so that induction of spo0H expression does not lead to an immediate rise in functional ςH levels (16, 48).

Transcription of spo0H occurs at a very low level during vegetative growth due to repression of spo0H transcription by the AbrB repressor (9, 48). This repression is relieved by the key regulator of sporulation initiation, Spo0A (9, 41), which becomes activated by phosphorylation via a complex signal transduction pathway when cells are deprived of nutrients (17). In addition to affecting spo0H transcription, AbrB also represses transcription of some other sporulation genes by binding directly to their promoter regions (34). To analyze the influence of Spo0A and AbrB on dacC transcription, spo0A::Ermr and abrB::Tn917 mutations were introduced into PS2323 to generate strains PS2632 and PS2630, respectively, and the dacC-lacZ expression of these strains was measured. Neither the spo0A::Ermr nor the abrB::Tn917 mutation significantly altered the level of dacC-lacZ expression, although the onset of expression was slightly earlier in the strain with the abrB mutation (Fig. 2C), perhaps due to a change in the timing of spo0H transcription in this strain. The lack of effect of a spo0A mutation on dacC-lacZ expression is in contrast to what has been reported for most ςH-dependent genes expressed around the onset of sporulation (15). The lack of dacC-lacZ expression in a spo0A spo0H double mutant (data not shown) excluded the possibility that the dacC-lacZ expression observed in the spo0A::Ermr mutant resulted from the activation of another promoter in the dacC region. However, when cells were grown in nutrient sporulation broth (DSM [35]) instead of 2× SG, both the spo0A::Ermr and the abrB::Tn917 mutations abolished dacC-lacZ expression while in a wild-type background, and dacC-lacZ expression occurred with a similar timing as in 2× SG but the level of expression was about twofold lower (data not shown). We have no simple explanation for these findings, but we have found that omitting glucose from the 2× SG medium had no effect on dacC-lacZ expression (results not shown). A mutation in codY, a gene encoding a repressor of other stationary phase-induced genes (38), also had no obvious effect on dacC-lacZ transcription when cells were grown in 2× SG medium (data not shown).

While ςH may affect transcription of some genes indirectly by stimulating transcription of spo0A (33), the strong dependence of dacC expression on spo0H transcription suggests that the dacC promoter may be directly recognized by EςH (18). To identify potential regulatory sequences upstream of dacC, plasmid pTMY3 was introduced into PS832 to generate strain PS2322, which contains a dacC-lacZ fusion at the amyE locus. Plasmid pTMY3 is a derivative of pDG268 (3) that contains the 649-bp BamHI/EcoRI fragment from pTMY1 (Fig. 1A). No significant β-galactosidase activity was detected in this strain (results not shown), suggesting that the dacC promoter is upstream of the 649-bp BamHI/EcoRI fragment in PS2322. The DNA sequence of the region upstream of dacC suggests that dacC may be in a two-gene operon with a gene of unknown function termed yoxA (20). Strikingly, the region immediately upstream of the putative yoxA translational initiation codon contains sequences (5′-TGAAT-3′ and 5′-GGAGGAAAT-3′) separated by 14 bp that match perfectly the −10 and −35 consensus sequences of ςH-dependent promoters (15, 33). To investigate whether this putative ςH promoter is functional, a 290-bp fragment containing the region from 13 nt upstream of the putative yoxA initiation codon to 153 nt upstream of the putative yoeA stop codon (yoeA is gene of unknown function located upstream of yoxA [20]) was PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA of strain PS832 using primers yoxa-P2a and yoea-3′ (Table 2). The PCR product was ligated into pCR2.1 (Invitrogen), generating plasmid pLP1, and the DNA sequence of the insert was confirmed. Digestion of plasmid pLP1 with BamHI and HindIII yielded a 236-bp fragment, which was cloned into BamHI/HindIII-digested pDG268 (3), generating plasmid pLP2 (Fig. 1A), which was then introduced into strain PS832, generating strain PS2760, which contains the yoxA-lacZ fusion at the amyE locus. Southern blot analysis confirmed that the chromosome structure of strain PS2760 was as expected (results not shown). Measurement of the β-galactosidase activity in a sporulating culture of PS2760 showed that the timing and level of expression of the yoxA-lacZ fusion in this strain were identical to those of strain PS2323, which contains a dacC-lacZ fusion at the dacC locus (data not shown). This strongly suggests that the promoter controlling dacC is located within the 236-bp BamHI/HindIII fragment in plasmid pLP2 and further supports the idea that dacC transcription depends directly on ςH. However, due to the low level of dacC transcription, we did not attempt to further localize the dacC transcription start site.

Generation and analysis of an insertional dacC mutant.

To begin to study the function of dacC, we constructed strain PS2324 containing a disrupted dacC gene by transformation of strain PS832 with plasmid pTMY4 (Fig. 1A). Plasmid pTMY4 was constructed by digesting plasmid pTMY1 with NsiI and SalI, which released an ∼400-bp fragment from within the coding region of dacC, and ligating this ∼400-bp fragment into PstI/SalI-digested plasmid pJL73 (23). Transformation of strain PS832 with plasmid pTMY4 yielded strain PS2324, in which dacC has been disrupted; Southern blot analysis verified that the genomic structure of PS2324 was as expected (data not shown).

Membranes from vegetative cells of strains PS2324 (dacC) and PS832 (wild type) and cells of the same strains harvested 2 h into sporulation (t2 of sporulation) were purified and incubated with fluorescein-hexanoic-6-aminopenicillanic acid (FLU-C6-APA), proteins were separated by SDS–10% PAGE, and PBPs were visualized with a fluorimager (FluorimagerSI; Vistra) as described previously (32). Identical PBP profiles were obtained for the two strains (results not shown), suggesting that PBP4a is present at levels too low to be detected in B. subtilis and/or has a low affinity for penicillin. Strain PS2324 grew and sporulated, its spores germinated at rates comparable to those of the wild-type strain, and dacC spores were as heat resistant as wild-type spores (results not shown). In addition, analysis of spore cortex structure by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (4, 29) showed no significant structural differences between the cortices from dacC and wild-type spores (results not shown). Thus, dacC appears to be dispensable for B. subtilis under normal growth conditions.

Expression of dacC variants in E. coli.

Given the lack of detection of the dacC gene product in B. subtilis, we overexpressed dacC in E. coli in order to determine if it indeed encodes a PBP. We also decided to overexpress several truncated forms of dacC-encoded protein to study their function and localization in E. coli. The four dacC-encoded variants overexpressed in E. coli are depicted in Fig. 1B. PBP4a corresponds to full-length dacC-encoded protein (491 residues), PBP4a-C is PBP4a lacking residues 470 to 491, PBP4a-N is PBP4a lacking residues 2 to 29, and PBP4a-NC is PBP4a lacking both residues 2 to 29 and 470 to 491. Residues 1 to 29 are found to constitute a cleavable signal peptide (see below), while residues 470 to 491 are predicted to form an amphipathic α-helix (data not shown) that may constitute a C-terminal membrane anchor commonly found in low-molecular-weight PBPs (12). For PCR amplification of the regions encoding the PBP4a variants, primers (Table 2) were as follows: PBP4a, pbpy-5′ and pbpy-3′; PBP4a-C, pbpy-5′ and pbpy-P6; PBP4a-N, pbpy-P5 and pbpy-3′; and PBP4a-NC, pbpy-P5 and pbpy-P6. PCR products were ligated into pCR 2.1 (Invitrogen), and the inserts were sequenced to confirm their identity, removed by digestion with BamHI and NdeI, ligated into BamHI/NdeI-digested pET11a (42), and used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS (42). The resulting E. coli strains were termed PS2599 (PBP4a), PS2690 (PBP4a-C), 2691 (PBP4a-N), and PS2692 (PBP4a-NC).

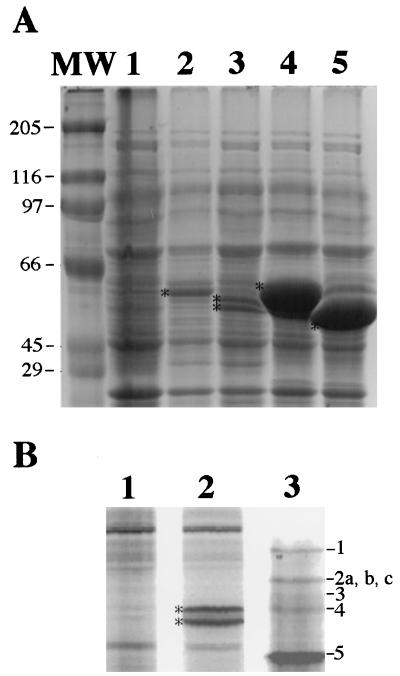

Recombinant E. coli strains were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of ∼0.5 in 50 ml of 2× YT medium (per liter: 16 g of tryptone, 10 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl) with chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml) and ampicillin (50 μg/ml), and IPTG was added to 0.5 mM. After 2 h of further incubation, samples (1 ml) from induced cultures were pelleted by centrifugation, and proteins were solubilized in 100 μl of SDS-sample buffer (21) and analyzed by SDS–10% PAGE. A strong 59-kDa band was present in the lanes containing proteins from induced PS2599 and PS2691, while lysates of induced PS2690 and PS2692 gave a doublet of 57 and 58 kDa (57–58-kDa doublet) and a strong 57-kDa band, respectively; these bands were not present in lysates of induced cells which carried only the vector (Fig. 3A). In some gels, the protein whose synthesis was induced in strain PS2599 also migrated as a 59–60-kDa doublet (Fig. 3B, lane 2), suggesting that PBP4a undergoes posttranslational processing, presumably removal of the signal sequence, and that the efficiency of processing varies from experiment to experiment. Although 57 to 59 kDa is larger than the theoretical molecular mass of PBP4a (52.9 kDa including the N-terminal signal peptide), the absence of any strong 57- to 59-kDa band in the extract from strain PS2602, which harbors only the vector (Fig. 3A, lane 1), strongly suggests that the 57- to 59-kDa bands are the PBP4a variants. To confirm this, the proteins on a gel run parallel to the one shown in Fig. 3A were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and the amino-terminal sequences of the 57- to 59-kDa bands were determined (28) (for proteins migrating as a doublet, the lower band was sequenced). The sequence obtained for the major induced bands for all PBP4a variants was AEKQD, corresponding to residues 30 to 34 of PBP4a, indicating that residues 1 to 29 constitute a signal peptide. Fractionation of sonicated cells by a high-speed centrifugation method (44) showed that most (>90%) of PBP4a, PBP4a-N, and PBP4a-C were membrane associated (presumably in the inner membrane) while PBP4a-NC was present as inclusion bodies in E. coli (data not shown). Thus, removal of either the N-terminal signal peptide or the C-terminal putative membrane anchor did not prevent PBP4a from being membrane associated; the membrane association of PBP4a-C despite the lack of the putative membrane anchor could be due to the hydrophobic character of the protein or to expression of the protein in a heterologous system. However, removal of both of these regions resulted in loss of solubility and membrane association. In addition, removal of residues 1 to 29 at the N terminus dramatically increased the amount of PBP4a protein produced in E. coli (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 4 and 5 with lanes 2 and 3), while removal of residues 470 to 491 at the C terminus of PBP4a had essentially no effect on expression levels (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 2 and 3).

FIG. 3.

Expression of dacC variants and penicillin-binding activity of PBP4a. (A) Expression of dacC variants in E. coli. Recombinant E. coli strains were grown and induced, protein was solubilized as described in the text, and 7 μl of each sample was analyzed by SDS–10% PAGE and staining with Coomassie blue. Lanes, corresponding strains, and proteins they express (parentheses) are as follows: 1, PS2602 (vector alone); 2, PS2599 (PBP4a); 3, PS2690 (PBP4a-C); 4, PS2691 (PBP4a-N); and 5, PS2692 (PBP4a-NC). Lane MW contains molecular weight markers (molecular masses are in kilodaltons). Asterisks denote migration positions of the PBP4a variants. (B) Analysis of PBPs in membranes from induced E. coli strains PS2602 (lane 1; vector alone) and PS2599 (lane 2; PBP4a). Cells were grown and induced as for panel A for 90 min, 25 ml of culture was harvested by centrifugation, membranes were isolated from sonicated cells by centrifugation (100,000 × g, 1 h) and incubated for 30 min at 30°C with 100 μM FLU-C6-APA, proteins (∼10 μg) were analyzed by SDS–10% PAGE, and PBPs were visualized with a FluorimagerSI (Vistra). A lane containing labeled PBPs from vegetative B. subtilis cells of strain PS832 (32) is shown for comparison (lane 3; the PBPs corresponding to each band are indicated on the right). Asterisks denote position of the 59–60-kDa PBP4a doublet.

The PBP4a signal peptide contains three lysines within the amino-terminal six residues, a hydrophobic core region of 15 residues that terminates with a proline, and alanine residues at positions −3, −1, and +1 relative to the cleavage site. These features are similar to those of other B. subtilis signal peptides (26), suggesting that the PBP4a variants were processed in E. coli as one might expect them to be processed in B. subtilis.

PBP4a binds penicillin.

To analyze whether recombinant PBP4a binds penicillin, membranes from cells of induced strain PS2599 or PS2602 were incubated with FLU-C6-APA, proteins were separated by SDS–10% PAGE, and bands were visualized by fluorimaging (Fig. 3B). A labeled 59–60-kDa doublet was present in membranes from strain PS2599 (Fig. 3B, lane 2) but not in labeled membranes from strain PS2602 harboring only the vector (Fig. 3B, lane 1), suggesting that the 59–60-kDa doublet is PBP4a. Comparison with FLU-C6-APA-labeled membranes from vegetative cells of strain PS832 or from cells of the same strain harvested at t2 of sporulation showed that recombinant PBP4a from E. coli membranes migrated at the same position as B. subtilis PBP4*, between PBP4 and PBP5 (Fig. 3B, lane 3, and data not shown). However, we could not detect PBP4a in membranes isolated from sporulating cells of strain PS1805, which lacks PBP4* (data not shown).

PBP4a variants affect growth and viability of E. coli.

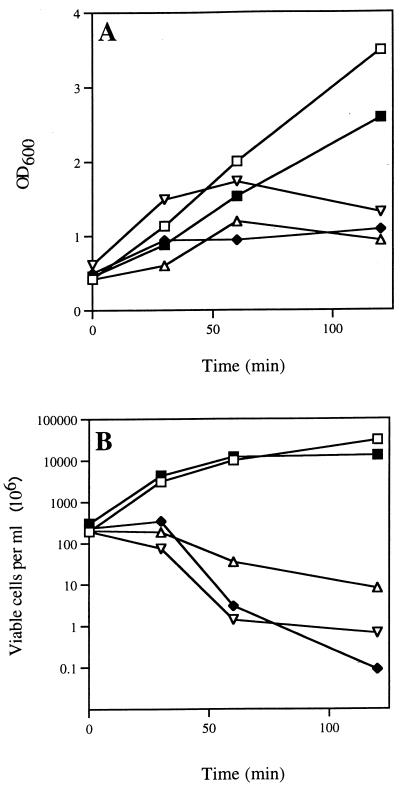

Overexpression of dacA from B. subtilis or B. stearothermophilus appears to be toxic for E. coli (10, 45). To investigate whether this was also the case for dacC, cultures of strains PS2599, PS2690, PS2691, PS2692, and the control strain PS2602 were grown to an OD600 of ∼0.5 and induced with 0.5 mM IPTG and the OD600 was monitored. All cultures continued to grow for 30 min after induction, but after 60 min, the OD600 of cells expressing PBP4a, PBP4a-C, and PBP4a-N stopped increasing, while the culture expressing PBP4a-NC continued to grow at the same rate as the strain carrying the vector alone (Fig. 4A). Consistent with these observations, determination of the number of viable cells in the induced cultures showed decreased viability of strains PS2599, PS2690, and PS2691 30 min after induction while the number of viable cells in induced cultures of strains PS2602 and PS2692 increased throughout the 120-min induction period (Fig. 4B). Thus, expression of PBP4a, PBP4a-C, and PBP4a-N is toxic for E. coli, while expression of PBP4a-NC is not. The lack of toxicity of PBP4a-NC may be related to its presence as inclusion bodies in E. coli.

FIG. 4.

Effects of PBP4a variants on growth and viability of E. coli. Recombinant E. coli strains were grown and induced with IPTG as described in the text, and the OD600 (A) and viability (B) were measured after induction. The viability was measured by plating dilutions on 2× YT agar plates containing chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1) and ampicillin (50 μg ml−1). Symbols, strains, and proteins they express (parentheses) are as follows: □, PS2602 (vector); ▿, PS2599 (PBP4a); ▵, PS2690 (PBP4a-C); ⧫, PS2691 (PBP4a-N); and ■, PS2692 (PBP4a-NC).

Enzymatic activity of PBP4a?

During the course of growth and induction of recombinant E. coli, microscopic examination of cultures expressing PBP4a, PBP4a-C, or PBP4a-N revealed the presence of lysed cells, and in cultures expressing PBP4a or PBP4a-C, spherical cells were occasionally observed (results not shown). Lysed and/or spherical cells have previously been observed in recombinant E. coli cells that overexpress proteins with dd-carboxypeptidase activity (10, 25), suggesting that PBP4a may have a similar enzymatic activity. Preliminary efforts to determine the enzymatic activity of PBP4a by reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography analysis of purified cell walls from induced recombinant E. coli (13) or by using PBP4a-NC purified from inclusion bodies from strain PS2692 in in vitro assays (1) were unsuccessful. Thus, the enzymatic activity of PBP4a, if any, remains to be determined.

In summary, we have shown that (i) dacC transcription depends strongly on transcription factor ςH and appears to be initiated from a promoter immediately upstream of the yoxA gene; (ii) disruption of dacC has no dramatic effects on B. subtilis growth, sporulation, and spore properties; and (iii) dacC encodes a membrane-bound PBP which is toxic when overexpressed in E. coli.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to A. D. Grossman, P. Stragier, A. L. Sonenshein, R. Losick, and S. Meyer for B. subtilis strains.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to P.S. (GM19698) and a postdoctoral fellowship from the Danish Natural Science Research Council to L.B.P. (9601026).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam M, Damblon C, Plaitin B, Christiaens L, Frère J-M. Chromogenic depsipeptide substrates for beta-lactamases and penicillin-sensitive DD-peptidases. Biochem J. 1990;270:525–529. doi: 10.1042/bj2700525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anagnostopoulos C, Spizizen J. Requirements for transformation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1961;81:741–746. doi: 10.1128/jb.81.5.741-746.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoniewski C, Savelli B, Stragier P. The spoIIJ gene, which regulates early developmental steps in Bacillus subtilis, belongs to a class of environmentally responsive genes. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:86–93. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.86-93.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atrih A P Z, Allmaier G, Foster S. Structural analysis of Bacillus subtilis endospore peptidoglycan and its role during differentiation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6173–6183. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6173-6183.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumberg P M, Strominger J L. Inactivation of D-alanine carboxypeptidase by penicillins and cephalosporins is not lethal in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2814–2817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.11.2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchanan C E, Gustafson A. Mutagenesis and mapping of the gene for a sporulation-specific penicillin-binding protein in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5430–5435. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5430-5435.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchanan C E, Henriques A O, Piggot P J. Cell wall changes during bacterial endospore formation. In: Ghuysen J-M, Hakenbeck R, editors. Bacterial cell wall. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1994. pp. 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan C E, Ling M-L. Isolation and sequence analysis of dacB, which encodes a sporulation-specific penicillin-binding protein in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1717–1725. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.6.1717-1725.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter H L, III, Moran C P., Jr New RNA polymerase ς factor under spo0 control in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9438–9442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Despreaux C W, Manning R F. The dacA gene of Bacillus stearothermophilus coding for D-alanine carboxypeptidase: cloning, structure and expression in Escherichia coli and Pichia pastoris. Gene. 1993;131:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90666-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghuysen J-M. Serine β-lactamases and penicillin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:37–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghuysen J-M. Molecular structures of penicillin-binding proteins and β-lactamases. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:372–380. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90614-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glauner B, Höltje J-V, Schwarz U. The composition of the murein of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10088–10095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granier B, Duez C, Lepage S, Englebert S, Dusart J, Dideberg O, van Beeumen J, Frère J-M, Ghuysen J-M. Primary and predicted secondary structures of the Actinomadura R39 extracellular DD-peptidase, a penicillin-binding protein (PBP) related to the Escherichia coli PBP4. Biochem J. 1992;282:781–788. doi: 10.1042/bj2820781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haldenwang W G. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healy J, Weir J, Smith I, Losick R. Posttranscriptional control of a sporulation regulatory gene encoding transcription factor ςH in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:477–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoch J A. The phosphorelay signal transduction pathway in the initiation of Bacillus subtilis sporulation. J Cell Biochem. 1993;51:55–61. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240510111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaacks K J, Healy J, Losick R, Grossman A D. Identification and characterization of genes controlled by the sporulation-regulatory gene spo0H in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4121–4129. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4121-4129.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korat B, Mottl H, Keck W. Penicillin-binding protein 4 of Escherichia coli: molecular cloning of the dacB gene, controlled overexpression, and alterations in murein composition. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:675–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence P J, Strominger J L. Biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan of bacterial cell walls. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:3660–3666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeDeaux J R, Grossman A D. Isolation and characterization of kinC, a gene that encodes a sensor kinase homologous to the sporulation sensor kinases KinA and KinB in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:166–175. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.166-175.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leighton T J, Doi R H. The stability of messenger ribonucleic acid during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1971;254:3189–3195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markiewicz Z, Broome-Smith J K, Schwarz U, Spratt B G. Spherical E. coli due to elevated levels of D-alanine carboxypeptidase. Nature. 1982;297:702–704. doi: 10.1038/297702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagarajan V. Protein secretion. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R L, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 713–726. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholson W L, Setlow P. Sporulation, germination, and outgrowth. In: Hardwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1990. pp. 391–450. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel-King R S, Benashski S E, Harrison A, King S M. Two functional thioredoxins containing redox-sensitive vicinal dithiols from the chlamydomonas outer dynein arm. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6283–6291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popham D L, Helin J, Costello C E, Setlow P. Analysis of the peptidoglycan structure of Bacillus subtilis endospores. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6451–6458. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6451-6458.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popham D L, Illades-Aguiar B, Setlow P. The Bacillus subtilis dacB gene, encoding penicillin-binding protein 5*, is part of a three-gene operon required for proper spore cortex synthesis and spore core dehydration. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4721–4729. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4721-4729.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popham D L, Setlow P. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and regulation of the Bacillus subtilis pbpE operon, which codes for penicillin-binding protein 4* and an apparent amino acid racemase. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2917–2925. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2917-2925.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Popham D L, Setlow P. Phenotypes of Bacillus subtilis mutants lacking multiple class A high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2079–2085. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.7.2079-2085.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Predich M, Nair G, Smith I. Bacillus subtilis early sporulation genes kinA, spo0F, and spo0A are transcribed by the RNA polymerase containing ςH. J Bacteriol. 1990;174:2771–2778. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.9.2771-2778.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robertson J B, Gocht M, Marahiel M A, Zuber P. AbrB, a regulator of gene expression in Bacillus, interacts with the transcription initiation regions of a sporulation gene and an antibiotic biosynthesis gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8457–8461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaeffer P, Millet J, Aubert J. Catabolite repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;54:704–711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.3.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schuch R, Piggot P J. The dacF-spoIIA operon of Bacillus subtilis, encoding ςF, is autoregulated. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4104–4110. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.4104-4110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simpson E B, Hancock T W, Buchanan C E. Transcriptional control of dacB, which encodes a major sporulation-specific penicillin-binding protein. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7767–7769. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7767-7769.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slack F J, Serror P, Joyce E, Sonenshein A L. A gene required for nutritional repression of the Bacillus subtilis dipeptide permease operon. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:689–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sowell M O, Buchanan C E. Changes in penicillin-binding proteins during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:1331–1337. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.3.1331-1337.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinmetz M, Richter R. Plasmids designed to alter the antibiotic resistance expressed by insertion mutations in Bacillus subtilis, through in vivo recombination. Gene. 1994;142:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strauch M, Webb V, Spiegelman G, Hoch J A. The Spo0A protein of Bacillus subtilis is a repressor of the abrB gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1801–1805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun D, Cabrera-Martinez R M, Setlow P. Control of transcription of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIIG gene, which codes for the forespore-specific transcription factor ςG. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2977–2984. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2977-2984.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thorstenson Y R, Zhang Y, Olson P S, Mascarenhas D. Leaderless polypeptides efficiently extracted from whole cells by osmotic shock. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5333–5339. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5333-5339.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Todd J A, Roberts A N, Johnstone K, Piggot P J, Winter G, Ellar D J. Reduced heat resistance of mutant spores after cloning and mutagenesis of the Bacillus subtilis gene encoding penicillin-binding protein 5. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:257–264. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.257-264.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tognoni A, Franchi E, Magistrelli C, Colombo E, Cosmina P, Grandi G. A putative new peptide synthase operon in Bacillus subtilis: partial characterization. Microbiology. 1995;141:645–648. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-3-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Umbreit J N, Strominger J L. D-alanine carboxypeptidase from Bacillus subtilis membranes. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:6759–6766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weir J, Predich M, Dubnau E, Nair G, Smith I. Regulation of spo0H, a gene coding for the Bacillus subtilis ςH factor. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:521–529. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.521-529.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu J-J, Schuch R, Piggot P J. Characterization of a Bacillus subtilis sporulation operon that includes genes for an RNA polymerase ς factor and for a putative dd-carboxypeptidase. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4885–4892. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.4885-4892.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yansura D G, Henner D J. Use of Escherichia coli lac repressor and operator to control gene expression in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:439–443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]