Summary

China’s private hospital market has experienced rapid growth over the last decade, with private hospitals now outnumbering public hospitals by a factor of two. This policy analysis uses available data and existing literature to analyze China’s rapidly changing hospital market, identify key challenges resulting from rapid private hospital growth, and present recommendations to ensure future sustainable private hospital development in the country. Our analysis shows that while private hospitals outnumber public hospitals, outpatient visits and hospitalizations remain higher among public hospitals, while per-patient expenditure remains higher among private hospitals. Key challenges to private hospital development include limited government financial support, high tax burdens, difficulty in workforce recruitment and retainment, poor government regulation and oversight, and dissipating public trust. Recommendations to address these challenges include opening government contract bidding to private hospitals, creating a system that allows private hospitals to enter national health insurance schemes, reducing tax pressure on private hospitals, defining a legal system for market entry and exit of private hospitals, improving a system of supervision, and monitoring and evaluation of private hospital operation and performance.

Keywords: China, Private hospitals, Private healthcare, Health policy

Introduction

The private health sector can be defined as the collection of actors involved in the provision of healthcare who are neither owned nor directly controlled by government entities.1 Over recent decades, the size and role of the private health sector has grown substantially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to include the direct provision of health services, access to medicines, infrastructure, technology, and workforce trainings.2,3 As a result the private health sector has become increasingly important to achieving universal health coverage (UHC), especially as more health consumers turn toward the private sector for their needs, and governments have had to formulate and integrate new policies that define a role for the private health sector in the attainment of UHC goals.4

While numerous LMICs have seen their private health sector steadily grow over many decades, thus giving their governments time to develop and adopt new policies necessary for regulating and managing a mixed health system, China’s private health sector has experienced rapid growth in a comparatively short time. China’s private health sector experienced significant development following a new phase of healthcare reform that began in 2009.5 These reforms, in addition to a growing demand for healthcare, resulted in the number of private hospitals in the country surpassing the number of public hospitals by the year 2015 and the proportion of private hospital beds nationwide increasing from 12.4% in 2011 to 21.4% in 2016.6 The rapidly changing health sector landscape in China has significant implications for healthcare service provision, quality of care, and hospital regulation and management.

The goal of this policy analysis is to use available data and existing literature to analyze China’s rapidly changing health sector. Specifically, we aim to describe the changing landscape of China’s hospital market during the decade spanning 2011 to 2021, present the implications of this changing landscape, identify key challenges associated with the development, management, and regulation of private hospitals in the country, and propose policy recommendations based on key findings and lessons learned from other countries. Such information may prove useful to policymakers attempting to maximize the effectiveness and sustainability of the private hospital sector’s development in China. As mentioned above, 2009 marked the start of new healthcare reforms in China. Since the implementation of the healthcare reform, China has seen many progresses in achieving its policy goals, such as increased population coverage of health insurance and improved access to public health services and essential medicines. However, reforming public hospitals, as one of the important policy goals set up in 2009, has not been satisfactory due to many reasons including some invested interests of key stakeholders. Developing private hospitals, as supplementary to public hospital services, has been seen to fill gaps in meeting the needs of and demands for healthcare of the Chinese population.

This paper focuses on the ten-year period spanning 2011 to 2021 because such reforms likely required some initial time to effect change. Nonetheless, as reported by others, private hospital growth did occur in China between 2009 and 2011 albeit at a slower pace than from 2011 to 2021.5 Importantly, we recognize that online-based private healthcare is rapidly increasing in China, but such care is beyond the scope of this study.

China’s changing hospital landscape

The adaptation of so-called socialist marketization in China has resulted in the market-driven operation of hospitals, whereby public hospitals operate under a de facto for-profit system which can be traced back to economic reforms enacted during the early 1980’s.7 At this time, the central government substantially reduced investment in public healthcare—the percent of total health expenditure funded by the central government fell from 32% in 1978 to 14% in 20008—and made the provision and financing of healthcare services the responsibility of local governments and individuals.9 As a result, healthcare facilities became primarily reliant on the sale of healthcare services and medicines for the generation of revenue.10 However, while private healthcare clinics began to crop up during the 1980’s and 90’s, large scale growth did not begin until the early 2000’s when the central government implemented a set of concerted policies, such as Opinions on Deepening the Reform of the Medical and Health System and Opinions on Further Encouraging and Guiding Social Capital to Establish Medical Institutions, to promote private investment in the healthcare sector.11 Private hospital growth was further spurred in 2009 when the central government passed a USD$125 billion reform to increase access and affordability of basic healthcare across the country. Most of this investment has gone towards subsidizing the people living in rural China to participate in health insurance, supporting the provision of essential public health services, and increasing development and operation of grass-root level health facilities at the county and township levels. This reform encouraged private hospital entry into the healthcare market to create competition intended to stimulate an increase in efficiency and quality among public hospitals.12

Reforms implemented by the Chinese central government over the last two decades have had a clear impact on private hospital growth in the country. Table 1 shows how the number of hospitals, personnel, and beds have changed within the private and public healthcare sector between 2011 and 2021. From 2011 to 2021, the number of private hospitals increased by 193.4%, employed private hospital personnel increased by 140.4%, and private hospital beds increased by 378.2%. In contrast, the number of public hospitals decreased by 12.8%, employed public hospital personnel increased by 4.6%, and public hospital beds increased by 60.6%. The decline of public hospitals in China over the past decade is largely due to two reasons: 1) some primary and secondary hospitals have been merged into tertiary hospitals to form medical groups; and 2) some public hospitals who were owned by state enterprises have been regrouped as non-public hospitals. In 2011 private and public hospitals accounted for 38.4% and 61.6% of all hospitals in China, respectively (Table 1). By 2021, these numbers nearly reversed with private hospitals outnumbering public hospitals by a ratio of 2.1–1.0 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of hospitals, personnel, and beds for private vs. public hospitals in China (2011–2021).

| Yeara | Number |

Personnel |

Beds |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | Public: private ratio | Public | Private | Public: private ratio | Public | Private | Public: private ratio | |

| 2011 | 13,539 | 8440 | 1.60 | 5,284,427 | 661,050 | 7.99 | 3,243,658 | 461,460 | 7.03 |

| 2012 | 13,384 | 9786 | 1.37 | 3,555,279 | 502,361 | 7.08 | 3,579,309 | 582,177 | 6.15 |

| 2013 | 13,396 | 11,313 | 1.18 | 6,060,885 | 831,599 | 7.29 | 3,865,385 | 713,216 | 5.42 |

| 2014 | 13,314 | 12,546 | 1.06 | 4,080,345 | 661,332 | 6.17 | 4,125,715 | 835,446 | 4.94 |

| 2015 | 13,069 | 14,518 | 0.90 | 4,276,938 | 794,213 | 5.39 | 4,296,401 | 1,034,179 | 4.15 |

| 2016 | 12,708 | 16,432 | 0.77 | 4,491,172 | 923,894 | 4.86 | 4,455,238 | 1,233,637 | 3.61 |

| 2017 | 12,297 | 18,759 | 0.66 | 4,684,677 | 1,100,035 | 4.26 | 4,631,146 | 1,489,338 | 3.11 |

| 2018 | 12,032 | 20,977 | 0.57 | 1,823,722 | 859,261 | 2.12 | 4,802,171 | 1,717,578 | 2.80 |

| 2019 | 11,930 | 22,424 | 0.53 | 5,098,390 | 1,389,107 | 3.67 | 4,975,633 | 1,890,913 | 2.63 |

| 2020 | 11,870 | 23,524 | 0.50 | 5,292,442 | 1,482,322 | 3.57 | 5,090,558 | 2,040,628 | 2.49 |

| 2021 | 11,804 | 24,766 | 0.48 | 5,526,526 | 1,588,939 | 3.48 | 5,207,727 | 2,206,501 | 2.36 |

Despite having experienced rapid growth over the last two decades and despite outnumbering public hospitals, private hospitals still have not matched the capacity level of health service utilization seen among public hospitals likely because of an overall lower number of personnel and beds. Table 2 shows how service volume has changed among private and public hospitals between 2011 and 2021. From 2011 to 2021, the number of outpatient visits to private hospitals increased by 197.1% and the number of private hospital hospitalizations increased by 257.7%. In contrast, the number of visits to public hospitals increased by 59.4% and the number of public hospital hospitalizations increased by 69.0%. However, in 2021, public hospitals still accounted for the majority of both outpatient visits (84.2%) and hospitalizations (81.4%) in the country (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of outpatient visits and number of hospitalizations for private vs. public hospitals in China (2011–2021).

| Yeara | Number of outpatient visits (thousands) |

Number of hospitalizations (thousands) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public |

Private |

Public |

Private |

|||||

| Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | Number | Proportion (%) | |

| 2011 | 205,254 | 90.9 | 20,629 | 9.1 | 9707 | 90.3 | 1047 | 9.7 |

| 2012 | 228,866 | 90.1 | 25,295 | 10.0 | 11,331 | 89.0 | 1396 | 11.0 |

| 2013 | 245,510 | 89.5 | 28,667 | 10.5 | 12,315 | 87.9 | 1692 | 12.1 |

| 2014 | 264,741 | 89.1 | 32,465 | 10.9 | 13,414 | 87.3 | 1960 | 12.8 |

| 2015 | 271,243 | 88.0 | 37,120 | 12.0 | 13,721 | 85.3 | 2365 | 14.7 |

| 2016 | 284,771 | 87.1 | 42,184 | 12.9 | 14,750 | 84.2 | 2777 | 15.8 |

| 2017 | 295,201 | 85.8 | 48,690 | 14.2 | 15,594 | 82.4 | 3320 | 17.6 |

| 2018 | 305,123 | 85.3 | 52,613 | 14.7 | 16,351 | 81.7 | 3665 | 18.3 |

| 2019 | 327,232 | 85.2 | 57,008 | 14.8 | 17,487 | 82.6 | 3695 | 17.5 |

| 2020 | 279,193 | 84.0 | 53,094 | 16.0 | 14,835 | 80.8 | 3516 | 19.2 |

| 2021 | 327,089 | 84.2 | 61,290 | 15.8 | 16,409 | 81.4 | 3745 | 18.6 |

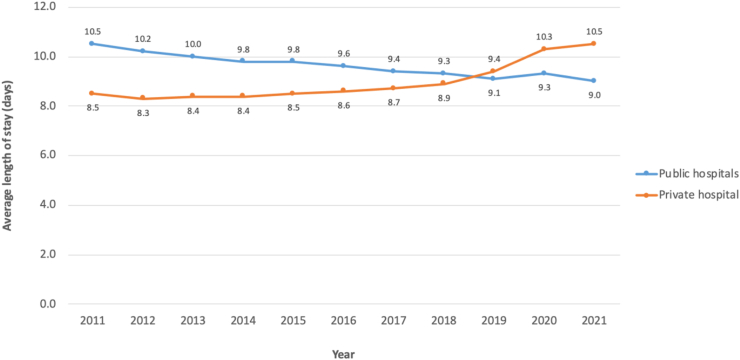

Interestingly, as the number of personnel and beds have increased among both private and public hospitals, the average length of stay (LOS) has increased among private hospitals but decreased among public hospitals. Among private hospitals, the average LOS increased from 8.5 days in 2011 to 10.5 days in 2021 (Fig. 1). Among public hospitals the average LOS decreased from 10.5 days in 2011 to 9.0 days in 2021 (Fig. 1). The decreasing trend in average LOS among public hospitals can be explained by government evaluations and controlling measures put in place by health insurance management agencies. Turnover efficiency is one of many indicators used by the government to evaluate and rank public hospitals and therefore determine funding allocations. Public hospitals are therefore incentivized to have high turnover rates and thus a lower LOS per patient. Conversely, private hospitals, to a large extent, do not face this pressure because they are not funded primarily by the government and or government supported health insurance. Moreover, recent government policies since 2009 frame the private health sector as a supplement to the public health sector and thus promote the private sector’s uptake of services not commonly provided by public hospitals such as rehabilitation and hospice care.15 These services require longer hospital stays which may explain the increasing trend in average LOS among private hospitals. More generally, some private hospitals provide advanced medical services that tend to require longer stays than the primary care services common to most public hospitals. Unfortunately, the data presented in this analysis is not granular enough to comment further on the relationship between severity of admitted cases and LOS in public vs. private hospitals. Lastly, the average bed occupancy rate across public hospitals over the last decade has remained 20–30% higher than the average bed occupancy rate across private hospitals. In 2021, the average bed occupancy rate across public and private hospitals was 80.3% and 59.9%, respectively, suggesting that public hospitals had higher efficiency than private hospitals. This difference further suggests that public hospitals are incentivized by government funding or evaluation to maintain high bed occupancy and high patient turnover.

Fig. 1.

Average length of stay at private vs. public hospitals in China (2011–2021). Data for years 2011–2012 and 2018–2021 are from the China Health Statistical Yearbook.13 Data for years 2013–2017 are from the China Health Family Planning Statistics Yearbook.14

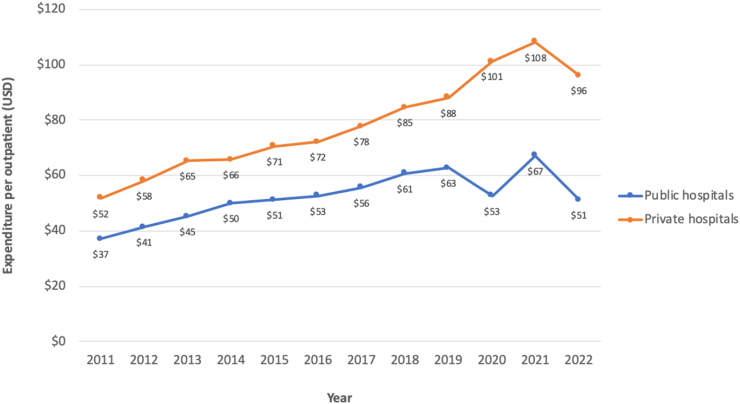

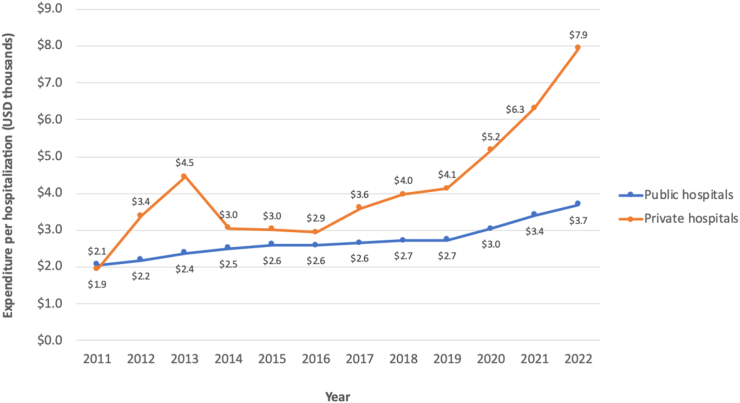

Private hospital growth has also been accompanied by an increase in expenditure. Fig. 2 shows the average expenditure per outpatient visit across private and public hospitals in Shanghai. Shanghai is currently pioneering the development and reform of private hospitals in China and therefore serves as a case-study for what future trends in private hospital growth and expenditure could look like, as other parts of the country experience local economic growth. Private hospital expenditure per outpatient visit has been steadily increasing over the last decade from USD$52 in 2011 to USD$96 in 2022. Public hospital expenditure per outpatient visit has also increased, albeit at a slower rate, from USD$37 in 2011 to USD$51 in 2022. Expenditure per hospitalization has followed a similar trend. Fig. 3 shows the average expenditure per hospitalization across private and public hospitals in Shanghai. Private hospital expenditure per hospitalization has increased substantially from USD$1944 in 2011 to USD$7928 in 2022. Public hospital expenditure per hospitalization has seen a much lower increase from USD$2057 in 2011 to USD$3691 in 2022. At the national level, average public hospital expenditure per outpatient and hospitalization is lower than what is seen in Shanghai. Across all of China, average public hospital expenditure per outpatient increased from USD$32 in 2011 to USD$41 in 2018.17 Similarly, average public hospital expenditure per hospitalization increased from USD$1232 in 2011 to USD$1505 in 2018.17 Average private hospital expenditure per outpatient and hospitalization is also expected to be lower at the national level relative to Shanghai given that Shanghai is one of China’s wealthiest municipalities.

Fig. 2.

Expenditure per outpatient in private vs. public hospitals in Shanghai (2011–2022). Data is from the Shanghai Health Statistical Bulletin.16

Fig. 3.

Expenditure per hospitalization in private vs. public hospitals in Shanghai (2011–2022). Data is from the Shanghai Health Statistical Bulletin.16

It is important to note that our analysis of China’s changing hospital landscape focuses on supply-side factors such as hospital numbers, personnel, and beds and does not include demand-side factors. Demand side factors include, for example, the negative impact of COVID-19 on the local economy whereby the general public may shift their use of the health system away from private hospitals which have higher per-patient costs compared to public hospitals. In addition, COVID-19 may further increase people’s preference for outpatient care which is more available in public than private hospitals. By contrast, increased access to health insurance, and removal of restrictions on the use of public insurance for private healthcare, might stimulate further use of private hospitals and growth of the sector. We acknowledge the exclusion of demand-side factors as a limitation of our analysis.

Key challenges to private hospital development in China

In this section, we use Roberts et al., 2003 health system performance framework to identify and analyze key challenges associated with private hospitals in China. The framework proposed by Roberts et al., 2003 focuses on five “control knobs” as a means to achieve desired health system performance outcomes such as efficiency, quality, and access, as well as desired long-term goals including reduced disease burden in the target population, higher customer satisfaction, and improved risk protection.18 The five “control knobs” are financing, payment, organization, regulation, and behavior. A summary of these key challenges can be found in Box 1.

Text Box 1. Summary of key challenges to private hospital development.

-

•

Financing and payment—Private funders are more likely to cater to higher income populations in larger cities due to the prospect of larger and more reliable returns on investment, health insurance schemes in China do not cover healthcare services provided by private hospitals, and private hospitals face a higher tax burden compared to public hospitals.

-

•

Organization: building and retaining a healthcare workforce—High staff turnover rates within private hospitals create imbalances in skill, experience, and coherence within medical teams thereby reducing efficiency and quality of care.

-

•

Regulation and oversight—The absence of mechanisms to enforce regulation and oversight policies within private hospitals has increased the rates of provider induced demand and led to vague criteria and a lack of standards to guide the hiring of clinical practitioners.

-

•

Behavior: improving public trust—Public trust in private healthcare facilities remains low, and is possibly driven by poor experiences, travel distance, waiting times, or out-of-pocket costs. Efforts are needed to build public trust in private hospitals.

Financing and payment

Although China’s private hospital market has experienced significant expansion over the last decade, the vision of private healthcare as a supplement to public healthcare as suggested by government policies may not be fully materialized due to poor financial prospects for private investors. The central government wants to grow private investments, especially in rural areas, to provide underserved populations with greater access to healthcare.19 However, private investors are often more interested in catering to higher income populations in large cities due to the prospect of larger and more reliable returns on investment.19 Financial support by the government in the form of subsidies to lower the risk of investment may therefore be necessary to incentivize and sustain private investment in rural areas with underserved communities. In addition, public health insurance schemes in China often do not cover healthcare services provided by private facilities. Public health insurance schemes established since the late 1990’s—the Urban Employee Insurance, Urban Basic Residents Insurance, New Rural Medical Cooperative Scheme, and Medical Assistance for the Poor Program—collectively covered 95% of the national population by 2011.20 However, these schemes are pooled at the county or municipality level and, consequently, offer health benefit packages and financial risk protection that vary across both insurance type and region.21 Plans to achieve equitable healthcare coverage across all of China, and which make use of the private sector, may therefore require consolidating the funding pools of current public insurance schemes and exploring a means to insure care received from private facilities.22,23

Private hospitals in China also face a higher tax burden than public hospitals. While public hospitals in China still receive government funding, albeit at lower levels than over the last few decades, private hospitals do not receive government subsidies and must pay taxes based on government policies. These tax policies vary substantially depending on the type of private hospital. Non-profit private hospitals must use healthcare service prices established by the government whereas for-profit private hospitals can set their own prices but must pay taxes as stipulated by the government.24 These taxes include value-added tax, corporate income tax, and value-added tax on imported equipment. Public hospitals, on the other hand, are entitled to tax exemptions for imported equipment, medicines, and other products. Many private hospitals are therefore at a disadvantage within the competitive healthcare market. Many private hospitals in China, for example, have been unable to generate enough profit to stay afloat during their early-stage operations.25 A lack of clear regulations regarding income tax on hospitals with mixed ownership (e.g., public-private partnership) also hinders private investment into the healthcare market.26

Overall, tax policies developed by the Chinese government stipulate that all revenue generated from healthcare services are taxable for for-profit private hospitals. For non-profit private hospitals, revenue generated from healthcare services with prices set by the government pricing bureau are not taxable. Only revenue generated from services priced by the non-profit hospitals themselves are taxable. Non-profit private hospitals also enjoy unique favorable tax policies including no tax on land and property purchases, imported high-technology equipment from overseas, or the sale of self-made medicines approved by government agencies. For-profit private hospitals may apply for these same tax exemptions during the first three years of their operation. However, after the three-year grace period, for-profit private hospitals must pay taxes on nearly every revenue stream and transaction. To alleviate their high tax burden, some for-profit private hospitals opt to transition into non-profit hospitals after their three-year tax exemption period.27 Other for-profit hospitals register as non-profit entities to avoid taxation and then divert profits through related-party transactions or by directly distributing dividends to investors, leading to the emergence of pseudo non-profit hospitals.28 These misbehaviors have created challenges to hospital administration, regulation, and management. A comprehensive pilot program was implemented in 2016 to replace the business tax with the value-added tax in China, and transit previously taxable items under the business tax to the value-added tax regime, thereby preventing double taxation and reducing the overall tax burden on for-profit private hospitals.29

Organization: building and retaining a healthcare workforce

An additional challenge to the continued growth of private healthcare in China is the private healthcare workforce. Public and private hospitals in China have been shown to have a similar average number of employees per patient bed.30 However, the sociodemographic makeup of the public and private healthcare workforce varies substantially. In a survey of 376 public and private Chinese hospitals covering 83,413 healthcare workers, private hospitals had proportionally fewer staff with doctoral, masters, and undergraduate degrees.11 In addition, private hospitals had a significantly higher percentage of physicians over the age of 60 years and a significantly higher percentage of nurses under the age of 30 years compared to public hospitals.11 The skewed educational and age distributions of the private hospital workforce, relative to public hospitals, hint at the possibility of imbalances in skill, experience, and coherence within medical teams as well as high staff turnover rates. While such an imbalance would not necessarily reduce the quality of care or impact health outcomes, it may contribute to unfavorable public perceptions of private hospital healthcare quality. Furthermore, high staff turnover rates may be driven by a lack of technical and professional development opportunities that are offered within the public hospital management structure.11 Young healthcare workers just entering the market, for example, may not be incentivized to build their careers within a private hospital system with limited opportunities for growth. Ultimately, the private hospital management system may need to borrow performance management, personnel management, and medical quality control frameworks from the public sector to better build and retain a robust and reliable workforce.31, 32, 33

Regulation and oversight

Since 2018, a series of policies have been implemented to expedite the accreditation process for the establishment of private hospitals in China. Policies pertaining to the regulation and oversight of private hospitals, however, remain sparse. Moreover, regulation and oversight policies that have been developed for private hospitals have not been effectively enforced.34,35 A lack of enforcement has led to high rates of provider induced demand within private hospitals as well as vague criteria and undefined standards to guide the hiring of clinical practitioners. Consequently, there is an urgent need for stringent regulation and oversight to govern future expansion of China’s private hospital market.

Currently, private hospitals in China are regulated as both enterprises and medical institutions.36,37 Under enterprise regulations, private hospitals are subject to supervision by government departments such as industry and commerce, taxation, pricing, and public security. Under medical institution regulations, private hospitals are subject to oversight by health administrative authorities. The legal classification of private hospitals as both enterprises and medical institutions therefore creates ambiguity with regard to the accountability and responsibilities of the different regulatory agencies overseeing private hospital development and operations.38 Such ambiguity has prevented the establishment of a sustainable long-term private hospital oversight mechanism. Rather, current private hospital regulation and oversight focuses primarily on the accreditation process with little emphasis on routine supervision and monitoring.

Under current private hospital regulation and oversight mechanisms, government authorities use a demerit scoring system for in-situ supervision and semi-annual supervision. However, this has allowed some private hospitals to predict and plan for upcoming inspections without implementing lasting change.39 For example, some private hospitals engage in activities beyond their registered scope of practice and employ individuals who are not authorized to perform these activities. During inspections by health authorities, these hospitals might borrow medical licenses from authorized employees at other hospitals and use this as proof of their own capacity to perform said activities. In addition, the accounting systems of private hospitals are not unified, and information disclosure systems remain underdeveloped, which further complicates the government’s ability to audit the financial operations of private hospitals.40,41

Lastly, regarding healthcare insurance oversight, certain private hospitals engage in fraudulent practices to take advantage of insurance funds. These fraudulent practices include false treatments (using fabricated inpatient records, diagnosis certificates, and examination reports), admitting patients who have no real medical reason for being admitted, and using deceptive marketing tactics (attracting patients for insurance fraud through services like free transportation, meal subsidies, and free check-ups). The current healthcare insurance regulatory system has its shortcomings, with insufficient regulatory measures and methods, and regulatory capabilities still need improvement. In addition, there is widespread corruption in China’s health sector in which doctors and hospital managers from both public and private hospitals receive illegal kickbacks from the pharmaceutical and other medical industries. The enforcement of relevant regulations and the investigation and prosecution of these illegal behaviors have recently been undertaken by relevant authorities.

Behavior: improving public trust

Continued growth of China’s private hospital market may also be hindered by public trust in private healthcare facilities. Previous studies suggest that no significant differences in all-cause inpatient mortality exist in China between public and private hospitals of comparable size and accreditation levels.30 Other studies have demonstrated that private hospitals have significantly higher levels of disease-specific mortality compared to public hospitals.42 Regardless, public trust in private healthcare remains low. In a survey administered to 4156 participants sampled from the entirety of mainland China, only 6.1% showed a preference for private hospitals, whereas the remaining 93.9% showed a preference for general public hospitals, specialized public hospitals, or community hospitals.43 In addition, a discrete choice experiment carried out in Fujian province involving 507 respondents found that urban residents show a high disposition for public healthcare providers, whereas rural residents were found to be indifferent in their preference for public vs. private healthcare providers.44 Similarly, in a questionnaire administered to 1500 participants sampled from ten districts across Shenzhen, only 1.7% said they would seek care from a private medical institution if unwell, and no participants chose private medical institutions as their first choice for care.45 There appears to be a clear preference among residents across China for care administered by public institutions. Whether this preference is largely driven by past experiences, distance to the hospital, waiting times, or out-of-pocket costs remains unclear. Nonetheless, efforts are clearly needed to build people’s trust in private institutions so that the private health sector may be able to make a meaningful contribution to universal health coverage in China.

Policy options to make private hospitals more effective and sustainable

Given the challenges presented above, we propose policy solutions that the Chinese government may consider to enable private hospitals to function in a more effective and sustainable way. Furthermore, in line with the government’s intention of using private healthcare to supplement public healthcare, these policy solutions are intended to strengthen private hospital efficiency, financing, regulation, and quality and therefore delivery of health services to the public.

Government needs to actively engage private hospitals to reshape the public-private healthcare landscape

Globally, the traditional model dominated by public hospitals is being replaced by a government procurement model based on value-based strategic healthcare purchasing.46 According to the State Council General Office's Guidance on Government Purchasing Services from Social Forces, the Notice on Budget Management Issues Related to Government Purchasing Services, and the Decision on Deepening Budget Management Reform by the State Council, funds required for purchasing public health services should be included in the fiscal budget.47, 48, 49 The government should use these resources to open contract bidding and negotiations on equal terms with both public and private hospitals. Agreements should cover medical service packages, service standards, service quality, budget allocations, payment mechanisms, and performance evaluations. Performance evaluation results should determine whether to maintain or terminate contracting relationships and whether to provide fiscal subsidies. This approach encourages contracted hospitals to improve financial transparency, enhance services, control costs, and standardize medical practices. Through government service procurement, eligible private hospitals would have the support to offer local public health and basic medical services as well as directives defined by the government. Private hospitals complying with government directives should receive financial compensation on par with public hospitals in addition to the tax exemptions already received on revenue from government priced services. Public and private hospitals will compete to provide cost-effective basic medical services and receive corresponding fiscal compensation.

Developing appropriate taxation policy to support sustainable development of for-profit private hospitals

Taxation is an important economic lever for regulating resource allocation. Tax policies not only affect a hospital's competitiveness but also influence which medical service projects investors choose to fund. Currently, China classifies medical institutions as non-profit or for-profit. While for-profit private hospitals seek profits, they still bear the social responsibility of providing basic medical care. When determining taxation rates, for-profit private hospitals should, therefore, not be equated with general for-profit enterprises. Tax rates for for-profit private hospitals should be preferential. Moreover, to prevent hospitals from transferring the tax burden to health insurance schemes and patients under existing pricing and fiscal compensation conditions, the corporate income tax rate for for-profit private hospitals should be reduced. The depreciation of high-tech medical equipment should be included in costs, and corresponding tax exemptions should be applied to medical technology investments. In addition, the current three-year tax exemption period does not effectively alleviate the financial pressure on for-profit private hospitals during their start-up phase. The tax exemption period for newly established for-profit private hospitals should be extended, with no corporate income tax during initial years followed by a gradual stepwise increase in tax rates. This tax leverage will encourage social capital investments in the healthcare industry.

Employing flexible and effective human resource policies to incentivize health professionals to work for private hospitals

Private hospitals are not required to follow government rules and guidelines pertaining to the recruitment of health professionals at public hospitals. Hence, private hospitals may adopt more flexible policies. For example, doctors and other professionals, especially females, in other countries often work as part-time employees, owing to the needs of taking care of their young families. Human resource policies within Chinese public hospitals often do not permit part-time employment, however no law in China prevents private hospitals from doing so. In so doing, private hospitals may be able to recruit qualified doctors who otherwise stay at home to look after their young families, or who won’t be able to work as full-time employees, owing to their health status or seeking semi-retirement, etc. In addition, private hospitals should also create career development opportunities for young health professionals (e.g., establishing mid-career development fellowships to allow junior health professionals to spend some time at teaching hospitals and/or respected tertiary hospitals to advance their skills and clinical experiences). By doing so, private hospitals can attract and retain more young health professionals.

Strengthen entry regulations for private hospitals and establish exit rules

A legal system for market entry of private hospitals should be established promptly. This system should define the scope of work, entry conditions, and exit regulations for private hospitals in the market. Regulating entry of private hospitals into the market will not only encourage and promote market entry but also standardize market entry behavior. At the macro level, the law should explicitly list market entry conditions for private hospitals in legislation and complement the enumerated terms with safety net provisions to address any deficiencies in the listed terms. At the micro level, detailed regulations should be formulated for market entry conditions based on whether private hospitals provide public healthcare services or private medical services and according to the nature of their medical service products. Ultimately, clear market entry conditions will promote smooth entry of private hospitals into the market and prevent fraudulent behaviors that threaten patient safety. Legislation should also be strengthened to establish exit rules for private hospitals in the market. Such legislation should specify exit conditions, procedures for exit, legal responsibilities for exit, and property attribution. A combination of voluntary exit and forced exit should be adopted to further regulate the operations of private hospitals.

Enhance performance evaluation management to improve the credibility of private hospitals

Sustainable development of private hospitals requires strict adherence and compliance with legal operations. To achieve this, a standard for integrity in medical practice should be established. For example, the Basic Standards for Establishing National Honest Private Hospitals formulated by the Private Hospitals Management Branch of the Chinese Hospital Association in 2016 includes "establishment admission standards" and "establishment assessment and evaluation standards." The "establishment admission standards" consist of seventeen assessment points that operate on a veto system. If any assessment point is not met, the hospital loses its qualification for admission. Credit ratings should be used to compel private hospitals to adhere to medical service practices and enhance their credibility in the eyes of the general public. Simultaneously, credit rating standards may help identify private hospitals with strong technical quality, influential brands, and high social credibility, thereby setting industry benchmarks and promoting sustainable development of private hospitals. Relevant government departments should also strengthen supervision and inspection of private hospital medical practices and establish a long-term inspection mechanism that focuses on adherence to a hospital’s scope of medical practice, employment of qualified medical personnel, appropriate medical advertising, and standardized diagnosis and treatment procedures. Long-term inspections may also be supplemented by unannounced audits. An adverse point management system should also be established to assign points for different levels of violations by private hospitals and their employees. Public disclosure of such information would further promote adherence to relevant standards of operation.

Targeted policies to support and guide the integration of private medical institutions into the national health insurance system

To date, China has recorded national healthcare insurance coverage rates up to 95%. However, many private hospitals do not have a designated health insurance status, which prevents patients from receiving reimbursements for medical services. A lack of financial reimbursement to patients can lead to patient attrition and subsequently financial losses for private hospitals. To combat this, the relevant departments of health insurance schemes should treat public and private hospitals equally when establishing the Assessment and Management Measures for Designated Medical Institutions. In addition, detailed guidelines and approval procedures for including private hospitals in the national health insurance network should be developed. Similarly, private hospitals that meet health insurance inclusion criteria should be included from the start of their operations and be eligible for health insurance reimbursement. Any reasons for a hospital not meeting the inclusion criteria should be disclosed along with guidance on how to meet the criteria. Private and public hospitals offering the same scope of services should also have clear and equal health insurance policies. For private hospitals, timely recovery of health insurance compensation funds significantly affects their financial risk. If the rate of health insurance compensation fund recovery is too slow, it increases financial pressure on private hospitals hindering their operations. Government departments should therefore formulate development plans for private hospitals, improve administrative approval procedures, and provide guidance for health insurance compensation.

A lack of government financial support for the many private for-profit hospitals in China can incentivize fraudulent behavior. To combat this, medical resource allocation should be coordinated at the national and regional levels, taking into account unique characteristics and medical capabilities of individual private hospitals. Guidance should also be offered to help private hospitals integrate into the national health insurance system. Simultaneously, the capacity of the health insurance fund should be considered. Strict approval of health insurance qualifications for private hospitals should be implemented using a robust review process. Furthermore, efforts should be made to expedite the improvement of the health insurance law enforcement system, revise relevant laws and regulations such as the Social Insurance Law according to the current situation of the medical market, clarify the enforcement powers of health insurance agencies over designated medical institutions, and refine related provisions. Lastly, different degrees of punishment should be imposed on health insurance violations based on different violation circumstances. For serious violations, for example, stricter penalties should be applied.

Conclusion

The private hospital market in China has experienced clear and rapid growth, especially since the 2010s, but challenges remain regarding private hospital financing, regulation and oversight, workforce retainment, and public trust. To ensure future growth of the private hospital market in China is sustainable additional policies are likely necessary which open government contract bidding to private hospitals, reduce tax pressure on private hospitals, define a legal system for market entry of private hospitals with clear entry and exit conditions, improve private hospital performance evaluation, and create a system that allows private hospitals to enter national health insurance schemes.

Contributors

XZ, AZ, OO, and ST conceptualized the paper. XZ, AZ, OO, and ST developed the methodology. XZ, AZ, YZ, OO, and ST conducted the analysis and created visualizations. XZ curated the data. XZ and AZ wrote the original draft. XZ, AZ, OO, and ST reviewed and edited the draft. OO and ST provided supervision. XZ acquired funding.

Data sharing statement

All data presented in this study is publicly available from the referenced sources.

Declaration of interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Funding: XZ and YZ received funding from the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission [grant number 20194Y0310] and National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 72204160]. AZ and ST received funding from the Duke Global Health Institute. The funding agencies played no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.The private health sector: an operational definition. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/private-health-sector-definition [cited 2023 July 25]. Available from:

- 2.Zwi A.B., Brugha R., Smith E. Private health care in developing countries. BMJ. 2001;323(7311):463–464. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The private sector, universal health coverage and primary health care. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.53 [cited 2023 July 25]. Available from:

- 4.The private sector and universal health coverage. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/PMC6560377 [cited 2023 July 25]. Available from:

- 5.Jiang Q., Pan J. The evolving hospital market in China after the 2009 healthcare reform. Inquiry. 2020;57 doi: 10.1177/0046958020968783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng C., Li X., Pan J. Private hospital expansion in China: a global perspective. Glob Health J. 2018;2(2):33–46. doi: 10.1016/S2414-6447(19)30138-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L., Wang Z., Ma Q., Fang G., Yang J. The development and reform of public health in China from 1949 to 2019. Glob Health. 2019;15(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s12992-019-0486-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y. China’s public health-care system: facing the challenges. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(7):532–538. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hesketh T., Zhu W.X. Health in China. The healthcare market. BMJ. 1997;314(7094):1616–1618. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7094.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blumenthal D., Hsiao W. Privatization and its discontents--the evolving Chinese health care system. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1165–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr051133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang C., Zhang Y., Chen L., Lin Y. The growth of private hospitals and their health workforce in China: a comparison with public hospitals. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(1):30–41. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yip W.C.M., Hsiao W.C., Chen W., Hu S., Ma J., Maynard A. Early appraisal of China’s huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):833–842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.China statistical yearbook | GHDx. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/series/china-statistical-yearbook [cited 2023 July 25]. Available from:

- 14.China health and family planning statistics yearbook 2017 | GHDx. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/china-health-and-family-planning-statistics-yearbook-2017 [cited 2023 July 25]. Available from:

- 15.Xiao Y., Zhao K., Ma Z.X., Li X., Qiu Y.P. Integrated medical rehabilitation delivery in China. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2017;3(2):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.2019 Shanghai statistical health yearbook. https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/zgsh/tjnj2019en.html

- 17.Yan X., Liu Y., Rao K., Li J. What is the major driver of China’s hospital medical expenditure growth? A decomposing analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts M., Hsiao W., Berman P., Reich M. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. Getting Health Reform Right. A guide to improving performance and equity. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gusmano M.K. The role of the public and private sectors in China’s health care system. Glob Soc Welf. 2016;3(3):193–200. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., Tang W., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Zhang L. National Health Insurance Development in China from 2004 to 2011: coverage versus benefits. PLoS One. 2015;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng Q., Fang H., Liu X., Yuan B., Xu J. Consolidating the social health insurance schemes in China: towards an equitable and efficient health system. Lancet. 2015;386(10002):1484–1492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y.-W., Chen J.-Y., Zhang B., et al. A cohort study on the changes of medical service utilization and cost burden after the integration of basic medical insurance system for urban and rural residents. Health Econ Res. 2022;39(7):32–36. doi: 10.14055/j.cnki.33-1056/f.2022.07.019. [in Chinese] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He L. The status of medical insurance services in private hospitals and countermeasures and suggestions. Finance Econ. 2018;(12):163–164. doi: 10.14057/j.cnki.cn43-1156/f.2018.12.071. [in Chinese] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jingjing L. Exploration and analysis of tax system reform of medical institutions under the new medical reform. Chin Health Econ. 2015;34(9):10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W., Wang C. Private medical institutions in China: status quo, dilemma and rethinking. Chin J Health Policy. 2016;9(9):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daxi Z. Comparison of taxation policies suitable for public hospitals and private hospitals. Chin J Health Policy. 2016;9(12):56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin C., Wang X., He D. Private medical institutions in China: policy review and analysis. Chin J Health Policy. 2014;7(4):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang B. Predicament and breakthrough of private non-profit medical institutions—the introduction of a “Low-profit Private Medical Institutions”. Concept J Shaanxi Acad Gov. 2014;28(3):2326. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China. State Taxation Administration of the People’s Republic of China Notice of the Ministry of Finance and the State Taxation Administration on comprehensively launching the pilot program of levying value-added tax in replacement of business tax. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-03/29/content_5059411.htm Available from:

- 30.Eggleston K., Lu M., Li C., et al. Comparing public and private hospitals in China: evidence from Guangdong. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:76. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y.-L. Research on existing problems and countermeasures in performance management of private hospitals. Qual Mark. 2022;(7):136–138. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei H.-N., Li Y.-S., Huang Y.-Q., et al. Problems and countermeasures in human resource management of doctors in private hospitals. Med Soc. 2018;31(4):37–39. doi: 10.13723/j.yxysh.2018.04.011. [in Chinese] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M., Wang M., Wen Z.-L. A preliminary study on medical management strategies in private hospitals in China. Mod Hosp Manag. 2017;15(3):28–31. Public hospitals uphold strict medical quality and safety standards. In contrast, some private hospitals lack stringent regulations, with a few compromising on clinical standards and product quality, leading to significant medical incidents. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang C., Xu J., Zhang M. The choice and preference for public-private health care among urban residents in China: evidence from a discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):580. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1829-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rong C. Research on market access regulation of the private medical institution-a law and economics perspective. Theory Pract Finance Econ. 2016;37(5):140–144. [Google Scholar]

- 36.He S., Xiong X., Zhou Y. Theory, obstacles and solutions of the access of private medical institutions. Chin Hosp Manage. 2019;39(8):11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou D. Ningbo University; 2014. Research on supervision of private medical institution in Yinzhou District of Ningbo. [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . 2019. Opinions on promoting the sustainable and standardized development of private medical institutions.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s3577/201906/8e83be9a99764ea6bb5f924ad9b1028d.shtml Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du H., Zhang N., Wen N. Reflection on intensified supervision and management in private hospitals in the background of new medical reform. Mod Hosp Manag. 2012;10(3):8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jinmei L. Hunan University; 2020. Research on health administrative supervision of private medical institutions under the background of new medical reform. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang D. Government investment and the development of private hospitals. Tax Econ. 2018;(4):58–63. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mei S., Huang H. The development of non-profit private hospitals in China: institutional obstacles and policy suggestions. Chin J Health Policy. 2014;7(5):33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xue Q., Xu D.R., Cheng T.C., Pan J., Yip W. The relationship between hospital ownership, in-hospital mortality, and medical expenses: an analysis of three common conditions in China. Arch Public Health. 2023;81(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13690-023-01029-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan N., Liu T., Xu Y., et al. Healthcare preferences of the general Chinese population in the hierarchical medical system: a discrete choice experiment. Front Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1044550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao X., Xiao J., Chen H., et al. Patient preferences and attitudes towards first choice medical services in Shenzhen, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daxi Z. Comparison on suitable fiscal subsidy policies for public hospitals and private hospitals. Chin Health Econ. 2016;35(5):25–28. [Google Scholar]

- 47.The General Office of the State Council The State Council General Office’s guidance on government purchasing services from social forces. https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2013-09/30/content_2498186.htm Available from:

- 48.Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China The notice on budget management issues related to government purchasing services. https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2014-02/11/content_2587140.htm Available from:

- 49.The State Council The decision on deepening budget management reform by the State Council. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-10/08/content_9125.htm Available from: