Key Clinical Message

Primary mediastinum immature teratoma with somatic‐type malignant transformation (SM) is extremely rare, and the clinical prognosis is poor. Immature teratoma with SM is difficult to eradicate by chemotherapy due to poor sensitivity; therefore, surgical resection is recommended whenever possible because it may offer better survival.

Keywords: en bloc, primary mediastinum immature teratoma, somatic‐type malignant transformation, surgery

A large mass (approximately 21.6 × 12.3 × 105 cm3) in the anterior mediastinum with a well‐defined margin and the important structures in the mediastinum were compressed and surrounded by the tumor. Then the en bloc resection of the large solid tumor with an intact capsule via a median sternotomy was conducted.

1. INTRODUCTION

Germ cell tumors (GCTs) are a family of neoplasms with diverse histopathological and clinical features and prognoses that are widely considered to arise from primordial germ cells. 1 Gonads are the most common organ in which GCTs predominantly occur, while a small proportion of GCTs primarily develop in extragonadal regions, such as the pineal gland, coccyx, mediastinum, retroperitoneum, 2 and the anterior mediastinum is the prior anatomical position in which approximately 10%–20% of primary extragonadal GCTs occur. 3 Pathologically, GCTs are divided into two categories: pure seminomas and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCTs). 4 Teratoma, a subtype of NSGCT, accounts for approximately 40%–60% of all mediastinal GCTs, with the majority of its histology being mature. 5 Immature teratomas, a particularly rare subtype of teratomas with poor clinical prognosis, account for only approximately 1.8% of mediastinal GCTs and approximately 4% of mediastinal teratomas. 3 Moreover, immature teratomas with somatic‐type malignant transformation (SM) are extremely rare, 6 and there are only a few cases describing this topic. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 We herein report a case of a chemotherapy‐resistant and extremely giant immature teratoma that received en bloc resection with pathologic findings of foci of sarcoma and poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest primary mediastinum immature teratoma with somatic‐type malignant transformation treated with en bloc resection thus far.

2. CASE PRESENTATION

An 18‐year‐old adolescent came to our medical center from a local hospital for further management of a giant anterior mediastinum mass. Four months before this admission, he underwent a routine health examination at a local health institution and found a large mass in the mediastinum without any clinical symptoms, such as chest pain, dyspnea, or cough. For further treatment, he was referred to a comprehensive oncology hospital, and malignant GCT was diagnosed by mediastinal biopsy. Therefore, combined chemotherapy with etoposide (100 mg/m2 IV on Days 1–5), bleomycin (30 units IV on Days 1, 8, and 15), and cisplatin (20 mg/m2 IV on Days 1–5) was subsequently initiated. However, when four cycles of chemotherapy were finished, he underwent a chest CT again, which indicated that there was no obvious improvement. Hence, he received radiotherapy (the specific dose was not known) at another oncology hospital, the mediastinum mass failed again to respond to radiotherapy, and the tumor volume even grew thereafter. In our hospital, physical examination revealed a thin‐built man with normal vital signs and weight loss. Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCs), such as facial edema and jugular vein distention, was not observed. Respiratory, cardiac, abdominal, testicular, and lymph node examinations were negative.

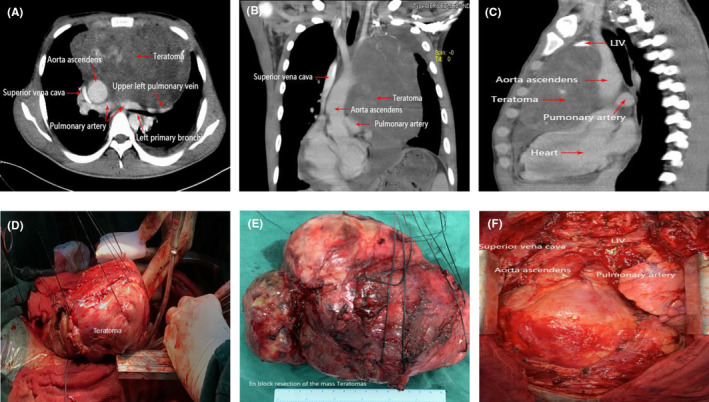

Contrast‐enhanced CT showed a large (approximately 21.6 × 12.3 × 105 cm3) solid mass with heterogeneous enhancement that was not calcified in the anterior mediastinum. The heart and great vessels, including the superior vena cava (SVC), ascending aorta, pulmonary artery, and left principal bronchus, were compressed and surrounded by tumors with well‐defined margins, while mediastinal lymph nodes were not noted (Figure 1). Brain MRI, abdominal contrast‐enhanced CT, bone scan, and pulmonary function test were normal.

FIGURE 1.

(A–C) Contrast‐enhanced CT indicated a large mass in the anterior mediastinum with a well‐defined margin, and the important structures in the mediastinum were compressed and surrounded by the tumor. (D–F) En bloc resection of the large solid tumor with an intact capsule via a median sternotomy.

Laboratory investigations showed thrombocytopenia (platelets = 21 × 109/L, normal = 100–300 × 109/L), anemia (hemoglobin [Hb] = 92 g/L, normal range = 130–175 g/L), and a normal leukocyte count. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alpha fetoprotein (AFP), β‐human chorionic gonadotropin (β‐HCG), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) were elevated (AFP > 1210 ng/mL, normal < 8 ng/mL; β‐HCG = 270.48 mIU/mL, normal < 3.81 mIU/mL; CEA = 3.71 ng/mL, normal < 3.4 ng/mL). After chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the level of AFP decreased to 69.56 ng/mL, and β‐HCG decreased to normal (β‐HCG = 0.26 mIU/mL). Other laboratory examinations, including renal, hepatic, and coagulation function, were within acceptable limits. Therefore, the patient underwent surgical resection of the tumor after informed consent was obtained from the patient.

A giant solid mass with an intact capsule was observed macroscopically. In the mass, most of the components were solid with local necrosis and multiple cysts. Two mediastinal lymph nodes were observed with a diameter of approximately 0.8–0.9 cm. At the same time, a piece of pericardium attached to the tumor with a size of approximately 3.6 cm × 2.2 cm was also observed. Microscopically, the tumor consisted of epithelial tissue, cartilage tissue, skeletal muscle tissue, and other mesenchymal tissue, some of which presented with immature or malignant morphology (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that cytokeratin (CK), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), smooth muscle actin (SMA), desmin (Des), MyoD 1, and myogenin were positive, while AFP and HCG were negative, indicating that the large mass was an immature teratoma with poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma and sarcoma malignant transformation.

FIGURE 2.

HE staining of somatic‐type malignancy components showing (A) rhabdomyosarcoma; (B) chondrosarcoma; (C) fibrosarcoma; and (D) poorly differentiated carcinoma. Magnification ×200.

3. DISCUSSION

GCTs are a group of neoplasms that stem from different anatomic sites and in different age groups. They are mainly located along the midline of the body, with the gonads being the most frequently involved organ and the mediastinum being the most common site of extragonadal GCTs. 2 , 13 The majority of GCTs contain mixed components, and approximately 15% of them have the potential to be malignant, but rarely do these tumors actually undergo malignant degeneration. 14 Tumor malignant transformation (TMT) refers to a nongerm cell tumor malignant component that can be found within the bulk of a GCT or in its metastatic foci, which is called a GCT with somatic‐type malignancy (SM), 15 accounting for approximately 6% of GCTs. 16 SMs of GCTs are most often observed in the retroperitoneum and recurrent cases, and they are extremely rare in the mediastinum with immature teratoma. 6 , 17

Most likely because the components of GCTs have pluripotency, various types of histological malignant transformation may occur simultaneously within a GCT, of which sarcoma (predominantly rhabdomyosarcoma) is the most frequent histological type of SM followed by adenocarcinoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumors, while melanocytic neuroectodermal transformation is the rarest. 17 , 18 Other histology types include squamous cell transformation, carcinoid tumors, hemangioendothelioma, and nephroblastoma. 18 In our case, the immature tumor was proven to have an SM, and the histological types were squamous cell tumor and sarcoma (rhabdomyosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and fibrosarcoma), while the lymph node metastasis was found to be squamous cell tumor malignant transformation, which meant a higher recurrence rate and aggressiveness than teratomas without malignant transformation. 17 GCTs that develop SM naturally have rarely been reported, and they are seen more frequently in older patients with a peak age of 50–60 years old 15 , 19 , 20 ; most of them initially occur after chemotherapy or irradiation in young patients with a malignant GCT. 15 Therefore, this could explain why our patient with initially a malignant GCT developed SM after chemotherapy and irradiation. However, the specific mechanisms of GCTs with SM are poorly understood, and two pathogeneses are assumed. First, chromosomal abnormalities have been detected, such as isochromosome 12p or rearrangement of 2q, 21 and Honecker et al. 22 proved that mature teratoma cells could undergo dedifferentiation in vitro into malignant tissues. Second, a totipotential embryonal carcinoma cell transformed to a neoplasm of the somatic type through malignant dedifferentiation could also be related to this phenomenon. 23 Few other cases of immature teratoma with somatic‐type malignancy have been reported previously (Table 1). 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest primary mediastinum immature teratoma with somatic‐type malignant transformation that has received en bloc resection thus far.

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of primary mediastinal GCTs cases with somatic‐type malignant transformation reported in the literature.

| Publication | Age (years) | Gender | Clinical symptoms | Size of the mass (cm) | Components of somatic‐type malignancy | Chemotherapy | Radiotherapy | Surgery | Survival (last to follow‐up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyo‐Jae Lee et al. (2017) | 43 | Male | Chest pain | 9 × 7 | Liposarcoma | Yes (PEB/VIP) | No | No | NS |

| Inga‐Marie Schaefer et al. (2013) | 22 | Male | Dyspnea, anterior thoracic pain, coughing, and fever | 11 | Neuroendocrine carcinoma | No | No | Yes | 12 months |

| Yamamoto et al. (1999) | 27 | Male | NS | NS | Rhabdomyosarcoma | Yes (PEB/PAVBC) | No | Yes | 6 months |

| Osama et al. (2016) | 21 | Male | Cough, shortness of breath, chest pain | 12 × 13 × 12 | Sarcomatous, carcinomatous, and melanomatous | Yes (PEB/T) | No | Yes | 5.5 months |

| Chua and Mortimer et al. (1992) | 25 | Male | Lethargy, dry cough, dyspnea | NS | Melanoma | Yes (PEB) | No | NS | NS |

| Kai‐li Huang et al. (2020) | 18 | Male | None | 21.6 × 12.3 × 10.5 | Squamous cell carcinoma and sarcoma | Yes (PEB) | Yes | Yes | 5 months |

Abbreviations: GCT, germ cell tumor; NS, not specified; PAVBC, cisplatin, actinomycin D, vinblastine, bleomycin, and cyclophosphamide; PEB, cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin; T, temozolomide; VIP, vinblastine, ifosfamide, and cisplatin.

Clinically, because mediastinal structures can accommodate large teratomas and their insidious growth, the manifestation of symptoms is not obvious even though GCTs with SM tend to be more symptomatic than those without SM, but the symptoms are rarely indistinguishable when they are present. 29 However, several syndromes have been identified in association with nonseminomatous mediastinal GCTs that may aid diagnosis, such as Klinefelter's syndrome and hematologic neoplasms. 30 As in our case, the patient did not have a large solid mass in the anterior mediastinum until he underwent a physical examination without presenting any anomalous symptoms. Symptoms such as cough, chest pain, dyspnea, heart failure, dysphagia, hemoptysis, hoarseness, and postobstructive pneumonia can arise when the tumor invades or compresses the surrounding organs in the mediastinum, 31 but these symptoms are not specific. Although teratomas can grow extremely large, patients with superior vena cava syndrome (SVC) are rarely observed, accounting for no more than 10% of cases. 32 Radiologically, due to the coexistence of tumor cells with different proliferation rates, attenuation heterogeneity is a common characteristic of the mass, and GCTs with SM could present as solid masses along with areas of teratomatous, necrotic, or hemorrhagic zones in contrast‐enhanced CT scans. 33 However, it did not suggest a particular subtype of malignant transformation that was mainly diagnosed based on histological analysis via a biopsy or surgical specimen. 34 However, contrast‐enhanced CT scanning is useful to determine whether adjacent structures, such as the great vessels, heart, and lung, are invaded by the tumor or whether tumors metastasize to regional lymph nodes or other organs, such as the lung, brain, liver, and spleen, as well as tumor recurrence. 27 In the case we reported herein, multiple characteristics were demonstrated in contrast‐enhanced CT scanning. Laboratory examination found that serum tumor markers such as AFP and LDH are frequently elevated in 80% of patients with primary nonseminoma mediastinal GCTs; however, only approximately 30%–35% of patients have elevated β‐HCG. 35 Mediastinal nonseminomatous GCTs with elevated AFP and β‐HCG have been previously reported in GCTs with SM, suggesting the presence of malignancy and poor prognosis. 5 , 36 In the case mentioned herein, high levels of AFP (>1210 ng/mL) and β‐HCG (270.48 mIU/mL) were observed before treatment. After chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the levels of AFP and β‐HCG decreased, and neither AFP‐ nor HCG‐producing cells were confirmed in the resected specimens, indicating that necrosis or deproduction in the AFP‐ and HCG‐producing cells was induced by preoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy. 37 However, the patient's clinical presentation deteriorated, with the tumor growing rapidly and larger than before, which was not deemed teratoma syndrome characteristically seen in mature mediastinal teratomas. 38 In this case, the rapid tumor aggression is more likely due to the underlying aggressive nature of the non‐GCT malignant transformation components, especially sarcoma. 36 It has been previously shown that GCTs with SM, especially those with sarcoma malignant transformation, have a poor response to cisplatin‐based chemotherapy. 17 , 39

Orizi et al. 40 found that hematopoietic stem cells could exist in mediastinal GCTs, which might cause hematologic derangements and were associated with nontreatment‐related blood malignance. 41 Garnick et al. 42 also found that primary mediastinal GCTs were associated with thrombocytopenia. This might explain the continued reduction in platelets that occurred in our patient. Another explanation for this phenomenon might be myelosuppression caused by chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery, but we failed to conduct a bone marrow biopsy to further determine the pathogenesis of this phenomenon. It is worth noting that GCTs may induce thrombotic events, especially during chemotherapy, and pulmonary embolism (PE) might be suspected when sudden hemoptysis occurs. 43

Currently, the standard treatment for nonseminoma GCTs is chemotherapy followed by surgical resection of the residual mass; however, radiotherapy is not recommended because it is ineffective in treating primary mediastinal nonseminoma GCTs. The recommended chemotherapy is four courses of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin. 2 Given the poor sensitivity to chemotherapy, immature teratoma with SM is difficult to eradicate by cisplatin‐based chemotherapy, and aggressive surgical resection is recommended whenever possible because it may offer better survival. 44 Nonetheless, teratomas with SM present in the mediastinum essentially have an aggressive course, high recurrence rate, and poor prognosis and are always fatal within a few months after initial diagnosis. 15 As our case demonstrated, the tumor was resistant to standard chemotherapy and showed progression in size after chemotherapy; therefore, a primary mediastinal GCT with SM might be suspected, 15 and surgical intervention instead of any other treatments should be considered first whenever possible.

Generally, primary mediastinal teratomas with SM have an extremely poor prognosis for malignant transformation components in terms of chemotherapy resistance, high recurrence, increased invasiveness, and sometimes even sudden death. 20 , 45 Several indicators may be related to poor prognosis for GCTs, including 1 persistent germ cell tumor in the residual mass 2 ; elevated LDH 3 ; GCTs with thrombocytopenia 4 ; somatic‐type transformation; and 5 postchemotherapy AFP level greater than 1001 ng/mL. 46 , 47 Our patient had a number of poor indicators, including elevated LDH, thrombocytopenia, and somatic‐type transformation. Even though complete resection of the tumor had been achieved, he finally died 5 months after the initial diagnosis, which was consistent with a previous study. 15

4. CONCLUSION

In summary, primary mediastinal immature teratoma with somatic‐type malignancy is extremely rare with an extremely poor prognosis. When laboratory and imaging findings are conflicting for patients with immature teratoma after chemotherapy, somatic‐type malignancy should be considered. Due to its rarity, comprehensive reporting of clinical, radiological, and pathological features is needed for a diagnosis of an immature teratoma with SM. We reported a primary giant mediastinal immature teratoma with sarcoma and squamous malignant transformation that was resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy but resected completely. Additional cases of this pathology are needed to add to the literature for a better understanding of somatic‐type malignancy and management of this disease.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kai‐li Huang: Writing – original draft. Pengfei Li: Writing – review and editing. Han‐Yu Deng: Writing – review and editing. Xiaojun Tang: Methodology; writing – review and editing. Qinghua Zhou: Conceptualization.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing interests.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Huang K‐l, Li P, Deng H‐Y, Tang X, Zhou Q. En bloc resection of an extremely giant mediastinal immature teratoma with somatic‐type malignancy: A case report with a brief review of the literature. Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:e8344. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.8344

Kai‐li Huang and Pengfei Li contributed equally to the study and were co‐first authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Angelica S, Amatruda JF. Zebrafish Germ Cell Tumors. Springer International Publishing; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosti G, Secondino S, Necchi A, Fornarini G, Pedrazzoli P. Primary mediastinal germ cell tumors. Semin Oncol. 2019;46(2):107‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moran CAS. Suster primary germ cell tumors of the mediastinum: I. Analysis of 322 cases with special emphasis on teratomatous lesions and a proposal for histopathologic classification and clinical staging. Cancer. 1997;80(4):681‐690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schmoll HJ. Extragonadal germ cell tumors. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(Suppl 4):265‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dulmet EM, Macchiarini P, Suc B, Verley JM. Germ cell tumors of the mediastinum. A 30‐year experience. Cancer. 1993;72(6):1894‐1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahmed T, Bosl GJ, Hajdu SI. Teratoma with malignant transformation in germ cell tumors in men. Cancer. 1985;56(4):860‐863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adachi Y, Okamura M, Yasumizu R, et al. An autopsy case of immature teratoma with choriocarcinoma in the mediastinum. Kyobu Geka. 1995;48(10):829‐832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bialik VV, Zakharychev VD, Rudenko AV. Immature teratoma of the anterior mediastinum with elements of chorioepithelioma. Arkh Patol. 1971;33(4):64‐67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chakraborty J, Paul PC, Chakrabarti S, et al. Immature mediastinal teratoma – a rare pathology. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006;49(1):32‐33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Georgiu C, Opincariu I, Cebotaru CL, et al. Intracranial immature teratoma with a primitive neuroectodermal malignant transformation ‐ case report and review of the literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57(4):1389‐1395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kovalev MM. Chorioepithelioma from a teratoma of the anterior mediastinum. Arkh Patol. 1961;23(3):79‐80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sakthivel P, Kumar Irugu DV, Kakkar A, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma as a somatic‐type malignancy in an extragonadal immature teratoma of the sinonasal region. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;126:109639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stang A, Trabert B, Wentzensen N, et al. Gonadal and extragonadal germ cell tumours in the United States, 1973–2007. Int J Androl. 2012;35(4):616‐625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vuky J, Bains M, Bacik J, et al. Role of postchemotherapy adjunctive surgery in the management of patients with nonseminoma arising from the mediastinum. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(3):682‐688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morinaga S, Nomori H, Kobayashi R, Atsumi Y. Well‐differentiated adenocarcinoma arising from mature cystic teratoma of the mediastinum (teratoma with malignant transformation). Report of a surgical case. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101(4):531‐534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. El Mesbahi O, Terrier‐Lacombe MJ, Rebischung C, et al. Chemotherapy in patients with teratoma with malignant transformation. Eur Urol. 2007;51(5):1306‐1311; discussion 1311‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Athanasiou A, Vanel D, El Mesbahi O, et al. Non‐germ cell tumours arising in germ cell tumours (teratoma with malignant transformation) in men: CT and MR findings. Eur J Radiol. 2009;69(2):230‐235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Necchi A, Colecchia M, Nicolai N, et al. Towards the definition of the best management and prognostic factors of teratoma with malignant transformation: a single‐institution case series and new proposal. BJU Int. 2011;107(7):1088‐1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Knapp RH, Hurt RD, Payne WS, et al. Malignant germ cell tumors of the mediastinum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;89(1):82‐89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jung JI, Park SH, Park JG, Lee SH, Lee KY, Hahn ST. Teratoma with malignant transformation in the anterior mediastinum: a case report. Korean J Radiol. 2000;1(3):162‐164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sugimura J, Foster RS, Cummings OW, et al. Gene expression profiling of early‐ and late‐relapse nonseminomatous germ cell tumor and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the testis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(7):2368‐2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Honecker F, Stoop H, Mayer F, et al. Germ cell lineage differentiation in non‐seminomatous germ cell tumours. J Pathol. 2006;208(3):395‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chaganti RSJ. Houldsworth genetics and biology of adult human male germ cell tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60(6):1475‐1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee HJ, Seon HJ, Choi YD. Radiological‐pathological correlation of malignant teratoma with liposarcomatous transformation: proven by repeated transthoracic needle biopsy. Thorac. Cancer. 2018;9(1):185‐188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schaefer IM, Zardo P, Freermann S, Marx A, Ströbel P, Fischer S. Neuroendocrine carcinoma in a mediastinal teratoma as a rare variant of somatic‐type malignancy. Virchows Arch. 2013;463(5):731‐735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yamamoto T, Tamura J, Orima S, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma in a patient with mosaic Klinefelter syndrome and transformation of immature teratoma. J Int Med Res. 1999;27(4):196‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mustafa OM, Mohammed SF, Aljubran A, Saleh WN. Immature mediastinal teratoma with unusual histopathology: A case report of multi‐lineage, somatic‐type malignant transformation and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(26):e3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chua HC, Mortimer PS. Malignant melanoma occurring as a second cancer following primary germ cell tumour in males: report of three cases. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127(4):448‐449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10(9):1243‐1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nichols CR, Heerema NA, Palmer C, Loehrer PJ Sr, Williams SD, Einhorn LH. Klinefelter's syndrome associated with mediastinal germ cell neoplasms. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5(8):1290‐1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Albany C, Einhorn LH. Extragonadal germ cell tumors: clinical presentation and management. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25(3):261‐265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yalagachin Gurushantappa H. Anterior mediastinal teratoma – a case report with review of literature. Indian J Surg. 2013;75(1 Supplement):S182‐S184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Strollo DC, Rosado‐de‐Christenson ML. Primary mediastinal malignant germ cell neoplasms: imaging features. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2002;12(4):645‐658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang LJ, Chu SH, Ng KF, Wong YC. Adenocarcinomas arising from primary retroperitoneal mature teratomas: CT and MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(6):1546‐1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hainsworth JD. Diagnosis, staging, and clinical characteristics of the patient with mediastinal germ cell carcinoma. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2002;12(4):665‐672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Taniyama K, Ohta S, Suzuki H, Matsumoto M, Nagashima Y, Tahara E. Alpha‐fetoprotein‐producing immature mediastinal teratoma showing rapid and massive recurrent growth in an adult. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1992;42(12):911‐915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arai K, Ohta S, Suzuki M, Suzuki H. Primary immature mediastinal teratoma in adulthood. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23(1):64‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. André F, Fizazi K, Culine S, et al. The growing teratoma syndrome: results of therapy and long‐term follow‐up of 33 patients. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(11):1389‐1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gonzalez‐Vela JL, Savage PD, Manivel JC, Torkelson JL, Kennedy BJ. Poor prognosis of mediastinal germ cell cancers containing sarcomatous components. Cancer. 1990;66(6):1114‐1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Orazi A, Neiman RS, Ulbright TM, Heerema NA, John K, Nichols CR. Hematopoietic precursor cells within the yolk sac tumor component are the source of secondary hematopoietic malignancies in patients with mediastinal germ cell tumors. Cancer. 1993;71(12):3873‐3881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nichols CR, Roth BJ, Heerema N, Griep J, Tricot G. Hematologic neoplasia associated with primary mediastinal germ‐cell tumors. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(20):1425‐1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Garnick MB, Griffin JD. Idiopathic thrombocytopenia in association with extragonadal germ cell cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98(6):926‐927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weijl NI, Rutten MF, Zwinderman AH, et al. Thromboembolic events during chemotherapy for germ cell cancer: a cohort study and review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(10):2169‐2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kesler KA, Rieger KM, Hammoud ZT, et al. A 25‐year single institution experience with surgery for primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(2):371‐378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sanchez‐Hermosillo E, Sikirica M, Carter D, Valigorsky JM. Sudden death due to undetected mediastinal germ cell tumor. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1998;19(1):69‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kesler KA, Rieger KM, Ganjoo KN, et al. Primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: the influence of postchemotherapy pathology on long‐term survival after surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;118(4):692‐700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6199‐6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.