Abstract

Fathers can influence child development through various pathways, such as via their caregiving behaviors, marital relationships, and their psychosocial wellbeing. However, few parenting interventions have been designed to target these multiple dimensions among fathers with young children in low- and middle-income countries. In June 2022, we conducted qualitative formative research to explore the perceptions surrounding fatherhood and the underlying barriers and enablers to engaged fathering in Mwanza, Tanzania. We completed individual in-depth interviews with 29 fathers and 23 mothers of children under aged 2 years along with 5 community leaders and 3 community health workers. We also completed 10 focus group discussions: 4 with fathers, 2 with mothers, and 4 mixed groups that combined both fathers and mothers. In total, the sample included 120 respondents stratified from across 4 study communities. Data were analyzed using thematic content analysis. Respondents highlighted that poor couples’ relationships (e.g., limited male partner support, male dominance in decision-making) and fathers’ mental health problems (e.g., parenting stress) were major priorities affecting fathers. Father involvement in parenting, childcare, and household activities was generally low. These dimensions of fatherhood were interlinked (e.g., poor paternal mental health constrained marital relationships and parenting). A constellation of determinants impacted engaged fathering. Common barriers included poverty, restrictive gender attitudes and norms, men’s limited time at home, and inadequate knowledge about caregiving. Key enablers included mutual respect in marital relationships and men’s desires to show their love for their families. Our results highlight the cultural relevance and the need for multicomponent strategies that jointly target fathers’ caregiving, marital relationships, and psychosocial wellbeing for enhancing nurturing care and promoting early child development in Tanzania. Study findings can be used to inform the design of a future father-inclusive, gender-transformative parenting intervention for engaging and supporting fathers with young children in the local cultural context.

Keywords: fathers, parenting, couples’ relationships, mental health, qualitative research, Tanzania

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 250 million or 43% of children under age 5 years are failing to reach their developmental potential each year in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Lu et al., 2016). Various risk factors compromise healthy early child development (ECD), including extreme poverty, suboptimal parenting, marital conflict, and poor caregiver mental health (Walker et al., 2011). Nurturing care interventions that engage and support all caregivers in providing optimal psychosocial caregiving are effective for promoting ECD (Britto et al., 2017). However, most caregiving interventions to date have been designed for and delivered to mothers and thereby have ignored fathers (Jeong et al., 2021b).

A growing body of evidence has highlighted multiple ways by which fathers influence their young children’s development. First, fathers can impact ECD directly through their own parenting behaviors and interactions. For example, fathers’ play and communication with young children have been shown to improve later ECD outcomes above and beyond the known contributions of mothers (MacKenzie et al., 2013; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2004). In addition to fathers’ dyadic interactions with young children, fathers can indirectly shape ECD through their marital relationships and their own mental health (Walsh et al., 2020). According to family systems theory, couples’ relationships and the manners by which fathers interact with their partners is a central pillar within the family system that can have spillover effects onto both mother-child and father-child caregiving relationships (Cox & Paley, 1997). Prior empirical research has revealed that fathers who interact positively with their partners (e.g., greater coparenting, non-violent conflict resolution) are more likely to display responsiveness and warmth in their parenting interactions with their children (Carlson et al., 2011), which in turn can improve ECD outcomes (Feinberg et al., 2009; Jeong et al., 2020; Parkes et al., 2019).

Additionally and in line with family stress theory, high levels of paternal parenting stress or depression can contribute to fathers’ negative parenting practices and marital conflict, which have been shown to mediate effects on poorer early child behavior and developmental outcomes (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2010; Gutierrez-Galve et al., 2015). Conflict with the child’s mother or challenging interactions with the child can also in turn increase stress among fathers, thereby perpetuating a negative cycle between fathers’ parenting, martial relationships, and psychological wellbeing (Kumar et al., 2018). Although much of this literature to date has come from majority White and relatively small samples in high-income countries, this emerging evidence has underscored that fatherhood is multidimensional and fathers’ parenting, couples’ relationships, and fathers’ psychosocial wellbeing should be jointly considered to holistically understand the caregiving experience and influence of fathers on ECD (Cabrera et al., 2014; Cowan & Cowan, 2019).

In many non-Western cultures such in sub-Saharan Africa, fathers have been traditionally viewed as the patriarchal head of the household. Fathers’ roles as providers of the family is especially salient considering prevailing gender norms in these contexts that strongly equate fathers’ financial provisions with ideologies of masculinity (Mbonye et al., 2022). However, more recent studies have revealed that conceptualizations of fatherhood are evolving in LMICs due to sociodemographic transitions, with emerging evidence supporting a multidimensional construct of fatherhood globally. For example, analyses of population-level surveys indicate that fathers in LMICs are becoming more involved in interactive forms of parenting with their young children such as playing, reading, and naming things to their children during the first few years of life (Hollowell et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2016). Additionally, recent studies suggest that communities across sub-Saharan Africa are increasingly valuing other “caring masculinities” as well, including more engaged styles of interactions with both their children and partners, such as men’s positive communication or emotional support (Ganle et al., 2016; Manderson & Block, 2016). At the same time, cultural and contextual variations exist across LMICs (e.g., socioeconomic status, sources of paternal employment, and patriarchal norms) that can differentially shape fathers’ caregiving identities, family engagement, and mental health across diverse settings (Jeong et al., 2021a; Sikweyiya et al., 2017).

Despite the burgeoning evidence supporting these distinct dimensions and complex contexts surrounding fatherhood, few studies have holistically examined all three components of fatherhood – in terms of fathers’ parenting, couple’s relationships, and fathers’ mental health – in one analysis and with respect to ECD. In particular, fathers’ relationships with their partners have been largely overlooked in the fatherhood literature as a unique yet interconnected avenue from a family systems and developmental perspective through which fathers can influence young children in LMICs (Jeong et al., 2018 BMC Public Health; Mukuria et al., 2016). Moreover even in prior qualitative studies focused on fatherhood, there has been a relatively limited representation of fathers themselves in study samples, with prior studies instead drawing entirely from maternal reports about fathers (Temelkovska et al., 2022) or interviewing relatively few male caregivers (Firouzan et al., 2018).

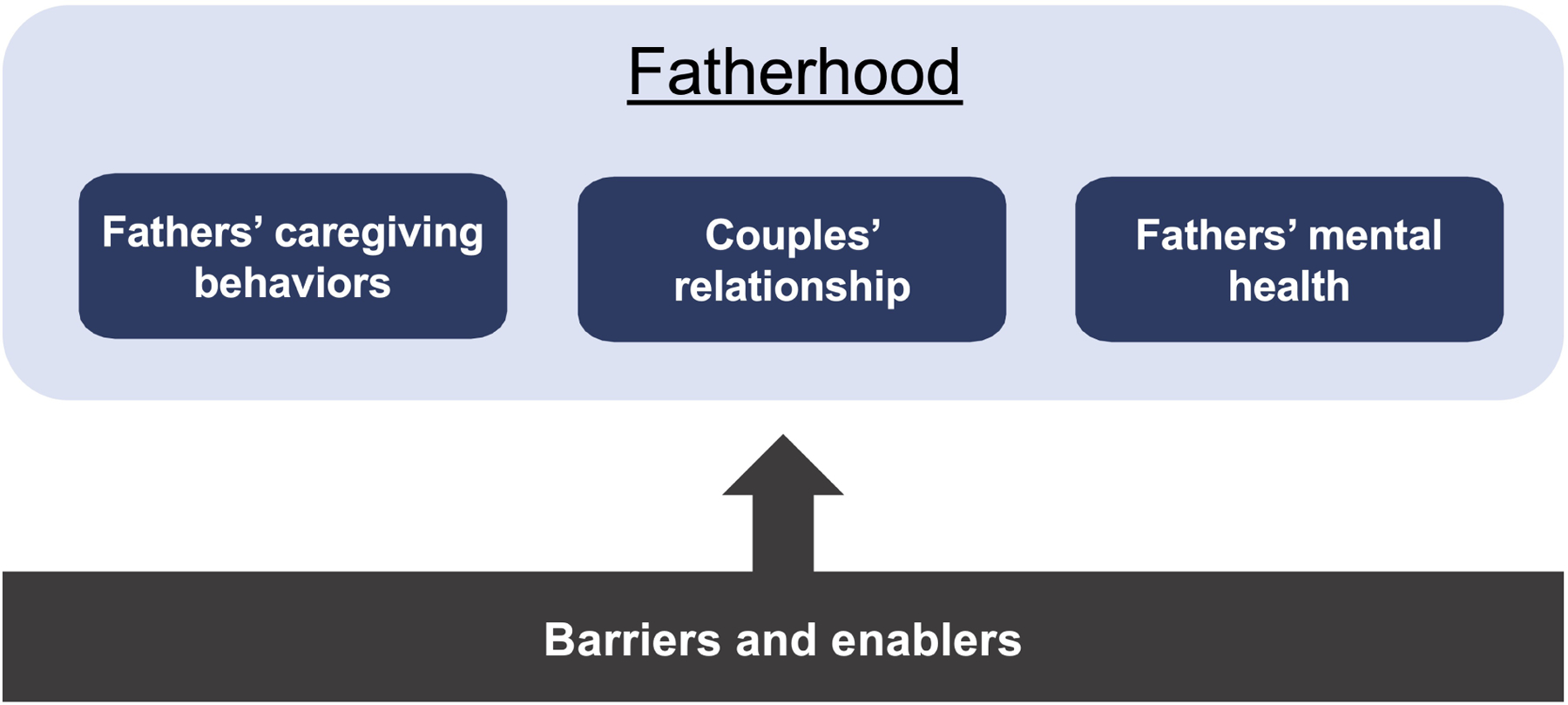

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to conduct formative research with a diverse group of respondents, including a balanced sample of both fathers and mothers, to explore the nature and meaning of fatherhood in Mwanza, Tanzania. Drawing from family systems theory and family stress theory, we conceptualized fatherhood in terms of three dimensions that jointly influence and characterize fathers’ caregiving behaviors and capacities with young children during their earliest years of life. More specifically, this broadly encompassed: (1) fathers’ caregiving behaviors (e.g., discipline, play and communication, childcare), (2) fathers’ relationships with their partners (e.g. partner support, decision-making, sources of conflict), and (3) fathers’ mental health (e.g. stress, depression) (Figure 1). Additionally, we aimed to identify the key barriers and enablers that influenced these components of engaged fathering in the local setting and drawing from Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model as a framework for how determinants can span multiple levels of society (e.g., individual, household, community-level factors) (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). We expect these findings will generate practical evidence that can directly inform the design of a future multicomponent social and behavior change intervention for addressing these distinct components of fatherhood to ultimately improve fathers’ psychosocial caregiving and ECD in the local context of Mwanza, Tanzania.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of fatherhood.

METHODS

Study design

We used a descriptive phenomenological qualitative design (Creswell, 2013) to explore community perspectives about the caregiving roles and experiences of fathers. We conducted individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) with fathers, mothers, community leaders, and community health workers (CHWs) along with focus group discussions (FGDs) with mothers and fathers. Interviewing different key informants and through multiple data collection methods enabled us to triangulate data across different sources. More specifically, we interviewed focal community leader and the CHW in each study community to explore how perspectives compared between parents and influential individuals in the community who regularly interacted with parents and/or young children. The FGDs with parents complemented the IDIs by allowing for a deeper exploration of community norms and attitudes about paternal caregiving practices beyond the individual experiences shared in the IDIs.

Study site

This study was conducted in Ilemela district, Mwanza city, Tanzania. Mwanza is located on the southern shores of Lake Victoria and is the second largest city in Tanzania. In Tanzania, it has been estimated that approximately 60% of the population identify as Christians, 35% as Muslim, and 5% as practicing other religions (Sundararajan et al., 2023). Based on the 2015–2016 DHS, 87% of men and 67% of women in Mwanza were employed in the 12 months preceding the time of the survey. Much of this is employment is through the informal workforce with small-scale agriculture as the main type of work outside of the home for men and women (Ministry of Health, 2016). Other common income-generating activities in Mwanza include livestock-keeping, fishing, selling sardines, and mining. At the same time and irrespective of formal employment, women in Tanzania are also primarily responsible for unpaid care work – caring for children and other family members and completing household chores such as cooking, cleaning, fetching water, and collecting fuel – that further burdens and amounts to many hours of women’s time use (Chung et al., 2019).

While there has been notable progress over the past decade towards improving early child outcomes in Tanzania, early child development remains a key concern in the country and including in Mwanza where 52% of preschool-age children are developmentally “off-track”, and 28% of children under-5 are stunted (Ministry of Health, 2023). Violence against children is also prevalent across the country with high rates of harsh discipline even among children under age 3 years (e.g., 62% of mothers having spanked their children in the past 3 days) (Ramos de Oliveira et al., 2022). Although Tanzania has committed itself to addressing violence against children through national laws and policies (e.g., Law of the Child Act 2009, National Plan of Action to end Violence Against Women and Children) and is a signatory to regional and international declarations on child rights (e.g., UN Convention on the Rights of the Child), corporal punishment remains legal, there is no mandatory reporting legislation, and it is widely accepted across communities (Frankenberg et al., 2010).

Sampling

We used a stratified sampling design and purposively selected two coastal communities and two inland communities – where the primary sources of paternal employment are fishing and agriculture, respectively – to capture greater variation in fatherhood and family caregiving experiences that might be due to employment type (Bliznashka et al., 2023). By community, we specifically refer to a “street” (mtaa in Kiswahili), which is the lowest government administrative unit at the community level in an urban/peri-urban area in Tanzania. The four study communities were located in peri-urban areas of Ilemela District outside of Mwanza town and selected in consultation with government representatives and our study partners at the Tanzania Home Economics Organization (TAHEA-Mwanza), which is a local non-governmental organization focused on supporting ECD in the region.

After determining the study communities, we engaged the respective community leaders to assemble a list of all caregivers with young children in each community. Specifically, we listed caregivers who met the following study eligibility criteria: an adult biological parent who was aged 18–65 years; had a child younger than 2 years of age; was in a relationship with the child’s other biological parent; and resided in the same house as partner and child at some point during the past month. We focused on parents who were currently in a formal partnership with another individual (i.e., legally or formally married or in a consensual union) because of our interest in exploring how marital relationships related to fathers’ parenting. Our restricted sample to biological parents who both lived in the household narrowed the investigation to focus on the phenomenon of fatherhood among primary caregivers who had a role since the birth of the child and in family units where co-parents were in contact regularly (i.e., as opposed to migratory fathers, single fathers, or social fathers like uncles/grandparents who have been characterized as having different experiences of fatherhood (Hosegood & Madhavan, 2010)). Population-level data indicate that the majority of children in Tanzania (60–80%) have such family caregiving arrangements in which they reside with both their biological mother and father (Martin & Zulaika, 2016). Eligible households were systematically contacted off the household lists (i.e., by working down the list and selecting every other household) and approached by the research team for participation in this study. Research assistants verified caregiver eligibility at enrollment.

The sample included 120 respondents from across 4 total communities. We completed IDIs with 29 fathers and 23 mothers of children under aged 2 years. We also completed 5 IDIs with community leaders and 3 community health workers. We identified community stakeholders through a convenience sampling approach. In one community, we interviewed the Street Chairperson (mwenyekiti wa mtaa in Kiswahii), who is unpaid and elected by community members to lead the “street” (mtaa in Kiswahili), or the smallest geographical units of urban/peri-urban governance. In two communities, we interviewed the Street Executive Officer (afisa mtendaji wa mtaa in Kiswahili), who is a paid civil servant and appointed by the local government as the community leader for the “street”. In the last community, we interviewed both the Street Executive Officer and the Ward Executive Officer (afisa mtendaji wa kata in Kiswahili, who is a paid civil servant and appointed by the local government to oversee a collection of “streets”) because he was also interested in participating. We also conducted IDIs with 3 community health workers, but were unable to reach the CHW for an interview in one of the study communities. We also completed 10 focus group discussions: 4 with fathers, 2 with mothers, and 4 mixed groups that combined both fathers and mothers (amounting to an additional 27 fathers and 33 mothers). See Table 1 for sampling distribution by communities and respondent types. This sample size was guided in part by prior methodological studies (Creswell, 2013) and through monitoring results during the data collection process to assess whether findings were reaching a point of saturation. All fathers and mothers came from separate households. Community leaders and CHWs were selected based on being the main focal person(s) for that role in a given selected study community. Although participants were not directly compensated, all received a refreshment and a small snack as a token of appreciation and reimbursed for any incurred transportation costs for their involvement in the study, as similarly approached in prior studies (e.g., Matovelo et al., 2021). Mothers were also welcome to bring their children to the interview and FGDs and were provided breaks for breastfeeding and other childcare responsibilities, as necessary.

Table 1.

Sample composition by respondent types and villages.

| Village 1 | Village 2 | Village 3 | Village 4 | Total respondents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-depth interviews | |||||

| Fathers | 9 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 29 |

| Mothers | 5 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 23 |

| Community leaders | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Community health workers | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Focus group discussions | |||||

| Fathers-only groups | 1 (4 men) |

1 (4 men) |

1 (6 men) |

1 (4 men) |

18 |

| Mothers-only groups | 1 (7 women) |

- | 1 (10 women) |

- | 17 |

| Mixed groups of fathers and mothers | 1 (2 men, 4 women) |

1 (2 men, 4 women) |

1 (3 men, 4 women) |

1 (2 men, 4 women) |

25 |

| Overall total respondents | 120 | ||||

Data collection

Data were collected using semi-structured interview guides, which were adapted for use in IDIs with parents, IDIs with community stakeholders, and FGDs with parents. All interview guides similarly covered questions about parenting roles (e.g., “What are your responsibilities for your child?”), couples’ relationships (e.g., “Between you and your partner, who makes the decisions in your family? And why are they divided this way?”), and parental mental health (e.g., “What, if anything, brings you stress in life?”). The combined FGDs had the same content as the father-only groups. These combined groups allowed us to obtain mothers’ perspectives and to contrast how fathers talked about their experiences in the presence of other women in the community compared to when men were in groups amongst themselves. Study tools were co-conceptualized and developed jointly among the investigators at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and TAHEA-Mwanza.

Data were collected by a team of five Tanzanian research assistants who were supervised by a Tanzanian co-investigator, who were all from Mwanza and bilingual in Kiswahili and English. Study investigators led a 7-day training for the research assistants that involved three days of classroom-based instruction about qualitative research methods and effective interviewing skills and four days of piloting and field-based practice in a non-study community. Twelve pilot IDIs were conducted with fathers, mothers, and community stakeholders and 2 pilot FGDs with parents. Through piloting, the guides were iteratively modified after each daily debrief to refine the wording of questions, add probes, and improve translations.

All interviews were conducted in a private setting at a central location in the community (e.g., community leader’s office or early childcare center). IDIs were conducted by one research assistant, while FGDs were facilitated by pairs of research assistants. Research assistants were mostly matched to the same gender as the respondent(s). For IDIs, we specifically asked the respondent if they preferred to be interviewed by a male or female research assistant. Nearly all respondents indicated no preference. IDIs with parents and community stakeholders were approximately 60–90 minutes in duration, whereas FGDs were on average 90 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded, which were transcribed into Kiswahili and then translated into English by a separate team of experienced translators who were uninvolved in the fieldwork. A 15% random sample of English transcripts were compared against the original audio recordings and checked for quality assurance.

Data were collected from June 8th to June 29th 2022. Four study investigators were present and debriefed daily with the field research team throughout this period to discuss field notes, emerging findings, and sampling progress. These daily debriefs and concurrent review of completed transcripts facilitated an assessment of whether data were reaching saturation.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using thematic content analysis (Schreier, 2014) and in line with a framework that sought to summarize the extent to which the different conceptualized dimensions of fatherhood were practiced or experienced by fathers in the community; and determine the main barriers and enablers for each dimension of engaged fathering. First, an initial codebook was developed by two analysts, based on the overarching study framework, interview guides, reflections shared by the field team during debrief meetings, and three selected transcripts. Once the draft version was developed, five analysts independently piloted the codebook using the same selected set of 8 caregiver IDI and 2 FGD transcripts, and iteratively refined it through a series of discussions in July 2022. At the end of the piloting period, the analysis team reached an inter-rater reliability rate of above 0.85 (Cohen’s Kappa) – indicating substantial agreement – on an exercise in which all analysts independently coded the same transcript. Then, three data analysts independently conducted line-by-line coding for all transcripts and documented memos. Weekly meetings were held among four analysts from August-October 2022 to review memos, resolve any uncertainties, make refinements to the codebook as needed, and discuss emerging themes. A randomly selected subsample of 30% of transcripts were independently reviewed and coded again by another analyst (Sept-Oct 2022) to enhance reliability. Then, four analysts collaboratively synthesized the codes and had weekly meetings from Oct-Nov 2022 to consolidate themes and draft results. Results were triangulated across the perspectives of the various respondent groups (i.e., fathers, mothers, community stakeholders). Findings were reviewed and discussed with three Tanzanian-based analysts to further ground results within the Tanzania context and explore additional analyses as needed. Finally, we returned to 2 study communities and organized community workshops, in which we held FGDs with parents and community stakeholders (Nov 2022). We presented results back to the community and obtained feedback to validate our findings and interpretations.

Ethics approvals

The protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania. Trained research assistants read aloud consent forms in Kiswahili, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

RESULTS

Among parents, the mean age of fathers was 36.1 years (range: 22–55) compared to 27.0 years for mothers (range: 18–49). The highest level of education for most parents was primary school, with only 16% of fathers and 12.5% of mothers completing secondary school or higher. All parents were married, of whom a small percentage (5.5%) were in polygynous marriages. Average index child age was 14.0 months (range: 1–24) and more than half were boys (59.8%). All community leaders were men, whereas two out of three CHWs were women. See Table 2 for sociodemographic characteristics of sample by respondent types.

Table 2.

Sample sociodemographic characteristics.

| Characteristic | % or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Parents (N=112) | |

| Father age (years) | 36.1 (8.6) |

| Mother age (years) | 27.0 (6.0) |

| Father highest education level attained | |

| Some primary | 18.0% |

| Completed primary | 66.0% |

| Completed secondary | 14.0% |

| College | 2.0% |

| Mother highest education level attained | |

| Some primary | 7.1% |

| Completed primary | 80.4% |

| Completed secondary | 10.7% |

| College | 1.8% |

| Parent marital status | |

| Married (monogamous) | 94.5% |

| Married (polygynous) | 5.5% |

| Child gender | |

| Male | 59.8% |

| Female | 40.2% |

| Child age (months) | 14.0 (7.0) |

| Community leaders (N=5) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 100% |

| Age (years) | 45.2 (15.5) |

| Highest education level attained | |

| Completed primary | 40.0% |

| Diploma | 40.0% |

| Certificate | 20.0% |

| Community health workers (N=3) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 33.3% |

| Female | 66.7% |

| Age (years) | 44.0 (12.0) |

| Highest education level attained | |

| Completed primary | 100.0% |

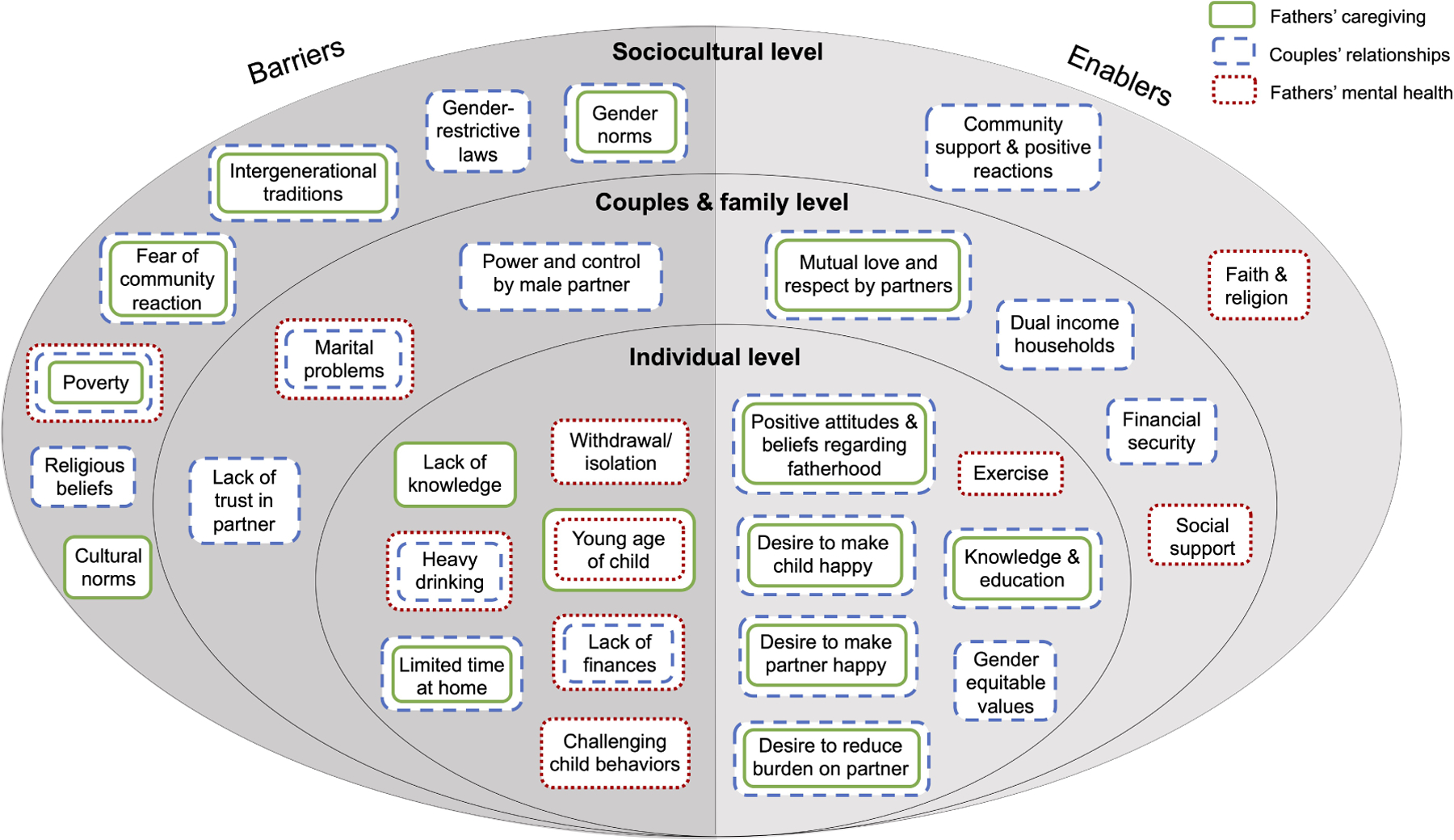

We organize the results below into three main sections aligning with our three dimensions of fatherhood: fathers’ caregiving behaviors, positive couples’ relationships, and fathers’ mental health. Within each of these broad sections, we first present the key thematic topics that emerged and the extent to which they were practiced or experienced by fathers followed by the main identified barriers and enablers for that dimension of engaged fathering. Key results across the various thematic areas of fatherhood are summarized in Table 3, with Figure 2 providing a visual of the overall barriers and enablers for each of the dimensions of fatherhood.

Table 3.

Summary of main findings.

| Topic area | Status with respect to fathers | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers’ caregiving behaviors | |||

| Discipline | - Central role of fathers - Fathers commonly use harsh disciplinary practices and viewed as effective for helping child learn |

- Cultural norms - Intergenerational traditions (reflect disciplinary styles that were used against fathers during their childhood) - Young age of child (belief that inappropriate to physically punish infants) - Lack of knowledge - Lack of time (despite the greater perceived effectiveness of paternal discipline, mothers spent more time at home with the child) |

- Fathers abstained from using violence, so children did not fear them - Positive couples relationships reduced use of harsh discipline |

| Play and communication | - Most fathers reported engaging in some form of play and communication with young children - Several mothers and community stakeholders reported that fathers were uninvolved in play or communication activities |

- Lack of time - Lack of knowledge - Restrictive gender norms (childcare roles viewed as responsibility of mothers) - Young age of child (belief that infants are too young for fathers to play with) |

- Joy and love brought to both children and fathers - Strengthened father-child bond - Defining characteristic of a “good father” |

| Other childcare and household responsibilities | - Primarily perceived as maternal responsibility, but with many fathers engaging indirectly through their financial roles (e.g., purchasing foods) - Any paternal engagement was circumstantial (e.g., mothers were sick or too busy) but not a regular role of fathers - Care seeking for child illness seen as joint responsibility, but fathers’ involvement was again primarily indirect (e.g., providing money) |

- Restrictive gender norms (viewed as mother’s responsibility, father who did such activities viewed as “bewitched”) - Social stigma and fear of community perceptions - Intergenerational traditions - Lack of time - Engagement in such activities viewed as having high opportunity costs - Young age of child (belief that infants are too fragile to be held by fathers) |

- Defining characteristic of a “good father” - Desire to reduce burden on partners, give them time to rest, and show love - Beneficial for children to build stronger relationships with father - Increasing fathers’ knowledge, awareness & community sensitization can facilitate greater acceptability |

| Couples’ relationships | |||

| Couples’ communication | - Fathers discussed child-related, family livelihood, and financial matters with their partners - Few fathers discussed sexual relations or intimacy with their partners - Many mothers were dissatisfied about the ways their partners (i.e., fathers) communicated with them - Mothers and fathers believed that more positive communication with their partner benefited their children |

- Lack of time spent at home - Fathers’ alcohol consumption - Lack of trust in partner or loyalty in marriage |

- Beliefs about benefits of couple’s communication - Mutual respect and understanding between partners in relationship - Understanding of the benefits of positive communication on child’s development |

| Partner support | - Fathers’ support for partner included financial, practical, emotional, and childcare-related support - Fathers’ practical and childcare-related support were largely circumstantial to the mothers being unavailable; however, some fathers described such support to reduce the burden on their partners - Many parents believed fathers’ financial support was not sufficient and emotional support was also required - Fathers and mothers described the benefits of supportive and loving relationships on their child’s wellbeing and development |

- Lack of time spent at home - Lack of money - Restrictive gender norms |

- Belief that partner support is an expression of gratitude & brings couples closer together - Desire to be a good role model for child - Community support for supportive relationships - Perception that partner support is associated with behaviors of “good fathers” - Couples with mutual respect had more shared decision-making |

| Decision-making | - Fathers are the primary decision makers especially over financial and household matters - Childcare-related decisions seen as primarily mother’s responsibility - Some fathers and mothers believed that the decision making process should be shared between partners |

- Patriarchal gender norms - Intergenerational traditions - Religious beliefs and Tanzanian law justify fathers’ decision-making - Idea that primary breadwinner is de facto the decision-maker |

- Shared decision-making more likely when both parents generated income - Values that support gender equity in decision making |

| Male partner violence | - Fathers were reported as using physical, emotional, and sexual violence against their partners - Many fathers justified the use of physical and emotional violence as a way of reprimanding their partners - Intimate partner violence had direct negative consequences on child wellbeing and development |

- Patriarchal gender norms - Fathers’ alcohol consumption |

- Parental values of peaceful approaches to conflict resolution - Perception that non-violence is associated with behaviors of “good fathers” - Desire to be a good role model for child - Awareness of adverse impact of violence on child wellbeing and development |

| Fathers’ mental health | |||

| Mental health | - Many fathers reported experiencing symptoms of stress and anxiety, and some endorsing depression and even suicidal ideation | - Common sources of mental health concerns included poverty, marital issues, unmanageable child behaviors - Negative coping strategies included fathers’ increased use of alcohol, withdrawal/isolation from family |

- Positive coping strategies included turning to social support networks (friends, partner, parents), spiritual practices, exercise |

Figure 2.

Key identified barriers and enablers to engaged fathering.

Fathers’ caregiving behaviors

Fathers engaged in various caregiving behaviors with and for their young children. Overall, paternal discipline was the most frequently mentioned across all stakeholder groups, followed by play and communication, and lastly other childcare activities and household chores, which few fathers regularly engaged in. It is worth noting that mothers were much more engaged across all these activities than fathers, and other caregivers – including siblings, grandparents, neighbors, and house helps – also played key roles in these caregiving responsibilities.

Discipline.

The majority of mothers, fathers, and community stakeholders believed that child discipline was a primary role of fathers. Although some parents described fathers using positive or non-violent disciplinary strategies (e.g., verbal warnings, explaining to correct bad behaviors), more parents (especially mothers) and community stakeholders reported that fathers used harsh punishment. Parents reported that paternal harsh discipline was commonly used when a child had misbehaved, engaged in unsafe behaviors, made an accident, or was temperamental. Mothers and fathers believed harsh discipline was good for children as a way of learning not to repeat bad behaviors. “When you beat him you make him feel pain. That pain will make him know that what he did is not good, and he will get the same pain when he repeats.” (Father-IDI-#30). Several parents described fathers as “louder” than mothers and more capable of inflicting harsher physical and verbal punishment, which most perceived as effective methods. For example, one mother remarked how children were more fearful of their fathers’ reactions when they are in trouble, “When the child has done wrong, they get scared of their fathers. That’s why they punish more [than mothers]. But the children have been used to us women.” (Mother-IDI-#19)

Play and communication.

Most parents and community stakeholders also reported fathers engaging in play activities with their young children. Common activities included fathers playing hide and side, running around to chase their child, dancing, or using objects like a ball or bottles with their child. Fewer but still roughly half of parents and community stakeholders also noted paternal communication with young children, for example through singing songs or teaching them how to say certain words (e.g., “Mama”, “Baba”). Although the majority of caregivers did not describe fathers’ styles of play and communication as specifically sensitive or responsive in nature, there were a few exceptional instances of paternal interactions that extended beyond cognitive stimulation. “Even with the little time I have got to spend with him, I try to carry him so that he identifies me as his father. I play with him and while I am carrying him, for example, I smile at him, and observe that he responds to it… He feels happy that his father has carried him, and he smiles at me.” (Father-IDI-#6) While the majority of stakeholders endorsed fathers’ roles in some form of child stimulation, a few community stakeholders and mothers particularly in the context of FGDs disagreed and insisted that fathers were generally uninvolved in play or communication activities with young children. For example, one community leader shared, “It is very rare for a father to decide to play with a child, and when that happens then it is a child who has initiated. It is not often a father play with a child. They just observe that a child shouldn’t get hurt.” (Community Leader-IDI-#2)

Other childcare and household responsibilities.

Most caregiving activities broadly pertaining to the child were largely viewed as maternal and not paternal responsibilities. For example, in terms of caregiving for child nutrition, fathers’ roles were mostly discussed in terms of men’s support for their partners (e.g., breastfeeding encouragement) or financial support (e.g., directly purchasing or providing money to partner to buy foods like fruits, vegetables, eggs). While a few fathers did discuss more direct engagement (e.g., feeding the child), father involvement was conditional to when their wives themselves couldn’t feed the child (e.g., due to maternal illness). For child health, some fathers and mothers considered it as a shared responsibility of both parents, but fathers’ roles were discussed mostly in terms of financial support for medicines or clinic fees. A few other parents also noted fathers accompanying their partners to clinic visits or looking after the child when the child is sick. For example, one exceptional father who considered this his role also shared more broadly: “When a child falls ill, both parents are supposed to take the child to the hospital. Even during pregnancy, health specialists advise us to be close to our partners and escort them to the hospital for checkups. It is not right for a father to stay at home and tell his wife to carry their child to the hospital on her own.” (Mixed-FGD-#5)

Besides caregiving activities specifically relating to child nutrition and health, other childcare activities (e.g., holding, bathing, soothing child, changing child’s clothes) and household chores (e.g., sweeping the house, fetching water or firewood) were reported as the primary responsibilities of mothers and not fathers. Several parents again noted that father involvement in these activities were limited to special circumstances, such as when mother is sick or too busy herself. For example, one mother highlighted how rare such activities were for fathers, “99.9% of men do not do [household chores]… it occurs in emergencies like when a mother is very busy, so then a caring father may help.” (Mother-FGD-#1) At the same time, it is worth recognizing that there were a few exceptional parents who highlighted fathers as more regularly engaging in at least a few selected childcare activities. “When she [child] sees me, she comes close, and I carry her even until the point that she sleeps. Normally I go out with her, and take her with me to my workplace. Most of the time I am holding my child” (Father-FGD-#1)

Determinants of fathers’ caregiving behaviors

One of the most common barriers across the various types of paternal caregiving was fathers’ lack of time due to work. Fathers spent most of the day working or looking for work and returned home in the evenings typically when their children are already asleep. “I won’t lie to you, few of them [fathers] play with their children because they don’t have time. First thing they do when they wake up is head directly to the farm. When they come back they eat lunch, then they go back to farming again.” (Community Health Worker-IDI-#4) Parents and community stakeholders explained that fathers consequently had limited opportunities to play and communicate with their children despite most fathers wanting to be more engaged. Some mothers and fathers also explained how lack of time prevented them from engaging in paternal caregiving for nutrition and health, child discipline, and other household activities. Overall, parents perceived direct tension between fathers’ engagement at home with children and their breadwinning roles, with the latter being more valued. Several fathers and mothers believed that the limited time availability of fathers was not consequential because other caregivers (e.g., grandparents, older siblings) had greater roles than men in childcare.

Restrictive gender attitudes and cultural norms were another key barrier to fathers’ nurturing care behaviors that was highlighted by all respondent types. Many mothers accepted that caregiving activities were largely their own responsibilities due to cultural traditions passed over generations. Fathers, mothers, and community stakeholders also highlighted social stigma surrounding fathers’ engagement for certain childcare and household activities (e.g., cooking, feeding). Moreover, many fathers, mothers, and community stakeholders viewed men who engaged in such activities as “helping their wives” as opposed to sharing these tasks fairly and even repeated the idea that fathers would be seen as “bewitched” by their wives. For example, one mother highlighted this shame fathers would feel, “Men feel embarrassed to do such tasks [childcare activities]. He thinks, ‘What if people see me doing this?’ Most men cannot do that. If you ask for their help, they would say that they are leaving for work, but in fact they don’t want to do those activities.” (Mixed-FGD-#1). Other cultural norms, like the acceptability of men’s perpetration of violence, explained fathers’ frequent use of harsh discipline. Both mothers and fathers justified paternal harsh discipline and fathers’ lack of involvement in childcare activities based on their cultural traditions passed over generations.

Knowledge gaps were another barrier with many parents appearing unaware of the benefits of fathers’ nurturing care or the negative consequences of paternal harsh discipline. This was particularly underscored by fathers and community stakeholders who highlighted that sensitizing and providing information to fathers could help increase fathers’ acceptability and participation in childcare.

I would really like for men in this village to be educated on how they should live with their wives. There are many men who believe in patriarchy. Due to that, they cannot do many of the roles that are typically done by women such as cleaning, washing, cooking and other chores thinking that they are superior. Instead of putting all the burden of chores and childcare to women, they should help them. By doing that it will help marital relationships to be peaceful. (Father-IDI-#1)

Notwithstanding, a few exceptional fathers articulated the developmental benefits of stimulation as reasons why they personally engaged and despite restrictive social norms:

Playing and talking to a child has many benefits although our community norms are an obstacle. If you start doing that people will laugh at you. They say you have been bewitched by your wife because in your senses you cannot play with a child, take a child to a clinic, and clean them. …but traditions are fading… As you do that you strengthen your bond with a child. (Fathers-FGD-#2)

Child age was another determinant that was frequently noted by fathers specifically. Some fathers were hesitant to play with their child because they believed infants are too young for such activities. For example, when probed about how he plays with his child, one father shared, “There are no games because the child is too young and so scared when I shake or throw him up.” (Father-IDI-#6) Fathers similarly noted child age-related reluctance when explaining why they did not or ever were nervous about carry their infant or change their clothes. A few fathers also mentioned child age with regards to discipline and the belief that it is inappropriate to physically punish infants but that it was more acceptable later on with preschool-aged children.

Mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs about the meaning of a “good father” as one who not only provides financially, but also participates in various caregiving activities appeared to motivate fathers’ personal engagement in childcare activities. For example, when parents were asked in the FGDs to describe a “good father”, one mother shared, “[A good father] has time for children like playing with the child, reading books for her, going to church together. This could build a bond between a father and the child. The child will always be happy for the father.” (Mothers-FGD-#1) Many of these fathers also viewed play as a way of bringing joy to and making their children happy. Fathers and mothers who held these beliefs were more likely to report fathers’ participation in play and childcare activities and improved father-relationships quality. Finally, the exceptional fathers who engaged in nurturing care activities also reported doing so to show their love and support for their partner and child. “She [wife] may ask me to help her fetch water. I do that because I love her so much. I also help with other small tasks at home. For example, a week ago she was sick so I helped with cooking for the children.” (Father-IDI-#19) Other fathers underscored how busy mothers were with various caregiving responsibilities and desired participating in these tasks to alleviate this burden and even provide their partners with time to rest.

Positive couples’ relationships

Couples’ relationship was discussed in terms of four dimensions: couples’ communication, partner support, decision-making, and male partner violence.

Couples’ communication.

Communication between couples was described by mothers and fathers as mostly revolving around child and family-related matters, but also included financial and work-related topics. When probed during IDIs if couples discussed sexual relations or intimacy, only a few mothers and fathers endorsed this. Fathers’ communication styles with their partners were mostly men instructing or advising their partners, as opposed to couples having mutual exchanges. When asked about their satisfaction levels regarding spousal communication, mothers expressed greater dissatisfaction than fathers with many feeling like fathers were not fulfilling what was planned. “You find that you have talked together, but then you the mother is the one who is hustling alone. So we don’t reach the level we have planned.” (Mothers-IDI-#6) Fathers commonly were frustrated whenever their partners overshared details about their private or personal family matters, especially financial circumstances, with others outside the home. Mothers and fathers believed that the level of communication and openness between couples directly influenced their children. “When you have a good relationship, it will make him [child] smart. He will enjoy seeing father and mother together. If things are not well, like not talking to each other, then a child will not be happy.” (Father-IDI-#22)

Partner support.

Parents discussed how fathers supported their partners in terms of financial, emotional, practical, and childcare-related support. Fathers’ financial support was the most frequently mentioned, such as providing money so their partners could purchase food or clothes for children. Emotional support was described as fathers’ expression of love or use of encouraging words towards their partners. “I feel good when he praised me. Sometimes he tells me, ‘My wife you have done so well, our child is doing good, or you because you have done this our life is going well.’ As a woman you have to be happy [laughing].” (Mother-IDI-#1) Practical support in terms of engaging in household activities or childcare support was the least commonly mentioned. Although fathers’ practical support was largely circumstantial to whenever mothers were unavailable, a few fathers mentioned providing such support to give their partners time for leisure and rest. Furthermore, both mothers and fathers discussed the links between supportive, loving relationships and the healthy development of their children. For example, when asked about how a father’s support for the child’s mother might affect a young child, one father shared: “The child grows happily, healthy, active and with manners from feeling the love from both parents.” (Fathers-FGD-#4)

Decision-making.

Most mothers, fathers, and community stakeholders expressed that fathers were the primary or sole decision-maker, especially over financial and household matters. Although some fathers discussed such matters with their partners, most parents and especially mothers underscored how women’s engagement in discussions did not equate to decision-making power. For example, one mother shared, “He usually involves me in decision making. For example if to sell something or where to farm. But he has the final say in the decision making. If I disagree with something, he just goes ahead with it even with my disagreement.” (Mother-IDI-#7) While these dynamics were also present in childcare-related matters, both mothers and fathers reported that mothers had more decision-making power in this arena because women spent more time at home with children. Some fathers and mothers, however, insisted that fathers should not singularly hold all the power and without including their partners in decision making processes. In particular, several mothers expressed that when fathers make decisions for the entire family on their own, then women and other family members including children cannot “live in peace” and children can grow up fearful of the father.

Male partner violence.

Male perpetration of spousal violence was commonly reported by mothers, fathers, and community stakeholders. Fathers’ use of emotional and physical violence were the most common types and often interrelated. For example, one community leader described how verbal abuse often escalated to physical abuse among male caregivers in his community: “Before using force, verbal exchange begins and after that fathers will use force like beating, pushing and that is violence. Verbal exchange begins and then physical violence.” (Community leader-IDI-#1) Many fathers justified perpetrating violence as a way of reprimanding their partners (e.g., for not completing household chores, suspected infidelity). At the same time, a few mothers and fathers asserted that violence was never used in their own relationships and mentioned how men used alternatives to violence to resolve spousal conflict (e.g., consulting other family members for mediation). While it was relatively the least commonly reported, several mothers, fathers, and community stakeholders did mentioned fathers perpetrating sexual violence as well.

Across all participant groups, respondents articulated the harmful and direct consequences of intimate partner violence on fathers’ parenting behaviors and ECD. For example, they mentioned how fathers’ intimate partner violence was linked to increased parental aggression towards children and less nurturing care practices, which negatively impacts children’s emotional wellbeing and development. “When parents’ relationship is not good, it may affect children’s parenting because parents may beat and punish children unnecessarily just because they are in arguments with their partners. This affects children psychologically.” (Father-IDI-#6)

Determinants of positive couples’ relationships

A key barrier to couples’ communication and partner support was fathers’ limited time and busy work schedules. Parents explained that fathers spent the majority of the day out of the home due to work and then returned home late and too tired to converse with their partners. Additionally, fathers consistently highlighted lack of money as a major barrier to male partner support. Lack of money directly constrained fathers’ capability to provide financial support to their partners, which also impacted other forms of support (e.g., emotional, childcare support). However, couples in households where both parents generated income appeared more likely to openly discuss financial matters like budgeting and collaboratively make decisions together.

Patriarchal gender norms were another pervasive barrier to positive couples’ relationship quality. Some parents believed it was acceptable for men to have exclusive decision-making authority or even perpetrate intimate partner violence because men held a higher position over women in society, and because these power dynamics have been the case in families for generations. Some fathers viewed jointly sharing decisions with their partners or offering emotional or childcare support as emasculating and again restated perceptions of being “bewitched” by their wives. For example, one father elaborated: “I’d feel ashamed if she [wife] had a greater voice than me in the family. In our community, a man is supposed to have a greater voice in his family. I would feel humiliated to my neighbors and friends. Children would not respect me as their father knowing that their mother has a greater voice.” (Father-IDI-#2) A few parents also referenced religion and gender-restrictive laws in justifying why fathers had greater decision-making authority, power, and even control over their wives. A few fathers, including the following example, shared men’s authority was in line with religious beliefs.

“As I said from the beginning a father is the head of the family. It is impossible to have equal positions between a couple. Even God created us in that way. When a father loses his voice in the family it leads to quarrelling. So fathers should be the ultimate decision makers. A wife can provide advice but the decision should come from a father.” (Mixed-FGD-#5)

At the same time, other fathers and primarily in the context of FGDs mentioned positive social norms as driving forces behind why they personally supported their partners and shared decisions. They believed that supporting their partners in household chores would lead to them being viewed favorably by others in the community and noted these actions as characteristics of “good fathers”. For example, one father shared: “Being a good father is working together with your family and sharing household chores. For example, when a mother is washing clothes you can light a fire or wash dishes. You will hear people say you love each other.” (Fathers-FGD-#1) Moreover, these exemplar fathers suggested that their values about positive fatherhood were stronger influences that could even overcome the social stigma that exists surrounding male partner support. “I don’t have to live my life fearing that other men will laugh at me or something else. I only live the way I want. If I want to help my wife, I will do that even if other men will say that I am the one who is being ruled.” (Fathers-FGD-#3)

Fathers’ alcohol use was another frequently reported barrier to couples’ communication and peaceful conflict resolution. Mothers, fathers, and community stakeholders described fathers’ heavy drinking as a catalyst for arguments that resulted in harmful behaviors not only to children but also against partners. For example, one mother shared, “…when he comes home from drinking alcohol, he comes home very violent. He finds any excuse to beat me. He can ask why I haven’t been to the farm, even if I am sick, he will beat me.” (Mother-IDI-#7)

On the other hand, fathers with positive marital relationships expressed love and respect for their partners, desired to support their partners, or be good role models for their children. “Partners need love first. When there is love in your relationship you will have understanding in the things you do. And when a man realizes that his partner loves and care him, he will be taking care of her.” (Fathers-FGD-#1) Also underpinning these positive motivations included fathers’ aligned understanding what their partners desired of them as well as the knowledge of how improved marital relationships could benefit the family. Fathers, mothers, and community stakeholders all suggest that fathers who offer more support, communication, and were non-violent in their partner relationships recognized the direct impacts that couples’ relationships had on their young child’s wellbeing and development. For example, one father shared: “If our relationship is not good the child loses peace, hence I try my best to have good relationship with my wife.” (Father-IDI-#1). Similarly, several parents explained the negative consequences of fathers’ use of violence on children’s wellbeing and how that compromised the quality of father-child relationships.

Fathers’ mental health

Nearly all fathers reported some experience of poor mental health. Parenting stress was the most common type of mental health concern, which fathers discussed in various ways such as “worrying a lot about my child”, “fear about the future”, “not finding happiness around you”, “pain in my heart”, and “not having peace” over matters relating to their child. Many fathers worried about how to fulfill their caregiving roles especially pertaining to financial provisions for the child and family. For example, one father articulated stress as the following, “Stress is when you got nothing. When there is no money that you were expecting to use for the family. And then stress will come. You will think a lot of things. And when I continue thinking and worrying, I feel like my head is in pain. I must sit down first because I start having headache.” (Father-IDI-#7)

In addition to parenting stress, roughly half of fathers reported experiencing more clinical symptoms of potentially depression and/or anxiety, such as “having no energy to work with no reasons”, difficulty sleeping or lack of energy due to their thoughts, feeling “evil spirits”, or consistent feelings of extreme sadness or loneliness. For example, one father used the phrase “thinking too much” (Backe et al., 2021) and described how his accumulating stress caused him to have difficulty sleeping, “I was thinking too much [due to stress] and I had trouble sleeping. There was a time I had so many problems, I went to see a doctor and he told me that I couldn’t sleep because of too much thinking.” (Father-IDI-#5) Multiple fathers and mothers in the context of FGDs along with several community stakeholders even shared how fathers in the community suffered from suicidal ideation.

Although mental health problems were common among most fathers, (it is also worth recognizing that) still a few and minority group of fathers reported having no such experiences of mental health problems. One such case was a father who, when probed about whether he experienced stressed, answered that he chose not to be stressed during challenging circumstances and instead focusing more on the positive and sources of joy in his life. This father continued on to elaborate, “There are days when we struggle and sleep hungry but the family bears with us. I have hope God will bless us and we will have and eat. I feel happy because I am good with my family.” (Father-IDI-#15)

Mothers, fathers, and community stakeholders noted how fathers commonly reverted to negative coping mechanisms when faced with mental health concerns. Alcohol use was the most common negative coping mechanism reported across all respondents along with other negative approaches such as fathers withdrawing and becoming physically and emotionally detached from the family. They believed such poor coping strategies contributed to further family problems.

Mother: He drinks to get over his stress.

Interviewer: Do you believe alcohol relieves stress?

Mother: No, because when you eventually become sober the stress comes back… He drinks because he’s stressed about money, but when goes to drink, that money reduces even more, it doesn’t add. So it doesn’t help him but puts him at a worse situation. (Mother-IDI-#5)

Determinants of fathers’ mental health

The most common source of poor paternal mental health was poverty and lack of money to financially provide for the child or family more broadly, which emerged in both IDIs and FGDs. For example, one father noted, “I get stressed when I think of my family. If I fail [to provide], my family would be in trouble. I ask God to keep me alive so that I take care of my children. I feel so much worried leaving my children, I think about who will take care of them.” (Father-IDI-#18) These stressors were exacerbated especially when health challenges arose for the child or family members, which often led to additional expenses. In FGDs, mothers consistently echoed fathers’ breadwinning roles as a major source of paternal stress: “When there is economic hardship, fathers are stressed on how they can help their children and until they grow up to take care of themselves.” (Mixed-FGD-#2) Another common source of poor mental health for fathers included marital problems, such as not feeling respected by their partner, prolonged conflict in the relationship, or when they suspected their partners were unfaithful in the marriage. Finally, some fathers attributed stress to challenging child behaviors, like when children engaged in dangerous behavior, cried uncontrollably, or were not developing healthily.

In times of mental health challenges, many fathers leaned on their friends, extended family members, and other influential community leaders. Fathers who had strong marital relationships also mentioned their partners as helping them manage stress and encouraging them when they are feeling down. Religion and faith also provided some fathers with psychosocial support; for example, through spiritual practices like prayer or reading scripture and providing them spaces to share their challenges with congregation members. A few fathers also mentioned exercising (e.g., playing football, running) to manage mental health concerns. At the same time, some community stakeholders and mothers believed that few fathers shared their feelings with other individuals when faced with mental health challenges. For example, one community leader mentioned, “Mostly men do not say [their personal struggles] and sometimes they fight with their wives because they don’t want to talk. When women face these problems, they cry and talk to their friends so as to release angry. But men we just die with our problems [laughs].” (Community leader-IDI-#5)

DISCUSSION

We conducted a qualitative formative research study in Mwanza, Tanzania to explore community perceptions about fatherhood, which we conceptualized in terms of fathers’ caregiving, marital relationships, and psychosocial wellbeing. By interviewing a diverse group of respondents, we obtained a broad understanding of how stakeholders made meaning of fathers’ roles along with the perceived barriers and enablers influencing the essence of engaged fathering. Overall, our results highlight the importance of considering the caregiving needs of fathers and the cultural relevance of designing community-based initiatives that target fathers’ caregiving behaviors, marital relationships, and psychosocial wellbeing as a potential approach for improving nurturing care and ECD in the local cultural context.

We found that community members consistently perceived poor couple’s relationships and mental health problems as major priorities affecting fathers. First in terms of poor couple’s relationship, stakeholders discussed how male dominance in decision-making and perpetration of violence against their partners were wide-spread concerns. Moreover, poor couple’s relationships were viewed as constraining paternal engagement with young children. Our results suggest the importance of community-based interventions aimed at enhancing couple’s relationships for family wellbeing in LMICs. For example, a home-visiting intervention in Kenya targeted pregnant women and their male partners to promote couples’ collaboration in health during pregnancy and postpartum and increase couples’ HIV testing and counseling services in Kenya. During each home visit, couples completed communication exercises to practice listening and negotiation skills in order to strengthen couples’ relationship quality (Turan et al., 2018). Another couples intervention in Rwanda used participatory peer-group sessions to encourage fathers to identify non-violent and more respectful ways of resolving partner conflict, facilitate discussions between couples about joint decision-making and equitable distributions of family responsibilities, and provide opportunities for couples to role play positive communication strategies (Doyle et al., 2018). Many prior successful couples relationship programs have been focused in the context of addressing gender-based violence (Sabri et al., 2022), HIV (Hampanda et al., 2022), or sexual and reproductive health and rights (Ruane-McAteer et al., 2020). Our results underscore the relevance of targeting couple’s relationships among parents of young children and suggest that some of these strategies used in these prior program contexts could be similarly incorporated or adapted into caregiving interventions to enhance father engagement and ECD.

Poor mental health – including stress, anxiety, and depression – was another universal concern that affected fathers. Poor mental health was strongly linked with fathers’ caregiving relationships both with their partners and children, which was further compromised through fathers’ common use of negative coping strategies like heavy drinking. These interconnections between fathers’ mental health and caregiving relationships highlight another clustered set of risks that could be targeted jointly to improve fatherhood holistically (Yogman et al., 2016). While there has been increasing attention to integrating maternal mental health components within caregiving interventions for young children (Kim et al., 2021), similar programmatic approaches to support the mental health of male caregivers are limited in LMICs (Jeong et al., 2022). This implementation research gap persists despite studies increasingly documenting how the transition to parenthood and caregiving of young child can be stressful for not only mothers but also fathers (Ramchandani & Psychogiou, 2009).

One noteworthy exception of a paternal mental health program from the context of sub-Saharan Africa is a brief treatment program that integrated behavioral activation, motivational interviewing, and gender norm-transformative strategies for fathers in rural Kenya. The proof-of-concept pilot found initial reductions in fathers’ drinking and depression symptoms and improvements in couple’s and father-child relationships (Giusto et al., 2020). Despite this program being targeted to fathers with histories of problematic drinking behaviors and with school-aged children, these results alongside our formative research findings suggest potential for a universal approach to supporting paternal mental health from a prevention-based, family systems, and gender-transformative perspective among fathers with young children in our study setting of Tanzania.

The extent of fathers’ roles in parenting varied depending on the type of caregiving behavior (e.g., discipline, stimulation, household chores). All stakeholders emphasized that fathers had a major role in child discipline. Paternal engagement in child stimulation was mixed with many fathers unable due to limited time at home. Despite mothers desiring their partners’ support in childcare activities and household chores, father involvement in such activities was limited largely due to restrictive gender norms and cultural traditions. By simultaneously considering multiple types of paternal caregiving behaviors (e.g., stimulation, discipline, household chores), we showcase how fathers’ engagement in caregiving should be conceptualized across a spectrum of activities. Our findings also suggest that paternal engagement in these activities is not static but instead many fathers are willing to increase their participation in more interactive forms of fathering. For example, even though fathers’ engagement in childcare and household chores was relatively rare, many mothers and fathers noted special circumstances under which fathers did assist (e.g., when mothers were ill) and highlighted some “positive deviant” fathers who were more regularly involved in these activities and motivated out of a desire to be a positive role model for their children or demonstrate their love for their partners.

As one of the few studies to qualitatively investigate fathers’ parenting with young children in Tanzania, our findings add to a growing global body of evidence, including from across Eastern and Southern Africa, showing how the contemporary roles of fathers are extending beyond solely the breadwinner and also encompassing more nurturing interactions with young children (Doyle et al., 2014; Funk et al., 2020; Rakotomanana et al., 2021). Various factors including recent demographic transitions (e.g., declines in fertility), socioeconomic development (e.g., increased female laborforce participation), new national policies promoting gender equity, and evolving gender and parenting norms have facilitated such positive trends toward more engaged fatherhood across settings in sub-Saharan Africa and LMICs more broadly (Kato-Wallace et al., 2014; Okelo et al., 2022). At the same time, it is worth underscoring how fathers’ use of violence is still prevalent and largely accepted by mothers and fathers. Integrated programs that combine violence prevention messages together with positive parenting skills and provide caregivers with alternatives to harsh disciplinary practices is likely to facilitate changes across a broader spectrum of paternal caregiving behaviors rather than targeting one single type of paternal caregiving behavior (e.g., reducing fathers’ physical punishment) on its own in isolation.

There are several noteworthy examples of interventions that have targeted and successfully improved multiple paternal caregiving behaviors with young children in LMICs (Jeong et al., 2023). For example, trials from Rwanda (Doyle et al., 2018) and Uganda (Ashburn et al., 2017) have highlighted how engaging fathers in community-based interventions to encourage greater participation in caregiving activities, especially while also addressing restrictive gender norms and power relations between couples, can reduce fathers’ physical punishment and increase their participation in childcare and household activities. While more programs are seeking to increase father involvement in childcare and household activities, still relatively few have incorporated an explicit child developmental focus to specifically target paternal engagement in play and communication. Even less attention has been given in LMICs to supporting fathers’ sensitive and responsive caregiving behaviors, with the exception of a few noteworthy studies that convened fathers together with their children and coached fathers on how to be attentive to their child’s cues and respond appropriately in age-appropriate manners (Luoto et al., 2021; Rempel et al., 2017). Notwithstanding, paternal sensitivity is associated with improved ECD outcomes (Rempel et al., 2017; Rodrigues et al., 2021). Taken together, a comprehensive perspective towards enhancing multiple aspects of father-child engagement and relationships (i.e., increasing paternal play, sensitive and responsive caregiving, positive discipline, childcare and household activities) may be promising for holistically improving paternal caregiving and child outcomes.

We uncovered a constellation of barriers, including poverty, patriarchal social norms, and men’s limited time that cut across the various thematic areas of engaged fathering and spanned multiple levels including the individual, family, and sociocultural levels. Many of these determinants are consistent with those highlighted in other studies from the region about male engagement in other contexts such as maternal and child health (Ditekemena et al., 2012), reproductive health (Kabagenyi et al., 2014), and gender-based violence (Jewkes et al., 2015). For example, one of the most repeated barriers was the perceived pressure for fathers to financially provide and men’s time spent out of home engaging in or seeking employment opportunities, which stakeholders emphasized as limiting fathers’ availability to engage in other family caregiving and support roles (Gibbs et al., 2017). Another consistently noted determinant was restrictive gender attitudes and norms, which was discussed in context of multiple dimensions of fatherhood. Patriarchal values shaped how most fathers and mothers alike viewed childcare and household chores as maternal and not paternal responsibilities and also parents’ conceptualizations of paternal engagement in any such activities (e.g., cooking, bathing the child) as a form of “helping their wives” as opposed to upholding joint responsibilities in the spirit of gender equity. In addition to these factors, we identified other determinants that emerged uniquely within the context of fathers’ parenting with young children. These included barriers such as fathers’ limited awareness of child development and perceptions that infants are too young to receive meaningful paternal care; as well as enablers like many fathers’ desires to provide joy to their young children. These highlight special push and pull factors that should be considered particularly with regards enhancing fathers’ parenting for ECD.

One underexplored yet promising strategy for positively changing fathers’ caregiving behaviors and relationships with their partners and children may be to actively incorporate gender-transformative approaches that address restrictive underlying gender norms and masculinities to promote more engaged fatherhood and equitable distributions of responsibilities (Heise et al., 2019). Although much of the successful gender-transformative interventions have been tested in the field of sexual and reproductive health and violence prevention (Levy et al., 2020), some of the strategies used in these programs – such as encouraging fathers to reflect on how gender roles influence couples’ division of household responsibilities in order to shift commitments towards more equitable and shared distributions of household labor between men and women while also leveraging multiple delivery channels to reach men in various settings (e.g., peer groups delivered by male peer mentors, community events involving various influential stakeholders, and mass media campaigns) – may be similarly promising for incorporating within fatherhood interventions with young children (Doyle et al., 2018).

Finally, our results also revealed how these multiple aspects of fatherhood are not independent but rather interconnected in the lives of fathers. For example, strong marital relationships encouraged fathers’ nurturing care practices with young children; and fathers’ mental health problems in the absence of appropriate coping strategies disrupted relationships with their partners and children. However, few programs have attempted to target these various dimensions in programs offered to male caregivers with young children in LMICs (Jeong et al., 2022). Our study results contribute to this implementation research gap by highlighting the cultural relevance of integrating and simultaneously supporting couples’ relationships, fathers’ mental health, and their parenting behaviors across various spheres (e.g., violence prevention, early learning and simulation, household responsibilities).

Through our investigation of the caregiving roles and experiences of fathers, structural factors namely poverty and financial insecurity repeatedly emerged as major cross-cutting constraints to all dimensions of fatherhood that likely cannot be overcome through educational and social behavior change programs on their own. In many contexts across sub-Saharan Africa, extreme poverty, lack of employment opportunities, and food insecurity are prevalent and directly challenge the identities and expectations of fathers as financial providers, which can further limit paternal engagement with children due to employment seeking reasons (i.e., migratory labor), feelings of discouragement, shame, and stress from not fulfilling their desired roles (Sikweyiya et al., 2017). While we particularly applied a developmental and psychosocial perspective to inform our conceptualization of fatherhood in this study, we acknowledge how other aspects of fathering, such as their roles as financial providers, are also highly relevant cross-culturally and especially in LMICs, and therefore should not be discounted or ignored (Abubakar et al., 2017). As programs aim to determine the best social and behavioral approaches for engaging fathers and supporting their psychosocial caregiving and wellbeing, future research should also consider how to best address structural barriers related to poverty and unemployment through complementary or integrated programs. Optimizing the combination of a gender-responsive social behavior change intervention with social protection and economic strengthening initiatives may have potential to maximize benefits for fathers, family caregiving, and ECD (Lachman et al., 2020).

Our study provides novel qualitative data on parents’ and community stakeholders’ perspectives to highlight the multidimensional nature of fatherhood in the local context of Mwanza, Tanzania. Nevertheless, our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, while some questions of the topic guide were general to explore broad experiences about fatherhood, other questions probed specifically about certain dimensions that were determined a priori (e.g., stimulation, stress, couple’s communication). As a result, it is possible that we did not adequately cover all important aspects of fatherhood. Future research investigating the lived experiences of fatherhood using, for example, a grounded theory perspective may uncover additional insights and roles of fathers. Second, and considering our motivation to investigate men’s dual relationships with both their young child and partner, we sampled biological fathers who lived in the same households as their child and partners. However, we acknowledge that this does not reflect all types of fathers (e.g., social fathers) or family configurations. Future studies should include a more diverse representation of fathers with adequate sampling to explore the extent to which our results are similar or different across other profile types of fathers. Finally, our findings are specific to peri-urban Mwanza and results may not directly apply to other contexts within Tanzania or elsewhere.

CONCLUSION

In this formative research study, we found that fatherhood is multidimensional and encompasses fathers’ caregiving behaviors, couple’s relationships, and fathers’ mental health. We uncovered a multilevel network of determinants that influenced these dimensions of engaged fathering. Our results highlight the cultural relevance and need for multicomponent strategies that jointly and holistically incorporate support for these three pillars of fatherhood in Mwanza, Tanzania. Father-inclusive, gender-transformative parenting interventions may be one promising strategy for addressing the safe and nurturing care of young children. Such initiatives are urgently needed in Tanzania and have the potential to not only improve ECD, but also strengthen families, communities, and support overall national development.

Highlights: