Abstract

BACKGROUND

Diverse genetic backgrounds often lead to phenotypic heterogeneity in cardiomyopathies (CMPs). Previous genotype-phenotype studies have primarily focused on the analysis of a single phenotype, and the diagnostic and prognostic features of the CMP genotype across different phenotypic expressions remain poorly understood.

OBJECTIVES

We sought to define differences in outcome prediction when stratifying patients based on phenotype at presentation compared with genotype in a large cohort of patients with CMPs and positive genetic testing.

METHODS

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, left-dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, and biventricular arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy were examined in this study. A total of 281 patients (80% DCM) with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants were included. The primary and secondary outcomes were: 1) all-cause mortality (D)/heart transplant (HT); 2) sudden cardiac death/major ventricular arrhythmias (SCD/MVA); and 3) heart failure–related death (DHF)/HT/left ventricular assist device implantation (LVAD).

RESULTS

Survival analysis revealed that SCD/MVA events occurred more frequently in patients without a DCM phenotype and in carriers of DSP, PKP2, LMNA, and FLNC variants. However, after adjustment for age and sex, genotype-based classification, but not phenotype-based classification, was predictive of SCD/MVA. LMNA showed the worst trends in terms of D/HT and DHF/HT/LVAD.

CONCLUSIONS

Genotypes were associated with significant phenotypic heterogeneity in genetic cardiomyopathies. Nevertheless, in our study, genotypic-based classification showed higher precision in predicting the outcome of patients with CMP than phenotype-based classification. These findings add to our current understanding of inherited CMPs and contribute to the risk stratification of patients with positive genetic testing.

Keywords: ALVC, ARVC, DCM, genotype, pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants, phenotype

Cardiomyopathies (CMPs) are a heterogeneous group of primary heart diseases characterized by structural and electrical abnormalities that are frequently associated with mutations in disease-related genes.1 Currently, CMPs are classified clinically based on observed phenotypic expression as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), arrhythmogenic right ventricle cardiomyopathy (ARVC), restrictive cardiomyopathy, and other rare forms, each with specific guidelines for treatment.1–3 In the last few years, however, a deeper understanding of the clinical characteristics of these conditions has revealed a more complex scenario. Although HCM represents a distinct disease in terms of pathophysiology, therapeutic treatment, and prognostic assessment,2 DCM and ARVC frequently present overlapping aspects that challenge the conventional classification, leading to the proposal of a single definition, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM), which incorporates ARVC, left-dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ALVC), and biventricular ACM (BiV).4 In DCM and ACM, variability in phenotypic expression can be found within the same family or the same patient over time,5 and several factors, including individual genetic background and exposure to environmental factors, can influence the presenting phenotype and progression of the disease.6

Next-generation sequencing technologies allow the identification of the underlying causative monogenic variant in approximately 30% to 45% of cases of DCM and ACM.7 The correlation between genetic mutations and disease expression is helpful for early diagnosis, improving survival, and reducing morbidity.7 Although genetic substrates do not always predict the same phenotypic disease expression, literature data suggest that specific genes can lead to distinct outcomes, particularly concerning the risks of progressive heart failure (HF), sudden cardiac death (SCD), and arrhythmias.8–13 Previous genotype-phenotype studies have primarily focused on the analysis of a single phenotype, and the diagnostic and prognostic features of CMP genotypes across different phenotypic expressions remain poorly understood.

In this study, we assessed the prognostic prediction of an initial clinical phenotype-based classification vs applying a genotype-based classification in a large cohort of patients with nonhypertrophic CMP phenotypes (DCM, ARVC, ALVC, or BiV) carrying pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants (P/LP) in CMP genes.14,15

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION AND CLINICAL CHARACTERIZATIONS.

We included patients with DCM, ARVC, ALVC, and BiV who underwent genetic testing between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2019, in the Familial Cardiomyopathy Registry, which is a multicenter (Cardiovascular Department, University of Trieste, Italy, and Cardiovascular Institute, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado, USA) ongoing project studying hereditary human cardiomyopathies. Our study received the proper ethical oversight (CERU N.O. 43/2009, 211/2014/Em).

DCM was defined as the presence of impaired left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (<50%) after careful exclusion of secondary causative etiologies.1 ARVC phenotype was defined according to the 2010 Task Force Criteria16; ALVC phenotype was defined as DCM presentation not fulfilling Task Force Criteria for ARVC and with ≥1 of the following criteria at baseline: SCD/major ventricular arrhythmias (MVAs) (defined as resuscitated cardiac arrest, sustained ventricular tachycardia [VT], appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator [ICD] interventions), unexplained syncope, ≥1,000 premature ventricular contractions (PVCs)/24 hours, and ≥50 couplets/24 hours at electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring4,17; BiV was defined as “definite” ARVC plus LVEF <50%.4

Demographic and clinical data, including HF symptoms (New York Heart Association functional class), previous myocardial injury events, and competitive sport activity levels, were collected at the baseline evaluation. Myocardial injury was defined as chest pain, serum cardiac troponin elevation, and the absence of obstructive coronary disease on coronary angiogram.11 Intense exercise (>60 minutes, >3 times/wk and beyond aerobic threshold) participation was classified as participation in competitive sport.11 Detailed information on family history of CMPs and SCD, with a ≥3 generation pedigree, were recorded. Data from 12-lead ECGs and Holter ECG monitoring including ventricular arrhythmias (nonsustained ventricular tachycardia [NSVT]), atrial fibrillation (AF)/atrial flutter, and atrioventricular (AV) blocks were recorded. Echocardiographic left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) dimensions and systolic function were assessed at transthoracic echocardiography following international guidelines.18 LV and RV systolic dysfunction were defined by LVEF <50% and RV fractional area change <35%, respectively.18 Severity of mitral regurgitation was quantified according to current recommendations.19

MOLECULAR GENETICS AND DEFINITION OF GENETIC VARIANTS.

Genetic testing was performed by next generation DNA sequencing of multigene panels, as previously reported.20,21 Gene variants were classified as P/LP according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics criteria (ACMG).22 Only carriers (probands and affected relatives) of P/LP variants in genes with robust disease association14,15,23 were considered eligible for the purposes of this study. Inside the cohort of P/LP carriers, patients were separately grouped by gene or cluster. Sarcomeric genes (SARC) were grouped in a “gene-cluster,” with a functionally homogeneous background, including TNNT2, MYH7, TNNC1, and ACTC1, according to recent evidence15 and as previously reported.20 To obtain statistically meaningful comparisons, genes represented by fewer than 10 patients were excluded from the analysis of clinical characterization and prognostic assessment. The complete list of carriers and genes are in the Supplemental Appendix. To validate the predictivity of genotype and phenotype in a larger population of nonhypertrophic CMPs, a cohort of patients in whom next-generation sequencing tested negative for P/LP variants (P/LP variant-negative cohort) and available follow-up data was considered.

STUDY ENDPOINTS.

The combined study endpoints were as follows: 1) primary outcome: all-cause mortality (D)/heart transplantation (HT); 2) arrhythmic secondary outcome: SCD/MVA; and 3) HF secondary outcome: heart failure–related death (DHF)/HT/left ventricular assist device (LVAD). MVA included ventricular fibrillation, sustained VT (lasting >30 seconds or with hemodynamic instability), and appropriate ICD interventions (shock or antitachycardia pacing on ventricular fibrillation or sustained VT). SCD was defined as witnessed SCD with or without documented ventricular fibrillation, death within 1 hour of acute symptoms, or nocturnal death with no antecedent history of immediate worsening symptoms. The follow-up date for analysis ended at the date of the first endpoint or at the last available contact with the patient.

To assess the performance of the 2 different classifications of patients (phenotype and genotype based) for the clinical categorization and endpoint prediction, patients were differentially grouped according to 3 phenotypes at presentation (DCM, ARVC, and ALVC/BiV) and into genotype categories (as explained in the “Molecular genetics and definition of genetic variants” section).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

Variables were expressed as median (IQR) or counts (%), as appropriate. Comparisons between groups were made by the analysis of variance test on continuous variables using the Brown-Forsythe statistic when the assumption of equal variances did not hold or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test; the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test were calculated for discrete variables. Kaplan-Meier curves for primary endpoint (log-rank test) and cumulative incidence function for the 2 secondary endpoints (Gray’s test) were compared in the first instance for phenotype manifestation. Multivariate analysis was performed using Cox regression models with cause-specific hazard function. As some patients were family members, family was included in the model as clustering factor. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) with packages “survival”24 and “cmprisk.”25

RESULTS

DESCRIPTION OF STUDY POPULATION.

In the selected period, a total of 834 patients affected by DCM (n = 690; 83%), ARVC (n = 70; 8%), and ALVC/BiV (n = 74; 9%) were subjected to genetic testing in our centers. Of these patients, 315 (38%) were carriers of P/LP variants, including 253 DCM (DCM genetic yield: 37%), 30 ARVC (ARVC genetic yield: 43%), and 32 ALVC/BiV (ALVC/BiV genetic yield: 43%). A total of 9 genes (PLN, BAG3, RMB20, SCN5A, DMD, DES, DSG2, DSC2, and NEXN), counting <7 carriers each, were excluded from further analysis (Supplemental Table 1). The final population included 281 patients (218 probands [78%]; 63 affected relatives [22%] belonging to 33 families) (Supplemental Figure 1). In total, 6 gene/gene cluster groups were identified: TTN (n = 95; 34%), SARC (n = 63; 22%), FLNC (n = 37; 13%), PKP2 (n = 30; 11%), LMNA (n = 29; 10%), and DSP (n = 27; 10%) (Figure 1A, Supplemental Table 2). The median age at enrollment was 42 years (IQR: 31–52 years), and 70% of the patients were men. The phenotypic distribution at presentation was characterized predominantly by DCM (n = 224; 80%), followed by ARVC (n = 28; 10%) and ALVC/BiV (n = 29; 10%). Over a median follow-up of 118 months (IQR: 50–188 months), 46 D/HT, 23 DHF/HT/LVAD, and 62 SCD/MVA events were recorded.

FIGURE 1.

Gene Variants and Phenotypic Distribution of the Study Population

A brief description our final study population elucidating the number of patients enrolled with pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants (P/LP) in the selected genes and their phenotypes at enrollment. (A) Histograms showing the number of patient carriers of P/LP variants in each gene or gene-group of our study population. (B) The same histograms with (C) annexed table, reporting the phenotypic distribution of patient carriers of P/LP variants in each gene or gene-group. ALVC = left dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy; ARVC = arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; BiV = biventricular arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; DSP = desmoplakin; FLNC = filamin C; LMNA = lamin; PKP2 = plakophilin 2; SARC = sarcomeric genes; TTN = titin.

SPECTRUM OF CMPs PHENOTYPES AT ONSET.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population according to phenotype. The adopted diagnostic criteria clearly distinguished the phenotypes between the different CMPs. Patients with DCM showed more prominent LV dilatation and LV systolic dysfunction (LVEF ≤35%) (ARVC, n = 0; ALVC/BiV, n = 0; DCM, n = 138 [62%]; P < 0.001), more frequently with left bundle branch block (LBBB) (ARVC, n = 0; ALVC/BiV, n = 0; DCM, n = 38 [17%]; P < 0.001), and were more likely to have moderate-severe mitral regurgitation (ARVC, n = 2 [7%]; ALVC/BiV, n = 3 [10%]; DCM, n = 46 [20%]; P < 0.001). Patients with ARVC and ALVC/BiV had a family history of SCD (ARVC, n = 11 [39%]; ALVC/BiV, n = 14 [48%]; DCM, n = 46 [20%]; P = 0.006), reported engaging in competitive sports (ARVC n = 7 [25%]; ALVC/BiV n = 7 [24%]; DCM n = 5 [2%]; P < 0.001), or had RV dysfunction (ARVC, n = 12 [43%]; ALVC/BiV, n = 12 [41%]; DCM, n = 36 [16%]; P < 0.001). Moreover, NSVT was more frequently detected on Holter ECG monitoring in patients with ALVC/BiV than in patients with ARVC and DCM (ALVC/BiV, n = 14 [48%]; ARVC, n = 7 [25%]; DCM, n = 54 [24%]; P = 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Total Population, According to Phenotype (DCM, ARVC, ALVC/BiV)

| Age, y | 42 (31–52) | 44 (40–45) | 39 (36–50) | 41 (34–45) | 0.308 |

| Gene variants | |||||

| DSP | 27 (10) | 16 (7) | 1 (4) | 10 (34) | <0.001a,b,c |

| PKP2 | 30 (11) | 1 (0.4) | 24 (86) | 5 (17) | |

| FLNC | 37 (13) | 30 (13) | 1 (4) | 6 (21) | |

| LMNA | 29 (10) | 22 (10) | 0 (0) | 7 (24) | |

| SARC | 63 (22) | 60 (27) | 2 (7) | 1 (3) | |

| TTN | 95 (34) | 95 (42) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Caucasian | 276 (98) | 219 (98) | 28 (100) | 29 (100) | 0.523 |

| Male | 197 (70) | 161 (72) | 18 (64) | 18 (62) | 0.432 |

| NYHA functional class | |||||

| I | 148 (53) | 106 (47) | 23 (82) | 19 (65) | 0.028 |

| II | 84 (30) | 72 (32) | 4 (14) | 8 (27) | |

| III | 46 (16) | 43 (19) | 1 (4) | 2 (7) | |

| IV | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Family history of CMP | 170 (60) | 132 (59) | 18 (64) | 20 (67) | 0.507 |

| Family history of SCD | 71 (25) | 46 (20) | 11 (39) | 14 (48) | 0.006b |

| Hypertension | 42 (15) | 36 (16) | 5 (18) | 2 (7) | 0.064 |

| Myocardial injury | 12 (4) | 10 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | 0.351 |

| Competitive sport | 19 (7) | 5 (2) | 7 (25) | 7 (24) | <0.001a,b |

| LBBB | 38 (13) | 38 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.004a,b |

| LVEF ≤35% | 138 (49) | 138 (62) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001a,b |

| LVEF, % | 43 (35–52) | 32 (30–34) | 62 (58–66) | 49 (46–54) | <0.001a,b,c |

| RV dysfunction | 60 (21) | 36 (16) | 12 (43) | 12 (41) | 0.254 |

| LVEDd, mm | 61 (51–70) | 64 (62–66) | 49 (46–51) | 51 (48–54) | <0.001a,b |

| MR moderate-severe | 51 (18) | 46 (20) | 2 (7) | 3 (10) | <0.001a,b |

| Atrial fibrillation | 47 (17) | 35 (16) | 4 (14) | 8 (27) | 0.301 |

| NSVT | 75 (27) | 54 (24) | 7 (25) | 14 (48) | 0.001b |

| AV blocks | |||||

| I | 25 (9) | 20 (9) | 3 (10) | 2(7) | 0.581 |

| II - Mobitz type I | 4 (1) | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.461 | 0.461 |

| II - Mobitz type II | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.828 | 0.828 |

| III | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.686 | 0.686 |

| RAAS-I | 193 (69) | 177 (79) | 6 (21) | 10 (34) | <0.001a,b |

| Beta-blockers | 212 (76) | 183 (83) | 12 (43) | 19 (65) | <0.001a,b |

| ICD implantation (at follow-up) | 136 (48) | 103 (46) | 16 (57) | 17 (58) | 0.327 |

| CRTD implantation/upgrading (at follow-up) | 37 (13) | 37 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.004a,b |

Values are median (IQR) or n (%). Main clinical and instrumental characteristics of study population based on phenotype.

P < 0.02 dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) vs arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC).

P < 0.02 DCM vs left dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ALVC)/ biventricular arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (BiV).

P < 0.02 ARVC vs ALVC/BiV.

AV = atrioventricular; CMP = cardiomyopathy; CRTD = cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; DSP = desmoplakin; FLNC = filamin C; ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LBBB = left bundle branch block; LMNA = lamin; LVEDd = left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MR = mitral regurgitation; NSVT = nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; NYHA = New York Heart Association; PKP = plakophilin; RAAS-I = renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitors (ie, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers); RV = right ventricle; SARC = sarcomeric genes; SCD = sudden cardiac death; TTN = titin.

Each phenotype was associated with multiple causative genes. The largest genetic heterogeneity was identified for DCM (6 genes), followed by ALVC/BiV (5 genes) and ARVC (4 genes). Notably, at the end of the follow-up period, 39 patients with DCM (17% of the DCM cohort) met the criteria for ALVC/BiV diagnosis. In particular, TTN (17%), DSP (15%), LMNA (21%), and FLNC (22%) carriers initially affected by DCM tended to convert their phenotypes (Supplemental Figure 2).

SPECTRUM OF GENOTYPE-PHENOTYPE ASSOCIATIONS.

Gene-based characterization is reported in Table 2, which shows the baseline characteristics of the study population according to gene/gene cluster groups. TTN and SARC variants were mostly associated with the DCM phenotype (TTN: n = 95 DCM [100%]; SARC: n = 60 [95%]), whereas PKP2 variants were mostly associated with ARVC or ALVC/BiV (n = 24 ARVC [80%]; n = 5 ALVC/BiV [17%]) (Figures 1B and 1C). A more heterogeneous phenotypic distribution was detected for 3 genes: DSP (n = 16 patients with DCM [59%]), LMNA (n = 22 DCM [76%]), and FLNC (n = 30 DCM [81%]). Notably, TTN, SARC, and LMNA variant carriers were more frequently affected by severe (LVEF ≤35%) LV dysfunction at enrollment. PKP2 carriers showed isolated RV dysfunction more frequently. LBBB was not present among our carriers of DSP, PKP2, and FLNC variants but was particularly enriched in LMNA carriers. Moreover, LMNA carriers showed a higher prevalence of AF and second-degree AV block.

TABLE 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Population, According to Genotype Distribution

| Age, y | 41 (28–54) | 39 (28–52) | 39 (31–51) | 40 (33–53) | 42 (32–55) | 47 (37–59) | 0.088 |

| Disease | |||||||

| DCM | 16 (59) | 1 (3) | 30 (81) | 22 (76) | 60 (95) | 95 (100) | <0.001a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h |

| ARVC | 1 (4) | 24 (80) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| ALVC/BiV | 10 (37) | 5 (17) | 6 (16) | 7 (24) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Caucasian | 27 (100) | 30 (100) | 37 (100) | 29 (100) | 59 (94) | 94 (99) | 0.074 |

| Sex | 14 (52) | 20 (67) | 27 (73) | 20 (69) | 46 (73) | 70 (74) | 0.362 |

| NYHA functional class | |||||||

| I | 16 (59) | 24 (80) | 23 (62) | 13 (45) | 28 (44) | 44 (46) | 0.140 |

| II | 9 (33) | 5 (17) | 10 (27) | 10 (35) | 19 (30) | 31 (32) | |

| III | 2 (7) | 1 (3) | 4 (11) | 5 (17) | 15 (24) | 19 (20) | |

| IV | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Family history of CMP | 14 (52) | 18 (60) | 26 (70) | 17 (59) | 40 (63) | 55 (58) | 0.710 |

| Family history of SCD | 8 (30) | 9 (30) | 21 (57) | 7 (24) | 6 (9) | 20 (21) | <0.001d,f,i |

| Hypertension | 4 (15) | 5 (17) | 4 (11) | 3 (10) | 7 (11) | 19 (29) | 0.348 |

| Myocardial injury | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 7 (7) | 0.260 |

| Competitive sport | 2 (7) | 8 (27) | 4 (10) | 2 (7) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 0.048j |

| LBBB | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 10 (35) | 9 (15) | 14 (15) | 0.005e |

| LVEF ≤35% | 10 (37) | 0 (0) | 12 (32) | 14 (48) | 39 (62) | 63 (66) | <0.001a,d,e,f,k,j |

| LVEF, % | 40 (29–48) | 61 (56–65) | 42 (30–49) | 33 (26–47) | 30 (21–43) | 32 (23–40) | <0.001a,d,e,k,j |

| RV dysfunction | 6 (22) | 13 (43) | 7 (19) | 5 (17) | 10 (16) | 19 (20) | 0.047d,e,k |

| LVEDd, mm | 57 (54–61) | 48 (46–50) | 59 (57–62) | 60 (56–65) | 63 (60–65) | 66 (63–68) | <0.001a,c,d,e,j,k |

| MR moderate-severe | 5 (18) | 2 (3) | 6 (16) | 4 (14) | 9 (14) | 25 (26) | <0.001a,d,e,j,k |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (7) | 2 (7) | 4 (11) | 9 (31) | 7 (11) | 23(24) | 0.003e,g,l,m |

| NSVT | 10 (37) | 7 (23) | 12 (32) | 10 (34) | 8 (13) | 28 (29) | 0.003b |

| AV blocks | |||||||

| I | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 5 (13) | 6 (21) | 3 (5) | 8 (8) | 0.021g,h,l,n |

| II - Mobitz type I | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | <0.001l,n,m,h |

| II - Mobitz type II | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.031 |

| III | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.401 |

| RAAS-I | 17 (62) | 8 (27) | 23 (62) | 20 (69) | 44 (68) | 81 (85) | <0.001a,d,e,j,k |

| Beta-blockers | 22 (81) | 12 (40) | 28 (75) | 24 (82) | 46 (73) | 80 (84) | <0.001a,d,e,j,k |

| ICD implantation (at follow-up) | 17 (63) | 17 (57) | 15 (41) | 17 (59) | 24 (38) | 46 (48) | 0.174 |

| CRTD implantation/upgrading (at follow-up) | 4 (15) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 8 (28) | 10 (16) | 14 (15) | 0.017e |

Values are median (IQR) or n (%). Main clinical and instrumental characteristics of study population based on genotype.

P < 0.0034 DSP vs PKP2.

P < 0.0034 DSP vs SARC.

P < 0.0034 DSP vs TTN.

P < 0.0034 PKP2 vs FLNC.

P < 0.0034 PKP2 vs LMNA.

P < 0.0034 FLNC vs TTN.

P < 0.0034 LMNA vs SARC.

P < 0.0034 LMNA vs TTN.

P < 0.0034 FLNC vs SARC.

P < 0.0034 PKP2 vs TTN.

P < 0.0034 PKP2 vs SARC.

P < 0.0034 DSP vs LMNA.

P < 0.0034 FLNC vs LMNA.

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

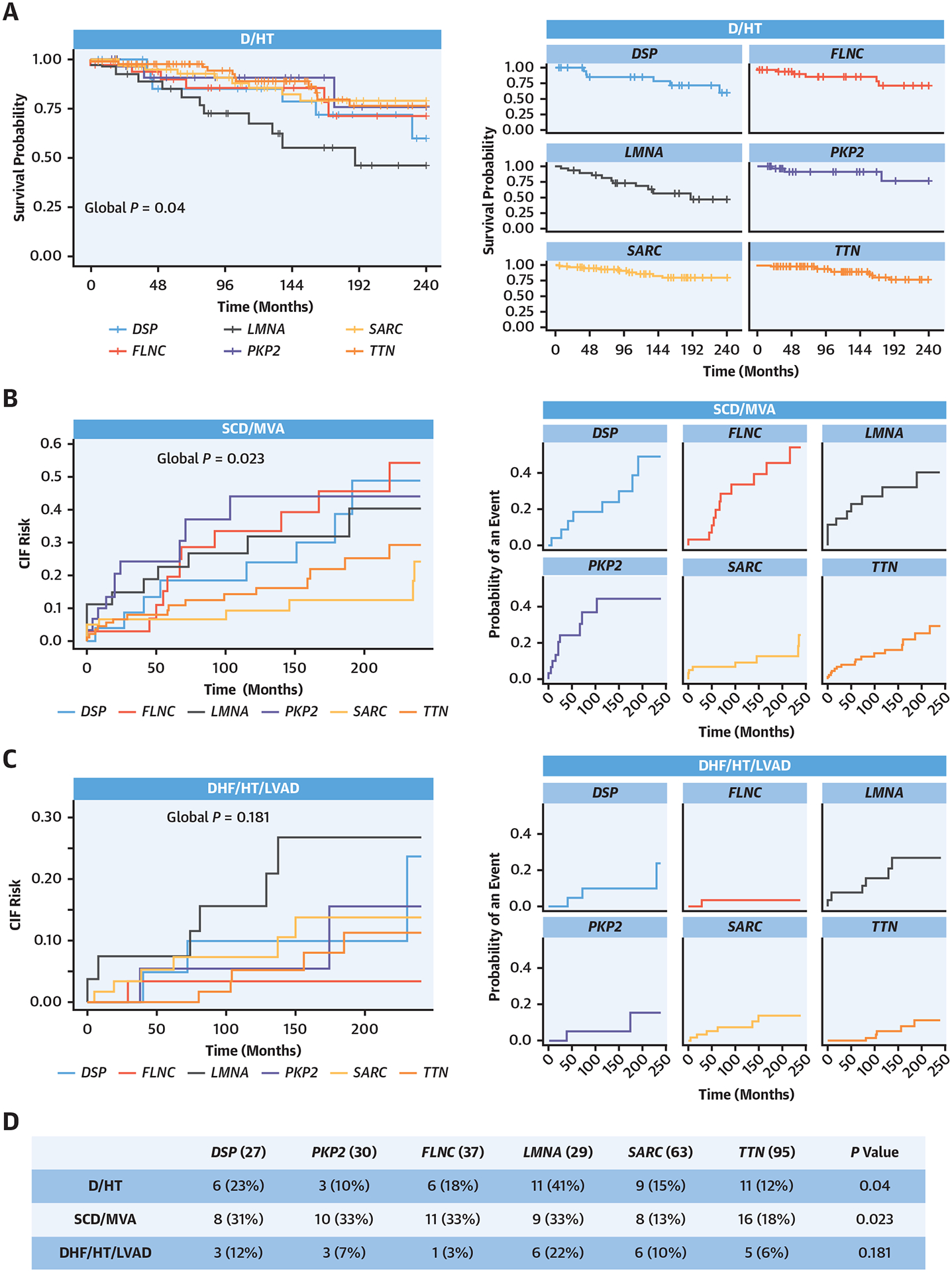

PROGNOSTIC PREDICTION OF PHENOTYPE- VS GENOTYPE-BASED CLASSIFICATION.

Because patients with ARVC and ALVC/BiV showed a comparable number of events (Supplemental Figure 3), they were grouped into the ACM category4 for phenotype-based prognostic analyses. Patients with ACM had a higher number of SCD/MVA events than patients with DCM (ACM, n = 21 [37%]; DCM, n = 41 [18%]; P = 0.001), but no differences in D/HT and DHT/HT/LVAD outcomes were detected (Supplemental Figure 4). The 6 gene groups differed with respect to D/HT and SCD/MVA outcomes (Figure 2A) (D/HT: LMNA n = 11 [41%]; DSP n = 6 [23%]; PKP2 n = 3 [10%]; FLNC n = 6 [18%]; SARC n = 9 [15%]; TTN n = 11 [12%]; P = 0.04) (Figure 2B) (SCD/MVA: LMNA n = 9 [33%]; DSP n = 8 [31%]; PKP2 n = 10 [33%]; FLNC n = 11 [33%]; SARC n = 8 [13%]; TTN n = 16 [18%]; P = 0.023), whereas no significant differences were observed in the risk of DHT/HT/LVAD (Figure 2C, Supplemental Figure 5 with age in the X-axis). LMNA carriers were at the highest risk of developing D/HT and DHF/HT/LVAD. DSP, PKP2, FLNC, and LMNA showed a higher and more comparable number of SCD/MVA events; these 4 genes, if grouped together (“arrhythmic genes”), were associated with a significantly higher risk of D/HT (P = 0.031) and SCD/MVA (P < 0.001) compared with TTN and SARC variants (Figure 3). To properly identify the predictive value of genotype (considered as a carrier of a P/LP variant in one of the “arrhythmic genes”) and phenotype (considered as the presence of DCM vs ACM at presentation) in our cohort, we performed a multivariable analysis, adjusting for familial forms, sex, age, and LVEF at baseline (Table 3). With respect to the primary outcome (D/HT), both genotype-based and phenotype-based classifications, together with LVEF at baseline, were predictive (Table 3), although carriers of arrhythmic gene variants showed the strongest association. Conversely, genotype-based classification was associated with the risk of SCD/MVA among the candidate risk predictors (HR: 2.22; 95% CI: 1.26–3.93), whereas phenotype-based classification did not significantly predict this risk (Table 3). Accordingly, the incidence of SCD/MVA in DCM and ACM phenotypes was similar for patients carrying P/LP variants in DSP, LMNA, and FLNC genes (DSP: MVA 35% in DCM vs 36% in ACM; LMNA: MVA 27% in DCM vs 33% in ACM; FLNC: MVA 38% in DCM and 42% in ACM). The results for DHF/HT/LVAD are reported in Table 3, showing that neither genotype nor phenotype were predictive of this outcome. Finally, when a cohort of 370 patients who were P/LP variant-negative (300 DCM [81%]; 34 ARVC [9%]; 36 ALVC/BiV [10%]) (Supplemental Table 3) was included in the multivariable model to test the predictivity of genotype-based classification in a larger population, the arrhythmic genes were still significantly predictive of the risk of the primary outcome (Supplemental Table 4A: HR: 2.69; 95% CI: 1.52–4.76; and Supplemental Table 4B for SCD/MVA risk: HR: 2.14; 95% CI: 1.30–3.54). P/LP variant-negative status was also mildly associated with the primary outcome (HR: 1.77; 95% CI: 1.10–2.85) (Supplemental Table 4A). In this model, the DCM phenotype, compared with the ACM phenotype, showed a weak association with a lower risk of SCD/MVA (see Supplemental Table 4C for the prediction of DHF/HT/LVAD).

FIGURE 2.

Survival Analysis of the Study Population Based on Genotype

Gene-specific survival curves for each outcome, showing LMNA carriers at the highest risk of D/HT and DSP, PKP2, FLNC, and LMNA with higher and comparable sudden cardiac death (SCD)/major ventricular arrhythmia (MVA) risks. (A) (Left) Kaplan-Meier curves for D/HT endpoint. (Right) The same curves split singularly for each gene/gene group. (B) CIF curves for the SCD/MVA endpoint. (Right) The same curves split singularly for each gene/gene group. (C) CIF curves for the DHF/HT/LVAD endpoint. (Right) The same curves split singularly for each gene/gene group. (D) Table reporting the counts of each endpoint for each gene/gene group. D = all-cause mortality; DHF = heart failure-related death; CIF = cumulative incident fraction; HT = heart transplantation; LVAD = left ventricular assist device; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

FIGURE 3.

Survival Analysis of “Arrhythmic Genes” Compared With TTN and SARC

Patient carriers of “arrhythmic genes” variants (DSP, FLNC, LMNA, and PKP2), were associated with a significantly higher risk of D/HT (P = 0.031) and SCD/MVA (P < 0.001) compared with carriers of TTN and SARC variants. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary endpoint (D/HT). (B) CIF curves for the SCD/MVA secondary outcome. (C) CIF curves for the DHF/HT/LVAD outcome. (D) Table reporting the counts of each endpoint. Abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

TABLE 3.

Multivariable Outcome Analysis of the Study Population

| D/HT | |||

| Sex | 0.65 | 0.36–1.16 | 0.15 |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.091 |

| LVEF | 0.93 | 0.90–0.96 | <0.001 |

| Phenotype (DCM) | 0.28 | 0.11–0.76 | 0.012 |

| Genotype (AG) | 2.45 | 1.25–4.79 | 0.009 |

| SCD/MVA | |||

| Sex | 2.28 | 1.15–4.51 | 0.018 |

| Age | 1.02 | 1.01–1.04 | 0.018 |

| LVEF | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.3 |

| Phenotype (DCM) | 0.53 | 0.25–1.14 | 0.11 |

| Genotype (AG) | 2.22 | 1.26–3.93 | 0.004 |

| DHF/HT/LVAD | |||

| Sex | 0.42 | 0.19–0.90 | 0.026 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.96–1.02 | 0.6 |

| LVEF | 0.95 | 0.91–0.99 | 0.015 |

| Phenotype (DCM) | 0.28 | 0.06–1.29 | 0.10 |

| Genotype (AG) | 1.53 | 0.57–4.07 | 0.4 |

Predictive modeling of phenotype (reference DCM) and genotype (reference TTN/SARC) for the expected outcomes were adjusted for sex (male), age, and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at baseline. Primary outcome (all-cause mortality [D]/heart transplantation [HT]), arrhythmic secondary outcome (SCD/major ventricular arrhythmia [MVA]), and heart failure secondary outcome (heart failure related death [DHF]/HT/left ventricular assist device [LVAD]).

AG = arrhythmic genes; DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

MAIN FINDINGS.

In the present study, the phenotype- and genotype-based CMP classifications were compared in a large cohort of 281 monogenetically determined nonhypertrophic CMPs (DCM, ARVC, ALVC, and BiV) to test their efficiency in predicting outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to encompass multiple phenotypes in a CMP population with P/LP variant genotype.

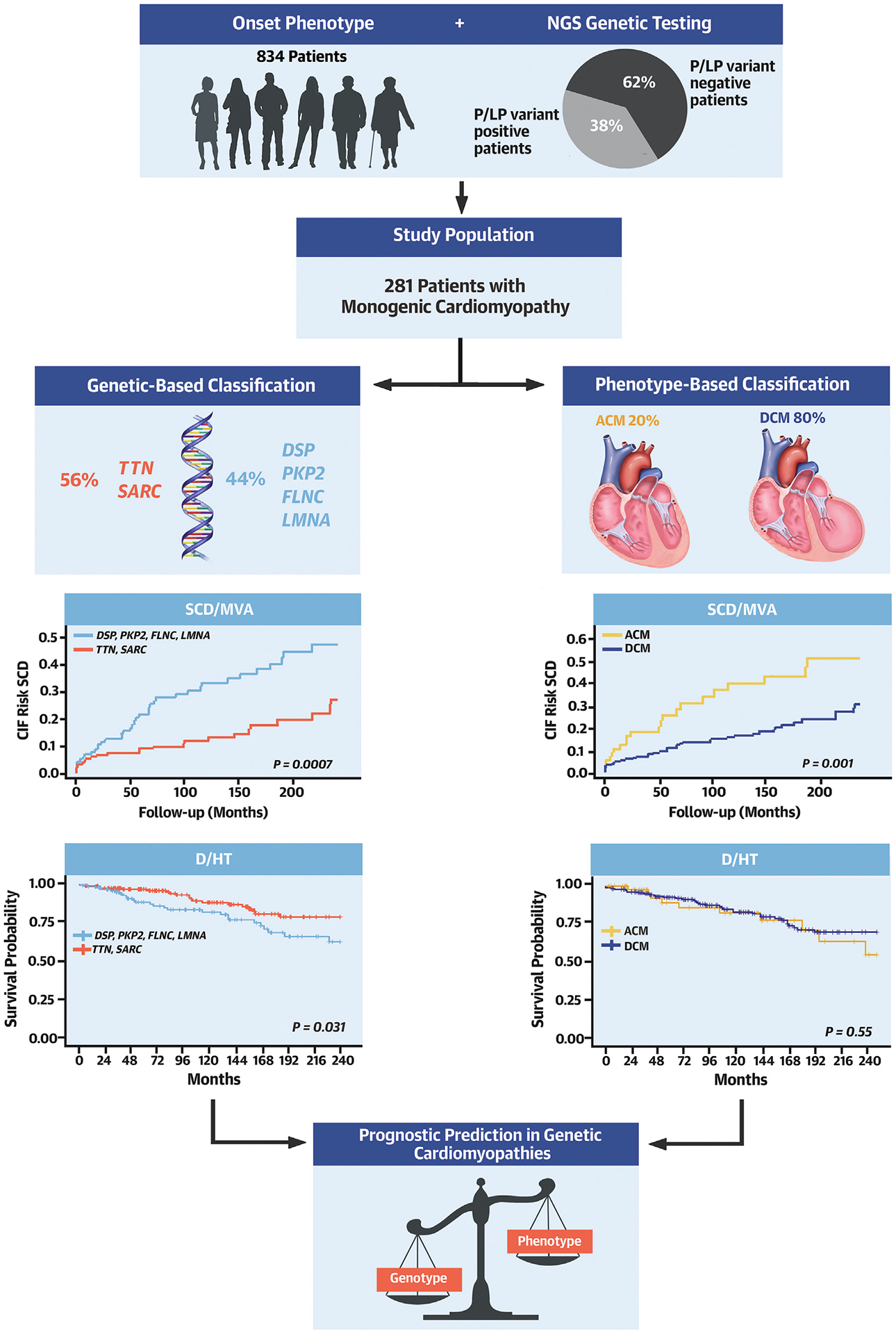

The key findings of our study include the following: 1) a genotype-based classification provides a different but efficient prognostic prediction of genetic CMPs initially classified according to phenotype; 2) the genotype-based classification was found to be particularly effective in predicting the risk of SCD/MVA, whereas the phenotype-based classification was not predictive of this risk; and 3) among the tested genes, LMNA variants were associated with worse outcomes in terms of D/HT and DHF/HT/LVAD compared with other genotypes (Central Illustration).

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION.

Toward Genotype-Based Classification of Nonhypertrophic Cardiomyopathies for Precise Risk Prediction

Approximately one-third of patients with nonhypertrophic cardiomyopathies are found to be carriers of monogenic disease-causing variants. If patients are grouped according to phenotype or genotype, a different risk prediction is obtained. PKP2, FLNC, DSP, and LMNA (arrhythmic genes) are associated with a higher risk of D/HT and SCD/MVA with respect to TTN/SARC genes, regardless of phenotypic presentation. ACM = arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy; ALVC = left dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy; ARVC = arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; B = basal evaluation; BiV = biventricular arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; DCM = dilated cardiomyopathy; D/HT = all-cause mortality/heart transplantation; DSP = desmoplakin; F = follow-up evaluation; FLNC = filamin C; LMNA = lamin; PKP2 = plakophilin 2; P/LP = pathogenic/likely pathogenic SARC = sarcomeric genes; TTN = titin; SCD/MVA = sudden cardiac death/major ventricular arrhythmias.

ROLE OF PHENOTYPE-BASED AND GENOTYPE-BASED CLASSIFICATION.

Even if the commonly adopted phenotype-based CMP classification provides a universally applicable diagnostic approach, the overlap of some phenotypes, especially among DCM, ALVC, and BiV, is frequent. This renders the phenotype-only classification challenging. Furthermore, clinical diagnostic criteria are rapidly evolving to become multiparametric and thus, potentially complex to apply to a single patient by a clinician.20 Finally, the phenotype might be insufficiently accurate for prognostic stratification of CMPs caused by a specific genetic background.26

In our cohort, the appropriateness of the phenotype-based classification was demonstrated to distinguish the typical clinical features of genetic CMPs. However, the application of stringent phenotypic criteria determined the need to modify the classification for almost 20% of patients in the follow-up period (switch from DCM to ALVC/BiV), primarily in carriers of FLNC, LMNA, TTN, and DSP variants. The subsequent application of a genotype-based classification in the same cohort highlighted gene-specific clinical features relevant for future therapeutic management: eg, AV blocks and LBBB were strongly associated with LMNA, as well as AF with LMNA and TTN, and isolated RV dysfunction with PKP2.

Therefore, we consider the genotype-based classification of CMPs to be very informative and to significantly improve the phenotype-based classification. Furthermore, grouping CMPs per causative gene may provide a basis for the implementation of disease-specific research in precision medicine.26

In our cohort, significant phenotypic heterogeneity was confirmed, mostly in the subset of nonsarcomeric genes (DSP, FLNC, and LMNA), possibly reflecting different pathogenetic processes. The same consideration applies to other genes in which the association with phenotype seems more constant (PKP2, mostly ARVC, and TTN and SARC, mostly DCM). Furthermore, current consensus documents recommend targeted genetic testing once the patient’s phenotype has been classified.27,28 However, according to our results, genetic testing contributes to define the diagnosis and should be always considered during the classification process.

OUTCOME PREDICTION AND PROGNOSTIC FEATURES OF SPECIFIC GENES.

Both phenotype- and genotype-based classifications were able to identify patients at higher risk of MVAs during follow-up in our large cohort of genetic CMPs. However, genotype-based classification has proven to be more accurate for SCD/MVA prediction. Most notably, according to this classification, only “arrhythmic genes” were predictive for this outcome upon multivariable analysis, whereas phenotype was not. This finding has a clinical impact, because it implies that when genetic data are available and informative, they allow a better prognostic prediction for SCD/MVA risk than phenotype alone. Consistently, genes that were classified as “arrhythmic” presented the highest phenotypic heterogeneity, and we found no correlation between LVEF and SCD/MVA, as previously shown in some specific genetic form of CMPs.10,11,29 Our results can be considered confirmatory in a more general population of CMPs with available genetic testing and further support recent trends in current guideline recommendations4,30 to consider genotype-positivity for high-risk genes (LMNA, FLNC, DSP, and PKP2) to prompt evaluation for ICD implantation independent of the severity of LV dysfunction.

Furthermore, in our study, both genotype-based and phenotype-based classifications showed a significant correlation with overall mortality (D/HT). This result, according to the genotype-based classification, might be partially related to a faster and worse disease progression in LMNA variant carriers, also clearly showing the DHF/HT/LVAD outcome (Figure 2). Our LMNA population was characterized by a high prevalence of AV blocks, AF, LBBB, and NSVT, and we confirmed a high risk of SCD/MVA, even without LV systolic dysfunction, as already described.12,29,31 In our study, however, the worst global prognosis of LMNA variants, also compared with the other “arrhythmic genes,” was mostly caused by a higher incidence of adverse nonarrhythmic events over follow-up, equally present in all LMNA phenotypes. Finally, TTN and SARC variants were the most represented gene mutations in our study population. Variants in these genes were almost exclusively associated with the DCM phenotype at baseline. Few conflicting reports on DCM related to SARC variants and their outcomes are currently available.32–34 These mutations have been identified in almost 25% of DCM cases and 10% of familial DCM forms, showing a mild disease course and little tendency toward progression.32 However, presentation early in life (from infancy to adolescence)33 and some specific variants34 appear to be characterized by more severe outcomes. In addition, for TTN truncating variants (TTNtv), inconsistent prognostic data regarding MVA35 and response to optimal medical therapy have been reported in previous studies.36 A recent report highlighted a relevant TTNtv arrhythmic burden mainly associated with severe LV systolic dysfunction.13 Our study supports a relatively benign role, in terms of D/HT and SCD/MVA, of TTNtv and SARC variants presenting with the DCM phenotype compared with mutations in other genes.

Finally, the predictivity of genotype for D/HT and SCD/MVA was further strengthened when a cohort of P/LP variant-negative patients was included in the study. In this larger population, P/LP variant-negative status was associated only with the primary outcome, whereas the DCM phenotype, compared with the ACM phenotype, was mildly protective for SCD/MVA.

The available statements by the principal cardiological societies provide phenotypically oriented recommendations.4,27,29,37 Our data, conversely, suggest that an approach in which patients with CMPs are firstly classified according to the underlying genotype (eg, TTN-CMP, FLNC-CMP, DSP-CMP) may further improve their clinical management and prognostic stratification.

STUDY LIMITATIONS.

This was a retrospective study obtained from 2 referral centers for CMPs, mostly dedicated to DCM, which represented 80% of our population. Patients with BiV and ALVC were grouped together because of the limited number of patients in each group. It was a predominantly male population (70%) of mostly White or Caucasian ethnicities.

Due to the statistically insufficient number of individuals, carriers of P/LP variants in rare genes were excluded from the analysis of outcomes, further reducing the spectrum of clinical and prognostic characterization of a larger genetic DCM and ACM population. To contribute to the same effect, a single technology was used for sequencing, leading to the exclusion of falsely negative patients from this analysis because of the intrinsic error rate. Although phenotypic classification seems to be accurate, magnetic resonance imaging data were not considered in this analysis, and there is the potential for unrecognized arrhythmic events that were experienced by patients but not captured by any phenotypic measures, leading to misclassification of some ACM into DCM.

In summary, these results need to be validated in larger, multicenter studies, possibly associated with the availability of magnetic resonance imaging data and multiple genotyping techniques, to further optimize phenotyping and genotyping of the entire cohort.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrates that predicting key clinical outcomes based on the presence of a specific mutated gene is superior to phenotype-based classification in a heterogenous genetic nonhypertrophic CMP population. Independent of the phenotype (ARVC, ALVC, BiV, or DCM), DSP, FLNC, LMNA, and PKP2 predicted a higher rate of SCD/MVA than TTN and SARC P/LP variants, whereas LMNA showed the worst prognosis in terms of nonarrhythmic events. These findings should prompt the inclusion of genotypes, in addition to phenotypes, in the evaluation and management of CMPs.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN PATIENT CARE AND PROCEDURAL SKILLS:

In patients with genetically determined, monogenic, nonhypertrophic cardiomyopathy, genotype-based classification improves risk stratification compared with phenotypic characteristics alone.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE:

The LMNA, FLNC, DSP, and PKP2 genotypes are associated with a high risk of arrhythmic events regardless of the severity of LV dysfunction, whereas the LMNA genotype is associated with the highest risk of nonarrhythmic adverse events.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK:

The pathogenic mechanisms mediating the associations between specific genotypes with adverse outcomes in patients with cardiomyopathies requires further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the patients and family members for their participation in these studies.

FUNDING SUPPORT AND AUTHOR DISCLOSURES

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01HL69071, R01HL116906, and R01HL147064, and American Heart Association grant 17GRNT33670495 (to Dr Mestroni); NIH grant 1K23HI067915; NIH grants 2UM1HG006542 and R01HL109209 (to Dr Taylor); and CRTrieste Foundation and Cassa di Risparmio di Gorizia Foundation (to Dr Sinagra). This work is also supported by NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Colorado CTSA grant numbers UL1 TR002535 and UL1 TR001082. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- ACM

arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy

- ALVC

left-dominant arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy

- ARVC

arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

- BiV

biventricular arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy

- DCM

dilated cardiomyopathy

- LP

likely pathogenic variants

- MVA

major ventricular arrhythmias

- P

pathogenic variants

- SCD

sudden cardiac death

Footnotes

APPENDIX For supplemental tables and figures, please see the online version of this paper.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Elliott P, Andersson B, Arbustini E, et al. Classification of the cardiomyopathies: a position statement from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(2):270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Members WC, Ommen SR, Mital S, et al. 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2020;142(25):558–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corrado D, van Tintelen PJ, McKenna WJ, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: evaluation of the current diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(14): 1414–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Towbin JA, McKenna WJ, Abrams DJ, et al. 2019 HRS expert consensus statement on evaluation, risk stratification, and management of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(11):e301–e372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golnaz G, Jabbari R, Risgaard B, et al. Mixed phenotypes: implications in family screening of inherited cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(Suppl_1), 3772–3772. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merlo M, Cannatà A, Gobbo M, Stolfo D, Elliott PM, Sinagra G. Evolving concepts in dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(2):228–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paldino A, De Angelis G, Merlo M, et al. Genetics of dilated cardiomyopathy: clinical implications. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20(10):83. 10.1007/s11886-018-1030-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Tintelen JP, Entius MM, Bhuiyan ZA, et al. Plakophilin-2 mutations are the major determinant of familial arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;113(13):1650–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamdar F, Garry DJ. Dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(21): 2533–2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gigli M, Stolfo D, Graw SL, et al. Phenotypic expression, natural history, and risk stratification of cardiomyopathy caused by filamin C truncating variants. Circulation. 2021;144(20):1600–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith ED, Lakdawala NK, Papoutsidakis N, et al. Desmoplakin cardiomyopathy, a fibrotic and inflammatory form of cardiomyopathy distinct from typical dilated or arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2020;141(23):1872–1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasselberg NE, Haland TF, Saberniak J, et al. Lamin A/C cardiomyopathy: young onset, high penetrance, and frequent need for heart transplantation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(10):853–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhtar MM, Lorenzini M, Cicerchia M, et al. Clinical phenotypes and prognosis of dilated cardiomyopathy caused by truncating variants in the TTN Gene. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13(10):e006832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James CA, Jongbloed JDH, Hershberger RE, et al. International evidence based reappraisal of genes associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy using the Clinical Genome Resource Framework. Circ Genomic Precis Med. 2021;14:273–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan E, Peterson L, Ai T, et al. Evidence-based assessment of genes in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2021;144:7–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the Task Force Criteria. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(7): 806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spezzacatene A, Sinagra G, Merlo M, et al. Arrhythmogenic phenotype in dilated cardiomyopathy: natural history and predictors of life-threatening arrhythmias. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(10):e002149. 10.1161/JAHA.115.002149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16(3):233–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lancellotti P, Tribouilloy C, Hagendorff A, et al. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurgitation: an executive summary from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(7):611–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gigli M, Merlo M, Graw SL, et al. Genetic risk of arrhythmic phenotypes in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(11): 1480–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dal Ferro M, Stolfo D, Altinier A, et al. Association between mutation status and left ventricular reverse remodelling in dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2017;103(21):1704–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015 175 2015;17(5):405–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazzarotto F, Tayal U, Buchan RJ, et al. Reevaluating the genetic contribution of monogenic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2020: 387–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Therneau T A Package for Survival Analysis in R. R package version 3.2–13. 2021. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray B cmprsk: Subdistribution Analysis of Competing Risks. R package version 2.2–10. 2020. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cmprsk [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arbustini E, Narula N, Dec GW, et al. The MOGE(S) classification for a phenotype-genotype nomenclature of cardiomyopathy: endorsed by the World Heart Federation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(22):2046–2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musunuru K, Hershberger RE, Day SM, et al. Genetic testing for inherited cardiovascular diseases: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Genomic Precis Med. 2020;13(4):E000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landstrom AP, Kim JJ, Gelb BD, et al. Genetic testing for heritable cardiovascular diseases in pediatric patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Genomic Precis Med. 2021;14(5):e000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Rijsingen IAW, Arbustini E, Elliott PM, et al. Risk factors for malignant ventricular arrhythmias in lamin A/C mutation carriers: a European Cohort Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(5):493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Priori SG, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: the Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(41):2793–2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor MRG, Fain PR, Sinagra G, et al. Natural history of dilated cardiomyopathy due to lamin A/C gene mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(5): 771–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Villard E, Duboscq-Bidot L, Charron P, et al. Mutation screening in dilated cardiomyopathy: prominent role of the beta myosin heavy chain gene. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(8):794–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakdawala NK, Dellefave L, Redwood CS, et al. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy caused by an alpha-tropomyosin mutation: the distinctive natural history of sarcomeric dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(4): 320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mogensen J, Murphy RT, Shaw T, et al. Severe disease expression of cardiac troponin C and T mutations in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(10): 2033–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verdonschot JAJ, Hazebroek MR, Derks KWJ, et al. Titin cardiomyopathy leads to altered mitochondrial energetics, increased fibrosis and longterm life-threatening arrhythmias. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(10):864–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luk K, Bakhsh A, Giannetti N, et al. Recovery in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy with lossof-function mutations in the titin gene. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(6):700–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilde AAM, Semsarian C, Márquez MF, et al. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA)/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS)/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS) expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for cardiac diseases. Europace. 2022;24(8):1307–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.