Abstract

PURPOSE:

Knowledge of thyroid eye disease (TED) is based on predominantly Caucasian populations. To date, no studies in the United States examine the presentation in Black and Hispanic patients. The purpose of this study is to introduce the presentation of TED in two previously undescribed populations.

METHODS:

This is a retrospective, cross-sectional, chart review study of patients with TED at a tertiary center using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist. The main outcome measure for severity was the European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy 2016 Severity Scale.

RESULTS:

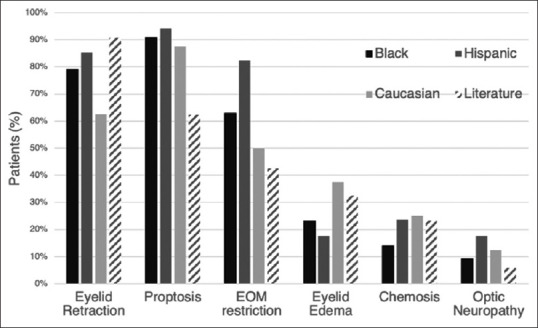

Of the 2905 charts reviewed, 99 met the inclusion criteria. The mean age was 51 (standard deviation 16) years with 78% women. Race was 49.4% Black, 39.1% Hispanic, 9.2% Caucasian, and 2.3% Asian. Smoking rates were 25% current smokers and 14% former smokers. Manifestations were proptosis (94% Hispanic and 91% Black), eyelid retraction (85% Hispanic and 79% Black), extraocular muscle (EOM) restriction (79% Hispanic and 63% Black), eyelid edema (41% Hispanic and 30% Black), chemosis (24% Hispanic and 14% Black), and optic neuropathy (18% Hispanic and 9% Black). Overall, disease severity was 22% mild, 65% moderate to severe, and 13% sight-threatening. Older patients had increased rates of optic neuropathy (P = 0.04). Younger patients had increased rates of proptosis (P = 0.02). Socioeconomic status was not associated with disease severity (P = 0.67).

CONCLUSION:

Hispanic and Black patients with TED presented with higher than previously established rates of proptosis, EOM restriction, and optic neuropathy. Including research of different races broadens understanding of presentation and management, improving patient outcomes.

Keywords: Black, diversity, extraocular muscle restriction, eyelid edema, Hispanic, optic neuropathy, proptosis, race, retraction, thyroid eye disease

Introduction

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is an inflammatory orbitopathy that variably produces periocular edema, pain, proptosis, eyelid retraction, restrictive strabismus, and optic neuropathy. Current understanding of TED is based on studies in primarily Caucasian patient populations, such as those on presentation, the negative effects of smoking, and intravenous steroid therapy.[1-3] However, diagnostic delays and poorer outcomes can result from inadequate diversity in research.[4-6]

Race affects the presentation of TED. A decreased likelihood of upper lid retraction and greater likelihood of exophthalmos was found in Asian patients.[7] Lower severity and optic neuropathy rates were seen in Black Nigerians.[8] The single study of Hispanic patients reported only thyroid status, not oculoplastics findings.[9]

To date, there are few studies on TED in Black or Hispanic patients and none on clinical presentation. This study is the first to describe TED presentations in each of these populations.

Methods

This is a retrospective, cross-sectional study of patients with TED presenting to one oculoplastic surgeon at a tertiary care center in New York City using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist. This Institutional Review Board approved study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and waived consent. Photographic consent was obtained by the authors. The electronic medical record was searched for patients evaluated between January 2017 and July 2018, who met criteria for both “thyroid disease” and “eye disorder” [Appendix 1]. Two reviewers independently screened charts (TG, MM), with discordance addressed by a third reviewer (AB). The study size was selected to reflect the typical patient volume seen at a tertiary referral center over the course of 18 months. Inclusion followed Bartley and Gorman’s TED criteria, requiring meeting at least two of the three following categories: (1) autoimmune thyroid dysfunction or thyroid antibodies without thyroid dysfunction, (2) one or more exam findings: eyelid retraction with temporal flare, proptosis, restrictive strabismus, compressive optic neuropathy, fluctuating eyelid edema/erythema, chemosis/caruncular edema, and (3) radiographic evidence of fusiform rectus muscle enlargement.[10] Patients with thyroid cancer were excluded.

Demographics

Demographics collected included age, sex, race, health insurance type, and referring physician specialty. Insurance was collected as Medicaid (government-subsidized health insurance for low-income individuals), whether primary or secondary or other.

History

History collected included thyroid diagnosis (hyper-, hypo-, or euthyroid), previous thyroid treatment (medical, thyroidectomy, radioactive iodine, and other), presence and duration of previous TED diagnosis, and tobacco smoking status (current, past, or never smoker).

Symptoms

TED symptoms collected included the presence of eyelid or conjunctival swelling/redness, eye bulging, double vision, and decrease in vision. The duration of TED symptoms before TED diagnosis was documented and grouped into three categories: <1 year, 1–5 years, or >5 years. The study aimed to capture active TED in the <1 year category and quiescent TED in the >5 years category with the intervening years as a mixed category.

Physical exam

Physical examination findings collected at each visit included visual acuity, extraocular motility, proptosis, eyelid retraction, eyelid injection and edema, and conjunctival/caruncular chemosis and injection. Proptosis on the initial visit was defined and recorded qualitatively as present or absent based on comparison to old photographs. Proptosis on subsequent visits was defined as increased Hertel exophthalmometer measurements. Retraction was defined as the distance between the upper or lower eyelid margin to the corneal reflex (MRD1 or MRD2, respectively) being >5 mm. The presence of optic neuropathy was defined as visual loss, not attributable to other intraocular disorders, presenting with visual acuity loss, relative afferent pupillary defect, noncongenital dyschromatopsia, or a reliable and reproducible visual field defect. For statistical analysis, symptoms and examination findings were treated as a binary variable (present or not present).

Serology

Laboratory evidence of thyroid dysfunction and TED was based on the presence of an abnormal result outside of the institutional reference range for the following: thyroid stimulating hormone, free thyroxine, anti-thyroid peroxidase, thyroglobulin, anti-thyroglobulin, thyrotropin binding inhibitor immunoglobulin, and thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin.

Severity

TED severity was stratified based on the 2016 European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy (EUGOGO) classification system.[11] Optic neuropathy was assigned a score of severe, while moderate was used for those without optic neuropathy but with upper eyelid retraction >6.5 mm, TED-related diplopia symptoms impacting daily activities, proptosis requiring surgical decompression, or orbital/ocular inflammation and/or pain significant enough to justify the risks of 12 weeks of steroid infusions.[3] Those who did not meet these criteria were assigned a score of mild. For analysis, the worst severity score recorded for each patient was utilized.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were described as means and standard deviation (SD) for the continuous variables and count and percentage for the categorical variables. The bivariate association between risk factors and TED severity was examined in consideration of the ordinal nature of the EUGOGO score (severe, moderate, and mild), using the Kruskal–Wallis test for categorical variables and the Spearman rank correlation test for continuous and ordinal variables. An ordinal logistic regression was fitted for the EUGOGO score with predictors, such as demographic and behavioral variables. The rate of physical examination findings by race was compared between the races in our study using the Fisher’s exact test and to the previously reported prevalence in the literature using the proportion test.[1] The bivariate association between risk factors in TED presentation was examined using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the t-test for continuous variables. Further, a Firth logistic regression on each TED presentation was fitted against age, sex, race, current smoking status, thyroid treatment, and the duration of TED at diagnosis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed through R 3.5.2 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Demographics and thyroid disease

Of the 2905 patients manually reviewed, 100 patients met the diagnostic criteria for TED. One patient was excluded for a thyroid cancer diagnosis. Of 99 patients, the mean age was 51 (SD = 16) years with 78% women [Table 1]. Race was 49.4% Black, 39.1% Hispanic, 9.2% Caucasian, and 2.3% Asian. Most referrals were made from ophthalmology (74%) followed by endocrinology (17%). Duration of TED symptoms was >1 year in most patients (65%). Only 5% had been previously diagnosed with TED before presentation at this tertiary care center.

Table 1.

Study demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | Percentage of patients (n) |

|---|---|

| Mean age at TED diagnosis, years (SD) | 51 (16) |

| Female | 78 (77) |

| Male | 22 (22) |

| Race* | |

| Black | 49 (43) |

| Hispanic | 39 (34) |

| Caucasian | 9.2 (8) |

| Asian | 2.3 (2) |

| Insurance status | |

| Medicaid | 55 (54) |

| Other (medicare and private) | 46 (45) |

| Referring physician specialty† | |

| Ophthalmology | 74 (70) |

| Endocrinology | 17 (16) |

| Primary care physician | 6.4 (6) |

| Otolaryngology | 1.1 (1) |

| Dermatology | 1.1 (1) |

| Tobacco smoking status‡ | |

| Never | 60 (59) |

| Current | 25 (25) |

| Former | 14 (14) |

| Thyroid abnormality§ | |

| Hyperthyroid | 90 (85) |

| Hypothyroid | 7.5 (7) |

| Euthyroid | 2.1 (2) |

| Thyroid treatment|| | |

| Methimazole | 41 (35) |

| Radioactive iodine | 35 (30) |

| Thyroidectomy | 16 (14) |

| None | 7.0 (7) |

| Duration of TED at diagnosis¶ (years) | |

| <1 | 35 (29) |

| 1–5 | 44 (37) |

| Over 5 | 21 (18) |

| Prior diagnosis of TED | |

| Yes | 5.0 (5) |

| No | 96 (95) |

| Laboratory manifestation | |

| Abnormal TSH | 81 (70) |

| Abnormal TSI | 73 (35) |

| Abnormal free T4 | 71 (60) |

| Abnormal anti-TPO | 57 (25) |

| Abnormal TBII | 47 (15) |

| Abnormal thyroglobulin | 25 (8) |

*Unspecified for 12, †Unspecified for 5, ‡Unspecified for 1, §Unspecified for 5, ||Unspecified for 12, ¶Unspecified for 15. SD: Standard deviation, TSH: Thyroid stimulating hormone, TSI: Thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin, Anti-TPO: Anti-thyroid peroxidase antibody, TBII: Thyrotropin-binding inhibitory immunoglobulin, EOM: Extraocular muscle, TED: Thyroid eye disease, n: Number of patients

Thyroid eye disease clinical manifestations

The most common presentation in Hispanic and Black patients with TED was proptosis, which was defined as a documented change from baseline [94% and 91%, respectively; Figure 1, Table 2]. Only 85% of Hispanic and 79% Black patients had eyelid retraction. Extraocular muscles (EOM) restriction was seen in 79% of Hispanic patients and 63% Black patients. TED-related optic neuropathy was higher in our study patients (18% of Hispanic patients and 9% of Black patients). In the current study, most patients were characterized as having moderate to severe disease (91% of Hispanic patients and 95% of Black patients) as defined by the EUGOGO classification system. Patients, who presented with TED symptoms at an older age, had increased rates of optic neuropathy (P = 0.04), while younger patients had increased rates of proptosis (P = 0.02). TED severity was not significantly associated with the previously established risk factors of gender and tobacco use.

Figure 1.

Rates of thyroid eye disease clinical findings in Black, Hispanic, and Caucasian patients from this study population versus previously established rates in the literature.[2] EOM: Extraocular muscle

Table 2.

Rates of thyroid eye disease clinical findings in Black and Hispanic patients

| Manifestation | Black patients | Hispanic patients |

|---|---|---|

| Proptosis | 91% (CI=77.9%–97.4%) | 94% (CI=80.3%–99.3%) |

| Eyelid retraction | 79% (CI=64%–90%) | 85% (CI=68.9%–95%) |

| EOM restriction | 63% (CI=46.7%–77%) | 79% (CI=62.1%–91.3%) |

| Eyelid edema/injection | 30% (CI=17.2%–46.1%) | 41 (CI=24.6%–59.3%) |

| Chemosis | 14% (CI=5.3%–27.95%) | 24% (CI=10.7%–41.2%) |

| Optic neuropathy | 9% (CI=2.6%–22.1%) | 18% (CI=6.8%–34.5%) |

EOM: Extraocular muscle, CI: Confidence interval, TED: Thyroid eye disease

Thyroid eye disease manifestations and risk factors

A longer duration of TED symptoms was associated with higher rates of eyelid retraction (P = 0.05), proptosis (P = 0.02), and EOM restriction (P = 0.04), but lower rates of chemosis (P = 0.05) and edema (P = 0.01). This remained the case after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, and RAI (radioactive iodine) treatment. Increased TED symptom duration trended toward increasing overall disease severity, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.06), and the association between symptom duration and optic neuropathy was not statistically significant (P = 0.52).

Discussion

The presentation of TED in Hispanic or Black patients has not been established in the literature. However, racial variability in presentation is clearly demonstrated in Figure 2, which shows eyelid erythema and edema from active TED in three patients: Caucasian, Hispanic, and Black. Given that differences in disease presentation can lead to delays in diagnosis or obtaining proper treatment, the literature must be expanded to include more races.[4,7,8] To date, this study is the first to examine TED manifestation rates in Hispanic patients, as well as Black patients.

Figure 2.

Variability in presentation of skin erythema and edema in three active thyroid eye disease patients of different races: (a) Caucasian, (b) Hispanic, and (c) Black

Thyroid eye disease clinical findings

In Hispanic and Black patients, this study found that proptosis is the most common presentation. This finding contrasts with prior understanding of TED, as previous studies of primarily Caucasian patients found eyelid retraction to be the most common.[1] In our study, 94% of Hispanic patients and 91% of Black patients had proptosis, which is higher than the 63% reported in a previous study of Caucasian patients.[1] The often-reported retraction rate of 90% is based on Caucasian patients and is higher that this study’s retraction rates (85% Hispanic and 79% Black).[1]

EOM restriction was also found to be higher in Hispanic and Black patients as compared to Caucasian patients. In this study, EOM restriction was seen in 79% of Hispanic patients, 63% Black patients, and 50% of Caucasian patients, the latter which was similar to previously reported rates in Caucasian patients, 43%.[1] Given the paucity of literature examining Hispanic or Black patients with TED, there is no previously established proptosis, retraction, or EOM restriction rate for comparison, but these findings highlight the differences in presentation in this population.

TED-related optic neuropathy and overall disease severity, as defined by the EUGOGO Classification, was also higher in our study patients than the literature has reported based on mostly Caucasian patients. For TED-related optic neuropathy, published rates are 3%–6%,[1] yet 18% of Hispanic patients and 9% of Black patients had TED-related optic neuropathy. Similarly, most patients in the current study cohort (78%) were characterized as having moderate to severe disease (91% of Hispanic patients and 95% of Black patients), which contrasts with prior distribution studies in Caucasian patients. In an Italian study of patients with newly diagnosed autoimmune hyperthyroidism, just, 5.8% had moderate to severe disease.[12] The overall increased severity of disease in our study likely reflects a combination of the nature of patients referred to a subspecialty practice at a tertiary center and the greater disease severity in this study population.

Patient demographics

The majority of the study cohort were women (78%) with autoimmune hyperthyroidism (90%), similar to rates previously reported.[13] Prior studies have published associations of increased severity of TED with increasing age, male gender, cigarette smoking, and lower socioeconomic class.[14-16] In our study, patients, who presented at an older age had increased rates of optic neuropathy (P = 0.04), while those who presented younger had increased rates of proptosis (P = 0.02). This is similar to prior studies, where younger patients typically demonstrated orbital fat expansion and proptosis, while older patients tended to suffer from enlargement of the EOM with lower rates of proptosis.[15,17] The combination of increasing demand for space by muscle enlargement without accommodation by forward movement of the eye is hypothesized to be the reason for the increased risk of optic neuropathy in older patients.[17,18] While tobacco use was not associated with increased severity in this study, this relationship may have been complicated by the overall high percentage of smokers in this study cohort, as 25% of this study were smokers and 14% were former smokers compared to the national prevalence of 14%.[19] The overall higher rate of current/former tobacco users may have contributed to the overall higher severity of this study cohort. In this study, no sex or socioeconomic associations were found.

Although there was no direct correlation to socioeconomic class, only 5% of patients had been previously diagnosed with TED by an outside provider before evaluation by the specialty clinic. This may reflect limited access to clinicians trained in diagnosing TED and/or differences in disease presentation. Increased duration of symptoms in this study was associated with statistically significant higher rates of retraction, EOM restriction, and proptosis. Given the increased duration of symptoms, as well as higher rates of proptosis, EOM restriction, and optic neuropathy in this study cohort, there is a need for prompt referral and close follow-up for Hispanic and Black patients with TED. Closer attention would allow for earlier intervention, potentially decreasing limitations to daily activities and increasing quality of life.

Study limitations

Limitations include its noninterventional study design and the self-reported nature of data, such as smoking status, race, and duration of TED symptoms, which are subject to reporting biases. For this paper, the term “Hispanic” was used as a category of race, as is commonly done in the medical community. However, categorizing based on race is limited, as a single race may not adequately reflect the variable genetic backgrounds of everyone identifying within that race. Several related topics, such as the incidence of TED, likelihood to seek care, and the location of sought care are interesting factors but were beyond the scope of this study. In addition, TED studies are currently limited due to lack of standardization in grading disease and severity. Larger prospective studies, which match for age, sex, race, and socioeconomic factors are needed to validate the effect of race on the clinical findings of TED.

Conclusion

Recognizing findings in patients with a variety of skin pigmentations, orbital depths, and eyelid shapes is essential to appropriate management. This study revealed higher rates of proptosis, EOM restriction, and optic neuropathy in both Hispanic and Black patients than previously described in primarily caucasian populations. Expanding inclusiveness in healthcare, medical education, and scientific research is important not only to improve outcomes but also as a reflection of values in the medical community.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Electronic medical record search criteria

“]Eye Disorder” ICD codes

G73.7 - Myopathy in diseases classified elsewhere

H02.02 - Mechanical entropion of eyelid

H02.021 - Mechanical entropion of right upper eyelid

H02.022 - Mechanical entropion of right lower eyelid

H02.023 - Mechanical entropion of right eye, unspecified eyelid

H02.024 - Mechanical entropion of left upper eyelid

H02.025 - Mechanical entropion of left lower eyelid

H02.026 - Mechanical entropion of left eye, unspecified eyelid

H02.531 - Eyelid retraction right upper eyelid

H02.532 - Eyelid retraction right lower eyelid

H02.533 - Eyelid retraction right eye, unspecified eyelid

H02.534 - Eyelid retraction left upper eyelid

H02.535 - Eyelid retraction left lower eyelid

H02.536 - Eyelid retraction left eye, unspecified eyelid

H02.539 - Eyelid retraction unspecified eye, unspecified lid

H02.841 - Edema of right upper eyelid

H02.842 - Edema of right lower eyelid

H02.843 - Edema of right eye, unspecified eyelid

H02.844 - Edema of left upper eyelid

H02.845 - Edema of left lower eyelid

H02.846 - Edema of left eye, unspecified eyelid

H02.849 - Edema of unspecified eye, unspecified eyelid

H04.121 - Dry eye syndrome of right lacrimal gland

H04.122 - Dry eye syndrome of left lacrimal gland

H04.123 - Dry eye syndrome of bilateral lacrimal glands

H04.129 - Dry eye syndrome of unspecified lacrimal gland

H05 - Disorders of orbit

H05.0 - Acute inflammation of orbit

H05.00 - Unspecified acute inflammation of orbit

H05.01 - Cellulitis of orbit

H05.011 - Cellulitis of right orbit

H05.012 - Cellulitis of left orbit

H05.013 - Cellulitis of bilateral orbits

H05.019 - Cellulitis of unspecified orbit

H05.02 - Osteomyelitis of orbit

H05.021 - Osteomyelitis of right orbit

H05.022 - Osteomyelitis of left orbit

H05.023 - Osteomyelitis of bilateral orbits

H05.029 - Osteomyelitis of unspecified orbit

H05.03 - Periostitis of orbit

H05.031 - Periostitis of right orbit

H05.032 - Periostitis of left orbit

H05.033 - Periostitis of bilateral orbits

H05.039 - Periostitis of unspecified orbit

H05.04 - Tenonitis of orbit

H05.041 - Tenonitis of right orbit

H05.042 - Tenonitis of left orbit

H05.043 - Tenonitis of bilateral orbits

H05.049 - Tenonitis of unspecified orbit

H05.1 - Chronic inflammatory disorders of orbit

H05.10 - Unspecified chronic inflammatory disorders of orbit

H05.11 - Granuloma of orbit

H05.111 - Granuloma of right orbit

H05.112 - Granuloma of left orbit

H05.113 - Granuloma of bilateral orbits

H05.119 - Granuloma of unspecified orbit

H05.12 - Orbital myositis

H05.121 - Orbital myositis, right orbit

H05.122 - Orbital myositis, left orbit

H05.123 - Orbital myositis, bilateral

H05.129 - Orbital myositis, unspecified orbit

H05.2 - Exophthalmic conditions

H05.20 - Unspecified exophthalmos

H05.21 - Displacement (lateral) of globe

H05.211 - Displacement (lateral) of globe, right eye

H05.212 - Displacement (lateral) of globe, left eye

H05.213 - Displacement (lateral) of globe, bilateral

H05.219 - Displacement (lateral) of globe, unspecified eye

H05.22 - Edema of orbit

H05.221 - Edema of right orbit

H05.222 - Edema of left orbit

H05.223 - Edema of bilateral orbit

H05.229 - Edema of unspecified orbit

H05.23 - Hemorrhage of orbit

H05.231 - Hemorrhage of right orbit

H05.232 - Hemorrhage of left orbit

H05.233 - Hemorrhage of bilateral orbit

H05.239 - Hemorrhage of unspecified orbit

H05.24 - Constant exophthalmos

H05.241 - Constant exophthalmos, right eye

H05.242 - Constant exophthalmos, left eye

H05.243 - Constant exophthalmos, bilateral

H05.249 - Constant exophthalmos, unspecified eye

H05.25 - Intermittent exophthalmos

H05.251 - Intermittent exophthalmos, right eye

H05.252 - Intermittent exophthalmos, left eye

H05.253 - Intermittent exophthalmos, bilateral

H05.259 - Intermittent exophthalmos, unspecified eye

H05.26 - Pulsating exophthalmos

H05.261 - Pulsating exophthalmos, right eye

H05.262 - Pulsating exophthalmos, left eye

H05.263 - Pulsating exophthalmos, bilateral

H05.269 - Pulsating exophthalmos, unspecified eye

H05.3 - Deformity of orbit

H05.30 - Unspecified deformity of orbit

H05.31 - Atrophy of orbit

H05.311 - Atrophy of right orbit

H05.312 - Atrophy of left orbit

H05.313 - Atrophy of bilateral orbit

H05.319 - Atrophy of unspecified orbit

H05.32 - Deformity of orbit due to bone disease

H05.321 - Deformity of right orbit due to bone disease

H05.322 - Deformity of left orbit due to bone disease

H05.323 - Deformity of bilateral orbits due to bone disease

H05.329 - Deformity of unspecified orbit due to bone disease

H05.33 - Deformity of orbit due to trauma or surgery

H05.331 - Deformity of right orbit due to trauma or surgery

H05.332 - Deformity of left orbit due to trauma or surgery

H05.333 - Deformity of bilateral orbits due to trauma or surgery

H05.339 - Deformity of unspecified orbit due to trauma or surgery

H05.34 - Enlargement of orbit

H05.341 - Enlargement of right orbit

H05.342 - Enlargement of left orbit

H05.343 - Enlargement of bilateral orbits

H05.349 - Enlargement of unspecified orbit

H05.35 - Exostosis of orbit

H05.351 - Exostosis of right orbit

H05.352 - Exostosis of left orbit

H05.353 - Exostosis of bilateral orbits

H05.359 - Exostosis of unspecified orbit

H05.4 - Enophthalmos

H05.40 - Unspecified enophthalmos

H05.401 - Unspecified enophthalmos, right eye

H05.402 - Unspecified enophthalmos, left eye

H05.403 - Unspecified enophthalmos, bilateral

H05.409 - Unspecified enophthalmos, unspecified eye

H05.41 - Enophthalmos due to atrophy of orbital tissue

H05.411 - Enophthalmos due to atrophy of orbital tissue, right eye

H05.412 - Enophthalmos due to atrophy of orbital tissue, left eye

H05.413 - Enophthalmos due to atrophy of orbital tissue, bilateral

H05.419 - Enophthalmos due to atrophy of orbital tissue, unspecified eye

H05.42 - Enophthalmos due to trauma or surgery

H05.421 - Enophthalmos due to trauma or surgery, right eye

H05.422 - Enophthalmos due to trauma or surgery, left eye

H05.423 - Enophthalmos due to trauma or surgery, bilateral

H05.429 - Enophthalmos due to trauma or surgery, unspecified eye

H05.5 - Retained (old) foreign body following penetrating wound of orbit

H05.50 - Retained (old) foreign body following penetrating wound of unspecified orbit

H05.51 - Retained (old) foreign body following penetrating wound of right orbit

H05.52 - Retained (old) foreign body following penetrating wound of left orbit

H05.53 - Retained (old) foreign body following penetrating wound of bilateral orbits

H05.8 - Other disorders of orbit

H05.81 - Cyst of orbit

H05.811 - Cyst of right orbit

H05.812 - Cyst of left orbit

H05.813 - Cyst of bilateral orbits

“]Thyroid Disorder” ICD codes

O99.280 - Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases complicating pregnancy, unspecified trimester

O99.281 - Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases complicating pregnancy, first trimester

O99.282 - Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases complicating pregnancy, second trimester

O99.283 - Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases complicating pregnancy, third trimester

P96.89 - Other specified conditions originating in the perinatal period

R94.6 - Abnormal results of thyroid function studies

E00.9 - Congenital iodine-deficiency syndrome, unspecified

E02 - Subclinical iodine-deficiency hypothyroidism

E03.1 - Congenital hypothyroidism without goiter

E03.3 - Postinfectious hypothyroidism

E03.4 - Atrophy of thyroid (acquired)

E03.5 - Myxedema coma

E03.8 - Other specified hypothyroidism

E03.9 - Hypothyroidism, unspecified

E05 - Thyrotoxicosis (hyperthyroidism)

E05.0 - Thyrotoxicosis with diffuse goiter

E05.00 - Thyrotoxicosis with diffuse goiter without thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.01 - Thyrotoxicosis with diffuse goiter with thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.1 - Thyrotoxicosis with toxic single thyroid nodule

E05.10 - Thyrotoxicosis with toxic single thyroid nodule without thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.11 - Thyrotoxicosis with toxic single thyroid nodule with thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.2 - Thyrotoxicosis with toxic multinodular goiter

E05.20 - Thyrotoxicosis with toxic multinodular goiter without thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.21 - Thyrotoxicosis with toxic multinodular goiter with thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.3 - Thyrotoxicosis from ectopic thyroid tissue

E05.30 - Thyrotoxicosis from ectopic thyroid tissue without thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.31 - Thyrotoxicosis from ectopic thyroid tissue with thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.4 - Thyrotoxicosis factitial

E05.40 - Thyrotoxicosis factitia without thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.41 - Thyrotoxicosis factitia with thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.8 - Other thyrotoxicosis

E05.80 - Other thyrotoxicosis without thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.81 - Other thyrotoxicosis with thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.9 - Thyrotoxicosis, unspecified

E05.90 - Thyrotoxicosis, unspecified without thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E05.91 - Thyrotoxicosis, unspecified with thyrotoxic crisis or storm

E06 - Thyroiditis

E06.0 - Acute thyroiditis

E06.1 - Subacute thyroiditis

E06.2 - Chronic thyroiditis with transient thyrotoxicosis

E06.3 - Autoimmune thyroiditis

E06.4 - Drug-induced thyroiditis

E06.5 - Other chronic thyroiditis

E06.9 - Thyroiditis, unspecified

E07.1 - Dyshormogenetic goiter

E07.9 - Disorder of thyroid, unspecified

E31.0 - Autoimmune polyglandular failure

E34.9 - Endocrine disorder, unspecified

E83.52 - Hypercalcemia

E89 - Postprocedural endocrine and metabolic complications and disorders, not elsewhere classified

Z83.49 - Family history of other endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases

Z86.39 - Personal history of other endocrine, nutritional and metabolic disease

Z86.69 - Personal history of other diseases of the nervous system and sense organs

Z91.89 - Other specified personal risk factors, not elsewhere classified

References

- 1.Bartley GB, Fatourechi V, Kadrmas EF, Jacobsen SJ, Ilstrup DM, Garrity JA, et al. Clinical features of Graves'ophthalmopathy in an incidence cohort. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:284–90. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartalena L, Marcocci C, Tanda ML, Manetti L, Dell'Unto E, Bartolomei MP, et al. Cigarette smoking and treatment outcomes in Graves ophthalmopathy. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:632–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-8-199810150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahaly GJ, Pitz S, Hommel G, Dittmar M. Randomized, single blind trial of intravenous versus oral steroid monotherapy in Graves'orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5234–40. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lester JC, Taylor SC, Chren MM. Under-representation of skin of colour in dermatology images:Not just an educational issue. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1521–2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, Okoye GA, Linos E. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:593–5. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buford K, Rivera KV, Wood AM, Sandozi A, Schulman A. Representation in figures depicting penile pathology in urologic textbooks. Urology. 2022;163:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim SL, Lim AK, Mumtaz M, Hussein E, Wan Bebakar WM, Khir AS. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical features of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy in multiethnic Malaysian patients with Graves'disease. Thyroid. 2008;18:1297–301. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogun OA, Adeleye JO. Severe ophthalmological complications of thyroid disease are rare in Ibadan, Southwestern Nigeria:Results of a pilot study. Ophthalmol Eye Dis. 2016;8:5–9. doi: 10.4137/OED.S32169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figuerola AC, Ball-Burstein S, Nava-Castaneda A, Graue-Moreno G. Systemic and immune thyroid status in hispanic patients with recently diagnosed thyroid eye disease at the Conde Valenciana Institute of Ophthalmology –Mexico city. A 7 year review. [[Last accessed on 2022 Mar 21]];IOVS ARVO J Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015 56:567. Available from: https://www.iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2335726 . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartley GB, Gorman CA. Diagnostic criteria for Graves'ophthalmopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119:792–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72787-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartalena L, Baldeschi L, Boboridis K, Eckstein A, Kahaly GJ, Marcocci C, et al. The 2016 European Thyroid Association/European Group on Graves'orbitopathy guidelines for the management of Graves'orbitopathy. Eur Thyroid J. 2016;5:9–26. doi: 10.1159/000443828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanda ML, Piantanida E, Liparulo L, Veronesi G, Lai A, Sassi L, et al. Prevalence and natural history of Graves'orbitopathy in a large series of patients with newly diagnosed Graves'hyperthyroidism seen at a single center. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:1443–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bothun ED, Scheurer RA, Harrison AR, Lee MS. Update on thyroid eye disease and management. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:543–51. doi: 10.2147/opth.s5228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edmunds MR, Huntbach JA, Durrani OM. Are ethnicity, social grade, and social deprivation associated with severity of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy? Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30:241–5. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perros P, Crombie AL, Matthews JN, Kendall-Taylor P. Age and gender influence the severity of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy:A study of 101 patients attending a combined thyroid-eye clinic. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1993;38:367–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tellez M, Cooper J, Edmonds C. Graves'ophthalmopathy in relation to cigarette smoking and ethnic origin. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1992;36:291–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazim M, Goldberg RA, Smith TJ. Insights into the pathogenesis of thyroid-associated orbitopathy:Evolving rationale for therapy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:380–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein JD, Childers D, Gupta S, Talwar N, Nan B, Lee BJ, et al. Risk factors for developing thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy among individuals with Graves disease. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:290–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.5103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, Cullen KA, Day H, Willis G, et al. Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults – United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1013–9. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]