Abstract

Kurt Schneider has played a leading role in shaping our current view of schizophrenia, placing certain manifestations of delusions and hallucinations at the center of the disorder, especially ideas of persecution and voice-hearing. The first part of this review summarizes Schneider’s original ideas and then traces how the different editions of the DSM merged aspects of Kraepelin’s, Bleuler’s, and Schneider’s historical concepts. Special attention is given to the transition from the DSM-IV to the DSM-5, which eliminated much of Schneider’s original concept. In the second part of the article, we contrast the current definition of hallucination in the DSM-5 with that of Schneider. We present empirically derived arguments that favor a redefinition of hallucinations, much in accordance with Schneider’s original ideas. We plea for a two-dimensional model of hallucinations that represents the degree of insight and perceptuality, ranging from thoughts with full “mineness” via perception-laden thoughts and intrusions (including “as if” experiences”) to hallucinations. While we concur with the DSM-5 that cognitions that are indistinguishable from perceptions should be labeled as hallucinations, we suggest expanding the definition to internally generated sensory phenomena, including those with only partial resemblance to external perceptions, that the individual considers real and that may lie at the heart of a subsequent delusional superstructure.

Keywords: first-rank symptoms, schizophrenia, Kurt Schneider, positive symptoms, ego boundaries

From Kraepelin and Bleuler to Schneider: A Strong Break, Not Continuity

Kurt Schneider’s concept of first-rank symptoms, originally published in the late 1930s1 but not popularized until the late 1940s,2 has perhaps shaped our current view of schizophrenia more than the concepts of any other psychiatrist before him. While Emil Kraepelin3 is often credited with having separated psychosis (then called dementia praecox) from affective disorders and Eugen Bleuler4 with having coined the cumbersome label schizophrenia (initially as a plural term), the impact of their ideas has faded over the years. Kraepelin’s notions, in particular, have been diluted in the different editions of the DSM, as we will discuss in detail later. The current focus on what we now call “positive symptoms,”5–8 especially delusions of persecution and (auditory) hallucinations, is in large part owing to Schneider’s influence, radically replacing the former Kraepelinean emphasis on neurodegeneration or intellectual deterioration3 and Bleuler’s 4 A’s (association, affect, ambivalence, and autism; the term 4A’s is simply an abbreviation and is not used in any derogative sense.).4 Schneider’s ideas were not a refinement but a strong break with former ideas, and they were not embraced by everyone but were met with criticism and even outright rejection by some influential scientists, for example, Seymour Kety9:

Schneider established a new syndrome with features that are more easily perceived and described, and which therefore show a higher degree of inter-rater reliability, features which are economically put into checklists and fed into computers. That syndrome may be more prevalent, have a more favorable outcome, and be more responsive to a wide variety of treatments, but it is not schizophrenia. (p. 425)

Clearly, Schneider was not the first to describe hallucinations and delusions in the disorder, but earlier they had been treated either as accessory symptoms4 or as features of only one of many subtypes of “dementia praecox.”

This review pursues two major aims. In the first part, we summarize Schneider’s original ideas and trace which aspects were incorporated into the DSM and which were not or were included but distorted. We also examine Kraepelin’s and Bleuler’s influence over the different editions of the DSM, with special attention given to the significant transition from DSM-IV to DSM-5, which eliminated much but not all of Schneider’s ideas. In the second part, based on empirical evidence, we present arguments and data in favor of a redefinition of hallucinations in the DSM in accordance with the original ideas of Schneider. In sum, the article aims to provide a review of the essence of Schneider’s ideas, their implementation in classification guidelines, the equivocal evidence for his concept, and, finally, empirical evidence that may bridge the gap between his views and the current definition of hallucinations in the DSM-5.

What Did Schneider Really Say?

Schneider summarized the essence of his ideas about schizophrenia in the chapter “Zyklothymie und Schizophrenie” (Cyclothymia and Schizophrenia) in his book Klinische Psychopathologie (Clinical Psychopathology):

We have emphasized these symptoms of first-rank importance above and illustrated them with examples. Following the order in which we have reviewed them, they are: audible thoughts, voices heard arguing, voices heard commenting on one’s actions; the experience of influences playing on the body (somatic passivity experiences); thought-withdrawal and other interferences with thought; diffusion of thought; delusional perception and all feelings, impulses (drives), and volitional acts that are experienced by the patient as the work or influence of others. When any of these modes of experience is undeniably present and no basic somatic illness can be found, we may make the decisive clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia. (Schneider2 pp. 133–134)

A common denominator of all first-rank symptoms is a loss of boundaries of the ego-environment-barrier (a “‘lowering’ of the ‘barrier’ between the self and the surrounding world, the loss of the very contours of the self,” p. 134). Others10 have grouped first-rank symptoms into two phenomena: passivity experiences and hallucinations, further characterized by a diminished sense of self-presence and “mineness.” While Schneider deemed first-rank symptoms decisive in discriminating schizophrenia from cyclothymia, he stipulated that a diagnosis of schizophrenia might still be determined in the absence of first-rank symptoms (“Symptoms of first-rank importance do not always have to be present for a diagnosis to be made. [ . . . ] We are often forced to base our diagnosis on the symptoms of second-rank importance, occasionally and exceptionally on mere disorders of expression alone, provided these are relatively florid and numerous,”2 p. 135).

Schneider’s ideas were based on clinical observation rather than on solid empirical evidence (for an early criticism, see Ref. 11) and were driven by his strong desire to pinpoint those symptoms that can be reliably assessed, to the detriment of those symptoms (irrespective of their true importance) that show only poor interrater correspondence (“No doubt, other schizophrenic symptoms of first-rank importance might be found but we are limiting ourselves to those which can be clearly defined and can be grasped without too great difficulty in a clinical investigation,”2 p. 134). He did not intend to establish a new theory of schizophrenia, and his nomenclature was in fact essentially atheoretical; he primarily intended to foster reliable (differential) diagnoses (“The value of these symptoms is, therefore, only related to diagnosis; they have no particular contribution to make to the theory of schizophrenia,” p. 133; Schneider’s interest in the reliability of diagnosis was likely not driven by clinical aspects alone; he developed his concept at a time when a diagnosis of schizophrenia in Germany would lead to sterilization and, until 1945, could even result in death.12) . Yet, later empirical studies, which we discuss below, have in fact challenged the specificity of first-rank symptoms.

Part 1. Schneider and the DSM: In and Out

The DSM-I and the DSM-II: A Selection of Kraepelin’s and Bleuler’s Writings

Although Schneider’s writings were available in English in 1959, they were not included in the DSM until its third edition, which was published in 1980. In the DSM-I, issued in 1952, the influence of Bleuler and Kraepelin was predominant. The DSM-I contained a set of types of schizophrenia largely attributable to Kraepelin: the simple, hebephrenic, catatonic, and paranoid types. These types were in fact only some of the many put forward by Kraepelin during his career.3 The term dementia praecox is mentioned; on p. 117 it is even given as the primary term for the disorder: “Dementia praecox (Schizophrenia)”. Kraepelin’s concept of intellectual or neurocognitive degeneration remains at least implicit in the mention of “regressive behavior, and in some [patients] [ . . . ] a tendency to ‘deterioration’” (p. 26). The DSM-I defines the syndrome as “intellectual disturbances in varying degrees and mixtures” (p. 26).

The second edition of the DSM, published in 1968, contained many of the ideas found in the DSM-I. Although the term dementia praecox is no longer actively used, the concept is still present, such as in the description of “schizophrenia, simple type”:

This psychosis is characterized chiefly by a slow and insidious reduction of external attachments and interests and by apathy and indifference leading to impoverishment of interpersonal relations, mental deterioration, and adjustment on a lower level of functioning. (p. 33, emphasis by the authors)

It should be emphasized that, unbeknownst to many, even Kraepelin3 conceded that some of his patients with dementia praecox fully recovered; irreversible intellectual deterioration was thus not inevitable for those with the condition.

In the first two editions of the DSM, hallucinations were mentioned as a symptom. Importantly, however, auditory forms did not receive any special weight.

Bleuler’s influence on the DSM-II, especially pertaining to associative loosening, is visible in single symptoms such as “unpredictable disturbances in the stream of thought” (p. 26). His concept of “latent schizophrenia” is picked up as well. The DSM-II also followed Bleuler’s view that delusions and hallucinations are secondary symptoms:

Disturbances in thinking are marked by alterations of concept formation which may lead to misinterpretation of reality and sometimes to delusions and hallucinations, which frequently appear psychologically self-protective. (p. 33)

DSM-III and III-R: Roll Over Kraepelin: The Growing Influence of Schneider

In 1980, the DSM-III introduced radical changes by including Schneider’s concept alongside the Kraepelinean typology. Again, the essence of dementia praecox, although in a more diluted form, is evident in the continued use of the term deterioration (“Schizophrenia, especially when chronic, may be associated with some degree of intellectual deterioration,” p. 110; criterion B: “Deterioration from a previous level of functioning in such areas as work, social relations and self-care”). Kraepelin’s typological concept was upheld but with growing reservations; the DSM-III acknowledged that these types, unlike the usual requirement for a type, are not stable (“The types reflect cross-sectional clinical syndromes. Some are less stable over time than others, and their prognostic and treatment implications are variable,” p. 190). In addition, some diagnostic labels were changed (eg, hebephrenic type was changed to disorganized type).

Bleuler’s ideas were waning as well. For example, the concept of latent schizophrenia, while still mentioned, was essentially abandoned (“The approach taken here excludes illnesses without overt psychotic features, which have been referred to as Latent, Borderline, or Simple Schizophrenia. Such cases are likely to be diagnosed in this manual as having a Personality Disorder such as Schizotypal Personality Disorder,” p. 181) and, like “schizophrenia, simple type,” its diagnosis was no longer encouraged.

In this edition, Schneider’s first-rank symptoms, particularly certain forms of auditory hallucinations, were given special weight for the first time:

The major disturbances in perception are various forms of hallucination. Although these occur in all modalities, by far the most common are auditory, frequently involving voices the individual perceives as coming from outside the head. The voices may be familiar, and often make insulting statements. The voices may be single or multiple. Voices speaking directly to the individual or commenting on his or her ongoing behavior are particularly characteristic. Command hallucinations may be obeyed, at times creating danger for the individual or others. (pp. 182–183)

The DSM-II labeled first-rank delusional phenomena as bizarre delusions (“content is patently absurd and has no possible basis in fact,” p. 188), such as delusions of being controlled, thought broadcasting, thought insertion, or thought withdrawal (of note, Schneider did not refer to these phenomena as “bizarre”). Criterion 4 in the DSM-III also strongly reflected Schneider’s ideas: “auditory hallucinations in which either a voice keeps up a running commentary on the individual’s behavior or thoughts, or two or more voices converse with each other” (p. 188).

Unlike the previous versions, the third edition of the DSM contained an appendix with definitions. Hallucinations were defined as follows (with similar phrasing in the DSM III-R):

A sensory perception without external stimulation of the relevant sensory organ. A hallucination has the immediate sense of reality of a true perception, although in some instances the source of the hallucination may be perceived as within the body. […]

There may or may not be a delusional interpretation of the hallucinatory experience. […] Strictly speaking, hallucinations indicate a psychotic disturbance only when they are associated with gross impairment in reality testing. […] Transient hallucinatory experiences are common in individuals without mental disorder. (DSM-III, pp. 359–360)

The DSM-III-R sharpened and simplified the criteria for schizophrenia further in the direction of Schneider’s ideas, placing strong diagnostic weight on bizarre delusions (eg, thought broadcasting, being controlled by a dead person) and voice-hearing. In the DSM-III, Schneiderian hallucinations (eg, comments on the individual’s behavior or thoughts, two or more voices conversing with each other) and bizarre delusions were no more significant than other types of delusions and hallucinations, but in the DSM-III-R either bizarre delusions or Schneiderian hallucinations were needed to confirm a diagnosis of schizophrenia. In contrast, other psychotic phenomena (delusions, other types of hallucinations, incoherence, or marked loosening of associations, catatonic behavior, flat, or grossly inappropriate affect) were sufficient for diagnosis only if at least two of these phenomena occurred at the same time.

In the DSM-III-R, the Kraepelinean heritage was watered down even more. While the term deterioration could still be found (“The development of the active phase of the illness is generally preceded by a prodromal phase in which there is a clear deterioration from a previous level of functioning,” p. 190), the emphasis was no longer on neurocognition or intellect as it had been in the DSM-III, and using the term deterioration was even discouraged (“The B criterion has been revised to take into account onset in childhood and to avoid the term ‘deterioration’, which suggests that recovery never occurs,” p. 419). As mentioned above, Kraepelin himself was aware that dementia praecox was an imperfect term given that some of his patients recovered fully.

DSM-IV: Continuity

The DSM-IV, published in 1994, retained the hegemonic position of the Schneiderian symptoms. Again, only one of these symptoms was required for diagnosis (“if delusions are bizarre or hallucinations consist of a voice keeping up a running commentary on the person’s behavior or thoughts, or two or more voices conversing with each other,” p. 312), but at least two other (unspecific) symptoms had to occur as well (delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior, or negative symptoms).

In the appendix of the DSM-IV, hallucinations (in general) were defined using virtually the same text as in the DSM-III and the DSM-III-R, with one notable exception: lack of insight (ie, “gross impairment in reality testing”) was no longer included in the core definition (in contrast to the DSM-III, as quoted above, which stated: “Strictly speaking, hallucinations indicate a psychotic disturbance only when they are associated with gross impairment in reality testing”). At the same time, the DSM-IV defined the term psychotic narrowly by restricting it to delusions or prominent hallucinations, with hallucinations occurring in the absence of insight into their pathological nature (p. 297). However, the DSM-IV’s more liberal definition did cover “hallucinations that the individual realizes are hallucinatory experiences” (p. 827), that is, hallucinations for which full insight is maintained.

In the spirit of this more liberal definition, lack of insight was no longer a defining criterion of a hallucination in the DSM-IV (“The person may or may not have insight into the nonveridical nature of the hallucination. One hallucinating person may recognize the false sensory experience, whereas another may be convinced that the experience is grounded in reality,” p. 822).

DSM-5: Break with Schneider

The latest edition of the DSM, the DSM-5, was published in 2013. William T. Carpenter chaired the chapter titled “Psychotic Disorders” with 11 authors.

The DSM-5 maintained the important role of positive symptoms (first described by Carpenter, Bartko, and Strauss6–8), particularly delusions and hallucinations, but eliminated the importance of (Schneiderian) bizarre delusions. The latter decision has sparked controversy because, according to some authors, first-rank symptoms may help to discriminate schizophrenia from organic psychotic states.12 Yet, Schneider’s ideas were not entirely abolished; the relative importance of auditory hallucinations was retained in the corresponding DSM-5 chapter although not in the criteria:

Hallucinations are perception-like experiences that occur without an external stimulus. They are vivid and clear, with the full force and impact of normal perceptions, and not under voluntary control. They may occur in any sensory modality, but auditory hallucinations are the most common in schizophrenia and related disorders. Auditory hallucinations are usually experienced as voices […]. (p. 87)

Of note, the DSM-5 still distinguishes between non-bizarre and (Schneiderian) bizarre delusions (p. 87).

The drastic reduction in Schneider’s influence in the DSM-5 is relatively unsurprising since Carpenter13 and others10,14 were convincing in their challenge to the specificity or pathognomonic nature of first-rank symptoms in people with schizophrenia (these symptoms have in fact also been reported in non-clinical participants12).

Of note, in Carpenter’s own study, first-rank symptoms were still far more prevalent in patients with schizophrenia (51%) than in those with the affective disorder (23%) and in those with what was then called “neuroses and characters disorders” (9%). In another study,7 the prevalence of single first-rank symptoms ranged from 10% (voices commenting on patients’ activity) to 29% (made volition) in patients with schizophrenia; one or more first-rank symptoms were reported by 58% of patients with schizophrenia, 22% of manic patients, 14% of depressive patients, and 4% of those with “neurotic and personality disorders.” Interestingly, when the presence of multiple first-rank symptoms was required, the specificity was relatively high (31% of patients with schizophrenia versus 3% of those without schizophrenia), but the authors concluded that “the system loses its general applicability” (p. 44). Symptoms may also manifest in the general population but are extremely rare,15 thus decreasing the risk of false-positive assignments. A Cochrane study16 showed that first-rank symptoms correctly identify schizophrenia in 75%–95% of cases, with approximately 5%–19% who have these symptoms misdiagnosed as having schizophrenia (the authors added that these misclassified participants may act “quite disturbed” and may still require some degree of assessment and help).

The DSM-5 broke not only with Schneider but also with Kraepelin’s typological concept:

Two changes were made to Criterion A for schizophrenia: 1) the elimination of the special attribution of bizarre delusions and Schneiderian first-rank auditory hallucinations (e.g., two or more voices conversing), leading to the requirement of at least two Criterion A symptoms for any diagnosis of schizophrenia, and 2) the addition of the requirement that at least one of the Criterion A symptoms must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech. The DSM-IV subtypes of schizophrenia were eliminated due to their limited diagnostic stability, low reliability, and poor validity. Instead, a dimensional approach to rating severity for the core symptoms of schizophrenia was included to capture the important heterogeneity in symptom type and severity expressed across individuals with psychotic disorders. (p. 810)

This review cannot fully cover the vast literature on the specificity of first-rank symptoms. Therefore, we refer interested readers to a summary by Nordgaard et al,10 published prior to the DSM-5, which was an early call for the de-emphasis on the diagnostic status of first-rank symptoms in light of many studies that, in the view of these authors, were heavily flawed (eg, symptoms not rated by clinicians, unclear definitions of first-rank symptoms).

Part 2. Hallucinations: The Role of Perception and Insight

Schneider’s View on Hallucinations: The Role of Insight

As discussed above, delusions and hallucinations have evolved as core criteria of schizophrenia over the different versions of the DSM. In the DSM-II, they were still considered secondary to formal thought disorder, in line with Bleuler.4 In this section, based on empirical evidence, we argue for a redefinition of hallucinations to de-emphasize the currently alleged proximity of hallucinations to real perceptions and to incorporate lack of insight (Insight is a complex, multidimensional construct that among other factors can relate to insight into a diagnosis or insight into the need for treatment.47 In the present context, insight refers to the degree to which the holder acknowledges a hallucination as being produced by their mind and not externally inflicted on them.) as an additional important dimension of schizophrenia. The appendix lists the search terms we used to find the studies we reviewed. For reasons of readability and space, we cite here only those studies we deem most relevant and representative of certain views, including studies that are partly at odds with our reasoning (eg, studies emphasizing the similarities between hallucinations and perceptions).

Our view that hallucinations differ from perceptions in many of their characteristics is largely in line with the ideas of Schneider, but it is essential to remember that his original ideas were based on clinical observations and not on independent empirical findings. Relevant empirical data are now available and, in our view, largely validate his ideas.

So, what did Schneider say about hallucinations? In Clinical Psychopathology,2 he refuted the idea that hallucinations are perceptions without a source. He wrote: “This generally depends on whether the hallucinations are distinctive and, as frequently happens, quite unlike any normal perceptions” (p. 46). The original sentence was in fact stronger. (“Das liegt übrigens auch daran, daß die Sinnestäuschungen an sinnlichem Gehalt sehr verschieden und oft nicht der normalen Wahrnehmung vergleichbar sind,” p. 47 [“This is also due to the fact that hallucinations are very different in sensory content and often not comparable to the normal perception.”].)

Concerning insight, Schneider2 made the following claim:

As well as unprejudiced investigation of the actual hallucinatory experience, it is important to get the patient’s attitude to it. When someone says his dead mother appeared at his bedside or he heard her call his name but adds, ‘I know it can’t really have been so,’ it is usually a case of so-called hypnagogic hallucination, which is not diagnostic for a psychosis but reveals the thoughts, fears, and wishes of the individual, who is imaginatively preoccupied. (p. 98)

In other words, for Schneider a hallucination did not have to have the “full force” of a true perception as required by the current version of the DSM. He argued that the holder of the hallucination should lack insight (at least at some point in time), a precondition that is no longer required by the DSM.

Before we consult the empirical literature relevant to these different views, we would like to point out that insight plays a key role in the assessment of a hallucination or hallucinatory behavior in the most prominent scales for the measurement of schizophrenia symptoms.17 In the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),18 the current gold standard for the assessment of symptoms in schizophrenia, the severity of the hallucinations reflects the degree of the individual’s delusional conviction or absence of insight as well as their preoccupation with and “acting on” the hallucinations. It says little, however, about sensory properties. For example, a rating of 5 (moderately severe) for hallucinations is defined as follows: “Hallucinations occur frequently, may involve more than one sensory modality, and tend to distort thinking and/or disrupt behaviour. Patient may have a delusional interpretation of these experiences and respond to them emotionally and, on occasion, verbally as well.” An extreme hallucination is defined as follows: “Patient is almost totally preoccupied with hallucinations, which virtually dominate thinking and behaviour. Hallucinations are provided a rigid delusional interpretation and provoke verbal and behavioural responses, including obedience to command hallucinations.”

The Signs and Symptoms of Psychotic Illness (SSPI)19 scale, another broadly used measure, likewise recommends higher severity ratings when illusions without insight or definite hallucinations influence observable behavior. The Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (PSYRATS; Haddock et al46) has two sections on hallucinations and delusions that allow for describing the phenomena based on multiple criteria, including insight, with different degrees of severity, implying that hallucinations are multidimensional and not a binary (on/off) phenomenon as indicated by the current definition in the DSM-5 (With respect to the criterion of insight, there is a rich clinical tradition of labeling hallucinatory experiences for which the holder has insight as pseudo-hallucinations; for problems with this term, see Refs. 48,49. This means that, irrespective of the severity of the sensory irritation, such cases would not be referred to as true hallucinations, which does not match the definition given in the DSM. Although it may be of heuristic value, we also view the term pseudo-hallucination problematic as insight is rarely an on/off phenomenon and often fluctuates across time).

Thoughts, Intrusions, and Hallucinations: Blurry Boundaries

In this section, we review empirical findings on hallucinations in schizophrenia. We consulted the relevant research and looked for studies that explored the phenomenology of hallucinations beyond severity. As we will show, these studies largely confirm both the views expressed by Schneider and contemporary scales for the assessment of hallucinations in schizophrenia in that they jointly consider perceptual properties, insight, and behavioral impact.

There is now much evidence against the claim that hallucinations should always be indistinguishable from real perceptions, as required by the DSM-5 (see also Parnas and colleagues20). According to the latest definition of hallucinations in the DSM, voice-hearing, the most prominent hallucination in schizophrenia, should be characterized by four features to meet the full DSM-5 definition. These were previously21 called the “4 A’s” (not to be confused with the 4 A’s put forward by Bleuler; see above): they must be acoustic and must feel alien (inserted from the outside), authentic (ie, real), and autonomous (ie, not under one’s own control). Yet, studies on voice-hearers show that very few patients, in fact, meet all of these criteria. In one of our studies,21 37% of voice-hearers with schizophrenia reported that their voices did not appear very real (ie, like true perceptions) and were quieter than external voices (52%). Voice-hearers in that study, irrespective of diagnostic status, reported greater vividness and volume of mental events per se, even for functional (“normal”) thoughts and obsessions, suggesting that enhanced mental vividness, presumably in addition to the presence of metacognitive biases (eg, externalization of negative events, jumping to conclusions, liberal acceptance)22 may represent vulnerability factors for the development of hallucinations.

In a study by Woods et al,23 less than half of the voice-hearers reported hearing literal auditory voices. Other studies have corroborated the view that hallucinations are often distinct from perceptions.24,25 According to Yttri and colleagues,26 many patients are in doubt whether their experiences merit being called voices or are merely thoughts; the authors conclude that auditory verbal hallucinations are “not an experience similar to a veridical perception, but something that is much more ephemeral and private“ (p. 663). In line with this research, another study reported that only a minority of voice-hearers (17.5%) experience their hallucinations as “literally auditory.”25

Yet, some studies have had different results in that the perceptual quality of the voices is sometimes almost as real and loud as true perceptions.24,27–29 In one of these phenomenological studies,24 most of the voice-hearers heard their voices at normal (35%) or loud (25%) volume (whispering softly: 31%). Moreover, 70% of voice-hearers reported that the sound of the voice was clear (46%) or sharp (24%). Importantly, while some voices seemed to be experienced as a real perception in terms of their physical properties, a large subgroup acknowledged that, unlike real voices, the hallucinated voices seemed like replays of memories or represented the patients’ own voice and thoughts.24 Moreover, a large subgroup of patients experienced the voices as internal as opposed to external perceptions.

A seemingly obvious solution that would accommodate a definition of hallucinations based on these findings would be to simply give up the notion that hallucinatory experiences are indistinguishable from externally derived sensory impressions. Yet, this raises the problem that perceptually charged cognitions are generally very prevalent and that perception-laden cognitions are thus not pathological per se. The human mind not only generates thoughts; it also produces images, both intentional and automatic/unconscious thoughts, as in dreams or catchy tunes. Inner speech is not necessarily silent, but many individuals report “hearing” something through their inner ear. In fact, 13.2% (median) of the general population acknowledge that they experience auditory hallucinations, such as voices from angels.30 A recent study on a large sample from the general population revealed that when asked about the previous month, 29.5% of the participants acknowledged having auditory hallucinations (voices, music, telephone, footsteps, etc.) and 21.5% visual hallucinations (shadows, people, movement, etc.); 27.4% of people experienced their smartphone ringing, and 89% experienced it vibrating when it actually was not.31,32

In psychiatric patients without schizophrenia, sensory irritations (ie, perceptuality-laden cognitions that are not held with full conviction and that share only some features with a perception) may be less severe than in those with schizophrenia but are actually very common as well. For example, approximately 3 out of 4 patients with OCD report that their intrusions have some sensory quality,33–35 and in depression this is affirmed by more than half of the sample.36,37 To conclude, sensory irritations are common, and we deem the label hallucinations for these phenomena inappropriate and overly pathologizing, especially as not all these phenomena affect behavior or evoke distress. As we outline in the next section, insight should once again play a role in defining a subtype of hallucinations.

Insight Into Hallucinations

Although the current version of the DSM is silent regarding the level of insight or conviction in hallucinations, as mentioned before, this has not always been the case (see the DSM-III-R).

In fact, one may argue that a delusional belief that is causally linked to a hallucination with full perceptual properties, as required by the DSM-5, may not even be a delusion proper in the sense of a false inference and thus may not qualify as a criterion for a diagnosis of schizophrenia. This would instead amount to something Maher38 called an “out of the ordinary” experience with a compelling sense of reality for which there is no immediately obvious explanation, thus giving rise to a supernatural explanation (for a discussion of Maher’s theory, see Ref. 22). We doubt, however, that an individual without schizophrenia would make similar inferences or act similarly upon the sensory experiences that schizophrenia patients describe (“Patients with disorders outside the psychotic spectrum ultimately acknowledge their aberrant experiences as a mere ‘as if’ feeling [ . . . ] due to their higher standards for evaluating hypotheses”).22 In fact, liberal acceptance may be a decisive factor in attributing sensory irritation to a supernatural cause21:

In schizophrenia patients, on the other hand, a limited set of voice-like characteristics may suffice to mistake self-generated cognitions as real voices (e.g., content does not resemble normal thinking) while ignoring others (e.g., no overt source […]). In other words, patients with schizophrenia—unlike OCD and healthy participants—use less stringent criteria to test the source hypothesis. Metacognitive beliefs about the controllability of thoughts […] in conjunction with some acoustic properties and, for example, a feeling of endangerment may be sufficient for a participant to attribute self-generated input to another agent. (21 p. 104)

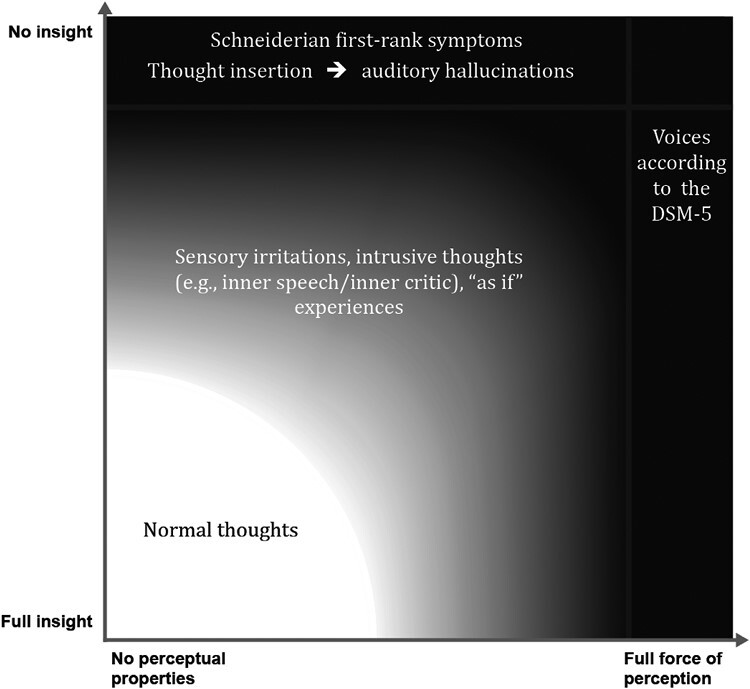

In figure 1, we have tried to reconcile the current definition of hallucinations (on the far right in the figure) with our view. Thoughts, intrusions (or “as if” attributions), and hallucinations can be described as dimensional phenomena along two axes: insight and perceptuality (ie, the degree to which an (internally generated) mental phenomenon has the full properties of a real perception). While benign or functional “normal” thoughts are characterized by the clear insight that they are one’s own thoughts (“mineness”) and by low perceptuality (see, however, our comment above that thoughts are not necessarily silent), intrusions show greater perceptuality and lower insight and/or higher preoccupation. Whereas the DSM-5 currently defines hallucinations only in terms of perception-likeness, we argue that an important additional defining feature is reduced insight (even lack of insight) into at least some perceptual properties. If perceptual properties are absent, other first-rank symptoms such as thought interference or thought withdrawal may be better labels, which is in line with the early writings of, for example, Jean Esquirol.20 We do not believe the current DSM-5 definition of hallucinations is wrong, but we are advocating for the inclusion of perceptual irritations for which individuals have built a delusional superstructure (ie, a comprehensive but false explanatory framework that the individual believes to be real) and whose falsity they lack insight into.

Fig. 1.

Normal thoughts, intrusions, and hallucinations as a function of insight and perceptuality (inspired by39).

Conclusion

This review outlines the varying criteria for schizophrenia across the five editions of the DSM, with a special focus on Schneider’s concept of first-rank symptoms.

For future editions of the DSM, we recommend that hallucinations should not be defined as “real perceptions without external source.” Instead, the current definition should be expanded to include internally generated phenomena that may differ in various ways from external perceptions, although a minor sensory component must still be present to distinguish them from first-rank symptoms such as “thought broadcasting” (this sensory component also may not simply usurp a true perception, as in illusions). In cases where only some criteria for a perception are met, insight must be low and influence on behavior high if the experience is to be called a hallucination (Parnas and colleagues20 recommend the term thought voices). Otherwise, prevalent phenomena such as daydreaming or an image of an “inner critic” that the individual knows is self-generated could also be labeled hallucinations, which would unduly pathologize such common experiences.

Irrespective of insight, any false or distorted perception should be called a sensory irritation, and it may or may not be pathological. In the language domain, we consider the term inner speech appropriate, as is visual imagery for visual phenomena.

For conditions (eg, neurological disorders) with severe sensory irritations that have the “full force” of a perception and may or may not have any delusional superstructure, the term hallucination should continue to apply because patients consider these phenomena to be real. These types of phenomena, however, are likely the exception in patients with schizophrenia.21,22 It may seem far-fetched to distinguish between schizophrenic and non-schizophrenic hallucinations, but this approach coincides with Schneider’s view: “There is no over-all [sic] personality change, without which we should hesitate to assess any hallucinatory experience as a symptom of psychosis, in any case certainly not as a symptom of schizophrenia” (p. 98).

In line with Bleuler,4 we also recommend that hallucinations in schizophrenia/psychosis should be regarded as imagery that is misidentified as a perception. Hallucinations must feel authentic, and there must be a sensory element. This results in two very different manifestations: hallucinations as described in the current definition of the DSM-5 (imagery that is indistinguishable from a perception, irrespective of insight) and sensory irritations that share only some properties of a perception but that the individual holds to be real. The aspects of low insight and/or high preoccupation (see also the response anchors of the rating scales described above), as well as rejection of ownership, seem necessary to identify the second type of hallucinations as pathological.

Future Directions: What if Carpenter and Schneider Are Both Right?

We have demonstrated how the DSM-I through DSM-5 have incorporated the theories and views of Kraepelin, Bleuler, and Schneider as well as the ideas of the pioneers of the positive-negative syndrome concept, which emerged in the 1970s.5–8,40 While we outline solid arguments for the need to redefine hallucinations in schizophrenia, we are less certain about the best fate for first-rank symptoms. We agree with Carpenter11,13 and others10,14 that these are perhaps less specific to schizophrenia than initially thought.41 Yet, even in the decisive study by Carpenter and colleagues, first-rank symptoms were far more common in schizophrenia than in affective and “neurotic” disorders, possibly arguing for weighting them more heavily in diagnosing schizophrenia.12,16,42 This, however, can only be determined empirically and through a consensus among experts. We encourage a study that might help to improve the discriminatory power of first-rank symptoms by asking individuals with and without schizophrenia about the real-life impact of first-rank symptoms as it makes a large difference whether an individual feels “as if”43 they have permeable ego boundaries (which is common in the general population and a key claim of many benign religious beliefs44,45) or whether the person is convinced of it. Thus, combining the content of the sensory irritation with the level of conviction may help to reduce the number of false-positive diagnoses of schizophrenia. It is necessary to examine whether patients with first-rank symptoms differ significantly from patients without these symptoms. First-rank symptoms likely deserve special treatment, irrespective of the overarching diagnosis (schizophrenia or other). Thus, research on this unique psychopathological phenomenon should continue.46

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Steffen Moritz, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Łukasz Gawęda, Experimental Psychopathology Lab, Institute of Psychology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland.

William T Carpenter, Department of Psychiatry, Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Adrianna Aleksandrowicz, Experimental Psychopathology Lab, Institute of Psychology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland.

Lisa Borgmann, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Jürgen Gallinat, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Thomas Fuchs, Department of General Psychiatry, Center for Psychosocial Medicine, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Schneider K. Psychischer Befund und psychiatrische Diagnose [Psychiatric Assessment and Psychiatric Diagnosis]. Leipzig, Germany: Thieme; 1939. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schneider K. Clinical Psychopathology. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie. Ein Lehrbuch für Studierende und Ärzte [Psychiatry. A Textbook for Students and Physicians]. 8th ed. Leipzig, Germany: Barth; 1913. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bleuler E. Dementia Preacox or the Group of Schizophrenias. Published in 1911. (Aschaffenburg G, ed.). Leipzig: Deuticke; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andreasen NC, Olsen S.. Negative v positive schizophrenia. Definition and validation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(7):789–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bartko JJ, Strauss JS, Carpenter WT.. The diagnosis and understanding of schizophrenia. Part II. Expanded perspectives for describing and comparing schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1974;1(11):50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carpenter WT, Strauss JS, Bartko JJ.. The diagnosis and understanding of schizophrenia. Part I. Use of signs and symptoms for the identification of schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1974;1(11):37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT, Bartko JJ.. The diagnosis and understanding of schizophrenia. Part III. Speculations on the processes that underlie schizophrenic symptoms and signs. Schizophr Bull. 1974;1(11):61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kety SS. The syndrome of schizophrenia: unresolved questions and opportunities for research. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136(5):421–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nordgaard J, Arnfred SM, Handest P, Parnas J.. The diagnostic status of first-rank symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(1):137–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Muleh S, Carpenter WT.. Book review of clinical psychopathology (Kurt Schneider). Compr Psychiatry. 1974;15(3):255–256. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heinz A, Voss M, Lawrie SM, et al. Shall we really say goodbye to first rank symptoms? Eur Psychiatry. 2016;37:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carpenter WT, Strauss JS, Muleh S.. Are there pathognomonic symptoms in schizophrenia? An empiric investigation of Schneider’s first-rank symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;28(6):847–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oliva F, Dalmotto M, Pirfo E, Furlan PM, Picci RL.. A comparison of thought and perception disorders in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia: psychotic experiences as a reaction to impaired social functioning. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):239. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0239-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Psychotic experiences in the general population: a cross-national analysis based on 31 261 respondents from 18 countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soares-Weiser K, Maayan N, Bergman H, et al. First rank symptoms for schizophrenia (Cochrane diagnostic test accuracy review). Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(4):792–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robins AH. Pitfalls in questioning patients about auditory hallucinations. S Afr Med J. 1973;47(48):2349–2350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA.. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liddle PF, Ngan ETC, Duffield G, Kho K, Warren AJ.. Signs and symptoms of psychotic illness (SSPI): a rating scale. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180(1):45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Parnas J, Yttri JE, Urfer-Parnas A.. Phenomenology of auditory verbal hallucination in schizophrenia: an erroneous perception or something else? Schizophr Res. 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2023.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moritz S, Larøi F.. Differences and similarities in the sensory and cognitive signatures of voice-hearing, intrusions and thoughts. Schizophr Res. 2008;102(1–3):96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moritz S, Pfuhl G, Lüdtke T, Menon M, Balzan RP, Andreou C.. A two-stage cognitive theory of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Highlighting the role of lowered decision thresholds. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2017;56:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Woods A, Jones N, Alderson-Day B, Callard F, Fernyhough C.. Experiences of hearing voices: analysis of a novel phenomenological survey. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(4):323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCarthy-Jones S, Trauer T, Mackinnon A, Sims E, Thomas N, Copolov DL.. A new phenomenological survey of auditory hallucinations: evidence for subtypes and implications for theory and practice. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(1):231–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones N, Luhrmann TM.. Beyond the sensory: findings from an in-depth analysis of the phenomenology of “auditory hallucinations” in schizophrenia. Psychosis. 2016;8(3):191–202. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yttri JE, Urfer-Parnas A, Parnas J.. Auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia, part II: phenomenological qualities and evolution. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2022;210(9):659–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nayani TH, David AS.. The auditory hallucination: a phenomenological survey. Psychol Med. 1996;26(1):177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Upthegrove R, Ives J, Broome MR, Caldwell K, Wood SJ, Oyebode F.. Auditory verbal hallucinations in first-episode psychosis: a phenomenological investigation. BJPsych Open. 2016;2(1):88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Toh WL, Thomas N, Hollander Y, Rossell SL.. On the phenomenology of auditory verbal hallucinations in affective and non-affective psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113147. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beavan V, Read J, Cartwright C.. The prevalence of voice-hearers in the general population: a literature review. J Ment Health. 2011;20(3):281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pisano S, Masi G, Catone G, et al. Phantom phone signal: why it should be of interest for psychiatry. Riv Psichiatr. 2021;56(3):138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deb A. Phantom vibration and phantom ringing among mobile phone users: a systematic review of literature. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2015;7(3):231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moritz S, Claussen M, Hauschildt M, Kellner M.. Perceptual properties of obsessive thoughts are associated with low insight in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(7):562–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moritz S, Purdon C, Jelinek L, Chiang B, Hauschildt M.. If it is absurd, then why do you do it? The richer the obsessional experience, the more compelling the compulsion. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2018;25(2):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Röhlinger J, Wulf F, Fieker M, Moritz S.. Sensory properties of obsessive thoughts in OCD and the relationship to psychopathology. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(2):592–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moritz S, Hörmann CC, Schröder J, et al. Beyond words: sensory properties of depressive thoughts. Cogn Emot. 2014;28(6):1047–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moritz S, Klein JP, Berger T, Larøi F, Meyer B.. The voice of depression: prevalence and stability across time of perception-laden intrusive thoughts in depression. Cognit Ther Res. 2019;43(6):986–994. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maher BA. The relationship between delusions and hallucinations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(3):179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fuchs T. Halluzinationen bei endogenen Psychosen. In: Möller HJ, Przuntek H, Laux G, Büttner T, eds. Therapie Im Grenzgebiet von Neurologie und Psychiatrie. Band 2. Berlin (Germany): Springer; 1996:59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Crow TJ. The two-syndrome concept: origins and current status. Schizophr Bull. 1985;11(3):471–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ross CA, Joshi S.. Schneiderian symptoms and childhood trauma in the general population. Compr Psychiatry. 1992;33(4):269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rosen C, Grossman LS, Harrow M, Bonner-Jackson A, Faull R.. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of Schneiderian first-rank symptoms: a 20-year longitudinal study of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(2):126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klosterkötter J. The meaning of basic symptoms for the genesis of the schizophrenic nuclear syndrome. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1992;46(3):609–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Branković M. Who believes in ESP: cognitive and motivational determinants of the belief in extra-sensory perception. Eur J Psychol. 2019;15(1):120–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rice TW. Believe it or not: religious and other paranormal beliefs in the United States. J Sci Study Relig. 2003;42(1):95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Haddock G, McCarron J, Tarrier N, Faragher EB.. Scales to measure dimensions of hallucinations and delusions: the psychotic symptom rating scales (PSYRATS). Psychol Med. 1999;29(4):879–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Belvederi Murri M, Amore M.. The multiple dimensions of insight in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(2):277–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gras A, Amad A, Thomas P, Jardri R.. Hallucinations and borderline personality disorder: a review [Hallucinations et trouble de personnalité borderline: une revue de littérature]. Encephale. 2014;40(6):431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Taylor FK. On pseudo-hallucinations. Psychol Med. 1981;11(2):265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.