Abstract

Bone remodeling is a highly coordinated process responsible for bone resorption and formation. It is initiated and modulated by a number of factors including inflammation, changes in hormonal levels and lack of mechanical stimulation. Bone remodeling involves the removal of mineralized bone by osteoclasts followed by the formation of bone matrix through osteoblasts that subsequently becomes mineralized. In addition to the traditional bone cells (osteoclasts, osteoblasts and osteocytes) that are necessary for bone remodeling, several immune cells such as polymorphonuclear neutrophils, B cells and T cells have also been implicated in bone remodelling. Through the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB/receptor activator of the NF-κB ligand/osteoprotegerin system the process of bone resorption is initiated and subsequent formation is tightly coupled. Mediators such as prostaglandins, interleukins, chemokines, leukotrienes, growth factors, wnt signalling and bone morphogenetic proteins are involved in the regulation of bone remodeling. We discuss here cells and mediators involved in the cellular and molecular machanisms of bone resorption and bone formation.

Cell Types Involved in Bone Remodeling

Bone remodeling is a lifelong process where old bone is removed (resorption) and new bone is created (formation) [1, 2]. This process is regulated by different cell types that form bone (osteoblasts), regulate bone homeostasis (osteocytes), resorb bone (osteoclasts) and affect bone resorption and formation (innate and adaptive immune cells). There are several pathologic processes that can affect bone remodeling whereby both bone resorption and formation are affected and have been demonstrated in post-menopausal osteoporosis, arthritis, periodontal disease and micro-gravity or disuse [2].

Osteoclasts are terminally differentiated myeloid cells that are uniquely adapted to remove mineralized bone matrix [1]. They are found in pits within the bone surface which are called resorption bays, also known as Howship’s Lacunae. Osteoclasts resorb bone by producing acid that dissolves the mineral content and enzymes that remove the organic matrix. Mature osteoclasts anchor to the bone through RGD-binding sites to create a sealed microenvironment.

Osteoblasts are bone-forming cells that arise from osteoprogenitor cells. RUNX2 (runt-related transcription factor 2) and other transcription factors control the differentiation of osteoblasts [2–4]. During bone formation, a subpopulation of osteoblasts undergoes terminal differentiation and becomes engulfed by osteoid, at which time they are referred to as osteoid osteocytes. Osteocytes which reside in lacunae are the most numerous cell type found in mature bone and are long-lived. They have dendritic processes that interact with other osteocytes and bone-lining cells on the bone surface. Osteocytes respond to mechanical load. Under resting conditions osteocytes express sclerostin, which directly prevents Wnt signaling (described in more detail below). Sclerostin expression can be inhibited by parathyroid hormone signaling to remove this inhibitor of Wnt signaling and allow Wnt directed bone formation to occur. Under basal conditions, osteocytes secrete transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), which inhibits osteoclastogenesis. However, upon stimulation osteoblasts and osteocytes produce osteoclastogenic factors such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) and receptor activator of the NF-κB ligand (RANKL) to induce bone remodeling [1–4].

Innate immune cells (primarily polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNS), monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells) and adaptive immune cells (primarily lymphocytes) modulate bone resorption particularly under inflammatory conditions. PMNs are granular leukocytes that predominate in the initial acute inflammatory response. Like other leukocytes, they are recruited from the peripheral vasculature by chemotactic factors, particularly chemokines. They express a number of inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) as well as membrane-bound RANKL [4]. Macrophages are produced from the differentiation of monocytes in tissue. Monocytes/macrophages can have an inflammatory or a pro-vascularization phenotype called M1 or M2. M1 macrophages produce cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α and RANKL, whereas M2 monocytes/macrophages produce anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10 and IL-4 [5]. Dendritic immune cells have their origin in bone marrow and are found in a number of different tissues. One of the first contacts between oral bacteria and the immune system occurs with Langerhans cells, a subset of dendritic cells found in mucosal surfaces and skin. They function in activating the immune response as antigen presenting cells and regulate homeostasis by modulating the response to oral bacteria and self-antigens. Once they detect antigen dendritic cells travel to lymph nodes and present antigen to activate lymphocytes.

The predominant cells of the adaptive immune response are B and T lymphocytes. Activated T and B cells can express RANKL and various other cytokines that typically promote osteoclastogenesis. B cells express TNF-α, IL-6, and RANKL to promote osteoclastogenesis. T cells can develop into T-helper cells, Th1, Th2 and Th17 that modulate bone resorption. Th1-type produce IL-1 and TNF-α that can promote bone resorption. Th17 cells have recently been identified as an effector T helper cell subset characterized by the production of proinflammatory cytokines. IL-1 and IL-17 mediate osteoclast formation through induction of RANKL [6]. Lymphocyte subsets (Th2) produce cytokines that are anti-inflammatory, IL-4 and IL-10. These cytokines reduce osteoclastogenesis and the severity of bone loss [7].

Mediators Involved in Bone Resorption

Mediators play an important role in the pathogenesis of bone damage. Cytokines stimulate the recruitment, formation and activity of the bone-resorbing cell, the osteoclast. They trigger the chemotaxis of osteoclast precursors, the induction of genes that lead to fusion of these precursors, the maturation of osteoclasts and the synthesis of matrix enzymes leading to bone resorption. Understanding these steps has led to the development of therapeutic agents that can block these osteoclastogenesis and activity reducing bone loss [8].

RANKL and CSF-1 work cooperatively and represent one of the dominant pathways that leads to osteoclast formation and activity [9]. CSF-1 is crucial for the proliferation and survival of osteoclast precursor cells, while RANKL is essential for osteoclast differentiation [9]. RANKL, also called tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 11 is a cytokine that belongs to the TNF family. RANKL is expressed on the surface of marrow stromal cells, monocytes, activated T and B cells, osteocytes and precursors of bone forming osteoblasts. RANKL may be cleaved and released in a soluble form by metalloproteinases. It should be noted that the cell type that expresses RANKL may depend upon the etiology of the bone resorption. For example, the cells that produce RANKL differ between bone resorption caused by post-menopausal osteoporosis versus resorption associated with periodontal disease. During physiologic bone resorption, these factors act on osteoblasts/osteocytes to regulate RANKL and osteoprotegerin (OPG) expression.

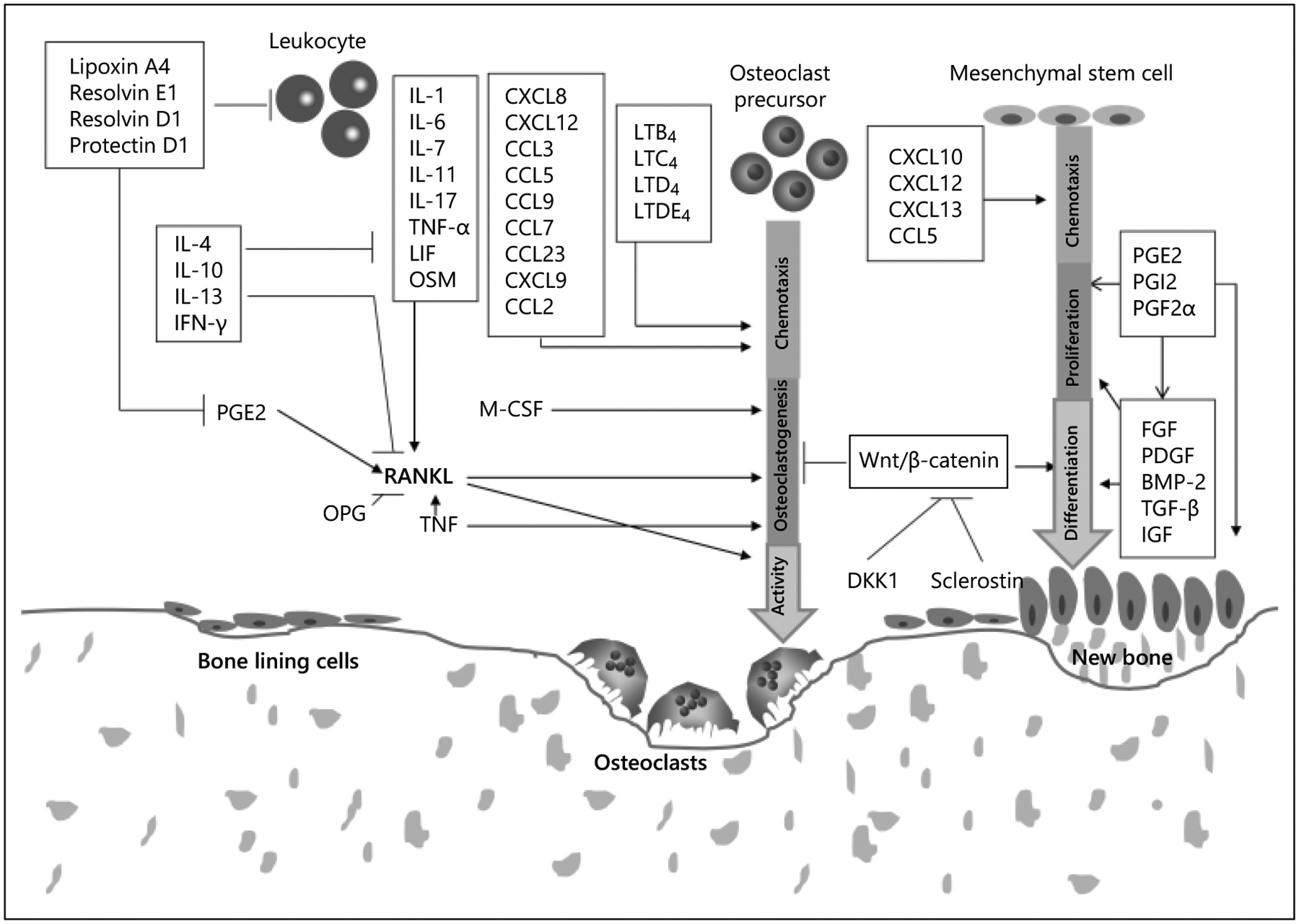

CSF-1 also known as macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) is a glycoprotein growth factor that specifically regulates the survival, proliferation and differentiation of monocyte-macrophage lineage cells through a cell surface receptor selectively expressed on these cell types, c-fms. M-CSF is released by osteoblasts and bone marrow progenitor cells that upon binding to its receptor, c-fms on pre-osteoclasts, activates an intracellular cascade that leads to proliferation of precursors and survival of osteoclasts. RANKL stimulates osteoclastogenesis when it binds to receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK), which is located on osteoclast precursors to activate NF-κB and other signaling pathways. This binding promotes osteoclast formation, activation, and survival, thus inducing osteoclast activity and bone resorption (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Stimulation of osteoclastogenesis, bone resorption, and coupled bone formation. RANKL, M-CSF, and TNF directly stimulate the formation of osteoclasts, while other cytokines or lipid-based mediators such as prostaglandins or leukotrienes indirectly stimulate osteoclastogenesis by effects on RANKL, M-CSF, or TNF-α. Chemokines affect resorption by stimulation recruitment of osteoclast precursors or osteoclast activity. Chemokines such as CXCL10, CXCL12, CXCL13, and CCL5, may affect bone formation by effects on osteoblast precursors or osteoblasts. Wnt signaling, growth factors such as FGF, PDGF, BMP-2, TGF-β, and IGF play an important role in osteogenesis by stimulating proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells/osteoblast precursors and inducing osteoblast differentiation or synthesis of bone matrix. Modified with permission from Graves et al. [30].

OPG, also called tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 11B (TNFRSF11B) is a soluble cytokine receptor that belongs to the TNF family [10]. It is produced by osteoblasts, fibroblasts and many other cell types. OPG binds to RANKL preventing RANKL from binding to its cognate receptor, RANK. Thus, OPG is a natural decoy receptor (inhibitor) of RANKL [11]. The RANKL/OPG expression ratio to a large degree determines the degree of osteoclast formation and activity [4].

A number of pro-inflammatory cytokines stimulate bone resorption [4] (fig. 1). Most accomplish this by stimulating production of RANKL. Some, such as TNF-α can induce RANKL but also stimulate osteoclast formation directly, independently of RANKL (fig. 1). TNF-α is produced primarily by activated macrophages, but also by other cell types such as activated T cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, epithelial cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts and bone-lining cells including osteoblasts. TNF-α upregulates c-fms (CSF-1 receptor) expression and activates osteoclasts by enhancing RANKL signaling mechanisms. TNF-α induces osteoclast precursors and marrow stromal cells to produce osteoclastogenic cytokines, such as IL-1, RANKL, and M-CSF. TNF also inhibits the bone-forming function of osteoblasts. Studies show that TNF-α inhibits the differentiation of new osteoblasts from precursor cells. The regulation of RUNX2 by TNF could diminish recruitment of osteoblast precursors into the pool of mature bone-forming cells [12].

IL-1, which is encoded by two separate genes, IL-1α and IL-1β, is a potent bone resorbing cytokine produced by various cell types such as monocytes, macrophages, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, fibroblasts (gingival and periodontal ligament), epithelial cells, endothelial cells and osteoblasts. Both isoforms of IL-1 stimulate production of other cytokines and prostaglandins and can induce RANKL expression as well as production of degradative enzymes. However, it does not directly induce osteoclastogenesis [13]. IL-6 is produced by many of the same cell types that produce IL-1. IL-6 has been reported to stimulate bone resorption by enhancing osteoclast formation through a RANKL-dependent mechanism [14]. IL-7 is an osteoclastogenic cytokine mainly produced by stromal cells and osteoblasts that promotes RANKL expression. It also inhibits new bone formation by down regulation of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor Runx2. IL-17 is produced by activated CD4+ Th17 cells and stimulates cells to express receptor activator of RANKL. IL-17 also reduces bone formation via inhibition of type I collagen synthesis [15]. Other osteoclastogenic cytokines that have been shown to stimulate activation of RANKL are IL-11, leukemia inhibitory factor, and oncostatin M (fig. 1).

Chemokines are chemotactic cytokines that stimulate recruitment of leukocytes and are produced by a wide variety of cell types including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and many different leukocyte subsets of the innate and adaptive immune response, fibroblasts or bone lining cells [4]. Some chemokines recruit osteoclast precursors (fig. 1). CCL2 (also known as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, MCP-1) induces recruitment of osteoclast precursors. Other chemokines that have been shown to stimulate recruitment of osteoclast precursors are CCL5, CXCL8, CCL9, CCL7, CCL23, CXCL12, and CXCL9 [4, 16, 17]. CCL3 (also called MIP-1α), a pro-inflammatory chemokine produced at inflammatory sites, appears to play a crucial role in pathologic osteoclastogenesis associated with multiple myelomas. It modulates osteoclast differentiation by binding to G-protein coupled receptors, CCR1 and CCR5, and activating ERK and AKT signaling pathways. The MIP-1β (CCL4) also can enhance bone resorption [16, 17].

Prostaglandins and leukotrienes are lipid-based mediators derived from fatty acids that are produced by different cell types such as macrophages, fibroblasts and gingival epithelial cells (fig. 1) [18]. Prostaglandin E (PGEs), such as prostaglandin E2, prostacyclin and prostaglandin F2α stimulate osteoclast formation through RANKL and direct effect on osteoclast formation, also stimulate bone formation. Prostaglandin E2 has been linked to stimulating insulin growth factor-1 gene expression, which promotes collagen synthesis by osteoblasts, thus enhancing bone formation [19]. Leukotrienes are another class of inflammatory lipid mediators and stimulate chemotaxis of leukocytes and the generation of superoxides in neutrophils. Leukotrienes such as LTB4, LTC4, LTD4 and LTDE4 enhance osteoclast formation and activation of mature osteoclasts by a RANKL independent mechanism. LTB4 may suppress bone formation by inhibiting the proliferation of primary osteoblast precursors and reduce the capacity of osteoblast precursors to differentiate into osteoblasts and form new bone [20]. Lipoxins and the D and E series of resolvins are endogenous anti-inflammatory lipid mediators that act by controlling the resolution of the inflammation through enhancing apoptosis of PMNs and their clearance by macrophages, blocking leukotrienes and prostaglandins as well as reducing cytokine release [21]. For example, resolvin E1 is produced during the resolution of the inflammation and blocks stimulation by leukotriene B4. This inhibition attenuates neutrophil migration leading thereby reducing inflammation. Lipoxin acts by binding to lipoxin A4 receptor inhibiting chemotaxis, transmigration and blocking activation of nuclear factor kappa-B.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are proteases produced by different cell types such as macrophages and fibroblasts [22]. Inflammatory mediators induce production of MMP from a number of cell types such as fibroblasts and PMNs. These molecules degrade extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen, elastin, and laminins. Osteoclasts secrete MMP contributing to degradation of bone matrix following decalcification by acid production. Furthermore, MMPs can activate chemokines and cytokines to amplify inflammation [23]. For example, MMPs activate chemokines by cleavage of the N-terminal domain.

Mediators That Stimulate Bone Formation

Wnt signaling, growth factors and bone morphogenetic proteins play an important role in osteogenesis [24, 27, 28] (fig. 1). The Wnt signaling transduction pathway plays an important role in stimulating bone formation and in many other processes including embryonic development and tumorigenesis [24]. Wnts are secreted, cysteine-rich glycoproteins involved in controlling cell proliferation, cell-fate specification, gene expression, and cell survival. Wnt-3a and Wnt-7a are expressed in the limb bud and have roles in skeletal pattern determination, while Wnt-14 is involved in joint formation. And Wnt-3a, Wnt-4, Wnt-5a, and Wnt-7a all influence cartilage development. Wnt receptors are including low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins (LRP) and frizzleds (Fzd). LRP are evolutionarily conserved plasma membrane receptors with a variety of functions including lipid metabolism, cargo transport, and cellular signaling. LRP-5 is expressed by osteoblasts of the endosteal and trabecular bone surface. It regulates osteoblastic proliferation, survival and activity. Fzds are highly versatile seven-membrane proteins that contribute to activation of both β-catenin and non-β-catenin signaling pathways by virtue of their interactions with Dishevelled (Dsh, or Dvl), a cytoplasmic phosphoprotein that acts directly downstream of frizzled receptors. The Wnt pathway has been found to play a central role in controlling embryonic bone development and bone mass. There are four Wnt pathways: the canonical Wnt pathway (the Wnt/b-catenin pathway) and three non-canonical Wnt (β-catenin independent) pathways: the Wnt/Ca2þ pathway, the Wnt/planar cell polarity (Wnt/PCP) pathway, and the Wnt/protein kinase A (Wnt/PKA) pathway. Beta-catenin, a key component of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway interacts with a number of different transcription factors and modulates their activity. This leads to the transcription of a number of different target genes that regulate a diverse array of biological processes. In the osteocyte Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is required for normal bone homeostasis [24]. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway is anabolic for bone formation and promotes increased bone density and strength. Beta-catenin activation facilitates osteoblast differentiation and enhances osteoblast and osteocyte survival in vitro. The Wnt pathway can also affect osteoclastogenesis. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway suppresses physiologic bone resorption by upregulation of OPG expression and downregulation of RANKL in osteoblasts/osteocytes [25].

The Wnt pathway is inhibited by Dickkopf factors 1–4 (DKK1, DKK2, DKK3, DKK4) and sclerostin. Dkk1 is expressed by synovial cells, endothelial cells and chondrocytes. Dickkopf factors, especially DKK1, bind and sequester the LRP5/6 and Kremen1/2 (Krm1/2), the Wnt pathway receptors membrane complex to inhibit Wnt activity. Sclerostin, the protein product of the Sost gene is also a Wnt inhibitor. It is produced by osteocytes and is abundant in osteocytic canaliculae. Sclerostin binds to Lrp5/6 to block the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway and inhibit proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts and to increase their apoptosis [25].

Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2 also known as basic FGF) is involved in numerous cellular processes including angiogenesis, tumorigenesis, cell proliferation, differentiation, wound healing, limb formation, and bone biology. In bone, FGF-2 is expressed in osteoblasts and mesenchymal cells. Postnatally, FGF-2 is produced by mature osteoblasts and stored in extracellular matrix. FGF-2 along with FGF-18 is a bone anabolic agent that stimulates uncommitted bone marrow stromal cells to differentiate into osteoblasts and form osteoid. Thus it plays an important role in skeletal development by regulating the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts [26]. FGF-2 signaling regulates the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway and activates transcription factors Runx2 and activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), thereby promoting osteoblast differentiation [27].

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are a group of protein factors that stimulate bone formation and are important in a number of other biologic factors such as skin formation and hair follicle development [28] (fig. 1). BMPs released by osteoclasts and from resorbing bone matrix interact with specific receptors on the cell surface, referred to as bone morphogenetic protein receptors (BMPRs). There are type I and type II BMPRs. Two subclasses of type I receptors have been identified, type IA and IB (BMPR1A and BMPR1B). Upon ligand binding, the type II receptor forms a heterodimer with the type I receptor, and the constitutive kinase of the type II activates the type I receptor. The latter initiates a signal transduction cascade by phosphorylating downstream cytosolic factors, which then translocate to the nucleus to activate or inhibit transcription. Signaling by BMPs plays an important role in variety of cell types in bone such as osteoblasts and chondrocytes. BMPs have widely recognized roles in bone formation such as BMP-2, BMP-4, BMP-5, BMP-6 and BMP-7 which have an osteogenic capacity. BMPs stimulate intracellular signaling by activating the mothers against decapentaplegic (Smad) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways. Following BMP induction, both the Smad and MAPK pathways converge at the Runx2 gene to control its activation. The subsequent signaling induced by BMP (ligand, receptors, intracellular mediators, activation of transcription factors or comodulators) is responsible for the final target gene expression. BMP signaling may also be required for expression of RANKL in osteoblasts/osteocytes [28]. BMP signaling can be inhibited or modified in many ways, including inhibition through chordin and noggin. These antagonists are regulated by BMPs, indicating the existence of local feedback mechanisms to modulate BMP cellular activities. For example, noggin binds with various degrees of affinity to BMP-2, BMP-4, BMP-5, BMP-6 and BMP-7. Crystallography of noggin and BMP-7 reveals that noggin inhibits BMP-7 signaling by blocking the molecular interfaces of the binding epitopes for both type I and type II BMP receptors. Basal noggin expression in osteoblasts is limited but its transcript levels are up-regulated by BMP-2, BMP-4 and BMP-6 as a potential protective mechanism limiting excessive BMP stimulation [29].

References

- 1.Schett G, Teitelbaum SL: Osteoclasts and arthritis. J Bone Miner Res 2009; 24: 1142–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiao H, Xiao E, Graves DT: Diabetes and its effect on bone and fracture healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2015; 13: 327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karsenty G: Transcriptional control of skeletogenesis. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2008; 9: 183–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graves DT, Oates T, Garlet GP: Review of osteoimmunology and the host response in endodontic and periodontal lesions. J Oral Microbiol 2011; 3: 10.3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benoit M, Desnues B, Mege JL: Macrophage polarization in bacterial infections. J Immunol 2008; 181: 3733–3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato K, Suematsu A, Okamoto K, et al. : Th17 functions as an osteoclastogenic helper T cell subset that links T cell activation and bone destruction. J Exp Med 2006; 203: 2673–2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinarello CA: Historical insights into cytokines. Eur J Immunol 2007; 37(suppl 1):S34–S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schett G: Effects of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines on the bone. Eur J Clin Invest 2011; 41: 1361–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takayanagi H: Osteoimmunology: shared mechanisms and crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. Nat Rev Immunol 2007; 7: 292–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belibasakis GN, Bostanci N: The RANKL-OPG system in clinical periodontology. J Clin Periodontol 2012; 39: 239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, et al. : Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell 1997; 89: 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karmakar S, Kay J, Gravallese EM: Bone damage in rheumatoid arthritis: mechanistic insights and approaches to prevention. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2010; 36: 385–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagai H, Tsukuda R, Mayahara H: Effects of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) on bone formation in growing rats. Bone 1995; 16: 367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmqvist P, Persson E, Conaway HH, Lerner UH: IL-6, leukemia inhibitory factor, and oncostatin M stimulate bone resorption and regulate the expression of receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand, osteoprotegerin, and receptor activator of NF-kappa B in mouse calvariae. J Immunol 2002; 169: 3353–3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daoussis D, Andonopoulos AP, Liossis SN: Wnt pathway and IL-17:novel regulators of joint remodeling in rheumatic diseases. Looking beyond the RANK-RANKL-OPG axis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 39: 369–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szekanecz Z, Koch AE, Tak PP: Chemokine and chemokine receptor blockade in arthritis, a prototype of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Neth J Med 2011; 69: 356–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szekanecz Z, Vegvari A, Szabo Z, Koch AE: Chemokines and chemokine receptors in arthritis. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2010; 2: 153–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bage T, Kats A, Lopez BS, et al. : Expression of prostaglandin E synthases in periodontitis immunolocalization and cellular regulation. Am J Pathol 2011; 178: 1676–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minamizaki T, Yoshiko Y, Kozai K, Aubin JE, Maeda N: EP2 and EP4 receptors differentially mediate MAPK pathways underlying anabolic actions of prostaglandin E2 on bone formation in rat calvaria cell cultures. Bone 2009; 44: 1177–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang J, Lv HS, Lin JH, Jiang DF, Chen ZK: LTB4 can directly stimulate human osteoclast formation from PBMC independent of RANKL. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol 2005; 33: 391–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE: Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8: 349–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manicone AM, McGuire JK: Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2008; 19: 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannobile WV: Host-response therapeutics for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol 2008; 79: 1592–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Alman BA: Wnt pathway, an essential role in bone regeneration. J Cell Biochem 2009; 106: 353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi N, Maeda K, Ishihara A, Uehara S, Kobayashi Y: Regulatory mechanism of osteoclastogenesis by RANKL and Wnt signals. Front Biosci 2011; 16: 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downey ME, Holliday LS, Aguirre JI, Wronski TJ: In vitro and in vivo evidence for stimulation of bone resorption by an EP4 receptor agonist and basic fibroblast growth factor: Implications for their efficacy as bone anabolic agents. Bone 2009; 44: 266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ai-Aql ZS, Alagl AS, Graves DT, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA: Molecular mechanisms controlling bone formation during fracture healing and distraction osteogenesis. J Dent Res 2008; 87: 107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen G, Deng C, Li YP: TGF-beta and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Int J Biol Sci 2012; 8: 272–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krause C, Guzman A, Knaus P: Noggin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2011; 43: 478–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graves DT, Li J, Cochran DL: Inflammation and uncoupling as mechanisms of periodontal bone loss. J Dent Res 2011; 90: 143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]