Abstract

Modern retrosynthetic analysis in organic chemistry is based on the principle of polar relationships between functional groups to guide the design of synthetic routes.1 This method, termed polar retrosynthetic analysis, assigns partial positive (electrophilic) or negative (nucleophilic) charges to constituent functional groups in a complex molecules followed by disconnecting bonds between opposing charges.2–4 While this approach forms the basis of undergraduate curriculum in organic chemistry5 and strategic applications of most synthetic methods,6 their implementation often requires a long list of ancillary considerations to mitigate chemoselectivity and oxidation state issues involving protecting groups and precise reaction choreography.3,4,7 Here we report a radical-based Ni/Ag-electrocatalytic cross coupling of a-substituted carboxylic acids thereby enabling an intuitive and modular approach to accessing complex molecular architectures. This new method relies on a key silver additive that forms an active Ag-nanoparticle coated electrode surface8,9 in situ along with carefully chosen ligands that modulate the reactivity of Ni. Through judicious choice of conditions and ligands, the cross-couplings can be rendered highly diastereoselective. To demonstrate the simplifying power of these reactions, concise syntheses of 14 natural products and two medicinally relevant molecules were completed.

Polyfunctionalized carbon frameworks containing 1,2-, 1,3-heteroatom-substituted fragments are ubiquitous in organic molecules. Construction of such motifs has been the central theme of organic synthesis throughout its history. Numerous methods have been developed to access such motifs, and the strategic usage of such reactions has historically been guided by polar retrosynthetic analysis (2e− disconnections).1–4 These classic methods can be broadly categorized into the functionalization of olefins and carbonyl compounds (Figure 1A). In the case of olefins, for example, Sharpless epoxidation/dihydroxylation/aminohydroxylation and related reactions can allow straightforward access to precursors that can then be converted to the desired target after further functionalization. The rich chemistry of carbonyl compounds encompasses a myriad of transformations ranging from the installation of heteroatoms in the adjacent position (e.g. Rubottom oxidation or asymmetric enamine chemistry) or classic C–C bond forming events such as aldol, Claisen condensation, pinacol coupling and Mannich reaction.6 The electrophilicity of carbonyl compounds allows for a combination with orthogonal olefin chemistry such as in the case of carbonyl allylation followed by oxidative cleavage.

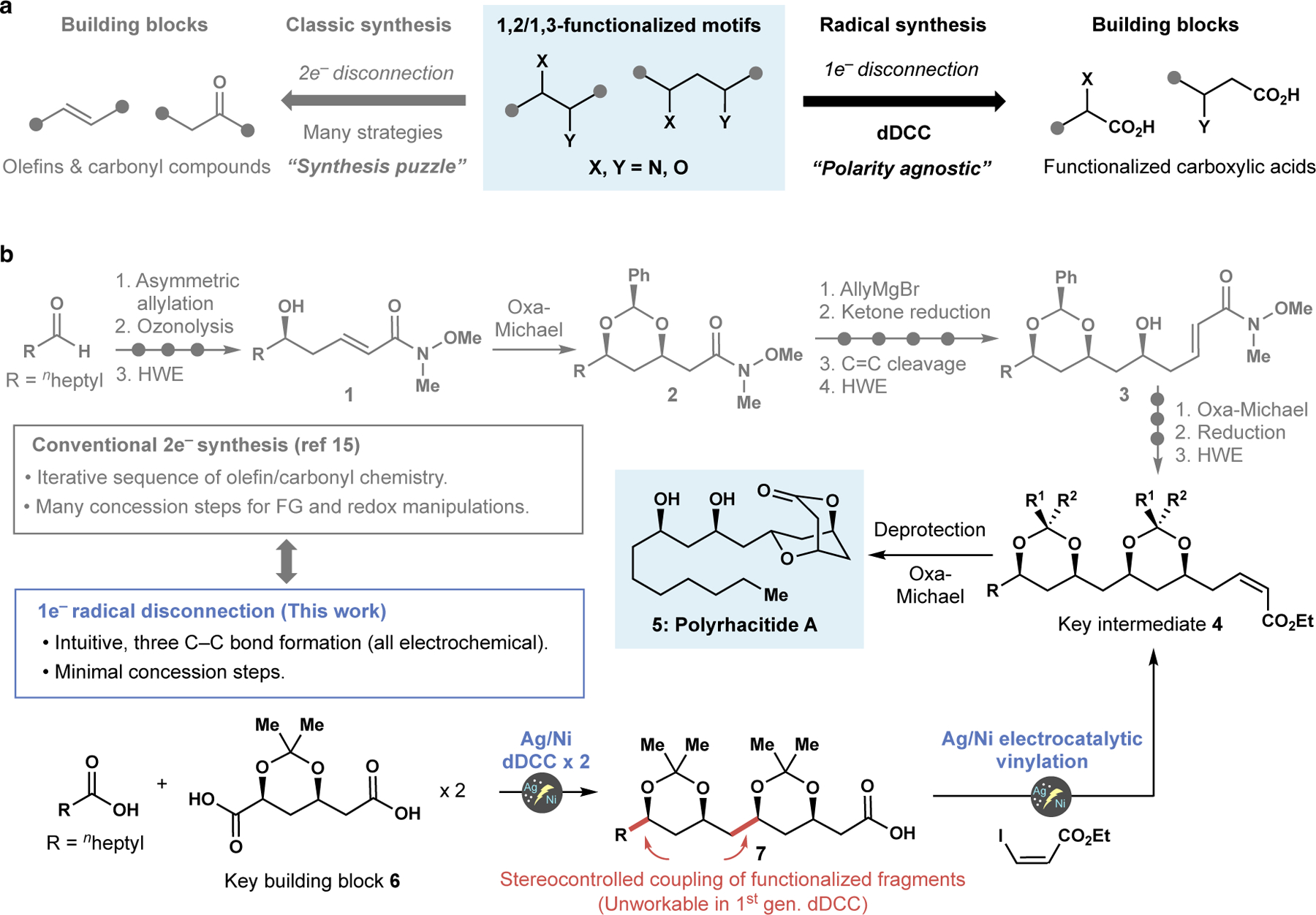

Figure 1. Accessing polyfunctionalized carbon framework via polar (2e−) and radical (1e−) disconnection.

a, A complex interplay of chemo-, regio- and stereochemical considerations is inevitable in classical 2e- disconnection, whereas 1e− logic provides a straightforward disconnection as carbon radicals can be generated at any position. b, A striking departure from conventional synthesis by employing radical disconnection. Three intuitive radical couplings could assemble polyrhacitide A, which was previously synthesized via common 2e− synthetic strategies (Ref 15). To achieve such an aspirational goal, dDCC needs to be successful on α-functionalized carboxylic acid with high diastereoselectivity.

Thousands of variants of these two-electron, polar reaction types have been reported thereby forming the bedrock of the logic of retrosynthetic analysis. Designing a route to complex structures using these methods can often involve a complex interplay of stereo-, regio-, and chemoselectivty considerations along with balancing proper redox states. As such, vast realms of protecting groups, reagents, and stereochemical rubrics have been developed to aid the practitioner in executing synthetic plans.1,3,4 Years of experience is necessary to appropriately deploy various reactions with successful synthetic strategies often being considered a form of “art”.10,11 Numerous computer-based algorithms and software packages have been launched to simplify synthesis design which is often equated with providing solutions to a complex puzzle.12

In contrast, a different approach to retrosynthesis that uses radical-based logic (1e− disconnection) to create new C–C bonds is emerging that can directly access previously challenging motifs, and in the process avoid downstream functional/protecting group manipulations and extraneous redox fluctuations.13 Since disconnections based on radical retrosynthesis are polarity agnostic, any C–C bond can, in principle, be constructed by the coupling of carbon radicals regardless of the surrounding functional groups. This, in turn, opens up completely different ways of making molecules since polarity assignments do not need to be the sole criteria to guide a logical disconnection. Instead, maximization of convergency and starting material availability/simplicity can serve as a primary guiding principle. Towards this end, doubly decarboxylative cross coupling (dDCC) is a powerful tool to realize this vision as it directly forges Csp3-Csp3 bonds between two carboxylic acids.14 Whereas the initial manifestation of this chemistry did not tolerate adjacent functional groups, herein we disclose a method to extend the scope of this reaction enabling the modular coupling of α-functionalized acids to access structures classically associated with 2e− synthetic strategies (Figure 1A).

The power of such a strategy for synthesis can be exemplified when considering the synthesis of polyrhacitide A (Figure 1B). This polyketide has the typical stereochemical array of 1,3-diol motifs; such structures have been made on countless occasions using classic 2e− synthetic strategies.15 As such, an iterative sequence of olefin/carbonyl chemistry involving allylation/ozonolysis/HWE/oxa-Michael is employed to construct the carbon framework with the requisite oxygen functionalities (key intermediate 4). This conventional approach is the result of decades of groundbreaking studies in polyketide synthesis to exquisitely control the stereochemical outcomes of C–C and C–O bond formation. However, one lingering drawback of this strategy is the many concession steps required to manipulate functional groups and adjust appropriate oxidation states.16,17 In stark contrast, a radical retrosynthetic approach to 4 could employ dDCC to sidestep many of these issues. Simply cutting bonds that lead to most accessible carboxylic acids results in a logical disconnection, thereby permitting only two simple acids to be stitched together, intuitively arriving at 4. In principle, only three C–C bond formation steps would be required without additional C–O bond formations or redox manipulations from octanoic acid and the key building block 6, which is readily accessible via one step from an inexpensive aldehyde containing 1,3-diol used to make statin-based medicines (See Supplementary Information for the preparation).

Two obstacles needed to be overcome to realize the vision set forth above (Figure 2A). First, an expansion of the initial dDCC scope to encompass substrates containing an α-heteroatom functionality was necessary. As a model system for this challenge, the coupling of proline derivative 8 and glycine derivative 9 was studied. First generation dDCC conditions afforded only 8% of the desired coupling product 10 along with a variety of decarboxylated products such as the corresponding pyrrolidine, dihydropyrrole, and proline dimer (see SI for details). These byproducts were indicative of substantial redox-active ester (RAE) reduction without productive coupling, a situation encountered previously in electrochemical decarboxylative vinylation and arylation studies.8,9 In that work, the key breakthrough involved the use of an in-situ generated Ag-nanoparticle deposited cathode, which primarily modulates multiple reduction events (e.g. concomitant reduction of Ni as well as RAE) on the cathode to improve the chance of successful coupling.9 Accordingly, this approach was tested for the dDCC coupling of 8 and 9. Indeed, by simply adding sub-stoichiometric amounts of Ag salt in addition to changing solvent (from DMF to NMP) and sacrificial anode material (from Zn to Mg), the yield of 10 was dramatically improved from 8% to 67% (see Supplementary Information for more details on reaction optimization as well as additional experiments to investigate te role of the Ag salt). The optimal ligand for this coupling was found to be tridentate ligands L1 and L2, the same type of ligands used in the previous dDCC study.

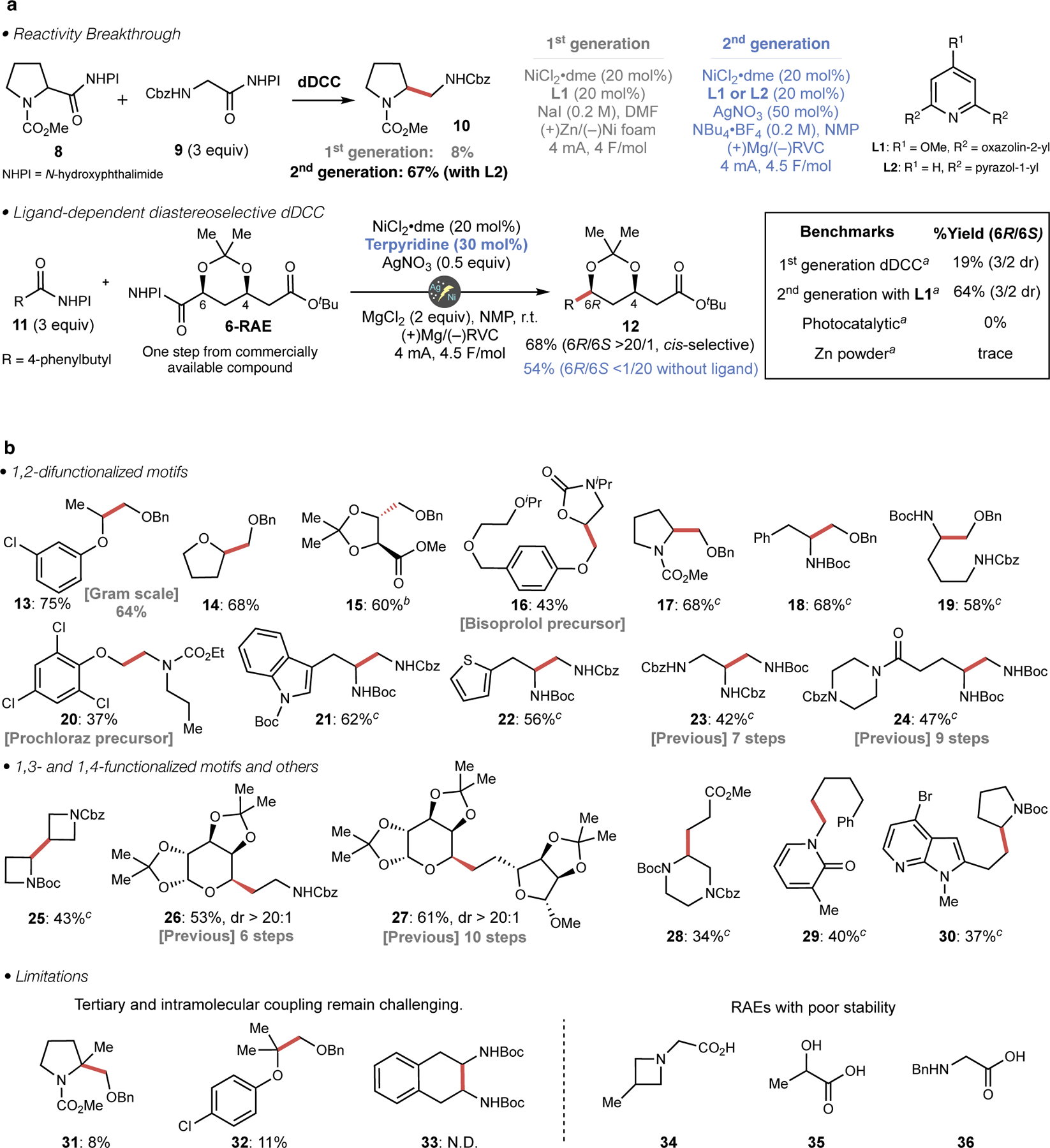

Figure 2. Development and scope of the 2nd-generation dDCC.

a, Ag-NP solved reactivity problem, whereas diastereoselectivity was found to be fine-tuned by Ni–ligand interaction. aDetailed reaction conditions are included in Supplementary Information. b, Reaction generality and limitation. Reactions were performed on 0.1 mmol scale with 3 equiv. of coupling partner RAE, 20 mol% NiCl2•dme, 20 mol% L1, 50 mol% AgNO3 and NBu4•BF4 (0.2 M) in NMP. bReaction was performed without a ligand, cL2 was used as a ligand instead of L1.

With the basic reactivity problem being solved, attention turned to the second obstacle: achieving diastereoselective coupling. In principle, 6 could serve as a versatile “cassette” that could be easily employed to make a vast array of polyketide natural products. Based on the assumption that the ligand could affect stereochemical outcome, those that were previously found to be effective for dDCC were re-screened. This extensive screen led to the discovery that terpyridine together with MgCl2 as Lewis acidic additive rendered the coupling highly diastereoselective, favoring the cis-diol product (6R)-12 (>20:1 dr). In striking contrast, the omission of ligand under these modified conditions still led to successful coupling, yet the diastereoselectivity was completely reversed to deliver trans-diol product (6S)-12 (>20:1 dr). This intriguing stereodivergence could be explained by delicate interplay of stereoelectronic effect of the carbon radical and steric effect of the Ni-catalyst. Namely, in the case of ligand-free system, anomeric effect of the radical18 favors axial substitution since Ni-catalyst is not sterically encumbered (leading to trans-isomer), whereas this effect is overridden by unfavorable 1,3-diaxial interactions in the case of ligated Ni-complex (see Supplementary Information for details). Additional experiments were conducted to determine if such a unique outcome could be translated into other analogous reaction manifolds. However, attempts to replicate this coupling under photochemical19 and metal-powder conditions20 were unsuccessful. The unique electrochemically enabled reactivity observed may stem from the fact that dDCC requires multiple concurrent reduction events: simultaneous reduction of two different RAEs along with reduction of Ni catalyst.14 Maintaining the subtle balance of these multiple reduction events may be a demanding task for alternative reductants. Regarding the generality of stereocontrol, high diastereoselectivity was observed on a variety of α-hydroxyacid derivatives (vide infra). α-aminoacids tend to give lower level of stereocontrol, yet observation of high diastereoselectivity in a certain case suggests that the stereochemical outcome is mostly substrate-controlled (see Supplementary Information for details).

With both the reactivity and stereoselectivity issue being solved for these key substrates, the basic reaction generality of these second-generation conditions to access densely functionalized carbon frameworks was evaluated (Figure 2B). dDCC between two α-heteroatom substituted acids directly affords 1,2-diol (13-16), aminohydroxy (17-20), diamino motifs (21-24) and higher order derivatives (25-30) from readily available carboxylic acids such as tartaric acid, amino acids and sugar derivatives. Accessing these classes of molecules often requires lengthy syntheses as indicated in the step-count of previous syntheses (16, 20, 23, 24, 26, 27, see Supplementary Information for complete route comparisons). Regarding the choice of ligand, L1 can be used universally (except for diastereoselective cases); L2 is useful when an amino acid-based RAE was employed as a substrate since it gives slightly improved yields in such cases. Although 3 equivalents of the RAE coupling partner are used throughout this study, reducing the amount to 1.5 equivalents could still afford the coupling product in synthetically useful yield (see Supplementary Information). Substrates 16 and 20 are the direct precursor for important medicines that are now accessible via modular routes relative to 2e− synthetic strategies. Molecules such as 25, 28-30 were prepared for ongoing drug discovery campaigns. As with other decarboxylative couplings, the current reaction could be easily scaled (13, conducted on gram-scale). Regarding the limitations of this method, forging fully substituted carbon centers results in lower yields (31, 32) and intramolecular couplings (33) are currently not tractable. Additionally, RAEs tend to have lower stability when highly nucleophilic functionalities are in proximity. Such RAEs are not applicable to the coupling (34-36). Finally, adoption of this reaction in high-throughput fashion is in progress (See Supplementary Information for preliminary results).

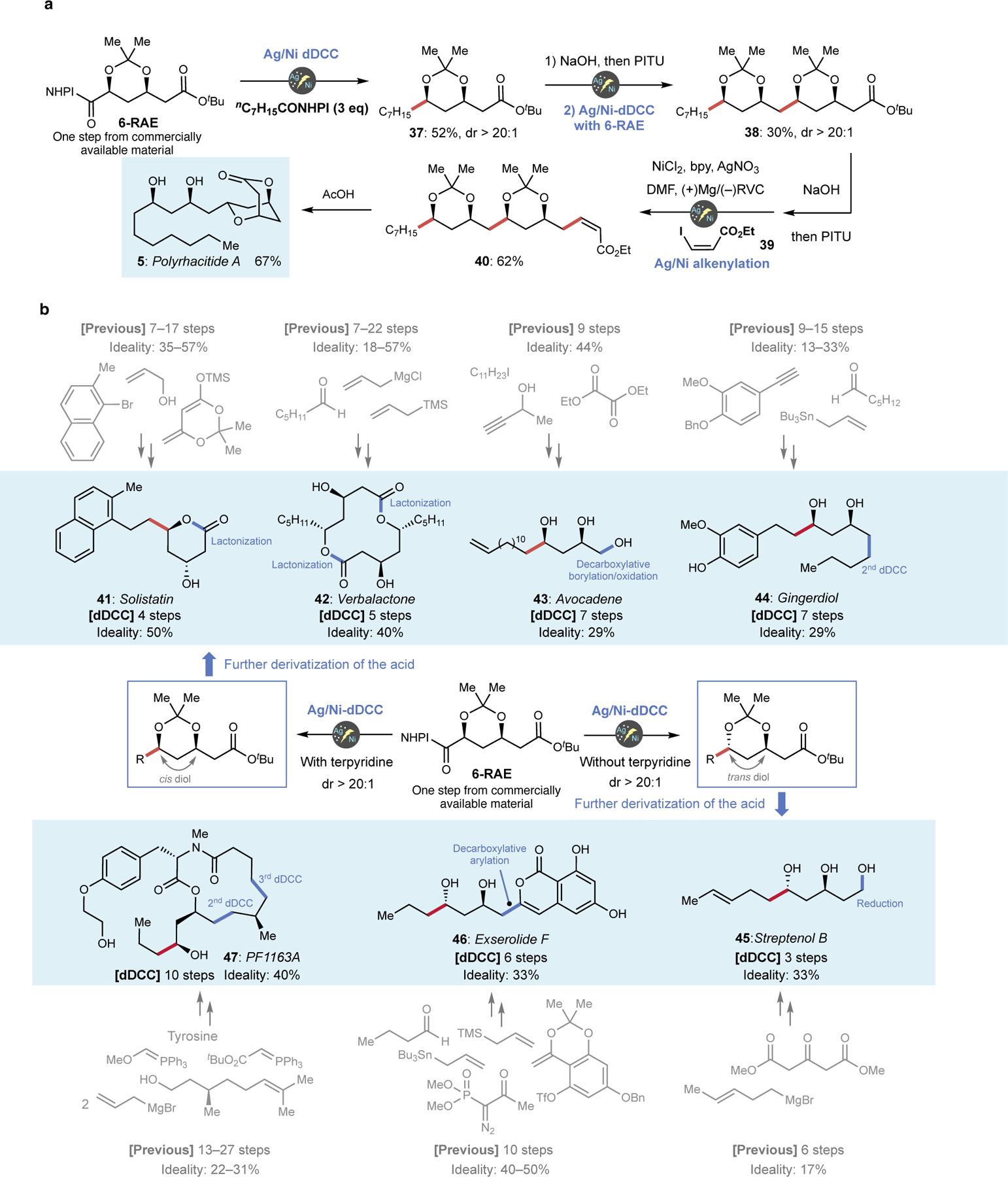

With an understanding of the scope of this transformation, a series of total syntheses were designed and executed to exemplify the powerfully simplifying nature of this new transformation. The vision set forth in Figure 1B was realized for the total synthesis of polyrhacitides A (5) as illustrated in Figure 3A. Thus, 6-RAE could be subjected to cis-selective dDCC with octanoic acid RAE, affording 37 in 52% isolated yield (>20:1 dr). Subsequent union of this fragment with another equivalent of 6-RAE after hydrolysis/RAE formation under cis-selective dDCC conditions furnished protected polyol ester 38 in 30% isolated yield (>20:1 dr). The third and final C–C bond forming event was accomplished again using another decarboxylative coupling method: decarboxylative alkenylation with vinyl iodide 39 to deliver 40 in 62% yield, which upon exposure to AcOH afforded the natural product 5 (67% yield). This intuitive approach to the construction of 5 is a striking departure from prior art (Figure 1B) and to polyketide synthesis in general. The overall strategy outlined for 5 could be employed seven more times for the divergent total syntheses of solistatine (41), verbalactone (42), avocadene (43), gingerdiol (44), streptenol B (45), exserolide (46), and PF1163A (47) resulting in reduced step-counts and improved ideality (Figure 3B). Notably, all previous routes to these natural products rely exclusively on polar-bond disconnections (see SI for the full detail and references).

Figure 3. Demonstration for radical simplification of natural product synthesis via 2nd-generation dDCC.

a, Concise synthesis of polyrhacitide A via iterative electrochemical decarboxylative coupling. b, Syntheses of 7 other natural products by utilizing the diastereoselective dDCC on 6.

Solistatin (41), isolated from Penicillium solitum and known to inhibit cholesterol synthesis,21 was previously prepared three times in 7–17 steps (57% ideality for the shortest route. Building blocks in the shortest route are also illustrated in Figure 3B), featuring stereoselective aldol reactions22 or iterative Overman esterification strategies.23 However, the aldol approach suffers from low diastereoselectivity (2:1), whereas the Overman approach requires multiple concession steps to set the stage for this rearrangement along with expensive chiral ligands and multiple uses of palladium. In contrast a cis-selective dDCC using the common diol unit 6-RAE completed the total synthesis in merely 4 steps (50% ideality) by quickly assembling the carbon skeleton followed by lactonization. Verbalactone (42), possessing unique activity against various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria,24 is an interesting case for analysis as it has been prepared at least 14 different ways ranging from 7–22 step-count (57% ideality for the shortest route). Although a macrolactonization approach to unite the two symmetrical fragment is common, accessing the key fragment requires multiple concession steps regardless of the strategy employed such as a combination of dithiane chemistry and chiral epoxide opening24,25 or asymmetric allylation.26 Again, the radical approach described herein employs a cis-selective dDCC on 6-RAE with hexanoic acid RAE followed by deprotection of the acetonide and tert-butyl ester, delivering the key symmetrical unit in a concise manner. Avocadene (43), isolated from the avocado tree (Persea americana), exibits anticancer activity against the human prostate adenocarcinoma as well as activity in the yellow fever mosquito larvae insecticidal assay.27 The previous synthesis of 43 proceeded in 9 steps (44% ideality) featuring a Noyori asymmetric reduction as well as a diastereoselective reduction of a β-hydroxyketone to establish the key 1,3-diol stereochemistry.27 In a significant departure from this conventional logic, cis-selective dDCC on 6-RAE with 13-tetradecenoic acid RAE set the stage for a 7-step synthesis of 43. To install the third hydroxyl group of 43, another radical reaction on the remaining carboxylate, decarboxylative borylation,28 was enlisted followed by oxidative workup. Gingerdiol (44), isolated from ginger rhizome,29 was previously prepared four times in 9–15 steps (33% ideality for the shortest route), featuring polar transformations such as Keck allylation,30 epoxide opening31 and iterative proline catalysed α-aminoxylation of an aldehyde.29 A more intuitive approach can be realized using cis-selective dDCC of 6-RAE with a functionalized phenylpropionic acid RAE, followed by another dDCC to complete the total synthesis of 44 (7 steps, 29% ideality).

The completely programmable diastereoselectivity of dDCC reactions on 6 (delivering cis- or trans-products at-will) could be also harnessed to access natural products bearing a trans-arrangement between diol motifs as illustrated in the next three total syntheses. For instance, streptenol B (45), a cholesterol synthesis inhibitor isolated from streptomyces species,32 was previously prepared in 6 steps as a racemate (17% ideality) with a poor diastereoselectivity in the Grignard reaction step.32 Trans-selective dDCC between 6-RAE and (E)-4-hexenoic acid RAE followed by acetonide deprotection and reduction of the remaining ester afforded 45 concisely (3 steps, 33% ideality). Exserolide F (46), isolated from plant endophytic fungus of Exserohilum species, demonstrates significant antimicrobial activity33 and was previously prepared twice in 10 steps (40 and 50% ideality).33,34 In both cases, substituted coumarin core was constructed via Sonogashira coupling followed by cationic cylization to furnish the lactone. In a complete departure from this strategy, the coumarin fragment could be incorporated via decarboxylative arylation8,9 after the trans-selective dDCC between butyric acid RAE and 6-RAE, halving the step-count (6 steps, 33% ideality). Finally, PF1163A (47), isolated from the fermentation broth of Penicillium sp. and possessing antifungal activity by inhibiting ergosterol synthesis,35 was previously prepared on four different occasions in 13–27 steps (31% ideality in the shortest route). Conventional tactics such as asymmetric allylation,36,37 HWE,35,36 RCM,35,37 asymmetric epoxidation37 for establishing C–C and C–O bonds with the requisite stereochemistry. A more intuitive LEGO-like approach was enabled through three distinct uses of dDCC. Thus, a trans-selective dDCC between 6-RAE and butyric acid RAE followed by two additional dDCC reactions stitched together the carbon skeleton. The macrolactamization after coupling with a tyrosine derivative to complete the molecule has been described in the previous route35; thus 10-step formal synthesis has been accomplished (40% ideality). Aside from route simplification and step-count reduction observed in all of the above syntheses, Grignard reagents, expensive transition metals, diazo compounds, Wittig reactions, complex chiral ligands, and toxic tin reagents were entirely avoided.

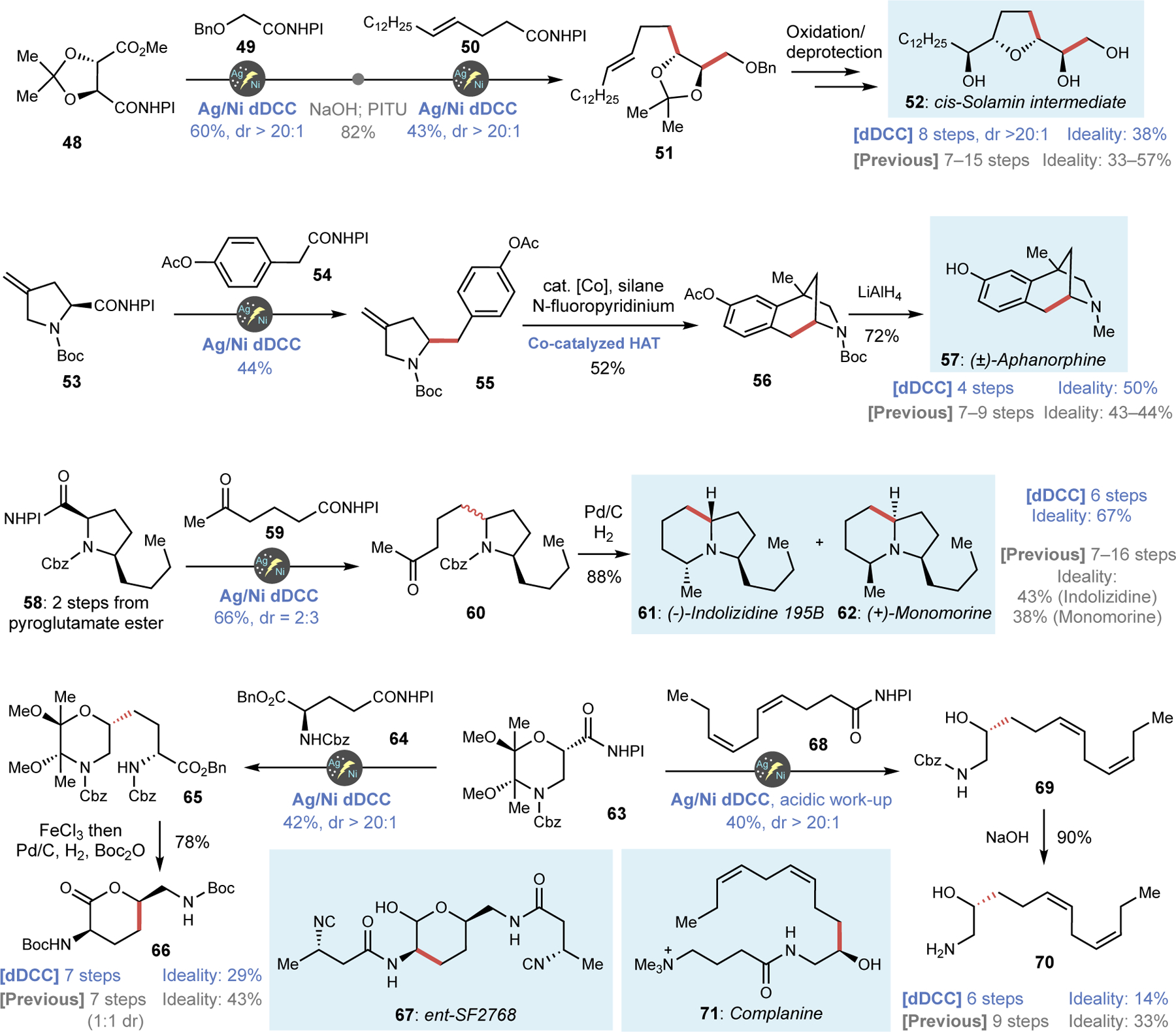

The case studies depicted above only scratch the surface of what is possible using dDCC as applied to complex natural product synthesis. Figure 4 illustrates further the power of dDCC for another 6 natural product syntheses using unique carboxylic acid building blocks. cis-Solamin was isolated from the roots of Annona muricata and is a potent cytotoxic compound that inhibits the mitochondrial respiratory enzyme complex I (NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase).38 Intermediate 52 is a well-established precursor for cis-Solamin and has been prepared three times in 7–15 steps (33–57% ideality) based on conventional 2e− synthetic strategies with extensive use of olefin functionalization and phosphonium ylide chemistry.38 The radical approach described herein uses one of the most abundant chiral building blocks available, tartaric acid. Thus, sequential dDCC couplings (proceeding in 60% and 43% yield with perfect diastereocontrol) between readily available 48 with simple acids 49 and 50 enabled the rapid assembly of the main chain, followed by a simple stereocontrolled dihydroxylation/cyclization and deprotection to afford 52 in 8 steps (38% ideality). Aphanorphine (57), isolated from the freshwater blue-green algae named aphanizomenon flos-aquae,39 has attracted considerable attention from the synthetic community with more than 20 syntheses reported (shortest 7 steps, 43% ideality). By utilizing readily available proline-derived olefin 53, a dDCC with RAE 54 rapidly provided intermediate 55 which underwent Shigehisa’s Co-catalyzed HAT cyclization40,41 followed by reduction to complete the synthesis of 57 in only 4 steps (50% ideality). Notably, both key C–C bond forming events relied on recently developed 1e− transformations. (−)-Indolizidine 195B (61) and (+)-Monomorine I (62) are poisonous alkaloids secreted from ants and amphibians that have attracted extensive synthetic studies, being prepared 10 and 20 times, respectively.42 Despite their structural similarity, most of the reported routes have targeted each molecule independently rather than through a divergent path delivering both diastereomers. A non-stereocontrolled dDCC between pyroglutamate-derived 58 and ketoacid RAE 59 to afford 60 as a 2:3 mixture of diastereomers was intentionally deployed to access both 61 and 62 at the same time. Following reductive C–N bond formation, the divergent synthesis of these two alkaloids was accomplished in 6 steps with 67% ideality

Figure 4. Natural product syntheses based on various chiral carboxylic acids enabled by 2nd-generation dDCC.

Various classes of natural products including alkaloids and peptides were also accessible by dDCC from suitable carboxylic acid building blocks.

Drawing inspiration from Ley’s pioneering studies on dioxane-based chiral auxiliaries,43 the morpholino-acid RAE 63 was designed as a precursor to the 1,2-aminoalcohol motif (synthesized in 4 steps, see Supplementary Information) and employed in the formal synthesis of two unrelated amine-containing natural products. The first of these was SF2768 (67), a unique alkaloid containing an isonitrile functionality, with biological relevance in the area of bacterial copper homeostasis.44 The key hydroxylysine unit 65 was previously constructed by lengthy functional group manipulations of a chiral building block with poor stereocontrol (1:1).44 By using a stereocontrolled dDCC approach commencing from 63 and glutamate 64, this key fragment 65 can be accessed in a single step (42% yield, >20:1 dr) followed by exchange of the Cbz to Boc group to complete the synthesis of the key intermediate in 7 steps. The second natural product prepared from 63, complanine (71), is an amphipathic substance isolated from the marine fireworm, Eurythoe complanata.45 The prior synthesis was accomplished via homologation of an alkyne followed by the construction of amino alcohol motif by using enantioselective nitrosoaldol reaction.45 Stereoselective dDCC between 63 and RAE 68 (40% yield, >20:1 dr) followed by Cbz deprotection afforded chiral amino alcohol 70 in 6 steps. More importantly, the modular approach outlined here is attractive from a medicinal chemistry standpoint wherein numerous chiral 1,2-aminoalcohols could be conceivably evaluated in a library-format using readily available carboxylic acids.

To summarize, newly identified Ag-nanoparticle enabled conditions to expand the scope of dDCC to encompass α-heteroatom substituted carboxylic acids can lead to a dramatic simplification of the synthesis of molecules that have historically been prepared through conventional polar retrosynthetic analysis. For the 14 natural products prepared herein, application of radical retrosynthesis realized by the dDCC tactic required 88 steps overall compared to prior routes ranging from 117–174 steps. The remarkable ability of this Ag-Ni-facilitated dDCC to be diastereocontrolled in the presence or absence of ligands on substrate 6 offers an intriguing LEGO-like approach for the synthesis of polypropionates. On average, dDCC-based syntheses required 6 steps to complete and deleted an array of protecting groups, redox manipulations, functional group interconversions, Wittig/Grignard reagents, pyrophoric reagents, toxic/non-sustainable metals, expensive chiral ligands, and diazo compounds that still beleaguer modern synthesis. The approach outlined herein points to a fundamentally different approach to retrosynthetic analysis that is far more intuitive and easier to execute.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. D.-H. Huang and Dr. L. Pasternack (Scripps Research) for NMR spectroscopic assistance, Dr. Jason Chen and Quynh Nguyen Wong (Scripps Automated Synthesis Facility) for assistance with HRMS.

Funding

Financial support for this work was provided by National Science Foundation Center for Synthetic Organic Electrochemistry (CHE-2002158, for optimization of reactivity and initial scope), and the National Institutes of Health (grant number GM-118176, for the application of the method to natural product synthesis). We also thank George E. Hewitt Foundation (G.L.) for the support.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data Availability.

The data that support the findings in this work are available within the paper and Supplementary Information.

References

- 1.Corey EJ & Cheng X-M Logic of chemical synthesis (Wiley, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seebach D Methods of Reactivity Umpolung. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 18, 239–258 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warren SG & Wyatt P Organic synthesis: the disconnection approach (Wiley, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann RW Elements of synthesis planning (Springer, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayden J, Greeves N & Warren SG Organic chemistry (OUP Oxford, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kürti L & Czakó B Strategic applications of named reactions in organic synthesis (Elsevier Science, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith MB March’s Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (Wiley, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palkowitz MD et al. Overcoming Limitations in Decarboxylative Arylation via Ag–Ni Electrocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 144, 17709–17720 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harwood SJ et al. Modular terpene synthesis enabled by mild electrochemical couplings. Science 375, 745–752 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolaou KC, Sorensen EJ & Winssinger N The Art and Science of Organic and Natural Products Synthesis. J. Chem. Educ 75, 1225–1258 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolaou KC, Vourloumis D, Winssinger N & Baran PS The Art and Science of Total Synthesis at the Dawn of the Twenty‐First Century. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 39, 44–122 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen Y et al. Automation and computer-assisted planning for chemical synthesis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 1, 23 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JM, Harwood SJ & Baran PS Radical Retrosynthesis. Acc. Chem. Res 51, 1807–1817 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang B et al. Ni-electrocatalytic Csp3–Csp3 doubly decarboxylative coupling. Nature 606, 313–318 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadav JS & Rajendar G Stereoselective Total Synthesis of Polyrhacitides A and B. Eur. J. Org. Chem 6781–6788 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaich T & Baran PS Aiming for the Ideal Synthesis. J. Org. Chem 75, 4657–4673 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters DS et al. Ideality in Context: Motivations for Total Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res 54, 605–617 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giese B & Dupuis J Anomeric effect of radicals. Tetrahedron Lett 25, 1349–1352 (1984) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Ma D & Zhang Z Utilization of photocatalysts in decarboxylative coupling of carboxylic N-hydroxyphthalimide (NHPI) esters. Arab. J. Chem 15, 103922 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldfogel MJ, Huang L & Weix DJ in Nickel Catalysis in Organic Synthesis 183–222 (Wiley, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halperin SD & Britton R Chlorine, an atom economical auxiliary for asymmetric aldol reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem 11, 1702–1705 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borg T, Danielsson J & Somfai P Mukaiyama aldol addition to α-chloro-substituted aldehydes. Origin of the unexpected syn selectivity. Chem. Commun 46, 1281–1283 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binder JT & Kirsch SF Iterative approach to polyketide -type structures: stereoselective synthesis of 1,3-polyols utilizing the catalytic asymmetric Overman esterification. Chem. Commun 4164–4166 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanjivaka S et al. An alternative stereoselective total synthesis of Verbalactone. Arkivoc 50–57 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J-Z et al. Facile access to some chiral building blocks. Synthesis of verbalactone and exophilin A. Tetrahedron 65, 289–299 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allais F, Louvel M-C & Cossy J A Short and Highly Diastereoselective Synthesis of Verbalactone. Synlett, 0451–0452 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunha VLS, Liu X, Lowary TL & O’Doherty GA De Novo Asymmetric Synthesis of Avocadyne, Avocadene, and Avocadane Stereoisomers. J. Org. Chem 84, 15718–15725 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J et al. Cu-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Borylation. ACS Catal 8, 9537–9542 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markad SB, Bhosale VA, Bokale SR & Waghmode SB Stereoselective Approach towards the Synthesis of 3R, 5 S Gingerdiol and 3 S, 5 S Gingerdiol. ChemistrySelect 4, 502–505 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabitha G, Srinivas C, Reddy TR, Yadagiri K & Yadav JS Synthesis of gingerol and diarylheptanoids. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 22, 2124–2133 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wan Z, Zhang G, Chen H, Wu Y & Li Y A Chiral Pool and Cross Metathesis Based Synthesis of Gingerdiols. Eur. J. Org. Chem 2128–2139 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blechert S & Dollt H Synthesis of (−)‐Streptenol A, (±)‐Streptenol B, C and D. Liebigs Ann 2135–2140 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mallampudi NA, Reddy GS, Maity S & Mohapatra DK Gold(I)-Catalyzed Cyclization for the Synthesis of 8-Hydroxy-3- substituted Isocoumarins: Total Synthesis of Exserolide F. Org. Lett 19, 2074–2077 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dumpala M, Kadari L & Krishna PR Brønsted acid promoted intramolecular cyclization of O-alkynyl benzoic acids: Concise total synthesis of exserolide F. Synthetic Commun 48, 2403–2408 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar H, Reddy AS & Reddy BVS The stereoselective total synthesis of PF1163A. Tetrahedron Lett 55, 1519–1522 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tatsuya K, Takano S, Ikeda Y, Nakano S & Miyazaki S The Total Synthesis and Absolute Structure of Antifungal Antibiotics (−)-PF1163A and B. J. Antibiotics 52, 1146–1151 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishna PR & Srinivas P Total synthesis of the antifungal antibiotic PF1163A. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 23, 769–774 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li N, Shi Z, Tang Y, Chen J & Li X Recent progress on the total synthesis of acetogenins from Annonaceae. Beilstein J. Org. Chem 4, 48 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gulavita N, Hori A, Shimizu Y, Laszlo P & Clardy J Aphanorphine, a novel tricyclic alkaloid from the blue-green alga Aphanizomenon flos-aquae. Tetrahedron Lett 29, 4381–4384 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shigehisa H, Ano T, Honma H, Ebisawa K & Hiroya K Co-Catalyzed Hydroarylation of Unactivated Olefins. Org. Lett 18, 3622–3625 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang C & Guan Y Concise Total Synthesis of (+)-Aphanorphine. Synlett 32, 913–916 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziarani GM, Mohajer F & Kheilkordi Z Recent Progress Towards Synthesis of the Indolizidine Alkaloid 195B. Curr. Org. Synth 17, 82–90 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harding CI, Dixon DJ & Ley SV The preparation and alkylation of a butanedione-derived chiral glycine equivalent and its use for the synthesis of α-amino acids and α,α-disubstituted amino acids. Tetrahedron 60, 7679–7692 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Y & Tan DS Total Synthesis of the Bacterial Diisonitrile Chalkophore SF2768. Org. Lett 21, 8731–8735 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamanos KAD & Withey JM Enantioselective total synthesis of (R)-(−)-complanine. Beilstein J. Org. Chem 8, 1695–1699 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings in this work are available within the paper and Supplementary Information.