Abstract

Background:

Demographic diversity is not represented in the HIV/AIDS workforce. Engagement of underrepresented trainees as early as high school may address this disparity.

Methods:

We established the Penn Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Scholars Program, a mentored research experience for underrepresented minority (URM) trainees spanning educational stages from high school to medical school. The program provides participants with tailored educational programming, professional skill building, and mentored research experiences. We conducted qualitative interviews with scholars, mentors, and leadership to evaluate the program impact.

Results:

11 participants were selected to partake in one of five existing mentored research programs as CFAR Scholars. Scholars attended an 8-week HIV Seminar Series that covered concepts in the basic, clinical, behavioral, and community-based HIV/AIDS research. Program evaluation revealed that Scholars’ knowledge of HIV pathophysiology and community impact increased due to these seminars. In addition, they developed tangible skills in literature review, bench techniques, qualitative assessment, data analysis, and professional network-building. Scholars reported improved academic self-efficacy and achieved greater career goal clarity. Areas for improvement included clarification of mentor-mentee roles, expectations for longitudinal mentorship, and long-term engagement between scholars. Financial stressors, lack of social capital, and structural racism were identified as barriers to success for URM trainees.

Conclusion:

The Penn CFAR Scholars Program is a novel mentored research program that successfully engaged URM trainees from early educational stages. Barriers and facilitators to sustained efforts of diversifying the HIV/AIDS workforce were identified and will inform future program planning.

Keywords: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; HIV/AIDS Research; Curriculum Development; Evaluation

Background

Equitable racial/ethnic and gender representation within academic research and healthcare settings remains elusive in 2023 despite concerted efforts to combat this phenomenon1,2. For instance, ethnic and racial minority populations have remained woefully underrepresented among medical school enrollees since 1980, with disparities worsening between 2000 and 20193. Further, both racial/ethnic and gender underrepresentation only increase with academic seniority4–7, highlighting steady attrition of minority populations throughout the training and professional continuum. As far as the scientific workforce is concerned, recent evaluations of grant award rates for non-White principal investigators suggest systemic barriers in both basic8 and biomedical research9 funding success for minority investigators. While less is known specifically about the HIV/AIDS research workforce, data suggest that similar trends are present. In fiscal year 2021, only 2.6% of research grant applicants to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) were from Black/African American principal investigators10; thus, the research questions contributing to scientific advancement in the field are not likely to reflect the “diverse perspectives, backgrounds, and skill sets” needed to address racial/ethnic disparities in HIV care outcomes11. Similar trends are seen for the clinical workforce. A 2016 study showed that only 5.8% of providers entering the HIV workforce identified as Black/African American, a figure that poorly reflects the relative size of this minority group in the US population and the disparate HIV burden experienced by Black Americans12,13.

In 2021, the Penn Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) responded to a call from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to participate in the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Pathway Initiative (CDEIPI) to improve representation of trainees engaged “in HIV science at the high school, undergraduate, graduate[,] and post-doctoral levels.” Here, we describe the structure of our program, logic model guiding our work, and program evaluation to date.

Methods

Program description

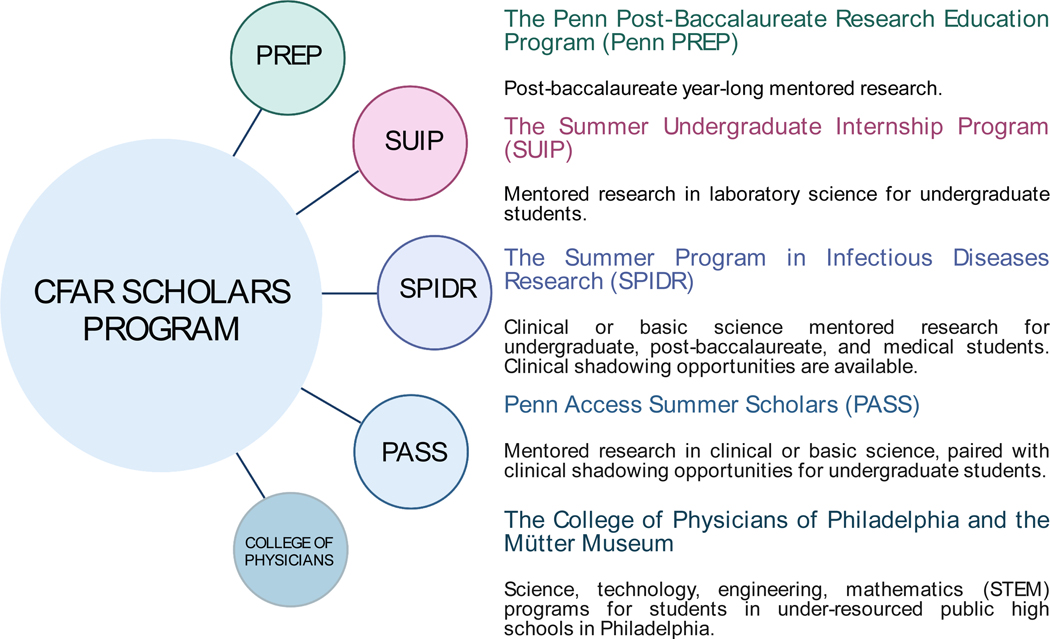

The Penn CFAR Scholars Program was established in 2022 to provide mentored research opportunities for students from URM backgrounds. To address the diversity of levels of training and career interests, we leveraged five existing enrichment programs, hereon called “home programs,” by expanding trainee slots, creating HIV-specific content, and facilitating mentored research opportunities (Figure 1). These five home programs included: (a) a 2-week high school program; (b) a 10-week summer undergraduate research program in laboratory science; (c) an 8-week summer undergraduate/post-baccalaureate/medical program in infectious diseases research; (d) a summer undergraduate research program focused on facilitating students’ entry into medical school that spans two summers; and (e) a year-long post-baccalaureate program focused on laboratory science. As a result of dual appointment in diverse home programs and the CFAR Scholars program, the scope of trainee career interests reflected the spectrum of HIV basic and clinical research. Each scholar received a stipend, a meal plan, and on-campus housing.

Figure 1.

Program Structure. The Penn CFAR Scholars Program leveraged five existing home programs on campus that accepted URM trainees ranging from high school students to medical students. SPIDR: https://www.pennmedicine.org/departments-and-centers/department-of-medicine/divisions/infectious-diseases/education-and-training/diversity-and-inclusion/spidr-summer-program. SUIP: https://www.med.upenn.edu/idealresearch/suip/. PREP: https://www.med.upenn.edu/idealresearch/prep/. PASS: https://www.med.upenn.edu/admissions/special-programs.html. CoP: https://collegeofphysicians.org/programs.

Applicant selection

Selection criteria differed based on home program. All applicants submitted: (1) a curriculum vitae; (2) two letters of recommendation; and (3) a personal statement. In general, admissions committees used the NIH definition of URM14, which includes race/ethnicity and other minority statuses (socioeconomic background, immigrant status, disability and others) as criteria. Criteria for evaluation included prior academic achievements, research experience and potential, motivation, maturity, and clarity of career goals toward biomedical and clinical research.

Logic model

We applied a logic model framework for program planning, implementation, and evaluation15.

Evaluation

As part of the central CDEIPI evaluation, scholars completed an anonymous survey common to all CDEIPI sites (see Magnus, et al. in this supplement)20. To assess the Penn CFAR Scholars Program with greater granularity, we conducted 22 individual structured interviews with scholars, research mentors, and program leadership. Interview guides included common themes among all three groups about experience with the program, affective evaluation of attitudes toward program components, program’s impact on stated goals, and future directions. Tailored questions were included for each group; scholars were asked about skills learned and changes to career goals, mentors about long-term scholar engagement, and leadership about program sustainability. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed using a grounded theory approach16. Researchers independently coded the transcripts and met to resolve any differences in coding17. Outcomes, including measures of scholarly productivity such as papers, abstracts, conference attendance, graduate school acceptance, and residency matching, were tracked. This study was evaluated by the Penn IRB and deemed exempt. All participants consented to interviews.

Results

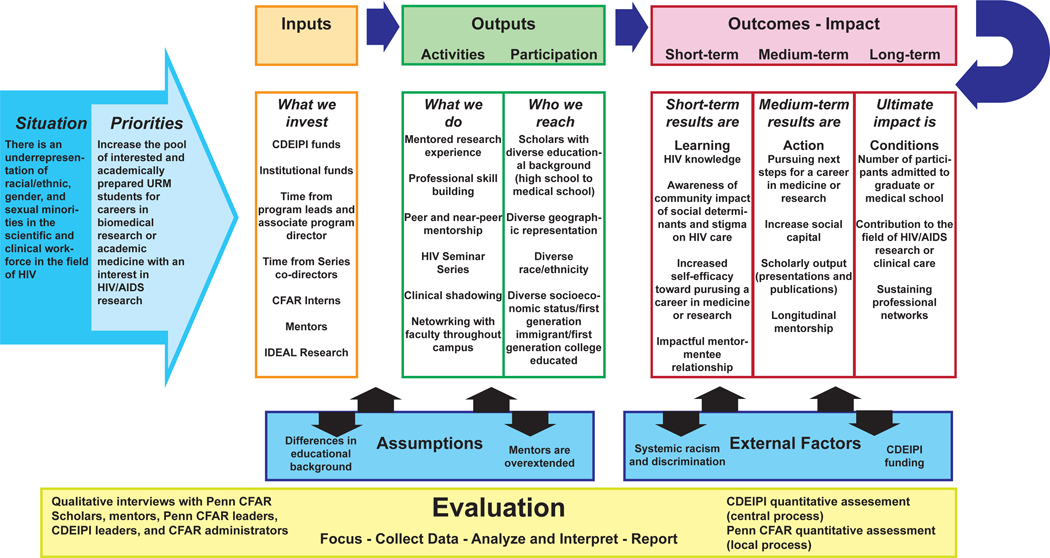

1.A. Logic model

Figure 2 displays the logic model that guides our work. This model was used to identify priorities, design program activities, and conceive of outcome measures, all while leveraging existing resources. The socioeconomic context of the scholars and the larger climate informed programmatic decisions (e.g., limiting spots to provide housing and meals for all accepted scholars). The logic model also guided our program performance evaluation, which in turn will inform evolution of the logic model through iterative refinement.

Figure 2.

Logic Model. Adapted from the South Carolina Department of Education.

1.B. Penn CFAR Scholars First Cohort

Eleven scholars were accepted into the inaugural 2022 Program and matched with eleven mentors. They came from diverse educational levels ranging from high school to medical school and were enrolled at institutions from across the country. Of the eleven scholars, 55% identified as Black, 27% White Hispanic, and 18% Asian (Table 1). Their average age was 21 years and 55% identified as women. The inclusion of scholars across academic levels was intentional to facilitate peer/near-peer mentoring through frequent interaction in mentoring sessions and group work in the HIV Seminar Series.

Table 1:

Participant details

| Home Institution | Research Focus | Research Institution | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUIP CFAR Scholars | |||

| Amherst College, MA | Basic/translational science | Perelman School of Medicine | Returning Summer 2023 |

| Howard University, Washington DC * ^ | Basic/translational science | Wistar Institute | Matriculation to PhD Program |

| PennPREP-CFAR Scholars | |||

| South Texas College, TX ^ | Basic/translational science | Perelman School of Medicine | Matriculation to PhD Program |

| Lawrence University, WI | Clinical science | Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania | Matriculation to PhD Program |

| PennPASS-CFAR Scholars | |||

| Bryn Mawr College, PA | Implementation science | Perelman School of Medicine | Returning Summer 2023 |

| Princeton University, NJ | Implementation science | Perelman School of Medicine | Returning Summer 2023 |

| SPIDR-CFAR Scholars | |||

| Columbia University, NY | Clinical science | Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania | Pursuing Medical School |

| University of Rochester, NY | Basic/translational science | Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania | Pursuing Medical School |

| University of Michigan, MI | Implementation science | University of Pennsylvania | Pursuing Graduate School |

| Mercer University School of Medicine, GA | Implementation science | Perelman School of Medicine | Matched into Residency |

| College of Physicians-CFAR Scholars | |||

| Central High School, PA | Basic/translational science | Perelman School of Medicine | Continuing High School |

= Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)

= Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs)

2. Human, Financial, and Institutional Resources

Program leaders are primarily HIV researchers ranging from graduate students to professors. Mentors and faculty contributors came from diverse institutions including the School of Medicine, School of Dental Medicine, School of Veterinary Medicine, School of Engineering and Applied Science, College of Arts and Sciences, Leonard David Institute, Institute for RNA Innovation, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), and Wistar Institute. These institutions are located on the same campus and academically intertwined. The entire campus is contained in a ten square-block area, while the biomedical science component resides within a two square-block nucleus.

The Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Learner Experience Program (IDEAL XP) is an existing entity on campus that aims to recruit, train, and retain URM students. IDEAL XP assisted with application dissemination and collection, on-boarding, housing, and meal plans.

In addition to grant support from the CDEIPI, funds were secured from the Perelman School of Medicine, Penn and CHOP Divisions of Infectious Diseases, and NIH grants listed in the acknowledgements. Based on the success of our first cohort, we secured additional funds from the Penn CFAR Implementation Science Working Group and Institute for RNA Innovation to expand the program by five slots for the 2023 cycle.

3. Program Components

3.A. HIV Seminar Series

The HIV Seminar Series was developed specifically for the CFAR Scholars assuming little-to-no background knowledge. It exposed Scholars to key concepts in the basic, clinical, behavioral, and community-based HIV research, highlighting research methods while framing discovery in greater societal contexts. Sessions were: Introduction to HIV, Origin and Spread of the HIV Pandemic, ART and Resistance, HIV Screening and Prevention Strategies, Disparities and Intersectionality in HIV Burden and Treatment, Pediatric Considerations in HIV Care, and HIV Cure and Eradication Efforts. Scholars received instruction from both program leadership and expert guests, themselves HIV researchers at Penn. Each session lasted 90 minutes and was structured to elicit discussion. Sessions were attended by an activist and community advisory board member of the Penn Mental Health AIDS Research Center who provided a personal voice and community/patient perspective.

3.B. Professional Development

Professional skill programming was hosted by Scholars’ home program (leveraging existing resources, Figure 1) and the Penn CFAR Scholars Program. These latter meetings, which comprised of informal round-table discussions, were designed to create networking opportunities. Scholars were introduced to additional faculty and trainees with the goal of developing rich mentoring networks on top of their existing peer networks. Additionally, a program co-lead met with each CFAR scholar to gain insight into their career goals and facilitate introductions to relevant experts.

3.C. Mentored research

Scholars were paired with mentors based on their interests and participated in new or on-going research projects. Topics ranged from assessing cognitive and depressive symptoms among adolescents living with HIV in Botswana to preclinical evaluation of immune-based HIV treatments. The program’s flexibility and rich network of investigators allowed for tailored research experiences. For instance, one scholar conducted a survey evaluating a home-based HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) program while another investigated delivery of anti-HIV antibodies using mRNA gene therapy. Most scholars have continued to engage with their research mentors after completion of the program.

4. Program evaluation

4.A. Interview Themes: 2022 Program Evaluation

A pair of qualitative researchers conducted interviews with 22 stakeholders (9 scholars, 7 mentors, and 6 CFAR program leaders) and observed common themes upon analysis of interview results. Scholars self-reported little subject knowledge prior to entering the program and that participation in the Seminar Series increased their knowledgebase. Many scholars appreciated the larger context that the Series provided because they felt there was insufficient time to glean this knowledge in their mentored research experiences. In Table 2, we describe the strategies integrated into the HIV Seminar Series that scholars found helpful. They include repetition of key concepts, tailoring material to the learners’ educational level, and focusing on the impact of HIV on marginalized communities. They also reported that the HIV Seminar Series reduced the stigma they felt toward people living with HIV by having a community member with lived HIV experience in the room. One scholar, who was a medical student, reported this interaction would impact their readiness to provide care for someone living with HIV.

Table 2:

Strategies employed to enhance scholars’ learning and experience

| Program component: HIV Seminar Series | |

| Strategies to tailor program to diverse group of trainees | |

| Repetition |

“Just hearing, you know, ‘CD4 T cells’ over and over and over again. It was like, I really knew -- it helps me when I went to do my presentation that I really knew what I was talking about.” Scholar 101

“I thought that was good and I definitely got used to hearing the lingo like ‘U equals U’ and now that’s something that I guess I know[. I]t was interesting to see how they kept coming up with those themes throughout the lectures.” Scholar 105 |

| Tailor HIV knowledge to learner’s level | “That [the HIV seminar] was definitely helpful in just understanding like how the disease works... Like on a really micro level, things that people in my lab kind of assumed that I would learn somewhere else, this is where I was learning it.” Scholar 101 |

| Strategies to increase awareness of the impact of HIV on marginalized communities | |

| Integrating the perspective of an individual with lived HIV experience | “It’s like, ‘hey, here in the city, people are more open to sharing.’ Like, ‘hey, I do have HIV but it’s not the end of the world.’” Scholar 109 |

| Training on use of non-stigmatizing language | “just ways to be more like respectful to the community, instead of just saying… ’oh, this is a gay man’s disease.’ It’s just like, you know, you say, men who have sex with men, you say people with HIV not, you know, there’s certain phrases that are just like more -- like correct.” Scholar 101 |

| Emphasis on disparate impact of HIV on racial and ethnic minority communities | “As such, the seminar made me realize the disproportionate realities of HIV impacting certain ethnic groups and how important it is to address the systematic racism, prejudice, stigma and internal biases to help the ethnic groups.” Scholar 111 |

| Program component: Professional Skills Development | |

| Increasing self-efficacy | “I still think there’s a lot I need to learn to do it, but I think questioning my ability to do it is very different and I don’t think I will question my ability.” Scholar 103 |

| Professional networking | “after the exposure to this program, I feel confident that I could pursue a career in research. I think the support and like the social networking of the mentors in the program made it more likely because I worked alongside with them, I learned about their field, and I’ve seen how they would collaborate with other researchers with their own specific research.” Scholar 111 |

| Program component: Mentored research | |

| Tailoring research project to learner’s level | “It was definitely something new. I’ve never done research in the past, so it was new territory but it was a good experience overall. I definitely learned a lot. I would say my lab was fast-paced, but I was able to catch up but it was a good experience with that.” Scholar 108 |

| Mentor-mentee relationship | “During the course of the program, [Mentor] and I got super close, especially through the [Program] and then also through the shadowing and mentorship opportunities they gave us” Scholar 106 |

| Programs facilitating transition from undergraduate to graduate school | |

| Longitudinal mentorship | “So I’m super grateful to have had them as a mentor and I’m looking forward to also working with them next summer.” Scholar 106 |

All scholars acquired tangible skills that would make them more competitive applicants for graduate or professional school. Most scholars reported that they were able to build meaningful connections with their mentors, although some struggled with unclear mentorship structure and one was unable to form a meaningful connection. Mentors reported a desire to stay in touch with their mentees but placed the responsibility for this interaction on the mentee. All scholars reported that program participation impacted their intended career paths, though that impact differed. Most scholars entered the program with an interest in applying to medical school and left with that intention solidified. In contrast, program participation reinforced one scholar’s desire to apply to graduate school and not medical school. Approximately twenty percent of scholars reported the program led them to consider a career in Infectious Diseases (ID).

A major focus of the program and seminar series was to introduce scholars to research techniques. Both scholars and mentors described a myriad of acquired skills including: literature review, experimental design and implementation, quantitative and qualitative analysis, and survey development. Mentors reported that an impactful aspect of the research experience was asking scholars which hard skills they wanted to work on and tailoring their mentorship to build those skills. Other mentors said that the program will enhance scholars’ resumes and give them strong talking points in interviews for medical and graduate school. One mentor described how their mentee was able to explore an academic environment that differed substantially from their home institution, both in a different geographic setting and with a radically different racial/ethnic composition.

4.B. Interview Themes: Barriers and Facilitators

The themes related to barriers and facilitators of URM students’ success and retention in academia are summarized in Table 3. In general, identified barriers fell under four overarching themes: financial stressors for URM trainees, lack of experience or social capital for certain URM students, lack of research infrastructure in Historically Black College or University (HBCUs) or Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs), and systemic racism and discrimination.

Table 3:

Barriers and facilitators to sustaining efforts of diversifying the field of HIV/AIDS

| Barriers to sustaining efforts of diversifying the field of HIV/AIDS | |

| Racial/ethnic minorities are disproportionately impacted by financial pressures | “And the issue of that, I think is important to consider her in that as well because you can get funding for PhDs much more easily than for Masters. And so, coming from a disadvantaged background, not having family members who are likely to help her pay for her Masters, I think is scaring her away from some of the high, the more prestigious and overpriced Masters programs.” Mentor 115 |

| Systemic racism and discrimination | “and all of that is compounded if at every turn you’re facing a system that is not set up for you, right? Implicit bias and, you know, explicit problems.” Mentor 116 |

| Lack of social capital | “Resources. That’s one of the biggest things, resources. Not just in the sense of financial resources, just the manpower, the connections to get there. How do you figure it out? How do you get people interested in taking a look at people in rural and small towns like mine? That’s one of the biggest things is like we exist but it’s kind of hard for other people to see that we exist because we’re not right in front of them.” Scholar 109 |

| Lack of research infrastructure in HBCU or MSI | “One of the gaps that at least we’ve seen is that there are a number of institutions across the country at which if you don’t have access to research that would give you a sense of whether it’s something you like... And so I think in particular for underrepresented students at HBCUs or minority-serving institutions, these are examples of schools that have this type of gap in their student experience.” Program Leadership 123 |

| Pay disparities for Infectious Disease compared to other specialties/ cost of education debt in combination with potential earnings | |

| Facilitators to sustaining efforts of diversifying the field of HIV/AIDS | |

| Changing CFAR’s reach to include early access to mentored research experiences to trainees below the faculty level | “I think the things that will facilitate it or the fact that… one of [the CFAR’s] prior responsibilities is to identify and support and mentor the next generation of HIV scientists, but that’s traditionally been at the assistant professor of faculty level, we call early-stage investigators. But I think the thing that facilitates it across the CFAR Network is we’re using the same infrastructure to address and to create these learning opportunities, these training opportunities for scholars at a much earlier stage in their academic progression again at the high school and undergraduate and graduate levels before they get to the level of being a faculty member.” Program Leadership 126 |

| Building meaningful connections with Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Minority Serving Institutions | “One is to have a presence. You have to go there. Two is that it needs to be sustained.” Program Leadership 124 |

| Sustained faculty engagement | “you need faculty who are going to make sure that program, institutional knowledge, the feedback we get from the evaluations every year is taken into account, implemented and used for positive reinforcement changes within the program.” Program Leadership 124 |

| Sustained CDEIPI funding | “But the bottom line is we’re capped at the number of scholars we have, because that’s how much money they gave us through the supplements... So finding other funding mechanisms that allow us to bring in more students with this interest I think is what we need.” Program Leadership 124 |

Financial stressors

Financial barriers were identified by interview participants from all three participant categories. An organizational leader participant reported that economic resources are limited for URM trainees, which may negatively impact their pursuit of higher education. They cited competitiveness in applying to doctoral programs leading students to pursue master’s programs or otherwise gain primary research experience prior to applying as a barrier that may disproportionately impede URM trainees. URM trainees disproportionately access financial aid services starting in undergraduate training, demonstrating that financial stressors are present long before graduate and professional school18. Scholars reported that economic barriers to their success, such as application fees, finding employment while in school, or poor understanding of educational pathways, translated to a lack of drive in pursuing a career in academia. They also reported mental burden, lack of self-confidence, and anxiety associated with these financial stressors. In addition, income disparities for ID specialists compared to other fields were perceived as a deterrent19, particularly given the debt and opportunity costs associated with higher education. Strategies to counteract these economic barriers were raised by mentors who suggested having long-term cohesive or transitional training programs to better equip students for multi-stage training paths.

Experience and Social Capital Among URM Trainees

Research experience and social capital were highlighted as essential for success in academic research environments, but not always available to URM trainees. Program leadership commented that engagement in research and generation of professional networks at an early stage could favorably impact URM trainees. Therefore, increasing URM students’ self-efficacy and technical toolkit could prepare them to better navigate the barriers they will inevitably encounter. Leadership reported that training mentors on how to increase mentee self-efficacy would be essential to accomplish this goal. They also reflected on the fact that prior efforts to improve experience and social capital have focused early-stage investigators, much later stages than those targeted by the CFAR Scholars Program. This program uses “the same infrastructure to address and to create these learning opportunities for scholars at a much earlier stage in their academic before they get to the level of being a faculty member”, which was thought to be innovative. Notably, interview guides did not specifically inquire about lack of social capital, but this theme emerged from the interviews.

Research Infrastructure at HBCUs or MSIs

Organizational leadership reported that access to research infrastructure at HBCUs or MSIs posed a barrier to diversifying the field. Further, it was highlighted that faculty from HBCUs or MSIs often have limited protected research time, which translates in a gap in research experiences for undergraduate students. Therefore, creating scientific connections with HBCUs is essential to confer research experiences to young URM trainees. Reported examples included finding overlap of research interests, giving HBCU faculty an opportunity to conduct research at CDIEPI institutions, or increasing a physical presence of more research-oriented institutions on HBCU campuses.

Systemic Racism and Discrimination

Other barriers for URM students were discussed within the context of systemic racism and discrimination. According to mentors, racism and discrimination at the interpersonal and institutional levels create additional barriers to URM students’ academic success. They reported that these experiences were compounded by other barriers, like financial ones discussed above. Some scholars reported a sense of isolation as they did not know the social norms around networking for their career advancement. In particular, they did not know when and to whom they should reach out to if they intend to apply to graduate school. Organizational leaders noted the lack of URM faculty in academia and the lack of mentors for URM students as resulting factors from systemic racism and discrimination.

4.C. Interview Themes: Program Sustainability

Interview responses emphasized the importance of steady funding in maintaining programs like those that are part of the CDEIPI. Ongoing faculty engagement was raised as critical for sustainability, including faculty leading CDEIPI programs and mentors, who often require additional training and support for time management to mitigate mentor burnout. Finally, it was noted that robust evaluation to demonstrate the short, medium, and long-term impact of the program will be needed.

4.D. Academic and Professional Outcomes

Beyond subjective evaluation reported during the qualitative interviews, we have already observed favorable outcomes among our trainees. Three scholars have been accepted into PhD programs for matriculation in Summer 2023 and one scholar matched into residency. Summer projects were presented at conferences such as ID Week 2022 and the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minoritized Scientists 2022. One scholar was awarded a Goldwater Scholarship for a proposal based on their summer project investigating mRNA delivery of anti-HIV immunotherapy. Internally, a subset of scholars presented their research to the Penn ID Division Grand Rounds, while another group presented at a campus-wide poster session. To strengthen ties between affiliate institutions, two scholars attended and judged a science fair at Lincoln University. Finally, one participant received a Youth Leader Award from the Penn CFAR Community Advisory Board.

Discussion

In the year the Penn CFAR Scholars Program has existed, we have been able to swiftly establish a robust and growing mentored training program by leveraging existing clinical and lab-based research programs. We also established an innovative HIV curriculum that introduced scholars of diverse educational background to complex HIV concepts while supplying a community and historical perspective. Our program evaluation shows that scholars acquired skills that will impact their nascent career development. Further, scholars were exposed to a new field and gained career path clarity. Overall, they were able to establish relationships with their mentors and grow their social networks.

Our program evaluation also helped us identify existing challenges and areas of improvement. For instance, some trainees will not thrive in a research environment where a supervisor is not clearly defined. In addition, the expectations for longitudinal mentoring must be established. Despite this, half of our scholars will be returning in Summer 2023, which will offer opportunity to strengthen mentoring relationships. Finally, mentors volunteer their time and effort because they value the CDEIPI mission; however, our program as currently structured does not provide protection or reimbursement for their time. In the future, we plan to perform an assessment of skills at the start of the program to provide anticipatory guidance and resources to mentors and mentees. Future iterations of our program and others will need to account for broader barriers to URM trainee engagement in higher education ranging from financial stressors to systemic racism. Finally, financial and personnel commitments will be necessary to maintain and grow these programs that aim to address disparities within the HIV/AIDS academic and healthcare workforce.

Funding/Acknowledgments:

EFK is supported by the Combined Adult and Pediatric Infectious Disease Postdoctoral Training Grant T32 AI118684-05 and BEAT-HIV Delaney Collaboratory UM1 AI164570. The Penn CFAR Scholars Program and its affiliates are supported by: CDEIPI (5P30AI045008), CDEIPI was funded by the NIH through a supplemental award to the District of Columbia Center for AIDS Research (P30AI117970), The Division of Infectious Diseases of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, the Division of Infectious Diseases at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Summer Undergraduate Internship Program, Post-Baccalaureate Research Education Program (PrEP, R25GM071745, PI: KJS), Penn Access Summer Scholars (PASS, R25HL0084665), the Penn CFAR, the Perelman School of Medicine, and the Penn Institute for RNA Innovation. In particular, we would like to thank the following people for their financial and logistical support of the CFAR Scholars Program: Ronald Collman, Ebbing Lautenbach, Audrey Odom John, Horace Delisser, Drew Weissman, Donita Brady, Helen Koenig, Angela Desmond, Coralee Del Valle Mojica, Amy Onorato, Hervette Nkwihoreze, Matthew Joy, Jennifer Kogan, and William Carter. We would like to thank our volunteer research mentors and guest lecturers, who offered their time freely to support the mission of this program. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30MH097488.

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant financial conflicts of interest to report. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References:

- 1.Salsberg E, Richwine C, Westergaard S, et al. Estimation and Comparison of Current and Future Racial/Ethnic Representation in the US Health Care Workforce. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e213789. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcelin JR, Manne-Goehler J, Silver JK. Supporting Inclusion, Diversity, Access, and Equity in the Infectious Disease Workforce. The J Infect Dis. 2019;220(Supplement_2):S50–S61. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris DB, Gruppuso PA, McGee HA, Murillo AL, Grover A, Adashi EY. Diversity of the National Medical Student Body — Four Decades of Inequities. New Engl J Med. 2021;384(17):1661–1668. doi: 10.1056/nejmsr2028487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bompolaki D, Pokala SV, Koka S. Gender diversity and senior leadership in academic dentistry: Female representation at the dean position in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2022;86(4):401–405. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdhary M, Chowdhary A, Royce TJ, et al. Women’s Representation in Leadership Positions in Academic Medical Oncology, Radiation Oncology, and Surgical Oncology Programs. Jama Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e200708. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adetoye M, Gold K. Race and Gender Disparities Among Leadership in Academic Family Medicine. J Am Board Fam Medicine Jabfm. Published online 2022. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2022.ap.220122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones G, Dhawan N, Chowdhary A, et al. Gender and racial/ethnic disparities in academic oncology leadership. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15_suppl):11009–11009. doi: 10.1200/jco.2021.39.15_suppl.11009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CY, Kahanamoku SS, Tripati A, et al. Systemic racial disparities in funding rates at the National Science Foundation. Elife. 2022;11:e83071. doi: 10.7554/elife.83071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taffe MA, Gilpin NW. Racial inequity in grant funding from the US National Institutes of Health. Elife. 2021;10:e65697. doi: 10.7554/elife.65697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NIH. Racial Disparities in NIH Funding`. Published June 7, 2023. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://diversity.nih.gov/building-evidence/racial-disparities-nih-funding

- 11.Collins FS, Adams AB, Aklin C, et al. Affirming NIH’s commitment to addressing structural racism in the biomedical research enterprise. Cell. 2021;184(12):3075–3079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiser J, Beer L, West BT, Duke CC, Gremel GW, Skarbinski J. Qualifications, Demographics, Satisfaction, and Future Capacity of the HIV Care Provider Workforce in the United States, 2013–2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(7):966–975. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts C, Creamer E, Boone CA, Young AT, Magnus M. Short Communication: Population Representation in HIV Cure Research: A Review of Diversity Within HIV Cure Studies Based in the United States. Aids Res Hum Retrov. 2022;38(8):631–644. doi: 10.1089/aid.2021.0127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health NI of. Populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce. Published online May 27, 2022. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://diversity.nih.gov/about-us/population-underrepresented

- 15.Education SCD of. Logic Model Templates. Accessed April 2, 2023. https://ed.sc.gov/finance/grants/scde-grants-program/program-planning-tools-templates-and-samples/logic-model-templates/

- 16.Walker D, Myrick F. Grounded Theory: An Exploration of Process and Procedure. Qual Heal Res. 2006;16(4):547–559. doi: 10.1177/1049732305285972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook Development for Team-Based Qualitative Analysis. Field Methods. 1998;10(2):31–36. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistics NC for E. Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups. Accessed March 30, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_rec.asp

- 19.Helou GE, Vittor A, Mushtaq A, Schain D. Infectious diseases compensation in the USA: the relative value. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(8):1106–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(22)00360-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnus M, Segarra L, Robinson B, Blankenship K, Corneli A, Ghebremichael M, Irvin N, McIntosh R, Favor KE, Jordan-Sciutto KL, Kimberly J, Sluis-Cremer N, Koethe JR, Newell A, Wood C, Aadia Rana A, Stockman JK, Sauceda J,Marquez C, Chi BH, Orellana ER, Wutoh A, Bowleg L, and Greenberg AE. Impact of a Multi-Institutional Initiative to Engage Students and Early-Stage Scholars from Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups in HIV Research: The Centers for AIDS Research (CFAR) Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Pathway Initiative (CDEIPI) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]