Abstract

Problem:

This COVID-19 outpatient randomized controlled trials (RCTs) systematic review compares hospitalization outcomes amongst four treatment classes over pandemic period, geography, variants and vaccine status.

Methods:

Outpatient RCTs with hospitalization endpoint were identified in Pubmed searches through May 2023, excluding RCTs < 30 participants (PROSPERO-CRD42022369181). Risk of bias was extracted from COVID-19-NMA, with odds ratio utilized for pooled comparison.

Results:

Searches identified 281 studies with 61 published RCTs for 33 diverse interventions analyzed. RCTs were largely unvaccinated cohorts with at least one COVID-19 hospitalization risk factor. Grouping by class, monoclonal antibodies (OR=0.31 [95% CI=0.24–0.40]) had highest hospital reduction efficacy, followed by COVID-19 convalescent plasma (CCP) (OR=0.69 [95% CI=0.53 to 0.90]), small molecule antivirals (OR=0.78 [95% CI=0.48–1.33]) and repurposed drugs (OR=0.82 [95% CI- 0.72–0.93]). Earlier in disease onset interventions performed better than later. This meta-analysis allows approximate head-to-head comparisons of diverse outpatient interventions.

Conclusions:

Omicron sublineages (XBB and BQ.1.1) are resistant to monoclonal antibodies. Despite trial heterogeneity, this pooled comparison by intervention class indicated oral antivirals are the preferred outpatient treatment where available, but intravenous interventions from convalescent plasma to remdesivir are also effective and necessary in constrained medical resource settings or for acute and chronic COVID-19 in the immunocompromised.

Keywords: small molecule antivirals, convalescent plasma, monoclonal antibody, COVID-19, outpatients, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

By May 17, 2023 the world had recorded over 766 million cases and more than 6.9 million deaths from COVID-19. In the US, some 100 million cases have been recorded, with over a million deaths, while six million hospital admissions for COVID took place between August 2020 and December 2022. A pronounced spike in hospitalizations for COVID-19 in the US took place in the first two months of 2022 with the arrival of the Omicron variant of concern (VOC).

Several approaches to reducing the risk of hospitalization have been taken during the pandemic, including administering COVID-19 convalescent plasma (CCP), monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), small molecule antivirals or repurposed drugs. Vaccination and boosters have substantially reduced the hospitalization and death risk, but outpatients at elevated severe COVID risk can still benefit from early treatment to avoid hospitalization. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in outpatients have tested therapeutic agents against placebo or standard of care, but very few RCTs has been conducted that compare the main outpatient treatment classes.

The first outpatient treatments for COVID-19 authorized by the FDA were for mAbs (bamlanivimab, bamlanivimab plus etesevimab1 or casirivimab plus imdevimab2), approvals that preceded the introduction of mRNA vaccines3,4. While many small molecules were repurposed as antivirals during the early stages of the pandemic, oral antivirals developed against SARS-CoV-2 for outpatients were not authorized and available until December 2021, when nirmatrelvir/ritonavir5 and molnupiravir6 were approved. The following month, intravenous remdesivir was also approved for outpatient use7. On December 2021, nearly two years after the first use of CCP, the FDA approved CCP outpatient use, but only for immunocompromised patients8,9. The mAbs have been withdrawn due to viral variants BQ.1.* and XBB.* resistance.

The rationale of the study was to assemble in one place all outpatient COVID-19 RCT in the four classes to compare hospitalization outcomes over time, geography in relationship to variants and vaccine status. We were inclusive of smaller studies meeting criteria of RCT with endpoint hospitalization. This systematic review and meta-analysis of outpatient COVID-19 RCTs, sought to compare hospitalization outcomes amongst CCP, mAbs, antivirals or repurposed drugs as grouped classes and individual trials taking into account risk factors for progression, intervention dosage, time between symptom onset and treatment administration, and predominant variants of concern during the RCTs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Registration

The protocol has been registered in PROSPERO, the prospective register of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the University of York (protocol registration number CRD42022369181).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Data Extraction

We included outpatient COVID-19 RCTs with outcome hospitalization or a single CCP study with life-threatening respiratory distress10, by searching MEDLINE (through PubMed), medRxiv and bioRxiv databases for the period of March 1, 2020 to May 22, 2023, with English language as the only restriction. The Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) and search query used were: “(“COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “coronavirus disease 2019”) AND (“treatment” OR “therapy”) AND (“outpatient”) AND (“hospitalization”)” AND (“randomized clinical trial”). We also screened the reference list of reviewed articles for studies not captured in our initial search. We excluded case reports, case series, retrospective, propensity-matched studies, non-randomized clinical trials, review articles, meta-analyses, guidelines, studies with fewer than 30 participants, studies that did not record or had no hospitalizations, protocol only publications and articles reporting only aggregate data. Trials of COVID prevention11 were excluded, even if hospitalizations were recorded. Inclusion and exclusion reasons are summarized for the 281 citations in Appendix table 1. Articles underwent a blind evaluation for inclusion by two assessors (D.S. and D.F.) and disagreements were resolved by a third senior assessor (A.C.). Figure 1 shows a PRISMA flowchart of the literature reviewing process. The following parameters were extracted by at least one reviewer from studies: baseline SARS-CoV-2 serology status, time from onset of symptoms to treatment, study dates, recruiting countries, gender, age (including the fraction of participants over age 50, 60 and 65), ethnicity, risk factors for COVID-19 progression (systemic arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity), sample size, dosage type of control, hospitalizations and deaths in each arm, and time to symptom resolution (Appendix Table 2). Study dates were used to infer predominant VOCs. The studies were grouped into classes by CCP, mAbs, antivirals or repurposed drugs.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for randomized controlled trials (RCT) selection in this systematic review.

** All excluded by a human

2.3. Assessment of Risk of Bias and GRADE Assessment

A risk of bias assessment of each selected RCT was performed by COVID-19-NMA initiative12,13. Within-trial risk of bias was assessed, using the Cochrane ROB tool for RCTs14. We explored clinical heterogeneity (e.g., risk factors for progression, time between onset of symptoms and treatment administration, and predominant variants of concern at the time of the interventions) and calculated statistical heterogeneity using τ2, Cochran’s Q and estimated this using the I2 statistic, which examines the total variation percentage across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance. Each study was evaluated by at least two reviewers.

We used the GRADE (The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system criteria to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with specific outcomes, and constructed a ‘Summary of Findings’ table (Appendix Table 3), which defines the certainty of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest14. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis included time-to-treatment, geography (country) of the study, age, sex, race, ethnicity, seropositive, hospital type and medical high-risk conditions. The unweighted pooling ARR, RRR, NNT were calculated based on the arithmetic summation of the total hospitalization or death numbers in each therapeutic category.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to show the direction of effect and its significance in comparing treatment group and control groups. The studies were weighted with the Mantel-Haenszel method. The effect heterogeneity was calculated estimating the I-squared (I2) inconsistency index. If significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 > 50% and Cochran’s Q test for heterogeneity was significant (p < 0.10)), a random effect model was performed; otherwise, a fixed (common) effect model was performed. Weight, heterogeneity, between-study variance, and significance level were displayed in forest plots. Robustness of hospital risk reduction utilized a leave the highest enrollment study out. The significance level was 0.05. The figures were created in Prism software, R (version 4.2.1) and its statistical package “meta” (version 6.0–0). All the data manipulation and the analyses were performed in Excel, Prism, MedCalc (version 20.106), R and REVMAN.5.

2.5. Role of the Funding Source

The study sponsors did not contribute to the study design; to the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; to manuscript preparation, nor to the decision to submit the paper for publication.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Trial Characteristics

We reviewed in detail 61 distinct outpatient RCT publications for 70 trial arms including 33 different interventions, concluded before May 22, 2023, across waves sustained by different SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOC) and different vaccination periods in diverse patient populations (Figure 2). The studies varied in reporting outcomes of hospitalization, whether all-cause or COVID-19 related (Appendix Table 2). The CCP group included 3 RCTs with all-cause hospitalization, 2 trials with COVID-19 related hospitalizations only and one trial with life-threatening respiratory distress in elderly individuals, deemed equivalent to hospital outcome (Appendix Table 2). The mAb RCTs included 4 trials with all-cause hospitalizations and 5 that used COVID-19 related hospitalizations as the outcome. The small molecule antivirals had 12 RCTs with all-cause hospitalizations and 5 with COVID-19 related hospitalizations, while 29 RCT’s of repurposed drugs used all-cause hospitalizations and 10 trials restricted to COVID-19 related hospitalizations. Here we report the hospitalizations as a composite of the two hospital types. Because inclusion criteria varied across the RCTs, control group hospitalization rates varied from 0 to 31% with a mean of 1.6% (Table 1). Three of five CCP RCTs had higher control arm hospitalization rates (11% – 31%) than all other antiviral RCTs, indicating that they studied sicker populations.9 (Table 1 and Figure 3). Seven of nine mAb RCTs had control arm hospitalization rates of 4.6–8.9%, the same range as CCP-CSSC-004 (6.3%)9. Control hospitalization rates in the molnupiravir-MOVE-OUT7, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir5 and remdesivir15 RCTs ranged from 5.3% to 9.7%. Low hospitalization rates were found in RCTs that had many vaccinees (metformin-COVID-OUT – 3.2%16) or in which most participants were seropositive (molnupiravir-PANORAMIC – 0.8%). Low control arm hospitalization rates were also found in two mAb RCTs – the bebtelovimab trial (1.6%)17 and REGN-CoV phase 1/2 (<2%), with the bebtelovimab RCT focusing on low-risk patients 17. Lower control hospitalization rates reduce power to detect absolute risk ratios.

Figure 2.

Duration and calendar months of the RCT in context of dominant variant(s) of concern and seropositivity rates. Study start and end for enrollments are charted with approximate time periods for variants of concern.

Table 1.

Hospital rates, risk reductions, NNT, numbers and symptom resolution

| Study | Control hospitalizations % | hospitalizations % in intervention arm | ARR percent (95% CI) | RRR percent (95% CI) | NNT to prevent 1 hospitalization | Hospitalization (n) in control arm | total pts in control arm (n) | Hospitalization (n) in intervention arm | Total pts (n) in intervention arm | Symptom resolution: median duration-Intervention to control in days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCP (5 RCT) % or totals | 12 | 8.8 | 3.2 (0.9, 5.6) | 26.8 (8.1, 41.7) | 31 | 158 | 1315 | 116 | 1319 | ||

| anti-Spike mAbs (8 RCT) % or totals | 5.9 | 1.9 | 4.0 (3.2, 4.8) | 67.8 (59.1, 74.7) | 25 | 242 | 4102 | 88 | 4634 | ||

| Small molecule antiviral (11 RCTs) total or average | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 29.1 (15.9, 40.2) | 187 | 314 | 17079 | 222 | 17025 | ||

| Small molecule antiviral (10 RCTs-w/o Mol-Pan.) total or average | 4.7 | 2.6 | 2.1 (1.3, 2.9) | 44.4 (30.7, 55.3) | 48 | 218 | 4595 | 119 | 4509 | ||

| Repurposed drugs (20 RCTs) total or average | 5.3 | 4.2 | 1.1 (0.5, 1.6) | 20.1 (10.1, 28.9) | 94 | 590 | 11121 | 483 | 11391 | ||

| All (47 RCTs) total or average | 3.9 | 2.6 | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) | 31.8 (25.9, 37.3) | 81 | 1304 | 33617 | 909 | 34369 | ||

| CCP-CONV-ert24 | 11.2 | 11.7 | −0.5 (−7.0, 5.9) | −4.8 (−83.9, 40.3) | −188 | 21 | 188 | 22 | 188 | NO difference 12 d vs 12 d | |

| CCP-COV-Early35 | 9.3 | 5.9 | 3.4 (−1.8, 8.5) | 36.2 (−27.9, 68.2) | 29 | 19 | 204 | 12 | 202 | NO difference 13 d vs 12 d | |

| CCP-C3PO36 | 22.0 | 20.2 | 1.8 (−5.3, 8.9) | 8.2 (−28.3, 34.4) | 55 | 56 | 254 | 52 | 257 | NO difference | |

| CCP-Argentina10 | 31.3 | 16.3 | 15.0 (2.0, 28.0) | 48.0 (5.8, 71.3) | 7 | 25 | 80 | 13 | 80 | Not reported | |

| CCP-CSSC-0049 | 6.3 | 2.9 | 3.4 (1.0, 5.8) | 54.3 (19.7, 74.0) | 29 | 37 | 589 | 17 | 592 | Not reported | |

| CCP-Argentina (high titer)10 | 31.3 | 8.3 | 22.9 (9.3, 36.5) | 73.3 (17.4, 91.4) | 4 | 25 | 80 | 3 | 36 | Not reported | |

| CCP-CSSC-004 (<= 5 days) 9 | 9.7 | 1.9 | 7.7 (3.7, 11.7) | 79.9 (48.4, 92.2) | 13 | 25 | 259 | 5 | 257 | Not reported | |

| Bamlanivimab-BLAZE-11 | 6.3 | 1.6 | 4.7 (0.5, 8.9) | 74.3 (24.7, 91.2) | 21 | 9 | 143 | 5 | 309 | NO difference 11 d to 11 d | |

| Sotrovimab-COMET-ICE37 | 5.7 | 1.1 | 4.5 (2.4, 6.7) | 80.0 (52.3, 91.6) | 22 | 30 | 529 | 6 | 528 | Not reported | |

| Bamlanivimab/etesevimab-BLAZE-125 | 7.0 | 2.1 | 4.8 (2.3, 7.4) | 69.5 (40.8, 84.3) | 21 | 36 | 517 | 11 | 518 | YES-8d vs 9d p=0.007 | |

| Casirivimab/imdevimab-REGEN-COV Ph 32 | 4.6 | 1.3 | 3.3 (2.0, 4.6) | 71.3 (51.7, 82.9) | 30 | 62 | 1341 | 18 | 1355 | YES-10 d vs 14 p=0.0001 | |

| Casirivimab/imdevimab-REGEN-COV Ph 1/238 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 1.3 (−0.4, 3.1) | 70.1 (−24.4, 92.8) | 76 | 5 | 266 | 3 | 533 | Not reported | |

| Bebtelovimab-BLAZE-417 | 1.6 | 1.6 | −0.04 (−3.1, 3.0) | −2.4 (−615.7, 85.4) | −2667 | 2 | 128 | 2 | 125 | YES-6d to 8d p=0.003 | |

| Regdanvimab-CT-P5926 | 8.7 | 4.4 | 4.2 (−1.9, 10.3) | 48.8 (−25.2, 79.0) | 23 | 9 | 104 | 9 | 203 | YES 6 d vs 9 d p=0.01 | |

| Regdanvimab-CT-P59–227 |

7.9 | 2.4 | 5.4 (3.1, 7.8) | 69.1 (46.4, 82.2) | 18 | 52 | 659 | 16 | 656 | 8 d to 13 d | |

| Tixagevimab–cilgavimab-TACKLE39 | 8.9 | 4.4 | 4.5 (1.1, 7.9) | 50.4 (14.3, 71.3) | 22 | 37 | 415 | 18 | 407 | Not reported | |

| Molnupiravir-MOVe-OUT6 | 9.7 | 6.8 | 3.0 (0.1, 5.8) | 30.4 (0.8, 51.2) | 34 | 68 | 699 | 48 | 709 | NO difference | |

| Molnupiravir-PANORAMIC40 | 0.8 | 0.8 | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.2) | −7.0 (−41.2, 18.9) | −1853 | 96 | 12484 | 103 | 12516 | YES 9 d vs 15 d | |

| Molnupiravir-Aurobindo41 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NC | NC | 0 | 0 | 610 | 0 | 610 | Yes 10 d vs 14 d p<0.001 | |

| Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir-EPIC-HR5 | 6.3 | 0.8 | 5.5 (4.0, 7.1) | 87.8 (74.7, 94.1) | 18 | 66 | 1046 | 8 | 1039 | Not reported | |

| Remdesivir-PINETREE15 | 5.3 | 0.7 | 4.6 (1.8, 7.4) | 86.5 (41.4, 96.9) | 22 | 15 | 283 | 2 | 279 | YES-Alleviation of symptoms by day 14 (rate ratio, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.26 to 2.94) | |

| Interferon Lambda-TOGETHER42 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 1.7 (0.1, 3.2) | 42.6 (3.4, 65.9) | 60 | 40 | 1018 | 21 | 931 | ||

| Interferon Lambda-ILIAD43 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0 (−9.1, 9.1) | 0 (−1426, 93.4) | 1 | 30 | 1 | 30 | No difference | ||

| Interferon Lambda-COVID-Lambda44 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0 (−6.4, 6.4) | 0 (−586.9, 85.4) | 2 | 60 | 2 | 60 | NO difference 20 d vs 20 d | ||

| Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir-SOVODAK45 | 14.3 | 3.7 | 10.6 (−4.2, 25.4) | 74.1 (−117, 96.9) | 9 | 4 | 28 | 1 | 27 | NO difference in 7 d symptoms | |

| Favipavir-Avi-Mild-1946 | 1.7 | 5.4 | −3.7 (−8.4, 1.1) | −219 (−1447, 34.3) | −27 | 2 | 119 | 6 | 112 | NO difference 7d vs 7d | |

| Favipiravir-Iran47 | 5.1 | 10.5 | −5.4 (−17.4, 6.6) | −105.3 (−955.6, 60.1) | −19 | 2 | 39 | 4 | 38 | ||

| Favipiravir-FLARE48 | 0.0 | 1.7 | −1.7 (−5.0, 1.6) | NA | −59 | 0 | 60 | 1 | 59 | ||

| Favipiravir/Lopinavir/Ritonavir-FLARE48 | 0.0 | 1.6 | −1.6 (−4.8, 1.5) | NA | −61 | 0 | 60 | 1 | 61 | ||

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir-FLARE48 | 0.0 | 1.7 | −1.7 (−5.0, 1.6) | NA | −60 | 0 | 60 | 1 | 60 | ||

| Lopinavir/ritonavir-TREAT NOW49 | 2.7 | 3.2 | −0.5 (−3.7, 2.6) | −19.8 (−251, 59.1) | −190 | 6 | 226 | 7 | 220 | 6 d to 6 d | |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir-TOGETHER18 | 4.8 | 5.7 | −0.9 (−4.9, 3.1) | −18.4 (−155.4, 45.1) | −112 | 11 | 227 | 14 | 244 | NO difference by Cox proportional HR | |

| Tenofovir Disproxil Fumarate Plus Emtricitabine-AR0-CORONA50 |

3.3 | 6.7 | −3.3 (−14.3, 7.7) | −100 (−1989.8, 80.9) | −30 | 1 | 30 | 2 | 30 | ||

| Metformin-COVID-OUT16 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 1.8 (0.1, 3.5) | 57.5 (3.8, 81.3) | 55 | 19 | 601 | 8 | 596 | NO difference | |

| Metformin-TOGETHER51 |

11.8 | 11.2 | 0.7 (−5.5, 6.8) | 5.6 (−60.8, 44.6) | 152 | 24 | 203 | 24 | 215 | not reported | |

| Fluvoxamine-TOGETHER21 | 12.8 | 10.1 | 2.7 (−0.5, 5.9) | 21.1 (−4.8, 40.6) | 37 | 97 | 756 | 75 | 741 | NO difference-40% resolved by day 14 | |

| Fluvoxamine-STOP COVID52 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 8.3 (1.9, 14.7) | 1 (1, 1) | 12 | 6 | 72 | 0 | 80 | YES (100% vs 91.7% resolved on day 7) p=0.009 | |

| Fluvoxamine-COVID-OUT16 | 1.7 | 2.0 | −0.3 (−2.5, 1.9) | −17.6 (−281, 63.7) | −333 | 5 | 293 | 6 | 299 | No difference (14 symptoms on 4 pt scale over 14 days) | |

| Fluvoxamine ACTIV-653 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.18 (−0.4, 0.7) | 54.7 (−398.3, 95.9) | 555 | 2 | 607 | 1 | 670 | 12 d to 13 d | |

| Fluvoxamine/budesonide-TOGETHER54 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.1 (−0.9, 1.1) | 12.5 (−140.1, 68.1) | 738 | 8 | 738 | 7 | 738 | not reported | |

| Ivermectin-TOGETHER55 | 14.0 | 11.6 | 2.4 (−1.2, 5.9) | 16.8 (−9.9, 37.1) | 42 | 95 | 679 | 79 | 679 | NO difference-40% resolved by day 14 | |

| Ivermectin-COVID-OUT16 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.3 (−1.3, 1.9) | 23.9 (−181, 79.4) | 299 | 5 | 356 | 4 | 374 | No difference (14 symptoms on 4 pt scale over 14 days | |

| Ivermectin Iran56 | 5.0 | 7.1 | −2.1 (−6.1, 1.9) | −42.3 (−178, 27.2) | −47 | 14 | 281 | 19 | 268 | NO difference | |

| Ivermectin-ACTIV-657 | 1.2 | 1.2 | −0.1 (−1.1, 1.0) | −5.3 (−158, 57.0) | −1634 | 9 | 774 | 10 | 817 | No difference (12d vs 13 d) | |

| Ivermectin high dose-ACTIV-658 |

0.3 | 0.8 | −0.5 (−1.4, 0.4) | −150.1 (−1188, 51.1) | −200 | 2 | 604 | 5 | 602 | 11 d vs 11 d no difference | |

| Hydroxychloroquine-TOGETHER18 | 4.8 | 3.7 | 1.1 (−2.7, 4.9) | 22.9 (−88.1, 68.4) | 90 | 11 | 227 | 8 | 214 | NO difference by Cox proportional HR | |

| Hydroxychloroquine-COVID-19 PEP59 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 2.4 (−1.1, 5.9) | 50.2 (−43.1, 82.7) | 42 | 10 | 211 | 5 | 212 | NO Difference in symptom severity score over 14 days | |

| Hydroxychloroquine-AH COVID-1960 | 0.0 | 3.6 | −3.6 (−7.1, −0.1) | NA | −28 | 0 | 37 | 4 | 111 | NO difference 14 d vs 12 d | |

| Hydroxychloroquine-BCN PEP-CoV-261 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 1.1 (−4.5, 6.7) | 16.0 (−103, 65.2) | 89 | 11 | 157 | 8 | 136 | NO difference 10 d vs 12 d | |

| Hydroxychloroquine-BMG62 | 4.8 | 3.4 | 1.4 (−4.0, 6.9) | 29.9 (−154, 80.6) | 69 | 4 | 83 | 5 | 148 | NO difference 11 d vs 12 d | |

| Hydroxychloroquine-Utah63 | 2.6 | 4.6 | −2.0 (−6.2, 2.2) | −73.8 (−481.6, 48.0) | −51 | 4 | 151 | 7 | 152 | 6 d to 6 d | |

| Hydroxychloroquine/Azithromycin-Brazil64 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0 (−6.5, 6.5) | 0 (−1447, 93.5) | 100 | 1 | 42 | 1 | 42 | ||

| Nitazoxanide-Romark22 | 2.6 | 0.5 | 2.0 (−0.4, 4.5) | 78.8 (−79.7, 97.5) | 49 | 5 | 195 | 1 | 184 | Yes mild illness (13 d vs 18 d, p=0.01), NO difference for moderate illness | |

| Colchicine-COLCORONA20 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 1.2 (−0.1, 2.5) | 20.0 (−2.8, 37.7) | 86 | 131 | 2253 | 104 | 2235 | Not reported | |

| Losartan-MN65 |

1.7 | 5.2 | −3.5 (−10.1, 3.1) | −205 (−2749, 67.3) | −29 | 1 | 59 | 3 | 58 | ||

| Niclosamide66 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 2.9 (−2.7, 8.6) | 1 (1, 1) | 34 | 1 | 34 | 0 | 33 | NO difference 12 d vs 15 d | |

| Aspirin-ACTIV-4B67 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.04 (−1.9, 2.0) | 5.6 (−1395, 94) | 2448 | 1 | 136 | 1 | 144 | Not reported | |

| 2.5-mg apixaban-ACTIV-4B67 | 0.7 | 0.7 | −0.01 (−2.0, 2.0) | −0.7 (−1494, 93.6) | −18360 | 1 | 136 | 1 | 135 | Not reported | |

| 5-mg apixaban ACTIV-4B67 | 0.7 | 1.4 | −0.7 (−3.1, 1.7) | −90.2 (−1974, 82.6) | −151 | 1 | 136 | 2 | 143 | Not reported | |

| Sulodexide68 | 29.4 | 17.7 | 11.7 (1.1, 22.3) | 39.7 (3.5, 62.3) | 9 | 35 | 119 | 22 | 124 | Not reported | |

| Enoxaparin-ETHIC69 | 10.5 | 11.4 | −0.9 (−9.2, 7.4) | −8.6 (−131, 49.0) | −111 | 12 | 114 | 12 | 105 | Not reported | |

| Enoxaparin-OVID70 | 3.4 | 3.4 | −0.1 (−3.3, 3.2) | −1.7 (−166, 61.2) | −1740 | 8 | 238 | 8 | 234 | Not reported | |

| Inhaled Ciclesonide-COVIS71 |

3.4 | 1.7 | 1.8 (−1.4, 4.9) | 51.4 (−85.2, 87.2) | 56 | 7 | 203 | 3 | 179 | 19 d to 19 d | |

| Inhaled ciclesonide-COVERAGE72 | 11.2 | 12.7 | −1.5 (−10.1, 7.1) | −13.5 (−134, 45.0) | −66 | 12 | 107 | 14 | 110 | NO difference 13 d vs 12 d | |

| Zinc73 | 6.0 | 8.6 | −2.6 (−12.4, 7.2) | −43.7 (−471.4, 63.9) | −38 | 3 | 50 | 5 | 58 | 11 dto 10 d | |

| Ascorbic acid73 | 6.0 | 4.2 | 1.8 (−6.8, 10.5) | 30.6 (−297.6, 87.9) | 55 | 3 | 50 | 2 | 48 | 12 d to 10 d | |

| Zinc/Ascorbic acid73 | 6.0 | 12.1 | −6.1 (−16.7, 4.6) | −101.1 (−637, 45.1) | −16 | 3 | 50 | 7 | 58 | 10 d too 10 d | |

| Homeopathy-COVID-Simile74 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 4.4 (−4.3, 13.2) | 65.1 (−222.6, 96.2) | 23 | 3 | 44 | 1 | 42 | ||

| Saliravira75 | 28.6 | 0.0 | 28.6 (16.7, 40.4) | 1 (1, 1) | 4 | 16 | 56 | 0 | 87 | YES 9d vs 14 d p<0.05 | |

| Azithromycin-Atomic276 | 11.6 | 10.3 | 1.2 (−5.9, 8.4) | 10.5 (−72.3, 53.6) | 82 | 17 | 147 | 15 | 145 | Not reported | |

| Azithromycin-ACTION28 | 0.0 | 4.0 | −4.0 (−7.4, −0.6) | NA | −25 | 0 | 72 | 5 | 125 | No difference resolution day 14 | |

| Resveratrol77 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 (−3.6, 11.6) | 66.7 (−210, 96.4) | 25 | 3 | 50 | 1 | 50 | Not reported | |

Figure 3.

Percent hospitalizations in control groups sorted by therapy type and descending control hospitalization rates.

3.2. Trial Outcome Comparison

Examining RCTs by agent class, statistically significant relative risk reductions in hospitalization were found in two of five CCP RCTs, six of nine mAb RCTs, four of 17 small molecule antiviral RCTs, but just 2 of 39 repurposed drug RCTs (Table 1). Except for the bebtelovimab RCT (2 hospitalizations in each arm17), mAb RCTs reduced the risk of hospitalization by 50–80% (average 75%). Two of the three small molecule antiviral drugs (remdesivir15 and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir5) showed very high levels of relative risk reduction - 87% and 88% respectively - but molnupiravir reduced risk of hospitalization by only 30%7 (excluding the large no reduction seen in the PANORAMIC RCT25). The lopinavir/ritonavir combination was associated with a non-significant increase in risk of hospitalization18.

Among repurposed drug RCTs, all except metformin (58%) and sulodexide (40%), showed small and non-significant relative risk reductions of hospitalization - ivermectin19, colchicine20, fluvoxamine21 and hydroxychloroquine18. The nitazoxanide22 RCT found one hospitalization among 184 treated participants compared to five hospitalizations among 195 controls, too few events to achieve significance.

Absolute risk reductions (ARR) and number needed to treat (NNT) to avert hospitalizations varied across studies and treatment classes (Table 1). In general, except for the repurposed drugs the absolute risk difference approximated 3% if one excludes the molnupiravir-Panoramic Study from SMA. The CCP RCTs had an ARR of 3.2% (95%CI-0.9–5.6), mAbs RCTs had an ARR of 4.0% (95%CI-3.2–4.8), small molecule antivirals excluding molnupiravir-Panoramic had ARR of 2.1% (95%CI-1.3–2.9) and the repurposed drugs had a smaller ARR at 1.1% (95%CI-0.5–1.6). The number needed to treat to prevent hospitalizations approximated 30 in the trials, with a few notably low with CCP-Argentina (NNT=7) Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (NNT=18), except those using repurposed drugs, where NNT averaged 70 (Table 1).

3.3. Pooled Meta-analysis

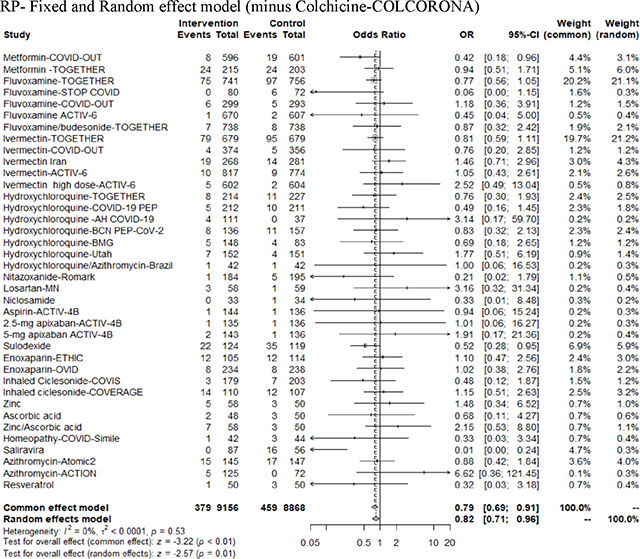

In the pooled meta-analysis by class group, the CCP RCTs had a fixed effect OR of 0.69 (95% CI=0.53 to 0.9) with moderate heterogeneity (I2=43%), the mAbs had a fixed effect OR of 0.31 (95% CI=0.24–0.40) with low heterogeneity (I2=0%), the small molecule antivirals had a random effect OR of 0.78 (95% CI=0.48–1.33) with high heterogeneity (I2=69%) and the repurposed drugs had a random effect OR of 0.82 (95% CI- 0.72–0.93) with low heterogeneity (I2=0) (Figure 4, Appendix Table 4). A biologic reason to use a fixed model for CCP and mAbs is that both formulations have the same active agent as specific antibody and thus there is a high degree of similarity in these two antibody interventions. Both antiviral small molecules and repurposed drugs comparison involve many types and classes of drugs for which the random effect model for the group is biologically more plausible than treating them as fixed. The meta-analysis of all interventions had a random effect OR of 0.67 (95% CI=0.57–0.80) with high heterogeneity (I2=52%) (Appendix Figure 2). Because regional parts of the world might have different thresholds for the hospitalization outcome we grouped by region (USA, Brazil, Europe, Midde East or World) across diverse intervention classes to indicate that the intervention class had more of an effect than region (Appendix Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Odds ratio for hospitalizations with diverse therapeutic interventions, grouped according to mechanism of action (CCP, mAbs, small molecule antivirals and repurposed drugs).

Ten RCTs compared hospitalization rates in early or late interventions (dated from symptom onset) that were extractable from the published papers or supplementary data as a post-hoc analysis (Figure 5). The small molecule drugs showed no significant reduction in the OR with segregation of early treatment from late treatment. In contrast, the antibody therapies showed a difference by treatment timing. Pooling the two classes of antibody treatment, the OR for early treatment was 0.65 (95%CI=0.49–0.85), while the OR for later treatment was 0.86 (95%CI=0.66–1.12).

Figure 5.

Odds ratio for point estimates for hospitalization in RCT subgroups treated A) within 5 days since onset of symptoms and also B) over 5 days within same trial.

A) Early treatment-Fixed and random effect model B) Late treatment-Fixed and random effect model

3.4. Robustness of the Meta-analysis

Within the CCP RCTs excluding either CCP-Argentina for the nonhospital endpoint or CONV-ERT for methylene blue inactivation of antibody function only changed the OR by 0.05 with 95% CI remaining less than 1 for the fixed effect model (Appendix Figure 4). Adding the 7 all-cause hospitalizations to CSSC-004, increased the OR by 0.02 and 95% CI by 0.01, essentially no change (Appendix Figure 4). In a leave out the largest study by participants sensitivity analysis, the OR was not significantly altered in the model effects by more than 0.1 except for SMA where removal of the large Molnupirivir-Panoramic study changed common effect model OR from 0.7 to 0.54. Both the mAb and RP did not change OR results (Appendix Figure 5).

3.5. Certainty of Evidence

All four trial classes showed reduced rates of hospitalization for each group. The final certainty of the available evidence with GRADE assessment (Appendix Table 3) showed a high certainty level within CCP trials, moderate certainty with mAbs, and low certainty with small molecule antivirals and repurposed drugs. The main reason for downgrading individual and pooled studies was imprecision, related to small number of participants and the wide confidence intervals around the effect, followed by ROB (Appendix Figure 6). We did not find concerns in any of the GRADE factors for CCP RCTs, so we graded them as high level of certainty. mAbs were downgraded to moderate certainty due to ROB (in 4 of the 8 included RCTs, ROB for the outcome hospitalization was judged of some concern). In the cumulative analysis, small molecule antivirals were downgraded to low certainty of evidence because of ROB (some/high ROB in 4 RCTs) and inconsistency (due to high heterogeneity), while repurposed drugs were downgraded to low certainty due to ROB (some/high ROB in 5 of the 11 comparisons) and indirectness (due to large difference in mechanism of action of the included drugs). The ROB was independently evaluated by the COVID-19-Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) initiative for most of the RCTs (Appendix Figure 6). Funnel plot analysis with Egger Test shows a low risk of publication bias except for the mAbs, for which either the efficacy of high dose antibodies or non-reporting bias are plausible explanations (Appendix Figure 7).

3.6. Outpatient Intervention Mortality

While several RCTs showed fewer deaths in the treatment arm, no outpatient study was powered to compare differences in mortality. Because of the low rate of deaths during trials the absolute risk reductions amongst the 4 antiviral classes are all below 1% corresponding to relative risk reductions of 20%, 81%, 87% and 22% for CCP, mAbs, small molecule antivirals or repurposed drugs, respectively (Appendix Table 5).

3.7. Time To Symptom Resolution

The two most effective CCP RCTs (Argentine10 and CSSC-0049) did not compare time to symptom resolution, while the COV-Early23 and ConV-ERT24 RCTs reported no difference in the median time of symptom resolution in the two groups24 (Table 1). The mAbs noted faster resolution by 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 days for bamlanivimab/etesevimab25, bebtelovimab17, regdanvimab26, casirivimab/imdevimab2, or redanvimab27 respectively. The smaller bamlanivimab-only RCT did not show a difference1. Of the three SMAs that noted reductions in hospitalizations, molnupiravir was associated with no difference in time of symptom resolution in MOVe-OUT7 but improvements in both PANORAMIC25 and Aurobindo27 RCTs. The 3-day outpatient remdesivir RCT showed that symptoms were alleviated by day 14 nearly twice as often15. The nirmatrelvir/ritonavir RCT did not report on this parameter5. Seven of 10 RCTs in the antiviral group did not show faster symptom resolution with intervention. The three RCTs largely performed in Brazil for fluvoxamine, ivermectin19 and hydroxychloroquine18 noted no differences in symptom resolution. Metformin did not evidence faster symptom resolution despite reducing hospitalizations. Three of the 25 RCTs reporting symptom resolution in the repurposed drug group noted faster symptom resolution.

3.8. Costs

mAbs and intravenous remdesivir schedules cost about 1000 to 2000 Euros per patient, respectively, while the oral drugs are much less than 1000 Euros per patient (Table 2). By comparison, the cost of CCP approximates 200 Euros per patient, and the cost for repurposed drugs is even lower. Considering the absolute risk reduction in hospitalization, the number needed to treat to prevent a single hospitalization is often very high, as are the associated costs. With the recently patented antivirals, costs for outpatient treatment often exceed the cost of a COVID-19 hospitalization28.

Table 2.

Summary of historical efficacy of different therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2 VOCs.

| approximate cost per patient | average NNT (sourced from Table 2) | cost to prevent a single hospitalization (€) | efficacy against VOC Alpha | efficacy against VOC Delta | efficacy against VOC BA.1 | efficacy against VOC BA.2 | efficacy against BA.4/5 | efficacy against BQ.1.1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bamlanivimab+etesesevimab | 2000 | 21 | 42,000 | restricted 04/2021 | |||||

| casirivimab+imdevimab | 2000 | 30 | 60,000 | restricted 01/2022 | |||||

| sotrovimab | 1000 | 22 | 22,000 | restricted 03/2022 | |||||

| tixagevimab+cilgavimab | 1000 | 22 | 22,000 | restricted 10/22 |

|||||

| regdanvimab | 300 | 23 | 6,900 | ||||||

| bebtelovimab | 2000 | Not calculated (low-risk pts) | Not calculated (low-risk pts) | ||||||

| nirmatrelvir | 635 (5 days) | 18 | 11,435 | ||||||

| molnupiravir | 635 (5 days)) | 34 | 21,590 | ||||||

| remdesivir | 1600 (3 days) | 22 (MOVE-Out) | 35,200 | ||||||

| CCP | 200 (600-ml) |

31 | 6,200 | ||||||

| Vax-CCP |

White = drug not available at that time; green = effective; orange = partially effective; red= not effective. Restriction reported refer to initial restrictions by FDA. NNT: number needed to treat.

3.9. Variants

mAbs successively lost efficacy against Delta and Omicron, with cilgavimab (the only Omicron-active ingredient in Evusheld™) and bebtelovimab also failing against BQ.1.1 and XBB.* sublineages (Figure 6). This has led the FDA to withdraw EUAs, while EMA has not restricted usage at all. Small molecule antivirals retain in vitro efficacy against Omicron, but concerns remain: molnupiravir showed low efficacy in vivo6 and is mutagenic for mammals in vitro29, while nirmatrelvir/ritonavir has drug/drug interaction contraindications (CYP3 metabolites especially tacrolimus, anti-cholesterol, anti-migraine or many anti-depressants) and has been associated with early virological and clinical rebounds in immunocompetent patients30. CCP from unvaccinated donors does not inhibit Omicron, but CCP from donors having any sequence of vaccination and recent, within 6 months, COVID-19 or having had boosted mRNA vaccine doses universally has high Omicron-neutralizing activity.

Figure 6.

Venn diagram of mAb efficacy against Omicron sublineages. In vitro activity of currently approved mAbs against Omicron sublineages circulating as of October 2022. Specific Omicron Spike amino acid mutations causing baseline ≥ 4-fold-reduction in neutralization against mAbs are reported. Mutations for which the majority of studies are concordant are reported: the different fold-reductions for each mAb are identified across concordant studies as color coded numbers defining the mean median values of specific reduction in each study. Sourced from https://covdb.stanford.edu/page/susceptibility-data (accessed on January31, 2023

* L452R occurs in all BA.4/BA.5 lineages, but only in several BA.2. sublineages.

R346X and K444X occur in a growing number of BA.2 and BA.4/5 sublineages as a result of convergent evolution.

DISCUSSION

The paucity of head-to-head RCT comparisons amongst outpatient COVID-19 therapies makes the choice of therapy difficult. This meta-analysis allows comparison of placebo controlled RCT interventions amongst four main intervention classes-polyclonal convalescent plasma, monoclonal antibodies, small molecule antivirals and repurposed drugs. Participant features such as risk factors for COVID-19 progression (age, obesity, comorbid conditions), vaccination status and spike protein viral variation impact the hospital outcomes as a component of heterogeniety.

Outpatient RCT data confirm that most antiviral/antimicrobial therapies are more effective when given before rather than after hospital admission. In examining the full assembly of these effective, yet molecularly disparate interventions, we note the consistent importance of early outpatient treatment for patients at risk of progression to hospitalization31. Treatment within 5 days of illness onset was more effective than later treatment, as would be expected for an antiviral mechanism of action. An individual participant meta-analysis of CCP that investigated the effects of early compared to late treatment and of high compared to low dose antibody levels found that both early treatment and high levels of antibody combined to most effectively reduce risk of hospitalizations32.

The relative ease of conducting inpatient RCTs may have led most initial CCP, small molecule antiviral and repurposed trials – which were conducted principally by academic institutions - to be based in hospitals, often in patients treated too late for antiviral treatment to be expected to work, given that antiviral therapy must be given early in disease. The constrained resources available for clinical research by academic medicine during pandemic conditions further interfered with trial work, and several potentially valuable RCT’s with promising findings were terminated before they could provide definitive data. The findings of such trials are reported as null but often viewed as negative, notwithstanding trends towards effectiveness, and are rarely incorporated into clinical recommendations. The pharmaceutical industry – with well-established internal resources for trials and substantial economic support – was able to perform large outpatient trials of mAbs early in the pandemic. Inpatient services are generally more accessible to physician-scientists working in academic medical centers.

The choice, however, has been narrowed in recent months, and the clinical armamentarium has been reduced to small molecule antivirals, repurposed drugs and CCP, because single and double (“cocktail”) MAbs have lost effectiveness against new VOCs33. Both vaccine-elicited and disease-elicited antibodies are polyclonal, meaning that they include various isotypes that provide functional diversity and target numerous epitopes making variant escape much more difficult with CCP. Hence, polyclonal antibody preparations are much more resilient to the relentless evolution of variants. This is in marked contrast to mAbs, which target single epitopes of SARS-CoV-2. The exquisite mAb (and receptor binding domain) specificity renders mAbs susceptible to becoming ineffective with single amino acid changes. Plasma from individuals who have been both vaccinated and boosted is characterized by high amounts of neutralizing antibodies which can be effective against practically any existing VOC, including Omicron34 (so-called “heterologous immunity”, likely due to the well-known phenomenon of “epitope spreading”). Vaccine-boosted CCP has more than ten times the amount of total SARS-CoV-2 specific antibody and viral neutralizing activity compared to the pre-omicron CCP used in the effective outpatient CCP RCTs.

In addition to efficacy, other points to consider in an outpatient pandemic are tolerability, scalability and affordability. Repurposed drugs are generally well tolerated, widely available and relatively inexpensive, but, as we have shown, have limited efficacy. By contrast, small molecule antivirals are often plagued by contraindications and side effects, which make several classes of patients reliant on passive immunotherapies. Both small molecule antivirals and mAbs take time to develop and are unaffordable in low-and-middle income countries (LMIC). CCP is instead a tolerable, scalable, and affordable treatment and is usually provided in a single IV session, in contrast to remdesivir, which requires a three-day intravenous course.

On Dec. 28, 2021 the FDA expanded the authorized emergency use of convalescent plasma with high titers of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies “for the treatment of COVID-19 in patients with immunosuppressive disease or receiving immunosuppressive treatment, in either the outpatient or inpatient setting.” This EUA noted that CCP was safe and effective in immunocompetent individuals and allowed under the emergency measure of the pandemic, but expanded its use in immunosuppressed individuals to outpatient use, notwithstanding the availability of oral drugs and (at that time) two remaining effective mAb treatments for the new omicron variants of concerns.

Limitations of evidence in this review process included general meta-analysis etiologies such as English only publications, limited class subgroup analysis due to low numbers like CCP or mAb, grouping diverse mechanisms of action in the SMA and RP classes which increases heterogeneity, heterogeneity loss of power when evaluating CCP and SMA due to smaller single digit number of RCTs evaluated or reporting bias towards positive successfully executed studies which might miss marginal or futile studies. While risk of bias was independently performed on more than 80% of studies by COVID-19-NMA, the RevMan program determined the missing risk of bias. Unique limitations to outpatient COVID-19 studies are diverse patient population varying in age and comorbidities, changes in outpatient standard of care and vaccination status over both the regions and period covered which led to wide variation in hospital rates which were also influenced by regional accessibility to hospitalization, depending on hospital capacity and other outpatient intervention like mAb early in pandemic. Studies also reported either all cause hospitalization or COVID-19 related hospitalization within the 2 week or 4 week outcome reporting time period as listed in appendix tables. While the pooled OR focused on just hospital rates between studies, the full data set in appendix allowing comparison of just COVID-19 related hospitalizations, pre-Alpha period trials. The outpatient RCTs reviewed here were conducted during different time-periods during the pandemic, thus targeting different variants, and enrolled participants with different vaccination statuses. Further heterogeneity was contributed by variation across the RCTs, in participant age, medical risk factors and serological status.

The published mAbs RCTs assembled here showed better overall class efficacy than other outpatient interventional classes, yet mAb are now clinically ineffective against BQ.1.* and XBB.* Omicron variants. CCP and small molecule antivirals have comparable levels of effectiveness with many individual RCTS, but the latter have many contraindications and side effects. Repurposed drugs are largely either ineffective or mildly effective with just 2 RCT within the class approaching nirmatrelivir or mAbs. CCP is the remaining effective passive antibody therapy, which is especially important in the immunosuppressed but, as the trials show, early treatment with high levels of antibody, has value in other populations as well. Our clinical recommendation from this review is to use CCP on an out-patient basis in regions with no other therapy available regardless of vaccination status for those at high risk of progression to hospitalization.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the U.S. Department of Defense’s Joint Program Executive Office for Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Defense (JPEO-CBRND), in collaboration with the Defense Health Agency (DHA) (contract number: W911QY2090012) (DS, AC, DH), with additional support from Bloomberg Philanthropies, State of Maryland, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases 3R01AI152078–01S1 (DS, AC), NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences U24TR001609-S3 and UL1TR003098 (DH).

Abbreviations:

- CCP

COVID-19 convalescent plasma

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- VOC

variant of concern

Appendix

Description of trial participants

The median age of participants was about 50 years. The CCP group had a nonweighted trial average of median age equal to 58 years, while the anti-Spike mAbs, small molecule antivirals and repurposed drug groups younger average of median age was equal to 45 to 48 years. Most RCTs had more women than men, and 84% of all RCT 60,043 participants had Caucasian ethnicity (Appendix Table 2a,b).

The individual RCTs differed in the percentage of participants with risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19. Of the 37 RCTs reporting aggregated hospitalization risk factors, ten had 100% of participants with at least one hospitalization risk factor, while 5 had fewer than 50%. The bebtelovimab placebo-controlled RCT explicitly focused exclusively on low-risk individuals 1. Individual risk factors such as diabetes mellitus occurred in 10 to 20% of participants in most RCTs. Obesity with BMI over 29 averaged near 40% of RCT participants in the 4 therapy groups after excluding the large single 25,000 molnupiravir-PANORAMIC RCT with 15% of participants with BMI’s over 30 (Appendix Table 2a,b) 25.

Of 18 RCTs reporting seropositivity rates at baseline, 11 had < 25% screening seropositive (Appendix Table 2a,b, main text Figure 2). The molnupiravir-PANORAMIC RCT was an outlier, with 98% participant seropositives25. All but one2 of the RCTs enrolled within 8 days (median) of symptom onset. In RCTs of anti-Spike mAbs and small molecule antivirals, median time from illness onset to intervention was 3.5 to 4 days (Appendix Fig 1, Appendix Table 2a,b). CCP and repurposed antiviral drug RCTs enrolled within 4.5 to 5.1 days from symptom onset.

The CCP RCTs were conducted in the USA3,4, Argentina5, Netherlands6 and Spain7 (Appendix Table 2). The anti-Spike mAb RCTs all had a USA component, but were largely centered in the Americas except for the sotrovimab RCT, which took place in Spain8. Many of the repurposed drugs and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir RCTs recruited worldwide9.

Four of the five CCP RCTs (COV-Early6, CONV-ERT7, Argentina5 and C3PO4), and all eight anti-Spike mAb RCTs took place in the setting of the D614G variant and the Alpha VOC (main text-Figure 2). By contrast, most of the molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir9 and interferon lambda RCTs were conducted in the setting of the Delta VOC. The ivermectin10 and fluvoxamine11 RCTs ended as the Delta VOC wave began in August 2021. The remdesivir RCT spanned D614G, Alpha and Beta VOC but missed Delta12. The CSSC-004 RCT of CCP was the longest RCT reviewed, spanning periods characterized by D614G to Delta VOC infections3.

Appendix Figure 1.

Comparison of mean interval from symptom onset to enrollment/intervention as well as per protocol interval inclusion limit for all participants.

Appendix Figure 2: Odds ratio for hospitalizations from all interventions.

Therapeutic interventions ordered according to mechanism of action (CCP, anti-Spike mAbs, small molecule antivirals and repurposed drugs

Appendix Figure 3: Odds ratio for hospitalizations from all interventions by region.

Therapeutic interventions ordered region including diverse interventions

Appendix Figure 4: Odds ratio for hospitalizations within CCP group.

A) All CCP trials excluding CCP-Argentina with a non hospital endpoint of severe respiratory distress or B) All CCP excluding CONV-ERT because of methylene blue inactivation of antibody function. C) all cause hospitalization for CSSC-004 to match all cause hospitalization for other CCP studies

Appendix Figure 5: Odds ratio for hospitalizations sensitivity analysis.

Odds ratio for hospitalizations with diverse therapeutic interventions, grouped according to mechanism of action (CCP, mAbs, small molecule antivirals and repurposed drugs) with the largest enrollment removed

Appendix Figure 6:

Risk of bias by RCT

Appendix Figure 7: Funnel plots by RCTs class.

Publication bias was examined with Egger Test for Funnel Plot asymmetry. A weighted regression model with multiplicative dispersion used standard error for prediction. A) CCP Funnel Plot Asymmetry (t=1.0879, df=3, p=0.3562). The limit estimate (as sei≥0) b=0.4699 (CI:-2.0201,2.9598) B) anti-Spike mAbs Funnel Plot Asymmetry (t=0.5087, df=7, p=0.6266). The limit estimate (as sei≥0) b=-1.2940 (CI:-2.0658, 0.5221) C) small molecule antivirals Funnel Plot Asymmetry (t=0.0695, df=15, p=0.9455). The limit estimate (as sei≥0) b= −0.2627 (CI:-0.7860, 0.2606) and D) repurposed drugs Funnel Plot Asymmetry (t=0.0645, df=37, p=0.9489). The limit estimate (as sei≥0) b= −0.2080 (CI: −0.4146, −0.0013). For anti-Spike mAbs RCTs, there is a suggestion of missing studies on the right side of the plot, where results would be unfavourable to the experimental intervention, for which either very high efficacy of high-dose anti-Spike mAbs or non-reporting bias is a plausible explanation.

Table 1.

Included and Excluded trials in search of May 2023 281 studies

| publication number | excluded reason | included in review | class | RCT per study | unique intervention | study name | ref |

| 12 | 1 | CCP | 1 | 1 | CCP-CONV-ert | Alemany A, Millat-Martinez P, Corbacho-Monne M, et al. High-titre methylene blue-treated convalescent plasma as an early treatment for outpatients with COVID-19: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10(3): 278–88. | |

| 92 | 1 | CCP | 1 | CCP-COV-early | Gharbharan A, Jordans C, Zwaginga L, et al. Outpatient convalescent plasma therapy for high-risk patients with early COVID-19: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022. | ||

| 132 | 1 | CCP | 1 | CCP-C3PO | Korley FK, Durkalski-Mauldin V, Yeatts SD, et al. Early Convalescent Plasma for High-Risk Outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385(21): 1951–60. | ||

| 150 | 1 | CCP | 1 | CCP-Argentina | Libster R, Perez Marc G, Wappner D, et al. Early High-Titer Plasma Therapy to Prevent Severe Covid-19 in Older Adults. N Engl J Med 2021; 384(7): 610–8. | ||

| 252 | 1 | CCP | 1 | CCP-CSSC-004 | Sullivan DJ, Gebo KA, Shoham S, et al. Early Outpatient Treatment for Covid-19 with Convalescent Plasma. N Engl J Med 2022; 386(18): 1700–11. | ||

| 54 | 1 | mab | 1 | 1 | Bamlanivimab-BLAZE-1 | Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody LY-CoV555 in Outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384(3): 229–37. | |

| 72 | 1 | mab | 1 | 1 | Bebtelovimab-BLAZE-4 | Dougan M, Azizad M, Chen P, et al. Bebtelovimab, alone or together with bamlanivimab and etesevimab, as a broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody treatment for mild to moderate, ambulatory COVID-19. medRxiv 2022: 2022.03.10.22272100. | |

| 73 | 1 | mab | 1 | 1 | Bamlanivimab/etesevimab-BLAZE-1 | Dougan M, Nirula A, Azizad M, et al. Bamlanivimab plus Etesevimab in Mild or Moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385(15): 1382–92. | |

| 98 | 1 | mab | 1 | 1 | Sotrovimab-COMET-ICE | Gupta A, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, Juarez E, et al. Early Treatment for Covid-19 with SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody Sotrovimab. N Engl J Med 2021. | |

| 129 | 1 | mab | 1 | 1 | Regdanvimab-CT-P59–2 | Kim JY, Sandulescu O, Preotescu LL, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Regdanvimab in High-Risk Patients With Mild-to-Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9(8): ofac406. | |

| 184 | 1 | mab | 1 | 1 | Tixagevimab–cilgavimab-TACKLE | Montgomery H, Hobbs FDR, Padilla F, et al. Efficacy and safety of intramuscular administration of tixagevimab-cilgavimab for early outpatient treatment of COVID-19 (TACKLE): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10(10): 985–96. | |

| 195 | 1 | mab | 1 | 1 | Casirivimab/imdevimab-REGEN-COV Ph 1/2 | Norton T, Ali S, Sivapalasingam S, et al. REGEN-COV Antibody Combination in Outpatients With COVID-19 – Phase 1/2 Results. medRxiv 2022: 2021.06.09.21257915. | |

| 251 | 1 | mab | 1 | Regdanvimab-CT-P59 | Streinu-Cercel A, Sandulescu O, Preotescu LL, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Regdanvimab (CT-P59): A Phase 2/3 Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial in Outpatients With Mild-to-Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9(4): ofac053. | ||

| 275 | 1 | mab | 1 | Casirivimab/imdevimab-REGEN-COV Ph 3 | Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al. REGEN-COV Antibody Combination and Outcomes in Outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 385(23): e81. | ||

| 7 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Homeopathy-COVID-Simile | Adler UC, Adler MS, Padula AEM, et al. Homeopathy for COVID-19 in primary care: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (COVID-Simile study). J Integr Med 2022; 20(3): 221–9. | |

| 24 | 1 | rp | 1 | Enoxaparin-OVID | Barco S, Voci D, Held U, et al. Enoxaparin for primary thromboprophylaxis in symptomatic outpatients with COVID-19 (OVID): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol 2022; 9(8): e585-e93. | ||

| 39 | 1 | rp | 3 | Metformin-COVID-OUT | Bramante CT, Huling JD, Tignanelli CJ, et al. Randomized Trial of Metformin, Ivermectin, and Fluvoxamine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2022; 387(7): 599–610. | ||

| 48 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Niclosamide | Cairns DM, Dulko D, Griffiths JK, et al. Efficacy of Niclosamide vs Placebo in SARS-CoV-2 Respiratory Viral Clearance, Viral Shedding, and Duration of Symptoms Among Patients With Mild to Moderate COVID-19: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5(2): e2144942. | |

| 58 | 1 | rp | 1 | Inhaled Ciclesonide-COVIS | Clemency BM, Varughese R, Gonzalez-Rojas Y, et al. Efficacy of Inhaled Ciclesonide for Outpatient Treatment of Adolescents and Adults With Symptomatic COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2022; 182(1): 42–9. | ||

| 60 | 1 | rp | 3 | 1 | Aspirin-ACTIV-4B | Connors JM, Brooks MM, Sciurba FC, et al. Effect of Antithrombotic Therapy on Clinical Outcomes in Outpatients With Clinically Stable Symptomatic COVID-19: The ACTIV-4B Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021; 326(17): 1703–12. | |

| 61 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Enoxaparin-ETHIC | Cools F, Virdone S, Sawhney J, et al. Thromboprophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin versus standard of care in unvaccinated, at-risk outpatients with COVID-19 (ETHIC): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Haematol 2022; 9(8): e594-e604. | |

| 76 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Inhaled ciclesonide-COVERAGE | Duvignaud A, Lhomme E, Onaisi R, et al. Inhaled ciclesonide for outpatient treatment of COVID-19 in adults at risk of adverse outcomes: a randomised controlled trial (COVERAGE). Clin Microbiol Infect 2022; 28(7): 1010–6. | |

| 93 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Sulodexide | Gonzalez-Ochoa AJ, Raffetto JD, Hernandez AG, et al. Sulodexide in the Treatment of Patients with Early Stages of COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Thromb Haemost 2021; 121(7): 944–54. | |

| 107 | 1 | rp | 1 | Azithromycin-Atomic2 | Hinks TSC, Cureton L, Knight R, et al. Azithromycin versus standard care in patients with mild-to-moderate COVID-19 (ATOMIC2): an open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9(10): 1130–40. | ||

| 115 | 1 | rp | 1 | Hydroxychloroquine-BMG | Johnston C, Brown ER, Stewart J, et al. Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin for treatment of early SARS-CoV-2 infection among high-risk outpatient adults: A randomized clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 33: 100773. | ||

| 128 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Saliravira | Khorshiddoust RR, Khorshiddoust SR, Hosseinabadi T, et al. Efficacy of a multiple-indication antiviral herbal drug (Saliravira(R)) for COVID-19 outpatients: A pre-clinical and randomized clinical trial study. Biomed Pharmacother 2022; 149: 112729. | |

| 145 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Fluvoxamine-STOP COVID | Lenze EJ, Mattar C, Zorumski CF, et al. Fluvoxamine vs Placebo and Clinical Deterioration in Outpatients With Symptomatic COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020; 324(22): 2292–300. | |

| 168 | 1 | rp | 1 | Fluvoxamine-ACTIV-6 | McCarthy MW, Naggie S, Boulware DR, et al. Effect of Fluvoxamine vs Placebo on Time to Sustained Recovery in Outpatients With Mild to Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023; 329(4): 296–305. | ||

| 173 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Resveratrol | McCreary MR, Schnell PM, Rhoda DA. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled proof-of-concept trial of resveratrol for outpatient treatment of mild coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Sci Rep 2022; 12(1): 10978. | |

| 281 | 1 | rp | 1 | Hydroxychloroquine-BCN PEP-CoV-2 | Mitja O, Corbacho-Monne M, Ubals M, et al. Hydroxychloroquine for Early Treatment of Adults With Mild Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73(11): e4073-e81. | ||

| 189 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Ivermectin high dose-ACTIV-6 | Naggie S, Boulware DR, Lindsell CJ, et al. Effect of Higher-Dose Ivermectin for 6 Days vs Placebo on Time to Sustained Recovery in Outpatients With COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023; 329(11): 888–97. | |

| 187 | 1 | rp | 1 | Ivermectin-ACTIV-6 | Naggie S, Boulware DR, Lindsell CJ, et al. Effect of Ivermectin vs Placebo on Time to Sustained Recovery in Outpatients With Mild to Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022; 328(16): 1595–603. | ||

| 198 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Azithromycin-ACTION | Oldenburg CE, Pinsky BA, Brogdon J, et al. Effect of Oral Azithromycin vs Placebo on COVID-19 Symptoms in Outpatients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021; 326(6): 490–8. | |

| 214 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Losartan-MN | Puskarich MA, Cummins NW, Ingraham NE, et al. A multi-center phase II randomized clinical trial of losartan on symptomatic outpatients with COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 37: 100957. | |

| 219 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Metformin-TOGETHER | Reis G, Dos Santos Moreira Silva EA, Medeiros Silva DC, et al. Effect of early treatment with metformin on risk of emergency care and hospitalization among patients with COVID-19: The TOGETHER randomized platform clinical trial. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022; 6: 100142. | |

| 220 | 1 | rp | 1 | Fluvoxamine/budesonide-TOGETHER | Reis G, Dos Santos Moreira Silva EA, Medeiros Silva DC, et al. Oral Fluvoxamine With Inhaled Budesonide for Treatment of Early-Onset COVID-19 : A Randomized Platform Trial. Ann Intern Med 2023; 176(5): 667–75. | ||

| 221 | 1 | rp | 1 | Fluvoxamine-TOGETHER | Reis G, Dos Santos Moreira-Silva EA, Silva DCM, et al. Effect of early treatment with fluvoxamine on risk of emergency care and hospitalisation among patients with COVID-19: the TOGETHER randomised, platform clinical trial. Lancet Glob Health 2022; 10(1): e42-e51. | ||

| 224 | 1 | rp | 1 | Ivermectin-TOGETHER | Reis G, Silva E, Silva DCM, et al. Effect of Early Treatment with Ivermectin among Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2022; 386(18): 1721–31. | ||

| 227 | 1 | rp | 1 | Ivermectin Iran | Rezai MS, Ahangarkani F, Hill A, et al. Non-effectiveness of Ivermectin on Inpatients and Outpatients With COVID-19; Results of Two Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022; 9: 919708. | ||

| 229 | 1 | rp | 1 | Hydroxychloroquine/Azithromycin-Brazil | Rodrigues C, Freitas-Santos RS, Levi JE, et al. Hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin early treatment of mild COVID-19 in an outpatient setting: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluating viral clearance. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2021; 58(5): 106428. | ||

| 233 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Nitazoxanide-Romark | Rossignol JF, Bardin MC, Fulgencio J, Mogelnicki D, Brechot C. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of nitazoxanide for treatment of mild or moderate COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine 2022; 45: 101310. | |

| 241 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Hydroxychloroquine-AH COVID-19 | Schwartz I, Boesen ME, Cerchiaro G, et al. Assessing the efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine as outpatient treatment of COVID-19: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Open 2021; 9(2): E693-E702. | |

| 245 | 1 | rp | 1 | Hydroxychloroquine-COVID-19 PEP | Skipper CP, Pastick KA, Engen NW, et al. Hydroxychloroquine in Nonhospitalized Adults With Early COVID-19 : A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173(8): 623–31. | ||

| 249 | 1 | rp | 1 | Hydroxychloroquine-Utah | Spivak AM, Barney BJ, Greene T, et al. A Randomized Clinical Trial Testing Hydroxychloroquine for Reduction of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Shedding and Hospitalization in Early Outpatient COVID-19 Infection. Microbiol Spectr 2023; 11(2): e0467422. | ||

| 257 | 1 | rp | 1 | 1 | Colchicine-COLCORONA | Tardif JC, Bouabdallaoui N, ĽAllier PL, et al. Colchicine for community-treated patients with COVID-19 (COLCORONA): a phase 3, randomised, double-blinded, adaptive, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9(8): 924–32. | |

| 259 | 1 | rp | 3 | 1 | Zinc | Thomas S, Patel D, Bittel B, et al. Effect of High-Dose Zinc and Ascorbic Acid Supplementation vs Usual Care on Symptom Length and Reduction Among Ambulatory Patients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The COVID A to Z Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4(2): e210369. | |

| 36 | 1 | sma | 1 | 1 | Favipiravir-Avi-Mild-19 | Bosaeed M, Alharbi A, Mahmoud E, et al. Efficacy of favipiravir in adults with mild COVID-19: a randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022; 28(4): 602–8. | |

| 46 | 1 | sma | 1 | Molnupiravir-PANORAMIC | Butler CC, Hobbs FDR, Gbinigie OA, et al. Molnupiravir plus usual care versus usual care alone as early treatment for adults with COVID-19 at increased risk of adverse outcomes (PANORAMIC): an open-label, platform-adaptive randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2023; 401(10373): 281–93. | ||

| 82 | 1 | sma | 1 | 1 | Interferon Lambda-ILIAD | Feld JJ, Kandel C, Biondi MJ, et al. Peginterferon lambda for the treatment of outpatients with COVID-19: a phase 2, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9(5): 498–510. | |

| 95 | 1 | sma | 1 | 1 | Remdesivir-PINETREE | Gottlieb RL, Vaca CE, Paredes R, et al. Early Remdesivir to Prevent Progression to Severe Covid-19 in Outpatients. N Engl J Med 2022; 386(4): 305–15. | |

| 100 | 1 | sma | 1 | 1 | Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir-EPIC-HR | Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2022; 386(15): 1397–408. | |

| 112 | 1 | sma | 1 | Interferon Lambda-COVID-Lambda | Jagannathan P, Andrews JR, Bonilla H, et al. Peginterferon Lambda-1a for treatment of outpatients with uncomplicated COVID-19: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nature Communications 2021; 12(1): 1967. | ||

| 113 | 1 | sma | 1 | Molnupiravir-MOVe-OUT | Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, et al. Molnupiravir for Oral Treatment of Covid-19 in Nonhospitalized Patients. N Engl J Med 2022; 386(6): 509–20. | ||

| 118 | 1 | sma | 1 | Lopinavir/ritonavir-TREAT NOW | Kaizer AM, Shapiro NI, Wild J, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir for treatment of non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Infect Dis 2023; 128: 223–9. | ||

| 159 | 1 | sma | 3 | Favipiravir/Lopinavir/Ritonavir-FLARE | Lowe DM, Brown LK, Chowdhury K, et al. Favipiravir, lopinavir-ritonavir, or combination therapy (FLARE): A randomised, double-blind, 2 × 2 factorial placebo-controlled trial of early antiviral therapy in COVID-19. PLoS Med 2022; 19(10): e1004120. | ||

| 203 | 1 | sma | 1 | 1 | Tenofovir/Emtricitabine-AR0-CORONA | Parienti JJ, Prazuck T, Peyro-Saint-Paul L, et al. Effect of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate and Emtricitabine on nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 viral load burden amongst outpatients with COVID-19: A pilot, randomized, open-label phase 2 trial. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 38: 100993. | |

| 222 | 1 | sma | 2 | 1 | Lopinavir/ritonavir-TOGETHER | Reis G, Moreira Silva E, Medeiros Silva DC, et al. Effect of Early Treatment With Hydroxychloroquine or Lopinavir and Ritonavir on Risk of Hospitalization Among Patients With COVID-19: The TOGETHER Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4(4): e216468. | |

| 223 | 1 | sma | 1 | Interferon Lambda-TOGETHER | Reis G, Moreira Silva EAS, Medeiros Silva DC, et al. Early Treatment with Pegylated Interferon Lambda for Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2023; 388(6): 518–28. | ||

| 231 | 1 | sma | 1 | 1 | Sofosbuvir & daclatasvir-SOVODAK | Roozbeh F, Saeedi M, Alizadeh-Navaei R, et al. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir for the treatment of COVID-19 outpatients: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 76(3): 753–7. | |

| 260 | 1 | sma | 1 | 1 | Molnupiravir-Aurobindo | Tippabhotla SK, Lahiri S, Rama Raju D, Kandi C, Prasad VN. Efficacy and Safety of Molnupiravir for the Treatment of Non-Hospitalized Adults With Mild COVID-19: A Randomized, Open-Label, Parallel-Group Phase 3 Trial. SSRN 2022; 4042673. | |

| 264 | 1 | sma | 1 | Favipiravir-Iran | Vaezi A, Salmasi M, Soltaninejad F, Salahi M, Javanmard SH, Amra B. Favipiravir in the Treatment of Outpatient COVID-19: A Multicenter, Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Adv Respir Med 2023; 91(1): 18–25. | ||

| 25 | guidelines | Bassetti M, Giacobbe DR, Bruzzi P, et al. Clinical Management of Adult Patients with COVID-19 Outside Intensive Care Units: Guidelines from the Italian Society of Anti-Infective Therapy (SITA) and the Italian Society of Pulmonology (SIP). Infect Dis Ther 2021; 10(4): 1837–85. | |||||

| 62 | guidelines | Cuker A, Tseng EK, Nieuwlaat R, et al. American Society of Hematology living guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19: July 2021 update on postdischarge thromboprophylaxis. Blood Adv 2022; 6(2): 664–71. | |||||

| 80 | guidelines | Estcourt LJ, Cohn CS, Pagano MB, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines From the Association for the Advancement of Blood and Biotherapies (AABB): COVID-19 Convalescent Plasma. Ann Intern Med 2022; 175(9): 1310–21. | |||||

| 139 | guidelines | Kyriakoulis KG, Dimakakos E, Kyriakoulis IG, et al. Practical Recommendations for Optimal Thromboprophylaxis in Patients with COVID-19: A Consensus Statement Based on Available Clinical Trials. J Clin Med 2022; 11(20). | |||||

| 6 | no hospitalizations | Adel Mehraban MS, Shirzad M, Mohammad Taghizadeh Kashani L, et al. Efficacy and safety of add-on Viola odorata L. in the treatment of COVID-19: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. J Ethnopharmacol 2023; 304: 116058. | |||||

| 15 | no hospitalizations | Alizadeh Z, Keyhanian N, Ghaderkhani S, Dashti-Khavidaki S, Shokouhi Shoormasti R, Pourpak Z. A Pilot Study on Controlling Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Inflammation Using Melatonin Supplement. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2021; 20(4): 494–9. | |||||

| 29 | no hospitalizations | Bechlioulis A, Markozannes G, Chionidi I, et al. The effect of SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP1 agonists, and their sequential combination on cardiometabolic parameters: A randomized, prospective, intervention study. J Diabetes Complications 2023; 37(4): 108436. | |||||

| 31 | no hospitalizations | Ben Abdallah S, Mhalla Y, Trabelsi I, et al. Twice-Daily Oral Zinc in the Treatment of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76(2): 185–91. | |||||

| 32 | no hospitalizations | Bencheqroun H, Ahmed Y, Kocak M, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Multicenter Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of ThymoQuinone Formula (TQF) for Treating Outpatient SARS-CoV-2. Pathogens 2022; 11(5). | |||||

| 41 | no hospitalizations | Brennan CM, Nadella S, Zhao X, et al. Oral famotidine versus placebo in non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, data-intense, phase 2 clinical trial. Gut 2022; 71(5): 879–88. | |||||

| 44 | no hospitalizations | Bruno AM, Allshouse AA, Campbell HM, et al. Weight-Based Compared With Fixed-Dose Enoxaparin Prophylaxis After Cesarean Delivery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet Gynecol 2022; 140(4): 575–83. | |||||

| 68 | no hospitalizations | De Boeck I, Cauwenberghs E, Spacova I, et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of a Throat Spray with Selected Lactobacilli in COVID-19 Outpatients. Microbiol Spectr 2022; 10(5): e0168222. | |||||

| 103 | no hospitalizations | Hasanpour M, Safari H, Mohammadpour AH, et al. Efficacy of Covexir(R) (Ferula foetida oleo-gum) treatment in symptomatic improvement of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother Res 2022; 36(12): 4504–15. | |||||

| 125 | no hospitalizations | Khan A, Iqtadar S, Mumtaz SU, et al. Oral Co-Supplementation of Curcumin, Quercetin, and Vitamin D3 as an Adjuvant Therapy for Mild to Moderate Symptoms of COVID-19-Results From a Pilot Open-Label, Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Pharmacol 2022; 13: 898062. | |||||

| 127 | no hospitalizations | Khoo SH, FitzGerald R, Saunders G, et al. Molnupiravir versus placebo in unvaccinated and vaccinated patients with early SARS-CoV-2 infection in the UK (AGILE CST-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2023; 23(2): 183–95. | |||||

| 133 | no hospitalizations | Kosmopoulos A, Bhatt DL, Meglis G, et al. A randomized trial of icosapent ethyl in ambulatory patients with COVID-19. iScience 2021; 24(9): 103040. | |||||

| 155 | no hospitalizations | Lofgren SM, Nicol MR, Bangdiwala AS, et al. Safety of Hydroxychloroquine Among Outpatient Clinical Trial Participants for COVID-19. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7(11): ofaa500. | |||||

| 230 | no hospitalizations | Rohani M, Mozaffar H, Mesri M, Shokri M, Delaney D, Karimy M. Evaluation and comparison of vitamin A supplementation with standard therapies in the treatment of patients with COVID-19. East Mediterr Health J 2022; 28(9): 673–81. | |||||

| 256 | no hospitalizations | Tandon M, Wu W, Moore K, et al. SARS-CoV-2 accelerated clearance using a novel nitric oxide nasal spray (NONS) treatment: A randomized trial. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia 2022; 3: 100036. | |||||

| 1 | not outpt RCT | Aarnio-Peterson CM, Mara CA, Modi AC, Matthews A, Le Grange D, Shaffer A. Augmenting family based treatment with emotion coaching for adolescents with anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa: Trial design and methodological report. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2023; 33: 101118. | |||||

| 2 | not outpt RCT | Abbatecola AM, Incalzi RA, Malara A, et al. Monitoring COVID-19 vaccine use in Italian long term care centers: The GeroCovid VAX study. Vaccine 2022; 40(15): 2324–30. | |||||

| 3 | not outpt RCT | Abena PM, Decloedt EH, Bottieau E, et al. Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine for the Prevention or Treatment of COVID-19 in Africa: Caution for Inappropriate Off-label Use in Healthcare Settings. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2020; 102(6): 1184–8. | |||||

| 4 | not outpt RCT | Accelerating C-TI, Vaccines-6 Study G, Naggie S. Ivermectin for Treatment of Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19 in the Outpatient Setting: A Decentralized, Placebo-controlled, Randomized, Platform Clinical Trial. medRxiv 2022. | |||||

| 5 | not outpt RCT | Accelerating Covid-19 Therapeutic I, Vaccines-6 Study G, Naggie S. Inhaled Fluticasone for Outpatient Treatment of Covid-19: A Decentralized, Placebo-controlled, Randomized, Platform Clinical Trial. medRxiv 2022. | |||||

| 9 | not outpt RCT | Agusti A, Guillen E, Ayora A, et al. Efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine in healthcare professionals with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: Prospective, non-randomized trial. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed) 2022; 40(6): 289–95. | |||||

| 10 | not outpt RCT | Ainslie M, Brunette MF, Capozzoli M. Treatment Interruptions and Telemedicine Utilization in Serious Mental Illness: Retrospective Longitudinal Claims Analysis. JMIR Ment Health 2022; 9(3): e33092. | |||||

| 11 | not outpt RCT | Akca Sumengen A, Ocakci AF. Evaluation of the effect of an education program using cartoons and comics on disease management in children with asthma: a randomized controlled study. J Asthma 2023; 60(1): 11–23. | |||||

| 13 | not outpt RCT | Alemany A, Millat-Martinez P, Corbacho-Monne M, et al. Subcutaneous anti-COVID-19 hyperimmune immunoglobulin for prevention of disease in asymptomatic individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine 2023; 57: 101898. | |||||

| 14 | not outpt RCT | Ali R, Patel A, Waqas MA, Trivedi K, Slim J. Functionality of Monoclonal Antibody Therapy in SARS-CoV-2. J Med Cases 2022; 13(8): 380–5. | |||||

| 16 | not outpt RCT | Aref ZF, Bazeed S, Hassan MH, et al. Possible Role of Ivermectin Mucoadhesive Nanosuspension Nasal Spray in Recovery of Post-COVID-19 Anosmia. Infect Drug Resist 2022; 15: 5483–94. | |||||

| 17 | not outpt RCT | Avezum A, Oliveira GBF, Oliveira H, et al. Hydroxychloroquine versus placebo in the treatment of non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19 (COPE - Coalition V): A double-blind, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022; 11: 100243. | |||||

| 18 | not outpt RCT | Axfors C, Schmitt AM, Janiaud P, et al. Mortality outcomes with hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in COVID-19 from an international collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials. Nat Commun 2021; 12(1): 2349. | |||||

| 20 | not outpt RCT | Bahmer T, Borzikowsky C, Lieb W, et al. Severity, predictors and clinical correlates of Post-COVID syndrome (PCS) in Germany: A prospective, multicentre, population-based cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2022; 51: 101549. | |||||

| 21 | not outpt RCT | Baksh S, Heath SL, Fukuta Y, et al. Symptom duration and resolution with early outpatient treatment of convalescent plasma for COVID-19: a randomized trial. J Infect Dis 2023. | |||||

| 22 | not outpt RCT | Barati S, Feizabadi F, Khalaj H, et al. Evaluation of noscapine-licorice combination effects on cough relieving in COVID-19 outpatients: A randomized controlled trial. Front Pharmacol 2023; 14: 1102940. | |||||

| 23 | not outpt RCT | Barchuk A, Cherkashin M, Bulina A, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against referral to hospital after SARS-CoV-2 infection in St. Petersburg, Russia, during the Delta variant surge: a test-negative case-control study. BMC Med 2022; 20(1): 312. | |||||

| 26 | not outpt RCT | Batalik L, Dosbaba F, Hartman M, Konecny V, Batalikova K, Spinar J. Long-term exercise effects after cardiac telerehabilitation in patients with coronary artery disease: 1-year follow-up results of the randomized study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2021; 57(5): 807–14. | |||||

| 27 | not outpt RCT | Batioglu-Karaaltin A, Yigit O, Cakan D, et al. Effect of the povidone iodine, hypertonic alkaline solution and saline nasal lavage on nasopharyngeal viral load in COVID-19. Clin Otolaryngol 2023. | |||||

| 28 | not outpt RCT | Bauer A, Schreinlechner M, Sappler N, et al. Discontinuation versus continuation of renin-angiotensin-system inhibitors in COVID-19 (ACEI-COVID): a prospective, parallel group, randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9(8): 863–72. | |||||

| 30 | not outpt RCT | Behrouzi B, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, et al. Association of Influenza Vaccination With Cardiovascular Risk: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5(4): e228873. | |||||

| 33 | not outpt RCT | Bhatia T, Kumari N, Yadav A, et al. Feasibility, acceptability and evaluation of meditation to augment yoga practice among persons diagnosed with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatr 2022; 34(6): 330–43. | |||||

| 35 | not outpt RCT | Bledsoe J, Woller SC, Brooks M, et al. Clinically stable covid-19 patients presenting to acute unscheduled episodic care venues have increased risk of hospitalization: secondary analysis of a randomized control trial. BMC Infect Dis 2023; 23(1): 325. | |||||

| 37 | not outpt RCT | Boudreaux ED, Larkin C, Sefair AV, et al. Studying the implementation of Zero Suicide in a large health system: Challenges, adaptations, and lessons learned. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2022; 30: 100999. | |||||

| 38 | not outpt RCT | Bramante CT, Buse J, Tamaritz L, et al. Outpatient metformin use is associated with reduced severity of COVID-19 disease in adults with overweight or obesity. J Med Virol 2021; 93(7): 4273–9. | |||||

| 40 | not outpt RCT | Bramante CT, Johnson SG, Garcia V, et al. Diabetes medications and associations with Covid-19 outcomes in the N3C database: A national retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2022; 17(11): e0271574. | |||||

| 47 | not outpt RCT | Cadegiani FA, Goren A, Wambier CG, McCoy J. Early COVID-19 therapy with azithromycin plus nitazoxanide, ivermectin or hydroxychloroquine in outpatient settings significantly improved COVID-19 outcomes compared to known outcomes in untreated patients. New Microbes New Infect 2021; 43: 100915. | |||||

| 50 | not outpt RCT | Cavanna L, Citterio C. Randomised clinical trials on outpatient treatment of SARS-COV-2 infection: Light and shadows. Int J Clin Pract 2021; 75(12): e14896. | |||||

| 52 | not outpt RCT | Chawla A, Birger R, Wan H, et al. Factors Influencing COVID-19 Risk: Insights From Molnupiravir Exposure-Response Modeling of Clinical Outcomes. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2023; 113(6): 1337–45. | |||||

| 53 | not outpt RCT | Chen L, Zhou YZ, Zhou XM, et al. Evaluation of the "safe multidisciplinary app-assisted remote patient-self-testing (SMART) model" for warfarin home management during the COVID-19 pandemic: study protocol of a multi-center randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2021; 21(1): 875. | |||||

| 56 | not outpt RCT | Christie LJ, Fearn N, McCluskey A, et al. Remote constraint induced therapy of the upper extremity (ReCITE): A feasibility study protocol. Front Neurol 2022; 13: 1010449. | |||||

| 57 | not outpt RCT | Clark J, Tong SYC. In outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19, low-dose fluvoxamine did not reduce time to sustained recovery. Ann Intern Med 2023; 176(5): JC52. | |||||

| 59 | not outpt RCT | Cohen JB, Hanff TC, Corrales-Medina V, et al. Randomized elimination and prolongation of ACE inhibitors and ARBs in coronavirus 2019 (REPLACE COVID) Trial Protocol. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2020; 22(10): 1780–8. | |||||

| 63 | not outpt RCT | D'Ascanio L, Vitelli F, Cingolani C, Maranzano M, Brenner MJ, Di Stadio A. Randomized clinical trial "olfactory dysfunction after COVID-19: olfactory rehabilitation therapy vs. intervention treatment with Palmitoylethanolamide and Luteolin": preliminary results. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021; 25(11): 4156–62. | |||||

| 64 | not outpt RCT | da Silva RM, Gebe Abreu Cabral P, de Souza SB, et al. Serial viral load analysis by DDPCR to evaluate FNC efficacy and safety in the treatment of mild cases of COVID-19. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023; 10: 1143485. | |||||