Abstract

Rationale:

To analyze clinical and imaging features, ciliary structure and family gene mutation loci of a primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) boy with a dual-allele heterozygous mutation of DNAH5.

Patient concerns:

Clinical data of the proband and relatives. Electronic bronchoscopy, transmission electron microscope (TEM) of the cilia and next-generation sequencing (NGS) were performed. PCD-related DNAH5 exon mutation sites were searched.

Diagnoses:

A 10-year and 10-month-old boy was hospitalized due to “recurrent cough, expectoration, sputum and shortness of breathing after activity for over 7 years, and aggravated for 1 week.” Moderate and fine wet rales were detected in bilateral lungs. Clubbing fingers and toes were observed. In local hospitals, he was diagnosed with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection and Streptococcus pneumoniae was cultured.

Interventions:

Pulmonary function testing showed mixed ventilation dysfunction and positive for bronchial dilation test. Imaging examination and fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed transposition of all viscera, bilateral pneumonia, and bronchiectasis. TEM detected no loss of the outer dynein arms. NGS identified 2 mutations (c.4360C>T, c.9346C>T) in the DNAH5 gene inherited from healthy parents.

Outcomes:

According to literature review until 2022, among 144 exon gene mutations causing amino acid changes, C>T mutation is the most common in 44 cases, followed by deletion mutations in 30 cases. Among the amino acid changes induced by gene mutation, terminated mutations were identified in 89 cases.

Lessons:

For suspected PCD patients, TEM and NGS should be performed. Prompt diagnosis and treatment may delay the incidence of bronchiectasis and improve clinical prognosis.

Keywords: DNAH5, gene mutation, next-generation sequencing, primary ciliary dyskinesia, transmission electron microscope

1. Introduction

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is an autosomal recessive monogenic disease caused by gene abnormality. Approximately 50% of PCD patients develop abnormal changes in organ laterality during the first-trimester pregnancy. The incidence of male and female is basically equivalent.[1] PCD has an estimated prevalence rate of 1:15–300,000 live births.[2]

More than 200 genes have been confirmed to encode ciliary proteins,[3] and nearly 40 PCD-associated pathogenic genes have been reported according to Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM).[4] Among them, DNAH5 (OMIM:603335) gene mutation is the most common, accounting for 15% to 21%.[5] There is correlation and heterogeneity between the genotype and clinical phenotype of PCD.[6] No gold standard has been reached for the diagnosis of the heterogeneity of clinical phenotype, leading to delays in the diagnosis and treatment of PCD, especially for those with mild symptoms, but without abnormal visceral laterality.[7]

Only 2 PCD cases of DNAH5 gene mutation have been reported in China until June, 2018.[8,9] Here, we reported 1 case of Kartagener syndrome, a variant of PCD, associated with a dual-allele heterozygous mutation of DNAH5. Clinical features, ciliary structure and loci of family gene mutations were described as follows.

2. Case presentation

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. Written informed consents were obtained from the guardians in this study.

The proband was a boy, aged 10 years and 10 months, developed recurrent respiratory infections and visceral transposition after age 3. His parents and younger brother were healthy. He was admitted to hospital (January 31, 2018) because of “repeated cough, expectoration, shortness of breath after exercise for 7 years, and aggravated for 1 week.” CT scan revealed the inflammation of bilateral maxillary sinus and ethmoid sinus, inferior nasal congestion, lung inflammation, atelectasis of the middle lobe and lingular segment and bronchiectasis and total visceral transposition.

Purulent rhinorrhea and poor ventilation were found. Mild tenderness was palpable in bilateral maxillary sinuses. Pharyngeal congestion, bilateral tonsillitis II and slight shortness of breath were found. Moderate to slight moist rales were audible in both inferior lungs. Slight clubbed fingers and toes were noted. C-reactive protein was detected as 11 mg/L, white blood cell count was 16.84 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage was 69.8%, Hb was 131g/L, Plt was 343 × 109/L. PO2 was 85 mm Hg and PCO2 of 37.8 mm Hg. He tested positive for blood MP-IgM, and sputum MP-DNA was ranged from 2.33 × 103 to 8.17 × 105 copies. Streptococcus pneumoniae was detected in 1 sputum culture test (+++). He was positive for bronchodilation test. The lowest values of PEF and FEVl were 56.7% and 64.0%. The variation rate of PEF was 15.5%. The FEV1/FVC ratio was 56.7%, respectively. Mild mixed ventilation dysfunction was confirmed. FVC/estimated FVC ratio was 56.7% and the variation rate of FVC was 19.2%.

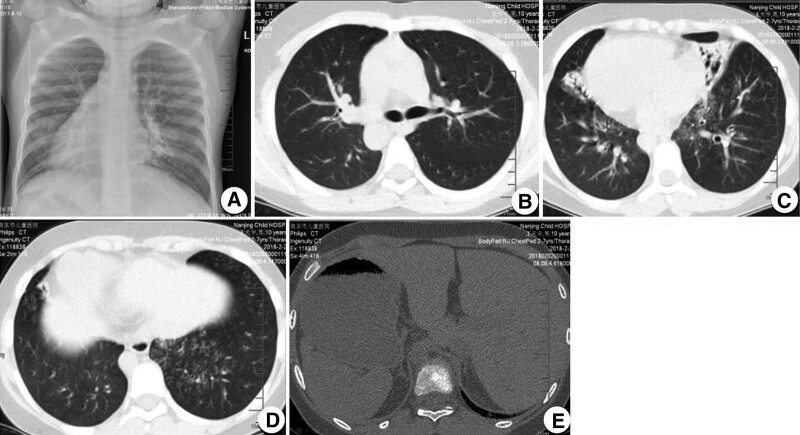

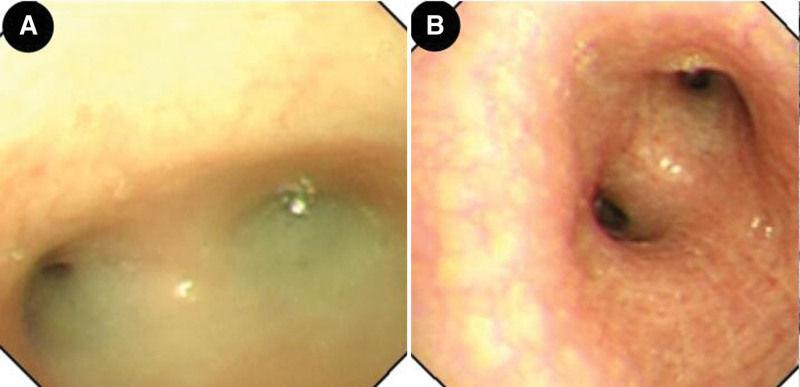

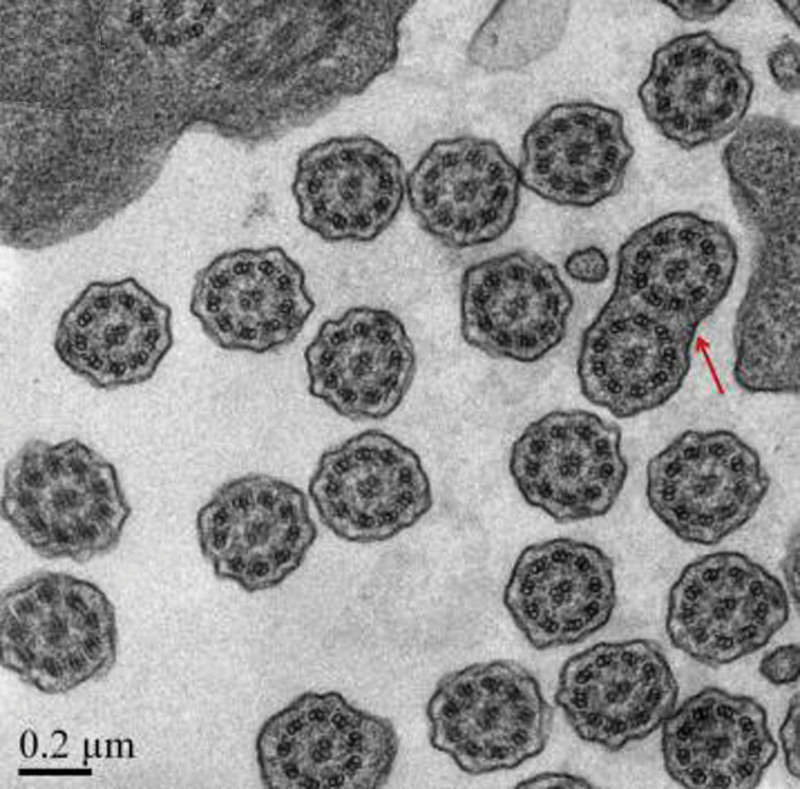

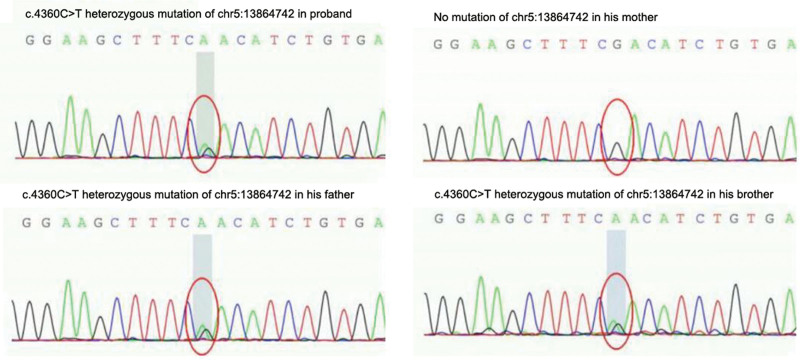

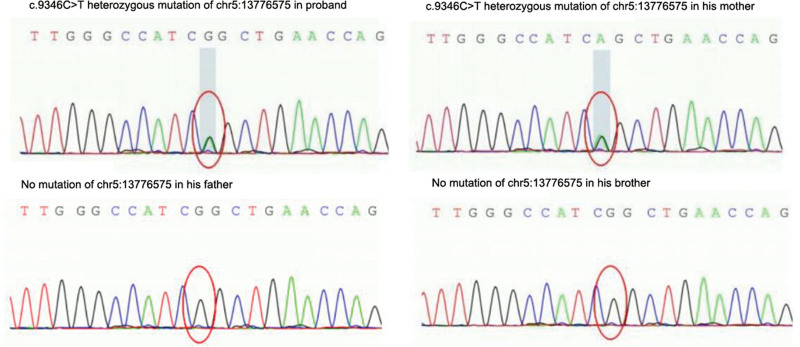

Total visceral transposition was found. Bilateral lung pneumonia was observed, as illustrated in Figure 1. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy displayed sticky secretions at the opening of the main bronchus and fish bone-like changes and small ulcers in the middle of the middle left bronchus (Fig. 2). Transmission electron microscope revealed no abnormal structural changes of 9 + 2 and no outer dynein arm in the transverse section. Amalgamation of cilium was denoted by the red arrow in Figure 3. Targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) verified the mutation site 1:DNAH5, chr5:13864742, c.4360C>T, leading to amino acid changes of p.R1454X, inherited from his father (Fig. 4). The mutation site 2:DNAH5, chr5:13776575, c.9346C>T was inherited from his mother (Fig. 5).

Figure 1.

B-mode ultrasound and CT scan showing transposition of the heart, bronchus, stomach, liver, and spleen (A, B, and E); The volume of the right ligule and the left middle lung was shrank, and bronchiectasis was seen. Multiple small patches were noted in the lower lobes.

Figure 2.

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy showing a large number of sticky secretions at the opening of the main bronchus (A) and fish bone-like changes and small ulcers in the middle of the middle left bronchus (B).

Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscopy revealing no abnormal structure of 9 + 2 and no ODA in the transverse section. Amalgamation of cilium (red arrow). ODA = outer dynein arm.

Figure 4.

Targeted next-generation sequencing indicating the mutation site 1: DNAH5, chr5:13864742, c.4360C>T inherited from his father.

Figure 5.

Targeted next-generation sequencing indicating the mutation site 2: DNAH5, chr5:13776575, c.9346C>T inherited from his mother.

He was eventually diagnosed with PCD, Kartagener syndrome and severe pneumonia. After 10-d intravenous injection of loxceftazidime sodium and erythromycin, sequential anti-infection therapy with oral azithromycin, mucosolvan, propafenone, back slapping, and postural drainage, the proband was discharged after 14-d hospitalization. During 6-month follow-up, the proband’s condition remained stable.

Relevant studies were searched using the keywords of “PCD,” “gene,” and “DNAH5” from CNKI, Wanfang Database, PubMed, HGMD, and OMIM from the inception of databases to November, 2022. Nineteen articles with relatively complete references were obtained. One hundred forty-four mutation sites of DNAH5 exon (cDNA) were associated with PCD (Table 1), and PCD caused by single mutation of DNAH5 exon was not reported.

Table 1.

Mutation sites (c.) and amino acid changes (p.) in PCD-associated DNAG5 exon.

| No. | Exon | Mutation site | Amino acid changes | No. | Exon | Mutation site | Amino acid changes | No. | Exon | Mutation site | Amino acid changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | c.232C>T | p.R78X | 49 | 33 | c.5588delT | p.F1863SfsX8 | 97 | 52 | c.8887C > G | p.Q2949E |

| 2 | 2 | c.252T>G | p.Y84X | 50 | 33 | c.5599_5600insC | p.I1867PfsX35 | 98 | 52 | c.8910_8911delATinsG | p.S2970LfsX7 |

| 3 | 5 | c.670C>T | p.R224X | 51 | 33 | c.5647C > T | R1883X | 99 | 53 | c.8998C > T | p.R3000X |

| 4 | 5 | c.717_729delCTACTTGACTCTA | p.D239EfsX11 | 52 | 35 | c.5983C > T | p.R1995X | 100 | 53 | c.8999G > A | p.A3000Q |

| 5 | 6 | c.832delG | p.A278RfsX27 | 53 | 35 | c.6037C > T | p.R2013X | 101 | 53 | c.9018C > T | splicing-mut. |

| 6 | 6 | c.894C>G | p.N298K | 54 | 36 | c.6086delG | p.G2029VfsX25 | 102 | 53 | c.9040C > T | p.R3000X |

| 7 | 8 | c.1108A>T | p.I370F | 55 | 37 | c.6132delT | p.A2045Ufs | 103 | 53 | c.9101delG | p.G3034VfsX23 |

| 8 | 9 | c.1206T>A | p.N402K | 56 | 36 | c.6249G > A | p.G2021EfsX12 | 104 | 55 | c.9213delC | p.H3071QfsX5 |

| 9 | 9 | c.1232A>G | p.Y411C | 57 | 37 | c.6304C > T | p.R2102C | 105 | 54 | c.9286C > T | p.R3096X |

| 10 | 10 | C.1427_1428delTT | p.F476SfsX26 | 58 | 37 | c.6335_6336insT | p.E2112HfsX10 | 106 | 55 | c.9346C > T | p.R3116X |

| 11 | 10 | c.1432C>T | p.R478X | 59 | 37 | c.6343delA | p.I2115X | 107 | 55 | c.9365delT | p.L3122X |

| 12 | 11 | c.1489C>T | p.Q497X | 60 | 37 | c.6647delA | p.K2216RfsX20 | 108 | 55 | c.9427A > T | p.K3143X |

| 13 | 11 | c.1619T>C | p.F540L | 61 | 41 | c.6763C > T | p.A2255X | 109 | 55 | c.9799C > T | p.E3267X |

| 14 | 11 | c.1627C>T | p.Q543X | 62 | 41 | c.6786delG | p.S2264VfsX2 | 110 | 57 | c.10048T > C | p.S3350P |

| 15 | 12 | c.1645A>G | p.N549D | 63 | 40 | c.6791G > A | p.S2264N | 111 | 59 | c.10226G > C | p.W3409S |

| 16 | 12 | c.1667A>G | p.D556G | 64 | 41 | c.6932_6935delACTG | p.D2311GfsX14 | 112 | 61 | c.10363G > T | p.Q3455X |

| 17 | 12 | c.1730G>C | p.N549_R577delfsX5 | 65 | 42 | c.7039G > A | p.E2347K | 113 | 60 | c.10365G > C | p.Q3455H |

| 18 | 13 | c.1828C>T | p.Q610X | 66 | 43 | c.7387C > T | p.E2463X | 114 | 60 | c.10384C > T | p.E3462X |

| 19 | 15 | c.2291C>A | p.S764X | 67 | 44 | c.7429C > T | p.Q2463X | 115 | 61 | c.10426C > T | p.Q3462X |

| 20 | 16 | c.2578 + 1 + T.C | p.A2639TfsX19 | 68 | 44 | c.7502G > C | p.R2501P | 116 | 61 | c.10441C > T | p.R358X |

| 21 | 17 | c.2686_2689dup | p.E897GfsX4 | 69 | 44 | c.7550_7556delAGCTGCC | p.E2517GfsX52 | 117 | 61 | c.10555G > C | p.G3519R |

| 22 | 18 | c.2772delC | p.L925X | 70 | 44 | c.7561_7573delCCAGCGGGGCCCG | p.2521GfsX46 | 118 | 62 | c.10615C > T | p.R3539C |

| 23 | 19 | c.3036_3041delAGCG | p.V1014LfsX20 | 71 | 45 | c.7624T > C | p.W2542A | 119 | 62 | c.10616G > A | p.R3539H |

| 24 | 23 | c.3484C>T | p.Q1162X | 72 | 45 | c.7778C > T | p.G2593E | 120 | 62 | c.10813G > A | p.D3605N |

| 25 | 24 | c.3712G>T | p.E1238X | 73 | 47 | c.7888A > T | p.R2630W | 121 | 62 | c.10815delT | p.P3606HfsX23 |

| 26 | 25 | c.3905delT | p.L1302RfsX19 | 74 | 47 | c.7897_7902delAGAG | p.E2633AfsX18 | 122 | 65 | c.11308A > G | p.S3770G |

| 27 | 26 | c.4348C>T | p.Q1450X | 75 | 47 | c.7914_7915insA | p.R2639TfsX19 | 123 | 65 | c.11428_11434delACTCA | p.N3810SfsX21 |

| 28 | 26 | c.4355 + 1G>A | p.I1855NfsX5 | 76 | 47 | c.7915C > T | p.R2639X | 124 | 66 | c.11528C > T | p.S3843L |

| 29 | 27 | c.4360C>T | p.R1454X | 77 | 48 | c.8012A > G | p.Q2701A | 125 | 68 | c.11583C > A | p.S3861R |

| 30 | 27 | c.4361G>A | p.R1454Q | 78 | 48 | c.8029C > T | p.R2677X | 126 | 69 | c.12009G > A | p.W4003X |

| 31 | 28 | c.4660G>T | p.E1554X | 79 | 48 | c.8030G > A | p.R2677Q | 127 | 70 | c.12107G > A | p.W4036X |

| 32 | 29 | c.4830dup | p.W1611MfsX47 | 80 | 48 | c.8092_8097delGTGGAC | p.V2698_D2699del | 128 | 70 | c.12265C > T | p.E4089X |

| 33 | 29 | c.4837C>T | p.E1613X | 81 | 48 | c.8141delA | p.N2714MfsX30 | 129 | 71 | c.12397G > T | p.E4133X |

| 34 | 29 | c.4879C>T | p.Q1613X | 82 | 48 | c.8147T > C | p.I2716T | 130 | 72 | c.12614G > T | p.G4205V |

| 35 | 31 | c.5034C>A | p.C1678X | 83 | 48 | c.8167C > T | p.Q2723X | 131 | 72 | c.12617G > A | p.W4206X |

| 36 | 31 | c.5130A>C | p.K1710N | 84 | 48–50 | Loss of heterozygosity | Not available | 132 | 72 | c.12705G > T | p.K4235N |

| 37 | 31 | c.5130_5131insA | p.R1711TfsX36 | 85 | 49 | c.8314C > T | p.R2772X | 133 | 74 | c.12813G > A | p.W4271X |

| 38 | 31 | c.5146C>T | p.R1716W | 86 | 49 | c.8383C > T | p.R2795X | 134 | 75 | c.13194_13197delCAGA | p.D4398EfsX16 |

| 39 | 31 | c.5147G>T | p.R1716L | 87 | 49 | c.8396G > C | p.R2799P | 135 | 76 | c.13426C > T | p.R4476X |

| 40 | 31 | c.5172A>C | p.K1710N | 88 | 49 | c.8404C > T | p.Q2802X | 136 | 76 | c.13458dupT | p.? |

| 41 | 31 | c.5177T>C | p.L1726P | 89 | 49 | c.8440_8447delGAACCAAA | p.2814fsX1 | 137 | 76 | c.13458_13459insT | p.N4487fsX1 |

| 42 | 32 | c.5281C>T | p.R1761X | 90 | 51 | c.8498G > A | p.A2833H | 138 | 77 | c.13486C > T | p.R4496X |

| 43 | 32 | c.5367delT | p.N1790IfsX14 | 91 | 50 | c.8485G > T | p.V2829F | 139 | 78 | c.13595G > T | p.G4532V |

| 44 | 32 | c.5482C>T | p.Q1828X | 92 | 50 | c.8497C > T | p.R2833C | 140 | 78 | c.13633T > C | p.W4545R |

| 45 | 33 | c.5545G>A | p.A1849T | 93 | 50 | c.8497C > G | p.R2833G | 141 | 79 | c.13729G > A | p.R4577X |

| 46 | 33 | c.5557A>T | p.K1853X | 94 | 50 | c.8498G > A | p.R2833H | 142 | 79 | c.13760A > G | p.Y4587C |

| 47 | 33 | c.5563dupA | p.I1855NfsX6 | 95 | 50 | c.8528T > C | p.F2843S | 143 | 79 | c.13778C > T | p.T4593M |

| 48 | 33 | c.5563_5564insA | p.I1855X | 96 | 50 | c.8642C > G | p.A2881G | 144 | 79 | c.13837delG | p.V4613X |

3. Discussion

For the proband in this study, NGS detected dual compound heterozygous mutation sites in DNAH5 exon regions: c.4360C>T and c.9346C>T, among which c.4360C>T has been reported as pathogenic in HGMDpro database,[8] and c.9346C>T has been classified as pathogenic by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.[10] Both of them are stop mutations, suggesting that these 2 gene mutations directly cause clinical manifestations of the proband. Although nasal nitric oxide, high-speed digital video imaging and immunofluorescence microscopy were not carried out due to limited laboratory conditions, symptoms, signs, lung function, high-resolution CT scan, TEM, and NGS all supported the diagnosis of Katargener syndrome in this proband.

These 2 heterozygous mutations of the proband were inherited from his parents. However, his parents and younger brother with single-gene heterozygous mutation presented with no relevant clinical manifestations, suggesting that PCD induced by dual-allele compound heterozygous mutation in DNAH5 exon probably follows the autosomal recessive inheritance law,[11] which is determined by 1 pathogenic gene and functions jointly by several modified genes.[12] Zhang et al[13] reported a 48-year-old woman with a single mutation of DNAH5 [c.9286C>T(p.R3096X)] complicated with a dual-allele heterozygous missense mutation of DNAH11, which led to Kartagener syndrome and overlapped non-ciliated moyamoya syndrome. In our study, although the parents and younger brother with single gene heterozygous mutation developed no relevant clinical manifestations, the ciliary function may have been affected to certain extent, which can still maintain relatively normal organ function.

The proband developed mixed ventilation dysfunction and positive bronchodilation test. No abnormal changes, such as hearing loss, retinitis pigmentosa, polycystic kidney, hydrocephalus, abnormal development of spleen, growth disorder and gastroesophageal reflux were found in the proband of our study. Approximately 30% of PCD patients have normal cilia on TEM, which can partly explain why no evident 9 + 2 structural abnormality was observed under TEM in the proband.

In the present study, the proband was confirmed to have MP infection during each admission to our hospital, whereas S pneumoniae was cultured in only 1 testing, which was consistent with the possibility of mixed infection reported by Xu et al,[14] whereas inconsistent with the findings of Noone et al[15] that the most common pathogens causing lung infection in PCD patients were Haemophilus influenzae, S pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, etc.

4. Study limitations

Due to the small sample size, the findings in this single-case report remain to be validated by subsequent clinical trials with larger sample size.

5. Conclusion

For suspected PCD patients, TEM and NGS should be performed for accurate diagnosis. Prompt prevention and treatment may delay the incidence of bronchiectasis and improve clinical prognosis.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yu Shi, Qihong Lei, Qing Han.

Data curation: Yu Shi, Qihong Lei, Qing Han.

Investigation: Yu Shi, Qihong Lei, Qing Han.

Methodology: Yu Shi, Qihong Lei, Qing Han.

Writing – original draft: Yu Shi, Qihong Lei, Qing Han.

Writing – review & editing: Yu Shi, Qihong Lei, Qing Han.

Abbreviations:

- NGS

- next-generation sequencing

- OMIM

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man

- PCD

- primary ciliary dyskinesia

- TEM

- transmission electron microscope

- WBC

- white blood cell

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

How to cite this article: Shi Y, Lei Q, Han Q. Dual-allele heterozygous mutation of DNAH5 gene in a boy with primary ciliary dyskinesia: A case report. Medicine 2023;102:52(e36271).

Contributor Information

Yu Shi, Email: ft551@163.com.

Qihong Lei, Email: leiqihong@hotmail.com.

References

- [1].Kurkowiak M, Ziętkiewicz E, Witt M. Recent advances in primary ciliary dyskinesia genetics. J Med Genet. 2015;52:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bush A, Chodhari R, Collins N, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: current state of the art. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:1136–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Heuser T, Raytchev M, Krell J, et al. The dynein regulatory complex is the nexin link and a major regulatory node in cilia and flagella. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:921–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Davis SD, Ferkol TW, Rosenfeld M, et al. Clinical features of childhood primary ciliary dyskinesia by genotype and ultrastructural phenotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:316–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kano G, Tsujii H, Takeuchi K, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identification of novel DNAH5 mutations in a young patient with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:5077–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Linck RW, Chemes H, Albertini DF. The axoneme: the propulsive engine of spermatozoa and cilia and associated ciliopathies leading to infertility. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:141–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ellerman A, Bisgaard H. Longitudinal study of lung function in a cohort of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:2376–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wang K, Chen X, Guo CY, et al. Cilia ultrastructural and gene variation of primary ciliary dyskinesia: report of three cases and literatures review. Chin J Pediatr. 2018;56:134–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Olbrich H, Häffner K, Kispert A, et al. Mutations in DNAH5 cause primary ciliary dyskinesia and randomization of left-right asymmetry. Nat Genet. 2002;30:143–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Meeks M. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: a genome-wide linkage analysis reveals extensive locus heterogeneity. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Li Y, Yagi H, Onuoha EO, et al. DNAH6 and its interactions with PCD genes in heterotaxy and primary ciliary dyskinesia. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang L, Feng X, Zhang J, et al. Co-occurrence of Moyamoya syndrome and Kartagener syndrome caused by the mutation of DNAH5 and DNAH11: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2020;20:314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Xu BP, Shen KL, Hu YH, et al. Clinical characteristics of primary ciliary dyskinesia in children. Chin J Pediatr. 2008;46:618–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Noone PG, Leigh MW, Sannuti A, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: diagnostic and phenotypic features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:459–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]