Abstract

Most antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) act by killing bacterial cells. However, there is little information regarding the required interaction time between AMPs and bacterial cells to exert the bactericidal activity. One of the causes of the bactericidal activity is considered to be cell membrane damage, although little direct evidence is available. Here, we investigated the relationship between AMP-induced cell membrane damage in Escherichia coli and AMP-induced cell death at the single-cell level. Magainin 2, lactoferricin B, and PGLa were selected as the AMPs. First, we examined the interaction time (t) of AMPs with cells required to induce cell death using the single-cell analysis. The fraction of microcolonies containing only a single cell, Psingle (t), which indicates the fraction of dead cells, increased with time to reach ∼1 in a short time (≤5 min). Then, we examined the interaction between AMPs and single cells using confocal laser scanning microscopy in the presence of membrane-impermeable SYTOX green. Within a short time interaction, the fluorescence intensity of the cells due to SYTOX green increased, indicating that AMPs induced cell membrane damage through which the dye entered the cytoplasm. The fraction of cells in which SYTOX green entered the cytoplasm among all examined cells after the interaction time (t), Pentry (t), increased with time, reaching ∼1 in a short time (≤5 min). The values of Psingle (t) and Pentry (t) were similar at t ≥ 3 min for all AMPs. The bindings of AMPs to cells were largely reversible, whereas the AMP-induced cell membrane damages were largely irreversible because SYTOX green entered the cells after dilution of AMP concentration. Based on these results, we conclude that the rapid, substantial membrane permeabilization of cytoplasmic contents after a short interaction time with AMPs and the residual damage after dilution induce cell death.

Significance

We investigated the relationship between antimicrobial peptides (AMPs)-induced bactericidal activity and cell membrane damage of single Escherichia coli cells at the single-cell level. We examined the AMP-induced cell death using the single-cell analysis developed by us. The fraction of dead cells among all cells, Psingle(t), increased with time, reaching ∼1 in a short time (≤5 min). The interaction of AMPs with single cells induced the entry of SYTOX green into the cytoplasm in less than 5 min, indicating cell membrane damage. The fraction of cells that SYTOX green entered among all cells, Pentry (t), increased with time. The values of Psingle (t) and Pentry (t) are similar, indicating that the AMP-induced cell membrane damage results in cell death.

Introduction

The number of multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria, which cannot be killed even using multiple antibiotics, has increased greatly (1,2). To prevent infections by MDR bacteria, the development of new types of antibiotics is indispensable. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are proposed as one such candidate (3,4,5). AMPs have microstatic activity (i.e., to suppress the proliferation of bacteria and fungi) and microbicidal activity (i.e., to kill bacteria and fungi) (3,6,7,8,9,10,11). Most AMPs are positively charged, short peptides. To date, more than 3000 AMPs have been found and isolated (12). AMPs act in bacterial cells in various manners, including damaging the cell membranes (13,14) and entering the cytoplasm (15,16) to bind to DNA and/or important proteins (17).

The bacteriostatic activity of AMPs and antibiotics has been estimated using the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), and their bactericidal activity has been estimated using the minimum bactericidal concentration and time-kill assay (18,19,20). Recently, we developed a method to estimate the bacteriostatic activity and bactericidal activity of AMPs and antibiotics at the single-cell level (i.e., the single-cell analysis of bacteriostatic and bactericidal activities) (21). In this method, we monitor the proliferation of single bacterial cells on agar in a microchamber using optical microscopy and obtain the distribution of the number of cells per microcolony originating from a single cell as a function of incubation time. In method A, we incubate single cells with various concentrations of AMPs and antibiotics and obtain the distribution of the number of cells per microcolony after a specific incubation time. Method A provides information on the bacteriostatic activities. On the other hand, in method B, first bacterial cells are mixed with various concentrations of AMPs and antibiotics in a suspension for various interaction times, and then they are diluted to decrease the concentrations appropriately. The diluted suspension is incubated on agar in a chamber for 3 h, and then the distribution of the number of cells per microcolony is determined as a function of incubation time. Method B provides information on the bactericidal activities.

The interaction of AMPs with single bacterial cells has recently been examined using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). Human cathelicidin LL-37 and lactoferricin B (LfcinB) induced rapid leakage of cytoplasmic contents, such as pre-loaded water-soluble fluorescent probes, indicating that AMPs damage bacterial cell membranes by pore formation and local rupture (13,14). After a short interaction period (1−5 min), the fluorescent probes completely leaked out, given that the fluorescence intensity of the cell became 0 (14). However, we do not know if the cells die within this short interaction time and thus we do not know the length of time for cell membrane damage required to induce bactericidal activity. In other words, is only a brief leakage of the internal contents induced by AMPs responsible for the bactericidal activity or is relatively prolonged damage to cell membrane (such as stable pore formation) required?

There is little information regarding the interaction time of AMPs with bacterial cells required to induce bactericidal activity. Moreover, the relationship between the AMP-induced cell membrane damage and cell death has not been revealed experimentally. In this report, we first examined the interaction time of AMPs required to induce bacterial cell death (Escherichia coli cells) using the single-cell analysis (method B) (21). Then, to address the above questions, we investigated the relationship between AMP-induced cell membrane damage in bacterial cells and AMP-induced cell death at the single-cell level. Magainin 2 (Mag), LfcinB, and PGLa were selected as the AMPs, as it is well known that these AMPs induce damage (such as pore formation) in the membranes of lipid vesicles such as large unilamellar vesicles and giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs), resulting in leakage of internal contents from the vesicles (22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30). To reveal the AMP-induced cell membrane damages of E. coli cells at the single-cell level, we examined the entry of membrane-impermeable SYTOX green into the cytoplasm of single cells using CLSM as a function of exposure time (13). Using these results, we examined the relationship between the interaction time required for bactericidal activity of AMPs and that required for AMP-induced damage in the cell membrane. Finally, we examined the reversibility of the binding of AMPs to the cells and that of AMP-induced damage in the cell membrane. Based on these results, we conclude that the rapid, substantial membrane permeabilization of cytoplasmic contents after short exposure to AMPs and the residual damage after dilution induce cell death.

Materials and methods

The supporting material (section S1) provides the materials and methods.

Results and discussion

Single-cell analysis of AMP-induced death of E. coli cells

First, we monitored the proliferation of single E. coli cells on an agar medium by observing these cells using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy and counted the number of cells in each microcolony. After 3-h incubation at 37°C, most microcolonies had more than 30 cells and the mean number of cells per microcolony was 66 (section S2 in supporting material). The analysis of the time course of the average number of cells per microcolony provided the generation time τ of 27 min (Fig. S1 D). Next, using the single-cell analysis (method A) (21), we determined the MIC of the AMPs under the conditions of the experiments: 50 μM for Mag, 3.0 μM for LfcinB, and 32 μM for PGLa (section S3 and Fig. S2).

To investigate the effect on cell death of the interaction time of AMP with E. coli cells, we performed the single-cell analysis (method B) developed recently by our lab (21). In method B, after interaction of AMP with cells in EZ medium for a specific time, t, the cell suspension was diluted 10 times with fresh medium, ensuring that the final AMP concentration was sufficiently low so that AMP no longer had a bacteriostatic activity (Fig. S2). After dilution, an aliquot of the diluted suspension was transferred onto agar medium in the chamber and incubated at 37°C for 3 h, and the number of cells per microcolony originating from a single cell, N(t), was determined. Under these conditions, N(t) has a wide distribution from 1 to ∼100, providing the information on the capacity of single cells to proliferate. If a cell cannot proliferate, N(t) becomes one, which means that the cell is dead because it cannot proliferate in the presence of low concentrations of AMPs that do not have a bacteriostatic activity. The number of microcolonies containing only a single cell increased as the interaction time (t) with AMPs increased. We obtained the fraction of microcolonies containing only one cell among all the microcolonies as a function of the interaction time, t (i.e., Psingle (t)), which represents the fraction of dead cells after the interaction of AMPs with single cells for a specific time, t (21).

First, we examined the effect of the interaction time of Mag of E. coli cells on cell death. For this experiment, we selected two Mag concentrations, 50 μM (i.e., MIC) and 25 μM (i.e., 1/2 MIC), which inhibit the proliferation of 100% of cells and 50%−60% of cells determined by method A, respectively (Fig. S2 A). The result of 3-min interaction of 50 μM Mag with E. coli cells in a suspension showed that 188 of a total 208 microcolonies were composed of single cells, with the remainder consisting of two cells. Thus, Psingle (3 min) was 0.90. The mean ± SD of Psingle (3 min) under the same conditions was 0.90 ± 0.04 (four independent experiments, i.e., N = 4). Fig. 1 A and B show the distribution of N(t) for the cells that interacted with 50 and 25 μM Mag for a specific time (t), respectively. In the case of 50 μM Mag, the short-time (less than 3 min) interaction induced the death of most cells, and the residual cells could not proliferate significantly. On the other hand, in the case of 25 μM Mag, the 5-min interaction induced the death of a half of the total cells, but the fraction of microcolonies containing more than 20 cells was high (i.e., 0.28) and there were a few microcolonies containing more than 60 cells (Fig. 1 B). Fig. 1 C shows that Psingle increased with interaction time 50 μM Mag (e.g., 0.78 ± 0.09 at 1 min, 0.95 ± 0.02 at 5 min), reaching 1.0 at 10 min (N = 3−4). Here, Psingle = 1.0 indicates that all microcolonies are composed of only single cells, indicating that all cells died after 10-min interaction. Next, we examined the effect of 25 μM Mag. Psingle increased slowly with time (e.g., 0.33 ± 0.10 at 1 min, 0.52 ± 0.09 at 5 min), reaching 0.55 ± 0.08 at 10 min (N = 3) (Fig. 1 C). The results of Fig. 1 B and C suggest that the surviving cells after 5-min interaction with 25 μM Mag, which is ∼50% of the total cells, can proliferate significantly.

Figure 1.

Effect of interaction time of AMPs with E. coli cells on its bactericidal activity. A cell suspension was mixed with AMP solution in EZ medium, incubated for a specific time (t), then the suspension was diluted 10 times with fresh medium. After 3-h incubation in the chamber, the number of cells per microcolony, N(t), was counted. (A−C) Mag. The distributions of N(t) for the cells that interacted with 50 μM (A) and 25 μM (B) Mag for a specific time (t). (green □) 1 min, (red Δ) 3 min, and (blue ○) 5 min. (A, B, D, E, G, and H) Underlined 20 and 30 mean 21−29 cells and 30−70 cells, respectively. (C) The dependence of the fraction of microcolonies containing only a single cell, Psingle, on the interaction time with Mag; (green ▪) 50 μM and (red •) 25 μM. (D−F) LfcinB. The distributions of N(t) for the cells after interaction with 3.0 μM (D) and 1.5 μM (E) LfcinB for a specific time (t); (red Δ) 3 min, (blue ○) 5 min, and (brown ◊) 10 min. (F) The dependence of Psingle on the interaction time with LfcinB; (green ▪) 3.0 μM and (red •) 1.5 μM. (G−I) PGLa. The distributions of N(t) for the cells after interaction with 32 μM (G) and 8 μM PGLa (H) for a specific time (t); (green □) 1 min, (red Δ) 3 min, and (blue ○) 5 min (I) The dependence of Psingle on the interaction time with PGLa; (green ▪) 32 μM and (red •) 8 μM. (A, B, D, E, G, and H) The mean values and SDs of the fraction of microcolony (N = 3) are shown. (C, F, and I) The mean values and SDs of Psingle (N = 3−4) are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Next, we examined the effect of the interaction time of LfcinB with cells on cell death. For this experiment, we selected two LfcinB concentrations, 3.0 μM (i.e., MIC) and 1.5 μM (i.e., 1/2 MIC), which inhibit the proliferation of 100% of cells and 50%−60% of cells determined by method A, respectively (Fig. S2 B). Fig. 1 D and E show the distribution of N(t) for the cells that interacted with 3.0 and 1.5 μM LfcinB for a specific time (t), respectively. In the case of 3.0 μM LfcinB, the short-time (less than 5 min) interaction induced the death of most cells, and the other cells could not proliferate significantly. On the other hand, in the case of 1.5 μM LfcinB, the 10-min interaction induced the death of a half of the total cells, but the fraction of microcolonies containing more than 20 cells was high (Fig. 1 E). This result indicates that, in the interaction of low concentration of LfcinB, some cells died immediately but the other cells proliferated significantly. Fig. 1 F shows that Psingle increased with interaction time with 3.0 μM LfcinB (e.g., 0.26 ± 0.05 at 1 min, 0.75 ± 0.07 at 5 min), reaching ∼1.0 (0.98 ± 0.02) at 10 min (N = 3). This increase of LfcinB over time is smaller than that of Mag, indicating that the rate of cell death induced by LfcinB is lower than that induced by Mag. In the interaction with 1.5 μM LfcinB, Psingle increased slowly with time (e.g., 0.14 ± 0.05 at 1 min, 0.41 ± 0.12 at 5 min) and reached 0.53 ± 0.05 at 10 min (N = 3) (Fig. 1 F).

Finally, we examined the effect of PGLa interaction time with cells on cell death. For this experiment, we selected two PGLa concentrations of 32 μM (i.e., MIC) and 8.0 μM (i.e., 1/4 MIC), which inhibit the proliferation of 100% of cells and 50%−60% of cells determined by method A, respectively (Fig. S2 C). Fig. 1 G and H show the distribution of N(t) for the cells that interacted with 32 and 8 μM PGLa for a specific time (t), respectively. Fig. 1 I shows that Psingle increased with interaction time with 32 μM PGLa (e.g., 0.74 ± 0.05 at 1 min, 0.87 ± 0.02 at 3 min), reaching ∼1.0 (0.99 ± 0.02) at 5 min (N = 3). This increase of PGLa over time is similar to that of Mag, indicating that the rate of cell death induced by PGLa is similar to that induced by Mag. In the interaction with 8.0 μM PGLa, Psingle increased slowly with time (e.g., 0.21 ± 0.04 at 1 min, 0.39 ± 0.03 at 5 min), reaching 0.58 ± 0.11 at 10 min (N = 3), whereas the fraction of microcolonies containing more than 20 cells was high (0.45) (Fig. 1 H).

AMP-induced entry of SYTOX green into the cytoplasm of single E. coli cells and its relationship with AMP-induced cell death

To reveal AMP-induced damage of the cell membrane (such as pore formation) of single E. coli cells, we examined the entry of a water-soluble fluorescent probe, SYTOX green, into the cytoplasm of cells. The fluorescence intensity (FI) of SYTOX green is enhanced after its binding to nucleic acids such as DNA, and, thus, it has been used as a marker of cell death, as SYTOX green cannot permeate the cell membrane of live cells but can permeate the damaged cell membrane of dead cells (31,32,33). Since the increase in FI of SYTOX green indicates cell membrane damage through which this dye enters the cytoplasm, the entry of SYTOX green into the cytoplasm of bacterial cells has also been used to detect AMP-induced cell membrane damage in bacteria (13,29).

First, we investigated the interaction of Mag with single cells in the presence of 1.0 μM SYTOX green using CLSM. For this purpose, Mag in medium containing 1.0 μM SYTOX green was provided continuously to the neighborhood of a single cell through a micropipette, and the increase in FI of the cytoplasm was determined as a function of time. Fig. 2 A shows a typical result of the interaction of 50 μM Mag with a single cell. At the beginning of the interaction, the total cell FI of due to SYTOX green was very low and remained constant for a long time, and from 196 s the FI increased a little slowly with time and then rapidly increased from 218 s to reach a steady-state value (Fig. 2 A and B). Thus, the onset time of the rapid increase in FI is 218 s. This rapid increase in FI shows that the SYTOX green entered the cytoplasm and started to bind to DNA from 218 s, indicating that Mag induces cell membrane damage (e.g., pore formation) through which SYTOX green enters the cytoplasm. The same experiments for the interaction of Mag with single cells were performed using 52 cells. A similar rapid increase in FI due to SYTOX green was observed in most cells but the onset time of the increase in FI differed (Fig. 2 C). This result indicates that Mag induced damage at different times in each cell membrane. As a measure of the rate of Mag-induced damage in the cell membrane, we used here the fraction of cells in which SYTOX green enters the cytoplasm among all examined cells through the damaged cell membrane after a specific interaction time (t) with an AMP (briefly, the fraction of entry), Pentry (t). In other words, Pentry (t) indicates the fraction of cells whose cell membrane is damaged by the interaction with AMP. We conducted three independent experiments for 50 μM Mag and obtained the mean value and SD of Pentry (t). Fig. 2 E shows that Pentry (t) increased with time (e.g., 0.38 ± 0.15 at 1 min, 0.88 ± 0.07 at 2 min), reaching 0.99 ± 0.01 at 5 min (N = 3, total of 193 cells). In the interaction of 25 μM Mag, a similar Mag-induced increase in FI of single cells was observed (Fig. 2 D). Pentry (t) increased slowly with time (Fig. 2 E) (e.g., 0.09 ± 0.08 at 1 min, 0.27 ± 0.11 at 2 min), reaching 0.53 ± 0.06 at 5 min (N = 4, total of 257 cells).

Figure 2.

Mag-induced entry of SYTOX green into the cytoplasm of single E. coli cells. CLSM studies. (A) The interaction of 50 μM Mag with a single cell at 25°C. CLSM images of SYTOX green (1) and DIC (2) images. The interaction time (t) is indicated above each image. Bar, 2 μm. (B) The time course of change in FI of SYTOX green in the cell shown in (A). (C) Other examples of the time course of change in FI of several single cells interacting with 50 μM Mag under the same conditions as in (A). (D) The time course of change in FI of SYTOX green in several single cells interacting with 25 μM Mag. (E) The dependence of the fraction of entry, Pentry (t), on the interaction time: (green □) 50 μM and (red ○) 25 μM Mag. The mean values and SDs of Pentry (t) (N = 3−4) are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

To elucidate the relationship between the AMP-induced entry of SYTOX green into the cytoplasm of single cells and the AMP-induced damage in their cell membrane, we examined the interaction of AMPs with single live E. coli cells containing a fluorescent probe, calcein, in their cytoplasm using the same method reported previously (14) (section S4). The 50 μM Mag induced rapid leakage of calcein through the damage in the cell membrane such as pore formation, and the onset time of rapid leakage differed in cells. The time courses of the fraction of Mag-induced leaked cells among all examined cells (Pleak (t)) and that of Pentry (t) of SYTOX green are similar (Fig. S3 D), indicating that the onset time of Mag-induced rapid increase in FI due to SYTOX green is almost the same as the onset time of Mag-induced cell membrane damage. Therefore, the results of the CLSM detection of SYTOX green entry to the cytoplasm of single cells can provide information on the time point of Mag-induced cell membrane damage in single cells. Here, we adopted the method of SYTOX green entry instead of the calcein leakage for the detection of cell membrane damage because we can examine a larger number of cells in the SYTOX green experiment than that in the calcein leakage experiment due to the limited fraction of calcein-labeled cells and we do not have to consider the effect of loading of calcein in the cytoplasm. In flow cytometry experiments, it was reported that SYTOX green binds to the surface of intact E. coli cells, inducing low FI due to SYTOX green, although its mechanism is unknown (31,33). In the above experiments, SYTOX green was mixed with the cells more than 15 min before exposure to AMP; thus, the initial, constant low FI corresponds to the FI due to the binding of SYTOX green with the surface of intact cells. Fig. 2 C shows that the FI of single E. coli cells due to SYTOX green increased a little before the rapid increase. This may be due to an increase in binding of SYTOX green to the surface of intact cells, although currently its mechanism is unknown.

Next, we examined the relationship between Psingle (t) obtained using the single-cell analysis (Fig. 1 C) and Pentry (t) determined by CLSM (Fig. 2 E). Fig. 3 A shows that at the values of Psingle (t) and Pentry (t) are almost the same at t ≥ 3 min for 25 μM and 50 μM Mag, indicating that Mag-induced cell membrane damage induces cell death. At a short interaction time (1 min), the values of Psingle (t) are larger than those of Pentry (t). In the CLSM experiments of SYTOX green entry, some time is required until the Mag concentration near the E. coli cells reaches a steady state after starting the addition of Mag solution from the micropipette, whereas, in the single-cell analysis, the Mag concentration near the cells rapidly reached a steady state. This can reasonably explain the discrepancy between Psingle (t) and Pentry (t) with a short interaction time.

Figure 3.

AMP-induced cell membrane damage in E. coli cells and its relationship with the AMP-induced cell death at the single-cell level. (A) Mag-induced entry of SYTOX green into the cells and Mag-induced bactericidal activity. The interaction time dependence of Pentry: 50 μM (red □) and 25 μM (red ○). The interaction time dependence of Psingle: 50 μM (blue ▪) and 25 μM (green •). (B) LfcinB-induced entry of SYTOX green into the cells and LfcinB-induced bactericidal activity. The interaction time dependence of Pentry: 3.0 μM (red □) and 1.5 μM (red ○). The interaction time dependence of Psingle: 3.0 μM (blue ▪) and 1.5 μM (green •). (C) PGLa-induced entry of SYTOX green into the cells and PGLa-induced bactericidal activity. The interaction time dependence of Pentry: 32 μM (red □) and 8.0 μM (red ○). The interaction time dependence of Psingle: 32 μM (blue ▪) and 8.0 μM (green •). (D) LfcinB4-9-induced entry of SYTOX green into the cells and LfcinB4-9-induced bactericidal activity. The interaction time dependence of Pentry: 60 μM (red □) The interaction time dependence of Psingle: 60 μM (blue ▪) and 40 μM (green •). In all panels, the mean values and SDs of Pentry and Psingle (N = 3−4) are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Second, we examined the LfcinB-induced cell membrane damage in single cells using the same method (section S5). The interaction of 3.0 μM LfcinB with single cells induced a rapid increase in FI due to SYTOX green, but the onset time of the increase in FI differed (Fig. S4 C), indicating that LfcinB induced damage at different times in each cell membrane. Fig. 3 B shows that Pentry (t) increased with time, reaching 1.0 at 7 min (N = 3, total of 169 cells). In the interaction of 1.5 μM LfcinB with single cells, a similar rapid increase in FI due to SYTOX green was also observed in some of cells (Fig. S4 D), but Pentry (t) increased slowly with time (Fig. 3 B). The values of Psingle (t) and Pentry (t) are similar at t ≥ 3 min for 1.5 and 3.0 μM LfcinB (Fig. 3 B), indicating that LfcinB-induced cell membrane damage induces cell death. At a short interaction time (1 min), the values of Psingle (t) were larger than those of Pentry (t), which is similar to the case of Mag.

Finally, we examined the PGLa-induced cell membrane damage in single cells using the same method (section S6). The interaction of 32 μM PGLa with single cells induced a rapid increase in FI due to SYTOX green, but the onset time of the increase in FI differed (Fig. S5 C), indicating that PGLa induced damage at different times in each cell membrane. Fig. 3 C shows that Pentry (t) increased with time, reaching ∼1.0 (1.00 ± 0.01) at 5 min (N = 3, total of 201 cells). In the interaction of 8.0 μM PGLa with single cells, a similar rapid increase in FI due to SYTOX green was also observed in some of cells (Fig. S5 D), but Pentry (t) increased slowly with time (Fig. 3 C). The values of Psingle (t) and Pentry (t) are similar at t ≥ 3 min for both PGLa concentrations (Fig. 3 C), indicating that PGLa-induced cell membrane damage induces cell death. At a short interaction time (1 min), the values of Psingle (t) were larger than those of Pentry (t), which is similar to the case of Mag.

As a control experiment, we examined the interaction of single E. coli cells with another type of AMP, which does not induce membrane damage and enter the cytosol to bind DNAs and proteins (i.e., cell-penetrating peptide (CPP)-type AMPs) (15,17). Here, we selected LfcinB4-9, a six-residue AMP, which has been demonstrated as the CPP-type AMP (16). The MIC of LfcinB4-9 under this condition was determined as 40 μM using the standard method (29). For this experiment, we selected two LfcinB4-9 concentrations of 40 μM (i.e., MIC) and 60 μM (i.e., 1.5 MIC). Fig. 3 D shows that, in the interaction with 60 μM LfcinB4-9, Psingle increased gradually with time (e.g., 0.30 ± 0.01 at 10 min, 0.73 ± 0.08 at 20 min), reaching ∼1.0 (0.98 ± 0.05) at 60 min (N = 3). In the interaction with 40 μM LfcinB4-9, Psingle increased more slowly with time, reaching 0.51 ± 0.01 at 60 min (N = 3) (Fig. 3 D). These results show that, after the generation time of the cell (27 min), the values of Psingle were smaller than 1, and a much longer time was required until Psingle reached 1, which are greatly different from those obtained in the interactions with Mag, LfcinB, and PGLa. The interaction of 60 μM LfcinB4-9 with single cells induced no increase in FI due to SYTOX green up to 20-min interaction, and, thus, Pentry = 0 (Figs. S6 and 3 D), indicating that LfcinB4-9 did not induce cell membrane damage at t ≤ 20 min. On the other hand, after 20-min interaction with 60 μM LfcinB4-9, 73% of the cells were dead since Psingle = 0.73 (Fig. 3 D). These results clearly indicate that LfcinB4-9 kills the cells without damaging the cell membrane.

Reversibility of binding of AMPs to E. coli cell membranes

When AMPs interact with E. coli cells and induce cell membrane damage, many AMP molecules bind to the cell membrane and the outer membrane. It is reported that the fluorescent probe-labeled AMP (e.g., carboxyfluorescein (CF)-labeled AMP (CF-AMP)) can be used to estimate the binding of AMPs to the membranes of GUVs (25,30) and E. coli cells and their spheroplasts (16). In these experiments, we have to use a mixture of a low concentration of CF-AMPs and higher concentrations of label-free AMPs, because generally the rate of damage of membrane, such as pore formation induced by fluorescent probe-labeled peptides, is larger than that induced by label-free peptides (34) and the high concentration of fluorescent probe-labeled peptides in the membrane may induce the quenching of fluorescence (35). Thus, we used here 0.20 μM CF-AMPs, which are sufficiently low. To elucidate whether this binding is reversible or not, we examined the interaction of a CF-AMP and label-free AMP mixture with E. coli cells and measured the FI of each cell (as well as the FI of each cell after 10-times dilution) using CLSM.

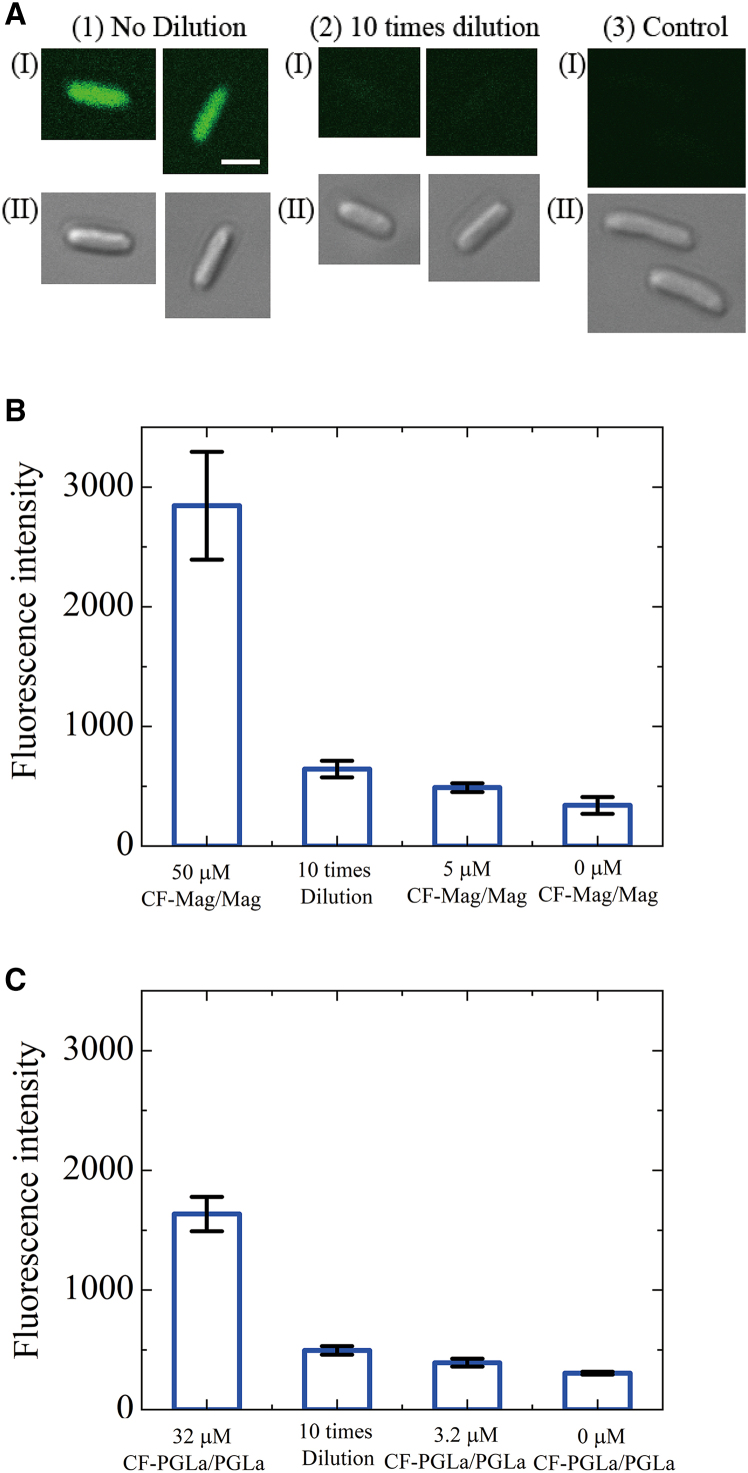

First, we examined the reversibility of Mag binding. After interaction of the CF-Mag and Mag mixture (50 μM total Mag concentration, including 0.20 μM CF-Mag) with cells, the FI of each cell was measured using CLSM. We also measured the FI of each cell after 10-times dilution of the cell suspension after interaction with the 50 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture for 3 min (Fig. 4 A). The mean value and SD of the FI value of each cell exposed to 50 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture and those after 10-times dilution were 2800 ± 500 (N = 4, total of 253 cells) and 640 ± 70 (N = 4, total of 312 cells), respectively (Fig. 4 B; Table S1). On the other hand, the FI of each cell without exposure to CF-Mag/Mag was 340 ± 70 (N = 4, total of 301 cells). We also investigated the interaction of 5.0 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture (containing 0.020 μM CF-Mag), which is 10 times lower than 50 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture, with cells and measured the FI of each cell during the interaction: 490 ± 40 (N = 3, total of 236 cells). Therefore, the FI of cells exposed to 50 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture and then diluted 10 times is somewhat greater than that of cells exposed to 5.0 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture, indicating that some CF-Mag molecules remain in the cells after dilution. Thus, after subtracting the FI of the cells exposed to 5.0 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture, the FIs of each cell during the interaction and after the dilution were 2300 and 150, respectively. Therefore, after the dilution, the FI of each cell decreased by 93%, indicating that the binding of CF-Mag/Mag to the cells was largely reversible; i.e., 93% of the bound CF-Mag/Mag molecules were detached from the membranes and only 7% CF-Mag/Mag remained in the cells.

Figure 4.

Reversible binding of AMPs to E. coli cell membranes. (A) CLSM image of E. coli cells under various conditions. (1) Cells exposed to 50 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture (including 0.20 μM CF-Mag). (2) Ten-times dilution of a cell suspension exposed to 50 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture for 3 min. (3) Cells without exposure to CF-Mag/Mag mixture (control experiment). CLSM images for CF-Mag (I) and DIC images (II) are shown. Bar, 2 μm. (B) The FI of the cells due to CF-Mag measured using CLSM. The cells under various conditions were measured; the cells exposed to 50 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture (the number of examined cells, n = 253), 10-times dilution of the cell suspension exposed to 50 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture for 3 min (n = 312), the cells exposed to 5.0 μM CF-Mag/Mag mixture (n = 236), and the cells without exposure to CF-Mag/Mag mixture (n = 301). (C) The FI of the cells due to CF-PGLa measured using CLSM. The cells under various conditions were measured; the cells exposed to 32 μM CF-PGLa/PGLa mixture (n = 178), 10-times dilution of the cell suspension exposed to 32 μM CF-PGLa/PGLa mixture for 3 min (n = 185), the cells exposed to 3.2 μM CF-PGLa/PGLa mixture (n = 145), and the cells without exposure to CF-PGLa/PGLa mixture (n = 146). (B and C) The mean values and SDs (by error bars) of the FI are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Next, we examined the reversibility of the binding of PGLa with cells (Fig. 4 C; Table S2). The FI of each cell during the interaction with 32 μM CF-PGLa/PGLa mixture (including 0.20 μM CF-PGLa) and after the 10-times dilution (after subtracting the FI of the cells exposed to 3.2 μM CF-PGLa/PGLa mixture) were 1250 and 110, respectively. Therefore, after the dilution, the FI of each cell decreased by 91%, indicating that the binding of CF-PGLa/PGLa to the cells was largely reversible; i.e., 91% of the bound CF-PGLa/PGLa molecules were detached from the membranes and only 9% CF-PGLa/PGLa remained in the cells.

We could not examine the reversibility of LfcinB binding as CF-LfcinB could not be prepared.

Irreversibility of AMP-induced damage in E. coli cell membranes

Here, to elucidate the reversibility of AMP-induced damage of cell membranes, we examined the cell membrane damage after 10-times dilution of cell suspension after interaction with AMP for a specific time (and, as a result, the cell membranes had been damaged) and compared the damage between before and after the dilution. Damage to the cell membrane was estimated by the entry of SYTOX green into the cytoplasm.

First, we examined the effect of dilution on Mag-induced cell membrane damage. For this purpose, after E. coli cells were exposed to a Mag solution in EZ medium (final Mag concentration was 25 μM) for 3 min, and then diluted 10 times with EZ medium and incubated for 10 min. Then, a SYTOX green solution in medium was mixed with the cell suspension at the volume ratio of 1 to 1 and subsequently the cell suspension was transferred into a chamber. The cells were allowed to settle on the coverslip (15 min), then the FI of each cell due to SYTOX green was measured using CLSM. Some cells had a high FI, but the others did not (Fig. 5 A (2)). We determined the threshold FI of the total cell for the entry of SYTOX green for Mag as 400 based on the results shown in Fig. 2 (the maximum intensity of the onset time of the rapid increase in FI). Among the total of 59 cells, the FI values of 35 cells were higher than the threshold FI, and, thus, Pentry (3 min) = 0.59. After three independent experiments, the mean value and SD of Pentry (3 min) was obtained: 0.56 ± 0.03 (N = 3, total of 142 cells). To determine the Pentry (3 min) of the cells after interaction of Mag (without dilution), we used the same method described in section “AMP-induced entry of SYTOX green into the cytoplasm of single E. coli cells and its relationship with AMP-induced cell death.” Among total 62 cells, the FI values of 27 cells were higher than the threshold FI, and, thus, Pentry (3 min) = 0.44 (Fig. 5 A (1)). Three independent experiments provided Pentry (3 min) = 0.41 ± 0.05 (N = 3, total of 198 cells), which agrees with the value in Fig. 2 E. Thus, the fraction of damaged cells after the dilution was a little larger than that before dilution. We performed the same experiments using 50 μM Mag. The Pentry (3 min) values before and after dilution were 0.91 ± 0.07 and 0.93 ± 0.05 (N = 3, total of 184 and 126 cells), respectively, which are almost the same. Both results indicate that Mag-induced cell membrane damage was largely irreversible; i.e., if the cell membrane was damaged during the interaction with Mag, this damage remains after the dilution of Mag solution. Currently, we do not know the cause for a slight increase in the fraction of damaged cells after the dilution of cell suspension exposed to 25 μM Mag.

Figure 5.

Irreversibility of AMP-induced damage in E.coli cell membranes. (A) CLSM image of E. coli cells under various conditions in a SYTOX green solution in EZ medium. (1) Cells exposed to 25 μM Mag for 3 min. (2) Ten-times dilution of a cell suspension exposed to 25 μM Mag for 3 min. CLSM images for SYTOX green (I) and DIC images (II) are shown. Bar, 2 μm. (B) The fraction of entry, Pentry(3 min), of SYTOX green in the cells exposed to Mag under various conditions. The cells exposed to 25 μM Mag, 10-times dilution of a cell suspension exposed to 25 μM Mag for 3 min, the cells exposed to 50 μM Mag for 3 min, and 10-times dilution of a cell suspension exposed to 50 μM Mag for 3 min. (C) The Pentry(3 min) of SYTOX green in the cells exposed to LfcinB under various conditions. The cells exposed to 1.5 μM LfcinB, 10-times dilution of a cell suspension exposed to 1.5 μM LfcinB for 3 min, the cells exposed to 3.0 μM LfcinB, and 10-times dilution of a cell suspension exposed to 3.0 μM LfcinB for 3 min. (D) The Pentry(3 min) of SYTOX green in the cells exposed to PGLa under various conditions. The cells exposed to 8.0 μM PGLa, 10-times dilution of a cell suspension exposed to 8.0 μM PGLa for 3 min, the cells exposed to 32 μM PGLa, and 10-times dilution of a cell suspension exposed to 32 μM PGLa for 3 min. (B–D) The mean values and SDs of Pentry (N = 3) are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

We performed the same experiments using two concentrations of LfcinB and PGLa, which are the same concentrations used in Figs. 1 and 3. We determined the threshold FI values of the total cell for the entry of SYTOX green for LfcinB and PGLa as 350 and 100 based on the results shown in Figs. S4 and S5, respectively. The Pentry after the interaction with these AMPs for 3 min and the Pentry after 10-times dilution of cell suspension after interaction with these AMPs for 3 min were almost the same within experimental errors (but for only 1.5 μM LfcinB, Pentry (3 min) after dilution was a little larger than that before dilution) (Fig. 5 C and D; Tables S4 and S5). These results indicate that LfcinB- and PGLa-induced cell membrane damage were largely irreversible.

In this experiment, we did not compare the FI values of the cells between before and after the dilution because the interaction time of SYTOX green with cells after the dilution (more than 15 min) is much longer than that before the dilution (3 min). Therefore, this method cannot provide the information on the difference of the degree of cell membrane damage (or membrane permeability coefficient) between the cells before and after the dilution.

Currently, the structure of the residual damage in the cell membrane after the dilution is unknown. The amounts of AMPs in the membrane after the dilution were greatly decreased, and it may be difficult to consider that the remaining stable pores composed of AMPs are responsible for the prolonged residual damage. An irreversible change in structure of cell membrane may explain the residual damage, because AMP-induced pores may induce local rupture of the membrane that cannot be closed, as is reported for the interaction of Mag and LfcinB with GUVs comprising E. coli polar lipids (14,36).

General discussion

The study on the interaction of AMPs with single E. coli cells using CLSM revealed that, after a short interaction time, the three AMPs induced damage (such as pore formation) in the cell membrane of single E. coli cells, allowing SYTOX green to enter. The advantage of this method is that we can determine the time point of the AMP-induced cell membrane damage in each cell. The use of other methods, such as fluorescence spectroscopy (29) and flow cytometry (33,37), does not provide us with this information, as the fluorescence spectroscopy provides the average FI of all the cells in a suspension as a function of time and the FI of cells increases greatly after the onset time of increase in FI (as demonstrated in Figs. 2, S4, and S5, the FI is not proportional to the number of damaged cells), whereas flow cytometry provides the FI of each cell at the measurement time, but it cannot monitor the FI of single cells as a function of time. We found that the fraction of entry, Pentry (t), which indicates the fraction of cells with membrane damage, increased with time, depending on the AMP concentration. Pentry (t) at a specific interaction time can be used as a measure of the rate of AMP-induced cell membrane damage at the single-cell level. We demonstrated that the values of Psingle (t) and Pentry (t) are similar at t ≥ 3 min for the three AMPs, indicating that the AMP-induced cell membrane damage (which allows the entry of SYTOX green into the cytosol) causes the cell death.

The comparison between the results shown in Figs. 1 and 3 indicates that the cells in which SYTOX green does not enter the cytoplasm (i.e., the surviving cells after the interaction with AMPs) can proliferate significantly. For example, after 5-min interaction with 25 μM Mag, Psingle = 0.53 and Pentry = 0.52, and, thus, the fraction of surviving cells is 0.47 (Fig. 3 A), and the fraction of microcolony containing 30−70 cells after 3-h incubation was 0.25 (Fig. 1 B), indicating that 53% of the surviving cells proliferated to 30−70 cells. These proliferation rates of the surviving cells after the interaction of AMPs are less than the proliferation rate of the cell in the absence of AMPs (i.e., the fraction of microcolonies containing more than 70 cells is 0.38). These results suggest that the interaction of AMPs with cells may induce small damage in their cell membranes and/or outer membranes even if the cells do not experience the entry of SYTOX green and this small damage may decrease the proliferation rate. It is important to elucidate this phenomenon, which should be resolved in future.

In this report, we found that a short time (5−10 min, which is 19%–37% of the generation time of the cell (τ)) is required for MIC of AMPs (which induce cell membrane damage) to kill all cells, indicating that the time required to kill E. coli cells at MIC of AMPs is not completely the same, but is of the same order. On the other hand, for the CPP-type AMP, a long time (60 min, which is 2.2 times greater than τ) is required to kill all cells. This result indicates that the cell membrane damage is a more efficient method to kill the bacterial cells.

The rapid cell death induced by AMPs can be caused by the following mechanisms. First, AMPs induce cell membrane damage such as pore formation, through which SYTOX green can permeate rapidly, and as a result, substantial membrane permeabilization of the cytoplasmic contents occurs within a short duration, which is one of the important causes for cell death. The 10-times dilution of the cell suspension after exposure to the AMPs induces the dissociation of most AMPs from the cell membrane, but the cell membrane damage largely remains (Fig. 5). Since a large fluorescent probe, SYTOX green, can permeate this damage, it is difficult to retain the gradient of ions across the cell membrane, which is the origin of membrane potential (Δφ). As a result, this damage continues to increase membrane permeability of important compounds in the cytosol and suppress Δφ for a long time. It is reported that membrane potential plays important physiological roles, such as in cell division (38). Thus, the residual enhanced membrane permeability is also one of the causes for cell death.

As described in the section “introduction,” it has been reported that some AMPs, such as LL-37 and LfcinB, induce rapid, substantial leakage of cytoplasmic contents, such as water-soluble fluorescent probes, indicating that AMPs damage bacterial cell membranes (13,14). However, the relationship between the AMP-induced cell membrane damage and cell death is not clearly understood by experimental evidence. This report clearly indicates that the AMP-induced cell membrane damage results in cell death. It was reported that, in the interaction of Mag with an E. coli cell suspension, as the total K+ efflux from all cells increased, cell viability decreased (39). However, the total amount of K+ efflux from all cells is not proportional to the fraction of cells with cell membrane damage, and, thus, it is difficult to conclude that the damage induces the death of each cell directly. On the other hand, in the interaction of some antibiotics (aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones) with E. coli cells, after a 2- to 3-h interaction, cytoplasmic condensation in the cells begins and subsequently membrane permeation of the cytoplasmic contents occurs via membrane damage, which coincides with a loss of cell viability (40).

Conclusions

In this report, we examine the relationship between AMP-induced E. coli cell death and AMP-induced cell membrane damage at the single-cell level. Using single-cell analysis for bactericidal activity, we found that the three AMPs (Mag, LfcinB, and PGLa) induced cell death after a short interaction time. The fraction of microcolonies containing only a single cell, Psingle (t), which indicates the fraction of dead cells, increased with time, depending on the AMP concentration (e.g., at MIC of these AMPs, Psingle (t) reached ∼1 in a short time (≤5 min)). Using the CLSM study on the interaction of AMPs with single cells, we revealed that a short interaction time (≤5 min) is sufficient for these AMPs to induce cell membrane damage in single cells, allowing SYTOX green to enter. We found that, for three AMPs, the values of the fraction of cells with cell membrane damage, Pentry (t), and those of the fraction of dead cells, Psingle (t), are similar at t ≥ 3 min, indicating that the cell membrane damage induced by the interaction with AMPs for a short time induces cell death. In contrast, for a CPP-type AMP (LfcinB4-9), the fraction of dead cells increases significantly without cell membrane damage.

The binding of the three AMPs to cells was largely reversible since the 10-times dilution of the cell suspension after exposure to AMPs resulted in the dissociation of most AMPs from the cell membrane. In contrast, the cell membrane damage induced by a short-time interaction with AMPs was largely irreversible since the rapid entry of SYTOX green into the cells was observed after 10-times dilution of the cell suspension after exposure to AMPs. Based on these results, we can conclude that the rapid, substantial membrane permeabilization of cytoplasmic contents after short exposure to AMPs and the residual damage after dilution induce cell death. Currently, the structure of the residual damage in the cell membrane after the dilution is unknown, which should be elucidated in future.

Author contributions

M.Z.I., F.H., and M.Y. designed the research. M.Z.I., F.H., and M.H.A. performed the experiments. M.Z.I., F.H., M.H.A., and M.Y. analyzed data. M.Z.I. and M.Y. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Challenging Research (no. 21K19214) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to M.Y., as well as by The Cooperative Research Project of the Research Center for Biomedical Engineering.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: Antje Pokorny Almeida.

Footnotes

Md. Hazrat Ali’s present address is Department of Pharmacy, Mawlana Bhashani Science and Technology University, Tangail-1902, Bangladesh

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2023.11.006.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Levy S.B., Marshall B. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat. Med. 2004;10:S122–S129. doi: 10.1038/nm1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bush K., Courvalin P., et al. Zgurskaya H.I. Tacking antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:894–896. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hancock R.E.W., Sahl H.-G. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1551–1557. doi: 10.1038/nbt1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks B.D., Brooks A.E. Therapeutic strategies to combat antibiotic resistance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014;78:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa F., Teixeira C., et al. Martins M.C.L. In: Antimicrobial Peptides: Basic for Clinical Application, K. Matsuzaki, Editor. Matsuzaki K., editor. Springer Nature; 2019. Clinical applications of AMPs; pp. 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang P.M., Vogel H.J. Structure-function relationships of antimicrobial peptides. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 1998;76:235–246. doi: 10.1139/bcb-76-2-3-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeaman M.R., Yount N.Y. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003;55:27–55. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melo M.N., Ferre R., Castanho M.A.R.B. Antimicrobial peptides: linking partition, activity and high membrane-bound concentrations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:245–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuzaki K., editor. Antimicrobial Peptides: Basic for Clinical Application. Springer Nature; Singapore: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Propheter D.C., Chara A.L., et al. Hooper L.V. Resistin-like molecule β is a bactericidal protein that promotes spatial segregation of the microbiota and the colonic epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:11027–11033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711395114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.University of Nebraska Medical Center . 2023. Antimicrobial Peptide Database (APD3)https://aps.unmc.edu [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sochacki K.A., Barns K.J., et al. Weisshaar J.C. Real-time attack on single Escherichia coli cells by the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:E77–E81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101130108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hossain F., Moghal M.M.R., et al. Yamazaki M. Membrane potential is vital for rapid permeabilization of plasma membranes and lipid bilayers by the antimicrobial peptide lactoferricin B. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:10449–10462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park C.B., Yi K.-S., et al. Kim S.C. Structure-activity analysis of buforin II, a histone H2A-derived antimicrobial peptide: The proline hinge is responsible for the cell-penetrating ability of buforin II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:8245–8250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150518097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hossain F., Dohra H., Yamazaki M. Effect of membrane potential on entry of lactoferricin B-derived 6-residue antimicrobial peptide into single Escherichia coli cells and lipid vesicles. J. Bacteriol. 2021;203 doi: 10.1128/JB.00021-21. e00021-21–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brogden K.A. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CLSI . CLSI Document M07-A9. 9th ed. Clinical and laboratory standards institute; Wayne, PA: 2012. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility test for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard. [Google Scholar]

- 19.CLSI . Clinical and laboratory standards institute; 1998. Methods for Determining Bactericidal Activity of Antimicrobial Agents. Approved Guideline. CLSI Document M26-A. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balouiri M., Sadiki M., Ibnsouda S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016;6:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hossain F., Billah M.M., Yamazaki M. Single-cell analysis of the antimicrobial and bactericidal activities of the antimicrobial peptide magainin 2. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022;10:e0011422. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00114-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuzaki K., Murase O., et al. Miyajima K. Translocation of a channel-forming antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2, across lipid bilayers by forming a pore. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6521–6526. doi: 10.1021/bi00019a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregory S.M., Pokorny A., Almeida P.F.F. Magainin 2 revisited: a test of the quantitative model for the all-or-none permeabilization of phospholipid vesicles. Biophys. J. 2009;96:116–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamba Y., Yamazaki M. Single giant unilamellar vesicle method reveals effect of antimicrobial peptide Magainin 2 on membrane permeability. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15823–15833. doi: 10.1021/bi051684w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karal M.A.S., Alam J.M., et al. Yamazaki M. Stretch-Activated Pore of Antimicrobial Peptide Magainin 2. Langmuir. 2015;31:3391–3401. doi: 10.1021/la503318z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasan M., Karal M.A.S., et al. Yamazaki M. Mechanism of initial stage of pore formation induced by antimicrobial peptide magainin 2. Langmuir. 2018;34:3349–3362. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b04219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umeyama M., Kira A., et al. Naito A. Interactions of bovine lactoferricin with acidic phospholipid bilayers and its antimicrobial activity as studied by solid-state NMR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:1523–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jing W., Svendsen J.S., Vogel H.J. Comparison of NMR structures and model-membrane interactions of 15-residue antimicrobial peptides derived from bovine lactoferricin. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2006;84:312–326. doi: 10.1139/o06-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moniruzzaman M., Alam J.M., et al. Yamazaki M. Antimicrobial peptide lactoferricin B-induced rapid leakage of internal contents from single giant unilamellar vesicles. Biochemistry. 2015;54:5802–5814. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parvez F., Alam J.M., et al. Yamazaki M. M. Elementary processes of antimicrobial peptide PGLa-induced pore formation in lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018;1860:2262–2271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roth B.L., Poot M., et al. Millard P.J. Bacterial viability and antibiotic susceptibility testing with SYTOX green nucleic acid stain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:2421–2431. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2421-2431.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grootjans S., Hassannia B., et al. Vanden Berghe T. A real-time fluorometric method for the simultaneous detection of cell death type and rate. Nat. Protoc. 2016;11:1444–1454. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lebaron P., Catala P., Parthuisot N. Effectiveness of SYTOX green stain for bacterial viability assessment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998;64:2697–2700. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2697-2700.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shuma M.L., Moghal M.M.R., Yamazaki M. Detection of the entry of nonlabeled transportan 10 into single vesicles. Biochemistry. 2020;59:1780–1790. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Islam M.Z., Sharmin S., et al. Yamazaki M. Effects of Mechanical Properties of Lipid Bilayers on Entry of Cell-Penetrating Peptides into Single Vesicles. Langmuir. 2017;33:2433–2443. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b03111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Billah M.M., Or Rashid M.M., et al. Yamazaki M. Antimicrobial peptide magainin 2-induced rupture of single giant unilamellar vesicles comprising E. coli polar lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2023;1865 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2022.184112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renggli S., Keck W., et al. Ritz D. Role of autofluorescence in flow cytometric analysis of Escherichia coli treated with bactericidal antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:4067–4073. doi: 10.1128/JB.00393-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strahl H., Hamoen L.W. Membrane potential is important for bacterial cell division. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:12281–12286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005485107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuzaki K., Sugishita K., et al. Miyajima K. Interactions of an antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2, with outer and inner membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1327:119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong F., Stokes J.M., et al. Collins J.J. Cytoplasmic condensation induced by membrane damage is associated with antibiotic lethality. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:2321. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22485-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.