Abstract

Under secondary metabolic conditions, the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium mineralizes 2,4,6-trichlorophenol. The pathway for the degradation of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol has been elucidated by the characterization of fungal metabolites and oxidation products generated by purified lignin peroxidase (LiP) and manganese peroxidase (MnP). The multistep pathway is initiated by a LiP- or MnP-catalyzed oxidative dechlorination reaction to produce 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone. The quinone is reduced to 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene, which is reductively dechlorinated to yield 2-chloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene. The latter is degraded further by one of two parallel pathways: it either undergoes further reductive dechlorination to yield 1,4-hydroquinone, which is ortho-hydroxylated to produce 1,2,4-trihydroxybenzene, or is hydroxylated to yield 5-chloro-1,2,4-trihydroxybenzene, which is reductively dechlorinated to produce the common key metabolite 1,2,4-trihydroxybenzene. Presumably, the latter is ring cleaved with subsequent degradation to CO2. In this pathway, the chlorine at C-4 is oxidatively dechlorinated, whereas the other chlorines are removed by a reductive process in which chlorine is replaced by hydrogen. Apparently, all three chlorine atoms are removed prior to ring cleavage. To our knowledge, this is the first reported example of aromatic reductive dechlorination by a eukaryote.

Chlorophenols, which have been produced industrially on a large scale, constitute a significant class of environmental pollutants. 2,4,6-Trichlorophenol (2,4,6-TCP) and pentachlorophenol have been used extensively as wood preservatives and pesticides (11, 31). In addition, 2,4-dichlorophenol (2,4-DCP) and 2,4,5-TCP are precursors in the synthesis of the herbicides 2,4-dichloro- and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acids (11, 31). Of the six isomers of TCP, 2,4,5-TCP and 2,4,6-TCP are considered priority pollutants (34).

The white-rot basidiomycetous fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium effectively degrades polymeric lignin as well as dimeric lignin model compounds (6, 16, 21, 25). Two extracellular heme peroxidases, lignin peroxidase (LiP) and manganese peroxidase (MnP), as well as an H2O2-generating system, apparently constitute the major extracellular components of this organism’s lignin degradative system (16, 19, 25, 42).

P. chrysosporium has been reported to degrade a variety of environmentally persistent pollutants, including 2,4,6-TCP (2, 5, 8, 18, 22, 28, 35, 37–39); however, the detailed metabolic pathway for the degradation of 2,4,6-TCP has not been examined previously. Earlier we proposed possible pathways for the degradation of 2,4-DCP (38) and 2,4,5-TCP (24), and we suggested that LiP and MnP as well as intracellular enzymes, including a 1,2,4-trihydroxybenzene (1,2,4-THB) 1,2-dioxygenase (33) and a quinone reductase (4), are involved in the degradation of these pollutants.

In the present report, we describe the degradation of 2,4,6-TCP by P. chrysosporium. Although the initial dechlorination at the 4 position is catalyzed by either LiP or MnP, as described previously for 2,4-DCP and 2,4,5-TCP (20, 24, 38), we make the novel observation that subsequent chlorines are removed by a reductive process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

2,4,6-TCP (I) and 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) were obtained from Aldrich. p-Hydroquinone (X) and U-14C-ring-labeled 2,4,6-TCP (10.2 mCi/mmol) were obtained from Sigma. 2-Chlorohydroquinone (IV) was obtained from Pfaltz and Bauer (Waterburg, Conn.), 1,2,4-THB (IX) was obtained from Lancaster Synthesis (Windham, N.H.), and 2-chloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene was obtained from Acros Organics (Pittsburgh, Pa.). All nonradioactive substrates and intermediates obtained commercially were purified by recrystallization prior to use.

Synthesis of intermediates.

2,6-Dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) was prepared from 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) by reduction with sodium dithionite. The reduced product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexane-ethyl acetate).

2,6-Dichloro-4-methoxyphenol (V) and 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene (VI) were prepared from 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) by treatment with diazomethane in ether at 0°C for 30 min. The ether was removed by evaporation, and the mono- and dimethylated compounds were purified by silica gel preparative thin-layer chromatography (hexane-ethyl acetate, 4:1).

5-Chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII) was prepared from 1,2,4-THB (IX) as previously described (12). 1,2,4-THB (IX) (1 mmol) was refluxed with N-chlorosuccinimide (1 mmol) and benzoylperoxide (1 mg) in ether (10 ml) for 3 h. The reaction mixture was filtered to remove most of the succinimide, washed with water, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and evaporated under reduced pressure to yield the crude product, which was purified by preparative thin-layer chromatography (hexane-ethylacetate, 1:1).

Culture conditions.

P. chrysosporium OGC101 (1) was grown from conidial inocula at 37°C in stationary cultures in 250-ml flasks as described previously (9, 15). The medium (25 ml) was as described previously (15, 26) and contained 2% glucose (high carbon [HC]) and either 1.2 mM (low nitrogen [LN]) or 12 mM (high nitrogen [HN]) ammonium tartrate as the carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively. The medium was buffered with 20 mM sodium 2,2-dimethylsuccinate (pH 4.5). Cultures were incubated under air for 3 days, after which they were purged with 99.9% O2 every 3 days. Dichomitus squalens, Pycnoporous cinnabarinus, Panus tigrinus, and Ceriporiopsis subvermispora were grown from conidial inocula at 28°C in stationary cultures in HN medium as described above.

Mineralization of 2,4,6-TCP.

14C-labeled substrate (105 cpm/flask, 0.01 μCi/μmol) in acetone was added to P. chrysosporium HCLN cultures, as described above, on day 6. Flasks were fitted with ports which allowed periodic purging with O2 and trapping of 14CO2 (15, 26) in a basic scintillation fluid as previously described (26). The efficiency of 14CO2 trapping after purging for 20 min was greater than 98%. Counting efficiency (>70%) was monitored with an automatic external standard.

Product analysis.

The substrates in dimethyl formamide (20 μl) were added to fungal cultures on day 6 to a final concentration of 250 μM. At the indicated times, the cultures were treated with sodium dithionite to reduce quinone products, acidified with HCl to pH 2, saturated with NaCl, and extracted three times with ethyl acetate. The total organic fraction was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and evaporated under reduced pressure. The products were acetylated with acetic anhydride-pyridine (2:1) and analyzed by gas chromatography (GC) and by GC-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Quinones were analyzed directly by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) without prior reduction.

Enzymes.

LiP and MnP were purified from the extracellular medium of acetate-buffered agitated cultures of P. chrysosporium OGC101 as described previously (13, 14, 40, 41). The LiP concentration was determined at 408 nm, using an extinction coefficient of 133 mM−1 cm−1 (14). The MnP concentration was determined at 406 nm, using an extinction coefficient of 129 mM−1 cm−1 (13).

Enzyme reactions.

LiP reaction mixtures (1 ml) contained enzyme (10 μg/ml), substrate (0.5 mM), and H2O2 (0.1 mM) in 20 mM sodium succinate (pH 3.0). Veratryl alcohol (0.1 mM) was added to stimulate the LiP reactions (16, 25, 41). MnP reaction mixtures (1 ml) contained enzyme (10 μg/ml), substrate (0.5 mM), MnSO4 (0.2 mM), and H2O2 (0.1 mM) in 50 mM sodium malonate (pH 4.5). LiP and MnP reactions were carried out at 25°C for 3 min. Reaction mixtures were extracted with ethyl acetate at pH 2, dried over sodium sulfate, evaporated under N2, and analyzed by GC or GC-MS after acetylation. For reductive acetylation, sodium dithionite was added to the reaction mixture before extraction. For quinone products, reaction mixtures were filtered through a Centricon 10 filter (Amicon) and analyzed by HPLC without prior reduction. Control reactions were conducted in the absence of either enzyme or H2O2.

2,6-Dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) reduction.

Six-day-old P. chrysosporium stationary cultures grown under LN conditions were filtered through a Büchner funnel to separate cells from the extracellular medium. The cells (1 g, wet weight) were washed and resuspended in either 20 mM sodium-2,2-dimethylsuccinate (pH 4.5, 25 ml) or in fresh culture medium. 2,6-Dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) (0.1 mM) was added to each cell suspension and to the filtered extracellular medium (25 ml). The mixtures were incubated at 38°C for 30 min, after which they were acidified, extracted, evaporated, and analyzed as described above.

Chromatography and mass spectrometry.

GC-MS was performed at 70 eV on a VG Analytical 7070E mass spectrometer fitted with an HP 5790A gas chromatograph and a 30-m fused silica column (DB-5; J&W Scientific). The oven temperature was programmed to increase from 70 to 320°C at 10°C/min. Quantitation of products was carried out on an HP 5890 II gas chromatograph equipped with the column described above. HPLC analysis of products was conducted with an HP Lichrospher 100 RP8 column, using a linear gradient of 0 to 75% acetonitrile in 0.05% phosphoric acid over 15 min, with a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Products were detected at 285 nm. Product yields on HPLC were quantitated by using calibration curves obtained with standards.

Assays for bacterial contamination.

P. chrysosporium OGC101 was grown on solid malt extract-yeast extract-Vogel’s (MYV) medium as previously described (1, 15) or in HCHN and HCLN stationary liquid cultures (20 ml), as described above. Conidia washed from the surface of the solid medium with water, and mycelia from the liquid cultures were suspended in water and subjected to filtration on 3-μm-pore-size Millipore membranes. Filtrates were plated on 1.5% malt extract–1.5% agar (MEA) plates, with or without 10 mg of benomyl per liter, and incubated at 24°C for several days.

Spores from the MYV slants and mycelia from each of the above liquid cultures were ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle, and genomic DNA was isolated as described previously (27). A set of universal primers specific for small-subunit rRNA genes (23), kindly supplied by D. Cullen, and genomic DNA were used in PCR amplifications as described previously (32).

RESULTS

Metabolism of radiolabeled 2,4,6-TCP.

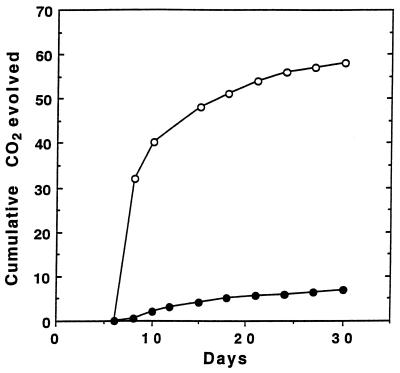

The evolution of 14CO2 from 14C uniformly labeled 2,4,6-TCP by P. chrysosporium cultures is shown in Fig. 1. After a 30-day incubation period, approximately 58% of the substrate was degraded to 14CO2 in nitrogen-limited HCLN cultures, whereas only 8% of the substrate was converted to 14CO2 under nitrogen-sufficient HCHN conditions.

FIG. 1.

Effect of nitrogen concentration on the mineralization of 14C-labeled 2,4,6-TCP. Six-day-old stationary cultures of P. chrysosporium containing 1.2 (○) or 12 (•) mM ammonium tartrate were inoculated with radiolabeled substrate as described in the text. Flasks were purged with O2, the evolved 14CO2 was trapped, and the radioactivity was counted as described in the text.

Metabolism of unlabeled 2,4,6-TCP.

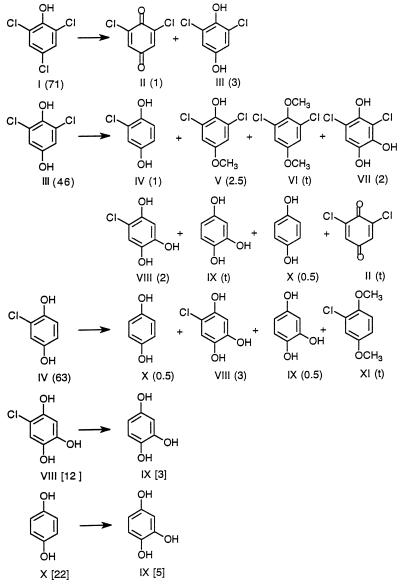

The products and percent yields obtained from the fungal metabolism in HCLN cultures of 2,4,6-TCP (I) or in separate experiments of various intermediates are shown in Fig. 2. Two products, 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) and 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III), were identified as metabolites of 2,4,6-TCP (I). When the metabolite 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) was added to fungal cultures, 2-chloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (IV), 2,6-dichloro-4-methoxyphenol (V), 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene (VI), 3,5-dichloro-1,2,4-THB (VII), 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII), 1,2,4-THB (IX), and 1,4-hydroquinone (X), as well as a trace amount of the oxidized substrate 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II), were identified as further metabolites (Fig. 2). The same products were obtained when 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) was added to fungal cultures (data not shown). The reductive addition product 3,5-dichloro-1,2,4-THB (VII) also was formed in small amounts when 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) was incubated alone in water (reference 10 and data not shown). When the 2,4,6-TCP (I) metabolite 2-chloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (IV) was added to cultures, the following metabolites were identified: 1,4-hydroquinone (X), 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII), and 1,2,4-THB (IX). The methylated product 2-chloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene (XI) also was formed in trace amounts. 1,2,4-THB (IX) was the sole metabolite identified when either 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII) or 1,4-hydroquinone (X) was added to cultures (Fig. 2). In several cases, we cannot fully account for the amount of substrate transformed by summing the amounts of intermediates obtained. This discrepancy is probably due to the further metabolism of intermediates. It may also be due to the instability of quinones and phenols, which can undergo one-electron reduction or oxidation to form free radicals, with subsequent coupling to macromolecules.

FIG. 2.

Metabolites identified from the P. chrysosporium degradation of 2,4,6-TCP and pathway intermediates. Cultures were incubated with either 2,4,6-TCP (I) or separately with the intermediate III, IV, VIII, or X and then extracted. Subsequently, products were analyzed as described in the text. HPLC was used to determine the yields of quinones. GC was used to determine the yields of other compounds. Percentages of substrates remaining or percent yields of products after incubation for 3 h (in brackets) or incubation for 6 h (in parentheses) are indicated. t, trace.

Under HCHN conditions, 2,4,6-TCP underwent very slow O-methylation to form 2,4,6-trichloromethoxybenzene as the sole product (data not shown). However, transformations of the 2,4,6-TCP metabolites under HCHN conditions were similar to those observed under HCLN conditions (Fig. 2), although the rates were lower.

Metabolites were identified by comparing their retention times on GC and their mass spectra with standards, as shown in Table 1. The HPLC retention times (in minutes) for metabolites were as follows: 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II), 9.6; 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III), 8.5; 2,6-dichloro-4-methoxyphenol (V), 10.2; 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene (VI), 12.4; 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII), 6.2; 1,2,4-THB (IX), 3.4; and 1,4-hydroquinone (X), 4.2.

TABLE 1.

Mass spectra of products, or derivatives, from the metabolism of 2,4,6-TCP and intermediates by P. chrysosporium cultures and enzyme oxidationsa

| Substrate or metabolite | GC retention time (min) | Mass spectrum m/z (relative intensity) |

|---|---|---|

| 2,4,6-Trichloroacetoxybenzene | 8.60 | 242 (2.9), 240 (8.2), 238 (12.0), 200 (31.8), 198 (96.1), 196 (100), 171 (2.4), 169 (7.2), 167 (7.9) |

| 2,6-Dichloro-1,4-diacetoxybenzene | 10.37 | 266 (4.2), 264 (11.3), 262 (18.7), 224 (2.0), 222 (1.0), 220 (16.4), 182 (11.5), 180 (66.1), 178 (100) |

| 2,6-Dichloro-1-acetoxy-4-methoxybenzene | 9.42 | 238 (0.7), 236 (3.6), 234 (5.2), 196 (11.1), 194 (60.5), 192 (100), 181 (8.8), 179 (54.3), 177 (88.7) |

| 2,6-Dichloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene (VI) | 8.13 | 210 (6.0), 208 (34.6), 206 (55.6), 195 (11.0), 193 (67.2), 191 (100), 165 (7.4), 163 (10.9) |

| 2,6-Dichloro-1,3,4-triacetoxybenzene | 14.01 | 320 (0.2), 322 (2.1), 320 (3.7), 282 (1.1), 280 (5.1), 278 (10.1), 240 (3.4), 238 (17.3), 236 (22.8), 198 (10.2), 196 (63.8), 194 (100) |

| 5-Chloro-1,2,4-triacetoxybenzene | 13.09 | 288 (1.8), 286 (4.9), 246 (4.6), 244 (10.5), 204 (9.0), 202 (20.3), 162 (37.0), 160 (100) |

| 2-Chloro-1,4-diacetoxybenzene | 9.58 | 230 (1.0), 228 (3.6), 188 (6.5), 186 (19.5), 146 (44.3), 144 (100) |

| 1,2,4-Triacetoxybenzene | 12.19 | 252 (5.0), 210 (17.0), 168 (42.0), 126 (100), 79 (39.0) |

| 1,4-Diacetoxybenzene | 8.44 | 194 (2.0), 152 (34.0), 110 (100), 81 (32.0) |

Cultures were incubated and extracted, and products were analyzed, as described in the text. Products from the oxidation of substrates by purified MnP and LiP also were identified. Reaction conditions and analysis were as described in the text. In all cases, the retention times and mass spectra of standard compounds were essentially identical to those of the substrates and identified metabolites.

Metabolism of 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB by other white-rot fungi.

To examine whether the apparent reductive dechlorination reaction was unique to P. chrysosporium, the metabolism of 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII) was examined in several other white-rot fungi. The results in Table 2 show that cultures of D. squalens, C. subvermispora, P. tigrinus, and P. cinnabarinus all rapidly degraded 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII), producing 1,2,4-THB (IX) as the sole aromatic metabolite.

TABLE 2.

Transformation of 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII) by various white-rot fungia

| Species | Substrate (VIII) remaining (%) | 1,2,4-THB (IX) formed (%) |

|---|---|---|

| D. squalens | 41 (tr) | 2 |

| C. subvermispora | 47 (tr) | 2 |

| P. tigrinus | 70 (15) | 0.5 |

| P. cinnabarinus | 55 (tr) | 1 |

| P. chrysosporium | 12 (tr) | 3 |

Cultures were incubated and extracted, and products were analyzed, as described in the text. Percentages of substrate, 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII), remaining and product, 1,2,4-THB (IX), formed after incubation for 3 h are shown. Percentages of substrate remaining after incubation for 6 h are shown in parentheses.

Enzymatic oxidation of 2,4,6-TCP and metabolic intermediates.

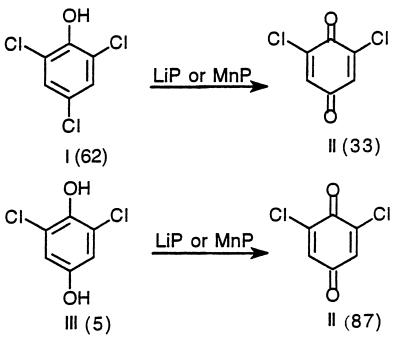

The MnP- and LiP-catalyzed oxidations of 2,4,6-TCP (I) and 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) are shown in Fig. 3. Both MnP and LiP oxidized 2,4,6-TCP (I) to yield 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II). 2,6-Dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) also was oxidized by both MnP and LiP to yield 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) as the major product (Fig. 3). The quinone (II) was identified by comparing its retention time with that of the standard compound on HPLC (see above). Its reduced acetylated derivative 2,6-dichloro-1,4-diacetoxybenzene was identified by GC (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

Products identified from the oxidation of 2,4,6-TCP (I) and 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) by purified MnP and LiP. Reaction conditions and identification of products were as described in the text. Percentages of substrate remaining and product yields (in parentheses) were determined by HPLC.

Reduction of 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II).

As shown in Table 3, six-day-old cultures of P. chrysosporium, as well as washed cells resuspended in fresh medium, readily converted 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) to 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III). In contrast, only minimal conversion of the quinone (II) to the hydroquinone (III) occurred with the filtered extracellular media from 6-day-old cultures.

TABLE 3.

Reduction or reduction/methylation of 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) by P. chrysosporium cells and extracellular medium

| Reaction conditionsa | Product yield (%)b

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| III | V | VI | |

| 6-day-old cultures | 92 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 6-day-old cells resuspended in buffer | 95 | 0.1 | —c |

| Filtered extracellular medium from 6-day-old cultures | 2 | — | — |

2,6-Dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) was added to each flask and incubated at 37°C for 30 min as described in the text.

HPLC was used to determine the remaining quinone (II) and the yield of 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III). GC was used to determine the yields of the methylated products 2,6-dichloro-4-methoxyphenol (V) and 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene (VI).

—, undetectable.

Bacterial analysis of P. chrysosporium cultures.

To rule out the possibility that the above results were due to bacterial contamination of P. chrysosporium cultures, filtrates from conidiospore and mycelia suspensions from solid and liquid cultures were plated on MEA containing benomyl. Following incubation at 24°C, no bacterial growth was observed. Tight binding between bacteria and the fungal spores and/or mycelia could explain this result. Therefore, bacterium- and fungus-specific primers were used for the differential amplification of small-subunit rRNA genes from DNA isolated from cultures grown under each of the conditions described above. Only a single PCR product corresponding to the fungal gene was detected, confirming the absence of bacterial contamination (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

White-rot basidiomycetous fungi are primarily responsible for the initial depolymerization of lignin in wood (6, 16, 21, 25). The best-studied white-rot fungus, P. chrysosporium, degrades lignin during secondary metabolic (idiophasic) growth (6, 15, 16, 21, 25, 26). Under ligninolytic conditions, P. chrysosporium secretes two heme peroxidases (LiP and MnP), in addition to an H2O2-generating system (6, 16, 21, 25). These two peroxidases appear to be primarily responsible for the oxidative depolymerization of this heterogeneous, random, phenylpropanoid polymer (3, 16, 19, 21, 25, 42). Other studies have demonstrated that P. chrysosporium is capable of mineralizing a variety of persistent environmental pollutants (2, 5, 8, 18, 22, 28, 35, 37–39). In particular, we have examined the P. chrysosporium degradative pathways for the pollutants 2,4-DCP (38), 2,4,5-TCP (24), and 2,7-dichlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (39). In these earlier studies, we showed that the first step in the degradation of chlorophenols is the oxidative dechlorination of the substrate to its corresponding p-quinone, and our results suggested that all of the chlorines are removed before ring cleavage occurs (24, 38). However, in these previous studies, we were not able to identify definitively the mechanism(s) responsible for the further dechlorination of these chlorophenols following the initial oxidative dechlorination reaction.

In the bacterial pathway for the degradation of chlorophenols, the chlorine atom in the para position is removed by an intracellular chlorohydrolase, yielding a chlorinated hydroquinone. Subsequently, other chlorine atoms are removed via reductive dechlorination (29). Herein, we demonstrate for the first time that reductive dechlorination of chlorinated hydroquinones also occurs in eukaryotic white-rot fungi, and we report the complete degradative pathway for 2,4,6-TCP (I) by P. chrysosporium.

Metabolism of radiolabeled of 2,4,6-TCP.

Our results demonstrate that P. chrysosporium extensively mineralizes 2,4,6-TCP (I) only under LN conditions (Fig. 1), suggesting that the lignin degradative system is responsible, at least in part, for the degradation of this pollutant.

Pathway for 2,4,6-TCP degradation.

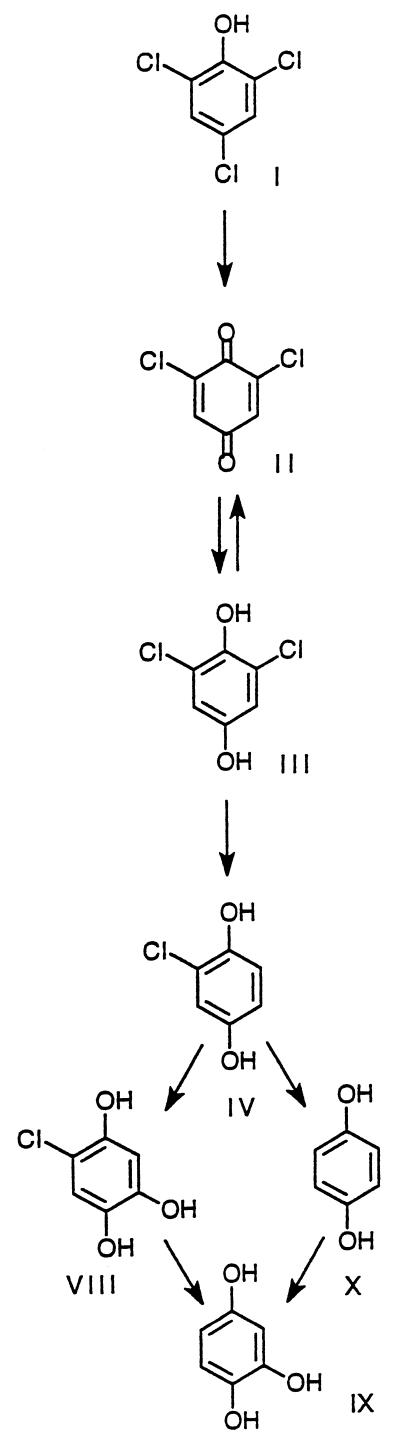

The sequential identification of primary metabolites produced during 2,4,6-TCP (I) degradation by P. chrysosporium and the subsequent identification of secondary metabolites following the addition of primary metabolites to fungal cultures (Fig. 2; Table 1) enable us to propose a pathway for the degradation of this pollutant (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Proposed pathway for the degradation of 2,4,6-TCP (I) by P. chrysosporium.

The first step in the 2,4,6-TCP degradative pathway is the oxidation of 2,4,6-TCP (I) to 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) by either LiP or MnP (Fig. 3 and 4). Similar oxidative dechlorination reactions catalyzed by LiP and by MnP (20, 24, 38) have been reported for other chlorinated phenols.

2,6-Dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) is identified as the major metabolite obtained from 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II), suggesting that quinone reduction is the next step in the pathway (Fig. 4). A similar quinone reduction step has been observed previously during the degradation of 2,4-DCP and 2,4,5-TCP by P. chrysosporium (24, 38). Chloroquinones are strong oxidants which may be converted to their corresponding hydroquinones either enzymatically or nonenzymatically. The results in Table 3 demonstrate that 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) is converted efficiently to the hydroquinone (III) in the presence of washed P. chrysosporium cells, whereas only minimal reduction occurs in filtered extracellular medium. This finding suggests that the reduction is cell associated. Quinone reductases have been purified from P. chrysosporium cell extracts (4, 7).

The formation of 2-chloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (IV) from 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) (Fig. 2) in the third step of the pathway (Fig. 4) strongly suggests that reductive dechlorination occurs subsequent to quinone reduction. Reductive dechlorination has not been reported in earlier studies on chlorophenol degradation by P. chrysosporium (2, 18, 22, 24, 28, 38). Indeed, to our knowledge, this is the first report of aromatic reductive dechlorination by a eukaryote. Reductive aromatic dehalogenation has been found in several aerobic and anaerobic bacterial systems (17, 29, 36, 43). For example, reductive dechlorination of tetrachloro-1,4-hydroquinone by bacteria has been reported (29, 36, 43). Our results also demonstrate that MnP and/or LiP oxidizes 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) to 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II), with no detectable oxidative dechlorinated product (Fig. 3). This finding suggests that the oxidative dechlorination of 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) probably is not a significant reaction in the further dechlorination of this metabolite.

In the fourth step in the proposed pathway, 2-chloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (IV) is converted to 1,4-hydroquinone (X) (Fig. 4). 1,2,4-THB (IX) and 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII) also are observed as metabolites of 2-chloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (IV) (Fig. 2). Thus, 2-chloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (IV) is either dechlorinated to form 1,4-hydroquinone (X) or hydroxylated to form 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB trihydroxybenzene (VIII) (Fig. 4).

1,4-Hydroquinone (X) is rapidly hydroxylated to 1,2,4-THB (IX), the final aromatic product (Fig. 4). In addition, 1,2,4-THB (IX) is the only product formed when 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII) is added to fungal cultures (Fig. 2). Thus, dechlorination of 2-chloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (IV) either precedes or follows hydroxylation.

1,2,4-THB (IX), the final aromatic metabolite in the degradation of 2,4,6-TCP (Fig. 4), is ring cleaved to yield β-ketoadipic acid (33). A THB dioxygenase from P. chrysosporium that ring cleaves 1,2,4-THB to produce β-ketoadipic acid has been purified in our laboratory (33).

Methylated intermediates.

The methylation of phenols and hydroquinones accompanies the degradation of various aromatics by P. chrysosporium cultures (2, 37–39). Two methylated products, 2,6-dichloro-4-methoxyphenol (V) and 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene (VI), are obtained in low yield when 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (II) or 2,6-dichloro-1,4-dihydroxybenzene (III) is added to cultures (Fig. 2). As described previously (24), the methyltransferases responsible for these reactions are probably intracellular enzymes. Since metabolically stable dimethoxy compounds do not accumulate in cultures during the degradation of 2,4,6-TCP (I), these methylation reactions are probably side reactions. This conclusion is supported by the extensive mineralization of 2,4,6-TCP (I) that is observed in P. chrysosporium cultures (Fig. 1).

Reductive dechlorination in other white-rot fungi.

Since the production of reductively dechlorinated products in P. chrysosporium cultures was a surprising finding, we have examined whether other white-rot fungi also can carry out these reactions. D. squalens, C. subvermispora, P. tigrinus, and P. cinnabarinus all are capable of dechlorinating 5-chloro-1,2,4-THB (VIII) to produce 1,2,4-THB (IX) (Table 2), suggesting that the ability to carry out reductive dechlorinations may be widespread among white-rot fungi.

Analysis of bacterial contamination.

Since bacteria carry out reductive dechlorination reactions similar to those described here (29), we were concerned that bacterial contamination might have been the cause of these novel results. Therefore, we reexamined P. chrysosporium OGC101 for bacterial contamination, using microbiological filtration (23, 30) and the differential amplification of rRNA genes by PCR (23, 32). The absence of either bacterial growth or bacterial rRNA genomic PCR products under all of the culture conditions used here confirms the results of Janse et al. (23) and demonstrates P. chrysosporium is responsible for the reactions described here.

In conclusion, our results suggest that P. chrysosporium degrades 2,4,6-TCP via a pathway involving the initial oxidative dechlorination of 2,4,6-TCP by either LiP or MnP to form a dichloroquinone (Fig. 4). Subsequent intracellular reduction of the chloroquinone results in the formation of 2,6-dichlorohydroquinone, which is reductively dechlorinated to 2-chlorohydroquinone. 2-Chlorohydroquinone either is reductively dechlorinated further to hydroquinone, which undergoes orthohydroxylation to form THB, or is hydroxylated to form chlorotrihydroxybenzene, which is reductively dechlorinated to form THB. THB is ring cleaved by 1,2,4-THB 1,2-dioxygenase (33). We are attempting to identify the enzymes responsible for the aromatic dechlorination and hydroxylation reactions identified in this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dan Cullen, U.S. Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wis., for the PCR primers and Margaret Alic for useful discussions.

This research was supported by grants R821269-01 from the Environmental Protection Agency and DE-FG03-96ER20235 from the U.S. Department of Energy, Division of Energy Biosciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alic M, Letzring C, Gold M H. Mating system and basidiospore formation in the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1464–1469. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.7.1464-1469.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armenante P M, Pal N, Lewandowski G. Role of mycelium and extracellular protein in the biodegradation of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1711–1718. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.6.1711-1718.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boominathan K, Dass S B, Randall T A, Kelly R L, Reddy C A. Lignin peroxidase-negative mutant of the white-rot basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:260–265. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.260-265.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brock B J, Rieble S, Gold M H. Purification and characterization of a 1,4-benzoquinone reductase from the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3076–3081. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.3076-3081.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bumpus J A, Aust S D. Biodegradation of environmental pollutants by the white rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium: involvement of the lignin-degrading system. Bioessays. 1987;6:166–170. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buswell J A, Odier E. Lignin degradation. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1987;6:1–60. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Constam D, Muheim A, Zimmermann W, Fiechter A. Purification and partial characterization of an intracellular NADH:quinone oxidoreductase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2209–2214. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton D C. Mineralization of polychlorinated biphenyls by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1985;7:194–196. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enoki A, Goldsby G P, Gold M H. β-Ether cleavage in the lignin model compound 4-ethoxy-3-methoxyphenylglycerol-β-guaiacyl ether and derivatives by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch Microbiol. 1981;129:141–145. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finley K T. The addition and substitution chemistry of quinones. In: Patai S, editor. The chemistry of the quinonoid compounds, part 2. London, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1974. pp. 877–1144. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freiter E R. Chlorophenols. In: Mark H F, Othmer D F, Overberger C G, Seaborg G T, editors. Encyclopedia of chemical technology. 3rd ed. Vol. 5. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1979. pp. 864–872. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman D, Ginsburg D. Halogenation of pyrogallol trimethyl ether and similar systems. J Org Chem. 1958;23:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glenn J K, Gold M H. Purification and characterization of an extracellular Mn(II)-dependent peroxidase from the lignin-degrading basidiomycete, Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;242:329–341. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gold M H, Kuwahara M, Chiu A A, Glenn J K. Purification and characterization of an extracellular H2O2-requiring diarylpropane oxygenase from the white rot basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984;234:353–362. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold M H, Mayfield M B, Cheng T M, Krisnangkura K, Enoki A, Shimada M, Glenn J K. A Phanerochaete chrysosporium mutant defective in lignin degradation as well as several other secondary metabolic functions. Arch Microbiol. 1982;132:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold M H, Wariishi H, Valli K. Extracellular peroxidases involved in lignin degradation by the white rot basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. ACS Symp Ser. 1989;389:127–140. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haggblom M M, Janke D, Salonen M S S. Hydroxylation and dechlorination of tetrachlorohydroquinone by Rhodococcus sp. strain CP-2 cell extracts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:516–519. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.2.516-519.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammel K E. Organopollutant degradation by lignolytic fungi. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1989;11:776–777. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammel K E, Moen M A. Depolymerization of a synthetic lignin in vitro by lignin peroxidase. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1991;13:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammel K E, Tardone P J. The oxidative 4-dechlorination of polychlorinated phenols is catalyzed by extracellular fungal lignin peroxidases. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6563–6568. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higuchi T. Lignin biochemistry: biosynthesis and biodegradation. Wood Sci Technol. 1990;24:23–63. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huynh V B, Chang H M, Joyce T W, Kirk T K. Dechlorination of chloro-organics by a white-rot fungus. Tech Assoc Pulp Pap Ind J. 1985;68:98–102. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janse B J H, Gaskell J, Cullen D, Zapanta L, Dougherty M J, Tien M. Are bacteria omnipresent on Phanerochaete chrysosporium Burdsall? Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2913–2914. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2913-2914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joshi D K, Gold M H. Degradation of 2,4,5-trichlorophenol by the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1779–1785. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.6.1779-1785.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirk T K, Farrell R L. Enzymatic “combustion”: the microbial degradation of lignin. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:465–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.002341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirk T K, Schultz E, Connors W J, Lorenz L F, Zeikus J G. Influence of culture parameters on lignin metabolism by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch Microbiol. 1978;117:277–285. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S B, Taylor J W. Isolation of DNA from fungal mycelia and single spores. In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 282–287. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mileski G J, Bumpus J A, Jurek M A, Aust S D. Biodegradation of pentachlorophenol by the white rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2885–2889. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.12.2885-2889.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohn W W, Tiedje J M. Microbial reductive dehalogenation. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:482–507. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.482-507.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murandi S F, Guiraud P, Croize J, Falsen E, Eriksson K E L. Bacteria are omnipresent on Phanerochaete chrysosporium Burdsall. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2477–2481. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2477-2481.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rappe C. Chloroaromatic compounds containing oxygen: phenols, diphenyl ethers, dibenzo-p-dioxins, and dibenzofuran. In: Hutzinger O, editor. The handbook for environmental chemistry. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag KG; 1980. pp. 157–179. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reysenbach A, Giver L J, Wickham G S, Pace N R. Differential amplification of rRNA genes by polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3417–3418. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3417-3418.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rieble S, Joshi D K, Gold M H. Purification and characterization of a 1,2,4-trihydroxybenzene 1,2-dioxygenase from the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;176:4838–4844. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4838-4844.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sittig M. Handbook of toxic and hazardous chemicals. Park Ridge, N.J: Noyes Publications; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spadaro J T, Gold M H, Renganathan V. Degradation of azo dyes by the lignin-degrading fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2397–2401. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2397-2401.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steiert J G, Crawford R L. Catabolism of pentachlorophenol by a Flavobacterium sp. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;141:825–830. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valli K, Brock B J, Joshi D K, Gold M H. Degradation of 2,4-dinitrotoluene by the lignin-degrading fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:221–228. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.221-228.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valli K, Gold M H. Degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenol by the lignin-degrading fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:345–352. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.345-352.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valli K, Wariishi H, Gold M H. Degradation of 2,7-dichlorodibenzo-p-dioxin by the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2131–2137. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2131-2137.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wariishi H, Dunford H B, MacDonald I D, Gold M H. Manganese peroxidase for the lignin-degrading basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium: transient-state kinetics and reaction mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3335–3340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wariishi H, Gold M H. Lignin peroxidase compound III. Mechanism of formation and decomposition. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2070–2077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wariishi H, Valli K, Gold M H. In vitro depolymerization of lignin by manganese peroxidase of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;176:269–275. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90919-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xun L, Topp E, Orser C S. Purification and characterization of a tetrachloro-p-hydroquinone reductive dehalogenase from a Flavobacterium sp. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:8003–8007. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8003-8007.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]