Abstract

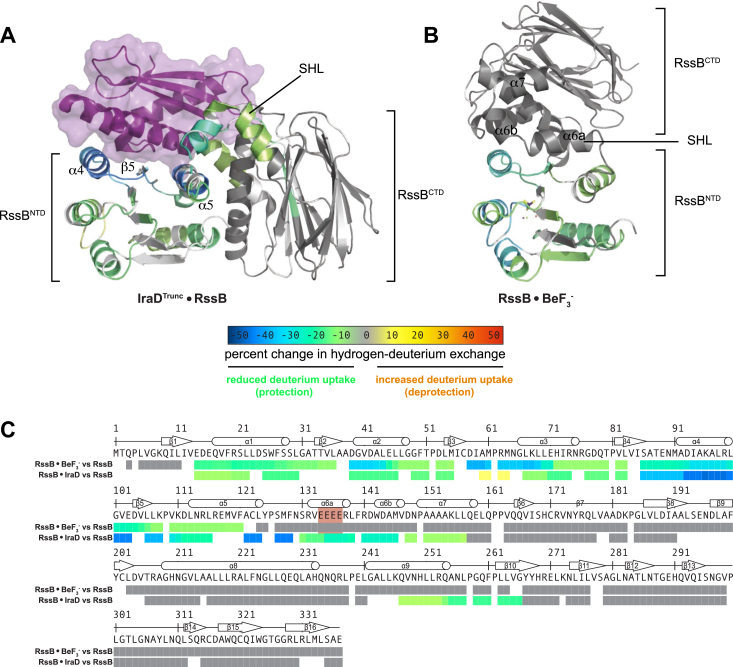

In enterobacteria such as Escherichia coli, the general stress response is mediated by σs, the stationary phase dissociable promoter specificity subunit of RNA polymerase. σs is degraded by ClpXP during active growth in a process dependent on the RssB adaptor, which is thought to be stimulated by the phosphorylation of a conserved aspartate in its N-terminal receiver domain. Here we present the crystal structure of full-length RssB bound to a beryllofluoride phosphomimic. Compared to the structure of RssB bound to the IraD anti-adaptor, our new RssB structure with bound beryllofluoride reveals conformational differences and coil-to-helix transitions in the C-terminal region of the RssB receiver domain and in the interdomain segmented helical linker. These are accompanied by masking of the α4-β5-α5 (4-5-5) “signaling” face of the RssB receiver domain by its C-terminal domain. Critically, using hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry, we identify σs-binding determinants on the 4-5-5 face, implying that this surface needs to be unmasked to effect an interdomain interface switch and enable full σs engagement and hand-off to ClpXP. In activated receiver domains, the 4-5-5 face is often the locus of intermolecular interactions, but its masking by intramolecular contacts upon phosphorylation is unusual, emphasizing that RssB is a response regulator that undergoes atypical regulation.

Keywords: RpoS, general stress response, beryllofluoride, receiver domain, phosphorylation, IraD, pseudophosphatase, Phos-tag, HDX-MS, ClpXP, acetyl phosphate

The ability to adapt to a changing and sometimes adverse environment is a fundamental property of any living system. It ensures survival. In bacteria, deregulation of the pathways associated with stress responses are implicated in growth defects (1), biofilm formation (1, 2, 3), antibiotic resistance (1, 4, 5), and altered ability to colonize hosts (6, 7). By definition, general stress responses, recently reviewed by Gottesman (1), unlike specific stress responses, are mediated by global regulators and confer broad cross-resistance to stress signals that did not originally induce the response. In enterobacteria, the general stress response is mediated by σs (RpoS, encoded by the rpoS gene), the stationary phase dissociable promoter specificity subunit of RNA polymerase. σs turns on a large regulon of up to 24% of the Escherichia coli genes (8, 9, 10, 11) and is widely dubbed the master regulator of the general stress response. While increased σs levels are required for bacterial virulence and responses to stress, including antibiotic stress (12, 13, 14), unregulated overexpression of σs is also detrimental (15), likely because under these conditions, the system cannot restart growth even after the stress signal has gone away. This underscores that for a plastic stress response and niche adaptation, cells must regulate intracellular σs levels in a tight and fast manner. This is accomplished through both positive and negative regulation at multiple levels, including (1) transcription activation (16, 17, 18, 19), (2) translation activation/repression, involving structural rearrangements of the rpoS mRNA by small regulatory RNAs and RNA chaperones (19, 20, 21), and (3) protein turnover by the ATP-dependent ClpXP machinery (19, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26).

By itself, σs is a poor substrate for ClpXP and needs to be presented to the protease by an adaptor, the two-domain response regulator RssB (aka MviA, SprE) (22, 25, 26, 27). Substrate presentation represents the rate-limiting step in σs turnover (28) and is regulated by the phosphorylation of D58 in the N-terminal receiver domain (RssBNTD) (29). As a response regulator, RssB is atypical; its effector domain (RssBCTD) is specialized for protein–protein interactions (30) rather than DNA binding as in most response regulators (31). Moreover, while other adaptors operate in pairs with cognate anti-adaptors, RssB is unique in that it is inhibited by multiple, sequence-wise unrelated and stress-specific anti-adaptors (IraD, IraM, IraP, and IraL) (32, 33). This suggests a great potential for plasticity and specialization via negative regulation in response to distinct triggers.

The role of RssB phosphorylation has remained controversial for several reasons. The small molecule phosphodonor acetyl phosphate (AcP) was found to stimulate σs degradation in vivo and in vitro (27, 29, 32, 34), an effect that was attributed to phosphorylation promoting the formation of a stable binary σs–RssB and ternary σs–RssB–ClpX delivery complex (27). Consistent with this, in vitro reconstitution of σs proteolysis demonstrated that phosphorylation stimulates the degradation reaction with a ∼ threefold decrease in the apparent KM (27, 30, 32, 34). While a recent study suggested that, instead, phosphorylation lowers the affinity of RssB for σs (35), we note that in this case, RssB and σs truncations were employed for analysis, which according to our work, do not faithfully recapitulate the interactions between the full-length proteins. The situation is further complicated by the finding that a strain carrying a nonphosphorylatable D to A substitution of the phosphoacceptor site, D58, on the rssB chromosomal allele displays no strong phenotype under either starvation or supplementation with the limiting nutrient (recovery from stress) (36). Others have shown that nonphosphorylatable substitutions of D58, such as alanine and proline, are significantly defective in σs degradation (32). On the other hand, the D58E phosphomimetic variant is only partially active in vivo and in vitro (30, 32). The partial activity of these variants as well as the notorious ability of response regulators to interconvert between ON and OFF forms, with conformational equilibria shifted by phosphorylation but also mutations (37, 38), confound the analysis. Given these challenges, 2 decades of work have yielded limited insights into the phosphorylation-dependent structural changes that underpin the communication between the two RssB domains upon σs binding and hand-off.

Here we sought to elucidate the effects of phosphorylation on RssB using a combination of X-ray crystallography of phosphorylated-like full-length RssB, hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS), and functional assays. We show that the molecular plasticity of RssB is, at least partially, phosphorylation-dependent and affects primarily the C-terminal helix of the receiver domain (helix α5) and the interdomain segmented helical linker, henceforth referred to as SHL. These elements are packed differently than previously seen in the IraD-RssBD58P cocrystal. While activation of response regulators often involves disruption of inhibitory contacts between the receiver and effector domains to liberate their 4-5-5 face for target binding or dimerization (39), we unexpectedly observe that RssB phosphorylation induces a switch in the interface used for effector domain packing, from the α1−α5 face in the nonphosphorylated inhibited state (i.e. bound to IraD) to the 4-5-5 face in the phosphorylated-like free state. Thus, the 4-5-5 face, the canonical locus for receiver domain oligomerization and association with targets, is utilized for an interface switch to achieve an alternative closed RssB structure, which, upon return to active growth when anti-adaptor level may still be elevated, shields the 4-5-5 face from its inhibitors and yet can also associate with σs with high affinity to deliver the substrate to ClpXP.

Results

Trapping phosphorylated-like RssB with a phosphomimetic analog

Despite significant efforts, full-length RssB has long resisted crystallization due to its limited solubility and what is thought to be a dynamic nature, characterized, as in other response regulators, by a dynamic equilibrium of “OFF” forms (40)—nonphosphorylated and with poor affinity for σs and an “ON” form—stabilized by phosphorylation and with high affinity for σs. Examples in which the active form of the receiver can be accessed spontaneously, even in the absence of phosphorylation, either by conformational breathing or upon binding partners, have also been reported (41). In the case of RssB, most of our understanding of phosphorylation-dependent stimulation comes from studies employing AcP to stimulate formation of a σs:RssB:ClpX assembly (27) and promote σs degradation without being an absolute requirement for it (27, 32, 34). We first used our high-quality purified RssB preparations to verify RssB activity by performing in vitro phosphorylation assays in the presence of AcP, followed by separation of the phosphorylated from the nonphosphorylated RssB species by Phos-tag gel electrophoresis. RssB was rapidly modified within the first 5 min of incubation with AcP, with ∼70% phosphorylation reached in ∼20 min (Figs. 1A and S1A). This is likely due to the autodephosphorylation activity of RssBNTD, a general property of receiver domains, which can vary in rate by orders of magnitude from protein to protein (37) and precludes complete phosphorylation. As expected, we detect no phosphorylated species in the presence of the nonphosphorylatable RssB variant, RssBD58P (Fig. S1B), which otherwise remains moderately functional as an adaptor and also supports regulation by anti-adaptors (32). This confirms that D58 is the phosphoacceptor site as also shown before (29, 32).

Figure 1.

Trapping RssB∼P with a Phosphomimic.A, time course of RssB phosphorylation (top). Reactions were initiated by the addition of 15 mM AcP, mixed at various timepoints with LDS-loading buffer, and loaded onto 10% Phos-tag polyacrylamide gels. Shown are means ± s.d. of three technical replicates together with one representative Phos-tag gel (bottom). Error bars are generally smaller than symbols. Complete gel data in Fig. S1A. B, size-exclusion chromatography profiles of RssB, σs, and premixed RssB:σs complexes ± 25 mM AcP and 10 mM Mg2+. Shown below is an SDS-PAGE analysis of peak fractions eluted off a Superdex 200 10/300 column (Cytiva). Elution volumes are indicated above the gel images. Lanes 1 and 2 correspond to RssB-only and σs-only control runs. Phosphorylation was initiated by pre-incubation with AcP for 15 min on ice prior to injection. C, pull-down assay probing the RssB-σs interaction in the absence and presence of beryllofluoride. Purified RssB was pulled down via 6His-σs, which was immobilized to Ni2+-NTA beads. Shown are means ± s.d. (n > 3) together with one representative SDS-PAGE analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed Student’s t test (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). Results of three representative experiments are shown in Fig. S1C. AcP, acetyl phosphate.

We found that in the presence of AcP and Mg2+, but not without AcP, RssB forms a stable complex with σs (Fig. 1B). This is consistent with earlier work that showed that no discrete peak corresponding to the binary σs:RssB or ternary σs:RssB:ClpX complexes can be observed in gel filtration profiles in the absence of AcP (27). We carried out extensive crystallization trials in the presence of AcP, but these remained unfruitful. Because the phosphoaspartyl bond is labile in aqueous solutions and receiver domains have intrinsic dephosphorylation activity (42), we sought to limit sample heterogeneity by replacing AcP with Mg2+•beryllofluoride. This phosphomimic has been used for trapping phosphorylated-like conformations of numerous response regulators (43), including the truncated receiver domain of RssB, RssBNTD (44). As expected, addition of beryllofluoride led to a substantial increase in the amount of RssB pulled down by His-tagged σs, which was readily apparent in a ∼5-fold increase in pull-down efficiency (Fig. 1C, compare lane 3, left to lane 3, right and Fig. S1C). We obtained well-diffracting crystals of beryllofluoride-bound RssB, but not of free RssB, allowing us to determine the structure of beryllofluoride-bound RssB at 2.38 Å resolution (Table 1).

Table 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statisticsa

| Data collection | |

|---|---|

| Space group | C2221 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a,b,c (Å) | 41.37, 119.04, 135.97 |

| α,β,γ (°) | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97911 |

| Resolution (Å) | 135.97-2.38 (2.47-2.38) |

| No. of reflections/Unique reflections | 105,917/13,903 |

| Rpim | 0.113 (0.691) |

| <I/σI> | 6.4 (1.1) |

| Completeness | 99.7 (97.8) |

| Multiplicity | 7.6 (5.0) |

| CC1/2 | 0.980 (0.339) |

| Refinement | |

|---|---|

| Resolution (Å) | 67.98–2.38 |

| No. of reflections used | 13,867(1314) |

| Rwork/Rfree (%)b | 22.20/27.77 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 2604 |

| Solvent | 50 |

| Ligands | 56 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 53.26 |

| Solvent | 48.16 |

| Ligands | 57.29 |

| No. of TLS groups | 2 |

| R.m.s deviation | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.08 |

| Coordinate errorc (Å) | 0.34 |

| Ramachandran plot analysis | |

| Preferred (%) | 98.2 |

| Allowed (%) | 1.8 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.0 |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0.0 |

| Cβ deviations (%) | 0.0 |

| Molprobity Clashscore | 1.51 |

| PDB ID | 8T85 |

Values in parenthesis are for the highest resolution shell.

Rfree was calculated by omitting 10% of the data from refinement.

Maximum likelihood-based.

Architecture of beryllofluoride-bound RssB

Beryllofluoride-stabilized RssB assumes a compact conformation with contacts between RssBNTD and its C-terminal pseudophosphatase domain (RssBCTD) that bury a ∼529 Å2 interface, suggesting a low-affinity and possibly transient interaction between the two domains (Fig. 2). The “closed” conformation is stabilized by the SHL (magenta in Fig. 2, A–F) that docks atop the proximal edge of the 4-5-5 face and packs against α8, holding the two domains together (Fig. 2, B and C). The Mg2+-beryllofluoride moiety is well ordered and surrounded by residues forming a quintet required for phosphorylation-dependent signal transduction (red dotted outlines in Figure 2A and sticks in the inset of Fig. 2C) and well-ordered water molecules, which complete the octahedral coordination of the Mg2+ ion (inset of Fig. 2C). The RssBNTD–RssBCTD interface is punctuated by hydrogen bonds between E89 and Q247, K108 and H233, P109 and Q228 (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Overall architecture of RssB·BeF-•Mg2+. A, domain architecture of Escherichia coli RssB. Phosphoacceptor D58 is indicated with a red circle and key functional residues are highlighted. Residues belonging to the phosphorylation stabilization quintet are marked by red dotted outlines. The polyglutamate motif within the SHL (magenta) is shown as a burnt orange vertical bar. Selected SHL sequences shown below are colored by evolutionary conservation from white (not conserved) to black (invariant). Secondary structural elements in the presence of beryllofluoride and IraDTrunc, as defined with DSSP (72), are also shown together with the locations of hinges 3 to 6 in the SHL (small circles). Hinges 1 to 2 in RssBNTD are not shown here. The SHL is well conserved among species in which σs proteolysis has been experimentally demonstrated but not between E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These proteins appear to function differently. B and C, ventral (B) and dorsal (C) views of beryllofluoride-bound RssB colored by domain as in A. The phosphoacceptor residue, D58, is shown as sticks and magnified, together with the beryllofluoride moiety in the inset. Density in the Polder omit map corresponding to the beryllofluoride ligand is contoured at 3σ and the signaling quintet residues (E14, D15, A60, S86, K108) that coordinate the Mg2+-beryllofluoride moiety and are required for phosphorylation-dependent signaling are also shown as sticks. Water molecules coordinating Mg2+ (green sphere) are shown as red spheres. Beryllofluoride is shown in stick representation. D and E, side view of beryllofluoride-bound RssB (D) and IraD-bound RssBD58P (E, PDB ID 6OD1) colored by domain organization as in (A). Structures were oriented based on a superposition restricted to the Cα-trace of RssBNTD (r.m.s.d of 0.84 Å). The proteolytically stable IraD truncation, IraDTrunc, docks primarily on the 4-5-5 face of RssBNTD and is shown as a green transparent surface in (E). Insets highlight the conformational differences in α5 and the hinge 1 region around K108 and P109. Contacts between RssBNTD, α7, and RssBCTD are predominantly hydrophobic as indicated by the clustering of hydrophobic residues (Ile, Val, Leu, orange). Among these are well characterized residues (e.g. L214, L218, and L222). Substitution of L218 leads to resistance to anti-adaptor regulation but not anti-adaptor binding and hyperactivates RssB, possibly due to enhanced interactions with σs (32). Also shown is W143 (blue), whose sidechain inserts itself, in both structures, in a cage of hydrophobic residues, including L214 and L218. Arrow indicates relative movement of RssBCTD in the beryllofluoride and IraD-bound RssB structures. F, view of interactions between the SHL and the two domains of RssB. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted lines. Side chains are colored by atom type.

The SHL of beryllofluoride-bound RssB makes contacts with both RssBNTD and RssBCTD, including hydrogen bonds between R141 and Q79, E103 and E137 in RssBNTD and L160 and R220, Q161 and V187 in the RssBCTD. Some hydrogen bonding is water-mediated such as between R141 and L98 and V102, D144 and L98 (Fig. 2, D and F). W143, a residue with hinge-like potential at the α6a/α6b junction, also makes contacts with residues in the signaling helix α8. As seen in Figure 2D, W143 is surrounded by a cage of hydrophobic residues, including L214 and L218 that map to the signaling helix α8. This region is where Battesti et al. identified a series of residues (e.g. L214, A216, L218, A221, Fig. 2A) whose substitution results in resistance to inhibition by anti-adaptors and behave as constitutively activated for σs degradation (32).

The RssB structure observed here differs from the “closed” structure of RssBD58P bound to IraD (Fig. 2E) (34). Pairwise superposition via the Cα−traces of the RssBNTD domains reveal large structural deviations that start with the loop preceding helix α5, around residues K108/P109 (compare Fig. 2, D and E), and become amplified along α5 and the SHL due to the swiveling motion of the SHL segments that result in a 42 Å translation and a 57° rotation of RssBCTD relative to RssBCTD in the IraD-bound structure (Fig. 2E and Movie S1). RssBNTD aligns well with both crystallized, unphosphorylated and beryllofluoride-bound truncated RssBNTD, but not IraD-bound RssBNTD (Fig. S2).

Beryllofluoride binding does not unpack RssB into an open structure with stably well-separated domains

Phosphorylation of two-domain response regulators often results in conformational changes that disrupt inhibitory interactions between the receiver and effector domains and unmask target-binding surfaces (45). We previously proposed that RssB regulation is heavily dependent on structural modulation of the SHL, with activation for σs binding being associated with a more rigid linker and a more open conformation. Based on data obtained with IraD, RssB inhibition was also proposed to increase the dynamics of the linker, as evidenced by high crystallographic temperature factors of the SHL (Fig. S3A, left) and disorder of its polyglutamate motif (residues E134-E137, Figs. 2, A and E and S3) in the IraD•RssBD58P crystal structure. We now show using HDX-MS that even in apo RssB, the SHL with its polyglutamate motif is the locus of most intense exchange in solution (Fig. S3B) and that in the beryllofluoride-bound crystal structure, the RssB polyglutamate motif is not disordered as in the IraD•RssBD58P structure (Fig. 2, D and E) but adopts helical phi/psi combinations. Consistent with our hypothesis, two previously described mutations that map to the polyglutamate motif (AAA and GSGS) and believed to either rigidify the SHL via a coil-to-helix transition (RssBAAA) or make it more flexible (RssBGSGS) yielded variants that are either partially (RssBAAA) or completely inactive (RssBGSGS) adaptors in vivo and in vitro (34). However, in the absence of a structural model for apo RssB, the conformational differences described above cannot be strictly ascribed to phosphorylation. We therefore carried out two differential HDX-MS experiments, comparing RssB to IraD-bound RssB and RssB to beryllofluoride-treated RssB (Fig. 3). Deuterium exchange decreased throughout RssBNTD upon addition of IraD, but particularly on the 4-5-5 face where IraD docks, within the SHL and a short stretch of amino acids spanning part of α9 and β10 in RssBCTD (Fig. 3A). These HDX signatures are entirely consistent with the IraD contacts with RssBNTD and RssBCTD observed in the crystal structure (Fig. 3A) and validated biochemically by Dorich et al. (34) and support our interpretation that the limited contacts of IraD with RssBCTD seen in the crystal structure may involve a capture mechanism that is initiated by IraD docking onto RssBNTD, which then results in adventitious capture of a dynamic RssBCTD into a fully inhibited complex. Presumably, this process requires flexing of the SHL, which does not directly contact IraD but undergoes less HDX in its presence (Fig. 3B). Compared to apo RssB, beryllofluoride-bound RssB lacks pronounced HDX signatures in RssBCTD as seen in the consolidated representation of H-D exchange of Figure 3C. Here, data derived from different peptides and time-dependent measurements were weighted, then averaged and consolidated for each amino acid into a single relative exchange rate, as described before (46). We observe an overall reduction in exchange that is distributed within the entire receiver domain but does not extend to the rest of the protein. However, time-dependent hydrogen-deuterium buildup curves for peptides mapping to the SHL do display significantly less exchange compared to apo RssB (Fig. S4). We therefore conclude that beryllofluoride binding does not induce large conformational changes that would greatly and stably alter the packing of the two domains, but rather local changes, mostly in the receiver domain and the linker, which become more ordered. We note that limited proteolysis of RssB in the presence/absence of AcP (34), CD, and intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (Fig. S3, C–D) also revealed no significant differences upon addition of beryllofluoride. This is not expected for a phosphorylation-dependent stable global conformational change but is consistent with local, small changes and perhaps altered RssBCTD dynamics.

Figure 3.

IraD and beryllofluoride binding induce clear HDX signatures and increase order in RssBNTD.A and B, solvent exchange kinetics of the IraD-bound RssB (A) and beryllofluoride-bound RssB (B) were assessed using differential HDX-MS relative to free RssB. The changes in percent deuterium uptake were averaged and consolidated for each amino acid and overlaid onto the IraD-bound RssBD58P structure (PDB ID 6OD1) and the beryllofluoride-bound RssB structure reported here. Gray and white regions of the protein indicate no significant changes in exchange and no sequence coverage, respectively. IraD is colored in purple and is shown as a ribbon and transparent surface. C, consolidated view of changes in deuterium exchange in the RssB protein upon binding beryllofluoride or IraD. Color coding is according to the percent change in hydrogen-deuterium exchange color key shown in panel A. Regions of no significant change are color-coded in gray, while regions of no sequence coverage are white. The polyglutamate motif is highlighted in an orange-shaded box. HDX-MS, hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry.

RssB phosphorylation is modulated differentially by hinges articulating α5 and the SHL

Consistent with the role of the SHL in serving as the primary target for RssB regulation, we note that SHL conformational differences between RssB structures arise due to motion of the SHL helical segments, with multiple articulating hinges potentially utilized differentially to achieve both activated and inhibited RssB states. We define six such potential hinge regions (Fig. 4A). These are highly conserved in organisms experimentally confirmed to undergo σs proteolysis but are not conserved in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa RssB-like protein (Fig. 2A). While this is the closest RssB homolog of known structure (PDB IDs 3EQ2 and 3F7A, unpublished), it has not been shown to function as an adaptor protein. In the crystal structure, it adopts an open dumbbell architecture stabilized via dimerization mediated by a central coiled coil with characteristic knobs-into-holes interactions (Fig. S3E). These are absent in RssB, as previously noted (34).

Figure 4.

RssB is organized around six hinges and features an SHL that undergoes disorder-to-order transitions. A, view of RssB with residues that serve as potential hinges highlighted in CPK representation. The polyglutamate motif is colored dark orange. B and C, side-by-side view of the SHL in the IraD-RssBD58P complex (dark purple, B) and beryllofluoride-bound RssB (magenta, C). Structures were oriented based on a superposition of RssBCTD (not shown for simplicity, r.m.s.d. of 0.57 Å), which results in a good alignment of α7, but not of α5, α6a, and α6b. The polyglutamate motif is dark orange. D, in vitro σs degradation mediated by RssB hinge variants. RssB-dependent degradation by WT or variant RssB, and ClpXP was performed as described in Experimental procedures with and without AcP. Data from three or more technical replicates are presented as mean ±s.d. Statistical analysis was performed using Sidak’s multiple comparison test (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, n.s. not significant). Additional analysis is presented as Fig. S5A. E, in vivo functional analysis of hinge mutants in a fluorescent reporter system. Plasmid derivatives carrying rssB mutant alleles were introduced into TLN001, a strain carrying an σs-mCherry translational fusion sensitive to RssB-dependent degradation, a rssB deletion, and a deletion of rpoS. In these plasmids, rssB is expressed from its native promoter; the rpoS mutant reduces expression from that promoter, providing more sensitivity to detect partial loss of function. Strains were streaked on LB ampicillin plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C and then imaged as described (Experimental procedures). In the absence of RssB, fluorescent signal from the σs-mcherry is high (no degradation); in the presence of the rssB+ plasmid, fluorescence is lost (σs-mCherry is degraded). F, in vitro assays of RssB hinge variant phosphorylation by AcP. Reactions were initiated by the addition of 15 mM AcP, incubated at 23 °C, and stopped at the indicated timepoints by the addition of loading buffer. Samples were run on 10% Phos-Tag gels. Shown are means ± s.d. (n = 3, technical replicates) together with one representative gel. Uncropped gels are shown as Fig. S6A. G, pull-down assay probing the RssB–σs interaction in the absence and presence of beryllofluoride. RssB was incubated with beryllofluoride for 15 min on ice before addition to 6His-σs–charged Ni-NTA resin. Shown are means ± s.d. (n ≥ 3, technical replicates), and statistical analysis was performed using Sidak’s multiple comparison test (∗ 0.01 < p < 0.05, ∗∗ 0.001 < p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ 0.0001 < p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). Gel data are shown as Fig. S6B and additional statistical analysis as Fig. S5B. AcP, acetyl phosphate.

Hinges 1 and 2 (P109 and L124) demarcate α5, which is shorter, straight, and displaced as also seen in the beryllofluoride-bound RssBNTD truncation, contrasting with the kinked conformation seen when bound to IraD (Fig. S2 and Movie S1). A kinked-straight conformational transition likely sterically impinges on RssBCTD upon phosphorylation and may force it to slightly repack. While IraD can bind to and inhibit both RssB and RssB∼P, its Ki for RssB∼P is higher than for RssB (32), consistent with RssBCTD docking onto the 4-5-5 face in the presence of beryllofluoride.

The last four hinges are located either in the loop preceding SHL (S129; F131) or along the SHL (Fig. 4A). The SHL largely maintains its helical segmented structure, with the C-terminal α7 helix strongly coupled to RssBCTD, together with which it moves as a rigid body relative to RssBCTD. The rest of the hinges are positioned where either α6 splits into α6a and α6b (W143, hinge 4), in between the helical segments (P150, hinge 5) or on the loop connecting to RssBCTD (P162;P163, hinge 6) (Fig. 4, A and B and Movie S1).

To assess the role of the hinge residues in RssB function, we employed a newly developed fluorescence-based in vivo assay for monitoring RssB adaptor function, in vitro phosphorylation, and reconstituted degradation assays using mutants in the hinge residues (Fig. 4, D–G). We observed modest or no functional defects in vitro or in vivo for rssBP109S, rssBW143R, and rssBP150T, consistent with earlier studies (32). Significant defects were observed for rssBL124H, rssBF129A;S131A, and rssBP162A;P163A both in vivo and in vitro (Figs. 4, D and E and S5).

In a phosphorylation time course assay, only one variant, RssBL124H, displayed severe defects, reaching only about 10% phosphorylation after 15 min, while the RssBP162A;P163A variant displayed an intermediate defect (Figs. 4F and S6A). Thus, the inability to be phosphorylated may account for the loss of activity for these mutants. Notably, variant RssBF129A;S131A, defective in vivo and in vitro, was phosphorylated to WT levels, suggesting that in this mutant, the RssBNTD is unperturbed, yet some other activity essential for degradation is severely compromised. We note that all the RssB variants were purified from the soluble fraction of E. coli lysates, suggesting that they are folded. All the single mutant variants used here were also previously shown to be binding and be sensitive to inhibition by at least one anti-adaptor in the genetic screens of Battesti et al., where they were first isolated (32), further supporting that they are not unfolded (Table S2). Furthermore, RssBF129S;S131A is phosphorylated to WT levels, and while RssB P162A;P163A is somewhat impaired, it is still competent for phosphorylation (Fig. 5 and Table S2). We recognize that we cannot rule out small scale, local unfolding and emphasize that variants may display CD spectra (and thermostabilities) different from WT, suggesting a different orientation of the helical segments and flanking domains.

Figure 5.

HDX signatures upon binding of σsto RssB in the presence of beryllofluoride.A, stimulation of RssB phosphorylation by σs quantified using immunoblotting with anti-polyhistidine and anti-RssB antibodies (Table S1). Shown are means ± s.d. (n = 3). S.F. denotes stimulation factor at the 1 min timepoint. B and C, solvent exchange kinetics of σs-bound RssB relative to beryllofluoride-bound RssB was assessed using differential HDX-MS. The change in percent deuterium uptake of RssB peptides were averaged and consolidated for each amino acid (Experimental procedures), color coded (B), and overlaid onto the the beryllofluoride-bound RssB model reported here (C). Gray and white regions of the protein indicate no significant differences in exchange between beryllofluoride-bound RssB in the absence/presence of σs and no sequence coverage, respectively. Residues critical for σs binding are shown as CPK models. Exchange rates (B and C) colored according to the color scale shown in (C). D, in vivo assay of adaptor function of RssB variants carrying mutations close to or on the 4-5-5 face and in the polyglutamate motif. Analysis was carried out as for Figure 4E. HDX-MS, hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry.

We can think of three nonmutually exclusive reasons why RssB variants may fail to support degradation, (1) decreased σs binding, (2) decreased ClpX binding, and (3) blocked RssB recycling, perhaps due to excessively tight and/or nonproductive interactions. The affinity of RssB for ClpX, with which it associates via the Zn2+-binding N-terminal domain of ClpX, ClpXZBD, is low in the absence of σs (27) and challenging to quantify. We thus focused on the interaction with σs, which we probed using pull-down assays. There is a good correlation between the pattern of functional defects observed and σs binding, with defective variants RssBL124H and RssBP162A;P163A displaying little σs binding and little or no dependence of degradation on AcP (Figs. 4G and S5). Thus, we conclude that hinge 2, in between the RssBNTD and SHL, is particularly important for both RssB phosphorylation and σs binding. The hinge 6 variant, while somewhat deficient for phosphorylation, has an additional defect in σs binding. RssBF129A;S131A, carrying hinge mutations within the SHL, had levels of σs binding equal to WT in the absence of BeF3 - but bound at only ∼50% of WT levels in its presence. Thus, at least one aspect of the defect in this mutant would appear to be the inability to properly respond to phosphorylation or the phosphomimic, but the defect in activity is more drastic than the defect in σs binding.

RssB harbors multiple binding determinants for σs recognition

We consider here two possible explanations for the defects observed in Figure 4; hinge substitutions such as L124H, F129A S131A and P162A;P163A may compromise σs degradation by virtue of being located at the σs interface or by preventing conformational rearrangements needed for σs recruitment and hand-off. To further probe for interactions with σs, we took advantage of the observation that RssB phosphorylation is stimulated by σs, particularly at early timepoints (Figs. 5A and S7A), which are most relevant for an organism resuming growth and with a doubling time on the order of tens of minutes. Stimulation of phosphorylation is consistent with RssB:σs complex formation inducing conformational changes not only in σs (47) but also in RssB. RssBP162A P163A shows no σs-dependent stimulation of phosphorylation, reflecting its low binding to σs. RssBF129A S131A (not defective for phosphorylation and still able to bind σs) shows mild inhibition instead of simulation in the presence of σs, suggesting that this mutant may block important conformational changes upon σs binding.

A recent study employing HADDOCK simulations of RssBNTD and truncated σs (σs-R3, residues 161–238) in conjunction with NMR-derived restraints placed σs-R3 on top of the phosphorylation site, adjacent to the 4-5-5 face (Fig. S7B). This would, in principle, result in tight coupling between phosphorylation and the weakening of contacts with σs as the phosphoaspartyl moiety would presumably clash with K173 (35), a σs residue critical for the interaction (24). This model is, however, at odds with reports that beryllofluoride and AcP enhance σs:RssB interactions (27, 29, 30, 48, 49) (also shown here in Fig. 1). Micevski et al demonstrated that σs docks to both the RssBNTD truncation and also to an SHL-RssBCTD fusion, albeit with lower affinity (30). We probed for σs:RssB interactions using HDX-MS in the presence of beryllofluoride and the absence/presence of σs. There is little evidence of HDX signatures in the region on top of the phosphorylation site where σs-R3 presumably docks (Figs. 5, B and C and S7B), but instead we see clear differences across the 4-5-5 face, particularly on α4 and β5, the loop C-terminal to α5 and the SHL, including α6a/α6b. A modest increase in H-D exchange is also seen in the N-terminal half of the signaling helix, correlating with the α8 hyperactivating or class II mutations described by Battesti et al. (Fig. 2A) and proposed to enhance RssB–σs interactions via a conformational change of the signaling helix (32).

The HDX data of Figure 5, B and C point to the 4-5-5 face, the β4-α4 loop, and the SHL as important for the interaction with σs and suggest that helix α5 (residues 113–123) does not make direct contacts with σs as no HDX signatures are observed in this region. Critically, in our previous study, we identified the RssBD104A variant on the 4-5-5- face as inactive (34) and a similar behavior was noted by others for the K108D variant (30, 32). K108 is also close to the 4-5-5 face and reaches close to the phosphoacceptor residue as part of the quintet of residues critical for phosphorylation-dependent signal transduction (inset, Fig. 2C). Using our fluorescent reporter system, we probed RssB variants carrying mutations on or close to the 4-5-5 face (RssBR99D, RssBD104A) and in the SHL (RssBAAA and RssBGSGS, described above) for function (Fig. 5D) and σs interactions (Fig. 4G). All of the variants in this set were defective for σs binding with the exception of RssBAAA, which exhibited about 75% binding relative to WT in the presence of beryllofluoride. To establish if phosphorylation may be involved in the reduced activity of these variants, we also employed phosphorylation assays both in the presence and absence of σs with one small modification. Because the electrophoretic mobility of RssB∼P is the same as that of σs, we used Western blotting rather than Coomassie staining to probe for stimulation of phosphorylation. Critically, RssBGSGS, RssBR99D, and RssBD104A, unlike WT, show reduced binding to σs in vitro and in vivo (Figs. 4G, 5D and S7C), and hence no stimulation of phosphorylation by σs (Fig. 5A). However, they reach slightly higher levels of net phosphorylation than WT RssB (rightmost panel, Fig. 5A). The poor activity of RssBP162A;P163A suggests that proper positioning of RssBCTD is particularly important for stimulated phosphorylation, perhaps due to the requirement for contacts with RssBNTD or the SHL driving binding of σs to RssBNTD. Altogether, these data support our hypothesis that the 4-4-5 face of RssB, the SHL, and the loops N terminal to them are critical for σs recognition and that hinge 6, located far away from the 4-5-5 face, plays a particularly important functional role.

Discussion

RssB, the sole adaptor responsible for delivery of σs to the ClpXP protease, was identified more than 2 decades ago as the first response regulator to function as an adaptor and mediate protein–protein interactions with ClpX (22, 26, 27). Shortly thereafter, it was shown that D58 within its receiver domain is the sole phosphoacceptor site (29). Despite multiple attempts to identify the source of in vivo RssB phosphorylation, it remains insufficiently understood. Kinase ArcB and small phosphodonor AcP have been implicated (29, 50), but it appears likely that RssB may be phosphorylated by multiple yet-to-be-defined kinases, possibly ensuring redundancy and efficient destruction of σs during active growth or upon return to active growth. This would also be consistent with the findings of Yamamoto et al. that, at least in vitro, RssB can be phosphorylated by CheA, ArcB, and UhpB (51). Phosphatase activities may also be involved in shifting the equilibrium towards the OFF form, particularly under conditions when σs levels must increase (Fig. 6). Chromosomal substitution of the phosphoacceptor aspartate with nonphosphorylatable alanine, while increasing the σs half-life fivefold, did not result in a strong phenotype under selected conditions of either starvation or recovery from stress (36). This is somewhat surprising given that under active growth, RssB levels are low (52), so one would expect that for it to be effective; RssB would also have a high affinity for its target, which is not the case in the absence of phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). However, the RssB promoter is σs-controlled and under homeostatic control due to σs degradation (28), and so because σs levels fluctuate, it is possible that phosphorylation is critical only under specific conditions and during a narrow time window. Moreover, while high affinity interactions with σs may drive delivery complex formation, they may also preclude and interfere with substrate hand-off.

Figure 6.

Model for RssB activation and σsdegradation.A, RssB conformations are stabilized by phosphorylation: While the sources of in vivo phosphorylation and dephosphorylation have not been fully defined, data here and elsewhere suggest that the unphosphorylated RssB likely samples a variety of conformations, stabilized in a more compact state by phosphorylation. There is no evidence for RssB dimerizing, different from many other response regulators. B, stressed cell: under stress conditions, anti-adaptors (green hexagon here) are synthesized and bind to RssB, stabilizing inactive conformations (as for IraD) or blocking access of σS (blue, shown with four domains). C, cell recovering from stress: the situation depicted here will exist both during recovery and during unstressed growth. This work presents the structure of RssB-P (red box in figure). σS preferentially binds to the phosphorylated form of RssB. While a structure is not yet available for RssB-P bound to σS, HDX and RssB phosphorylation data here support contacts of σS with RssBNTD and SHL, resulting in some loosening of the RssBNTD/RssBCTD contacts. This complex then binds to ClpX, delivering σS to the proteolytic subunit. RssB is released and reused; in this model, we assume it remains phosphorylated, but that is not yet known.

Our approach circumvents some of the limitations of previous studies by trapping WT full-length RssB with the beryllofluoride phosphomimic (Figs. 1 and 2) and by revealing not only phosphorylation-dependent changes in protein plasticity (Figs. 3 and 4) but also RssB interactions with σs (Figs. 4 and 5). Consistent with an earlier hypothesis (34, 44), we present evidence for the 4-5-5 face being important for the adaptor function of RssB and likely σs binding. While other models cannot be ruled out, our data together with previous published findings are suggestive of (1) phosphorylation strongly rigidifying RssBNTD, (2) phosphorylation altering RssBCTD dynamics due to changes in the SHL, and (3) σs binding being multipartite, with binding determinants in both RssBNTD and possibly the SHL (Fig. 6).

We favor the following sequence of events. Phosphorylation leads to conformational changes around D58, and possibly the SHL, which preorganize a high affinity–binding site for σs, possibly by coil-helix transitions in the polyglutamate motif. σs binding to the SHL and RssBNTD is accompanied by conformational changes that unmask the 4-5-5 face and allow for full engagement of σs (Fig. 6).

Based on our HDX data (Figs. 3 and 5) and the behavior of RssB variants carrying mutations on or close to the 4-5-5- face (RssBR99D, RssBD104A in Figs. 4 and 5), with basal phosphorylation comparable to WT, yet little dependence of phosphorylation on σs due to reduced binding, we propose that this consolidated interaction is due to σs docking onto the 4-5-5 face. σs-mediated stimulation of phosphorylation may extend the half-life of RssB∼P, allowing for a time window that is sufficiently long for structural rearrangements and full σs hand-off to ClpXP.

Building upon our earlier model (34), we speculate here that the RssB molecule does in fact adopt a more open conformation but that this conformation requires both phosphorylation and docking of σs. The open form could be achieved by widening of the cleft between RssBNTD and RssBCTD, with σs serving as a spacer to disrupt contacts between the receiver and effector domain, which are generally inhibitory for response regulator function (53, 54).

In some response regulators, phosphorylation-dependent activation is achieved through a second modality of structural rearrangement, dimerization (45). This is mediated usually, but not always, by the 4-5-5 face as observed in the OmpR/PhoB and NtrC subfamilies (55, 56, 57). Dimerization has been shown to be part of the mechanism of action of the Caulobacter crescentus adaptor, RcdA. RcdA dimers can readily be detected in solution, and critically RcdA and cargo both compete for the same RcdA interface. This competition determines the fate of RcdA itself since RcdA homodimers are degraded by ClpXP, while bound cargo stabilizes RcdA against proteolysis (58, 59). If this model were applicable to the RssB system, it would predict that RssB dimerizes through the 4-5-5 face. Thus, by RssBCTD docking onto the 4-5-5 face, phosphorylation (and subsequently σs recruitment) may interfere with dimerization and would protect from lowering of RssB pools by proteolysis of the RssB homodimer.

The potential role of RssB oligomerization in the overall mechanism remains unclear and is not considered in Figure 6. In contrast to RcdA, the evidence for RssB dimerization is weaker. RssB oligomerization has been detected by bacterial two-hybrid assay in clpX and clpXP-deleted strains (32), consistent with the model above. However, in vitro, dimerization and higher order oligomerization has only been detected by chemical crosslinking of full-length RssB (34) and by gel filtration and X-ray crystallography of isolated RssBNTD, but not with the full-length protein (49). The contacts holding the RssBNTD dimer together in crystallo are different from those seen in other response regulators (45), do not involve the 4-5-5 face, and cannot be ruled out as a crystallization artifact. Third, dimerization has not been seen with full-length RssB via size-exclusion chromatography coupled to multi-angle light scattering detection at concentrations well above physiological (34), and importantly, phosphorylation by AcP does not appreciably alter the oligomerization state of RssB (Fig. 1B). Altogether, these observations suggest that RssB dimers, if they occur in solution, are scarce, transient, and may require stabilization by one or more binding partners. Data so far argue against σs-promoting dimerization as the detected σs:RssB complex in Figure 1A is consistent, within the limitations of size-exclusion chromatography, with a 1:1 stoichiometry, as proposed earlier (30). It is possible that under certain conditions, such as when RssB engages the ClpX hexamer via ClpXZBD, the local concentration of RssB will rise high enough for RssB to dimerize and that these dimeric species get degraded by ClpXP, rather than recycled. Regardless, the phosphorylation-dependent masking of the 4-5-5 face, where all of the structurally characterized anti-adaptors (e.g. IraD and IraM) dock, may be a mechanism designed to partially shield this binding surface from anti-adaptors upon recovery from stress, when σs degradation must resume yet anti-adaptor levels may still be elevated. In combination with the stepwise and multipartite engagement of σs, this provides precise regulation both under recovery from stress and upon exposure to stress, when IraD and IraM outcompete σs from RssB by utilizing the 4-5-5 face for docking (32, 60).

While combined approaches like ours are beginning to unravel many facets of σs regulation, further structural studies of RssB in complex with its other binding partners will be instrumental to satisfactorily dissect the mechanistic basis for this hub of interactions supported by RssB. Our study presents a novel type of phosphorylation-dependent rearrangement that highlights the dynamic role of α5 and of the SHL and adds to the diversity of mechanisms used by the members of the large and ancient family of response regulators to signal upon phosphorylation.

Experimental procedures

RssB production and crystallization

RssB and His-tagged RssB were purified by a succession of nickel-affinity chromatography and gel filtration as described (34). For crystallization, we used the nontagged RssB construct (pBD1 in Table S1). BeSO4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and NaF (Sigma) were premixed for 15 min on ice in a 1:6 M ratio and added to RssB protein concentrated to 1 mg/ml to a final concentration of 1 mM BeSO4 and 6 mM NaF. Protein was dispensed manually in hanging drops on 24-well VDX plates (Hampton Research), and high-quality crystals were obtained with 300 mM magnesium nitrate hexahydrate, 22% w/v PEG 3350. The crystallization cocktail was supplemented with 25% PEG 400 for purposes of cryoprotection. Flash-cooling was achieved by plunging into liquid nitrogen.

Structure determination and refinement

Diffraction data was collected at beamline 24-ID-C (Argonne National Laboratory), indexed, and integrated using XDS (61), followed by scaling with Aimless. The structure was phased using molecular replacement with the homologous domains of PDB ID 6OD1 as search models using the Molecular Replacement Phaser module in PHENIX (62). Iterative refinement and model building was performed using PHENIX (62) and Coot (63). Data collection, refinement statistics, and PDB IDs are presented in Table 1. Diffraction images have been deposited in the SBGrid Data Bank (64) under dataset ID 1032.

Production and purification of RssB variants

Plasmids encoding RssB variants were constructed by Gibson assembly or obtained commercially and verified using Sanger or nanopore whole-plasmid DNA sequencing. For protein production, plasmids were transformed into BL21-A1 OneShot (Thermo Fisher Scientific) chemically competent E. coli and grown in LB media supplemented with 0.5% glucose and appropriate antibiotics. Cultures were induced at OD600 = 0.3 with 0.2% L-arabinose and 0.5 mM IPTG and grown for 3 h at 30 °C before harvesting. The obtained pellet was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use. On the day of purification, the pellet was thawed on ice in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH8, 500 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 15 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF and protease inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 15 μg/ml DNAse I. Cell lysate was passed through a homogenizer, centrifuged, and filtered before loading onto an Ni-charged 5 ml column (Nuvia, Bio-Rad). Unbound protein was washed off with IMAC-15 (20 mM Tris–HCl pH8, 500 mM NaCl, 15 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 2 mM BMe), followed by an ATP wash (20 mM Tris–HCl pH8, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP, 15 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and a repeated IMAC-15 wash. Protein was eluted via a gradient from 0 to 100% IMAC-300 (20 mM Tris–HCl pH8, 500 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Peak fractions containing protein were confirmed by SDS-PAGE, pooled, and the tag cleaved by addition of Prescission protease and overnight dialysis (20 mM Tris–HCl pH8, 200 mM NaCl, 15 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Tag and protease were removed by a reverse Ni-NTA step, and protein was collected from flow-through before injecting on a HiTrap Q column (Cytiva) to remove contaminants. Unbound protein was washed off with low salt buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH8, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol), then bound protein was eluted with a 0 to 100% gradient of high salt buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH8, 1000 mM NaCl, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Flow-through and wash fractions containing RssB were pooled and concentrated before supplementing with glycerol to 25%, then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

Analytical size-exclusion chromatography

RssB and σs were dialyzed overnight against 20 mM Tris–HCl pH8, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol. RssB was phosphorylated by the addition of 25 mM lithium potassium acetyl phosphate (AcP, Sigma), followed by incubation for 15 min on ice. Hundred microliter samples for RssB, σs, RssB+ σs, RssB∼P, Rpos (in both the presence and absence of AcP), RssB∼P+σs were prepared at 15 μM. A Superdex200 Increase (GE Healthcare) column was equilibrated with dialysis buffer (±25 mM AcP) and calibrated with molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad) prior to sample loading. Peak fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

RssB phosphorylation assays

RssB and RssB variants were dialyzed overnight against 20 mM Tris–HCl pH8, 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT at 4 °C. Phosphorylation reactions were assembled with 15 mM lithium potassium AcP (Sigma) at 21 °C with RssB constructs and, where appropriate, with σs present in a 1:1 M ratio. Reactions were pre-incubated with σs for 15 min before addition of AcP. At indicated timepoints after addition of AcP, 10 μl samples containing 1.5 μg RssB were withdrawn from the total sample and mixed with 4 μl 4xLDS (0.25 M Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 8% SDS, 0.2 M DTT, 0.04% bromophenol blue). To account for potential gel-to-gel variability in dephosphorylation due to sample preparation and electrophoresis, for each gel, we performed an internal calibration based on loading identical amounts of phosphorylated RssB. For this internal calibration, RssB was first phosphorylated for 40 min before stopping the reaction by addition of 4xLDS. Unphosphorylated (0%) and phosphorylated samples (40 min timepoint) were mixed at different ratios and 14 μl samples were loaded on each gel. For electrophoresis, we utilized 10% SuperSep Phos-tag precast gels (Fujifilm Wako), which were run with 1xTris-Tricine buffer (0.1 M Tris base, 0.1 M Tricine, 0.1% SDS) for 90 min at 150V at 4 °C. Gels were fixed for 10 min (50% methanol, 10% acetic acid) and stained with Coomassie Blue for imaging on a gel doc (Bio-Rad). Band intensities were quantified using Image Lab (Bio-Rad, https://www.bio-rad.com/en-us/product/image-lab-software?ID=KRE6P5E8Z) and data plotted using Prism 9 (GraphPad, https://www.graphpad.com/features). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Immunoblotting

PhosTag gels were washed 3 x 10 min in 1xTransfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, pH 8.3) supplemented with 10 mM EDTA before semi-dry transfer onto nitrocellulose membrane (Li-Cor) using Trans-Blot SD (Bio-Rad; 15V, 15 min; 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, pH 8.3, 20% methanol). Membranes were blocked for 30 min in 5% milk in PBS before overnight incubation with anti-RssB antibody (1:5000, rb, in 5% milk in PBS). The next day, membrane was washed 3 × 10 min with PBST (PBS supplemented with 0.04% Tween-20) before incubation with anti-rb antibody (1:10,000, goat, IRDye 800CE, Li-Cor), followed by a 5 min wash with PBS before imaging using a ChemiDoc MP (Bio-Rad) imaging system. Afterward, the membrane was incubated for 2 h with an anti-His antibody (1:2000, ms, Sigma-Aldrich, in 5% milk in PBS). The membrane was then washed 3 x 10 min with PBST before incubation with anti-rb antibody (1:10,000, goat, IRDye 680RD, Li-Cor), followed by a 5 min wash with PBS and imaged using a ChemiDoc MP (Bio-Rad) imaging system.

Pull-down assays

RssB, RssB variants, and His-tagged σs were dialyzed o/n against 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 15 mM imidazole, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol. RssB and RssB variants were treated with with 1 mM BeF3 for 15 min on ice. BeF3 was prepared by mixing equal volumes of 50 mM BeSO4 and 300 mM NaF and keeping the mixture on ice for 15 min before addition to protein. Pull-downs were performed in 66 μL reactions containing 4.5 μM. His-tagged σs was added to phosphorylated/unphosphorylated RssB in Micro Bio-Spin Chromatography columns (Bio-Rad) before taking 6 μl of the input for SDS-PAGE analysis and adding 40 μl of prepared HisPur Ni-NTA resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Resin was charged with 6 μM His-tagged σs for 60 min on a wheel at 4 °C before washing off unbound protein and adding RssB or RssB variants. Samples were incubated for 60 min on a wheel at 4 °C before flow through was collected by centrifugation for 1 min at 1000 rcf. Resin was washed four times with 300 μl dialysis buffer and last with 40 μl of buffer. Phosphorylated samples were washed with dialysis buffer supplemented with 1 mM BeF3. Complexes were eluted by incubation with IMAC-600 ± BeF3− (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 600 mM imidazole, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, ± BeF3−) for 5 min at 4 °C followed by centrifugation for 2 min at 1000 rcf. Input and elution samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by gel staining with Coomassie Blue and imaging. Band intensities were quantified using Image Lab (Bio-Rad) and plotted using Prism 9 (GraphPad). Experiments were performed in replicates (n ≥ 3). Percent efficiencies were estimated by calculating the ratio of RssB to σs based on band intensities. The mean of the replicates obtained in the presence of beryllofluoride was set to 100%, to which the ratio of the band intensities in the absence of beryllofluoride was compared.

Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence

Protein samples were dialyzed overnight against 50 mM Tris–HCl pH8, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and diluted to 2 μM prior to the experiment. Measurements were performed in triplicate using a Fluoromax-4 spectrofluorometer (Horiba). One hundred fifty microliters of protein solution ± 1 mM beryllofluoride or 6 mM NaF were transferred to a quartz cuvette and measured over a wavelength range of 300 to 500 nm in 1 nm increments with excitation at 290 nm at 25 °C. Spectra were corrected for background.

Circular dichroism

Protein was dialyzed overnight against 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP and diluted to 2.5 μM prior to the experiment. The assay was performed on a Jasco J-815 CD spectrometer. Measurements were performed at 25 °C in a 2 mm pathlength cuvette over a wavelength range of 200 to 260 nm with a speed of 50 nm/min. Samples were measured in triplicates with three acquisitions per sample and background corrected.

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry

Peptide identification

Differential HDX-MS experiments were conducted as previously described with a few modifications (65). Peptides were identified using tandem MS (MS/MS) with an Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Q Exactive, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Product ion spectra were acquired in data-dependent mode with the top five most abundant ions selected for the product ion analysis per scan event. The MS/MS data files were submitted to Mascot (Matrix Science) for peptide identification. Peptides included in the HDX analysis peptide set had a MASCOT score greater than 20 and the MS/MS spectra were verified by manual inspection. The MASCOT search was repeated against a decoy (reverse) sequence, and ambiguous identifications were ruled out and not included in the HDX peptide set.

HDX-MS analysis

Five microliters of 10 μM RssB ± BeF3− was diluted into 20 μl D2O buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0; 150 mM NaCl; 10 mM MgCl2; 1 mM TCEP) and incubated for various time points (0, 10, 60, 300, 900, and 3600s) at 4 °C. The deuterium exchange was then slowed by mixing with 25 μl of cold (4 °C) 3 M urea, 50 mM TCEP, and 1% TFA. Quenched samples were immediately injected into the HDX platform. Upon injection, samples were passed through an immobilized pepsin column (1 mm × 2 cm) at 50 μl min−1, and the digested peptides were captured on a 1 mm × 1 cm C8 trap column (Agilent) and desalted. Peptides were separated across a 1 mm × 5 cm C18 column (1.9 μl Hypersil Gold, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a linear gradient of 4%–40% CH3CN and 0.3% formic acid, over 5 min. Sample handling, protein digestion, and peptide separation were conducted at 4 °C. Mass spectrometric data were acquired using an Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Exactive, Thermo Fisher Scientific). HDX analyses were performed in triplicate, with single preparations of each complex form. The intensity-weighted mean m/z centroid value of each peptide envelope was calculated and subsequently converted into a percentage of deuterium incorporation. This is accomplished determining the observed averages of the undeuterated and fully deuterated spectra and using the conventional formula described elsewhere (66). Statistical significance for the differential HDX data is determined by an unpaired t test for each time point, a procedure that is integrated into the HDX Workbench (https://hdxworkbench.com) software (46). Corrections for back exchange were made on the basis of an estimated 70% deuterium recovery and accounting for the known 80% deuterium content of the deuterium exchange buffer.

HDX-MS analysis was carried out similarly on an IraD:RssB complex reconstituted in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio. For analyzing σs-bound RssB, the complex was also reconstituted by mixing purified RssB and σs in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio in the presence of beryllofluoride.

Data rendering

The HDX data from all overlapping peptides were consolidated to individual amino acid values using a residue averaging approach. Briefly, for each residue, the deuterium incorporation values and peptide lengths from all overlapping peptides were assembled. A weighting function was applied in which shorter peptides were weighted more heavily and longer peptides were weighted less. Each of the weighted deuterium incorporation values were then averaged to produce a single value for each amino acid. The initial two residues of each peptide, as well as prolines, were omitted from the calculations. This approach is similar to that previously described (67).

Strain construction

The activity of RssB mutants was tested by expressing the mutant allele on a pHDB3 plasmid derivative, in strain TLN001, expressing a σs-mCherry translational fusion and measuring fluorescence on plates. TLN001 is an rpoS::kan derivative of NM818. NM818 was constructed in several steps. NRD1166, a strain that carries the lambda Red functions at the λatt site and a zeo-kan-pBAD-ccdB counter-selectable marker preceding mCherry at the lac locus (68), was electroporated with a PCR fragment made by amplifying the rpoS750 fragment from MG1655 genomic DNA and extending from the rpoS promoter within nlpD through nt 750 of the ORF using primers RpoS750-mCherNRD1166F and RpoS750-mCherNRD1166R (Table S1). The PCR fragment also carried 40 nt homologies to the zeo and mCherry genes respectively. Appropriate recombinants were selected by plating on LB with 1% arabinose, to induce the pBAD promoter, killing cells expressing CcdB. Recombinants were purified and screened for loss of the kanR gene. The final insert was sequenced and tested for fluorescent expression. This strain was then transduced by P1 to rssB::tet to generate strain AAP1. The latter was then transformed with pSIM6 (lambda Red, ampR) plasmid and made electrocompetent. Primer set oNM1036 and oNM1037 were used to amplify a gentamicin resistance cassette from NM397 (69). The gentamicin cassette was electroporated and recombineered in to replace the Zeo marker upstream of the fusion and generate NM818.

In vivo assays of adaptor function

In vivo RssB activity was determined qualitatively in a complementation assay. In this assay, RssB and mutant derivatives were expressed from a medium copy number pHDB3 plasmid derivative, in which rssB is expressed from its native promoter (48). rssB mutant alleles were introduced into the pHDB3 plasmid by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent Technologies). The plasmids were transformed into strain TLN001, containing a constitutively expressed rpoS-mcherry translational fusion, which is degraded dependent upon RssB. This fusion carries 250 amino acids of σs fused to the second codon of mCherry. The chromosomal copy of rssB was inactivated, as was the chromosomal copy of rpoS. Because the rssB promoter is transcribed dependent upon σs (28), active alleles of RssB, allowing full degradation of σs, would lead to less RssB from the plasmid, while inactive RssB alleles would be expressed at a higher level. To eliminate this feedback effect and have all alleles expressed at the lower, σs -independent level, an rpoS::kan allele was introduced into the reporter strain. The resulting strain (Cp6-Genta-Cp17-rpoS750-mcherry ΔrssB::tet ΔrpoS::kan) was transformed with the pHDB3 derivatives, ampicillin resistant colonies selected, streaked on LB ampicillin plates, and incubated overnight as indicated in the figure legends. Colony fluorescence was then determined by using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP imaging system. The setting was Cy3 (602/50, Red) for mCherry with auto optimal exposure and Cy7 (835/50, Green) for background with auto rapid exposure. Images were saved as .tiff files.

Bacterial two hybrid assays

In the bacterial two hybrid assay used here, expression of cAMP and therefore expression of cAMP-dependent genes is dependent upon reconstitution of adenylate cyclase from Bordetella pertussis from two plasmids, each expressing a portion of the cyclase fused to a protein of interest. Cyclase activity, assayed here by the ability to ferment lactose on Lactose MacConkey indicator plates containing antibiotics to select for the plasmids, is present if the fused proteins interact. Here the T18 domain of cyclase was fused to derivatives of RssB and the T25 domain of cyclase was fused to σs, to evaluate the interaction of σs and RssB. Because the T25- σs fusion protein will be degraded by RssB and ClpXP (48), strain BA100, a rpoS- clpP- derivative of BTH101, was used as the host. Parental plasmid pBA034 ([UT18C-rssB+, AmpR) or plasmids carrying rssB mutations were transformed along with the pBA025 (pKT25- σs, KanR) into BA100, AmpR KanR colonies selected, and restreaked on lactose MacConkey Amp Kan plates and incubated overnight at 30 °C. The images were captured by using Epson Perfection V700 Photo.

Reconstituted degradation assays

ClpX (70), ClpP (71), and σs (27) were purified as previously described. σs was labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 carboxylic acid, succinimidyl ester (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as recommended by the manufacturer. The degree of labeling was 2 mol/mol. Protein concentrations given are for σs and RssB monomers, ClpX hexamers, and ClpP tetradecamers. Degradation reactions (30 μl) were assembled in buffer B [20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 5% glycerol (vol/vol)] containing 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 25 mM acetyl phosphate, 0.1 μM ClpX, 0.17 μM ClpP, 2.6 μM fluorescent σs, and 50 nM RssB. After incubation for 15 min at 23 °C, 70 μl of buffer B containing 15 mM EDTA was added to stop the reactions. Degradation products were isolated with Nanosep 10 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration devices (Pall; prewashed with 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.01% Triton X-100) by centrifugation at 14,000g for 10 min. Eluent fluorescence was measured using a Tecan Spark plate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths of 490 and 525 nm, respectively. Eluent fluorescence from reactions containing no ATP and no RssB was subtracted from the data shown, 7.3 ± 0.2 pmol. The degradation end point of 15 min was within the linear phase of degradation as indicated by time course experiments under identical reaction conditions.

Data availability

Data and reagents are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Raw diffraction patterns are available from the SBGrid Data Repository as data set #1032. Model coordinates and structure factor intensities are deposited in the Protein Data Bank under PDB ID 8T85. HDX-MS data are available in the FigShare repository.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

This work used NE-CAT beamlines (GM124165) at the Advanced Photon Source and the Proteomics Facility at Brown University. We thank staff at NECAT 24ID for excellent beamline support, Dr Martin Buck and Dr Bing Liu for sharing the coordinates of the RssBNTD:σs-R3 model, and Dr Bruce Pascal for depositing HDX-MS data with FigShare. We also thank Ms V. Frankovich for technical assistance during the early stages of the project and Thu-Lan Lily Nguyen for constructing the TLN001 strain.

Author contributions

C. B., S. N., N. M., M. F., and A. M. D. methodology; C. B., J. S., S. T., J. R. H., N. M., and R. K. resources; C. B., J. S., S. N., S. T., J. R. H., N. M., R. K., and A. M. D. investigation; C. B., S. N. formal analysis; C. B. visualization; S. W., S. G., P. R. G., and A. M. D. supervision; C. B., J. S., S. N., S. T., J. R. H., N. M., R. K., M. F., S. W., S. G., P. R. G., and A. M. D. writing–review and editing; S. W., S. G., P. R. G., and A. M. D. funding acquisition; A. M. D. conceptualization; A. M. D. data curation; A. M. D. writing–original draft; A. M. D. project administration.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants (R01GM121975; R35GM121975) and a Salomon Research Award from Brown University to A. M. D., and the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, to S. G. and S. W. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Ursula Jakob

Supporting information

The movie shows the structure of beryllofluoride-bound RssB reported here morphing into the structure IraD-bound RssBD58P (PDB ID 6OD1). The coloring is by domain (RssBNTD, cyan; RssbCTD, pink; and SHL, magenta). IraD is shown in green. Our data predict that IraD binding onto the 4-5-5 face significantly weakens the affinity for σs by masking RssBNTD-binding determinants, in agreement with previous experimental findings (30,32,35).

References

- 1.Gottesman S. Trouble is coming: signaling pathways that regulate general stress responses in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:11685–11700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.005593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klauck G., Serra D.O., Possling A., Hengge R. Spatial organization of different sigma factor activities and c-di-GMP signalling within the three-dimensional landscape of a bacterial biofilm. Open Biol. 2018;8:180066. doi: 10.1098/rsob.180066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collet A., Cosette P., Beloin C., Ghigo J.M., Rihouey C., Lerouge P., et al. Impact of rpoS deletion on the proteome of Escherichia coli grown planktonically and as biofilm. J. proteome Res. 2008;7:4659–4669. doi: 10.1021/pr8001723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poole K. Bacterial stress responses as determinants of antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2069–2089. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mah T.F., O'Toole G.A. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:34–39. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01913-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krogfelt K.A., Hjulgaard M., Sorensen K., Cohen P.S., Givskov M. rpoS gene function is a disadvantage for Escherichia coli BJ4 during competitive colonization of the mouse large intestine. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:2518–2524. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2518-2524.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merrell D.S., Tischler A.D., Lee S.H., Camilli A. Vibrio cholerae requires rpoS for efficient intestinal colonization. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:6691–6696. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6691-6696.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacour S., Landini P. SigmaS-dependent gene expression at the onset of stationary phase in Escherichia coli: function of sigmaS-dependent genes and identification of their promoter sequences. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:7186–7195. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7186-7195.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patten C.L., Kirchhof M.G., Schertzberg M.R., Morton R.A., Schellhorn H.E. Microarray analysis of RpoS-mediated gene expression in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2004;272:580–591. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber H., Polen T., Heuveling J., Wendisch V.F., Hengge R. Genome-wide analysis of the general stress response network in Escherichia coli: sigmaS-dependent genes, promoters, and sigma factor selectivity. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:1591–1603. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1591-1603.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong G.T., Bonocora R.P., Schep A.N., Beeler S.M., Lee Fong A.J., Shull L.M., et al. The genome-wide transcriptional response to varying RpoS levels in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 2017;199 doi: 10.1128/JB.00755-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baharoglu Z., Krin E., Mazel D. RpoS plays a central role in the SOS induction by sub-lethal aminoglycoside concentrations in Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Genet. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uddin M.J., Jeon G., Ahn J. Variability in the adaptive response of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella typhimurium to environmental stresses. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019;25:182–192. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutierrez A., Laureti L., Crussard S., Abida H., Rodriguez-Rojas A., Blazquez J., et al. beta-Lactam antibiotics promote bacterial mutagenesis via an RpoS-mediated reduction in replication fidelity. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1610. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L., Xu Q., Tu J., Ge Y., Liu J., Liang F.T. Increasing RpoS expression causes cell death in Borrelia burgdorferi. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lange R., Hengge-Aronis R. Identification of a central regulator of stationary-phase gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1991;5:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lange R., Barth M., Hengge-Aronis R. Complex transcriptional control of the sigma s-dependent stationary-phase-induced and osmotically regulated osmY (csi-5) gene suggests novel roles for Lrp, cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein-cAMP complex, and integration host factor in the stationary-phase response of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:7910–7917. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7910-7917.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange R., Fischer D., Hengge-Aronis R. Identification of transcriptional start sites and the role of ppGpp in the expression of rpoS, the structural gene for the sigma S subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4676–4680. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4676-4680.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lange R., Hengge-Aronis R. The cellular concentration of the sigma S subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli is controlled at the levels of transcription, translation, and protein stability. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1600–1612. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.13.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muffler A., Traulsen D.D., Fischer D., Lange R., Hengge-Aronis R. The RNA-binding protein HF-I plays a global regulatory role which is largely, but not exclusively, due to its role in expression of the sigmaS subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:297–300. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.297-300.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Repoila F., Majdalani N., Gottesman S. Small non-coding RNAs, co-ordinators of adaptation processes in Escherichia coli: the RpoS paradigm. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:855–861. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muffler A., Fischer D., Altuvia S., Storz G., Hengge-Aronis R. The response regulator RssB controls stability of the sigma(S) subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1996;15:1333–1339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klauck E., Lingnau M., Hengge-Aronis R. Role of the response regulator RssB in sigma recognition and initiation of sigma proteolysis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;40:1381–1390. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker G., Klauck E., Hengge-Aronis R. Regulation of RpoS proteolysis in Escherichia coli: the response regulator RssB is a recognition factor that interacts with the turnover element in RpoS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:6439–6444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Y., Gottesman S. Regulation of proteolysis of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:1154–1158. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1154-1158.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pratt L.A., Silhavy T.J. The response regulator SprE controls the stability of RpoS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:2488–2492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y., Gottesman S., Hoskins J.R., Maurizi M.R., Wickner S. The RssB response regulator directly targets sigma(S) for degradation by ClpXP. Genes Dev. 2001;15:627–637. doi: 10.1101/gad.864401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pruteanu M., Hengge-Aronis R. The cellular level of the recognition factor RssB is rate-limiting for sigmaS proteolysis: implications for RssB regulation and signal transduction in sigmaS turnover in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;45:1701–1713. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouche S., Klauck E., Fischer D., Lucassen M., Jung K., Hengge-Aronis R. Regulation of RssB-dependent proteolysis in Escherichia coli: a role for acetyl phosphate in a response regulator-controlled process. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;27:787–795. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Micevski D., Zeth K., Mulhern T.D., Schuenemann V.J., Zammit J.E., Truscott K.N., et al. Insight into the RssB-mediated recognition and delivery of sigma(s) to the AAA+ protease, ClpXP. Biomolecules. 2020;10:615. doi: 10.3390/biom10040615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao R., Mack T.R., Stock A.M. Bacterial response regulators: versatile regulatory strategies from common domains. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Battesti A., Hoskins J.R., Tong S., Milanesio P., Mann J.M., Kravats A., et al. Anti-adaptors provide multiple modes for regulation of the RssB adaptor protein. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2722–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.229617.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hryckowian A.J., Battesti A., Lemke J.J., Meyer Z.C., Welch R.A. IraL is an RssB anti-adaptor that stabilizes RpoS during logarithmic phase growth in Escherichia coli and Shigella. mBio. 2014;5 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01043-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorich V., Brugger C., Tripathi A., Hoskins J.R., Tong S., Suhanovsky M.M., et al. Structural basis for inhibition of a response regulator of sigma(S) stability by a ClpXP antiadaptor. Genes Dev. 2019;33:718–732. doi: 10.1101/gad.320168.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]