Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the ultrastructural and immunohistochemical changes in the granular convoluted tubule (GCT) of rodents' submandibular gland (SMG) upon theinduction of chronic renal failure.

Material and methods

Thirty young adult Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized into three groups: the Control group, rats received no intervention; the Sham group, rats underwent surgical incision without nephrectomy; the Experimental group, rats underwent surgical procedures to induce chronic renal failure. Afterward, SMG was examined for histological and ultrastructural changes and immunohistochemical staining for Renin.

Results

Histologically, the experimental group demonstrated cytoplasmic vacuolization within the seromucous acini and ducts. Several GCTs were proliferating, whereas others exhibited degenerative changes in the form of disturbed cytoplasmic architecture. On the ultrastructural level, both acini and ductal segments showed degenerative changes Interestingly, immunohistochemical examination of the lining cells of GCT and intralobular ducts of the experimental group revealed the presence of Renin.

Conclusion

Renal failure induced histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural variations within GCTs of SMG.

Keywords: Renal failure, Granular convoluted tubules, Submandibular salivary gland, Renin

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Renin immunohistochemical localization in rats' salivary glands.

-

•

Renal failure had an impact on salivary gland.

-

•

The area ratio of granular convoluted tubule of salivary gland increased in renal failure.

-

•

Renal failure caused ultrastructural variations within salivary gland tubules.

1. Introduction

The granular convoluted tubule (GCT) of rodents' submandibular gland (SMG) is a distinct ductal segment frequently present in the kidney and rodents' SMG. It is located between the striated and intercalated ducts.1 At sexual maturity, this specialized duct portion develops from the proximal parts of striated ducts. Due to the profound effect of androgens and glucocorticoids on their growth, differentiation, and size, they are more developed in males than in females.2 Histologically, the GCT is a portion of rodents' SMG similar to the mucous tubule and has often been mistaken for it.1 It is lined with simple columnar epithelium with basally situated nuclei, a few basal infoldings, and many apical electron-dense serous secretory granules of different sizes. Ultrastructurally, GCT is composed of mosaic cell types, including transitional, pillar, and granular cells, as well as dark granular cells.3

Functionally, each type of these specialized ductal cells has a unique ability to synthesize various enzymes, growth factors, and polypeptide hormones.3 Barka4 stated that the GCT of SMG might be regarded as a component of the diffuse neuroendocrine system of the digestive tract due to the presence of more than 25 biologically active factors in the cells of the GCT. These factors were grouped into four categories: growth and differentiation, digestion, intracellular regulation, and homeostasis. In addition, Renin is a kallikrein gene family member. Walker et al.5 immunolocalized two important hormonal factors, epidermal and nerve growth factors, within the GCT of SMG.

Moreover, Amano et al.6 localized hepatocyte growth factor and the transforming growth factor-beta in the secretory granules of the GCT. Interestingly, these growth factors' serum levels depend on the SMG.7 Consequently, they proposed that cells of GCT could have a dual role that enables them to perform both exocrine and endocrine functions.

Secretion of GCT-specific polypeptides has an intimate association with the functional disturbance of various organs. For instance, changes in the ultrastructural features of GCT following hypophysectomy or supra-physiological conditions of androgenic and thyroid hormone supplementation.3 Additionally, many previous reports proved that GCT-specific secretory products are induced by multihormonal control of adrenocortical, thyroid, and androgen hormones.8

Salivary glands and kidneys have functional and morphological similarities, primarily in their capacity to reabsorb sodium and possibly other substances from a primary secreted fluid.9 Additionally, hypoxia or nephrectomy induced GCT cells to serve as an external erythropoietin production site, which is considered the main precursor for renin production, thus compensating for its deficiency.10 Furthermore, rodent SMG has been reported to contain peptidases similar to renal vasoactive peptides, kallikrein, and renin.11

Renin is an essential hormone that controls blood pressure and other physiological functions. In addition to its secretion by juxtaglomerular kidney cells, there was evidence of local renin production in various extrarenal sites, including the mouse SMG granular convoluted tubules.12,13 Hence, the SMG fine convoluted tubules appear to have a significant relationship with the kidney.

Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the effect of induced chronic renal failure on the histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural photomicrographs of SMG granular convoluted tubules.

2. Materials and methods

A summary of materials and methods is represented in the flow chart of the Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart explaining the rat's randomization and the variables assessed throughout the study.

2.1. Animals

(30) two-month young adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (125−150 g) were kept at 26 ± 1 °C. Before surgery, they were acclimated to laboratory conditions for seven days. The sample size was based on a previous study.14 The significance level was the sample size was more than this equation confidence interval was 95 %, and the actual power was 97.69 %. The sample size was calculated using a computer program, G Power version 3.1.9. An oversizing of the sample was done to compensate for the potential failure and increase the results' validity. Thus, the sample size was 30. Animals were randomly distributed using a computer-generated list of random numbers to one of three groups as follows: Control (n = 10): animals did not undergo any intervention; Sham (n = 10): animals underwent surgical procedures without nephrectomy or artery ligation; Experimental (n = 10), rats underwent surgical procedures to induce chronic renal failure. All rats were treated following the Ethical Committee's guidelines at the Faculty of Dentistry, Egypt (#R-OB-10-21-26). All procedures were held following ARRIVE guidelines.

2.2. Induction of chronic renal failure

To induce renal failure, rats underwent a single-phased 5/6 nephrectomy surgery. Xylazine hydrochloride 2 % (Sigma-Aldrich Pty Ltd) with ketamine hydrochloride 10 % (Sigma-Aldrich Pty Ltd) at a dosage of 10 mg/kg and 125 mg/kg, respectively, were injected intraperitoneally into rats to induce anesthesia.15 On the surgical table, rats were positioned in a ventral position, trichotomy, and disinfected with ethanol (70 %). Then, the right kidney was removed (Fig. 1A), followed by segmental infarction of two-thirds of the left kidney with silk ligatures (Fig. 1B), as reported by Shapiro et al.16

Post-operative care for rats included the administration of flunixine 5 mg/kg body weight (Biokema SA, Crissier-Lausanne, Switzerland) subcutaneously every 12 h for seven days. The rats were anesthetized, and the specimens of SMG were dissected carefully. Finally, at the end of the experiment, the animals were euthanized with an overdose of anesthesia.

2.3. Serum analysis

Eight weeks after surgery, blood samples were withdrawn from all groups' tail veins using blood collection tubes containing EDTA 15 %. Afterward, creatinine and the concentrations of blood urea nitrogen were measured to ensure the induction of chronic renal failure, as illustrated by Romero et al.17

2.4. Histological and ultrastructural examination

Samples from the right SMG were instantly fixed in a 10 % buffered formalin solution, rinsed with running water before dehydration in ascending grades of ethanol, and finally immersed in paraffin. Serial five μm sections were stained with eosin and hematoxylin before examining histological sections utilizing a light microscope (Leica ICC50 HD), about 20 for each specimen.

Furthermore, immunohistochemical staining was done for renin detection in SMG using anti-renin antibodies (Renin Rabbit PAb with dilution 1-10000) (Catalog No.: A1585) (Neomarkers, USA through Santa Cruz Biotechnology Egypt). All images used in the image-J analysis (National Institutes of Health in the USA) had a standard magnification power of ×400. Five slides from each specimen were used for research, and five captures were taken from each section (5x5= 25) image. The evaluation of immunohistochemical staining was semiquantitative, scoring18,19 (0 for negative renin expression, 1 for positive renin expression). The assessment was done blindly by three observers (pathologists).

Left SMG specimens were divided into two equal samples for electron microscopy. After that, specimens were instantly placed in a blend of 1 % of glutaraldehyde as well as 4 % of paraformaldehyde before being post-fixed for 2 h in 1 % osmium tetraoxide, dehydrated in ascending ethanol grades, embedded in epon 812. Ultra-thin cuts (50 nm) were sectioned utilizing the RMC-USA ultra-microtome, picked on copper grids, stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate, and examined with JOEL-TEM.

2.4.1. Statistical analysis

The quantitative data obtained from serum analysis and GCT area ratio (Fig. 2) From the captured images on the analysis system for each group were tabulated and statistically analyzed using CO-STAT analysis (version 6.4). Descriptive statistics expressed numerical variables as mean, standard deviation, and range. One-way ANOVA and post hoc (Tukey) tests were used to compare quantitative data between groups. Significance was determined at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 26). Descriptive statistics will express numerical variables as mean, standard deviation, and range, and nominal data will be represented by frequency, percent, and median. P value < 0.05(*) was considered a significant difference & P-value <0.001(**) was considered a highly significant difference.

Fig. 2.

light microscopic image of rat SMG, as displayed on the Image Monitor. The GCT areas are outlined, and their number is recorded. (A) Control group as displayed on the image monitor. (B) Experimental group that reveals an obvious increase in GCTs (H&E stain. Orig. mag. X 400).

3. Results

3.1. Renal failure on serum levels of creatinine and urea

The results obtained revealed a substantial elevation in creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels in the experimental group compared to those of the control as well as sham groups (Table 2). The experimental group exhibited substantially elevated levels of blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine than control and sham-operated groups. Nevertheless, no substantial changes were detected between the control and sham-operated groups.

Table 2.

Renal failure on serum levels of creatinine and BUN. * Significant.

| parameter | Group I (control) | Group II (sham) | Group III (experimental) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.76 ± 0.07* |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 30 ± 8.1 | 25 ± 7.4 | 69 ± 9.6* |

3.2. Histological results

3.2.1. Light microscopic results

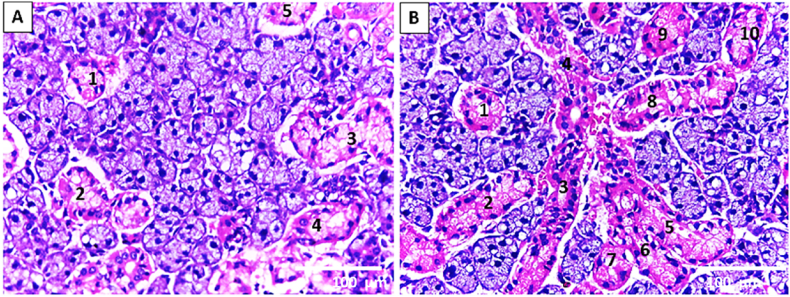

The SMG of the control and sham groups showed almost normal acinar and ductal structures (Fig. 3. A; Fig. 4. A). However, the seromucous acini of SMG of the experimental group depicted cytoplasmic vacuolization (Fig. 3. B &D). Attractively, the GCT in the experimental group revealed atypical features; some were proliferating that simulate newly developed ductal segments (the branched structure) (Fig. 3. B; Fig. 4. B, C&D), whereas others showed degenerative changes in the form of disturbed cytoplasmic architecture (Fig. 3. C&D).

Fig. 3.

Light microscopic image of rat SMG illustrates (A) the control group's seromucous acini A and GCT. (B–D) the seromucous acini and GCT of the experimental group. (B) It reveals the proliferation of GCT (black arrows) (embryonic-like branched structure). (C,D) It shows seromucous acini with cytoplasmic vacuolization (white arrows) together with the disturbing architecture of GCT (arrowhead). (H&E stain. Orig. mag. a, b x400; c x1000).

Fig. 4.

Light microscopic image of rat SMG illustrates (A) the almost normal seromucous acini and GCT of the sham group. (B,C) the seromucous acini and GCT of the experimental group reveal a marked proliferation of GCT. (D) It shows widely branched proliferated GCTs in between the seromucous acini (H&E stain. Orig. mag. A X1000; B, D X100; C X400).

3.2.2. Immunohistochemical results

The SMG of both control and sham groups exhibited negative cellular expression of anti-renin antibodies in both acini and ducts (Fig. 5 A & B). Conversely, the experimental group depicted positive expression of anti-renin at the GCT and intralobular ducts lining cells. However, the gland acini had a negative anti-renin expression (Fig. 5 C & D).

Fig. 5.

Photomicrograph of immunolocalization of anti-renin antibodies in right SMG: (A , B) showing negative cellular and nuclear expression of anti-renin antibodies in both acini (yellow arrow) and ducts (red arrow) of control as well as sham groups, respectively. (C) showing lobes of SMG of experimental group after eight weeks of chronic Induction of renal failure (D) Higher magnification of black boxed area at (C) showing positive localization of cellular expression of anti-renin at the GCT and intralobular ducts lining cells (red arrows) with some nuclear immunohistochemical reaction. In addition, there is a negative expression of anti-renin in the gland acini (yellow arrow). (Anti-renin antibodies, A, B & D x 400 and C x 100).

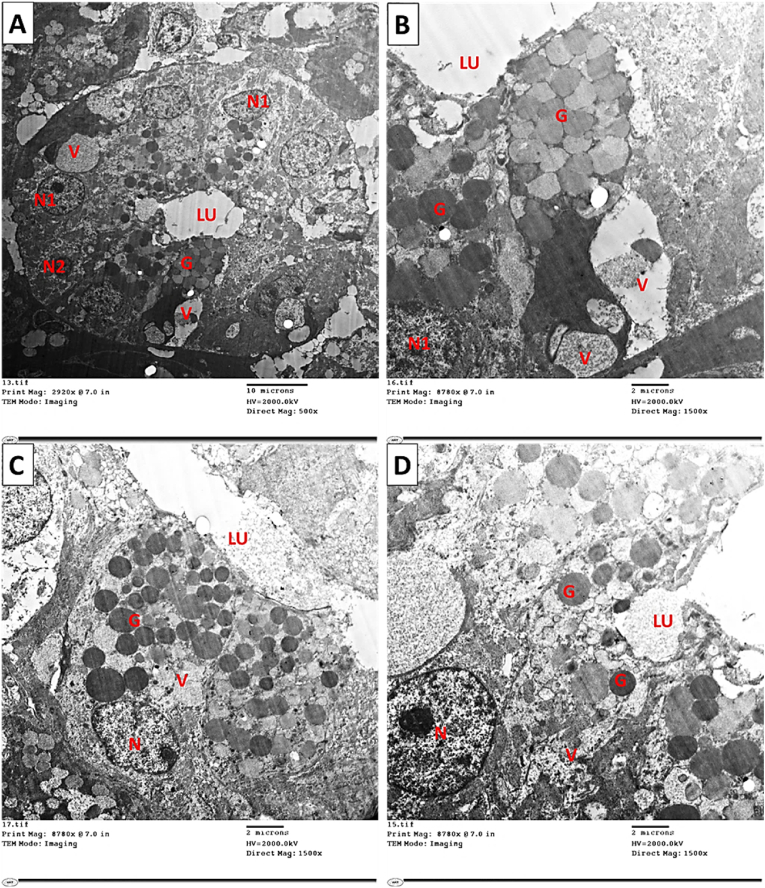

3.2.3. Transmission electron microscope results (Ultrastructural changes)

SMG examination utilizing the electron microscopy of the sham and the control groups showed normal ultrastructural elements (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). SMG showed ultrastructural variations of the acinar portions and ducts in the experimental group. Acini and ducts appeared degenerated, and the most observed feature was the presence of many cytoplasmic vacuolations (Fig. 9). Moreover, organelles such as secretory granules displayed variations in their size and electron density (Fig. 9). Regarding GCTs of sham and the control groups, it showed duct wall formed from principal simple columnar epithelial cells containing secretory granules of nearly equal electron density, with small differences in granules size. In addition, well-outlined pillar cells between the main cells with granules of lower electron density (Fig. 8. A & B). In addition, the experimental group showed cells with euchromatic nuclei and pycnotic nuclei, and the cells showed pleomorphism in their granular contents and some large cytoplasmic vacuolization (Fig. 9. A & B). Also, the GCT cells depicted variation in granules' electron density near the lumen and some cytoplasmic vacuolization, and the pillar cells showed ill-defined outlines. (Fig. 9. C & D).

Fig. 6.

Electron micrograph of SMG of control and sham groups showing (A,B) Normal pyramidal seromucous acinar cell with basal active nucleus (N) and normal appearance of RER occupying mainly the cell's basolateral part. The acinar cell appears loaded with electron-lucent secretory granules (G), which appear to merge. (C) SMG of the experimental group showing: Seromucous acinar cell with basal nucleus (N) and small cisterna of RER (arrow). The acinar cell appears loaded with both electron lucent and electron-dense secretory granules. Notice the presence of cytoplasmic vacuoles (V) of different sizes. Similarly, (D) Seromucous acinar cell with basal heterochromatic nucleus (N) and small cisterna of RER (arrow). The acinar cell appears packed with electron-lucent secretory granules that merge. (Mic. Mag. A, B, C, and D X 1500).

Fig. 7.

Electron micrograph of SMG of control and sham groups showing. (A,B) Almost normal SDs are lined with columnar cells that have basal euchromatic nuclei (N), basal striations (arrow), and a few electron-dense secretory granules (G) near the lumen (Lu). (Mic. Mag. An X 600 and B X 1000).

Fig. 9.

Electron micrograph of SMG of the experimental group showing changes in GCT. (A,B) Cells of GCT, which contain euchromatic nuclei (N1) as well as pycnotic nucleus (N2), the cells show pleomorphism in their granular contents (G) and some large cytoplasmic vacuolization (V). (C,D) Two different cells of GCT contain euchromatic nuclei (N). The cells depict variations in granules' electron density (G) near the lumen (LU) and some cytoplasmic vacuolization (V). (Mic. Mag. A X 500 and B, C, D X 1500).

Fig. 8.

Electron micrograph of SMG of (A) the control and(B) sham group showing GCT.The duct wall is formed from principal simple columnar epithelial cells (E) containing secretory granules (G) of nearly equal electron density, with small differences in granule size. In addition, well-outlined pillar cells (P) between the principal cells with granules of lower electron density. (Mic. Mag. A and B X 1500).

3.3. Statistical results

3.3.1. The granular convoluted tubules area ratio

Image analysis revealed that the experimental group had a significantly higher ratio of GCT to total image area than the control and sham groups. The statistical analysis demonstrated a significant difference between the experimental group's mean GCT area ratio and the control and sham groups. Conversely, no significant difference was detected between the mean GCT ratio of the sham and control groups (Table I).

Table 1.

The ratio of the mean GCT area relative to that of the entire picture among the three different groups: * Significant, NT Not significant.

| Groups | Mean | ±SD | F | P. Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I (control) | 16.72 | 4.20 | 14.095 | <0.001 | (GI, GIII) * |

| Group II (sham) | 13.15 | 6.18 | (GII, GIII) * | ||

| Group III (experimental) | 35.82 | 8.43 | (GI, GII)NT |

4. Discussion

This study aims to investigate the histological, ultrastructural changes and the immunohistochemical reaction of GCT of rodents' SMG after inducing chronic renal failure in rats.

It is worth mentioning that the work on experimental animals in preclinical studies is essential in the medical field. Rats are commonly used in laboratory studies as they are remarkably similar to humans and share about 90 % of their genes with humans.20,21 A single-phased 5/6 nephrectomy surgery of the rat was selected as a model of chronically induced renal failure because it is convenient and causes renal function deficiencies.22,23 To our knowledge, previous studies used a nephrectomy model to analyze the parameters of salivary composition and their association with changes in serum due to the disease.24, 25, 26, 27 However, none of these studies demonstrated the histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural changes in salivary glands.

First, we investigated whether nephrectomy could alter SMG histological and ultrastructural features. Indeed, mutual histological and ultrastructure changes were reported in the gland acinar and GCT elements. Histologically, cytoplasmic vacuolizations were seen in the seromucous acini of SMG of the experimental group. Myers and McGavin28 recognized cytoplasmic vacuolization in salivary glands as an early degeneration phase presenting an elevation in cell volume and size due to cell inability to stabilize normal homeostasis. Interestingly, the GCTs in the experimental group revealed atypical features, and some were proliferating, forming embryonic-like branched structures. Several studies found embryonic-like branched designs ending with acinar cells in SMG at the period of regeneration that is absent in control SMG. Elghonamy et al. and Cotroneo et al.29,30 postulated that newly generated acini develop from unique branched structures existing in this tissue since they exhibited a configuration extremely similar to designs appearing in the embryonic SMG throughout branching morphogenesis. They suggested that SMG regeneration follows cytodifferentiation's perinatal pathway. Therefore, this regeneration can be attributed to the relationship of the SMG granular convoluted tubules with kidney impairment, which coincides with previous studies.12,13

On the ultrastructural level, GCTs showed degenerative changes and some degree of degenerative changes in the form of disturbed cytoplasmic architecture. Maciejczyk et al.31 reported that chronic kidney diseases increase lipids and salivary protein oxidation, leading to the progression and deterioration of salivary gland function in the form of oxidative damage. This finding coincides with our results of degenerated acini and ducts two months after the 5/6 nephrectomy. In addition, GCT cells were reported to undergo remarkable atrophy in hypophysectomised male mice in the form of a marked decrease in size and number and the basal infoldings of these cells. This finding might indicate changes in the secretory nature and the conversion of GCT cells into immature GCT phenotypes. It was shown that the GCT cells could uniquely produce bioactive polypeptides and hormonal elements,32 which agrees with our detected renin immunostaining, especially within the GCT ductal portion.

Second, we investigated whether nephrectomy could induce renin antibodies immunohistochemical staining in the SMGs. Immunohistochemical results showed that SMG of the control and sham groups had a negative cellular expression of anti-renin antibodies in both acini and ducts. This finding had some resemblance with previous studies that suggested the presence of Renin in all the GCT of postnatal SMG cells in adult male mice.33 In contrast, the experimental group showed positive expression of anti-renin antibodies at the GCTs and intralobular ducts lining cells but not in the gland acini. These findings suggest a relationship between SMG granular convoluted tubules and the kidney that might be compensatory for the marked decrease in renin secretion after nephrectomy, which aligns with Ingelfinger et al.34 Regarding the nuclear immunohistochemical reaction to renin antibodies, a previous study suggested that the total protein secretion as well as the mRNA expression of the renin-angiotensin system, could be reduced with an angiotensin II receptor blocker in the parotid gland,35 this might account the relation of salivary gland tissue activity, amount of saliva and total protein secretion, to renin enzyme. Thus, the nuclear reaction might be related to this activation. However, renin enzyme is not commonly found in rat submandibular glands, but it was confirmed in mice.36 Besides, it was found that it is important for regulating blood pressure and plasma concentration both locally and systemically.37 As Renin has expression in other animal species, we suggest that rat submandibular gland metabolism might be changed to accommodate the body condition developed from renal failure.

Third, coinciding with GCTs ductal regeneration, the granular convoluted tubular area ratio was markedly increased in the experimental group above the control and sham groups. Statistical analysis demonstrated a significant difference between the experimental group's mean GCT area ratio and the control group. On the contrary, no significant difference was noticed between the sham group's mean granular convoluted tubules ratio and the control group. This finding might be due to an increase in renin secretion, as Laoide et al.38 suggested, who stated that the male secretion rate of mouse SMG renin increased due to cytodifferentiation of GCT cells in response to the increased androgen level at puberty.

Clinically, Renin is normally secreted from juxtaglomerular cells of the kidney that cleave angiotensinogen into angiotensin-1 and then into angiotensin-2 via angiotensin-converting enzyme. Angiotensin-2 interacts with angiotensin-1 receptors, causing inflammation, vasoconstriction, fibrosis, proliferation, and oxidative stress.39,40 Furthermore, saliva flow is known to be reduced in hypertensive rat models.41 These may reflect the oral manifestation of chronic renal failure, such as xerostomia, hairy tongue, poor oral hygiene, gingivitis, and periodontitis.42, 43, 44, 45

However, we have functionally proved Renin's existence in GCTs of SMG by immunohistochemical staining after nephrectomy. Further investigations using specific labels are required. In addition, the detection of renin gene expression and cellular localization using real-time PCR and in situ hybridization are needed to confirm the immunohistochemical results in the present study.

5. Conclusion

To our knowledge, this may be the first study to report that nephrectomy in rats persuades formation of Renin by the submandibular salivary gland as was proved immunohistochemically in GCTs ductal portion. This functional change was associated with ultrastructural and histological alterations. This finding suggests the relationship between SMG GCTs and the kidney that might compensate for the ablation of renin secretion after nephrectomy.

Declaration of competing interest

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Acknowledgement

This research was partially funded by Zarqa University, Jordan.

Contributor Information

Wafaa Yahia Alghonemy, Email: Wafaa_yehya@dent.tanta.edu.eg.

Fatema Rashed, Email: F.rashed@zu.edu.jo.

Mai Badreldin Helal, Email: Mai_helal@dent.tanta.edu.eg.

References

- 1.Amano O., Mizobe K., Bando Y., Sakiyama K. Anatomy and histology of rodent and human major salivary glands—overview of the Japan salivary gland society-sponsored workshop. Acta Histochem Cytoc. 2012;45(5):241–250. doi: 10.1267/ahc.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gresik E.W. The granular convoluted tubule (GCT) cell of rodent submandibular glands. Microsc Res Tech. 1994;27(1):1–24. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070270102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mori M., Yoshiaki T., Kunikata M. Biologically active peptides in the submandibular gland role of the granular convoluted tubule. Acta Histochem Cytoc. 1992;25(1-2):325–341. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barka T. Biologically active polypeptides in mouse submandibular gland. Acta Histochem Cytoc. 1980;13(1):9–22. doi: 10.1177/28.8.7003006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker P., Weichsel M.E., Eveleth D., Fisher D.A. Ontogenesis of nerve growth factor and epidermal growth factor in submaxillary glands and nerve growth factor in brains of immature male mice: correlation with ontogenesis of serum levels of thyroid hormones. Pediatr Res. 1982;16(7):520–524. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amano O., Iseki S. Expression and localization of cell growth factors in the salivary gland: a review. Kaibogaku Zasshi. 2001;76(2):201–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aloe L., Alleva E., B hm A., Levi-Montalcini R. Aggressive behavior induces release of nerve growth factor from mouse salivary gland into the bloodstream. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(16):6184–6187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.16.6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurabuchi S., Gresik E.W., Hosoi K. Additive and/or synergistic action (downregulation) of androgens and thyroid hormones on the cellular distribution and localization of a true tissue kallikrein, mK1, in the mouse submandibular gland. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52(11):1437–1446. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6333.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekker M., Tronik D., Rougeon F. Extra-renal transcription of the renin genes in multiple tissues of mice and rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(13):5155–5158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gould A.B., Goodman S., DeWolf R., Onesti G., Swartz C. Interrelation of the renin system and erythropoietin in rats. J Lab Clin Med. 1980;96(3):523–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamuro T., Hori M., Nakagawa Y., et al. Tickling stimulation causes the up-regulation of the kallikrein family in the submandibular gland of the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2013;236:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dzau V.J. Vascular wall renin-angiotensin pathway in control of the circulation: a hypothesis. Am J Med. 1984;77(4):31–36. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(84)80035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganten D., Schelling P., Vecsei P., Ganten U. Iso-renin of extrarenal origin: the tissue angiotensinogenase systems. Am J Med. 1976;60(6):760–772. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90890-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bro S., Bentzon J.F., Falk E., Andersen C.B., Olgaard K., Nielsen L.B. Chronic renal failure accelerates atherogenesis in apolipoprotein e–deficient mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(10):2466–2474. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000088024.72216.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veilleux-Lemieux D., Castel A., Carrier D., Beaudry F., Vachon P. Pharmacokinetics of ketamine and xylazine in young and old Sprague-Dawley rats. JAALAS. 2013;52(5):567–570. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro J.I., Harris D.C., Schrier R.W., Chan L. Attenuation of hypermetabolism in the remnant kidney by dietary phosphate restriction in the rat. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 1990;258(1):F183–F188. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.1.F183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero A.C., Bergamaschi C.T., de Souza D.N., Nogueira F.N. Salivary alterations in rats with experimental chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2016;11(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chlipala E.A., Bendzinski C.M., Dorner C., et al. An image analysis solution for quantification and determination of immunohistochemistry staining reproducibility. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2020;28(6):428. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor C.R., Levenson R.M. Quantification of immunohistochemistry—issues concerning methods, utility and semiquantitative assessment II. Histopathology. 2006;49(4):411–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor K., Gordon N., Langley G., Higgins W. 2005. Estimates for Worldwide Laboratory Animal Use in. Published online 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tandler B., Gresik E.W., Nagato T., Phillips C.J. Secretion by striated ducts of mammalian major salivary glands: review from an ultrastructural, functional, and evolutionary perspective. Anat Rec. 2001;264(2):121–145. doi: 10.1002/ar.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang H.C., Zuo Y., Fogo A.B. Models of chronic kidney disease. Drug Discov Today Dis Model. 2010;7(1-2):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carvalho R.A., Romero A.C., Ibuki F.K., Nogueira F.N. Salivary gland metabolism in an animal model of chronic kidney disease. Arch Oral Biol. 2019;104:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2019.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovalčíková A.G., Pavlov K., Lipták R., et al. Dynamics of salivary markers of kidney functions in acute and chronic kidney diseases. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodrigues R.P.C.B., Aguiar E.M.G., Cardoso-Sousa L., et al. Differential molecular signature of human saliva using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy for chronic kidney disease diagnosis. Braz Dent J. 2019;30:437–445. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201902228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nogueira F.N., Romero A.C., da Silva Pedrosa M., Ibuki F.K., Bergamaschi C.T. Oxidative stress and the antioxidant system in salivary glands of rats with experimental chronic kidney disease. Arch Oral Biol. 2020;113 doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.104709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carvalho R.A., Romero A.C., Ibuki F.K., Nogueira F.N. Salivary gland metabolism in an animal model of chronic kidney disease. Arch Oral Biol. 2019;104:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2019.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myers R.K., McGavin M.D. Cellular and tissue responses to injury. Pathol Basis Veter Dis. 2007;4:3–62. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cotroneo E., Proctor G.B., Carpenter G.H. Regeneration of acinar cells following ligation of rat submandibular gland retraces the embryonic-perinatal pathway of cytodifferentiation. Differentiation. 2010;79(2):120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elghonamy WYI, Gaballah OM, El Amy SA. Effect of platelet rich plasma on regeneration of submandibular salivary gland of albino rats. System. 1:2..

- 31.Maciejczyk M., Szulimowska J., Taranta-Janusz K., Wasilewska A., Zalewska A. Salivary gland dysfunction, protein glycooxidation and nitrosative stress in children with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1285. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurabuchi S., Yao C., Chen G., Hosoi K. Reversible conversion among subtypes of salivary gland duct cells as identified by production of a variety of bioactive polypeptides. Acta Histochem Cytoc. 2019;52(4):59–65. doi: 10.1267/ahc.19014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurabuchi S., Hosoi K., Gresik E.W. Developmental and androgenic regulation of the immunocytochemical distribution of mK1, a true tissue kallikrein, in the granular convoluted tubule of the mouse submandibular gland. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50(2):135–145. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ingelfinger J.R., Pratt R.E., Ellison K.E., Roth T.P., Dzau V.J. Multiple sites of regulation of mouse renin expression in ontogeny. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1986;8(4-5):687–694. doi: 10.3109/10641968609046586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cano I.P., Dionisio T.J., Cestari T.M., et al. Losartan and isoproterenol promote alterations in the local renin-angiotensin system of rat salivary glands. PLoS One. 2019;14(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kon Y., Endoh D. Renin in exocrine glands of different mouse strains. Anat Histol Embryol. 1999;28(4):239–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0264.1999.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barka T. Biologically active polypeptides in submandibular glands. J Histochem Cytochem. 1980;28(8):836–859. doi: 10.1177/28.8.7003006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laoide B.M., Courty Y., Gastinne I., Thibaut C., Kellermann O., Rougeon F. Immortalised mouse submandibular epithelial cell lines retain polarised structural and functional properties. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(12):2789–2800. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.12.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alves CR. de AS. 2017. Agonista tendencioso para o receptor AT 1 exerce efeitos benéficos sobre parâmetros cardiovasculares de ratos espontaneamente hipertensos. Published online. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrario C.M., Strawn W.B. Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and proinflammatory mediators in cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(1):121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabino-Silva R., Okamoto M.M., David-Silva A., Mori R.C., Freitas H.S., Machado U.F. Increased SGLT1 expression in salivary gland ductal cells correlates with hyposalivation in diabetic and hypertensive rats. Diabetol Metab Syndrome. 2013;5(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hernández C. Oral disorders in patients with chronic renal failure. Narrative review. J Oral Res. 2016;5(1):27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rojas M.P.L., Mauricio J.M., Villasis K.R. Manifestaciones bucales en pacientes con insuficiencia renal crónica en hemodiálisis. Rev Estomatol Hered. 2014;24(3):147–154. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rebolledo Cobos M., Carmona Lorduy M., Carbonell Muñoz Z., Díaz Caballero A. Salud oral en pacientes con insuficiencia renal crónica hemodializados después de la aplicación de un protocolo estomatológico. Av Odontoestomatol. 2012;28(2):77–87. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bouattar T., Chbicheb S., Benamar L., El Wady W., Bayahia R. Dental status in 42 chronically hemodialyzed patients. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 2010;112(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.stomax.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]