Abstract

Purpose

Hip fractures in elderly have a high mortality. However, there is limited literature on the excess mortality seen in hip fractures compared to the normal population. The purpose of this study was to compare the mortality of hip fractures with that of age and gender matched Indian population.

Methods

There are 283 patients with hip fractures aged above 50 years admitted at single centre prospectively enrolled in this study. Patients were followed up for 1 year and the follow-up record was available for 279 patients. Mortality was assessed during the follow-up from chart review and/or by telephonic interview. One-year mortality of Indian population was obtained from public databases. Standardized mortality ratio (SMR) (observed mortality divided by expected mortality) was calculated. Kaplan-Meir analysis was used.

Results

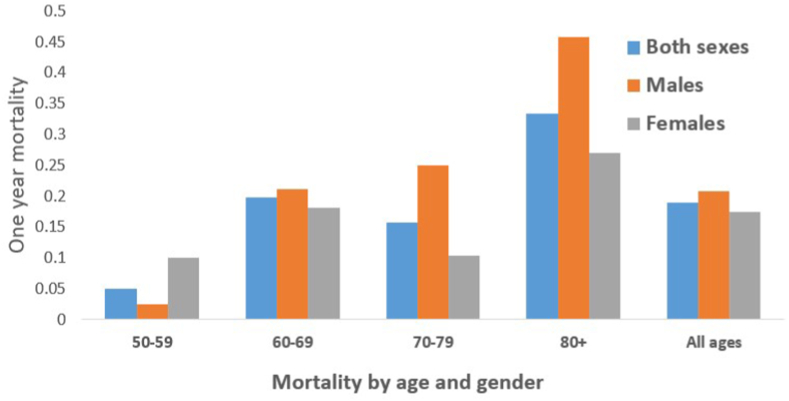

The overall 1-year mortality was 19.0% (53/279). Mortality increased with age (p < 0.001) and the highest mortality was seen in those above 80 years (aged 50 – 59 years: 5.0%, aged 60 – 69 years: 19.7%, aged 70 – 79 years: 15.8%, and aged over 80 years: 33.3%). Expected mortality of Indian population of similar age and gender profile was 3.7%, giving a SMR of 5.5. SMR for different age quintiles were: 3.9 (aged 50 – 59 years), 6.6 (aged 60 – 69 years), 2.2 (aged 70 – 79 years); and 2.0 (aged over 80 years). SMR in males and females were 5.7 and 5.3, respectively.

Conclusions

Indian patients sustaining hip fractures were about 5 times more likely to die than the general population. Although mortality rates increased with age, the highest excess mortality was seen in relatively younger patients. Hip fracture mortality was even higher than that of myocardial infarction, breast cancer, and cervical cancer.

Keywords: Hip fracture, Mortality, Excess mortality, Indian, Population, Age, Gender

Introduction

Hip fractures in the elderly population are associated with high mortality, of which the 1-year mortality was reported to be around 20% – 30%.1 The annual incidence of hip fractures in India is estimated to be over 120 fractures per 100,000 persons aged > 50 years.2 With the increasing elderly population of India, hip fractures are expected to increase in India.3 Multiple factors, such increasing age, male sex, comorbidities, cognitive impairment, and time to surgery have been suggested as important predictors of mortality in hip fracture patients.4 Despite the improvements in hip fracture care, the mortality after hip fractures appears to be high.

Prior studies have observed that the mortality of hip fractures is higher than that expected for matching population without hip fractures.5 To the best of our knowledge, no study have evaluated the excess mortality risk in Indian population. The life expectancy among Indians is lower compared to many western countries.6 So, it is possible that the high mortality of hip fractures in Indian reported in prior studies maybe a reflection of the underlying aging population, and not necessarily from sustaining the fracture. Estimating the excess mortality from hip fractures will help clinicians to estimate the impact of hip fractures on the society.

Therefore, we conducted this study to evaluate the excess mortality among the elderly with hip fractures in India. The objectives of the study were to assess 1-year mortality in a prospective cohort of hip fractures patients above 50 years, and compare the mortality of Indian population with the same age and gender obtained from public databases.

Methods

The present study was conducted prospectively at a single tertiary level trauma center in 2019 and approved by the institutional ethics committee ((IECPG-631/19.12.2018,RT-29/23.01.2019). Patients were enrolled after they agreed to participate in the study and provided written informed consent. Data were collected from medical records of the patients as well as in-person interview of the patient and their relatives.

We included all hip fractures admitted during the study period over the age of 50. This included both femoral neck as well as pertrochanteric fractures. There were a total of 377 hip fracture admissions, among which 93 patients under the age of 50 were excluded. Consent was not provided by 1 patient. Among the 283 patients who were consented, 1-year follow-up was available for 279 patients, and they were hence included for this study (Fig. 1). Mortality was assessed during the follow-up from chart review and/or by telephonic interview. Whenever possible, the cause of death was also obtained.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing the inclusion of patients.

Mortality rates for the Indian population was obtained from the United Nations mortality estimate.7 For this study, we used the age and gender specific mortality rates in 2015 – 2020. As mortality rates were given for 5-year intervals, we used the mortality rates for the median of each quintile (example, the mortality rate at age of 55 was used for the 50 - 59 cohort). For those patients aged over 80 years, we used the mortality rate at age of 85 years.

Chi-squared test and student's t-test were used to compare variables. Standardized mortality ratio (SMR) (observed mortality divided by expected mortality) was calculated. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were obtained for the age-gender specific mortality rates of hip fracture cohort assuming a binomial distribution. Kaplan-Meir analysis was used to obtain the survival estimates for 30-day, 90-day and 1-year. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with help of Stata statistical software, version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Overall, 279 patients were included out of which 53 (19.0%) patients died during the follow-up of 1-year. The in-hospital mortality rate was 3.2% (9/279) with 4 patients dying before the surgery, and 5 patients dying in the post-operative period. The demographics characteristics of patients are provided in Table 1. Mortality increased with age (p < 0.001), with the highest mortality rate over 80 years of age. Mortality in males were higher, though not statistically different (p = 0.481). Mortality were also higher due to multiple comorbidities (p = 0.009), falls as mechanism of injury (p = 0.008), use of home ambulators (p = 0.004), and no surgery (p < 0.001) (Table 1). The Kaplan-Meir curve showing the mortality of patients over 1 year is given in Fig. 2. The 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year mortalities were 3.2% (95% CI: 1.7 – 6.1), 6.8% (95% CI: 4.4 – 10.5), and 19.0% (95% CI: 14.9 – 24.1). The causes of death are detailed in Table 2. The cause of death was obtained from chart review or interview of the patients’ relatives during the phone call, and the cause could not be ascertained in 16 patients. Sepsis and pneumonia were the most common reported causes of death followed by malignancy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (n = 279).

| Variables | 1-year mortality, % | Alive (n = 226), n (%) | Dead (n = 53), n (%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | <0.001 | |||

| 50–60 | 5.0 | 57 (25.2) | 3 (5.7) | |

| 60–70 | 19.7 | 57 (25.2) | 14 (26.4) | |

| 70–80 | 15.8 | 64 (28.3) | 12 (22.6) | |

| Over 80 | 33.3 | 48 (21.2) | 24 (45.3) | |

| Gender | 0.481 | |||

| Male | 20.8 | 103 (45.6) | 27 (50.9) | |

| Female | 17.4 | 123 (54.4) | 26 (49.1) | |

| Number of comorbidities | 0.009 | |||

| 0 | 8.0 | 80 (35.4) | 7 (13.2) | |

| 1 | 23.4 | 72 (31.9) | 22 (41.5) | |

| 2 | 20.9 | 53 (23.5) | 14 (26.4) | |

| > 2 | 32.2 | 21 (9.3) | 10 (18.9) | |

| Mode of injury | 0.008 | |||

| Fall | 22.4 | 166 (73.5) | 48 (90.6) | |

| Others | 7.7 | 60 (26.5) | 5 (9.4) | |

| Ambulatory status | 0.004 | |||

| Community | 16.3 | 201 (88.9) | 39 (73.6) | |

| Home | 35.9 | 25 (11.1) | 14 (26.4) | |

| Type of fracture | 0.745 | |||

| Neck | 20.3 | 59 (26.1) | 15 (28.3) | |

| Intertrochanteric or subtrochanteric | 18.5 | 167 (73.9) | 38 (71.7) | |

| Mode of treatment | <0.001 | |||

| No surgery | 90.0 | 1 (0.4) | 9 (17.0) | |

| Arthroplasty | 20.0 | 44 (19.5) | 11 (20.8) | |

| Fixation | 15.4 | 181 (80.1) | 33 (62.3) |

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meir curve showing the cumulative mortality during the follow-up of 1 year among elderly Indian hip fractures.

Table 2.

Causes of death among the study cohort.

| Cause | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sepsis | 6 (11.3) |

| Pneumonia | 6 (11.3) |

| Malignancy | 5 (9.4) |

| Cardiac arrest | 4 (7.5) |

| Renal failure | 3 (5.7) |

| ARDS | 3 (5.7) |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (5.7) |

| Stroke | 2 (3.8) |

| Multiorgan dysfunction | 1 (1.9) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (1.9) |

| Arrythmia | 1 (1.9) |

| RTA | 1 (1.9) |

| Homicide | 1 (1.9) |

| Unknown | 16 (30.2) |

ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; RTA: road traffic accident.

The expected mortality of Indian population of similar age and gender profile was 3.7%, giving SMR of 5.5 (95% CI: 4.2 – 6.9). SMR for different age quintiles were: aged 50 – 59 years group (SMR: 3.9, 95% CI: 0.8 – 10.8), aged 60 – 69 years group (SMR: 6.6, 95% CI: 3.7 – 10.4), aged 70 – 79 years group (SMR: 2.2, 95% CI: 1.2 – 3.6) and aged over 80 years group (SMR: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.3 – 2.7). The SMR in males and females were 5.7 (95% CI: 3.9 – 6.9) and 5.3 (95% CI: 3.6 – 7.4), respectively. The overall mortality of our cohort and SMR by age and gender are represented in Fig. 3, Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

Mortality based on age and gender.

Fig. 4.

Standard mortality rates based on age and gender.

Discussion

Mortality following hip fractures in the elderly is reported to be very high, but few studies have assessed the mortality in the elderly and the general population in India. In this study of consecutive series of elderly Indian hip fractures, we observed the 1-year mortality rate of 19.0% for hip fracture, with higher mortality in older patients. We also found that patients with hip fractures had about 5 times higher mortality rates than the general population of similar age and gender, with the highest excess mortality rate in patients of the 7th decade (60 – 69 years).

The study has some limitations. Long-term mortality could not be assessed in the present study because of only 1-year follow-up. The excess mortality of hip fracture may be lesser in longer follow-up. Although data of the presence/absence of mortality could be easily obtained, many patients dying at home or details about causes of death were unavailable. The present study also cannot determine whether the excess mortality is attributable to hip fractures alone. Several patients with hip fractures had multiple diseases at the same time which may make them more prone to fractures, and control populations with similar disease were not used in this study. However, the purpose of the study was only to compare the hip fracture mortality with mortality of the general population, and similar methods have previously been employed.8, 9, 10 Finally, the data in the present study were collected from a single tertiary hospital located in a metropolitan city, and the mortality rates in other hospitals may be considerably different. Also, state-wise data on age and gender specific mortality of the population was unavailable to be used as controls, and hence the data in our hospital were compared with that of the national population.

About two-fifths of the patients died within 1 year, which was similar to most of the studies reporting mortality of hip fractures.1,11, 12, 13, 14 Brozek et al.12 studied over 30,000 Austrian hip fracture patients aged above 50 years, and found unadjusted all-cause 1-year mortality amounted to 20%. Klop et al.11 reported the mortality rate ranged from 20% to 22% in a 10-year study (2000-2010) over 30,000 hip fractures in the United Kingdom. Our mortality rate was lower than that reported by Gupta et al.15 who observed a mortality of 28% in their study of 87 Indian patients. In another study including over 1000 Indian patients with hip fractures, the mortality rate at 3 months was 6.2% which was comparable to our study (6.8%).16 The mortality of Indian patients in our study cohort is comparable to that reported in other countries, highlighting the morbid nature of hip fractures globally (Table 3). While majority of the patients died during the first month in the present study, mortality continued to be high throughout the first year after hip fracture. Increasing age, multiple comorbidity, fall as mechanism of injury, use of home ambulators, and patients having no receiving surgery resulted in high mortality in our study, consistent with findings from other studies.4,13,17 Because of high mortality of hip fractures, understanding these risk factors is helpful in counselling patients and identifying high risk patients who might benefit from aggressive care.

Table 3.

Mortality of hip fractures in the elderly in various countries.

| Country | Type of study | Age group (year) | One-year mortality, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa18 | Prospective cohort | > 60 | 33.5 |

| Canada19 | Population based | > 60 | 30.8 |

| Australia20 | Retrospective | > 65 | 24.9 |

| Brazil21 | Retrospective | > 65 | 23.6 |

| China22 | Claims database | > 60 | 23.4 |

| United Kingdom11 | Population based | > 18 | 22 |

| United States23 | Prospective registry | > 60 | 21 |

| Austria12 | Claims database | > 50 | 20.2 |

| India (present study) | Prospective cohort | > 50 | 19.0 |

| Thailand24 | Retrospective | > 50 | 19.0 |

| Italy4 | Prospective cohort | > 65 | 16.6 |

| Korea25 | Claims database | > 50 | 16.55 |

In the present study, the excess mortality in hip fractures was about 5 times, which was comparable to other studies.5,36 Mortality was slightly higher in males in this study consistent with findings from other studies.37 As males have a higher bone mineral density than age-matched females, making them prone to weak bones/falls, fractures in males indirectly correlates with medical conditions.38 Although the actual mortality was higher in the elderly, the excess mortality was higher in relatively younger patients, and the highest excess mortality was seen in patients in the 7th decade (60 – 69 years). In a prospective study of hip fracture patients aged above 50 years, Forsen et al.26 reported the relative risk of dying within 1 year for patients below 75 years to be 4.2 and 3.3 for men and women, respectively, as well as the corresponding data for patients above 85 years were 3.1 and 1.6, respectively. Young patients have a higher mortality and a longer life remaining, suggesting that young patients lost more life years from hip fractures. Therefore, hip fractures should not be considered a high mortality event in the elderly and should be closely followed up and managed even in relatively young patients.5 In our study, the mortality of hip fractures in Indian population was higher than many other diseases considered having a high mortality, such as myocardial infarction and heart failure (Table 4). The hip fracture mortality was also higher than that of some common malignancies like breast, cervix, and prostate cancer. Similar to our findings, Lee et al.27 observed that a 5-year survival of hip fracture was comparable with that of breast and thyroid cancer, suggesting that hip fractures should not be overlooked.

Table 4.

Mortality of hip fractures compared with other diseases in Indian population.

| Diseases | One-year mortality, % |

|---|---|

| Lung Cancer26 | 82.5 |

| Stroke27 | 47.6 |

| Liver cirrhosis28 | 33.2 |

| COPD exacerbation29 | 32.4 |

| Hip fractures (present study) | 19.0 |

| Heart failure30 | 17.6 |

| Myocardial infarction31 | 15.5 |

| Oral Cancer32 | 12.0ⴕ |

| Prostate cancer33 | 8.0 |

| Cervical cancer34 | 7.5 |

| Breast cancer35 | 3.0 |

ⴕ2 year survival.

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Our study found that Indian patients sustaining hip fractures were about 5 times more likely to die than the general population. To our best knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the excess mortality observed in Indian hip fractures patients, and these results are useful in counselling patients (and/or their families) sustaining hip fractures. Although mortality rates increased with age, patients with hip fracture had the highest excess mortality rate at 7th decade (6 times the expected mortality rate), while their young and old counterparts had mortality rates 2 – 3 times higher than expected. Mortality in Indian hip fractures was even higher than that observed in Indian patients with myocardial infarction, breast cancer, and cervical cancer. Further research is required to understand how much of this excess mortality is directly attributed to hip fractures, and if this excess mortality can be minimized with any treatment measures.

Funding

Nil.

Ethical statement

The study involves human subjects and was approved by the institutional ethical board, and informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Declaration of competing interest

Jaiben George, Vijay Sharma, Kamran Farooque, Samarth Mittal, Vivek Trikha, and Rajesh Malhotra declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in study design. JG, VS, KF, SM, VT were involved in data collection. JG and VS were involved in data cleaning and analysis. JG, VS and RM wrote the manuscript. All authors read the manuscript and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Medical Association.

References

- 1.Maheshwari K., Planchard J., You J., et al. Early surgery confers 1-year mortality benefit in hip-fracture patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32:105–110. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhanwal D.K., Siwach R., Dixit V., et al. Incidence of hip fracture in Rohtak district, North India. Arch Osteoporosis. 2013;8:135. doi: 10.1007/s11657-013-0135-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commissioner O of the RG& C . Govt India; 2011. Census India.https://censusindia.gov.in/census.website/data/census-tables [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morri M., Ambrosi E., Chiari P., et al. One-year mortality after hip fracture surgery and prognostic factors: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leu T.H., Chang W.C., Lin J.C.F., et al. Incidence and excess mortality of hip fracture in young adults: a nationwide population-based cohort study. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2016;17:1–8. doi: 10.1186/S12891-016-1166-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asaria M., Mazumdar S., Chowdhury S., et al. Socioeconomic inequality in life expectancy in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4 doi: 10.1136/BMJGH-2019-001445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations World Population Prospects - Population Division - United Nations. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Mortality/ n.d.

- 8.Bliuc D., Nguyen N.D., Milch V.E., et al. Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA, J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301:513–521. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yong E.L., Ganesan G., Kramer M.S., et al. Risk factors and trends associated with mortality among adults with hip fracture in Singapore. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C.B., Lin C.F.J., Liang W.M., et al. Excess mortality after hip fracture among the elderly in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Bone. 2013;56:147–153. doi: 10.1016/J.BONE.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klop C., Welsing P.M.J.J., Cooper C., et al. Mortality in British hip fracture patients, 2000-2010: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Bone. 2014;66:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brozek W., Reichardt B., Kimberger O., et al. Mortality after hip fracture in Austria 2008-2011. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014;95:257–266. doi: 10.1007/s00223-014-9889-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu F., Jiang C., Shen J., et al. Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2012;43:676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhibar D., Gogate Y., Aggarwal S., et al. Predictors and outcome of fragility hip fracture: a prospective study from North India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2019;23:282. doi: 10.4103/ijem.ijem_648_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta R., Vashist D., Gupta P., et al. Predictors of 1-year mortality after hip fracture surgery in patients with age 50 years and above: an Indian experience. Indian J Orthop. 2021 552 2021;55:395–401. doi: 10.1007/S43465-021-00396-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dash S.K., Panigrahi R., Palo N., et al. Fragility hip fractures in elderly patients in bhubaneswar, India (2012-2014): a prospective multicenter study of 1031 elderly patients. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2015;6:11–15. doi: 10.1177/2151458514555570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang W., Lv H., Feng C., et al. Preventable risk factors of mortality after hip fracture surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;52:320–328. doi: 10.1016/J.IJSU.2018.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paruk F., Matthews G., Gregson C.L., et al. Hip fractures in South Africa: mortality outcomes over 12 months post-fracture. Arch Osteoporosis. 2020;15:76. doi: 10.1007/s11657-020-00741-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang H.X., Majumdar S.R., Dick D.A., et al. Development and initial validation of a risk score for predicting in-hospital and 1-year mortality in patients with hip fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:494–500. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell R., Harvey L., Brodaty H., et al. One-year mortality after hip fracture in older individuals: the effects of delirium and dementia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;72:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guerra M.T.E., Viana R.D., Feil L., et al. One-year mortality of elderly patients with hip fracture surgically treated at a hospital in Southern Brazil. Rev Bras Ortop. 2017;52:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S., Sun T., Liu Z. Excess mortality of 1 year in elderly hip fracture patients compared with the general population in Beijing, China. Arch Osteoporosis. 2016;11:35. doi: 10.1007/s11657-016-0289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okike K., Chan P.H., Paxton E.W. Effect of surgeon and hospital volume on morbidity and mortality after hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:1547–1553. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.01133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daraphongsataporn N., Saloa S., Sriruanthong K., et al. One-year mortality rate after fragility hip fractures and associated risk in Nan, Thailand. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2020;6:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang H.Y., Yang K., Kim Y.N., et al. Incidence and mortality of hip fracture among the elderly population in South Korea: a population-based study using the national health insurance claims data. BMC Publ Health. 2010;10:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forsén L., Søgaard A.J., Meyer H.E., et al. Survival after hip fracture: short- and long-term excess mortality according to age and gender. Osteoporos Int. 1999;10:73–78. doi: 10.1007/s001980050197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee Y.K., Lee Y.J., Ha Y.C., et al. Five-year relative survival of patients with osteoporotic hip fracture. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:97–100. doi: 10.1210/JC.2013-2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain P., Shasthry S.M., Choudhury A.K., et al. Alcohol associated liver cirrhotics have higher mortality after index hospitalization: long-term data of 5,138 patients. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021;27:175. doi: 10.3350/CMH.2020.0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koul P.A., Dar H.A., Jan R.A., et al. Two-year mortality in survivors of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a North Indian study. Lung India. 2017;34:511. doi: 10.4103/LUNGINDIA.LUNGINDIA_41_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chopra V.K., Mittal S., Bansal M., et al. Clinical profile and one-year survival of patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the largest report from India. Indian Heart J. 2019;71:242–248. doi: 10.1016/J.IHJ.2019.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexander T., Mullasari A.S., Joseph G., et al. A system of care for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in India: the Tamil nadu–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction program. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:498–505. doi: 10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2016.5977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohia Bhatnagar S., Singh S., Prashar M., et al. Survival trends in oral cavity cancer patients treated with surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy in a tertiary center of Northern India: where do we stand compared to the developed world? SRM J Res Dent Sci. 2019;10:26. doi: 10.4103/SRMJRDS.SRMJRDS_58_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balasubramaniam G., Talole S., Mahantshetty U., et al. Prostate cancer: a hospital-based survival study from Mumbai, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2013;14:2595–2598. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.4.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balasubramaniam G., Gaidhani R.H., Khan A., et al. Survival rate of cervical cancer from a study conducted in India. Indian J Med Sci. 2021;73:203–211. doi: 10.25259/IJMS_140_2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ganesh B., Talole S.D., Dikshit R., et al. Estimation of survival rates of breast cancer patients - an hospital-based study from Mumbai. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2008;9:53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanis J.A., Oden A., Johnell O., et al. The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone. 2003;32:468–473. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(03)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haentjens P., Magaziner J., Colón-Emeric C.S., et al. Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:380–390. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nieves J.W., Formica C., Ruffing J., et al. Males have larger skeletal size and bone mass than females, despite comparable body size. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:529–535. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]