Abstract

Background:

Trans people in prison experience disproportionate rates of harm, including negative mental health outcomes, and thus require special protections. Instead, corrections policies have historically further marginalised them. This critical policy review aimed to compare corrections policies for trans people in Australia and New Zealand with human rights standards and consider their mental health impact.

Methods:

Online searches were conducted on corrections websites for each state/territory in Australia and New Zealand. Drawing on the Nelson Mandela Rules and Yogyakarta Principles, 19 corrections policies relevant to placement, naming, appearance and gender-affirming healthcare for trans people were reviewed. The potential mental health impact of these policies on incarcerated trans people was discussed using the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience framework.

Results:

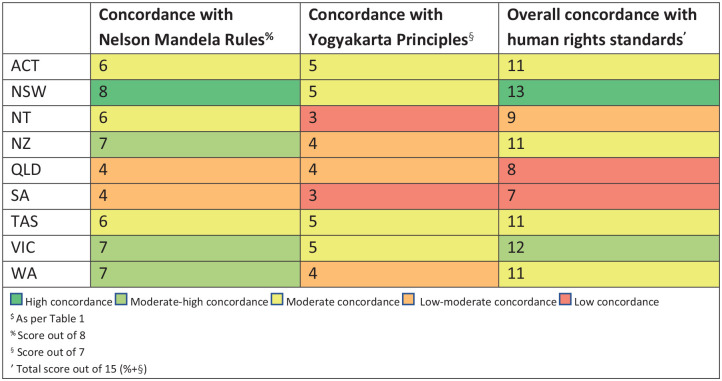

Australian and New Zealand corrections policies have become more concordant with human rights standards in the past 5 years. However, gender-related discrimination and human rights violations were present in corrections policies of all jurisdictions. New South Wales and Victorian policies had the highest concordance with human rights standards, while Queensland and South Australian policies had the lowest.

Conclusion:

Policies that contribute to discrimination and minority stress may increase risk of mental health problems and suicide for incarcerated trans people. Mental health professionals working in prisons need to be aware of these risks to provide safe and accessible mental healthcare for trans people. Collaborative policy development with trans people is essential to protect the safety and rights of incarcerated trans people and consider models beyond the gender binary on which correctional systems have been founded.

Keywords: Trans person, non-binary person, prison, corrections policy, mental health, human rights, Australia, New Zealand

Introduction

Correctional systems are traditionally sex-segregated and thus do not easily accommodate trans people, whose gender differs from that assigned at birth. Trans is an umbrella term including people who are trans men, trans women, non-binary, genderfluid, and, within the Australian and New Zealand (NZ) context, Sistergirl, Brotherboy, takatāpui, irawhiti, fa’afafine, fakaleiti and akava’ine (Kerry, 2014; Schmidt, 2011; Tan et al., 2019a). Trans people in prison are more vulnerable than the general prison population to violence, harassment and the negative physical and mental health impacts of stigma, discrimination and lack of access to gender-affirming care (Hughto et al., 2022; Phillips et al., 2020; Rogers et al., 2023; Utnage, 2023). They require special considerations to protect their health and safety, as well as to prevent ‘erasure of their gender’ (Brömdal et al., 2023: 43) and identity (Brömdal et al., 2019a). Sex segregation of prisons results in a range of concerns for trans people and prison administrators, including housing, provision of adequate healthcare and availability of clothing, personal care, cosmetic and other grooming items for diverse gender expressions (Sumner and Sexton, 2016). Thus, specific policies are required to address these concerns.

Although correctional services are charged primarily with maintaining community safety and security of their facilities, they also hold a duty of care towards the people in their custody (Blight, 2000; Lynch and Bartels, 2017). Policy development is influenced not only by the bureaucracy of the institution, but also by societal and cultural attitudes, politics, legal cases and stakeholder interests, e.g. trans community groups (Whiteford, 2001). Conservative media narratives claiming trans people are dangerous (Bindel, 2023; Reinl, 2023; Rutherford, 2023), affect societal attitudes and stigmatise trans people (Hughto et al., 2021; McInroy and Craig, 2015). In NZ, there has been a significant increase in the volume and harmful tone of hatred towards trans people in the past year (Hattotuwa et al., 2023). The rise in violent and genocidal ideas about trans people in online forums corresponds with a British anti-transgender activist Australasian tour in March 2023, and with increased local and international disinformation activity using a false narrative that trans people are a threat to cisgender women and children. This perception of heightened risk has historically dominated correctional policies which have adopted a ‘genitalia-based’ approach to housing trans people over an ‘identity-based’ approach (Jamel, 2017: 162). Policies with genitalia-based placement have been influenced by concerns about perceived sexual risks towards cisgender women in prison, such as sexual assault and pregnancy (Mann, 2006; Stohr, 2015; Sumner and Jenness, 2014). However, research has shown trans women placed in men’s prisons experience disproportionate rates of sexual violence (Jenness et al., 2007). They are also more likely to be misnamed and misgendered (Jenness, 2021), and unable to access gender-affirming healthcare (Brown and McDuffie, 2009), appropriate clothing, personal care and grooming items to maintain their gender expression (Brömdal et al., 2023). It appears the duty of care correctional services hold towards trans people has been deprioritised over others in the prison system.

Australia and NZ are signatories to the United Nations (UN) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (UN, 1966, 1984), which protect all prisoners, including trans people, from discrimination. Anti-discrimination legislation in Australia explicitly prohibits discrimination based on gender identity (Sex Discrimination Act 1984 [Cwlth] s. 5B). In NZ, the Human Rights Act 1993 s. 21 prohibits discrimination based on sex, which is considered to include protection for trans people based on gender identity (Gwyn, 2006). Based on recommendations from the NZ Human Rights Commission (NZHRC) and Royal Commission of Inquiry into the 2019 Christchurch terrorist attack, the current NZ government have agreed in principle to improve protections against hatred and discrimination, including an amendment of the Human Rights Act prohibiting discrimination based on gender identity and gender expression (Faafoi, 2021; New Zealand Human Rights Commission [NZHRC], 2020). The matter is currently being reviewed by the NZ Law Commission (Geiringer, 2023). In addition, human rights for trans people in prison are detailed in the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules), the Yogyakarta Principles and the Yogyakarta Principles Plus 10 (International Commission of Jurists [ICJ], 2007, 2017; UN, 2015). These rights include safety, respect, non-discrimination and dignified treatment in accordance with one’s gender identity. Thus, breaches of anti-discrimination legislation or human rights obligations may occur where policies do not adequately protect the rights of trans people in prison (Blight, 2000; Lynch and Bartels, 2017).

Mental health of trans people

Gender diversity is common in many cultures and is not pathological (Coleman et al., 2022). However, some trans people experience gender dysphoria or distress secondary to the discrepancy between their gender identity and gender assigned at birth (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). Research suggests gender affirmation can reduce negative mental health outcomes and gender dysphoria (Russell et al., 2018; Swan et al., 2023; Tordoff et al., 2022; Turban et al., 2022; White Hughto and Reisner, 2016).

Parallel to this, trans people are disproportionately affected by mental illness, addiction, self-harm and suicide as a result of minority stress (Coleman et al., 2022; Franks et al., 2022; Reisner et al., 2016a; Strauss et al., 2021a; Valentine and Shipherd, 2018). Minority stress refers to the impact of stigma, prejudice and discrimination towards people in marginalised groups (Meyer, 2003). Minority stress is compounded by intersectionality for those with multiple marginalised identities, such as indigenous trans people or trans women (Clark et al., 2023; Tan et al., 2019b; Wesp et al., 2019). Protective factors including social support, connectedness and pride have been shown to mediate the negative effects of minority stress and promote resilience (Du Plessis et al., 2023; Testa et al., 2015).

Gender Minority Stress and Resilience (GMSR) theory describes internal and external stressors that negatively impact trans people’s mental health and protective resilience factors (Testa et al., 2015). At a structural level, policy can directly affect distal stress factors such as gender-related discrimination and non-affirmation of gender identity, and increase the risk of interpersonal distal stress factors (gender-related rejection and victimisation) (Tan et al., 2021). These experiences may lead to the development of proximal stress factors (internalised transphobia, negative expectations of further abuse and gender identity concealment). Stigma and negative expectations are also barriers to trans people accessing mental healthcare (Ellis et al., 2015; Strauss et al., 2021b). The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) recognise the negative mental health impact of discrimination and marginalisation, and therefore the importance of providing culturally competent mental healthcare for trans people (RANZCP, 2021).

Trans people in prisons

Estimates of the prevalence of trans people in prisons are limited by data collection on legal binary gender only, as well as stigma and safety risks that discourage self-identification (Brömdal et al., 2023, 2019b). However, what few studies are available suggest trans people, particularly trans women of colour and indigenous trans women, are incarcerated at disproportionately high rates (Clark et al., 2023; Sanders et al., 2023). In the United States, trans and gender-diverse people had a lifetime incarceration prevalence of 16%, compared with 2.7% of the general population (Grant et al., 2011). The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW, 2015) reported six trans people entered prison in 2015, out of a total of 1011 prison entrants. Brömdal et al. (2023) found 68 trans persons were incarcerated in Queensland between 2014 and 2020. More recent Australian prison population statistics have not included the number of incarcerated trans people (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2023; AIHW, 2019]. In NZ, 35 trans people were reportedly held in custody in 2020 (Leota, 2020). Little is known about incarceration rates of gender minority subgroups, such as non-binary people (Jacobsen et al., 2023). Research suggests the higher rate of incarceration of trans people is linked to abuse and rejection, housing instability, substance use problems, problems accessing healthcare, survival theft, survival sex work and bias within the police and justice systems (Clark et al., 2023; Sanders et al., 2023). The decriminalisation of sex work in NZ may have resulted in lower rates of incarceration of trans women in NZ (Gilmour, 2020).

The predominantly cisnormative gender binary system within prisons leads to amplification of minority stress for trans people (Du Plessis et al., 2023; Rodgers et al., 2017; Van Hout and Crowley, 2021). Trans people have been found to experience higher rates of harassment, physical abuse and sexual violence than the general prison population from other persons in prison and custodial staff (Brooke et al., 2022; Hughto et al., 2022; Mitchell et al., 2022; Van Hout et al., 2020). Among trans populations in prison, trans people of colour, indigenous trans people, trans women and non-binary people have been found to have the highest rates of victimisation (Grant et al., 2011; Hughto et al., 2022; Lydon et al., 2015). However, there have been only a few studies looking at the experience of Indigenous and Pasifika trans people in Australian and NZ prisons (Clark et al., 2023; Hansen-Reid, 2011; Sanders et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2017), and, to our knowledge, none including non-binary people. Research has found issues with access to safe gender-affirming healthcare for trans people in Australian and NZ prisons (Lynch and Bartels, 2017; NZHRC, 2020). Misgendering, misnaming, restricted access to clothing or grooming items and barriers to continuing or accessing gender-affirming healthcare in prison can increase the risk of gender dysphoria, depression, self-harm and suicide (Coleman et al., 2022; Grant et al., 2011). Physical and mental healthcare provision for trans people in prisons may be affected by structural factors, e.g. lack of clinician training and restrictive policies, as well as biases and limited cultural competence by healthcare providers (Clark et al., 2017). Trans people face these issues in addition to the stressors faced by all incarcerated people, with higher rates of substance use disorders, mental illness, self-harm, suicidal ideation and inadequate availability of mental healthcare in prisons (Browne et al., 2022; Fazel et al., 2016; Monasterio et al., 2020).

Housing is a particularly complex issue for trans people and prison administrators. Studies have shown a genitalia-based approach is followed in prisons in the United States, United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada and Australia, discriminating against trans people who have not undergone phalloplasty/vaginoplasty (Hughto et al., 2022; Rodgers et al., 2017; Van Hout et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2017). In NZ, initial placement has been based on birth certificate, which disproportionately affects trans people from low income backgrounds due to the prohibitive barriers and costs in seeking legal gender affirmation (Cassaidy and Lim, 2016; Swan et al., 2023). However, the Births, Deaths, Marriages, and Relationships Registration Act 2021 (NZ) which came into effect on 15 June 2023, enables amendment of sex on birth certificates based on self-identification. Although identity-based placement is more consistent with anti-discrimination legislation and a human rights approach, qualitative research of trans people who have been incarcerated shows diverse views on housing (Brömdal et al., 2019b). For example, trans men may prefer to be in a women’s prison due to the increased risk of harassment and abuse they face in men’s prisons (Mann, 2006). Alternatively, some trans women have expressed a preference to be housed in a men’s prison due to the perceived risk of violence from other women, or to seek protective, romantic or sexual relationships with men (Brömdal et al., 2023; Jenness and Fenstermaker, 2014; Wilson et al., 2017). Further complexities arise regarding the placement of non-binary people within the strictly gender binary prison system (Van Hout and Crowley, 2021).

Trans people are often segregated or isolated from others in prison, within a narrative and ethos for optimising safety and security (Phillips et al., 2020; Van Hout et al., 2020). However, placement in protective custody or administrative segregation may limit access to opportunities such as work, education, rehabilitation, socialisation and exercise (Jamel, 2017; Mann, 2006; Sumner and Jenness, 2014). Isolation may also lead to trauma, psychological distress, self-harm and suicide (McCauley et al., 2018; Phillips et al., 2020). Another option is the creation of correctional facilities solely for trans people. Maycock (2020) found trans people had differing views on a prison with a transgender wing in Scotland, with benefits for non-binary people, sense of community and support identified as positive factors. However, some trans people said they may not necessarily get along with other trans people and did not like to be treated differently based on their trans status (Maycock, 2020). Furthermore, building a separate facility is costly and resource constraints may limit availability of services and programmes for trans people incarcerated in different settings. The heterogeneity of views among the trans community highlights the importance of individual assessment considering the person’s self-defined gender identity, safety and preference (Brömdal et al., 2019a; Sevelius and Jenness, 2017).

Policy reviews

Policy change can provide the foundation for whole-incarceration-setting approaches to improve conditions for trans people in prison (Brömdal et al., 2019a; Murphy et al., 2023). Previous policy reviews in Australia and NZ have highlighted issues in relation to placement, name and pronoun use and access to gender-affirming healthcare (Blight, 2000; Cassaidy and Lim, 2016; Lynch and Bartels, 2017; Rodgers et al., 2017). This policy review will critically appraise current corrections policies regarding the placement, treatment and access to gender-affirming healthcare for trans people in Australian and NZ prisons, with comparison to international human rights standards. It will also discuss how the policies are likely to impact GMSR factors and the mental health of trans people in prison.

Aims

To carry out a critical review of the current corrections policies for the management of trans people in Australian and NZ prisons and their concordance with international human rights standards; and

To discuss the potential mental health implications of current corrections policies for trans people in Australian and NZ prisons utilising the GMSR model as a critical framework.

Method

A manual systematic search was done on the public adult corrections service website of each Australian state/territory and NZ (nine services in total) for publicly available corrections policies or directives (henceforth referred to as policies) including the terms trans, transgender, non-binary, gender, placement, name, clothing, grooming, health, healthcare and treatment. An additional text search was done within any policies that could contain relevant information, e.g. policies on reception procedures. Requests were also sent via email to corrections services of each jurisdiction for any additional or updated policies regarding management and healthcare for trans people in prison. Where corrections services identified that contracted providers were responsible for healthcare, e.g. Justice Health in Victoria and New South Wales (NSW), requests were also sent to these services for any relevant policies. Identified policies were reviewed and included if they contained content relevant to the following aspects of care:

Process and decision-making criteria for placement of people in prison who identify as trans;

Use of chosen names and pronouns in prison;

Access to gender-affirming clothing, grooming and personal care items in prison;

Access to gender-affirming healthcare, including hormone therapy or gender-affirming surgery, in prison.

For each jurisdiction, the relevant policy content was compared against international standards for the treatment of persons in prison (the Nelson Mandela Rules) and gender-diverse persons (the Yogyakarta Principles) (ICJ, 2007, 2017; UN, 2015). A similar style of analysis to the work of Ellery Gray et al. (2010) was carried out, in which legislation was compared against international human rights instruments with a focus on several different issues. Each jurisdiction received a score out of 15 based on concordance with relevant human rights standards (summarised in Table 1 and explained below), with higher scores indicating a greater degree of concordance. The policy search, review and scoring were done by L.G.D.; then, the policies were independently reviewed and scored again by S.C.P. and A.B. Any discrepancies in scoring were discussed between the reviewers and an agreement was reached.

Table 1.

Summary of international human rights standards for trans people in prison.

| Aspect of care | Nelson Mandela Rules a | Yogyakarta Principles b |

|---|---|---|

| Placement | 1. Placement in men’s/women’s prison should be based as much as possible on self-determined gender identity to avoid discrimination. 2. Prison administrators need to protect the safety of all people in prison, including trans people. |

1. Trans people should be involved in decisions regarding their placement. 2. Placement decisions should be appropriate to the person’s self-determined gender identity and should minimise risk of violence, abuse, harm and marginalisation on the basis of gender identity. 3. People in prisons should have access to safe and dignified sanitation facilities. 4. Protective measures for trans people should not involve more restriction of rights than the general prison population. |

| Name/pronoun use | 3. Trans people should be allowed to use their chosen name and pronouns as they would in the community in daily interactions, even without a legal change of name/sex. 4. Self-perceived gender, name and pronouns should be entered into file management system on admission. |

5. People in prisons should be able to express their identity with their own choice of name and pronouns. |

| Clothing/grooming items | 5. Trans people should be allowed to either wear their own clothing or be provided with suitable clothing appropriate to their self-determined gender identity as they would in the community. 6. Trans people should be able to access appropriate grooming facilities to maintain appearance in keeping with their self-respect as they would in the community. |

6. Trans people should be able to express and affirm their identity through dress and bodily characteristics, without discrimination on the basis of gender identity. |

| Gender-affirming healthcare | 7. Trans people should have access to the same healthcare services as in the community including hormone, gender-affirming surgery or other gender-affirming therapies. 8. Trans people should be able to continue any hormone or other therapies they were using prior to incarceration. |

7. People in prisons have the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, which includes access to gender-affirming treatment when needed. |

Based on Rules 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 18, 19, 24, 115.

Based on Principles 3, 9, 17, 19, 35.

The findings were critically reviewed using the GMSR model as a framework to discuss the potential impact of the policies on the mental health of trans people in prison (Testa et al., 2015). A critical review using the GMSR model was considered the most suitable theoretical framework to analyse the mental health implications of these policies since they are not academic papers that can be subject to scientifically informed critical appraisal.

Human rights standards

The Nelson Mandela Rules describe imprisonment as a significant hardship due to loss of liberty, stating prison systems should avoid ‘aggravating the suffering inherent in such a situation’ (UN, 2015: 3). They emphasise the right to treatment with respect, protection from inhuman or degrading treatment, including acts that cause either physical pain or ‘mental suffering’ (United Nations Human Rights Committee, 1992), and non-discrimination based on sex. Therefore, to prevent discrimination and additional suffering, trans people have a right to be placed in a prison consistent with their gender identity. However, the Nelson Mandela Rules maintain separate detention of men and women with no provision for non-binary people (UN, 2015).

The Nelson Mandela Rules state prison systems should aim to limit differences from community life that would lessen respect and dignity (UN, 2015). People in prison should be able to ‘maintain a good appearance’ and wear clothing that is not degrading or humiliating (UN, 2015: 6). Untried people should be permitted to wear their own clothing. Each person’s ‘self-perceived gender’ (UN, 2015: 4) should be recorded in the file management system. Therefore, as in the community, trans people should be addressed using their chosen name and pronouns and have access to items required to maintain expression of their gender identity in prison.

Similarly, equivalent healthcare services should be provided in prison as are available in the community (UN, 2015), and services should enable continuity of care when a person is taken into custody. Trans people should thus be able to access and continue gender-affirming treatment, noting some treatments such as gender-affirming surgery are not fully funded by Medicare in Australia (Rosenberg et al., 2021). Although gender-affirming healthcare, including surgery, is publicly funded in NZ, accessibility remains a significant issue (Oliphant et al., 2018; Te Whatu Ora, 2022).

The Yogyakarta Principles affirm self-defined gender identity as ‘one of the most basic aspects’ of a person’s ‘self-determination, dignity and freedom’ (ICJ, 2007: 11). They state hormonal or surgical treatment should not be required for a person’s gender identity to be legally recognised. Correctional facilities should have policies regarding placement and treatment of trans people which ‘reflect the needs and rights of persons of all . . . gender identities, gender expressions, and sex characteristics’ (ICJ, 2017: 18). Consistent with the ‘right to treatment with humanity while in detention’ (ICJ, 2007: 16), trans people have the right to placement according to their gender identity to maintain their dignity and prevent further marginalisation, violence and abuse. However, the Yogyakarta Principles also maintain trans people should be involved in their placement decisions, allowing for personal preference of placement due to safety or other concerns. Measures to protect a person’s safety, e.g. protective custody, should be no more restrictive than experienced by the general prison population. Prisons must provide safe and dignified access to sanitation facilities without discrimination based on gender identity or expression. The right to freedom of opinion and expression includes the right to express ‘identity or personhood’ through choice of name, clothing or any other means (ICJ, 2007: 24). In addition, trans people should have adequate access to healthcare, including gender-affirming treatment when desired, based on the right to the ‘highest attainable standard of health’ (ICJ, 2007: 22).

Results

An online search conducted in June 2022 and repeated in November 2022 and February 2023 found 33 publicly available corrections policies on the websites of the Australian Capital Territory Corrective Services (ACTCS), Corrective Services New South Wales (CSNSW), NZ Department of Corrections (henceforth Ara Poutama Aotearoa), Queensland Corrective Services (QCS), Corrections Victoria (CV) and Western Australia Corrective Services (WACS), of which 14 were included as they were relevant to the management of trans people (ACTCS, 2022a, 2022b; Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2016a, 2016b, 2020; CSNSW, 2017, 2021, 2022; CV, 2021, 2022; QCS, 2022, 2023a, 2023b; WACS, 2022). The policies on the ACTCS website also referenced a specific policy for the management of trans people in prison which was not available online (ACTCS, 2022a, 2022b). In response to email requests sent in August 2022, ACTCS, Northern Territory Correctional Services (NTCS) and Tasmania Prison Service (TPS) provided their policies specific to the management of trans people (ACTCS, 2018; NTCS, 2021; TPS, 2018). South Australia Department of Correctional Services (SADCS) did not have any available policies online and responded to an email in August 2022 that they were near finalising a new policy. However, there was no response to further email and phone requests in August 2022, November 2022, January 2023 and February 2023 for a copy of the new policy. An archival version of the SA policy was reviewed instead (SADCS, 2018]. In addition, we received another Ara Poutama policy regarding the provision of gender-affirming healthcare through the peer review process (Ara Poutama Aotearoa Health Services, 2021). We did not receive a response from any organisations contracted to provide health services in prisons. In total, 19 policies were included in the review.

Table 2 summarises the reviewed policies regarding placement, name and pronoun use, access to gender-affirming clothing and grooming items and access to gender-affirming healthcare. Table 3 shows each jurisdiction’s scoring based on concordance with human rights standards, and the overall concordance scores are in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Summary of corrections policies for management of trans people in prison.

| Placement | Name/pronoun use | Clothing/grooming items | Gender-affirming healthcare | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT | • Trans people have the right to be placed in accommodation of their self-identified gender unless risk assessment overrides. • Trans person’s preference is taken into account in placement decisions. • Management in least restrictive settings to maintain safety and security of all. |

• Staff must ask people on reception to prison what their preferred pronouns are, including they/them. • Trans person’s chosen name and pronouns are to be used. • Self-identified gender, name and pronouns are to be recorded in electronic system. |

• Trans people will be provided with clothing, underwear and other items to align their appearance with their gender identity. • Trans people may purchase non-standard items (e.g., hair removal cream) to align their appearance with their gender identity unless safety concerns override. |

Not mentioned. |

| NSW | • ‘Recognised’ trans people with identification will be automatically placed in prison of recognised sex.

a

• People who do not identify as either male or female will be sent initially to the Metropolitan Remand and Reception Centre (a men’s prison) for assessment and determination of placement. • Trans people have the right to be placed in accommodation of their self-identified gender unless security or safety concerns override. • Trans people will have the same classification and placement options, and the same access to services and programmes as all others in the prison where they are housed. |

• Trans person’s chosen name and pronouns are to be used. • Self-identified gender and transgender status are to be recorded in electronic system. |

• Trans people have the right to dress in clothing appropriate to their gender identity. • Trans people will be provided with clothing and underwear appropriate to their gender identity, or to their preference if they do not identify as either male or female. • Trans people are able to purchase the same cosmetic and personal care items as all others of their self-identified gender. |

• Trans people can continue hormone therapy from the community and will receive appropriate management by prison health services. • Trans people can commence hormone therapy in custody with a collaborative treatment plan with health, mental health and offender services staff. • Trans people may apply to have elective gender-affirming surgery or other therapies specific to their needs at their own expense. |

| NT | • Trans people will be accommodated according to their self-identified gender if there are no identified concerns. • Special considerations to ensure the trans person’s safety may include separation from others, provision of single accommodation, separate toilet and shower access. • It is noted the specific needs of individuals with a gender identity that is different from male or female may not be able to be accommodated within custodial facilities that comprise of male and female sections. |

• Trans person’s chosen name and pronouns are to be used. • Self-identified gender, name and pronouns are to be recorded in electronic system, which has four sex and gender identity options (male, female, non-binary, unidentified). |

• Trans people will have access to underwear appropriate to their preference. • Requests can be made to the General Manager for variations (e.g., make-up, wigs). |

• Trans people can request gender-affirming treatment including hormone therapy and surgery. • Requests will be considered collaboratively with health services and General Manager. • Approval of requests for surgery requires determination of ‘essential medical necessity’ and includes consideration of length of sentence and ‘good order’ of the institution. |

| NZ | • Initial placement is based on birth certificate. • Trans people can request a review of placement unless they are on remand for a serious sexual offence or have been sentenced for serious sexual offending within the past 7 years. • If a person produces a birth certificate that records their sex as indeterminate or does not record a sex, a placement review must be undertaken regardless of their offending history. • Trans people must be placed in single cells. • If in-cell showers are not available, measures will be considered to protect the trans person’s privacy while showering. • Measures to protect the trans person should be considered against their restrictive impact. |

• Trans person’s chosen name and pronouns are to be used. • Preferred name and pronouns (he/him, she/her, they/them) are to be entered with ‘transgender alert’ on electronic system. |

• Trans people must be able to dress according to their gender identity. • Trans people must be provided with access to items required to maintain the appearance of their gender identity (e.g. chest binders, prostheses), unless safety concerns override. • Authorised property includes one disposable razor, except for people on remand, in high security or youth units. Application can be made for other grooming items (e.g., make-up). • Sanitary items are listed for ‘female prisoners only’. |

• Culturally appropriate gender-affirming healthcare based on self-determination and informed consent is available utilising the same referral pathways and treatment options as are available in the community. |

| QLD | • Trans people who have completed legal and surgical gender transition will be placed in a prison of their gender identity. • Placement of trans people who have not completed gender-affirming surgery will be made on a case-by-case basis, including consideration of risks to self and others, previous social and medical gender affirmation, views of their treating medical practitioner and their own preference. • Trans people should be provided access to sanitation facilities that maintain their privacy and dignity. • Trans people should not be placed under restrictive measures unless required to manage risk to self or others. |

• Trans person’s chosen name and pronoun consistent with gender identity are to be used. | • Access to property, clothing and other requests for functional items will be discussed at a multidisciplinary case conference held within 7 days of initial reception. | • Medical treatment will be discussed at a multidisciplinary case conference held within 7 days of initial reception. |

| SA | • Trans people will be assessed on a case-by-case basis, with placement decisions considering the privacy and safety of the trans person, safety of others, security of the prison, views of medical practitioners and their own views. • Consideration will be given to appropriate sanitation facilities that maintain privacy. |

• Trans person’s chosen name and pronouns are to be used. • Self-identified gender is to be recorded in the person’s records. • Additional information may be attached to relevant documents if identifiers do not align with an individual’s gender identity or non-specific sex (i.e. if the individual doesn’t identify as male or female). |

• Trans people will have access to appropriate underwear on request. • Clothing will be in accordance with the prison in which the person is placed. • Cosmetics will not be made available in men’s prisons. In women’s prisons, trans people may have access to cosmetics in accordance with the prison dress code and their individual management regime. |

• Trans people will be referred to prison health services on request. • Consideration of hormone therapy is the responsibility of prison health services. • Gender-affirming surgery will be considered on a case-by-case basis for those with a non-parole period of at least 5 years. Surgery must be deemed an ‘essential medical necessity’, and consideration will also be given to the ‘good order’ of the institution, resource availability and the person’s individual programme. |

| TAS | • Trans people have the right to be placed in accommodation appropriate to their self-identified gender unless safety, security or the ‘good order’ of the prison is thought to be compromised. • Placement decisions will consider the trans person’s preference, extent of social gender affirmation, views of medical practitioners and safety and security of the prison. • Trans people will be accommodated in single cells with access to separate sanitation facilities until a decision about ongoing placement is made. • Trans people must be placed in administrative segregation if they are deemed to require protection from the general prison population until a decision about ongoing placement is made. |

• Trans person’s chosen name and pronouns are to be used. • Chosen name, identified gender and ‘gender alert’ are to be recorded on electronic system. |

• Trans people will be issued with clothing appropriate to the facility in which they are placed. • Trans people will have access to underwear appropriate to their gender identity. • Trans people are able to purchase the same personal care and cosmetic items as others in the same facility. |

• Trans people can continue hormone or gender-affirming surgery commenced in the community at their own expense with support from prison health services. • Trans people may be assessed by prison health services if they request to commence hormone therapy or gender-affirming surgery in custody. If recommended and available, b treatment can be accessed at their own expense. |

| VIC | • Trans people should be placed in a prison according to their gender identity, noting men’s and women’s prison systems currently remain the only placement options for people who identify as trans, gender diverse or intersex. • Initial placement generally depends on documentation from courts/police and must be reviewed within 3 days, with consideration of the person’s preference, lived experience, medical advice, length of sentence, risk to self or others and risk to security of the prison. • Prior to placement review, trans people will be kept separate from others and accommodated in a single cell. • Segregated trans people will be managed under the least restrictive conditions to manage the risk. • Trans people will have access to sanitation facilities that maximise their safety, dignity and privacy. |

• Trans person’s chosen name and pronouns are to be used. • A person who identifies as non-binary should be referred to by their name and the pronouns that they use (which may be ‘they’ or some other term, or they might prefer no pronoun). • Chosen name and pronouns are to be recorded on electronic system. |

• Trans people will have access to underwear appropriate to their preference. • Sentenced trans people will be given clothing according to the prison in which they are placed. • Trans people on remand will usually be allowed to wear their own clothing. • Trans people should be able to purchase cosmetics and personal care items. • Trans people may apply to the General Manager to wear a wig. |

• Trans people will be referred to the prison medical officer if medical treatment is required. • Trans people may request gender-affirming treatment while in custody; however, this is likely to result in placement in a prison according to their gender assigned at birth, rather than the gender to which they now identify. |

| WA | • Initial placement is based on legal documentation. • Trans people will initially be offered a single cell. • Request for review can take over a month. • Factors considered in review include security of the prison, risk to self and others, access to appropriate medical care and the trans person’s preference. • Trans people will have access to sanitation facilities to maximise their safety and dignity. |

• Trans person’s chosen name and pronouns (e.g. she, he or they) are to be used. • Chosen name is to be noted in electronic system. |

• Trans people will be provided with clothing, underwear and toiletries appropriate to their self-identified gender. • Provision of personal care items (e.g. cosmetics) appropriate to self-identified gender will be considered. |

• Standard of healthcare services equal to the community is provided. • Trans people will be clinically assessed and managed according to their needs. |

According to NSW Anti-discrimination Act 1977, a person is ‘recognised’ as transgender if a new birth certificate has been issued to the person specifying the person’s gender.

Policy notes elective gender-affirming surgery procedures are not routinely performed in Tasmanian public hospitals.

Table 3.

Policy scores against human rights standards. a

| Nelson Mandela Rules | Yogyakarta Principles | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placement | Name/pronouns | Clothing/grooming | Healthcare | Placement | Name/pronouns | Clothing/grooming | Health care | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| ACT | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | × | ✔ | × | × | × | ✔ |

| NSW | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✔ | × | ✔ | × | × | × | × |

| NT | × | × | × | × | ✔ | × | ✔ | × | ✔ | × | × | ✔ | × | ✔ | ✔ |

| NZ | ✔ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✔ | ✔ | × | × | × | ✔ | × |

| QLD | ✔ | × | × | ✔ | × | × | ✔ | ✔ | × | ✔ | × | × | × | ✔ | ✔ |

| SA | ✔ | × | × | × | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | × | × | ✔ | × | ✔ | × | ✔ | ✔ |

| TAS | × | × | × | × | ✔ | ✔ | × | × | × | × | × | ✔ | × | ✔ | × |

| VIC | × | × | × | × | ✔ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✔ | ✔ |

| WA | ✔ | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ✔ | × | ✔ | × | ✔ | × |

Human rights standards as per Table 1.

Figure 1.

Concordance between corrections policies and human rights standards.$

Placement

ACT, NSW, NT, Tasmanian and Victorian policies all included a principle that trans people should be accommodated in a prison according to their gender identity, unless there are overriding safety or security concerns (ACTCS, 2018, 2022b; CSNSW, 2017, 2021; CV, 2021; NTCS, 2021; TPS, 2018). ACT, Queensland, SA, Tasmania, Victoria and WA specifically noted they would consider the person’s wishes in placement decisions (ACTCS, 2018; CV, 2021; QCS, 2023b; SADCS, 2018; TPS, 2018; WACS, 2022). Victoria noted initial placement according to the legal documentation from the Courts or police would be reviewed within 3 days (CV, 2021). In NSW, ‘recognised’ trans people, who have legally changed their gender on their birth certificate following gender-affirming surgery (Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 [NSW] s. 4; Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1995 [NSW] s. 32B), will be placed in a prison according to their gender identity without the same assessment as other trans people (CSNSW, 2017, 2021). Non-binary people will be automatically placed in a men’s prison for assessment and placement determination (CSNSW, 2017). Queensland also differentiates between trans people who have had gender-affirming surgery, who will be automatically placed according to their legal gender identity, and those who have not, who will undergo a case-by-case assessment (QCS, 2023b). Initial placement in NZ is determined by a person’s warrant or current birth certificate, if available, and requires application for a placement review (Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2016b). Placement in WA is also based on legal documentation and applications for review may take over a month (WACS, 2022). In SA, placement decisions are made on a case-by-case basis (SADCS, 2018).

Names and pronouns

All jurisdictions had policies requiring staff to use a trans person’s chosen name and pronouns, and all except Queensland required documentation of these details in the electronic management system (ACTCS, 2018; Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2016a; CSNSW, 2017, 2022; CV, 2021; NTCS, 2021; QCS, 2023b; SADCS, 2018; TPS, 2018; WACS, 2022). ACT, NT, NZ, SA, Victoria and WA policies considered pronouns and/or recording the gender identity of non-binary people (ACTCS, 2018; Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2016a; CV, 2021; NTCS, 2021; SADCS, 2018; WACS, 2022). However, variation in the functionality and use of electronic management systems was evident. For example, NZ policy stated a trans person’s name should be recorded in a ‘transgender alert comment box’ unless they have legally changed their name (Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2016a). In Tasmania, a trans person’s chosen name should be recorded as an alias (TPS, 2018).

Gender-affirming clothing and grooming items

ACT, NSW, NZ and WA policies stated trans people would be provided with appropriate clothing and underwear to align their appearance with their gender identity (ACTCS, 2022a; Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2016a; CSNSW, 2017; WACS, 2022), including preferences for non-binary people in NSW. NT, SA, Tasmanian and Victorian policies only mentioned the provision of appropriate underwear, with Victoria noting people on remand should be allowed to wear their own clothing (CV, 2021, 2022; NTCS, 2021; SADCS, 2018; TPS, 2018). SA, Tasmania and Victoria stated sentenced people would be issued clothing as per the facility in which they were housed (CV, 2021; SADCS, 2018; TPS, 2018). In Queensland, the provision of appropriate clothing and grooming items is discussed at a multidisciplinary case conference 7 days after the person’s arrival (QCS, 2023b). ACT, NSW, Tasmania and Victoria permit the purchase of some cosmetic and personal care items without discrimination by gender (ACTCS, 2022a; CSNSW, 2017; CV, 2021; TPS, 2018). In NT and NZ, applications must be made for cosmetic items (Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2016a; NTCS, 2021). NZ policy lists sanitary products as only available for females, which may lead to health and personal hygiene issues for trans men or non-binary people who menstruate (Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2020). In WA, trans people will be provided with appropriate toiletries and additional personal care items, such as cosmetics, will be considered (WACS, 2022). SA policy states cosmetics will not be made available in men’s prisons (SADCS, 2018).

Gender-affirming healthcare

NSW, NZ, Tasmanian and WA policies stated trans people would have access to gender-affirming treatment in prison as in the community (Ara Poutama Aotearoa Health Services, 2021; CSNSW, 2017; TPS, 2018; WACS, 2022). In particular, the Ara Poutama Aotearoa gender-affirming healthcare guidelines were a positive example of a comprehensive, culturally appropriate policy supporting gender-affirming healthcare based on self-determination and informed consent. However, the publicly available Ara Poutama Aotearoa Prison Operations Manual did not refer to these guidelines (Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2016a, 2016b). In SA, trans people can access hormone therapy through the prison health service, but requests for gender-affirming surgery will be considered only for those with at least a 5-year non-parole period (SADCS, 2018). In NT, gender-affirming surgery requests depend on sentence length and the ‘good order’ of the institution (NTCS, 2021). Victorian policy stated trans people may access gender-affirming treatment through prison health services; however, it also noted choosing to commence gender-affirming treatment will likely result in placement according to sex assigned at birth rather than identified gender (CV, 2021). In Queensland, treatment is discussed at a multidisciplinary case conference 7 days after the person’s arrival (QCS, 2023b). ACT did not have a policy about healthcare for trans people in prison.

Discussion

Concordance with human rights

Overall, corrections policy for trans people in Australia has progressed. In 2000, placement was genitalia-based in ACT, NT and SA, with no available policies in Queensland, Tasmania or Victoria (Blight, 2000). In 2017, placement was still genitalia-based in NT, Queensland and SA, with no available policies in WA, Tasmania or NT (Lynch and Bartels, 2017). This review found policies in all jurisdictions. Policies in ACT, NSW, NT, Tasmania and Victoria stated trans people should be accommodated in a prison according to self-identified gender identity, except if safety or security concerns overrule (ACTCS, 2018; CSNSW, 2017; CV, 2021; NTCS, 2021; TPS, 2018). However, placement in either a men’s or women’s prison remain the only options in Australia and NZ, without any specific policies or accommodation options for non-binary people. NZ and WA policies stipulated initial placement based on legal documentation (Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2016b; WACS, 2022), which in both jurisdictions currently requires medical treatment to change (Gender Reassignment Act 2000 [WA] s. 14; Moran, 2021), and had a complex review process. Queensland policy discriminated based on legal and surgical gender transition (QCS, 2022, 2023a, 2023b).

Consistent across all jurisdictions was the requirement for staff to address trans people using their chosen name and pronouns. Queensland has progressed from previously requiring trans people to be addressed by the name on their birth certificate or warrant (Rodgers et al., 2017). ACT, NT, NZ, SA, VIC and WA considered the need to document and use a person’s non-binary gender identity or pronouns (ACTCS, 2018; Ara Poutama Aotearoa, 2016a; CV, 2021; NTCS, 2021; SADCS, 2018; WACS, 2022). All jurisdictions considered trans people’s needs for appropriate clothing and grooming items, but only ACT and NSW enabled access to gender-affirming clothing, underwear and grooming items without additional barriers, and only NSW considered appropriate clothing and grooming items for non-binary people (ACTCS, 2022a; CSNSW, 2017). Progress has been made in policy for gender-affirming healthcare, which in 2017 was only protected in policy in NSW but is now discussed in policies for NSW, NT, NZ, Queensland, SA, Tasmania, Victoria and WA (Ara Poutama Aotearoa Health Services, 2021; CSNSW, 2017; CV, 2021; Lynch and Bartels, 2017; NTCS, 2021; QCS, 2023b; SADCS, 2018; TPS, 2018; WACS, 2022).

In this review, NSW policy had the highest concordance with human rights standards. It included principles that incarcerated trans people should be housed according to gender identity, addressed by their chosen name and pronouns, supported in their gender expression and able to continue or commence gender-affirming healthcare in prison (CSNSW, 2017). However, it stated non-binary people would be initially placed in a men’s prison before a longer-term placement decision would be made. Also, consistent with NSW legislation, it discriminated based on surgical and legal gender affirmation (Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 [NSW] s. 4; Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1995 [NSW] s. 32B). This highlights challenges for policymakers when legislative barriers to legal gender affirmation still exist. Some policies, e.g. in Victoria, attempt to manage this issue with an urgent placement review for incarcerated trans people and interim protective measures, such as separation from others (CV, 2021). However, this approach may still leave trans people feeling isolated or unsafe in a prison of the incorrect gender for several days. An explicit policy statement of the right to treatment and housing according to gender identity would affirm non-discrimination in prisons regardless of legislation, acknowledging the lack of options for non-binary people while correctional facilities continue to be based on a gender binary system.

SA policy had the lowest concordance with human rights standards in this review. Although placement on a case-by-case basis should enable appropriate consideration of individual circumstances, preferences and safety concerns, SA policy does not include an overarching principle supporting placement based on self-determined gender identity (SADCS, 2018). People placed in men’s prisons cannot access cosmetics. Hormone therapy is available through prison health services; however, access to gender-affirming surgery is limited to those with at least a 5-year non-parole period.

Queensland policy also had low concordance with human rights standards. It discriminated against trans people who have not undergone a legal and surgical gender transition. Access to clothing, grooming items and healthcare is discussed at a case conference up to 7 days after the person’s incarceration (QCS, 2023b), potentially leaving trans people in distress and without continuation of hormone therapy for a week or more.

Minority stress and mental health

Minority stress is associated with negative mental health outcomes for trans people (Brömdal et al., 2019b; Coleman et al., 2022; Rogers et al., 2023). Psychological theories link experiences of discrimination, abuse, stigma and rejection with shame, hopelessness and distress, which can precipitate and perpetuate mental health problems (Tebbe and Budge, 2022; Treharne et al., 2020). Gender-related discrimination is correlated with higher rates of self-harm, suicidal ideation and suicidal acts (Veale et al., 2019; Zwickl et al., 2021). This policy review shows gender-related discrimination occurs in corrections services of all jurisdictions in Australia and NZ. Furthermore, policy-related barriers to accessing gender-affirming healthcare in prison contribute to gender-related discrimination, increasing risk of mental health problems, self-harm and suicide for trans people in prison (Brown, 2014; Hughto et al., 2018; Reisner et al., 2016b; Rood et al., 2015). Restrictions on hormone treatment can perpetuate gender dysphoria and distress (Rosenberg and Oswin, 2015).

Policy can promote or discourage affirmation of gender identity in prison. Policies in all jurisdictions requiring staff to address trans people with their correct name and pronouns support affirmation of gender identity in prisons, which could improve the mental health of incarcerated trans people (Russell et al., 2018). However, restrictions on access to appropriate clothing or grooming items make it more difficult for trans people to socially affirm their gender in prison, reinforce stigma against diverse gender expression and may exacerbate gender dysphoria (Brooke et al., 2022; Sanders et al., 2023). Incarcerated trans women in the United States and Australia have spoken about the indignity resulting from policies aiming to ‘defeminize you completely’ (Clark et al., 2023: 34). Policies that reinforce stigma and pathologise trans identities may induce internalised transphobia (Rodgers et al., 2017). For example, NT and SA policies listing the ‘good order’ of the institution as a factor for consideration in gender-affirming surgery requests portray trans people as abnormal and potentially dangerous. These ideas can influence how trans people are seen by others in the institution, e.g. incarcerated trans women in Australia and the United States have reported being called a ‘thing’, ‘dog and mutt’ and ‘sex degenerate’ by custodial staff and others in prison (Clark et al., 2023: 34; Sanders et al., 2023: 15). Trans people may internalise such negative views of their identity, leading to low self-worth and distress (Tan et al., 2019b). Policy change facilitating gender affirmation could instead contribute to pride and resilience against gender minority stress (Du Plessis et al., 2023; Testa et al., 2015).

Gender-related victimisation increases risk of mental illnesses such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and gender-related verbal, sexual and physical violence have been associated with increased risk of suicidality (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006; Zwickl et al., 2021). Gender-related victimisation can result from discriminatory placement policies reinforced by the gender binary prison system. For example, trans women placed in male prisons have been found to be at high risk of harassment, and physical and sexual assault (Brömdal et al., 2019b; Jenness, 2021; Wilson et al., 2017). In this review, only five jurisdictions (ACT, NSW, NT, Tasmania and Victoria) had policies stating a trans person’s preference would be taken into consideration in placement decisions. Experiences of mistreatment or abuse can lead to negative expectations of future harm for trans people (Testa et al., 2015), amplifying the stress of incarceration. For example, a trans woman incarcerated in the United States described the use of verbal abuse and non-affirmation of gender by a nurse ‘to break your spirit’ (Clark et al., 2023: 34). Stigma, fear of victimisation and discrimination may contribute to a trans person’s decision to hide their trans identity or detransition in prison (Hughto et al., 2018), potentially leading to isolation and shame, instead of community connectedness (Testa et al., 2015). Given the barriers that stigma and negative expectations of discrimination impose on a trans person’s decision to seek mental healthcare, it is critical policy and funding support accessibility of culturally safe mental health services in prison (Brömdal et al., 2019a; Strauss et al., 2021a).

Limitations

Although an extensive search was done to find every policy relevant to this research, only publicly available policies or those provided by corrections services could be reviewed. Correctional services may have additional policies, e.g. regarding healthcare, which were not provided. SADCS reported they were updating their policy but did not respond to requests for the new version. Public accessibility to all corrections policies online would improve future research and accountability.

This review is based on a critical appraisal of public adult corrections policy only and therefore does not provide insight into actual conditions in Australian and NZ prisons or information on policy for trans people in youth detention facilities or private prisons. Policies guide structural factors influencing the prison environment but require implementation and adherence by correctional staff. Research has shown trans people are subject to abuse, mistreatment and discrimination by corrections staff despite policy prohibiting such behaviour (Hughto et al., 2022; NZHRC, 2020; Van Hout and Crowley, 2021). The little research on trans youth in justice systems has shown a lack of trans-specific policies, resulting in problems with placement, access to gender-affirming healthcare and treatment by custodial staff (Watson et al., 2023). Creation of safer prison environments for trans people requires not only policy change, but also cultural competence training for custodial staff and healthcare providers; open recognition and support of trans people by those in leadership positions; improved data collection systems; and improved services for access to healthcare, legal support and trans community support (Brömdal et al., 2019a; Clark et al., 2017; Murphy et al., 2023; Sevelius and Jenness, 2017). Further research on implementation of policy changes would be useful to understand their impact on conditions for trans people in prison.

Conclusion

This critical policy review demonstrates progressive changes in corrections policies in Australia and NZ. Policies in all jurisdictions protected a trans person’s right to be addressed with their chosen name and pronouns. NSW corrections policy had high levels of concordance with human rights standards, supporting placement based on self-determined gender identity in principle, correct name and pronoun use and access to gender-affirming clothing, grooming items and healthcare. Ara Poutama Aotearoa’s gender-affirming healthcare guidelines based on self-determination, informed consent and a Kaupapa Māori model of care 1 demonstrate significant progress in the accessibility of gender-affirming healthcare in prison. Australia and NZ could become global leaders in trans rights-based correctional policy if other jurisdictions implemented similar policies. Creation of a national policy would ensure consistency across Australia and rapidly facilitate improvements for jurisdictions which are currently in breach of human rights obligations.

This review also highlights the human rights violations and gender minority stress trans people continue to experience in Australian and NZ prisons. Policies in NSW, NZ, Queensland, SA and WA discriminate based on legal and surgical gender affirmation. Discrimination based on gender identity for access to gender-affirming clothing, grooming items or healthcare exists in all jurisdictions except NSW. Even where placement based on gender self-identification is supported, the practical issues for non-binary people within a gender binary prison system remain. Discrimination and consequent minority stress heighten the burden of incarceration, increasing risk for trans people of mental illness, self-harm and suicidality. Mental health professionals need to be aware of these risks and implement measures to overcome stigma and other barriers to trans people accessing healthcare. Policy-level discrimination would be reduced if governments were to change legislative barriers to legal gender affirmation. We agree with Jamel (2017) that consideration should be given to sentencing options other than incarceration, due to the greater punitive impact and challenges accessing appropriate healthcare for trans people in prison.

These findings inform non-discrimination and protection of trans rights in future corrections policy and service design. Further research is needed in partnership between researchers, correctional services and trans people who have been incarcerated to gain a clearer understanding of the issues and how to address them without causing further harm. In particular, more research is needed on trans people’s views of sex-segregated housing, protective custody and alternative housing solutions. There has been little research to date on the experiences and mental health of trans men, non-binary people, trans people in youth detention facilities or trans people in NZ prisons, especially those who are Māori and Pasifika. More research about indigenous trans people in prison would inform how policies should take intersectionality into account. Engagement with diverse trans communities during policy development is critical for progressive policy reform where the safety and rights of trans people in prison are protected alongside the general prison population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Bonnie Albrecht for her thoughtful feedback on the manuscript. In addition, the authors extend their gratitude to the anonymous reviewer who supplied the Ara Poutama Aotearoa Health Services policy regarding the provision of gender-affirming healthcare in Aotearoa/New Zealand, allowing its inclusion in this critical policy review.

In the healthcare sector, Kaupapa Māori is a term used to ‘reflect an approach to clinical practice that recognises Māori perspectives’ (Durie, 2017, p. 12).

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Laura G Dalzell  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3063-9676

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3063-9676

Annette Brömdal  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1307-1794

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1307-1794

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. Washington, DC: APA. [Google Scholar]

- Anti-Discrimination Act 1977. (New South Wales Legislation). Available at: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-1977-048 (accessed 26 May 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Ara Poutama Aotearoa Health Services (2021) Guideline for Gender Affirming Healthcare for Transgender and Non-Binary Adults and Young Adults in our Care (Internal document). Wellington, New Zealand: Ara Poutama Aotearoa; (New Zealand Department of Corrections). [Google Scholar]

- Ara Poutama Aotearoa (New Zealand Department of Corrections) (2016. a) Management of transgender prisoners. Available at: www.corrections.govt.nz/resources/policy_and_legislation/Prison-Operations-Manual/Induction/I.10-Management-of-transgender-prisoners (accessed 13 November 2022).

- Ara Poutama Aotearoa (New Zealand Department of Corrections) (2016. b) Transgender and intersex prisoner. Available at: www.corrections.govt.nz/resources/policy_and_legislation/Prison-Operations-Manual/Movement/M.03-Specified-gender-and-age-movements/M.03.05-Transgender-prisoner (accessed 13 November 2022).

- Ara Poutama Aotearoa (New Zealand Department of Corrections) (2020) Authorised property rules. Available at: www.corrections.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/10983/Rules-on-authorised-property-made-under-section-45A-v.12-261120.pdf (accessed 13 November 2022).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2023) Prisoners in Australia. Available at: www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/prisoners-australia/latest-release (accessed 24 May 2023).

- Australian Capital Territory Corrective Services (ACTCS) (2018) Corrections Management (Management of Transgender Detainees and Detainees Born with Variations in Sex Characteristics) Policy (Internal document). Canberra, ACT, Australia: ACTCS. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Capital Territory Corrective Services (ACTCS) (2022. a) Corrections management (detainee property) policy. Available at: www.correctiveservices.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/2107605/Detainee-Property-Policy-2022-07112022.pdf (accessed 13 November 2022).

- Australian Capital Territory Corrective Services (ACTCS) (2022. b) Corrections management (placement and shared cell) policy. Available at: www.correctiveservices.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/2095916/Placement-and-Shared-Cell-Policy-2022.pdf (accessed 13 November 2022).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2015) The health of Australia’s prisoners 2015. Available at: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/9c42d6f3-2631-4452-b0df-9067fd71e33a/aihw-phe-207.pdf.aspx?inline=true (accessed 24 May 2023).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2019) The health of Australia’s prisoners 2018. Available at: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/2e92f007-453d-48a1-9c6b-4c9531cf0371/aihw-phe-246.pdf.aspx?inline=true (accessed 24 May 2023).

- Bindel J. (2023) Scotland’s gender recognition bill would have harmed women. Al Jazeera, 3 February. Available at: www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/2/3/scotlands-gender-recognition-bill-would-have-harmed-women (accessed 5 March 2023).

- Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1995. (New South Wales Legislation). Available at: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-1995-062#pt.5A (accessed 26 May 2023).

- Births Deaths Marriages and Relationships Registration Act 2021. (New Zealand Legislation). Available at: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2021/0057/latest/whole.html (accessed 17 August 2023).

- Blight J. (2000) Transgender inmates. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice 168: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal A, Clark KA, Hughto JMW, et al. (2019. a) Whole-incarceration-setting approaches to supporting and upholding the rights and health of incarcerated transgender people. International Journal of Transgenderism 20: 341–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal A, Halliwell S, Sanders T, et al. (2023) Navigating intimate trans citizenship while incarcerated in Australia and the United States. Feminism & Psychology 33: 42–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal A, Mullens AB, Phillips TM, et al. (2019. b) Experiences of transgender prisoners and their knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding sexual behaviors and HIV/STIs: A systematic review. International Journal of Transgenderism 20: 4–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke JM, Biernat K, Shamaris N, et al. (2022) The experience of transgender women prisoners serving a sentence in a male prison: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. The Prison Journal 102: 542–564. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GR. (2014) Qualitative analysis of transgender inmates’ correspondence: Implications for departments of correction. Journal of Correctional Health Care 20: 334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GR, McDuffie E. (2009) Health care policies addressing transgender inmates in prison systems in the United States. Journal of Correctional Health Care 15: 280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne CC, Korobanova D, Yee N, et al. (2022) The prevalence of self-reported mental illness among those imprisoned in New South Wales across three health surveys, from 2001 to 2015. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 57: 550–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassaidy M, Lim L. (2016) The rights of transgender people in prisons. In: Proceedings of the equal justice project symposium, Auckland, New Zealand, 11 May. Available at: https://cdn.auckland.ac.nz/assets/auckland/on-campus/student-support/personal-support/lgbti-students/transgender-people-in-prisons-research-paper-ejp.pdf (accessed 13 January 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Clark KA, Brömdal A, Phillips TM, et al. (2023) Developing the ‘oppression-to-incarceration cycle’ of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women: Applying the intersectionality research for transgender health justice framework. Journal of Correctional Health Care 29: 27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KA, Hughto JMW, Pachankis JE. (2017) ‘What’s the right thing to do?’ Correctional healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes and experiences caring for transgender inmates. Social Science & Medicine 193: 80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Katz M. (2006) Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of Homosexuality 51: 53–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. (2022) Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health 23: S1–S259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrections Victoria (CV) (2021) Management of prisoners who are trans, gender diverse or intersex. Available at: https://files.corrections.vic.gov.au/2021-06/2_63.docx (accessed 13 November 2022).

- Corrections Victoria (CV) (2022) Prisoner property. Available at: https://files.corrections.vic.gov.au/2022-02/2.1.1%20Prisoner%20Property%20-%20Feb22.docx (accessed 13 November 2022).

- Corrective Services New South Wales (CSNSW) (2017) Transgender and intersex inmates. Available at: https://correctiveservices.dcj.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/dcj/corrective-services-nsw/documents/copp/03.08-transgender-and-intersex-inmates-redacted.pdf (accessed 13 November 2022).

- Corrective Services New South Wales (CSNSW) (2021) Classification and placement of transgender and intersex inmates. Available at: https://correctiveservices.dcj.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/dcj/corrective-services-nsw/documents/policies/inmate-classification-and-placement/Inmate_Classification_and_Placement_-_Classification_and_Placement_of_Transgender_and_Intersex_Inmates_Redacted.pdf (accessed 13 November 2022).

- Corrective Services New South Wales (CSNSW) (2022) Reception procedures. Available at: https://correctiveservices.dcj.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/dcj/corrective-services-nsw/documents/copp/01.01-Reception-procedures-unredacted.pdf (accessed 13 November 2022).

- Du Plessis C, Halliwell SD, Mullens AB, et al. (2023) A trans agent of social change in incarceration: A psychobiographical study of Natasha Keating. Journal of Personality 91: 50–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durie M. (2017) Kaupapa Māori: Indigenising New Zealand. In: Hoskins TK, Jones A. (eds) Critical Conversations in Kaupapa Māori. Wellington, New Zealand: Huia Publishers, pp. 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis SJ, Bailey L, McNeil J. (2015) Trans people’s experiences of mental health and gender identity services: A UK study. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health 19: 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Faafoi K. (2021) Incitement of hatred and discrimination: Release of discussion document. Ministry of Justice. Available at: https://consultations.justice.govt.nz/policy/incitement-of-hatred/ (accessed 30 May 2023).

- Fazel S, Hayes AJ, Bartellas K, et al. (2016) Mental health of prisoners: Prevalence, adverse outcomes, and interventions. The Lancet Psychiatry 3: 871–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks N, Mullens AB, Aitken S, et al. (2022) Fostering gender-IQ: Barriers and enablers to gender-affirming behavior amongst an Australian general practitioner cohort. Journal of Homosexuality. Epub ahead of print 27 June. DOI: 10.1080/00918369.2022.2092804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiringer C. (2023) Sex, gender and discrimination. New Zealand Law Commission. Available at: www.lawcom.govt.nz/our-projects/sex-gender-and-discrimination (accessed 24 May 2023).

- Gender Reassignment Act 2000. (Western Australian Legislation). Available at: https://www.legislation.wa.gov.au/legislation/prod/filestore.nsf/FileURL/mrdoc_25526.pdf/$FILE/Gender%20Reassignment%20Act%202000%20-%20%5B02-a0-06%5D.pdf?OpenElement (accessed 12 January 2023).

- Gilmour F. (2020) The impacts of decriminalisation for trans sex workers. In: Armstrong L, Abel G. (eds) Sex Work and the New Zealand Model. Bristol: Bristol University Press, pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, et al. (2011) Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey. Report, National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JE, McSherry BM, O’Reilly RL, et al. (2010) Australian and Canadian Mental Health Acts compared. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 44: 1126–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwyn C. (2006) Crown Law opinion on transgender discrimination. Opinion, Crown Law Solicitor-General, Wellington, New Zealand, 2 August. Available at: www.beehive.govt.Nz/sites/default/files/SG%20Opinion%202%20Aug%202006.pdf (accessed 14 January 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Hansen-Reid M. (2011) Samoan fa’afafine – Navigating the New Zealand prison environment: A single case study. Sexual Abuse in Australia and New Zealand 3: 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hattotuwa S, Hannah K, Taylor K. (2023) Transgressive transitions: Transphobia, community building, bridging, and bonding within Aotearoa New Zealand’s disinformation ecologies March-April 2023. The Disinformation Project. Available at: www.thedisinfoproject.org/ (accessed 24 May 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Hughto JMW, Clark KA, Altice FL, et al. (2018) Creating, reinforcing, and resisting the gender binary: A qualitative study of transgender women’s healthcare experiences in sex-segregated jails and prisons. International Journal of Prisoner Health 14: 69–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughto JMW, Clark KA, Daken K, et al. (2022) Victimization within and beyond the prison walls: A latent profile analysis of transgender and gender diverse adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: NP23075–NP23106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughto JMW, Pletta D, Gordon L, et al. (2021) Negative transgender-related media messages are associated with adverse mental health outcomes in a multistate study of transgender adults. LGBT Health 8: 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Act 1993. (New Zealand Legislation). Available at: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1993/0082/latest/DLM304212.html (accessed 12 January 2023).

- International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) (2007) The Yogyakarta Principles: Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity. Geneva: ICJ. [Google Scholar]

- International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) (2017) The Yogyakarta Principles Plus 10: Additional Principles and State Obligations on the Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics to Complement the Yogyakarta Principles. Geneva: ICJ. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen K, Hu ATY, Stark A, et al. (2023) Prevalence and correlates of incarceration among trans men, nonbinary people, and Two-Spirit people in Canada. Journal of Correctional Health Care 29: 47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamel J. (2017) Transgender offenders within the prison estate: A comparative analysis of penal policy. In: King A, Santos AC, Crowhurst I. (eds) Sexualities Research: Critical Interjections, Diverse Methodologies and Practical Applications. New York: Routledge, pp. 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Jenness V. (2021) The social ecology of sexual victimization against transgender women who are incarcerated: A call for (more) research on modalities of housing and prison violence. Criminology & Public Policy 20: 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jenness V, Fenstermaker S. (2014) Agnes goes to prison: Gender authenticity, transgender inmates in prisons for men, and pursuit of ‘the real deal’. Gender & Society 28: 5–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jenness V, Maxson CL, Matsuda KN, et al. (2007) Violence in California correctional facilities: An empirical examination of sexual assault. Bulletin 2: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kerry SC. (2014) Sistergirls/brotherboys: The status of indigenous transgender Australians. International Journal of Transgenderism 15: 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Leota R. (2020) Letter in Response to a Request Under the Official Information Act 1982. New Zealand Department of Corrections. Available at: www.corrections.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/42324/C124483_Information_on_transgender_and_gender_diverse_individuals_in_custody.pdf (accessed 24 May 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Lydon J, Carrington K, Low H, et al. (2015) Coming out of concrete closets: A report on Black and Pink’s national LGBTQ prisoner survey. Available at: www.blackandpink.org/# (accessed 30 May 2023).

- Lynch S, Bartels L. (2017) Transgender prisoners in Australia: An examination of the issues, law and policy. Flinders Law Journal 19: 185–231. [Google Scholar]