Abstract

Based on morphological and molecular characters, we describe a new species of terrestrial breeding frog of the Pristimantisdanae Group from montane forests of La Mar Province, Ayacucho Department in southern Peru, at elevations from 1200 to 2000 m a.s.l. The phylogenetic analysis, based on concatenated sequences of gene fragments of 16S rRNA, RAG1, COI and TYR suggests that the new species is a sister taxon of a clade that includes one undescribed species of Pristimantis from Cusco, Pristimantispharangobates and Pristimantisrhabdolaemus. The new species is most similar to P.rhabdolaemus, which differs by lacking scapular tubercules and by its smaller size (17.0–18.6 mm in males [n = 5], 20.8–25.2 mm in females [n = 5] in the new species vs. 22.8–26.3 mm in males [n = 19], 26.0–31.9 mm in females [n = 30] of P.rhabdolaemus). Additionally, we report the prevalence of Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis (Bd) in this species.

Key words: Chytridiomycosis, cryptic species, montane forests, morphology, phylogeny

Palabras clave: Bosques montanos, especies crípticas, filogenia, morfología, quitridiomicosis

Resumen Abstract

Describimos una nueva especie de rana terrestre de desarrollo directo del grupo Pristimantisdanae de bosques montanos procedentes de la provincia de La Mar, departamento de Ayacucho al sur de Perú con rango de distribución altitudinal entre los 1200–2000 msnm, en base a caracteres morfológicos y moleculares. El análisis filogenético basado en las secuencias concatenadas de los fragmentos de genes ARNr 16S, COI, RAG1 y TYR sugiere que la nueva especie es un taxón hermano del clado que incluye a una especie de Pristimantis no descrita de Cusco, Pristimantispharangobates y Pristimantisrhabdolaemus. La nueva especie se asemeja más a P.rhabdolaemus; de la cual difiere por la ausencia de tubérculos escapulares y su menor tamaño corporal (17.0–18.6 mm en machos [n=5], 20.8–25.2 mm en hembras [n=5] en la nueva especie vs 22.8–26.3 mm en machos [n=19], 26.0–31.9 mm en hembras [n=30] de P.rhabdolaemus). Adicionalmente, reportamos la prevalencia de Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis (Bd) en esta especie de Terrarana.

Introduction

Pristimantis (Terrarana, Strabomantidae) is an amphibian genus that comprises more than 600 species and occurs thoughout the Americas (Hedges et al. 2008; Padial and De La Riva 2009; Padial et al. 2014; Waddell et al. 2018) from Honduras to Argentina. In Peru, there are 145 Pristimantis, which represents more than 20% of its global richness (Frost 2023). Many species of Pristimantis are morphologically similar despite belonging to different lineages (Elmer and Cannatella 2008; Padial and De la Riva 2009; Siqueira et al. 2009; Kieswetter and Schneider 2013; Hutter and Guayasamin 2015; Ortega-Andrade et al. 2015). The ubiquity of cryptic species in Pristimantis has led to underestimation of the real number of species in the genus (Ortega-Andrade et al. 2015; Guayasamin et al. 2017; Paez and Ron 2019; Carrion-Olmedo and Ron 2021). Nevertheless, the application of molecular techniques in an integrative framework (Dayrat 2005) generated a steady increase in species richness of Pristimantis (Köhler et al. 2022; Reyes-Puig and Mancero 2022). Integrative taxonomy uses more than one line of evidence and discipline to infer species limits (Simpson 1961; Wiley 1978; De Queiroz 2005; Schlick-Steiner et al. 2010; Aguilar et al. 2013; Hutter and Guayasamin 2015) and has become a critical tool to identify and delimit species as well as in understanding species formation (Aguilar et al. 2013; Minoli et al 2014; Rojas et al. 2018; Hillis 2019; Zozaya et al. 2019).

One group with cryptic species includes Pristimantisrhabdolaemus. The taxonomic history is complex because Lynch and McDiarmid (1987) synonymised Pristimantispharangobates with P.rhabdolaemus, until Lehr (2007) again split these two cryptic species. Incorrect labelling of GenBank sequence EF493706 (uploaded during the period from 1987 to 2007 when synonymy was in place) of P.pharangobates as “P.rhabdolaemus” (Heinicke et al. 2007; Padial et al. 2014; Lehr et al. 2017a, b; Acevedo et al. 2020) contributed to taxonomic confusion. Furthermore, specimens from Bolivia incorrectly assigned to P.rhabdolaemus added more confusion. Despite this history, P.rhabdolaemus species limits have not been studied using integrative taxonomy.

Therefore, as part of a study of Pristimantisrhabdolaemus species boundaries, we collected direct development frogs from the montane forests of La Mar Province, Ayacucho Department. Molecular and morphological analyses revealed that the collected specimens belong to an undescribed species. Our goals are to describe the new species and infer its relationships with other species of the Pristimantisdanae species Group, as well as provide information about infection by the fungus Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis (Bd).

Materials and methods

Fieldwork and voucher specimens

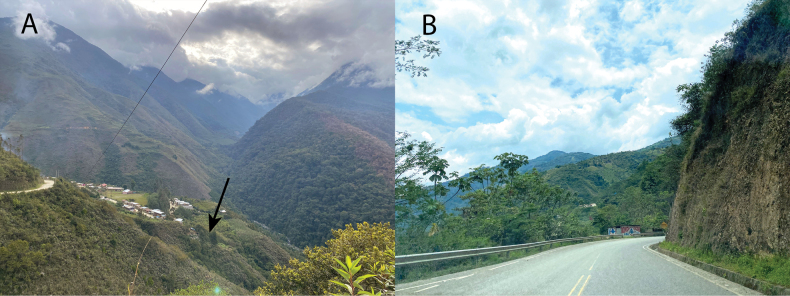

VHA conducted field research in the montane forest of two small valleys (Fig. 1) in the VRAEM (Spanish acronym for Valley of the Rivers Apurimac, Ene and Mantaro), Ayacucho Department, southern Peru. The fieldwork was organised in two stages. The first occurred from November 2018 to June 2019 in the valley of the Chunchubamba River, which goes from Chiquintirca (2900 m a.s.l.) to San Antonio (800 m a.s.l.) in the districts of Anco and Anchihuay (both from La Mar Province). The second field-trip was in November 2021 in the valley of the Piene River, which goes from Yanamonte (2900 m a.s.l.) to San Francisco (800 m a.s.l.) in the Districts of Sivia (Huanta Province) and Ayna (La Mar Province), which included the visit to the type locality of P.rhabdolaemus in Machente (1650 m a.s.l), also previously known as Huanhuachayocc, a name no longer recognised by the locals.

Figure 1.

Montane forest of Cajadela (A) and Machente (B), Ayacucho Department. Type locality of Pristimantissimilaris sp. nov. in Cajadela (A). Note the presence of secondary forest in both localities. Photo A taken on 8 November 2021 and B, on 24 October 2022. Arrow marks the type locality.

We extracted liver tissues by pulling the liver out of a small abdominal incision. We fixed specimens in 10% formaldehyde and stored them in 70% ethanol in the Department of Herpetology of the Museo de Historia Natural Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (MUSM), Lima, Perú. The Ministry of Agriculture issued research, collecting and genetic resources permits (000063-2018-GRA/GG-GRDE-DRAA-DFFS-D, 029-2016-SERFOR-DGGSPFFS and D000012-2022-MIDAGRI-SERFOR-DGGSPFFS-DGSPFS).

Morphology and morphometry

We follow Lynch and Duellman (1997) for the description format, except that we use “vomerine odontophores” instead of “dentigerous processes of vomers” (Duellman et al. 2006) and Duellman and Lehr (2009) for diagnostic characters. We sexed specimens by examining for the presence of vocal slits in mature males and by inspecting gonads in dissected specimens. VHA measured the following distances to the nearest 0.1 mm with digital calipers under a stereomicroscope: 1) snout-vent length (SVL), 2) tibia length (TL, distance from the knee to the distal end of the tibia), 3) foot length (FL, distance from the proximal margin of inner metatarsal tubercle to tip of Toe IV), 4) head length (HL, from the angle of the jaw to tip of snout), 5) head width (HW, at the level of the angle of the jaw), 6) horizontal eye diameter (ED), 7) horizontal tympanum diameter (TY), 8) interorbital distance (IOD), 9) upper eyelid width (EW), 10) internarial distance (IND), 11) eye-nostril distance (EN), straight line distance between anterior corner of orbit and posterior margin of external nares) and one extra measurement: 12) Finger IV disc width (F4). Fingers and toes are numbered pre-axially to postaxial from I–IV and I–V, respectively. We compared the lengths of toes III and V by adpressing both toes against Toe IV; lengths of fingers I and II were compared by adpressing the fingers against each other. Vladimir Díaz Vargas photographed live specimens and VHA preserved the specimens. We used photographs for descriptions of skin texture and colouration. Specimens examined are listed in Appendix 1; other collection acronyms are MUSM = Museo de Historia Natural San Marcos (Lima, Peru); KU = University of Kansas, Museum of Natural History (Kansas, USA); LSUMZ = Louisiana State University Museum of Zoology (Louisiana, USA).

Molecular phylogenetic analysis

We performed a phylogenetic analysis to infer relationships of the new species with other species of the Pristimantisdanae Group (Padial et al. 2014). We used fragments of 16S rRNA, COI, RAG1 and TYR genes. We obtained novel sequences by extracting DNA from six specimens of the new species (MUSM 41030, 41031, 41035, 41036, 41037, 41323) with a commercial extraction kit (IBI Scientific, Iowa, USA). We followed Hedges et al. (2008) and von May et al. (2017) for primers and PCR thermocycling conditions. Primers are listed in Table 1. We purified PCR products using Exosap-IT Express (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). MCLAB (San Francisco, CA) performed Sanger sequencing.

Table 1.

Primers employed in this study for PCR and DNA sequencing. F = forward, R = reverse.

| Locus | Primer | Sequence (5’ – 3’) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S | 16SAR | F | CGCCTGTTTATCAAAAACAT | Meyer (2003) |

| 16SBR | R | CCGGTCTGAACTCAGATCACGT | ||

| COI | dgLCO1490 | F | GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGAYATYGG | Bossuyt and Milinkovitch (2000) |

| dgHCO2198 | R | TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAARAAYCA | ||

| RAG1 | R182 | F | GCCATAACTGCTGGAGCATYAT | Heinicke et al. (2007) |

| R270 | R | AGYAGATGTTGCCTGGGTCTTC | ||

| TYR | Tyr1C | F | GGCAGAGGAWCRTGCCAAGATGT | Lanfear et al. (2012) |

| Tyr1G | R | TGCTGGGCRTCTCTCCARTCCCA |

We follow Padial et al. (2014) and Pyron and Wiens (2011) for species group assignment within Pristimantis and the choice of outgroup taxa. We downloaded from GenBank all available sequences of 16S rRNA, COI, RAG1 and TYR of other species of the P.danae Group and some of the outgroup taxa. We used selected species of the P.conspicillatus Group (P.bipunctatus, P.iiap and P.skydmainos) and P.prolatus as outgroup taxa (Appendix 2).

We used Geneious Prime version 2023.0.1 (Biomatters, http://www.geneious.com/) to assemble pair-end reads, generate a consensus sequence for each gene and align our novel and GenBank sequences with MAFFT included in Geneious as a plug-in. Posteriorly, we concatenated the four genes (16S, COI, RAG1 and TYR) using the default settings in Geneious. We trimmed aligned sequences to a length of 591 bp for 16S, 685 bp for COI, 624 bp for RAG1 and 545 bp for TYR (Fasta file included in doi: 10.5281/zenodo.8278333). To obtain the nucleotide substitution model for each gene, we used PartitionFinder with Python v. 2.7 + Anaconda2 (Lanfear et al. 2017). We inferred a Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree withIqTree (Nguyen et al. 2015) by using its web server (http://iqtree.cibiv.univie.ac.at/) with the following settings: ultrafast bootstrap method, 1000 bootstrap alignments and nucleotide evolution models of GTR+I+G for the gene 16S and for 1st codon position of COI; GTR+G for RAG1, TYR and 3rd codon position of COI; and GTR for 2nd codon positions of COI. Additionally, we generated a tree using Bayesian Inference using the plug-in MrBayes for Geneious Prime with 1.1 × 106 generations and sampling every 200 generations from the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). We determined stationarity by plotting the log-likelihood scores of sample points against generation time; when the values reached a stable equilibrium and split frequencies fell below 0.01, stationarity was assumed. We discarded 100,000 samples and 10% of the trees as burn-in. We consider Bayesian Posterior Probabilities (BPP) > 95% as evidence of support for a clade (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001; Wilcox et al. 2002; Aguilar et al. 2013). We visualised both trees in FigTree v.1.4.4.

Finally, we compare uncorrected p-distances of 591 bp (including gaps) of 16S mithocondrial rRNA gene of Pristimantis included in our analysis (included as a separated file in: doi: 10.5281/zenodo.8278333). To estimate p-uncorrected genetic distances, we used MEGA 11 (Tamura et al. 2021) with a variance estimation method of 1000 bootstrap and rates amongst sites of G+I. We excluded from this analysis species from the sister clade (P.bounides, P.aniptopalmatus, P.albertus, P.attenboroughi, P.humboldti, P.danae, P.ornatus, P.puipui, P.reichlei and P.sagittulus, Fig. 2), except from Pristimantis sp.3 from Bolivia because these specimens had been identified as P.rhabdolaemus on GenBank and P.scitulus, because they are novel sequences for this species.

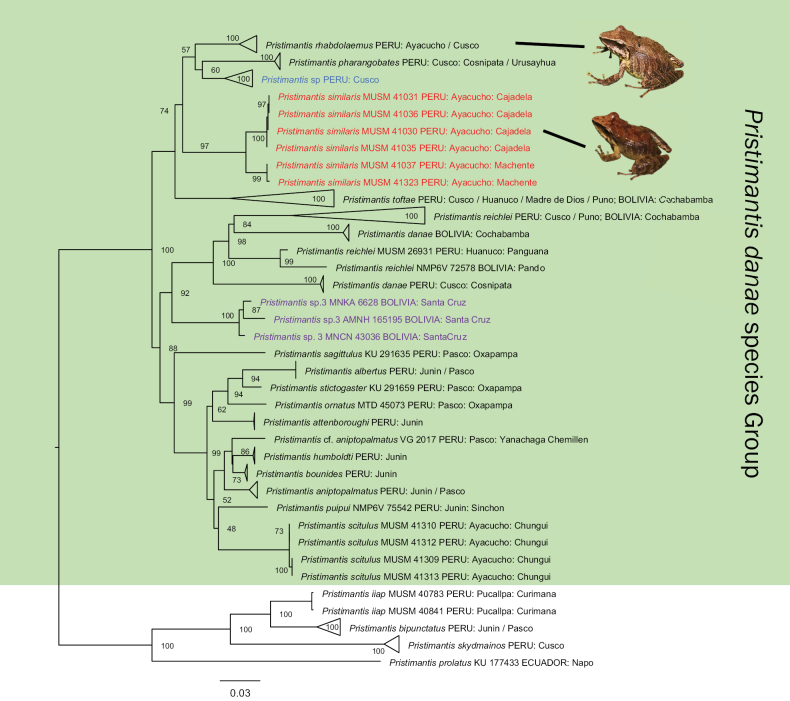

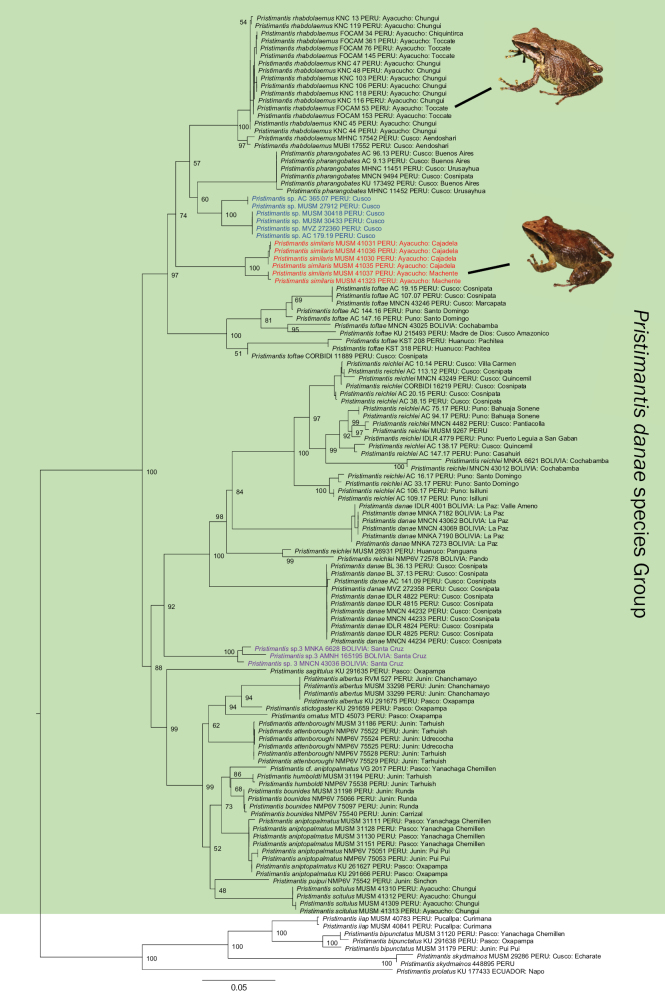

Figure 2.

Maximum Likelihood tree of concatenated genes 16S rRNA, COI, RAG1 and TYR taken from GenBank and novel sequences. Numbers on nodes are bootstrap values (see Materials and Methods section for details). Green shadow corresponds to the ingroup. Pristimantissimilaris sp. nov. in red, Pristimantis sp. 3 from Bolivia in purple and Pristimantis sp. from Cusco in blue. Maximum Likelihood optimal tree with bootstrap node values from the analysis of a concatenated dataset of 591 bp (16S), 685 bp (COI), 624 bp (RAG1) and 545 bp (TYR) of 128 species aligned by MAFFT and node support assessed using 10,000 replicates in IQTREE.

Quantitative PCR assays for fungal infection (Bd)

During fieldwork in 2018, 2019 and 2021, we swabbed live frogs of the new species with a synthetic dry swab (Medical Wire & Equipment #113) to quantify infection by Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis (Bd). We stroked swabs across the skin of juveniles and adults a total of 30 times per individual: five strokes on each side of the abdominal mid-line, five strokes on the inner thighs of each hind leg and five strokes on the foot webbing of each hind leg. We used a standard quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) assay using DNA extracted from swabs to quantify the level of infection (Boyle et al. 2004). Following the protocol of Boyle et al. (2004) and Hyatt et al. (2007), we extracted DNA from swabs using 40 µl of PrepMan Ultra (Applied Biosystems). We analysed each extract once with a QuantStudio 3 qPCR system (ThermoFisher Scientific). We calculated the number of zoospore equivalents (ZE) (i.e. the genomic equivalent for Bd zoospores) by comparing the sample results with a serial dilution of standards (gBlock synthetic standards, IDT DNA, Iowa, USA). We considered any sample with ZE > 1 to be infected or Bd-positive.

Nomenclatural acts

The electronic version of this article in Portable Document Format (PDF) will represent a published work according to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZ) and, hence, the new name contained in the electronic version is effectively published under that Code from the electronic edition alone. This published work and its nomenclatural acts have been registered in ZooBank, the online registration system for the ICZN. The ZooBank LSIDs (Life Science Identifiers) can be resolved and the associated information is viewed through any standard web browser by appending the LSID to the prefix http://zoobank.org/. The LSID for this publication is urn: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:226A24AB-B4BE-4EFD-BF11-D6CA719AB601.

Results

Molecular phylogenetic analysis

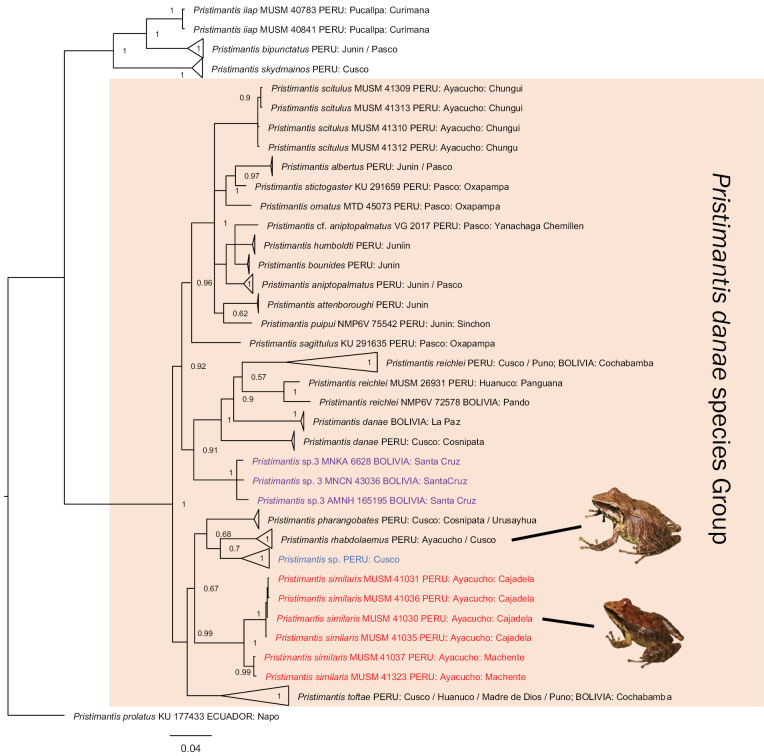

Our Maximum Likelihood phylogeny, based on four concatenated gene fragments (Fig. 2 and Appendix 3 – expanded ML tree), found the new species (in red) included in a clade with specimens of Pristimantisrhabdolaemus, P.pharangobates and P.toftae from their respective type localities, as well as a candidate species from Cusco (in blue). The results from the Bayesian phylogeny (Appendix 4) are largely congruent with the results from the ML phylogeny.

Pristimantisscitulus is within the danae Group and sister to a clade consisting of P.aniptopalmatus, P.humboldti and P.bounides, but with low support. Both our ML and BI phylogenies recover P.danae as paraphyletic, with individuals from the type locality in Cosñipata (Cusco, Peru) forming part of a clade that includes P.danae specimens from Bolivia and P.reichlei, albeit with low support.

Genetic distances (uncorrected p-distances) for the rRNA 16S gene between P.similaris sp. nov. and species of the P.danae species Group vary from 5.6–6.9% for P.rhabdolaemus, 5.9–6.3% for P.pharangobates, 6.1–6.7% for Pristimantis sp., 6.5–7.5% for P.scitulus, 7.3–7.9% for Pristimantis sp. 3 and 7.7–9.3% for P.toftae (see Suppl. material 1, doi: 10.5281/zenodo.8278333). We also identified two populations within our new species, the first one from the type locality in Cajadela and the second, from Machente. The genetic distances between these populations were 2.7–2.8%.

Fungal infection by Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis (Bd)

We found six out of 18 specimens of P.similaris (30%) infected by the fungus Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis (Bd), with levels of infection varying from 11.5 to 8889.3 zoospore genomic equivalents. Our finding confirms that species of Pristimantis can be infected with the fungus (Catenazzi et al. 2011; Warne et al. 2016), despite their life cycle excluding aquatic stages and, thus, limiting the frogs’ exposure to the aquatic zoospores of Bd.

Species description

Our phylogenetic tree shows a candidate species from Ayacucho with high support and having high genetic distances with closely-related phylogenetic species (see Fig. 2 and Appendix 3). In addition, after a careful examination of its morphology and pattern of colouration, this candidate species shows differences with other species of the P.danae Group. Based on these results, we describe this candidate species from Ayacucho Department as a new species of Pristimantis.

. Pristimantis similaris sp. nov.

106D7E7B-730C-5CAC-B3E9-22BD2BD5E452

https://zoobank.org/BC56FD8A-6EBD-43C9-A446-689FC3253576

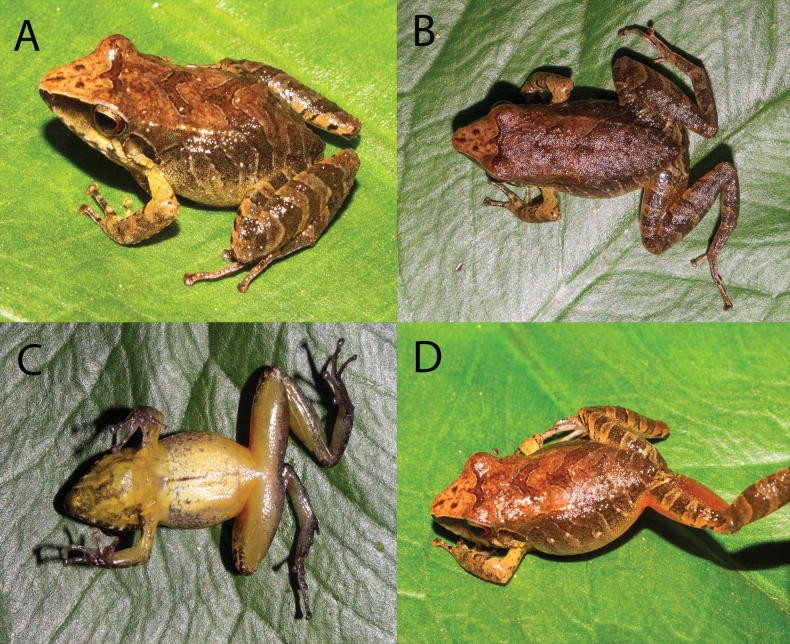

Figure 4.

Pristimantissimilaris sp. nov. (A–D) male. SVL: 17.0 mm. Holotype. MUSM 41030. Photos by Vladimir Diaz-Vargas.

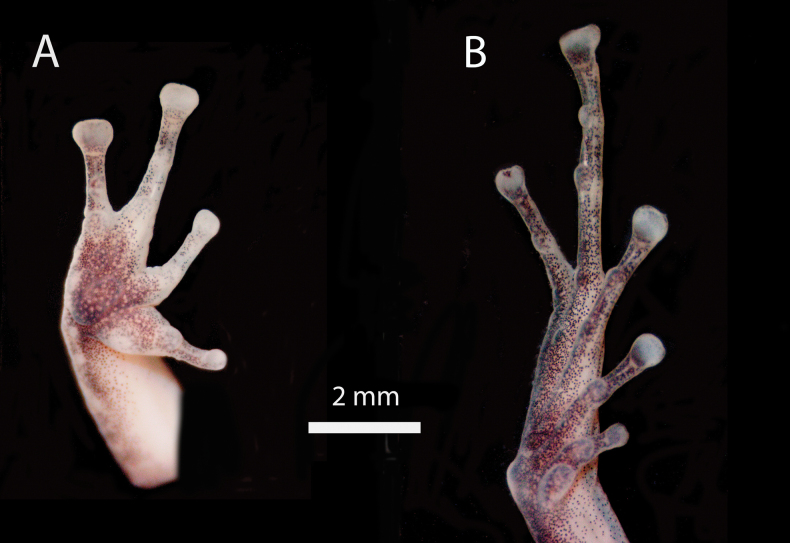

Figure 5.

Pristimantissimilaris sp. nov. A hand B toe. Male. Holotype. MUSM 41030. Photos by VHA.

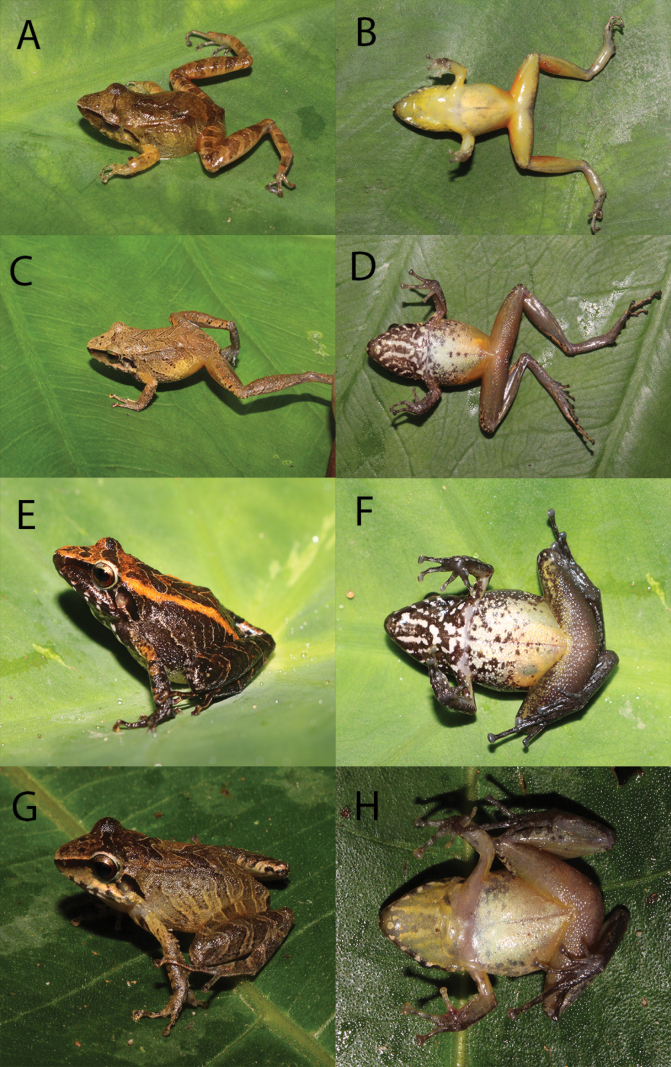

Figure 6.

A–H colour and pattern variation of Pristimantissimilaris sp. nov. Specimen from A–F collected in Cajadela: A, B male MUSM 41029 C, D female MUSM 41031 E, F female MUSM 41032. Specimen G, H male MUSM 41326 collected in Machente. Photos by V. Diaz-Vargas and E. Castillo-Urbina.

Common name.

English: Similar Rubber Frog. Spanish: Rana cutín similar.

Generic placement.

We assign this species to the genus Pristimantis, based on morphology and molecular data (Figs 2, 4, 6).

Type material.

Holotype.MUSM 41030, adult male (Figs 4, 5) from Comunidad Cajadela (12°57'16.50"S, 73°35'0.70”’W, 1460 m a.s.l.), Distrito Anco, Provincia La Mar, Departamento Ayacucho, Peru, collected on 15 November 2018 by V. Herrera-Alva, E. Castillo-Urbina, V. Díaz, M. Fernandez, and J. Gamboa.

Paratypes. Nine specimens. Five adult females (MUSM 41031, 41032, 41035, 41036 and MUSM 41037). Four adult males (MUSM 41029, 41028, 41033 and MUSM 41034). All the specimens were collected at the type locality, except MUSM 41037, which was collected in Comunidad Machente (12°41'31.70"S, 73°51'0.30"W, 1640 m a.s.l.), Distrito Ayna, Provincia La Mar, Departamento Ayacucho, Peru, on 11 November 2021 by V. Herrera-Alva, E. Castillo-Urbina, V. Díaz and K. Ñaccha.

Diagnosis.

A new species of Pristimantis assigned to the P.danae species Group having the following combination of characters: (1) Skin on dorsum shagreen, skin on venter areolate; discoidal and dorsolateral folds present, weak; thoracic fold present; (2) tympanic membrane and tympanic annulus present, distinct, visible externally; (3) snout subaccuminated in dorsal view, round in lateral view; (4) upper eyelid lacking tubercles; EW smaller than IOD; cranial crest absent; two small and flat tubercles above the snout near the eyes; (5) dentigerous processes of vomers low, oblique in five of the paratypes, absent in four paratypes and the holotype; (6) males with vocal slits, subgular vocal sac large extending on to chest and without nuptial pads; (7) Finger I slightly shorter than Finger II; discs of digits expanded, flat and truncated; (8) fingers without lateral fringes; (9) ulnar tubercles present, but diffuse; (10) heel with two to three small and flat tubercles; inner tarsal fold present, small; (11) inner metatarsal tubercle ovoid, 2–3 times larger than outer one; outer metatarsal tubercle small, ovoid; numerous and flat supernumerary tubercles; (12) toes without lateral fringes; basal toe webbing absent; toe V is slightly longer than toe III; toe discs about as large as those on fingers; (13) in life, dorsum varies from blackish to dark brown with three conspicuous chevrons (not very visible in some cases) (Fig. 6); in most of the adults, the anterior surfaces of thighs reddish-orange, posterior surfaces of thighs brown; flanks cream without tubercles; groin same pattern as flanks mostly, some specimens with orange-reddish colouration (Figs 4, 6); venter cream to yellow with black conspicuous reticulations in the throat and black marks in the chest, males present yellow throat with black or white longitudinal reticulations not as conspicuous as in females (Figs 4, 6); iris dark copper-coloured with fine black vermiculations; (14) SVL in adult females 20.8–25.2 mm (mean = 23.4 ± 1.8 SE, n = 5), in adult males 17.0–18.6 mm (mean = 18.1 mm ± 0.7 SE, n = 5).

Comparisons.

Pristimantissimilaris is distinguished from its congeners in Peru and Bolivia by the following combination of characters: skin on dorsum areolate, tympanum and tympanic annulus distinct, weakly-defined discoidal and dorsolateral folds, two small and flat tubercles above the snout near the eyes (not conspicuous in preservative), dorsum dark brown with three darker chevrons, anterior surface of thighs usually orange-reddish and posterior surface of thighs dark brown. Pristimantissimilaris can be distinguished from P.rhabdolaemus and P.pharangobates by the following characters (characters in parenthesis): smaller SVL of 20.8–25.8 mm in ten females and 15.2–18.9 mm in eight males (P.pharangobates 23.1–27.8 mm in females and 15.2–18.2 mm in males; P.rhabdolaemus 25.5–31.9 mm in females and 24.1–26.3 mm in males); absence of scapular tubercles (present in both species); presence of conspicuous longitudinal black and white or yellow marks on the throat and chest (less conspicuous in P.pharangobates and P.rhabdolaemus).

Other species in the Pristimantisdanae species Group that are similar to P.similaris include P.danae, P.reichlei, P.scitulus and P.toftae. Pristimantisdanae and Pristimantisreichlei also have brown chevrons in the dorsum and differ from the new species by the combination of the following characters: males nuptial pads absent (present in P.danae and P.reichlei), dorsolateral folds present (weak in P.danae and absent P.reichlei), small pale spots in the posterior surfaces of the thighs absent (present in P.danae and P.reichlei) and smaller size in P.similaris. Pristimantisscitulus is morphologically similar to P.similaris and has a parapatric distribution (Yuraccyacu, in the Piene Valley, Ayacucho Region). Pristimantissimilaris can be distinguished by lacking a conical tubercle in the upper eyelid and heels (present in P.scitulus), mid-ventral line absent (present in P.scitulus) and absence of marks in the groin or thighs (conspicuous dark spots in the groin that is continuous as marks on the posterior surfaces of the thighs in P.scitulus). Pristimantistoftae is a smaller species that is superficially similar to P.similaris. The new species can be distinghished by the absence of coloured marks or spots in the groin or other parts of its body (yellow spot in the groins of P.toftae), absence of labial bar (presence of a white labial bar in P.toftae).

Pristimantissimilaris is also similar to some species in the Pristimantisconspicillatus species Group, which includes P.bipunctatus, P.skydmainos and P.iiap. The parapatric Pristimantisbipunctatus (found in Calicanto at 1940 m. a.s.l. in the Piene Valley, Ayacucho Region), has dorsum and ventral skin shagreen and areolate, snout long, upper eyelids without tubercules similar to P.similaris, but the latter differs by having finger I slightly shorter than finger II (finger I and finger II about equal length in P.bipunctatus), discs on outer fingers truncated (broadly rounded in P.bipunctatus), scapular tubercules absent (present in P.bipunctatus) and by its smaller size (22.6–28.8 mm in males and 32.4–41.5 mm in females in P.bipunctatus). P.similaris can be distinguished from P.skydmainos by the absence of a mid-dorsal tubercle (present in P.skydmainos), absence of nuptial pads (present in P.skydmainos), finger I smaller than finger II (finger I longer than finger II in P.skydmainos), absence of spots or marks in the posterior surfaces of the thighs (minute cream flecks on the posterior surfaces of the thighs in P.skydmainos) and the absence of W-shaped marks (present in the scapular region in P.skydmainos). Pristimantissimilaris differs from P.iiap from the lowland Amazon of the Ucayali Region by lacking large granules on flanks (present in P.iiap), lacking granules on the upper eyelids (present in P.iiap) and by having finger I shorter than finger II (finger I and II about the same length in P.iiap).

Another species with some resemblance (mainly on the throat in ventral view) to the new species is Pristimantistanyrhynchus. Pristimantissimilaris can be distinguished from P.tanyrhynchus by the absence of nuptial pads in males (present in P.tanyrhynchus) and absence of tubercles on the heel (heel with a conical and large tubercle in P.tanyrhynchus).

Description of the holotype.

Head longer than wide; head length 43% of SVL; head width 35% of SVL; cranial crests absent; snout subaccuminated in dorsal view and in lateral view (Fig. 4A, B, D); eye-nostril distance same as the eye diameter; nostrils slightly protuberant, directed dorsolaterally; canthus rostralis long, straight in lateral and in dorsal views; loreal region concave; upper eyelid without tubercles, width 90% of IOD (see photo in life Fig. 4); supratympanic fold short and narrow, extending from posterior margin of upper eyelid slightly curved to insertion of arm; tympanic membrane and annulus present; distinct conical postrictal tubercles present bilaterally. Choanae small, ovoid, not concealed by palatal shelf of maxilla; dentigerous processes of vomers absent; vocal slits present; tongue longer than short, oval, about a quarter times as long as wide, notched posteriorly, half of the tongue posteriorly free; one large vocal sac extending on to chest.

Skin on dorsum and flanks shagreen, continuous dorsolateral folds present extending from posterior level of tympanic area to level of hind limb insertion; skin on throat, chest and belly areolate; discoidal fold present; thoracic fold present.

Outer ulnar surface without tubercles; palmar tubercle bifid; thenar tubercle ovoid; subarticular tubercles well defined, most prominent on base of fingers, ovoid in ventral view, subconical in lateral view; supernumerary tubercles indistinct; fingers long and thin lacking lateral fringes, Finger I shorter than Finger II; tips of digits of fingers expanded, truncated, with circumferential grooves; nuptial pads absent (Fig. 5A).

Hind limbs long, slender, tibia length 58% of SVL; foot length 49% of SVL; dorsal surfaces of hind limbs tuberculate; inner surface of thighs smooth, posterior surfaces of thighs shagreen, ventral surfaces of thighs smooth; heels each with three small conical tubercles; outer surface of tarsus with one minute low tubercle; inner tarsal fold present; inner metatarsal tubercle ovoid, two times the size of round outer metatarsal tubercle; subarticular tubercles well defined, ovoid in ventral view, subconical in lateral view; few plantar supernumerary tubercles, about one quarter the size of subarticular tubercles; toes without lateral fringes; basal webbing absent; tips of digits expanded, truncated, less expanded than those on fingers, with circumferential grooves; relative length of toes: 1 < 2 < 3 < 5 < 4; Toe V slightly longer than Toe III (tip of digit of Toe III and Toe V not reaching distal subarticular tubercle on Toe IV; Fig. 5B).

Measurements (in mm) of the holotype.

SVL 17.0; tibia length 9.9; foot length 8.4; head length 7.3; head width 5.9; eye diameter 2.3; inter orbital distance 1.9; upper eyelid width 1.7; internarial distance 2.0; eye-nostril distance 2.3; tympanum length 1.0; tympanum height 1.1; forearm length 4.3.

Colouration of the holotype in life

(Fig. 4). In life, dorsum dark brown with three conspicuous chevrons; flanks cream without tubercles, groin same pattern as flanks with orange-reddish colouration; anterior surfaces of thighs reddish-orange, posterior surfaces of thighs brown; venter cream to yellow with black conspicuous reticulations in the throat and black marks in the chest; iris dark copper-coloured with fine black vermiculations (Fig. 4).

Colouration of the holotype in preservative.

The dorsal ground colouration is pale brown with three browner chevrons; narrow blackish canthal and supratympanic stripes; flanks pale brown with dark brown and cream flecks forming irregularly-shaped diagonal bars; groin and anterior surfaces of thighs brown with dark brown flecks; chest, belly and ventral surfaces of thighs pale cream, throat pale cream and grey-striped; palmar and plantar surfaces and fingers and toes dark brown; iris pale grey.

Variation.

All specimens have the same general appearance, with three chevrons on the dorsum. MUSM 41029 is completely yellow and lacks marks on the chest or throat. MUSM 41032 has two brown-yellowish longitudinal bars on the dorsolateral folds. MUSM 41341 is blackish-brown and the three chevrons are not very visible (Fig. 6). Some individuals (MUSM 41030–2, 41036–7) lack the dentigerous processes of vomers. Morphological measurements ranges and proportions of types are included in Tables 2, 3.

Table 2.

Morphological measurements (mm) of nine paratype specimens of Pristimantissimilaris sp. nov. For abbreviations, see Materials and methods.

| Character | MUSM 41028 | MUSM 41029 | MUSM 41031 | MUSM 41032 | MUSM 41033 | MUSM 41034 | MUSM 41035 | MUSM 41036 | MUSM 41037 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male | Female | Female | Female |

| SVL | 18.1 | 17.7 | 25.2 | 22.7 | 18.8 | 18.6 | 24.7 | 23.4 | 20.8 |

| TL | 10.3 | 10.4 | 14.8 | 13.5 | 10.5 | 10.8 | 14.0 | 14.1 | 12.1 |

| FL | 9.0 | 8.4 | 12.4 | 11.3 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 11.6 | 12.4 | 9.4 |

| HL | 7.2 | 7.2 | 9.6 | 8.9 | 7.3 | 7.9 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 8.9 |

| HW | 5.9 | 6.5 | 8.5 | 7.5 | 6.6 | 6.9 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 7.5 |

| ED | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 2.4 |

| TY | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| IOD | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| EW | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| IND | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| EN | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 2.8 |

| F4 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

Table 3.

Measurements (in mm) and proportions of adult male and female type specimens of Pristimantissimilaris sp. nov.; ranges followed by means and one standard deviation in parentheses. For abbreviations, see Materials and methods.

| Character | Males (n = 5) | Females (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|

| SVL | 17.0–18.6 (18.1 ± 0.7) | 20.8–25.2 (23.4 ± 1.8) |

| TL | 9.9–10.8 (10.4 ± 0.3) | 12.1–14.8 (13.7 ± 1.0) |

| FL | 8.4–9.5 (8.9 ± 0.5) | 9.4–12.4 (11.4 ± 1.2) |

| HL | 7.2–7.9 (7.4 ± 0.7) | 8.9–9.8 (9.3 ± 0.4) |

| HW | 5.9–6.9 (6.5 ± 1.0) | 7.5–8.5 (7.9 ± 0.4) |

| ED | 1.9–2.4 (2.2 ± 0.5) | 2.4–2.9 (2.6 ± 0.2) |

| TY | 1.0–1.1 (1.0 ± 0.1) | 1.0–1.3 (1.2 ± 0.1) |

| IOD | 1.9–2.1 (2.0 ± 0.1) | 2.2–2.4 (2.3 ± 0.1) |

| EW | 1.7–1.8 (1.75 ± 0.05) | 1.9–2.3 (2.1 ± 0.2) |

| IND | 2.0–2.3 (2.1 ± 0.1) | 2.5–2.9 (2.6 ± 0.2) |

| EN | 2.3–2.6 (2.4 ± 0.3) | 2.8–3.1 (2.9 ± 0.2) |

| F4 | 0.7–0.9 (0.8 ± 0.1) | 0.8–1.0 (0.9 ± 0.1) |

| TL/SVL | 0.56–0.59 | 0.57–0.60 |

| HL/SVL | 0.39–0.43 | 0.38–0.43 |

| EN/HL | 0.32–0.34 | 0.30–0.33 |

Etymology.

The specific name corresponds to the Latin word “similar”. This refers to the similarity of the new species and its close phylogenetic relationship with P.rhabdolaemus and P.pharangobates.

Distribution and natural history.

The new species is only known from montane forests of Ayna and Anco in Departamento Ayacucho at elevations from 1200–2000 m a.s.l. in secondary forests (Figs 1, 3). This species was found only at night after 18:00 hours, usually perching on wet leaves 0.5–1.5 m above the ground. Males call rarely and their calls are overshadowed by other male species (Pristimantislacrimosus species Group) calling louder. The species is common and appears to tolerate some human disturbance, because it was found near abandoned farms, less frequented roads and in the sourroudings of abandoned houses. Syntopic species included candidate new species in the Pristimantislacrimosus species Group and candidate new species in the Pristimantisplatydactylus species Group, which were more abundant than the new species. Sympatric species included frogs and toads Gastrothecapacchamama, Nympharguspluvialis, Boanapalaestes, Rhinellainca, Dendropsophusvraemi and Hyalinobactrachiumaff.bergeri; lizards Cercosauramanicata, Stenocercuscrassicaudatus and Potamitesmontanicola; and snakes Dipsascf.peruana, Leptodeiraannulata and Epictiacf.peruviana.

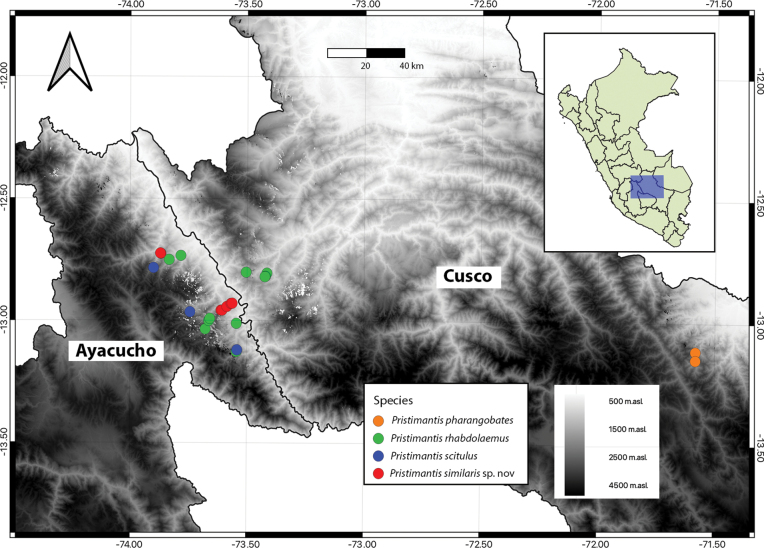

Figure 3.

Distribution map of some species of the P.danae species Group in Ayacucho and Cusco Departments. Raster of altitude from 500 to 4500 m. a.s.l. (white to black). Locality of new species in red circles.

Discussion

We describe Pristimantissimilaris, a new species morphologically similar and phylogenetically related to P.rhabdolaemus and P.pharangobates. Despite their confusing taxonomic history (see Introduction), our phylogenetic analyses show that P.rhabdolaemus and P.pharangobates are distinct evolutionary lineages.

Pristimantisrhabdolaemus was described from mid-altitude montane forests restricted to Ayacucho and Cusco Departments (Duellman 1978). Although we visited the type locality of P.rhabdolaemus (Machente, Ayacucho Department) at 1650 m a.s.l., we could not find any specimens from this species. For that reason, we sequenced specimens of P.rhabdolaemus from Toccate, Anchihuay district in the Ayacucho Department (~ 38 km straight air line to Machente) because morphological analysis and comparison with the type series confirmed that these specimens corresponded to P.rhabdolaemussensu stricto. Padial et al. (2007) reported P.rhabdolaemus from Bolivia on the basis of 16S rRNA of two incorrectly assigned specimens (MNKA 6628 and MNCN 43036), but our concatenated phylogeny suggests that the Bolivian specimens belong to a different and probably undescribed species, Pristimantis sp. 3 (in purple, Fig. 2). Likewise, P.pharangobates should be restricted to Cusco Department until molecular data become available and support the presence of this species in Puno (south-eastern Peru) and Bolivia.

We also found another candidate species from Cosñipata and Alfamayo in Cusco, morphologically similar and phylogenetically related to P.pharangobates and P.rhabdolaemus (in blue, Fig. 2). Additional specimens and analyses are needed to assess the taxonomic status of these potential new species.

The taxonomy of other species of the P.danae species Group requires further work. For instance, specimens identified as P.danae or P.reichlei tend to form paraphyletic groups in phylogenies. We suggest that both species might benefit from future studies clarifying the phylogenetic relationships of their assigned populations. Such studies might include the use of genomic data for these species (including P.toftae) because the use of four genes (three nuclear) in this study was not sufficiently informative to infer with confidence phylogenetic relationships between the most inclusive clades.

Furthermore, our phylogenies include for the first time sequences of P.scitulus from Chungui, Ayacucho previously known only from two type specimens in Yuraccyacu, Ayacucho (at 2600 m a.s.l) and supports the assignment of this species in the P.danae species Group. We also included sequences for the first time of P.iiap (outgroup) and it is recovered in the P.conspicillatus species Group.

According to Swenson et al. (2012), who discussed the endemism of species (birds, mammals, plants and amphibians) in the eastern Andean slopes from the treeline (~ 3500 m a.s.l.) to the Amazon lowlands, most of the montane forests in the eastern Andean slopes of Peru and Bolivia (fig. 7 in Swenson et al. (2012)) are centres of endemism, specially in areas with little field evaluations due to social problems, such as montane forests in Ayacucho Department.

We would like to highlight the areas surroundings the type locality of P.similaris and closely-related species in south-eastern Peru. The Departments of Ayacucho and Cusco have biologically “irreplaceable areas” due to the configuration of the western Andes, the eastern Cordillera de Vilcabamba and the Apurimac River (Swenson et al. 2012). These geographical formations created a deep canyon along the Apurimac River at the border of the Departments of Ayacucho and Cusco (Lehr and Catenazzi 2008; Hazzi et al. 2018; Herrera-Alva et al. 2020), dissecting the Andean cordillera and providing mid-altitude isolated areas. The Apurimac Canyon is an important barrier for the dispersal of amphibians, such as high-altitude species of Terrarana: the Canyon splits the distribution of the genus Phrynopus to the northeast part of the Canyon from the distribution of Bryophryne southwest of the Canyon (Lehr and Catenazzi 2008, 2009, 2010). We believe that this pattern can be extended to mid-altitude montane forest frogs, such as species in the P.danae or P.lacrimosus species groups (pers. com. Ernesto Castillo-Urbina) or the distribution of mid-altitude toads, such as Atelopusmoropukaqumir (northwest of the Apurimac Canyon) and A.erythropus (southeast of the Canyon; Herrera-Alva et al. (2020)). Therefore, we hypothesise that the Apurimac Canyon could have promoted vicariant speciation of morphologically-similar Pristimantis in these montane forests. For instance, P.similaris occurs from 1200 to 2000 m a.s.l. on the northwest of the Apurimac Canyon in Ayacucho Department, while Pristimantis sp. ocurrs from 1200–2000 m a.s.l. in Cusco Department, southeast of the Apurimac Canyon. Nevertheless, the Apurimac Canyon might have not been a geographic barrier to other species, such as P.rhabdolaemus which has been found at both sides of the canyon. One population of this species has an altitude range from 2000–2900 m a.s.l. in Ayacucho (eastern part of the Apurimac River) and the other population ranges from 2000–2100 m a.s.l. in Cusco (western part of the Apurimac River) according to available specimens and sequences. The presence of P.rhabdolaemus on both sides of the Apurimac River will remain hypothetical until more specimens and tissues from Cusco Department become available and are tested against a hypothesis of two different species following an integrative approach.

We also provide information about infection by the fungus Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis (Bd). Chytridiomycosis, caused by the Bd fungus, has negatively affected amphibian communities in the montane forests of Central America and South America (Berger et al. 1998; Lips et al. 2008; Catenazzi et al. 2011; Catenazzi 2015). This pathogen has been associated with amphibian worldwide declines (Berger et al. 1998; Briggs et al. 2005; Lips et al. 2006; Catenazzi et al. 2010; Scheele et al. 2019). Catenazzi et al. (2011) reported a rapid decline in frog species richness and abundance from 1999 to 2008 in the upper Manu National Park (Cusco), which has communities and ecosystems similar to those found in our study area (Ayacucho). The high prevalence of 30% in P.similaris suggests that Bd could be threatening amphibians in the area and that Bd transmission (which is typically associated with aquatic species, given that the infective zoopores are aquatic) occurs in terrestrial frogs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Fieldwork was possible by the Vicerrectorado de Investigación y Posgrado de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (award project code B22100451 to CAP and VHA) and Prociencia - Concytec for their financial support under contract PE501081904-2022 to VHA. Furthermore, we thank Ernesto Castillo-Urbina, Vladimir Díaz, Kimberly Ñaccha, Maura Fernandez and Juan Gamboa for their support in the field collecting the specimens; and to Sebastián Riva-Regalado for the final editions in the photos of this manuscript. We thank Anna Motta and Rafe Brown from KU, Pablo Venegas and Juan Carlos Chavez from CORBIDI and Juan Carlos Chaparro and Maria Isabel Diaz from MUBI for their help and guidance in the process of reviewing museum specimens. Finally, we thank Edgar Lehr, Karen Siu Ting and Rudolf von May for their valuable reviews and comments that improved the quality of our manuscript.

Appendix 1

Specimens analysed from museums. See acronyms in Materials and methods. Underlined codes correspond to type material. Coordinates and altitude when available.

Pristimantispharangobates: AMNH 6099, 153089: Between Abra Accanaco and Pillahuata, Paucartambo, Cusco; KU 173236–173251: Buenos Aires, Cosñipata, Paucartambo, Cusco [-13.15; -71.5833; altitude: 2400 m a.s.l.]; MUBI 4203, 4205, 4209–10, 4212, 4217, 4220, 4222, 4224–4225, 4228, 4390–92, 4395–97, 4399–4400, 4560–61, 4563, 4610: Cosñipata, Paucartambo, Cusco [-13.1153; -715833; altitude: 2750 m a.s.l.]; MUBI 11451–52, 11374–87: Trocha Unión, Cosñipata, Paucartambo, Cusco [-13.1061; -71.5897; altitude: 2780 m a.s.l.]; MUSM 27910: Buenos Aires, Cosñipata, Paucartambo, Cusco; MUSM 32932–35, 32952–60: Paucartambo, Cusco.

Pristimantisrhabdolaemus: CORBIDI 10813, 10815–16: Chiquintirca, La Mar, Ayacucho [-13.0350; -73.6786; altitude: 2635 m a.s.l.]; LSUMZ 26150–51, 26153, 26156, 26182, 26251: Huanhuachayocc, Tambo to Apurimac Road [-12.75; -73.7833]; KU 175082–84: Huanhuachayocc, Tambo to Apurimac Road [-12.73; -73.7833]; MUBI 17541–42, 17552, 17555: Aendoshari Community, La Convención, Cusco [-12.8188; -73.4239; altitude: 2350 m a.s.l.]; MUSM 18505-08: Toccate, La Mar, Ayacucho [-12.9950; -73.6685; altitude: 2080 m a.s.l.]; 30206–08: Cielo Punku, Kimbiri, La Convención, Cusco [-12.8008; -73.5042; altitude: 2100 m a.s.l.]; KNC 44–45, 47–48, 106, 116, 118–20, 122, 130: Chaupichaca, Chungui, La Mar, Ayacucho [-13.1219; -73.5439; altitude: 2040–2345 m a.s.l.].

Pristimantisscitulus: KU 175085: Yuraccyacu, Tambo to Apurimac Road; LSUMZ 26097: Yuraccyacu, Tambo to Apurimac Road [-12.7833; -73.9]; MUSM 41309-10, 41312-13: Chaupichaca, Chungui, La Mar, Ayacucho [-13.12; -73.5228; altitude: 2270–2520 m a.s.l.].

Pristimantis sp.: AMNH 153088, 153090: Between Accanaco and Pillahuata, Paucartambo, Cusco; KU 138877: 7 km WSW Santa Isabel, Cosñipata, Paucartambo, Cusco; MUBI 13317, 13323–24, 13333–34: San Pedro, Paucartambo, Cusco; MUSM 21035, 26269–70, 26276, 30418, 30433, 32934: Suecia, Paucartambo, Cusco. KU 175086–88: Huyro, Quillabamba, Echarate, Cusco; MUBI 13612, 13627, 13661: Mesa Pelada, Huayopata, La Convención, Cusco; MUSM 27911–12: Alfamayo, Huayopata, La Convención, Cusco.

Pristimantis sp. 4.: LSUMZ 26147–48, 26154, 26158: Between Pataccocha and San Jose, Santa Rosa, Ayna, Ayacucho.

Appendix 2

Table A1.

Sequences used from GenBank and new sequences added in this paper.

| N° | Species | Voucher | Group | Locality | Source | 16 S | COI | RAG1 | TYR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pristimantisalbertus | KU 291675 | Ingroup | Peru: Pasco, 0.9 km N, 2.1 km E Oxapampa | Hedges et. al (2008) | EU186695 | – | – | – |

| 2 | Pristimantisalbertus | RvM 527 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Provincia Chanchamayo, Puyu Sacha | Lehr and von May (2017) | KY594751 | – | – | – |

| 3 | Pristimantisalbertus | MUSM 33299 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Provincia Chanchamayo, Cerro San Pedro | Lehr and von May (2017) | KY594750 | – | – | – |

| 4 | Pristimantisalbertus | MUSM 33298 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Provincia Chanchamayo, Cerro San Pedro | Lehr and von May (2017) | KY594749 | – | – | – |

| 5 | Pristimantisaniptopalmatus | KU 261627 | Ingroup | Peru: Pasco, 2.9 km N, 5.5 km E Oxapampa | Hedges et. al (2008) | EF493390 | – | – | – |

| 6 | Pristimantisaniptopalmatus | KU 291666 | Ingroup | Peru: Pasco, 2.9 km N, 5.9 km E Oxapampa | Hedges et. al (2008) | EU186694 | – | – | – |

| 7 | Pristimantisaniptopalmatus | NMP6V 75053 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Pui Pui | Lehr et. al (2017a) | KY006087 | – | – | – |

| 8 | Pristimantisaniptopalmatus | NMP6V 75051 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Pui Pui | Lehr et. al (2017a) | KY006086 | – | – | – |

| 9 | Pristimantisaniptopalmatus | MUSM 31151 | Ingroup | Peru: Pasco, Yanachaga-Chemillen | Lehr et. al (2017a) | KY006085 | – | – | – |

| 10 | Pristimantisaniptopalmatus | MUSM 31130 | Ingroup | Peru: Pasco, Yanachaga-Chemillen | Lehr et. al (2017a) | KY006084 | – | – | – |

| 11 | Pristimantisaniptopalmatus | MUSM 31128 | Ingroup | Peru: Pasco, Yanachaga-Chemillen | Lehr et. al (2017a) | KY006083 | – | – | – |

| 12 | Pristimantisaniptopalmatus | MUSM 31111 | Ingroup | Peru: Pasco, Yanachaga-Chemillen | Lehr et. al (2017a) | KY006082 | – | – | – |

| 13 | Pristimantisattenboroughi | NMP6V 75529 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, near trail from Tasta to Tarhuish, Polylepis forest patch | Lehr and von May (2017) | KY594757 | KY962784 | KY962764 | – |

| 14 | Pristimantisattenboroughi | NMP6V 75528 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, near trail from Tasta to Tarhuish, Polylepis forest patch | Lehr and von May (2017) | KY594756 | KY962783 | KY962763 | – |

| 15 | Pristimantisattenboroughi | NMP6V 75524 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Upper part of Quebrada Tarhuish, ‘Laguna Udrecocha’ | Lehr and von May (2017) | KY594754 | KY962781 | KY962761 | – |

| 16 | Pristimantisattenboroughi | NMP6V 75522 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Quebrada Tarhuish, left bank of Antuyo River | Lehr and von May (2017) | KY594753 | KY962780 | KY962760 | – |

| 17 | Pristimantisattenboroughi | MUSM 31186 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Quebrada Tarhuish, left bank of Antuyo River | Lehr and von May (2017) | KY594752 | KY962779 | KY962759 | – |

| 18 | Pristimantisattenboroughi | NMP6V 75525 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Upper part of Quebrada Tarhuish, ‘Laguna Udrecocha’ | Lehr and von May (2017) | KY594755 | KY962782 | KY962762 | – |

| 19 | Pristimantisbounides | NMP6V 75097 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Quebrada Tasta, ‘’Runda’’ | Lehr et. al (2017b) | KY962797 | KY962790 | KY962774 | – |

| 20 | Pristimantisbounides | NMP6V 75066 | Ingroup | “Peru: Junin, Sector Carrizal, Carrtera Satipo-Toldopampa, km 134” | Lehr et. al (2017b) | KY962796 | – | KY962773 | – |

| 21 | Pristimantisbounides | NMP6V 75540 | Ingroup | “Peru: Junin, Sector Carrizal, Carrtera Satipo-Toldopampa, km 134” | Lehr et. al (2017b) | KY962795 | – | KY962772 | – |

| 22 | Pristimantisbounides | MUSM 31198 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Quebrada Tasta, ‘’Runda’’ | Lehr et. al (2017b) | KY962794 | KY962789 | KY962771 | – |

| 23 | Pristimantiscfaniptopalmatus | VG-2017 | Ingroup | Peru: Pasco, Yanachaga-Chemillen | Lehr et. al (2017a) | KY006088 | – | – | – |

| 24 | Pristimantisdanae | MNCN 44234 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco, Union, Valle de Kosnipata | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192270 | – | – | – |

| 25 | Pristimantisdanae | IDLR 4001 | Ingroup | Bolivia: La Paz: Santa Cruz de Valle Ameno | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192260 | – | – | – |

| 26 | Pristimantisdanae | MNK-A 7182 | Ingroup | Bolivia: La Paz, Huairuro, senda San Jose - Apolo | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192261 | – | – | – |

| 27 | Pristimantisdanae | MNCN 43062 | Ingroup | Bolivia: La Paz, Huairuro, senda San Jose - Apolo | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192262 | – | – | – |

| 28 | Pristimantisdanae | MNCN 43069 | Ingroup | Bolivia: La Paz: Arroyo Huacataya. senda San José y Apolo | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192263 | – | – | – |

| 29 | Pristimantisdanae | MNK-A 7190 | Ingroup | Bolivia: La Paz: Arroyo Huacataya. senda San José y Apolo | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192264 | – | – | – |

| 30 | Pristimantisdanae | MNK-A 7273 | Ingroup | Bolivia: La Paz: Serranía Bella Vista | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192265 | – | – | – |

| 31 | Pristimantisdanae | IDLR 4815 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Unión, Valle de Kosñipata | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192266 | – | – | – |

| 32 | Pristimantisdanae | MNCN 44232 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Unión, Valle de Kosñipata | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192267 | – | – | – |

| 33 | Pristimantisdanae | MNCN 44233 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Unión, Valle de Kosñipata | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192268 | – | – | – |

| 34 | Pristimantisdanae | IDLR 4822 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Unión, Valle de Kosñipata | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192269 | – | – | – |

| 35 | Pristimantisdanae | IDLR 4824 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Unión, Valle de Kosñipata | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192271 | – | – | – |

| 36 | Pristimantisdanae | IDLR 4825 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Unión, Valle de Kosñipata | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192272 | – | – | – |

| 37 | Pristimantisdanae | MVZ 272358 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | von May et. al (2017) | KY652652 | KY672984 | KY672968 | KY681073 |

| 38 | Pristimantisdanae | AC 141.09 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | This paper | OR469891 | – | – | OR542804 |

| 39 | Pristimantisdanae | BL 37.13 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | This paper | OR469893 | OR478457 | OR542831 | OR542792 |

| 40 | Pristimantisdanae | BL 36.13 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | This paper | OR469905 | OR478456 | OR542830 | OR542791 |

| 41 | Pristimantishumboldti | NMP6V 75538 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Quebrada Tarhuish, left bank of Antuyo River, Shiusha | Lehr et. al (2017b) | KY962799 | KY962792 | KY962776 | – |

| 42 | Pristimantishumboldti | MUSM 31194 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Quebrada Tarhuish, left bank of Antuyo River, Shiusha | Lehr et. al (2017b) | KY962798 | KY962791 | KY962775 | – |

| 43 | Pristimantisornatus | MTD 45073 | Ingroup | Perú: Pasco: Oxapampa: Chinche: Cerca de Aquimarca | Hedges et. al (2008) | EU186660 | – | – | – |

| 44 | Pristimantispharangobates | KU 173492 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Buenos aires | Heinicke et. al (2007) | EF493706 | – | – | – |

| 45 | Pristimantispharangobates | MNCN 9494 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | FJ438802 | – | – | – |

| 46 | Pristimantispharangobates | MHNC 11451 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: La Convención: Echarate: Urusayhua | This paper | OR470757 | – | – | – |

| 47 | Pristimantispharangobates | MHNC 11452 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: La Convención: Echarate: Urusayhua | This paper | OR471343 | – | – | – |

| 48 | Pristimantispharangobates | AC 96.13 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Buenos Aires | This paper | OR471423 | OR478463 | – | OR542798 |

| 49 | Pristimantispharangobates | AC 9.13 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Buenos Aires | This paper | – | OR478451 | OR542824 | OR542787 |

| 50 | Pristimantispuipui | NMP6V 75542 | Ingroup | Peru: Junin, Pui Pui Protected Forest, Laguna Sinchon | von May and Lehr (2017b) | KY962800 | – | KY962777 | – |

| 51 | Pristimantisreichlei | MUSM 9267 | Ingroup | Perú | Heinicke et. al (2007) | EF493707 | – | EF493436 | EF493498 |

| 52 | Pristimantisreichlei | MNCN 43012 | Ingroup | Bolivia: Cochabamba: Los Guácharos | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192287 | – | – | – |

| 53 | Pristimantisreichlei | MNK-A 6621 | Ingroup | Bolivia: Cochabamba: Los Guácharos | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192286 | – | – | – |

| 54 | Pristimantisreichlei | MNCN 43249 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: 5 km from San Lorenzo hacia Quince Mil | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192288 | – | – | – |

| 55 | Pristimantisreichlei | IDLR 4779 | Ingroup | Peru: Puno: Entre Puerto Leguia y San Gabán | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192285 | – | – | – |

| 56 | Pristimantisreichlei | MUSM 26931 | Ingroup | Peru: Huanuco: Panguana | Pinto-Sanchez et. al (2012) | JN991461 | JN991392 | – | – |

| 57 | Pristimantisreichlei | CORBIDI 16219 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | von May et. al (2017) | KY652657 | KY672989 | KY672972 | KY681078 |

| 58 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 38.15 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | This paper | OR471610 | OR478458 | OR542832 | – |

| 59 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 113.12 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | This paper | OR471611 | OR478467 | OR542839 | OR542801 |

| 60 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 20.15 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | This paper | OR471619 | OR478454 | OR542828 | – |

| 61 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 138.17 | Ingroup | Peru: Quispicanchi: Soqtapata: Quincemil | This paper | OR471620 | OR478469 | OR542841 | OR542803 |

| 62 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 75.17 | Ingroup | Peru: Puno: PN Bahuaja-Sonene: Punto 4 | This paper | OR471646 | OR478460 | OR542833 | – |

| 63 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 94.17 | Ingroup | Peru: Puno: PN Bahuaja-Sonene: Punto 4 | This paper | OR471650 | OR478462 | OR542835 | – |

| 64 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 16.17 | Ingroup | Peru: Puno, Inambari, Santo Domingo | This paper | OR471653 | – | OR542826 | – |

| 65 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 33.17 | Ingroup | Peru: Puno, Inambari, Santo Domingo | This paper | OR475320 | – | OR542829 | – |

| 66 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 147.17 | Ingroup | Peru: Puno: carretera San Gaban-Ollachea: Casahuiri | This paper | OR471655 | OR478472 | OR542844 | OR542807 |

| 67 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 10.14 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Pilcopata: Villa Carmen | This paper | OR471656 | OR478452 | OR542825 | – |

| 68 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 106.17 | Ingroup | Peru: Puno: Isilluni: Valle Limbani | This paper | OR472333 | OR478465 | OR542837 | OR542799 |

| 69 | Pristimantisreichlei | AC 109.17 | Ingroup | Peru: Puno: Isilluni: Valle Limbani | This paper | OR472388 | – | – | OR542800 |

| 70 | Pristimantisreichlei | MNCN 4482 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco, Pantiacolla | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU712720 | – | – | – |

| 71 | Pristimantisreichlei | NMP6V 72578 | Ingroup | Bolivia: Pando, Bioceanica | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU712719 | – | – | – |

| 72 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | FOCAM 34 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: La Mar: Chiquintirca | This paper | OR472495 | OR478455 | OR478455 | OR542790 |

| 73 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | FOCAM 53 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: La Mar: Toccate | This paper | OR472500 | – | – | – |

| 74 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | FOCAM 76 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: La Mar: Toccate | This paper | OR472501 | OR478461 | OR542834 | OR542797 |

| 75 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | FOCAM 145 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: La Mar: Toccate | This paper | OR472507 | – | – | – |

| 76 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | FOCAM 153 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: La Mar: Toccate | This paper | OR472508 | – | – | – |

| 77 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | FOCAM 361 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: La Mar: Toccate | This paper | OR472509 | – | OR542849 | OR542815 |

| 78 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | KNC 13 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR472494 | – | – | OR542788 |

| 79 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | KNC 47 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR472498 | – | – | OR542795 |

| 80 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | KNC 48 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR472499 | – | – | OR542796 |

| 81 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | KNC 103 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR472502 | OR478464 | OR542836 | – |

| 82 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | KNC 106 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR472503 | OR478466 | OR542838 | – |

| 83 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | KNC 118 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR472505 | OR478468 | OR542840 | – |

| 84 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | KNC 119 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR472506 | – | – | – |

| 85 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | KNC 116 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR472504 | – | – | OR542802 |

| 86 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | KNC 44 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR472496 | – | – | OR542793 |

| 87 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | KNC 45 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR472497 | – | – | OR542794 |

| 88 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | MHNC 17542 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: La Convención: Echarate: Aendoshari | This paper | OR472510 | OR478479 | OR542852 | – |

| 89 | Pristimantisrhabdolaemus | MUBI 17552 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: La Convención: Echarate: Aendoshari | This paper | OR472511 | – | – | OR542819 |

| 90 | Pristimantissagittulus | KU 261635 | Ingroup | Peru: Pasco, 0.9 km N, 2.1 km E Oxapampa | Heinicke et. al (2007) | EF493705 | – | EF493439 | EF493501 |

| 91 | Pristimantisscitulus | MUSM 41310 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR469744 | – | OR542823 | – |

| 92 | Pristimantisscitulus | MUSM 41309 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR469328 | – | – | – |

| 93 | Pristimantisscitulus | MUSM 41312 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR469801 | – | – | – |

| 94 | Pristimantisscitulus | MUSM 41313 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Chungui: Chaupichaca | This paper | OR469804 | – | – | – |

| 95 | Pristimantissimilaris | MUSM 41031 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: La Mar: Cajadela | This paper | OR478195 | OR478473 | OR542845 | OR542808 |

| 96 | Pristimantissimilaris | MUSM 41030 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: La Mar: Cajadela | This paper | OR478198 | OR478475 | OR542847 | OR542812 |

| 97 | Pristimantissimilaris | MUSM 41035 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: La Mar: Cajadela | This paper | OR478199 | OR478476 | OR542848 | OR542813 |

| 98 | Pristimantissimilaris | MUSM 41036 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: La Mar: Cajadela | This paper | OR478200 | – | OR542851 | OR542817 |

| 99 | Pristimantissimilaris | MUSM 41037 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Ayna: Machente | This paper | OR478196 | – | – | OR542810 |

| 100 | Pristimantissimilaris | MUSM 41323 | Ingroup | Peru: Ayacucho: Ayna: Machente | This paper | OR478197 | – | – | OR542811 |

| 101 | Pristimantis sp. | MVZ 272360 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco | von May et. al (2017) | KY652655 | KY672987 | KY681088 | KY681076 |

| 102 | Pristimantis sp. | MUSM 30433 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco | This paper | OR478204 | – | OR542855 | OR542822 |

| 103 | Pristimantis sp. | MUSM 30418 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco | This paper | OR478203 | – | OR542854 | OR542821 |

| 104 | Pristimantis sp. | AC 179.19 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco | This paper | – | – | OR542846 | – |

| 105 | Pristimantis sp. | MUSM 27912 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco | This paper | OR478202 | – | OR542853 | OR542820 |

| 106 | Pristimantis sp. | AC 365.07 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco | This paper | OR478201 | OR478478 | OR542850 | OR542816 |

| 107 | Pristimantis sp3 | AMNH-A 165195 | Ingroup | Bolivia: Santa Cruz: Caballero: Canton San José: Parque Nacional Amboro | Faivovich et. al (2005) | AY843586 | – | – | – |

| 108 | Pristimantis sp3 | MNK-A 6628 | Ingroup | Bolivia: Santa Cruz: Serranía de la Siberia | Padial et. al (2007) | EU192258 | – | – | – |

| 109 | Pristimantis sp3 | MNCN 43036 | Ingroup | Bolivia: Santa Cruz: La Yunga de Mairana | Padial et. al (2007) | EU192257 | – | – | – |

| 110 | Pristimantisstictogaster | KU 291659 | Ingroup | Peru: Pasco, 2.9 km N, 5.5 km E Oxapampa | Heinicke et. al (2007) | EF493704 | – | EF493445 | EF493506 |

| 111 | Pristimantistoftae | KST 208 | Ingroup | Peru: Huanuco, Puerto Inca, Panguana, Rio Yuyapichis (AKA Rio Llullapiches) near Rio Pachitea | Pinto-Sanchez et. al (2012) | JN991439 | – | – | JN991566 |

| 112 | Pristimantistoftae | KST 318 | Ingroup | Peru: Huanuco, Puerto Inca, Panguana, Rio Yuyapichis (AKA Rio Llullapiches) near Rio Pachitea | This paper | OR538542 | – | – | – |

| 113 | Pristimantistoftae | KU 215493 | Ingroup | Peru: Madre de Dios: Cuzco Amazonico: 15 km E de Puerto Maldonado | Heinicke et. al (2007) | EF493353 | – | – | – |

| 114 | Pristimantistoftae | MNCN 43025 | Ingroup | Bolivia: Cochabamba: Los Guácharos | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192293 | – | – | – |

| 115 | Pristimantistoftae | MNCN 43246 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: San Pedro, Valle de Marcapata | Padial and De la Riva (2009) | EU192294 | – | – | – |

| 116 | Pristimantistoftae | AC 107.07 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | von May et. al (2017) | KY652659 | KY672991 | KY672974 | KY681080 |

| 117 | Pristimantistoftae | AC 19.15 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | This paper | OR472575 | OR478453 | OR542827 | OR542789 |

| 118 | Pristimantistoftae | CORBIDI 11889 | Ingroup | Peru: Cusco: Valle de Kosñipata | This paper | – | – | – | OR542818 |

| 119 | Pristimantistoftae | AC 144.16 | Ingroup | Peru: Puno: Inambari: Santo Domingo | This paper | OR472576 | OR478470 | OR542842 | OR542805 |

| 120 | Pristimantistoftae | AC 147.16 | Ingroup | Peru: Puno: Inambari: Santo Domingo | This paper | OR472577 | OR478471 | OR542843 | OR542806 |

| 121 | Pristimantisbipunctatus | MUSM 31120 | Outgroup | Peru: Pasco, Yanachaga-Chemillen | Lehr et. al (2017a) | KY006089 | – | – | – |

| 122 | Pristimantisbipunctatus | MUSM 31179 | Outgroup | Peru: Junin, Pui Pui Protected Forest, Hito 3, Entrada del parque | Lehr and von May (2017) | KY594758 | KY962785 | KY962765 | – |

| 123 | Pristimantisbipunctatus | KU 291638 | Outgroup | Peru: Pasco, 0.7 km S, 4.5 km E Oxapampa | Heinicke et. al (2007) | EF493702 | – | EF493430 | EF493492 |

| 124 | Pristimantisiiap | MUSM 40783 | Outgroup | Peru: Ucayali: Pucallpa: Curimana | This paper | OR470750 | OR478474 | – | OR542809 |

| 125 | Pristimantisiiap | MUSM 40841 | Outgroup | Peru: Ucayali: Pucallpa: Curimana | This paper | OR470749 | OR478477 | – | OR542814 |

| 126 | Pristimantisprolatus | KU 177433 | Outgroup | Ecuador: Napo: Rio Salado | Hedges et. al (2008) | EU186701 | – | – | – |

| 127 | Pristimantisskydmainos | MUSM 29286 | Outgroup | Peru: Cusco: La Convención: Echarate | This paper | OR469849 | – | – | – |

| 128 | Pristimantisskydmainos | 448895 | Outgroup | Peru | Heinicke et. al (2007) | EF493393 | – | – | – |

Appendix 3

Figure A1.

Maximum Likelihood tree non-collapsed of concatenated genes 16S rRNA, COI, RAG1 and TYR taken from GenBank and novel sequences. Numbers on nodes are bootstrap values (see Materials and Methods section for details). Green shadow corresponds to the ingroup. Pristimantissimilaris sp. nov. in red, Pristimantis sp. 3 from Bolivia in purple and Pristimantis sp. from Cusco in blue.

Appendix 4

Figure A2.

Bayesian Tree phylogeny collapsed of concatenated genes 16S rRNA, COI, RAG1 and TYR. Numbers on nodes are posterior probabilities (see Materials and Methods section for details). Orange shadow corresponds to the ingroup. Pristimantissimilaris sp. nov. in red, Pristimantis sp. 3 from Bolivia in purple and Pristimantis sp. from Cusco in blue.

Citation

Herrera-Alva V, Catenazzi A, Aguilar-Puntriano C (2023) A new cryptic species of terrestrial breeding frog of the Pristimantis danae Group (Anura, Strabomantidae) from montane forests in Ayacucho, Peru. ZooKeys 1187: 1–29. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1187.104536

Additional information

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Ethical statement

No ethical statement was reported.

Funding

Funding from Vicerrectorado de Investigación y Posgrado (UNMSM) B22100451 was provided to CAP and VHA, and Prociencia – Concytec PE501081904-2022 to VHA.

Author contributions

Writing - original draft: VHA. Writing - review and editing: VHA, AC, CAP. Investigation: VHA, AC, CAP. Methodology: VHA, AC, CAP. Funding acquisition: CAP, VHA. Data curation: VHA. Formal analysis: VHA, AC. DNA Sequencing: AC. Thesis advice: CAP, AC.

Author ORCIDs

Valia Herrera-Alva https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7858-8279

Alessandro Catenazzi https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3650-4783

Cesar Aguilar-Puntriano https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6372-7926

Data availability

All of the data that support the findings of this study are available in the main text.

Supplementary materials

p-uncorrected distances of 591 pb including gaps of rRNA 16s gene

This dataset is made available under the Open Database License (http://opendatacommons.org/licenses/odbl/1.0/). The Open Database License (ODbL) is a license agreement intended to allow users to freely share, modify, and use this Dataset while maintaining this same freedom for others, provided that the original source and author(s) are credited.

Valia Herrera-Alva, Alessandro Catenazzi, Cesar Aguilar-Puntriano

Data type

xls

References

- Acevedo AA, Armesto O, Palma E. (2020) Two new species of Pristimantis (Anura: Craugastoridae) with notes on the distribution of the genus in northeastern Colombia. Zootaxa 4750: 499–523. 10.11646/zootaxa.4750.4.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar C, Wood Jr PL, Cusi JC, Guzman A, Huari F, Lundberg M, Mortensen E, Ramirez C, Robles D, Suarez J, Ticona A, Vargas VJ, Venegas PJ, Sites Jr JW. (2013) Integrative taxonomy and preliminary assessment of species limits in the Liolaemuswalkeri complex (Squamata, Liolaemidae) with descriptions of three new species from Peru. ZooKeys 47(364): 47–91. 10.3897/zookeys.364.6109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger L, Speare R, Daszak P, Green DE, Cunningham AA, Goggin CL, Scolombe R, Ragan MA, Hyatt AD, McDonald K, Hines HB, Lips KR, Maranteli G, Parkes H. (1998) Chytridiomycosis causes amphibian mortality associated with population declines in the rain forests of Australia and Central America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95(15): 9031–9036. 10.1073/pnas.95.15.9031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossuyt F, Milinkovitch MC. (2000) Convergent adaptive radiations in Madagascan and Asian ranid frogs reveal covariation between larval and adult traits. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97: 6585–6590. 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle DG, Boyle DB, Olsen V, Morgan JAT, Hyatt AD. (2004) Rapid quantitative detection of chytridiomycosis (Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis) in amphibian samples using real-time Taqman PCR assay. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 60(2): 141–148. 10.3354/dao060141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs JM, Knapp AK, Blair JM, Heisler JL, Hoch GA, Lett MS, McCarron JK. (2005) An ecosystem in transition: Causes and consequences of the conversion of mesic grassland to shrubland. Bioscience 55(3): 243–254. 10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[0243:AEITCA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI]

- Carrión-Olmedo JC, Ron SR. (2021) A new cryptic species of the Pristimantislacrimosus group (Anura, Strabomantidae) from the eastern slopes of the Ecuadorian Andes. Evolutionary Systematics 5: 151–175. 10.3897/evolsyst.5.62661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catenazzi A. (2015) State of the world’s amphibians. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 40(1): 91–119. 10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catenazzi A, Vredenburg VT, Lehr E. (2010) Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis in the live frog trade of Telmatobius (Anura: Ceratophryidae) in the tropical Andes. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 92(2–3): 187–191. 10.3354/dao02250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catenazzi A, Lehr E, Rodriguez LO, Vredenburg VT. (2011) Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis and the collapse of anuran species richness and abundance in the upper Manu National Park, southeastern Peru. Conservation Biology 25(2): 382–391. 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayrat B. (2005) Towards integrative taxonomy. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, Linnean Society of London 85(3): 407–417. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00503.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Queiroz K. (2005) Ernst Mayr and the modern concept of species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102(suppl_1): 6600–6607. 10.1073/pnas.0502030102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Duellman WE. (1978) Two New Species of Eleutherodactylus (Anura: Leptodactylidae) from the Peruvian Andes. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science (1903) 81(1): 65–71. 10.2307/3627358 [DOI]

- Duellman WE, Lehr E. (2009) Terrestrial-breeding frogs (Strabomantidae) in Peru. Natur und Tier Verlag.

- Duellman WE, Lehr E, Venegas PJ. (2006) Two new species of Eleutherodactylus (Anura: Leptodactylidae) from the Andes of northern Peru. Zootaxa 1285(1): 51–64. 10.11646/zootaxa.1512.1.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer KR, Cannatella DC. (2008) Three new species of leaflitter frogs from the upper Amazon forests: cryptic diversity within Pristimantisockendeni (Anura: Strabomantidae) in Ecuador. Zootaxa 1784(1): 11–38. 10.11646/zootaxa.1784.1.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faivovich J, Haddad CF, Garcia PC, Frost DR, Campbell JA, Wheeler WC. (2005) Systematic review of the frog family Hylidae, with special reference to Hylinae: Phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 2005(294): 1–240. 10.1206/0003-0090(2005)294[0001:SROTFF]2.0.CO;2 [DOI]

- Frost DR. (2023) Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.2 (30 March 2023). Electronic Database accessible at https://amphibiansoftheworld.amnh.org/index.php. American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA. 10.5531/db.vz.0001 [DOI]

- Guayasamin JM, Hutter CR, Tapia EE, Culebras J, Peñafiel N, Pyron RA, Morochz C, Funk WC, Arteaga A. (2017) Diversification of the rainfrog Pristimantisornatissimus in the lowlands and Andean foothills of Ecuador. PLoS ONE 12(3): e0172615. 10.1371/journal.pone.0172615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hazzi NA, Moreno JS, Ortiz-Movliav C, Palacio RD. (2018) Biogeographic regions and events of isolation and diversification of the endemic biota of the tropical Andes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115(31): 7985–7990. 10.1073/pnas.1803908115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges SB, Duellman WE, Heinicke MP. (2008) New World direct-developing frogs (Anura: Terrarana): molecular phylogeny, classification, biogeography, and conservation. Zootaxa 1737(1): 1–182. 10.11646/zootaxa.1737.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinicke MP, Duellman WE, Hedges SB. (2007) Major Caribbean and Central American frog faunas originated by ancient oceanic dispersal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104(24): 10092–10097. 10.1073/pnas.0611051104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Alva V, Díaz V, Castillo-Urbina E, Rodolfo C, Catenazzi A. (2020) A new species of Atelopus (Anura: Bufonidae) from southern Peru. Zootaxa 4853(3): 404–420. 10.11646/zootaxa.4853.3.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis DM. (2019) Species delimitation in herpetology. Journal of Herpetology 53(1): 3–12. 10.1670/18-123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. (2001) MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17(8): 754–755. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter CR, Guayasamin JM. (2015) Cryptic diversity concealed in the Andean cloud forests: Two new species of rainfrogs (Pristimantis) uncovered by molecular and bioacoustic data. Neotropical Biodiversity 1(1): 36–59. 10.1080/23766808.2015.1100376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt AD, Boyle DG, Olsen V, Boyle DB, Berger L, Obendorf D, Dalton A, Kriger K, Hero M, Hines H, Phillott R, Campbell R, Marantelli G, Gleason F, Colling A. (2007) Diagnostic assays and sampling protocols for the detection of Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 73: 175–192. 10.3354/dao073175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieswetter CM, Schneider CJ. (2013) Phylogeography in the northern Andes: Complex history and cryptic diversity in a cloud forest frog, Pristimantisw-nigrum (Craugastoridae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 69(3): 417–429. 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler J, Castillo-Urbina E, Aguilar-Puntriano C, Vences M, Glaw F. (2022) Rediscovery, redescription and identity of Pristimantisnebulosus (Henle, 1992), and description of a new terrestrial-breeding frog from montane rainforests of central Peru (Anura, Strabomantidae). Zoosystematics and Evolution 98(2): 213–232. 10.3897/zse.98.84963 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfear R, Calcott B, Ho SYW, Guindon S. (2012) PartitionFinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Molecular Biology and Evolution 29: 1695–1701. 10.1093/molbev/mss020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lanfear R, Frandsen PB, Wright AM, Senfeld T, Calcott B. (2017) PartitionFinder 2: New methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Molecular Biology and Evolution 34(3): 772–773. 10.1093/molbev/msw260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr E. (2007) New eleutherodactyline frogs (Leptodactylidae: Pristimantis, Phrynopus) from Peru. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 159(2): 145–178. 10.3099/0027-4100(2007)159[145:NEFLPP]2.0.CO;2 [DOI]

- Lehr E, Catenazzi A. (2008) A new species of Bryophryne (Anura: Strabomantidae) from southern Peru. Zootaxa 1784(1): 1–10. 10.11646/zootaxa.1784.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr E, Catenazzi A. (2009) Three new species of Bryophryne (Anura: Strabomantidae) from the region of Cusco, Peru. South American Journal of Herpetology 4(2): 125–138. 10.2994/057.004.0204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr E, Catenazzi A. (2010) Two new species of Bryophryne (Anura: Strabomantidae) from high elevations in southern Peru (Region of Cusco). Herpetologica 66(3): 308–319. 10.1655/09-038.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr E, von May R. (2017) A new species of terrestrial-breeding frog (Amphibia, Craugastoridae, Pristimantis) from high elevations of the Pui Pui Protected Forest in central Peru. ZooKeys 17(660): 17–42. 10.3897/zookeys.660.11394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr E, Moravec J, Cusi JC, Gvoždík V. (2017a) A new minute species of Pristimantis (Amphibia: Anura: Craugastoridae) with a large head from the Yanachaga-Chemillén National Park in central Peru, with comments on the phylogenetic diversity of Pristimantis occurring in the Cordillera Yanachaga. European Journal of Taxonomy 325: 1–22. 10.5852/ejt.2017.325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr E, Von May R, Moravec J, Cusi JC. (2017b) Three new species of Pristimantis (Amphibia, Anura, Craugastoridae) from upper montane forests and high Andean grasslands of the Pui Pui Protected Forest in central Peru. Zootaxa 4299(3): 301–336. 10.11646/zootaxa.4299.3.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips KR, Brem F, Brenes R, Reeve JD, Alford RA, Voyles J, Carey C, Livo L, Pessier A, Collins JP. (2006) Emerging infectious disease and the loss of biodiversity in a Neotropical amphibian community. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103(9): 3165–3170. 10.1073/pnas.0506889103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips KR, Diffendorfer J, Mendelson JR III, Sears MW. (2008) Riding the wave: Reconciling the roles of disease and climate change in amphibian declines. PLoS Biology 6(3): e72. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lynch JD, Duellman WE. (1997) Frogs of the genus Eleutherodactylus (Leptodactylidae) in western Ecuador: systematic, ecology, and biogeography. Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, 252 pp. 10.5962/bhl.title.7951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JD, McDiarmid R. (1987) Two new species of Eleutherodactylus (Amphibia: Anura: Leptodactylidae) for Bolivia. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 100: 337–346. 10.2307/1447850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer CP. (2003) Molecular systematics of cowries (Gastropoda: Cypraeidae) and diversification patterns in the tropics. Biological Journal Linnean Society 79: 401–459. 10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00197.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minoli I, Morando M, Avila LJ. (2014) Integrative taxonomy in the Liolaemusfitzingerii complex (Squamata: Liolaemini) based on morphological analyses and niche modeling. Zootaxa 3856(4): 501–528. 10.11646/zootaxa.3856.4.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. (2015) IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32(1): 268–274. 10.1093/molbev/msu300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Andrade HM, Rojas-Soto OR, Valencia JH, Espinosa de los Monteros A, Morrone JJ, Ron SR, Cannatella DC. (2015) Insights from integrative systematics reveal cryptic diversity in Pristimantis frogs (Anura: Craugastoridae) from the Upper Amazon Basin. PLoS ONE 10(11): e0143392. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Padial JM, De la Riva I. (2009) Integrative taxonomy reveals cryptic Amazonian species of Pristimantis (Anura: Strabomantidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 155(1): 97–122. 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00424.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padial JM, Castroviejo-Fisher S, Köhler J, Domic E, De la Riva I. (2007) Systematics of the Eleutherodactylusfraudator species group (Anura: Brachycephalidae). Herpetological Monograph 21(1): 213–240. 10.1655/06-007.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]