ABSTRACT

Cannabis use has been stated as a causal risk factor for the occurrence of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. There is a dearth of literature stating the association of cannabis with bipolar disorder. This review aimed to find the repercussion of cannabis use on the onset of the first episode of bipolar disorder and the worsening of the symptoms in pre-existing illness. A thorough systematic review of the existing literature was carried out using the PRISMA guidelines. PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, SCOPUS, and Google-scholar databases were searched for studies fitting our study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 25 studies were included in the systematic review and out of these 25 studies, five prospective studies met the inclusion criteria for the primary outcome meta-analysis. A total sample of 13,624 individuals was included in these five studies. A fixed effect model was used in the meta-analysis of these five studies and it revealed an association between cannabis and bipolar disorder with an effect size of 2.63 (95% CI: 1.95–3.53) (heterogeneity: chi² = 3.01, df = 3 (P = 0.39); I² = 0%). Our findings propose that cannabis use may precipitate or worsen bipolar disorder. This highlights the importance of the detrimental effect of cannabis use on bipolar disorder and the need to discourage cannabis use in the youth culture. High-quality prospective studies are required to delineate the effect of cannabis use on bipolar disorder.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, cannabis, meta-analysis, risk

Cannabis belongs to a family of flowering plants comprising approximately 170 different species, some of which exert psychoactive effects.[1] Cannabis is the most commonly abused illegal substance in many countries. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is mainly considered the active constituent responsible for its psychoactive effects, while other less active compounds include cannabidiol (CBD), Δ8-tetrahydrocannabinol, and other less-studied cannabinoids including cannabinol (CBN) and Δ8-tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV).[2-4] According to Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA), the burden of drug abuse and dependence is around 41% with cannabis being the most commonly abused illicit drug.[5] The lifetime prevalence of cannabis use in bipolar disorder is 64% as compared to 34% in the general population.[6] Bipolar disorder has a convoluted association with cannabis use and there is some evidence that patients with bipolar disorder self-medicate with cannabis to alleviate their symptoms. However, some studies suggest that cannabis use precedes bipolar as well as the recurrence of manic episodes which points towards a causal relationship.[7-9] The association of cannabis use appears to be more apparent with the manic phase rather than depression.[9,10] Few studies have reported that cannabis abuse is a predictor of increased psychosocial difficulties, poor treatment adherence, longer duration, and increased severity of the bipolar disorder.[11-13] Cannabis use has been linked with transient and mild psychotic as well as affective symptoms in individuals with no history of psychiatric disorders.[14] The association between cannabis use and the development of psychosis is strong.[15-18] Also, the use of cannabis has been shown to increase the risk of the first episode of bipolar disorder by five times, while the risk of a major depressive episode is only modestly increased.[19]

This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to find whether cannabis use can be a component in the causal pathway of new-onset bipolar disorder. For this, we have pooled the results only from prospective or longitudinal trials so that a temporal and dose-response relationship can be established. In order to avoid statistical and methodological heterogeniety (since study design and exposure to cannabis at baseline and bipolar disorder differed), we separated the cross-sectional and case-control studies and performed a subgroup analyis as a part of secondary analysis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, SCOPUS, and Google-scholar databases. The search was conducted as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.[20]

We followed PECOS criteria for our search which stands for participants (P): participants with bipolar disorder (both depression and mania); exposure (E): Exposed to cannabis either before developing the first episode of bipolar disorder or concurrent with pre-existing bipolar disorder; comparison (C): comparison or control group; outcome (O): outcome of bipolar disorder; study design (S): published prospective or retrospective longitudinal studies. PICOS process for systematic review and meta-analysis is beneficial when there are limited resources, unlike PICO and SPIDER.[21]

We used the search terms “cannabis OR marijuana OR cannabidiol OR CBD OR cannabinoids OR cannabinol OR tetrahydrocannabivarin OR delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol OR THC” AND bipolar affective disorder type I or type II OR bipolar spectrum OR mania OR hypomania OR manic-depressive psychosis OR bipolar depression OR bipolar mania AND induce OR trigger OR onset OR worsening OR induce. For grey literature, we searched the first 15 pages of google scholar after using the above-mentioned search terms.

Quality assessment

We used Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies to perform a quality assessment of cross-sectional studies for the systematic review [Table 1]. It has four items in the selection criteria and 1 item in comparability, and 3 in the outcome criteria.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of studies

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score (out of 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrawal et al.[23] | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Baethge et al.[24] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Braga et al.[25] | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Dehert et al.[26] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Deng et al.[27] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Denissoff et al.[28] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Etyemez et al.[29] | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Feingold et al.[30] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Henquit et al.[31] | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Johnson et al.[32] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Katz et al.[33] | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Kvitland et al.[34] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Lagerberg et al.[35] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Lagerberg et al.[36] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Marwaha et al.[37] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Lev –Ran et al.[38] | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Soler et al.[39] | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Stone et al.[40] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Shah et al.[11] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Strakowski et al.[6] | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Taub et al.[41] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Van Laar et al.[19] | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Weinstock et al.[42] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Zorilla et al.[43] | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Tjissen et al.[44] | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

Good quality: 3 or 4 stars in the selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in the comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in the outcome/exposure domain.

Fair quality: 2 stars in the selection domain AND 1 or 2 stars in the comparability domain AND 2 or 3 stars in the outcome/exposure domain.

Poor quality: 0 or 1 star in the selection domain OR 0 stars in the comparability domain OR 0 or 1 star in the outcome/exposure domain.[22]

Data extraction

The study data were extracted from July 2022 to December 2022. Data extraction was done by two authors (GM, RJ, and SC2) and was put in pre-defined categories in table format in MS word and excel sheets. Any discrepancy or controversy was sorted out mutually by four authors (GM, RJ, SC1, and SC2).

Data analysis

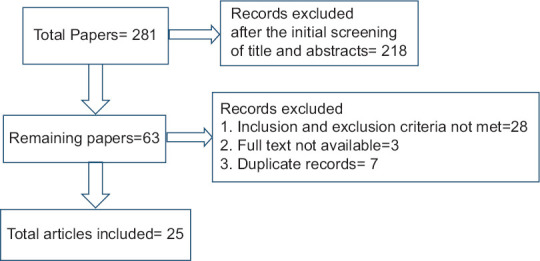

All included studies have been conducted independently. The data analysis was performed in Cochrane’s RevMan software, which is available free for academic purposes. A number of articles were removed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria as shown in the PRISMA chart [Figure 1]. Odds ratios were extracted from the research papers and pooled prevalence was calculated using the inverse variance method, this method estimates effect size by their sample size. To find variations across studies, the fixed effect model was used in the primary outcome analysis since heterogeneity was less than 50% while for the secondary outcome, we used the random effects model (heterogeneity <50%). The Forest plots were created to reflect pooled Odds ratio [Figures 2 and 3] and funnel plots were used for observing publication bias [Figures 4 and 5].

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

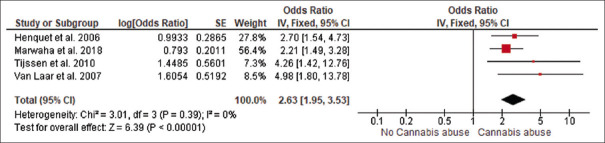

Figure 2.

Pooled effect size of association from longitudinal studies

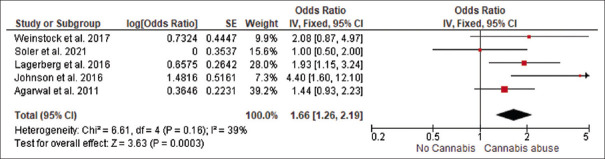

Figure 3.

Pooled effect size of association from cross-sectional studies

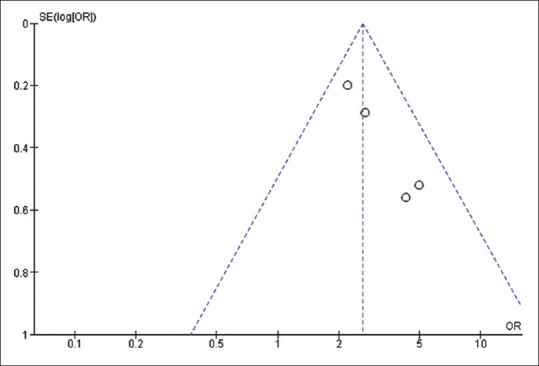

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of longitudinal studies

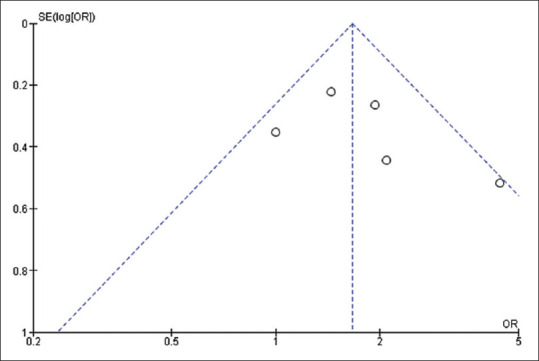

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of cross-sectional/case-control studies

Inclusion criteria

Studies with longitudinal design (either prospective or retrospective) with no threshold or sub-threshold bipolar symptoms at baseline were selected for the primary outcome while case-crontrol or cross-sectional design irrespective of the baseline threshold or sub-threshold bipolar symptoms were selected for the secondary outcome.

The study should include patients of either clinical or sub-clinical bipolar disorder type I and type II.

The study should mention the effect size.

Exclusion criteria

Studies with participants primarily with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, or psychotic illness.

The study should not be a review article, case report, or case series.

Studies that didn’t mention effect size in their findings.

Studies with low/poor quality on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (score of 0 or 1 in the selection domain OR 0 score in the comparability domain OR 0 or 1 score in the outcome/exposure domain).

RESULTS

The search revealed abstracts and on screening, articles were excluded. A number of articles were removed based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria as shown in the PRISMA chart [Figure 1]. Data were extracted from the selected articles in pre-defined tables in MS Excel. Five studies were longitudinal while 20 were cross-sectional. The total sample size of all the included studies was 54,699.

Primary outcome: Pooled effect sizes of the longitudinal studies (with no baseline “bipolar disorder” illness)

The primary aim of this meta-analysis was to shed light on the causal relationship between cannabis abuse and the emergence of bipolar disorder. The longitudinal studies assessing the risk of association between cannabis use and new onset bipolar disorder on follow-up in subjects with no baseline illness were pooled together [Figure 2]. The included studies in the systematic review are 25 [Table 2] but only four longitudinal studies were deemed suitable and were selected for meta-analysis. The fixed effect model was used and pooled odds of association between cannabis use and the emergence of bipolar disorder came out to be 2.63 (95% CI: 1.95–3.53). The heterogeneity between studies was found to be very low and insignificant (I2 = 0%; P = 0.39) [Figure 2]. The funnel plots for publication bias were created, although the number of studies included were less than 10, therefore funnel plots have low power to detect heterogeniety [Figure 4].[45] The age range of the participants was mentioned in two studies out of five and varied from 18 years to 64 years while the mean age was mentioned in three studies out of five. Gender distribution revealed males to be more common (total no male participants = 5898 and female = 6873). The total number of participants was found to be 12771.

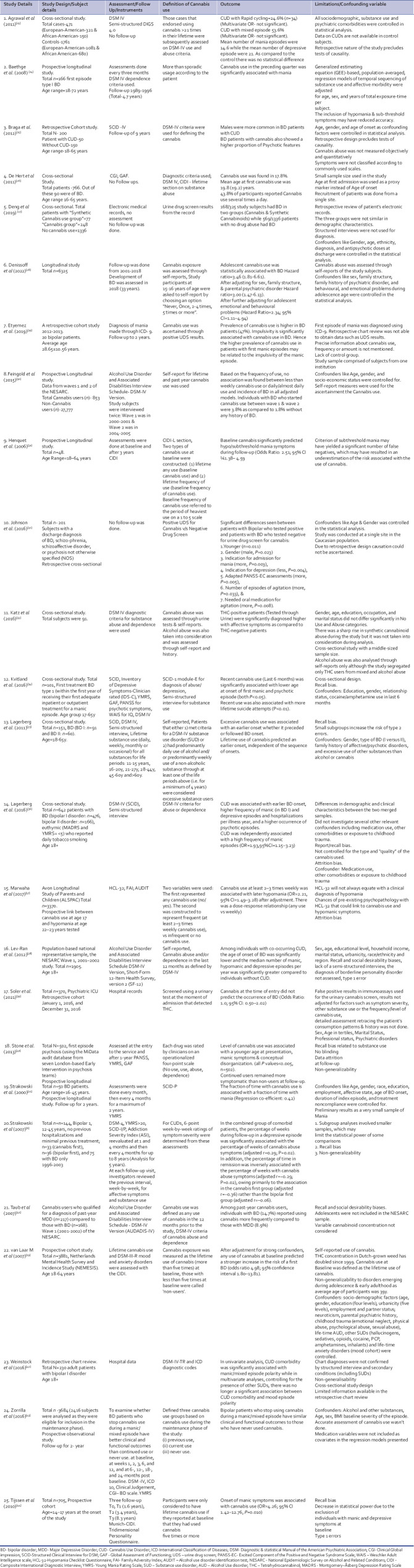

Table 2.

Summary of the included studies

Secondary outcome: Pooled effect sizes of the cross-sectional studies (irrespective of the baseline status of the “bipolar disorder”)

The included studies were cross-sectional in design. They recruited subjects with bipolar disorder and an effect size of the association between cannabis abuse and bipolar disorder was calculated. Four studies mentioned effect sizes that were deemed useful and suitable for the synthesis of the result. The heterogeneity was considerable but insignificant (I2 = 39%; P = 0.16) therefore, a random effect model was used and the effect size was calculated to be 1.66 (95% CI: 1.26–2.19) [Figure 3]. The funnel plots for publication bias were created, although the number of studies included were less than 10, therefore funnel plots have low power to detect heterogeniety [Figure 5].[45] The age range of the participants varied from 18 years to 77 years and the mean age was mentioned in two studies; 39.1 (Johnson et al.[32]) and 42.2 (Weinstock et al.[42]). Gender distribution revealed males to be more common (total no. of male participants = 720 and female = 723).

DISCUSSION

Substance abuse is common in patients with bipolar disorder. It has been found that approximately 60% of patients have substance abuse before the onset of their bipolar disorder. Additionally, there is anecdotal evidence that cannabis is also used to self-medicate.[46,47]

The major research question that this meta-analysis aimed to answer is whether cannabis abuse is a component in the causation pathway. According to Melvyn Susser, five criteria for causality, and proposed three as important. The three factors are the association (strength of probability), the direction of prediction, and time order.[48]

Plausible mechanism

The underlying mechanism linking both cannabis and bipolar disorder is dopaminergic hyperactivity in the mesolimbic region.[49] It has been argued that cannabis has the potential to induce mania through its psychoactive component THC while CBD may help a few patients with bipolar disorder in alleviating their symptoms.[50-52] Long-term intermittent, as well as regular cannabis abuse, can sensitize the dopaminergic system permanently to dopamine-induced affective and non-affective psychosis. Studies by Henquet et al.[31] and Tijssen et al.[44] reported that baseline cannabis abuse was significantly associated with bipolar symptoms rather than cannabis abuse during follow-up. This implies chronic rather than acute exposure is responsible for these symptoms.

Cannabis use, abuse, or dependence?

The criteria for the threshold of occasional cannabis use and dependence was variable across all the studies in our meta-analysis. Most of the papers didn’t use any definitive criteria for the selection of cases. For example, some studies used the Addiction Severity Index and substance use disorder part of the SCID-I/P.[7,24] De Hert et al. used the CIDI and classified substance abuse patients based on the frequency of consumption. Tijssen et al. considered the frequency of use as five times or more to be eligible for the study while De Hert et al. classified patients using cannabis several times a day as “heavy users” while Lagerberg et al. considered participants as “excessive users” to be eligible in the study if they met the criteria of DSM IV or had weekly use of substance abuse.[26,35,44] The method of reporting cannabis abuse was mainly through two methods either self-report or urine examination.

Dose-Response Relationship and Temporal Order

Henquet et al.[31] conducted a study with a large sample size (N = 4185). The study also revealed an increasing trend with the frequency of use and onset of bipolar symptoms. The highest risk was found with the use of cannabis for either 3–4 days/week or nearly everyday use even after adjustment for potential confounders (adjusted OR: 6.94 (95% CI: 2.00–24.06) and 3.43 (95% CI: 1.42–8.26 respectively). This relationship between frequency and onset of symptoms was suggestive of a dose-response relationship. Another study by Tijssen et al.[44] focussed on new-onset subthreshold manic-depressive symptoms and the persistence of symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder at baseline due to cannabis abuse. The onset of sub-threshold manic symptoms was found to be associated with cannabis abuse. Those who abused cannabis five times or more in their lifetime had odds of 4.26 (95% CI: 1.42–12.76) for the development of manic symptoms. Even though a statistically significant association between cannabis abuse and bipolar symptoms was found, the clinical relevance of these results remains ambiguous as both these studies found sub-threshold symptoms of bipolar disorder. Some studies suggest that sub-threshold symptoms align with a clinical diagnosis of mania and subsequently bipolar disorder and this phenomenon can be considered akin to a diagnosis of sub-threshold psychotic symptoms and cannabis abuse.[53,54] Marwaha et al.[37] conducted a prospective study to assess the link between cannabis use at 17 years of age and subsequent development of bipolar disorder at the age of 22–23 years. The participants reporting cannabis 2–3 times/week were found to have two times more risk for developing hypomanic symptoms after adjusting for potential confounders (OR = 2.21; 95% CI: 1.49–3.28). This study also reported a dose-response relationship for hypomania similar to Henquet et al.[31] In a large prospective trial by Van Laar, cannabis was found to be a strong predictor of bipolar disorder even after adjusting for confounders (OR = 4.98; 95% CI: 1.80–13.81). Nonetheless, the dose-response relationship was not found to be strong.[20]

Onset, course, and prognosis of bipolar disorder with co-morbid cannabis dependence

Co-morbid cannabis abuse has a profound effect on the course and prognosis of bipolar disorder. Apart from causation, it has been reported that cannabis abuse can be a prodrome of bipolar disorder and the pathophysiology behind this phenomenon can be due to mood changes, impulsivity, and poor judgment.[9,55] The outcome of bipolar disorder with co-morbid cannabis abuse is poor.[7] The age of onset of the first episode of bipolar disorder was found to be less when there was co-morbid cannabis abuse. The number of episodes of depression or mania as well as their severity was also higher.[23,26,35] The risk of rapid cycling was not found to be higher in cannabis abuse rather there was an increase in the frequency of the mixed episodes.[23] However, one study did not support the finding of an earlier age of onset of mood symptoms and association with substance abuse.[56]

Limitations

Although in our study, we comprehensively reviewed the available literature, the data was still not robust to extrapolate the results as with the available literature, causality could not be established. Since most of the studies used interviews or self-reports to detect cannabis abuse, therefore, the available literature lacked an objective analysis of cannabis abuse. Most of the studies had participants with more than one substance abuse, thereby confounding the results. There were other confounders like sleep disturbances, childhood maltreatment, familial stability, and individual personality feature that make it difficult to discern the relationship between cannabis and bipolar disorder. Also, presence of the psychotic features can create a diagnostic dilemma. We considered both syndromal and subsyndromal symptoms in the analysis as some researchers equate sub-syndromal symptoms with mild mania.[57]

CONCLUSION

The available literature on the role of cannabis in bipolar disorder is not robust as compared to the role of cannabis in psychosis. The available literature on cannabis abuse can be undoubtedly linked to bipolar disorder. Although, with the current literature the hypothesis regarding the causal pathway remains obscure. The plausible causal role of cannabis is of importance in the prevention as well as treatment of bipolar disorder. Further longitudinal studies with a robust methodology for adjusting confounders are needed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Merlin M. Archaeological evidence for the tradition of psychoactive plant use in the old world. Econ Bot. 2003;57:295–323. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rong C, Lee Y, Carmona NE, Cha DS, Ragguett RM, Rosenblat JD, et al. Cannabidiol in medical marijuana: Research vistas and potential opportunities. Pharmacol Res. 2017;121:2138. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrahamov A, Abrahamov A, Mechoulam R. An efficient new cannabinoid antiemetic in pediatric oncology. Life Sci. 1995;56:2097–102. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00194-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ElSohly MA, Radwan MM, Gul W, Chandra S, Galal A. Phytochemistry of cannabis sativa L. Prog Chem Org Nat Prod. 2017;103:1–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-45541-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA. 1990;264:2511–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Fleck DE, Adler CM, Anthenelli RM, Keck PE, Jr, et al. Effects of co-occurring cannabis use disorders on the course of bipolar disorder after a first hospitalization for mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:57–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar S, Chaudhury S, Dixit V. Symptom resolution in acute mania with co-morbid cannabis dependence. Saudi J Health Sci. 2014;3:147–54. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaudhury S, Sudarsanan S, Salujha SK, Srivastava K. Cannabis use in psychiatric patients. Med J Armed Forces India. 2005;61:117–20. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(05)80004-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strakowski SM, Delbello MP. The co-occurrence of bipolar and substance use disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:191–206. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkar J, Murthy P, Singh SP. Psychiatric morbidity of cannabis abuse. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45:182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Fleck DE, Arndt S. The impact of substance abuse on the course of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:477–85. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00900-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strakowski SM, Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, West SA, Sax KW, Hawkins JM, et al. Twelve-month outcome after a first hospitalization for affective psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:49–55. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tohen M, Waternzux CM, Tsuang MT. Outcome in mania: A 4-year prospective follow-up of 75 patients using survival analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:1106–11. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810240026005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Souza DC, Perry E, MacDougall L, Ammerman Y, Cooper T, Wu YT, et al. The psychotomimetic effects of intravenous delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy individuals: Implications for psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1558–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arseneault L, Cannon M, Witton J, Murray RM. Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: Examination of the evidence. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:110–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Os J, Bak M, Hanssen M, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Verdoux H. Cannabis use and psychosis: A longitudinal population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;15(156):319–27. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Large M, Sharma S, Compton MT, Slade T, Nielssen O. Cannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: A systematic meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:555–61. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smit F, Bolier L, Cuijpers P. Cannabis use and the risk of later schizophrenia: A review. Addiction. 2004;99:425–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Laar M, van Dorsselaer S, Monshouwer K, de Graaf R. Does cannabis use predict the first incidence of mood and anxiety disorders in the adult population? Addiction. 2007;102:1251–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, et al. for the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:579. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [[Last accessed on 2023 Apr 12]]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp .

- 23.Agrawal A, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Lynskey MT. Bipolar genome study. Cannabis involvement in individuals with bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:459–61. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baethge C, Hennen J, Khalsa HM, Salvatore P, Tohen M, Baldessarini RJ. Sequencing of substance use and affective morbidity in 166 first-episode bipolar I disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:738–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braga RJ, Burdick KE, Derosse P, Malhotra AK. Cognitive and clinical outcomes associated with cannabis use in patients with bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:242–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Hert M, Wampers M, Jendricko T, Franic T, Vidovic D, De Vriendt N, et al. Effects of cannabis use on age at onset in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;126:270–6. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deng H, Desai PV, Mohite S, Okusaga OO, Zhang XY, Nielsen DA, et al. Hospital stay in synthetic cannabinoid users with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorders compared with cannabis users. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:230–5. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2019.80.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denissoff A, Mustonen A, Alakokkare AE, Scott JG, Sami MB, Miettunen J, et al. Is early exposure to cannabis associated with bipolar disorder?Results from a Finnish birth cohort study. Addiction. 2022;117:2264–72. doi: 10.1111/add.15881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Etyemez S, Currie TT, Hamilton JE, Weaver MF, Findley JC, Soares J, et al. Cannabis use: A co-existing condition in first-episode bipolar mania patients. J Affect Disord. 2020;263:289–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feingold D, Weiser M, Rehm J, Lev-Ran S. The association between cannabis use and mood disorders: A longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:211–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henquet C, Krabbendam L, de Graaf R, ten Have M, van Os J. Cannabis use and expression of mania in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2006;95:103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson JM, Wu CY, Winder GS, Casher MI, Marshall VD, Bostwick JR. The effects of cannabis on inpatient agitation, aggression, and length of stay. J Dual Diagn. 2016;12:244–51. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2016.1245457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katz G, Kunyvsky Y, Hornik-Lurie T, Raskin S, Abramowitz MZ. Cannabis and alcohol abuse among first psychotic episode inpatients. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2016;53:10–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kvitland LR, Melle I, Aminoff SR, Lagerberg TV, Andreassen OA, Ringen PA. Cannabis use in first-treatment bipolar I disorder: Relations to clinical characteristics. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10:36–44. doi: 10.1111/eip.12138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lagerberg TV, Sundet K, Aminoff SR, Berg AO, Ringen PA, Andreassen OA, et al. Excessive cannabis use is associated with earlier age at onset in bipolar disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lagerberg TV, Icick R, Andreassen OA, Ringen PA, Etain B, Aas M, et al. Cannabis use disorder is associated with greater illness severity in tobacco smoking patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:286–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marwaha S, Winsper C, Bebbington P, Smith D. Cannabis use and hypomania in young people: A prospective analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:1267–74. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lev-Ran S, Le Foll B, McKenzie K, George TP, Rehm J. Bipolar disorder and co-occurring cannabis use disorders: Characteristics, co-morbidities and clinical correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209:459–65. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soler S, Montout C, Pepin B, Abbar M, Mura T, Lopez-Castroman J. Impact of cannabis use on outcomes of patients admitted to an involuntary psychiatric unit: A retrospective cohort study. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;138:507–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stone JM, Fisher HL, Major B, Chisholm B, Woolley J, Lawrence J, et al. Cannabis use and first-episode psychosis: Relationship with manic and psychotic symptoms, and with age at presentation. Psychol Med. 2014;44:499–506. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taub S, Feingold D, Rehm J, Lev-Ran S. Patterns of cannabis use and clinical correlates among individuals with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;80:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinstock LM, Gaudiano BA, Wenze SJ, Epstein-Lubow G, Miller IW. Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with comorbid cannabis use disorders (CUDs) in hospitalized patients with bipolar I disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;65:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zorrilla I, Aguado J, Haro JM, Barbeito S, LópezZurbano S, Ortiz A, et al. Cannabis and bipolar disorder: Does quitting cannabis use during manic/mixed episode improve clinical/functional outcomes? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131:100–10. doi: 10.1111/acps.12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tijssen MJ, Van Os J, Wittchen HU, Lieb R, Beesdo K, Wichers M. Risk factors predicting onset and persistence of subthreshold expression of bipolar psychopathology among youth from the community. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122:255–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [[Last accessed 10 Jan 2023]]. Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org .

- 46.Cassidy F, Ahearn EP, Carroll BJ. Substance abuse in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:181–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grinspoon L, Bakalar JB. The use of cannabis as a mood stabilizer in bipolar disorder: Anecdotal evidence and the need for clinical research. J Psychoact Drugs. 1998;30:171–7. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Susser E, Galea S. In memoriam: Mervyn Susser, MB, BCh, DPH. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180:961–3. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Souza DC, Sewell RA, Ranganathan M. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol effects in schizophrenia: Implications for cognition, psychosis, and addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:594–608. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ashton CH, Moore PB, Gallagher P, Young AH. Cannabinoids in bipolar affective disorder: A review and discussion of their therapeutic potential. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19:293–300. doi: 10.1177/0269881105051541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pijlman FT, Rigter SM, Hoek J, Goldschmidt HM, Niesink RJ. Strong increase in total delta-THC in cannabis preparations sold in Dutch coffee shops. Addict Biol. 2005;10:171–80. doi: 10.1080/13556210500123217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.ElSohly MA, Wachtel SR, De Wit H. Cannabis versus THC: Response to Russo and McPartland. Psychopharmacology. 2003;165:433–4. [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: Evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39:179–95. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Regeer EJ, Krabbendam L, de Graaf R, ten Have M, Nolen WA, van Os J. A prospective study of the transition rates of subthreshold (hypo) mania and depression in the general population. Psychol Med. 2006;36:619–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levin FR, Hennessy G. Bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:738–48. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strakowski SM, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, West SA. The effects of antecedent substance abuse on the development of first-episode psychotic mania. J Psychiatr Res. 1996;30:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(95)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacQueen GM, Marriott M, Begin H, Robb J, Joffe RT, Young LT. Subsyndromal symptoms assessed in longitudinal, prospective follow-up of a cohort of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:349–55. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]