ABSTRACT

Background:

The coronavirus anxiety scale (CAS) was developed and validated in 2020 as a psychometrically suitable measure of anxiety incurred by the coronavirus disease of 2019 pandemic. Since it is available only in the English language, it cannot be used in the general population, most of whom are not English speaking.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to determine the validity and the reliability of the Marathi adaptation of CAS.

Materials and Method:

CAS was translated by bilingual experts, followed by forward and backward translation processes and pilot study. Final version was used. Eighty volunteers, who are versed in both English and Marathi languages, were included. The original English version of the scale was first applied, followed by the Marathi translation, after a hiatus of 14 days.

Result:

Mean score of the original English version was 2.950 (±2.773) and that of the Marathi version was 2.775 (±2.778), showing significant correlation (.001 level) with Kendall’s tau-b of 0.830. The Marathi version of CAS has a high degree of internal consistency as demonstrated by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.809. The scale has significant concurrent validity and acceptable split-half reliability. A principal components analysis with varimax rotation was performed on the CAS responses of the participants, which yielded one factors with an eigenvalue greater than one, representing 58.51% of the total variance. CAS was found to be easily understandable and capable of adequately evaluating and measuring various aspects of corona anxiety.

Conclusion:

The Marathi adaptation of CAS is a valid and reliable instrument to assess anxiety due to coronavirus in the Marathi-speaking population of India.

Keywords: Coronavirus anxiety scale, reliability, validity

INTRODUCTION

The “Novel Corona Virus Disease 2019” or commonly known as COVID-19 virus hit the world in 2019 and the outbreak was declared as a global pandemic by the World Health Organization. This left us with far devastating effects with respect to health, both physically as well as psychologically as the world came to a standstill and went into a complete lockdown.[1,2]

As a result of this, the Government of India too announced a nationwide lockdown and every establishment was shut down including industries, educational institutions, offices, restaurants, and so on and even intrastate travel was banned. The foremost primary safety measure to contain the virus required “social distancing” by refraining from doing what is inherently human which seeks the company of friends and significant others in times of distress. The pandemic and the subsequent prolonged national lockdown had a profound effect on the lives of the common man. It also affected their mental health resulting in feelings of stress, helplessness, anxiety, depression, insomnia, fear, phobias, and cyberchondria. There was large-scale closure of small- and medium-scale industries leading to massive migration of laborers and their families. A large number of India’s population were adversely affected by isolation, loneliness, uncertainty, stigma, loss of jobs and income, and loss of their loved ones.[3-5]

India, with its already existing stigma of addressing mental health issues and a massive population of 1.39 billion, assessing the levels of anxiety among individuals because of its widespread nature becomes difficult.[6] In addition to that, all the data and survey available of these studies used English version of the scale with English-speaking participants, who form a miniscule part of the population. Thus, the present research focused on the question whether previous findings pertaining to the reliability and validity can be generalized to participants for whom English is a second language and sometimes a third language in the state of Maharashtra. The purpose of this research was to translate the original coronavirus anxiety scale (CAS) into Marathi language and obtain reliability and validity for further use in clinical and nonclinical population. This study describes the Marathi adaptation and standardization of the CAS. It was conducted in order to meet the need of assessment tool measuring anxiety amongst a large population of Maharashtra, whose known language is Marathi.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

This study was conducted under the Karve Institute of Social Services, Pune. The proposal of the study was approved by the institutional ethical committee, and all participants gave written, informed consent. The study followed the stipulations of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All the participants were explained the purpose of the study, they were informed of their rights as participants in the study and the responsibilities of the research team and were provided with the contact details of the principal investigator and written informed consent was obtained.

For preparing the Marathi version of the CAS, standard guidelines for the translation of scales were followed. First, one content expert who was familiar with COVID-19 and fluent in English and Marathi and one language expert who was more familiar with Marathi language translated the CAS from English to Marathi. Then, another set of content and language experts, respectively, who were blind to the original translation, backtranslated the Marathi version into English. The two versions were compared, and after removing inconsistencies, a revised version was produced. The revised Marathi version was then pilot-tested in 20 Marathi-speaking individuals. The Marathi version was finalized only after further inconsistencies with the original English version were corrected.

Sample

The selection of participants was based on convenience sampling online using snowball methods and the requirement was comprehension of both English and Marathi languages. Selected participants who were staying at Pune were formally educated in English and had also studied Marathi.

Tools

Sociodemographic questionnaire

This questionnaire was used to record the age, gender, education, occupation, place of residence, and marital status.

Coronavirus anxiety scale

The CAS is a brief mental health screener to identify dysfunctional anxiety associated with the COVID-19 crisis. It is an efficient and valid tool for clinical research and practice. The CAS discriminates well between persons with and without dysfunctional anxiety using an optimized cut score of ≥9 (90% sensitivity and 85% specificity).[7,8]

METHODS

The data were collected via Google Forms with incorporated consent forms, sociodemographic questionnaires, and the corona anxiety scale, since face-to-face data collection was not possible due to COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. The participants were asked to complete the original English version of the corona anxiety scale; following completion of English version after 2 weeks, the Marathi version of the scale was administered to the same group of participants. For the purpose of data collection, separate Google Forms were created. Links to the Google Forms were sent out to the participants via e-mail, WhatsApp, and LinkedIn.

Statistical analysis

Classical test theory (CTT) was utilized to assess the reliability and validity of the CAS. Further, validity and reliability tests were divided into scale level and item level. For the scale level, the CCT’s methods employed were internal consistency measure using Cronbach’s alpha, McDonald’s omega, greatest lower bound, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability, standard error of measurement, and concurrent validity (CAS Marathi scale vs. CAS English scale). Item–item correlation and item–total correlation were the item level CTTs. SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Atlanta, USA) was used to assess the CTT. Calculation of McDonald’s omega and the greatest lower bound were done using JASP software (University of Amsterdam, Netherlands).

RESULTS

Sample size was 80. The participants of the study were bilingual and residents of the city of Pune in Maharashtra comprising 44 females and 36 males. Participants of the study came from diverse educational backgrounds including lawyers, postdoctoral scientist, scientific data analyst, teacher, architects, graphic designers, and so on. Mean (±SD) age of the subjects was 32.01 (±12.88) years. Range of age was from 18 to 62 years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample

| Background | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age distribution | 25 years and below | 31 | 38.75% |

| More than 25 years old | 49 | 61.25% | |

| Gender | Male | 36 | 45% |

| Female | 44 | 55% | |

| Education level | High school | 3 | 3.75% |

| Diploma | 3 | 3.75% | |

| Bachelor degree | 46 | 57.5% | |

| Master degree | 26 | 32.5% | |

| Doctoral degree | 2 | 2.5% | |

| Occupation | Student | 6 | 7.50% |

| Lawyer | 6 | 7.50% | |

| IT professionals | 11 | 13.75% | |

| Doctor | 17 | 21.25% | |

| Self-employed | 15 | 18.75 | |

| Service | 23 | 28.75 | |

| Retired | 2 | 2.50% |

Mean (±SD) score of the English and Marathi version was 2.950 (±2.773) and 2.775 (±2.778), respectively. The difference between the scores was not significant (Mann–Whitney U = 766.00; P =0.740; not significant) [Table 2]. The scores on English and Marathi versions were significantly correlated. Kendall’s tau-b was. 830. Thus, the correlation was significant at the. 001 level (two-tailed) [Table 3]. Skewness and kurtosis for all five items on the Marathi CAS scale were acceptable as in the range of −1.031 to 2.052 and −0.374 to 3.715, respectively. The Marathi version had a Cronbach’s alpha of. 809. Split-half (odd-even) correlation was. 552. Spearman–Brown coefficient equal length was. 711 and unequal length was. 718. Guttman split-half coefficient was. 696. Guttman’s Lambda2 was. 819, which were all within acceptable limits [Tables 4-6].

Table 2.

Scores on the Marathi and English versions of the Coronavirus anxiety scale

| Total M | Total E | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 2.775 | 2.950 |

| Median | 2.000 | 2.000 |

| Std. deviation | 2.778 | 2.773 |

| Variance | 7.721 | 7.694 |

| Skewness | 1.255 | 1.053 |

| Kurtosis | 1.422 | 1.137 |

| Minimum | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Maximum | 12.00 | 12.00 |

| Percentiles | ||

| 25 | 1.0000 | 0.2500 |

| 50 | 2.0000 | 2.0000 |

| 75 | 4.0000 | 4.7500 |

Table 3.

Correlation of total scores on scores on English and Marathi version of coronavirus anxiety scale

| English total | Marathi total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kendall’s tau-b | English total | Correlation coefficient | 1.000 | 0.830* |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | . | 0.000 | ||

| Marathi total | Correlation coefficient | 0.830* | 1.000 | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.000 | |||

*Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed)

Table 4.

Marathi version of coronavirus anxiety scale: item-total statistics

| Mean | Std. deviation | Scale mean if item deleted | Scale variance if item deleted | Corrected item – total correlation | Squared multiple correlation | Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 0.475 | 0.7506 | 2.325 | 5.610 | 0.459 | 0.237 | 0.812 |

| M2 | 0.600 | 0.7442 | 2.200 | 4.933 | 0.701 | 0.591 | 0.738 |

| M3 | 0.925 | 0.7970 | 1.875 | 5.548 | 0.432 | 0.233 | 0.824 |

| M4 | 0.375 | 0.7403 | 2.425 | 4.815 | 0.752 | 0.877 | 0.722 |

| M5 | 0.425 | 0.6751 | 2.375 | 5.266 | 0.672 | 0.833 | 0.751 |

Table 6.

Psychometric properties for the Marathi version of the coronavirus anxiety scale at the scale level (n=80)

| Psychometric measure | Result | Suggested cut-off |

|---|---|---|

| Internal consistency measure using Cronbach’s alpha | 0.813 | >0.7 |

| Internal consistency measure using McDonald’s omega | 0.820 | >0.7 |

| Internal consistency measure using Greatest lower bound | 0.880 | >0.7 |

| Average variance extracted (AVE) | 0.585 | >0.5 |

| Composite reliability | 0.872 | >0.7 |

| Standard error of measurement | 0.99 | <1.398 |

Table 5.

Item correlation matrix of the coronavirus anxiety scale (Kendall’s tau-b)

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | |||||

| Correlation coefficient | 1.000 | 0.427** | 0.215 | 0.395** | 0.355* |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.004 | 0.139 | 0.008 | 0.017 | |

| M2 | |||||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.427** | 1.000 | 0.391** | 0.617** | 0.454** |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.002 | |

| M3 | |||||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.215 | 0.391** | 1.000 | 0.293* | 0.305* |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.139 | 0.007 | 0.045 | 0.037 | |

| M4 | |||||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.395** | 0.617** | 0.293* | 1.000 | 0.860** |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.045 | 0.000 | |

| M5 | |||||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.355* | 0.454** | 0.305* | 0.860** | 1.000 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.017 | 0.002 | 0.037 | 0.000 |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed). **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed)

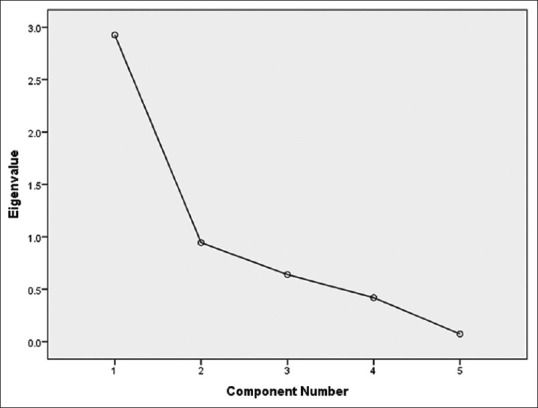

To examine the factor structure of the CAS, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed. Sampling adequacy assessed by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure was. 656. Bartlett’s test of sphericity: approximate χ2 was 106.910 which was significant. The method used was principal component analysis with varimax rotation. The factor analysis yielded one factor with an eigenvalue greater than one, representing 58.51% of the total variance [Tables 7-9 and Figure 1].

Table 7.

Factor analysis of Marathi version of coronavirus anxiety scale: communalities

| Initial | Extraction | |

|---|---|---|

| M1 | 1.000 | 0.362 |

| M2 | 1.000 | 0.697 |

| M3 | 1.000 | 0.329 |

| M4 | 1.000 | 0.821 |

| M5 | 1.000 | 0.717 |

Extraction method: principal component analysis

Table 9.

Factor analysis of Marathi version of coronavirus anxiety scale: component matrixa

| Component 1 |

|

|---|---|

| M4 | 0.906 |

| M5 | 0.847 |

| M2 | 0.835 |

| M1 | 0.601 |

| M3 | 0.574 |

Extraction method: principal component analysis. aOne component extracted

Figure 1.

Scree plot

Table 8.

Factor analysis of Marathi version of coronavirus anxiety scale: total variance explained

| Component | Initial eigenvalues | Extraction sums of squared loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total | % of variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 2.926 | 58.513 | 58.513 | 2.926 | 58.513 | 58.513 |

| 2 | 0.944 | 18.878 | 77.391 | |||

| 3 | 0.639 | 12.786 | 90.177 | |||

| 4 | 0.419 | 8.377 | 98.554 | |||

| 5 | 0.072 | 1.446 | 100.000 | |||

Extraction method: principal component analysis

CAS was found to be easily understandable and capable of adequately evaluating and measuring various aspects of corona anxiety. On Cronbach’s alpha analysis, a high degree of internal consistency was demonstrated. The scale had significant concurrent validity and acceptable split-half reliability.

DISCUSSION

While the COVID-19 pandemic is causing disease and death all over the world, fortunately not everyone is affected. Experience tells us that the majority of infected individuals remain asymptomatic. However, the unrelenting media-hype constantly highlighting the adverse effects has resulted in far greater number of people developing psychiatric symptoms. The CAS is probably the first documented psychopathology-related scale for COVID-19 anxiety that was validated on a large sample of adults in USA reporting severe anxiety in the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic. Since the majority of people in Maharashtra are not able to read English, the original version is of limited use in Maharashtra. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to adapt the CAS in the Marathi language to assess dysfunctional COVID-19 anxiety among Marathi-speaking people. For evaluation of the Marathi version of the CAS, we collected data via an online survey using Google Forms. Thereafter, item and scale level psychometric properties were assessed from the collected data.

Results of the study clearly demonstrate that the items of the CAS Marathi version had high item discrimination (item total correlations). A good item–total correlation indicates that the corresponding item can discriminate between high and low scorers in the test. The high item–total correlation of all the items suggested that the items of the CAS Marathi version differentiate between low and high scorer, which is a strong psychometric feature of this instrument. Results regarding reliability of the Marathi version of CAS indicate that the scale had good internal consistency reliability, test–retest reliability, and composite reliability (≥0.7). The original and a replication study[7,8] had reported high internal consistency reliability for the CAS (Cronbach’s α ranged between. 92 and. 93), which is in agreement with our findings.

While there are no clear cut-off values for poor and good reliabilities it has been suggested that values of. 70 to. 80 are acceptable.[9] Others, however, have suggested. 80 or higher values of reliability for screening scales.[10,11] As the internal consistency reliabilities and composite reliability of the Marathi version of the CAS were both found to be >.80, we can conclude that this scale is suitable for screening COVID-19 anxiety among Marathi-speaking people. The EFA supported the single-factor model suggested by the initial studies.[7,8]

Limitations

The study sample was confined to a highly educated, urban population knowing English and Marathi. Moreover, data were collected from a nonclinical sample. A clinical sample should be used to further validate the data. Lastly, since data were collected through online self-reported survey, respondents may have been subjected to social desirability bias. This may have been circumvented by data being collected anonymously.

CONCLUSION

The Marathi-translated version of CAS is valid and reliable for use in the literate Marathi-speaking population.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Srivastava K, Chaudhry S, Sowmya AV, Prakash J. Mental health aspects of pandemics with special reference to COVID-19. Ind Psychiatry J. 2020;29:1–8. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_64_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhamija S, Samudra M, Davis S, Gupta N, Chaudhury S. COVID-19 lockdown –Blessing or disaster? Ind Psychiatry J. 2021;30((Suppl S1)):294–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.328834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chag J, Chaudhury S, Saldanha D. Economic and psychological impact of COVID 19 lockdown: Strategies to combat the crisis. Ind Psychiatry J. 2020;29:362–8. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_120_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis S, Samudra M, Dhamija S, Chaudhury S, Saldanha D. Stigma associated with COVID19. Ind Psychiatry J. 2021;30((Suppl 1)):S270–2. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.328827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis S, Samudra M, Dhamija S, Chaudhury S, Saldanha D. Quarantine: Psychological aspects. Ind Psychiatry J. 2021;30((Suppl 1)):S277–81. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.328829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Javadekar A, Javadekar S, Chaudhury S, Saldanha D. Depression, anxiety, stress, and sleep disturbances in doctors and general population during COVID19 pandemic. Ind Psychiatry J. 2021;30((Suppl 1)):S20–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.328783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SA. Coronavirus anxiety scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Stud. 2020;44:393–401. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1748481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SA. Replication analysis of the coronavirus anxiety scale. Dusunen Adam. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2020;33:203–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furr RM. Scale Construction and Psychometrics for Social and Personality Psychology. London: Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bardhoshi G, Erford BT. Processes and procedures for estimating score reliability and precision. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2017;50:256–63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erford BT. Assessment for Counselors. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Pearson Education Inc.; 2021. [Google Scholar]