Abstract

Bradyrhizobium japonicum possesses a second fixK-like gene, fixK2, in addition to the previously identified fixK1 gene. The expression of both genes depends in a hierarchical fashion on the low-oxygen-responsive two-component regulatory system FixLJ, whereby FixJ first activates fixK2, whose product then activates fixK1. While the target genes for control by FixK1 are unknown, there is evidence for activation of the fixNOQP, fixGHIS, and rpoN1 genes and some heme biosynthesis and nitrate respiration genes by FixK2. FixK2 also regulates its own structural gene, directly or indirectly, in a negative way.

Rhizobial FixK proteins belong to the large and phylogenetically widespread family of FNR- and CRP (CAP)-like proteins of bacteria (8, 27). First identified in Sinorhizobium (Rhizobium) meliloti (4), FixK has been discovered in all rhizobial species examined, and additional copies or homologs of the corresponding gene exist in certain species (e.g., see references 11 and 21). The FixK proteins are transcriptional regulators that usually function as activators of their target genes. They bind to a conserved, symmetric nucleotide sequence, 5′-TTGA(N6)TCAA-3′ (the FixK box [8, 28]), whose axis of symmetry is located between positions −41 and −40 upstream of the transcriptional start site of the regulated genes. FixK in S. meliloti is part of a regulatory cascade in which the membrane-bound hemoprotein FixL senses a low oxygen concentration, phosphorylates itself, and then transfers the phosphate moiety to the response regulator FixJ, which finally activates the expression of fixK (3). The FixK protein then activates a number of genes or operons, including the fixNOQP and fixGHIS operons, which are responsible for the synthesis of a high-affinity terminal oxidase for respiration under microaerobic conditions, such as in legume root nodules (3, 12). FixK negatively regulates its own expression in S. meliloti by activating the fixT gene, whose product inhibits the FixLJ system (10).

The mechanisms by which fixK genes are regulated and the nature and number of genes controlled by FixK differ by various extents in different rhizobial species (8). For reasons of space restrictions, these differences are not discussed in this article. A particularly puzzling case has been described previously for the nitrogen-fixing soybean symbiont Bradyrhizobium japonicum (1, 2). This species possesses a FixLJ-dependent fixK gene (here called fixK1) which, when mutated, does not cause the negative nitrogen fixation (Fix) and anaerobic nitrate respiration (NR) phenotypes that are characteristic for B. japonicum fixLJ mutants. Constitutive overexpression of fixK1 in a fixJ mutant background, thus bypassing the FixJ dependency, partially restored NR activity (2) and completely restored Fix activity (18). It thus appeared as if the FixK1 protein could substitute for a FixLJ-dependent function. One interpretation of this result was that, in the wild-type B. japonicum, FixLJ might regulate a second fixK-like gene whose product would be the real activator for some nitrogen fixation and nitrate respiration genes and which would also activate fixK1, a gene that itself is not involved in these activities. This would explain why constitutive fixK1 expression could compensate for the lack of expression of such a second fixK-like gene in a fixJ mutant. We report here that these assumptions turned out to be correct.

Identification, sequencing, and mutational analysis of a second B. japonicum fixK-like gene, fixK2.

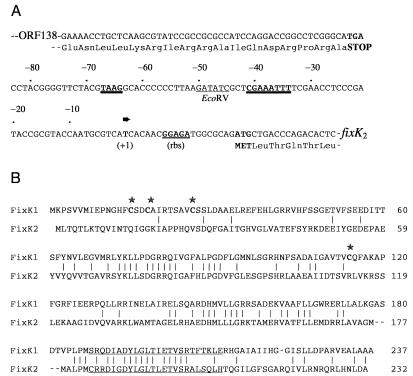

Using either B. japonicum fixK1 or S. meliloti fixK DNA fragments as probes, a second fixK-like gene (here called fixK2) was discovered in Southern blot hybridizations to previously isolated DNA clones of the B. japonicum fixLJ-open reading frame 138 (ORF138) region (1). Thus, fixK2 was identified as part of the so-called fix cluster III (8) (Fig. 1A). The gene was sequenced on both DNA strands. The putative fixK2 start codon was located 104 bp downstream of the ORF138 stop codon (Fig. 2A), and the fixK2 ORF had a length of 696 bp and encoded a protein of 232 amino acids. The positional amino acid sequence identity between the deduced FixK2 and FixK1 proteins (Fig. 2B) is 34%. This identity is less than that between FixK2 and the FixK proteins of Azorhizobium caulinodans (44% [14]) and S. meliloti (40% [4]), therefore suggesting a function for FixK2 that is distinguishable from the function of FixK1. The difference between FixK2 and FixK1 is further emphasized by the fact that not only the cysteine-rich domain present at the FixK1 N terminus but also cysteine 114, both rendering this type of protein oxygen sensitive (2, 15, 27), is missing in FixK2 (Fig. 2B). Each of these proteins contains near its C terminus a helix-turn-helix motif potentially involved in DNA binding (Fig. 2B).

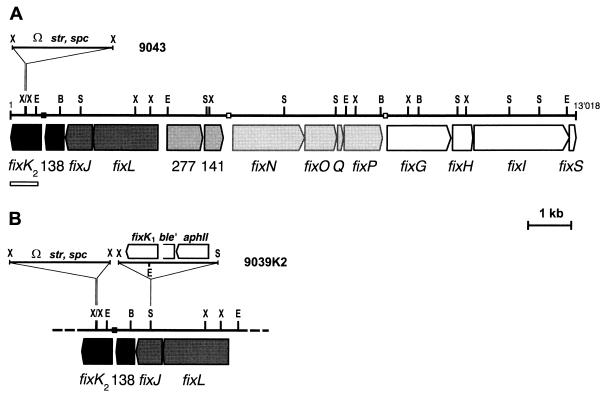

FIG. 1.

B. japonicum fixK2 gene and fixK2 mutations. (A) Map of fix gene cluster III showing the fixK2 locus at the left end. The insertion in mutant 9043 containing the streptomycin-spectinomycin resistance gene (Ω str, spc) is marked. The FixJ box in front of fixK2 is symbolized with a closed square, and the FixK boxes in front of the fixNOQP and fixGHIS operons are marked with open squares. The combined 13,018-bp DNA sequence of the entire cluster III, including the newly sequenced fixK2 region (open bar), was deposited in the EMBL/GenBank database under accession no. AJ005001. (B) Genomic structure of strain 9039K2, which carries the same fixK2 mutation as strain 9043 plus an insertion in fixJ. This inserted fragment carries fixK1 transcriptionally fused to the bleomycin resistance gene of the Tn5-derived aphII-ble-str operon. Constitutive expression of the fixK1 gene is thus controlled by the promoter of the kanamycin resistance gene aphII. B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; S, SalI; X, XhoI.

FIG. 2.

Sequence analyses. (A) Nucleotide sequence of ORF138-fixK2 intergenic region showing the putative ribosome binding site sequence (rbs), the transcription start site (indicated by the arrow at position +1), and the conserved FixJ binding site motifs at positions −35 and −65 (indicated by boldfaced underlining). The EcoRV site used to construct deletion clone pRJ9053 (see the text) is designated. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of the FixK1 and FixK2 proteins. Identical amino acids are connected by vertical lines. The stars denote the essential cysteines characteristic for the oxygen-responsive FNR protein class. The probable DNA binding domain (helix-turn-helix motif) is underlined.

A deletion-insertion mutation was created by cloning a 2.3-kb Ω cassette (with attached XhoI linkers) from pHP45Ω (26) between two closely adjacent XhoI sites in the center of the fixK2 gene (Fig. 1A). The mutation was transferred to the B. japonicum wild-type strain 110spc4 and the fixK1 mutant 7453 (2) by marker replacement. The resulting streptomycin-resistant fixK2::Ω mutant and the fixK1-fixK2 double mutant were designated strains 9043 and 9043K1, respectively. Both strains were unable to fix nitrogen in root nodule symbiosis with soybean (they exhibited <1% of wild-type Fix activity) and did not grow anaerobically with nitrate as the terminal electron acceptor (data not shown). These phenotypes were the same as those of fixLJ mutants (1) but differed completely from the Fix- and NR-positive phenotypes of the fixK1 mutant (2).

The fixK2 gene is regulated positively by FixLJ and negatively by its own product.

A translational fusion of lacZ was constructed within the 43rd fixK2 codon (at an EcoRI site [Fig. 1A]) and integrated at the chromosomal fixK2 locus of the B. japonicum wild type and the fixJ, fixK1, and fixK2 mutants. For this purpose, the fusion was first constructed in vector pNM480B and then transferred into pSUP202 for cointegration into the chromosome (18). β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) activity expressed from the reporter fusion was determined in cells grown aerobically or microaerobically as described previously (1, 2). Table 1 shows that fixK2 expression is induced about 10-fold in microaerobically grown cells compared with aerobically grown cells and that this induction requires FixJ but not FixK1. A very strong induction (60-fold) in the fixK2 mutant suggests that FixK2 negatively regulates expression of its own structural gene in the wild type. Whether this autoregulation is direct or indirect, e.g., via activation of a repressor gene, is not known. In this context, it is of interest that ORF138 (Fig. 1), a gene for a FixJ homolog lacking the C-terminal DNA-binding domain (1), is induced (sixfold) under microaerobic growth conditions and that this induction partly depends on FixK2 but not FixJ (18). More work is needed to explore the possibility that the ORF138 protein is a player in the negative autoregulatory circuitry involving FixK2.

TABLE 1.

Expression of chromosomally integrated lacZ fusions in B. japonicum wild-type and mutant backgrounds

| Strain | lacZ fusion | Disrupted gene | β-Gal activitya (Miller units) in cells grown

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobically | Microaerobically | |||

| 9054 | fixK2′-′lacZ | None (wild type) | 32 | 348 |

| 9054J | fixK2′-′lacZ | fixJ | 25 | 75 |

| 9054K1 | fixK2′-′lacZ | fixK1 | 35 | 273 |

| 9054K2 | fixK2′-′lacZ | fixK2 | 55 | 3,420 |

| 9036 | fixK1′-′lacZ | None (wild type) | 7 | 54 |

| 9036J | fixK1′-′lacZ | fixJ | 4 | 6 |

| 9036K1 | fixK1′-′lacZ | fixK1 | 4 | 50 |

| 9036K2 | fixK1′-′lacZ | fixK2 | 3 | 7 |

| 8003 | rpoN′-′lacZ | None (wild type) | 7 | 66 |

| 8003J | rpoN′-′lacZ | fixJ | 4 | 10 |

| 8003K1 | rpoN′-′lacZ | fixK1 | 7 | 60 |

| 8003K2 | rpoN′-′lacZ | fixK2 | 6 | 6 |

| 3604 | fixP′-lacZ | None (wild type) | 3 | 141 |

| 3605 | fixP′-′lacZ | fixJ | 4 | 4 |

All experiments were repeated at least once for confirmation; the standard deviations ranged between 0 and 38%. β-Gal assays were performed as described by Miller (17).

The transcription start site of fixK2 was determined by primer extension experiments in microaerobically grown cells of strain 9054 containing the chromosomally integrated fixK2′-′lacZ fusion, using fixK2- and lacZ-specific oligonucleotides (3′-GGGTCTGTGAGTTCTGGGTCCACTAGTTGTGGG-5′and 3′-GCAATGGGTTGAATTAGCGGAACGTCGTGTAGG-5′, respectively) as primers. Both primers produced extension products terminating at the T marked by an arrow in Fig. 2A (position +1). The extension products were weak in a fixJ mutant but very strong in a fixK2 mutant (results not shown), which is consistent with the lacZ expression data of Table 1. There are two conserved nucleotide sequence elements, at the −65 and −35 regions (Fig. 2A), that are also present in other rhizobial FixJ-dependent promoter regions (28). We tested plasmid-encoded fixK2′-′lacZ fusions in the microaerobically grown wild type for the relevance of the conserved regions. A plasmid (pRJ9051) containing upstream DNA up to a BamHI site within ORF138 (Fig. 1A) produced 454 U of β-Gal activity, whereas a deletion clone (pRJ9053), in which DNA upstream of the EcoRV site at position −47 was removed (Fig. 2A), produced only 34 U. Taken together, all of the data described in this section support the notion that FixJ is the direct activator of fixK2.

FixK2 activates the fixK1 gene.

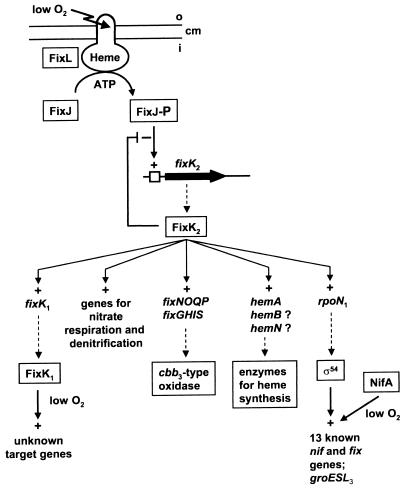

A previously constructed translational fixK1′-′lacZ fusion (2) was integrated into the chromosomes of the B. japonicum wild type and the fixJ, fixK1 and fixK2 mutants at the fixK1 locus for measurements of β-Gal activity in aerobically and microaerobically grown cells (Table 1). Appreciable β-Gal activity was produced only in microaerobically grown cultures of the wild type and the fixK1 mutant, whereas there was background activity in the fixJ and fixK2 mutants. The FixLJ dependency of fixK1 expression has already been shown previously (2); however, this effect must have been indirect, since in the present study we demonstrated an involvement of the FixJ-dependent fixK2 gene in this control. In fact, a perfect FixK box (5′-TTGATCTGGGTCAA-3′), present at a proper distance (between positions −41 and −40, at the axis of symmetry) from the transcription start site of fixK1 (2, 18), might serve as the binding site for FixK2. To support this idea, we tested plasmid-encoded fixK1′-′lacZ fusions in microaerobically grown wild-type cells. A plasmid (pRJ9025) with 96 bp of DNA present upstream of the transcription start site (up to a BamHI site [2]) produced 58 U of β-Gal activity, whereas a deletion clone (pRJ9056) with its 5′ deletion end point at position −33 produced only 1 U of β-Gal activity. This corroborates that the conserved FixK box is an important part of the fixK1 promoter region. All lines of available evidence now suggest the existence of a regulatory cascade in which FixJ first activates the fixK2 gene, whose product is then the activator of the fixK1 gene (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

The crucial position of B. japonicum FixK2 as a distributor of the low-oxygen-level signal transduced through FixLJ. See the text for further explanations. Abbreviations and symbols: cm, cytoplasmic membrane; i, inside; o, outside; P, phosphate moiety; +, positive control; −, negative control; □, FixJ box.

We reasoned that if the two fixK genes were epistatic, constitutively expressed fixK1 might compensate for a lack of fixK2. To test this idea, strain 9039K2 (Fig. 1B), which carries the fixK2 mutation and a fixK1 gene transcribed from the aphII gene promoter, was constructed. The paphII::fixK1 fusion was inserted into fixJ to ensure that any other potential fixJ-dependent function besides that of fixK2 was defective, too. Fix activity in strain 9039K2 was completely restored to wild-type levels. Anaerobic growth with nitrate was also restored; however, exponential growth of 9039K2 was slower than that of the wild type (19 and 13 h doubling times, respectively), which possibly reflects a subtle functional difference between FixK1 and FixK2.

Other FixK2-regulated B. japonicum genes.

In the course of studying symbiotically relevant B. japonicum genes that are induced at a low oxygen tension, we found several that are most likely controlled by the FixLJ-FixK2 system (Fig. 3). The evidence for this inference that has been obtained is discussed below briefly for each individual gene or operon.

(i) rpoN1, one of two ς54 genes.

Having found a FixLJ dependency for rpoN1 expression previously (16), we showed in the present study that this expression was mediated by FixK2 since a chromosomally integrated rpoN1′-′lacZ fusion was not expressed in a fixK2 mutant background (Table 1). A nearly perfect FixK box (5′-TTGCGCGACATCAA-3′ at position −75 relative to the rpoN1 start codon [16]) is present in the region upstream of rpoN1, but unfortunately its precise distance to the transcription start site is not known because, despite repeated attempts, we failed to map it. However, the importance of the FixK box was demonstrated by testing upstream deletion derivatives of a plasmid-borne rpoN1′-′lacZ fusion. A plasmid (pRJ8042) with a 5′ deletion end point in the middle of the FixK box produced only background β-Gal activity (4 U), whereas a clone (pRJ8041) with an additional 21 bp of upstream DNA allowed for full expression (287 U) in microaerobic culture.

(ii) fixNOQP operon, coding for a high-affinity cbb3-type oxidase complex.

A translational lacZ fusion to the sixth codon of fixP, the last gene of the fixNOQP operon (23, 25), was constructed and chromosomally integrated into the B. japonicum wild type and the fixJ mutant. A clear FixJ dependency was found for fixP′-′lacZ expression (Table 1). Although expression in the fixK2 mutant was not tested, regulation by FixK2 is likely in view of the optimal FixK box (5′-TTGATTTCAATCAA-3′) that is present at a perfect distance (between positions −41 and −40, at the axis of symmetry) upstream of the fixN transcription start site (22, 23).

(iii) fixGHIS operon.

These four genes code for a redox-coupled cation transport system (P-type ATPase) that is essential for the biogenesis of the cbb3-type oxidase (13, 24). Therefore, coregulation with the fixNOQP operon would appear sensible. In fact, the fixG transcription start site that was mapped by primer extension (24) is preceded at an appropriate distance by a FixK box (5′-TTGAGCTGGATCAA-3′). No primer extension products were detected in fixJ and fixK2 mutant backgrounds (22).

(iv) Heme biosynthesis genes.

Page and Guerinot (20) reported a FixLJ-dependent microaerobic induction of the δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase gene (hemA) and demonstrated that this induction required a functional FixK box (5′-TTGATCGGGATCAA-3′) at a proper distance from the transcription start site. Likewise, the hemB gene for the next enzyme of the heme biosynthesis pathway, δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase, is induced under conditions of oxygen limitation in a FixJ-dependent manner (6), but evidence for the involvement of FixK2 is not yet available. Recently we cloned a hemN-like gene, coding for a putative coproporphyrinogen III dehydrogenase, and obtained preliminary results suggesting a partial regulation by FixK2 (9). In general, oxygen limitation in B. japonicum triggers an increase in cytochrome synthesis which is accompanied by an increased demand for heme (19).

(v) Nitrate respiration genes.

As shown previously (1) and in this work (see above), B. japonicum fixLJ and fixK2 mutants are defective in anaerobic growth with nitrate as the terminal electron acceptor, suggesting that some critical genes for nitrate reduction or for the entire denitrification pathway are subject to control by the FixLJ-FixK2 cascade. An attractive target gene for further studies is the cycA gene for cytochrome c550, because cycA was also shown to be essential for nitrate respiration (5). Furthermore, B. japonicum DNA sequences for a nitrite reductase gene (nirK) and some genes for N2O respiration (nosZDF) have been deposited in the EMBL database (accession no. AJ002516 and AJ002531); these genes should now be amenable for regulatory studies. The involvement of FixK- or FNR-like regulators in the control of denitrification genes of nonrhizobial denitrifiers is well documented (29).

Concluding remarks.

The existence in bacteria of a gene expression cascade with three transcriptional regulators interconnected in series (FixJ-FixK2-FixK1 or FixJ-FixK2-RpoN1 [Fig. 3]) is quite remarkable. The physiological reason for such complex hierarchies is not fully understood, even though their logic is persuasive. One function of the sophisticated cascade might be to sense oxygen gradients, since not only FixL but also FixK1 is an oxygen sensor. In that case, the threshold level for efficient response of FixK1 ought to be at a lower oxygen concentration than that for FixL, and the autoregulatory FixK2 system would be in an optimal strategic position to fine-tune between these values. Likewise, a gradual lowering of the ambient oxygen concentration would trigger a gradual increase in the synthesis of ς54 (RpoN), which is needed in the extremely oxygen-sensitive NifA-dependent activation of nitrogenase gene expression (8). The FixK2 protein may thus be regarded as a distributor and as an amplifier or silencer of the input signal arriving at FixL (Fig. 3). It makes sense that activation of the genes for the high-affinity cbb3-type oxidase proceeds directly via FixLJ-FixK2, apparently without an additional oxygen-sensitive switch such as FixK1 or NifA, because this gives cells a chance to exploit intermediate to low oxygen concentrations for respiration. The same rationale might apply for the hem genes. Too little is currently known about the complete set of transcription factors needed in the control of B. japonicum denitrification genes. It is intriguing to learn from studies with other denitrifiers that up to three FNR-like proteins may be employed in this process (29).

One final remark concerns the unknown genes regulated by FixK1. The FixK1 protein shares the highest degree of similarity (59% positionally identical amino acids) with the Rhodopseudomonas palustris AadR protein (7), whereas the identity between FixK2 and AadR is only 33%. AadR is an FNR-like transcriptional activator of genes for anaerobic degradation of 4-hydroxybenzoate (7). While this does not necessarily imply an identical function for FixK1, the similarity of AadR to FixK1 raises hopes for the future discovery of a new, anaerobic metabolic pathway that is genetically controlled by FixK1. By then, the fix designation for this gene, which was solely based on the fact that fixK1 belongs to the FixLJ regulon (2), will have to be abandoned.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been submitted to the EMBL/GenBank database and assigned accession no. AJ005001 (see the legend to Fig. 1 for further details).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

During review of this paper, a report (M. C. Durmowicz and R. J. Maier, J. Bacteriol. 180:3253–3256, 1998) appeared that showed a FixK2-dependent regulation of B. japonicum hydrogenase (hup) genes in symbiotic conditions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anthamatten D, Hennecke H. The regulatory status of the fixL- and fixJ-like genes in Bradyrhizobium japonicum may be different from that in Rhizobium meliloti. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;225:38–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00282640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthamatten D, Scherb B, Hennecke H. Characterization of a fixLJ-regulated Bradyrhizobium japonicum gene sharing similarity with the Escherichia coli fnr and Rhizobium meliloti fixK genes. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2111–2120. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2111-2120.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batut J, Boistard P. Oxygen control in Rhizobium. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1994;66:129–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00871636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batut J, Daveran-Mingot M-L, David M, Jacobs J, Garnerone A M, Kahn D. fixK, a gene homologous with fnr and crp from Escherichia coli, regulates nitrogen fixation genes both positively and negatively in Rhizobium meliloti. EMBO J. 1989;8:1279–1286. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bott M, Thöny-Meyer L, Loferer H, Rossbach S, Tully R E, Keister D, Appleby C A, Hennecke H. Bradyrhizobium japonicum cytochrome c550 is required for nitrate respiration but not for symbiotic nitrogen fixation. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2214–2217. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2214-2217.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chauhan S, O’Brian M R. Transcriptional regulation of δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase synthesis by oxygen in Bradyrhizobium japonicum and evidence for developmental control of the hemB gene. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3706–3710. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3706-3710.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dispensa M, Thomas C T, Kim M-K, Perrotta J A, Gibson J, Harwood C S. Anaerobic growth of Rhodopseudomonas palustris on 4-hydroxybenzoate is dependent on AadR, a member of the cyclic AMP receptor protein family of transcriptional regulators. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5803–5813. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5803-5813.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer H-M. Genetic regulation of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:352–386. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.352-386.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer, H. M., S. Schaeren, and D. Zingg. Unpublished data.

- 10.Foussard M, Garnerone A-M, Ni F, Soupène E, Boistard P, Batut J. Negative autoregulation of the Rhizobium meliloti fixK gene is indirect and requires a newly identified regulator, FixT. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:27–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4501814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutiérrez D, Hernando Y, Palacios J-M, Imperial J, Ruiz-Argüeso T. FnrN controls symbiotic nitrogen fixation and hydrogenase activities in Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viciae UPM791. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5264–5270. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5264-5270.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hennecke H. Rhizobial respiration to support symbiotic nitrogen fixation. In: Elmerich C, Kondorosi A, Newton W E, editors. Biological nitrogen fixation for the 21st century. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1997. pp. 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahn D, David M, Domergue O, Daveran M-L, Ghai J, Hirsch P R, Batut J. Rhizobium meliloti fixGHI sequence predicts involvement of a specific cation pump in symbiotic nitrogen fixation. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:929–939. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.929-939.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaminski P A, Mandon K, Arigoni F, Desnoues N, Elmerich C. Regulation of nitrogen fixation in Azorhizobium caulinodans: identification of a fixK-like gene, a positive regulator of nifA. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1983–1991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khoroshilova N, Beinert H, Kiley P J. Association of a polynuclear iron-sulfur center with a mutant FNR protein enhances DNA binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2499–2503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kullik I, Fritsche S, Knobel H, Sanjuan J, Hennecke H, Fischer H-M. Bradyrhizobium japonicum has two differentially regulated, functional homologs of the ς54 gene (rpoN) J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1125–1138. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1125-1138.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nellen-Anthamatten, D., M. Babst, and P. Rossi. Unpublished data.

- 19.O’Brian M R. Heme synthesis in the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis: a palette for bacterial and eukaryotic pigments. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2471–2478. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2471-2478.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page K M, Guerinot M L. Oxygen control of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum hemA gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3979–3984. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3979-3984.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patschkowski T, Schlüter A, Priefer U B. Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae contains a second fnr-fixK-like gene and an unusual fixL homologue. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:267–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6321348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Preisig O. Genetische und biochemische Charakterisierung der für die Bakteroidrespiration essentiellen Häm-Kupfer-Oxidase (cbb3-Typ) von Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Ph.D. dissertation no. 11306. Zürich, Switzerland: Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Preisig O, Anthamatten D, Hennecke H. Genes for a microaerobically induced oxidase complex in Bradyrhizobium japonicum are essential for a nitrogen fixing endosymbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3309–3313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preisig O, Zufferey R, Hennecke H. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum fixGHIS genes are required for the formation of the high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:297–305. doi: 10.1007/s002030050330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preisig O, Zufferey R, Thöny-Meyer L, Appleby C A, Hennecke H. A high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase terminates the symbiosis-specific respiratory chain of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1532–1538. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1532-1538.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prentki P, Krisch H M. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiro S. The FNR family of transcriptional regulators. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1994;66:23–36. doi: 10.1007/BF00871630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waelkens F, Foglia A, Morel J-B, Fourment J, Batut J, Boistard P. Molecular genetic analysis of the Rhizobium meliloti fixK promoter: identification of sequences involved in positive and negative regulation. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1447–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zumft W G. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:533–616. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.533-616.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]