Abstract

Congenital myopathies are an expanding spectrum of neuromuscular disorders with early infantile or childhood onset hypotonia and slowly or nonprogressive skeletal muscle weakness. RYR1 -related myopathies are the most common and frequently diagnosed class of congenital myopathies. Malignant hyperthermia susceptibility and central core disease are autosomal dominant or de novo RYR1 disorder, whereas multiminicore, congenital fiber type disproportion and centronuclear myopathy are autosomal recessive RYR1 disorders. The presence of ptosis, ophthalmoparesis, facial, and proximal muscles weakness, with the presence of dusty cores and multiple internal nuclei on muscle biopsy are clues to the diagnosis. We describe an 18-year-old male, who presented with early infantile onset ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, myopathic facies, hanging lower jaw, and proximal muscle weakness confirmed as an RYR1 -related congenital centronuclear myopathy on genetic analysis and muscle biopsy.

Keywords: myopathy, ophthalmoplegia, centronuclear

Introduction

Congenital myopathies are a heterogeneous group of slowly progressive neuromuscular disorders characterized by the definitive morphologic abnormalities in the skeletal muscles. 1 Core myopathies and RYR1 -related myopathies are the most common histopathologic and genetic subtypes, respectively. We report an 18-year-old male with genetically confirmed RYR1 -related centronuclear myopathy (CNM) with a relatively static course of illness.

Centronuclear myopathies are associated with an abnormally increased frequency of central nuclei in skeletal muscle myofibers. These are classified into three subtypes: X-linked, autosomal recessive, and autosomal dominant types with variable clinical severity from neonatal deaths to adult-onset slowly progressive disease. The X-linked form is also known as myotubular myopathy, the most severe form of CNM with in utero onset. 2 The clinical features of X-linked CNM include severe floppiness of limbs, facial weakness, ptosis, and ophthalmoplegia, difficulties in respiration, feeding with normal cognition. The cardiac muscles are normal. Once they survive to late childhood, muscle biopsies no longer show myotubes but retain central nucleation pattern. 3

The autosomal dominant subtype of CNM has a relatively milder phenotype with later onset, whereas the autosomal recessive subtype is of intermediate severity with onset in infancy or childhood. The clinical features of the autosomal recessive and dominant subtypes are indistinguishable from the X-linked subtype making genetic diagnosis essential, especially in males. 3 4 The cardinal feature of CNM is the presence of central nuclei in more than 25% of muscle fibers in histopathology, with the absence of dystrophic features. There is predominance of type 1 fibers along with atrophy or hypotrophy of type 2 fibers.

Centronuclear myopathy is a genetically heterogeneous disorder. X-linked CNM (OMIM 310400) is associated with MTM1 , Autosomal dominant CNM (OMIM 160150) is associated DNM2 , BIN1 , hJUMPY , CCDC78 , and autosomal recessive CNM (OMIM 255200) is associated with RYR1 , BIN1 , SPEG , and TTN gene variants in the same order. 3 4 5 6 CNM was first reported as myotubular myopathy in 1966 by Spiro et al. 7 The term “myotubular myopathy” was used due to morphological similarities to fetal myotubes. However, this term is used currently only for the X-linked severe infantile form. 7 The “necklace fibers” were found in sporadic late-onset MTM1 -related CNM. These necklace fibers are a ring of increased histochemical oxidative enzyme activity present separately from the sarcolemma. 5 8

Mutation in the RYR1 gene is associated with diverse skeletal muscle phenotype ranging from autosomal dominantly inherited malignant hyperthermia susceptibility (MHS), classical central core disease, and autosomal recessively inherited multiminicore disease and CNM. 8 The RYR1 gene encodes the ryanodine receptor 1 (RyR1), a homotetrameric sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum calcium channel at the skeletal muscle triad. RyR1 plays a crucial role in excitation-contraction coupling through the interaction with the dihydropyridine receptor in the T-tubule. 9 The RYR1 gene comprises of 106 exons and encodes 5,038 amino acids, making it one of the largest genes in the human genome. 10 MHS-related RYR1 mutations are most often located in the hydrophilic N-terminal and central portions of the RyR1 protein, in contrast central core disease-related RYR1 mutations are mainly located at the hydrophobic pore-forming region of the channel. The autosomal recessive RYR1 gene variants are distributed throughout the gene. 11

Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is commonly associated with dominant RYR1 variants (50–60%), whereas the relationship between MH and recessive RYR1 variants is less specific. However, the precautions to prevent MH must be followed in recessive cases also, as the susceptible individuals may not always exhibit symptoms following initial exposure to the triggering agents. 9 12

The recessive RYR1 - related myopathies encompass a heterogenous spectrum of histopathological and clinical subtypes with varying disease severity. The muscle biopsy in patients with recessive RYR1 myopathy shows broad range of features including CNM, multiminicore myopathy, and congenital fiber type disproportion. The recessive RYR1 -related congenital myopathies are usually more severe. 13 The clinical phenotypes of recessive RYR1- related myopathies include early-onset symptoms, motor developmental delay, hypotonia, and proximal weakness with a relatively stable course. Ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, facial, bulbar weakness, diffuse proximal muscle weakness, severe respiratory involvement, club foot, joint contractures, and pectus carinatum or excavatum are other variably present clinical features. All patients either had facial or ocular involvement at evaluation. 8 Atypical presentation of RYR1 include exertional myalgia, exertion induced rhabdomyolysis, rigid spine myopathy, periodic paralysis, and ophthalmoplegia with facial weakness. 13 Lordosis, scoliosis, rigid spine, and scapular winging are reported. Serum creatine kinase levels are normal or mildly elevated, and skeletal muscle biopsy shows characteristic structural abnormalities with the prominence of centralized nuclei in a large number of muscle fibers, type 1 fibers predominance, rarely necklace-fibers and radiating sarcoplasmic strands are also seen. 8

With the advent of next-generation sequencing techniques, there has been recent increase in the number of novel recessive variants identification, which makes the genotype–phenotype correlation more challenging. The dominant RYR1 mutations in MHS are present in the N-terminal, C terminal, and central domain and leads to hyperexcitability; in central core disease (CCD), the RYR1 variants are present in the C terminal and are associated with chronic channel dysfunction. The genotype–phenotype correlation of recessive RYR1 -associated disorder is less well understood. 8 14

The presence of null variants such as frameshift, nonsense, canonical ± 1or 2 splice-site variants, and single or multiple exon deletions are predicted to abolish or markedly reduce RYR1 protein leading to severe clinical presentation in recessive cases. 6 9 While hypomorphic variants, including the missense and small in-frame indels (insertions/deletions), would likely result in approximately full-length, but functionally abnormal RYR1 protein are reported with milder clinical phenotype. 15 Neto et al in a multicentric study reported 18 families with recessive RYR1 CNM. All these families' harbored compound heterozygous variants in the RYR1 gene, 16 families had compound heterozygous truncating variant (frameshift, stop gain, or splice site disrupting) in addition to a missense variant, and in two families missense variants affected the primary splice site. 8

The particular pattern of involvement in the muscle magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful in diagnosing certain congenital myopathies. 14 The findings such as the presence of diffuse involvement of quadriceps with relative sparing of rectus femoris and gracilis in comparison to vastus intermedius and sartorius respectively at the thigh muscles, and relative sparing of gastrocnemii and tibialis posterior in comparison to soleus and anterior compartment muscles respectively in the calf muscles, can guide to screen for RYR1 variants in the patients with CNM. 14

There are no approved therapies for RYR1 -related myopathies, but yet many drugs are in the investigational stage. As the RYR1 gene is large and exceeds the packaging capacity of adenovirus-mediated therapy, hence gene therapy is currently not feasible. 16 However, certain nongenetic medications have been used such as dantrolene, salbutamol, and N-acetylcysteine. Dantrolene is a muscle relaxant and is the only medical treatment approved for the management of malignant hyperthermia. Salbutamol is a β-2 adrenergic agonist and helps to build muscle volume and strength. N-acetyl cysteine helps to reduce oxidative stress, which is the hallmark pathologic feature of RYR1 -related myopathies. 17 18

Case Presentation

An 18-year-old male presented with complaints of drooping of the eyelids, unclear speech, and inability to close his mouth, noted since childhood. He was fourth born to a nonconsanguineous married couple with a significant family history of death of two siblings: one male and one female in the infantile age. Both the siblings had history of reduced spontaneous activity and died with respiratory distress in first month of life. He was born as a term with normal vaginal delivery, birth weight was 3 kg, and had an uncomplicated perinatal period. There was a history of reduced fetal movements during the antenatal period. He was floppy since birth and motor milestones were markedly delayed. Parents noticed drooping of both eyelids and the inability to close the eyes during sleep since first year of life. He developed left eye keratitis at 6 years of age and required enucleation because of anterior staphyloma and ophthalmitis. He had difficulty in chewing and had unclear soft speech with nasal twang since early childhood. He used to sleep with partial open eyes and could not move eyeballs in either direction. He did not have marked difficulty walking, running, and climbing stairs but had trouble rising from supine and raise arms above his head. There was no fluctuation in his symptoms: he never complained of fatigue and his weakness remained static. His vision and hearing were normal. There was no history of seizures, other cranial nerve involvement, difficulty swallowing, weakness of neck or trunk muscles, palpitations, and autonomic or sensory disturbances. He was studying in school, with age-appropriate cognitive performance.

On examination, he has normal head size, bilateral ptosis, complete external ophthalmoplegia on the right side, right pupils 3 mm reacting to light, and enucleated left eye. He has marked facial weakness with narrow, expressionless, elongated facies, temporal and masseter wasting, V-shaped upper lip, protruded tongue, and open mouth with hanging lower jaw ( Fig. 1 ). We obtained informed consent from the subject to reveal the facial profile of the patient publicly. Generalized wasting, poor muscle bulk, wasting of the deltoid, biceps, triceps, forearm muscles, quadriceps, hamstrings, and calves were observed. He also had mild neck flexor and pelvic girdle weakness. Gowers sign was present with one hand support. Contractures were present at bilateral tendoachillis, elbow, and fingers (proximal interphalangeal) joints. Reflexes were absent, only supinator was elicitable. There were no tongue fasciculations, polyminimyoclonus, myotonia, or worsening of ptosis on persistent upgaze or fatiguability. Clinical diagnosis of congenital myopathy, congenital myasthenic syndromes, and mitochondrial myopathy were considered.

Fig. 1.

Facial profile of the index child, showing right eye ptosis, left eye postenucleation, elongated, triangular, and expressionless facies, open mouth, high-arched palate, prognathia, maloccluded teeth, and enlarged tongue ( A ).

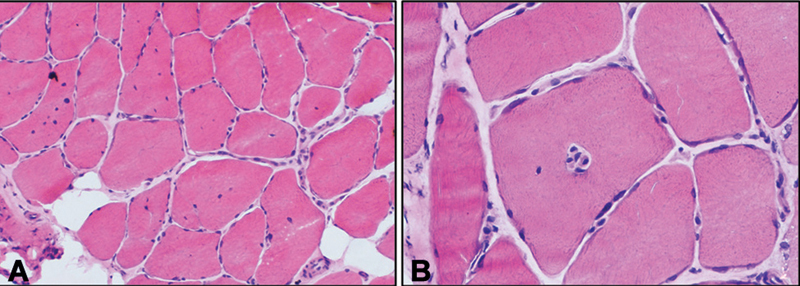

Nerve conduction and repetitive nerve stimulation studies were normal. Electromyography studies showed fasciculations and reduced motor unit action potentials over the first dorsal interossei and tibialis anterior muscles. Serum creatine kinase levels were 112 U/L (range = 25–170 U/L). Muscle biopsy from quadriceps femoris revealed marked variation in fiber size, fiber splitting, type-I fiber predominance (ATPase stain), and marked internalization of nuclei which are centrally located (in >40% muscle fibers). No nemaline rods on the Gomori trichrome stain and central pale core were identified. The muscle biopsy was suggestive of CNM ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Quadriceps muscle biopsy of the index child showing predominantly transversely oriented muscle fibers with moderate variation in fiber size and shape with the presence of many hypertrophic fibers. A marked increase in the internalization of nuclei is noted with multiple nuclei located in the center of muscle fiber (40%; hematoxylin and eosin, 200 × ). ( B ) Single fiber showing multiple centrally placed nuclei within a single muscle fiber (hematoxylin and eosin, 400 × ).

Neuromuscular disorder gene panel on next-generation sequencing revealed a novel compound heterozygous nonsense variation in exon 20 [c.2449C > T] resulting in stop codon and premature truncation of protein at codon 817 {p.(Arg817Ter)}. The other variant was a known heterozygous missense variation in exon 79 [c.11314C > T p.(Arg3772Trp)] of the RYR1 gene, the observed variant has previously been reported in patients affected with congenital myopathy and has been reported as likely pathogenic in clinvar. 13 19 This variant substituted a highly conserved arginine residue into a nonconservative tryptophan located in a cytoplasmic domain of an unknown function. The in-silico predictions of the variant are probably damaging by polymorphism phenotyping v2 and damaging by sorting intolerant from tolerant and mutation taster 2. Parental testing could not be done due to financial constraints; hence, the compound heterozygous variants are assumed to be pathogenic.

Discussion

Recessive RYR1 variants can have different biopsy findings ranging from normal muscle to the presence of several centrally located internal nuclei, type 1 predominance with or without cores, multiple cores, and presence of both rods and cores. Dusty cores represent the characteristic and unifying histopathological feature seen in R YR1 -recessive myopathies. They are characterized by the deposition of reddish-purple granular material corresponding to areas of altered enzyme activity at oxidative stains. 20 The histopathological clues for RYR1 -related CNM include the presence of multiple internal nuclei in addition to central nuclei, type 1 fiber predominance and hypotrophy, and subtle Z-line disarray on electron microscopy. 21 These histopathological features evolve and need not be present at biopsies done at an earlier age. The presence of large areas of sarcomeric disorganization of muscle fibers on oxidative and ATPase techniques can guide us to screen for RYR1 variants in cases that were previously diagnosed as CNM. 20 21

We have summarized the clinical, histopathologic, and genetic features of 38 patients with RYR1 -related CNM published since 2007 in Table 1 . Till now, 60 cases have been described in the literature. 6 8 10 12 13 20 22 Patients with RYR1 -associated congenital CNM have onset of symptoms at birth except two cases described by Garibaldi et al, and all the cases had autosomal recessive inheritance except one case described by Jungbluth et al. 6 20 Delayed motor milestones were seen in 79% of the patients followed by neonatal hypotonia in 68%, respiratory difficulties at birth in 47%, and feeding difficulties at birth in 45% of the patients. Ptosis was seen in 18 patients (47%) and 24 patients (63%) had ophthalmoparesis. The common orthopedic comorbidities include scoliosis, contractures over the elbow, knee, and ankle, winged scapula, kyphosis, lordosis, and rigid spine. On follow-up, the children with recessive RYR1 -related CNM develop frequent scoliosis and wheel-chair dependency. 6 10 The index patient also had similar early-onset and severe clinical presentation secondary to recessive RYR1 -related CNM as reported in the previous literature ( Table 1 ). The external ophthalmoplegia and inability to close the eyes completely predisposed to exposure keratitis and endophthalmitis in the index case. In addition, the index case also had marked ocular and facial weakness in comparison to axial and appendicular muscles weakness. The peculiar clinical features include an open mouth with a hanging lower jaw with characteristic elongated facies.

Table 1. Clinical, histopathological, and genetic findings of 38 patients with RYR1 -related centronuclear myopathy .

| Study | Sex | Onset | Variant | Inheritance | Survival | Clinical features | Muscle biopsy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory problems at birth | Feeding problems at birth | Hypotonia at birth | Delayed motor milestones | Extraocular muscle involvement | Orthopedic complication | Age at biopsy | CN; IN (%) |

Type I pred/hyp | Other structural abnormalities | ||||||

| Present case | |||||||||||||||

| Patient 1 | M | Birth | C.Heterozygous[c.2449C > T p.(Arg817Ter)] and [c.11314C > T p.(Arg3772Trp)] | ? AR |

Yes, 18 y | − | + | + | + | P, OP | C (A, E) | 18 y | 40 | +/+ | |

| Jungbluth et al 9 (2007) | |||||||||||||||

| Patient 1 | F | Birth | Heterozygous, p.Ser4112Leu | AD | Yes, 16 y | − | + | + | + | P, OP | Right TE;S | 9 y | + | ± | Core-like areas devoid of COX activity |

| Bevilacqua et al 8 (2011) | |||||||||||||||

| Patient 1 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.[10348‐6C > G; 14524G > A] + c.[8342_8343delTA] | AR | Yes, 15 y | + | − | + | + | OP, P | C (H, K, A) | 14 y | 4;47 | +/+ | SAD |

| Patient 2 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, p.[Thr4709Met] + p.[Glu4181Lys] | AR | Yes, 24 y | + | − | + | + | P | C (E, A) | 12 y | 7.2;23.7 | +/+ | SAD |

| Patient 3 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, p.[Glu4911Lys] and p.[Arg2336Cys] variants. | AR | Yes, 24 y | − | + | − | + | 16 y | 3.3;5.5 | +/+ | SAD | ||

| Patient 4 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, p.[Pro3202Leu] + p.[Gly3521Cys] | AR | Yes, 39 y | − | − | + | + | OP | S | 37 y | 6.7;29 | +/+ | SAD |

| Patient 5 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, p.[Pro3138Leu] + p.[Arg3772Trp] | AR | Yes, 28 y | + | − | − | + | OP, P | C (A) | 21 y | 4.8;29.5 | +/+ | SAD |

| Patient 6 | M | Birth | c.8692 + 131G > A | AR | Yes, 32 y | − | − | + | + | OP | 26 y | 3.3;9 | ± | SAD | |

| Patient 7 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, p.[Pro3202Leu] + p.[Arg4179His] | AR | Yes, 6 y | − | + | + | + | P | 5 y | 1.3;1.3 | +/+ | SAD | |

| Fattori et al 7 (2015) | |||||||||||||||

| Patient 1 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, p.Asp4021 fs*4 and p.His903GlndelPro904 | AR | Yes, 9 y | + | − | + | + | OP | S | 4 y | 20 | +/+ | Minicores |

| Patient 2 | M | Birth | Hetero, p.Arg2118Trp, p.Pro4973Leu and c.10347 + 1G > A mutations |

AR | Yes, 45 y | + | + | − | + | OP | C (K, A) | 30 y | 25 | +/+ | Core-like atypical structures |

| Patient 3 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, p.Gly2365Arg and p.Glu3583Gln | AR | Yes, 5 y | + | + | + | + | S | 7 mo | 25 | +/+ | ||

| Neto et al 11 (2017) | |||||||||||||||

| Patient 1 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, c.1576 + 1G > A and c.7093G > A | AR | Yes, 5 y | − | + | + | + | P | C (A) | 6 mo | 30 | ± | |

| Patient 2 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.1576 + 1G > A and c.7093G > A | AR | Yes, 12 y | − | − | + | + | P | 6 y | 30 | ± | IMA abnormalities | |

| Patient 3 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, c.6797–6 6798del and c.9892G > A | AR | Yes, 12 y | − | + | + | + | K, L, WS | 5 y | 40 | +/+ | IMA abnormalities | |

| Patient 4 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.6797–6 6798del and c.9892G > A | AR | Yes, 7 y | + | − | + | + | WS | |||||

| Patient 5 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, c.4837C > T and c.3523G > A | AR | Yes, 51 y | − | + | − | + | OP | S, multiple C | 44 y | 90 | ± | IMA abnormalities |

| Patient 6 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.4837C > T and c.3523G > A | AR | Yes, 43 y | + | + | − | + | OP | L, multiple C | 37 y | 90 | ± | IMA abnormalities |

| Patient 7 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, c.9611C > T and c.14545G > A | AR | Yes, 16 y | + | − | + | + | OP | RS, WS, multiple C | 13 y | 70 | ± | IMA abnormalities |

| Patient 8 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.7027G > A and c.13672C > T | AR | Yes, 6 y | − | − | + | + | OP | 3 y | 40 | ± | IMA abnormalities | |

| Patient 9 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.3224G > A and c.10882C > G | AR | Yes, 10 y | + | + | + | + | WS | 2 y | 50 | ± | ||

| Patient 10 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.725G > A and c.10348–6C > G | AR | Yes, 5 y | + | + | + | + | P | 2.5 y | 30 | ± | IMA abnormalities | |

| Patient 11 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.6797–6_6798del and c.1342A > T | AR | Yes, 40 y | − | − | − | + | OP | 38 y | 70 | ± | IMA abnormalities | |

| Patient 12 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, c.3224G > A and c.3523G > A | AR | Yes, 26 y | + | − | − | − | OP | RS, S | 12 y | 50 | ± | IMA abnormalities |

| Patient 13 | M | Birth | Md 93–100 and c.14524G > A | AR | Yes, 8 y | − | − | + | + | P, OP | 1 y | 20 | +/+ | IMA abnormalities | |

| Patient 14 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.8372del and c.14545G > A | AR | Yes, 8 y | − | − | + | + | P, OP | RS | 2.8 y | 60 | ± | |

| Patient 15 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.6295_6351dup and c.11763C > A | AR | Yes, 6 y | + | − | + | + | P, OP | RS, WS, lower extremity C | 2.5 y | 20 | ± | IMA abnormalities |

| Patient 16 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.14524G > A and c.10946_10947insC | AR | Yes, 26 y | + | − | + | NW | P, OP | RS, multiple C | 0.5 y | NA | NA | |

| Patient 17 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.1201C > T and c.7463_7475del | AR | Yes, 4 y | − | + | + | − | RS, S, multiple C | 0.1 y | 30 | ± | IMA abnormalities | |

| Patient 18 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.14416A > G and c.3866G > C | AR | Yes, 0 y | + | + | + | − | P | K, S | 0.04 y | NA | NA | NA |

| Patient 19 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, c.325C > T and c.6891 + 1G > T | AR | Yes, 54 y | − | − | − | + | P, OP | L | 8 y | 20 | ± | IMA abnormalities |

| Patient 20 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, c.3523G > A and c.5444del | AR | Yes, 29 y | + | − | − | + | OP | S | NA | 70 | ± | IMA abnormalities |

| Patient 21 | F | Birth | C.Hetero, sc.2500_2501dup and c.8024C > A | AR | Yes, 3 y | + | + | + | NW | OP | S, multiple C | 1 y | 70 | NA | NA |

| Garibaldi et al 16 (2019) | |||||||||||||||

| Patient 1 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, c.7025A > G and c.3223C > T | AR | Yes, 45 d | + | + | + | NW | P, OP | 45 d | + | ± | Dusty cores, SAD | |

| Patient 2 | M | Birth | C.Hetero, c.6891 + 1G > T and c.325C > T | AR | Yes, 48 y | − | + | − | n.r. | P, OP | S | 48 y | + | ± | Perinuclear disorganization and vacuolization; SAD |

| Patient 3 | F | 10 y | C.Hetero, c.1897C > T and c.7372C > T | AR | Yes, 69 y | − | − | − | − | C (A) | 57 y | + | ± | SAD | |

| Patient 4 | M | 1 y | C.Hetero, c.4225C > T and c.14126C > T | AR | Yes, 4 y | − | − | − | + | P | 4 y | + | −/− | SAD | |

| Patient 5 | M | Birth | c.7615–3T > A and duplication at least exon 99–106 | AR | Yes, 25 y | − | − | + | + | OP | C (K) | 7 y | + | ± | TR inside dusty cores, SAD |

Abbreviations: A, ankle; AD, autosomal dominant inheritance; AR, autosomal recessive inheritance; C, contractures; CN, central nuclei; COX, cytochrome oxidase; E, elbow; F, female; H, hip; hyp, hypertrophy; IMA, intermyofibrillary network; IN, internalized nuclei; K, knee; K, kyphosis; L, lordosis; M, male; Md, macrodeletion; n.r., not reported; NA, not available; NW, not able to walk; OP, ophthalmoparesis; P, ptosis; pred, predominance; RS, rigid spine; S, scoliosis; SAD, small areas of myofibrillar disorganization; TE, talipes equinovarus; TR, triad replication; WS, winged scapula.

The percentage of central nuclei ranged from 1 to 90% in all the patients with RYR1 -associated myopathies. Other histopathological features include type 1 predominance, the presence of dusty cores and fiber-type disproportion, and abnormalities in the intermyofibrillar network. The majority of the patients are found to be compound heterozygous for RYR1 with two missense variants or one missense variant and one hypomorphic variant. 9 23 The nonsense variant of c.2449C > T (p.Arg817Ter) observed in the index patient was not described previously, while the c.11314C > T (p.Arg3772Trp) variant was previously reported in a family with malignant hyperthermia. 13 19 This variant has also been reported in a homozygous or compound heterozygous state with other variants in the RYR1 gene depicting autosomal recessive inheritance for these disorders. 13

Conclusion

RYR1 -related CNM has distinct clinical features of early infantile-onset ptosis, external ophthalmoplegia, marked facial weakness, hanging jaw, suggestive muscle biopsy, and specific muscle MRI changes. However, the muscle biopsy findings alone are not sufficient to diagnose a specific congenital myopathy, and genetics has an important role in making a specific diagnosis, and predicting future generations' risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the parents for giving consent for the photographs of the patient.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Note

The manuscript was approved by the Departmental Review Board.

Authors' Contributions

B.S. and S.K. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript and reviewed the literature. D.A. and D.C. provided histopathological inputs to the manuscript. A.U. provided neuromuscular inputs and intellectual content. R.S. involved in a critical review of the manuscript and reviewed the literature and edited the final version of the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Amburgey K, McNamara N, Bennett L R, McCormick M E, Acsadi G, Dowling J J. Prevalence of congenital myopathies in a representative pediatric united states population. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(04):662–665. doi: 10.1002/ana.22510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein A, Lillis S, Munteanu I et al. Clinical and genetic findings in a large cohort of patients with ryanodine receptor 1 gene-associated myopathies. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(06):981–988. doi: 10.1002/humu.22056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biancalana V, Beggs A H, Das S et al. Clinical utility gene card for: Centronuclear and myotubular myopathies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(10):10. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilmshurst J M, Lillis S, Zhou H et al. RYR1 mutations are a common cause of congenital myopathies with central nuclei. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(05):717–726. doi: 10.1002/ana.22119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jungbluth H, Zhou H, Hartley L et al. Minicore myopathy with ophthalmoplegia caused by mutations in the ryanodine receptor type 1 gene. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1930–1935. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000188870.37076.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jungbluth H, Zhou H, Sewry C A et al. Centronuclear myopathy due to a de novo dominant mutation in the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor (RYR1) gene. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17(04):338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiro A J, Shy G M, Gonatas N K. Myotubular myopathy. Persistence of fetal muscle in an adolescent boy. Arch Neurol. 1966;14(01):1–14. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1966.00470070005001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abath Neto O, Moreno C AM, Malfatti E et al. Common and variable clinical, histological, and imaging findings of recessive RYR1-related centronuclear myopathy patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(11):975–985. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amburgey K, Bailey A, Hwang J H et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in recessive RYR1-related myopathies. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:117. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson R, Carpenter D, Shaw M A, Halsall J, Hopkins P. Mutations in RYR1 in malignant hyperthermia and central core disease. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(10):977–989. doi: 10.1002/humu.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou H, Yamaguchi N, Xu L et al. Characterization of recessive RYR1 mutations in core myopathies. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(18):2791–2803. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fattori F, Maggi L, Bruno C et al. Centronuclear myopathies: genotype-phenotype correlation and frequency of defined genetic forms in an Italian cohort. J Neurol. 2015;262(07):1728–1740. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bevilacqua J A, Monnier N, Bitoun M et al. Recessive RYR1 mutations cause unusual congenital myopathy with prominent nuclear internalization and large areas of myofibrillar disorganization. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37(03):271–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jungbluth H, Davis M R, Müller C et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of muscle in congenital myopathies associated with RYR1 mutations. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14(12):785–790. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee . Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(05):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawal T A, Todd J J, Meilleur K G. Ryanodine receptor 1-related myopathies: diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15(04):885–899. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-00677-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jungbluth H, Ochala J, Treves S, Gautel M. Current and future therapeutic approaches to the congenital myopathies. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2017;64:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawal T A, Todd J J, Witherspoon J W et al. Ryanodine receptor 1-related disorders: an historical perspective and proposal for a unified nomenclature. Skelet Muscle. 2020;10(01):32. doi: 10.1186/s13395-020-00243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levano S, Vukcevic M, Singer M et al. Increasing the number of diagnostic mutations in malignant hyperthermia. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(04):590–598. doi: 10.1002/humu.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garibaldi M, Rendu J, Brocard J et al. ‘Dusty core disease’ (DuCD): expanding morphological spectrum of RYR1 recessive myopathies. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7(01):3. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0655-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centronuclear (Myotubular) Myopathy Consortium . Jungbluth H, Wallgren-Pettersson C, Laporte J F. 164th ENMC International workshop: 6th workshop on centronuclear (myotubular) myopathies, 16-18th January 2009, Naarden, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19(10):721–729. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.06.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samões R, Oliveira J, Taipa R et al. RYR1-related myopathies: clinical, histopathologic and genetic heterogeneity among 17 patients from a portuguese tertiary centre. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2017;4(01):67–76. doi: 10.3233/JND-160199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Todd J J, Sagar V, Lawal T A et al. Correlation of phenotype with genotype and protein structure in RYR1-related disorders. J Neurol. 2018;265(11):2506–2524. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]