Abstract

In the pathogenic bacterium Vibrio cholerae, the alternate sigma factor ς54 is required for expression of multiple sets of genes, including an unidentified gene(s) necessary for enhanced colonization within the host. To identify ς54-dependent transcriptional activators involved in colonization, PCR was performed with V. cholerae chromosomal DNA and degenerate primers, revealing six novel and distinct coding sequences with homology to ς54-dependent activators. One sequence had high homology to the luxO gene of V. harveyi, which in that organism is involved in quorum sensing. Phenotypes of V. cholerae strains containing mutations in each of the six putative ς54-dependent activator genes identified one as a probable ntrC homologue. None of the mutant strains exhibited a defect in the ability to colonize infant mice, suggesting the presence of additional ς54-dependent activators not identified by this technique.

Cholera is a life-threatening diarrheal disease caused by the gram-negative bacterium Vibrio cholerae. V. cholerae enters humans orally through ingestion of contaminated food or water, swims toward and penetrates the mucus gel lining of the small intestine, and eventually adheres to the apical surface of the intestinal epithelial cells. V. cholerae bacteria respond to the specific environment encountered within the host intestine and express a number of virulence factors which allow the organisms to colonize the surface of the epithelial cells and cause disease; under normal in vitro growth conditions, virulence factors are not expressed (3). Several major virulence factors have been identified, most notably, cholera toxin (CT) and toxin coregulated pilus (TCP) (9, 16). However, it has become clear that other, unidentified factors are produced which aid in colonization and induce disease. Identification of such factors remains problematic, given that they are probably expressed only within a specific host environment. Although in vitro conditions have been developed which elicit V. cholerae CT and TCP production, these conditions are clearly not those encountered within the host (for example, CT and TCP are expressed optimally at 30°C in the Classical biotype). Thus, the identification of genes required for V. cholerae pathogenesis and the environmental signals that regulate their expression remains an active area of research.

RNA polymerase containing the alternate sigma factor ς54 (ς54-holoenzyme) transcribes genes with diverse physiological roles in different bacteria, including pilin genes in pathogenic Neisseria and Pseudomonas spp., which are important for colonization by these organisms (8). ς54 is likewise required for some aspect of V. cholerae colonization. A V. cholerae strain containing a mutation in the gene encoding ς54 (rpoN) has a significant defect in the ability to colonize, but this defect is distinct from two other phenotypes associated with the rpoN strain, namely, nonmotility and low levels of glutamine synthetase expression (7). The rpoN strain also produces normal amounts of TCP under laboratory inducing conditions, so the nature of the ς54-dependent gene(s) which enhances colonization remain unknown. ς54-Holoenzyme has a requirement for an activator protein to initiate transcription; ς54-dependent transcriptional activators generally bind to DNA enhancer elements located within the promoter region and activate transcription by direct contact with ς54-holoenzyme (8, 14).

We have previously identified two ς54-dependent transcriptional activators, FlrA and FlrC, which are required for V. cholerae flagellar synthesis (7). However, strains containing mutations in either flrA or flrC do not demonstrate the severe colonization defect observed in a V. cholerae rpoN strain, thus implying that an additional ς54-dependent activator(s) is involved in colonization. We utilized PCR with degenerate oligonucleotides to identify six additional ς54-dependent transcriptional activators of V. cholerae. We have tentatively assigned roles in quorum sensing and nitrogen assimilation to two of these newly discovered ς54-dependent transcriptional activators, based on sequence and phenotype, but none appears to be involved in colonization. Our results suggest the presence of yet more unidentified ς54-dependent transcriptional activators in V. cholerae and demonstrate the involvement of ς54 in the expression of multiple sets of genes in this pathogen.

Identification of multiple V. cholerae ς54-dependent transcriptional activators.

The V. cholerae rpoN mutant strain is defective in the ability to colonize a host and is, additionally, nonmotile (nonflagellated) and expresses low levels of glutamine synthetase (7); these phenotypes are distinct from the colonization defect. We thus predicted the presence of more ς54-dependent transcriptional activators in addition to the two flagellar activators FlrA and FlrC. All ς54-dependent activators are modular proteins, and they contain a highly conserved catalytic domain required for activation of transcription by ς54-holoenzyme (17). Kaufman and Nixon (5) demonstrated that ς54-dependent transcriptional activators could be isolated by PCR utilizing degenerate primers designed to recognize this conserved catalytic domain. We utilized their technique with identical primers recognizing the conserved amino acids (W/F)PGNV and ELFGH(V/A/D/E/G) and chromosomal DNA from V. cholerae Classical biotype strain O395 (11); the primers also incorporated restriction sites for EcoRI and BamHI. The PCR with Taq DNA polymerase consisted of 30 cycles of 92°C for 45 s, 42°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min. The resulting fragments were first digested with EcoRI and BamHI and then ligated into pTZ19U (10) that had been similarly digested.

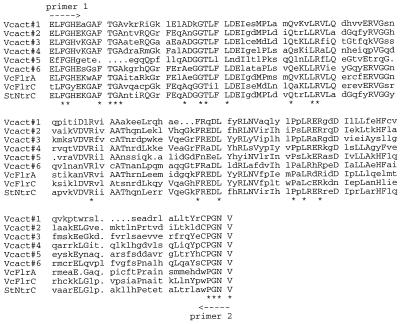

Restriction analysis of the resultant recombinant clones revealed seven distinct PCR-derived fragment inserts. These seven fragments were sequenced directly from the plasmid by utilizing an ABI 373AStretch sequencer, and the deduced amino acid sequences are shown in Fig. 1. One fragment was identical to the sequence of flrA, which encodes a V. cholerae ς54-dependent transcriptional activator of flagellar genes previously described (7), thus validating this technique for the identification of such activators in V. cholerae. The other six sequences were novel, and the predicted amino acid sequences share high homology with ς54-dependent transcriptional activators from different bacteria. Interestingly, flrC, which encodes the only other V. cholerae ς54-dependent transcriptional activator previously described (7), was not isolated by this technique. This may be due to two amino acid deviations from the consensus ELFGH sequence in FlrC (Fig. 1), resulting in the failure of the degenerate oligonucleotide primers to amplify the coding sequence, raising the possibility that perhaps yet more ς54-dependent activators that deviate from the consensus remain to be identified in this organism.

FIG. 1.

Homology of s54act gene products with the catalytic domains of ς54-dependent transcriptional activators. Deduced amino acid sequences of PCR-derived fragments containing putative ς54-dependent transcriptional activators from V. cholerae were aligned by GCG Pileup with the amino acid sequences of the ς54-dependent activators FlrA (amino acids 154 to 302) and FlrC (amino acids 146 to 295) from V. cholerae and NtrC (amino acids 157 to 306) from S. typhimurium. Amino acids found in at least five activators are in capital letters, and amino acids common to all nine activators are designated by asterisks. Sequences recognized by degenerate primers used in PCR are designated by arrows.

The partial sequences of the putative V. cholerae ς54-dependent activators were named s54act1 to s54act6. The predicted protein product of s54act1 shares the highest homology with the dicarboxylic acid transport regulatory protein DctD from Rhizobium meliloti (62% identity), while the s54act2 gene product is most homologous to the nitrogen regulatory protein NtrC from Salmonella typhimurium (77% identity). The putative protein encoded by s54act3 has very high homology (90% identity) to the LuxO protein of the closely related symbiotic bacterium V. harveyi. LuxO is a repressor of luminescence, and its activity is modulated by signals perceived through quorum sensing (2). Curiously, Bassler and colleagues failed to acknowledge the possibility that LuxO exerts its effects by activation of ς54-dependent transcription, despite noting the homology of LuxO with the ς54-dependent activator NtrC. Bassler et al. have recently shown that V. cholerae produces an autoinducer substance that can be recognized by the V. harveyi quorum sensing system (1), and quorum sensing has been shown to modulate the expression of virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (13). V. cholerae is not bioluminescent, so we predict that s54act3 encodes a LuxO homologue modulated by quorum sensing signals, similar to V. harveyi LuxO, which may modulate the expression of virulence factors.

The predicted protein encoded by s54act4 shares the highest homology with a hypothetical ς54-dependent transcriptional activator from Escherichia coli (YgaA; 64% identity), while that encoded by s54act5 is most homologous to NtrC from Proteus vulgaris (43% identity). Finally, the putative s54act6 gene product is most homologous to PspF from E. coli, the ς54-dependent transcriptional activator of the phage shock protein operon (70% identity). Given the modular nature of ς54-dependent activators, the function of the particular V. cholerae activator cannot necessarily be deduced by homology with the catalytic domain of another ς54-dependent activator, with the possible exception of s54act3 because of the extremely high degree of homology with luxO and the close relationship between these two Vibrio spp.

s54act4 probably encodes an NtrC homologue.

To determine the function of the s54act1 to s54act6 gene products, V. cholerae strains containing mutations in each gene were constructed. The internal fragments amplified by PCR and ligated into pTZ19U as described above were first digested with BamHI, made blunt ended with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase, digested with EcoRI, and then ligated into pGP704 (12) that had been digested with EcoRI and EcoRV. Since pGP704 requires the pir gene product for replication, mobilization of the recombinant plasmids containing internal s54act gene fragments into V. cholerae (which lacks pir) results in a chromosomal insertion into the s54act genes caused by integration of the plasmid through homologous recombination. These plasmids were mobilized into V. cholerae wild-type strain O395 (11) from E. coli SM10λpir (12), as previously described (6), to form strains KKV216 (s54act1::pGP704), KKV217 (s54act2::pGP704), KKV218 (s54act3::pGP704), KKV219 (s54act4::pGP704), KKV221 (s54act5::pGP704), and KKV220 (s54act6::pGP704).

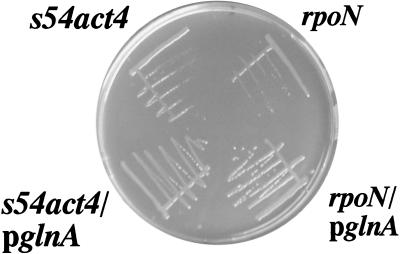

The V. cholerae rpoN strain expresses low levels of glutamine synthetase, a Gln phenotype which results in slow growth on glutamine-limited nutrient broth medium (Fig. 2) (7). Wild-type growth can be restored by transforming the rpoN strain with pKEK71, which expresses S. typhimurium glutamine synthetase (glnA) from a ς54-independent promoter. The V. cholerae s54act4 mutant displays a Gln phenotype similar to that of the rpoN strain when grown on nutrient broth, and wild-type growth can likewise be restored when it is transformed with pKEK71 (Fig. 2). None of the other s54act mutant strains exhibited such a Gln phenotype. These results are consistent with the idea that s54act4 encodes a homologue of NtrC, the ς54-dependent nitrogen regulatory protein which activates glnA transcription in many different bacteria (14).

FIG. 2.

The s54act4 mutant displays a growth defect on glutamine-deficient medium that is complemented by expression of glnA. Strains were grown for 24 h on nutrient broth agar. The strains shown are KKV55 (ΔrpoN [7]) and KKV219 (s54act4::pGP704), either without or with plasmid pKEK71 (“pglnA” [7]), which expresses S. typhimurium glnA from a ς54-independent promoter.

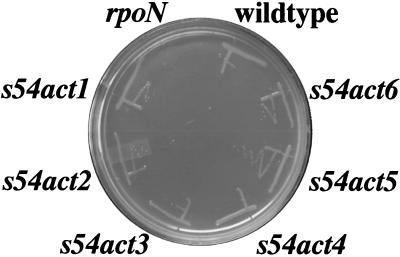

All of the V. cholerae s54act1 to s54act6 mutant strains are able to grow on minimal glucose ammonia medium (although the s54act4 strain grows slowly due to lack of glutamine), and all displayed wild-type motility in a soft agar swarm assay (data not shown), indicating that none of these regulators activates the expression of genes necessary for prototrophy or motility. The V. cholerae rpoN strain is unable to grow on minimal medium containing succinate as the sole carbon source (Fig. 3), a phenotype associated with a lack of expression of dicarboxylic acid transport genes, which are transcribed by ς54-holoenzyme in several bacteria (4). However, all of the V. cholerae s54act mutant strains grow similarly to a wild-type strain on minimal succinate medium, indicating that none of these novel activators encodes a homologue of DctD, the ς54-dependent activator of dicarboxylic acid transport genes. V. cholerae strains containing mutations in either flagellar ς54-dependent activator gene flrA or flrC are also able to grow by utilizing succinate as a carbon source (data not shown); we thus predict the presence of at least one additional unidentified V. cholerae ς54-dependent activator, namely, a DctD homologue.

FIG. 3.

s54act mutants are able to utilize succinate as a carbon source, unlike an rpoN mutant. Strains were grown for 48 h on minimal medium containing 10 mM ammonium, 2 mM glutamine, and 0.4% succinate. The strains shown are O395 (wild type [11]), KKV55 (ΔrpoN [7]), KKV216 (s54act1), KKV217 (s54act2), KKV218 (s54act3), KKV219 (s54act4), KKV221 (s54act5), and KKV220 (s54act6).

None of the newly identified ς54-dependent activators is required for colonization.

The ability of V. cholerae to colonize the intestines of infant mice is correlated with its ability to colonize the human intestine (15), and thus, the infant mouse model is a widely used model of V. cholerae virulence. The V. cholerae s54act mutant strains were tested for the ability to colonize infant mice by utilizing a competition assay previously described (7). Briefly, a mutant strain is coinoculated orally into infant mice along with an isogenic wild-type strain, and the amounts of mutant and wild-type strains which successfully colonize are determined after 24 h from intestinal homogenates. Any colonization defect of the mutant is reflected in a lower ratio of mutant to wild-type strains recovered from the intestine.

None of the V. cholerae s54act strains demonstrated reduced colonization in infant mice (Table 1). We have previously shown that mutations in the ς54-dependent flagellar activators FlrA and FlrC result in approximately 10-fold defects in colonization. Because FlrA is required for transcription of flrC, the defect in both flagellar regulatory mutants is probably due to a lack of FlrC. However, an rpoN strain exhibits an approximately 100-fold defect in colonization (7). Since none of the newly identified ς54-dependent activators appears to be required for efficient colonization, an additional, unidentified activator(s) may be present in V. cholerae which transcribes a gene(s) involved in colonization. Alternately, the absence of expression of multiple sets of ς54-dependent genes mediated by more than one activator may have an additive effect and diminish colonization efficiency. If the putative LuxO homologue encoded by s54act4 modulates colonization genes, it must act as a repressor in V. cholerae also, since inactivation does not prevent colonization. Not surprisingly, all of the s54act mutant strains expressed similar wild-type levels of the virulence factors CT and TCP under laboratory inducing conditions (data not shown); the same was shown previously for the rpoN strain (7). Thus, the nature of the ς54-dependent genes required for colonization remains unknown.

TABLE 1.

Infant mouse colonization assaya results

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Competitive indexb |

|---|---|---|

| 0395 | Wild type | 1.35c |

| KKV56 | ΔrpoN | 0.030c |

| KKV216 | s54act1 | 0.888 |

| KKV217 | s54act2 | 1.809 |

| KKV218 | s54act3 | 1.904 |

| KKV219 | s54act4 | 1.013 |

| KKV221 | s54act5 | 0.801 |

| KKV220 | s54act6 | 0.711 |

| KKV59 | ΔflrA | 0.141c |

The assay was performed as previously described (7). The values shown are based on a group of at least seven mice.

The competitive index is the ratio of output mutant to wild-type bacteria recovered from the intestine divided by the ratio of input mutant to wild-type bacteria inoculated into mice. Thus, if a mutant strain has no colonization defect, we expect a competitive index of close to 1. The P values for the rpoN and flrA strains were <0.05 by Student’s t test, indicating significant differences in colonizing ability, but none of the other strains showed any statistically significant differences from a wild-type strain in the ability to colonize.

The value has been reported previously (7).

We have identified eight putative and proven ς54-dependent transcriptional activators in V. cholerae and inferred the presence of at least one, and possibly two, more which has yet to be identified. Our results establish the involvement of ς54 in the expression of multiple sets of genes in V. cholerae, including those for flagellar synthesis, glutamine synthetase expression, and dicarboxylic acid transport; some genes involved in colonization; and possibly some quorum sensing-regulated genes; as well as other, unidentified genes regulated by the activators with no known function.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The following sequences have been deposited in GenBank and assigned the corresponding accession numbers: s54act1, AF069055; s54act2, AF069056; s54act3, AF069387; s54act4, AF069388; s54act5, AF069389; s54act6, AF069390.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dan Steiger for DNA sequence support and Darren Schuhmacher for assistance with figures.

This study was supported by an institutional new faculty award of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to K.E.K. and NIH grant AI-18045 to J.J.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassler B L, Greenberg E P, Stevens A M. Cross-species induction of luminescence in the quorum-sensing bacterium Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4043–4045. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4043-4045.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassler B L, Wright M, Silverman M R. Sequence and function of luxO, a negative regulator of luminescence in Vibrio harveyi. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:403–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmgren J, Svennerholm A M. Mechanisms of disease and immunity in cholera: a review. J Infect Dis. 1989;136:S105–S112. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.supplement.s105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang J, Gu B H, Albright L M, Nixon B T. Conservation between coding and regulatory elements of Rhizobium meliloti and Rhizobium leguminosarum dct genes. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5244–5253. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5244-5253.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman R I, Nixon B T. Use of PCR to isolate genes encoding ς54-dependent activators from diverse bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3967–3970. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3967-3970.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klose K E, Mekalanos J J. Differential regulation of multiple flagellins in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:303–316. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.303-316.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klose K E, Mekalanos J J. Distinct roles of an alternative sigma factor during both free-swimming and colonizing phases of the Vibrio cholerae pathogenic cycle. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:501–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kustu S, Santero E, Keener J, Popham D, Weiss D. Expression of ς54 (ntrA)-dependent genes is probably united by a common mechanism. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:367–376. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.3.367-376.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lospalluto J J, Finkelstein R A. Chemical and physical properties of cholera exo-enterotoxin (choleragen) and its spontaneously formed toxoid (choleragenoid) Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;257:158–166. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(72)90265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mead D A, Szczesna-Skorupa E, Kemper B. Single-stranded DNA ’blue’ T7 promoter plasmids: a versatile tandem promoter system for cloning and protein engineering. Protein Eng. 1986;1:67–74. doi: 10.1093/protein/1.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mekalanos J J, Collier R J, Romig W R. Enzymic activity of cholera toxin. II. Relationships to proteolytic processing, disulfide bond reduction, and subunit composition. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:5855–5861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller V L, Mekalanos J J. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Passador L, Cook J M, Gambello M J, Rust L, Iglewski B H. Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes requires cell-to-cell communication. Science. 1993;260:1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.8493556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porter S C, North A K, Kustu S. Mechanism of transcriptional activation by NtrC. In: Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson S H. Animal models in cholera research. In: Wachsmuth I K, Blake P A, Olsvik Ø, editors. Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 203–226. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor R K, Miller V L, Furlong D B, Mekalanos J J. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2833–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss D S, Batut J, Klose K E, Keener J, Kustu S. The phosphorylated form of the enhancer-binding protein NTRC has an ATPase activity that is essential for activation of transcription. Cell. 1991;67:155–167. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90579-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]