Abstract

Rationale & Objective

The Illinois Transplant Fund, established in 2015, provides private health insurance premium support for noncitizen patients with kidney failure in Illinois and thus allows them to qualify for kidney transplants. Our objective was to describe trends in kidney transplant volumes over time to inform the development of a hypothesis regarding the impact of the Illinois Transplant Fund on kidney transplant volumes for adult Hispanic patients with kidney failure in Illinois, especially noncitizen patients.

Study Design

Retrospective study.

Setting & Population

We used data on the annual number of kidney transplants and kidney failure prevalence aggregated to the national and state levels from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and United States Renal Data System, respectively.

Outcomes

The annual number of transplants as a percentage of prevalent kidney failure cases among adults over time from 2010 to 2020 by race/ethnicity for all payer and private insurance-paid transplants and the annual number of transplants by citizenship status (for Hispanic patients only) were examined for the United States (US), Illinois, and 6 selected US states.

Analytical Approach

Descriptive study.

Results

From pre- to post-Illinois Transplant Fund, the average annual number of transplants as a percentage of the average annual prevalent kidney failure cases for Hispanic adults increased by 4% in Illinois while the same figure increased by 33% for privately insured transplants.

Limitations

The observations reported in this paper cannot be interpreted as evidence for the program’s impact.

Conclusions

Observed trends suggest plausibility of developing a hypothesis that Illinois Transplant Fund's introduction may have contributed to improvement in kidney transplantation access for Hispanic patients in Illinois, especially noncitizens, but cannot constitute evidence in support of or against this hypothesis. Future research should test whether the Illinois Transplant Fund improved access to kidney transplants for noncitizens with kidney failure.

Plain-Language Summary

Health policies regarding kidney transplant access for undocumented residents vary widely by state. The Illinois Transplant Fund (ITF) provides financial support for health insurance premiums, so undocumented patients with kidney failure in Illinois can qualify for a kidney transplant. In this study, we reported kidney transplant trends in Illinois before and after the creation of the ITF along with kidney transplant trends in the US overall and selected states that share similarities to Illinois.

Index Words: End stage kidney disease, health policy, Hispanic, kidney disease, kidney failure, noncitizens, private insurance, racial/ethnic disparities, residents, transplant, transplant waitlist, undocumented

Individuals with kidney failure require lifelong dialysis if they do not receive a transplant. Kidney transplantation improves survival and quality of life and is cost-effective relative to dialysis.1 For most patients, dialysis and transplant costs are covered by Medicare’s End Stage Renal Disease Program; however, many noncitizen patients—and particularly undocumented immigrant patients—do not qualify for Medicare, are excluded from the Affordable Care Act (ACA) provisions that expanded Medicaid coverage, and are often unable to pay the premium for private insurance coverage that can be obtained from the Marketplace established by the ACA.2

Illinois has an estimated 425,000 undocumented immigrants, and more than 300,000 are from Mexico, Central America, and South America.3 Although Hispanic residents are 18% of the state’s population, they represent 21% of individuals living with kidney failure in the state, and approximately 3% of patients with kidney failure are likely undocumented immigrants.4,5

Significant disparities in kidney transplantation rates for Hispanic patients with kidney failure have been documented, despite no significant difference in graft or patient survival between Hispanic and non-Hispanic transplant patients.6,7 One possible explanation for this disparity is access to health insurance coverage. In 2019, 26% of the Hispanic adult population under age 65 years in the United States was uninsured, which is substantially higher than the uninsured rate for non-Hispanic Black (14%) or non-Hispanic White (9%) populations.8

Due to the expensive immunosuppressive medications and ongoing medical care that are required after transplantation to prevent graft rejection, transplant programs often require patients to demonstrate their ability to pay for post-transplant care with either proof of health insurance coverage or personal financial resources. Thus, the lack of health insurance coverage has effectively created an insurmountable barrier to transplantation for many noncitizens living in the United States. Although the ACA created pathways for some noncitizens to obtain health insurance coverage, the large premiums and out-of-pocket cost sharing obligations are substantial barriers to access for those who are undocumented.9,10

To address this gap, the local organ donation organization Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donor Network created the Illinois Transplant Fund (ITF) as a new 501c3 organization in 2015. The ITF’s sole purpose is to facilitate access to organ transplantation by providing premium support for patients who live full-time in Illinois, are ineligible for public health insurance programs, and are unable to afford private health insurance plans through the Marketplace. In practice, ITF primarily provides premium support for undocumented individuals, the vast majority of whom are Hispanic in Illinois. The ITF covers 100% of monthly premiums for health insurance plans purchased through the Marketplace for at least 36 months after transplantation, gradually transitioning premiums to be the patient’s responsibility in subsequent years, similar to post-transplant care coverage by Medicare.11 In our previous qualitative work, we described how access to kidney transplants impacted ITF patients and identified additional barriers to care for this patient population.12

Our objective was to report trends in national- and state-level kidney failure and kidney transplant data before and after the ITF’s introduction to inform the development of a hypothesis to be tested in the future that the ITF has increased transplant incidence for Hispanic patients with kidney failure in Illinois, especially for noncitizen Hispanic patients.

Methods

Data

We retrieved publicly available data from 2 sources: Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) for the annual number of transplants and United States Renal Data System (USRDS) for annual kidney failure prevalent cases.13,14 Our analyses were limited to transplants for adults (aged 18 years or older), kidney only transplants (excluding kidney and pancreas combined transplants), transplants that took place in a transplant center, and transplants that occurred between 2009 and 2021, excluding the year 2015, as it was the year that the ITF was established.

Data on the annual numbers of transplants were obtained by race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic), year (2009 through 2021), and geographic area (by state and US overall). For Hispanic patients, we also obtained data on citizenship status (classified as US citizen, non-US citizen/US resident, and non-US citizen/non-US resident). OPTN’s classification of noncitizens included non-US citizen/US residents (ie, before 2012 called “resident alien”) and non-US citizen/non-US resident (ie, before 2012 called “non-resident alien”), excluding patients who traveled to the US primarily for transplant purposes. Undocumented immigrants are defined as non-US citizens whose primary residence is often in the US, in practice, but who do not have permission to live or work in the US and are at risk of deportation.2 Hence, the non-US citizen/non-US resident category of the OPTN citizenship status categories most likely includes undocumented immigrants. We also examined the average annual number of private health insurance-paid transplants by race/ethnicity, as patients supported by the ITF have private insurance due to lack of eligibility for public insurance.

Prevalent kidney failure cases from the USRDS were retrieved by race/ethnicity, year (2010 through 2020, first and last year of available data from the USRDS, as of this writing), and geographic area (by state and US overall) for adult patients for all dialysis modalities and all primary causes of kidney failure.

We selected 6 comparison states due to their sizable Hispanic populations and overall population size. Additionally, these states constituted examples of 1) having implemented policies and/or programs to provide standard-of-care kidney failure treatment coverage for undocumented immigrants (Arizona, California, Colorado, New York) and 2) providing no coverage for standard-of-care kidney failure treatment for undocumented immigrants (Florida, Texas) through Medicaid or other programs.15

The states with policies or programs that provide standard-of-care outpatient dialysis to undocumented immigrants use different means to do so (eg, emergency Medicaid stipulation based on the deferral to the individual states to define kidney failure as “medical emergency” as Arizona and Colorado do; state funding through Medicaid based on the stipulation of the Welfare Reform Act of 1996 that allows individual states to define what outpatient services they may offer to noncitizens as California, Illinois, and New York do).2,16,17 California also provides transplant coverage for undocumented immigrants under Medi-Cal (ie, California’s Medicaid program) by assigning undocumented immigrants Permanent Residence Under Color of Law (PRUCOL) status.18

In Illinois, outpatient dialysis is provided to undocumented immigrants through state funding, similar to California and New York. Furthermore, prior to ITF, through the Comprehensive Medicaid Legislation, Illinois was the only state in addition to California that provided transplant surgery to uninsured dialysis-dependent undocumented immigrants, but post-transplant care coverage was not available in this program.2,19 Therefore, to our knowledge, California and Illinois are the only 2 states in the US that provided transplant coverage to undocumented adult immigrants during the time frame examined here.

Data were managed and analyzed using Microsoft 365 Excel.20 This study was approved for nonhuman subject research classification by the Office of Research Affairs at the Rush University. Informed consent was not required, as this study used publicly available data aggregated to the calendar year that are available online through the websites of OPTN and USRDS.

Statistical Analysis

We examined the average annual number of transplants as a percentage of average annual kidney failure prevalence (ie, percent of cases transplanted) by race/ethnicity (overall and for privately insured patients only) and average annual number of transplants by citizenship (for Hispanic patients only) for pre- and post-ITF periods for 8 geographic areas: US, Illinois, and each of the 6 selected states.

We computed the unweighted average (mean) annual number of transplants for the pre-ITF (2010-2014) and post-ITF (2016-2020) periods and the unweighted average (mean) annual kidney failure prevalent cases for the pre-ITF and post-ITF periods. We calculated the pre- and post-ITF percent of cases transplanted by dividing the average annual number of transplants by the average annual kidney failure prevalent cases for the pre- and post-ITF periods and multiplying the results by 100. We then calculated both the absolute change and percent change in the percent of cases transplanted from the pre-ITF to post-ITF periods by race/ethnicity for all transplants and private insurance-paid transplants. The absolute change in the percent of cases transplanted was calculated by subtracting the pre-ITF percent of cases transplanted from the post-ITF percent of cases transplanted where the unit of measure of the resulting figure (ie, absolute change) is a percentage point. We computed the percent change in percent of cases transplanted by dividing the absolute change by the pre-ITF percent of cases transplanted and multiplying this result by 100. For adult Hispanic patients only, we also calculated average annual number of transplants for the pre- (2009 through 2014) and post-ITF (2016 through 2021, as data for 2021 were available) 6-year periods as described above by citizenship status and changes in this figure from the pre- to post-ITF period, analogously, as described above. We were unable to compute average annual prevalent kidney failure cases by citizenship status because these data were not available by citizenship status. Therefore, we were unable to scale or adjust the number of transplants with kidney failure prevalence as the denominator for comparisons based on citizenship status for Hispanic patients.

Results

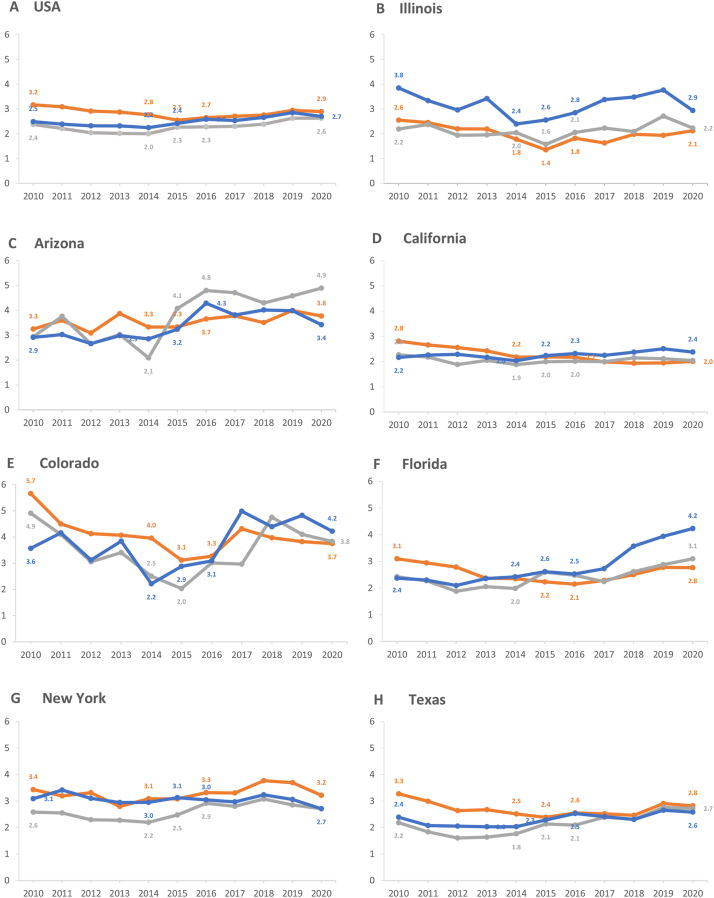

Changes in Percent of Cases Transplanted, by Race/Ethnicity

In Illinois, the percent of cases transplanted for Hispanic patients increased by 4% from the pre-ITF to post-ITF periods, compared to a decline of approximately 15% for non-Hispanic White and an increase of approximately 8% for non-Hispanic Black patients during the same period (Table 1, Fig 1). When comparing these numbers to other states, the largest percent change in the percent of cases transplanted for Hispanic patients was in Florida, with an increase of nearly 49% from the pre- to post-ITF periods. In the other 5 states, the changes in the percent of cases transplanted for Hispanic patients ranged from a decline of nearly 3% in New York to an increase of nearly 35% in Arizona and increased by nearly 14% in the US overall.

Table 1.

Changes in Percent of Cases Transplanted, by Race/Ethnicity

| Pre-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants | Pre-ITF Average Annual Kidney Failure Prevalent Cases | Pre-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted | Post-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants | Post-ITF Average Annual Kidney Failure Prevalent Cases | Post-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted | Change in Pre- to Post-ITF | % Change in Pre- to Post-ITF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 8,290 | 280,442 | 2.96 | 9,358 | 334,892 | 2.79 | -0.16 | -5.47 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4,139 | 195,102 | 2.12 | 5,568 | 227,475 | 2.45 | 0.33 | 15.38 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2,458 | 104,761 | 2.35 | 3,761 | 140,764 | 2.67 | 0.33 | 13.87 |

| Illinois | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 280 | 12,568 | 2.22 | 278 | 14,637 | 1.90 | -0.33 | -14.63 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 203 | 9,678 | 2.10 | 248 | 10,950 | 2.27 | 0.17 | 8.06 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 127 | 4,033 | 3.16 | 185 | 5,608 | 3.29 | 0.13 | 4.20 |

| Arizona | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 199 | 5,804 | 3.43 | 276 | 7,362 | 3.74 | 0.31 | 9.08 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 31 | 1,081 | 2.87 | 64 | 1,371 | 4.65 | 1.79 | 62.26 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 113 | 3,905 | 2.89 | 194 | 4,991 | 3.90 | 1.01 | 34.86 |

| California | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 602 | 23,957 | 2.51 | 581 | 29,014 | 2.00 | -0.51 | -20.23 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 231 | 11,308 | 2.04 | 260 | 12,601 | 2.06 | 0.02 | 0.84 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 702 | 32,279 | 2.17 | 1,027 | 43,406 | 2.37 | 0.19 | 8.75 |

| Colorado | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 168 | 3,781 | 4.44 | 178 | 4,643 | 3.83 | -0.61 | -13.70 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 27 | 752 | 3.56 | 33 | 877 | 3.74 | 0.17 | 4.89 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 56 | 1,678 | 3.36 | 90 | 2,087 | 4.32 | 0.96 | 28.61 |

| Florida | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 457 | 16,941 | 2.70 | 517 | 20,654 | 2.51 | -0.19 | -7.14 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 282 | 13,351 | 2.12 | 436 | 16,319 | 2.67 | 0.56 | 26.37 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 155 | 6,721 | 2.31 | 319 | 9,279 | 3.44 | 1.13 | 48.78 |

| New York | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 512 | 16,195 | 3.16 | 646 | 18,638 | 3.47 | 0.30 | 9.64 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 305 | 12,851 | 2.37 | 430 | 14,977 | 2.87 | 0.50 | 21.03 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 207 | 6,684 | 3.09 | 268 | 8,918 | 3.00 | -0.09 | -2.95 |

| Texas | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 420 | 15,011 | 2.80 | 553 | 20,792 | 2.66 | -0.14 | -5.00 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 266 | 14,787 | 1.80 | 434 | 17,616 | 2.46 | 0.66 | 36.99 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 493 | 23,391 | 2.11 | 753 | 30,122 | 2.50 | 0.39 | 18.51 |

-

1)“Pre-ITF Average” for the annual number of adult transplants is an unweighted average of annual number of adult transplants for 5 years from 2010 to 2014. “Post-ITF Average” for the annual number of adult transplants is an unweighted average of annual number of adult transplants for 5 years from 2016 to 2020. Source for annual number of transplants: Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network (OPTN).

-

2)“Pre-ITF Average” for the annual kidney failure prevalent adult cases is an unweighted average of annual kidney failure prevalent adult cases for 5 years from 2010 to 2014. “Post-ITF Average” for the annual kidney failure prevalent adult cases is an unweighted average of annual kidney failure prevalent adult cases for 5 years from 2016 to 2020. Source for annual kidney failure prevalent cases: United States Renal Data System (USRDS).

-

3)“Pre-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted” is computed by dividing the “Pre-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants” by the “Pre-ITF Average Annual Kidney Failure Prevalent Cases” and then multiplying the result by 100. “Post-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted” is computed by dividing the “Post-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants” by the “Post-ITF Average Annual Kidney Failure Prevalent Cases” and then multiplying the result by 100.

-

4)“Change in Pre- to Post-ITF” is computed by subtracting the “Pre-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted” from the “Post-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted” for each row of the table. For example, in IL, change experienced from the pre- to post-ITF periods in the “percent of Hispanic adult cases transplanted” is a change of 0.13 percentage points (ie, 3.29 – 3.16 = 0.13).

-

5)“% Change in Pre- to Post-ITF” is computed by dividing the “Change in Pre- to Post-ITF” by the “Pre-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted” and then multiplying the result by 100. For example, in IL, the % change experienced from the pre- to post-ITF periods for Hispanic adults is computed to be 4.20% (ie, [0.13 / 3.16] ∗ 100 = 4.20).

-

6)Computing the entries reported in the last 2 columns using the entries shown in the prior columns may yield slightly different numbers than those reported in the last 2 columns due to rounding.

Figure 1.

Changes in percent of cases transplanted by race/ethnicity in (A) USA, (B) Illinois, (C) Arizona, (D) California, (E) Colorado, (F) Florida, (G) New York, and (H) Texas. Orange line: non-Hispanic White; gray line: non-Hispanic Black; blue line; Hispanic. Source: Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, United States Renal Data System.

Changes in Number of Transplants for Hispanic Patients, by Citizenship Status

In Illinois, the average annual number of transplants for Hispanic patients increased by 28% for US citizens, 211% for non-US citizen/US residents, and 846% for non-US citizen/non-US residents from the pre- to post-ITF periods (Table 2). For the US overall, analogous figures for the changes in average annual number of transplants from the pre- to post-ITF periods were 48% for US citizens, 94% for non-US citizen/US residents, and 184% for non-US citizen/non-US residents. The percent changes in average annual number of transplants from the pre- to post-ITF periods for the comparison states ranged from 99% in California to 825% in Colorado for adult Hispanic non-US citizen/non-US resident patients. However, in all states except California, there were fewer than 4 transplants per year, on average, in the pre-ITF period.

Table 2.

Changes in Number of Transplants for Hispanic Patients, by Citizenship Status

| Pre-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants | Post-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants | Change in Pre- to Post-ITF | % Change in Pre- to Post-ITF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | ||||

| US Citizen | 1,872.67 | 2772.33 | 899.67 | 48.04 |

| Non-US Citizen | 553.67 | 1137.17 | 585.50 | 105.39 |

| US Resident | 483.83 | 939.00 | 455.17 | 94.08 |

| Non-US Resident | 69.83 | 198.17 | 128.33 | 183.77 |

| Illinois | ||||

| US Citizen | 107.33 | 137.50 | 30.17 | 28.11 |

| Non-US Citizen | 20.33 | 77.00 | 56.67 | 278.69 |

| US Resident | 18.17 | 56.50 | 38.33 | 211.01 |

| Non-US Resident | 2.17 | 20.50 | 18.33 | 846.15 |

| Arizona | ||||

| US Citizen | 90.00 | 158.17 | 68.17 | 75.74 |

| Non-US Citizen | 22.17 | 37.67 | 15.50 | 69.92 |

| US Resident | 21.67 | 34.67 | 13.00 | 60.00 |

| Non-US Resident | 0.50 | 3.00 | 2.50 | 500.00 |

| California | ||||

| US Citizen | 419.17 | 624.33 | 205.17 | 48.95 |

| Non-US Citizen | 266.83 | 428.50 | 161.67 | 60.59 |

| US Resident | 221.67 | 338.83 | 117.17 | 52.86 |

| Non-US Resident | 45.17 | 89.67 | 44.50 | 98.52 |

| Colorado | ||||

| US Citizen | 50.33 | 67.33 | 17.00 | 33.77 |

| Non-US Citizen | 4.00 | 21.67 | 17.67 | 441.67 |

| US Resident | 3.33 | 15.50 | 12.17 | 365.00 |

| Non-US Resident | 0.67 | 6.17 | 5.50 | 825.00 |

| Florida | ||||

| US Citizen | 129.83 | 248.83 | 119.00 | 91.66 |

| Non-US Citizen | 20.83 | 68.17 | 47.33 | 227.20 |

| US Resident | 19.00 | 62.17 | 43.17 | 227.19 |

| Non-US Resident | 1.83 | 6.00 | 4.17 | 227.27 |

| New York | ||||

| US Citizen | 162.67 | 202.67 | 40.00 | 24.59 |

| Non-US Citizen | 46.17 | 81.67 | 35.50 | 76.90 |

| US Resident | 42.50 | 70.50 | 28.00 | 65.88 |

| Non-US Resident | 3.67 | 11.17 | 7.50 | 204.55 |

| Texas | ||||

| US Citizen | 414.83 | 624.00 | 209.17 | 50.42 |

| Non-US Citizen | 73.33 | 169.83 | 96.50 | 131.59 |

| US Resident | 70.00 | 153.17 | 83.17 | 118.81 |

| Non-US Resident | 3.33 | 16.67 | 13.33 | 400.00 |

-

1)“Pre-ITF Average” for the annual number of Hispanic adult transplants is an unweighted average of annual number of Hispanic adult transplants for 6 years from 2009 to 2014. “Post-ITF Average” for the annual number of Hispanic adult transplants is an unweighted average of annual number of Hispanic adult transplants for 6 years from 2016 to 2021. Source for annual number of transplants: Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network (OPTN).

-

2)“Change in Pre- to Post-ITF” is computed by subtracting the “Pre-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants” from the “Post-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants” for each row of the table. For example, in IL, for the adult Hispanic non-US Citizen/non-US Resident group, the change experienced from the pre- to post-ITF periods in the “average annual number of transplants” is a change of 18.33 (ie, 20.50 – 2.17 = 18.33) transplants annually on average.

-

3)“% Change in Pre- to Post-ITF” is computed by dividing the “Change in Pre- to Post-ITF” by the “Pre-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants” and then multiplying the result by 100. For example, in IL, for the adult Hispanic non-US Citizen/non-US Resident group, the “% change” experienced from the pre- to post-ITF periods is computed to be 846.15% (ie, [18.33 / 2.17] ∗ 100 = 846.15).

-

4)Computing the entries reported in the last 2 columns using the entries shown in the prior columns may yield slightly different numbers than those reported in the last 2 columns due to rounding.

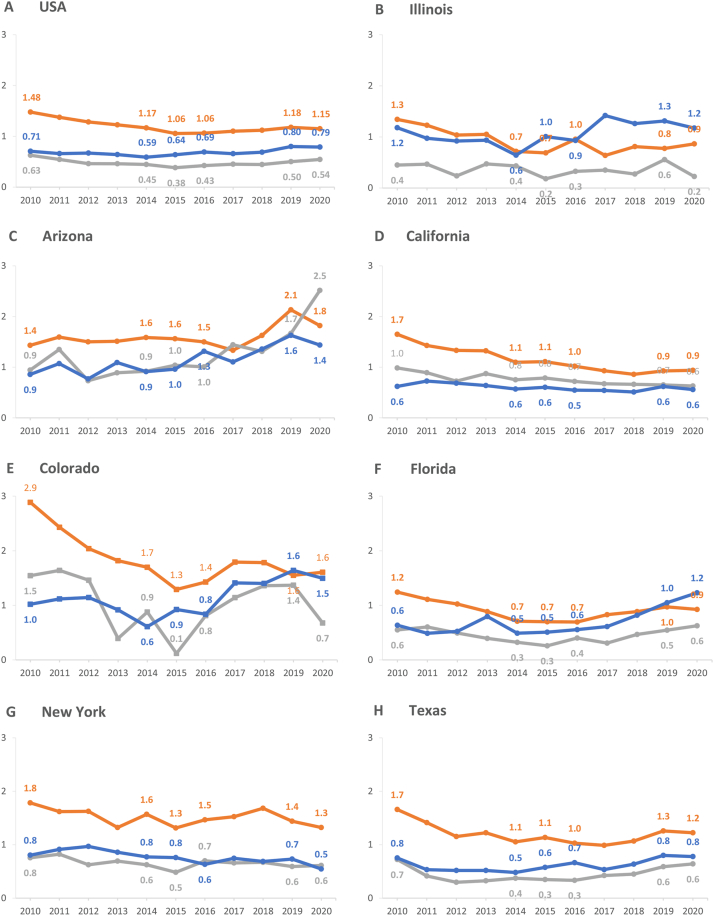

Changes in Percent of Private Insurance-Paid Cases Transplanted, by Race/Ethnicity

In Illinois, the percent of cases transplanted paid by private insurance increased by approximately 33% for Hispanic patients between the 2 periods (Table 3, Fig 2). During the same time periods, in Illinois, the corresponding figures for non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black patients exhibited declines of approximately 24% and 16%, respectively. Nationally, the change in the percent of cases transplanted that were paid by private insurance for Hispanic patients was approximately 12%. In the 6 comparison states, with the exceptions of California and New York that experienced declines of 14% and 22%, respectively, in the percent of private insurance-paid transplanted cases for Hispanic patients from pre- to post-ITF periods, all other states experienced substantial increases ranging from 24% in Texas to 48% in Florida, with Arizona (46%) and Colorado (44%) following Florida closely.

Table 3.

Changes in Percent of Private Insurance-Paid Cases Transplanted, by Race/Ethnicity

| Pre-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants | Pre-ITF Average Annual Kidney Failure Prevalent Cases | Pre-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted | Post-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants | Post-ITF Average Annual Kidney Failure Prevalent Cases | Post-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted | Change in Pre- to Post-ITF | % Change in Pre- to Post-ITF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3,650 | 280,442 | 1.30 | 3,763 | 334,892 | 1.12 | -0.18 | -13.65 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 986 | 195,102 | 0.51 | 1,080 | 227,475 | 0.47 | -0.03 | -6.07 |

| Hispanic | 682 | 104,761 | 0.65 | 1,025 | 140,764 | 0.73 | 0.08 | 11.87 |

| Illinois | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 134 | 12,568 | 1.07 | 118 | 14,637 | 0.81 | -0.26 | -24.26 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 40 | 9,678 | 0.41 | 38 | 10,950 | 0.35 | -0.06 | -15.61 |

| Hispanic | 37 | 4,033 | 0.92 | 69 | 5,608 | 1.22 | 0.31 | 33.33 |

| Arizona | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 89 | 5,804 | 1.53 | 125 | 7,362 | 1.69 | 0.17 | 10.88 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 10 | 1,081 | 0.96 | 22 | 1,371 | 1.61 | 0.64 | 66.78 |

| Hispanic | 37 | 3,905 | 0.94 | 69 | 4,991 | 1.37 | 0.43 | 45.87 |

| California | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 325 | 23,957 | 1.36 | 271 | 29,014 | 0.93 | -0.42 | -31.23 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 95 | 11,308 | 0.84 | 84 | 12,601 | 0.67 | -0.18 | -20.82 |

| Hispanic | 208 | 32,279 | 0.65 | 241 | 43,406 | 0.56 | -0.09 | -13.93 |

| Colorado | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 81 | 3,781 | 2.15 | 76 | 4,643 | 1.63 | -0.52 | -24.16 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 9 | 752 | 1.17 | 9 | 877 | 1.07 | -0.10 | -8.45 |

| Hispanic | 16 | 1,678 | 0.95 | 29 | 2,087 | 1.37 | 0.42 | 43.74 |

| Florida | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 167 | 16,941 | 0.99 | 179 | 20,654 | 0.86 | -0.12 | -12.28 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 62 | 13,351 | 0.47 | 77 | 16,319 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 1.22 |

| Hispanic | 39 | 6,721 | 0.59 | 81 | 9,279 | 0.87 | 0.28 | 48.17 |

| New York | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 256 | 16,195 | 1.58 | 277 | 18,638 | 1.49 | -0.09 | -5.91 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 90 | 12,851 | 0.70 | 97 | 14,977 | 0.64 | -0.06 | -8.10 |

| Hispanic | 58 | 6,684 | 0.86 | 60 | 8,918 | 0.67 | -0.19 | -22.45 |

| Texas | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 193 | 15,011 | 1.29 | 233 | 20,792 | 1.12 | -0.17 | -13.08 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 62 | 14,787 | 0.42 | 86 | 17,616 | 0.49 | 0.07 | 16.59 |

| Hispanic | 130 | 23,391 | 0.55 | 207 | 30,122 | 0.69 | 0.13 | 23.60 |

-

1)“Pre-ITF Average” for the annual number of private insurance-paid adult transplants is an unweighted average of annual number of private insurance-paid adult transplants for 5 years from 2010 to 2014. “Post-ITF Average” for the annual number of private insurance-paid adult transplants is an unweighted average of annual number of private insurance-paid adult transplants for 5 years from 2016 to 2020. Source for annual number of private insurance-paid transplants: Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network (OPTN).

-

2)“Pre-ITF Average” for the annual kidney failure prevalent adult cases is an unweighted average of annual adult kidney failure prevalence for 5 years from 2010 to 2014. “Post-ITF Average” for the annual kidney failure prevalent adult cases is an unweighted average of annual adult kidney failure prevalence for 5 years from 2016 to 2020. Source for annual kidney failure prevalent cases: United States Renal Data System (USRDS).

-

3)“Pre-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted” is computed by dividing the “Pre-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants” by the “Pre-ITF Average Annual Kidney Failure Prevalent Cases” and then multiplying the result by 100. “Post-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted” is computed by dividing the “Post-ITF Average Annual Number of Transplants” by the “Post-ITF Average Annual Kidney Failure Prevalent Cases” and then multiplying the result by 100.

-

4)“Change in Pre- to Post-ITF” is computed by subtracting the “Pre-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted” from the “Post-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted” for each row of the table. For example, in IL, the change experienced from the pre- to post-ITF periods in the “percent of Hispanic adult cases transplanted” is a change of 0.31 percentage points (ie, 1.22 – 0.92 = 0.31).

-

5)“% Change in Pre- to Post-ITF” is computed by dividing the “Change in Pre- to Post-ITF” by the “Pre-ITF Percent of Cases Transplanted” and then multiplying the result by 100. For example, in IL, the % change experienced from pre- to post-ITF periods for Hispanic adults is computed to be 33.33% (ie, [0.31 / 0.92] ∗ 100 = 33.33).

-

6)Computing the entries reported in the last 2 columns using the entries shown in the prior columns may yield slightly different numbers than those reported in the last 2 columns due to rounding.

Figure 2.

Changes in percent of private insurance-paid cases transplanted, by race/ethnicity in (A) USA, (B) Illinois, (C) Arizona, (D) California, (E) Colorado, (F) Florida, (G) New York, and (H) Texas. Orange line: non-Hispanic White; gray line: non-Hispanic Black; blue line; Hispanic. Source: Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, United States Renal Data System.

Discussion

In this study, we examined trends in the average annual number of transplants before and after the introduction of the ITF for the US, Illinois, and 6 selected states by race/ethnicity for all transplants and private insurance-paid transplants. In addition, we examined the average annual number of transplants during the pre- and post-ITF periods by citizenship status for Hispanic patients. This study is intended to be a hypothesis-forming rather than a hypothesis-exploring study. Therefore, observations reported in this paper cannot be interpreted as descriptive or causal evidence on the impact of the ITF. On the basis of the observations reported in the tables and figures, there is some evidence, albeit not strong, as discussed below, that it may be plausible to develop a hypothesis on the positive impact of the ITF and similar programs (given that 5 states now provide access to transplantation for noncitizens21) that would need to be examined in future studies with appropriate data that may enable rigorous study designs.

Although the percent of non-Hispanic White patients with kidney failure who received a transplant in Illinois declined in the post-ITF period compared to the pre-ITF period, we observed that the percent of cases transplanted increased for Hispanic patients. This may make one suspect that had it not been for the presence of the ITF, the percent of cases transplanted for Hispanic patients could have also declined, thereby, constituting a signal in support of generating a hypothesis to be examined in the future that the ITF may have had a positive impact. However, at the same time, in Illinois, the percent of cases transplanted for non-Hispanic Black patients also increased, and the increase was about twice the increase in percent of Hispanic cases transplanted. This may constitute a signal against the development of a hypothesis on the positive impact of the ITF. Because the ITF mainly affected Hispanic transplants, especially undocumented noncitizens, it cannot explain the increase in the percent of cases transplanted for non-Hispanic Black patients. This makes one suspect that other state- and/or nationwide factor(s), other than (or, in addition to) the ITF, may be associated with the increase in the percent of cases transplanted for Hispanic patients in Illinois that is/are also responsible for the increase experienced in the percent of cases transplanted for non-Hispanic Black patients. For example, other factors, such as the ACA and availability of insurance through the Marketplace, economic outlook, immigration from other countries and across the US states, and changes in kidney allocation strategies in 2014, may be associated with increases in the percent of cases transplanted for Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients. In addition, although the Medicaid expansions that took place in Illinois in 2020-2022 (ie, post-ITF) did not affect the study period examined in this study, their potential effects on transplant access in subsequent years should be examined in future research.

We compared the Illinois trends to those of New York, which did not have a program to cover noncitizen kidney failure patients’ transplant and post-transplant care expenses, but was similar to Illinois in many important aspects, eg, provided standard-of-care outpatient dialysis to undocumented immigrants, had a similar racial/ethnic composition, is located in a large metropolitan area that included most transplant centers, and had a similar climate and political composition. Although the changes in the percent of cases transplanted for non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black patients were larger in New York compared to Illinois, the percent of cases transplanted for Hispanic patients declined in New York, whereas it increased in Illinois, providing a signal supporting the generation of a hypothesis on the potential impact of the ITF. However, all other comparison states demonstrated dramatically larger increases (much larger than that of Illinois) in the percent of cases transplanted for Hispanic patients compared to non-Hispanic White patients (ie, Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, and Texas). In addition, in Illinois and some of the comparison states (Arizona, New York, and Texas), the increase in the percent of cases transplanted for non-Hispanic Black patients was considerably higher than the percent of cases transplanted for Hispanic patients. These may signal nationwide factors that may have positively affected Hispanic patient transplants in Illinois that are not attributable to the ITF, and these factors may have affected Illinois differently than other states.

We also examined changes in the average annual number of transplants for Hispanic noncitizens (separately for US residents and non-US residents) and Hispanic citizens within Illinois compared to other states because the ITF primarily increased access to transplantation for Hispanic undocumented patients who were likely to be included in the non-US citizen/non-US resident transplant case counts from the USRDS. The average annual number of transplants from the pre- to post-ITF period for Hispanic noncitizens relative to US citizens dramatically increased in all states. However, the change in the average annual number of transplants among non-US citizen/non-US resident Hispanic patients in Illinois from the pre- to post-ITF periods was the largest increase observed in the figure, following the change in Colorado while both states experienced more modest increases in the same figure among citizen Hispanic patients. Due to the lack of data needed for a denominator adjustment (ie, adult Hispanic kidney failure prevalent cases by citizenship status), the changes observed in this figure should be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, this observation may constitute another signal that generating a hypothesis on the positive impact of the ITF may be reasonable.

When we examined the percent of cases transplanted that were paid by private insurance by race/ethnicity, we found that the figure for Hispanic patients increased considerably from the pre- to post-ITF periods in Illinois and other comparison states, except in California and New York where declines were experienced. However, across all comparison states that experienced increases in the percent of cases transplanted for Hispanic patients from pre- to post-ITF periods, the increase in the percent of private insurance-paid cases transplanted in Illinois were more modest, second to the lowest, only outpacing that of Texas but falling substantially behind those of Arizona, Colorado, and Florida. This also may constitute support for nationwide and/or other statewide factors’ role dominating any role of the ITF in Illinois.

There are several limitations in our study that constitute reasons why the observations reported in this study cannot be construed as descriptive or causal evidence for the ITF’s impact, but only suggest that a hypothesis to be examined in the future studies on the positive impact of ITF on transplant prospects for Hispanic adult kidney failure patients, especially noncitizen patients, in Illinois is a reasonable one. First, other local and nationwide events and policy changes occurred during the study period that may have affected the percent of cases transplanted in Illinois somewhat differently than the other states in these comparisons in addition to confounding with any effect of the ITF. The kidney allocation changes may have had an outsized benefit for ITF patients as many had been on dialysis for 10 or more years and benefited from the new availability. At the national level, the UNOS implemented a new kidney allocation system, effective in December 2014. Research has demonstrated that racial/ethnic disparities decreased after the new allocation system was implemented due to increases in the number of transplants for non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients.22 Also, COVID-19’s impact on donations and transplants in 2020 has been well documented across the country; however, there are insufficient data to separate the pandemic’s effect from other changes.23 Additionally, we chose comparison states based on a variety of factors; however, policies and practices regarding kidney failure care—including transplants—for undocumented patients have been changing. In very recent years, New Mexico, Massachusetts, and Minnesota have also added provisions for statewide kidney transplants.21 Trends in these states should be examined as additional years of data become available.

Second, OPTN’s definition of a non-US citizen/non-US resident does not explicitly differentiate between noncitizens with legal status and those who do not have legal status (ie, undocumented).24 Therefore, we could not limit our analysis to the population effectively targeted by the ITF (ie, noncitizens who are full-time residents of Illinois without access to any subsidized health care—predominantly undocumented immigrants). Third, publicly available data from OPTN are not available at intervals shorter than a calendar year (eg, monthly, weekly) to enable more precise observation of time trends, which, to a certain extent, could help distinguish the confounding effects of the new kidney allocation system that was implemented at the end of 2014 and the introduction of the ITF in the first half of 2015. Fourth, the publicly available data used in our analysis are aggregated to the state level, preventing analyses that adjust for factors, such as age and comorbidities, that may be important correlates of transplant access and may vary substantially across race/ethnicity within a given state and across the states and by citizenship status. Finally, it must be noted that comparisons (eg, Hispanic citizens vs noncitizens, Illinois vs New York) that we made in interpreting our observations cannot be construed to represent counterfactuals as the implied control groups (ie, Hispanic citizens, New York) are far from perfect; therefore, even the same nationwide policy may have affected the implied control groups much differently than the treatment group.

Despite these limitations, the observations we described from the publicly available data suggest that it is reasonable to form a hypothesis to be examined in our future work, namely, that the introduction of the ITF may have positively impacted transplant prospects for noncitizen Hispanic kidney failure patients in Illinois, although the observations reported in this study may not be construed as evidence for the impact of the ITF. Illinois has provided avenues for undocumented patients to receive kidney transplants for nearly a decade, and additional states have begun to follow suit in recent years.21 Further research is needed to rigorously evaluate the impact of the ITF on transplant access and outcomes for noncitizen Hispanic patients with kidney failure and potential spillover effects on adult patients with kidney failure overall.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Zeynep Isgor, PhD, Tricia Johnson, PhD, Kevin Cmunt, and Brittney S. Lange-Maia, PhD, MPH

Authors’ Contributions

Study Conceptualization: KC, TJ, BLM, and ZI; study design: BLM, TJ, ZI, and KC; data acquisition: ZI; statistical analysis: ZI; data analysis/interpretation: TJ, BLM, ZI, and KC; drafting manuscript: ZI; reviewing and revising manuscript: TJ, BLM, ZI, and KC; supervising/mentorship: TJ and BLM. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

Funding was provided by the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donor Network to partially cover costs associated with research operations and salaries, including salary support for Zeynep Isgor and Brittney Lange-Maia.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Other Disclosures

One of the authors of the manuscript, Mr. Kevin Cmunt, was the President/CEO of the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donor Network and founded the Illinois Transplant Fund during his tenure in the position.

Data Sharing

The publicly available data used to generate the observations on trends presented in the tables and figures of this manuscript can be retrieved using interactive data tools available on the websites of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and United States Renal Data System.

Peer Review

Received February 20, 2023. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from the Statistical Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form August 7, 2023.

Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network’s database tools https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/build-advanced/

United States Renal Data System

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

References

- 1.Axelrod D.A., Schnitzler M.A., Xiao H., et al. An economic assessment of contemporary kidney transplant practice. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(5):1168–1176. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzolo K., Cervantes L. Immigration status and end-stage kidney disease: role of policy and access to care. Semin Dial. 2020;33(6):513–522. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unauthorized immigrant population, Profile of the unauthorized population: Illinois. Migration Policy Institute, 2019. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorized-immigrant-population/state/IL Accessed September 1, 2022.

- 4.Quick facts: Illinois population estimates. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/IL Accessed July 14, 2022.

- 5.Transplant waitlists, Kidney: Counts on list from the year 2020, Grouped by ethnicity, includes donation service areas ILCL, ILCR, ILIP. Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients [Internet] https://www.srtr.org/tools/donation-and-transplantation-analytics/ Accessed November 19, 2023.

- 6.Arce C.M., Goldstein B.A., Mitani A.A., et al. Differences in access to kidney transplantation between Hispanic and non-Hispanic Whites by geographic location in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(12):2149–2157. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01560213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuoka L., Alicuben E., Woo K., et al. Kidney transplantation in the Hispanic population. Clin Transplant. 2016;30(2):118–123. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Artiga S., Hill L., Orgera K., et al. Health coverage by race and ethnicity, 2010-2019. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity/# Accessed July 12, 2022.

- 9.Average Marketplace premiums by metal tier, 2018-2022. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/average-marketplace-premiums-by-metal-tier/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D Accessed July 13, 2022.

- 10.Branham D.K., Peters C., De Lew N., et al. Health insurance deductibles among HealthCare.gov enrollees, 2017- 2021. Issue Brief No. HP-2022-02. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/748153d5bd3291edef1fb5c6aa1edc3a/aspe-marketplace-deductibles.pdf Accessed July 14, 2022.

- 11.Kadatz M., Gill J.S., Gill J., et al. Economic evaluation of extending medicare immunosuppressive drug coverage for kidney transplant recipients in the current era. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(1):218–228. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019070646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gely Y.I., Esqueda-Medina M., Johnson T.J., et al. Experiences with kidney transplant among undocumented immigrants in Illinois: a qualitative study. Kidney Med. 2023;5(6) doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2023.100644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network (OPTN) Health Resources and Services Administration data reports. United States Department of Health & Human Services. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/build-advanced/ Accessed November 19, 2023.

- 14.United States Renal Data System, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) data query tool, ESRD prevalent count. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/strategic-plans-reports/usrds/data-query-tools/esrd-prevalent-count Accessed November 19, 2023.

- 15.Cervantes L., Mundo W., Powe N.R. The status of provision of standard outpatient dialysis for US undocumented immigrants with ESKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(8):1258–1260. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03460319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raghavan R. New opportunities for funding dialysis-dependent undocumented individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):370–375. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03680316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cervantes L., Johnson T., Hill A., et al. Offering better examples of dialysis care for immigrant, the Colorado example. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(10):1516–1518. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01190120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen J.I., Hercz D., Barba L.M., et al. Association of citizenship status with kidney transplantation in Medicaid patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(2):182–190. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lange-Maia B.S., Johnson T.J., Gely Y.I., et al. End stage kidney disease in non-citizen patients: epidemiology, treatment, and an update to policy in Illinois. J Immigr Minor Health. 2022;24(6):1557–1563. doi: 10.1007/s10903-021-01303-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Microsoft Excel. Microsoft 365. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel Accessed November 19, 2023.

- 21.Rizzolo K., Dubey M., Feldman K.E., et al. Access to kidney care for undocumented immigrants across the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176(6):877–879. doi: 10.7326/M23-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melanson T.A., Plantinga L.C., Basu M., et al. New kidney allocation system associated with increased rates of transplants among Black and Hispanic patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(6):1078–1085. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lentine K.L., Vest L.S., Schnitzler M.A., et al. Survey of US living kidney donation and transplantation practices in the COVID-19 era. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(11):1894–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guidance document for public comment – guidance for data collection regarding classification of citizenship status. Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network (OPTN), Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/xxojmrft/ahirc_guidance-document_citizenship-status-data-collection.pdf Accessed November 19, 2023.