Abstract

Self-inserted urethral foreign bodies are an unusual albeit well documented phenomena and cause of hospital presentation. When conservative non-operative managements fail, operative management is imperative to prevent further complications including infection, stones, diverticula, and fistula formation. Minimally invasive alternatives should be considered when cystoscopic access to the foreign body is mechanically difficult. Through this case presentation, we showcase a novel technique to consider when dealing with intraurethral foreign bodies - the use of thulium laser with rigid ureteroscope. We believe this to be the first documented case of successful intraurethral foreign body fragmentation using thulium laser.

1. Introduction

Self-inserted urethral foreign bodies are an unusual albeit well documented phenomena in medical literature with several case reports describing presentation and management. Removal of intra-urethral foreign bodies is required to help alleviate symptoms of pain and retention as well as prevent traumatic urethritis and prevent severe urinary tract infections1

Management is often achieved via manual removal with lubrication and gentle traction when appropriate. However, when conservative non-operative managements fail, operative management is imperative to prevent further complications including infection, stones, diverticula, and fistula formation. Operative management most commonly utilises cystoscopic techniques2 but laparoscopic3 and open procedures4 have also been required in other documented cases.

Minimally invasive alternatives should be considered when cystoscopic access to the foreign body is mechanically difficult. Through this case presentation, we showcase a novel technique to consider when dealing with intraurethral foreign bodies - the use of thulium laser with rigid ureteroscope. We believe this to be the first documented case of successful intraurethral foreign body fragmentation using thulium laser.

2. Clinical vignette

A 65-year-old gentleman presented to hospital after being unable to remove a foreign body inserted into the urethra. The foreign body appeared to be clear plastic tubing approximately 16 French in size. Initial management involved attempted removal using lignocaine gel and alligator clips after which approximately 6cm was able to be retracted before encountering resistance. Further investigation with CT-pelvis demonstrated knotting of the tubing within the prostatic urethra [Fig. 1]. Given these findings a clinical decision was made to attempt removal in theatres.

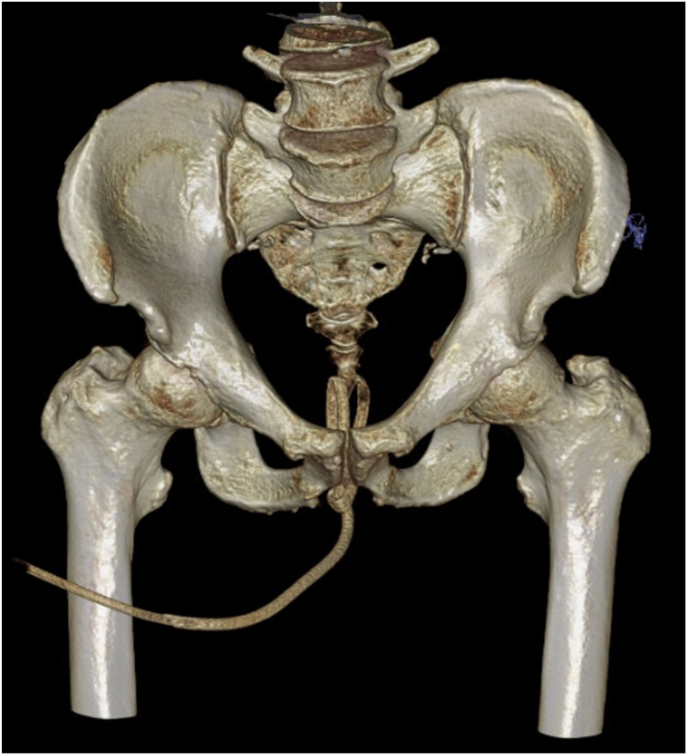

Fig. 1.

Virtual reconstruction from computed tomography of pelvis demonstrating urethral foreign body including knot which was located within prostatic and membranous urethra.

During pre-operative planning and assessment for emergency surgery it was identified that the patient had previous moderate-severe pulmonary hypertension with right ventricle dysfunction with concomitant infective exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease making the patient a high-risk anaesthetic candidate, thus an endoscopic approach was preferred. Additionally, an increased risk of bleeding was noted due to direct-acting oral anticoagulant use for atrial fibrillation.

In theatres, a flexible cystoscope was unable to be placed next to the foreign body, thus a rigid ureteroscope was inserted and a thulium laser was used to fragment the end and knot of the foreign body within the urethra at 120nM. However, complete fragmentation was unable to be achieved within the membranous and prostatic urethra due to difficulties angulating the laser appropriately thus a suture was tied to the distal and extracorporeal end of the foreign body and the entire tubing was required to be moved into the bladder for further fragmentation and safe removal. Much of the tubing from the foreign body was then able to be removed however with increasing haematuria from mucosa irritation and to avoid extended procedure time in a comorbid patient the knot had to be left within the bladder and to be removed as a second staged procedure due to haematuria.

On return to theatres four days later after haematuria had settled, the remainder of the plastic tubing was fragmented using 350nM thulium laser and pieces retrieved using cold cup biopsy forceps [Fig. 2]. Post-operative recovery was unremarkable, and the patient was discharged the same day with a urinary indwelling-catheter insitu for outpatient trial of void. When removed the foreign body appeared to be consistent with oxygen tubing [Fig. 3].

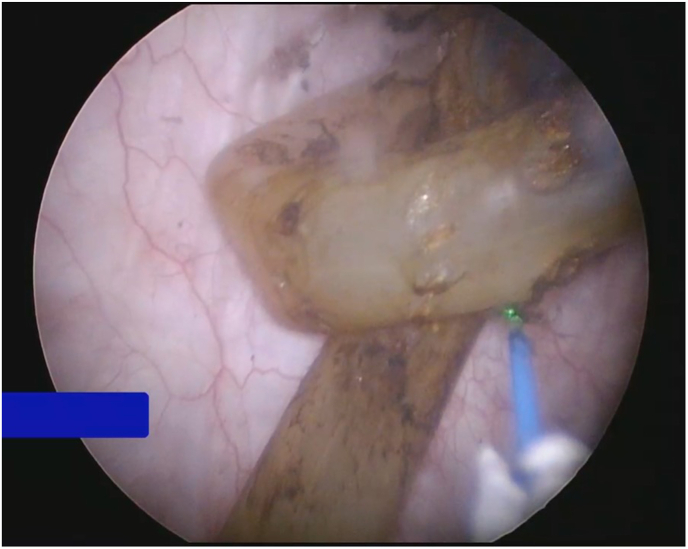

Fig. 2.

Intra-operative image of knotted foreign body within bladder being fragmented with thulium laser.

Fig. 3.

Post-operative photo of foreign body removed, postulated to be consistent in appearance with oxygen tubing.

Unfortunately, the patient declined follow up with the urology service and the treating team were unable to ascertain development of urethral stricture post-operatively. However, on representation to the emergency department for an unrelated complaint 3 months post-operatively he did not report any lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of urethral stricture formation.

3. Discussion

Long flexible foreign bodies tend to knot in the bladder preventing spontaneous self-expulsion as well as making removal using simple traction techniques unsuccessful.5 In these cases, imminent operative management is imperative to prevent further complications including infection, stones, diverticula, and fistula formation.2 If endoscopic intervention fails consideration of open approaches including urethrotomy or cystotomy may be required.2

Holmium lasers have also been used for fragmentation of ceramic intravesical foreign bodies that are too large to be removed using forceps or washout techniques.6 In comparison, thulium laser uses continuous instead of pulsed waves which allow for greater control in interaction with tissue.7 In practice, prospective trials have found that there is decreased bleeding risks when using thulium laser compared to holmium laser for both laser enucleation of prostate8 and for laser lithotripsy of upper tract urolithiasis.9 In this case presentation due to the increased bleeding risk a decision was made to attempt fragmentation using thulium laser over holmium. However, given this is an uncommon surgical presentation there is no literature at current comparing laser technologies for this such purpose.

Other techniques for removal of foreign bodies include use of paediatric working instruments10 as well as open cystolithotomy.4 At the treating centre paediatric cystoscope and associated instruments were not readily available and given the patient's comorbid background a minimally invasive method was preferred for shorter anaesthetic duration.

This is the first recorded case of using thulium laser technology to help facilitate removal of urethral foreign body. Thulium laser can be considered a viable technique to fragment foreign bodies within the urinary tract when traditional methods of removal are not viable.

Funding

Nil external funding was received in this research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Paul Kim: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. James Kovacic: Writing – review & editing. Andrew Shepherd: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Ankur Dhar: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and nil external funding was received in this research.

References

- 1.Palmer C.J., Houlihan M., Psutka S.P., Ellis K.A., Vidal P., Hollowell C.M. Urethral foreign bodies: clinical presentation and management. Urology. 2016 Nov;97:257–260. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.05.045. Epub 2016 May 31. PMID: 27261182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Ophoven A., deKernion J.B. Clinical management of foreign bodies of the genitourinary tract. J Urol. 2000 Aug;164(2):274–287. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200008000-00003. PMID: 10893567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X., Wu X., Liu W., et al. Laparoscopic extraction of a urethral self-inflicted needle from pelvis in a boy: a case report. Front Pediatr. 2023 Jun 23;11 doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1207247. PMID: 37425271; PMCID: PMC10326616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maqueda Vocos M., Bonanno N.A., Blas L., Villasante N. Open surgery for urethral foreign body. Medicina (B Aires) 2022;82(5):791–793. English. PMID: 36220042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quin G., McCarthy G. Self insertion of urethral foreign bodies. Emerg Med J : EMJ. 2000;17(3) doi: 10.1136/emj.17.3.231. 231–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castellani D., Gasparri L., Claudini R., Pavia M.P., Branchi A., Dellabella M. Iatrogenic foreign body in urinary bladder: holmium laser vs. Ceramic, and the winner is…. Int Braz J Urol. 2019 Jul-Aug;45(4):853. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2018.0229. PMID: 30735339; PMCID: PMC6837588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zarrabi A., Gross A.J. The evolution of lasers in urology. Ther Adv Urol. 2011 Apr;3(2):81–89. doi: 10.1177/1756287211400494.PMID:21869908. PMCID: PMC3150070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartung F.O., Kowalewski K.F., von Hardenberg J., et al. Holmium versus thulium laser enucleation of the prostate: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Urol Focus. 2022 Mar;8(2):545–554. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2021.03.024. Epub 2021 Apr 8. PMID: 33840611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delbarre B., Baowaidan F., Culty T., et al. Prospective comparison of thulium and holmium laser lithotripsy for the treatment of upper urinary tract lithiasis. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2023 Mar 21;51:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.euros.2023.02.012. PMID: 37187726; PMCID: PMC10175723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gobbi D., Midrio P., Gamba P. Instrumentation for minimally invasive surgery in pediatric urology. Transl Pediatr. 2016 Oct;5(4):186–204. doi: 10.21037/tp.2016.10.07. PMID: 27867840; PMCID: PMC5107385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]