Abstract

Escherichia coli K-12 WaaO (formerly known as RfaI) is a nonprocessive α-1,3 glucosyltransferase, involved in the synthesis of the R core of lipopolysaccharide. By comparing the amino acid sequence of WaaO with those of 11 homologous α-glycosyltransferases, four strictly conserved regions, I, II, III, and IV, were identified. Since functionally related transferases are predicted to have a similar architecture in the catalytic sites, it is assumed that these four regions are directly involved in the formation of α-glycosidic linkage from α-linked nucleotide diphospho-sugar donor. Hydrophobic cluster analysis revealed a conserved domain at the N termini of these α-glycosyltransferases. This domain was similar to that previously reported for β-glycosyltransferases. Thus, this domain is likely to be involved in the formation of β-glycosidic linkage between the donor sugar and the enzyme at the first step of the reaction. Site-directed mutagenesis analysis of E. coli K-12 WaaO revealed four critical amino acid residues.

Glycosyltransferases catalyze the transfer of sugar residues from an activated donor substrate to an acceptor molecule. There are at least two types of glycosyltransferases: (i) processive enzymes that transfer multiple sugar residues to an acceptor and (ii) nonprocessive enzymes that catalyze the transfer of a single sugar residue to a specific acceptor (26). The reactions catalyzed by nonprocessive transferases are highly specific with respect to the structure of substrates, such as the sugar residue to be transferred, the acceptor, and the linkage to be formed.

The structure of Escherichia coli K-12 lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been precisely determined (2, 13, 16). The outer core region of bacterial LPS consists of a nonrepeating series of sugar residues, and the oligosaccharide structure of the core region is synthesized by the sequential action of a series of nonprocessive glycosyltransferases, in which each enzyme catalyzes the transfer of a single specific sugar residue from a nucleotide sugar precursor to the nonreducing end of the polysaccharide chain (24). In E. coli K-12, these glycosyltransferases are encoded by the waa loci (based on the proposal made by Reeves et al. [22] and Heinrichs et al. [9], a new nomenclature was used to replace the rfa designations) at 81 min of the chromosome (21, 23). E. coli K-12 WaaO, which is encoded by waaO, is a nonprocessive α-1,3-glucosyltransferase that is involved in the addition of glucose II residue to glucose I of R core.

In this paper, we describe the conserved sequence regions which are potential constituents of the catalytic sites of WaaO and the amino acid residues critical for the catalytic function.

(A preliminary account of this study was presented at the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Miami Beach, Fla., 1997 [27].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. All strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Difco) or LB agar, which contains 1.4% agar (Difco). The growth temperature was 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Properties or genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli K-12 strains | ||

| C600 | hsdR (rK− mK+) supE44 thi thr-1 leuB6 lacY1 tonA21 | T. Mizuno |

| C600ΔO | ΔwaaORYZU of C600 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHSG399 | Cmr; cloning vector | Takara Shuzo Co. |

| pHSGwaaO | Cmr; cloned gene, waaO (1.5-kb NspV-NheI fragment) | This study |

| pINT007-p | Kmrori(Ts); integration vector | T. Mizuno |

| pSI30 | Apr Tcrori(Ts) | S. Ichihara |

| pINTTca | Tcrori(Ts); integration vector | This study |

| pINTSFwaaO | Tcrori(Ts); cloned gene, part of waaO (0.5-kb fragment amplified by PCR) | This study |

Similar to pINT007-p, but with the Kmr gene deleted and a 1.4-kb EcoRI fragment containing the tetracycline resistance gene of pSI30 introduced.

Production of a WaaO-deficient mutant strain.

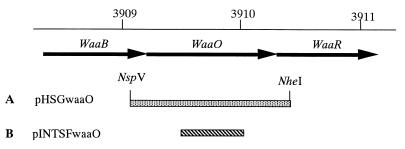

The temperature-sensitive plasmid pINTTc was used to produce a WaaO-deficient mutant strain. A portion of the waaO gene was amplified by PCR with Taq polymerase with the following primers which contain the restriction sites indicated: nucleotides 85 to 105 in waaO, SacI site underlined (5′-CTCGAGCTCCTGGACATCGCTTATGGAAC-3′); and nucleotides 614 to 595 in waaO, KpnI site underlined (5′-CACGGTACCGCAATAGCTCGTGCAGAAC-3′) (Fig. 1). The PCR product was cloned into the multicloning site of pINTTc. The resulting plasmid, designated pINTSFwaaO, was used to transform E. coli K-12 C600, and a plasmid integration mutant carrying a deletion of the chromosomal waaO gene resulting from homologous recombination was isolated, as described previously (19). This WaaO-deficient mutant was designated C600ΔO.

FIG. 1.

Physical map of the portion of the waa region and plasmids used in this study. (A) An NspV-NheI fragment containing the entire waaO gene was cloned into the expression vector pHSG399. (B) A portion of the waaO gene amplified by PCR was cloned into the plasmid pINTTc, and a waaO deletion mutant was constructed by plasmid integration.

Cloning of the waaO gene and site-directed mutagenesis.

We constructed a plasmid, pHSGwaaO, that carries the waaO gene, the expression of which was controlled by the lacZ promoter (Fig. 1).

Aspartic acid residues 131, 133, 220, and 222 of WaaO were individually converted to asparagine; serine residues 184 and 293 were converted to cysteine; and tyrosine residues 181, 239, and 260 and the threonine residue 270 were converted to alanine, as described below.

The site-directed mutations of the waaO gene were created by the method of Kunkel, as described in the work of Sambrook et al. (25), with the Mutan-K kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). The oligonucleotides used for mutagenesis are listed in Table 2. All of the mutated DNA sequences were verified entirely by sequencing, with a Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit with a 373A Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). E. coli C600ΔO cells were used as a host to express wild-type and mutated WaaO.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used for site-directed mutagenesis

| Amino acid substitution | Oligonucleotide containing altered codona |

|---|---|

| D131N | 5′-ATCTGCATTCAGATAAAG-3′ |

| D133N | 5′-CAAATGATATTTGCATCCAG-3′ |

| Y181A | 5′-GAGTTAAAGGCACCTTTAGC-3′ |

| S184C | 5′-AAAAACCGCAGTTAAAGTAACC-3′ |

| D220N | 5′-ATCCTGGTTAGGGTGTGTTA-3′ |

| D222N | 5′-AACACATTTTGGTCAGGGTG-3′ |

| Y239A | 5′-TGGGTGTTAGCTTTAATATC-3′ |

| Y266A | 5′-GCCCGATAGCATGGATAAAA-3′ |

| T270A | 5′-CAGGGCTTGGCTGGCCCGAT-3′ |

| S293C | 5′-CTTCCATGGACAAGCATTTTTTGC-3′ |

Mutated bases are underlined.

Extraction of LPS.

Bacteria for LPS analysis were grown overnight in 1.5 ml of LB broth. The LPS samples were extracted by the phenol-water method (29, 30) with some modifications. Bacterial cells were precipitated by centrifugation and suspended in 0.5 ml of physiologic saline. Cell suspensions were mixed well with 0.5 ml of 90% phenol at room temperature. After centrifugation, the aqueous phase containing the LPS fraction was transferred into a new tube and mixed with 1 ml of absolute ethanol. The LPS was precipitated by centrifugation, and the precipitate was washed with 70% ethanol before being air dried for further analysis.

Gel electrophoresis of LPS.

LPS samples were separated on a 15% polyacrylamide gel containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in Tris-glycine buffer and visualized by silver staining as previously described (30).

Analysis of the sugar components of LPS.

LPS preparations were hydrolyzed in 1 N HCl for 6 h, and quantitative analyses of glucose and galactose in the hydrolysates were carried out by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described previously (14, 15). Borate buffer (0.6 M, pH 7.3) was used for elution with a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, and the neutral sugar components were separated on an anion-exchange column (TSKgel Sugar AXI; Tosoh Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). For the postcolumn labeling reaction, eluates were mixed with a reagent solution prepared from a 1% aqueous solution of 2-cyanoacetamide and borate buffer (0.6 M, pH 10.5), before being heated to 100°C. The amounts of the sugar components were determined by the absorbance of the product at 276 nm. The glucose content in LPS was expressed as the ratio of glucose to galactose.

RESULTS

Glycosyltransferase activity of WaaO.

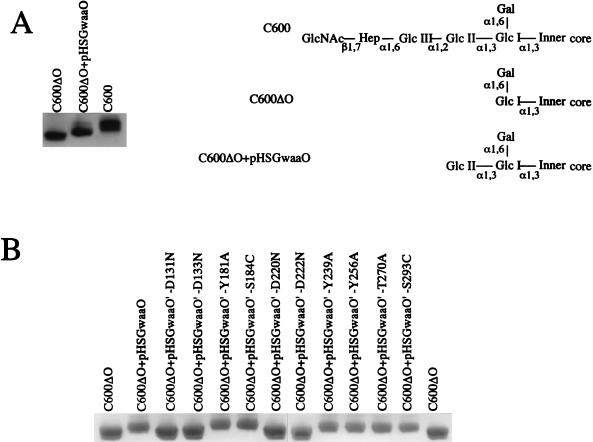

The catalytic function of E. coli K-12 WaaO was examined by a complementation study employing a chromosomal waaO deletion mutant, C600ΔO. The silver-stained profiles of the LPS preparations on SDS-polyacrylamide gels after electrophoresis are shown in Fig. 2. The LPS of C600ΔO exhibited a distinguishable band with greater mobility than that of C600, indicating that the function of WaaO was abolished by the inactivation insertion in the waaO gene in C600ΔO. As the transcription was blocked at waaO, the expression of transferases encoded downstream from waaO was also abolished. The difference in the migration distances between the LPSs of C600 and C600ΔO corresponded to the lack of four distal sugar residues in the polysaccharide chain of the LPS, previously demonstrated by Hitchcock and Brown (12). This was confirmed by HPLC analysis of the sugar components (see Table 4), since the ratio of glucose to galactose in C600ΔO was reduced to about one-third that of C600. When the waaO gene on pHSGwaaO was expressed in C600ΔO, the LPS band in the gel migrated to a position intermediate between that of LPS from C600 and LPS from C600ΔO, because of the addition of a single glucose residue. HPLC analysis also showed that the glucose content of LPS from C600ΔO harboring pHSGwaaO was restored to about two-thirds that of C600. In the LPS of C600ΔO(pHSGwaaO), there is a minor slow-migrating band above the prominent band. The chemical basis of this appearance is not evident, however, as Pradel et al. (21) noted; if the acceptor stringency of WaaO is not very high, the protein which is highly produced from the multicopy plasmid pHSGwaaO may recognize at lower efficiency the WaaO-mediated LPS core as an acceptor to generate the less abundant, more slowly migrating band. This might be reflected in the observation that the ratio of glucose to galactose was 2.3:1 rather than 2:1.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of waaO-mediated glycosyl transfer on LPS. Strains and plasmids are indicated above each lane. (A) The effect of waaO gene inactivation on the migration of LPS and schematic representation of the structures of the R-core region. (B) Electorophoretic profiles of LPS from E. coli C600ΔO complemented with plasmids carrying mutated waaO genes.

TABLE 4.

HPLC analysis of the neutral hexose composition of LPS

| Strain | nmol of sugar

|

Glucose/ galactose ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Galactose | ||

| C600 | 39.7 | 13.5 | 2.9 |

| C600ΔO | 10.5 | 10.4 | 1.1 |

| C600ΔO plus waaO | 24.8 | 10.8 | 2.3 |

| C600ΔO harboring a mutated waaO gene | |||

| D131N | 6.4 | 7.1 | 0.96 |

| D133N | 6.6 | 6.5 | 1.1 |

| Y181A | 8.4 | 4.1 | 2.2 |

| S184C | 18.0 | 5.8 | 3.4 |

| D220N | 3.5 | 3.4 | 1.1 |

| D222N | 4.2 | 4.6 | 0.99 |

| Y239A | 9.5 | 5.6 | 1.8 |

| Y256A | 5.0 | 2.8 | 1.9 |

| T270A | 9.7 | 2.8 | 3.7 |

| S293C | 5.7 | 3.7 | 1.7 |

Sequence analyses of WaaO and its homologs.

Searches of sequence databases (GenBank and SwissProt) showed significant similarities between WaaO and the 11 proteins listed in Table 3. Several of the proteins were previously classified as WaaIJ-related glycosyltransferases, based on amino acid sequence similarities, by Heinrichs et al. (9). These glycosyltransferases, except for several putative glycosyltransferases, catalyze the formation of stereochemically similar glycosidic linkages, and their substrates are structurally related.

TABLE 3.

Properties of glycosyltransferases which have homology with WaaO of E. coli K-12

| Protein | Putative or known activity | Organism | Accession no. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WaaO | Adds Glc α1→3 to Glu; involved in LPS synthesis | E. coli K-12 | P27128 | 21 |

| WaaR | Adds Glu α1→2 to Glu; involved in LPS synthesis | E. coli K-12 | P27129 | 21 |

| WaaI | Adds Gal α1→3 to Glu; involved in LPS synthesis | Salmonella typhimurium | P19816 | 17 |

| WaaJ | Adds Glc α1→3 to Gal; involved in LPS synthesis | S. typhimurium | P19817 | 17 |

| Ipa-12d | Putative glycosyltransferase identified by similarity to E. coli WaaO and S. typhimurium WaaI | Bacillus subtilis | P25148 | 7 |

| LgtA | Putative glycosyltransferase identified by similarity to E. coli WaaO and S. typhimurium WaaI | Rhizobium leguminosarum | X94963 | Unpublished |

| DUGT | Adds glucose to malfolded glycoprotein | Drosophila melanogaster | U20554 | 20 |

| GM12 | Adds Glu α1→2 to oligosaccharide in the Golgi apparatus | Schizosaccharomyces pombe | Q09174 | 4 |

| LgtCa | Adds Gal α1→4 to Gal; involved in lipooligosaccharide synthesis | Neisseria gonorrhoeae | U14554 | 8 |

| LgtCa | Putative glycosyltransferase identified by similarity to LgtC of N. gonorrhoeae | Neisseria meningitidis | U65788 | Unpublished |

| LgtCa | Putative glycosyltransferase identified by similarity to LgtC of N. gonorrhoeae | Haemophilus influenzae | U32711 | 5 |

| LpcAa | Adds Gal α1→6 to Man; involved in LPS synthesis | Rhizobium leguminosarum | X94963 | 1 |

Protein classified previously as WaaIJ-related glycosyltransferase, based on amino acid sequence similarities, by Heinrichs et al. (9).

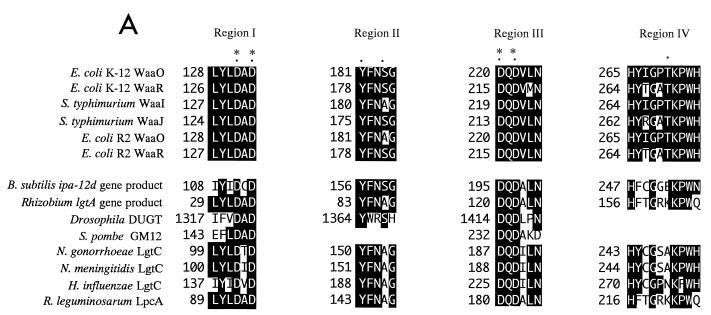

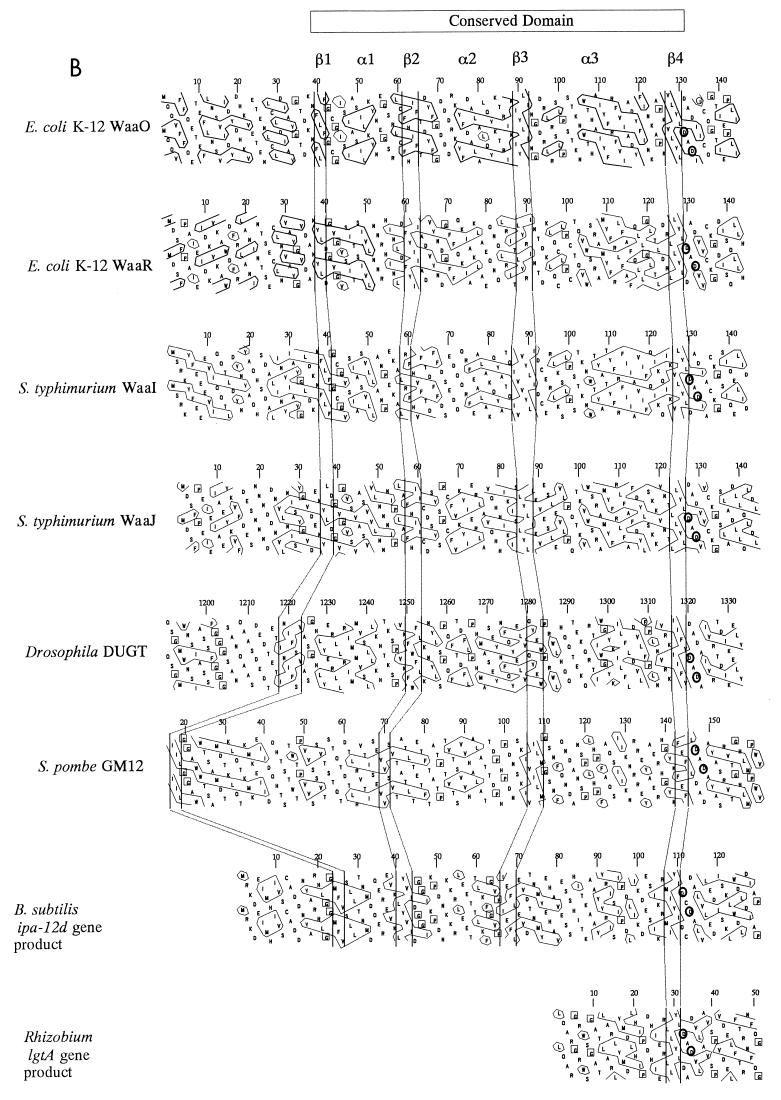

As Fig. 3A shows, these proteins share the four highly conserved regions (region I: residues 128 to 133 of E. coli K-12 WaaO; region II: residues 181 to 185; region III: residues 220 to 225; and region IV: residues 265 to 274). As Saxena et al. reported previously (26), glycosyltransferases which catalyze the formation of glycosidic linkages with the same stereochemistry and with structurally related substrates are predicted to have similar three-dimensional architectures in their catalytic and binding domains. Hydrophobic cluster analysis (HCA) is a powerful sequence comparison method which can detect such three-dimensional similarities in proteins (6). This method plots the two-dimensional patterns of protein sequences and allows visual comparison and detection of conserved structural features. Using HCA, we identified a conserved domain in all the sequences examined (Fig. 3B). This conserved domain is characterized by a series of vertical hydrophobic clusters typical of β-strands, alternating with clusters characteristic of α-helices. Region I was located at the C-terminal end of this domain. Interestingly, this domain was similar to that reported for the β-glycosyltransferases (26).

FIG. 3.

(A) Four conserved regions of E. coli K-12 WaaO and related proteins. Alignment was created by the GENETYX-Homoan program (Software Development Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Conserved residues are boxed in black. The dots indicate the altered residues. Asterisks indicate the residues whose replacement abolished the enzymatic activity of WaaO. (B) Alignment of HCA plots of E. coli WaaO and other homologous proteins. The plots were generated with the HCA-Plot program (Doriane Informatique, Le Chesnay, France). The vertical lines indicate the structurally conserved features. Conserved Asp residues are circled.

Effect of amino acid substitution on the catalytic activity of WaaO.

To determine the amino acid residues which are critical for the reaction catalyzed by WaaO, we examined the effect of mutating these strictly conserved amino acid residues on glycosyltransferase activity. Amino acid residues which had a side chain with the appropriate reactivity (31) to catalyze an acid-base reaction similar to that catalyzed by glycosyl hydrolases (28) were selected for mutagenesis. Each mutated WaaO protein was expressed in C600ΔO. The activity of each mutated enzyme was assayed by analysis of the end product, LPS. The mutated enzymes were characterized in terms of their ability to transfer glucose to the R-core polysaccharide by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and HPLC analysis.

SDS-PAGE analysis demonstrated that the electrophoresis profiles of LPS from C600ΔO harboring pHSGwaaO-D131N, -D133N, -D220N, or -D222N were the same as that of C600ΔO. Therefore, the replacement of the aspartate residue at position 131, 133, 220, or 222 with asparagine completely abolished the enzymatic activity of WaaO, whereas other mutations such as the replacement of serine at 184 or 293 with cysteine or of tyrosine residues at 181, 239, or 260 or of threonine 270 with alanine had no effect on transferase activity (Fig. 2).

HPLC analysis confirmed the above results. As Table 4 indicates, the sugar composition of LPS derived from C600ΔO harboring pHSGwaaO-D131N, -D133N, -D220N, or -D222N was the same as that of C600ΔO LPS, whereas the other site-directed mutations of the waaO gene changed the glucose content of C600ΔO LPS.

The four Asp residues, the replacement of which abolished the enzymatic activity of WaaO, are constituents of the pair of unique DXD motifs in regions I and III.

DISCUSSION

To date, very little is known about anabolic glycosyl transfer reactions involved in the formation of polysaccharides. However, it has been predicted that this type of reaction would mechanistically be the reverse of glycosyl hydrolysis (28). Based on the extensively characterized mechanism of glycosyl hydrolase, a mechanism for glycosyl transfer has been proposed (26, 28). The mechanism of the β-glycosyl transfer reaction involves a single nucleophilic substitution at the anomeric center. This catalytic mechanism involves a single acidic active-site amino acid that acts as a nucleophile (26, 28). Previous studies of glycosyltransferases have demonstrated that there is often insufficient sequence similarity for functional predictions with traditional sequence alignments. However, it is suggested that certain conserved regions may be required for a common function between the various transferases (26). HCA is a powerful sequence comparison method which can clearly detect three-dimensional similarities in proteins showing very limited sequence relatedness (6). This method also has enabled the prediction of catalytic residues in a number of glycosyl hydrolases by the identification of invariant amino acid residues with appropriate side chain reactivity (10, 11). Using HCA, Saxena et al. (26) compared 13 β-glycosyltransferases and identified a conserved domain A that should be directly involved in the formation of a single β-glycosidic linkage from α-linked nucleotide diphospho-sugar donors. They characterized the Asp residue at the C-terminal end of this domain as a catalytic residue. Keenleyside and Whitfield identified 32 proteins, in addition to the 13 originally described by Saxena et al., that possess this conserved domain (18).

On the other hand, α-glycosyltransferases retain the anomeric configuration at the reaction center via a two-step mechanism (26, 28). This mechanism involves two acidic active-site amino acids, one acting as a nucleophile and the other acting as a general base. The first step of the nonprocessive α-glycosyl transfer reaction involves the attack of an enzymatic nucleophile on the anomeric center of the sugar, leading to formation of a β-glycosyl enzyme intermediate. The distance between the catalytic nucleophile and the anomeric carbon of UDP-hexose is smaller than that in β-glycosyltransferases, where a larger distance is required to accommodate the acceptor molecule between the catalytic base and the anomeric carbon. However, the catalytic mechanism of the first step of α-glycosyl transfer reaction includes the formation of β-glycosidic linkage, and this action is similar to that of β-glycosyltransferase. Thus, it is to be expected that nonprocessive α-glycosyltransferases possess the domain previously identified in the β-glycosyltransferases by Saxena et al. (26). The conserved domain of WaaO and other homologous proteins was similar to that of β-glycosyltransferases. The DXD motif in region I was located at the C-terminal end of the domain. This DXD motif was also conserved in almost all β-glycosyltransferases described by Saxena et al. (26) and Keenleyside and Whitfield (18). This motif includes a conserved Asp residue previously characterized as a possible catalytic residue by Saxena et al. (26). This motif falls in a loop at the C-terminal ends of predicted strands, a position frequently observed for catalytic residues (31). Taken together, the conserved domain and region I are likely to be important for the formation of β-glycosidic linkage between donor sugar and the enzyme.

Regions II, III, and IV are present in only WaaO and the homologous glycosyltransferases. Given their common activities and the conservation of these regions, it is likely that these regions represent at least part of the catalytic or binding sites and play a crucial role in generating α-glycosidic linkage between donor sugar and acceptor molecule.

The results of site-directed mutagenesis analysis of WaaO indicate that Asp-131 and -133 (DXD motif in region I) and Asp-220 and -222 (DXD motif in region III) may play a crucial role in the catalytic function of E. coli K-12 WaaO protein.

The present analysis suggests that the nonprocessive α-glycosyltransferases that were examined constitute a single protein family. These proteins have four conserved regions and a single domain, each presumably involved in the formation of α-glycosidic linkage between donor sugar and acceptor molecule. The lack of this conserved architecture in other α-glycosyltransferases indicates the presence of more than a single family in this class of enzymes, as previously described by Campbell et al. (3).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grant-in-aid 08457086 for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allaway D, Jeyaretnam B, Carlson R W, Poole P S. Genetic and chemical characterization of a mutant that disrupts synthesis of the lipopolysaccharide core tetrasaccharide in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6403–6406. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6403-6406.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brade L, Grimmecke H D, Holst O, Brabetz W, Zamojski A, Brade H. Specificity of monoclonal antibodies against Escherichia coli K-12 lipopolysaccharide. J Endotoxin Res. 1996;3:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell J A, Davies G J, Bulone V, Henrissat B. A classification of nucleotide-diphospho-sugar glycosyltransferases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1997;326:929–942. doi: 10.1042/bj3260929u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chappell T G, Hajibagheri M A, Ayscough K, Pierce M, Warren G. Localization of an alpha 1,2 galactosyltransferase activity to the Golgi apparatus of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:519–528. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.5.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, FitzHugh W, Fields C A, Gocayne J D, Scott J D, Shirley R, Liu L I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaboriaud C, Bissery V, Benchetrit T, Mornon J P. Hydrophobic cluster analysis: an efficient new way to compare and analyze amino acid sequences. FEBS Lett. 1987;224:149–155. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80439-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glaser P, Kunst F, Arnaud M, Coudart M P, Gonzales W, Hullo M F, Ionescu M, Lubochinsky B, Marcelino L, Moszer I, Presecan E, Santana M, Schneider E, Schweizer J, Vertes A, Rapoport G, Danchin A. Bacillus subtilis genome project: cloning and sequencing of the 97 kb region from 325 degrees to 333 degrees. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:371–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gotschlich E C. Genetic locus for the biosynthesis of the variable portion of Neisseria gonorrhoeae lipooligosaccharide. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2181–2190. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heinrichs D E, Monterio M A, Perry M B, Whitfield C. The assembly system for the lipopolysaccharide R2 core-type of Escherichia coli is a hybrid of those found in Escherichia coli K-12 and Salmonella enterica. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8849–8859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henrissat B. Weak sequence homologies among chitinases detected by clustering analysis. Protein Seq Data Anal. 1990;3:523–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henrissat B, Claeyssens M, Tomme P, Lemesle L, Mornon J P. Cellulase families revealed by hydrophobic cluster analysis. Gene. 1989;81:83–95. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hitchcock P J, Brown T M. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:269–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holst O, Zahringer U, Brade H, Zamojski A. Structural analysis of the heptose/hexose region of the lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli K-12 strain W3100. Carbohydr Res. 1991;215:323–335. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(91)84031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honda S, Takahashi M, Kakehi K, Ganno S. Rapid, automated analysis of monosaccharides by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography of borate complexes with fluorimetric detection using 2-cyanoacetamide. Anal Biochem. 1981;113:130–138. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honda S, Takahashi M, Nishimura Y, Kakehi K, Ganno S. Sensitive ultraviolet monitoring of aldoses in automated borate complex anion-exchange chromatography with 2-cyanoacetamide. Anal Biochem. 1981;118:162–167. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jansson P E, Lindberg A A, Lindberg B, Wollin R. Structural studies on the hexose region of the core in lipopolysaccharides from Enterobacteriaceae. Eur J Biochem. 1981;115:571–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb06241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadam S K, Rehemtulla A, Sanderson K E. Cloning of rfaG, B, I, and J genes for glycosyltransferase enzymes for synthesis of the lipopolysaccharide core of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:277–284. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.277-284.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keenleyside W J, Whitfield C. A novel pathway for O-polysaccharide biosynthesis in Salmonella enterica serovar Borreze. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28581–28592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohta M, Ina K, Kusuzaki K, Kido N, Arakawa Y, Kato N. Cloning and expression of the rfe-rff gene cluster of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1853–1862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker C G, Fessler L I, Nelson R E, Fessler J H. Drosophila UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase: sequence and characterization of an enzyme that distinguishes between denatured and native proteins. EMBO J. 1995;14:1294–1303. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pradel E, Parker C T, Schnaitman C A. Structures of the rfaB, rfaI, rfaJ, and rfaS genes of Escherichia coli K-12 and their roles in assembly of the lipopolysaccharide core. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4736–4745. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4736-4745.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeves R R, Hobbs M, Valvano M A, Skurnik M, Whitfield C, Coplin D, Kido N, Klena J, Maskell D, Raetz C R H, Rick P D. Bacterial polysaccharide synthesis and gene nomenclature. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:495–503. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(97)82912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roncero C, Casadaban M J. Genetic analysis of the genes involved in synthesis of the lipopolysaccharide core in Escherichia coli K-12: three operons in the rfa locus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3250–3260. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3250-3260.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothfield L, Romeo D. Role of lipids in the biosynthesis of the bacterial cell envelope. Bacteriol Rev. 1971;35:14–38. doi: 10.1128/br.35.1.14-38.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saxena I M, Brown R M, Jr, Fevre M, Geremia R A, Henrissat B. Multidomain architecture of β-glycosyl transferases: implications for mechanism of action. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1419–1424. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1419-1424.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shibayama K, Ohsuka S, Arakawa Y, Horii T, Ohta M. Abstracts of the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1997. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Site-directed mutagenesis analysis of glucosyltransferase II of E. coli K-12, abstr. H-12; p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinnott M L. Catalytic mechanisms of enzymic glycosyl transfer. Chem Rev. 1990;90:1171–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugiyama T, Kido N, Arakawa Y, Mori M, Naito S, Ohta M, Kato N. Rapid small-scale preparation method of cell surface polysaccharides. Microbiol Immunol. 1990;34:635–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1990.tb01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai C M, Frasch C E. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zvelebil M J J M, Sternberg M J E. Analysis and prediction of the location of catalytic residues in enzymes. Protein Eng. 1988;2:127–138. doi: 10.1093/protein/2.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]