Abstract

Objective.

To evaluate the relevance and clinical utility of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) surveys in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Methods.

Adults with SLE receiving routine outpatient care at a tertiary care academic medical center participated in a qualitative study. Patients completed PROMIS computerized adaptive tests (CATs) in 12 selected domains and rated the relevance of each domain to their experience with SLE. Focus groups and interviews were conducted to elucidate the relevance of the PROMIS surveys, identify additional domains of importance, and explore the utility of the surveys in clinical care. Focus group and interview transcripts were coded and a thematic analysis was performed using an iterative inductive process.

Results.

Twenty-eight women and four men participated in four focus groups and four interviews respectively. Participants endorsed the relevance and comprehensiveness of the selected PROMIS domains in capturing the impact of SLE on their lives. They ranked fatigue, pain interference, sleep disturbance, physical function and applied cognition-abilities as the most salient health-related quality of life (HRQOL) domains. They suggested that the disease agnostic PROMIS questions holistically captured their lived experience of SLE and its common comorbidities. Participants were enthusiastic about using PROMIS surveys in clinical care and described potential benefits in enabling disease monitoring and management, facilitating communication, and empowering patients.

Conclusion.

PROMIS includes the HRQOL domains of most importance to individuals with SLE. Patients suggest that these universal tools can holistically capture the impact of SLE and enhance routine clinical care.

Keywords: Patient-reported outcomes, systemic lupus erythematosus, health-related quality of life, qualitative research

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem, chronic autoimmune disease that can result in significant morbidity, including adverse health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Patients with SLE have significantly worse physical function, increased work impairment due to pain and fatigue, and poorer perceived mental health compared to those without SLE.1 In clinical encounters, individuals with SLE prioritize discussion of functional status and HRQOL, but physicians often focus on physical findings and laboratory results as more direct and easily measurable markers of disease.2, 3 Assessing patient-reported outcomes, including functional status and HRQOL, is essential to enabling the provision of comprehensive, patient-centered care.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) can facilitate the evaluation of HRQOL and other patient-reported outcomes through standardized surveys.4 PROMs include universal measures, which are designed for use across diseases, and disease-specific instruments, which measure domains relevant to specific conditions.5–7 Numerous universal and disease-specific PROMs are available to measure HRQOL in individuals with SLE, including the SF-36, LupusQOL and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®).5, 6 PROMIS was created by the National Institutes of Health as a universal metric designed to precisely measure physical, mental, and social health in clinically diverse populations across the lifespan.8–10 In contrast to older PROMs, PROMIS was developed using item response theory, enabling precise measurement of constructs on a continuum and allowing for the use of computerized adaptive testing (CAT), in which questions are dynamically administered based on preceding responses to reduce respondent burden and increase precision.8, 9, 11, 12 PROMIS surveys are scored with T-scores that are normalized to the United States general population, allowing ease of interpretation and comparison among distinct clinical populations.9

While PROMIS offers potential benefits in its precision, efficiency, and universality, the relevance of its generic domains in specific disease entities, including SLE, is not well established. PROMIS item banks were developed with the input of a representative sample of the US population, but patients with SLE were not explicitly included in this process.10, 13 Recent studies have investigated the psychometric validity of PROMIS instruments including short forms and CATs in individuals with SLE, demonstrating construct validity when compared to legacy instruments and strong test-retest reliability.14–18 However, the relevance of PROMIS item banks to individuals living with SLE in the US has not been directly evaluated. Given the growing use of PROMIS surveys in a variety of clinical and research settings,19–25 understanding whether these surveys measure constructs that are meaningful to patients with SLE is important. This qualitative study aimed to explore the relevance and potential clinical utility of PROMIS surveys in individuals with SLE.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We recruited patients previously enrolled in a longitudinal validation study of PROMIS surveys to participate in either focus groups or semi-structured interviews.14 Patients were English-speaking adults who met 1997 American College of Rheumatology SLE classification criteria and received care at an outpatient rheumatology clinic at a tertiary care academic medical center.26 Patients were purposively sampled based on demographic and disease variables to ensure a broad range of participants in focus groups and interviews. The study was reviewed and approved by the Hospital for Special Surgery Institutional Review Board (IRB# 14125).

Survey Measures

As part of the longitudinal study, patients completed PROMIS CATs, the SF-36, and the LupusQOL-US at two separate time points.14, 27, 28 After providing written informed consent to participate in this qualitative study, patients completed PROMIS CATs a third time one week prior to focus groups and interviews. PROMIS CATs were chosen in 12 domains based on prior studies exploring the HRQOL domains most salient to patients with SLE.29–31 Domains included: physical function (version 1.2), pain interference (v1.1), pain behavior (v1.0), fatigue (v1.0), social participation (v2.0), satisfaction with social roles (v2.0), applied cognition-abilities (v1.0), sleep-related impairment (v1.0), sleep disturbance (v1.0), anger (v1.1), anxiety (v1.0), and depression (v1.0).32 PROMIS CATs consist of multiple choice items querying symptoms in the seven preceding days, with the exception of the physical and social health domains which do not specify a recall time frame. Respondents completed PROMIS CATs and rated the relevance of each domain to their experience with SLE using a five-point Likert scale (“completely, mostly, moderately, a little, or not at all relevant”). They also reported whether their survey responses would have changed if questions had been specifically worded to reference their lupus. Participants were given a copy of their individual score reports and a brief explanation of score interpretation at the start of focus groups and interviews. All surveys, including PROMIS CATs, were administered using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).33

Focus Groups and Interviews

It was decided a priori to conduct single gender focus groups to encourage free discussion of ideas in areas which may be sensitive or gender specific. Women participated in 90-minute in-person focus groups. Due to small numbers and scheduling logistics, men participated in one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Interviews were conducted in person or by telephone and averaged 35 minutes in duration. Four investigators (AB, RH, JK, JR) with training in group facilitation and qualitative methods conducted the focus groups and interviews. Group sessions and interviews were guided by a written script which explored: 1) the relevance of PROMIS questionnaires to the experience of individuals with SLE; 2) HRQOL domains of importance to those with SLE, including those that were not included in the PROMIS surveys; and 3) the potential clinical utility of PROMIS surveys to patients. Following each focus group, moderators engaged in a debriefing session to identify emergent themes and consider modifications to the focus group guide prior to the next focus group. Focus groups and interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was achieved and were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, and deidentified for analysis.

Data Analysis

Two investigators (SK and EA) independently reviewed transcripts to develop the preliminary codebook. They then met to compare findings and develop a unified coding scheme that was applied to the transcripts. Themes and sub-themes were identified using an iterative inductive approach to evaluate the relevance of PROMIS surveys to patients’ experience of SLE and explore the possible utility of these surveys to patients.34 Code and themes were reviewed with a third investigator (AL) with expertise in qualitative analysis. Transcripts were uploaded into Dedoose™ cloud-based qualitative software for coding, comparison, and thematic analysis.

Results

Four focus groups with 28 female patients and one-on-one interviews with four male patients were conducted between January and March of 2017. Participants exhibited diverse characteristics in regard to race and ethnicity, insurance type, educational attainment, and disease duration (Table 1). Participants’ PROMIS CAT scores averaged a half standard deviation worse than the general population mean of 50 across domains (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants (n=32)

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, median (25th, 75th percentiles) years | 39 (33, 53.5) |

| Disease duration, median (25th, 75th percentiles) years | 11.6 (6.4, 24.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 28 (88) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 6 (21) |

| Black or African American | 14 (50) |

| Asian | 3 (11) |

| Other | 5 (18) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic, n (%) | 9 (28) |

| Insurance Type, n (%) | |

| Medicaid | 18 (56) |

| Medicare | 5 (16) |

| Third party/private | 9 (28) |

| Disability, by self-report, n (%) | |

| Yes | 18 (56) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Some high school or less | 1 (3) |

| High school graduate | 2 (6) |

| Some college | 12 (38) |

| College graduate | 10 (31) |

| Advanced degree | 7 (22) |

| PROMIS Computerized Adaptive Test (CAT) Scores* | |

| PROMIS CAT Domain | T-score mean (SD) |

|

| |

| Physical function | 43.3 (10.9) |

| Pain interference | 57.9 (10.2) |

| Pain behavior | 54.9 (10.5) |

| Fatigue | 56.4 (15.2) |

| Social participation | 45.7 (10.9) |

| Satisfaction with social roles | 44.3 (10.9) |

| Applied cognition-abilities | 46.2 (10.0) |

| Sleep-related impairment | 55.2 (11.8) |

| Sleep disturbance | 55.9 (14.0) |

| Anger | 47.8 (11.8) |

| Anxiety | 53.9 (10.3) |

| Depression | 52.5 (10.4) |

PROMIS CAT are scored by T-score from 0 to 100 (higher signifies more of the measured trait), with a score of 50 corresponding to the general population mean.

Relevance of PROMIS

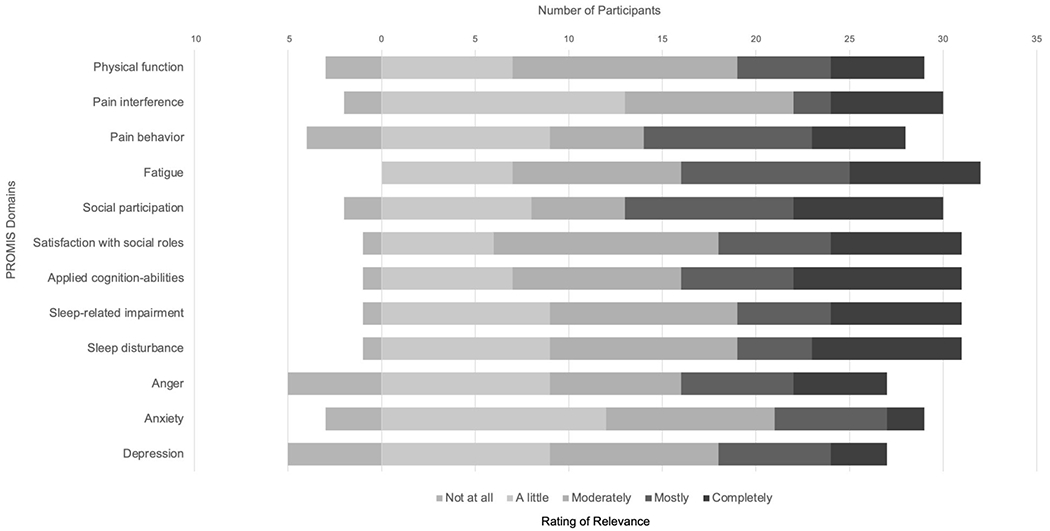

Participants rated the selected PROMIS domains as highly relevant to their experience of SLE in surveys prior to focus groups and interviews (Figure 1). During focus group discussions, several noted that the surveys were “comprehensive” and “covered everything.” One participant explained that the domains encapsulated a lot of what patients go through and “would help gauge what a person who’s dealing with lupus has to deal with.” Several participants commented on the relevance of the social and emotional domains in particular: “some of us live 100% normal lives with the pain—it’s that other stuff—the mental stuff that kind of makes it tough. So, I think it’s important to make sure questions address that.”

Figure 1.

SLE Patient Ratings of Relevance of PROMIS Domains (n=32)

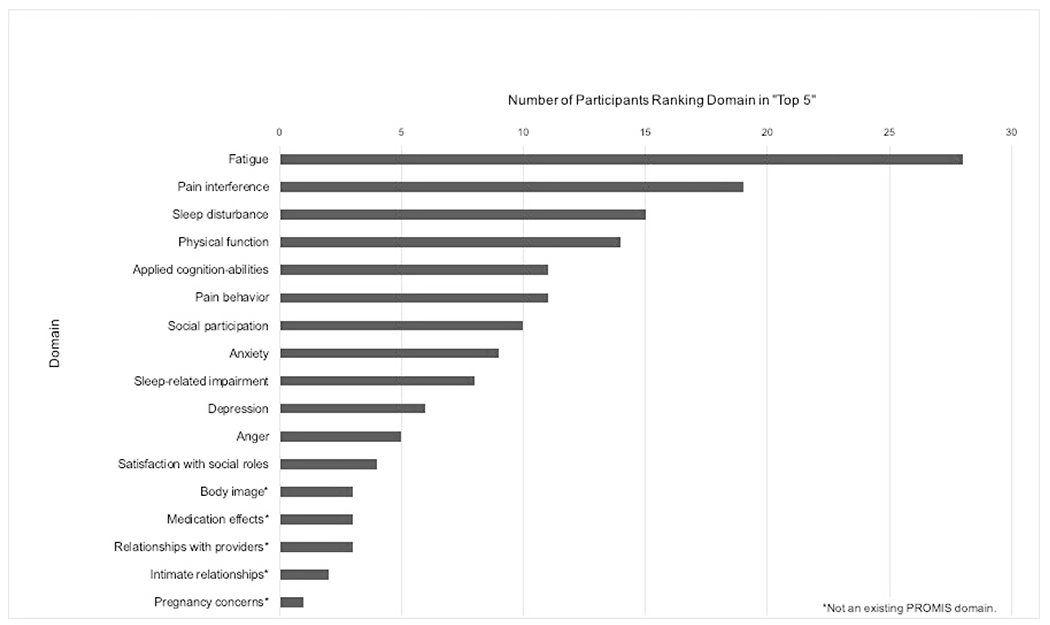

When asked to rate their top five HRQOL domains during focus groups and interviews, participants rated fatigue, pain interference, sleep disturbance, physical function and applied cognition-abilities as most important, with fatigue most frequently listed (Figure 2). Among the four male participants, three (75%) listed anxiety in their top five and commented on the importance of the surveys querying mental health: “lupus patients most normally see a rheumatologist and then various different specialties depending on their organ involvement, but sometimes things like anger, anxiety, and depression aren’t talked about as often or as deeply. I think the questionnaire having these specific categories can at least help bring to the doctor’s attention that a patient might be feeling depressed or is dealing with a lot of anxiety.”

Figure 2.

“Top 5” Health-Related Quality of Life Domains of Participants (n=32)

When queried, patients identified several significant areas of HRQOL that were not addressed by the selected PROMIS CATs. These included issues related to body image, medication side effects, intimate relationships, and pregnancy. These domains were listed in the top five most important areas of HRQOL by three participants (9%) or fewer (Figure 2).

While participants endorsed the overall relevance of PROMIS domains, many recommended an option to allow respondents to customize the surveys to include the domains of most importance. Some also suggested that the individual questions did not always capture the nuance and heterogeneity of the experience of patients with SLE. For example, many suggested that the pain domains, pain interference and pain behavior, would benefit from a ‘not applicable’ option and the inclusion of questions related to the fluctuation of symptoms with the weather and seasons. Some participants found the seven-day recall of PROMIS questions was not adequate to capture the breadth of symptoms experienced, particularly as it was too short a timeframe to accurately attribute symptoms to lupus or other factors. Several patients recommended the addition of a free text box to enable respondents to prioritize and contextualize their symptoms. They suggested that current treatment, flare status, comorbidities, and external stressors were important to comment on to explain their multiple-choice responses.

A recurring theme in the focus groups was the challenge patients faced in determining the etiology of their symptoms. They expressed difficulty attributing their symptoms to lupus or other factors, particularly with regard to pain, anxiety, and depression: “is it in the moment that you’re feeling that way? Or, is it the illness that [makes] you feel that way? Is it something that you upset about or you had—or something that happened during the day?” Participants suggested that personality, comorbid conditions including pregnancy, and external factors like stress, sleep, and care-taking responsibilities could cloud the picture: “It’s a symptom fog. What exactly am I going through? What’s wrong? Is it this? Is it that? Am I having my period? Am I going through menopause? Am I tired from my kids? Am I tired from work?” Considering the ambiguity in the origin of their symptoms, 18 participants (56%) reported that they answered the PROMIS surveys considering both lupus and their general health and 22 (69%) reported that their responses would not have changed if the survey had explicitly referenced their lupus.

Clinical Utility of PROMIS

Participants overall strongly endorsed using PROMIS surveys in their medical care, describing them as “straightforward,” “easy,” and “self-explanatory.” One patient with significant arthritis of the hands noted, “[PROMIS CATs] were easier than other surveys because we just had to press for our answers versus writing.” Twenty-two (69%) participants reported they wished to use PROMIS in their routine medical care when polled during focus groups and interviews. They cited several potential benefits of the surveys that centered on three major themes: disease monitoring and management, communication, and patient empowerment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical Utility of PROMIS Surveys

| Theme | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| 1. Disease Monitoring and Management | |

|

| |

| Enable tracking of symptoms and disease progression | “It’s a progress report in a sense. It’s to see how well you’re doing or how well you’re not doing, ways that you [and your doctor] can work on how to get you back to a good level.” “I think it’s a great way to check on a patient who has to deal with a chronic illness… I think it’ll help set benchmarks for the physician to compare their patient’s progress against.” “They can look back on previous years and see that maybe the used to put lots of pain or stuff like fatigue, severe, but then the can see a couple years later it’s more down to mild or not as often, or they’ve lowered the number they put for the pain. And think that… it helps them mentally by them being able to see, okay, I have made some progress.” “You saw the progression of the—from when I was diagnosed with it and now. What, twenty-four years ago? So that’s where it is. So I don’t mind continuing taking it, you can see how it progressed.” “…You can see [your progression] if you have the data to see it.” |

| Provide population norms | “I would think it would be beneficial to do these surveys if I could see not just my results, but the way the results were in relation to other patients with lupus.” “But I think I would be interested to see—instead of average for a mom, like zero to 100 years old, I would like to see an average of my age group.” “I think how you guys use [PROMIS scores] to tell us how we are doing could be how we are doing compared to normal people is really good.” |

| Inform clinical impression and management | “…I see it as the same way as when the doctor is going to see you, they look at their notes from the last visit. And so now they can correlate-- how was that physical exam? And how does it apply to whatever the patient is putting down here, make some type of connection and help them be more accurate way decide which way to go or not to go? It will help them in their modality and treatments.” “I think it’ll be great because she can read it, look at it, make a decision. Do I need to change prescription or what treatment can I do there?” “If they’re looking at the surveys and they’re comparing your scores and things like that, maybe going forward, if you’re continuously suffering from, let’s say it’s sleeplessness because of pain. Maybe the next step is to change the pain medication or get a different regimen…” “…If your doctor’s going in and looking at this survey, then they might see that this person needs help or needs a therapist. It might indicate something ‘cause having a support system is like integral.” “I think it’s useful as far as the [domains] that you know you can change because you’re aware of it… I’m aware of that, so I can be better.” |

|

| |

| 2. Communication | |

|

| |

| Aid self-expression | “You’ll come across something that you can’t express yourself and you see the question. And you can bring it out more.” “Sometimes you need that extra tool to help you out there to express what’s really going on with you. ‘Cause you may not be able to, one, verbalize it, or two, remember until afterwards.” |

| Reminder of symptoms | “It would help because there’s things you forget and the things you want to ask and you don’t for whatever reason, it doesn’t come up. And when you do remember it, it’s too late.” “‘Sometimes you go to the doctor, and the day you go, you are fine… So you can’t even tell where the pain was coming from. You don’t remember if it’s left or right. It just was a pain, and now it’s gone.” “I think it will help me bring up that stuff and not forget it so easily because it’s going to be there.” |

| Communicates patient’s perspective | “I think also it would help the doctor get a better understanding of you versus all patients. Because none of us are the same. We all different, deal with different situations.” “…It would have maybe a broader spectrum to understand your lupus, as it pertains to you, not an overall subject--as it pertains personally to my lupus experience.” |

| Prioritizes patient concerns, including emotional health | “[The survey] helps bring things to the surface. It helps you think about, okay, how would you rate your mental health?…We don’t think about mental health or how it’s affected by lupus.” “I think by [the surveys] having these specific categories can at least help maybe bring to the doctor’s attention that a patient might be feeling depressed or is dealing with a lot of anxiety, where maybe without the survey the patient may not mention it in a doctor’s appointment, and the doctor may not be aware of it.” |

| Guide conversation | “If [the doctor] sees something that maybe I marked differently from the last time, it’ll kind of give us a talking point, and we can talk about it, and then talk about courses of treatment from there. So usually we kind of have general conversations, but I think the survey can lead to maybe more specific conversations.” “I feel like by [PROMIS scores] being a benchmark with your doctor, it’s a good way for the doctor and the patient to have a good conversation about the course of the treatment.” |

| Enable asynchronous communication | “It might even be useful if like when you submit it in the portal, if your doctor gets a notification, for example…Maybe they could reach out like, I saw this aspect of your survey was really out of whack, or checking in.” “Maybe there’s some sort of concern, then you can give your doctor a call and say, hey, I’m noticing that there’s something going on here. Maybe you can give your doctor a call or something.” |

| Promote communication between providers and inform new providers | “The kidney doctor sees it, and the rheumatologist sees it. So now they may need to talk or they cross-referencing. It helps me ‘cause then I don’t have to explain it to five doctors. They can see it themselves what’s going on. So, I kind of like that as well.” “This will help you if you’re going to the emergency room, to the hospital, without your doctor being present. That’s really helpful. It would help to carry with you for the person that don’t know who you are.” |

| Communicate patient experience to friends and family | “You would be able to share this with your family. Because a lot of times, they don’t understand. And if you have -- black and white works. It just does. And if you’re just like, see, look, this is what I’m going through.” “The surveys like these might also be helpful for family and friends to also understand what you’re going through. Because again, they don’t go through it, so it’s hard for them to understand what you’re dealing with on a day-to-day basis.” |

|

| |

| 3. Patient Empowerment | |

|

| |

| Encourage self-reflection | “It made me think about, how am I really feeling? Are these the symptoms that I have, facing up to what I really have?” “It helps us reflect and really think about what is it that each one of us has.” |

| Promote self-awareness and provides validation | “…You kind of realize, you know what? I do have a problem with sleep. I do have a problem with this. Because sometimes you’re not even conscious of it. You’re just going on day to day.” “I think that like I probably experienced some form of denial… but it didn’t reflect me a lot until I saw the results. And I thought not only am I hiding it from other people, but you can hide it from myself.” “Doing these surveys fills that same role as like a release where I can say, ‘Man, this week I had a tough week’ and I can see where I’m relating to other people from a baseline-‘oh okay, so it’s kind of normal.’“ “It was a relief. It’s somebody sharing your pain… somebody thinking of you—that’s excellent.” |

Disease Monitoring and Management

Participants explained that they would like to use PROMIS scores to track their symptoms and monitor disease progression over the long term. They suggested that tracking symptoms would be beneficial for both patients and providers, so “that you both can work on how to get you back to a good level.” They also noted that normative results that compared their scores to others with SLE or the general population could be useful to contextualize their illness. Participants outlined how PROMIS scores could contribute to the physician’s clinical impression by incorporating the patient’s perspective and offering an objective metric to evaluate their illness in addition to the traditional physical exam and laboratory data. They suggested this data could help guide therapeutic decisions, including medication management and referrals. Additionally, some participants mentioned that PROMIS results could help them selfmonitor their symptoms and determine areas for improvement.

Communication

Patients suggested that PROMIS surveys could promote communication in multiple ways. Responding to PROMIS questions helped some participants convey aspects of their HRQOL that were difficult to articulate, and served as a reminder of symptoms they often forgot when they arrived at the doctor’s office. They noted that the surveys relayed each individual’s personal experience of lupus and that reviewing PROMIS results during visits could guide conversations towards patient concerns and priorities, including “non-physical things” such as emotional health. Some stated that they would like to complete surveys in between visits and be contacted if their results were of concern, suggesting that the surveys could serve as tools for asynchronous communication with their providers and promote continuity of care. Participants also felt that PROMIS results, if accessible to specialists across a health system, could help streamline multi-disciplinary care and reduce redundancy. Lastly, some proposed that PROMIS results could be used to educate family members and friends about their disease. Citing the concrete nature of the numeric scores, patients felt the surveys could legitimize their symptoms to those unfamiliar with SLE.

Patient Empowerment

Patients suggested PROMIS surveys could be empowering because they encouraged self-reflection and promoted self-awareness and validation of illness. The questions prompted participants to sincerely reflect on their health, and at times compelled them to confront denial about their symptoms. For many participants, the surveys brought clarity by naming symptoms “put to the back of the mind” and validation through the realization that they were not alone in their experience.

While many participants found inherent value in completing the surveys, several emphasized the necessity of physicians reviewing results. One woman observed, “if they’re not going to dig in my lifestyle and how I deal with my lupus, then why bother?” while another noted, “if the doctor is actually going to take the time to actually look at what you filled out, then yeah… [if] you’re not even paying attention to the survey, then what was my point of filling it out?” A few patients did not feel the surveys would be of added value even if reviewed by their doctors. As one participant stated, “I have a very good relationship with my doctor. So, I don’t need the survey.” Another elaborated, “I guess it depends on what kind of relationship you have with the doctor … mine’s goes out of his way. He’ll call me. He’ll ask me those questions.”

Discussion

In this study, we found that core PROMIS domains were relevant to diverse individuals with SLE. Patients reported that the selected PROMIS surveys reflected their lived experience with SLE and queried their most important HRQOL concerns. Our findings provide evidence of the pertinence of PROMIS domains in SLE and complement the growing psychometric data supporting the use of these instruments in individuals with SLE.

Our data suggest that although PROMIS was developed without the explicit input of individuals with SLE, the surveys strongly resonate with this population and capture the essential physical, social, and emotional aspects of their condition. The HRQOL domains prioritized by patients in our study-- fatigue, pain, sleep, physical function, cognitive abilities, social participation, mood (anxiety/depression)– are directly addressed by the core PROMIS surveys selected for this study. Participants noted additional areas of importance, including body image, intimate relationships, and family planning/pregnancy concerns, that are not addressed by existing PROMIS item banks. These findings are consistent with prior studies which have identified these concepts as relevant and prompted the creation of corresponding domains in lupus-specific instruments.29–31, 35 Although patients in our study did not consistently rank these additional domains as “most important,” development of dedicated PROMIS item banks exploring these areas may be warranted to comprehensively assess the patient experience of SLE.31 In the interim, the use of relevant domains from lupus-specific instruments in conjunction with PROMIS item banks may enable the capture of these important constructs in research and clinical settings.

In addition to confirming the relevance of specific HRQOL domains in patients with SLE, our study offers several insights on how PROMIS surveys can be optimized for use in this population. Patients highlighted the heterogeneity of SLE symptoms between individuals and within a single individual over time, noting that some people have lupus limited to a single organ system such as the kidneys while others have more varied cutaneous and musculoskeletal manifestations. Suggestions to enable individual selection of domains and inclusion of free text boxes may allow patients to customize surveys to reflect their experience. Patient recommendations to include a “not applicable” answer choice for pain domains and to add questions related to the seasonality of symptoms may also better accommodate the diverse and variable manifestations of SLE. The seven-day recall timeframe of PROMIS surveys, which several participants felt was too brief to accurately assess and attribute SLE-related symptoms, may require adjustment to account for the often insidious onset of SLE symptoms. The interval between clinical visits and the frequency of survey completion are other factors to consider in determining the ideal item recall timeframe.36

While there have been concerns about how well universal measures like PROMIS can capture disease-specific issues,5, 6 patients in our study suggested that PROMIS may offer unique benefits as a disease agnostic tool. They emphasized uncertainty in attributing symptoms to a particular cause due to the waxing and waning nature of SLE and numerous associated comorbidities. A majority reported that they answered survey questions considering both lupus and their general health and noted that PROMIS, as a universal instrument, could accommodate this lack of clarity by holistically assessing their condition. They also posited that the generic surveys could facilitate communication across clinical contexts and specialties and reduce redundancy in health care visits by relaying their experience using a common language and normalized scoring metric. PROMIS metrics, which are increasingly being utilized by health systems for a variety of purposes,19–25 may thus be well suited for use in diverse clinical settings, while disease-specific measures may be particularly valuable in SLE clinical trials.

We found that a majority of SLE patients welcomed PROMIS surveys as tools to facilitate their clinical care and emphasized the importance of physicians reviewing their results. This finding is noteworthy in the context of a recent study which demonstrated that over 50% of treating physicians do not systematically evaluate the HRQOL of SLE patients in routine clinical care.37 Nearly 70% of participants wished to complete the surveys routinely, citing potential utility in promoting disease monitoring and management, communication, and patient empowerment through self-reflection and validation of experience. These benefits have been demonstrated in prospective studies of the clinical implementation of PROMs in SLE and other patient populations.38–41 Participants who preferred not to use the questionnaires cited time constraints and the diminishing value of the surveys in the setting of strong provider relationships, suggesting that there may be particular contexts or populations in which these tools are most valuable. Notably, all four male participants wished to use the surveys and specifically highlighted their value in querying social and emotional health. They independently observed that emotional health is often not prioritized in medical visits, suggesting an unmet need in men with SLE that may warrant further characterization in larger studies.

Our study has multiple strengths, including the racially and socio-economically diverse patient population and the rigorous qualitative methods employed. The generalizability of our findings may be limited, however, as our population was restricted to English-speaking patients from a single academic medical center in the United States. Further studies are needed to evaluate the relevance of PROMIS surveys, which are available in multiple languages,42 in non-English-speaking populations with SLE. In addition, our study reports the perspectives of research participants, a group that may differ from non-participants and the broader population of individuals with SLE. The use of different procedures for discussion and data gathering for women and men (focus groups and interviews respectively) may have also affected the themes generated. Finally, although we examined numerous PROMIS domains, we did not evaluate individual survey questions, as participants completed CATs which deliver variable items based on the computerized adaptive design. Review of individual questions and answer choices and their relevance to constructs of interest is an important next step in evaluating PROMIS instruments in individuals with SLE.

In conclusion, this study provides qualitative evidence that PROMIS domains capture central aspects of HRQOL in individuals with SLE and appeal to patients as tools to enhance their health and health care. Our findings offer insight on the optimization of these instruments to better meet the needs of SLE patients and suggest that the holistic evaluation of quality of life through PROMIS surveys is patient-centered in its embrace of the uncertainty that characterizes this complex chronic illness.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study and Madeline J. Epsten for assistance with data collection.

Funding Sources:

This work was funded in part by the Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development Award, the Hospital for Special Surgery Lupus and APS Center of Excellence Research Award, the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant K23AR078177, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002384. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Shanthini Kasturi, Division of Rheumatology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA.

Emily L. Ahearn, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA.

Adena Batterman, Department of Social Work, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY.

Roberta Horton, Department of Social Work, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY.

Juliette Kleinman, Department of Social Work, Montefiore Health System, Bronx, NY.

Jillian Rose-Smith, Department of Social Work, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY.

Amy M. LeClair, Department of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA.

Lisa A. Mandl, Division of Rheumatology, Hospital for Special Surgery and Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY.

References

- 1.Grabich S, Farrelly E, Ortmann R, Pollack M, Wu SS. Real-world burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in the USA: a comparative cohort study from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) 2016-2018. Lupus Sci Med. May 2022;9(1)doi: 10.1136/lupus-2021-000640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yen JC, Abrahamowicz M, Dobkin PL, Clarke AE, Battista RN, Fortin PR. Determinants of discordance between patients and physicians in their assessment of lupus disease activity. J Rheumatol. Sep 2003;30(9):1967–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alarcon GS, McGwin G Jr., Brooks K, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XI. Sources of discrepancy in perception of disease activity: a comparison of physician and patient visual analog scale scores. Arthritis Rheum. Aug 2002;47(4):408–13. doi: 10.1002/art.10512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research USDoHaHSFCfBEaR. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. Oct 11 2006;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen MH, Huang FF, O’Neill SG. Patient-Reported Outcomes for Quality of Life in SLE: Essential in Clinical Trials and Ready for Routine Care. J Clin Med. Aug 23 2021; 10(16)doi: 10.3390/jcm10163754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahieu M, Yount S, Ramsey-Goldman R. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. May 2016;42(2):253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Churruca K, Pomare C, Ellis LA, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): A review of generic and condition-specific measures and a discussion of trends and issues. Health Expect. Aug 2021;24(4):1015–1024. doi: 10.1111/hex.13254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Updated January 29, 2019. 2022. https://commonfund.nih.gov/promis/index [Google Scholar]

- 9.Intro to PROMIS®. Northwestern University. 2022. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. Nov 2010;63(11):1179–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fries JF, Bruce B, Cella D. The promise of PROMIS: using item response theory to improve assessment of patient-reported outcomes. Clin Exp Rheumatol. Sep-Oct 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S53–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witter JP. The Promise of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Turning Theory into Reality: A Uniform Approach to Patient-Reported Outcomes Across Rheumatic Diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. May 2016;42(2):377–94. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA, Group PC. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. May 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S12–21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasturi S, Szymonifka J, Burket JC, et al. Validity and Reliability of Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Computerized Adaptive Tests in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Rheumatol. Jul 2017;44(7):1024–1031. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.161202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moazzami M, Katz P, Bonilla D, et al. Validity and reliability of patient reported outcomes measurement information system computerized adaptive tests in systemic lupus erythematous. Lupus. Nov 2021;30(13):2102–2113. doi: 10.1177/09612033211051275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz P, Yazdany J, Trupin L, et al. Psychometric Evaluation of the National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System in a Multiracial, Multiethnic Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). Dec 2019;71(12):1630–1639. doi: 10.1002/acr.23797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasturi S, Szymonifka J, Burket JC, et al. Feasibility, Validity, and Reliability of the 10-item Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global Health Short Form in Outpatients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Rheumatol. Mar 2018;45(3):397–404. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai JS, Beaumont JL, Jensen SE, et al. An evaluation of health-related quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus using PROMIS and Neuro-QoL. Clin Rheumatol. Mar 2017;36(3):555–562. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3476-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papuga MO, Dasilva C, McIntyre A, Mitten D, Kates S, Baumhauer JF. Large-scale clinical implementation of PROMIS computer adaptive testing with direct incorporation into the electronic medical record. Health Syst (Basingstoke). 2018;7(1):1–12. doi: 10.1057/s41306-016-0016-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerhardt WE, Mara CA, Kudel I, et al. Systemwide Implementation of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Routine Clinical Care at a Children’s Hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. Aug 2018;44(8):441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans JP, Smith A, Gibbons C, Alonso J, Valderas JM. The National Institutes of Health Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): a view from the UK. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2018;9:345–352. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S141378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin E, LeRouge C, Hartzler AL, Segal C, Lavallee DC. Capturing the patient voice: implementing patient-reported outcomes across the health system. Qual Life Res. Feb 2020;29(2):347–355. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02320-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biber J, Ose D, Reese J, et al. Patient reported outcomes - experiences with implementation in a University Health Care setting. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;2:34. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0059-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumenthal KJ, Chang Y, Ferris TG, et al. Using a Self-Reported Global Health Measure to Identify Patients at High Risk for Future Healthcare Utilization. J Gen Intern Med. Aug 2017;32(8):877–882. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4041-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapin B, Katzan IL. PROMIS global health: potential utility as a screener to trigger construct-specific patient-reported outcome measures in clinical care. Qual Life Res. Aug 10 2022;doi: 10.1007/s11136-022-03206-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. Sep 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware JE Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. Jun 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jolly M, Pickard AS, Wilke C, et al. Lupus-specific health outcome measure for US patients: the LupusQoL-US version. Ann Rheum Dis. Jan 2010;69(1):29–33. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McElhone K, Abbott J, Gray J, Williams A, Teh LS. Patient perspective of systemic lupus erythematosus in relation to health-related quality of life concepts: a qualitative study. Lupus. Dec 2010;19(14):1640–7. doi: 10.1177/0961203310378668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jolly M, Pickard AS, Block JA, et al. Disease-specific patient reported outcome tools for systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. Aug 2012;42(1):56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ow YL, Thumboo J, Cella D, Cheung YB, Yong Fong K, Wee HL. Domains of health-related quality of life important and relevant to multiethnic English-speaking Asian systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a focus group study. Arthritis Care Res. Jun 2011;63(6):899–908. doi: 10.1002/acr.20462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.List of Adult Measures. 2022. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis/list-of-adult-measures

- 33.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. Apr 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. Aug 2007;42(4):1758–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McElhone K, Abbott J, Shelmerdine J, et al. Development and validation of a disease-specific health-related quality of life measure, the LupusQol, for adults with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. Aug 15 2007;57(6):972–9. doi: 10.1002/art.22881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stull DE, Leidy NK, Parasuraman B, Chassany O. Optimal recall periods for patient-reported outcomes: challenges and potential solutions. Curr Med Res Opin. Apr 2009;25(4):929–42. doi: 10.1185/03007990902774765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golder V, Ooi JJY, Antony AS, et al. Discordance of patient and physician health status concerns in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. Mar 2018;27(3):501–506. doi: 10.1177/0961203317722412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasturi S, Price LL, LeClair A, et al. Clinical integration of patient-reported outcome measures to enhance the care of patients with SLE: a multi-center prospective cohort study. Rheumatology. Mar 31 2022;doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keac200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartlett SJ, De Leon E, Orbai AM, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in RA care improve patient communication, decision-making, satisfaction and confidence: qualitative results. Rheumatology. Jul 1 2020;59(7):1662–1670. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carfora L, Foley CM, Hagi-Diakou P, et al. Patients’ experiences and perspectives of patient-reported outcome measures in clinical care: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0267030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basch E, Stover AM, Schrag D, et al. Clinical Utility and User Perceptions of a Digital System for Electronic Patient-Reported Symptom Monitoring During Routine Cancer Care: Findings From the PRO-TECT Trial. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. Oct 2020;4:947–957. doi: 10.1200/CCI.20.00081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Intro to PROMIS®: Available Translations. Northwestern University. Updated August 22, 2022. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis/intro-to-promis/available-translations [Google Scholar]