Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

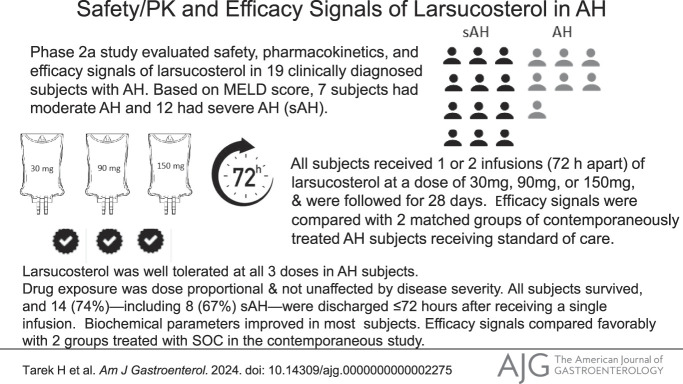

This study is to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics (PK) of larsucosterol (DUR-928 or 25HC3S) in subjects with alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH), a devastating acute illness without US Food and Drug Administration–approved therapies.

METHODS:

This phase 2a, multicenter, open-label, dose escalation study evaluated the safety, PK, and efficacy signals of larsucosterol in 19 clinically diagnosed subjects with AH. Based on the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, 7 subjects were considered to have moderate AH and 12 to have severe AH. All subjects received 1 or 2 intravenous infusions (72 hours apart) of larsucosterol at a dose of 30, 90, or 150 mg and were followed up for 28 days. Efficacy signals from a subgroup of subjects with severe AH were compared with those from 2 matched arms of those with severe AH treated with standard of care (SOC), including corticosteroids, from a contemporaneous study.

RESULTS:

All 19 larsucosterol-treated subjects survived the 28-day study. Fourteen (74%) of all subjects including 8 (67%) of the subjects with severe AH were discharged ≤72 hours after receiving a single infusion. There were no drug-related serious adverse events nor early terminations due to the treatment. PK profiles were not affected by disease severity. Biochemical parameters improved in most subjects. Serum bilirubin levels declined notably from baseline to day 7 and day 28, and MELD scores were reduced at day 28. The efficacy signals compared favorably with those from 2 matched groups treated with SOC. Lille scores at day 7 were <0.45 in 16 of the 18 (89%) subjects with day 7 samples. Lille scores from 8 subjects with severe AH who received 30 or 90 mg larsucosterol (doses used in phase 2b trial) were statistically significantly lower (P < 0.01) than those from subjects with severe AH treated with SOC from the contemporaneous study.

DISCUSSION:

Larsucosterol was well tolerated at all 3 doses in subjects with AH without safety concerns. Data from this pilot study showed promising efficacy signals in subjects with AH. Larsucosterol is being evaluated in a phase 2b multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled (AHFIRM) trial.

KEYWORDS: alcohol-associated hepatitis, larsucosterol, efficacy signals, safety, pharmacokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH), an acute form of alcohol-associated liver disease, results from long-term heavy intake of alcohol, frequently on a background of cirrhosis and usually after a recent period of increased alcohol consumption (1). AH is typically characterized by a recent onset of jaundice, progressive cholestasis, and hepatocellular dysfunction. Patients may be febrile and have leukocytosis in the absence of infection. In a retrospective analysis of 77 studies between 1971 and 2016 including >8,000 patients, an average mortality from AH was 26% at 28 days and 29% at 90 days (2). Consistently, a recent prospective study that enrolled >2,500 hospitalized patients with AH (median model for end-stage liver disease [MELD] score 23.5) by 85 hospitals in 11 countries across 3 continents showed that mortality at 28 days and 90 days was 20% and 30.9%, respectively (3). According to the most recent data provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US Department of Health and Human Services), 136,620 patients with AH were hospitalized in 2019 with an average hospital charge estimated at >$50,000 (4).

There is no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved treatment for severe AH. The current standard of care (SOC) as delineated in multiple treatment guidelines for subjects with severe AH consists of supportive care and the use of corticosteroids (CS) if there are no contraindications (1). However, the large placebo-controlled Steroids or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH) trial failed to show a 90-day survival benefit of CS (5). Other efforts have focused on inflammation, cell death, or tissue regeneration aspects of AH pathogenesis (6,7).

A recent study using liver samples from patients with AH and other liver diseases proposed epigenetic dysregulation as the mechanism of hepatocellular dysfunction and subsequent liver failure in AH (8). The observed epigenetic dysregulation in the liver included an increased expression of DNA methyltransferases (DNMT), aberrant DNA methylation, and transcriptomic reprogramming, suggesting that DNMT inhibition could be a novel therapeutic approach for severe AH.

Larsucosterol is an endogenous cholesterol derivative, 25-hydroxycholesterol 3-sulfate (25HC3S), which was discovered in the cell nucleus after an overexpression of a mitochondrial cholesterol transporter protein, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STARD1) (9). Functional studies (10) demonstrated that 25HC3S reduces intracellular lipid accumulation by inhibiting lipid biosynthesis, dampens inflammation by decreasing inflammatory mediators, and improves cell survival by suppressing apoptosis. Mechanistic studies (11) showed that 25HC3S inhibited DNMT1, 3a and 3b, and reduced DNA hypermethylation.

Endogenous 25HC3S was present in all 7 species studied to date, including humans. It has been evaluated in vitro in cell lines or primary cells, in vivo in animal disease models, in toxicology studies, and in human subjects (both healthy volunteers and patients) for its pharmacology, toxicology, safety, pharmacokinetics (PK), and efficacy signals. More than 350 human subjects, who were enrolled in more than 10 phase 1 and 2 clinical trials sponsored by DURECT in the United States or overseas, have received larsucosterol, the results of which have demonstrated excellent safety profiles and promising efficacy signals. In this phase 2a, multicenter, open-label, dose escalation study, we investigated the safety, PK, and efficacy signals of larsucosterol in subjects with a clinical diagnosis of AH.

METHODS

The study was conducted in 5 centers in the United States (Southern California Research Center, Piedmont Hospital Transplant Services, Northwestern University Health System, University of Miami, and University of Louisville School of Medicine) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03432260. The protocol was approved by a central Institutional Review Board (IRB) (WCG IRB No. 20180736) and each local IRB. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject or the subject's legal guardian before any undertaking any study-related activity. The trial was conducted and reported in accordance with US FDA guidance, the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice, and the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

In a contemporaneous study, subjects with severe AH were recruited from 4 US clinical centers (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Cleveland Clinic, and University of Louisville School of Medicine). This study was part of a large national multisite clinical trial indexed at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01809132. The study was approved by all local IRBs. All subjects provided informed consent to participate in this trial.

The primary objectives of the study were the safety, PK, and efficacy signals of larsucosterol in subjects with AH. The primary efficacy signal was Lille score at day 7. Other efficacy signals included serum total bilirubin change from baseline, the MELD score change from baseline, liver biomarkers (such as aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], and albumin), length of hospital stay, and mortality during the 28-day study period.

Study agent

Larsucosterol is the sodium salt of 25HC3S. Its injection, 30 mg/mL larsucosterol sodium, is a sterile solution containing 240 mg/mL of hydroxypropyl betadex. Before use, 1, 3, or 5 mL of this solution, corresponding to 30, 90, or 150 mg of larsucosterol sodium, respectively, was diluted in 100 mL of sterile saline or 5% dextrose and administered by intravenous (IV) infusion over 2 hours.

Subjects

A total of 19 subjects with AH received larsucosterol in this trial. Among them, 18 (95%) returned for the day 7 and 16 (84%) returned for the day 28 visit, although all 19 were confirmed alive at the end of the 28-day study period.

All subjects were hospitalized during enrollment with a clinical diagnosis of AH according to the guideline consensus publication (1) and were 21 years or older with 20 kg/m2≤ body mass index ≤ 40 kg/m2. All 19 enrolled subjects met inclusion criteria of the clinical trial protocol for the study, including alcohol consumption >40 g/d in female individuals or >60 g/d in male individuals for a minimum period of 6 months; an increased consumption of alcohol within 12 weeks of entry into the study; serum bilirubin >3 mg/dL; AST >ALT but <300 U/L; an MELD score between 11 and 30; and no evidence of active infection as determined by the principal investigator (PI). However, none of the patients had histopathological confirmation of the diagnosis by liver biopsy during screening or enrollment, which is not recommended according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidance (1). Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, lactation, mental handicap, inability to provide consent, and/or signs of systemic infection and/or other chronic diseases that would be a contraindication to planned therapy.

In the contemporaneous study, eligible subjects were enrolled by their liver disease severity as determined by the MELD score and Maddrey Discriminant Function. Subjects with severe AH were matched by the MELD score to the 8 patients with severe AH who received 30 or 90 mg of larsucosterol. Two study arms were used; one from an observational arm (n = 8), who had 7-day follow-up tests to assess Lille score, and the other from a larger parallel comparison arm (n = 16). Subjects from both arms were diagnosed of AH based on the guideline (1), screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria that were similar to the larsucosterol trial and as published by the Defeat Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (DASH) consortium (12,13), and treated with SOC, including CS.

Treatment

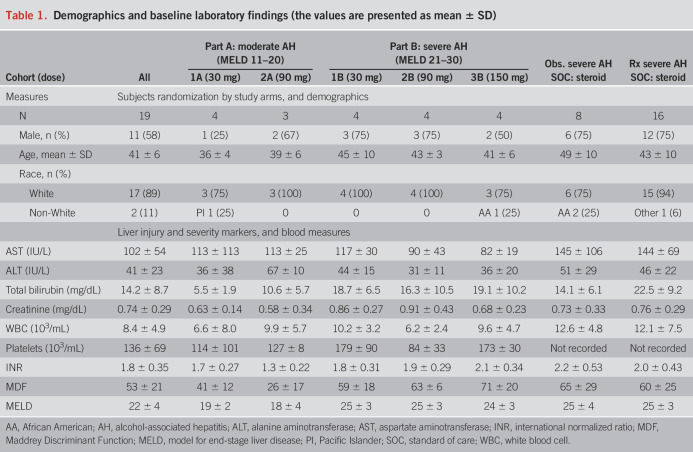

The study was unblinded, dose escalating, and conducted in 2 parts using a staggered parallel design (Figure 1). Part A included hospitalized subjects with MELD scores of 11–20 (moderate AH), while part B included hospitalized subjects with MELD scores of 21–30 (severe AH). The selected MELD score cutoffs were mainly based on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidance (1), the results of the STOPAH trial (5) regarding the efficacy of CS for severe AH, a consensus panel on AH diagnosis (14), and a design that was accepted by the US FDA (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02655510). The study was initiated with 4 subjects with moderate AH receiving 30 mg of larsucosterol. Dose escalation to 90 mg of larsucosterol within part A was permitted after a review of safety and PK data by the Dose Escalation Committee, which included the study PI, the Medical Monitor, and the Sponsor. If no suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction was observed and PK results were satisfactory, dose escalation to the next higher dose would proceed. In parallel, enrollment of 4 subjects with severe AH (part B) at the low dose (30 mg) was initiated only after safety and PK results review of the 30 mg larsucosterol in subjects with moderate AH (part A) had been completed. There were only 3 subjects with moderate AH enrolled in the 90 mg group when all 12 subjects with severe AH (part B) enrolled and completed dose escalation in the groups of 30, 90, and 150 mg (4 subjects/group). All subjects were followed up for 28 days and were assessed for safety, PK, and efficacy signals.

Figure 1.

The study schema. The study was conducted in 2 parts using a staggered parallel design. Part A included subjects with MELD scores of 11–20 (moderate AH), while part B included subjects with MELD scores of 21–30 (severe AH). The study was initiated with 4 subjects with moderate AH receiving 30 mg of larsucosterol by infusion. Dose escalation to 90 mg within part A was permitted after a review of safety and PK data by the DEC, including the study PI, the Medical Monitor, and the Sponsor. In parallel, enrollment of 4 subjects with severe AH (part B) for the low-dose (30 mg) group was only initiated once safety and PK results review of the 30 mg in subjects with moderate AH (part A) had been completed. Part A was terminated when part B enrollment met the prespecified enrollment goal. Subjects were followed up for 28 days and were assessed for safety, PK, and efficacy signals. AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis; DEC, Dose Escalation Committee; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PI, principal investigator; PK, pharmacokinetics.

Larsucosterol at a dose of 30, 90, or 150 mg was administered by IV infusion over approximately 2 hours for 1 or 2 infusions. After the first infusion on day 1, the second infusion would be given on day 4 (72 hours apart) if the subject remained to be hospitalized. If subjects were qualified to be discharged in the opinion of their PI, they would receive only 1 infusion.

Sample analysis

Plasma samples were collected at designated time points after the first infusion. Larsucosterol concentrations were measured using solid phase extraction, and a sensitive high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry method was developed and validated. The calibration range of the method was 2–500 ng/mL.

Subgroup analyses of data from subjects with severe AH was defined by an MELD score of 21–30. All subgroups were compared for the change from baseline at day 7 and/or day 28. The contemporaneous control arms were used to compare the Lille scores at day 7 with the results from this study. Baseline value was defined as the last nonmissing value before study drug administration, either at screening or day 1 predose.

Statistical methods

The number of subjects enrolled and who received at least 1 dose of larsucosterol were defined as both the intention to treat (ITT) and safety sets. This was clarified in the terminology used to describe the analyses in this study. The PK analysis set was defined as those subjects in the ITT analysis set who had evaluable PK data. All other analyses were conducted using the ITT Set. No formal sample size estimates were performed. The number of subjects was consistent with trials of this design and objectives. Planned statistical analyses were primarily descriptive in nature. Continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were summarized by presenting the number and percentage of subjects within each category. All tabulations were based on pooled data across centers. Analyses of PK data were performed using WinNonlin software, version 6.4 (Certara USA, Princeton, NJ). All other analyses were performed using SAS for Windows statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC). The analyses of the change in total bilirubin, the MELD score, and the Lille score and of biomarkers were described as efficacy signal analyses.

RESULTS

Safety

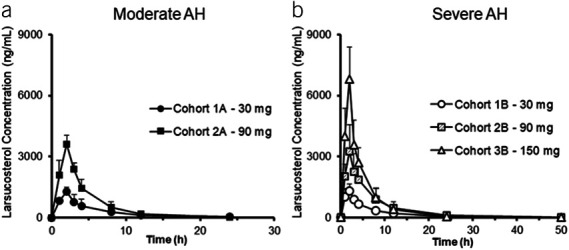

A total of 19 subjects with AH were enrolled, 7 in part A (moderate AH) and 12 in part B (severe AH). The median age was 41 year old, 58% were male, and 90% were White. The subject population in this pilot study was limited in diversity primarily because of the sample size of the study and small number of clinical sites involved. All subjects survived the 28-day study period. Demographics and baseline laboratory values (median) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline laboratory findings (the values are presented as mean ± SD)

Larsucosterol was well tolerated and safe at the 3 doses studied (30, 90, and 150 mg) when administered as 1 or 2 IV infusions in subjects with moderate or severe AH. Results from vital signs, physical examinations, and electrocardiograms supported the overall assessment that larsucosterol was safe in this group of subjects. Throughout the study, no suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions, defined as the primary safety end point, or deaths were reported. No treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE) led to discontinuation of study participation or modification of larsucosterol dosing. Three subjects experienced TEAE that were considered possibly or probably related to the study drug observed, including 1 instance each of grade 2 generalized pruritus, grade 1 rash, and grade 2 increase in ALP. All events resolved spontaneously.

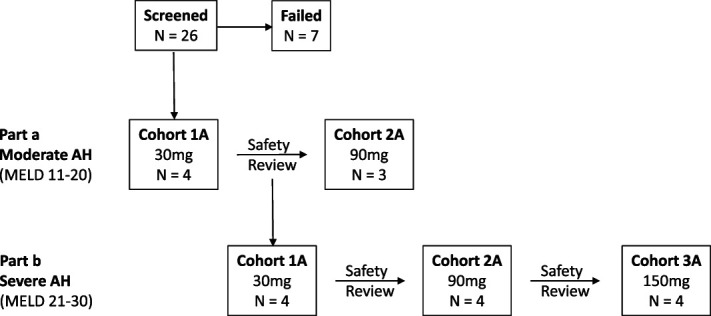

Pharmacokinetics

PK profiles were comparable between subjects with moderate or severe AH and, therefore, were not affected by disease severity. As shown in Figure 2, Tmax was at the end of the 2-hour infusion for all doses. AUC(0-last), AUC(0-inf), Cmax, and Clast of larsucosterol increased proportionally with increased dose (see Supplementary Figure S1, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/C933). The t½ of larsucosterol was approximately 4 hours, and the time for the last quantifiable concentration was similar for all doses. The residual area was less than 5% in all 3 dose groups, indicating that sampling times were adequate. PK parameters of larsucosterol, including clearance and volume of distribution, were shown in Supplementary Table S1 (see Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/C933). Compared with PK data in healthy volunteers from an earlier phase 1 study, the Cmax and AUC of larsucosterol in subjects with AH were increased by 2-fold and 6-fold, respectively, while the clearance was decreased by approximately 75%.

Figure 2.

Plasma concentrations of larsucosterol over time in subjects with AH. Plasma samples were taken before, during, and after a 2-hour infusion of larsucosterol in subjects with moderate and severe AH. (a, left) Plasma concentrations of larsucosterol over time in subjects with moderate AH (mean ± SD). Four subjects received 30 mg of larsucosterol (solid round) and 3 received 90 mg of larsucosterol (solid square). (b, right) Plasma concentrations of larsucosterol over time in subjects with severe AH (mean ± SD). Four subjects each received 30 mg (empty round), 90 mg (shaded square), or 150 mg of larsucosterol (empty triangle). AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis.

Hospital discharge and survival

Of all 19 subjects enrolled, 14 (74%) received only 1 infusion and were discharged from hospitals in ≤72 hours after dosing. Among subjects with severe AH, 8 of 12 (67%) did not receive the second infusion and were discharged from hospitals in ≤72 hours. Although 1 subject did not complete the day 7 and day 28 visits and 2 subjects did not complete the day 28 visit, all 19 subjects, 100%, survived the 28-day study period.

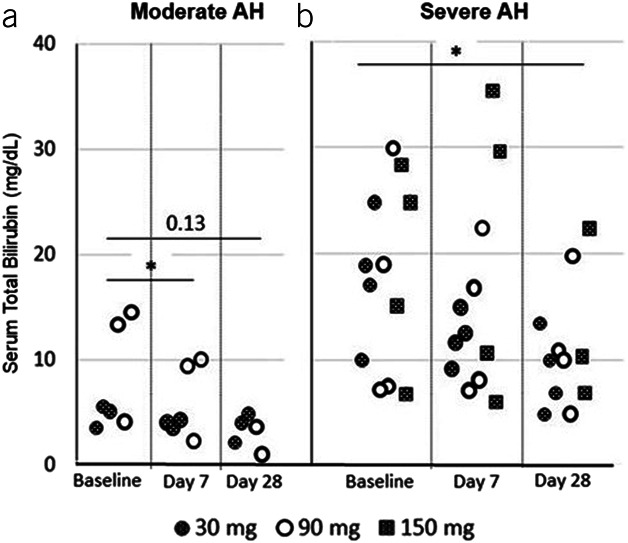

Serum bilirubin

After larsucosterol dosing, rapid and significant reductions of serum total bilirubin levels from baseline were observed at both day 7 and day 28 (Figure 3). Statistically significant reductions from baseline were observed at day 7 in subjects with moderate AH (P < 0.05) and at day 28 in subjects with severe AH (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Serum total bilirubin levels over time in subjects with AH. Serum total bilirubin levels (mg/dL) from individual subjects (who returned for sample collection) were determined at baseline, day 7, and day 28 (end of the study) after the first infusion. Shaded circles represent subjects who received 30 mg of larsucosterol, empty circles are those who received 90 mg of larsucosterol, and shaded squares show those who received 150 mg of larsucosterol. (a, left) Subjects with moderate AH, and (b, right) Subjects with severe AH. *Represents P < 0.05 by t test. AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis.

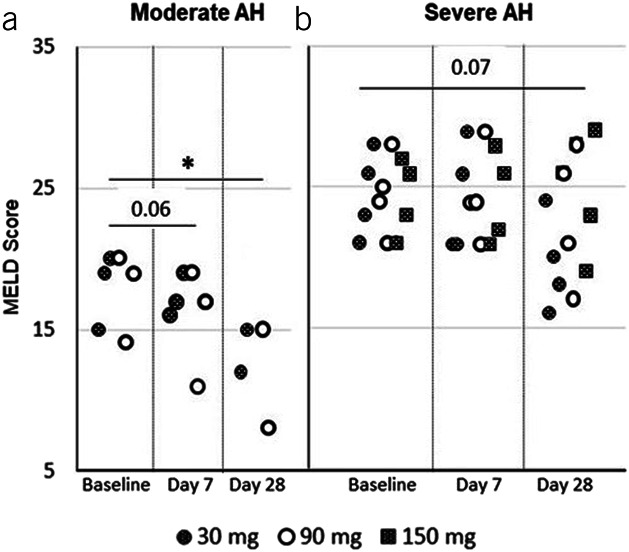

MELD score

Reductions of MELD scores from baseline were observed at day 7 and day 28, especially at day 28 (Figure 4). Subjects with moderate AH showed a statistically significant reduction of MELD scores at day 28 (P < 0.05), and subjects with severe AH had lower MELD scores from baseline at day 28 but not statistically significant.

Figure 4.

MELD scores over time in subjects with AH. MELD scores from individual subjects (who returned for sample collection) were determined at baseline, day 7, and day 28 (end of the study) after the first infusion. Shaded circles represent subjects who received 30 mg of larsucosterol, empty circles are those who received 90 mg of larsucosterol, and shaded squares show those who received 150 mg of larsucosterol. (a, left) Subjects with moderate AH, and (b, right) Subjects with severe AH. *Represents P < 0.05 by t test. AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

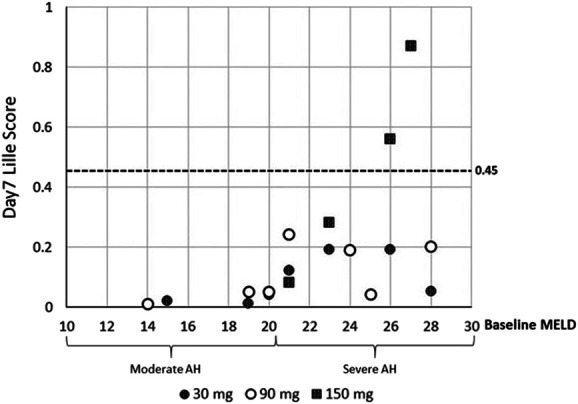

Lille score

Figure 5 shows day 7 Lille score and corresponding baseline MELD score for each subject with available data after larsucosterol treatment. Overall Lille scores were higher in subjects with severe AH (baseline MELD 21–30) than in subjects with moderate AH (baseline MELD 11–20), and the range of these values was also wider in subjects with severe AH. Most subjects, 16 of 18 (89%), had their Lille scores <0.45 (considered as treatment responders). Two subjects with severe AH allocated to 150 mg dose group had day 7 Lille scores ≥0.45.

Figure 5.

Lille scores and baseline MELD scores in subjects with AH. Lille scores were calculated on day 7 from individual subjects who returned for sample collection and were plotted against their corresponding baseline MELD scores. At the baseline, subjects with moderate AH had MELD scores of 11–20, while subjects with severe AH had MELD scores of 21–30. Shaded circles represent subjects who received 30 mg of larsucosterol, empty circles are those who received 90 mg of larsucosterol, and shaded squares show those who received 150 mg of larsucosterol. AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

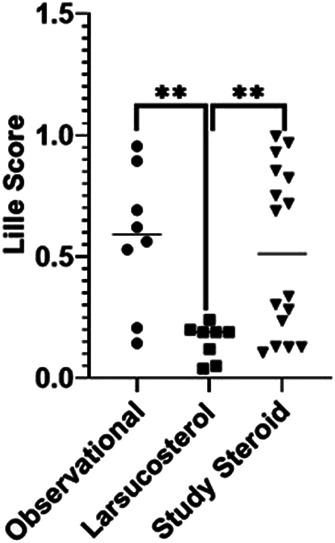

Based on data from multiple in vitro and in vivo studies, doses of 30 and 90 mg were the doses for further evaluation in the phase 2b trial. Lille scores from this subgroup of subjects with severe AH were further analyzed. All 8 subjects with severe AH in the 30 or 90 mg dose cohorts, irrespective of baseline MELD score, were treatment responders (Lille score <0.45). Notably, the 2 subjects with the highest baseline MELD scores responded to study treatment (1 received 30 mg and 1 received 90 mg of larsucosterol). Lille scores from 8 subjects with severe AH who received 30 or 90 mg of larsucosterol were compared with 2 well-matched groups of subjects (n = 8 and n = 16) treated with SOC, including CS, from a contemporaneously conducted DASH Consortium trial (12).

We initially compared this subgroup of larsucosterol-treated subjects with an observational arm from the contemporaneous DASH Consortium trial who received SOC, including CS, because we were not blinded to laboratory tests or treatment. The larsucosterol-treated subjects had a statistically significantly lower Lille score than those in the observational arm (Figure 6). Based on these data, we subsequently chose a well-matched larger group (n = 16) of steroid-treated subjects with severe AH as a parallel comparison arm. These subjects had a 28-day follow-up, while observational subjects generally did not have a 1-month laboratory follow-up. The 16-subject comparison arm had very comparable Lille scores with those of the observational arm, but notably higher Lille scores after 7-day treatment than the larsucosterol-treated subjects (P < 0.01) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Comparative Lille scores of subjects with severe AH from contemporaneous studies. Lille scores at day 7 are shown from selected subjects with severe AH after treatment with SOC, including CS, in an observational arm of the NIH-funded DASH study (n = 8, solid circle); larsucosterol at 30 or 90 mg doses (n = 8, solid square); and SOC, including CS, in a comparison arm of the DASH study (n = 16, solid triangle). **Represents P < 0.01 by t test. AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis; CS, corticosteroids; DASH, Defeat Alcoholic Steatohepatitis; NIH, National Institutes of Health; SOC, standard of care.

Temporal changes in laboratory tests

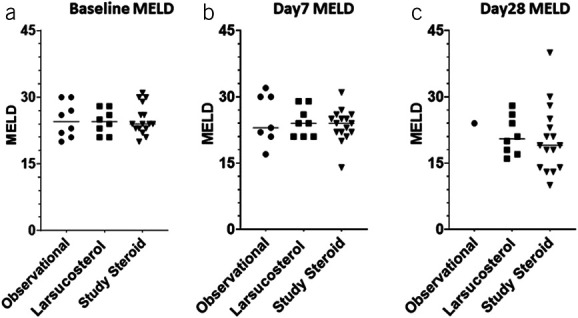

As shown in Figure 7, MELD scores in subjects from all 3 arms, including 8 subjects with severe AH who received 30 and 90 mg of larsucosterol treatment, 8 subjects in the observational arm, and 16 subjects in the parallel comparison arm of the DASH Consortium trial who received SOC treatment (including CS), were comparable at both baseline and day 7. All 3 arms showed a similar decrease in MELD scores at day 28.

Figure 7.

MELD scores over time in subjects with severe AH. MELD scores from subjects with AH were calculated at baseline (a, left), day 7 (b, middle), and day 28 (c, right) after the initiation of treatment. Treatment was SOC, including CS, in an observational arm of the NIH-funded DASH study (n = 8, solid round); larsucosterol at 30 and 90 mg doses (n = 8, solid square); and SOC, including CS, in a larger comparison arm (n = 16, solid triangle) of the DASH study. Only 1 patient in the observational arm had follow-up laboratory tests at day 28. AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis; CS, corticosteroids; DASH, Defeat Alcoholic Steatohepatitis; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; NIH, National Institutes of Health; SOC, standard of care.

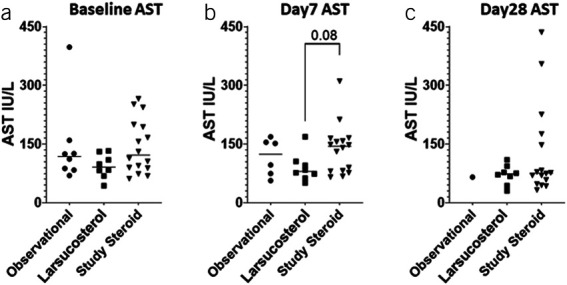

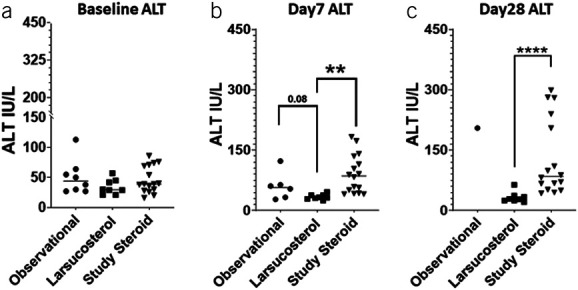

Of interest, both AST (Figure 8) and ALT (Figure 9) decreased rapidly in larsucosterol-treated arm, with ALT being statistically significantly lower than those in the DASH subjects at day 7 (P < 0.01) and day 28 (P < 0.0001). Serum albumin increased progressively (see Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/C933) at day 7 and day 28, although it was not statistically significantly different from those in the DASH arm. Serum creatinine remained stable in all 3 arms over time (see Supplementary Figure S3, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/C933).

Figure 8.

Serum AST levels over time in subjects with severe AH. Serum AST levels (IU/L) were determined at baseline (a, left), day 7 (b, middle), and day 28 (c, right) after treatment with SOC, including CS, in an observational arm of the NIH-funded DASH study (n = 8, solid circle); larsucosterol at 30 and 90 mg doses (n = 8, solid square); and SOC, including CS, in a larger comparison arm (n = 16, solid triangle) from the DASH study. Only 1 patient in the observational arm had follow-up laboratory tests at day 28. AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CS, corticosteroids; DASH, Defeat Alcoholic Steatohepatitis; NIH, National Institutes of Health; SOC, standard of care.

Figure 9.

Serum ALT levels over time in subjects with severe AH. Serum ALT levels (IU/L) were determined at baseline (a, left), day 7 (b, middle), and day 28 (c, right) after treatment with SOC, including CS, in an observational arm of the NIH-funded DASH study (n = 8, solid circle); larsucosterol at 30 and 90 mg doses (n = 8, solid square); and SOC, including CS, in a larger comparison arm (n = 16, solid triangle) of the DASH study. Only 1 patient in the observational cohort had follow-up laboratory tests at day 28. **Represents P < 0.01 by t test. ****Represents P < 0.0001 by t test. AH, alcohol-associated hepatitis; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CS, corticosteroids; DASH, Defeat Alcoholic Steatohepatitis; NIH, National Institutes of Health; SOC, standard of care.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrated excellent safety and tolerability of larsucosterol at 3 doses (30, 90, and 150 mg) evaluated in subjects with AH. The drug exposure was not affected by the disease severity (moderate or severe AH) and was dose proportional. Compared with healthy volunteers, decreased clearance of larsucosterol in subjects with AH was the primary contributing factor to the increased drug exposure observed in these subjects.

Larsucosterol was well-tolerated in this group of subjects with moderate or severe AH. There were no drug-related serious adverse events. Although 3 subjects experienced TEAE, they were mild to moderate and resolved spontaneously. Safety of larsucosterol in subjects with severe AH is being monitored in the follow-up, placebo-controlled, 300-subject AHFIRM trial.

Although this study was small and without a control arm, the results were encouraging and compared favorably with 2 matched control arms treated with SOC, including CS. Most notably, all subjects, 7 moderate AH with MELD scores 11–20 and 12 severe with MELD scores 21–30, treated with larsucosterol survived the 28-day study period, with the disease that typically has an overall 1-month mortality rate of approximately 15%–26% (2,3,5).

Subjects enrolled in this pilot study had an upper MELD score cutoff at 30. The same cutoff is also used in the ongoing phase 2b (AHFIRM) trial to demonstrate benefits of larsucosterol over the current SOC, including the use of CS, for severe AH. CS is generally used in severe AH if a patient has an MELD score >20 without contraindications. Although the STOPAH trial did not observe long-term benefits of CS, it did show a moderate reduction of short-term mortality, which, however, was mainly observed in patients with MELD scores <30 (5).

Most of the subjects (74% of all subjects and 67% of those with severe AH) were discharged ≤72 hours after receiving only 1 infusion. Serum total bilirubin levels were decreased at day 7 after larsucosterol treatment, MELD scores improved at day 28, and day 7 Lille scores were <0.45 in 16 of 18 (89%) subjects. These combined efficacy signals added credence to the observed clinical responses.

AH is a serious complication of heavy alcohol consumption with significant morbidity and mortality. Numerous agents have been evaluated but failed to improve outcomes. In fact, the outcome of AH has barely changed in the past 50 years. Enthusiasm for pentoxifylline and/or CS has declined after the STOPAH trial, which showed no long-term benefit of these drugs (5). Our data from this pilot study showed that larsucosterol treatment was not only safe but also no deaths occurred in these subjects with AH, including severe AH. In addition, the Lille scores compared favorably with well-matched subjects treated with SOC, including CS, from the DASH Consortium trial. The efficacy of larsucosterol, including 90-day mortality, is being assessed in the well-powered (300 subjects), double-blinded, randomized, and placebo controlled AHFIRM trial.

More and more studies have suggested that epigenetic dysregulation, including abnormal DNMT activities and aberrant DNA methylation, is associated with certain diseases. In AH pathogenesis, Argemi et al (8) investigated factors involved in the development of liver failure using liver samples from patients with AH. Their results showed profound changes in hepatic DNA methylation and transcriptome, suggesting the involvement of epigenetic factors in the disease. Remarkably, expressions of DNMT1 and 3a were greatly increased in the livers of patients with AH compared with those in normal subjects or patients with other liver disease.

Larsucosterol, endogenously as 25HC3S, was discovered when the mitochondrial membrane STARD1 was overexpressed, suggesting the production of the molecule was induced in response to intracellular signals. In a recently published study by Wang et al (11), 25HC3S bound to and inhibited DNMT1, 3a and 3b, thereby inhibiting high glucose-induced DNA hypermethylation and affecting >1,000 genes involved in approximately 80 signaling pathways in cultured hepatocytes. It was proposed that 25HC3S, as an endogenous molecule, may modulate cellular energy/lipid metabolism, cell proliferation/differentiation, cell death/survival, and tissue regeneration by regulating DNMT activities.

This trial is a pilot study and uses contemporaneous controls. It was not designed to evaluate gender or dose effects or to compare with other agents.

In summary, data from this pilot study showed promising efficacy signals of larsucosterol in subjects with AH, including subjects with severe AH. There is also a strong scientific rationale for further evaluating larsucosterol for severe AH.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: WeiQi Lin, MD, PhD, and Craig J. McClain, MD.

Specific author contributions: C.J.M., V.V., and W.Q.L. drafted the manuscript. T.H., L.S., S.L.F., P.M., and M.C.C. were PI of the study. C.J.M., V.V., M.M., B.B., L.N., G.S., A.M., and S.D. were PI and data analysts of the contemporaneous DASH trial. J.S., C.B., D.S., W.K., J.E.B., and W.Q.L. conceived, designed, and executed the trial.

Financial support: DURECT Corporation sponsored larsucosterol phase 2a trial. Funding was provided by the NIH (U01AA026934, U01AA021893-01, and P50AA024337) to C.J.M.

Potential competing interests: None to report.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Paul Kwo, Vijay Shah, Suthat Liangpunsakul, Richard Holubkov, Robert Gordon and his team, Julie Fergus, Gwenaelle Mille, Andy Miksztal, Steve Helmer, Judy Joice, Linval Depass, Jim Matriano, Jill Burns, John Culwell, Terrence Blaschke, Felix Theeuwes, and Norman Sussman for their valuable contribution to the study or review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL accompanies this paper at http://links.lww.com/AJG/C933

Contributor Information

Tarek Hassanein, Email: thassanein@researchscrc.com.

Craig J. McClain, Email: craig.mcclain@louisville.edu.

Vatsalya Vatsalya, Email: vatsalya.vatsalya@louisville.edu.

Lance L. Stein, Email: lance.stein@piedmont.org.

Steven L. Flamm, Email: sflamm3@outlook.com.

Matthew C. Cave, Email: matt.cave@louisville.edu.

Mack Mitchell, Jr, Email: Mack.Mitchell@UTSouthwestern.edu.

Bruce Barton, Email: Bruce.Barton@umassmed.edu.

Laura Nagy, Email: nagyl3@ccf.org.

Gyongyi Szabo, Email: gszabo1@bidmc.harvard.edu.

Arthur McCullough, Email: MCCULLA@ccf.org.

Srinivasin Dasarathy, Email: DASARAS@ccf.org.

Jaymin Shah, Email: jaymin.pcs@outlook.com.

Christina Blevins, Email: christina.blevins@durect.com.

Deborah Scott, Email: Deborah.Scott@durect.com.

William Krebs, Email: William.Krebs@durect.com.

James E. Brown, Email: jim.brown@durect.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crabb DW, Im GY, Szabo G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol-associated liver diseases: 2019 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2020;71(1):306–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes E, Hopkins LJ, Parker R. Survival from alcoholic hepatitis has not improved over time. PLoS One 2018;13(2):e0192393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morales-Arraez D, Ventura-Cots M, Altamirano J, et al. The MELD score is superior to the Maddrey Discriminant Function score to predict short-term mortality in alcohol-associated hepatitis: A global study. Am J Gastroenterol 2021;117(2):301–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marlowe N, Lam D, Krebs W, et al. Prevalence, co‐morbidities, and in‐hospital mortality of patients hospitalized with alcohol‐associated hepatitis in the United States from 2015 to 2019. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2022;46(8):1472–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2015;372(17):1619–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabo G, Kamath PS, Shah VH, et al. Alcohol-related liver disease: Areas of consensus, unmet needs and opportunities for further study. Hepatology 2019;69(5):2271–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arab JP, Sehrawat TS, Simonetto DA, et al. An open-Label, dose-escalation study to assess the safety and efficacy of IL-22 agonist F-652 in patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis. Hepatology 2020;72:441–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Argemi J, Latasa MU, Atkinson SR, et al. Defective HNF4alpha-dependent gene expression as a driver of hepatocellular failure in alcoholic hepatitis. Nat Commun 2019;10:3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ren S, Hylemon P, Zhang ZP, et al. Identification of a novel sulfonated oxysterol, 5-cholesten-3β,25-diol 3-sulfonate, in hepatocyte nuclei and mitochondria. J Lipid Res 2006;47(5):1081–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren S, Ning Y. Sulfation of 25-hydroxycholesterol regulates lipid metabolism, inflammatory responses, and cell proliferation. Am J Physiol-Endoc Met 2014;306(2):E123–E130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Lin WQ, Brown JE, et al. 25-Hydroxycholesterol 3-sulfate is an endogenous ligand of DNA methyltransferases in hepatocytes. J Lipid Res 2021;62:100063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dasarathy S, Mitchell MC, Barton B, et al. Design and rationale of a multicenter defeat alcoholic steatohepatitis trial: (DASH) randomized clinical trial to treat alcohol-associated hepatitis. Contemp Clin Trials 2020;96:106094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szabo G, Mitchell M, McClain CJ, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist plus pentoxifylline and zinc for severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. Hepatology 2022;76(4):1058–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crabb DW, Bataller R, Chalasani NP, et al. ; on behalf of the NIAAA Alcoholic Hepatitis Consortia. Standard definitions and common data elements for clinical trials in patients with alcoholic hepatitis: Recommendation from the NIAAA Alcoholic Hepatitis Consortia. Gastroenterology 2016;150(4):785–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]