Abstract

Fiber-reinforced polymers (FRP) are widely utilized to improve the efficiency and durability of concrete structures, either through external bonding or internal reinforcement. However, the response of FRP-strengthened reinforced concrete (RC) members, both in field applications and experimental settings, often deviates from the estimation based on existing code provisions. This discrepancy can be attributed to the limitations of code provisions in fully capturing the nature of FRP-strengthened RC members. Accordingly, machine learning methods, including gene expression programming (GEP) and multi-expression programming (MEP), were utilized in this study to predict the flexural capacity of the FRP-strengthened RC beam. To develop data-driven estimation models, an extensive collection of experimental data on FRP-strengthened RC beams was compiled from the experimental studies. For the assessment of the accuracy of developed models, various statistical indicators were utilized. The machine learning (ML) based models were compared with empirical and conventional linear regression models to substantiate their superiority, providing evidence of enhanced performance. The GEP model demonstrated outstanding predictive performance with a correlation coefficient (R) of 0.98 for both the training and validation phases, accompanied by minimal mean absolute errors (MAE) of 4.08 and 5.39, respectively. In contrast, the MEP model achieved a slightly lower accuracy, with an R of 0.96 in both the training and validation phases. Moreover, the ML-based models exhibited notably superior performances compared to the empirical models. Hence, the ML-based models presented in this study demonstrated promising prospects for practical implementation in engineering applications. Moreover, the SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) method was used to interpret the feature's importance and influence on the flexural capacity. It was observed that beam width, section effective depth, and the tensile longitudinal bars reinforcement ratio significantly contribute to the prediction of the flexural capacity of the FRP-strengthened reinforced concrete beam.

Keywords: Fiber-reinforced polymers, Flexural capacity, Machine learning, Gene expression programming, Multi-expression programming

1. Introduction

Recently, the deterioration of structural components like buildings and bridges due to aging, material degradation, inadequate maintenance, and earthquakes have spurred researchers to develop effective and cost-efficient methods for repairing these structures. Various approaches are available to rehabilitate deteriorated structures, including the replacement of degraded members, externally bonded steel plates, adding supplementary elements, external post-tensioning, and concrete jackets or using steel [1,2]. While these conventional repair techniques can enhance the stiffness and strength of undesirable concrete building structures, they often result in increased dead load and need substantial time for implementation. Consequently, there is a growing demand to search for alternative techniques or materials for repairing or reinforcing deficient structural concrete elements.

A viable alternative method involves the application of fiber-reinforced polymers (FRP) for the purpose of retrofitting RC structures. Recently, FRP strengthening has been rapidly adopted due to its notable benefits, especially in terms of efficiency and cost-effectiveness [3,4]. FRP composites have emerged as the preferred option for reinforcing structures owing to their lightweight characteristics, exceptional strength, resistance to corrosion, and long-lasting durability. With the ability to be conveniently fabricated into different shapes, FRP materials offer convenience in construction applications [[5], [6], [7]]. The advantages of FRP reinforcement extend beyond its mechanical properties, as it is increasingly considered a substitute or enhancement to traditional construction materials in various sectors. The accurate prediction and assessment of the strengthening effect in RC beams using FRP can be attributed to the utilization of two principal methods: externally bonded (EB) and near-surface-mounted (NSM) techniques [8,9]. In practical applications, the precise forecast of the capacity of RC beam strengthened by FRP FRP is of great significance for the comprehensive assessment of the strengthening effectiveness and design [10].

Estimating the flexural capacity (Mu) of FRP-strengthened RC beams traditionally involves theoretical deductions and experimental studies [[11], [12], [13]]. However, these approaches are often time-consuming and prone to inherent errors due to assumptions and simplifications, such as the plane section assumption [14]. The plane section assumption simplifies stress analysis by focusing on in-plane stresses induced by loads while neglecting perpendicular stresses. In cases with significant out-of-plane stresses, a full 3D analysis may be needed for accuracy [15]. However, this simplification may introduce errors, primarily when substantial third-direction stresses result from in-plane loads [16]. Conversely, machine learning (ML) can enhance precision in handling such intricate and complex scenarios. Moreover, the lack of availability of actual data for validation restricts the generalizability of the models. As an alternative, finite-element simulation has been explored for prediction purposes [17,18]. However, accurately estimating numerous model parameters remains challenging, leading to prediction precision uncertainties. Hence, there persists an ongoing requirement to advance a precise and reliable technique for estimating flexural strength, aiming to enhance the accuracy and reliability of such predictions.

With the growth of soft computing methods, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a valuable tool in various applications in structural engineering. Its utilization spans multiple areas, including structural design and analysis, damage detection, the resistance of structural members under different actions, fire resistance of structures, structural health monitoring, and concrete's mechanical properties and mix design [[19], [20], [21]]. ML models have been employed to estimate collapse fragility, structural response demands, and performance metrics, among other factors, providing valuable insights into structural engineering for decision-making and optimization. The ability of ML algorithms to analyze large datasets and identify complex patterns has proven beneficial in improving the accuracy and efficiency of structural predictions and assessments. For instance, Mangalathu et al. [22] utilized ML methods to assess the shear strength of RC samples and their failure mechanism. Perera et al. [23] have established a neural network model for forecasting the shear strength of RC beams. Additionally, Mashrei et al. [24] introduced a back-propagation neural network (BNN) approach to estimate the strength of the bond between FRP and concrete joints. Naser [14] employed a combination of genetic algorithms and artificial neural networks (ANN) to assess the ultimate bending capacity of RC beams reinforced with FRP. Moreover, Abuodeh et al. [25] presented BNN model for the shear strength estimation of RC beams strengthened by reinforced FRP sheets externally. Amin et al. [26] utilized tree-based ensemble techniques to predict the flexural capacity of FRP-reinforced RC beams. In contrast to traditional empirical formulas and other approaches, ML-based techniques do not depend on assumptions based on physical or mathematical models. Instead, it learns patterns solely from experimental data. As a result, it effectively overcomes the limitations associated with conventional prediction methods. The findings consistently demonstrated that ML-based models consistently achieved higher levels of prediction accuracy compared to empirical models.

Numerous investigations have analyzed and proposed numerical models to anticipate the flexural response of FRP-reinforced bars concrete beams. However, many of these developed techniques tend to be intricate and complex. Recently, researchers have turned to ANN as an alternative approaches for predicting the behavior of RC components, particularly in situations where code standards are unavailable. Among these approaches, evolutionary algorithms such as GEP and MEP hold an advantage over ANN because they can construct precise prediction models even with a relatively small database [[27], [28], [29]]. However, despite these advancements, there is still a disagreement in the current literature concerning the development of a concise predictive mathematical equation that effectively and accurately estimates the flexural behavior of FRP-strengthened RC beams. Furthermore, the ANN technique is considered a black box, showing a lack of interpretability and explainability [30]. In contrast, the GEP and MEP algorithms are not black-box models because the internal mechanisms and operations are well-defined and understood [31,32]. They follow specific rules and genetic functions, such as mutation, selection, and crossover, which are explicitly programmed [28,33]. Researchers and practitioners can see how the algorithms evolve and generate solutions. In addition, SHAP-based interpretation was provided in this study to provide an enhanced explanation of the predictive developed models.

This research focuses on developing accurate and valid predictive models based on GEP and MEP techniques. For the model development, a total of 200 data points were utilized. The most significant input features were utilized for the development of both models. Various statistical parameters were utilized to assess the developed model's accuracy. The model's estimation performance was compared with traditional linear regression models and empirical estimation equations. Furthermore, the utilization of the Shapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) technique was presented to provide interpretations regarding the significance and influence of input features on the flexural capacity RC beam.

2. Overview of ML algorithms

2.1. Gene expression programming

Genetic algorithm (GA) is a type of evolutionary technique that utilizes a stochastic methodology to explore and enhance solutions for particular problems, drawing inspiration from genetic processes [34]. In 1985, Cramer presented genetic programming (GP), a technique that Koza expanded and refined to accommodate various sizes and configurations [35]. Later on, Ferreira introduced Gene Expression Programming (GEP) as a computer programming methodology based on the genotype-phenotype concept [36]. GEP employs a tree-like structure to construct intricate computer models capable of learning and evolving by modifying their shapes, sizes, and configurations, mirroring the adaptive characteristics observed in natural biological organisms. This approach, in accordance with Darwin's theory of evolution and the principles of Mendel's genetic theory, embodies the philosophy of computational intelligence [37]. GEP employs linear chromosomes with predetermined lengths to encode programs that address complex problems. One notable advantage of the GEP model is its potential to offer accurate predictions using straightforward mathematical equations, enhancing prediction efficiency [38]. Fig. 1 illustrates the comprehensive process flowchart of the GEP model.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of GEP technique.

A typical chromosome structure has a head section connecting terminal symbols or functions and a tail section connecting only terminal symbols. The operational mechanism of the GEP technique is depicted in Fig. 2. Referring to the process diagram, the estimation process in GEP starts with the generation of random chromosomes by representing defined values according to the Karva language. To solve a problem using GEP, four essential elements must be known: the terminal set (which encompasses input parameters and constants) and the function, GEP governing features (such as mutation, size of the population, and crossover), termination conditions, and the fitness function [39,40]. Garg et al. [41] suggested that the functioning mechanism of the GEP technique can be split into several phases.

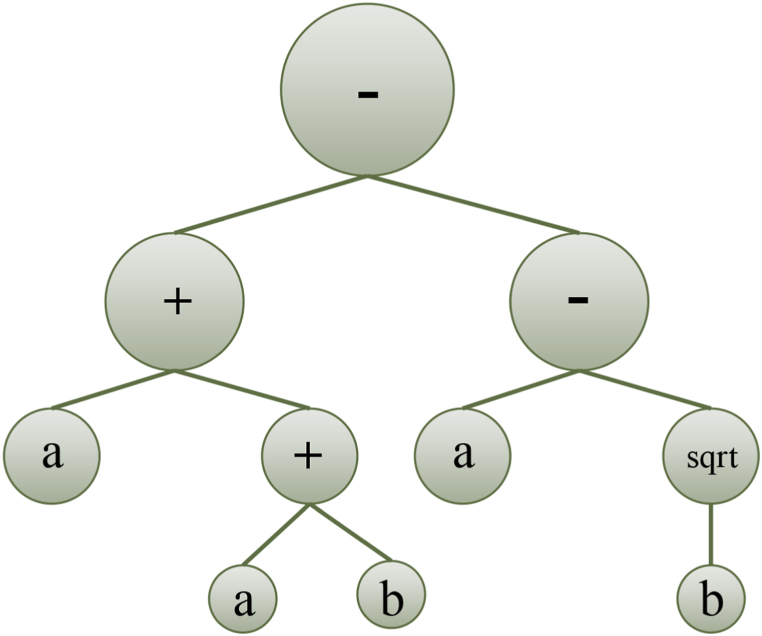

Fig. 2.

Chromosome expression tree.

During the initialization phase, the population is generated according to the predefined function and terminal settings. The chromosomes can be readily transformed into algebraic equations, having fixed lengths [42]. Following that, the chromosomes undergo a transformation process into expression trees (ETs) of diverse shapes and sizes. The comprehension of the gene language syntax or pattern is analogous to understanding the language employed by expression trees (ETs) [36]. The genes can be combined through linking functions constituting the chromosome: subtraction, addition, division, and multiplication [43]. During the evolution phase, the generation of the population is assessed based on the criteria: the fitness function and the maximum number of iterations or generations. The decision to increase the number of expression trees (ETs) is determined by either indicating the occurrence of overfitting or meeting the termination condition of the iterative process. Various selection methods, including ranking selection, the roulette wheel approach, the elite strategic approach, greedy over-selection, and tournament selection, are utilized to identify viable chromosomes from the iteration and move them to the subsequent generation [44,45]. The program terminates if the population performance satisfies the desired criteria or if the highest number of iterations is attained. Conversely, if the termination condition is not satisfied, a new generation of the population is generated iteratively by employing three genetic functions: reproduction of chromosomes, crossover (illustrated in Fig. 3a), and mutation (depicted in Fig. 3b). This process continues until the threshold condition is met, leading to the acquisition of the optimal solution [46,47].

Fig. 3.

GEP chromosome tree with LISP language for (a) crossover and (b) mutation.

2.2. Multi expression programming

The MEP technique is a sophisticated form of linear GP that utilizes linear chromosomes to code solutions. The working operation of MEP, akin to that of GEP, is visually presented in Fig. 4, providing a clear illustration of its functioning. A distinctive characteristic of MEP, which sets it apart as a comparably recent branch of GP, is capable of coding multiple solutions within an exclusive chromosome. The optimum solution is subsequently determined by comparing the fitness values among these encoded programs [48,49]. Oltean and Grosan [50] employed the binary environment selection process; two parents are chosen and undergo recombination to generate two separate offspring. The iterative operation resumes until the termination criteria are satisfied, aiming to obtain the best program. Throughout this process, the offspring undergo mutation. Similar to GEP, the MEP model permits the adjustment of several parameters, such as the sub-population size and range, function set, crossover probability, and algorithm length. These parameters are crucial components in developing the MEP model [51]. Increasing sub-populations and their respective sizes in the MEP model results in more intricate evaluations and computationally demanding calculations, particularly population size, representing the total count of programs. Furthermore, the algorithm length notably affects the generated mathematical expression length. The architecture of the MEP model is visually illustrated in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4.

Process flowchart of MEP.

Fig. 5.

MEP architecture.

3. Methodology

3.1. FRP strengthening RC beam

The primary methods for RC beam strengthening employing FRP are the NSM and EB methods, as shown in Fig. 6a and b, respectively. The EB method, which involves bonding FRP to the bottom of the beam, is the most commonly employed. It is relatively simple to implement but has a higher risk of FRP detachment, thereby reducing the FRP strength. In contrast, the NSM method provides enhanced utilization of FRP strength as the FRP is embedded within a groove at the beam bottom, reducing the likelihood of detachment. However, this method entails intricate procedures and may result in damage to the cover concrete beam. Both methods effectively augment the RC beam flexural strength by enabling the tensile reinforcement and FRP to bear the tensile forces jointly. Fig. 6 presents the layout of these two strengthening techniques, offering a visual representation of their arrangements.

Fig. 6.

Strengthened RC beam with FRP (half span).

3.2. Data collection

A robust and reliable prediction model relies on establishing a comprehensive database. This study incorporates the collection of experimental data pertaining to the reinforcement of rectangular RC beams utilizing FRP, which has been sourced from a variety of scholarly research findings [[7], [10], [11], [13], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114]] collected by Zhang et al. [115]. The database consists of 103 sets of EB data and 97 NSM data sets. To identify the key input features, the study considered the major characteristics influencing the flexural strength of FRP-strengthened RC beams.

The selected input variables for the model included the beam width (b), FRP tensile strength (ff), section effective depth (h0), longitudinal bars tensile reinforcement ratio (ρst), FRP plate/sheet/NSM ratio (ρf), longitudinal bars compressive reinforcement ratio (ρsc), FRP modulus (Ef), concrete compressive strength (fc), reinforcement yield strength (fy), and strengthening method (T). Fig. 6 illustrates RC beams strengthened with FRP, covering half the span. The flexural capacity of the RC beam (Mu) is considered as response parameter. Table 1 provides statistical evaluation for the input variables and output property (Mu) in the FRP-strengthened RC beam data set. It presents each variable's standard deviation (SD), median, maximum, minimum, and mean values. The overall methodology followed in the current study is illustrated in Fig. 7.

Table 1.

Statistical values of the data sets.

| Statistics | Input variables |

Output |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fc(MPa) | fy(MPa) | ff (MPa) | Ef(GPa) | st(%) | sc(%) | f(%) | b (mm) | ho(mm) | T | Mu(kN.m) | |

| Mean | 40.03 | 467.36 | 2379.41 | 150.05 | 0.81 | 0.43 | 0.23 | 161.73 | 225.14 | 1.48 | 48.44 |

| Median | 38.27 | 452 | 2400 | 159 | 0.69 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 150 | 222 | 1 | 41.01 |

| Standard Error | 0.84 | 7.01 | 85.24 | 4.94 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 3.46 | 3.86 | 0.04 | 2.26 |

| Sample Variance | 140.07 | 9830.92 | 1453254 | 4873.98 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 2397.42 | 2982.31 | 0.25 | 1025.56 |

| Mode | 40 | 414 | 2740 | 165 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 150 | 243 | 1 | 59.2 |

| Standard Deviation | 11.84 | 99.15 | 1205.51 | 69.81 | 0.45 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 48.96 | 54.61 | 0.50 | 32.02 |

| Skewness | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.33 | −0.34 | 1.83 | 2.30 | 2.67 | 2.41 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.18 |

| Kurtosis | 0.26 | 0.72 | −0.38 | −0.88 | 4.23 | 8.62 | 8.68 | 7.79 | −0.36 | −2.02 | 1.26 |

| Minimum | 17.5 | 242.2 | 512 | 22 | 0.23 | 0 | 0.02 | 100 | 118 | 1 | 5.79 |

| Maximum | 79.64 | 788 | 4950 | 271 | 2.58 | 2.58 | 1.46 | 500 | 370 | 2 | 160.2 |

| Range | 62.14 | 545.8 | 4438 | 249 | 2.35 | 2.58 | 1.44 | 400 | 252 | 1 | 154.41 |

Fig. 7.

Methodology flow chart.

The data values across the different variables in the obtained data exhibit a significantly wide range and dispersion. The data sets obtained were randomly partitioned into validation and training sets to facilitate the development of a robust model. The training set was employed to train the developed model, whereas the validation set was utilized to assess its effectiveness following the training phase. Consequently, the training set comprised 140 data points (70 %), and the validation set included 60 data points (30 %). To account for the diverse magnitudes and units of the input variables, the data within the training dataset underwent a normalization process prior to model training. This normalization process ensures smoother and easier convergence when seeking the optimal solution, thereby improving the performance and speed of the model. The frequency distribution histograms of variables are provided in Fig. 8a–k. In addition, correlation heat map is provided in Fig. 9. It can be noticed that flexural capacity has highest positive correlation (r) with effective depth (r = + 0.73) and beam width (r = +0.59).

Fig. 8.

Frequency distribution histograms of inputs and input.

Fig. 9.

Correlation heat map of the variables.

3.3. Model development

Appropriate variable selection is a key step in the development of a robust prediction model. The GEP technique fitting parameters were decided by considering suggestions from prior research and conducting several test runs. The GEP model development encompasses three sets of fitting parameters: genetic operators, numerical constants, and general model parameters. The standard parameters encompass several aspects, including population size (representing the count of chromosomes), number of genes, set of functions, head size, and the connecting operator. The population size directly influences the duration of the process. This study utilized a population size of 1000 for GEP modeling. The head size serves as a regulator for the model's structure generated by the program. It determines the number of sub-ETs, while the gene count determines the complication of each term. In this study, the head size for the GEP model was set at 10, and the gene number was set at 4. Detailed descriptions of the GEP setting parameters, along with genetic operators, are provided in Table 2. The GEP-based algorithm was executed using GeneXpro Tool 5.0.

Table 2.

Parameters setting of the GEP model.

| Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| General | |

| Genes | 4 |

| Head size | 10 |

| Chromosomes | 1000 |

| Linking function | Multiplication |

| Set of functions | +, -, *,/, Exp, Ln, Inv, x2, x3, x4, x5, 3Rt, 6Rt |

| Numerical constants | |

| Constant per gene | 10 |

| Upper bound | 10 |

| Data type | Floating-point |

| Lower bound | −10 |

| Genetic operators | |

| Mutation | 0.00138 |

| Permutation | 0.00546 |

| Inversion rate | 0.00546 |

| Random cloning | 0.00102 |

| IS transportation rat | 0.00546 |

| RIS transportation rate | 0.00546 |

| Gene transportation rate | 0.00277 |

| Recombination rate | 0.00277 |

| RNC mutation | 0.00206 |

| Dc mutation | 0.00206 |

In MEP modeling, it is crucial to provide several MEP setup parameters to develop a robust model. These setup variables were set based on recommendations and multiple initial runs [116]. The population size determines the number of generated programs. A large population size results in a more complex and accurate model, but convergence takes longer. However, expanding the population size beyond a certain range can lead to overfitting the model [27]. Table 3 displays the selected setting variables for the developed MEP model. The available functions in the model include basic operators such as addition, division, multiplication, and subtraction. The generation number establishes the desired level of precision that the model should attain before the termination of the process. Running the algorithm for multiple generations helps to obtain a simulation model with the lowest errors. Different parameter combinations were tested to select the optimized model, ultimately choosing the combination that yielded the model with the smallest error values. Overfitting is a significant issue in machine learning modeling, referring to a situation where the model demonstrates strong performance on the original data but encounters difficulties when applied to new, unseen data. To mitigate this concern, it is suggested to assess the efficiency of the generated model on the unseen data, allowing for an evaluation of its generalization capabilities [117,118]. Accordingly, the data is divided into two categories. A separate validation set, which was not utilized in the developmental process of the model, was used to assess the effectiveness of the algorithm. The data was split into 70 % for training and 30 % for validation. The generated models demonstrated exceptional performance across all datasets. The MEPX v 1.0 software tool was employed to execute the MEP model development process.

Table 3.

Setup for MEP model development.

| Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| No. of subpopulations | 50 |

| Subpopulation size | 250 |

| Code length | 50 |

| Tournament size | 2 |

| Functions probability | 0.5 |

| Crossover probability | 0.9 |

| Mutation probability | 0.01 |

| Variables probability | 0.5 |

| Functions | +, -, *,/, Power, Sqrt, Exp, Pow10, Sin, Cos, Inv(1/x), ACos, Atan, Tan, ASin, |

3.4. Model evaluation indicators

Several statistical parameters are employed to assess the validity and efficiency of the ML models, including R, MAE, RMSE, MSE, RRMSE, and the performance index (), as expressed in Equations (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7). It is essential to highlight that MSE, MAE, and RMSE are widely used statistical measures in machine learning to assess error levels [119]. Lower RMSE, MSE, and MAE values signify enhanced efficiency of the generated model.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Where ei represents the ith original value, mi represents the ith forecasted value, and n indicates the number of data points. Furthermore, and correspond to the mean of the predicted and actual experimental outcomes, respectively.

A greater value of the correlation coefficient (R) reveals the accuracy of the model. R quantifies the correlation between actual and model data [120]. R-value above 0.8 signifies a robust relation between the experimental and estimated values, indicating a strong relation between the two [121,122]. However, the R-value does not account for the impact of division, multiplication, or scaling by a fixed number on the output. Hence, R alone is insufficient to assess the overall efficiency of the model. RMSE and MAE compute the average magnitude of errors, each with significance. In RMSE, errors are squared prior to averaging, giving more weight to higher errors. A higher RMSE value reveals the need to minimize estimates with substantial errors. Conversely, MAE assigns relatively less importance to weighty errors and is consistently lower than RMSE. Furthermore, the generated model underwent external validation based on recommended standards, as detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

External validation conditions.

3.5. Interpretability of the models

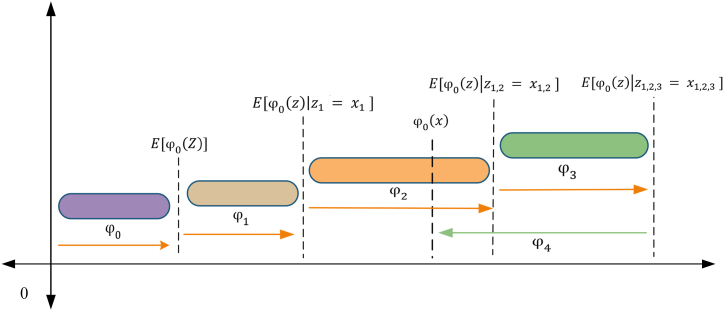

SHAP is a methodology that originates from game theory and is employed to elucidate the effectiveness of an ML model. It creates an understandable model by adopting an additive attribute criterion approach, wherein the developed ML algorithm is represented as a linear combination of input features. In the context of a model with input parameters x = (x1, x2, …, xp), where p represents the input features number, and the explanation model g() for the actual model f(x) is expressed by simplifying the input as :

| (8) |

In Equation (8), 0 denotes the constant value for all missing inputs, and p represents the number of input parameters. The correlation between the inputs and x is defined by the mapping function x = hx(). Fig. 10 illustrates Equation (8), where 0, 1, 2, and 3 increase the estimated value of g, while 4 lowers it. According to Lundberg and Lee [126], Equation (8) has a unique solution that exhibits desirable characteristics: consistency, local accuracy, and missingness. The principle of local accuracy necessitates the model to estimate an output corresponding to the combined feature attributions. This, in turn, demands that the model aligns with the output of function "f" when provided with the simplified input . Missingness guarantees no importance is employed to missing attributes, which is satisfied when xi = 0 implies = 0i. Consistency ensures that changing an attribute with a more significant effect will not lower the criterion allocated to that attribute. The graphical illustration of SHAP is shown in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

SHAP attributes.

SHAP provides effective interpretations for machine learning models. Various methods can approximate SHAP values, including Tree SHAP, Kernel SHAP, and Deep SHAP. SHAP interaction values ensure consistent interpretations of relationship impacts for individual estimations. One notable advantage of SHAP values is their local and global interpretability. Unlike existing feature importance measures in ML techniques, SHAP can determine whether each input attribute contribution is negative or positive. Each data point can also have its corresponding SHAP value, allowing for the model's global and local interpretability. Various researchers in the literature also describe more comprehensive explanations of SHAP [126,127].

4. Results and discussion

The GeneXpro tool was employed to generate expression trees (ETs) for the proposed GEP algorithm, as illustrated in Fig. 11. Subsequently, these ETs were interpreted to derive an empirical formula for estimating the flexural capacity of the FRP-strengthened RC beam. This formulation utilizes fundamental arithmetic operators such as addition, subtraction, and multiplication, as well as mathematical functions such as +, -, *,/, Exp, ln, Inv, x2, x3, x4, x5, 3Rt, log, and 6Rt. In addition, multiplication was employed as a linking function.

Fig. 11.

Expression trees of the GEP model.

4.1. GEP formulation

Based on the expression trees, a simplified mathematical expression is formulated to estimate the flexural capacity of the FRP-strengthened RC beam, denoted by Equation (9). The proposed empirical formulation based on GEP has the potential to forecast the flexural capacity accurately.

| (9) |

Where,

4.2. Performance of models

This section provides an assessment of the model's efficiency, including statistical analysis, a comparison of regression slopes, and an evaluation of errors associated with the ML-generated models.

4.2.1. Regression slope comparison

This section evaluates the developed model's accuracy by analyzing the regression line slope generated from actual values plotted on the x-axis against estimated values on the y-axis, as shown in Fig. 12, Fig. 13. This approach is commonly used by researchers [28,38,128,129] to assess the precision of ML models. Fig. 12 shows that the developed GEP algorithm recorded regression slopes of 0.97 and 0.91 for the training and validation set, respectively. Similarly, from Fig. 13, these values were noted for the MEP model as 0.85 and 0.60 for the training and validation data sets, respectively. The GEP model demonstrated regression slopes greater than 0.8 for validation and training, indicating a superior correlation between actual and estimated values. Conversely, the MEP model exhibited a relatively lower slope for the validation set. Therefore, the GEP-developed model demonstrated more robustness than the MEP model.

Fig. 12.

Comparison of actual ultimate flexure strength with GEP.

Fig. 13.

Comparison of Actual ultimate flexure strength with MEP.

4.2.2. Error analysis

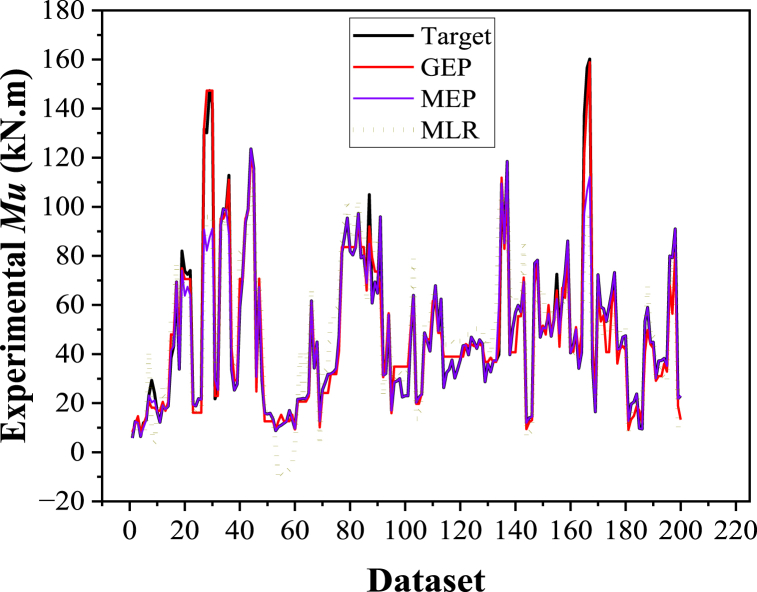

Fig. 14, Fig. 15 depict an error analysis of the generated model, presenting an error histogram and the actual results followed by the corresponding model estimations. This evaluation aligns with previous literature [38,130]. The error histograms in Fig. 14, Fig. 15a reveal that 90 % of the records lie between −10 and 10 (kN m) for the GEP model, while 92.5 % of the records fall within the range of 0–10 (kN m) for the MEP model. Fig. 14, Fig. 15b demonstrate that both models closely match the experimental results.

Fig. 14.

Experimental vs predicted values and error analysis for the GEP model.

Fig. 15.

Experimental vs predicted values and error analysis for MEP model.

Fig. 16, Fig. 17 present the model estimated-to-actual ratio for training and validation data sets, widely used as a statistical evaluation metric for AI models [131,132]. Notably, 110/140 (78.5 %) and 46/60 (76.6 %) prediction records fall within the ±20 % range of relative error for the training and validation data of the GEP model, respectively. Similarly, the MEP model exhibited 127/140 (90.7 %) and 56/60 (93.3 %) predicted values within the ±10 % range of relative error for training and validation, respectively.

Fig. 16.

Predicted/Experimental ratio for GEP; (a) Training, (b) Validation.

Fig. 17.

Predicted/Experimental ratio for MEP; (a) Training, (b) Validation.

4.2.3. Statistical evaluation

Table 5 presents the performance indicators (MAE, RMSE, RRMSE, RSE, R, ρ, OF) of the proposed models. The value of R for both the generated models exceeds 0.96 for both validation and training datasets, with the GEP outperforming the MEP algorithm. Furthermore, most of the statistical error values of the GEP model are lower than those of MEP for both datasets. These lower values indicate the superior performance of both models, particularly the GEP approach. Additionally, the ρ values of the generated GEP model are 0.062 for training and 0.074 for validation, compared to the values obtained with MEP, which are 0.097 and 0.108 for training and validation, respectively. While OF values for the GEP and MEP models are 0.0695 and 0.1041. Consistently, the GEP model demonstrated superior efficiency in terms of RRMSE, RSE, and RMSE compared to the MEP model for both sets. These results validate the robustness of the GEP approach. Furthermore, the models are validated using external validation criteria. The proposed GEP and MEP model satisfied the external validation conditions, as shown in Table 6.

Table 5.

Performance evaluation of the ML-based developed models.

| Model | Subset | MAE | RMSE | RSE | RRMSE | R | ρ | OF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEP | ||||||||

| Training | 4.0853 | 5.9697 | 0.0339 | 0.1232 | 0.9829 | 0.0622 | 0.0695 | |

| Validation | 5.3973 | 7.1330 | 0.0535 | 0.1473 | 0.9813 | 0.0743 | ||

| MEP | ||||||||

| Training | 2.3142 | 9.2813 | 0.0820 | 0.1916 | 0.9631 | 0.0976 | 0.1041 | |

| Validation | 2.4667 | 10.4115 | 0.1139 | 0.2149 | 0.9607 | 0.1085 | ||

Table 6.

External validation.

| Model | k | k' | R2 | Ro2 | Rm | m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEP | 0.972759 | 1.015978 | 0.945634 | 0.981071 | 0.767619 | −0.03748 |

| MEP | 0.916793 | 1.06461 | 0.859696 | 0.902441 | 0.681955 | −0.04972 |

4.3. Comparison of GEP and MEP with MLR

To assess the accuracy of the proposed ML models, a comparison is made with the multi-linear regression (MLR) model. MLR is a statistical approach utilized to create a linear correlation between two or more independent attributes and a dependent attribute. When multiple explanatory variables are relevant, MLR is preferred over simple linear regression. Equation (10) presents the formulation for the MLR for the Mu property of the FRP-strengthened RC beam. Subsequently, the output attained from the MLR model is compared with those from the GEP and MEP models, as shown in Fig. 18.

| (10) |

Fig. 18.

Comparison of ML models with MLR model.

The comparison between the experimental and estimated values of the GEP, MEP, and MLR models for the ultimate flexural capacity (Mu) is depicted in Fig. 18. Both ML models performed exceptionally well in forecasting the Mu. However, the GEP model demonstrated higher precision in predicting flexure strength than the MEP and MLR models. The developed GEP model exhibited exceptional performance during the validation stage and outperformed the MEP and MLR-generated models, indicating that the GEP model possesses significant prediction potential, particularly when working with unseen data. For instance, the RMSEtraining of the GEP model is approximately 31 % and 52 % lower than that of the MEP and MLR models, respectively. On the other hand, the MLR model fails to capture the greater values for the Mu property adequately. This limitation hinders the practical applicability of regression approaches for predictive modeling applications.

4.4. Comparison with empirical models

In this part, the advanced capabilities of the ML-based estimation models are further emphasized through a comparison with empirical models. Various empirical models were employed by Zhang et al. [133] to forecast the flexural capacity of RC beams, as shown in Table 7. While certain formulas can evaluate NSM and EB methods, others particularly apply to the EB method. The predicted results obtained from these formulas were compared against the predictions generated by GEP and MEP models. Furthermore, Table 7 provides detailed information on the performance indicators and their respective values.

Table 7.

Empirical models performance indicators.

| Model | Method | Statistical indicators |

Improvements in performance of the developed GEP model compared to the ACI 440.2R-08 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | RMSE (kN.m) | MAE (kN.m) | |||

| GB50367-2013 | EB | 0.9186 | 14.0762 | 9.4839 | |

| JSCE 2001 | EB | 0.8808 | 16.8692 | 12.0744 | |

| CNR-DT 200 R1 | EB | 0.9189 | 14.0585 | 9.9542 | |

| TR 55 | EB | 0.8859 | 16.5275 | 11.8304 | |

| ACI 440.2R-08 | EB | 0.9347 | 12.6614 | 8.8431 | |

| NSM | 0.8860 | 12.1816 | 12.1816 | ||

| CSA S806-12 | EB | 0.9133 | 14.5115 | 10.2079 | |

| NSM | 0.8113 | 15.3562 | 12.5057 | ||

| GEP (This study) | Training | 0.9829 | 5.9697 | 4.0853 | R increased by 5 % MAE decreased by 54 % RMSE decreased by 51 % |

| Validation | 0.9813 | 7.1330 | 5.3973 | R increased by 5 % MAE decreased by 39 % RMSE decreased by 41 % |

|

Analyzing both tables 5 and 7 present that empirical models demonstrate an R-value ranging from approximately 0.811 to 0.935, whereas ML-based models reveal a higher range of 0.960–0.983. The RMSE values for empirical models range from approximately 12 to 17 kN m, while GEP models show a lower RMSE of approximately 6–7 kN m. Similarly, the MAE values for empirical models range from approximately 8 to 13 kN m, whereas the GEP model demonstrates a lower MAE of about 4–5 kN m. Notably, the ACI 440-based EB technique demonstrates the highest prediction efficiency with an R-value of 0.935, while the CSA S806-12-based NSM technique exhibited the lowest accuracy with an R-value of only 0.811.

Furthermore, the GEP-based model's performance indicators are given in tables 5 and 7. In the training phase, the GEP model achieved an R-value of 0.983, an RMSE of 5.9697 kN m, and an MAE of 4.0853 kN m. Both the GEP model validation and training phase's performance are comparably best, indicating that the GEP-based model outperformed the empirical models significantly. Compared to the excellent empirical model (ACI 440.2R-08), the effectiveness of GEP is much superior, with R increasing by 5 %, RMSE decreasing by 51 %, and MAE decreasing by 54 % in the training set. In the validation set, R increased by 5 %, RMSE decreased by 41 %, and MAE decreased by 39 %. Overall, the results indicate that ML-based prediction models show higher accuracy levels than those based on empirical formulas.

4.5. Comparison with related work

The performance of the developed models was compared with the existing models in the literature for the flexural strength of FRP-strengthened beams. Murad et al. [134] utilized the GEP approach to estimate the flexural strength of the FRP-reinforced beam. Although their GEP model achieved a higher value R (0.979) compared to ACI, the model produced higher errors in terms of MAE (15.23) and RMSE (19.57) compared to ACI formulation. For an accurate prediction model, along with a higher R, the errors should also be minimal. Thus, relying solely on R as an assessment indicator for the generated model is not recommended. When comparing their GEP and ACI models, the ACI model was deemed more precise due to its similar correlation coefficients and lower error values. Furthermore, the disparity in accuracy between the GEP model and the one proposed by Murad et al. [134] can be attributed to variations in the model's parameter configurations. In addition to this, it is important to note that Murad et al. [134] employed a prediction model for beam flexural strength with six input parameters, while our approach integrated ten parameters. These differences in both model settings and the number of input variables underline the unique and tailored nature of the present study GEP model, allowing it to address the complexities and nuances of the problem with a broader information base.

In contrast, the GEP model in the present study outperformed the ACI prediction accuracy, and the MEP model produced comparable, accurate outcomes to ACI. Furthermore, Amin et al. [26] developed models based on gradient boosting trees (GBT) and decision trees (DT). The GBT model estimates the flexural strength of the FRP-strengthened beam with R, MAE, and RMSE values of 0.964, 11.74, and 15.67, respectively. These analyses provided that their model also produces a less accurate accuracy model compared to ACI. Zhang et al. [133] also developed four ensemble models, among which the gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT) model provided excellent performance. Compared to the ACI empirical model, the GBDT model exhibited significantly superior performance. The GBDT model provided notable improvements, with an increase of 9.04 % in the R2 value, a decrease of 31.77 % in RMSE, and a decrease of 43.97 % in MAE within the testing dataset.

5. Enhanced interpretability with SHAP

Previous research lacked the inclusion of machine learning interpretability techniques to elucidate the process by which predictions are made. However, as models grow more complex, there is a need for post-hoc explanations. Consequently, this study incorporated SHAP explanations to uncover the underlying rationale behind predictions and understand the contribution and influence of each variable on the output property. The SHAP concept shares similarities with parametric analysis, wherein the other variables are maintained at constant values while a specific variable is varied to observe its impact on the target attribute. Due to the superior performance of the GEP model compared to the MEP model, the GEP model was selected for SHAP analysis.

Various approaches are available to interpret the results obtained from the prediction model. One such approach involves assessing the importance of input features to understand the influence of different attributes on the estimations of the target output. This assessment is depicted in Fig. 19a, where the results are obtained by calculating the average Shapley values across the entire dataset. It can be observed that beam width (b), the effective depth of section (ho), and the reinforcement ratio of tensile longitudinal bars (ρst) significantly contribute to the prediction of flexural strength of the FRP-strengthened beam, as illustrated in Fig. 19a. The rest of the input features manifest the least contribution to the output prediction. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the combined average absolute SHAP value of b, ho, and ρst accounts for approximately 83.13 % of the total SHAP value and represents five times greater significance than the average SHAP value of the remaining input variables.

Fig. 19.

SHAP global interpretation: (a) SHAP feature importance plot, (b) SHAP summary plot.

Furthermore, Fig. 19b shows the summary plot of the SHAP analysis, which depicts the impact of each input attribute on the flexural strength (Mu). The SHAP summary plot illustrates the correlation between the input parameters utilized in the study and their respective importance, with the y-axis representing the variables in order of significance. The x-axis of the graph represents the SHAP values, which show the influence of each variable. The colour of the dots on the graph corresponds to the magnitude of the SHAP values, ranging from small (blue) to large (red). Each dot represents a sample from the database. The horizontal x-axis illustrates the range of predictions based on the SHAP values for each parameter, showing the varying impact of input attributes from blue to red. The width of the beam positively influences the flexural strength of the beam, indicating that increasing the width of the beam will result in increased Mu. For instance, Amin et al. [26] reported that raising the width from 130 mm to 381 mm caused a significant increase of approximately 6 kN m in the bending capacity.

Similarly, the same trend can be noted in the values of the effective depth of the beam (ho) such that flexural capacity increases with the ho. The concepts of empirical equations and mechanics indicate a comparable relationship between the change in beam depth and variations in flexural capacity. It can also be noticed that the increased reinforcement ratio of tensile longitudinal bars (ρst) also favourably affects the Mu of the FRP-strengthened RC beam. Furthermore, the input attributes associated with the properties of FRP make a lesser contribution, which is understandable considering that the capacity supplied by FRP is minor when compared to the experimental bearing capacity of the RC beam.

6. Limitations of the study and recommendation for future work

The present work utilized the GEP and MEP models to predict the flexural capacity of FRP-strengthened RC beam in the range of 5.79–160.2 kN m range. However, it is highly recommended to utilize various metaheuristic optimization techniques such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO), and the Human Felicity Algorithm (HFA), as these methods have the potential to yield more accurate results for predicting the flexural capacity of FRP-strengthened RC beam. Furthermore, the SHAP global interpretation is used in the current study. However, the local interpretability of the ML model based on Partial Dependence Plots (PDP) and SHAP techniques can be used for future models. Furthermore, the current study utilized the database, containing only 200 data points, which is very limited. Therefore, an enhanced database is essential to bolster the empirical foundation of the models, ensuring a more comprehensive representation of real-world conditions and scenarios. A diverse and enriched dataset will improve the reliability and applicability of the predictive models for flexural capacity in FRP-strengthened RC beams, thereby enhancing their practical utility in engineering applications.

7. Conclusion

This study proposes model-based ML methods to forecast the flexural capacity of FRP-strengthened RC beams. A database consisting of 200 sets of experimental data was compiled from experimental studies for training and validating models. Using the collected database, prediction models for flexural capacity were developed using GEP and MEP algorithms empirical estimation models. The models' performance and accuracy were evaluated using a range of statistical indicators. To explain the models, SHAP was utilized to analyze the contribution of each feature and direction toward the prediction outcome. The findings of this work can be briefly provided as follows.

-

1.

In general, the flexural capacity prediction models using the ML approaches demonstrated excellent accuracy. The models achieved an R score above 0.96 in both the validation and training phases. Among both models, GEP showed superior predictions, with R, RMSE, and MAE scores of 0.981, 7.133, and 5.39, respectively, on the validation set. The majority of the predicted records in the GEP model aligned well with the experimental records. The models performed well on both sets (validation, training), with RMSE and MAE values at lower levels. This indicates that the models provided strong generalization and high accuracy capabilities.

-

2.

The accuracy of ML-based prediction models, particularly GEP, provided superior accuracy than empirical models. In contrast to the best-performing empirical models, the GEP-based model exhibited significant improvements. In the validation phase, the GEP-based model achieved a 5 % increase in R, a 41 % decrease in RMSE, and a 39 % decrease in MAE compared to the ACI 440.2R-08. These findings support that ML-based prediction models could be viable alternatives to empirical models to estimate the output accurately.

-

3.

The SHAP analysis reveals that beam depth (b), the effective depth of section (ho), and the reinforcement ratio of tensile longitudinal bars (ρst) have the most substantial positive impact on the predicted output, while the parameters associated with the properties of FRP exhibited comparatively less contribution.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Majid Khan: Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis. Adil Khan: Writing - original draft. Asad Ullah Khan: Writing - original draft, Visualization, Validation. Muhammad Shakeel: Supervision, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. Khalid Khan: Writing - review & editing, Writing - original draft, Supervision, Software, Conceptualization. Hisham Alabduljabbar: Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Taoufik Najeh: Resources, Funding acquisition. Yaser Gamil: Writing - original draft, Software, Project administration.

Declaration of Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Majid Khan, Email: 18pwciv4988@uetpeshawar.edu.pk.

Adil Khan, Email: a.khan348@bradford.ac.uk.

Asad Ullah Khan, Email: 18pwciv5033@uetpeshawar.edu.pk.

Muhammad Shakeel, Email: 18pwciv5186@uetpeshawar.edu.pk.

Khalid Khan, Email: khalidbfw770@gmail.com.

Hisham Alabduljabbar, Email: h.alabduljabbar@psau.edu.sa.

Taoufik Najeh, Email: taoufik.najeh@ltu.se.

Yaser Gamil, Email: yaser.g@monash.edu.

References

- 1.Chen S.-Z., Wu G., Xing T., Feng D.-C. Prestressing force monitoring method for a box girder through distributed long-gauge FBG sensors. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018;27 doi: 10.1088/1361-665X/aa9bbe. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S.-Z., Feng D.-C., Han W.-S. Comparative study of damage detection methods based on long-gauge FBG for Highway bridges. Sensors. 2020;20:3623. doi: 10.3390/s20133623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai J.-G., Gao W.-Y., Teng J.G. Finite element modeling of Insulated FRP-strengthened RC beams exposed to fire. J. Compos. Construct. 2015;19 doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baluch M.H., Khan A.R., Al-Gadhib A.H., Barnes R.A., Mays G.C. Fatigue performance of concrete beams strengthened with CFRP plates. J. Compos. Construct. 2000;4 doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0268(2000)4:4(215). 215–215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siddika A., Al Mamun M.A., Alyousef R., Amran Y.H.M. Strengthening of reinforced concrete beams by using fiber-reinforced polymer composites: a review. J. Build. Eng. 2019;25 doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2019.100798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollaway L.C. A review of the present and future utilisation of FRP composites in the civil infrastructure with reference to their important in-service properties. Construct. Build. Mater. 2010;24:2419–2445. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.04.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sena-Cruz J.M., Barros J.A.O., Coelho M.R.F., Silva L.F.F.T. Efficiency of different techniques in flexural strengthening of RC beams under monotonic and fatigue loading. Construct. Build. Mater. 2012;29:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.10.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Saadi N.T.K., Mohammed A., Al-Mahaidi R., Sanjayan J. A state-of-the-art review: near-surface mounted FRP composites for reinforced concrete structures. Construct. Build. Mater. 2019;209:748–769. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S.S., Yu T., Chen G.M. Reinforced concrete beams strengthened in flexure with near-surface mounted (NSM) CFRP strips: current status and research needs. Composites, Part B. 2017;131:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.07.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Y., Wang X., Sui L., Xing F., Wu Y., Chen C. Flexural performance of FRP-plated RC beams using H-type end anchorage. Compos. Struct. 2018;206:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choobbor S.S., Hawileh R.A., Abu-Obeidah A., Abdalla J.A. Performance of hybrid carbon and basalt FRP sheets in strengthening concrete beams in flexure. Compos. Struct. 2019;227 doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.111337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Gamal S.E., Al-Nuaimi A., Al-Saidy A., Al-Lawati A. Efficiency of near surface mounted technique using fiber reinforced polymers for the flexural strengthening of RC beams. Construct. Build. Mater. 2016;118:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.04.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu G., Dong Z.-Q., Wu Z.-S., Zhang L.-W. Performance and parametric analysis of flexural strengthening for RC beams with NSM-CFRP bars. J. Compos. Construct. 2014;18 doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naser M.Z. Machine learning assessment of fiber-reinforced polymer-strengthened and reinforced concrete members. ACI Struct. J. 2020;117:237–251. doi: 10.14359/51728073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.J.C.H. Dewey W.Y., Hodges H. Anurag Rajagopal, STRESS AND STRAIN RECOVERY FOR THE IN-PLANE DEFORMATION OF AN ISOTROPIC TAPERED STRIP-BEAM. J. Mech. Mater. Struct. 2010;5 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Awtar S., Slocum A.H., Sevincer E. Characteristics of beam-based flexure modules. J. Mech. Des. 2007;129:625–639. doi: 10.1115/1.2717231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umair Saleem M., Khurram N., Nasir Amin M., Khan K. Finite element simulation of RC beams under flexure strengthened with different layouts of externally bonded fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) sheets. Rev. La Construcción. 2019;17:383–400. doi: 10.7764/RDLC.17.2.383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawileh R.A., Musto H.A., Abdalla J.A., Naser M.Z. Finite element modeling of reinforced concrete beams externally strengthened in flexure with side-bonded FRP laminates. Composites, Part B. 2019;173 doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.106952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alabdullh A.A., Biswas R., Gudainiyan J., Khan K., Bujbarah A.H., Alabdulwahab Q.A., Amin M.N., Iqbal M. Hybrid ensemble model for predicting the strength of FRP laminates bonded to the concrete. Polymers. 2022;14:3505. doi: 10.3390/polym14173505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mangalathu S., Hwang S.-H., Choi E., Jeon J.-S. Rapid seismic damage evaluation of bridge portfolios using machine learning techniques. Eng. Struct. 2019;201 doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.109785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azadi Kakavand M.R., Sezen H., Taciroglu E. Data-driven models for predicting the shear strength of rectangular and circular reinforced concrete columns. J. Struct. Eng. 2021;147 doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0002875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mangalathu S., Jeon J.-S. Classification of failure mode and prediction of shear strength for reinforced concrete beam-column joints using machine learning techniques. Eng. Struct. 2018;160:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2018.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perera R., Barchín M., Arteaga A., De Diego A. Prediction of the ultimate strength of reinforced concrete beams FRP-strengthened in shear using neural networks. Composites, Part B. 2010;41:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2010.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mashrei M.A., Seracino R., Rahman M.S. Application of artificial neural networks to predict the bond strength of FRP-to-concrete joints. Construct. Build. Mater. 2013;40:812–821. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.11.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abuodeh O.R., Abdalla J.A., Hawileh R.A. Prediction of shear strength and behavior of RC beams strengthened with externally bonded FRP sheets using machine learning techniques. Compos. Struct. 2020;234 doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.111698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amin M.N., Iqbal M., Khan K., Qadir M.G., Shalabi F.I., Jamal A. Ensemble tree-based approach towards flexural strength prediction of FRP reinforced concrete beams. Polymers. 2022;14:1303. doi: 10.3390/polym14071303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L., Wang Z., Khan A.A., Khan M., Javed M.F., Alaskar A., Eldin S.M. Development of predictive models for sustainable concrete via genetic programming-based algorithms. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023;24:6391–6410. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.04.180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alabduljabbar H., Khan M., Awan H.H., Eldin S.M., Alyousef R., Mohamed A.M. Predicting ultra-high-performance concrete compressive strength using gene expression programming method. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023;18 doi: 10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alyousef jssRayed, Nassar R.-U.-D., Khan M., Arif K., Fawad M., Hassan A.M., Ghamry N.A. Forecasting the Strength Characteristics of Concrete incorporating Waste Foundry Sand using advance machine algorithms including deep learning. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wakjira T.G., Al-Hamrani A., Ebead U., Alnahhal W. Shear capacity prediction of FRP-RC beams using single and ensenble ExPlainable Machine learning models. Compos. Struct. 2022;287 doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan M., Javed M.F. Towards sustainable construction: machine learning based predictive models for strength and durability characteristics of blended cement concrete. Mater. Today Commun. 2023;37 doi: 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alyousef R., Rehman M.F., Khan M., Fawad M., Khan A.U., Hassan A.M., Ghamry N.A. Machine learning-driven predictive models for compressive strength of steel fiber reinforced concrete subjected to high temperatures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alyousef R., Rehman M.F., Khan M., Fawad M., Khan A.U., Hassan A.M., Ghamry N.A. Machine learning-driven predictive models for compressive strength of steel fiber reinforced concrete subjected to high temperatures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023;19 doi: 10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H.-L., Yin Z.-Y. High performance prediction of soil compaction parameters using multi expression programming. Eng. Geol. 2020;276 doi: 10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koza J.R., Koza J.R. MIT press; Cambridge, MA: 1992. Genetic Programming: on the Programming of Computers by Means of Natural Selection. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferreira C. Soft Computing and Industry. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2002. Gene expression programming in problem solving; pp. 635–653. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao W. A comprehensive review on identification of the geomaterial constitutive model using the computational intelligence method. Adv. Eng. Inf. 2018;38:420–440. doi: 10.1016/j.aei.2018.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iqbal M., Zhang D., Jalal F.E., Faisal Javed M. Computational AI prediction models for residual tensile strength of GFRP bars aged in the alkaline concrete environment. Ocean Eng. 2021;232 doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2021.109134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iqbal M.F., Liu Q., Azim I., Zhu X., Yang J., Javed M.F., Rauf M. Prediction of mechanical properties of green concrete incorporating waste foundry sand based on gene expression programming. J. Hazard Mater. 2020;384 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li W.X., Zhou C. Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference. Citeseer; Washington, DC, USA: 2005. Nelson PC Prefx gene expression programming; pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garg R., Kumari R., Tiwari S., Goyal S. Genomic survey, gene expression analysis and structural modeling suggest diverse roles of DNA methyltransferases in legumes. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang M., Wan W. A new empirical formula for evaluating uniaxial compressive strength using the Schmidt hammer test. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2019;123 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrmms.2019.104094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng Z.-L., Zhou W.-H., Garg A. Genetic programming model for estimating soil suction in shallow soil layers in the vicinity of a tree. Eng. Geol. 2020;268 doi: 10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jalal F.E., Xu Y., Iqbal M., Jamhiri B., Javed M.F. Predicting the compaction characteristics of expansive soils using two genetic programming-based algorithms. Transp. Geotech. 2021;30 doi: 10.1016/j.trgeo.2021.100608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vyas S.S.T.R., Goel P. Handbook of Genetic Programming Applications. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2015. Genetic programming applications in chemical sciences and engineering; pp. 99–140. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jahed Armaghani D., Faradonbeh R.S., Momeni E., Fahimifar A., Tahir M.M. Performance prediction of tunnel boring machine through developing a gene expression programming equation. Eng. Comput. 2018;34:129–141. doi: 10.1007/s00366-017-0526-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mazari M., Rodriguez D.D. Prediction of pavement roughness using a hybrid gene expression programming-neural network technique. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (English Ed. 2016;3:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jtte.2016.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nazar S., Yang J., Faisal Javed M., Khan K., Li L., Liu Q. An evolutionary machine learning-based model to estimate the rheological parameters of fresh concrete. Structures. 2023;48:1670–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.istruc.2023.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iqbal M.F., Javed M.F., Rauf M., Azim I., Ashraf M., Yang J., Liu Q. Sustainable utilization of foundry waste: forecasting mechanical properties of foundry sand based concrete using multi-expression programming. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;780 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oltean C.G.M. A comparison of several linear genetic programming techniques. Complex Syst. 2003;14(4):285–314. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fallahpour A., Olugu E.U., Musa S.N. A hybrid model for supplier selection: integration of AHP and multi expression programming (MEP), Neural Comput. Appl. 2017;28:499–504. doi: 10.1007/s00521-015-2078-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen C., Yang Y., Zhou Y., Xue C., Chen X., Wu H., Sui L., Li X. Comparative analysis of natural fiber reinforced polymer and carbon fiber reinforced polymer in strengthening of reinforced concrete beams. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;263 doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nader Tehrani B., Mostofinejad D., Hosseini S.M. Experimental and analytical study on flexural strengthening of RC beams via prestressed EBROG CFRP plates. Eng. Struct. 2019;197 doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.109395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.El-Zeadani M., Saifulnaz M.R.R., Mugahed Amran Y.H., Hejazi F., Jaafar M.S., Alyousef R., Alabduljabbar H. Flexural strength of FRP plated RC beams using a partial-interaction displacement-based approach. Structures. 2019;22:405–420. doi: 10.1016/j.istruc.2019.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maalej M., Leong K.S. Effect of beam size and FRP thickness on interfacial shear stress concentration and failure mode of FRP-strengthened beams. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005;65:1148–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.compscitech.2004.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen C., Wang X., Sui L., Xing F., Chen X., Zhou Y. Influence of FRP thickness and confining effect on flexural performance of HB-strengthened RC beams. Composites, Part B. 2019;161:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.10.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sabzi J., Esfahani M.R., Ozbakkaloglu T., Farahi B. Effect of concrete strength and longitudinal reinforcement arrangement on the performance of reinforced concrete beams strengthened using EBR and EBROG methods. Eng. Struct. 2020;205 doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.110072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen C., Yang Y., Yu J., Yu J., Tan H., Sui L., Zhou Y. Eco-friendly and mechanically reliable alternative to synthetic FRP in externally bonded strengthening of RC beams: natural FRP. Compos. Struct. 2020;241 doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sabzi J., Esfahani M.R. Effects of tensile steel bars arrangement on concrete cover separation of RC beams strengthened by CFRP sheets. Construct. Build. Mater. 2018;162:470–479. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moshiri N., Czaderski C., Mostofinejad D., Hosseini A., Sanginabadi K., Breveglieri M., Motavalli M. Flexural strengthening of RC slabs with nonprestressed and prestressed CFRP strips using EBROG method. Composites, Part B. 2020;201 doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eslami A., Shayegh H.R., Moghavem A., Ronagh H.R. Experimental and analytical investigations of a novel end anchorage for CFRP flexural retrofits. Composites, Part B. 2019;176 doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Skuturna T., Valivonis J. Experimental study on the effect of anchorage systems on RC beams strengthened using FRP. Composites, Part B. 2016;91:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao T D.Z., Xie J. Experimental study on flexural strength of RC beams strengthened with continuous carbon fiber sheet. Building Structure. 2000;30(7):11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hasnat A., Islam M.M., Amin A.F.M.S. Enhancing the debonding strain limit for CFRP-strengthened RC beams using U-clamps: identification of design parameters. J. Compos. Construct. 2016;20 doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buyle-Bodin F D.E. Use of carbon fibre textile to control premature failure of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with bonded CFRP plates. J. Ind. Text. 2016:145–157. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khalifa A.M. Flexural performance of RC beams strengthened with near surface mounted CFRP strips. Alexandria Eng. J. 2016;55:1497–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2016.01.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mostofinejad D., Hosseini S.M., Nader Tehrani B., Eftekhar M.R., Dyari M. Innovative warp and woof strap (WWS) method to anchor the FRP sheets in strengthened concrete beams. Construct. Build. Mater. 2019;218:351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.05.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Esfahani M.R., Kianoush M.R., Tajari A.R. Flexural behaviour of reinforced concrete beams strengthened by CFRP sheets. Eng. Struct. 2007;29:2428–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2006.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Woo S.-K., Nam J.-W., Kim J.-H.J., Han S.-H., Byun K.J. Suggestion of flexural capacity evaluation and prediction of prestressed CFRP strengthened design. Eng. Struct. 2008;30:3751–3763. doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2008.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chiew Sp Y.Y., Sun Q. Flexural strength of RC beams with GFRP laminates. J Compos Constr. 2007;11(5):497–506. [Google Scholar]

- 71.You Y.-C., Choi K.-S., Kim J. An experimental investigation on flexural behavior of RC beams strengthened with prestressed CFRP strips using a durable anchorage system. Composites, Part B. 2012;43:3026–3036. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang M.Y.S.Y. Experimental study of flexural behavior of high-strength RC beams strengthened with CFRP sheets. Build. Sci. 2006;22(5):70. 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zaki M.A., Rasheed H.A. Impact of efficiency and practicality of CFRP anchor installation techniques on the performance of RC beams strengthened with CFRP sheets. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2019;46:796–809. doi: 10.1139/cjce-2018-0560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim H.S., Shin Y.S. Flexural behavior of reinforced concrete (RC) beams retrofitted with hybrid fiber reinforced polymers (FRPs) under sustaining loads. Compos. Struct. 2011;93:802–811. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2010.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Al-Tamimi Ak R.H., Hawileh R., Abdalla J. Effects of ratio of CFRP plate length to shear span and end anchorage on flexural behavior of SCC RC beams. J Compos Constr. 2011;15:908–919. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang W.W. Dalian University of Technology.; Dalian: 2003. Study on Flexural Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Beams Strengthened with Fiber Reinforced Plastics. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bin Y.F. Nanjing University of Science and Technology.; Nanjing: 2007. Tudy on Flexural Performance of RC Beam Reinforced with Near Surface Mounted CFRP. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Daghash S.M., Ozbulut O.E. Flexural performance evaluation of NSM basalt FRP-strengthened concrete beams using digital image correlation system. Compos. Struct. 2017;176:748–756. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sharaky I.A., Torres L., Comas J., Barris C. Flexural response of reinforced concrete (RC) beams strengthened with near surface mounted (NSM) fibre reinforced polymer (FRP) bars. Compos. Struct. 2014;109:8–22. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2013.10.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tang W.C., Balendran R.V., Nadeem A., Leung H.Y. Flexural strengthening of reinforced lightweight polystyrene aggregate concrete beams with near-surface mounted GFRP bars. Build. Environ. 2006;41:1381–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2005.05.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lorenzis A.L.T.L.D., Micelli F. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Composites in Infrastructure (ICCI) 2002. Passive and active near-surface mounted FRP rods for flexural strengthening of RC beams. [Google Scholar]

- 82.El-Gamal A-N A.-S.A.-L. Efficiency of near surface mounted technique using fiber reinforced polymers for the flexural strengthening of RC beams. Constr Build Mater. 2016;118:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dias S.J.E., Barros J.A.O., Janwaen W. Behavior of RC beams flexurally strengthened with NSM CFRP laminates. Compos. Struct. 2018;201:363–376. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.05.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Teng Jg L.L., Lorenzis L.D., Bo W., Rong L., Wong T.N. Debonding failures of RC beams strengthened with near surface mounted CFRP strips. J Compos Constr. 2006;10(2):92–105. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Haddad R.H., Almomani O.A. Recovering flexural performance of thermally damaged concrete beams using NSM CFRP strips. Construct. Build. Mater. 2017;154:632–643. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.07.211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hui S.K., Meyvis T., Assael H. Analyzing moment-to-moment data using a bayesian functional linear model: application to TV show pilot testing. Mark. Sci. 2014;33:222–240. doi: 10.1287/mksc.2013.0835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang S.S., Ke Y., Smith S.T., Zhu H.P., Wang Z.L. Effect of FRP U-jackets on the behaviour of RC beams strengthened in flexure with NSM CFRP strips. Compos. Struct. 2021;256 doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.113095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Al-Saadi N.T.K., Mohammed A., Al-Mahaidi R. Performance of RC beams rehabilitated with NSM CFRP strips using innovative high-strength self-compacting cementitious adhesive (IHSSC-CA) made with graphene oxide. Compos. Struct. 2017;160:392–407. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.10.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hong S., Park S.-K. Prestressing effects on the performance of concrete beams with near-surface-mounted carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer bars. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2016;52:305–316. doi: 10.1007/s11029-016-9583-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Song S.-H. Prosodic analysis of Korean Chinese on-glide diphthong and educational Korean notation, Chinese lang. Educ. Res. 2014;20:57. doi: 10.24285/CLER.2014.12.20.57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xing G., Chang Z., Ozbulut O.E. Behavior and failure modes of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with NSM GFRP or aluminum alloy bars. Struct. Concr. 2018;19:1023–1035. doi: 10.1002/suco.201700099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li H.M. Hebei University of Science and Technology; Shijiazhuang: 2014. Experimental Study on Flexural Behavior of RC Beams Strengthened with Near-Surface Mounted FRP under Different Damages. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Barros J.A.O., Dias S.J.E., Lima J.L.T. Efficacy of CFRP-based techniques for the flexural and shear strengthening of concrete beams. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007;29:203–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jia B., Xue J., Mo J., Zhang C.T. Experimental study on flexural behavior of damaged reinforced concrete beams strengthened with CFRP. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014;507:306–310. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.507.306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tang Y W.G., Lu H.Y., Zou Y.Q., Zeng Y.H. Experimental study on the flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams strengthened by composite method. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2020;50(5):822–830. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Li Z.J. Changchun, Jilin Architecture and Civil Engineering Institute.; 2012. The Study of the NSM FRP Bars Strengthening of the RC Beams. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Al-Mahmoud F., Castel A., François R., Tourneur C. Strengthening of RC members with near-surface mounted CFRP rods. Compos. Struct. 2009;91:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2009.04.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rezazadeh M., Costa I., Barros J. Influence of prestress level on NSM CFRP laminates for the flexural strengthening of RC beams. Compos. Struct. 2014;116:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2014.05.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sharaky I.A., Baena M., Barris C., Sallam H.E.M., Torres L. Effect of axial stiffness of NSM FRP reinforcement and concrete cover confinement on flexural behaviour of strengthened RC beams: experimental and numerical study. Eng. Struct. 2018;173:987–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2018.07.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jumaat M.O.M.Z., Hosen M.A., Darain K.M.U. 2015. Innovative End Anchorage for Preventing Concrete Cover Separation of NSM Steel and CFRP Bars Strengthened RC Beams. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Barros J.A.O., Fortes A.S. Flexural strengthening of concrete beams with CFRP laminates bonded into slits. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005;27:471–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2004.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sui Ll F.Y., Liu T.J., Xing F. Experimental study on flexural performances of concrete beams strengthened with near-surface mounted (NSM) FRP reinforcement. Advanced Materials Research :3634–9. 2011:163–167. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Al-Mahmoud F., Castel A., François R., Tourneur C. RC beams strengthened with NSM CFRP rods and modeling of peeling-off failure. Compos. Struct. 2010;92:1920–1930. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2010.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cao Q., Zhou J., Wu Z., Ma Z.J. Flexural behavior of prestressed CFRP reinforced concrete beams by two different tensioning methods. Eng. Struct. 2019;189:411–422. doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.03.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sharaky I.A., Torres L., Sallam H.E.M. Experimental and analytical investigation into the flexural performance of RC beams with partially and fully bonded NSM FRP bars/strips. Compos. Struct. 2015;122:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2014.11.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Reda R.M., Sharaky I.A., Ghanem M., Seleem M.H., Sallam H.E.M. Flexural behavior of RC beams strengthened by NSM GFRP Bars having different end conditions. Compos. Struct. 2016;147:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shabana Is A.E., Sharaky I.A., Khalil A., Hadad H.S. Flexural response analysis of passive and active near-surface-mounted joints: experimental and finite element analysis. Mater. Struct. 2018;51:107. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rankovic S M.M., Folic R. Flexural behaviour of RC beams strengthened with NSM CFRP and GFRP bars – experimental and numerical study. Romanian Journal of Materials. 2013;43:377–390. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nordin H T.B. Concrete beams strengthened with prestressed near surface mounted CFRP. J Compos Constr. 2006;10(1):60–68. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Täljsten B., Carolin A., Nordin H. Concrete structures strengthened with near surface mounted reinforcement of CFRP. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2003;6:201–213. doi: 10.1260/136943303322419223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Almusallam T.H., Elsanadedy H.M., Al-Salloum Y.A., Alsayed S.H. Experimental and numerical investigation for the flexural strengthening of RC beams using near-surface mounted steel or GFRP bars. Construct. Build. Mater. 2013;40:145–161. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.09.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ceroni F. Experimental performances of RC beams strengthened with FRP materials. Construct. Build. Mater. 2010;24:1547–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jung Wt Y.Y., Park Y.H., Park J.S., Kang J.Y. vol. 230. American Concrete Institute Special Publication; 2005. pp. 795–806. (Experimental Investigation on Flexural Behavior of RC Beams Strengthened by NSM CFRP Reinforcements). [Google Scholar]

- 114.Abdalla J.A., Mohammed A., Hawileh R.A. Flexural strengthening of reinforced concrete beams with externally bonded hybrid systems. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2020;28:2312–2319. doi: 10.1016/j.prostr.2020.11.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]