Abstract

Research Objective:

Per federal law, “988” became the new three-digit dialing code for the National Suicide & Crisis Lifeline on July 16, 2022 (previously reached by dialing “1-800-283-TALK”). This study aimed to produce state-level estimates of: 1) annual increases in 988 Lifeline call volume following 988 implementation, 2) the cost of these increases, and 3) the extent to which state and federal funding earmarked for increases in 988 Lifeline call volume are sufficient to meet call demand.

Study Design:

A 50 state pre-post policy implementation design was used. State-level Lifeline call volume data were obtained. For each state, we calculated the absolute difference in number of Lifeline calls in the four-month periods between August-November 2021 (pre-988 implementation) and August-November 2022 (post-988 implementation), and also expressed this difference as percent change and rate per 100,000 population. The difference call volume was multiplied by a published estimate of the cost of a single 988 Lifeline call ($82), and then by multiplied by three to produce annual, 12-month state-level cost increase estimates. These figures were then divided by each state’s population size to generate cost estimates per state resident. State-level information on the amount of state (FY 2023) and federal SAMHSA (FY 2022) funding earmarked for 988 Lifeline centers in response to 988 implementation were obtained from legal databases and government websites and expressed as dollars per state resident. State-level differences between per state resident estimates of increased cost and funding were calculated to assess the extent to which state and federal funding earmarked for increases in 988 Lifeline call volume were sufficient to meet call demand.

Findings:

988 Lifeline call volume increased in all states post-988 implementation (within-state mean percent change= +32.8%, SD= +20.5%). The total estimated cost needed annually to accommodate increases in 988 Lifeline call volume nationally was approximately $46 million. The within-state mean estimate of additional cost per state resident was +$0.16 (SD= +$0.11). The additional annual cost per state resident exceeded $0.40 in three states, was between $0.40-$0.30 in three states, and between $0.30- $0.20 in seven states. Twenty-two states earmarked FY 2023 appropriations for 988 Lifeline centers in response to 988 (within-state mean per state resident= $1.51, SD= $1.52) and 49 states received SAMHSA 988 capacity building grants (within-state mean per state resident= $0.36, SD= $0.39). State funding increases exceeded the estimated cost increases in about half of states.

Conclusions:

The Lifeline’s transition to 988 increased 988 Lifeline call volume in all states, but the magnitude of the increase and associated cost was heterogenous across states. State funding earmarked for increases in 988 Lifeline center costs is sufficient in about half of states. Sustained federal funding, and/or increases in state funding, earmarked for 988 Lifeline centers is likely important to ensuring that 988 Lifeline centers have the capacity to meet call demand in the post-988 implementation environment.

BACKGROUND

Multiple indicators signal that the United States is in the midst of a mental health crisis. An estimated 44,834 people died by suicide in the United States in 2020.(1) In the preceding two decades, the suicide rate had been increasing precipitously—with the rate increasing by 35% between 2000 and 2018.(2, 3) Suicide death rates are a “tip of the iceberg” indicator for serious mental distress and suicidality. The proportion of U.S. adults experiencing “extreme psychological distress” (i.e., reporting that their mental health was “not good” for 30 of the past 30 days) increased from 3.6% in 1993 to 6.4% in 2019.(4) In 2020 an estimated 4.9% of U.S. adults had “serious thoughts of suicide” in the past year, 1.3% made a suicide plan, and 0.5% attempted suicide.(5) Among those who had serious thoughts of suicide, 21.1% indicated that it was because of the COVID-19 pandemic; and data from callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline indicated that the pandemic contributed to suicidality.(6) Emergency departments visits for mental health crises and suicidality increased substantially during the pandemic.(7, 8)

Within and because of this epidemiological context, the National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020 was signed into law on October 17, 2020 (Pub. Law 116-172). The law required the Federal Communications Commission to designate “988” as the new dialing code for the what was formerly known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline—now known as the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (hereafter referred to as the “988 Lifeline”). Changing the name of the Lifeline from one that was narrowly focused on suicide to one that is focused on mental health crises more broadly is likely to expand the population of people who contact the Lifeline. While the prior name suggested that the Lifeline was only for people who are suicidal, the new name implies that it is for people experiencing a much wider range of mental health challenges.

When a person calls 988 they hear a greeting and are then instructed to press “1” if they are a Veteran (and are then connected to the Veteran’s Crisis Line, which has demonstrated signals of effectiveness (9, 10)) or “2” if they would like to be connected to the Spanish language Lifeline. If neither option is selected, the caller is routed to a local 988 Lifeline center based on the area code of the caller. If the wait time to speak with someone at that center is excessive, they are then routed to a regional or national backup 988 center. The caller is then connected to a trained crisis councilor who provides active listening, conducts risk assessment, and connects the caller to resources based on needs. 988 Lifeline centers are accredited by a range of source, including but not limited to the American Association of Suicidology, the International Council for Helplines, and state and county licensure bodies. Crisis counselors contact emergency services for approximately 2% of calls, about half of which occur with the explicit consent of the caller (statistics are based on data as provided to Vibrant Emotional Health from 988 Lifeline network centers).

988 was rolled out nationally as the new dialing/text code on July 16, 2022. The original Lifeline had been in operation since 2005 (reached by dialing “1-800-283-TALK”), received about 2.4 million calls in 2020, and call volume increased by an average of 14% annually between 2007 and 2020.(11, 12) The National Suicide Hotline Designation Act, however, sought to make easier for people experiencing suicidality and mental health crises to seek help. As the law states (Sec. 2): “To prevent future suicides, it is critical to transition the cumbersome, existing 10-digit National Suicide Hotline to a universal, easy-to-remember, 3-digit phone number.”

Research indicates that the pre-988 Lifeline decreased suicidality, hopelessness, psychological distress, and suicide death.(13-22) “Moderate” growth estimates, produced by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), indicate that the Lifeline’s transition to 988 and expansion of scope could increase call volume by three million calls in first full year following implementation and by eight million calls five years following implementation.(12) As such, 988 has been regarded as monumental policy change with potential to significantly benefit population mental health.(23-26) However, the impact of 988 likely hinges upon state financing for its implementation.

Despite the explicit intent of the federal 988 law to increase Lifeline call volume, it does not provide funding to cover the costs of increased call demand.(12) While SAMHSA has, and continues to, fund the infrastructure supporting the Lifeline, responsibility for funding the over 200 local 988 Lifeline centers (which handle calls and/or texts and/or chats) largely falls to state and local governments.(27) The 988 law does, however, explicitly authorize and in effect encourages states to pass user fee legislation to cover costs incurred by 988 Lifeline centers and finance the costs of crisis services (e.g., mobile crisis response teams, 24-hour crisis stabilization centers) that are activated, as needed, after a person contacts the 988 Lifeline. Fees (e.g., 30¢ per month per every cell plan holder in the state, regardless of 988 usage) such as these are how 9-1-1 call centers are financed in all states and many local jurisdictions. To date, however, only five states have passed 988 user fee legislation (CA, CO, NV, VA, WA).(27, 28) Some states have appropriated funds for 988 implementation in their fiscal year (FY) 2022 and/or 2023 budgets, but many others have not.(27, 28) The federal government has made appropriations for 988 implementation through separate actions (e.g., The Safer Communities Act, $150 million;(29) SAMHSA 988 implementation and capacity building grants; $106 million for FY 2022;(30) SAMHSA Community Mental Health Block Grant 5% set aside for crisis services) but plans to sustainably finance 988 Lifeline centers in the post-988 environment remain uncertain in most states. A winter 2022 survey of mental health system leaders found that 74% of respondents did not feel that their agency had established a budget for the transition to, and sustainable financing of, 988.(31)

One reason why states have not taken legislative action on 988 financing may relate to uncertainty about the magnitude of increases in 988 Lifeline call volume and associated costs. Because there is little precedent for a change such as 988 in the United States, estimates of the magnitude of increases are based on empirically questionable assumptions. In 2021-2022, many states passed legislation requiring the study of the impact of 988 on demand for crisis services and associated costs.(28) Nationally, 988 Lifeline call volume increased by 45% in the two weeks following the launch of 988 in July 2022 (compared to the same time period in 2021).(32) However, little is known about whether the increase was sustained over time or how the magnitude increase varied across states—among which there is heterogeneity in 988 Lifeline metrics and crisis system capacity.(33-37) Empirical estimates of the costs associated with increases in call volume are also lacking.(38) More broadly, questions related to financing mental health crisis systems—which at a minimum included mobile crisis response teams and 24-hour crisis stabilization centers in addition to 988 Lifeline centers(23)—have been the focus of minimal investigation.(25, 27)

AIMS OF THE STUDY

The goals of this study are twofold. First, we estimate the initial impact of 988 implementation on 988 Lifeline call volume across states and produce annual estimates of the costs of meeting increased 988 Lifeline call volume demand within each state. Second, we characterize state financing legislation and/or earmarked budget appropriations aimed at increasing funding for 988 Lifeline centers in FY 2023 in response to 988 implementation and quantify increased spending for 988 Lifeline centers for FY 2023 across states. To our knowledge, this is the first empirical study of financing related to 988 Lifeline centers in the 988 implementation context.

METHODS

Data Analytic Procedures: Estimating State-Level Impacts of 988 Implementation on Lifeline Call Volume and Costs of Increased Call Demand

Publicly available state-level data on Lifeline call volume by month were obtained from the 988 Lifeline website—maintained by Vibrant Emotional Health, which administers the 988 Lifeline .(39) These call volume data represent demand for 988 Lifeline call services in states and include all calls received by 988 Lifeline centers in each state, regardless of whether calls were transferred to an out-of-state overflow 988 Lifeline center because of an excessive wait time within the state. We compared the number of calls made to 988 Lifeline centers in each state in the four full months between August and November 2022 (the most recent full months for which data were available at the time of analysis), beginning two weeks after 988 went live nationally, to the number of calls made to 988 Lifeline centers in each state in the same four months in 2021. Comparing the same months between years helps account for seasonal patterns in suicidality.(40, 41) For each state we calculated the absolute difference in number of calls between August-November 2022 (post-988 implementation) and August-November 2021 (pre-988 implementation) and also expressed this difference as percent change. We multiplied the number of additional calls by three to extrapolate an annual, 12-month estimate and expressed this as a per 100,000 population rate increase for each state using 2020 Decennial Census data. Maine was excluded from analyses because automated robocalls (i.e., from computers, not people) produced an inflated call volume figure for August 2022. Robocalls are identified and confirmed by Vibrant Emotional Health through a standardized process. We used SAMHSA’s estimate of the cost of a single 988 Lifeline center call ($82) to produce state-level estimates of additional 988 Lifeline center costs needed to meet call demand in the post-988 context.(12) The SAMHSA cost estimate includes 988 Lifeline center-specific call costs (e.g., staff, rent, training) but not costs associated with non-Lifeline crisis services (e.g., deployment of mobile crisis response teams, visit to crisis stabilization centers). For each state, we multiplied this $82 cost estimate by 12-month estimate of the additional number of calls to create a total estimates of additional costs per state. To facilitate comparisons in the magnitude of cost increase between states, we also divided this cost estimate by each state’s population size, using 2020 Decennial Census data, to generate a per capita cost estimate. Primary analyses were descriptive statistics for each measure, using states as the unit of analysis.

Data Analytic Procedures: Characterizing and Quantifying State Legislation that Increased Funding for 988 Lifeline Centers in Response to 988 Implementation

We drew from multiple sources that have tracked enacted state legislation and budget appropriations related to 988 implementation: the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ 988 Crisis Response State Legislation database,(42) the National Academy for State Health Policy’s State Legislation to Fund and Implement 988 database,(43) reports on state 988 legislation prepared by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors,(28, 44) and an analysis of FY 2023 state appropriations compiled by Vibrant Emotional Health. Information on the amount collected through state 988 user fees was obtained from the Federal Communication Commission’s 2022 “988 Fee Accountability Report.”(45) We compared findings across these data sources and consulted primary sources (e.g., enacted laws and budgets on state websites) in attempt to resolve discrepancies and confirm the accuracy of information.

Our primary variables were a dichotomous indicator whether each state enacted financing legislation and/or earmarked budget appropriations explicitly for 988 Lifeline centers in response to 988 implementation for FY 2023 and a continuous measure of this funding amount, gross as well as per capita within the state. Our secondary variable was a dichotomous indicator whether each state enacted financing legislation and/or earmarked budget appropriations broadly for mental health crisis services in response to 988 implementation, but not 988 Lifeline centers specifically for FY 2023. We did not collect information on the exact funding amount for this variable because the amount specifically for 988 Lifeline centers (the focus of the current study) was not stated and there was substantial inconsistency in what were considered “crisis services” across states—which inhibited comparisons between states.

Another secondary variable was a continuous measure, gross and per capita, of the amount that each state received in federal 988 capacity building grants from SAMHSA for FY 2022 (which can span multiple fiscal years).(30) As described in the FY 2022 funding opportunity announcement,(46) these grants focused on 988 Lifeline centers. We also characterized each state according to whether or not it had, at any point in time, passed legislation that: a) created a cellphone user fee to finance 988 implementation (a possible strategy for sustainable financing),(28) b) created a trust fund for 988 financing (also regarded as a promising strategy),(28) c) required a study of the impact of 988 on service demand and costs, and d) created a 988 advisory board.

We generated descriptive statistics (e.g., means, percentages) for these financing variables. For each state, we also calculated the difference between the estimated additional per capita cost of covering increase call demand for 988 Lifeline center services post-988 implementation and the amount of state and SAMHSA funding (together and separately) explicitly for 988 Lifeline centers in response to 988 implementation. This measure provides indication of the extent to which increases in funding are sufficient to meet increases in demand.

RESULTS

Initial State-Level Impacts of 988 Implementation on 988 Lifeline Call Volume and Costs of Increased Demand

Table 1 shows state-level changes in Lifeline volume between pre-post 988 implementation and estimates of the financial resources needed to accommodate these changes in 988 Lifeline centers. States are listed according to the amount of additional dollars needed per state resident to accommodate the change (most to least). 988 Lifeline call volume increased in all 49 states between August-November 2021 (pre-988 implementation) and August-November 2022 (post 988 implementation), ranging from an increase of 91.6% in Vermont to 0.5% in West Virginia. The mean within-state percent increase in call volume was 32.8% (SD= 20.5%) and the median was 28.1%. Call volume increased by more than 75% in two states, by 50% to 75% in eight states, and by 25% to 50% in 19 states. The mean within-state increase in call volume per 100,000 population was 199.9 (SD= 131.1).

Table 1:

Initial State-Level Impacts of 988 Implementation on 988 Lifeline Call Volume and Estimated Costs of Increased Demand, Calendar Years 2022-2023

| State | Calls Received, August- November 2021 (pre- 988) |

Calls Received, August- November 2022 (post- 988) |

Percent Change in Call Calls Received |

Estimate of Additional Calls Annually Post 988 |

Estimate of Additional Calls Annually Post 988, Per 100,000 State Population |

Additional $ Needed to Accommodate Estimated Change in Calls Received Annually |

Additional $ Needed to Accommodate Estimated Change in Calls Received Annually, Per Capita |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VT | 1,340 | 2,567 | 91.6% | 3,681 | 572.92 | $301,842 | $0.47 |

| WI | 13,745 | 23,967 | 74.4% | 30,666 | 520.44 | $2,514,612 | $0.43 |

| HI | 3,494 | 5,934 | 69.8% | 7,320 | 504.16 | $600,240 | $0.41 |

| NM | 5,889 | 8,958 | 52.1% | 9,207 | 434.79 | $754,974 | $0.36 |

| IL | 29,788 | 46,807 | 57.1% | 51,057 | 399.34 | $4,186,674 | $0.33 |

| WY | 910 | 1,659 | 82.3% | 2,247 | 389.25 | $184,254 | $0.32 |

| NH | 2,410 | 4,031 | 67.3% | 4,863 | 352.94 | $398,766 | $0.29 |

| NE | 4,097 | 6,317 | 54.2% | 6,660 | 339.54 | $546,120 | $0.28 |

| OK | 7,056 | 11,502 | 63.0% | 13,338 | 336.65 | $1,093,716 | $0.28 |

| NV | 6,883 | 9,661 | 40.4% | 8,334 | 267.62 | $683,388 | $0.22 |

| UT | 8,959 | 11,724 | 30.9% | 8,295 | 252.77 | $680,190 | $0.21 |

| WA | 17,412 | 23,785 | 36.6% | 19,119 | 247.69 | $1,567,758 | $0.20 |

| AZ | 13,993 | 19,803 | 41.5% | 17,430 | 242.83 | $1,429,260 | $0.20 |

| VA | 18,300 | 25,074 | 37.0% | 20,322 | 235.43 | $1,666,404 | $0.19 |

| NY | 47,952 | 63,431 | 32.3% | 46,437 | 230.40 | $3,807,834 | $0.19 |

| CT | 6,530 | 9,212 | 41.1% | 8,046 | 223.48 | $659,772 | $0.18 |

| GA | 18,866 | 26,805 | 42.1% | 23,817 | 222.05 | $1,952,994 | $0.18 |

| MO | 11,965 | 16,494 | 37.9% | 13,587 | 220.77 | $1,114,134 | $0.18 |

| SD | 1,287 | 1,935 | 50.3% | 1,944 | 219.14 | $159,408 | $0.18 |

| AK | 2,494 | 3,016 | 20.9% | 1,566 | 213.81 | $128,412 | $0.18 |

| MA | 16,222 | 21,196 | 30.7% | 14,922 | 212.50 | $1,223,604 | $0.17 |

| OR | 13,447 | 16,421 | 22.1% | 8,922 | 210.35 | $731,604 | $0.17 |

| SC | 9,842 | 13,236 | 34.5% | 10,182 | 198.45 | $834,924 | $0.16 |

| OH | 20,736 | 27,831 | 34.2% | 21,285 | 180.53 | $1,745,370 | $0.15 |

| MD | 12,627 | 16,074 | 27.3% | 10,341 | 167.53 | $847,962 | $0.14 |

| MT | 2,366 | 2,943 | 24.4% | 1,731 | 159.36 | $141,942 | $0.13 |

| MN | 11,387 | 14,293 | 25.5% | 8,718 | 152.76 | $714,876 | $0.13 |

| KS | 6,065 | 7,521 | 24.0% | 4,368 | 148.78 | $358,176 | $0.12 |

| TN | 11,327 | 14,741 | 30.1% | 10,242 | 148.00 | $839,844 | $0.12 |

| IA | 5,573 | 7,067 | 26.8% | 4,482 | 140.56 | $367,524 | $0.12 |

| NJ | 15,416 | 19,754 | 28.1% | 13,014 | 140.24 | $1,067,148 | $0.11 |

| RI | 1,443 | 1,930 | 33.7% | 1,461 | 133.28 | $119,802 | $0.11 |

| CA | 94,892 | 111,837 | 17.9% | 50,835 | 128.70 | $4,168,470 | $0.11 |

| MI | 21,474 | 25,609 | 19.3% | 12,405 | 123.22 | $1,017,210 | $0.10 |

| FL | 34,564 | 43,387 | 25.5% | 26,469 | 122.71 | $2,170,458 | $0.10 |

| PA | 19,737 | 24,396 | 23.6% | 13,977 | 107.60 | $1,146,114 | $0.09 |

| NC | 19,133 | 22,582 | 18.0% | 10,347 | 98.95 | $848,454 | $0.08 |

| KY | 8,083 | 9,566 | 18.3% | 4,449 | 98.78 | $364,818 | $0.08 |

| MS | 4,394 | 5,365 | 22.1% | 2,913 | 98.52 | $238,866 | $0.08 |

| ID | 4,237 | 4,840 | 14.2% | 1,809 | 97.90 | $148,338 | $0.08 |

| LA | 8,791 | 10,204 | 16.1% | 4,239 | 91.14 | $347,598 | $0.07 |

| CO | 17,492 | 19,106 | 9.2% | 4,842 | 83.71 | $397,044 | $0.07 |

| IN | 12,364 | 13,997 | 13.2% | 4,899 | 72.20 | $401,718 | $0.06 |

| AR | 5,144 | 5,793 | 12.6% | 1,947 | 64.64 | $159,654 | $0.05 |

| AL | 9,286 | 10,311 | 11.0% | 3,075 | 61.20 | $252,150 | $0.05 |

| ND | 1,470 | 1,609 | 9.5% | 417 | 53.53 | $34,194 | $0.04 |

| TX | 54,316 | 58,668 | 8.0% | 13,056 | 44.69 | $1,070,592 | $0.04 |

| DE | 1,542 | 1,628 | 5.6% | 258 | 26.01 | $21,156 | $0.02 |

| WV | 3,877 | 3,897 | 0.5% | 60 | 3.35 | $4,920 | $0.003 |

Note: ME excluded from analysis because of robocalls (i.e., not from real people) in August 2022.

Across all 49 states for which data were available, the total estimated cost needed annually to accommodate changes in 988 Lifeline call volume was $46,215,282 ($0.14 per capita). The mean within-state estimate of cost per state resident was $0.16 (SD= $0.11) and the median was $0.14. The additional annual cost per state resident exceeded $0.40 in three states, was between $0.30 and $0.40 in three states, and was between $0.20 and $0.30 in seven states.

State Legislation Increasing Funding for 988 Lifeline Centers in Response to 988 Implementation

As shown in Table 2, 22 states (44.0%) enacted legislation and/or earmarked budget appropriations explicitly for 988 Lifeline centers for FY 2023 in response to 988 implementation. Among these states, the mean funding amount per state resident was $1.51 (SD= $1.52), the median was $1.0, and the amount ranged from $6.23 in Virginia to in $0.12 in North Carolina. Among these states, the mean per capita amount was $4.71 in the two states that allocated revenue from 988 cellphone user fee legislation in FY 2023 and $1.19 in those without user fee legislation. Eight states (16.0%) enacted financing legislation and/or earmarked budget appropriations broadly for mental health crisis services in response to 988 implementation, but not 988 Lifeline centers specifically. Twenty states (40.0%) did not pass any financing legislation explicitly related to 988 for FY 2023. Twelve states (24.0%) had passed legislation creating a trust fund for 988-related costs, seven (14.0%) passed a law requiring study of the impact of 988 on service demand and costs, and eight (16%) created a 988 advisory board. Forty-nine states received SAMHSA 988 capacity building grants in FY 2022, with the mean amount of funding per state resident being $0.36 (SD= $0.39), the median $0.30, and the range spanning from $3.02 in Rhode Island to $0.20 in Maine and $0 in Alaska (which did not receive a grant).

Table 2:

Funding for 988 Lifeline Centers in Response to 988 Implementation, Fiscal Year 2023

| State | $ Earmarked for 988 Lifeline Centers |

$ Amount Earmarked for 988 Lifeline Centers, Gross |

$ Amount Earmarked for 988 Lifeline Centers, Per Capita |

$ Earmarked for Crisis Services in Response to 988, But not 988 Lifeline Centers Explicitly |

Has Passed 988 Cell Phone User Fee Legislation |

Has Created 988 Trust Fund |

Has Required Study of 988 Impact on Service Demand and Costs |

Has Created 988 Advisory Board |

$ in SAMHSA 988 Lifeline Center Capacity Grants, Gross |

$ in SAMHSA 988 Lifeline Center Capacity Grants, Per Capita |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA | Yes | $3,593,935 | $6.23 | n/a | Yes | Yes | No | No | $2,642,519 | $0.31 |

| WY | Yes | $2,100,000 | $3.64 | n/a | No | Yes | No | Yes | $250,000 | $0.43 |

| KS | Yes | $10,000,000 | $3.41 | n/a | No | Yes | No | Yes | $935,937 | $0.32 |

| WA | Yes | $24,609,000 | $3.19 | n/a | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | $2,674,720 | $0.35 |

| ID | Yes | $4,400,000 | $2.38 | n/a | No | No | No | No | $642,017 | $0.35 |

| CO** | Yes | $11,905,027 | $2.06 | n/a | Yes | Yes | No | No | $2,458,104 | $0.42 |

| NY | Yes | $35,000,000 | $1.74 | n/a | No | No | Yes | No | $7,279,976 | $0.36 |

| NJ | Yes | $16,000,000 | $1.72 | n/a | No | No | Yes | No | $2,521,695 | $0.27 |

| RI | Yes | $1,875,000 | $1.71 | n/a | No | No | No | No | $3,315,098 | $3.02 |

| OR | Yes | $5,000,000 | $1.18 | n/a | No | No | No | Yes | $2,114,860 | $0.50 |

| NM | Yes | $2,325,000 | $1.10 | n/a | No | No | No | No | $886,787 | $0.42 |

| SC | Yes | $5,500,000 | $1.07 | n/a | No | No | No | No | $1,390,817 | $0.27 |

| MD | Yes | $5,500,000 | $0.89 | n/a | No | Yes | No | No | $1,972,989 | $0.32 |

| MS | Yes | $2,000,000 | $0.68 | n/a | No | No | Yes | No | $693,226 | $0.23 |

| UT | Yes | $1,851,800 | $0.56 | n/a | No | Yes | No | Yes | $1,409,262 | $0.43 |

| IL | Yes | $5,000,000 | $0.39 | n/a | No | Yes | No | Yes | $4,496,838 | $0.35 |

| MI | Yes | $3,000,000 | $0.30 | n/a | No | No | No | No | $3,350,829 | $0.33 |

| MN | Yes | $1,300,000 | $0.23 | n/a | No | No | No | No | $1,845,532 | $0.32 |

| CA** | Yes | $8,000,000 | $0.20 | n/a | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | $14,488,135 | $0.37 |

| GA | Yes | $2,000,000 | $0.19 | n/a | No | No | No | No | $2,927,923 | $0.27 |

| LA | Yes | $676,467 | $0.15 | n/a | No | No | No | No | $1,352,934 | $0.29 |

| NC | Yes | $1,300,000 | $0.12 | n/a | No | No | No | No | $3,252,972 | $0.31 |

| AL* | No | n/a | n/a | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | $1,426,822 | $0.28 |

| CT* | No | n/a | n/a | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | $956,646 | $0.27 |

| FL* | No | n/a | n/a | Yes | No | No | No | No | $5,284,388 | $0.24 |

| KY* | No | n/a | n/a | Yes | No | No | No | No | $1,163,404 | $0.26 |

| MO* | No | n/a | n/a | Yes | No | No | No | No | $1,850,668 | $0.30 |

| PA* | No | n/a | n/a | Yes | No | No | No | No | $3,187,862 | $0.25 |

| SD* | No | n/a | n/a | Yes | No | No | No | No | $250,000 | $0.28 |

| VT* | No | n/a | n/a | Yes | No | No | No | No | $250,000 | $0.39 |

| AK | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $- | $- |

| AR | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $815,327 | $0.27 |

| AZ | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $1,953,661 | $0.27 |

| DE | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $250,000 | $0.25 |

| HI | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $490,942 | $0.34 |

| IA | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $932,900 | $0.29 |

| IN | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | Yes | No | No | $2,016,340 | $0.30 |

| MA | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | $2,563,100 | $0.36 |

| ME | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $268,996 | $0.20 |

| MT | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $392,091 | $0.36 |

| ND | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $250,000 | $0.32 |

| NE | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | Yes | No | $631,041 | $0.32 |

| NH | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $338,302 | $0.25 |

| NV** | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | $1,069,192 | $0.34 |

| OH | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $3,315,098 | $0.28 |

| OK | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $1,047,986 | $0.26 |

| TN | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $1,688,142 | $0.24 |

| TX | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | Yes | No | $8,367,877 | $0.29 |

| WI | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $1,787,657 | $0.30 |

| WV | No | $0.00 | $0.00 | No | No | No | No | No | $561,131 | $0.31 |

Amount dedicated to Lifeline 988 centers for 988 implementation is likely to be more than $0 because these states earmarked funds for crisis services explicitly in response to 988 implementation, but did not specify the amount dedicated to 988 Lifeline Centers (the focus of the current study).

State has passed 988 cell phone user fee legislation but had not allocated funds from the fee at the time of the study. Revenue generated from the fee not included in the amount earmarked for 988 Lifeline centers.

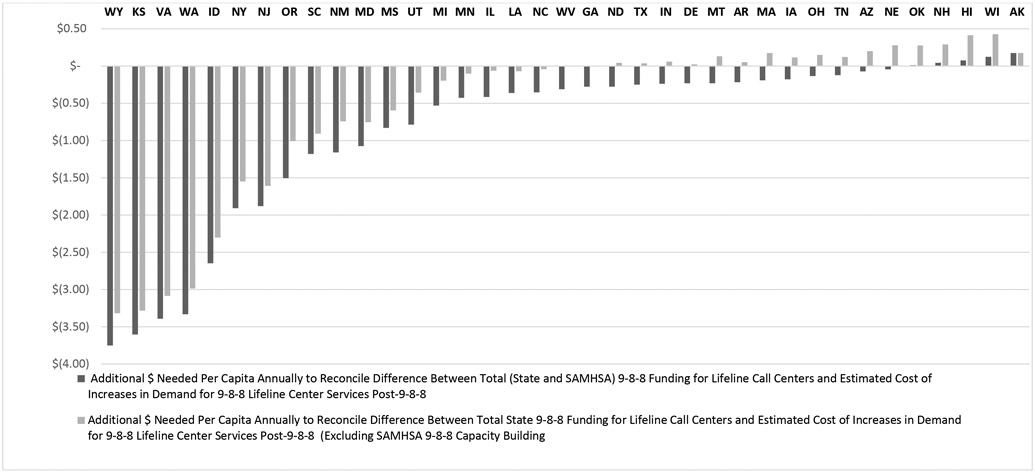

Figure 1 charts the magnitude of differences between the estimated additional per capita cost of covering increases in call demand at 988 Lifeline centers post-988 and the amount of state and SAMHSA 988 capacity building grant funding. The chart excludes Maine because of incomplete data about increased demand and excludes states that earmarked funds for crisis services in response to 988, but not 988 Lifeline centers explicitly, because of uncertainty about the amount of funds dedicated to 988 Lifeline centers. Bars below zero on the chart indicate a potential surplus and bars above zero indicate a potential deficit.

Figure 1: Magnitude of Differences between Estimated Additional Per Capita Cost of Covering Increases in Call Demand for 988 Lifeline Center Services Post-988 and Amount of State and SAMHSA Funding Earmarked for 988 Lifeline Centers in Response to 988, 2023.

Note: ME excluded because of incomplete data about increased demand and excludes states that earmarked for crisis Services in response to 988, but not 988 Lifeline centers explicitly, because of uncertainty about the amount of these funds which may be dedicated to 988 Lifeline centers. AL, CT, FL, KY, MO, PA, SD, VT excluded because of uncertainty about the amount funds earmarked for 988 Lifeline centers.

When FY 2023 state and FY 2022 SAMHSA 988 capacity building funding was considered together, 988-specific funding for 988 Lifeline centers exceeded the estimated costs of increases in call volume post 988 in 33 of the 38 states included in the analysis states (87% of those analyzed in Figure 1) and was insufficient in five states (13% of those analyzed). Among the five states for which funding was estimated to be insufficient (AK, HI, NH, OK, WI), the mean additional amount needed per state resident was $0.09 (SD= $0.06). When only state funding earmarked for 988 Lifeline centers in response 988 implementation was considered (i.e., when SAMHSA 988 capacity building grant funding was excluded), state funding exceeded estimates of increased cost in 19 states (50%), were insufficient in 17 states (45% of those analyzed), and equivalent in two states (5% of those analyzed). Among the 19 states for which funding was estimated to be insufficient, the mean additional amount needed per state resident was $0.17 (SD= $0.13).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study presents the first empirical state-level estimates of the cost implications of 988 for Lifeline centers and the extent to which state and some federal appropriations earmarked for increased in call volume are likely to be sufficient to meet increased call volume demand. We find that Lifeline call volume increased in all states following the Lifeline’s transition to a three-digit dialing code (i.e., 988) and expansion of scope from exclusively suicide to suicide and mental health crisis more broadly. The estimated additional annual spending needed per capita to meet this increased demand ($0.14) is small relative other categories of mental health spending. For context, SAMHSA’s 2021 mental health spending in equates to $5.38 per U.S. resident.(47)

We find that the magnitude of the increase and associated costs varied considerably between states. We also find that state appropriations earmarked for increases in 988 Lifeline centers for FY 2023 are likely to be sufficient in only about half of states. Thus, sustained federal funding and/or increases in state funding earmarked for 988 Lifeline centers are likely important to ensuring that 988 Lifeline centers have the capacity to meet service demand in the post-988 implementation environment.

Nationally, we find that state-level 988 Lifeline call volume increased by about 33% in the four months following 988 implementation (compared to the same four months the prior year, which exceeds the historical between-year average increase in Lifeline Center call volume of 14%(12)). However, the magnitude of increase varied substantially between states (SD= 20.5%). An important area for future research relates to identifying factors that explain between state variation in increases in call volume. Such variation could be explained, for example, by epidemiological factors—such as differing trends in psychological distress and suicidality between states—or variation in the intensity and effectiveness of 988 public awareness campaigns launched by states.

We find that many state legislatures took fiscal action in response to the federal law that created 988. About two-thirds of states earmarked appropriations to support 988 implementation in FY 2023. Among the 22 states that explicitly earmarked funds for 988 Lifeline centers in response to 988, the average amount per capita in the two states that allocated revenue from cell phone user fee legislation was almost four times that of those that did not allocate funds from user fee legislation ($4.71 vs $1.19). As these amounts far exceed estimates of the annual per capita costs of increases in 988 Lifeline call volume, an important area for research relates to how to best allocate such funds across different elements of crisis response systems (i.e., mobile crisis response teams, 24-hour crisis stabilization centers, and 988 Lifeline centers) as well as the mental health systems more broadly where follow-up services are provided.

Over one-third of states not did not pass any financing legislation and/or earmark budget appropriations explicitly related to 988. It should be noted, however, that sixteen states enacted budget biennially and set their FY 2023 budget during the 2021 legislative session—as opposed to the 2022 session (44)—when 988 implementation was less immediate. Future research should explore whether state-level crisis system quality metrics (e.g., 988 Lifeline in-state answers rates,(33) mobile crisis response team contact rates (48)) and clinical outcomes (37) are associated with the structure and per capita amount of state funding for 988 implementation. Future research should also explore how Medicaid funding can be used for 988 Lifeline center services—such as through 1115, 1915(a), and 1915(b) waivers (49, 50) and consistent with recent guidance from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services—to promote sustainable financing.(51-53)

Key Assumptions, Limitations, and Areas for Future Research

The results of our study should be considered within the context of its assumptions and limitations, many of which represent areas for future research. In terms of our estimates of the magnitude of annual increases in Lifeline call volume post-988 implementation, the accuracy of these estimates hinges on the assumption that the increase in the four months observation period (i.e., August- November) remains constant for the for the entire year. This assumption can be assessed, and estimates can be updated, as more recent 988 Lifeline call volume data become available.

In terms of state appropriations earmarked explicitly for 988 Lifeline centers in response to 988 implementation, a key assumption is that this funding did not supplant baseline funding for Lifeline centers provided prior to 988 implementation. If such supplantation occurred, then our estimates of funding increases would be inflated and funding would be sufficient to meet call demand in fewer states. It should also be noted that many states made substantive investments to support 988 implementation in FY 2022 (e.g., Georgia, $114 million, equating to $10.63 per capita) and these appropriations were not accounted for in our FY 2023 analysis. Future research could assess cumulative appropriations toward 988 implementation across fiscal years. Also, given the focus the study, we did not include appropriations for crisis services and systems which were not in explicit response to 988 implementation.

A critical assumption of our cost estimates is that SAMHSA’s estimate of the cost of a single 988 Lifeline center call ($82) is reasonably accurate and uniform across states. Although SAMHSA lists the inputs of this costs estimate, limited details are provided about the data sources or costing methodology used.(12) There would be value in future cost studies that produce state or regional estimates of the cost of a single 988 Lifeline center call. Among other factors that could affect the accuracy of the cost estimate, the normalization of remote work post-COVID-19 pandemic could affect dimensions of the estimate related to facilities (e.g., rent).

It should be emphasized that the study was exclusively from the perspective of funding for 988 Lifeline centers. Not suicide prevention and mental health crisis call centers that are not affiliated with the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline and non-affiliated call center are approximately twice as numerous as 988 Lifeline centers.(27) Furthermore, increases in 988 Lifeline call volume have cost implications for not only 988 Lifeline centers, but also mobile crisis response teams, 24-hour crisis stabilization centers, and other mental health services that are provided following the initial contact with a 988 Lifeline center. Cost estimates of these services exist,(38, 54, 55) and the proportion of 988 Lifeline calls that result in connection to these services can plausibility be calculated.(12) With these data, more comprehensive estimates of the cost implications of 988 implementation could be produced.

The study focused on calls to 988 Lifeline Centers and not chats or texts. Although some Lifeline centers received contacts via chat and text prior to 988 implementation, the volume of contacts through these modes increased substantially post 988 implementation as they were marketed explicitly with 988 rollout. There are cost implications of these increases which were not examined in the study.

Finally, we observed some inconsistencies between the various 988 legislation tracking databases/reports (28, 42-45) and our independent review of state documents and websites. These inconstancies appear to be the result of complexities such as: conflation of calendar years and fiscal years; different fiscal year periods between states; incongruencies between the amount of funds generated (e.g., from cell phone user fees), appropriated, and distributed; and inconsistent definitions of what is considered spending on 988 Lifeline centers, crisis systems more broadly, and what is counted as 988-related appropriations as opposed to non-988 related crisis system appropriations. These issues highlight the importance of more legal and public administration research related to 988 financing.

CONCLUSIONS

The Lifeline’s transition to 988 increased 988 Lifeline call volume in all states, but the magnitude of the increase and associated cost was heterogenous across states. State funding earmarked for increases in 988 Lifeline center costs is sufficient in about half of states. Sustained federal funding, and/or increases in state funding, earmarked for 988 Lifeline centers is likely important to ensuring that 988 Lifeline centers have the capacity to meet call demand in the post-988 implementation environment.

Funding:

National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH131649)

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad FB, Anderson RN. The leading causes of death in the US for 2020. JAMA. 2021;325(18):1829–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martínez-Alés G, Jiang T, Keyes KM, Gradus JL. The recent rise of suicide mortality in the United States. Annual review of public health. 2021;43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Suicide rates in the United States continue to increase: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. Trends in Extreme Distress in the United States, 1993–2019. American Journal of Public Health. 2020;110(10):1538–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SAMHSA. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Port MS, Lake AM, Hoyte-Badu AM, Rodriguez CL, Chowdhury SJ, Goldstein A, Murphy S, Cornette M, Gould MS. Perceived impact of COVID-19 among callers to the national suicide prevention lifeline. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention. 2022. Sep 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yard E, Radhakrishnan L, Ballesteros MF, Sheppard M, Gates A, Stein Z, et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12-25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019–May 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2021;70(24):888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland KM, Jones C, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Idaikkadar N, Zwald M, Hoots B, et al. Trends in US emergency department visits for mental health, overdose, and violence outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA psychiatry. 2021;78(4):372–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britton PC, Karras E, Stecker T, Klein J, Crasta D, Brenner LA, Pigeon WR. Veterans crisis line call outcomes: treatment contact and utilization. American journal of preventive medicine. 2023. Feb 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Britton PC, Karras E, Stecker T, Klein J, Crasta D, Brenner LA, Pigeon WR. Veterans crisis line call outcomes: Distress, suicidal ideation, and suicidal urgency. American journal of preventive medicine. 2022. May 1;62(5):745–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.SAMHSA. 2021. 988 Appropriations Report. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/988-appropriations-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalafat J, Gould MS, Munfakh JLH, Kleinman M. An evaluation of crisis hotline outcomes. Part 1: Nonsuicidal crisis callers. Suicide and Life-threatening behavior. 2007;37(3):322–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gould MS, Kalafat J, HarrisMunfakh JL, Kleinman M. An evaluation of crisis hotline outcomes. Part 2: Suicidal callers. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2007;37(3):338–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gould MS, Chowdhury S, Lake AM, Galfalvy H, Kleinman M, Kuchuk M, et al. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline crisis chat interventions: Evaluation of chatters’ perceptions of effectiveness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gould MS, Lake AM, Galfalvy H, Kleinman M, Munfakh JL, Wright J, et al. Follow-up with callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: Evaluation of callers’ perceptions of care. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2018;48(1):75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould MS, Cross W, Pisani AR, Munfakh JL, Kleinman M. Impact of applied suicide intervention skills training on the national suicide prevention lifeline. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2013;43(6):676–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gould MS, Munfakh JL, Kleinman M, Lake AM. National suicide prevention lifeline: enhancing mental health care for suicidal individuals and other people in crisis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2012;42(1):22–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gould MS, Lake AM, Munfakh JL, Galfalvy H, Kleinman M, Williams C, et al. Helping callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline who are at imminent risk of suicide: Evaluation of caller risk profiles and interventions implemented. 2016;46(2):172–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gould MS, Lake AM, Galfalvy H, Kleinman M, Munfakh JL, Wright J, et al. Follow-up with callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: Evaluation of callers’ perceptions of care. 2018;48(1):75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niederkrotenthaler T, Tran US, Gould M, Sinyor M, Sumner S, Strauss MJ, Voracek M, Till B, Murphy S, Gonzalez F, Spittal MJ. Association of Logic’s hip hop song “1-800-273-8255” with Lifeline calls and suicides in the United States: interrupted time series analysis. bmj. 2021. Dec 13;375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niederkrotenthaler T, Tran US, Baginski H, Sinyor M, Strauss MJ, Sumner SA, Voracek M, Till B, Murphy S, Gonzalez F, Gould M. Association of 7 million+ tweets featuring suicide-related content with daily calls to the Suicide Prevention Lifeline and with suicides, United States, 2016–2018. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2022. Oct 14:00048674221126649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hogan MF, Goldman ML. New opportunities to improve mental health crisis systems. Psychiatric Services. 2021. Feb 1;72(2):169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zabelski S, Kaniuka AR, Robertson RA, Cramer RJ. Crisis lines: current status and recommendations for research and policy. Psychiatric services. 2022. Dec 7:appi-ps. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller AB, Oppenheimer CW, Glenn CR, Yaros AC. Preliminary research priorities for factors influencing individual outcomes for users of the US National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. JAMA psychiatry. 2022. Dec 1;79(12):1225–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fix RL, Bandara S, Fallin MD, Barry CL. Creating comprehensive crisis response systems: an opportunity to build on the promise of 988. Community mental health journal. 2022. Aug 23:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NRI. 2022. Financing Behavioral Health Crisis Services: 2022. https://www.nri-inc.org/media/pa3i4qjl/financing-bh-crisis-services-final-2022.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephenson AH (2022). States’ Experiences in Legislating 988 and Crisis Services Systems. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/2022_nasmhpd_StatesLegislating988_022922_1753.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Awards More Than $130 Million in 988 Lifeline Grants From the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act to Address Nation’s Ongoing Mental Health and Substance Use Crises. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/12/16/hhs-awards-more-than-130-million-988-lifeline-grants-bipartisan-safer-communities-act-address-nations-ongoing-mental-health-substance-use-crises.html#:~:text=In%20total%2C%20the%20Biden%20Administration,Act%20and%20other%20funding%20streams. [Google Scholar]

- 30.SAMHSA. SM-22-015 Individual Grant Awards 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/awards/2022/SM-22-015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cantor Jonathan H., Stephanie Brooks Holliday Ryan K. McBain, Matthews Samantha, Bialas Armenda, Eberhart Nicole K., and Breslau Joshua, Preparedness for 988 Throughout the United States: The New Mental Health Emergency Hotline. Santa Monica, CA: RAND. Corporation, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA1955-1-v2.html. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vibrant Emotional Health. 988 Lifeline Transition Volume. https://www.vibrant.org/988-lifeline-transition-volume/. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Purtle J, Lindsey MA, Raghavan R, Stuart EA. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 2020 in-state answer rates, stratified by call volume rates and geographic region. Psychiatric services. 2022. Jul 14:appi-ps. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Purtle J, Rivera-González AC, Mercado DL, Barajas CB, Chavez L, Canino G, Ortega AN. Growing inequities in mental health crisis services offered to indigent patients in Puerto Rico versus the US states before and after Hurricanes Maria and Irma. Health Services Research. 2022. Oct 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalb LG, Holingue C, Stapp EK, Van Eck K, Thrul J. Trends and Geographic Availability of Emergency Psychiatric Walk-In and Crisis Services in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(1):26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newton H, Beetham T, Busch SH. Association of Access to Crisis Intervention Teams With County Sociodemographic Characteristics and State Medicaid Policies and Its Implications for a New Mental Health Crisis Lifeline. JAMA Network Open. 2022. Jul 1;5(7):e2224803-. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kandula S, Higgins J, Goldstein A, Gould MS, Olfson M, Keyes KM, Shaman J. Trends in crisis hotline call rates and suicide mortality in the United States. Psychiatric services. 2023. Mar 6:appi-ps. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purtle J, Brinson K, Stadnick NA, editors. Earmarking Excise Taxes on Recreational Cannabis for Investments in Mental Health: An Underused Financing Strategy. JAMA Health Forum; 2022: American Medical Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vibrant Emotional Health. Our Network. https://988lifeline.org/our-network/. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woo JM, Okusaga O, Postolache TT. Seasonality of suicidal behavior. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2012. Feb;9(2):531–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ajdacic-Gross V, Bopp M, Ring M, Gutzwiller F, Rossler W. Seasonality in suicide–A review and search of new concepts for explaining the heterogeneous phenomena. Social science & medicine. 2010. Aug 1;71(4):657–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Alliance on Mental Illness. 988 Crisis Response State Legislation Map. https://reimaginecrisis.org/map/. [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Academy for State Health Policy. State Legislation to Fund and Implement ‘988’ for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. https://www.nashp.org/state-legislation-to-fund-and-implement-988-for-the-national-suicide-prevention-lifeline/. [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. 2022. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/nasmhpd2205_988State-StateLeg_Dec2022_121522_508.pdf. State-by-State Legislative Analysis of Funding for 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/nasmhpd2205_988State-StateLeg_Dec2022_121522_508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 45.Federal Communications Comission. 2022. 988 Fee Accountability Report. https://www.fcc.gov/document/988-fee-accountability-report. [Google Scholar]

- 46.SAMHSA. Cooperative Agreements for States and Territories to Build Local 988 Capacity. https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/grant-announcements/sm-22-015. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Purtle J, Wynecoop M, Crane M, Stadnick N Earmarked Taxes for Mental Health Services in the United States: A Local and State Legal Mapping Study. The Milbank Quarterly. In press. Accepted March 23, 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldman ML, Ponce AN, Thomas M, Felder S, Wu S, Loewy R, Mangurian C. Field visit contact rate by mobile crisis teams as a crisis system performance metric. Psychiatric services. 2022. Dec 13:appi-ps. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crisis Now. Overview of Crisis Funding Sources Available to States and Localities.; 2022. https://crisisnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/20220302_OverviewOfCrisisFundingSources.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wachino Vikki, Camhi Natasha. Building Blocks: How Medicaid Can Advance Mental Healht and Substance Use Crisis Response. Well Being Trust; 2021. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://wellbeingtrust.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/WBT-Medicaid-MH-and-CrisisCareFINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. SMD # 18--011 RE: Opportunities to Design Innovative Service Delivery Systems for Adults with a Serious Mental Illness or Children with a Serious Emotional Disturbance.; 2018. Accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd18011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stephenson Arlene H.. States’ Options and Choices in Financing 988 and Crisis Services Systems. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2022. Accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/6.25.2022_FINAL_Financing988.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. June a2021 Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP.; 2021. Accessed December28, 2022. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/june-2021-report-to-congress-on-medicaid-and-chip/. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott RL. Evaluation of a mobile crisis program: effectiveness, efficiency, and consumer satisfaction. Psychiatric Services. 2000. Sep;51(9):1153–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crisis Resource Need Calculator. https://calculator.crisisnow.com/#/. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. June 2021 Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP.; 2021. Accessed December 28, 2022. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/june-2021-report-to-congress-on-medicaid-and-chip/. [Google Scholar]