Abstract

Objectives

The Health & Her app provides menopausal women with a means of monitoring their symptoms, symptom triggers and menstrual periods, and enables them to engage in a variety of digital activities designed to promote well-being. This study aimed to examine whether sustained weekly engagement with the app is associated with improvements in menopausal symptoms.

Design

A pre–post longitudinal cohort study.

Setting

Analysed data collected from Health & Her app users.

Participants

1900 women who provided symptom data via the app across a 2-month period.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Symptom changes from baseline to 2 months was the outcome measure. A linear mixed effects model explored whether levels of weekly app engagement influenced symptom changes. Secondary analyses explored whether app-usage factors such as total number of days spent logging symptoms, reporting triggers, reporting menstrual periods and using in-app activities were independently predictive of symptom changes from baseline. Covariates included hormone replacement therapy use, hormonal contraceptive use, present comorbidities, age and dietary supplement use.

Results

Findings demonstrated that greater engagement with the Health & Her app for 2 months was associated with greater reductions in symptoms over time. Daily use of in-app activities and logging symptoms and menstrual periods were each independently associated with symptom reductions.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that greater weekly engagement with the app was associated with greater reductions in symptoms. It is recommended that women be made aware of menopause-specific apps, such as that provided by Health & Her, to support them to manage their symptoms.

Keywords: GYNAECOLOGY, Reproductive medicine, Health informatics, Telemedicine, Quality of Life, MENTAL HEALTH

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Outcome measures (ie, symptom changes) were self-reported.

This study was not randomised.

This study controlled for multiple factors known to influence symptoms during menopause.

This study included a large sample of perimenopausal and menopausal women (N=1900).

Introduction

Menopause is a naturally occurring reproductive phase in which women permanently cease to menstruate. Menopause is associated with a number of symptoms, which in some women, can heavily impact health and quality of life.1The main treatment for menopausal symptoms is hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Despite menopause encompassing a wide variety of symptom domains, including psychological issues, HRT is currently only indicated for alleviating vasomotor and genitourinary symptoms.2 Thus, there is a need to identify alternative interventions to HRT, which could support women to manage their health during menopause.

Use of freely available mobile health (m-health) apps has been associated with improved health outcomes. Zhaunova et al3 found that an app which enabled women to monitor their menstrual periods was associated with improvements in physical and psychological symptoms. A study by McCloud et al4 demonstrated that an app which provided digital cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) activities and mood monitoring was associated with improvements in anxiety and depression symptoms.

Studies in women experiencing menopausal symptoms suggest that symptom monitoring can improve symptoms, reduce negative emotions and could heighten health awareness, helping women avoid behaviours which could negatively impact their health.5 6 Therefore, digital apps which support symptom monitoring, as well as providing women with menstrual tracking and therapeutic activities, may be useful for improving symptoms during menopause.

Furthermore, among women who choose to use HRT or other interventions for their menopausal symptoms, such as dietary supplements or exercise therapies, adjunct digital tools may be beneficial for helping them track the impact and efficacy of these treatments.

Aims and research questions

A recent systematic review found evidence that, of the 28 UK menopause apps reviewed, none of these apps had been evaluated via peer-reviewed research.7 To identify any potential health implications, m-health apps need to be scientifically evaluated in terms of harms and benefits to health. Therefore, our key objective is to examine whether use of the Health & Her iOS and Android mobile phone app is associated with symptom changes.

The Health & Her app enables women to track their menopausal symptoms, symptom triggers and menstrual periods. The app also provides users with a range of activities which can help them manage their menopausal symptoms including CBT, pelvic floor and meditation exercises. The app also signposts users to health and lifestyle articles written by experts such as general practitioners and psychologists, as well as products which are designed to support wellness, including own-brand Health & Her dietary supplements, and dietary supplements of external brands.

We present a longitudinal pre–post cohort study of symptom changes using the Health & Her app. The primary aim of this study was to explore whether use of the Health & Her app was associated with changes in symptoms over 2 months. Our secondary aim was to explore whether increased app engagement was associated with greater changes in menopausal symptoms. Therefore, participants were grouped and compared according to the number of separate weeks they had engaged with the Health & Her app. Within these groups, we observed whether the changes in symptom scores reported by women were statistically significant, by comparing symptom reports at the point of first app use with consecutive symptom reports provided throughout 2 months of app use. The Health & Her app also collects data on medical history, medications and dietary supplements used and lifestyle factors (ie, symptom triggers such as alcohol consumption, smoking), enabling us to control for a number of factors in our analysis. Therefore, we addressed the following research questions:

After controlling for covariates, is the Health & Her app associated with symptom changes across a 2-month period?

Does level of engagement with the Health & Her app influence symptom changes?

Methods

Study context and design

This analysis encompasses a longitudinal pre–post assessment of Health & Her app data collected between October 2020 and January 2023. This study examined the effect of app engagement on symptom changes across 2 months of app use. This study included women who had reported their symptoms before and after 2 months of Health & Her app use. To examine the impact of app engagement, participants were grouped according to the number of separate weeks they had engaged with the app; engagement was defined as using the app to log a symptom, menstrual period, trigger or to complete an in-app activity. Levels of engagement ranged from two separate weeks (they engaged with the app within the first and last week of the 2-month period only) to 9 separate weeks (they engaged with the app within every week of the 2-month period). Thus, this study encompassed eight distinct app engagement groups: 2 weeks, 3 weeks, 4 weeks, 5 weeks, 6 weeks, 7 weeks, 8 weeks and 9 weeks.

The repeated measures variable was symptom score, which was calculated for each day participants logged their symptoms. The dependent variable was symptom change scores, which was calculated by subtracting each consecutive symptom score from the baseline symptom score, until the final one provided by all participants at 2 months. As participants varied in the number of days they logged their symptoms via the app, the present study used an unbalanced design. For example, some participants may have provided 62 symptom scores (ie, they had logged every day of the 2-month period), whereas others may have two symptom scores (ie, they had logged symptoms at the beginning and end of the 2-month period only). To account for this imbalance, the main analysis involved a linear mixed effects model.

Participants

Inclusion

This study included anonymised data from women who downloaded the Health & Her app, had consented to their data being used for research purposes, and had reported their symptoms both pre and post 2 months of app use. Applying this inclusion criteria to over 150 000 women who had downloaded the app and had answered all prerequisite questions to access the app’s facilities, we arrived at a final sample of 1900 women, who collectively provided a total of 31 076 distinct symptom observations. Women were made aware of the app through social media adverts, the Health & Her website, word of mouth, the IOS app store, Google Play Store (https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.healthandher&hl=en_GB&gl=US) or through seeing app advertisements on Health & Her brand supplements bought in store or online through a retailer or directly from the Health & Her website. Health & Her advertisements are designed to focus on women of perimenopausal and menopausal age, who have indicated an online interest in menopause, and who live in the UK. The app is freely available on IOS and android via the app store or Google play store. All data were fully anonymised prior to analysis. Participants were linked using individual identification codes, these codes are routinely created for all Health & Her app users via Amazon Web Services (AWS).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or development of research questions. However, because the app is freely available to anyone with a smartphone, the public and likely patients who have accessed health services for issues relating to menopause, have been included as participants.

Data collection

The Health & Her app

After first downloading and opening the app, users are asked to engage with an onboarding process which asks users to provide information on their age, medical history, HRT use, hormonal contraceptive use, menopausal status, dietary supplement usage and current menopausal symptoms. Once all onboarding questions have been answered users are allowed to begin tracking their menopausal symptoms, as well as their symptom triggers and menstrual cycles if they are still experiencing periods. Users are also allowed to create a plan by setting daily goals using digital in-app activities designed to improve menopausal symptoms and heighten psychological well-being. Activities include CBT exercises (CBT for loss of sex drive, CBT for low mood, CBT for hot flushes), a guided sleep meditation exercise, a paced-breathing exercise, stress and anxiety meditation exercise, a pelvic floor exercise timer, drink water reminders, and HRT and supplement reminders. Triggers include lifestyle and situational factors which could increase or worsen symptoms, such as stress at work, alcohol consumption and smoking. The app also provides women with articles to help them learn more about menopause, and strategies they can undertake to help them manage their symptoms. Women are encouraged to return to the app to track their symptoms, periods, and symptom triggers, or complete digital activities through scheduled push notifications (if the user has enabled notifications on their mobile device).

Symptom scores

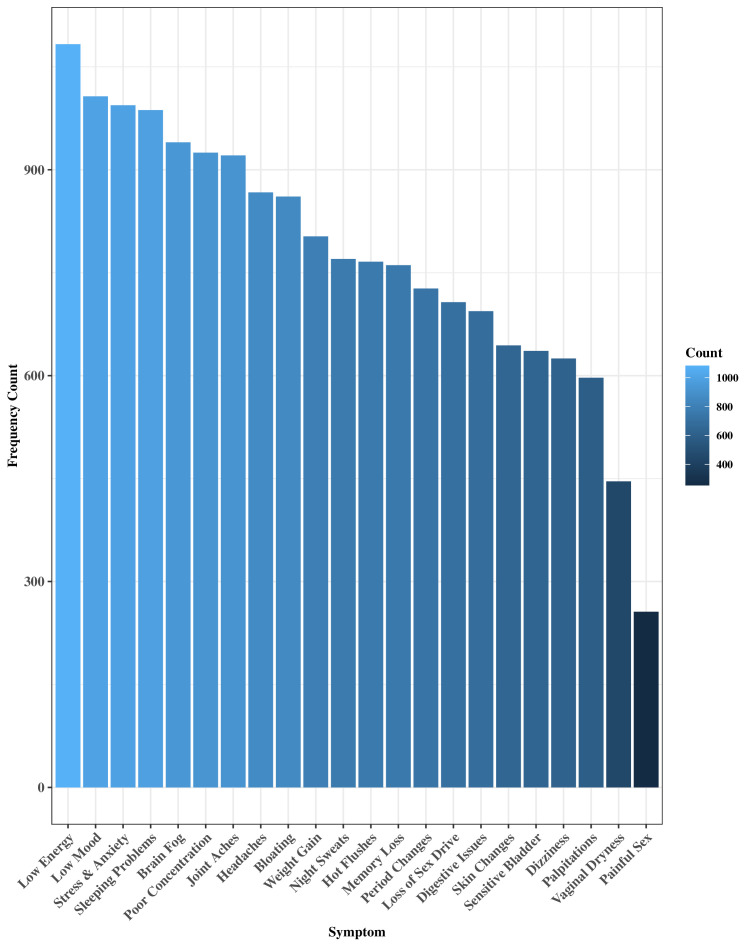

Health & Her app users are invited to report their menopausal symptoms and concurrent symptom severities using a list of 22 common menopausal symptoms. Symptom severities range from 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), to 3 (severe). Figure 1 shows menopausal symptoms and their frequency distributions in the cohort. Using the methods employed in previous research using the daily record keeping form,6 8 symptom scores were calculated for each instance the user logged their symptoms by multiplying total number of symptoms with their average symptom severity, for example, hot flushes (severity=1), sleeping problems (severity=2), night sweats (severity=3) would result in a total symptom score of=6. A continuous symptom difference score was calculated to observe how symptoms increased or decreased throughout the 2-month app usage period. Therefore, a symptom score was calculated for each instance users input their symptoms into the app, and symptom change scores were calculated by subtracting each consecutive symptom score from the baseline symptom score, up until endpoint at 2 months.

Figure 1.

Menopausal symptom distributions across the full sample.

Engagement

App engagement was quantified by counting the number of distinct weeks users engaged with the app (weeks engaged) to log symptoms, triggers, periods or complete in-app activities within the 2-month span. Factors relating to app usage were assessed to evaluate and control for their independent effects, including daily use of symptom logging, trigger logging, reporting menstrual periods and use of activities featured within the app. The total number of days women logged their symptoms, logged symptom triggers, logged periods or completed in-app activities across the 2-month period were examined as continuous variables.

Covariates

Covariates were included to control for their effects on symptom improvement and heighten statistical accuracy, reduce bias and enable a more accurate representation of the effects of app engagement.

The following covariates were added as dichotomous yes/no variables: HRT usage, hormonal contraceptive usage, current self-reported medical conditions (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome, fibroids, endometriosis, premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder, pre/postnatal depression, gestational diabetes, depression, anxiety, cancer, adenomyosis, autoimmune diseases, premature ovarian failure). Age was added as a continuous variable. As the Health & Her app is advertised alongside the Health & Her brand supplements, it was important to evaluate variances in outcomes among women who used Health & Her supplements. Therefore, supplement use was compared as a factor with four levels, not using any supplements, external supplements (ie, using a brand other than Health & Her’s), using Health & Her brand supplements only, and using both Health & Her and external supplements. It was important to control for the effects of using Health & Her brand supplements in order to account for placebo or expectation effects among Health & Her supplement customers.

To control for individual variations in symptom reporting, baseline symptom scores were added as covariates. However, to evaluate the independent effect of specific symptom types reported at baseline, baseline symptom scores were split according to physical symptoms at baseline=headaches, digestive issues, bloating, dizziness, skin changes,joint aches, period changes, palpitations, weight gain; psychological symptoms at baseline=low mood, stress and anxiety, low energy, brain fog, memory loss, poor concentration; urogenital symptoms at baseline=sensitive bladder, vaginal dryness, painful sex, loss of sex drive and vasomotor symptoms at baseline=hot flushes, night sweats, sleeping problems.

Data analysis

No data were missing from the final sample. The anonymised data were directly obtained by the lead author from Health & Her’s databank, hosted on Amazon Web Services (AWS; available at: https://aws.amazon.com). Statistical analyses were computed via R Studio V.4.02.9 The main analysis involved a linear mixed effects model, which was computed using R package ‘lme4’.10 To control for individual variances, participant ID was added as a random effect. A forest plot was developed using R package SjPlot11 to visually assess the direction of the effects of all predictor variables. Using R package ‘emmeans’,12 a pairwise comparison plot was computed, which visually depicted symptom changes at the beginning and end of the 2-month period for each weekly engagement group, while controlling for the effects of covariates. As it is not recommended to compare CIs side by side in mixed-methods designs, comparison arrows were computed to visualise significant within-group differences.12 Frequency counts (N, %) were computed to assess the distribution of menopausal status, menopausal symptoms, app usage variables, current comorbidities and medication use across the present sample. Differences between weekly app engagement groups in terms of sample characteristics were established via Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests (for age, days engaged in symptom logging/trigger logging/period logging/use of in-app activities and baseline/follow-up symptom score) and Pearson’s χ2 tests (for HRT use, supplement use, and contraceptive use, and current comorbidities) using R package gtSummary.13 Benjamini and Hochberg p value corrections were applied to control for the effects of multiple comparisons.

Power

Using R package ‘simr’,14 a power analysis was calculated to assess the extent to which the present sample size could accurately detect true significant effects of weekly engagement. This analysis demonstrated that our study had 99.80% (95% CI (99.42% to 99.96%)) power in detecting the true effects of weekly app engagement.

Results

Sample characteristics

The mean age of participants was 48 (SD=4.7). Most participants were perimenopausal (n=1402, 74%), 16% (n=298) of participants were unsure of their menopausal status due to using HRT or hormonal contraceptives, 9% (n=181) were menopausal, and a small number were postmenopausal (n=19, <1%). Approximately half reported medical comorbidities (53%) and 53% were not currently using dietary supplements. The average time between first and final symptom log was 60.35 (SD=1.96) days. As shown in figure 1, the most common menopausal symptoms were low energy (65%), low mood (59%), sleeping problems (58%), stress and anxiety (58%), whereas least common symptoms included painful sex (16%) and vaginal dryness (28%).

Between-group variances

Online supplemental table 1 shows the differences in scores between the app engagement groups for the present sample. Participants varied between groups in terms of age: women who engaged with the app for 2 or 3 weeks tended to be older than women who engaged for 4 weeks or more (p<0.001). The groups also differed in app usage. Frequency of days women logged symptoms, periods, activities and triggers increased according to the number of weeks engaged (p<0.001). Final symptom scores were statistically lower as weeks engaged increased (p<0.001). On adjustment of multiple comparison testing, participants did not vary in terms of other sample characteristics.

bmjopen-2023-077185supp001.pdf (20.9KB, pdf)

Linear mixed effects model

Table 1 shows the summary statistics from the linear mixed effects model which examined the effects of weeks engaged, app-usage variables and covariates on symptom changes across the 2-month period.

Table 1.

Linear mixed effects model of predictors of symptom change scores

| Characteristic | B | 95% CI |

| Urogenital symptoms | −0.46 | −0.61 to –0.32 |

| Vasomotor symptoms | −0.45 | −0.58 to –0.32 |

| Psychological symptoms | −0.54 | −0.62 to –0.46 |

| Physical symptoms | −0.42 | −0.50 to –0.34 |

| Age | 0.00 | −0.06 to 0.06 |

| HRT | −0.24 | −1.1 to 0.62 |

| Supplements | ||

| None | — | — |

| Both | −0.54 | −1.6 to 0.55 |

| External Only | 0.39 | −0.24 to 1.0 |

| Health & Her only | −1.3 | −2.2 to –0.35 |

| Hormonal contraceptives | −0.01 | −0.73 to 0.72 |

| Current comorbidities | 0.94 | 0.38 to 1.5 |

| Trigger logs | 0.05 | 0.02 to 0.08 |

| Activity logs | −0.03 | −0.06 to –0.01 |

| Period logs | −0.12 | −0.21 to –0.03 |

| Symptom logs | −0.06 | −0.10 to –0.01 |

| Weeks engaged | ||

| 2 | — | — |

| 3 | −1.2 | −2.2 to –0.26 |

| 4 | −2.7 | −3.8 to –1.6 |

| 5 | −2.6 | −3.7 to –1.5 |

| 6 | −3.3 | −4.5 to –2.0 |

| 7 | −3.2 | −4.5 to –1.8 |

| 8 | −3.8 | −5.2 to –2.3 |

| 9 | −4.0 | −5.8 to –2.3 |

HRT, hormone replacement therapy.

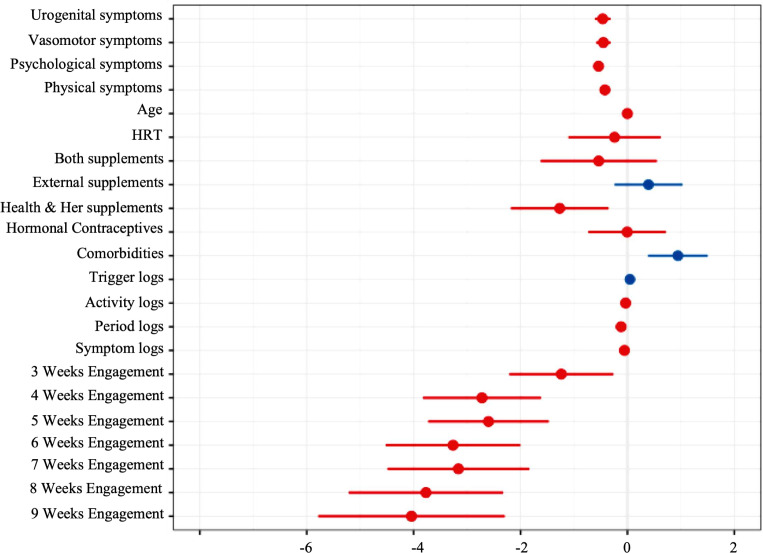

These findings indicate that increasing weeks engaged is statistically significantly associated with lower symptom total: at 3 weeks, b=−1.2, 95% CI (95% CI −2.2 to –0.26), 4 weeks b=−2.7 (95% CI −3.8 to –1.6), 5 weeks b=−2.6 (95% CI −3.7 to –1.5), 6 weeks b=−3.3 (95% CI −4.5 to −2.0), 7 weeks b=−3.2 (95% CI −4.5 to –1.8), 8 weeks b=−3.8 (95% CI −5.2 to –2.3) and 9 weeks b=−4.0 (95% CI −5.8 to –2.3). Beta statistics indicate that app engagement predicted greater reductions in symptoms as the number of weeks engaged increased. Reporting a current comorbidity b=0.94 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.5) and trigger logging were predictive of increased symptom scores b=0.05 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.08) whereas Symptom logging b=−0.06 (95% CI −0.10 to –0.01), period logging b= −0.12 (95% CI −0.21 to –0.03) and completing in-app activities were related to reduced symptoms b=−0.03 (95% CI −0.06 to –0.01). Taking a Health & Her brand supplement was also related to reduced symptoms b=−1.3 (95% CI −2.2 to –0.35).

Out of the four symptom domains, reporting psychological symptoms at baseline was associated with the greatest symptom reductions b=−0.54 (95% CI –0.62 to –0.46), whereas physical symptoms at baseline were associated with the smallest effect on symptom reductions b=−0.42 (95% CI –0.5 to –0.34).

Figure 2 shows the point estimates of the effects of predictors on symptom change scores from baseline. CIs are wide within the weekly engagement groups, suggesting high variability in symptom scores. The forest plot demonstrates the linear association between weeks engaged and reduced symptoms.

Figure 2.

Correlation forest plot depicting effects of all model predictors on symptom changes. HRT, hormone replacement therapy.

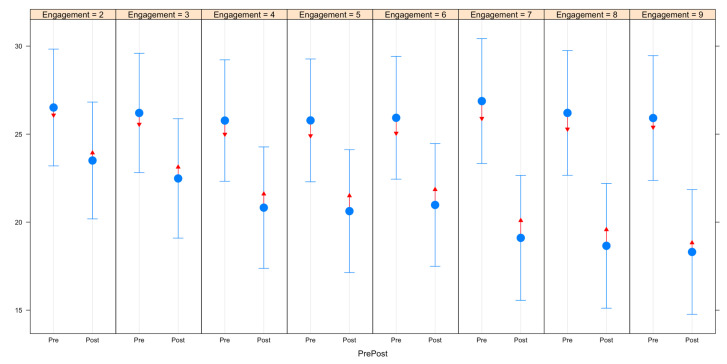

Pairwise comparisons

Figure 3 demonstrates the differences in symptoms before and after 2 months of app use according to number of weeks women engaged with the app. Within each of the engagement groups, there were statistically significant reductions in symptoms after 2 months, indicated by the lack of overlap between the red comparison arrows. As total number of engagement weeks increased, reductions in symptoms after 2 months of app use became larger.

Figure 3.

Pairwise comparisons of pre/post variances in symptom scores by number of weeks engaged.

Discussion

These findings demonstrate that use of the Health & Her app for 2 months was associated with reduced menopausal symptoms. Moreover, women who engaged with the app more frequently across the 2-month period reported greater reductions in symptoms than women who engaged for fewer weeks. These findings remained significant after controlling for covariates such as HRT use, hormonal contraceptive use, supplement use, age and current comorbidities.

Although symptoms significantly decreased regardless of the number of weeks women engaged with the app, the more women engaged with the app the greater their reductions in symptoms. Notably, women who engaged more with the app reported more use of the app’s features, suggesting that improvements could be attributed to greater combined utilisation of the app’s facilities such as logging periods, triggers, in-app activities and monitoring symptoms. The total number of days spent monitoring symptoms independently predicted symptom reductions. This is in-line with prior research which has demonstrated that symptom monitoring can result in reductions in menopausal symptoms.5 6 However, combined weekly engagement with the app was associated with greater reductions in symptoms than symptom monitoring alone, suggesting that using multiple facets of the Health & Her app can bestow greater benefits to the user.

Logging symptom triggers via the app was associated with increased symptoms. This was an expected outcome, given that symptom triggers act as a measure of experiences and behaviour. For example, triggers include alcohol, stress at work and smoking, and these factors can all negatively influence symptoms.15 However, given that trigger reporting increased as app engagement increased, it is likely that combining trigger logging with the other facets of the app (logging symptoms, logging periods, using in-app activities, etc) contributed to improvements over time because women noted the links between their symptom triggers and symptom outcomes.

As with prior research,4 completion of in-app activities was significantly associated with reduced symptoms. It is possible that use of activities had a larger impact on symptoms than shown in the present study, as women may have completed activities through notification prompts (eg, drink water reminders, pelvic floor exercises), foregoing the need to access the app to complete and record their activity completion. This would explain why low engagers reported statistically significant reductions in symptoms after 2 months.

Logging periods was also associated with symptom reductions, which supports Zhaunova et al’s3 findings. This could suggest that women in the early stage of perimenopause, and therefore, still experiencing regular periods, might experience greater benefits from the app than postmenopausal women. Furthermore, women who engaged less with the app were older than more frequent users.

Of the four symptom domains evaluated, reporting psychological symptoms at baseline was associated with the greatest reductions in symptom scores. This outcome is supported by Andrews et al’s6 randomised trial, which demonstrated that daily symptom monitoring was associated with reductions in anxiety, brain fog, low energy and poor concentration, all of which were assessed as psychological symptoms in the present study.

The most frequent symptoms among this sample included low energy, low mood, and stress and anxiety. These symptoms are highly prevalent symptoms of perimenopause and menopause,2 and evidence suggests that individuals living with psychological symptoms are highly drawn to self-help methods such as apps to find solutions to their distress.16

Furthermore, as HRT is not indicated for improving psychological symptoms, this finding may provide support for using the Health & Her app as an adjunct to HRT.2

A notable outcome was that Health & Her brand supplement use was associated with symptom reductions. The improvements may have been related to the beneficial impact of taking the supplements. Vitamin D supplementation, a key ingredient of Health & Her’s supplements, has been demonstrated among menopausal women.17 Alternatively, this outcome may be related to placebo effects, as individuals who had recently started taking Health & Her supplements may have had a positive expectation that the supplement will lead to better health outcomes, and these expectations may have manifested as self-reported health improvements.18

Strengths, limitations and future directions

A key strength of this study was that it used a large participant sample (N=1900) of women with menopausal symptoms, improving the external validity of these findings. The present study showed clear evidence that increased engagement in the Health & Her app was associated with improved symptoms, as established by analyses which controlled for multiple factors known to influence symptoms during menopause, and random variances within individual app users. The outcome measure of self-reported symptoms is another strength because it is easy to obtain, inexpensive, and easily analysed through observation. However, there are limitations with collecting information through self-report. Subjective reports of menopausal symptoms have been known to vary from objective measures.19 In particular, subjective measures of hot flushes are more susceptible to placebo effects.20

Moreover, this study is vulnerable to sampling bias, as to be eligible for inclusion participants were required to have access to a smartphone device in order to engage with the app. However, given that 80% of women in the UK own a smartphone, this is unlikely to have a large impact on the generalisability of this data.21

Another limitation was the observational design, which restricted the data to that which participants chose to input into the app. Therefore, this study is at risk of confounding from unmeasured factors as it was also not possible to determine whether participants had any characteristics that were not captured by the app, that is, impact of notifications which remind users to engage in positive health behaviours, reading in-app health articles, recent medical help seeking, use of medications not listed by the app, comorbidities not listed by the app or ethnicity and other demographic variables. Furthermore, users with fewer or less severe symptoms may not have continued engaging with the app for the 2-month period as they may have decided that their symptoms were not worrying and were, therefore, not motivated to continue observing them. Therefore, a key future direction would be to conduct a controlled study assessing app use with clear parameters in terms of adherence to app usage, and characteristics such as age, menopausal symptoms and menopausal status.

It would also be useful to observe a longer-term study of app engagement, comparing participants with predominantly physical and psychological symptoms, with a postsurvey of app users who stopped engaging with the app to give a clearer, more sustained estimate of the effect. This will enable us to identify predictors of engagement with the Health & Her app. However, given that statistical differences were found in the present study, in the directions expected, this suggests that the benefits of using the Health & Her app to manage symptoms during the menopause transition are robust.

Additionally, because the present sample predominantly reported psychological symptoms, and these types of symptoms were associated with larger improvements than the other symptom domains (eg, physical, urogenital and sexual, vasomotor and sleep), this might suggest that app usage is most effective for women with these symptom characteristics. Moreover, these results may suggest that those with psychological symptoms are more likely to seek out apps than those who are less impacted by such symptoms, and these women may benefit more from app use. Therefore, future research should further investigate the impact of Health & Her app usage on women reporting specific symptom types to evaluate these outcomes.

The improvements in psychological symptoms could be related to the Health & Her app providing women with several activities designed to alleviate stress and psychological symptoms (ie, digital CBT exercise for low mood, deep breathing exercises and a stress and anxiety mediation exercise), as well as content designed to empower women during menopause. Notably, research examining therapeutic exercises such as paced respiration22 and meditation23 outside of app modalities have demonstrated positive effects on menopausal symptoms. While out of scope for the present study, subsequent research assessing the Health & Her app will aim to examine the impact of individual activities on symptom reductions.

Health & Her supplement usage was associated with reductions in symptoms. This may suggest that app usage enhanced the effects of taking supplements or vice versa, as women tracked their symptom changes and recognised the improvements which in turn further encouraged them to engage with the app. However, without conducting a randomised controlled trail, it is not possible to rule out the potential for a placebo effect. Thus, further research is needed to establish the impact of using the app as an adjunct to menopause-specific treatments.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that use of Health & Her’s app for a 2-month period was associated with symptom reductions among 1900 app users. Given the large sample size, this suggests these findings are generalisable to menopausal women. Moreover, greater weekly engagement with the app was associated with greater reductions in symptoms. These results support previous findings which have suggested that symptom monitoring and use of digital tools which facilitate period logging, and health-promoting digital activities can be beneficial for improving health outcomes, especially relating to psychological complaints.3–6 However, these findings are limited by the observational study design. Therefore, future research should conduct a fully controlled study to further understand the effects of using the Health & Her app to improve health during menopause, with a focus on exploring the app as an adjunct to menopause-specific treatments.

This study contributes to evidence that suggests monitoring and appraising symptoms can result in increased engagement in women who likely want to reduce their menopausal symptom prevalence and severity. In light of these findings, it is recommended that women be made aware of the benefits of using digital health apps by health providers treating women in need of support for menopausal symptoms, to help them manage their menopausal symptoms and track the impact of treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We the authors would like to thank Dr Rebeccah Tomlinson for providing her insights on this research using her perspective as a general practitioner and menopause specialist.

Footnotes

Twitter: @MenoScientist

Contributors: RA was responsible for conceptualising the study, analysing the data, preparing the manuscript and acting as guarantor. DL was responsible for reviewing the manuscript and consulting on the design and analyses. KB was responsible for conceptualising the study and reviewing the manuscript. ASL consulted on the study design and data analyses and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Health & Her.

Competing interests: RA is employed by Health & Her. KB is the CEO and co-founder of Health & Her. ASL is employed by Health & Her on a contractual basis. DL has received honoraria and expenses from Gedeon Richter: Preglem for expert speaker and web contributions.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. The data used in the present study are kept securely by Health & Her in accordance with GDPR guidelines, therefore, no data will be publicly shared. Any queries relating to data access can be made to: contact@healthandher.com.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the University of South Wales ethical review board under reference number: 23RA03LR. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Mishra GD, Kuh D. Health symptoms during Midlife in relation to menopausal transition: British prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012;344(feb08 1):e402. 10.1136/bmj.e402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NICE . NICE. Overview | Menopause: diagnosis and management | Guidance, Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23 [Accessed 7 Oct 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhaunova L, Bamford R, Radovic T, et al. Characterisation of self-reported improvements in education and health among users of FLO period tracking App: cross-sectional survey. Open Science Framework [Preprint] 2022. 10.31219/osf.io/vhn6x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.McCloud T, Jones R, Lewis G, et al. Effectiveness of a mobile App intervention for anxiety and depression symptoms in university students: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020;8:e15418. 10.2196/15418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews R, Hale G, John B, et al. Evaluating the effects of symptom monitoring on menopausal health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Glob Womens Health 2021;2:757706. 10.3389/fgwh.2021.757706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews RAF, John B, Lancastle D. Symptom monitoring improves physical and emotional outcomes during Menopause: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2023;30:267–74. 10.1097/GME.0000000000002144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paripoorani D, Gasteiger N, Hawley-Hague H, et al. A systematic review of Menopause Apps with an emphasis on osteoporosis. BMC Womens Health 2023;23:518. 10.1186/s12905-023-02612-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boivin J, Takefman JE. Stress level across stages of in vitro fertilization in subsequently pregnant and Nonpregnant women. Fertil Steril 1995;64:802–10. 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57858-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Team Rs . Rstudio: integrated development for R. In: RStudio, PBC. Boston, MA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, et al. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using Lme4. J Stat Softw 2015;67:1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lüdecke D, Bartel A, Schwemmer C, et al. Data visualization for statistics in social science. 2022. Available: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sjPlot [Accessed 24 Oct 2022].

- 12.Lenth R, Singmann H, Love J, et al. Emmeans: estimated marginal means, Aka least-squares means. R Package Version 2018;1:3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sjoberg DD, Curry M, Hannum M, et al. Gtsummary presentation-ready data summary and analytic result tables. Publ Online 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green P, MacLeod CJ, Nakagawa S. SIMR: an R package for power analysis of generalized linear mixed models by simulation. Methods Ecol Evol 2016;7:493–8. 10.1111/2041-210X.12504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noll P, Noll M, Zangirolami-Raimundo J, et al. Life habits of postmenopausal women: Association of Menopause symptom intensity and food consumption by degree of food processing. Maturitas 2022;156:1–11. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaveladze BT, Wasil AR, Bunyi JB, et al. User experience, engagement, and popularity in mental health Apps: secondary analysis of App Analytics and expert App reviews. JMIR Hum Factors 2022;9:e30766. 10.2196/30766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pérez-López FR, Chedraui P, Pilz S. Vitamin D supplementation after the Menopause. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2020;11:2042018820931291. 10.1177/2042018820931291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paranjpe MD, Chin AC, Paranjpe I, et al. Self-reported health without clinically measurable benefits among adult users of multivitamin and Multimineral supplements: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e039119. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan Y, Meister R, Löwe B, et al. Open-label Placebos for menopausal hot flushes: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 2020;10:20090. 10.1038/s41598-020-77255-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sievert LL. Subjective and objective measures of hot flashes. Am J Hum Biol 2013;25:573–80. 10.1002/ajhb.22415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Internet access – households and individuals, great Britain - office for National Statistics. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/bulletins/internetaccesshouseholdsandindividuals/2018#mobile-phones-or-smartphones-still-most-popular-devices-used-to-access-the-internet [Accessed 2 Nov 2023].

- 22.Fathy Fathalla Zaied N, Hassan Shamekh Taman A, Hassan Mohamed Alam T, et al. Effect of paced breathing technique on hot flashes and quality of daily life activities among surgically Menopaused women. Egyptian Journal of Health Care 2019;10:693–706. 10.21608/ejhc.2019.266502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sung M-K, Lee US, Ha NH, et al. A potential Association of meditation with menopausal symptoms and blood chemistry in healthy women. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e22048. 10.1097/MD.0000000000022048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-077185supp001.pdf (20.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. The data used in the present study are kept securely by Health & Her in accordance with GDPR guidelines, therefore, no data will be publicly shared. Any queries relating to data access can be made to: contact@healthandher.com.