Abstract

Introduction: Cardiac fibrosis is strongly induced by diabetic conditions. Both chrysin (CHR) and calixarene OTX008, a specific inhibitor of galectin 1 (Gal-1), seem able to reduce transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β)/SMAD pro-fibrotic pathways, but their use is limited to their low solubility. Therefore, we formulated a dual-action supramolecular system, combining CHR with sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin (SBECD) and OTX008 (SBECD + OTX + CHR). Here we aimed to test the anti-fibrotic effects of SBECD + OTX + CHR in hyperglycemic H9c2 cardiomyocytes and in a mouse model of chronic diabetes.

Methods: H9c2 cardiomyocytes were exposed to normal (NG, 5.5 mM) or high glucose (HG, 33 mM) for 48 h, then treated with SBECD + OTX + CHR (containing OTX008 0.75–1.25–2.5 µM) or the single compounds for 6 days. TGF-β/SMAD pathways, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs) and Gal-1 levels were assayed by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISAs) or Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Adult CD1 male mice received a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of streptozotocin (STZ) at a dosage of 102 mg/kg body weight. From the second week of diabetes, mice received 2 times/week the following i.p. treatments: OTX (5 mg/kg)-SBECD; OTX (5 mg/kg)-SBECD-CHR, SBECD-CHR, SBECD. After a 22-week period of diabetes, mice were euthanized and cardiac tissue used for tissue staining, ELISA, qRT-PCR aimed to analyse TGF-β/SMAD, extracellular matrix (ECM) components and Gal-1.

Results: In H9c2 cells exposed to HG, SBECD + OTX + CHR significantly ameliorated the damaged morphology and reduced TGF-β1, its receptors (TGFβR1 and TGFβR2), SMAD2/4, MAPKs and Gal-1. Accordingly, these markers were reduced also in cardiac tissue from chronic diabetes, in which an amelioration of cardiac remodeling and ECM was evident. In both settings, SBECD + OTX + CHR was the most effective treatment compared to the other ones.

Conclusion: The CHR-based supramolecular SBECD-calixarene drug delivery system, by enhancing the solubility and the bioavailability of both CHR and calixarene OTX008, and by combining their effects, showed a strong anti-fibrotic activity in rat cardiomyocytes and in cardiac tissue from mice with chronic diabetes. Also an improved cardiac tissue remodeling was evident. Therefore, new drug delivery system, which could be considered as a novel putative therapeutic strategy for the treatment of diabetes-induced cardiac fibrosis.

Keywords: chrysin, cyclodextrin, calixarene, drug delivery system, cardiac fibrosis, chronic diabetes

1 Introduction

Cardiac fibrosis is a prominent outcome in heart-related disorders, exhibited by various cardiac regions (Tian et al., 2017; Ytrehus et al., 2018). The main cells involved in development of cardiac fibrosis are activated myofibroblasts originating from the epicardium (Tao et al., 2013), the endocardium (Wessels et al., 2012), and the cardiac neural crest (Ali et al., 2014a). Other cells, like macrophages and endothelial cells, also participate in cardiac fibrogenesis via unique molecular pathways (Jiang et al., 2021).

The activation of cardiac myofibroblasts leads to an increased deposition the extracellular matrix (ECM), which amplifies cardiac dysfunction, leads to interstitial fibrosis and can consequently cause heart failure (González et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2021). However, although cardiac fibrosis is frequently associated with myocardial infarction, it characterizes also idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertensive heart disease, and diabetic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Jellis et al., 2010; Disertori et al., 2017). Particularly, the first asymptomatic stage of diabetic cardiomyopathy is characterized by myocardial fibrosis, worsened by hyperglycaemia (Jia et al., 2018).

To this regard, Galectin 1 (Gal-1) protein has recently emerged as a promising target for treating diabetes-induced fibrosis. Indeed, it has been found upregulated in kidneys from mice with type 1 and type 2 diabetes (Kuo et al., 2020), contributing to the progression of kidney fibrosis (Liu et al., 2015). Similarly, Gal-1 increase has been shown in cardiac disorders promoted by fibrotic processes, such as heart failure and acute myocardial infarction (Talman and Ruskoaho, 2016; Seropian et al., 2018). Interestingly, the Gal-1 inhibition by OTX008 compound has been effective in counteracting the buildup of Gal-1 under high glucose conditions. Indeed, a previous study reproducing in vitro diabetic retinopathy reported a reduction of Transforming Growth Factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) in human retinal pigment epithelial cells cultured in high glucose and treated with OTX008 (Trotta et al., 2022). On another side, we previously identified the anti-fibrotic properties of another mediator, the flavonoid chrysin (CHR), tested in a rodent model of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis (Balta et al., 2015; 2018). Therefore, both OTX008 and CHR could have anti-fibrotic effects even in cardiac damage induced by high glucose levels. However, their low solubility in water could affect their in vivo administration (Dong et al., 2021; Hermenean et al., 2023).

In this context, we previously formulated a dual-action supramolecular system to improve CHR and OTX008 solubility, aiming at reducing fibrosis in chronic diabetes. Particularly, we first combined CHR with sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin (SBECD) to improve its limited solubility in water; then we integrated calixarene OTX008, known for its Gal-1 inhibitory properties, into our drug delivery system (Hermenean et al., 2023). This CHR-based supramolecular cyclodextrin-calixarene delivery system was characterized in the context of rat embryonic cardiomyocytes (H9c2) cell viability, ascertaining its safety. Therefore, it could be considered as a promising therapeutic candidate for addressing cardiac fibrosis in chronic diabetes (Hermenean et al., 2023).

To this regard, the present study aimed to explore the potential cardioprotective benefits of the novel CHR-based supramolecular cyclodextrin-calixarene delivery system, by hypothesizing an amplified anti-fibrotic efficacy due to the integration of readily soluble CHR, able to counteract fibrosis, with the selective Gal-1 inhibitor OTX008. Therefore, we investigated the effects of the new drug delivery system in hyperglycemic H9c2 cardiomyocytes and in a mouse model of chronic diabetes, by analyzing the main profibrotic pathways: TGF-β1/SMAD, able to activate myofibroblasts and to increase fibrotic genes, along with ECM deposition (Ma et al., 2018; Saadat et al., 2021); p38, which mediates SMAD-independent TGF-β responses leading to cardiac remodeling, ECM deposition and metalloproteinases (MMPs) modulation (Turner and Blythe, 2019); Erk1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), contributing to cardiac fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy (Xu et al., 2016).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

OTX008 (Calixarene 0118) was purchased from Selleck Chemicals GmbH, while CHR (5,7-Dihydroxyflavone) from Alfa Aesar (by ThermoFisher Scientific, Kandel, Germany). Sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin sodium salt (SBECD) (DS∼6) was produced by Cyclolab Ltd. (Budapest, Hungary).

The experimental methods used to obtain the novel CHR complex in OTX-SBECD have been previously detailed and established (Hermenean et al., 2023). Comprehensive phase-solubility evaluations elucidated the mechanisms behind solubility augmentation and complexation. Molecular associations within the cyclodextrin-calixarene-CHR ternary system were assessed via dynamic light-scattering, as well as nuclear magnetic resonance, differential scanning calorimetry, and computational studies, as documented by Hermenean et al. (2023).

2.2 In vitro setting

As previously described (Hermenean et al., 2023), embryonic rat cardiac H9c2 (2-1) cells (ECACC, United Kingdom) were cultured at 37°C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2, in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Aurogene, Italy). This growth medium contained 5.5 mM D-glucose, 1% L-Glutamine (L-Glu; AU-X0550 Aurogene, Italy), 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; AU-S181H Aurogene, Italy) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) solution (AU-L0022 Aurogene, Italy). H9c2 cells were seeded at a specific density for each assay before being exposed to NG, high glucose (HG; 33 mM D-glucose) or NG + 27.5 mM mannitol (M; as osmotic control) for 48 h (Hermenean et al., 2023). Cells were then treated in NG or HG medium for 6 days (Hermenean et al., 2023) with the following substances:

- CHR 0.399 mg/mL dissolved in NaCl (CHR);

- SBECD 7.3 m/m% dissolved in NaCl (SBECD);

- SBECD + 0.095 mg/mL CHR dissolved in NaCl (SBECD + CHR);

- as vehicle for OTX008, dimethyl sulfoxide 2.5% (DMSO);

- OTX008 (0.75–1.25–2.50 µM);

- SBECD-OTX008 (2.5–1.25–0.75 µM) dissolved in NaCl (SBECD + OTX);

- SBECD-OTX008 (2.5–1.25–0.75 µM)-CHR dissolved in NaCl (SBECD + OTX + CHR).

Three independent experiments were done, each performed in triplicates (N = 3). Cell morphology was observed at the optical microscope.

2.2.1 RNA isolation and real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

H9c2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well) (Liu et al., 2020), exposed to NG or HG medium for 48 h and then treated for 6 days as previously described. Total RNA was purified from H9c2 lysates with an appropriate isolation kit (217004 Qiagen, Italy). RNA concentration and purity was determined by using the NanoDrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Italy). Genomic DNA (gDNA) contaminations were eliminated from RNA samples before the Reverse Transcription (RT) step, carried out on the Gene AMP PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Italy) by using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (205311 Qiagen, Italy), according to the protocol “Reverse Transcription with Elimination of Genomic DNA for Quantitative, Real-Time PCR.” The final step for Real Time PCR (qPCR) analysis was carried out in triplicate on the CFX96 Real-time System C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler (Biorad, Italy). This was performed according to the protocol “Two-Step RT-PCR (Standard Protocol),” by using the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (204143 Qiagen, Italy) and specific QuantiTect Primer Assays (249900 Qiagen, Italy) for TGF-β1 (QT00187796 Qiagen, Italy), TGFβ receptor 1 (TGFβR1; QT00190953 Qiagen, Italy), TGFβ receptor 2 (TGFβR2; QT00182315 Qiagen, Italy), Erk1 (or MAPK3—QT00176330 Qiagen, Italy) and Erk2 (or MAPK1—QT00190379 Qiagen, Italy) genes. Relative quantization of gene expression was performed by using the 2^−ΔΔCt method, by using rat Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; QT01082004 Qiagen, Italy) as housekeeping control gene.

2.2.2 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs)

Cell-biased ELISA assays were performed to analyze the cellular levels of rat p38 MAPK (phosphorylated/total) (CBEL-P38-1 RayBiotech, GA, United States), Smad2 (LS-F1057-1 LSBio, MA, United States) and Smad4 (LS-F2315-1 LSBio, MA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Competitive ELISA test was used to quantify the cellular levels of Gal-1 (abx256936 abbexa, United Kingdom), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3 Animals and experimental protocol

Animal experimental procedures were approved by the Ethical Commettee of Vasile Goldis Western University of Arad (Approval number 20, 12/06/2020) and the National Sanitary Veterinary and Food Safety Authority (Certificate number 001/04.02.2021) and were performed according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, in compliance with European and national guidelines for research on laboratory animals.

Adult CD1 male mice sourced from the Animal facility of the “Vasile Goldiș” Western University of Arad served as the experimental subjects. These animals were maintained under standardized housing conditions, in compliance with both national and European standards and guidelines. Diabetes was elicited in mice via a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of streptozotocin (STZ) at a dosage of 102 mg/kg body weight. The STZ was freshly prepared in a 50 mM citrate buffer solution (pH 4.5). Post 2 weeks of the STZ administration, fasting blood glucose levels were ascertained. Mice registering blood glucose concentrations exceeding 200 mg/dL were categorized as diabetic and were maintained for a duration of 20 weeks prior to initiating interventions. Post the 20-week period, the chronic diabetic mice, coupled with 10 age-matched healthy counterparts, were randomly assigned into seven distinct groups (N = 10 per group):

- Group 1 (Control): Healthy mice serving as the baseline control.

- Group 2 (Diabetes): Chronic diabetic mice, which were euthanized following the 22-week period.

- Group 3 (OTX-SBECD): Chronic diabetic mice at 20 weeks, administered with 5 mg/kg of OTX complexed with SBECD

- Group 4 (OTX-SBECD-CHR): Chronic diabetic mice at 20 weeks, given 5 mg/kg of OTX complexed with SBECD, along with chrysin.

- Group 5 (SBECD-CHR): Chronic diabetic mice at 20 weeks, treated with CHR complexed with SBECD.

- Group 6 (SBECD): Chronic diabetic mice at 20 weeks, receiving the uncomplexed SBECD.

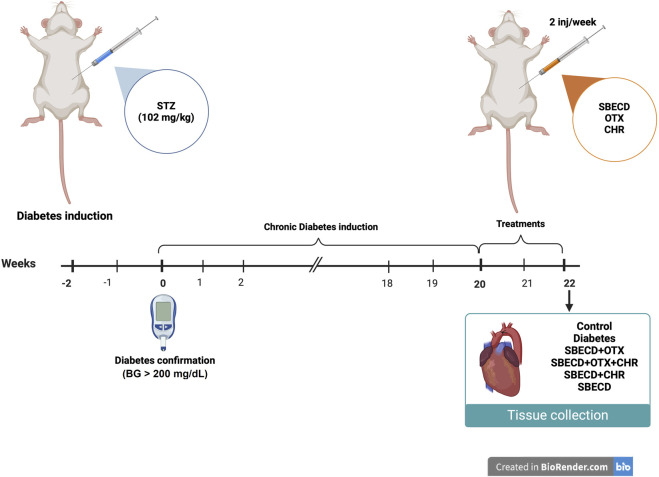

After 20 weeks of chronic diabetes, treatments were administered 2 times/week for 2 weeks by i.p. injections. Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the experimental protocol.

FIGURE 1.

In vivo experimental design. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

2.3.1 Histology

Cardiac specimens were promptly fixed using a 4% paraformaldehyde solution buffered in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and subsequently embedded in paraffin for processing. Following this, tissue sections were stained with Gomori’s trichrome using the stain kit (38016SS1 Leica, United States). The entire staining procedure adhered closely to the guidelines specified by the Bio-Optica staining kit (Italy). Once stained, the histological slides were examined under an Olympus BX43 microscope (Germany). High-resolution images of the representative sections were captured for documentation and detailed analysis using an Olympus XC30 digital camera (Germany).

2.3.2 Immunohistochemistry

Prior to undertaking immunohistochemistry, heart sections, embedded in paraffin and measuring 5 µm in thickness, underwent deparaffinization and rehydration through established techniques. For antigen detection, sections were treated with primary antibodies—rabbit polyclonal TGF-β1 (sc-146 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX, United States), Smad2/3 (sc-133098 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX, United States), and α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA, ab32575 abcam, United Kingdom), all at a 1:200 dilution. This was followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C. The Novocastra Peroxidase/DAB kit (Leica Biosystems, Germany) was then employed, consistent with the manufacturer’s directives, to visualize the immunoreactions. For negative controls, primary antibodies were substituted with irrelevant immunoglobulins of the same isotype, and the specimens were observed under bright-field microscopy. Quantitative analysis was performed by determining the ratio of the positively stained area to the total section area using the Image J software.

2.3.3 In vivo qRT-PCR evaluations

qRT-PCR was performed to evaluate the mRNA expression levels of TGF-β1, Smad 2/3, Smad 7, Collagen I (Col I), αSMA, MMPs and TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (TIMP1). The extraction of total RNA was facilitated using the SV Total RNA isolation kit (Promega, Italy). Following extraction, the integrity and concentration of the RNA samples were gauged via a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, MA, United States). Subsequently, reverse transcription of the RNA was carried out employing the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, MA, United States). The Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Life Technologies, CA, United States) was utilized for the RT-PCR, executed on an Mx3000PTM RT-PCR system (Agilent, CA, United States). Every sample underwent triplicate runs for accuracy. Detailed primer sequences are presented in Table 1. Serving as a reference gene, the expression of GAPDH was also gauged, following the identical experimental guidelines. The relative shifts in gene expression were ascertained employing the 2^−ΔΔCt methodology, as documented in reference (Jiang et al., 2021).

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences for in vivo RT-PCR.

| Target | Sense | Antisense |

|---|---|---|

| TGF-β1 | 5′ TTTGGAGCCTGGACACACAGTAC 3′ | 5′ TGTGTTGGTTGTAGAGGGCAAGGA 3′ |

| α-SMA | 5′ CCGACCGAATGCAGAAG GA 3′ | 5′ ACAGAGTATTTGCGCTCCGAA 3′ |

| Smad 2 | 5′ GTTCCTGCCTTTGCTGAGAC 3′ | 5′ TCTCTTTGCCAGGAATGCTT 3′ |

| Smad 3 | 5′ TGCTGGTGACTGGATAGCAG 3′ | 5′ CTCCTTGGAAGGTGCTGAAG 3′ |

| Smad 7 | 5′ GCTCACGCACTCGGTGCTCA 3′ | 5′ CCAGGCTCCAGAAGAAGTTG 3′ |

| Col I | 5′ CAGCCGCTTCACCTACAGC 3′ | 5′ TTTTGTATTCAATCACTGTCTTGCC 3′ |

| MMP1 | 5′ GCAGCGTCAAGTTTAACTGGAA 3′ | 5′AACTACATTTAGGGGAGAGGTGT 3′ |

| MMP2 | 5′ CAG GGA ATG AGT ACT GGG TCT ATT 3′ | 5′ ACT CCA GTT AAA GGC AGC ATC TAC 3′ |

| MMP3 | 5′ ACCAACCTATTCCTGGTTGCTGCT 3′ | 5′ ATGGAAACGGGACAAGTCTGTGGA 3′ |

| MMP9 | 5′ AAT CTC TTC TAG AGA CTG GGA AGG AG 3′ | 5′ AGC TGA TTG ACT AAA GTA GCT GGA 3′ |

| Timp1 | 5′ GGTGTGCACAGTGTTTCCCTGTTT 3′ | 5′TCCGTCCACAAACAGTGAGTGTCA 3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′ CGACTTCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTCC-3′ | 5′ TGGGTGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTACTCCTT 3′ |

2.3.4 Determination of Gal-1 protein levels

Gal-1 protein levels were assessed in mice cardiac tissues by ELISA assay (EM1051 FineTest, China), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.4.0. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed by employing one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Bonferroni correction. The strength of association between 2 factors was assessed by Pearson correlation analysis, by determining Pearson correlation coefficient (r). For both ANOVA and Pearson correlation analysis, a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

3 Results

3.1 CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system ameliorates the damaged morphology in H9c2 cells exposed to high glucose

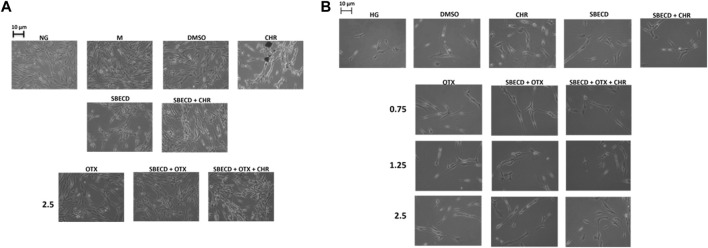

In normal glucose (NG) condition, the physiological elongated morphology exhibited by H9c2 cells was not affected by the treatments with OTX (2.5 µM) alone or combined with SBECD/SBECD + CHR (Figure 2A). H9c2 morphology was not altered also by the single treatments with CHR, SBECD, SBECD + CHR, DMSO or mannitol (M) (Figure 2A). This was in accordance with our previous data showing a normal viability of these cardiomyocytes in normal glucose when treated with the same compounds (Hermenean et al., 2023). Conversely, H9c2 exposed to high glucose (HG) evidenced a markedly reduced cell viability (Hermenean et al., 2023) and were less elongated, showing a shrunken shape and hypertrophy (Figure 2B). In HG, the treatments with CHR, SBECD and SBECD + CHR did not alter cell viability (Hermenean et al., 2023) and partially recovered the H9c2 damaged cell morphology. This was markedly ameliorated by OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM) alone or in the different formulations with SBECD/SBECD + CHR (Figure 2B), accordingly with the higher increase in cell viability showed by SBECD + OTX and SBECD + OTX + CHR (2.5 µM) (Hermenean et al., 2023).

FIGURE 2.

CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system preserved H9c2 morphology in high glucose. (A) Representative optic microscope observations of H9c2 cells cultured in normal glucose (NG) for 48 h and exposed for 6 days to the highest dose (2.5 µM) of OTX008 alone or in the different combinations considered, or (B) cultured in high glucose (HG) for 48 h and treated for 6 days with 3 doses (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM) of OTX008 alone or in the different combinations considered. Magnification = ×20; scale bar = 10 µm. N = 3 per group (three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate). NG: 5.5 mM D-glucose; M: NG + 27.5 mM mannitol; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide 2.5%; CHR: 5,7-Dihydroxyflavone 0.399 mg/mL; SBECD: Sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin sodium salt 7.3 m/m%; SBECD + CHR: SBECD + 0.095 mg/mL CHR; OTX: calixarene OTX008—Calixarene 0118—(0.75–1.25–2.5): OTX008 (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX: SBECD-OTX008 (2.5–1.25–0.75 µM); SBECD + OTX + CHR: SBECD-OTX008 (2.5–1.25–0.75 µM)-CHR; HG: 33 mM D-glucose.

3.2 CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system reduces the pro-fibrotic pathways in H9c2 cells exposed to high glucose

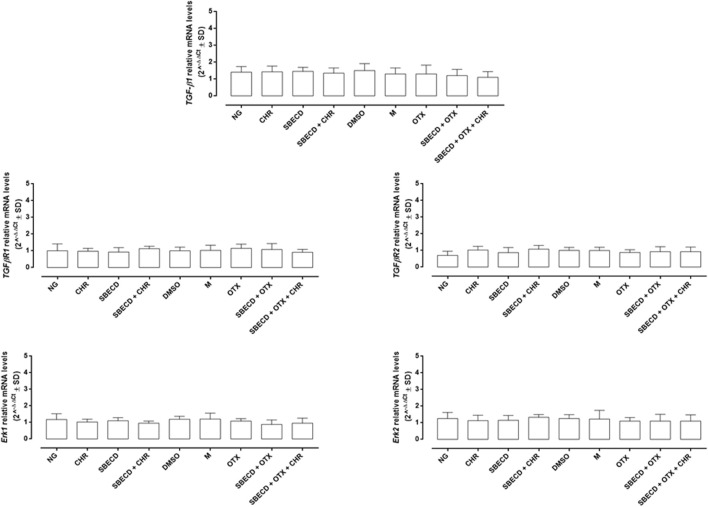

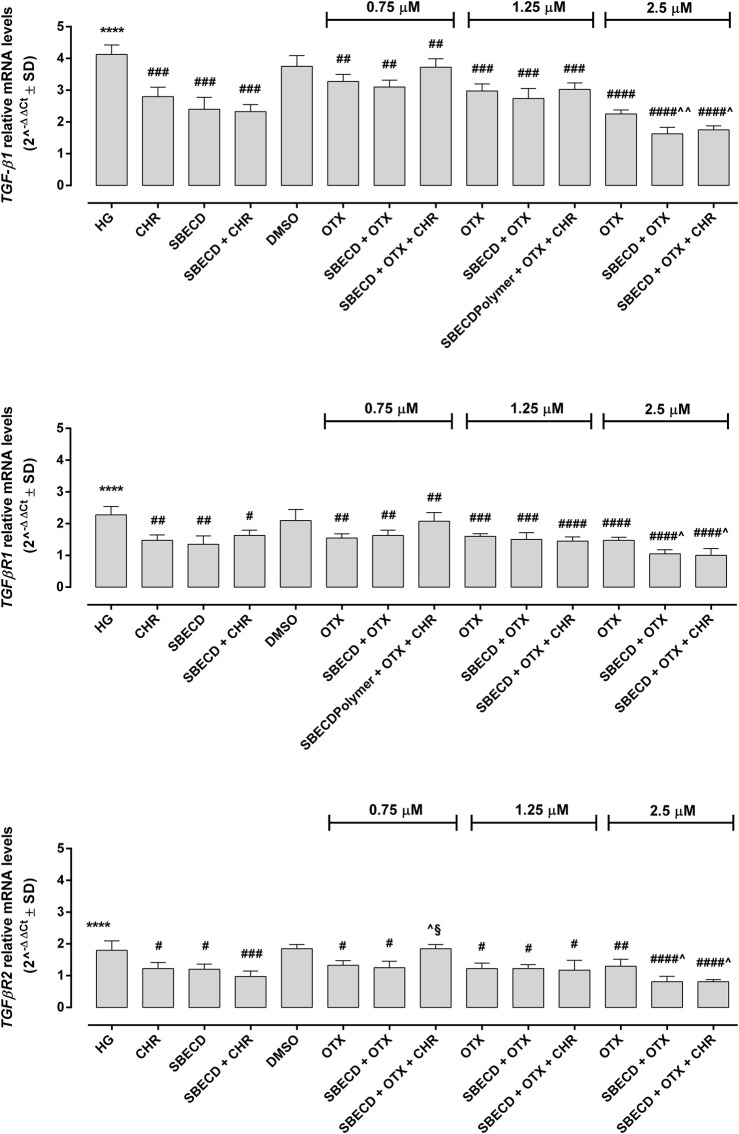

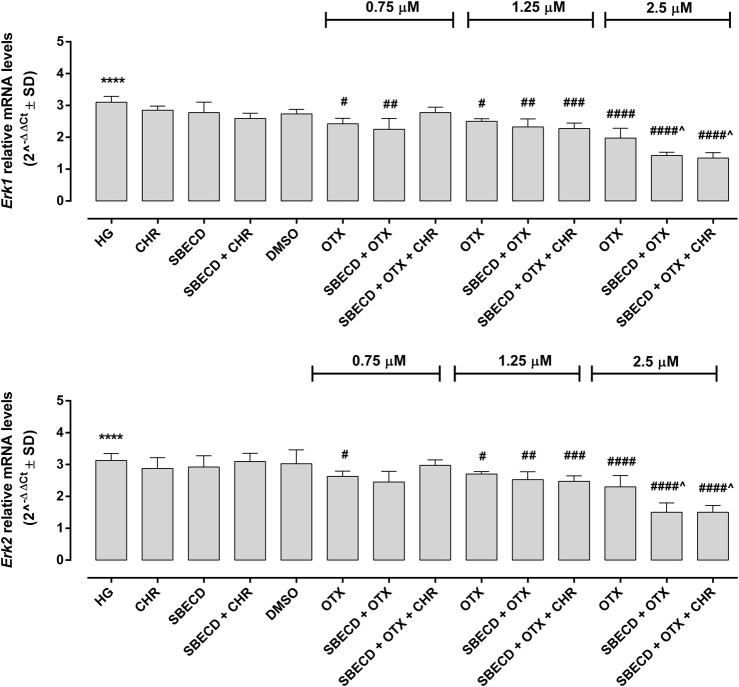

The main pro-fibrotic pathways, the canonical (involving TGF-β1, TGFβR1/2, Smad2/4) and non-canonical one (involving p38, Erk1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinases) were not altered in H9c2 cells cultured in normal glucose and exposed to the different treatments (Figure 3; Table 2). Conversely, HG exposure significantly increased both the pro-fibrotic pathways in H9c2 cells (p < 0.0001 vs. NG) (Figures 4, 5; Table 3). Interestingly, SBECD, CHR and SBECD + CHR were able to significantly reduce TGF-β1 and TGFβR1/2 expression levels in H9c2 cells exposed to HG, but not the other pro-fibrotic targets. In HG, the three doses of OTX (0.75–1.25 and 2.5 µM) tested alone or in combination with SBECD or SBECD + CHR were able to significantly decrease the canonical and non-canonical fibrotic pathways, but only the two formulations combined with OTX 2.5 µM (SBECD + OTX 2.5 and SBECD + OTX 2.5 + CHR) were able to further decrease the pro-fibrotic pathways compared to same dose of OTX tested alone (Figures 4, 5; Table 3).

FIGURE 3.

CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system does not affect TGF-β signaling and MAPKs in H9c2 cardiomyocytes cultured in normal glucose. TGF-β1, TGFβR1, TGFβR2, Erk1 and Erk2 mRNA levels (2^−ΔΔCt ± SD) were determined by qRT-PCR, using GAPDH as gene control. N = 3 per group (three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate). NG: 5.5 mM D-glucose; M: NG + 27.5 mM mannitol; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide 2.5%; CHR: 5,7-Dihydroxyflavone 0.399 mg/mL; SBECD: Sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin sodium salt 7.3 m/m%; SBECD + CHR: SBECD + 0.095 mg/mL CHR; OTX: calixarene OTX008—Calixarene 0118—(2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX: SBECD-OTX008 (2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX + CHR: SBECD-OTX008 (2.5 µM)-CHR.

TABLE 2.

Smad2/4 and p38 protein levels in H9c2 cells cultured in normal glucose and exposed to the different treatments.

| NG | CHR | SBECD | SBECD + CHR | DMSO | M | OTX | SBECD + OTX | SBECD + OTX + CHR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smad2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

| Smad4 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| P-p38/p38 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.4 |

Smad2, Smad4 relative protein levels and P-p38/p38 MAPK ratio (optical density values at 450 nm ± SD) were determined by cell-biased ELISA. N = 3 per group (three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate). NG: 5.5 mM D-glucose; M: NG + 27.5 mM mannitol; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide 2.5%; CHR: 5,7-Dihydroxyflavone 0.399 mg/mL; SBECD: Sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin sodium salt 7.3 m/m%; SBECD + CHR: SBECD + 0.095 mg/mL CHR; OTX: calixarene OTX008—Calixarene 0118—(2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX: SBECD-OTX008 (2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX + CHR: SBECD-OTX008 (2.5 µM)-CHR.

FIGURE 4.

CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system downregulates TGF-β signaling in H9c2 cardiomyocytes exposed to high glucose. TGF-β1, TGFβR1 and TGFβR2 mRNA levels (2^−ΔΔCt ± SD) were determined by qRT-PCR, using GAPDH as gene control. N = 3 per group (three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate). HG: 33 mM D-glucose; M: NG + 27.5 mM mannitol; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide 2.5%; CHR: 5,7-Dihydroxyflavone 0.399 mg/mL; SBECD: Sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin sodium salt 7.3 m/m%; SBECD + CHR: SBECD + 0.095 mg/mL CHR; OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5): calixarene OTX008—Calixarene 0118—(0.75–1.25–2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5): SBECD-OTX008 (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5)+ CHR: SBECD-OTX008 (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM)-CHR. ****p < 0.0001 vs. NG; # p < 0.5, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 and #### p < 0.0001 vs. HG; ^ p < 0.05 and ^ ^ p < 0.01 vs. OTX; § p < 0.05 vs. SBECD + OTX (same dose).

FIGURE 5.

CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system downregulates MAPKs in H9c2 cardiomyocytes exposed to high glucose. Erk1 and Erk2 mRNA levels (2^−ΔΔCt ± SD) were determined by qRT-PCR, using GAPDH as gene control. N = 3 per group (three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate). HG: 33 mM D-glucose; M: NG + 27.5 mM mannitol; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide 2.5%; CHR: 5,7-Dihydroxyflavone 0.399 mg/mL; SBECD: Sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin sodium salt 7.3 m/m%; SBECD + CHR: SBECD + 0.095 mg/mL CHR; OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5): calixarene OTX008—Calixarene 0118—(0.75–1.25–2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5): SBECD-OTX008 (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5)+ CHR: SBECD-OTX008 (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM)-CHR. ****p < 0.0001 vs. NG; # p < 0.5, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 and #### p < 0.0001 vs. HG; ^p < 0.05 vs. OTX (same dose).

TABLE 3.

Smad2/4 and p38 protein levels in H9c2 cells cultured in high glucose and exposed to the different treatments.

| Smad2 | Smad4 | P-p38/p38 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HG | 1.9 ± 0.1**** | 2.3 ± 0.3**** | 2.5 ± 0.2**** |

| CHR | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| SBECD | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.2 |

| SBECD + CHR | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| DMSO | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 |

| OTX (0.75) | 1.4 ± 0.1 # | 1.6 ± 0.1 ## | 1.6 ± 0.1 ## |

| SBECD + OTX (0.75) | 1.3 ± 0.1 # | 1.6 ± 0.2 ## | 1.7 ± 0.1 ## |

| SBECD + OTX (0.75) + CHR | 1.9 ± 0.2 # ^ § | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| OTX (1.25) | 1.5 ± 0.1 # | 1.5 ± 0.2 #### | 1.8 ± 0.1 ### |

| SBECD + OTX (1.25) | 1.4 ± 0.1 ## | 1.3 ± 0.2 #### | 1.8 ± 0.1 #### |

| SBECD + OTX (1.25) + CHR | 1.5 ± 0.2 # | 1.7 ± 0.1 ## | 2.3 ± 0.2 ^ § |

| OTX (2.5) | 1.5 ± 0.1 ## | 1.7 ± 0.3 ## | 1.9 ± 0.1 ### |

| SBECD + OTX (2.5) | 1.1 ± 0.1 #### ^ | 1.3 ± 0.1 #### ^ ^ | 1.3 ± 0.1 #### ^ ^ |

| SBECD + OTX (2.5) + CHR | 1.1 ± 0.1 #### ^ ^ | 1.7 ± 0.1 #### ^ | 1.4 ± 0.2 #### ^ |

Smad2, Smad4 relative protein levels and P-p38/p38 MAPK ratio (optical density values at 450 nm ± SD) were determined by cell-biased ELISA. N = 3 per group (three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate). HG: 33 mM D-glucose; M: NG + 27.5 mM mannitol; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide 2.5%; CHR: 5,7-Dihydroxyflavone 0.399 mg/mL; SBECD: Sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin sodium salt 7.3 m/m%; SBECD + CHR: SBECD + 0.095 mg/mL CHR; OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5): calixarene OTX008—Calixarene 0118—(0.75–1.25–2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5): SBECD-OTX008 (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5)+ CHR: SBECD-OTX008 (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM)-CHR. ****p < 0.0001 vs. NG; # p < 0.5, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 and #### p < 0.0001 vs. HG; ^ p < 0.05 and ^ ^ p < 0.01 vs. OTX; § p < 0.05 vs. SBECD + OTX (same dose).

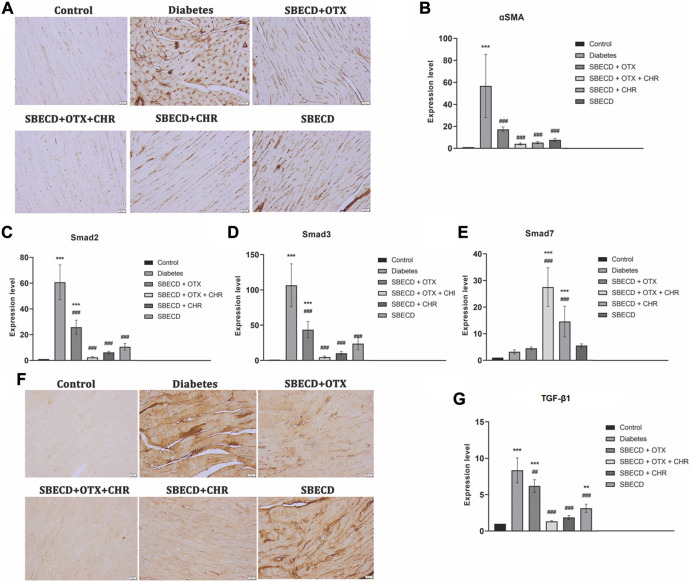

3.3 CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system downregulates the main pro-fibrotic signalling pathways in cardiac tissues

αSMA gene expression is a marker of activated myofibroblasts in tissue remodeling (Shinde et al., 2017). For the diabetes group, there was a notable increase in αSMA gene expression, as demonstrated by RT-PCR analysis, when compared to the control group (p < 0.001). All treatments resulted in significant decreases in this expression relative to the Diabetes group. Among these, the SBECD + OTX + CHR treatment yielded the most substantial decrease, as illustrated in Figure 6. Immunohistochemical studies revealed enhanced staining for the cardiac tissue samples from the Diabetes group, but this expression was almost returned to control levels after SBECD + OTX + CHR treatment.

FIGURE 6.

CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system downregulates the main pro-fibrotic signaling pathways in cardiac tissues. (A) Immunohistochemical expression of α-SMA, Scale bar: 20 μm; (B) RT-PCR analysis of α-SMA gene expression. (C) RT-PCR analysis of Smad2 gene expression; (D) RT-PCR analysis of Smad3 gene expression; (E) RT-PCR analysis of Smad7 gene expression; (F) Immunohistochemical expression of TGF-β1, Scale bar: 20 μm; (G) RT-PCR analysis of TGF-β1 gene expression. N = 10 mice per group. Control: non-diabetic mice; Diabetes: diabetic mice; SBECD: sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin; OTX: calixarene OTX008 - Calixarene 0118; CHR: 5,7-Dihydroxyflavone; ***p < 0.001 vs. Control; ### p < 0.001 and ## p < 0.01 vs. Diabetes.

TGF-β1 plays a crucial role in promoting tissue fibrosis, operating primarily via the phosphorylation of Smad 2/3. In contrast, Smad 7, a Smad inhibitor, works by downregulating Smad 2/3 and targeting the TGF-β1 receptor (Biernacka et al., 2011). In comparison to the control, chronic diabetes led to a significant increase in TGF-β1 gene expression and intense immunopositivity. Treatments with SBECD + OTX, SBECD + OTX + CHR, and SEBCD + CHR lowered TGF-β1 levels by 1.97-fold, 19.11-fold, and 6.62-fold, respectively, when compared to the Diabetes group. The same pattern was obtained for Smad2 and Smad3. In contrast, the mRNA expression of Smad7 was significantly upregulated in SBECD + OTX + CHR group by 12.7-fold compared to diabetes (Figure 6).

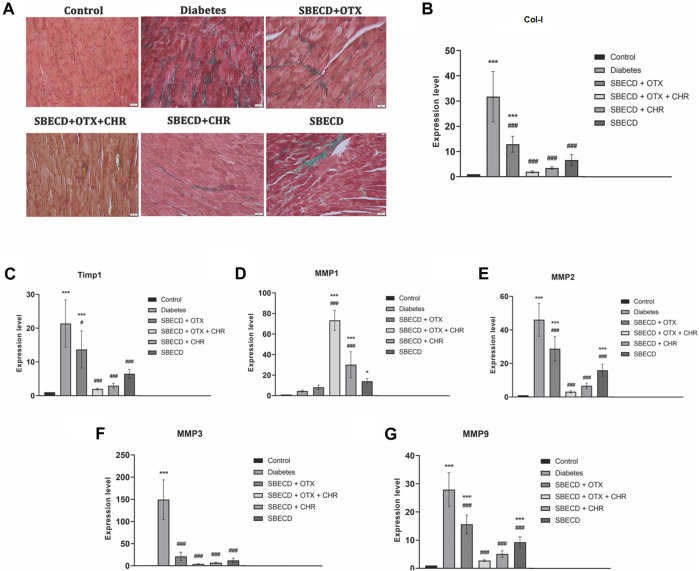

3.4 CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system suppresses the secretion and deposition of collagen in cardiac tissues

Cardiac tissue displayed an increase in collagen production and accumulation as determined by Gomori’s Trichrome staining in chronic Diabetes group (Figure 7). An RT-PCR examination revealed a significant rise in the expression of Col-1 gene in the diabetes group relative to the control group (p < 0.001). Post-treatment, there was a marked reduction in gene expression levels when compared to the diabetes group, with SBECD + OTX + CHR treatment resulting in a decrease by 23.76 times compared to diabetic animals (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system suppresses the secretion and deposition of collagen in cardiac tissues. (A) Collagen staining with Gomori’s Trichrome kit; green—collagen deposition; (B) RT-PCR analysis of Col-I gene expression; (C) RT-PCR analysis of Timp-1 gene expression; (D) RT-PCR analysis of MMP1 gene expression; (E) RT-PCR analysis of MMP2 gene expression; (F) RT-PCR analysis of MMP3 gene expression; (G) RT-PCR analysis of MMP9 gene expression. N = 10 mice per group. Control: non-diabetic mice; Diabetes: diabetic mice; SBECD: sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin; OTX: calixarene OTX008—Calixarene 0118; CHR: 5,7-Dihydroxyflavone; ***p < 0.001 compared to control; # p < 0.05 and ### p < 0.001 vs. Diabetes.

TIMP-1 acts as a natural inhibitor, preventing MMPs from breaking down the ECM. To study how the CHR-based cyclodextrin-calixarene supramolecular system affects ECM in the fibrotic heart tissue of diabetic mice, we evaluated the mRNA levels of TIMP-1 and MMPs using RT-PCR. The results indicated that the diabetes group exhibited considerably elevated expression levels of TIMP-1, MMP-2, -3, and -9 genes when contrasted with the control group (p < 0.001). The applied treatments effectively reduced these mRNA expressions compared to the diabetes group (p < 0.001). However, MMP-1 mRNA expression was notably increased following the treatments relative to the diabetes group (p < 0.001). Specifically, in the SBECD + OTX + CHR treatment group, TIMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, and MMP-9 expressions dropped approximately by about 29.04, 15.12, 58.77, and 19.41 times, respectively, compared to the diabetes group. Conversely, MMP-1 gene expression raised significantly after treatment with SBECD + OTX + CHR compared to diabetes (p < 0.001) (Figure 7).

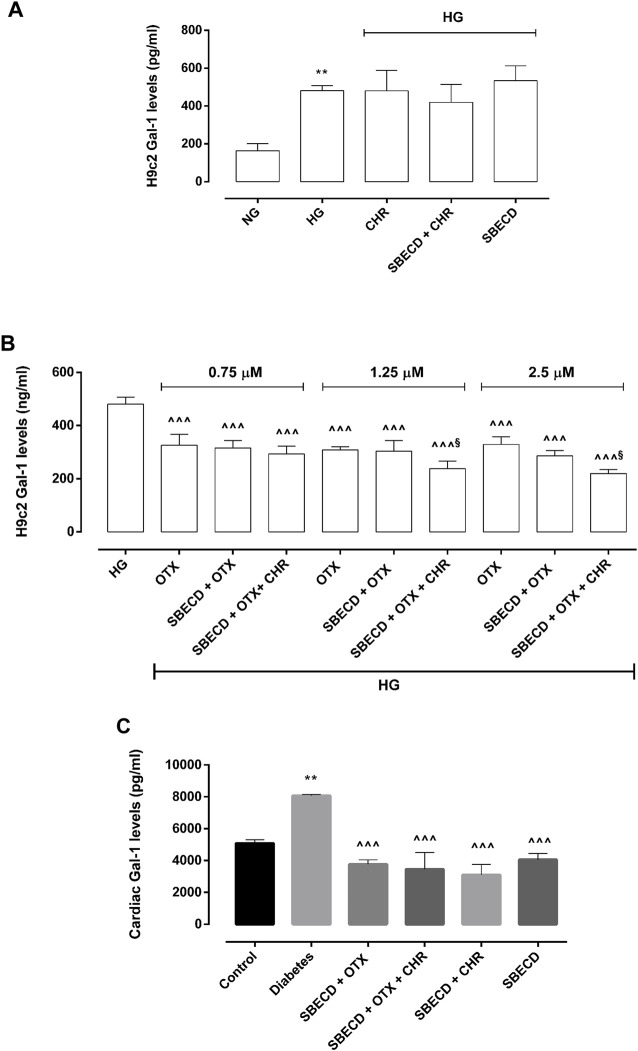

3.5 CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system modulates Gal-1 levels in H9c2 cells and in cardiac tissues

Gal-1 protein levels were significantly elevated in H9c2 cells exposed to HG (481 ± 26 pg/mL, p < 0.01 vs NG) compared to control group (163 ± 38 pg/mL) and were not significantly modulated by CHR (480 ± 108 pg/mL), SBECD + CHR (420 ± 96 pg/mL) and SBECD (534 ± 79 pg/mL) in hyperglycaemic conditions (Figure 7A). All the doses of OTX (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM) alone or in combination with SBECD or SBECD + CHR were able to significantly downregulate Gal-1 protein levels (p < 0.001) in H9c2 cells exposed to high glucose (Figure 8B). Moreover, at the doses of 1.25 and 2.5 µM, SBECD + OTX + CHR further reduced Gal-1 protein levels in H9c2 cells compared to OTX at the same doses (p < 0.05) (Figure 8B).

FIGURE 8.

CHR-based supramolecular drug delivery system reduces Gal-1 in H9c2 cells exposed to high glucose and in cardiac tissues. (A) Gal-1 protein levels (pg/mL ± SD), determined by ELISA, in H9c2 cells cultured in normal glucose (NG) or high glucose (HG) for 48 h and exposed to CHR, SBECD + CHR and SBECD for 6 days in HG; (B) Gal-1 protein levels (pg/mL ± SD) in H9c2 cells cultured in HG for 48 h and treated with OTX008 (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM) alone or combined with SBECD/SBECD + CHR; N = 3 per group (three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate). NG: 5.5 mM D-glucose; HG: 33 mM D-glucose; CHR: 5,7-Dihydroxyflavone 0.399 mg/mL; SBECD: Sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin sodium salt 7.3 m/m%; SBECD + CHR: SBECD + 0.095 mg/mL CHR; OTX: calixarene OTX008—Calixarene 0118—(0.75–1.25–2.5): OTX008 (0.75–1.25–2.5 µM); SBECD + OTX: SBECD-OTX008 (2.5–1.25–0.75 µM); SBECD + OTX + CHR: SBECD-OTX008 (2.5–1.25–0.75 µM)-CHR; **p < 0.01 vs. NG; ^ ^ ^ p < 0.001 vs. HG; § p < 0.05 vs. OTX; (C) Gal-1 protein levels (pg/mL ± SD) determined by ELISA in cardiac tissues. N = 10 mice per group. Control: non-diabetic mice; Diabetes: diabetic mice; SBECD: sulfobutylated β-cyclodextrin; OTX: calixarene OTX008—Calixarene 0118; CHR: 5,7-Dihydroxyflavone. **p < 0.01 vs. Control; ^ ^ ^ p < 0.001 vs. Diabetes.

Consistent with the in vitro findings, after 22 weeks of hyperglycaemia, the cardiac Gal-1 protein levels in chronic diabetes animals showed a significant rise (8,068 ± 71 pg/mL, p < 0.01 vs. Control). In contrast, non-diabetic mice exhibited levels of 5,075 ± 233 pg/mL. After 2 weeks of treatments, there was a significant decrease in its levels (p < 0.001) (Figure 8C).

4 Discussion

Cardiac fibrosis is a defining feature of diabetic cardiomyopathy. This condition is marked by the accumulation of ECM proteins in the cardiac interstitium, leading to perivascular fibrosis and left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, which frequently results in heart failure (Russo and Frangogiannis, 2016; Jia et al., 2018).

Hyperglycaemia or diabetes has been widely documented to impact the development of cardiac fibrosis, both in preclinical and clinical scenarios. Specifically, rodent models mimicking type I and type II diabetes exhibited a marked cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis, accompanied by the increase of pro-fibrotic genes (Ares-Carrasco et al., 2009; Huynh et al., 2010; 2012; Li et al., 2010; Biernacka et al., 2011; Gonzalez-Quesada et al., 2013; Hao et al., 2015). Similarly, diabetic patients showed extensive interstitial, perivascular and replacement fibrosis (Regan et al., 1977; Kwong et al., 2008; Turkbey et al., 2011), coupled with capillary basement membrane thickening, type I and III collagen accumulation and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (Fischer et al., 1984; Nunoda et al., 1985; Sutherland et al., 1989; Van Hoeven and Factor, 1990; Shimizu et al., 1993; Kawaguchi et al., 1997; Van Heerebeek et al., 2008; Falcão-Pires et al., 2011). These changes are underlined by the activation of TGF-β pathway following hyperglycaemia (Shamhart et al., 2014), as documented by TGF-β upregulation in the hearts of diabetic rodents exhibiting cardiac fibrosis (Carroll and Tyagi, 2005; Westermann et al., 2007; Senador et al., 2009; Abed et al., 2013).

It is well known that TGF-β isoforms play a central role in the genesis of tissue fibrosis (Biernacka et al., 2011). Specifically, TGF-β1 promotes pro-fibrotic responses in cardiomyocytes through both Smad-dependent and independent signalling (Dobaczewski et al., 2010; Biernacka et al., 2011; Rahaman et al., 2014). Indeed, TGF-β1/Smad pathway plays a crucial role in the activation of myofibroblasts, stimulation of ECM deposition through Col-I synthesis and modulation of MMP activity (Uchinaka et al., 2014; Hanna et al., 2021). On the other hand, TGF-β1 is also able to increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS), consequently activating p38 and Erk1/2 MAPKs (Sano et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2022), leading to collagen deposition in heart tissue (See et al., 2004; Johnston and Gillis, 2022). Importantly, in our prior research, we found a significant reduction in the TGF-β1/Smad pathway in a mouse model of liver fibrosis when treated with CHR (Balta et al., 2015; Balta et al., 2018). This 5,7-dihydroxyflavone was characterized by antioxidant, antitumor, anti-hypercholesterolemic and anti-inflammatory activities (Bae et al., 2011; Brechbuhl et al., 2012; Ali et al., 2014b; Anandhi et al., 2014; Samarghandian et al., 2016; Phan et al., 2021). Our data are in line with other research that identified CHR-mediated inhibition of pro-fibrotic pathways in rat myocardial injury, renal fibrosis and osteoarthritis, by reducing TGF-β1/Smad3, p38, Erk1/2, MMP2 and PERK/TXNIP/NLRP3 signalling (Rani et al., 2015; Nagavally et al., 2021; Ding et al., 2023). Additionally, by using a different pharmacological approach, we demonstrated that TGF-β/Smad pathway can be reduced in human retinal pigment epithelial cells exposed to high glucose by using calixarene OTX008, a selective inhibitor Gal-1 (Trotta et al., 2022). This particular galectin, expressed under normal and pathological conditions, plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of fibrosis (Hermenean et al., 2022) and is upregulated in heart failure and acute myocardial infarction (Talman and Ruskoaho, 2016; Seropian et al., 2018). Particularly, Gal-1 is constitutively expressed in cardiomyocytes close to sarcomeric actin, with its expression and secretion increased after cardiac injury promoted by hypoxia, inflammation and fibrosis (Seropian et al., 2018). While its early upregulation can be considered a homeostatic response to prevent cardiac remodeling induced by inflammation, prolonged Gal-1 increase could negatively influence cardiac structure and function (Ou et al., 2021). Interestingly, Gal-1 blocking/silencing by OTX008 has been shown to inhibit TGF-β in various studies, including a cell model of hypoxia-induced pulmonary fibrosis (Kathiriya et al., 2017), a mouse model of liver fibrosis (Jiang et al., 2018), dendritic cells derived from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (Kostic et al., 2021) and tumour cells (Leung et al., 2014; Koonce et al., 2017).

Worth of note, CHR and Gal-1 have roles that extend beyond influencing pro-fibrotic pathways; they also have implications in the onset and progression of diabetes. Particularly, as evidenced in preclinical studies, CHR seems to attenuate the diabetes-related tissue damage by ameliorating blood glucose levels, insulin resistance and inflammatory state in diabetic animals, by reducing Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) in preclinical models of diabetic retinopathy and by decreasing advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs), TGF-β1/Smad and Col-I deposition in diabetic hearts (Li et al., 2014; Farkhondeh et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2021a; Salama et al., 2022). This protective effect of CHR is further highlighted by its potential in improving conditions related to diabetes, such as fibrosis (Kang et al., 2023) and cardiometabolic diseases (Talebi et al., 2022). On the other hand, Gal-1 levels have been observed to be elevated in serum of diabetic patients and associated to a reduction of renal function and insulin resistance (Fryk et al., 2016; Drake et al., 2022). Its inhibition, specifically with OTX008, has been proposed in preclinical studies as a possible therapeutic target to treat diabetic renal fibrosis (Al-Obaidi et al., 2019) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (Abu El-Asrar et al., 2020; Trotta et al., 2022).

Considering their individual protective effects against diabetes-related damage, the co-administration of CHR and calixarene OTX008 presents a potential approach for addressing diabetic fibrosis. However, both CHR and OTX008 showed a lower solubility in water, affecting their bioavailability and absorption (Dong et al., 2021; Hermenean et al., 2023). Indeed, the two compounds are soluble in organic solvents, such as DMSO or dimethylformamide (DMF), which are not suitable for in vivo administration at high doses due to their hepatotoxicity (Mathew et al., 1980; Dong et al., 2021; Hermenean et al., 2023). Therefore, we previously developed a dual-action supramolecular drug delivery system, in order to have a water soluble ternary complex. A key step was enhancing CHR’s water solubility. To achieve this, CHR was combined with SBECD, a recognized cyclodextrin derivative known for its safety, polyanionic nature and excellent solubilization properties (Fenyvesi et al., 2020). Then, OTX008 was incorporated in this novel CHR-based supramolecular cyclodextrin-calixarene drug delivery system that synergistically combined cyclodextrin and calixarene. Crucially, safety tests conducted on H9c2 cardiomyocytes revealed no detrimental impacts on cell viability when exposed to this drug delivery system (Hermenean et al., 2023). Moreover, the drug delivery system not only was able to improve H9c2 cell viability in high glucose, but also surpassed the performance of OTX008 when used on its own (Hermenean et al., 2023). This highlights the potential therapeutic promise of this combined approach in diabetic fibrosis treatment.

In this study was characterized the anti-fibrotic effects of the CHR-based supramolecular cyclodextrin-calixarene drug delivery system in H9c2 cells exposed to high glucose. The system demonstrated its strongest anti-fibrotic effects, particularly when paired with the higher dose of OTX008. This lead to a significant reduction of Gal-1 levels, implying a possible modulation of cardiac inflammatory process but primarily leading to the suppression of both canonical and non-canonical profibrotic pathways, in line with previous studies (Leung et al., 2014; Kathiriya et al., 2017; Koonce et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2018; Kostic et al., 2021; Trotta et al., 2022). Of note, the inhibition of TGF-β1 and its receptors in H9c2 cardiomyocytes could attenuate the fibrotic process by reducing the TGF-β1-induced myofibroblasts activation through Smad2/3 (Yan et al., 2018). Such findings signify the drug delivery system’s ability to counteract the pathological changes instigated by high glucose in cardiomyocytes, as evidenced by the restored morphology of these cells.

Although the CHR-based supramolecular SBECD-calixarene drug delivery system showed were very similar anti-fibrotic actions compared to the combination of OTX008 with SBECD in vitro, its higher efficacy in counteracting Gal-1 and the fibrotic pathways was evident in cardiac tissues from mice developing chronic diabetes. Indeed, this dual-action supramolecular drug delivery system led to a marked downregulation of Gal-1, implying an amelioration of cardiac remodeling and inflammatory state, as well as a reduction of profibrotic pathways. To this regard, the decrement of TGF-β1/Smad2/3 pathway in hearts from mice with chronic diabetes may lead to a reduced myofibroblasts transformation and an attenuated cardiac hypertrophic response, though the inhibitions of fibrosis-mediating genes (Fiaschi et al., 2014; Khalil et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2018). Also the increase in cardiac Smad7 levels observed in diabetic mice treated with the SBECD-calixarene drug delivery system could contribute to the reduction of fibrotic process, since Smad7 is a negative regulator of TGF-β signalling in heart, as well as an inhibitor of cardiac remodeling (Chen et al., 2009; Wei et al., 2013). Lastly, the reduction of p38 and Erk1/2 MAPK cardiac levels, associated to abnormal ECM deposition (Tang et al., 2007; Aguilar et al., 2014), confirmed the anti-fibrotic effects of the new drug delivery system treatment.

Along with reduced TGF-β/Smad pathway, a decrease in αSMA levels was observed in diabetic hearts treated with the new drug delivery system. This marker of activated myofibroblasts (Shinde et al., 2017) is higher in cardiomyocytes exposed to high glucose and underwent to myofibroblast conversion, followed by subsequent changes and remodeling in the extracellular matrix (Levick and Widiapradja, 2020). Accordingly, Timp1, an MMP inhibitor stimulated by high glucose levels (Mclennan et al., 2000), was reduced by the treatment with the novel drug delivery system, along with MMP2, 3 and 9 genes, which are typically elevated in diabetic disorders (Zhou et al., 2021b). Under normal physiological circumstances in the heart, MMP1 plays a crucial role in breaking down collagen types I, II, and III, as well as basement membrane proteins (Fan et al., 2012). Our research revealed a decline in MMP1 expression in cardiac tissue subjected to prolonged exposure to high glucose concentrations. This aligns with prior findings where patients with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy exhibited reduced MMP1 levels in their left ventricular myocardial tissue samples (Thomas et al., 1998). The therapeutic interventions succeeded in elevating MMP1 gene expression, thereby aiding in restoring balance to the matrix components and reverting the cardiac normal architecture. Moreover, the CHR-based supramolecular SBECD-calixarene drug delivery system was the most effective in reducing cardiac Col-I expression and tissue deposition. It is well known that fibrotic heart exhibits Col-I deposition in the cardiac interstitial space, associated with heart dysfunction, dynamic alterations and cardiac remodeling (Kong et al., 2014). Its accumulation induced by high glucose is known to be a factor in myocardial fibrosis, impaired relaxation and mitochondrial degeneration in patients with diabetic cardiomyopathy (Sakakibara et al., 2011; Levick and Widiapradja, 2020). Therefore, Col-I inhibition obtained with the new drug delivery system could be considered a novel strategic therapeutic tool to counteract cardiac fibrosis.

Overall, the CHR-based supramolecular SBECD-calixarene drug delivery system enhanced the solubility and the bioavailability of both CHR and calixarene OTX008. By combining the effects of the two drugs, it showcased a strong anti-fibrotic response in rat cardiomyocytes, as well as in cardiac tissue from mice with chronic diabetes. These evidenced also an improved cardiac tissue remodeling after the treatment with the dual-action supramolecular drug delivery system, which could be considered as a novel putative therapeutic strategy for the treatment of diabetes-induced cardiac fibrosis.

Funding Statement

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by a grant of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, CNCS/CCCDI—UEFISCDI, project number PN-III-P4-ID-PCE-2020-1772, within PNCDI III.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Ethical Commettee of Vasile Goldis Western University of Arad (Approval number 20, 12/06/2020) and National Sanitary Veterinary and Food Safety Authority (Certificate number 001/04.02.2021). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MT: Conceptualization, Writing–original draft. HH: Conceptualization, Writing–original draft. AC: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. BM: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. MRo: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. CL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. MRu: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. IB: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. FF: Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. RM: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing–review and editing. AH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. CB: Writing–review and editing. MD’A: Writing–review and editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Abed H. S., Samuel C. S., Lau D. H., Kelly D. J., Royce S. G., Alasady M., et al. (2013). Obesity results in progressive atrial structural and electrical remodeling: implications for atrial fibrillation. Heart rhythm. 10, 90–100. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.08.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu El‐Asrar A. M., Ahmad A., Allegaert E., Siddiquei M. M., Alam K., Gikandi P. W., et al. (2020). Galectin‐1 studies in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 98, e1–e12. 10.1111/aos.14191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar H., Fricovsky E., Ihm S., Schimke M., Maya-Ramos L., Aroonsakool N., et al. (2014). Role for high-glucose-induced protein O -GlcNAcylation in stimulating cardiac fibroblast collagen synthesis. Am. J. Physiology-Cell Physiology 306, C794–C804. 10.1152/ajpcell.00251.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N., Rashid S., Nafees S., Hasan S. K., Sultana S. (2014a). Beneficial effects of Chrysin against Methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity via attenuation of oxidative stress and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 385, 215–223. 10.1007/s11010-013-1830-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S. R., Ranjbarvaziri S., Talkhabi M., Zhao P., Subat A., Hojjat A., et al. (2014b). Developmental Heterogeneity of Cardiac Fibroblasts Does Not Predict Pathological Proliferation and Activation. Circ. Res. 115, 625–635. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Obaidi N., Mohan S., Liang S., Zhao Z., Nayak B. K., Li B., et al. (2019). Galectin‐1 is a new fibrosis protein in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. FASEB J. 33, 373–387. 10.1096/fj.201800555RR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anandhi R., Thomas P. A., Geraldine P. (2014). Evaluation of the anti-atherogenic potential of chrysin in Wistar rats. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 385, 103–113. 10.1007/s11010-013-1819-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ares-Carrasco S., Picatoste B., Benito-Martín A., Zubiri I., Sanz A. B., Sánchez-Niño M. D., et al. (2009). Myocardial fibrosis and apoptosis, but not inflammation, are present in long-term experimental diabetes. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiology 297, H2109–H2119. 10.1152/ajpheart.00157.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae Y., Lee S., Kim S.-H. (2011). Chrysin suppresses mast cell-mediated allergic inflammation: involvement of calcium, caspase-1 and nuclear factor-κB. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 254, 56–64. 10.1016/j.taap.2011.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balta C., Ciceu A., Herman H., Rosu M., Boldura O. M., Hermenean A. (2018). Dose-dependent antifibrotic effect of chrysin on Regression of liver fibrosis: the role in extracellular matrix remodeling. Dose-Response 16, 1559325818789835. 10.1177/1559325818789835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balta C., Herman H., Boldura O. M., Gasca I., Rosu M., Ardelean A., et al. (2015). Chrysin attenuates liver fibrosis and hepatic stellate cell activation through TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. Chemico-Biological Interact. 240, 94–101. 10.1016/j.cbi.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biernacka A., Dobaczewski M., Frangogiannis N. G. (2011). TGF-β signaling in fibrosis. Growth factors. 29, 196–202. 10.3109/08977194.2011.595714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechbuhl H. M., Kachadourian R., Min E., Chan D., Day B. J. (2012). Chrysin enhances doxorubicin-induced cytotoxicity in human lung epithelial cancer cell lines: the role of glutathione. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 258, 1–9. 10.1016/j.taap.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J., Tyagi S. (2005). Extracellular matrix remodeling in the heart of the Homocysteinemic obese rabbit. Am. J. Hypertens. 18, 692–698. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Chen H., Zheng D., Kuang C., Fang H., Zou B., et al. (2009). Smad7 is Required for the development and function of the heart. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 292–300. 10.1074/jbc.M807233200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L., Liao T., Yang N., Wei Y., Xing R., Wu P., et al. (2023). Chrysin ameliorates synovitis and fibrosis of osteoarthritic fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rats through PERK/TXNIP/NLRP3 signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1170243. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1170243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disertori M., Masè M., Ravelli F. (2017). Myocardial fibrosis predicts ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 27, 363–372. 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobaczewski M., Bujak M., Li N., Gonzalez-Quesada C., Mendoza L. H., Wang X.-F., et al. (2010). Smad3 signaling critically Regulates fibroblast phenotype and function in healing myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 107, 418–428. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X., Cao Y., Wang N., Wang P., Li M. (2021). Systematic study on solubility of chrysin in different organic solvents: the synergistic effect of multiple intermolecular interactions on the dissolution process. J. Mol. Liq. 325, 115180. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.115180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drake I., Fryk E., Strindberg L., Lundqvist A., Rosengren A. H., Groop L., et al. (2022). The role of circulating galectin-1 in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: evidence from cross-sectional, longitudinal and Mendelian randomisation analyses. Diabetologia 65, 128–139. 10.1007/s00125-021-05594-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcão-Pires I., Hamdani N., Borbély A., Gavina C., Schalkwijk C. G., Van Der Velden J., et al. (2011). Diabetes Mellitus Worsens Diastolic Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Aortic Stenosis Through Altered Myocardial Structure and Cardiomyocyte Stiffness. Circulation 124, 1151–1159. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.025270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan D., Takawale A., Lee J., Kassiri Z. (2012). Cardiac fibroblasts, fibrosis and extracellular matrix remodeling in heart disease. Fibrogenes. Tissue Repair 5, 15. 10.1186/1755-1536-5-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkhondeh T., Samarghandian S., Roshanravan B. (2019). Impact of chrysin on the molecular mechanisms underlying diabetic complications. J. Cell. Physiology 234, 17144–17158. 10.1002/jcp.28488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenyvesi F., Nguyen T. L. P., Haimhoffer Á., Rusznyák Á., Vasvári G., Bácskay I., et al. (2020). Cyclodextrin Complexation improves the solubility and Caco-2 Permeability of chrysin. Materials 13, 3618. 10.3390/ma13163618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiaschi T., Magherini F., Gamberi T., Lucchese G., Faggian G., Modesti A., et al. (2014). Hyperglycemia and angiotensin II cooperate to enhance collagen I deposition by cardiac fibroblasts through a ROS-STAT3-dependent mechanism. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell. Res. 1843, 2603–2610. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer V. W., Barner H. B., Larose L. S. (1984). Pathomorphologic aspects of muscular tissue in diabetes mellitus. Hum. Pathol. 15, 1127–1136. 10.1016/S0046-8177(84)80307-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryk E., Sundelin J. P., Strindberg L., Pereira M. J., Federici M., Marx N., et al. (2016). Microdialysis and proteomics of subcutaneous interstitial fluid reveals increased galectin-1 in type 2 diabetes patients. Metabolism 65, 998–1006. 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González A., Schelbert E. B., Díez J., Butler J. (2018). Myocardial interstitial fibrosis in Heart Failure: Biological and Translational Perspectives. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71, 1696–1706. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Quesada C., Cavalera M., Biernacka A., Kong P., Lee D.-W., Saxena A., et al. (2013). Thrombospondin-1 Induction in the Diabetic Myocardium Stabilizes the Cardiac Matrix in Addition to Promoting Vascular Rarefaction Through Angiopoietin-2 Upregulation. Circ. Res. 113, 1331–1344. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna A., Humeres C., Frangogiannis N. G. (2021). The role of Smad signaling cascades in cardiac fibrosis. Cell. Signal. 77, 109826. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao P.-P., Yang J.-M., Zhang M.-X., Zhang K., Chen Y.-G., Zhang C., et al. (2015). Angiotensin-(1–7) treatment mitigates right ventricular fibrosis as a distinctive feature of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiology 308, H1007–H1019. 10.1152/ajpheart.00563.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermenean A., Dossi E., Hamilton A., Trotta M. C., Russo M., Lepre C. C., et al. (2023). Chrysin directing an enhanced solubility through the formation of a supramolecular cyclodextrin-calixarene drug delivery system: a potential strategy in antifibrotic diabetes therapeutics. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 10.1101/2023.10.03.560552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermenean A., Oatis D., Herman H., Ciceu A., D’Amico G., Trotta M. C. (2022). Galectin 1—a key player between tissue repair and fibrosis. IJMS 23, 5548. 10.3390/ijms23105548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh K., Kiriazis H., Du X.-J., Love J. E., Jandeleit-Dahm K. A., Forbes J. M., et al. (2012). Coenzyme Q10 attenuates diastolic dysfunction, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis in the db/db mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 55, 1544–1553. 10.1007/s00125-012-2495-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh K., McMullen J. R., Julius T. L., Tan J. W., Love J. E., Cemerlang N., et al. (2010). Cardiac-specific IGF-1 receptor Transgenic expression Protects against cardiac fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in a mouse model of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes 59, 1512–1520. 10.2337/db09-1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellis C., Martin J., Narula J., Marwick T. H. (2010). Assessment of Nonischemic myocardial fibrosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 56, 89–97. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G., Hill M. A., Sowers J. R. (2018). Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: An Update of Mechanisms Contributing to This Clinical Entity. Circ. Res. 122, 624–638. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Xiong Y., Li X., Yang Y. (2021). Cardiac Fibrosis: Cellular Effectors, Molecular Pathways, and Exosomal Roles. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 715258. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.715258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Shen Q., Chen H., Yang Z., Shuai M., Zheng S. (2018). Galectin-1 gene silencing inhibits the activation and proliferation but induces the apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells from mice with liver fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 43, 103–116. 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston E. F., Gillis T. E. (2022). Regulation of collagen deposition in the trout heart during thermal acclimation. Curr. Res. Physiology 5, 99–108. 10.1016/j.crphys.2022.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y.-H., Park S.-H., Sim Y. E., Oh M.-S., Suh H. W., Lee J.-Y., et al. (2023). Highly water-soluble diacetyl chrysin ameliorates diabetes-associated renal fibrosis and retinal microvascular abnormality in db/db mice. Nutr. Res. Pract. 17, 421–437. 10.4162/nrp.2023.17.3.421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathiriya J. J., Nakra N., Nixon J., Patel P. S., Vaghasiya V., Alhassani A., et al. (2017). Galectin-1 inhibition attenuates profibrotic signaling in hypoxia-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Cell. Death Discov. 3, 17010. 10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi M., Techigawara M., Ishihata T., Asakura T., Saito F., Maehara K., et al. (1997). A comparison of ultrastructural changes on endomyocardial biopsy specimens obtained from patients with diabetes mellitus with and without hypertension. Heart Vessels 12, 267–274. 10.1007/BF02766802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil H., Kanisicak O., Prasad V., Correll R. N., Fu X., Schips T., et al. (2017). Fibroblast-specific TGF-β–Smad2/3 signaling underlies cardiac fibrosis. J. Clin. Investigation 127, 3770–3783. 10.1172/JCI94753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong P., Christia P., Frangogiannis N. G. (2014). The pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 549–574. 10.1007/s00018-013-1349-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonce N., Griffin R., Dings R. (2017). Galectin-1 Inhibitor OTX008 Induces Tumor Vessel Normalization and Tumor Growth Inhibition in Human Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Models. IJMS 18, 2671. 10.3390/ijms18122671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostic M., Dzopalic T., Marjanovic G., Urosevic I., Milosevic I. (2021). Immunomodulatory effects of galectin-1in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. cejoi 46, 54–62. 10.5114/ceji.2021.105246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C.-S., Chou R.-H., Lu Y.-W., Tsai Y.-L., Huang P.-H., Lin S.-J. (2020). Increased circulating galectin-1 levels are associated with the progression of kidney function decline in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Sci. Rep. 10, 1435. 10.1038/s41598-020-58132-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong R. Y., Sattar H., Wu H., Vorobiof G., Gandla V., Steel K., et al. (2008). Incidence and Prognostic implication of Unrecognized myocardial scar characterized by cardiac magnetic resonance in diabetic patients without clinical evidence of myocardial infarction. Circulation 118, 1011–1020. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.727826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung L. Y., Chan C. P. Y., Leung Y. K., Jiang H. L., Abrigo J. M., Wang D. F., et al. (2014). Comparison of miR-124-3p and miR-16 for early diagnosis of hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. Clin. Chim. Acta 433, 139–144. 10.1016/j.cca.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levick S. P., Widiapradja A. (2020). The diabetic cardiac fibroblast: mechanisms underlying phenotype and function. IJMS 21, 970. 10.3390/ijms21030970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zhu H., Shen E., Wan L., Arnold J. M. O., Peng T. (2010). Deficiency of Rac1 Blocks NADPH oxidase activation, inhibits Endoplasmic Reticulum stress, and reduces myocardial remodeling in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 59, 2033–2042. 10.2337/db09-1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Zang A., Zhang L., Zhang H., Zhao L., Qi Z., et al. (2014). Chrysin ameliorates diabetes-associated cognitive deficits in Wistar rats. Neurol. Sci. 35, 1527–1532. 10.1007/s10072-014-1784-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Liu F., Sun Z., Peng Z., You T., Yu Z. (2020). LncRNA NEAT1 promotes apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis models by targeting miR-590-3p. Exp. Ther. Med. 20, 3290–3300. 10.3892/etm.2020.9079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Long L., Yuan F., Liu F., Liu H., Peng Y., et al. (2015). High glucose‐induced Galectin‐1 in human podocytes implicates the involvement of Galectin‐1 in diabetic nephropathy. Cell. Biol. Int. 39, 217–223. 10.1002/cbin.10363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z.-G., Yuan Y.-P., Wu H.-M., Zhang X., Tang Q.-Z. (2018). Cardiac fibrosis: new insights into the pathogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 14, 1645–1657. 10.7150/ijbs.28103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew T., Karunanithy R., Yee M. H., Natarajan P. N. (1980). Hepatotoxicity of dimethylformamide and dimethylsulfoxide at and above the levels used in some aflatoxin studies. Lab. Investig. 42, 257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclennan S. V., Fisher E., Martell S. Y., Death A. K., Williams P. F., Lyons J. G., et al. (2000). Effects of glucose on matrix metalloproteinase and plasmin activities in mesangial cells: possible role in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 58, S81–S87. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07713.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagavally R. R., Sunilkumar S., Akhtar M., Trombetta L. D., Ford S. M. (2021). Chrysin ameliorates Cyclosporine-A-induced renal fibrosis by inhibiting TGF-β1-induced epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. IJMS 22, 10252. 10.3390/ijms221910252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunoda S., Genda A., Sugihara N., Nakayama A., Mizuno S., Takeda R. (1985). Quantitative approach to the histopathology of the biopsied right ventricular myocardium in patients with diabetes mellitus. Heart Vessels 1, 43–47. 10.1007/BF02066486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou D., Ni D., Li R., Jiang X., Chen X., Li H. (2021). Galectin-1 alleviates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by reducing the inflammation and apoptosis of cardiomyocytes. Exp. Ther. Med. 23, 143. 10.3892/etm.2021.11066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan T. H. G., Paliogiannis P., Nasrallah G. K., Giordo R., Eid A. H., Fois A. G., et al. (2021). Emerging cellular and molecular determinants of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78, 2031–2057. 10.1007/s00018-020-03693-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman S. O., Grove L. M., Paruchuri S., Southern B. D., Abraham S., Niese K. A., et al. (2014). TRPV4 mediates myofibroblast differentiation and pulmonary fibrosis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 124, 5225–5238. 10.1172/JCI75331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani N., Bharti S., Bhatia J., Tomar A., Nag T. C., Ray R., et al. (2015). Inhibition of TGF-β by a novel PPAR-γ agonist, chrysin, salvages β-receptor stimulated myocardial injury in rats through MAPKs-dependent mechanism. Nutr. Metab. (Lond) 12, 11. 10.1186/s12986-015-0004-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan T. J., Lyons M. M., Ahmed S. S., Levinson G. E., Oldewurtel H. A., Ahmad M. R., et al. (1977). Evidence for cardiomyopathy in Familial diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Investig. 60, 884–899. 10.1172/JCI108843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo I., Frangogiannis N. G. (2016). Diabetes-associated cardiac fibrosis: cellular effectors, molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 90, 84–93. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadat S., Noureddini M., Mahjoubin-Tehran M., Nazemi S., Shojaie L., Aschner M., et al. (2021). Pivotal role of TGF-β/Smad signaling in cardiac fibrosis: non-coding RNAs as Effectual Players. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 7, 588347. 10.3389/fcvm.2020.588347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara M., Hirashiki A., Cheng X. W., Bando Y., Ohshima K., Okumura T., et al. (2011). Association of diabetes mellitus with myocardial collagen accumulation and relaxation impairment in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 92, 348–355. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama A., Asaad G., Shaheen A. (2022). Chrysin ameliorates STZ-induced diabetes in rats: possible impact of modulation of TLR4/NF-κβ pathway. Res. Pharma Sci. 17, 1–11. 10.4103/1735-5362.329921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarghandian S., Azimi-Nezhad M., Samini F., Farkhondeh T. (2016). Chrysin treatment improves diabetes and its complications in liver, brain, and pancreas in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 94, 388–393. 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano M., Fukuda K., Sato T., Kawaguchi H., Suematsu M., Matsuda S., et al. (2001). ERK and p38 MAPK, but not NF-kappaB, are critically involved in reactive oxygen species-mediated induction of IL-6 by angiotensin II in cardiac fibroblasts. Circulation Res. 89, 661–669. 10.1161/hh2001.098873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See F., Thomas W., Way K., Tzanidis A., Kompa A., Lewis D., et al. (2004). p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition improves cardiac function and attenuates left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction in the rat. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 44, 1679–1689. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senador D., Kanakamedala K., Irigoyen M. C., Morris M., Elased K. M. (2009). Cardiovascular and autonomic phenotype of db/db diabetic mice. Exp. Physiol. 94, 648–658. 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.046474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seropian I. M., González G. E., Maller S. M., Berrocal D. H., Abbate A., Rabinovich G. A. (2018). Galectin-1 as an emerging mediator of Cardiovascular inflammation: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 8696543–8696611. 10.1155/2018/8696543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamhart P. E., Luther D. J., Adapala R. K., Bryant J. E., Petersen K. A., Meszaros J. G., et al. (2014). Hyperglycemia enhances function and differentiation of adult rat cardiac fibroblasts. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 92, 598–604. 10.1139/cjpp-2013-0490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M., Umeda K., Sugihara N., Yoshio H., Ino H., Takeda R., et al. (1993). Collagen remodelling in myocardia of patients with diabetes. J. Clin. Pathology 46, 32–36. 10.1136/jcp.46.1.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde A. V., Humeres C., Frangogiannis N. G. (2017). The role of α-smooth muscle actin in fibroblast-mediated matrix contraction and remodeling. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 1863, 298–309. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland C. G. G., Fisher B. M., Frier B. M., Dargie H. J., More I. A. R., Lindop G. B. M. (1989). Endomyocardial biopsy pathology in insulin‐dependent diabetic patients with abnormal ventricular function. Histopathology 14, 593–602. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1989.tb02200.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talebi M., Talebi M., Farkhondeh T., Simal-Gandara J., Kopustinskiene D. M., Bernatoniene J., et al. (2022). Promising protective effects of chrysin in cardiometabolic diseases. CDT 23, 458–470. 10.2174/1389450122666211005113234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman V., Ruskoaho H. (2016). Cardiac fibrosis in myocardial infarction—from repair and remodeling to regeneration. Cell. Tissue Res. 365, 563–581. 10.1007/s00441-016-2431-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M., Zhang W., Lin H., Jiang H., Dai H., Zhang Y. (2007). High glucose promotes the production of collagen types I and III by cardiac fibroblasts through a pathway dependent on extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 301, 109–114. 10.1007/s11010-006-9401-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao G., Miller L. J., Lincoln J. (2013). Snai1 is important for avian epicardial cell transformation and motility: the Role of Snai1 in the Avian Epicardium. Dev. Dyn. 242, 699–708. 10.1002/dvdy.23967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. V., Coker M. L., Zellner J. L., Handy J. R., Crumbley A. J., Spinale F. G. (1998). Increased matrix metalloproteinase activity and selective upregulation in LV myocardium from patients with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 97, 1708–1715. 10.1161/01.CIR.97.17.1708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J., An X., Niu L. (2017). Myocardial fibrosis in congenital and pediatric heart disease. Exp. Ther. Med. 13, 1660–1664. 10.3892/etm.2017.4224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta M. C., Petrillo F., Gesualdo C., Rossi S., Corte A. D., Váradi J., et al. (2022). Effects of the Calix[4]arene derivative compound OTX008 on high glucose-stimulated ARPE-19 cells: Focus on galectin-1/TGF-β/EMT pathway. Molecules 27, 4785. 10.3390/molecules27154785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkbey E. B., Backlund J.-Y. C., Genuth S., Jain A., Miao C., Cleary P. A., et al. (2011). Myocardial structure, function, and scar in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 124, 1737–1746. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.022327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner L., Blythe H. (2019). Cardiac fibroblast p38 MAPK: a Critical regulator of myocardial remodeling. JCDD 6, 27. 10.3390/jcdd6030027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchinaka A., Kawaguchi N., Mori S., Hamada Y., Miyagawa S., Saito A., et al. (2014). Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 and -3 improves cardiac function in an ischemic cardiomyopathy model rat. Tissue Eng. Part A 20, 3073–3084. 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heerebeek L., Hamdani N., Handoko M. L., Falcao-Pires I., Musters R. J., Kupreishvili K., et al. (2008). Diastolic Stiffness of the failing diabetic heart: Importance of fibrosis, advanced Glycation end products, and Myocyte resting Tension. Circulation 117, 43–51. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.728550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoeven K. H., Factor S. M. (1990). A comparison of the pathological spectrum of hypertensive, diabetic, and hypertensive-diabetic heart disease. Circulation 82, 848–855. 10.1161/01.CIR.82.3.848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.-H., Huang X.-R., Zhang Y., Li Y.-Q., Chen H., Yan B. P., et al. (2013). Smad7 inhibits angiotensin II-induced hypertensive cardiac remodelling. Cardiovasc. Res. 99, 665–673. 10.1093/cvr/cvt151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels A., Van Den Hoff M. J. B., Adamo R. F., Phelps A. L., Lockhart M. M., Sauls K., et al. (2012). Epicardially derived fibroblasts preferentially contribute to the parietal leaflets of the atrioventricular valves in the murine heart. Dev. Biol. 366, 111–124. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann D., Rutschow S., Jäger S., Linderer A., Anker S., Riad A., et al. (2007). Contributions of inflammation and cardiac matrix metalloproteinase activity to cardiac failure in diabetic cardiomyopathy: the role of angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonism. Diabetes 56, 641–646. 10.2337/db06-1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M., Xing Q., Duan H., Qin G., Sang N. (2022). Suppression of NADPH oxidase 4 inhibits PM2.5-induced cardiac fibrosis through ROS-P38 MAPK pathway. Sci. Total Environ. 837, 155558. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Sun J., Tong Q., Lin Q., Qian L., Park Y., et al. (2016). The role of ERK1/2 in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. IJMS 17, 2001. 10.3390/ijms17122001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z., Shen D., Liao J., Zhang Y., Chen Y., Shi G., et al. (2018). Hypoxia suppresses TGF-B1-induced cardiac Myocyte myofibroblast transformation by inhibiting Smad2/3 and Rhoa signaling pathways. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 45, 250–257. 10.1159/000486771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ytrehus K., Hulot J.-S., Perrino C., Schiattarella G. G., Madonna R. (2018). Perivascular fibrosis and the microvasculature of the heart. Still hidden secrets of pathophysiology? Vasc. Pharmacol. 107, 78–83. 10.1016/j.vph.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Yang C., Zhang S., Ke Z.-X., Chen D.-X., Li Y.-Q., et al. (2021a). The Imbalance of MMP-2/TIMP-2 and MMP-9/TIMP-1 contributes to collagen deposition disorder in diabetic non-Injured Skin. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 734485. 10.3389/fendo.2021.734485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.-J., Xu N., Zhang X.-C., Zhu Y.-Y., Liu S.-W., Chang Y.-N. (2021b). Chrysin improves glucose and Lipid Metabolism disorders by regulating the AMPK/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in insulin-Resistant HepG2 cells and HFD/STZ-Induced C57BL/6J mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 5618–5627. 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c01109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.