Abstract

Background

Tumor-associated inflammation suggests that anti-inflammatory medication could be beneficial in cancer therapy. Loratadine, an antihistamine, has demonstrated improved survival in certain cancers. However, the anticancer mechanisms of loratadine in lung cancer remain unclear.

Objective

This study investigates the anticancer mechanisms of loratadine in lung cancer.

Methods

A retrospective cohort of 4,522 lung cancer patients from 2006 to 2018 was analyzed to identify noncancer drug exposures associated with prognosis. Cellular experiments, animal models, and RNA-seq data analysis were employed to validate the findings and explore the antitumor effects of loratadine.

Results

This retrospective study revealed a positive association between loratadine administration and ameliorated survival outcomes in lung cancer patients, exhibiting dose dependency. Rigorous in vitro and in vivo assays demonstrated that apoptosis induction and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) reduction were stimulated by moderate loratadine concentrations, whereas pyroptosis was triggered by elevated dosages. Intriguingly, loratadine was found to augment PPARγ levels, which acted as a gasdermin D transcription promoter and caspase-8 activation enhancer. Consequently, loratadine might incite a sophisticated interplay between apoptosis and pyroptosis, facilitated by the pivotal role of caspase-8.

Conclusion

Loratadine use is linked to enhanced survival in lung cancer patients, potentially due to its role in modulating the interplay between apoptosis and pyroptosis via caspase-8.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13046-023-02914-8.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Loratadine, Apoptosis, Pyroptosis, Caspase8

Introduction

Lung cancer, with an incidence rate of 11.4% and a mortality rate of 18%, significantly threatens human survival and social development [1]. The complex relationship between inflammation and tumor progression suggests that inflammatory microenvironments could either prevent or promote tumor formation. On the one hand, chronic inflammation shares similarities with cancer, such as increased angiogenesis and apoptosis inhibition [2]. On the other hand, it may prevent tumors by enhancing immune surveillance resulting from an immune response [3, 4]. Studies have shown that anti-inflammatory and antioxidant treatments may prevent or delay cancer onset and development. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin, metformin, and statins, have anticancer effects, along with other cell and inflammatory factor inhibitors [5, 6]. Recent research has begun to explore the potential of antihistamines in cancer treatment.

Antihistamines, functioning as antagonists or inverse agonists of histamine receptors, are employed in the management of conditions such as allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, and urticaria [7]. Recent investigations have posited a potential application of antihistamines such as cimetidine, terfenadine and astemizole in the realm of cancer therapy [8–11]. For instance, some researchers observed that histamine can prevent the proliferation of a diverse array of cancerous cells, suggesting that antihistamines may serve as viable inhibitors of tumor expansion [12]. Shah and Stonier proposed that the influence of these drugs on cellular growth, apoptosis, and angiogenesis may confer anticancer properties [13]. Additional researchers have documented associations between antihistamine utilization and decreased risk of colorectal, breast, and lung cancers, underscoring the need for further exploration of the potential advantages of antihistamines in cancer prevention and management [14, 15].

The aforementioned studies offer an expanded perspective on the possible implications of antihistamines in cancer therapy. However, their exact therapeutic potential in Asian people and the most effective approaches for incorporating them into cancer treatment regimens remain to be clarified. As a result, our study aims to examine the anticancer mechanisms of loratadine, a commonly employed antihistamine, by employing Cox regression models to identify potential associations between noncancer drug exposure and patient prognosis. To corroborate our findings from the retrospective analysis and investigate the antitumor efficacy of the candidate agent, we conducted observations utilizing cultured cells, various animal models, and computational assessments of RNA-seq data.

Results

Patients receiving loratadine have better survival

Our study included 4522 patients, with 529 deaths (9.7%) during follow-up. Adenocarcinoma was the most common type (78.1%). Loratadine was used by 1299 patients (28.7%), with higher usage in the living group. Of the entire cohort, 41.1% were prescribed ipratropium bromide, 9.6% fluconazole, 6.9% loratadine, 11.3% ranitidine, 9.5% vitamin B6, 14.2% riboflavin sodium phosphate, 14.2% myrtle oil enteric-coated capsules, 1.3% felodipine, 4.0% cefetamet ivoxil, and 11.3% vitamin B6. Significant differences in medication usage, except for felodipine, were observed between the living and deceased groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of patients

| Variables | level | Overall | Alive | Death | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 4522 | 3993 | 529 | ||

| Age (mean (SD)) | 58.77 (10.65) | 58.42 (10.73) | 61.39 (9.70) | < 0.001 | |

| Sex (%) | Male | 2540 (56.2) | 2148 (53.8) | 392 (74.1) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 1982 (43.8) | 1845 (46.2) | 137 (25.9) | ||

| Smoke (%) | No | 2393 (52.9) | 2205 (55.2) | 188 (35.5) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 1401 (31.0) | 1165 (29.2) | 236 (44.6) | ||

| Unknown | 728 (16.1) | 623 (15.6) | 105 (19.8) | ||

| Marital status(%) | Married (including common law) | 4355 (96.3) | 3843 (96.2) | 512 (96.8) | 0.596 |

| Divorced | 4 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Single (never married) | 58 (1.3) | 54 (1.4) | 4 (0.8) | ||

| Unknown | 105 (2.3) | 92 (2.3) | 13 (2.5) | ||

| Histologic_Type_ICD_O_3 (%) | Adenocarcinoma | 3530 (78.1) | 3188 (79.8) | 342 (64.7) | < 0.001 |

| Adenosquamous | 63 (1.4) | 44 (1.1) | 19 (3.6) | ||

| Large cell carcinoma, | 25 (0.6) | 18 (0.5) | 7 (1.3) | ||

| Neuroendocrine cancer | 54 (1.2) | 44 (1.1) | 10 (1.9) | ||

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 10 (0.2) | 9 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Sarcomatoid carcinoma | 47 (1.0) | 35 (0.9) | 12 (2.3) | ||

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 64 (1.4) | 45 (1.1) | 19 (3.6) | ||

| Small cell carcinoma | 621 (13.7) | 510 (12.8) | 111 (21.0) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | 107 (2.4) | 99 (2.5) | 8 (1.5) | ||

| Grade (%) | other | 503 (11.1) | 496 (12.4) | 7 (1.3) | < 0.001 |

| Grade IModerately differentiated; Grade II | 1538 (34.0) | 1362 (34.1) | 176 (33.3) | ||

| Poorly differentiated; Grade III | 1103 (24.4) | 906 (22.7) | 197 (37.2) | ||

| Undifferentiated; anaplastic; Grade IV, | 7 (0.2) | 5 (0.1) | 2 (0.4) | ||

| Unknown | 1371 (30.3) | 1224 (30.7) | 147 (27.8) | ||

| Loratadine use | No | 3223 (71.3) | 2812 (70.4) | 411 (77.7) | |

| Use | 1299 (28.7) | 1181 (29.6) | 118 (22.3) | 0.001 |

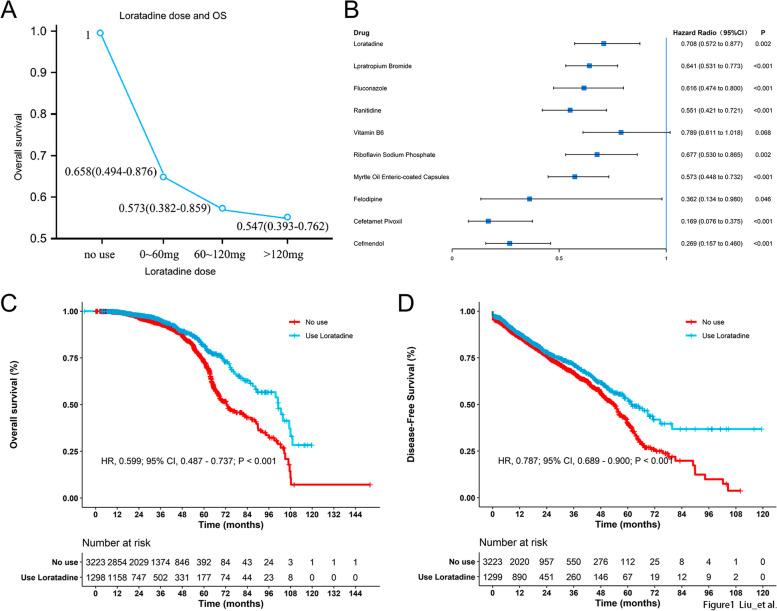

Following both univariate and multivariate analyses, significant associations with lung cancer overall survival (OS) were observed for loratadine (aHR 0.708, 95% CI, 0.572–0.877), ipratropium bromide (aHR 0.641, 95% CI, 0.531–0.773), fluconazole (aHR 0.616, 95% CI, 0.474–0.8), ranitidine (aHR 0.551, 95% CI, 0.421–0.721), Vitamin B6 (aHR 0.789, 95% CI, 0.611–1.018), Sodium Riboflavin Phosphate (aHR 0.677, 95% CI, 0.53–0.865), Standard Myrtle Oil, Dissolved Capsules (adult + size) (aHR 0.573, 95% CI, 0.448–0.732), the use of felodipine (aHR 0.362, 95% CI, 0.134–0.98), cefetamate (aHR 0.169, 95% CI, 0.76–0.375), and cefamandole (aHR 0.269, 95% CI, 0.157–0.46) were all significantly associated with lung cancer OS (Fig. 1B). However, only loratadine (aHR 0.859, 95% CI, 0.748–0.987), felodipine (aHR 0.706, 95% CI, 0.426–1.17), cefetamet (aHR 0.594, 95% CI, 0.421–0.838), and cefamandole (aHR 0.453, 95% CI, 0.302–0.679) maintained significant associations with lung cancer DFS (Fig. 1B and Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Uptake of loratadine is correlated with better survival in patients diagnosed with lung cancer. A Lung cancer mortality decreased in a dose-dependent manner with the increasing cumulative use of loratadine. B Hazard ratio for different drugs in the univariate analysis of OS. C-D The overall survival curve and disease-free survival curve with and without loratadine use

Table 2.

Hazard ratio for univariate analyses of DFS in different drugs

| Drug use | aHR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Loratadine | 0.859(0.748–0.987) |

| Lpratropium romide | 1.021(0.897–1.162) |

| Fluconazole | 1.153(0.947–1.403) |

| Ranitidine | 1.314(1.099–1.572) |

| Vitamin B6 | 1.256(1.064–1.483) |

| Riboflavin Sodium Phosphate | 1.017(0.853–1.213) |

| Myrtle Oil Enteric-coated Capsules | 0.894(0.748–1.069) |

| Felodipine | 0.706(0.426–1.17) |

| Cefetamet Pivoxil | 0.594(0.421–0.838) |

| Cefmendol | 0.453(0.302–0.679) |

The concomitant use of loratadine and other medications exhibited a reduced mortality risk compared to the administration of these drugs individually (Fig. E1). A dose-dependent relationship was observed between cumulative loratadine consumption and a decline in lung cancer mortality (p = 0.015 for trend test, Fig. 1A). Additionally, significant disparities were detected in the OS and PFS curves when comparing patients with and without loratadine treatment (Fig. 1C-D).

Taking into account the impact of chemotherapy on drug utilization, lung cancer risk, and mortality, the magnitude of the association between drug use and OS or DFS exhibited minor variations in the stratified analysis based on chemotherapy. Nevertheless, the direction of the association remained consistent with the overarching findings. In light of potential toxic side effects, loratadine was chosen as the drug of focus for this investigation.

Moderate doses of loratadine may induce cell senescence and apoptosis while inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

Loratadine was tested to discover the potential therapeutic mechanism in vitro and in vivo. First, the IC50 values of lung cell lines were calculated according to the results of CCK8 assays (Fig. E2).

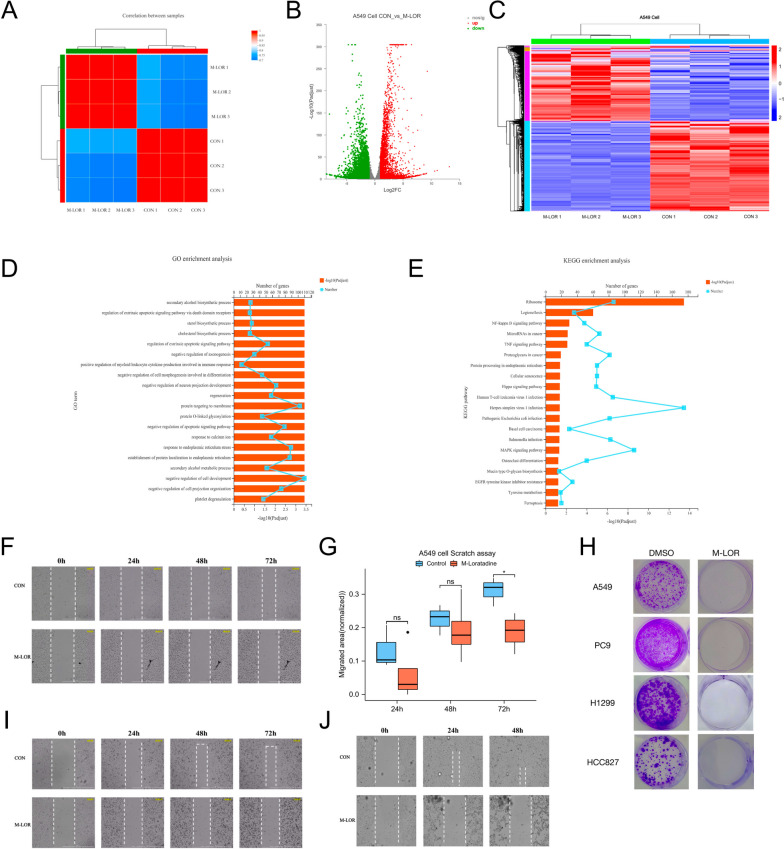

For in-depth analysis, we treated A549 cells with moderate loratadine concentrations (IC50) or DMSO (as a control to exclude effects of the solvent) for 48 h and then performed RNA sequencing (RNAseq) analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA), volcano plot analysis and heatmap of RNA-sequencing data separated loratadine-treated from control groups (Fig. 2A-C). Critically, enrichment analysis performed on the differentially expressed genes revealed many overlapping processes, particularly those related to cell senescence and negative regulation of the vascular endothelial cell proliferation signaling pathway (Fig. 2D and E, Figs. E3 and E4).

Fig. 2.

RNA sequencing of loratadine treatment in vitro. A PCA of RNA sequencing samples. B A549 cells were activated with loratadine (IC50) for 2 days (n = 3 biologically independent samples per group). RNA sequencing was performed. Differential gene expression is shown in a volcano plot. C A549 cells were activated with loratadine (IC50) for 2 days (n = 3 biologically independent samples per group). RNA sequencing was performed. Differential gene expression is shown in the heatmap. D GO enrichment categories of DEGs. E KEGG enrichment categories of DEGs. F Wound healing assay and live cell imaging of A549 cells. G Each column represents the mean value of the migrated area of the two different groups in A549 cells, and error bars indicate SD. *, p < 0.05. H Cell growth was examined by colony formation assays in various lung cancer cell lines. I Wound healing assay and live cell imaging of PC9 cells. J Wound healing assay and live cell imaging of HCC827 cells

To gain insight into the mechanism, we built a loratadine-targeted gene set based on the CTD mentioned above, of which genes were differentially expressed in the two groups (Fig. E5A). Subsequently, GO and KEGG enrichment analyses based on loratadine-targeted gene expression were further explored (Fig. E5B-G). Interestingly, the cell senescence signaling pathway was also enriched. In addition, pathways including the cell cycle, P53 signaling pathway and apoptosis were identified. Among them, cell senescence and apoptosis are frequently prevented by epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [16], which is known to broadly regulate cancer invasion and metastasis. As active caspase‐3 and caspase‐8 have been reported to enhance apoptosis, we therefore assessed whether loratadine induced apoptosis by evaluating caspase‐3/8 activity and BLC-2 reduction. Western blot analysis revealed increased cleavage of caspase‐3, caspase‐8, Bax, and PARP, while Bcl-2 levels decreased in loratadine-treated cells compared to the control group (Fig. 3G and H). Moreover, we carried out a scratch wound assay and live cell imaging of A549 (Fig. 2F, movies 1 and 2), PC9 (Fig. 2I, movies 3 and 4), and HCC827 cells (Fig. 2J, movies 5 and 6) as a functional test for cell migration and cell status in vitro. As indicated in Fig. 2G, drug treatment notably reduced the migratory ability of A549 cells in the 72-h group. The average level in the loratadine group was lower than that in the control group, with a difference of -0.124 (-0.221—-0.026), and the difference was statistically significant (t = -3.247, P = 0.023). Loratadine treatment also impacted colony formation, resulting in an 80–90% reduction compared to the control group (Fig. 2H).

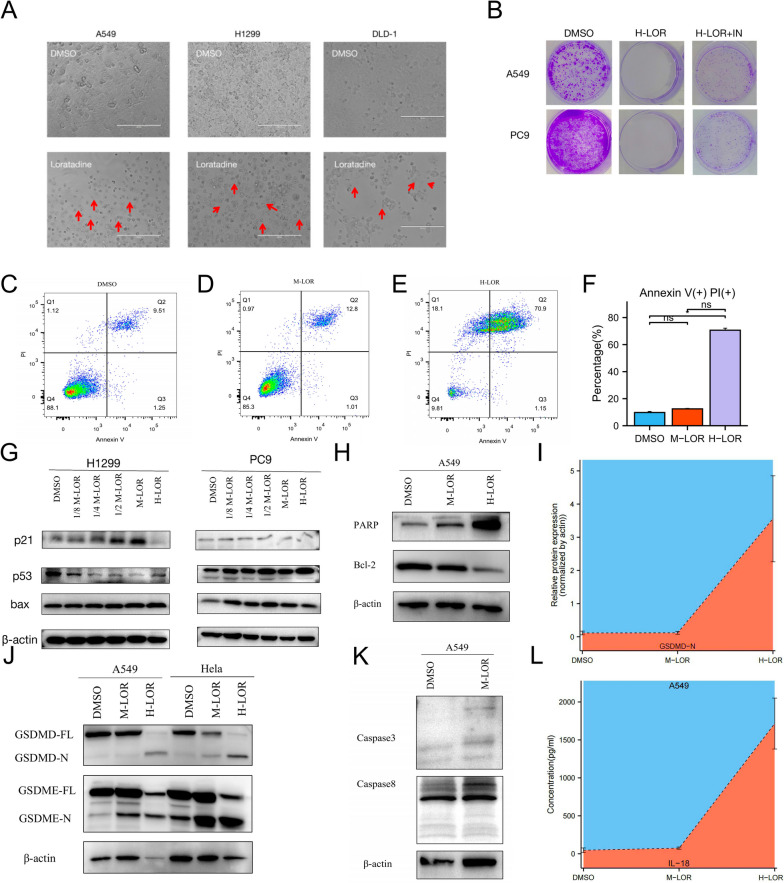

Fig. 3.

High-dose loratadine promoted the crosstalk between apoptosis and pyroptosis. A Evident balloon-like morphological changes were noted with red arrows in different cell lines treated with H-loratadine. B Cell growth was examined by colony formation in lung cancer cell lines treated with H-loratadine and combined with a GSDMD inhibitor. C to F Flow cytometry analysis of inhibitor-treated A549 cells stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI. The percentage of double-positive cells was presumably pyroptotic cells. G-K A549, PC9, and NCI-H1299 cells were treated with different doses of loratadine. The indicated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. Dose-dependent cleavage of caspases, p53, p21, bax, PARP, GSDMD and GSDME was demonstrated. GSDMD-FL, full-length GSDMD; GSDMD-N, GSDMD N-terminal domain. GSDME-FL, full-length GSDME; GSDME-N, GSDME N-terminal domain. L Release from A549 cells treated with H-loratadine. Each column represents the mean value of three biological replicates, and error bars indicate SD. ***p < 0.001

High-dose loratadine promotes pyroptosis and interacts with apoptosis

Apoptotic signaling, which involves the activation of caspases, such as caspase-8 and caspase-3, can induce other types of cell death. Therefore, we administered a high dose of loratadine (twofold IC50, H-loratadine) to further investigate its effects. After 48 h of treatment, compared with the DMSO group, cells in the loratadine group displayed distinct membrane blebbing morphological changes when observed under a microscope (Fig. 3A). Colony formation with H-loratadine resulted in a variable effect, with over a 90% reduction in colony formation compared to the DMSO group (Fig. 3B). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that high doses of loratadine can induce pyroptosis, with a significantly increased proportion of Annexin V and PI double-positive staining in the high-dose loratadine group (70.667 ± 2.558%) compared to the control group (9.773 ± 1.315%), and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3C-F). The cleavage and activation of GSDMD or GSDME by inflammatory caspases, such as caspase-1, caspase-3, caspase-4 and caspase-8, can be assessed in the H-loratadine group by Western blot analysis. (Figs. 3J, I and 4E). During our investigation, we made a novel discovery that H-loratadine may stimulate the upregulation of PPARγ expression (Fig. 4F), which in turn acts as a promoter of GSDMD, as verified through a luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 4B). Using ELISA to detect the concentration of IL-18 in the cell supernatant, it was found that the high loratadine group was linked to an elevated release of proinflammatory cytokines, and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3L).

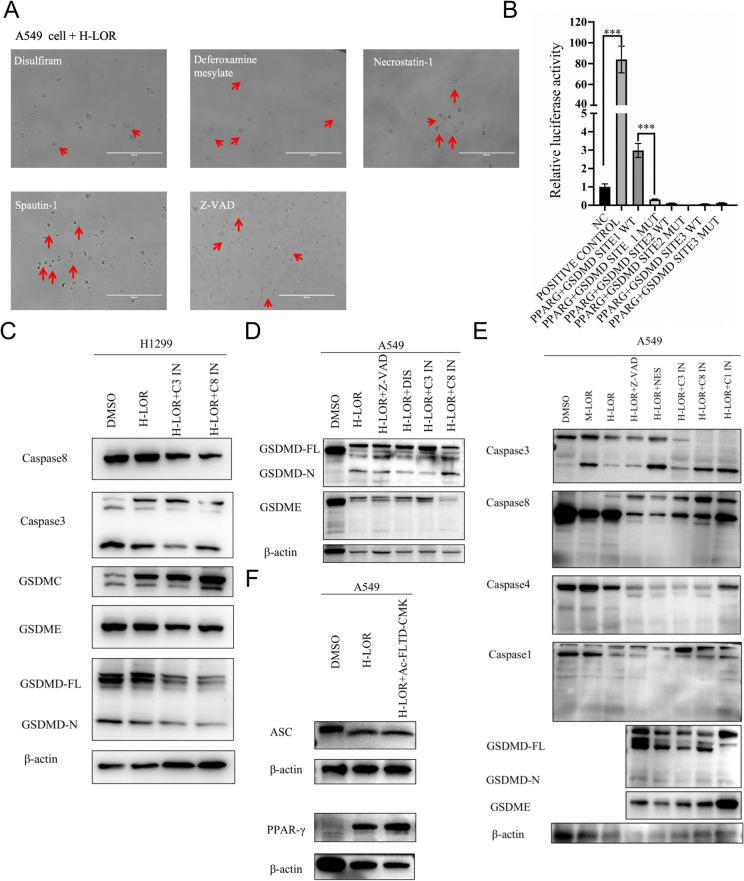

Fig. 4.

Pharmacological agents and caspase inhibitors partially reversed loratadine-induced cell death. A Pyroptotic cell changes, such as cell swelling and membrane blebbing, were noted with red arrows in A549 cells treated with H-loratadine as well as different cell death inhibitors. B Validation of PPARG as a promoter of GSDMD expression using a luciferase reporter assay. The promoter region of GSDMD was cloned upstream of the luciferase gene in the pGL3-Basic vector. The PPARG expression vector (vec PPARγ) was used to upregulate PPARγ expression. Bar graph representing relative luciferase activity in cells. Luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity for each sample. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 compared to control. C-D A549 and NCI-H1299 cells were treated with different doses of loratadine combined with cell death inhibitors or caspase inhibitors. The indicated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. GSDME-FL, full-length GSDME; GSDME-N, GSDME N-terminal domain; C1 IN, caspase 1 inhibitor (ac-YVAD-cmk); C3 IN, caspase 3 inhibitor (z-DEVD-fmk); C8 IN, caspase 8 inhibitor (z-IETD-fmk); Z-VAD pan caspase inhibitor (z-VAD-fmk); M-LOR, moderate dose of loratadine; H-LOR, high dose of loratadine

To further investigate the crosstalk between apoptosis and pyroptosis, a range of pharmacological agents, including necrostatin-1, spautin-1, deferoxamine mesylate and disulfiram, were employed to investigate the potential occurrence of pyroptosis in H-loratadine-treated lung cancer cells. These compounds were utilized to discern whether cells undergo pyroptotic cell death. Additionally, a panel of caspase inhibitors, such as z-VAD-fmk, z-DEVD-fmk, z-IETD-fmk, ac-FLTD-cmk, and ac-YVAD-cmk, were used to assess their capacity to inhibit cell apoptosis or pyroptosis. In Fig. 4A, the ballooning-like cells were partially rescued by disulfiram but not by inhibitors of apoptosis (z-VAD-fmk), ferroptosis (deferoxamine mesylate), necroptosis (necrostatin-1) or autophagy (spautin-1). Western blot analysis presented in Fig. 4C-E demonstrated that caspase 3 inhibitor (z-DEVD-fmk), caspase 8 inhibitor (z-IETD-fmk), caspase 1/4/5 inhibitor (ac-FLTD-cmk, also known as GSDMD inhibitor) and caspase 1 inhibitor (ac-YVAD-cmk) can partially inhibit M-loratadine-induced apoptosis as well as H-loratadine-induced pyroptosis in A549 cells or H1299 cells. Our results contribute to a more profound exploration of the cell death mechanisms in loratadine-induced cell death.

Loratadine treatment suppresses tumorigenesis and activates p53 and GSDMD in C57BL/6 mice

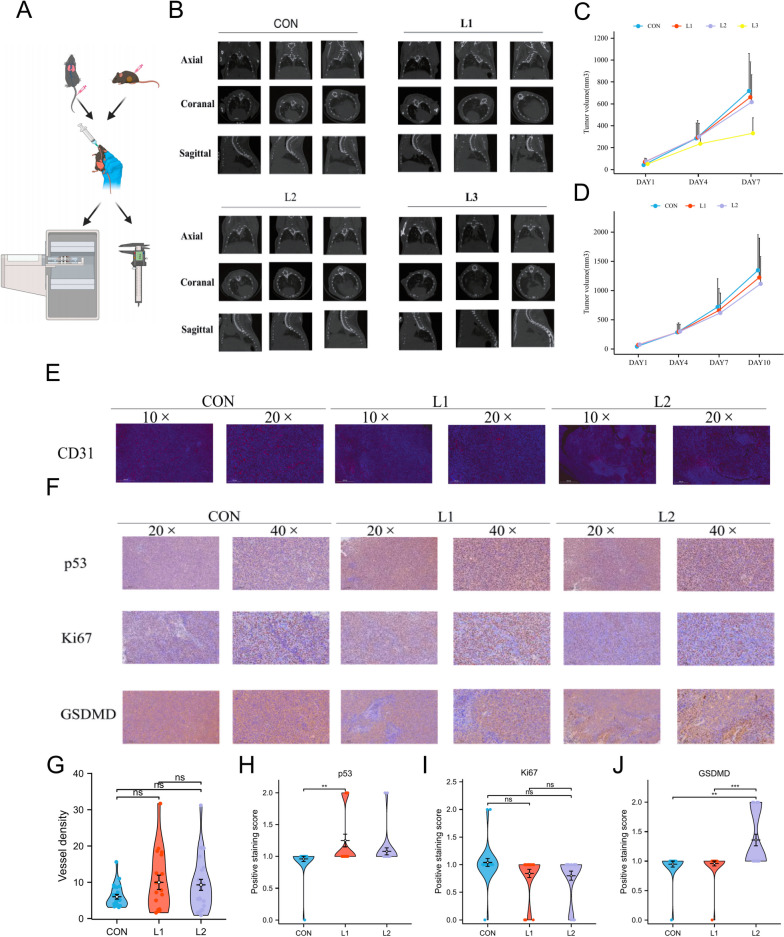

Piqued by the clinical and ex vivo findings, we sought to determine whether loratadine exhibits tumor-suppressive properties. Lewis cells (LLCs) were implanted in the right flank region of C57BL/6 mice, and metastatic colonization capacity was evaluated by assessing tumor nodule formation in the lungs after LLC tail vein injection. All models were administered loratadine or vehicle via intragastric administration. Tumor size measurements demonstrated that loratadine diminished tumor cell growth and metastasis in C57BL/6 mice in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A-D). Moreover, the vascular morphology of mouse tumor sections was stained with DAPI and CD31 to evaluate the antivascularization ability of loratadine. Although the loratadine-treated group exhibited reduced microvessel density compared to vehicle-treated mice, this difference was not statistically significant in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 5E-G). IHC staining verified a minor decrease in the levels of Ki67 with a significant increase in p53 and GSDMD staining in loratadine-treated LLC tumors (Fig. 5F and H-J). In conclusion, these studies indicate that loratadine may prevent tumors from growing, presumably through the regulation of proliferation via apoptotic and pyroptotic pathways as well as the regulation of the immune system.

Fig. 5.

Loratadine treatment suppresses tumorigenesis in vivo. A Schematic overview of the mouse experimental model protocol. B Micro-CT images of lungs from mice following LLC tail vain injection with or without loratadine treatment. Three-dimensional rendering of micro-CT data with lungs in gray; the lost part represents the tumor. C-D The indicated cells were subcutaneously injected (0.5–1 × 10.6 cells per mouse) into C57BL/6 mice (n = 5). Tumor formation was analyzed. CON, vehicle group; L1, 5 mg/kg/d resveratrol group; L2, 35 mg/kg/d resveratrol group; and L3, 175 mg/kg/d resveratrol group. After 7 days of treatment, 4 mice died in the L3 group. D Vascular morphology of mouse subcutaneous tumor sections stained with DAPI (blue) and CD31 (red). Magnification: IHC 10 × and 20 × , Scale bar: 500 µm and 200 µm. E Tumor sections stained with p53, Ki67 and GSDMD. Magnification: IHC 20 × and 40 × , Scale bar: 200 µm and 100 µm. F Each violin plot represents the quantification of vascular density. ns, no significant difference. G-I Each violin plot represents the relative expression levels of each tumor section protein. Data are presented as the means ± SDs. ns, no significant difference, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Discussion

A key finding of our study is that lung cancer patients receiving loratadine exhibit improved survival outcomes. Significant differences were observed in OS curves and PFS curves between patients with and without loratadine use. As the loratadine dose increased, patients experienced a significant improvement in outcomes. The results from animal experiments also conformed to the clinical outcomes, suggesting dose-dependent improvement. Our findings not only align with but also expand upon previous research. A study examining the impact of antihistamine use among Danish patients found that loratadine use was significantly linked to reduced all-cause mortality in patients with NSCLC or any cancer when compared to the usage of antihistamines that are not CAD [15]. Another nationwide Danish cohort also demonstrated that the use of antihistamines was related to a prognostic benefit in patients with ovarian cancer [17]. Furthermore, a recent study reported an association between improved survival in melanoma and breast cancer patients and the use of H1-antihistamines desloratadine and loratadine [18]. Recent retrospective analyses have shown that cancer patients who received antihistamines during immunotherapy treatment demonstrated dramatically enhanced survival outcomes [19].

M-loratadine have been found to influence a range of cellular pathways, notably those pertaining to the the cell cycle, cell senescence, P53 signaling pathway and apoptosis. Empirical evidence from scratch wound assays, colony formation assays, and Western blot analyses confirms that M-loratadine can concurrently induce cell senescence and apoptosis in addition to inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). This observation is in alignment with previous findings that suggest cell senescence and apoptosis may be hindered by the EMT process—a phenomenon that could enhance cellular survival during EMT [16]. Recent literature further substantiates a complex interconnection between apoptosis and senescence, indicating that both processes may be regulated by shared mitochondrial-dependent pathways [20]. In addition, these findings align with previous studies suggesting loratadine's antitumor effects through inhibiting the cell cycle or inducing "silent" cell death, such as apoptosis. For instance, loratadine may result in G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and death in colon cancer cells (COLO 205) [21]. Consistently, loratadine reverted multidrug resistance in NSCLC, breast and prostate cancer cells and sensitizes NSCLC cells to chemotherapy by inducing apoptotic and lysosomal cell death [15]. Loratadine may also directly damage DNA and activate Chk1, promoting G2/M arrest and making cells more susceptible to radiation-induced DNA damage while downregulating total Chk1 and Cyclin B [22]. Besides, researches on loratadine combination therapy also proved effective in cancer treatment. Loratadine, in combination with thioridazine may inhibit the rapamycin signaling pathway via phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target in gastrointestinal tumor [23] and effectively overcome immune evasion by suppressing CRC growth in a mouse model [24]. Moreover, H1-antihistamine treatment can enhance immunotherapy response via activation of the macrophage histamine receptor H1 [19].

Our study has uncovered some intriguing and novel findings. High-dose loratadine induced pyroptosis, a new form of cell death, alongside traditional apoptosis. Detailed analysis of cell models treated with high doses of loratadine and various inhibitors suggests a significant role for caspases in mediating both apoptotic and pyroptotic pathways. A critical discovery was that high-dose loratadine augmented the PPARγ level, which subsequently spurred GSDMD transcription by our luciferase reporter assay. This finding is further substantiated by reports in the literature indicating that PPARγ is instrumental in the regulation of caspase-8 activation [25]. Tumor sections from animal models, stained for Ki67 and GSDMD, reinforce the hypothesis that loratadine hampers tumor proliferation by promoting pyroptosis. Collectively, these results highlight a novel mechanism by which loratadine may exert anti-tumoral effects through the induction of pyroptosis.

The interplay between pyroptosis and apoptosis is intricate. They are two distinct forms of programmed cell death that are crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis and responding to varying loratadine dosages. Caspase-8, a critical molecule that interconnects apoptosis and pyroptosis, can promote apoptosis via the extrinsic pathway and regulate pyroptosis by interacting with inflammasomes and modulating inflammatory caspases and gasdermin D (GSDMD) or gasdermin E (GSDME) activity by activating other caspases, such as caspase-1, caspase-4/5, and caspase-3 [26–29]. Various studies have emphasized the crosstalk between apoptosis and pyroptosis in different contexts. Orning et al. demonstrated that caspase-8 acts as a regulator of GSDMD-driven cell death and can cleave GSDMD during bacterial infection by Yersinia, leading to pyroptosis and the release of proinflammatory cytokines [26]. Sarhan et al. demonstrated that activating caspase-8 leads to the cleavage of both gasdermin D (GSDMD) and gasdermin E (GSDME) in macrophages, which results in pyroptosis. The absence of GsdmD causes a delay in membrane rupture, which in turn prevents the morphological changes associated with cell death from transitioning to apoptosis. This finding highlights caspase-8's dual role in modulating both apoptosis and pyroptosis, depending on the cellular context [27]. These studies underscore the importance of understanding the interplay between apoptosis and pyroptosis for cancer treatment, as targeting this crosstalk may provide new therapeutic opportunities for treating various cancers.

However, our investigation had certain limitations. First, the retrospective and single-center nature of the study might introduce unidentified biases that could affect our analysis. Additionally, our study did not sufficiently investigate the greater detail in crosstalk between apoptosis and pyroptosis.

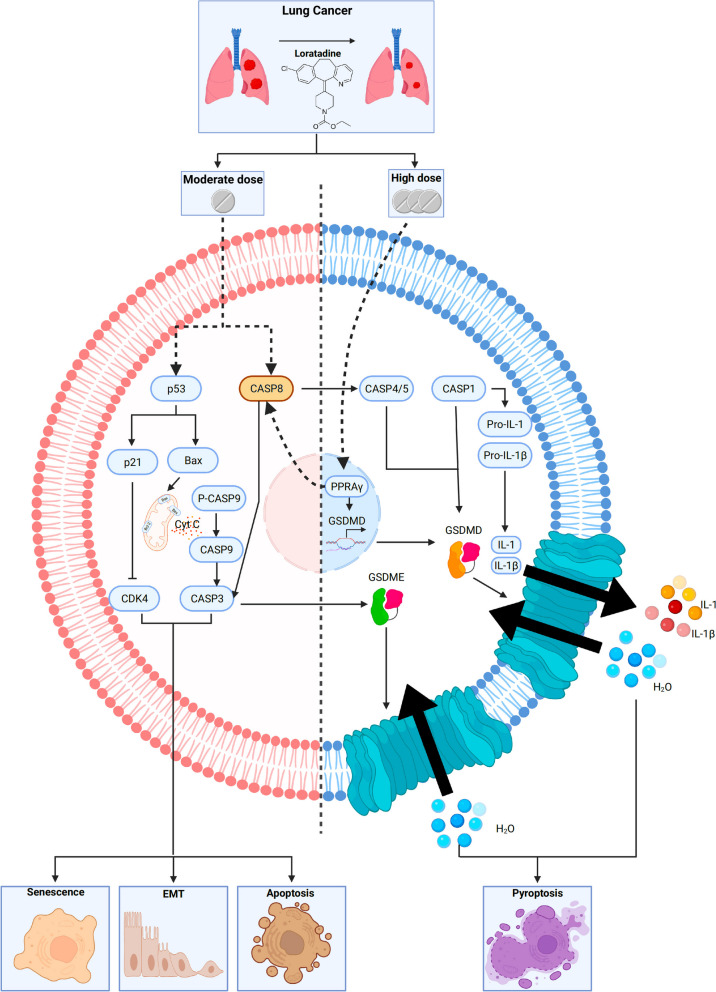

In summary, we utilized a large case‒control population, virtually complete cancer ascertainment and histological verification, and detailed prescription data. The continuous updating of prescription data, along with accurate information on drug type and quantity, allowed for an extensive evaluation of exposure patterns and eliminated recall bias. Mechanistically, loratadine has the potential to incite a complex interplay between apoptosis and pyroptosis mediated by the crucial role of caspase-8. This is accomplished via the modulation of PPARγ levels that in turn stimulate gsdmd transcription and activate caspase-8 (summarized in Fig. 6). Further studies on any effects of other antihistamines or their immune response to tumors may also be merited.

Fig. 6.

The impact of loratadine on lung cancer survival outcomes and underlying mechanisms. The administration of loratadine demonstrates a positive correlation with enhanced survival rates in individuals diagnosed with lung cancer. Loratadine could potentially foster complex crosstalk between apoptosis and pyroptosis, with caspase-8 playing a key role. This is achieved through the regulation of PPARγ levels, promoting gsdmd transcription and caspase-8 activation

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 7. Materials and Methods.

Additional file 8: Figure E1. Hazard ratios of different combinations of loratadine and other drugs.

Additional file 9: Figure E2. IC50 values of lung cell lines.

Additional file 10: Figure E3. GSEA of DEGs. Several pathways and biological processes were differentially enriched, including negative regulation of the vascular endothelial cell proliferation signaling pathway. NES, normalized enrichment score; p.adj, adjusted P value; FDR, false discovery rate.

Additional file 11: Figure E4. KEGG pathway of cell senescence (hsa04218).

Additional file 12: Figure E5. Loratadine promotes senescence and apoptosis in vitro. (A) Loratadine-targeted gene expression. (B) GO enrichment categories of DEGs. (C) KEGG pathway (hsa04218). (D) KEGG pathway (hsa04110). (E) KEGG enrichment categories of DEGs. (F) KEGG pathway (hsa04115). (G) KEGG pathway (hsa04210).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University and State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease & National Clinical Research Center for Respiratory Disease for providing access to necessary equipment, facilities, and resources for conducting this study.

Translational relevance

The identification of loratadine's anticancer mechanisms in lung cancer, including its dose-dependent effects on apoptosis, EMT, and pyroptosis, along with its ability to augment PPARγ levels and enhance caspase-8 activation, holds significant translational relevance. These findings suggest the potential of repurposing loratadine as an adjuvant therapy in lung cancer treatment. By modulating the interplay between apoptosis and pyroptosis, loratadine offers a promising avenue for improving patient outcomes. Further research could explore the clinical application of loratadine in combination with existing treatments and investigate its efficacy in other cancer types. Overall, this study provides valuable insights that may expand the therapeutic options and contribute to the development of novel strategies for lung cancer patients, addressing an unmet clinical need.

Abbreviations

- LC

Lung Cancer

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- SCLC

Small cell lung cancer

- OS

Overall survival

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- CTD

The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database

- HR

Hazard ratio

- GO

Gene Ontology enrichment

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes enrichment

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- FDR

False discovery rate

- NES

Normalized enrichment score

- TSS

Transcription start sites

- M-LOR

Moderate dose of loratadine

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- H-LOR

High dose of loratadine

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: LXW, Jianxing He, LWH, Methodology: LXW, ZR, Jiaxing Huang, CZS, XHX, LLX, CQ, DHS, LCC, LJF, ZYM, LXY, Investigation: LXW, Jianxing He, LWH, ZR, Jiaxing Huang, CZS, XHX, HM, LS, Visualization: LXW, ZR, LLX, CQ, ZYM, LXY, ZRQ, Funding acquisition: Jianxing He, LWH, Project administration: Jianxing He, LWH, LXW, Supervision: Jianxing He, LWH, CZS, HM, Writing – original draft: LXW, ZR, Jiaxing Huang, XHX, Writing – review & editing: Jianxing He, LWH, LXW.

Funding

China National Science Foundation (grant number 82022048 & 81871893), the Key Project of Guangzhou Scientific Research Project (grant number 201804020030).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiwen Liu, Ran Zhong, Jiaxing Huang, Zisheng Chen and Haoxiang Xu joint first authors.

Jianxing He and Wenhua Liang joint corresponding authors.

Contributor Information

Jianxing He, Email: drjianxing.he@gmail.com.

Wenhua Liang, Email: liangwh1987@163.com.

References

- 1.Sung H, Global Cancer Statistics 2020 et al. GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hou J, Karin M, Sun B. Targeting cancer-promoting inflammation — have anti-inflammatory therapies come of age? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(5):261–279. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-00459-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen-Jarolim E, et al. AllergoOncology: opposite outcomes of immune tolerance in allergy and cancer. Allergy. 2018;73(2):328–340. doi: 10.1111/all.13311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rigoni A, Colombo MP, Pucillo C. Mast cells, basophils and eosinophils: from allergy to cancer. Semin Immunol. 2018;35:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez-Ruiz E, et al. Prophylactic TNF blockade uncouples efficacy and toxicity in dual CTLA-4 and PD-1 immunotherapy. Nature. 2019;569(7756):428–432. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1162-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridker PM, et al. Effect of interleukin-1β inhibition with canakinumab on incident lung cancer in patients with atherosclerosis: exploratory results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10105):1833–1842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32247-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wishart DS, et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Quiroz J, et al. In vivo dual targeting of the oncogenic Ether-a-go-go-1 potassium channel by calcitriol and astemizole results in enhanced antineoplastic effects in breast tumors. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:745. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavez-Lopez MG, et al. The combination astemizole-gefitinib as a potential therapy for human lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:5795–5803. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S144506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes MD, Ward S, Crawford G, Seoane RC, Jackson WD, Kipling D, et al. Inflammation-induced IgE promotes epithelial hyperplasia and tumour growth. Elife. 2020;9:e51862. 10.7554/eLife.51862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Hadzijusufovic E, et al. H1-receptor antagonists terfenadine and loratadine inhibit spontaneous growth of neoplastic mast cells. Exp Hematol. 2010;38(10):896–907. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen PL, Cho J. Pathophysiological Roles of Histamine Receptors in Cancer Progression: Implications and Perspectives as Potential Molecular Targets. Biomolecules. 2021;11(8):1232. 10.3390/biom11081232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Shah RR, Stonier PD. Repurposing old drugs in oncology: Opportunities with clinical and regulatory challenges ahead. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(1):6–22. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fritz I, Wagner P, Olsson H. Improved survival in several cancers with use of H(1)-antihistamines desloratadine and loratadine. Transl Oncol. 2021;14(4):101029. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellegaard AM, et al. Repurposing Cationic Amphiphilic Antihistamines for Cancer Treatment. EBioMedicine. 2016;9:130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ribatti D, Tamma R, Annese T. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: a historical overview. Transl Oncol. 2020;13(6):100773. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verdoodt F, et al. Antihistamines and ovarian cancer survival: nationwide cohort study and in vitro cell viability assay. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(9):964–967. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritz I, et al. Desloratadine and loratadine stand out among common H1-antihistamines for association with improved breast cancer survival. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(9):1103–1109. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1769185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, et al. The allergy mediator histamine confers resistance to immunotherapy in cancer patients via activation of the macrophage histamine receptor H1. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(1):36–52.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Victorelli S, et al. Apoptotic stress causes mtDNA release during senescence and drives the SASP. Nature. 2023;622(7983):627–636. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06621-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen JS, et al. Checkpoint kinase 1-mediated phosphorylation of Cdc25C and bad proteins are involved in antitumor effects of loratadine-induced G2/M phase cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45(7):461–478. doi: 10.1002/mc.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soule BP, et al. Loratadine dysregulates cell cycle progression and enhances the effect of radiation in human tumor cell lines. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen T, et al. Combining thioridazine and loratadine for the treatment of gastrointestinal tumor. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(4):4573–4580. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin X, et al. Pre-activation with TLR7 in combination with thioridazine and loratadine promotes tumoricidal T-cell activity in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2020;31(10):989–996. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chi T, et al. PPAR-gamma Modulators as Current and Potential Cancer Treatments. Front Oncol. 2021;11:737776. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.737776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orning P, et al. Pathogen blockade of TAK1 triggers caspase-8-dependent cleavage of gasdermin D and cell death. Science. 2018;362(6418):1064–1069. doi: 10.1126/science.aau2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarhan J, et al. Caspase-8 induces cleavage of gasdermin D to elicit pyroptosis during Yersinia infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(46):E10888–E10897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809548115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kayagaki N, et al. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature. 2015;526(7575):666–671. doi: 10.1038/nature15541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fritsch M, et al. Caspase-8 is the molecular switch for apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis. Nature. 2019;575(7784):683–687. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 7. Materials and Methods.

Additional file 8: Figure E1. Hazard ratios of different combinations of loratadine and other drugs.

Additional file 9: Figure E2. IC50 values of lung cell lines.

Additional file 10: Figure E3. GSEA of DEGs. Several pathways and biological processes were differentially enriched, including negative regulation of the vascular endothelial cell proliferation signaling pathway. NES, normalized enrichment score; p.adj, adjusted P value; FDR, false discovery rate.

Additional file 11: Figure E4. KEGG pathway of cell senescence (hsa04218).

Additional file 12: Figure E5. Loratadine promotes senescence and apoptosis in vitro. (A) Loratadine-targeted gene expression. (B) GO enrichment categories of DEGs. (C) KEGG pathway (hsa04218). (D) KEGG pathway (hsa04110). (E) KEGG enrichment categories of DEGs. (F) KEGG pathway (hsa04115). (G) KEGG pathway (hsa04210).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.