Abstract

Dehumanization, the perception or treatment of people as subhuman, has been recognized as “endemic” in medicine and contributes to the stigmatization of people who use illegal drugs, in particular. As a result of dehumanization, people who use drugs are subject to systematically biased policies, long-lasting stigma, and suboptimal healthcare. One major contributor to the public opinion of drugs and people who use them is the media, whose coverage of these topics consistently uses negative imagery and language. This narrative review of the literature and American media on the dehumanization of illegal drugs and the people who use them provides a perspective on the components of dehumanization in each case and explores the consequences of dehumanization on health, law, and society. Drawing from language and images from American news outlets, anti-drug campaigns, and academic research, we recommend a shift away from the disingenuous trope of people who use drugs as poor, uneducated, and most likely of color. To this end, positive media portrayals and the humanization of people who use drugs can help form a common identity, engender empathy, and ultimately improve health outcomes.

Keywords: Dehumanization, media, stigma, substance use, War on Drugs

Introduction

Stigma is conceptualized by Link and Phelan (1, p. 367) as “elements of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination co-occur[ing] in a power situation that allows the components of stigma to unfold”. Closely related to stigma, dehumanization is the perception or treatment of people as subhuman (2) and includes negative evaluations of the outgroup, moral disgust, denial of agency, and comparisons of outgroup members to nonhuman entities like vermin (2–4). Most often related to ethnicity and race, dehumanization delineates an outgroup and exaggerates intergroup differences (2,5). Such attitudes have real-world effects on the populations designated as outgroups. Several studies have found such effects in medicine, where dehumanization has been recognized as an “endemic” (6). The dehumanization of people suffering from obesity (7), disability (2), psychiatric diagnoses (8), and substance use disorders (SUDs) has led to poorer healthcare delivery (9), help-seeking (10), and health outcomes (11).

American media coverage of people who use drugs (PWUD) has been particularly wrought with dehumanizing imagery and language (12). This was especially true during the period in American history from 1971 to the early 21st century known as the War on Drugs, of which Reinarman (13) identified seven components: at first, some truth existed about problems with mind-altering substances. Some truth existed about problems with mind-altering substances. Mass media amplified drug problems to increase sales. Political elites deflected attention from systemic issues for which they would otherwise need to assume responsibility and instead took a strong, moral stance against drugs without risking political support. Professional interest groups leveraged their specialization, authority, and legitimacy to define the drug problem and thus its solution while obtaining resources to do so. Cultural, socioeconomic, political, or racial conflict created the necessary context to portray a group of people who use drugs as a threat. Political elites then linked drug use to a group of people who were already deemed untrustworthy, threatening, and dangerous. Finally, the group was scapegoated for preexisting societal problems to explain how the problems arose. Individuals who used illegal drugs were often portrayed as being of color, poor, and uneducated despite not being supported by national statistics (13,14). Drug-related stories evoke stereotypical portrayals to increase viewership and ad revenue (10,13), thereby influencing “‘knee jerk’ drug crackdowns and punitive responses” (15). In addition to negative health consequences for PWUD, dehumanization has larger societal implications, including harsher punishments for individual drug offenders (4) and lower support for nondiscriminatory drug laws (16).

From referring to PWUD as “zombies” to “crack heads” and “[w]hite trash” (17,18), media portrayals of PWUD have exhibited patterns of dehumanization that we aim to bring to attention and ultimately help reverse. Most studies have focused on legislation (12) or media portrayal of a single substance (19) while we aim to elucidate a common pattern of media dehumanization and its consequences across several substances. We perform a narrative review using movies, newspapers, anti-drug advertisements, and research from the 20th century to today about opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, cannabis, and designer drugs. For each substance, we point out a pattern of media dehumanization across racial and socioeconomic lines, despite often equal rates of use across these lines (13,14,20). The key findings are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of key findings.

| Drug Type | Key Points |

|---|---|

|

| |

| General | • Media dehumanization of people who use drugs elicits real consequences such as poorer help-seeking, quality of care, and health outcomes. |

| • Dehumanization has been used as a political tool to forgo responsibility for systemic issues while scapegoating marginalized groups. | |

| Opioids | • Media portraying white victims of prescription opioid addiction versus blameworthy Black people who use heroin |

| • Media showcasing personalized stories of tragic overdoses among white people versus depersonalized opioid-related arrests | |

| • Disproportionate rates of Black and Hispanic imprisonment for opioid use | |

| Cocaine | • Media portraying rich white people using powder cocaine versus poor, urban Black people using crack cocaine |

| • Mandatory minimum sentencing limit for crack cocaine made 20 times higher than for powder cocaine despite similar psychoactive properties | |

| • Disproportionate rates of Black and Hispanic imprisonment for cocaine use and particularly crack cocaine use | |

| • Dr. Ira Chasnoff’s research on pregnant women who use cocaine unintentionally catalyzed media to misattribute the “crack baby” label to Black newborns. | |

| • Series of U.S. Sentencing Commission reports renounced stereotypes about crack cocaine use. | |

| Amphetamines | • Media depicting educated white people using cognitive-enhancing amphetamines versus poor “white trash” using methamphetamine of a “lesser breed” |

| • “Meth zombie” and “meth mouth” portrayals despite contrary research | |

| • Dehumanizing Faces of Meth anti-drug media campaign proven ineffective | |

| Cannabis | • Media attributing violence and psychosis to cannabis use after cannabis was introduced by people immigrating from Mexico despite contrary evidence |

| • Media reframing of cannabis as a “hippie” or “dropout” drug deflating personalities in tandem with the Nixon administration leveraging this negative sentiment as a weapon against the anti-Vietnam war movement | |

| • Recent humanization of people who use cannabis in line with increasing support for legalization | |

| Designer Drugs |

• Media popularizing zombie imagery and loss of self-control •Differences in the extent of dehumanization based on type of designer drug (e.g., MDMA versus bath salts) |

Opioids

The portrayal of opioids was divided along lines of perceived legality. Individuals who used “legal” prescription opioids that initially were provided by healthcare experts, were portrayed as white people who developed an addiction and became “largely blameless victims of their own biology” (19). In contrast, individuals who used “illegal” heroin were often portrayed as poor Black and Hispanic people living in cities who lack human emotion (16,19). According to an interview with a Harper’s Magazine writer, President Nixon’s domestic policy chief Johns Ehrlichman explained that Nixon’s administration saw Black people as “enemies,” associated Black people with heroin, and criminalized heroin heavily to disrupt Black communities and attack Black people “night after night on the evening news” despite knowing that the administration was “lying about the drugs” (21). Blame was deflected away from people who use prescription drugs but assigned to people who use heroin. When covering opioid use, the media showcased overdose deaths in white communities and arrest rates in Black and Hispanic communities (19). Netherland and Hansen succinctly capture this disparity by stating,

The media’s omission of personal histories of urban blacks and Latinos who use drugs or struggle with addiction has a dehumanizing effect . . . [M]edia accounts of white drug use go out of their way to humanize the person using drugs, to explain how he or she defies the stereotype of a drug user, and then to describe the potential that the individual tragically lost (19, p. 8)

These stories’ negative evaluations fuel stigma, blame, and support for punitive government policies (22). Despite similar rates of opioid use by race/ethnicity, media portrayals that did not reflect the actual statistics helped drive the disproportionate imprisonment of Black and Hispanic people for opioid use over white people (20). Only with growing research on addiction as a neurological disease (23) did opioid use begin to be portrayed more positively and shift toward medicalization: this transition mirrored a shift in the public perception of opioid use afflicting poor urban Black and Hispanic people to any member of mainstream society (19).

Cocaine

Media coverage of cocaine use followed a similar trajectory as opioid coverage. Newspapers and movies like The Wolf of Wall Street depicted powder cocaine as a glamorous drug for white high-income earners (24) but portrayed crack cocaine as the poor, urban Black equivalent (25). Even though the methods for using each were comparable, pleasant names for powder cocaine like “snow” and “white rock” contrasted with harsh names for crack cocaine like “black rock” and “gravel” (26). While powder cocaine was broadly portrayed as “relatively harmless,” crack cocaine was deemed “ruinous” (18).

People who used crack cocaine were dehumanized more so than people who used powder cocaine. The sub-human label of a “crack head” relegated an individual to the “lowest of status positions of drug subcultures” — a “loser” who lost control over one’s drug use (18). Crack cocaine was associated with dehumanizing portrayals such as Black people birthing “crack babies:” since even animals take care of their children, this trope reflected moral disgust relating to Black mothering skills (12,27). However, the consequences of being a “crack baby” were blown out of proportion, as stated by Dr. Ira Chasnoff whose research on pregnant women who use cocaine and experience birth complications unintentionally contributed to the crack baby narrative (28). Nevertheless, white mothers who used opioids were portrayed as victims (Figure 1), while the same sympathy was not extended to Black mothers who used crack cocaine (29–31). Despite his intention to shed light on the true life of poor urban Black PWUD, the photographer of the photo of the Black mother and child, for instance, was accused of not telling the full story by overlooking the “white aspect of drug addiction” (32).

Figure 1.

Media coverage of white mothers who use opioids (29) versus Black mothers who use crack cocaine (31).

Like for opioids, media reporting on cocaine use as a predominantly Black phenomenon contrasted with actual data. From 1979 to 1997, the percentage of people who reported cocaine use in the past month differed by less than 1.2% points between Black and white people (33). However, dehumanizing and threatening portrayals contributed to harsh legal crackdowns: crack cocaine elicited mandatory minimum sentencing for 5 grams compared to powder cocaine’s mandatory minimum for 100 grams (34). Consequently, people who used crack cocaine were disproportionately convicted and served more prison time for the same amount of drug possession (34). Despite more white people using crack cocaine than Black people, over 90% of people federally prosecuted for crack cocaine use were Black according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission (14,35). Of the people still in federal prison between 1994 and 2012, only 12.6% and 4.2% of powder and crack cocaine federal offenders respectively were (non-Hispanic) white while 32.3% and 88.1% of powder and crack cocaine federal offenders respectively were Black (36). Indeed, sensationalist, racist media depictions contributed to Black people being disproportionately targeted for cocaine use, especially crack cocaine use.

Despite crack cocaine being portrayed as having strong addictive properties (37,38), the potency and psychoactive effects of crack cocaine were found to be similar to those of powder cocaine. Similar to the current position held by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (39), Hatsukami and Fischman (40) concluded that individuals who have a cocaine use disorder and “who are incarcerated for the sale or possession of cocaine are better served by treatment than prison” (40). Indeed, a series of U.S. Sentencing Commission reports renounced stereotypes perpetuated by the media-induced scare by stating that no studies have shown crack cocaine to render people more prone to committing violent crimes compared to powder cocaine (14,41–43).

Amphetamines

There is a divide between portrayals of cognitive-enhancing amphetamines (e.g., Ritalin or Adderall) and methamphetamine. Amphetamines in the mid-20th century were thought to enable speedy achievement for middle-class white Americans – keeping soldiers alert, children focused, and housewives energized and thin (44). By 1991, amphetamines became the second most misused drug among young adults in the U.S. behind cannabis (45). Maintaining this trend, millennial college students, described by the New York Times Magazine as “Generation Adderall” (46), misuse “smart pills” due to the misconception that the pills will improve grades for anyone rather than treat cognitive deficits (47). The media seem to “condone” the use of cognitive-enhancing stimulants (47) as research has shown that 95% of newspaper articles described a benefit and only 58% provided risks (48). Describing the stark contrast between the social construction of problems caused by amphetamines and drugs associated with Black people, Professor Teneille Brown states,

[P]rivileged, white, college students are considered to have maximum levels of agency and emotionality. They are thus granted the status of full humans, similar to those who were tricked into being addicted to prescription pain medication, but unlike those lesser humans who willingly became addicted to crack cocaine (12, p. 2)

On the other hand, methamphetamine use was depicted negatively even before being declared “drug public enemy number one” in the U.S (49). Known as “speed freak[s]” and “tweaker[s]” (50), people who use methamphetamine were depicted as threats to themselves and denied agency (51). They were objectified as “[w]hite trash” living at “the bottom of the [w]hite racial-economic spectrum” in impoverished rural communities (51). Despite the whiteness label garnering more sympathy and not being as linked to violence (51), someone who uses methamphetamine fell out of line with white expectations of productivity and rationality but instead constituted a “criminal and inferior” member of a “lesser breed” (52) — an “Other who threatens the supposed purity of hegemonic whiteness and white social position” (53).

Subhuman portrayals of people who use methamphetamine pervaded the media and were leveraged to prevent use (53). The “meth zombie” with mutilated flesh and decaying teeth or “meth mouth” was common in popular culture despite studies discrediting these exaggerated clinical presentations (17,51,54). Aiming at students, campaigns represented young people who use meth as zombie-like criminals (17,55), and sheriff departments displayed exaggerated before and after mugshots of people with histories of methamphetamine use known as the “Faces of Meth” (53,56). However, research has shown that anti-drug media campaigns relying on dehumanizing, worst-case scenarios to elicit moral disgust fall short in engaging people who use meth to seek treatment while some recent media campaigns have centered around honest portrayals and humanizing content (17,57–60). For example, the Faces of Meth – dramatic, unrelatable depictions about “dysfunctional users”—failed to encourage people who use meth to seek treatment because the portrayals made them believe that they were not in as bad of shape as the PWUD portrayed in the campaigns (17). Unlike the Faces of Meth (Figure 2a), the South Dakota OnMeth campaign (Figure 2b) showed how an average-looking person with a relatable backstory can suffer from methamphetamine addiction to encourage people from all walks of life to seek help albeit with pushback stating that the ads might increase methamphetamine acceptability (17,59,61,62).

Figure 2.

Portrayals of people who use methamphetamine by (a) Faces of Meth (17) and (b) OnMeth.Com (61).

Cannabis

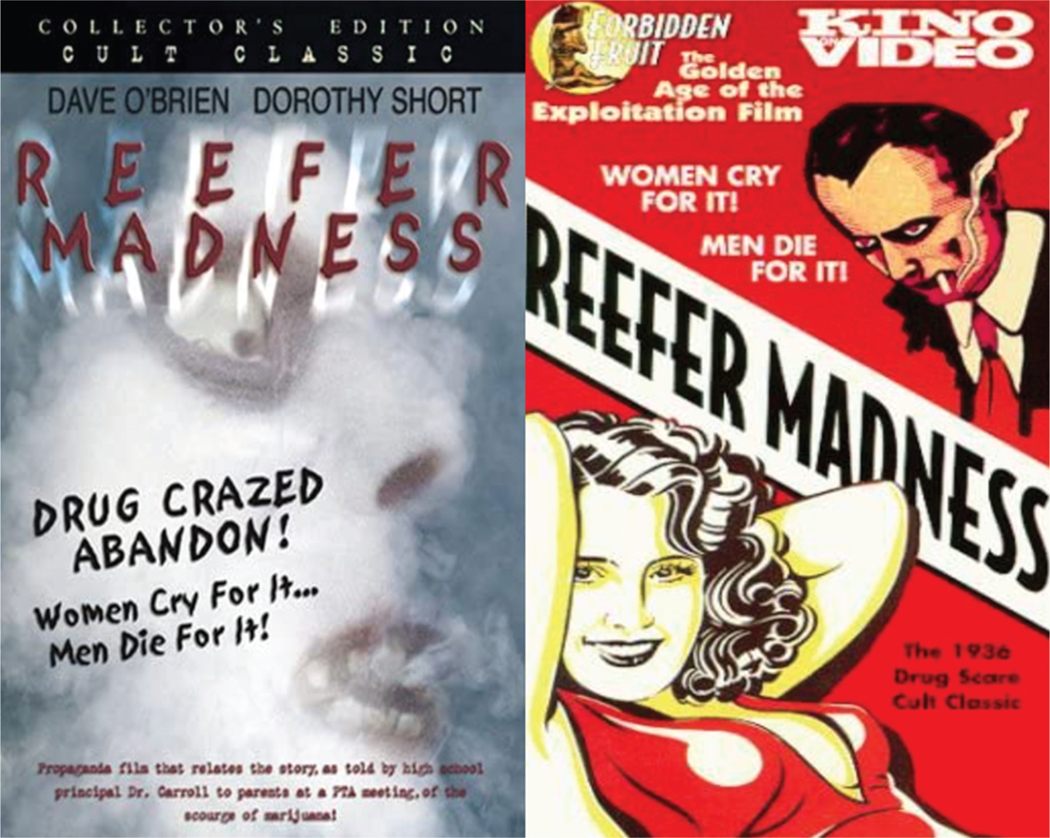

Despite garnering little attention before 1936, the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics Harry Anslinger promoted a shift in public opinion against cannabis use by perpetuating dramatized stories about cannabis use contributing to violent crimes and causing psychosis (63–65). Reefer Madness was an anti-drug film (Figure 3) that portrayed cannabis use as a “menace” worse than opium or heroin (66,67). In addition, cannabis was called “marihuana” to perpetuate the narrative that the drug was foreign and of dangerous Mexican origin (66). This sensationalist media reporting has recently been challenged due to data speaking toward low cannabis use among people immigrating from Mexico (68). Cannabis was used again to dehumanize individuals during the Vietnam War, portrayed as rebellious “hippies” and dropouts ruined by cannabis use (13,69–71). As such, the trope of cannabis inciting violence was replaced by news articles claiming that cannabis deflates people’s personalities and makes people more robotic (72). Like in the case of heroin, according to the Harper’s Magazine report, Nixon’s administration associated “hippies” with cannabis and heavily criminalized cannabis use to justify the arrests and vilification of antiwar leaders by the media since the administration could not criminalize anti-war sentiment (21). Negative content on cannabis use continued in the media until around the 1990s when cannabis began gaining wider support for legalization (66,73,74).

Figure 3.

Imagery associated with cannabis use in the 1936 film Reefer Madness (67).

Designer drugs

Recent designer drugs that caused moral panics were synthetic cathinones (i.e., bath salts) in 2010, MDMA (i.e., ecstasy or Molly) in 2013, and synthetic cannabinoids to the present day (75). Designer drugs have been disparaged for debasing humanity by offering an escape from reality (52). Designer drugs were linked to metaphors of remorseless, violent, and terrifying freaks; like methamphetamine, another synthetic drug called phencyclidine (PCP or “horse tranquilizer”) was associated with zombie imagery (52). Frankenstein imagery was particularly potent based on the idea of scientific experimentation creating monsters rather than improving humanity (52). Empirical studies later evaluated people who use ecstasy negatively, arguing that ecstasy use is linked to crime and breaks down people’s high self-control to induce aggressiveness (76,77). Stories about monsters using drugs who go berserk and commit extreme acts of violence faced little challenge due to the “near-total chemical illiteracy of legislators and media personnel” (52).

Recently, alleged benefits of novel designer drugs have spread faster than evidence-based harms, but this so-called “honeymoon period” seems to be ending for synthetic cannabinoids and bath salts (45). Johnston et al. (45) found that synthetic cannabinoid use decreased from 11.3% to 3.7% of high school seniors between 2012 and 2017, but upticks in certain states are still being declared “zombie” outbreaks (78). Flakka, a second-generation bath salt, is similarly called a “zombie” or “cannibal” drug due to the strange and violent actions described in popular news stories about people who were incorrectly believed to have bath salts in their system (79,80). Interestingly, Palamar (80 found that people at nightclubs use Molly instead of bath salts claiming that they are not zombies or cannibals and Molly is safer; they also unknowingly use bath salts, for example, in impure Molly, so drug purity testing might be an effective harm reduction strategy (80). Similar to how people who use meth choose to do so alone due to stigma, according to Elliot et al. (81), people who use bath salts face a similar dilemma between perceived social status and safety.

Discussion

America has been at war with drugs and the people who use them. Often, scientists have insufficiently challenged and have even given rise to the popularization of myths and stereotypes. Media workers lack expertise on drug use, and sensationalist stories sell. This has led the media to run with dehumanizing stories without asking the hard questions. Consequently, people who use drugs have been portrayed as one of the “least warm and competent groups” and thus denied humanity (82).

Dehumanization and stigma are significantly correlated (83). The U.S. government’s review of the literature has found stigmatizing anti-drug scare tactics ineffective (84). It remains difficult to view previously stigmatized groups as real people and reconstruct social ties with them (85). Stigmatized individuals are excluded from effective treatment and are subject to human rights abuses (86), which leads to healthcare avoidance (11). Stigma is associated with higher psychiatric morbidity (87) and treatment dropout (88) as well as lower medication adherence (89), quality of life (90), and belief in recovery (91). Dehumanization is also linked to objectification, support for harsher punishments, acceptance of discrimination, and lower recognition of suffering (5).

Empathetically connecting with others requires rehumanization: the recategorization of outcasts as fellow humans, appreciation for the same capacities of mind such as thought and emotion, and attribution of warmth and competence (82). Humanizing people with behavioral health conditions improves health outcomes, such as through increased help-seeking (92). Moreover, positive media portrayals can help engender positive evaluations, empathy, and a common identity (16,93,94). In Australia, for instance, the Mindframe for Alcohol and Other Drugs project developed guidelines and training for media professionals to achieve these goals by responsibly portraying PWUD, which could help inform the approach taken in the United States (95). There is little definitive evidence about a shift in American portrayals of most drug use. However, the media is portraying cannabis use more positively (96), and responsibility for opioid use disorder has shifted more toward opioid suppliers and Big Pharma (12). Although the direct detriment of stigmatizing media portrayal such as lower help-seeking has been established in some cases (17,57,60), this remains an area for future research.

Conclusion

The recurrent dehumanization of people who use drugs has typically been racially and socioeconomically motivated. Dehumanization contributes to stigma and worse treatment of people who use drugs in healthcare and society. Shifting media away from dehumanizing people who suffer from addiction is an obvious first step to rehumanization and better health outcomes. Future research should refine the detection of dehumanizing language and demonstrate the improvement in treatment-seeking and healthcare delivery as stigmatizing barriers are mitigated.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors report no relevant disclosures. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haslam N. Dehumanization: an integrative review. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2006;10:252–64. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendelsohn J, Tsvetkov Y, Jurafsky D. A framework for the computational linguistic analysis of dehumanization. Front Artif Intell. 2020;3. doi: 10.3389/frai.2020.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman GD, Haidt J. Cuteness and disgust: the humanizing and dehumanizing effects of emotion. Emot Rev. 2011;3:245–51. doi: 10.1177/1754073911402396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haslam N, Stratemeyer M. Recent research on dehumanization. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016;11:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haque OS, Waytz A. Dehumanization in medicine. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2012;7:176–86. doi: 10.1177/1745691611429706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kersbergen I, Robinson E. Blatant dehumanization of people with obesity. Obesity. 2019;27:1005–12. doi: 10.1002/oby.22460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szasz TS. Ideology and insanity: essays on the psychiatric dehumanization of man. London: Calder & Boyars; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, Morgan C, Rüsch N, Brown JSL, Thornicroft G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45:11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byrne SK. Healthcare avoidance. Holist Nurs Pract. 2008;22:280–92. doi: 10.1097/01.HNP.0000334921.31433.c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown TR. The role of dehumanization in our response to people with substance use disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:1–3. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinarman C. The Social Construction of Drug Scares. In: Adler PA, Adler P, editors. Constructions of Deviance: Social Power, Context, and Interaction. 1st ed. Belmont (CA): Wadsworth Publishing Company; 1994:155–65. [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Sentencing Commission. Cocaine and federal sentencing policy. Washington, DC: Author; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murji K. The agony and the ecstasy: drugs, media and morality. In: Coomber R, editor. The Control of drugs and drug users: reason or reaction. London (EN): Harwood Academic Publishers; 1998:69–85 . [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sumnall H, Atkinson A, Gage S, Hamilton I, Montgomery C. Less than human: dehumanisation of people who use heroin. Health Educ. 2021;121:649–69. doi: 10.1108/HE-07-2021-0099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh W, Copes H, Linnemann T. Creating visual differences: methamphetamine users perceptions of anti-meth campaigns. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;39:52–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furst RT, Johnson BD, Dunlap E, Curtis R. The stigmatized image of the “‘crack head’”: a sociocultural exploration of a barrier to cocaine smoking among a cohort of youth in New York City. Deviant Behav. 1999;20:153–81. doi: 10.1080/016396299266542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Netherland J, Hansen HB. The war on drugs that wasn’t: wasted whiteness, “Dirty Doctors,” and race in media coverage of prescription opioid misuse. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2016;40:664–86. doi: 10.1007/s11013-016-9496-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore LD, Elkavich A. Who’s using and who’s doing time: incarceration, the war on drugs, and public health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:S176–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.98.Supplement_1.S176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baum D. Legalize it all: how to win the war on drugs. Harper’s Mag. 2016;22–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, Gollust SE, Ensminger ME, Chisolm MS, McGinty EE. Social stigma toward persons with prescription opioid use disorder: associations with public support for punitive and public health-oriented policies. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68:462–69. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith DE. Medicalizing the opioid epidemic in the U.S. in the era of health care reform. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49:95–101. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2017.1295334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stock K. Wall street drug use: employees giving up cocaine for pot and pills. The Wall Street Journal. 2010. Aug 20. https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-DLB-26074 [accessed 10 Jan 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinarman C, Levine HG. Crack in context: America’s latest demon drug. In: Reinarman C, Levine HG, editors. Crack in America: Demon drugs and social justice. 1st ed. Berkley (CA): University of California Press; 1997:18–51 . [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crane M. Slang and nicknames for cocaine. American Addiction Centers. 2022. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/cocaine-treatment/slang-names [accessed 10 Jan 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexander M. The New Jim Crow. New York, NY: The New York Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Logan E. The wrong race, committing crime, doing drugs, and maladjusted for motherhood: the Nation’s Fury over “Crack babies. Soc Justice. 1997;26:115–38. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMillan J. How the media portrays black and white drug users differently. Salon. 2018. May 27. https://www.salon.com/2018/05/27/how-the-media-portrays-black-and-white-drug-users-differently/ [accessed 10 Jan 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egan J. Children of the opioid epidemic. NY Times Mag. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards E. Cocaine true, cocaine blue. New York, USA: Aperture; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staples B. Coke wars. New York Times. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Summary of findings from the 1998 National Household survey on drug abuse. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartley RD, Miller JM. Crack-ing the media myth: reconsidering sentencing severity for cocaine offenders by drug type. Crim Justice Rev. 2010;35:67–89. doi: 10.1177/0734016809348359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cole D. Denying felons vote hurts them, society. USA Today. 2000;A17. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taxy S, Samuels J, Adams W. Drug offenders in federal prison: estimates of characteristics based on linked data. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiricos T. Media, moral panics and the politics of crime control. In: Cole G, Gertz M, Bunger A, editors. Criminal justice system: politics and policies. 7th ed. Eagen (MN): West Publishing Company; 1998:58–75. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inciardi JA, Pottieger AE, Surrat HL. African Americans and the crack-crime connection. In: Chitwood D, Inciardi J, and Rivers J, editors. The American pipe dream: crack cocaine and the inner city. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace College Publishers; 1996:56–70 . [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volkow N. Punishing drug use heightens the stigma of addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2021. https://nida.nih.gov/about-nida/noras-blog/2021/08/punishing-drug-use-heightens-stigma-addiction [accessed 10 Jan 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hatsukami DK, Fischman MW. Crack cocaine and cocaine hydrochloride: are the differences myth or reality? J Am Med Assoc. 1996;276:1580–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540190052029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.United States Sentencing Commission. Cocaine and federal sentencing policy. Washington, DC: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.United States Sentencing Commission. Report to the congress: cocaine and federal sentencing policy. Washington, DC: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.United States Sentencing Commission. Cocaine and federal sentencing policy. Washington, DC: Author; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rasmussen N. On speed: the many lives of amphetamine. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2018: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwartz C. Generation adderall. NY Times Mag. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A. Prescription stimulants in individuals with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: misuse, cognitive impact, and adverse effects. Brain Behav. 2012;2:661–77. doi: 10.1002/brb3.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Partridge BJ, Bell SK, Lucke JC, Yeates S, Hall WD, Ross JS. Smart drugs “As common as coffee”: media hype about neuroenhancement. PLoS One. 2011;6: e28416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World drug report. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hunt D, Kuck S, Truitt L. Methamphetamine use: lessons learned. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toothless Murakawa N.. Du Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race. 2011;8:219–28. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jenkins P. Synthetic panics: the symbolic politics of designer drugs. New York, NY: New York University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Linnemann T, Wall T. ‘This is your face on meth’: the punitive spectacle of ‘white trash’ in the rural war on drugs. Theor Criminol. 2013;17:315–34. doi: 10.1177/1362480612468934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Linnemann T. Mad men, meth moms, moral panic: gendering meth crimes in the midwest. Crit Criminol. 2010;18:95–110. doi: 10.1007/s10612-009-9094-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foundation for a drug-free world. A worldwide epidemic of addiction. [accessed 2022 Nov 28]. https://www.drugfreeworld.org/drugfacts/crystalmeth/a-worldwide-epidemic-of-addiction.html .

- 56.Faces of Meth. [accessed 2022 Nov 28]. https://facesofmeth.us/ .

- 57.McKenna S. “The meth factor”: group membership, information management, and the navigation of stigma. Contemp Drug Probl. 2013;40:351–85. doi: 10.1177/009145091304000304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mitchell WT. Picture theory: essays on verbal and visual representation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Erceg-Hurn DM. Drugs, money, and graphic ads: a critical review of the Montana Meth Project. Prev Sci. 2008;9:256–63. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0098-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Halkjelsvik T, Rise J. Disgust in fear appeal anti-smoking advertisements: the effects on attitudes and abstinence motivation. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2015;22:362–69. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2015.1015491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.South Dakota Department of Social Services. [accessed 2022 Nov 28]. https://onmeth.com/ .

- 62.Kesslen B. South Dakota’s “Meth. We’re on it.” Campaign is funny but state officials say the meth problem is deadly serious. NBC News. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hari J. Chasing the scream: the first and last days of the war on drugs. London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury USA; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anslinger H, Cooper C. Marijuana: Assassin of youth. Am Mag. 1937;124:150–53. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carroll R. Under the influence: Harry Anslinger’s role in shaping America’s drug policy. In: Spillane Erlen J J, editors. Federal drug control: the evolution of policy and practice. Bingham, NY: Haworth Press; 2004. pp. 61–99. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stringer RJ, Maggard SR. Reefer Madness to Marijuana Legalization. J Drug Issues. 2016;46:428–45. doi: 10.1177/0022042616659762 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gasnier LJ. Reefer madness. IMDb;1936. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mexicans Campos I. and the origins of Marijuana prohibition in the United States: a reassessment. Soc Hist Alcohol Drugs. 2018;32:6–37. doi: 10.1086/SHAD3201006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dickson DT. Bureaucracy and Morality: an organizational perspective on a moral Crusade. Soc Probl. 1968;16:143–56. doi: 10.2307/800000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Becker HS. Outsiders: studies in the sociology of deviance. Vol. 56. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Himmelstein JL. The strange career of Marihuana: politics and ideology of drug control in America. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Holden D. Drugs: the dehumanization of pot smokers. The Stranger. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nielsen AL. Americans’ attitudes toward drug-related issues from 1975–2006: the roles of period and cohort effects. J Drug Issues. 2010;40:461–94. doi: 10.1177/002204261004000209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Millhorn M, Monaghan M, Montero D, Reyes M, Roman T, Tollasken R, Walls B. North Americans’ attitudes toward illegal drugs. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2009;19:125–41. doi: 10.1080/10911350802687075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taylor J. The stimulants of prohibition: illegality and new synthetic drugs. Territ Polit Gov. 2015;3:407–27. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2015.1053516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reid LW, Elifson KW, Sterk CE. Hug drug or thug drug? Ecstasy use and aggressive behavior. Violence Vict. 2007;22:104–19. doi: 10.1891/vv-v22i1a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vaughn MG, Salas-Wright CP, DeLisi M, Perron BE, Cordova D. Crime and violence among MDMA users in the United States. AIMS Public Heal. 2015;2:64–73. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2015.1.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adams AJ, Banister SD, Irizarry L, Trecki J, Schwartz M, Gerona R. “Zombie” outbreak caused by the synthetic cannabinoid AMB-FUBINACA in New York. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:235–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Palamar JJ Flakka is a dangerous drug, but it doesn’t turn you into a zombie. Conversat. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Palamar JJ. “Bath salt” use and beliefs about use among electronic dance music attendees. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2018;50:437–44. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2018.1517229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Elliott L, Benoit E, Campos S, Dunlap E. The long tail of a demon drug: the ‘bath salts’ risk environment. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;51:111–16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fiske ST. From dehumanization and objectification to rehumanization. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1167:31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04544.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Boysen GA, Isaacs RA, Tretter L, Markowski S. Evidence for blatant dehumanization of mental illness and its relation to stigma. J Soc Psychol. 2020;160:346–56. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2019.1671301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.SAMHSA. Using fear messages and scare tactics in substance abuse prevention efforts. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weinstein HM, Halpern J. Rehumanizing the other: empathy and reconciliation. Hum Rights Q. 2004;26:561–83. doi: 10.1353/hrq.2004.0036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mfoafo-M’carthy M, Huls S. Human rights violations and mental illness. SAGE Open. 2014;4:215824401452620. doi: 10.1177/2158244014526209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, van Brakel W, C Simbayi L, Barré I, Dovidio JF. The health stigma and discrimination framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17:31. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Britt TW, Jennings KS, Cheung JH, Pury CLS, Zinzow HM. The role of different stigma perceptions in treatment seeking and dropout among active duty military personnel. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38:142–49. doi: 10.1037/prj0000120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1615–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cheng C-M, Chang C-C, Wang J-D, Chang K-C, Ting S-Y, Lin C-Y. Negative impacts of self-stigma on the quality of life of patients in methadone maintenance treatment: the mediated roles of psychological distress and social functioning. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1299. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Understanding stigma of mental and substance use disorders. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press;. End. Discrim. Against People with Ment. Subst. Use Disord. Evid. Stigma Chang.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martinez AG. When “They” become “I”: ascribing humanity to mental illness influences treatment-seeking for mental/behavioral health conditions. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2014;33:187–206. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2014.33.2.187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Haslam N, Loughnan S. Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:399–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Capozza D, Trifiletti E, Vezzali L, Favara I. Can intergroup contact improve humanity attributions? Int J Psychol. 2013;48:527–41. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.688132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mindframe. Communicating about alcohol and other drugs. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chiu V, Leung J, Hall W, Stjepanović D, Degenhardt L. Public health impacts to date of the legalisation of medical and recreational cannabis use in the USA. Neuropharmacology. 2021;193:108610. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]