Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of six weeks of routine use of a novel robotic transfer device, the AgileLife Patient Transfer System, on mobility-related health outcomes, task demand, and satisfaction relative to previous transfer methods.

Materials and Methods:

Six end users and five caregivers used the system in their homes for six weeks. Participants completed several surveys examining perceived demands related to preparing and performing a transfer and mobility-related health outcomes pre and post intervention. Participants were also asked about their satisfaction with using the technology compared to previous transfer methods.

Results:

Both end users and caregivers reported reduction in perceived physical demand (p = 0.007) and work (p ≤ 0.038) when preparing for and performing a transfer. End users indicated that the device intervention had a positive impact, indicating some improvements to health-related quality of life as well as improved competence, adaptability, and self-esteem post-intervention. All participants were highly likely to recommend the technology to others.

Conclusion:

The AgileLife Patient Transfer System is a promising new form of transfer technology that may improve the mobility and mobility-related health of individuals with disabilities and their caregivers in home settings.

Keywords: Biomedical technology assessment, wheelchairs, caregivers, assistive technology

Introduction

Mobility plays an important role in an individual’s physical and mental health and can predict both quality of life and health outcomes in aging populations [1]. Individuals with less mobility have an increased risk of falls, more difficulty accessing healthcare providers, and increased psychological stress, amongst several other negative health outcomes, including but not limited to pressure injuries, metabolic decline, muscle atrophy, and microvascular dysfunction [1,2]. They often require assistance for activities of daily living, including transferring from bed to wheelchair and wheelchair to bed. While essential for independence, these activities may put both the caregiver and care recipient at potential risk for further injury [3,4]. Transfers can be physically demanding for individuals with limited mobility and can cause a lack of feeling independent, which can cause resistance towards transfer activities [5].

Caregivers often provide assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), including tasks that involve assisting with transfers, like bathing, getting in and out of a bed, and transferring to a toilet. Approximately 43% of caregivers assist with transfer-related tasks in a home setting [6]. However, caregivers who assist with transfers are at a high risk for developing musculoskeletal pain and injury [7]. Prior research has shown that 43.4% of all developed musculoskeletal injuries in caregivers occur due to transfer-related activities, such as lifting and transferring a care recipient [8]. The frequency and duration of transfers and lifting activities, like repositioning, has been associated with increased risk of injury in rehabilitation professionals [9,10]. In a recent study of informal (i.e., non-paid) caregivers, transfers were identified as the most physically demanding task performed [7]. In addition to the physical stress experienced during transfers, 45% of individuals providing care to an individual with a long-term physical disability also experience high levels of emotional strain [11]. High levels of physical and emotional exertion impact a care provider’s ability to perform transfer tasks safely and effectively [12].

Clinical settings are equipped with assistive technology to reduce workload for both caregivers and care recipients during transfers. However, lift devices are not always immediately available, convenient, or intuitive to use [13,14]. Mechanical lifts, such as ceiling lifts and floor lifts, are a common solution in home care settings but are very difficult to install and may require structural modifications the home [13]. They require person handling in order to position the sling under the person, which can be difficult for the caregiver and uncomfortable for the person being assisted and require the person being assisted to be suspended in the air, increasing anxiety [3]. Operation of lift devices in a home setting can be difficult to use and manoeuvre in confined or tight spaces and requires awkward manipulation of the care recipient [14]. Although mechanical transfer devices are shown to improve people’s feelings of safety and security [15], they still do not completely solve the issues involved with person transfer, especially for individuals living in residential settings. In a recent survey of over one thousand mobility-assistive technology users, better transfer devices were identified as an area of critical importance, indicating the need for additional research and development of these technologies [16].

The AgileLife Patient Transfer System (PTS) developed by NextHealth LLC is a commercially available, novel transfer technology that requires no manual lifting or repositioning when performing a bed to wheelchair transfer. The system uses a series of actuators and a conveyor to transfer the user from bed to chair and vice versa and is fully operational via the use a tablet. Through the use of a no-lift system, the strenuous activities associated with performing bed to wheelchair transfers may be reduced for both the care recipient and caregiver. During the development of the AgileLife PTS, feedback on its design was provided by both caregivers and assistive technology users [2]. Previous research showed that rehabilitation professionals rated the AgileLife PTS more favourably than other transfer devices in terms of caregiver safety, end-user safety, ease of operation, timeliness, and overall functionality [2]. However, little is known about how the routine use of the AgileLife PTS effects both caregivers and care recipients in a home setting. The purpose of this study was to (1) determine changes in task demand and satisfaction when using the AgileLife PTS compared to previous transfer methods and (2) examine the effects of six weeks of in-home use of the AgileLife Patient Transfer System on device user mobility-related health and quality of life.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Individuals with difficulty transferring in and out of bed were recruited for this study along with their caregivers. Participants were recruited from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania through flyers posted in local rehabilitation clinics and on social media as well as through local research registries targeting assistive technology users. Interested participants contacted the study team and were screened for initial eligibility. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for end users included (1) difficulty getting into and out of bed (2) over 18 years old (3) able to tolerate sitting upright in a wheelchair for at least 1 h (4) weighing less than 350 pounds (158 kg) and fit within the dimensions of the PTS wheelchair frame (5) did not require specialised postural supports and (6) able to fit the AgileLife PTS in their home. Caregivers who provided care to end users were enrolled in the study if they (1) were 18 years of age or older, (2) provided transfer assistance to the individual at least 3 days a week and (3) had no reported lower back pain that may be exacerbated by performing transfers.

Description of the AgileLife patient transfer system

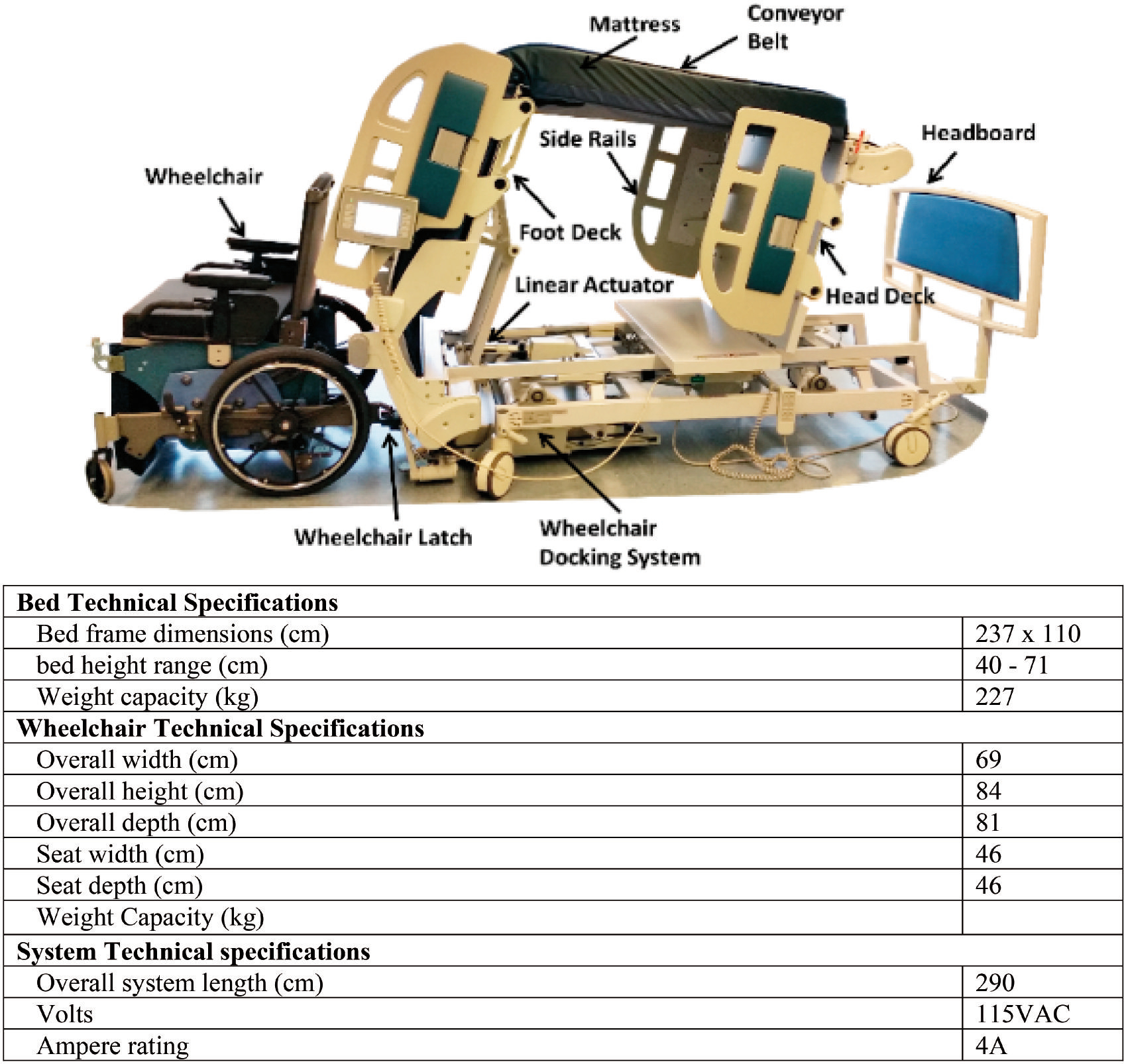

The AgileLife Patient Transfer System (PTS) is composed of a hospital bed with a wheelchair docking station and a custom wheelchair, as shown in Figure 1. The custom manual wheelchair accompanying the hospital bed included features such as a weight capacity of 350 lbs (159 kg), an integrated bed-side commode option, and manual tilt-in-space capabilities to accommodate a wide variety of users. The hospital bed comes with a sheet that attaches to rollers at the top and bottom of the bed, allowing for movement of the sheets up and down the bed. Custom made linens attach to that sheet. To prepare for a transfer, the caregiver must bring the wheelchair to the docking station at the foot of the bed and latch it into the docking station. The system is controlled via a handheld pendant, which displays the primary user interface (PUI). The caregiver holds down the “Transfer to bed” button on the PUI to initiate a transfer. The docking station pulls the wheelchair closer to the bed while the mattress rises and folds to meet the back of the chair. The system prompts the caregiver to manually lower the back of the chair and the mattress supports the end-user’s back. Once the care recipient is in the correct position, the seat of the wheelchair rotates backward as the bed begins to lower and flatten and a conveyer gently pulls the person onto the bed. The system stops upon sensing that the person’s feet have passed the foot of the bed. A video of the transfer process can be seen in the Supplementary Materials. The process proceeds in reverse when the caregiver holds the “Transfer to chair” button on the PUI. The system can be paused at any time by releasing hold of the button on the PUI. Transfers require no lifting and can be completed in 90 s. The PUI provides the caregiver or end-user the ability to adjust bed height, head and foot position, and sheet position. Additional information on the specifications of the AgileLife PTS can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The AgileLife Patient Transfer System and relevant specifications.

Experimental protocol

Home evaluation

End users that were deemed eligible through the screening process were scheduled for a home evaluation. Before evaluating the home, they were asked to provide written informed consent. An in-person assessment was done of the participants home to ensure that the AgileLife PTS would fit and could be safely operated. After determining that the device could be used safely, end users were asked to obtain a physician’s release stating they were healthy enough to participate in the study and to identify up to three caregivers who provided transfer assistance to participate in the study. Interested caregivers who met the inclusion criteria also provided written informed consent before the study began. Upon receipt of a physician’s release for end user participants and consent of all interested caregivers, a baseline visit and system install were scheduled.

Baseline visit.

End users and caregivers were asked to complete a demographics survey and task demand questionnaire, called the Transfer Task Evaluation survey, to assess their workload when preparing for and performing bed to wheelchair transfers. The questionnaire was based on the NASA Task Load Index, and like the NASA Task Load Index, asked participants to gauge their mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, performance, effort, and frustration [17]. An additional question was added to the Transfer Task Evaluation that was not part of the NASA Task Load Index that asked participants to rate their feelings of safety. The questionnaire used a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS), where 0 indicated “very low” and 10 indicated “very high”.

End users were asked to complete the Individually Prioritised Problem Assessment (IPPA) and Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) [18,19]. The IPPA is an instrument used to assess the effectiveness of an assistive technology provision by identifying specific problems that the assistive technology has the potential to address and individual considers important. At the start of an intervention, the individual is asked to identify up to seven problems that they perceive themselves to have difficulty performing and rate the difficulty of each task on a scale of 1 (not very difficult) to 5 (extremely difficult) and the importance of each task on a scale of 1 (not very important) to 5 (extremely important), with mean scores ranging from 0 (not very difficult and not very important) to 25 (extremely difficult and extremely important) [18]. The same activities are rated again after the intervention. The SF-36 is a patient-reported outcome measure that quantifies and measures health-related quality of life. It consists of 36-items divided into eight subscales, which are physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, role limitations due to emotional problems, energy and fatigue, emotional well-being, social functioning, pain, and general health. Each of the eight subscales is scored on a scale of 0 (negative health) to 100 (positive health), which can be used independently to observe change in health-related quality of life over time. A change in SF-36 subscale of at least 10-points was established as the threshold for a minimal clinically important difference (MCID), as determined by prior research [20].

After completing the initial group of surveys and questionnaires the equipment was installed and the users and their primary caregivers were trained on how to use the system. Two separate training sessions were provided to participants. The first training session involved using the basic bed functions and a second training session involved use of the transfer functions. Participants were asked to perform a transfer in front of the study team to ensure they understood how to use the system effectively. Additionally, all participants were left with a device manual and access to a 24-h help hotline that they could call for technical assistance. The study team contacted participants at one day and again one week after the device install to ensure the device was working properly and address any questions.

Followup visit.

The same series of questionnaires that were administered at baseline were administered at the end of the six-week intervention period. End users also filled out the Psychosocial Impact of Assistive Devices (PIADS). The PIADS is a measure of the impact of an assistive device on several aspects related to wellbeing and is broken up into 3 subscales that measure competence, adaptability, and self-esteem. Individuals score each category from −3 to 3, with −3 indicating maximum negative impact and 3 indicating maximum positive impact. Additionally, both end users and caregivers filled out the Patient Transfer System Evaluation. The PTS evaluation used a 10 cm VAS and asked each user three questions. Participants were asked to mark on the line to indicate their response. The first question asked users how well the PTS accommodated their seating and mobility needs with 0 being “not at all” and 10 being “extremely well”. The second question asked how the PTS compares to previously used transfer methods based on a series of metrics with 0 indicating “much worse”, 5 indicating “equal to”, and 10 indicating “much better”. Finally, the third question asked how likely the user is to recommend the PTS to others with 0 being “not likely” and 10 being “very likely”. Participants were also able to provide open ended feedback on their experiences with the robotic assistive transfer device.

Data analysis

Scoring was done according to the instructions of the specific questionnaires. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and standard errors of the mean, were calculated. Due to the small sample size and low power of the study, results were also compared to the MCID of the SF-36 to evaluate clinical significance. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni post-hoc correction was used to compare SF-36, IPPA, and task demand scores for end users and caregivers pre and post intervention. End user and caregiver groups were combined for task demand analysis. The level of significance was set to an alpha of 0.05. All statistical analysis was performed in SPSS Version 26 (IBM).

Results

Participants

Eight end users and seven caregivers were enrolled in the study. One user and caregiver dyad were withdrawn from the study because they did not feel they could transfer to the bed effectively. One caregiver was lost to follow up after changing care agencies during the duration of the study. Finally, one device user was withdrawn from the study due to pain while sleeping in the AgileLife PTS after an unexpected surgery. The data analysis includes six end users and five caregivers. End users self-reported a wide variety of disability aetiologies, including stroke, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, thoracic and cervical spinal fusion, and spina bifida. They used a variety of assistive devices to assist with mobility, including power wheelchairs (66.7%) manual wheelchairs (50%), canes (50%), scooters (33.3%), and walkers (33.3%), with 4 of the 6 participants reporting using at least two assistive devices to assist with mobility and transfers. Three caregivers provided care to family members and two were paid care attendants providing care to a client. Two end users did not have a caregiver who assisted them with transfers regularly. The group mean (± standard deviation) of age, height, and weight and reported gender, race, and transfer method for the users and caregivers can be seen in Table 1. Additional information about each care recipient and caregiver can be found in the Supplementary materials.

Table 1.

Demographics for end users and caregivers.

| End user (n = 6) | Caregivers (n = 5) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (years) | 54.8 (15.1) | 46.6 (21.0) |

| Range (years) | 39 – 83 | 18 – 76 |

| Gender | ||

| Male (%) | 3 (50%) | 1 (20%) |

| Female (%) | 3 (50%) | 4 (80%) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian (%) | 3 (50%) | 3 (60%) |

| African American (%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (40%) |

| Weight (kg) | 90.9 (32.7) | 77.3 (21.2) |

| Range (kg) | 59 – 43 | 45 – 99 |

| Height (cm) | 163.4 (11.8) | 168.1 (7.9) |

| Range (cm) | 145 – 180 | 157 – 175 |

| Transfer method | ||

| Manual lift from caregiver (%) | 3 (50%) | |

| Independent with cane (%) | 2 (33.3%) | |

| Stand and pivot with walker and caregiver assistance (%) | 1 (16.7%) | |

Means (± standard deviations) and counts (percentages) are displayed where appropriate).

Task demand

At the end of the trial period, participants reported significantly less perceived physical demand when preparing for a transfer (p = 0.007) and performing a transfer (p = 0.007) (Table 2). Participants also reported significantly less perceived work when preparing for a transfer (p = 0.038) and performing a transfer (p = 0.008) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Average (± standard deviation) task demand scores when preparing for and performing transfers before and after routine use of the AgileLife Patient Transfer System.

| End users (n = 6) | Caregivers (n = 5) | Total (n= 11) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Baseline | Final | Baseline | Final | Baseline | Final | |

|

| ||||||

| Preparing for a transfer | ||||||

| Mental demand | 4.5 (4.1) | 1.4 (2.0) | 2.1 (4.1) | 1.5 (1.6) | 3.6 (4.1) | 1.5 (1.7) |

| Physical demand | 6.2 (3.5) | 1.6 (2.1) | 6.3 (3.9) | 2.2 (2.5) | 6.0 (3.5)** | 1.8 (2.2)** |

| Rushed | 2.8 (4.4) | 3.2 (3.9) | 2.4 (2.5) | 1.9 (1.7) | 2.6 (3.5) | 2.6 (3.1) |

| Success | 6.3 (3.8) | 8.4 (2.2) | 6.8 (2.3) | 9.3 (0.7) | 6.4 (3.2) | 8.8 (1.7) |

| Amount of work | 5.5 (4.7) | 2.5 (3.0) | 4.9 (3.4) | 3.3 (4.2) | 5.4 (4.0)* | 2.8 (3.4)* |

| Stress | 6.2 (4.9) | 5.0 (4.3) | 2.7 (3.8) | 2.1 (2.9) | 4.5 (4.8) | 3.6 (3.9) |

| Safety | 5.9 (2.6) | 8.0 (3.2) | 6.8 (3.2) | 7.7 (4.2) | 6.2 (3.0) | 7.8 (3.5) |

| Performing a bed to wheelchair transfer | ||||||

| Mental demand | 5.7 (4.3) | 3.1 (4.0) | 2.4 (2.5) | 1.0 (1.1) | 3.7 (3.7) | 3.2 (3.5) |

| Physical demand | 7.4 (4.1) | 2.9 (4.0) | 6.9 (3.8) | 1.8 (2.4) | 6.8 (3.8)** | 1.7 (2.0)** |

| Rushed | 2.6 (4.2) | 1.1 (2.0) | 2.4 (2.7) | 2.0 (1.8) | 2.5 (3.5) | 2.2 (3.0) |

| Success | 8.3 (2.9) | 6.8 (4.0) | 7.9 (2.1) | 8.8 (0.7) | 8.1 (2.5) | 8.1 (2.8) |

| Amount of work | 6.7 (4.4) | 2.9 (2.7) | 4.5 (3.6) | 1.6 (2.0) | 5.6 (4.0)** | 2.3 (2.5)** |

| Stress | 6.0 (4.7) | 3.6 (4.1) | 3.1 (3.7) | 2.0 (3.1) | 4.6 (4.3) | 2.3 (2.8) |

| Safety | 7.5 (3.2) | 7.2 (2.9) | 8.1 (1.9) | 9.1 (0.9) | 7.9 (2.3) | 8.6 (2.2) |

p ≤ 0.05

p ≤ 0.01.

Device user mobility-related outcomes

No significant differences were found between baseline and post-intervention SF-36 and IPPA scores (p > 0.05) (Table 3). Participants reported improvements in their health-related quality of life in terms of role limitations due to physical and emotional health above MCID thresholds. However, they reported a clinically meaningful decrease in social functioning during the intervention. Users reported a positive impact with the assistive technology, reporting a decrease in mean IPPA scores post-intervention and indicating a positive impact for competence, adaptability, and self-esteem on the PIADS scale (Table 3). Problems reported by participants in the IPPA that they anticipated the AgileLife PTS would improve included sleeping through the night (n = 3), transferring (n = 2), tasks related to self-care, including bathing and dressing (n = 2), indoor mobility (n = 1), and increased mobility when shopping (due to getting a more restful night sleep) (n = 1).

Table 3.

Mobility-related outcome measure scores for users before and after AgileLife PTS use. Mean (± standard deviation) and median values are displayed for all variables.

| Baseline | Post-intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Mean | Median | Mean | Median | |

|

| ||||

| IPPA | ||||

| Number of problems reported | 1.5 (1.2) | 1.0 | ||

| Mean IPPA Score | 20.6 (3.5) | 20.0 | 15.0 (6.7) | 15.5 |

| SF-36 | ||||

| Physical functioning | 10.8 (10.2) | 5.0 | 11.7 (16.9) | 2.5 |

| Role limitations due to physical health | 16.7 (20.4) | 0 | 33.3 (37.6) | 12.5 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 16.7 (40.8) | 0 | 38.9 (39.0) | 16.7 |

| Energy/Fatigue | 24.2 (29.9) | 7.5 | 31.7 (30.1) | 12.5 |

| Emotional well being | 46.0 (31.4) | 30.0 | 43.3 (31.5) | 28.0 |

| Social functioning | 47.9 (33.9) | 25.0 | 29.6 (26.5) | 12.5 |

| Pain | 34.9 (25.9) | 22.5 | 33.3 (21.1) | 17.5 |

| General health | 21.7 (27.3) | 2.5 | 29.3 (25.4) | 12.5 |

| PIADS | ||||

| Competence | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.9 | ||

| Adaptability | 1.6 (1.9) | 2.3 | ||

| Self-esteem | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.8 | ||

| Mean score | 1.6 (1.1) | 2.0 | ||

AgileLife PTS evaluation

Participants rated the PTS better than their previous transfer method in terms of safety, comfort, ease of operation, timeliness and overall functionality (Figure 2). End users also rated the system as slightly less able to meet their seating and mobility needs than caregivers, but both groups were highly likely to recommend the device to others (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient and caregiver perceptions of the AgileLife Patient Transfer System compared to their previous method of transfer on safety, comfort, ease of operation, timeliness, and overall functionality. The horizontal line depicts the value indicative of “equal to” the previous transfer method. Also shown are the average scores for how well the system met their seating and mobility needs and how likely they were to recommend the system to others.

A summary of the open-ended feedback provided by both end users and informal caregivers is shown in Table 4. Participants reported that the system operated well and that they felt safe when using the system. Additional areas for improvement were also noted, including the timeliness of completing a transfer, the size and configuration of the manual wheelchair, and additional time for users and caregivers to become acclimated with the technology.

Table 4.

Open ended feedback on the AgileLife Patient Transfer System from users and caregivers.

| End users |

| “The transfer functions sometimes took too long”. |

| “The wheelchair was too big and too wide to fit through doorways so I couldn’t use it”. |

| “The features of this bed are excellent for the safety of both the caregivers and the patients”. |

| “I don’t have a partner, so I need a manual chair that is self-operated”. |

| Caregivers |

| “The bed goes up and down and the sheets move a bit too slowly. If it were a little faster, it would be perfect”. |

| “The system was great, but my husband was not mentally prepared to work with the bed. Once he got in the bed, he slept well”. |

| “Once I got used to the system it worked well”. |

| “The bed worked very well. I felt very safe for him while using the system”. |

| “My back feels better”. |

| “Having a light on the pendant would make it easier to use”. |

Discussion

As the population ages and the desire to remain at home grows, there is an increased demand for technology that allows for safe and effective transfers in a home setting. In most home care settings, the use of assistive technology to assist with bed to wheelchair transfers is prohibitive, and manual lifting and moving of patients is common [21]. The purpose of this study was to explore potential benefits to both end users and caregivers when using novel transfer technology in the home, which may mitigate common issues surrounding caregiver and care recipient safety during manual transfers, including musculoskeletal pain and injuries. A strength of this study is that it evaluates extended use of a novel robotic transfer technology in the home. Several robotic transfer systems have been developed however none of them have been formally evaluated outside of a lab or clinical setting [22]. Additionally, the majority of studies examining transfer assist systems focus on caregiver injury prevention and well-being, but ignore the end user perspective [22]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the usability of a robotic transfer system in a home setting from both the caregiver and end user perspective. Overall, both end users and caregivers had favourable opinions on the AgileLife PTS. The quantitative and qualitative results from this study indicate that use of the AgileLife PTS may help reduce physical and cognitive demand associated with performing bed to wheelchair transfers in home-care settings.

End users and caregivers reported decreases in their perceived physical demand and work when using the AgileLife PTS in their homes. This may be because the AgileLife PTS involves a no-lift solution for transfers, decreasing physical demand when preparing for and performing transfers. The sheet up and down function also allows the caregiver to reposition the end user up and down on the mattress without manual lifting. Repositioning an individual in bed, which often happens at the end of a wheelchair to bed transfer, has been shown to be highly physically demanding, often causing musculoskeletal pain and injury [23]. Additionally, manual repositioning techniques that can cause pain and injury are more likely to be used in a home setting than a clinical setting due to financial and space limitations involved with implementing assistive technology in home settings [21]. By automating the repositioning process, the AgileLife PTS may be able to reduce physical strain during both transfers and repositioning tasks. As a result this system carries the potential to reduce the incidence of musculoskeletal injuries and the physical demand that is experienced by both professional and informal caregivers [7,8]. Additionally, when an individual who requires assistance with transfers loses that support (e.g., an aging spouse) he/she is often referred to institutional care (e.g., nursing home). Providing an assistive technology solution that is easily implemented in home settings may allow individuals and their caregivers to stay in their homes longer and remain active members of their communities.

End users saw a reduction in IPPA scores and positive impact in PIADS scores after routine use of the AgileLife PTS. Both the PIADS and IPPA are user-centered measures of quality of life, meaning that they measure device acceptance based on the goals or values of an individual [18,24]. While end users identified a small number of problems that they thought would be improved via the assistive technology solution using the IPPA, they reported reduced difficulty of the identified tasks after intervention with the AgileLife PTS. Participants also indicated intervention with the AgileLife PTS improved feelings of competence, adaptability, and self-esteem. Higher positive PIADS scores have been associated with improved assistive device retention, indicating that the AgileLife PTS may be an appropriate long-term transfer technology solution [25]. Additionally, participants reported clinically significant improvements with certain domains of the SF-36, including role limitations due to physical health and role limitations due to emotional distress. The participants in this study rated their health-related quality of life as very low on many SF-36 subdomains, indicating more severe effects of disability. While mobility is not the only factor than affects these aspects of health-related quality of life, increased mobility may have contributed to the improvements. Mobility has been shown to predict changes in health-related quality of life in community-dwelling, older adults in prior studies, with higher mobility related outcomes being associated with a higher health-related quality of life [26]. Transfers have been shown to be both physically and emotionally stressful to care recipients [5]. Therefore, by improving the transfer process, care recipients may be less limited by their physical and emotional health status.

Despite differences in individual experiences, participants were likely to recommend the AgileLife PTS to others who they felt would be appropriate for the device. Most participants indicated that the system performed better than their previous transfer method in terms of safety, comfort, ease of operation, and overall functionality. In their open-ended feedback, participants indicated that the robotic device features were reliable and made them feel safer during the transfer process. However, participants also cited several areas for improvement. Timeliness of the transfer and sheet up and down functions was cited by multiple participants as an area for improvement. Participants also reported wanting additional time with the system to become more comfortable with the transfer process. Six weeks may not have been enough time to fully adjust to the AgileLife PTS, as participants were asked to use a new transfer method instead of the method that they were accustomed to using. Transfers are habitual in nature for both the care recipient and caregiver, and changes to these habits can take adjustment.

Overall, participants in this study indicated that they had a positive experience with the AgileLife PTS. This is encouraging given that negative outcomes including caregiver frustration, worry, and injury have been associated with the use of complex assistive technologies [27].

Limitations and future work

The primary outcome for this study, the Transfer Task Evaluation survey, was an adaptation of a questionnaire based on the NASA Task Load Index. While the items and response structure closely resemble the original instrument, the survey has not been validated. Additionally, data on daily and overall use of the system was not collected and should be considered when developing future studies around novel transfer technologies. None of the participants elected to use the chair that accompanied the AgileLife PTS for daily mobility over their existing wheeled mobility device. Therefore, the system did not completely eliminate transfers associated with wheelchair to bed movements, as participants still transferred from the seat of their mobility device to the PTS wheelchair. Transfers between two wheelchairs are generally more manageable than bed to wheelchair transfers, which require higher forces and skill to perform them successfully because the two surfaces are at different heights [28]. Of the six participants who completed this study, four were able to transfer independently and two required assistance from a caregiver and assistive technology (a walker or a cane) to transfer between wheelchairs. Future work should look into developing additional wheelchairs compatible with the system, such as manual wheelchairs where the user is able to self-propel or powered wheelchairs. Additionally, some of the participants in the study were power wheelchair users, and a compatible power wheelchair may have allowed them to avoid an extra transfer. Participants required varied levels of transfer assistance, ranging from independent with the use of a cane to completely dependent on caregiver assistance. Future work should also look at pressure distribution during transfers. Because the AgileLife PTS makes use of a novel conveyor system, little is known about the friction and shear a user experiences during transfers and repositioning tasks. While the system does have two mattress options, a standard mattress and a GRZ air pressure redistribution mattress, integration of additional therapeutic mattresses may further reduce the risk of pressure injuries for end users. Additionally, this study examined the perceptions of only a small number of participants who were eager to participate in research and lived in homes with enough space to accommodate the AgileLife PTS. Because participation in the study was dependent on the amount of space participants had available in their homes, selection bias may have factored into the results, as not all individuals who may be able to make use of this technology have the space to accommodate it in their homes. Enrolling more participants who require greater assistance for transfers may provide additional insight into how routine use of the AgileLife PTS affects mobility-related health outcomes of individuals and their caregivers living in the community.

Conclusion

Participants reported improvements in mobility-related health outcomes after six weeks of in-home use with the AgileLife PTS, including reductions in physical demands and work. Both users and caregivers had positive perceptions of the technology. Areas for improvement were noted, including the timeliness of the device, education and training associated with introducing novel technology, and more seating options to accommodate a wider variety of users. Participants were likely to recommend the device to others, demonstrating that the AgileLife PTS is a promising new form of transfer technology that has the ability to improve the mobility and mobility-related health of individuals with disabilities and their caregivers in community settings.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION.

Robotic transfer assistance reduced physical demand and work among end users and caregivers.

The robotic device had a positive impact on some quality of life outcomes after 6 weeks of use.

Users were highly likely to recommend the robotic transfer device to others.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by the National Institute of Health Small Business Innovation Grant (SBIR) Phase II [Grant Number R44HD085702–1]. Additional support was provided by National Institutes of Health support through Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CTSI) at the University of Pittsburgh [Grant number UL1-TR-001857].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The contents of this paper do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- [1].Musich S, Wang SS, Ruiz J, et al. The impact of mobility limitations on health outcomes among older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2018;39(2):162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sivaprakasam A, Wang H, Cooper RA, et al. Innovation in transfer assist technologies for persons with severe disabilities and their caregivers. IEEE Potentials. 2017;36(1):34–41. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Garg A, Owen B, Beller D, et al. A biomechanical and ergonomic evaluation of patient transferring tasks: bed to wheelchair and wheelchair to bed. Ergonomics. 1991;34(3): 289–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kjellberg K, Lagerström M, Hagberg M. Patient safety and comfort during transfers in relation to nurses’ work technique. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(3):251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Alamgir H, Li OW, Gorman E, et al. Evaluation of ceiling lifts in health care settings: patient outcome and perceptions. Aaohn J. 2009;57(9):374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiver Statistics: demographics. 2016. June 4, 2019. Available from: https://www.caregiver.org/caregiver-statistics-demographics. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Darragh AR, Sommerich CM, Lavender SA, et al. Musculoskeletal discomfort, physical demand, and caregiving activities in informal caregivers. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;34(6):734–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pompeii LA, Lipscomb HJ, Schoenfisch AL, et al. Musculoskeletal injuries resulting from patient handling tasks among hospital workers. Am J Ind Med. 2009;52(7):571–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Campo M, Weiser S, Koenig KL, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in physical therapists: a prospective cohort study with 1-year follow-up. Phys Ther. 2008;88(5):608–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Waters TR. When is it safe to manually lift a patient? Am J Nurs. 2007;107(8):53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].The National Caregiving Alliance and AARP Public Policy Institute, Caregiving in the US. 2015. Available from: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/caregiving-in-the-united-states-2015-report-revised.pdf

- [12].Reinhard SC, Given B, Petlick NH, et al. Supporting family caregivers in providing care. In Patient safety and quality: an evidence-based handbook for nurses. US: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sun C, Buchholz B, Quinn M, et al. Ergonomic evaluation of slide boards used by home care aides to assist client transfers. Ergonomics. 2018;61(7):913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Owen BGA. ., Assistive devices for use with patient handling tasks. Adv Indust Ergon Safe. 1990; 2:585–592. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pellino TA, Owen B, Knapp L, et al. The evaluation of mechanical devices for lateral transfers on perceived exertion and patient comfort. Orthop Nurs. 2006;25(1):4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dicianno BE, Joseph J, Eckstein S, et al. The voice of the consumer: a survey of veterans and other users of assistive technology. Mil Med. 2018;183(11–12):e518–e525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hart SG, Staveland LE. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): results of empirical and theoretical research, in advances in psychology. North-Holland: Elsevier; 1988. p. 139–183. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wessels R, Persson J, Lorentsen Ø, et al. IPPA: Individually prioritised problem assessment. TAD. 2002;14(3):141–145. [Google Scholar]

- [19].McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Lu JR, et al. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Medical Care. 1994;51(11):40–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Escobar A, Quintana Jm Fau-Bilbao A, Bilbao A Fau-Arostegui I, et al. Responsiveness and clinically important differences for the WOMAC and SF-36 after total knee replacement. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15(3):273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hess JA, Kincl LD, Mandeville DS. Comparison of three single-person manual patient techniques for bed-to-wheelchair transfers. Home Healthcare Now. 2007;25(9):577–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sivakanthan S, Blaauw E, Greenhalgh M, et al. Person transfer assist systems: a literature review. Disab Rehab Assist Technol. 2019;1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Weiner C, Alperovitch-Najenson D, Ribak J, et al. Prevention of nurses’ work-related musculoskeletal disorders resulting from repositioning patients in bed: comprehensive narrative review. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;63(5):226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Traversoni S, Jutai J, Fundarò C, et al. Linking the Psychosocial Impact of Assistive Devices Scale (PIADS) to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(12):3217–3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Day H, Jutai J, Campbell K. Development of a scale to measure the psychosocial impact of assistive devices: lessons learned and the road ahead. Disabil Rehabil. 2002; 24(1–3):31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Davis JC, Bryan S, Best JR, et al. Mobility predicts change in older adults’ health-related quality of life: evidence from a Vancouver falls prevention prospective cohort study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):101–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mortenson WB, Demers L, Fuhrer MJ, et al. How assistive technology use by individuals with disabilities impacts their caregivers: a systematic review of the research evidence. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012; 91(11) :984–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gagnon D, Koontz A, Mulroy S, et al. Biomechanics of sitting pivot transfers among individuals with a spinal cord injury: a review of the current knowledge. Topic Spinal Cord Inj Rehab. 2009;15(2):33–58. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.