Abstract

Proper maintenance of epigenetic information after replication is dependent on the rapid assembly and maturation of chromatin. Chromatin Assembly Complex 1 (CAF-1) is a conserved histone chaperone that deposits (H3-H4)2 tetramers as part of the replication-dependent chromatin assembly process. Loss of CAF-1 leads to a delay in chromatin maturation, albeit with minimal impact on steady-state chromatin structure. However, the mechanisms by which CAF-1 mediates the deposition of (H3-H4)2 tetramers and the phenotypic consequences of CAF-1-associated assembly defects are not well understood. We used nascent chromatin occupancy profiling to track the spatiotemporal kinetics of chromatin maturation in both wild-type (WT) and CAF-1 mutant yeast cells. Our results show that loss of CAF-1 leads to a heterogeneous rate of nucleosome assembly, with some nucleosomes maturing at near WT kinetics and others showing significantly slower maturation kinetics. The slow-to-mature nucleosomes are enriched in intergenic and poorly transcribed regions, suggesting that transcription-dependent assembly mechanisms can reset the slow-to-mature nucleosomes following replication. Nucleosomes with slow maturation kinetics are also associated with poly(dA:dT) sequences, which implies that CAF-1 deposits histones in a manner that counteracts resistance from the inflexible DNA sequence, promoting the formation of histone octamers as well as ordered nucleosome arrays. In addition, we show that the delay in chromatin maturation is accompanied by a transient and S-phase-specific loss of gene silencing and transcriptional regulation, revealing that the DNA replication program can directly shape the chromatin landscape and modulate gene expression through the process of chromatin maturation.

In eukaryotic cells, genomic DNA is packaged into chromatin, a highly organized DNA–protein complex that encodes the epigenetic information essential for regulating DNA-mediated processes, including gene transcription (Jiang and Pugh 2009), DNA replication (Kurat et al. 2017), and DNA repair (Chen and Tyler 2022). Despite the critical regulatory role of chromatin, the epigenetic landscape is disrupted in every cell cycle during S phase. Specifically, as replication forks proceed through the genome, parental chromatin ahead of the fork must be disassembled for DNA synthesis and then re-established in the wake of the fork (Jackson 1990; Gruss et al. 1993). Efficient and faithful propagation of the chromatin structure is critical for maintaining genome integrity and epigenetic memory.

Genetic and biochemical experiments have identified many factors and mechanisms involved in replication-coupled chromatin assembly (MacAlpine and Almouzni 2013). The assembly of nucleosomes is a step-wise process starting with the deposition of (H3-H4)2 tetramers, either recycled from parental chromatin or newly synthesized, followed by the addition of two H2A-H2B dimers (Jackson 1988; Smith and Stillman 1991). Nascent and parental (H3-H4)2 tetramers carry distinct histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) and are deposited onto the leading and lagging strand in a coordinated manner that ensures proper inheritance of the PTM landscape in the daughter cells (Masumoto et al. 2005; Gan et al. 2018; Reverón-Gómez et al. 2018; Li et al. 2020). Under certain conditions, (H3-H4)2 tetramers can form stable intermediates with DNA termed tetrasomes (Hall et al. 2009; Andrews et al. 2010; Böhm et al. 2011; Ordu et al. 2019), but typically the formation of intact nucleosomes occurs rapidly and is tightly coupled to the replication fork (Cusick et al. 1984; Sogo et al. 1986; Gasser et al. 1996).

Chromatin assembly is predominantly mediated by histone chaperones, and one of the key players is CAF-1 (Smith and Stillman 1991; Gurard-Levin et al. 2014; Miller and Costa 2017). CAF-1 is a three-subunit protein complex consisting of Rlf2 (also known as Cac1), Cac2, and Msi1 (also known as Cac3) (CHAF1A, CHAF1B, and RBBP4 in human cells) and is highly conserved from yeast to human cells. Its role in promoting nucleosome assembly on nascent DNA strands was first identified in an SV40-based in vitro study (Smith and Stillman 1989). More recent studies found that CAF-1 receives nascent H3-H4 dimers from Asf1, facilitates the dimerization of H3-H4 to form (H3-H4)2 tetramers, and deposits them onto the newly replicated DNA through an interaction with PCNA (Shibahara and Stillman 1999; Liu et al. 2016, 2017). In addition, CAF-1 shows a high affinity for the PTM H3K56ac, present on nascent H3-H4 in yeast, suggesting that CAF-1 contributes to the deposition of new histones (Masumoto et al. 2005; Li et al. 2008).

CAF-1 is essential in multicellular organisms. Loss of CAF-1 causes development to cease at the early embryonic stage in mice and leads to larval lethality in Drosophila (Houlard et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2013). In human cells, loss of CAF-1 halts S-phase progression and arrests cells in early or mid S phase (Hoek and Stillman 2003). In yeast, disruption of CAF-1 does not affect the viability of the cells, which is partly owing to the functional redundancy between CAF-1 and RTT106 in yeast as a cac1Δ rtt106Δ double mutant is required to severely disrupt de novo nucleosome assembly (Li et al. 2008). The double mutant shows unstable replication forks and an increase in transcription during S phase (Clemente-Ruiz et al. 2011; Topal et al. 2019). However, loss of CAF-1 alone does lead to phenotypic defects, including loss of silencing at the subtelomeric regions and mating type loci, as well as increased sensitivity to UV damage (Kaufman et al. 1997; Monson et al. 1997; Enomoto and Berman 1998; Smith et al. 1999), yet with a seemingly minimal impact on nucleosome organization and positioning (van Bakel et al. 2013; Fennessy and Owen-Hughes 2016). Although the molecular function of CAF-1 is well established, it remains unclear how the loss of CAF-1-associated phenotypes relates to its role in chromatin assembly.

To better understand the role of CAF-1 in chromatin maturation, we monitored the spatiotemporal kinetics of chromatin maturation in wild-type (WT) and CAF-1 mutant cells. We used nucleotide analog labeling and chromatin occupancy profiling to observe the kinetics of chromatin maturation throughout the genome (Fennessy and Owen-Hughes 2016; Ramachandran and Henikoff 2016; Vasseur et al. 2016; Gutiérrez et al. 2019; Stewart-Morgan et al. 2019). Our investigation aims to elucidate the mechanisms by which CAF-1 contributes to chromatin maturation and its potential impact on epigenetic silencing and cryptic transcription during S phase. Through this study, we provide insights into the cellular processes underpinning chromatin maturation and the functional significance of CAF-1 in these processes.

Results

Nascent chromatin occupancy profiling reveals an assembly defect in cac1Δ cells

To capture the dynamics of chromatin assembly behind the replication fork, we used nascent chromatin occupancy profiling (NCOP) (Gutiérrez et al. 2019). NCOP combines EdU labeling of newly synthesized DNA with MNase profiling (Henikoff et al. 2011) to track the spatiotemporal kinetics of chromatin assembly at nucleotide resolution. An asynchronous population of cells were pulse-labeled with the nucleoside analog EdU for 5 min, followed by a thymidine chase for 10, 15, 20, or 40 min to capture chromatin assembly dynamics at all active replication forks across the genome (Fig. 1A). After the pulse-chase labeling, the chromatin samples were digested by MNase. The EdU-labeled DNA fragments were biotinylated with click chemistry and enriched using streptavidin–biotin isolation before being subjected to paired-end sequencing. DNA fragments protected by the histone octamer should be ∼150 bp in length, whereas small DNA binding factors such as transcription factors or the origin recognition complex protect DNA fragments <80 bp. Importantly, this assay provides a factor-agnostic view of chromatin assembly dynamics throughout the genome.

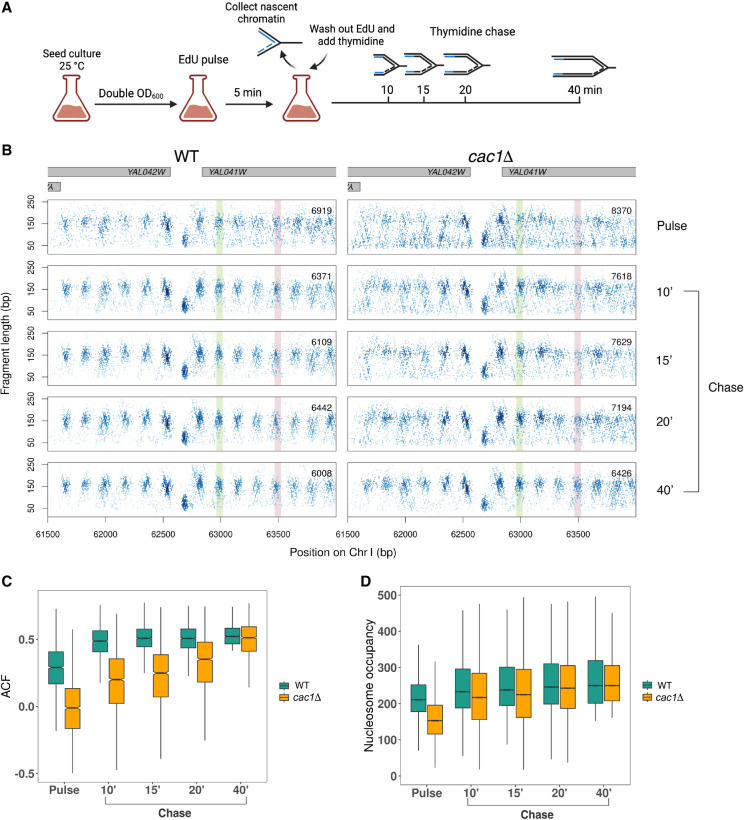

Figure 1.

Nascent chromatin occupancy profiling (NCOP) reveals a chromatin maturation defect in cac1Δ cells. (A) Schematic of experimental design for capturing chromatin maturation dynamics behind the replication fork. Panel created with BioRender (https://www.biorender.com). (B) Chromatin occupancy profiles at a representative locus in WT and cac1Δ cells after a 5-min EdU pulse and 10, 15, 20, and 40 min following a thymidine chase. Each dot represents a fragment midpoint, the shading of which is determined by a 2D kernel density estimate. The number of fragments in each window is inset on each panel. Gene bodies are shown in gray on the top. An example of a slow-to-mature nucleosome is highlighted in red, and an example of a fast-maturing nucleosome is highlighted in green. (C) Autocorrelation function (ACF) values at each time point for the 2097 genes with regularly phased nucleosome arrays in mature chromatin, defined as genes with ACF greater than the median in the WT 40-min chase sample. (D) Nucleosome occupancy at all time points for the 41,663 high-confidence nucleosomes, defined as nucleosomes with occupancy greater than the 25th percentile in both WT and cac1Δ cells following the 40-min chase period.

NCOP of WT cells revealed that EdU-labeled nascent chromatin at the fork, following the short pulse period, was more disorganized relative to the chase series. Specifically, the midpoints of the recovered fragments in the chase series of 10, 15, 20, and 40 min were largely localized to a periodic array of focal clusters at ∼150 bp, representing nucleosome positions. In contrast, the fragments in the pulse sample were more dispersed relative to the nucleosome positions (Fig. 1B). We used the autocorrelation function (ACF) to quantify the transient disorganization of chromatin within gene bodies during the pulse and its recovery through the subsequent chase periods. The ACF reveals the periodicity of a complex signal over time or, in this case, the correlated phasing of nucleosome dyads at an inter-nucleosome distance of 172 bp (Gutiérrez et al. 2019). The chromatin recovered from the pulse period of WT cells has a lower ACF than the subsequent chase periods. (Fig. 1C, green).

To better understand how CAF-1 affects chromatin maturation dynamics, we also generated NCOPs in cells lacking Cac1, the largest subunit of CAF-1. In budding yeast, the deletion of CAC1 (cac1Δ) is sufficient to abrogate the histone chaperone activity of CAF-1 without affecting the viability of the cells (Liu et al. 2016; Yadav and Whitehouse 2016). The recovered chromatin from the 40-min chase period in cac1Δ cells was nearly indistinguishable from WT chromatin (Fig. 1B,C). Despite the similarities in mature chromatin, the cac1Δ cells showed a marked delay in the kinetics of chromatin maturation. The pulse and 10-, 15-, and 20-min samples were all significantly less structured than mature chromatin.

We also examined the kinetics of deposition for individual nucleosomes. We identified about 42,000 high-confidence nucleosomes in WT and cac1Δ cells and calculated their occupancy in the two strains throughout the time course (Fig. 1D). Although the nucleosome occupancy at the final time point is comparable between the two strains, it takes longer for nucleosomes to reach full occupancy in cac1Δ cells (Fig. 1D), consistent with a defect in the deposition of nascent (H3-H4)2 tetramers. Together, these results suggest a transient defect in replication-coupled chromatin assembly and maturation in cac1Δ cells.

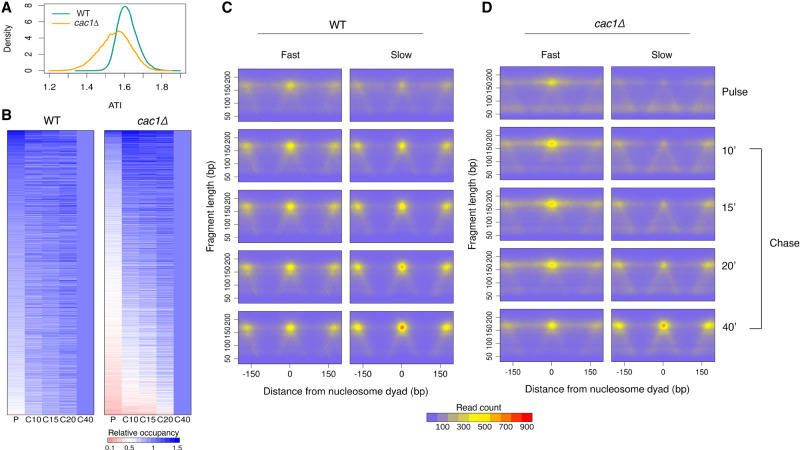

Heterogeneous rate of histone octamer assembly behind the fork

In addition to the pronounced delay in chromatin maturation, we also observed that individual nucleosomes in cac1Δ cells mature at a heterogenous rate. For example, the nucleosome at 63,000 bp (highlighted in green in Fig. 1B) on Chr I matures rapidly behind the fork and reaches maximal occupancy 10 min after the passing of the replication fork. In contrast, the nucleosome at 63,500 bp (highlighted in red in Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S1) does not fully mature until 40 min after passing of the fork. To systematically quantify the maturation rate for individual nucleosomes, we used the reciprocal of the mean weighted sum of occupancy from each time point to generate an assembly timing index (ATI), with lower values reflecting slower maturation kinetics (Raghuraman et al. 2001; Van Rechem et al. 2021). We calculated an ATI value for all high-confidence nucleosomes in cac1Δ and WT cells, respectively, and plotted their distributions (Fig. 2A). The lower ATI from cac1Δ cells is consistent with a global delay in nucleosome deposition. To visualize the maturation dynamics of individual nucleosomes, we generated ordered heatmaps, based on the ATI value, depicting the nucleosome occupancy at each time point relative to the final time point (Fig. 2B). For visualization purposes, we are only depicting the nucleosomes from Chr IV, but they are representative of the nucleosomes throughout the genome (Supplemental Fig. S2). The heatmaps for WT and cac1Δ were ordered independently, as we found no correlation in ATI values between individual nucleosomes (Supplemental Fig. S3). In contrast to the uniform maturation pattern seen in WT cells, cac1Δ cells show diverse maturation dynamics.

Figure 2.

cac1Δ cells show a heterogeneous rate of histone octamer assembly behind the fork. (A) Density distributions of ATI values for all high-confidence nucleosomes in WT and cac1Δ cells. (B) Heat maps of nucleosome occupancy at each time point relative to the final time point for the 5344 high-confidence nucleosomes on Chr IV. Each row represents an individual nucleosome. Heat maps are ordered independently by decreasing ATI values. (C,D) Aggregated chromatin profiles at all time points for the fast and slow nucleosomes identified in WT (C) and cac1Δ (D) cells.

To further explore the differences in maturation dynamics, we sought to agnostically identify the slowest and fastest maturing nucleosomes. We first divided the nucleosomes into deciles based on occupancy in mature chromatin to ensure that fast and slow nucleosomes were comparable based on their final occupancy level. From each decile, we defined nucleosomes with an ATI below the 10th percentile as slow nucleosomes and those with an ATI above the 90th percentile as fast nucleosomes. We identified 4163 fast and slow nucleosomes from both WT and cac1Δ cells. We generated aggregate chromatin occupancy profiles from the slow and fast nucleosomes by aligning to the nucleosome dyads of either the fast or slow nucleosomes (Fig. 2C,D). As expected, in WT cells, the occupancy profiles from slow and fast nucleosomes were highly similar throughout the time course. The lack of distinction between slow and fast nucleosomes in the WT is consistent with the rapid and homogenous maturation pattern we observed. In contrast, in cac1Δ cells, the occupancy profiles of slow and fast nucleosomes were significantly different, depicting two populations of nucleosomes with distinct maturation kinetics (Supplemental Fig. S4). The occupancy of fast nucleosomes plateaus within 10 min, whereas the slow nucleosomes mature more gradually over the time course.

Several groups have reported the existence of “fragile nucleosomes” in yeast that are more sensitive to MNase digestion (Weiner et al. 2010; Henikoff et al. 2011; Xi et al. 2011; Knight et al. 2014; Kubik et al. 2015; Chereji et al. 2017). To confirm that differences in maturation rate observed in cac1Δ cells were not owing to fragile nucleosomes and increased sensitivity to MNase digestion, we calculated the ATI values for previously identified fragile nucleosomes (Chereji et al. 2017; Mitra et al. 2021) in both WT and cac1Δ cells (Supplemental Fig. S5). The density distribution of ATI values for fragile nucleosomes is similar to the full set of high-confidence nucleosomes in both WT and cac1Δ cells. We saw no enrichment of fragile nucleosomes that may represent slow nucleosomes in either WT or cac1Δ cells, suggesting that the nucleosome assembly rate is independent of its steady-state sensitivity to MNase digestion. Additionally, for both fast and slow nucleosomes, we observed unique MNase signatures that indicate nucleosome intermediates converting to full nucleosomes over the time course (Supplemental Fig. S6A). Such signatures are distinct from those of fragile nucleosomes under low and high concentrations of MNase digestion (Supplemental Fig. S6B), suggesting different mechanisms of assembly and disassembly. Overall, we conclude that cac1Δ cells show a heterogeneous rate of nucleosome maturation behind the fork as a result of the chromatin assembly defect.

Genomic and sequence features associated with slow-maturing nucleosomes

To explore the genomic and sequence features influencing the rate of nucleosome deposition in cac1Δ, we examined the distribution of slow nucleosomes throughout the yeast genome. The distribution of slow-maturing nucleosomes along each of the chromosomes appeared random, with a median inter-slow nucleosome distance of 1050 bp; however, we did note a bias, or enrichment, of slow nucleosomes in intergenic regions relative to gene bodies (P < 2.2 × 10−16) (Supplemental Fig. S7). Chromatin is assembled by both replication-dependent and replication-independent mechanisms. We hypothesized that transcription-dependent chromatin assembly mechanisms (Ray-Gallet et al. 2002) may reset the gene body chromatin, especially for transcripts that are highly expressed, including during S phase (Vasseur et al. 2016; Stewart-Morgan et al. 2019).

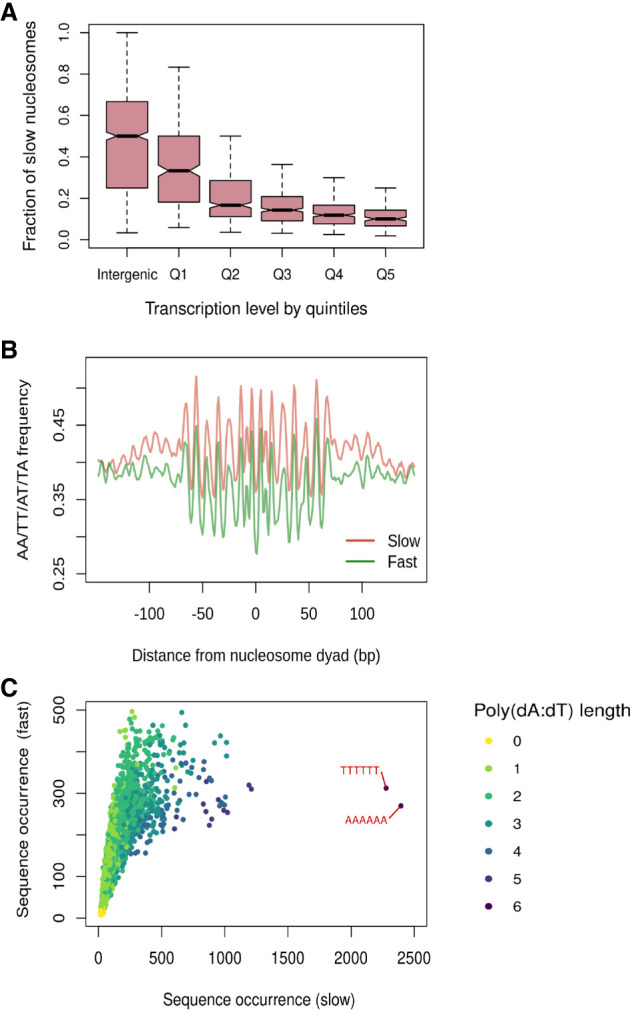

To explore the relationship between the density of slow nucleosomes within a gene and gene expression, we binned the genes by quintiles of gene expression and generated boxplots depicting the density of slow nucleosomes within each gene (Fig. 3A). We found that the least expressed genes (quintile 1) showed a slow nucleosome density that was similar to intergenic sequences, suggesting a default pattern of deposition behind the replication fork. In contrast, with increasing transcription, we observed a gradual decrease in the density of slow nucleosomes within gene bodies. The depletion of slow nucleosomes in the actively transcribed genes is not driven by the occupancy of transcription factors at the promoter regions, as the relationship between slow nucleosome density and transcriptional activity still exists after excluding the first 300 bp of the gene bodies (Supplemental Fig. S8). Together, these results suggest that the heterogeneous patterns of nucleosome deposition we observe in the absence of Cac1 are dependent on replication and that active transcription and transcription-dependent chromatin assembly mechanisms can rapidly restore the chromatin to its native and mature state.

Figure 3.

Genomic and sequence features associated with slow-to-mature nucleosomes. (A) Fraction of slow nucleosomes identified in cac1Δ cells among all nucleosomes in the intergenic regions and gene bodies. Genes are binned into quintiles based on expression levels (Churchman and Weissman 2011). Q1 represents genes with the lowest expression level, and Q5 represents genes with the highest expression level. (B) Aggregated position-dependent A/T dinucleotide frequencies surrounding the dyads of fast and slow nucleosomes. (C) Scatterplot depicting the occurrence of all possible 6-mer sequences from the DNA associated with fast and slow nucleosomes. Dots are colored by the length of the longest poly(dA:dT) sequence that exists in the sequence.

Aside from the rapid transcription-dependent re-establishment of chromatin at the most actively transcribed genes, we did not observe a discernable pattern in the localization of slow-to-mature nucleosomes; thus, we reasoned that other more localized features might govern the maturation speed of individual nucleosomes. It is well established that histone octamers have a strong sequence preference, largely because of the bendability of discrete nucleotide sequences, which is crucial for the formation of nucleosomes (Drew and Travers 1985). Optimal nucleosome formation occurs when the more bendable A/T dinucleotides exist in a ∼10-bp periodicity (Segal et al. 2006; Ioshikhes et al. 2011). In contrast, poly(dA:dT) sequences are inherently stiff, impeding nucleosome formation (Nelson et al. 1987; Segal and Widom 2009). To determine whether local sequence context influences the maturation dynamics of nucleosomes, we determined whether slow and fast nucleosomes are enriched for different sequence motifs. Looking at the nucleotide frequency of the sequences covered by the fast and slow nucleosomes, we discovered that fast and slow nucleosomes both display the classic A/T dinucleotide periodicity; however, slow nucleosomes have elevated levels of A/T frequency, suggesting a potential enrichment in poly(dA:dT) sequences (Fig. 3B). Indeed, we found that slow nucleosomes feature multiple poly(dA:dT) sequence elements that hinder nucleosome formation (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that the histone chaperone function of CAF-1 overcomes the resistance to nucleosome formation from local sequences and ensures a rapid and efficient assembly of nucleosomes at diverse sequences across the genome.

Subnucleosomal fragments captured in cac1Δ cells reveal nucleosome intermediates

In addition to the perturbed nucleosomal chromatin, the nascent chromatin of cac1Δ cells also displayed a genome-wide increase in small fragments that diminished as the chromatin matured (Fig. 4A,B; Supplemental Fig. S9). The small fragments appeared to be present in an array of repeating clusters. Using the ACF, we found that they showed a periodicity of 70 bp (Supplemental Fig. S10). Because of the ubiquity and periodicity of the small fragments, we hypothesize that they reflect nucleosome intermediates (e.g., tetrasomes or hexasomes) and not sites of promiscuous transcription factor binding. The length of the small protected fragments is ∼60–70 bp, which is consistent with the length of DNA predicted to be protected by tetrasomes (Arimura et al. 2012; Ramachandran et al. 2017; Rychkov et al. 2017).

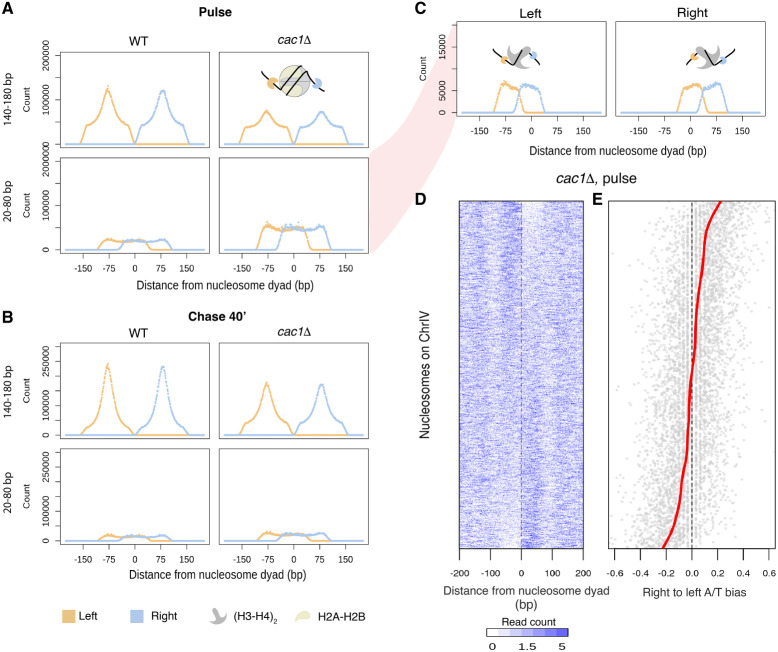

Figure 4.

Subnucleosomal fragments captured in cac1Δ cells reveal nucleosome assembly intermediates. (A,B) Aggregate signals of the left (orange) and right (blue) ends of fragments surrounding the dyads of high-confidence nucleosomes in nascent chromatin (A) and mature chromatin (B) in the two strains. Fragments are divided into nucleosome-sized fragments (140–180 bp in length; top panels) and subnucleosomal-sized fragments (20–80 bp in length; bottom panels). A diagram depicting the fragment ends in relation to the nucleosome is inset in the panel. (C) Fragment ends of the subnucleosomal fragments in the nascent chromatin of cac1Δ cells are plotted separately by the location of the fragment midpoint relative to the nucleosome dyads. (D) Heatmap depicting occupancy of subnucleosomal fragments surrounding individual nucleosomes. Each row corresponds to a high-confidence nucleosome on Chr IV. Rows are ordered by increasing right-to-left occupancy bias (calculated as the log2 ratio) of the subnucleosomal fragments. (E) Dot plot showing the right-to-left A/T bias of DNA sequence associated with individual nucleosomes in the same order as in D. The red line denotes the fitted smooth spline curve.

To explore the hypothesis that these small fragments may represent nucleosome assembly intermediates, we sought to investigate the positioning of the recovered fragments relative to the position of mature nucleosome dyads. To delineate the protected fragments, we visualized the left (orange) and right (blue) ends of each fragment to identify the precise boundaries of the protein–DNA interaction. For example, following the 40-min chase periods, the ends of nucleosome-sized fragments (140–180 bp) in both WT and cac1Δ cells gave rise to two peaks of signal that clearly define the nucleosome edges (Fig. 4B). In contrast, during the short 5-min pulse period, the left and right peaks delineating the nucleosome boundary were less defined, especially in cac1Δ cells (Fig. 4A). Examination of the left and right fragment edges derived from the smaller reads (20–80 bp) showed a bimodal population with one set of fragments starting at the left edge of the nucleosome and ending at the dyad and the next set of fragments starting at the dyad and ending at the right most nucleosome boundary (Fig. 4C). This pattern of the bimodal signal was significantly more prominent in the cac1Δ cells and likely represented a true nucleosome intermediate, as the pattern was transient and restricted to the earlier pulse and chase periods. The length of the small fragments and their position relative to the dyad are also consistent with fragments recovered from the MNase digestion of tetrasomes formed in vitro (Dong and van Holde 1991). Thus, we interpret the broad increase of subnucleosomal fragments as an accumulation of tetrasomes resulting from assembly defects in cac1Δ cells; however, we cannot formally rule out the possibility of hexasomes or partially unwrapped nucleosomes (Ramachandran et al. 2017; Brahma and Henikoff 2019), which would protect DNA of similar length.

The aggregate view of subnucleosome assembly positions, as revealed by the analysis of fragment ends, may suggest an equal distribution on either side of the dyad or an asymmetric bias toward the left or right side. We discovered that the majority of protected and recovered fragments associated with subnucleosome assemblies showed a strong bias to either the right or left side of the mature nucleosome dyad (Fig. 4D). Previous in vitro work showed that differentially oriented hexamers could be generated by modulating the orientation of the Widom 601 in a sequence-specific fashion (Levendosky et al. 2016). To comprehend why these subnucleosome assemblies might show a preference for one side of the nucleosome dyad over the other, we examined the local sequence context, particularly the AT content. We plotted the bias in AT content on each side of the nucleosome dyad, corresponding with the bias in subnucleosome assembly occupancy (Fig. 4E). Our findings indicate that subnucleosome assemblies have a preference for the less AT-rich side, likely evading poly(dA:dT) sequences.

Chromatin assembly defects in the absence of CAF-1 result in a transient and S-phase-specific transcriptional dysregulation

CAF-1 defects can lead to multiple transcriptional program changes, including increased cryptic transcription and loss of silencing at the subtelomeric regions and mating type loci (Monson et al. 1997; Enomoto and Berman 1998; van Bakel et al. 2013). Because CAC1 deletion impacts the kinetics of chromatin assembly during S phase and not the steady state or mature chromatin occupancy and positioning, we hypothesized that the transcriptional changes found in cac1Δ cells are a direct consequence of the delay in chromatin assembly and maturation. To test this hypothesis, we monitored the transcriptional landscape in WT and cac1Δ cells throughout the cell cycle. If transcriptional changes are the result of delayed chromatin maturation, they should occur predominantly in S phase. Cells were synchronized in late G1 with α-factor and then subsequently released into S phase. We collected, following the release into S phase, samples for RNA expression analysis every 10 min for 60 min. Following the 60-min time point, α-factor was added to the culture again to prevent the cells from entering S phase in the subsequent cell cycle. Cell cycle progression for each time point was monitored by flow cytometry. WT and cac1Δ cells progressed through the cell cycle in a similar manner, with cells beginning to enter S phase at 40 min, and by 60 min, most cells had entered into G2/M. At 150 min after release from the initial α-factor and after the readdition of α-factor at 60 min, cells were arrested again in G1 phase (Fig. 5A).

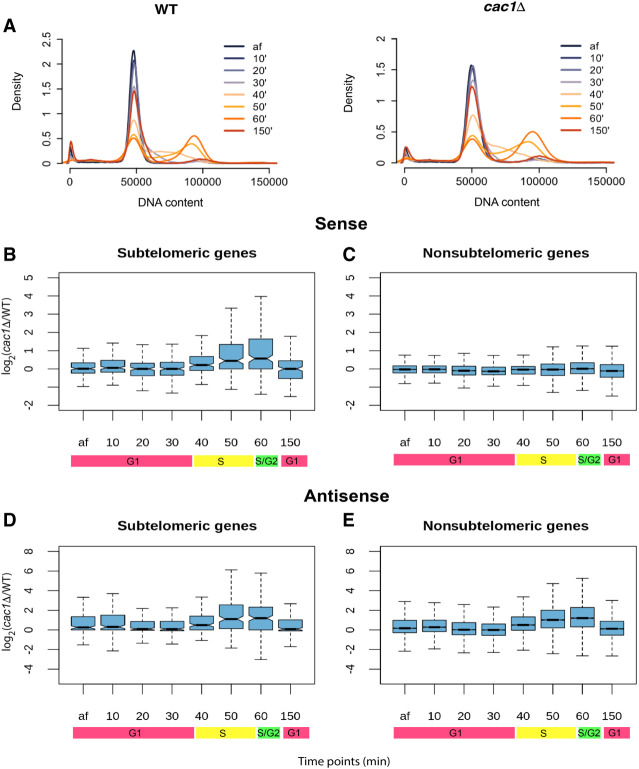

Figure 5.

Chromatin assembly defects in the absence of CAF-1 result in a transient and S-phase-specific dysregulation of transcription. (A) DNA content measured by flow cytometry in WT and cac1Δ cells at the end of α-factor arrest (af) and 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 150 min after release from the initial α-factor arrest. (B–E) Log2 fold-difference of gene expression, measured in TPM, between cac1Δ cells and WT cells. (B,C) Sense transcription. (D,E) Antisense transcription. In both cases, genes are divided into subtelomeric genes (B,D) and nonsubtelomeric genes (C,E).

We first focused on sense transcription. We observed increased gene expression in cac1Δ cells that was specific to subtelomeric genes (located within 20 kb of the chromosome ends) and emerged at 40 min, peaked at 60 min, and became absent again by 150 min, which coincided with the onset and duration of S phase (Fig. 5B,C). The increase in subtelomeric gene expression in the absence of CAF-1 activity suggests a CAF1-dependent transient defect in the establishment of subtelomeric silencing. Next, we examined the pattern of antisense transcription throughout the genome. cac1Δ cells showed an S-phase-specific increase in antisense transcription. However, unlike sense transcription, the increase in antisense transcription was more widespread and not limited to subtelomeric regions, suggesting different mechanisms for regulating sense and antisense transcription when cells are faced with disruption of the nucleosome organization (Fig. 5D,E). In summary, our results show that the elevated antisense transcription and loss of subtelomeric gene silencing occurred in the short window of DNA replication as a result of the delay in chromatin maturation. Although these experiments only capture steady-state transcription levels, we note that the median mRNA half-life in S. cerevisiae is well within the temporal resolution of the experimental time course (Chan et al. 2018; Alalam et al. 2022), and we can clearly observe the regulated expression of canonical cell cycle genes (Supplemental Fig. S11).

Discussion

The disassembly and ordered reassembly of chromatin at the replication fork are critical for preserving epigenetic memory. We used NCOP to assess the kinetics of chromatin assembly behind the replication fork in both WT and cac1Δ cells. The spatiotemporal resolution of assembly dynamics throughout the genome revealed a transient defect in the assembly and deposition kinetics of a large fraction of nucleosomes in the absence of the histone chaperone CAF-1. This transient defect in chromatin maturation behind the fork resulted in the dysregulation of transcription during S phase, including loss of subtelomeric silencing and elevated antisense transcription.

Genetic and biochemical experiments have established the role of CAF-1 in replication-coupled nucleosome assembly (Sauer et al. 2018). However, nucleosome organization and phasing were largely preserved in the absence of CAF-1 subunits (Cac1, Cac2, and Cac3), albeit with a slightly larger linker distance between nucleosomes (van Bakel et al. 2013). More recently, studies in yeast and Drosophila have used an EdU pulse-chase labeling strategy (similar to our NCOP) to map nascent and mature chromatin in the absence of CAF-1 (Ramachandran and Henikoff 2016; Vasseur et al. 2016). These studies found that mature (chase) chromatin and nucleosome organization, in the absence of CAF-1, were largely indistinguishable from WT chromatin, but the nascent (pulse) chromatin was more disorganized, suggesting a global defect in chromatin maturation. These studies assessed nucleosome positioning and occupancy in aggregate across the ensemble of gene bodies. Although we also observed similar dynamics in aggregate (Supplemental Fig. S12), the increased spatial and temporal resolution of our assay allowed us to investigate nucleosome maturation and occupancy on a per-nucleosome basis throughout the genome, which revealed considerable heterogeneity in the assembly kinetics of nucleosomes in the absence of CAF-1. We identified nucleosomes whose maturation rates are near WT (fast nucleosomes), as well as nucleosomes with significantly slower maturation kinetics (slow nucleosomes).

The slow-to-mature nucleosomes occurred throughout the genome with an approximate density of one slow nucleosome per 1 kb. Slow nucleosomes were depleted in gene bodies relative to intergenic sequences. The differential deposition of slow nucleosomes between intergenic regions and gene bodies could be owing, in part, to elevated GC content in gene bodies or active transcription. We found a linear relationship between transcriptional activity and the density of slow nucleosomes in gene bodies. Specifically, we found a paucity of slow nucleosomes in actively transcribed genes, whereas silenced or poorly transcribed genes had a similar density of slow nucleosomes to intergenic regions. These results suggest that the deposition and maturation of slow nucleosomes are a replication-dependent process resulting from the loss of CAF-1 and that transcription-dependent chromatin assembly mechanisms (Ray-Gallet et al. 2002) are able to rapidly reset the chromatin landscape of actively transcribed genes (Vasseur et al. 2016; Stewart-Morgan et al. 2019).

We also explored the sequence features associated with slow nucleosomes and found an enrichment for poly(dA:dT) sequences, which are inherently inflexible and prohibitive to the formation of nucleosomes (Nelson et al. 1987; Segal and Widom 2009). We can envision at least two models to account for the presence of slow nucleosomes and their association with poly(dA:dT) sequences. In the first model, CAF-1 activity facilitates the deposition of nascent histone (H3-H4)2 tetramers on sequences recalcitrant to nucleosome formation. In the second model, the decreased nucleosome density behind the replication fork resulting from a defect in the deposition of nascent (H3-H4)2 tetramers results in the stochastic deposition of histone tetramers on exposed double-stranded DNA without the physical constraints from neighboring nucleosomes. We currently favor the second model as deposition of parental histones on the poly(dA:dT) sequences should not be affected by CAC1 deletion and, therefore, would not result in the strong nucleosome-specific patterns we observe throughout the genome.

We observed an accumulation of regularly phased clusters of small subnucleosomal-sized fragments in the nascent chromatin that was cac1Δ-dependent. The subnucleosomal fragments are ∼60 bp in length, and the phased clusters of fragments show a periodicity of 70 bp. When aligned to nucleosome dyads, they give rise to two clusters of fragments that lie on either side of the nucleosome dyad, denoting DNA–protein interaction bordered by one edge of the nucleosome and the nucleosome dyad. We interpret the cac1Δ-dependent increase in subnucleosomal fragments to suggest that tetrasomes or hexasomes transiently accumulate on nascent chromatin as a result of assembly and maturation defects. Both in vitro and in vivo experiments show that nucleosome assembly starts with the binding of (H3-H4)2 tetramers to DNA, followed by the binding of H2A-H2B dimers (Wilhelm et al. 1978; Andrews et al. 2010). Considering the geometry of nucleosomes in which H2A-H2B dimers surround the central (H3-H4)2 tetramers (Luger et al. 1997), the step-wise assembly of nucleosomes implies that the (H3-H4)2 tetramers are first deposited at the “center” of the nucleosome, followed by binding of H2A-H2B on either side of the nucleosome. The asymmetric positioning of the nucleosome intermediates captured in cac1Δ cells deviates from the proposed step-wise assembly, suggesting that without CAF-1, nucleosome intermediates “slide” to a more thermally stable conformation (indicated by elevated AT-content), which may defer the formation of histone octamers. The positioning of the nucleosome intermediate is corrected eventually, perhaps by the association of H2A-H2B or the turnover of nucleosomes (Dion et al. 2007; Deal et al. 2010). These results are consistent with the function of CAF-1 in counteracting the inherent DNA–histone affinity preference and anchoring the tetramers at desired positions that promote nucleosome formation. Although MNase has a known bias toward AT-rich sequences (Dingwall et al. 1981; Hörz and Altenburger 1981), the design of our experiments, comparing across genotypes and the transient nature of the chromatin assembly defects in cac1Δ cells, make it doubtful that this bias is affecting our conclusions. Together, the findings provide important mechanistic insights into understanding how CAF-1 mediates (H3-H4)2 tetramer deposition onto nascent DNA.

Following the passage of the DNA replication fork, the parental epigenetic landscape must be restored on both daughter strands. Elegant genetic and biochemical experiments have begun to elucidate the factors and mechanisms responsible for the balanced inheritance of parental histones to the leading and lagging strands. Parental histones do not segregate randomly, but rather a diverse collection of factors such as Mcm2, Dpb3-Dpb4, pol α, etc., work together to ensure the balanced segregation of parental histones to both the leading and lagging strands (Gan et al. 2018; Petryk et al. 2018; Yu et al. 2018; Li et al. 2020). Our current NCOP assay does not provide information on nucleosome deposition on the leading and the lagging strands; however, the transient gaps in nucleosome occupancy behind the replication fork in the absence of Cac1 may affect how parental histone marks are copied and restored on the daughter chromatids.

Underscoring the importance of nucleosome deposition and maturation, loss of CAF-1 activity results in loss of gene silencing (Monson et al. 1997; Enomoto and Berman 1998; Smith et al. 1999), as well as increased cryptic transcription (van Bakel et al. 2013). Consistent with the transient delay we observed in nucleosome deposition and maturation in the absence of CAF-1, we found that the loss of silencing and cryptic transcription phenotypes were transient and confined to S phase. These findings are consistent with previous work showing that the disruption of H3K56ac-dependent nucleosome assembly by loss of both CAF-1 and RTT106 increases global transcription during S phase (Topal et al. 2019). Similarly, the deregulation of the DNA replication timing program leads to S-phase-specific transcriptional changes that mimic those caused by defects in chromatin assembly factors, presumably because the chromatin assembly machinery cannot keep pace with the rapid replication rate, resulting in transient defects in histone assembly (Santos et al. 2022). The S-phase-specific increase in gene expression from the subtelomeric regions of the chromosomes suggests that the re-establishment of silencing following passage of the fork was initially impaired but later recovered following chromatin maturation. We propose that the gaps in nucleosome distribution prevent the spreading of the silencing near the telomeres, likely by disrupting the nucleosome–Sir3 interaction (Saxton and Rine 2020; Brothers and Rine 2022).

An increase in cryptic transcription initiating from the gene bodies has been observed with the loss of Spt6 or Spt16, which is associated with decreased nucleosome occupancy and organization within gene bodies (Cheung et al. 2008; Doris et al. 2018). There is also evidence for antisense transcription initiating from the nucleosome-free region (NFR) of transcribed genes, indicating that some promoters may be bidirectional (Xu et al. 2009). In the case of CAC1 deletion, we found that the increase in antisense transcription is confined to the promoter regions of the genes and does not spread into the genes upstream (Supplemental Fig. S13), suggesting that cryptic transcription initiates from within the gene bodies in the absence of Cac1.

Together, these results underscore the importance of DNA replication and chromatin maturation in shaping the chromatin landscape and open up new avenues for understanding how aberrations in these processes might contribute to dynamic gene expression programs during development and in disease states such as cancer.

Methods

Yeast strains

All yeast strains are in the W303 background. WT cells have the following genotype: MATa, leu2-3112, BAR1::TRP, can1-100, URA3::BrdU-Inc, ade2-1, his3-11,15. cac1Δ cells have the following genotype: MATa, leu2-3112, BAR1::TRP, can1-100, URA3::BrdU-Inc, ade2-1, his3-11,15, rlf2Δ::HIS (note: RLF2 is the standard name for CAC1).

Cell growth and culturing

To profile nascent and mature chromatin, yeast cells were grown at 25°C to an OD600 of ∼0.7. EdU (Berry and Associates) was added to the culture at a final concentration of 130 µM. At the same time, α-factor (GenWay) was added to the culture at a final concentration of 50 ng/mL. After 5 min of EdU pulse, a sample was taken for nascent chromatin, after which cells were washed and resuspended in fresh media containing 130 µM thymidine (Sigma-Aldrich) and 50 ng/mL α-factor. Samples were taken at 10, 15, 20, and 40 min after the media change. Cells were washed twice with sterile water before being pelleted and flash-frozen. Cell pellets were stored at −80°C. All experiments were performed with independent biological replicates.

To collect samples for RNA-seq, yeast cells were grown at 25°C to an OD600 of ∼0.7 and arrested in G1 phase with α-factor at a final concentration of 50 ng/mL for 2 h. At the end of the α-factor arrest, a sample was collected (af sample), and then, the cells were washed twice in sterile water and released into fresh media. Samples were collected at 10-min intervals for 60 min, after which α-factor was added back to the media at the same concentration. A final sample was collected at 150 min after release from the initial α-factor. The cells were processed and stored as mentioned above. At each time point, a separate sample was collected for flow cytometry. An independent biological replicate was performed with the time points af, 40 min, and 60 min. Figure 5, B–E, was generated with replicate 1. A comparison between the two replicates is shown in Supplemental Figure S14.

Chromatin preparation

MNase digestions were performed as previously described (Belsky et al. 2015).

Click reaction and streptavidin affinity capture

Sixty micrograms of MNase-digested DNA was mixed with click chemistry reaction buffers as previously described (Stewart-Morgan et al. 2019) in siliconized tubes (Bio Plas). The mixture was incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. DNA was purified using Probe Quant G50 columns (GE Healthcare) followed by ethanol precipitation. To capture biotin-conjugated DNA, 10 µL of streptavidin magnetic beads (New England Biolabs) per sample was blocked as previously described (Gutiérrez et al. 2019). After blocking, beads were washed with cold binding buffer (1 M Tris, 5 M NaCl, 10% NP-40, 0.5 M EDTA) and resuspended in the same volume of the binding buffer as the original volume of beads. Streptavidin beads were mixed with DNA and incubated with 200 µL of binding buffer overnight at 4°C with gentle rotation. Following incubation, bead-bound DNA was washed twice with cold binding buffer and three times with EB buffer (Qiagen).

Sequencing library preparation

Library preparations were performed on bead-bound DNA as previously described (Gutiérrez et al. 2019).

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed in R (R Core Team 2023) For detailed descriptions of data analysis, see the Supplemental Methods. Data processing scripts are available as Supplemental Code.

Data access

All sequencing data from this study have been submitted to the NCBI BioProject database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/) under accession number PRJNA974469.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank former and current members of the MacAlpine group and the Hartemink group for comments and suggestions during the development of the project. We thank Dr. Lee Zou for a critical reading of the manuscript. D.M.M. is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R35-GM127062, and A.J.H. is supported by NIH grant R35-GM141795.

Author contributions: D.M.M. and B.C. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. B.C. performed experiments and data analysis. H.K.M. performed experiments. A.J.H. advised on data analysis and edited the manuscript.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at https://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.278273.123.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Alalam H, Zepeda-Martínez JA, Sunnerhagen P. 2022. Global SLAM-seq for accurate mRNA decay determination and identification of NMD targets. RNA 28: 905–915. 10.1261/rna.079077.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews AJ, Chen X, Zevin A, Stargell LA, Luger K. 2010. The histone chaperone Nap1 promotes nucleosome assembly by eliminating nonnucleosomal histone DNA interactions. Mol Cell 37: 834–842. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura Y, Tachiwana H, Oda T, Sato M, Kurumizaka H. 2012. Structural analysis of the hexasome, lacking one histone H2A/H2B dimer from the conventional nucleosome. Biochemistry 51: 3302–3309. 10.1021/bi300129b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky JA, MacAlpine HK, Lubelsky Y, Hartemink AJ, MacAlpine DM. 2015. Genome-wide chromatin footprinting reveals changes in replication origin architecture induced by pre-RC assembly. Genes Dev 29: 212–224. 10.1101/gad.247924.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm V, Hieb AR, Andrews AJ, Gansen A, Rocker A, Tóth K, Luger K, Langowski J. 2011. Nucleosome accessibility governed by the dimer/tetramer interface. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 3093–3102. 10.1093/nar/gkq1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahma S, Henikoff S. 2019. RSC-associated subnucleosomes define MNase-sensitive promoters in yeast. Mol Cell 73: 238–249.e3. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothers M, Rine J. 2022. Distinguishing between recruitment and spread of silent chromatin structures in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. eLife 11: e75653. 10.7554/eLife.75653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan LY, Mugler CF, Heinrich S, Vallotton P, Weis K. 2018. Non-invasive measurement of mRNA decay reveals translation initiation as the major determinant of mRNA stability. eLife 7: e32536. 10.7554/eLife.32536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Tyler JK. 2022. The chromatin landscape channels DNA double-strand breaks to distinct repair pathways. Front Cell Dev Biol 10: 909696. 10.3389/fcell.2022.909696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chereji RV, Ocampo J, Clark DJ. 2017. MNase-sensitive complexes in yeast: nucleosomes and non-histone barriers. Mol Cell 65: 565–577.e3. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung V, Chua G, Batada NN, Landry CR, Michnick SW, Hughes TR, Winston F. 2008. Chromatin- and transcription-related factors repress transcription from within coding regions throughout the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. PLoS Biol 6: e277. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchman LS, Weissman JS. 2011. Nascent transcript sequencing visualizes transcription at nucleotide resolution. Nature 469: 368–373. 10.1038/nature09652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Ruiz M, González-Prieto R, Prado F. 2011. Histone H3K56 acetylation, CAF1, and Rtt106 coordinate nucleosome assembly and stability of advancing replication forks. PLoS Genet 7: e1002376. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick ME, DePamphilis ML, Wassarman PM. 1984. Dispersive segregation of nucleosomes during replication of simian virus 40 chromosomes. J Mol Biol 178: 249–271. 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90143-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal RB, Henikoff JG, Henikoff S. 2010. Genome-wide kinetics of nucleosome turnover determined by metabolic labeling of histones. Science 328: 1161–1164. 10.1126/science.1186777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwall C, Lomonossoff GP, Laskey RA. 1981. High sequence specificity of micrococcal nuclease. Nucleic Acids Res 9: 2659–2673. 10.1093/nar/9.12.2659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion MF, Kaplan T, Kim M, Buratowski S, Friedman N, Rando OJ. 2007. Dynamics of replication-independent histone turnover in budding yeast. Science 315: 1405–1408. 10.1126/science.1134053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F, van Holde KE. 1991. Nucleosome positioning is determined by the (H3-H4)2 tetramer. Proc Natl Acad Sci 88: 10596–10600. 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doris SM, Chuang J, Viktorovskaya O, Murawska M, Spatt D, Churchman LS, Winston F. 2018. Spt6 is required for the fidelity of promoter selection. Mol Cell 72: 687–699.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew HR, Travers AA. 1985. DNA bending and its relation to nucleosome positioning. J Mol Biol 186: 773–790. 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90396-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto S, Berman J. 1998. Chromatin assembly factor I contributes to the maintenance, but not the re-establishment, of silencing at the yeast silent mating loci. Genes Dev 12: 219–232. 10.1101/gad.12.2.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fennessy RT, Owen-Hughes T. 2016. Establishment of a promoter-based chromatin architecture on recently replicated DNA can accommodate variable inter-nucleosome spacing. Nucleic Acids Res 44: 7189–7203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan H, Serra-Cardona A, Hua X, Zhou H, Labib K, Yu C, Zhang Z. 2018. The Mcm2-Ctf4-Polα axis facilitates parental histone H3-H4 transfer to lagging strands. Mol Cell 72: 140–151.e3. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser R, Koller T, Sogo JM. 1996. The stability of nucleosomes at the replication fork. J Mol Biol 258: 224–239. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruss C, Wu J, Koller T, Sogo JM. 1993. Disruption of the nucleosomes at the replication fork. EMBO J 12: 4533–4545. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06142.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurard-Levin ZA, Quivy J-P, Almouzni G. 2014. Histone chaperones: assisting histone traffic and nucleosome dynamics. Annu Rev Biochem 83: 487–517. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez MP, MacAlpine HK, MacAlpine DM. 2019. Nascent chromatin occupancy profiling reveals locus- and factor-specific chromatin maturation dynamics behind the DNA replication fork. Genome Res 29: 1123–1133. 10.1101/gr.243386.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MA, Shundrovsky A, Bai L, Fulbright RM, Lis JT, Wang MD. 2009. High-resolution dynamic mapping of histone-DNA interactions in a nucleosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16: 124–129. 10.1038/nsmb.1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff JG, Belsky JA, Krassovsky K, MacAlpine DM, Henikoff S. 2011. Epigenome characterization at single base-pair resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 18318–18323. 10.1073/pnas.1110731108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek M, Stillman B. 2003. Chromatin assembly factor 1 is essential and couples chromatin assembly to DNA replication in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 12183–12188. 10.1073/pnas.1635158100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hörz W, Altenburger W. 1981. Sequence specific cleavage of DNA by micrococcal nuclease. Nucleic Acids Res 9: 2643–2658. 10.1093/nar/9.12.2643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlard M, Berlivet S, Probst AV, Quivy J-P, Héry P, Almouzni G, Gérard M. 2006. CAF-1 is essential for heterochromatin organization in pluripotent embryonic cells. PLoS Genet 2: e181. 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioshikhes I, Hosid S, Pugh BF. 2011. Variety of genomic DNA patterns for nucleosome positioning. Genome Res 21: 1863–1871. 10.1101/gr.116228.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson V. 1988. Deposition of newly synthesized histones: hybrid nucleosomes are not tandemly arranged on daughter DNA strands. Biochemistry 27: 2109–2120. 10.1021/bi00406a044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson V. 1990. In vivo studies on the dynamics of histone-DNA interaction: evidence for nucleosome dissolution during replication and transcription and a low level of dissolution independent of both. Biochemistry 29: 719–731. 10.1021/bi00455a019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Pugh BF. 2009. Nucleosome positioning and gene regulation: advances through genomics. Nat Rev Genet 10: 161–172. 10.1038/nrg2522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman PD, Kobayashi R, Stillman B. 1997. Ultraviolet radiation sensitivity and reduction of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells lacking chromatin assembly factor-I. Genes Dev 11: 345–357. 10.1101/gad.11.3.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B, Kubik S, Ghosh B, Bruzzone MJ, Geertz M, Martin V, Dénervaud N, Jacquet P, Ozkan B, Rougemont J, et al. 2014. Two distinct promoter architectures centered on dynamic nucleosomes control ribosomal protein gene transcription. Genes Dev 28: 1695–1709. 10.1101/gad.244434.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubik S, Bruzzone MJ, Jacquet P, Falcone J-L, Rougemont J, Shore D. 2015. Nucleosome stability distinguishes two different promoter types at all protein-coding genes in yeast. Mol Cell 60: 422–434. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurat CF, Yeeles JTP, Patel H, Early A, Diffley JFX. 2017. Chromatin controls DNA replication origin selection, lagging-strand synthesis, and replication fork rates. Mol Cell 65: 117–130. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky RF, Sabantsev A, Deindl S, Bowman GD. 2016. The Chd1 chromatin remodeler shifts hexasomes unidirectionally. eLife 5: e21356. 10.7554/eLife.21356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhou H, Wurtele H, Davies B, Horazdovsky B, Verreault A, Zhang Z. 2008. Acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 regulates replication-coupled nucleosome assembly. Cell 134: 244–255. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Hua X, Serra-Cardona A, Xu X, Gan S, Zhou H, Yang W-S, Chen C-L, Xu R-M, Zhang Z. 2020. DNA polymerase α interacts with H3-H4 and facilitates the transfer of parental histones to lagging strands. Sci Adv 6: eabb5820. 10.1126/sciadv.abb5820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WH, Roemer SC, Zhou Y, Shen Z-J, Dennehey BK, Balsbaugh JL, Liddle JC, Nemkov T, Ahn NG, Hansen KC, et al. 2016. The Cac1 subunit of histone chaperone CAF-1 organizes CAF-1-H3/H4 architecture and tetramerizes histones. eLife 5: e18023. 10.7554/eLife.18023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WH, Roemer SC, Port AM, Churchill MEA. 2017. CAF-1-induced oligomerization of histones H3/H4 and mutually exclusive interactions with Asf1 guide H3/H4 transitions among histone chaperones and DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 45: 9809. 10.1093/nar/gkx729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Mäder AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. 1997. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature 389: 251–260. 10.1038/38444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAlpine DM, Almouzni G. 2013. Chromatin and DNA replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5: a010207. 10.1101/cshperspect.a010207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masumoto H, Hawke D, Kobayashi R, Verreault A. 2005. A role for cell-cycle-regulated histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation in the DNA damage response. Nature 436: 294–298. 10.1038/nature03714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TC, Costa A. 2017. The architecture and function of the chromatin replication machinery. Curr Opin Struct Biol 47: 9–16. 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S, Zhong J, Tran TQ, MacAlpine DM, Hartemink AJ. 2021. RoboCOP: jointly computing chromatin occupancy profiles for numerous factors from chromatin accessibility data. Nucleic Acids Res 49: 7925–7938. 10.1093/nar/gkab553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson EK, de Bruin D, Zakian VA. 1997. The yeast Cac1 protein is required for the stable inheritance of transcriptionally repressed chromatin at telomeres. Proc Natl Acad Sci 94: 13081–13086. 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HC, Finch JT, Luisi BF, Klug A. 1987. The structure of an oligo(dA)·oligo(dT) tract and its biological implications. Nature 330: 221–226. 10.1038/330221a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordu O, Lusser A, Dekker NH. 2019. DNA sequence is a major determinant of tetrasome dynamics. Biophys J 117: 2217–2227. 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.07.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petryk N, Dalby M, Wenger A, Stromme CB, Strandsby A, Andersson R, Groth A. 2018. MCM2 promotes symmetric inheritance of modified histones during DNA replication. Science 361: 1389–1392. 10.1126/science.aau0294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuraman MK, Winzeler EA, Collingwood D, Hunt S, Wodicka L, Conway A, Lockhart DJ, Davis RW, Brewer BJ, Fangman WL. 2001. Replication dynamics of the yeast genome. Science 294: 115–121. 10.1126/science.294.5540.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S, Henikoff S. 2016. Transcriptional regulators compete with nucleosomes post-replication. Cell 165: 580–592. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S, Ahmad K, Henikoff S. 2017. Transcription and remodeling produce asymmetrically unwrapped nucleosomal intermediates. Mol Cell 68: 1038–1053.e4. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray-Gallet D, Quivy J-P, Scamps C, Martini EM-D, Lipinski M, Almouzni G. 2002. HIRA is critical for a nucleosome assembly pathway independent of DNA synthesis. Mol Cell 9: 1091–1100. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00526-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2023. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Reverón-Gómez N, González-Aguilera C, Stewart-Morgan KR, Petryk N, Flury V, Graziano S, Johansen JV, Jakobsen JS, Alabert C, Groth A. 2018. Accurate recycling of parental histones reproduces the histone modification landscape during DNA replication. Mol Cell 72: 239–249.e5. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychkov GN, Ilatovskiy AV, Nazarov IB, Shvetsov AV, Lebedev DV, Konev AY, Isaev-Ivanov VV, Onufriev AV. 2017. Partially assembled nucleosome structures at atomic detail. Biophys J 112: 460–472. 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.10.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos MM, Johnson MC, Fiedler L, Zegerman P. 2022. Global early replication disrupts gene expression and chromatin conformation in a single cell cycle. Genome Biol 23: 217. 10.1186/s13059-022-02788-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer PV, Gu Y, Liu WH, Mattiroli F, Panne D, Luger K, Churchill ME. 2018. Mechanistic insights into histone deposition and nucleosome assembly by the chromatin assembly factor-1. Nucleic Acids Res 46: 9907–9917. 10.1093/nar/gky823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton DS, Rine J. 2020. Nucleosome positioning regulates the establishment, stability, and inheritance of heterochromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci 117: 27493–27501. 10.1073/pnas.2004111117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E, Widom J. 2009. Poly(dA:dT) tracts: major determinants of nucleosome organization. Curr Opin Struct Biol 19: 65–71. 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Chen L, Thåström A, Field Y, Moore IK, Wang J-PZ, Widom J. 2006. A genomic code for nucleosome positioning. Nature 442: 772–778. 10.1038/nature04979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibahara K, Stillman B. 1999. Replication-dependent marking of DNA by PCNA facilitates CAF-1-coupled inheritance of chromatin. Cell 96: 575–585. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80661-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Stillman B. 1989. Purification and characterization of CAF-I, a human cell factor required for chromatin assembly during DNA replication in vitro. Cell 58: 15–25. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90398-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Stillman B. 1991. Stepwise assembly of chromatin during DNA replication in vitro. EMBO J 10: 971–980. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08031.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JS, Caputo E, Boeke JD. 1999. A genetic screen for ribosomal DNA silencing defects identifies multiple DNA replication and chromatin-modulating factors. Mol Cell Biol 19: 3184–3197. 10.1128/MCB.19.4.3184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogo JM, Stahl H, Koller T, Knippers R. 1986. Structure of replicating simian virus 40 minichromosomes. the replication fork, core histone segregation and terminal structures. J Mol Biol 189: 189–204. 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90390-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart-Morgan KR, Reverón-Gómez N, Groth A. 2019. Transcription restart establishes chromatin accessibility after DNA replication. Mol Cell 75: 284–297.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topal S, Vasseur P, Radman-Livaja M, Peterson CL. 2019. Distinct transcriptional roles for histone H3-K56 acetylation during the cell cycle in yeast. Nat Commun 10: 4372. 10.1038/s41467-019-12400-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bakel H, Tsui K, Gebbia M, Mnaimneh S, Hughes TR, Nislow C. 2013. A compendium of nucleosome and transcript profiles reveals determinants of chromatin architecture and transcription. PLoS Genet 9: e1003479. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rechem C, Ji F, Chakraborty D, Black JC, Sadreyev RI, Whetstine JR. 2021. Collective regulation of chromatin modifications predicts replication timing during cell cycle. Cell Rep 37: 109799. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasseur P, Tonazzini S, Ziane R, Camasses A, Rando OJ, Radman-Livaja M. 2016. Dynamics of nucleosome positioning maturation following genomic replication. Cell Rep 16: 2651–2665. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner A, Hughes A, Yassour M, Rando OJ, Friedman N. 2010. High-resolution nucleosome mapping reveals transcription-dependent promoter packaging. Genome Res 20: 90–100. 10.1101/gr.098509.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm FX, Wilhelm ML, Erard M, Duane MP. 1978. Reconstitution of chromatin: assembly of the nucleosome. Nucleic Acids Res 5: 505–521. 10.1093/nar/5.2.505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Y, Yao J, Chen R, Li W, He X. 2011. Nucleosome fragility reveals novel functional states of chromatin and poises genes for activation. Genome Res 21: 718–724. 10.1101/gr.117101.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Wei W, Gagneur J, Perocchi F, Clauder-Münster S, Camblong J, Guffanti E, Stutz F, Huber W, Steinmetz LM. 2009. Bidirectional promoters generate pervasive transcription in yeast. Nature 457: 1033–1037. 10.1038/nature07728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav T, Whitehouse I. 2016. Replication-coupled nucleosome assembly and positioning by ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling enzymes. Cell Rep 15: 715–723. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Wu H, Chen H, Wang R, Liang X, Liu J, Li C, Deng W-M, Jiao R. 2013. CAF-1 promotes notch signaling through epigenetic control of target gene expression during Drosophila development. Development 140: 3635–3644. 10.1242/dev.094599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, Gan H, Serra-Cardona A, Zhang L, Gan S, Sharma S, Johansson E, Chabes A, Xu R-M, Zhang Z. 2018. A mechanism for preventing asymmetric histone segregation onto replicating DNA strands. Science 361: 1386–1389. 10.1126/science.aat8849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.