Abstract

Table rounds and bedside rounds are two methods healthcare professionals employ during clinical rounds for patient care and medical education. Bedside rounds involve direct patient engagement and physical examination, thus significantly impacting patient outcomes, such as improving communication and patient satisfaction. Table rounds occur in a conference room without the patient present and involve discussing patient data, which is more effective in fostering structured medical education. Both bedside and table rounds have pros and cons, and healthcare professionals should consider the specific requirements of their patients and medical trainees when deciding which approach to use. This research utilized a comprehensive search to identify relevant resources, such as university website links, as well as a PubMed search using relevant keywords such as ‘bedside rounding,’ ‘table rounding,’ and ‘patient satisfaction.’ Relevance, publication date, and study design were the basis for inclusion criteria. This study compared the effectiveness of these two methods based on physician communication, medical education, patient care, and patient satisfaction.

Keywords: Bedside rounding, patient satisfaction, table rounding

Clinical rounds are an essential activity in the medical field that fulfills four functions: communication, medical education, patient care, and assessment.1 Communicating with patients and their families during rounds, including information about treatment plans, education, and collaborative decision-making, is part of the process.2 Teaching and learning during rounds constitute medical education.2 Providing patient care includes conducting physical examinations, a review of systems, and decisions about changing a treatment plan.2 The attending physician evaluates the residents’ aptitude for various medical operations or duties and offers commentary on their performance as part of the assessment process. This kind of evaluation is typical in medical education and aids in ensuring that residents are gaining the abilities and expertise required to become knowledgeable physicians.2 Clinical rounds involve gathering the team members, including the ancillary staff, and discussing the patient. One of the team members, usually the resident or a medical student, presents the patient as a case in a precise SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) note manner. The case presentation is followed by a discussion between team members and the formulation of a plan regarding patient management and disposition.3 Medical students can learn crucial abilities needed to practice medicine during clinical rounds.3

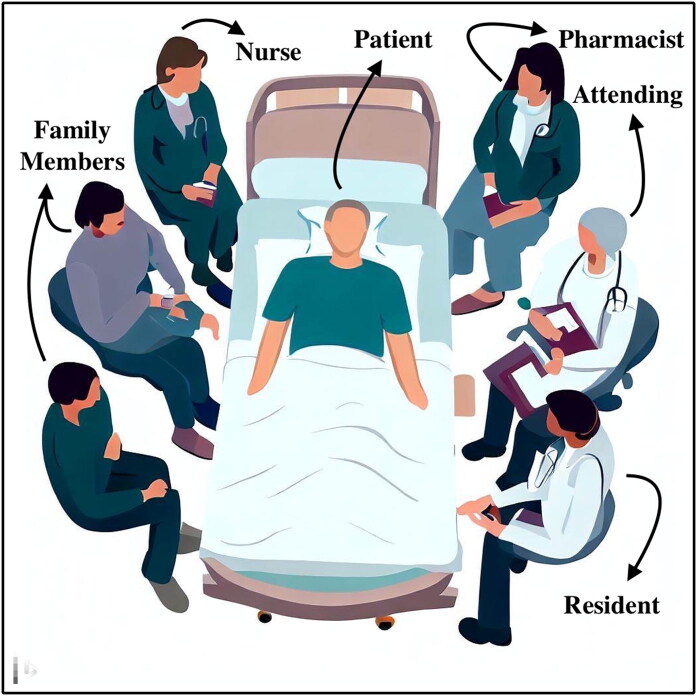

Bedside and table rounding are commonly used methods for conducting hospital clinical rounds. During bedside rounding, physicians, nurses, medical students, pharmacists, social workers, and case managers converse with patients in their rooms or discuss them outside the room (Figure 1). In contrast, table rounding is a clinical method where healthcare providers discuss patient care and progress in a conference room or designated area instead of at the patient’s bedside (Figure 2). Both approaches have advantages and disadvantages; healthcare professionals frequently debate which is most effective.4

Figure 1.

Bedside rounds: A group of healthcare professionals, which includes the attending, resident, nurses, pharmacists, and medical students, are gathered around a patient’s bedside, engaged in a collaborative discussion with the patient and his or her family members.

Figure 2.

Table rounds: A collaborative discussion of patient cases among attending physicians, residents, pharmacists, and medical students gathered around a table in a conference room.

During bedside rounds, healthcare providers discuss the patient’s condition, progress, and care plan with the patient and his or her family members or caregivers.5 This discussion helps patients and healthcare teams communicate effectively, focusing on patient-centered care, which enhances patient involvement.6,7 Patients view medical staff as more empathetic if they perform bedside rounds when compared to table rounds.8 In a study conducted at a university teaching hospital, 94% of the adult participants (n = 100) admitted to a family medicine inpatient team reported that the medical staff spent enough time with them; 98% of the sample (n = 105) reported knowing the condition for which they were receiving medical care; and 94% (n = 105) reported that the medical staff provided clear explanations of the diagnosis and treatment.8 On a scale from 1 to 5, participants stated that they were included in decision-making by the medical staff (4.62, standard deviation [SD] 0.72), that they believed the medical staff (4.91, SD 0.32), that they were pleased with the treatment they received (4.85, SD 0.38), and that their medical staff showed empathy (4.84, SD 0.44) (Table 1).8 Additionally, bedside rounds gives medical professionals a chance to evaluate the patient’s health and respond to any queries or concerns the patient or family may have, all of which can enhance clinical outcomes.9

Table 1.

Patient preference for bedside rounds*

| Question/statement | Percentage/scale (1–5) | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Medical staff spent enough time with participants | 94% | – |

| Medical staff provided clear explanations of diagnosis/treatment | 94% | – |

| Participants were included in decision-making by medical staff | 4.62 | 0.72 |

| Participants believed the medical staff | 4.91 | 0.32 |

| Participants were pleased with the treatment they received | 4.85 | 0.38 |

| Participants felt their medical staff showed empathy | 4.84 | 0.44 |

*Based on a study by Ramirez et al.8

Bedside rounds involving nurses and residents have been demonstrated to enhance interprofessional communication and workplace productivity.10 A prospective study comparing bedside and table rounds in an academic emergency department randomly assigned a convenience sample of 408 hours of clinical shifts to either bedside or table rounds.11 Data collected included how frequently discussion about the differential diagnosis occurred, inquiries made for each patient, the length of time that alternative therapies were discussed, the total amount of discussion about alternate tests, the length of time spent discussing and demonstrating exam results, and the assessment of educational quality by residents.11 A sample size of 274 patient cases was achieved by randomly assigning 20 shifts within each group.11 The main result was increased discussion of the differential diagnosis, which happened more frequently in the bedside group (72% vs 53%), which also improved the quality of medical education and healthcare delivery.11 Some residents did report feeling less comfortable asking questions during bedside rounds, but early identification and intervention are necessary to maximize its benefits.12–14

During table rounds, healthcare providers review patient charts, discuss treatment plans and progress, and make care decisions.15 Many healthcare team members are involved, which facilitates the scheduling of rounds and offers a more organized method for making clinical decisions.16 However, table rounding can sometimes be less patient-centered than bedside rounding since patients are not directly involved in the discussion, limiting the healthcare team’s ability to make clinical observations and provide more personalized care.17

In a study conducted by Merchant et al, among 301 attending physicians and 195 residents, bedside rounds were conducted 19% of the time.6 Two-thirds of residents preferred table rounds.6 The main reason why 72% of residents and 47% of attending physicians didn’t prefer bedside rounds was due to the long duration of rounds.6 Improvement in oral presentation, physical examination skills, and patient education by utilizing a common language that the patient understands was noted as the benefit of bedside rounds by 84% of attending physicians and 69% of residents.6 However, compared to other forms of rounding, only 34% of residents felt that bedside rounds allowed them to learn more about patient care (Table 2).6

Table 2.

Attending and resident views on rounds*

| Criteria | Attending physicians | Residents |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of bedside rounding | 19% | – |

| Preferred rounding location for residents | – | 67% |

| Concern over round lengthening | 47% | 72% |

| Potential benefits of bedside rounds | ||

| Improving oral presentation skills | 84% | 69% |

| Enhancing physical examination skills | 84% | 69% |

| Utilizing patient-friendly language | 84% | 69% |

| Attending physicians’ skills for bedside rounds | 95% | – |

| Attending physicians’ views on teaching abilities improvement | 69% | – |

| Residents’ belief in the importance of bedside rounds | – | 62% |

| Residents’ perception of learning more about patient care with bedside rounds | – | 34% |

*Based on a study by Merchant et al.6

In a study, 394 families were encountered while rounding (261 English- and 133 Spanish-speaking).18 Compared with English-speaking families, fewer Spanish-speaking families participated in medical team discussions on rounds (64.7% vs 76.3%, P = 0.02), were questioned at the beginning of rounds (44.4% vs 56.3%, P = 0.03), or were involved in discussions of discharge requirements (72.2% vs 82.8%, P = 0.02). For resident teams rounding with subspecialists, these discrepancies were amplified (Table 3).18 In a separate bivariate analysis, the study compared the use of interpreters such as care team interpretation, phone interpreters, video remote interpreters, or in-person staff interpreters.18 No significant differences were found in team introductions, discharge criteria/advance directives or orders discussions, daily plan discussions, family involvement, or postround questions among the interpretation groups.18 This suggests the potential for interpreter services to mitigate these disparities and improve the inclusivity of medical rounds for all families, regardless of their language preference.

Table 3.

Effect of language barrier in rounding*

| Criteria | English-speaking families | Spanish-speaking families |

|---|---|---|

| Participation in medical team discussions | 76.3% | 64.7% |

| Initial questioning on rounds | 56.3% | 44.4% |

| Involvement in discharge requirement discussions | 82.8% | 72.2% |

*Based on a study by Ju et al.18

This review examines the benefits and drawbacks of bedside rounding compared to table rounding, focusing on patient satisfaction, healthcare provider communication, resident/medical student learning, and clinical outcomes. We hope to provide insights that can inform healthcare practices and improve patient care by comparing and contrasting these two approaches.

PROS AND CONS OF BEDSIDE AND TABLE ROUNDING

With a recent rise in the importance of patient-centered care, it is vital to discuss the advantages and disadvantages from both the patient and provider perspectives to compare and contrast the two most common medical rounding methods with emphasis on patient participation and satisfaction, teaching and learning, physician communication, and ergonomics of medical rounds. A comprehensive discussion helps us dive deep into health professionals’ perspectives and understand the perceived notions that favor the adoption of table rounds over bedside rounds (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bedside versus table rounds

| Bedside rounds | Table rounds | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient participation and satisfaction |

|

|

| Teaching and learning |

|

|

| Physician communication |

|

|

| Ergonomics of medical rounds |

|

|

Patient participation and satisfaction

Compared to the past, the patient’s role in the discussion of healthcare and treatment plans has dramatically evolved from being a spectator to being a fully participating key player. With the development of patient-centered healthcare system models,19,20 the patient is placed at the system’s center, allowing full participation from decision-making to assessment and evaluation.21 Bedside rounds are crucial for patient participation, satisfaction, and reassurance, as there is an opportunity to align the treatment protocol with the patient’s preferences and requirements. This allows patients to make better decisions and increases their adherence to medical treatment. A key question to ask at this point is whether the patients want to be a part of bedside rounds where they can have a chance to discuss their medical issues better and, more importantly, discuss what they have on their minds.22 The answer is not straightforward; perhaps it seems obvious, but there are challenges depending upon the strength of the doctor-patient relationship. Overall, patients feel more secure and reassured when their doctor visits them and pays attention to their concerns.23 In this way, patients’ preferences are made clear, which reduces anxiety and increases their trust in the healthcare system.24 It is also essential to consider that not all patients like to participate in bedside rounds. They may get wrapped up in the medical jargon or feel overwhelmed while discussing their complex medical information.25 Some issues may be perceived as too sensitive to discuss at the bedside. Bedside rounding was favored by a study on case presentations at the bedside of a pediatric intensive care unit because the parents felt acknowledged, agreed to the treatment protocol, and exhibited higher satisfaction than with a nonbedside presentation.26 Table rounds, on the other hand, do not involve the patients and may take most of the opportunity away from patients to be active participants in their healthcare. Only in some instances, like when a patient is too ill to participate or does not want to participate due to any privacy concerns,27 should table rounds be considered. Prerounding to assess patient preferences regarding rounding style may help to inform the choice of which rounding style to use for that particular patient.28

Teaching and learning

Bedside rounds are essential for interacting with providers and patients and can help develop a good doctor-patient relationship. They enable medical students and residents to acquire valued medical skills, which include conducting patient interviews and performing physical examinations as a part of their medical curriculum. They encourage team-based learning, which can promote healthy multidisciplinary decision-making to tailor specific treatment algorithms.13 The different dimensions of medical practices, such as teaching, learning, and clinical care, can go hand in hand in the setting of bedside rounds.29 Bedside rounds also play a role in patient and family education; for example, in pediatrics, family or parent education is a crucial aspect of delivering high-quality healthcare, as the parents of the pediatric patient are the primary decision-makers.29 Hence, bedside rounding in such cases is vital for family education and can help family members and parents make better decisions for their patients.

However, in a study by Gonzalo et al, the medical housestaff rated bedside rounds as less educational than table rounds, despite being beneficial for patients.30 According to them, the inexperience and disorganized structure of bedside rounds made it challenging for teaching and learning.30 Another case study found that medical students did not participate in the bedside rounds with much enthusiasm. Hence, learning opportunities were missed by both the students and clinicians, thereby undermining the effectiveness of bedside rounds for learning.31 The reasons can be on the learner’s side, such as internal reluctance, discomfort, lack of experience, and the perceived notion of patient harm during bedside teaching,32 or on the patient’s side, such as being too ill, refusing to consent, having privacy concerns, or feeling overwhelmed due to an increased number of students. Therefore, table rounds are preferred in these circumstances, as they solve and instantly overcome the challenges faced in bedside teaching. Table rounds can accommodate physicians, residents, and medical students in a single setting, facilitate the use of technology, and avoid issues regarding patient consent or patient privacy.16 However, one key issue with table rounding is that the participants who are not directly involved in the care of a particular patient or those who are passive listeners have a greater tendency to become distracted or involve themselves in distractions such as internet browsing. This may create a false sense of participation. Therefore, further research on this rounding technique is needed to determine its efficiency.

Physician communication

Bedside rounds are also the center of communication between healthcare workers, particularly nursing staff and physicians. They can provide a set-up to build an excellent doctor-nurse relationship, improving the quality of care, promoting patient-centeredness and shared decision-making, and breaking the hierarchy.33,34 Bedside rounds can also effectively improve physicians’ communication skills, which is particularly important for residents and emerging doctors. In the world of cultural immersion, both patients and providers come from different backgrounds and are unaware of cultural norms and communication barriers, not only at the level of language but also at the level of perception and understanding.35 Therefore, providers must be careful of their cognitive biases and avoid adopting preconceived notions.36 Communication skills (both verbal and nonverbal) hence are the crux of an effective healthcare delivery system, and they can be learned and improved over time in the setting of regular patient interaction during bedside rounds.36 Skilled communication is associated with improved patient satisfaction and self-efficacy and has been observed to decrease physician burnout.37 In contrast, table rounds provide an environment for a comprehensive discussion on the patient’s condition and treatment strategies where providers from different specialties can participate; however, they do not help physicians, particularly residents and medical students, acquire skills such as empathy, cultural awareness, trust building, active listening, relationship building, and problem-solving.38

Ergonomics of medical rounds

It has been found that residents prefer not to round at the bedside due to significant concerns involving increased time of rounding, decreased chances of discussions, higher chances of infection spread, and overcrowding in the wards.2,6 Some of these concerns sound reasonable; however, the basis of these obstacles should be backed by research for their significance in the actual setting. It has been shown that the issue of increased rounding time is just a perception. One study found a statistically significant difference between a preproject survey, in which providers estimated that it would take longer to conduct bedside rounds (11′45″), and postproject analysis, which showed a decrease in average per patient rounding time (9′22″).28 Bedside rounds usually are conducted by medical teams, which comprise physician(s), fellow(s), resident(s), and medical students. They may involve multiple teams from different disciplines for both patient management and the teaching of students. Such group activities may cause overcrowding, which can overwhelm the patients and may become cumbersome and ineffective.39 A solution proposed for this issue is to conduct extra rounds specifically to teach and frame a multidisciplinary rounding cheat sheet for efficient functioning.28,39 However, in the case of failure to employ these methods, table rounds automatically come into the picture as an alternative, encouraging their use.

A better approach could be to refine the existing bedside rounds into more structured ones28,40,41 and incorporate table rounds where they are undoubtedly needed. A proper code of conduct for the entire day could help organize the bedside rounds by prioritizing patients, setting expectations and time limits, ensuring prerounding by interns, medical students, or residents, and using appropriate bedside technology, such as a workstation on wheels.28 As bedside rounds and table rounds are the two corners of the medical rounding system, with bedside rounds being more patient-centered and less provider-convenient and table rounds being less patient-centered and more provider-convenient, a gray area exists in the overlap between the two. Although the optimal rounding style may vary by the healthcare setting and the patient’s needs, it is crucial to follow an evidence-based approach involving both rounding techniques to reach the highest levels of patient-centeredness and provider convenience in order to have an efficacious system of healthcare delivery (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Subtypes of medical rounds: Incorporating the effective use of both bedside and table rounds.

CONCLUSION

The debate between bedside and table rounding is a complex issue among healthcare providers who have different perceptions, requiring careful consideration of multiple factors. Traditional methods like bedside rounding have several benefits, including helping patients understand their illnesses, increasing patient involvement in decision-making, fostering trust, raising patient satisfaction scores, and boosting the confidence of other team members. Under the guidance of the attending, residents and medical students develop their physical examination abilities, professionalism, and patient empathy. Table rounds, in contrast, are more effective in facilitating organized medical education and are considered appropriate for cases where the patient is critically ill or has issues giving consent. It seems feasible to conduct rounds at a table accommodating doctors, residents, and medical students to promote a more detailed discussion of their care, which entails sensitive information about the patient with no difficulties with patient permission or privacy. Table rounding can occasionally be less patient-centered than bedside rounding since patients are not actively engaged in the conversation, restricting the potential of the healthcare team to execute clinical observations and deliver more individualized care. The decision to perform bedside rounds or table rounds should ultimately depend on the patient’s requirements and preferences as well as the particular features of each healthcare facility. Healthcare professionals should thoroughly examine, contrast, and analyze the distinctions between bedside and table rounding and seek to make the overall rounding strategy more structured and organized. By careful consideration of factors such as learners’ needs, patient preferences, and environmental factors like overcrowding, the medical staff can make well-informed choices that prioritize the health of their patients foremost and advance high-quality, patient-centered care. The review concludes that a combination of bedside and table rounds is required for optimal outcomes in patient care and medical education. Healthcare professionals can contribute to ensuring that their patients receive the most effective care by approaching clinical rounds thoughtfully and by using evidence-based practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to acknowledge the guidance of Nikita Garg, Children's Hospital of Michigan, Detroit, USA.

Disclosure statement/Funding

The authors report no funding or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hulland O, Farnan J, Rabinowitz R, et al. What’s the purpose of rounds? A qualitative study examining the perceptions of faculty and students. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(11):892–897. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabinowitz R, Farnan J, Hulland O, et al. Rounds today: a qualitative study of internal medicine and pediatrics resident perceptions. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(4):523–531. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00106.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beigzadeh A, Yamani N, Bahaadinbeigy K, Adibi P.. Challenges and strategies of clinical rounds from the perspective of medical students: a qualitative research. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:6. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_104_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson N, Gibson C, Nowatzke R, Monsma N.. 1175: Bedside rounds or table rounds in the ICU? Crit Care Med. 2018;46(1):571. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000529180.59463.76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruopp MD. Bedside rounds. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(5):344–345. doi: 10.7326/M18-3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merchant NB, Federman DG.. Bedside rounds valued but not preferred: perceptions of internal medicine residents and attending physicians in a diverse academic training program. South Med J. 2017;110(8):531–537. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.000000000000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heip T, Van Hecke A, Malfait S, Van Biesen W, Eeckloo K.. The effects of interdisciplinary bedside rounds on patient centeredness, quality of care, and team collaboration: a systematic review. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(1):e40–e44. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramirez J, Singh J, Williams AA.. Patient satisfaction with bedside teaching rounds compared with nonbedside rounds. South Med J. 2016;109(2):112–115. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ngo TL, Blankenburg R, Yu CE.. Teaching at the bedside: strategies for optimizing education on patient and family centered rounds. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2019;66(4):881–889. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz JI, Gonzalez-Colaso R, Gan G, et al. Structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds improve interprofessional communication and workplace efficiency among residents and nurses on an inpatient internal medicine unit [published online ahead of print, 2021 Jan 12]. J Interprof Care. 2021;1–8. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1863932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNeil C, Muck A, McHugh P, Bebarta V, Adams B.. Bedside rounds versus board rounds in an emergency department [published correction appears in Clin Teach. 2015;12(3):222]. Clin Teach. 2015;12(2):94–98. doi: 10.1111/tct.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pingree EW, Freed JA, Riviello ED, et al. A tale of two rounds: managing conflict during the worst of times in family-centered rounds. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9(7):563–565. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2019-0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratelle JT, Gallagher CN, Sawatsky AP, et al. The effect of bedside rounds on learning outcomes in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2022;97(6):923–930. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalaf Z, Khan S.. Education during ward rounds: systematic review. Interact J Med Res. 2022;11(2):e40580. doi: 10.2196/40580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricotta DN, Smith CC, McConville JF, Leeper CM.. Bedside rounds vs. board rounds in graduate medical education: a narrative review. Am J Med. 2020;133(8):901–906. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solomon JM, Bhattacharyya S, Ali AS, et al. Randomized study of bedside vs hallway rounding: neurology rounding study. Neurology. 2021;97(9):434–442. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichstein PR, Atkinson HH.. Patient-centered bedside rounds and the clinical examination. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ju A, Sedano S, Mackin K, Koh J, Lakshmanan A, Wu S.. Variation in family involvement on rounds between English-speaking and Spanish-speaking families. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(2):132–142. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2021-00622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL.. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA. 1992;267(16):2221–2226. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03480160079038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Constand MK, MacDermid JC, Dal Bello-Haas V, Law M.. Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:271. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guadagnoli E, Ward P.. Patient participation in decision-making. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(3):329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA.. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walton V, Hogden A, Long JC, Johnson JK, Greenfield D.. Patients, health professionals, and the health system: influencers on patients’ participation in ward rounds. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1415–1429. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S211073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ. 2001;322(7284):468–472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7284.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, Roter D, Dobs AS.. The effect of bedside case presentations on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1150–1155. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landry MA, Lafrenaye S, Roy MC, Cyr C.. A randomized, controlled trial of bedside versus conference-room case presentation in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2):275–280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schandl A, Falk AC, Frank C.. Patient participation in the intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;42:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.UNC School of Medicine. Implementing Patient Centered Multidisciplinary Bedside Rounds. https://www.med.unc.edu/medicine/wp-content/uploads/sites/945/2019/01/Implementing-Patient-Centered-Multidisciplinary-Bedside-Rounds.pdf

- 29.Sandhu AK, Amin HJ, McLaughlin K, Lockyer J.. Leading educationally effective family-centered bedside rounds. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):594–599. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00036.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Huang G, Smith C.. The return of bedside rounds: an educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):792–798. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1344-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quilligan S. Learning clinical communication on ward-rounds: an ethnographic case study. Med Teach. 2015;37(2):168–173. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.947926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH.. Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105–110. doi: 10.1080/10401330902791156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalo JD, Kuperman E, Lehman E, Haidet P.. Bedside interprofessional rounds: perceptions of benefits and barriers by internal medicine nursing staff, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):646–651. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato H, Clouser JM, Talari P, et al. Bedside nurses’ perceptions of effective nurse-physician communication in general medical units: a qualitative study. Cureus. 2022;14(5):e25304. J doi: 10.7759/cureus.25304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vidaeff AC, Kerrigan AJ, Monga M.. Cross-cultural barriers to health care. South Med J. 2015;108(1):1–4. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliveros E, Brailovsky Y, Shah KS.. Communication skills: the art of hearing what is not said. JACC Case Rep. 2019;1(3):446–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2019.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boissy A, Windover AK, Bokar D, et al. Communication skills training for physicians improves patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(7):755–761. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3597-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chichirez CM, Purcărea VL.. Interpersonal communication in healthcare. J Med Life. 2018;11(2):119–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tuite DR, Healy D, MacKinnon TS.. Implementing interprofessional bedside rounding at the prequalification stage. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:557–558. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S121999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collett J, Webster E, Gray A, Delany C.. Equipping medical students for ward round learning. Clin Teach. 2022;19(4):316–322. doi: 10.1111/tct.13500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gray AZ, Modak M, Connell T, Enright H.. Structuring ward rounds to enhance education. Clin Teach. 2020;17(3):286–291. doi: 10.1111/tct.13086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]