Abstract

The first molecular and genetic characterization of a biochemical pathway for oxidation of the reduced phosphorus (P) compounds phosphite and hypophosphite is reported. The pathway was identified in Pseudomonas stutzeri WM88, which was chosen for detailed studies from a group of organisms isolated based on their ability to oxidize hypophosphite (+1 valence) and phosphite (+3 valence) to phosphate (+5 valence). The genes required for oxidation of both compounds by P. stutzeri WM88 were cloned on a single ca. 30-kbp DNA fragment by screening for expression in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Two lines of evidence suggest that hypophosphite is oxidized to phosphate via a phosphite intermediate. First, plasmid subclones that conferred oxidation of phosphite, but not hypophosphite, upon heterologous hosts were readily obtained. All plasmid subclones that failed to confer phosphite oxidation also failed to confer hypophosphite oxidation. No subclones that conferred only hypophosphite expression were obtained. Second, various deletion derivatives of the cloned genes were made in vitro and recombined onto the chromosome of P. stutzeri WM88. Two phenotypes were displayed by individual mutants. Mutants with the region encoding phosphite oxidation deleted (based upon the subcloning results) lost the ability to oxidize either phosphite or hypophosphite. Mutants with the region encoding hypophosphite oxidation deleted lost only the ability to oxidize hypophosphite. The phenotypes displayed by these mutants also demonstrate that the cloned genes are responsible for the P oxidation phenotypes displayed by the original P. stutzeri WM88 isolate. The DNA sequences of the minimal regions implicated in oxidation of each compound were determined. The region required for oxidation of phosphite to phosphate putatively encodes a binding-protein-dependent phosphite transporter, an NAD+-dependent phosphite dehydrogenase, and a transcriptional activator of the lysR family. The region required for oxidation of hypophosphite to phosphite putatively encodes a binding-protein-dependent hypophosphite transporter and an α-ketoglutarate-dependent hypophosphite dioxygenase. The finding of genes dedicated to oxidation of reduced P compounds provides further evidence that a redox cycle for P may be important in the metabolism of this essential, and often growth-limiting, nutrient.

Phosphorus plays a central role in the metabolism of all living organisms and is a required nutrient. In addition to its role in innumerable metabolic pathways, it is a component of phospholipids, RNA, DNA, and the principal nucleotide cofactors involved in energy transfer and catalysis in the cell. Despite the ubiquitous role of P in metabolism, the biochemistry of P-containing compounds is generally considered to be quite simple, consisting almost entirely of phosphate-ester formation and hydrolysis. Thus, it not surprising that most P found in living systems is in the form of inorganic phosphate and its esters. However, there are an increasing number of studies showing biochemical reactions of P compounds that do not involve the formation or hydrolysis of phosphate-esters. Some of these reactions involve compounds in which the P is at a lower valence state, suggesting that previously unsuspected P redox reactions may be important in the metabolism of this element.

On earth virtually all known phosphorus exists in the +5 oxidation state. This is true for both inorganic phosphate and the organic phosphate-esters that play a role in the bulk of known P metabolism. Thus, the discovery of phosphonates (+3 valence), and phosphinates (+1 valence) in living systems was somewhat surprising (18). These reduced P compounds, which have direct carbon-phosphorus bonds, are clearly important for the organisms in which they are found. For example, Tetrahymena may possess as much as 30% of its membrane lipids in the form of phosphonolipids (22). It is now known that similar compounds are found in a wide range of organisms, including humans, plants, and bacteria (18). In addition to the discovery of these compounds, there is a variety of evidence suggesting that other reduced P compounds play a role in the metabolism of this element. A number of reports, some dating back centuries, have suggested that phosphine (H3P) is produced during the decomposition of organic material. This toxic, spontaneously flammable gas is equivalent to the most-reduced forms of P (−3 valence). Although these early reports must be considered anecdotal, recent reports have verified natural production of phosphine by using modern methods of chemical analysis. In these studies gas chromatography combined with mass spectroscopy was used to detect phosphine in the atmosphere, in anaerobic harbor sediments, and in sewage treatment facilities (8, 11–14). Other studies have demonstrated the reduction of phosphate in anaerobic soil and during corrosion of metals under anaerobic conditions (19, 38, 40). These data clearly demonstrate that reduction of P occurs in nature. In each case living organisms are suspected to be the causative agents. Recent studies have begun to explore the biochemistry of phosphonate and phosphinate production (34, 36); however, nothing is known about the metabolism of other reduced P compounds.

Other investigations have shown that biologically catalyzed oxidation of reduced P compounds can occur. A number of bacteria have been shown to be capable of oxidizing reduced P compounds when these are provided as the sole source of P. Inorganic phosphite (+3 valence) was oxidized to phosphate by numerous laboratory strains of microorganisms, including prokaryotes such as Escherichia coli, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and several species of Pseudomonas and Rhizobium, as well as one eukaryote, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (1, 6, 26). Hypophosphite (+1 valence) can also be oxidized to phosphate by bacteria (9, 16). As is the case with P reduction, very little is known about the process of P oxidation by living organisms. Partial purification of the responsible enzymes has been achieved for both phosphite and hypophosphite oxidation, from Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus caldolyticus, respectively (16, 27). However, nothing is known about the genetics of these processes, because molecular and genetic techniques for study of the responsible organisms were largely unavailable at the time of these investigations. It was recently shown by genetic methods that the enzyme C-P lyase from E. coli has phosphite oxidase activity (29, 30). However, due to the current inability to assay C-P lyase in vitro, this activity remains uncharacterized biochemically.

These data indicate that metabolic pathways involving redox reactions of P compounds may be quite common in microorganisms, yet the nature of these pathways remains largely unexplored. In no case are both genetic and biochemical data available for a P-oxidizing system. With this goal in mind, we isolated a variety of organisms capable of oxidizing the reduced P compounds phosphite and hypophosphite. In this report the first molecular and genetic characterization of a biochemical pathway for oxidation of these reduced P compounds is presented. Biochemical characterization of the enzymes involved in the pathway will be reported elsewhere.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains used in the study are shown in Table 1. In general, DH5α and DH5α/λpir were used as hosts for cloning experiments, while S17-1 and BW20767 were used as donor strains for conjugation experiments involving broad-host-range plasmids. Plasmids pMMB67EH and pMMB67HE (10) and pDN18 and pDN19 (35) were from David Nunn. Plasmid pLAFR5 (21) was from Stephen Farrand. Plasmid pBEND2 (23) was from Stanley Maloy. Plasmids pTZ18R, pUC4K, and pSL1180 (5) were from Pharmacia (Piscataway, N.J.). Plasmid pBluescript KS(+) was from Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Species and strain or pathovar | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | ||

| S17-1 | RP4-2-Tc::Mu-1kan::Tn7 integrant recA1 proA creB510 hsdR17 endA1 supE44 thi Hpt− Pt+ | 37 |

| BW20767 | RP4-2-Tc::Mu-1kan::Tn7 integrant leu-63::IS10 recA1 zbf-5 creB510 hsdR17 endA1 thi uidA(ΔMluI)::pir+ | 28 |

| DH5α | φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 hsdR17 deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1 | Gibco BRL |

| DH5α/λpir | λpir φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 hsdR17 deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1 | 33 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | ||

| WM88 | Wild type, Hpt+ Pt+ isolate from soil | This study |

| WM536 | Smooth derivative of P. stutzeri WM88, Hpt+ Pt+ | This study |

| WM567 | Spontaneous streptomycin-resistant mutant of P. stutzeri WM536, Hpt+ Pt+ | This study |

| WM581 | del3(BsiWI)::aph of P. stutzeri WM567, Hpt− Pt− | This study |

| WM678 | ins2(AgeI)::aph of P. stutzeri WM567, Hpt+ Pt+ | This study |

| WM679 | ins1(BglII)::aph of P. stutzeri WM567, Hpt+ Pt+ | This study |

| WM680 | del4(NheI)::aph of P. stutzeri WM567, Hpt+ Pt+ | This study |

| WM682 | ins3(AvrII)::aph of P. stutzeri WM567, Hpt+ Pt+ | This study |

| WM688 | del1(SstI-BsiWI)::aph of P. stutzeri WM567, Hpt− Pt− | This study |

| WM691 | del2(SstI-KpnI)::aph of P. stutzeri WM567, Hpt− Pt+ | This study |

| DSM50227 | Wild type, Hpt− Pt+ | ATCC 11607 |

| Stanier 221 | Wild type, Hpt− Pt− | ATCC 17588 |

| Stanier 419 | Wild type, Hpt− Pt− | ATCC 17832 |

| ZoBell 632 | Wild type, Hpt− Pt− | ATCC 14405 |

| Pseudomonas mendocina CH50 | Wild type, Hpt− Pt+ | ATCC 25411 |

| Pseudomonas putida Stanier 90 | Wild type, Hpt− Pt− | ATCC 12633 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | ||

| 192 | Wild type, Hpt− Pt− | Penn State culture collection |

| UIUC-1 | Wild type, Hpt− Pt− | University of Illinois culture collection |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ||

| PAK | Wild type, Hpt− Pt− | D. Nunn |

| PAK Δpil rif | Δpil Rifr Hpt− Pt− | 20 |

| Pseudomonas syringae | ||

| pv. Tomato | Wild type, Hpt− Pt− | D. Nunn |

| pv. Maculicola | Wild type, Hpt− Pt− | D. Nunn |

| pv. Phaseolicola | Wild type, Hpt− Pt− | D. Nunn |

The hypophosphite (Hpt)- and phosphite (Pt)-oxidizing phenotypes were scored by testing each strain for growth on 0.4% glucose–MOPS medium with 0.5 mM hypophosphite or phosphite as the sole P source. Because all organisms require phosphate, growth on these media is indicative of the ability to oxidize the P compound included as a P source. Rifr, rifampin resistant.

Media.

Most media used in the study have been previously reported (39). Minimal A medium was as described in reference 32. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations for E. coli and Pseudomonas stutzeri WM88: kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; tetracycline, 12 μg/ml; and streptomycin, 100 μg/ml. For Pseudomonas aeruginosa, antibiotics were used as follows: carbenicillin (instead of ampicillin), 200 μg/ml; tetracycline, 100 μg/ml; and rifampin, 25 μg/ml. P compounds were prepared fresh and filter sterilized prior to addition to media at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Noble agar (1.6%) was used to solidify media used for testing P oxidation phenotypes (see below). Sucrose-resistant recombinants of strains carrying the Bacillus subtilis sacB gene as a counterselectable marker were selected on agar-solidified medium containing 10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 50 g of sucrose per liter. Denitrification was tested in tightly closed screw cap tubes completely filled with Luria-Bertani broth with and without 0.1% NaNO2 or 0.1% NaNO3.

P oxidation phenotypes.

P oxidation phenotypes were scored by growth on 0.4% glucose–MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) medium with the compound under study supplied at 0.5 mM as the sole P source (29). The ability to oxidize a compound to phosphate allows growth on this medium. Because the amount of P required for growth is relatively small, the contaminating levels of phosphate found in many medium components, especially agar, allow slight background growth of all strains in these media. To control for this variable, the strains in question were always compared to suitable positive and negative controls streaked on the same plate.

NMR analysis of the P compounds used in the study.

One of our concerns in using reduced P compounds as medium components was the known instability of these compounds under aerobic conditions. To address this issue, we examined the stability of phosphite and hypophosphite in stock solutions and in MOPS medium by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Spectra were obtained in 10-mm tubes at ambient temperature by using either a General Electric GN500-NB (pulse time, 55 μs; relaxation delay, 3.5 s) or a General Electric GN300-NB (pulse time, 24 μs; relaxation delay, 4 s) instrument. D2O was added to allow deuterium signal locking to be used. For experiments in which the P concentration ranged from 250 to 1,000 μM, 512 or 1,012 scans were taken for each sample. Fewer scans were used for samples with high P concentrations. No detectable oxidation products of either phosphite or hypophosphite were seen after 2 weeks of incubation under the growth conditions used in this study. Phosphite stock solutions were stable for at least 1 year. However, prolonged storage of hypophosphite stock solutions led to accumulation of phosphite, approaching ca. 50% of the total P after 6 months of storage at 4°C. For this reason, all reduced P stock solutions were prepared fresh, and media containing reduced P compounds were used within 2 weeks of preparation.

DNA methods.

Standard methods were used throughout for isolation and manipulation of plasmid DNA. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from P. stutzeri WM88 by the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method (3). DNA hybridizations were performed as previously described (31). Probes used for hybridization experiments were labeled with [α-32P]dATP by using the Prime-a-Gene kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. DNA sequences were determined from double-stranded templates by automated dye terminator sequencing at the Genetic Engineering Facility, University of Illinois. The initial sequences of each clone were always determined by using standard lacZ forward and reverse primers. The remaining sequences were obtained either with internal primers or from nested deletions constructed with the ExoIII/Mung Bean deletion kit (Stratagene).

Cloning and analysis of 16S rDNA.

16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) from P. stutzeri WM88 was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA with Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) by using the primers 5′-TTGGATCCAGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′ and 5′-GTTGGATCCACGGYTACCTTGTTACGAYT-3′. The PCR products from separate reactions were cloned into pWM73 (28) to generate pWM206 and pWM207. The complete DNA sequences of both clones were determined, and these sequences are in complete agreement. To identify the species, this 16S rDNA sequence was compared to others in the Ribosomal Database Project (http://rdpwww.life.uiuc.edu) by utilizing the collection of analysis tools provided at this Internet site (25).

Plasmid constructions.

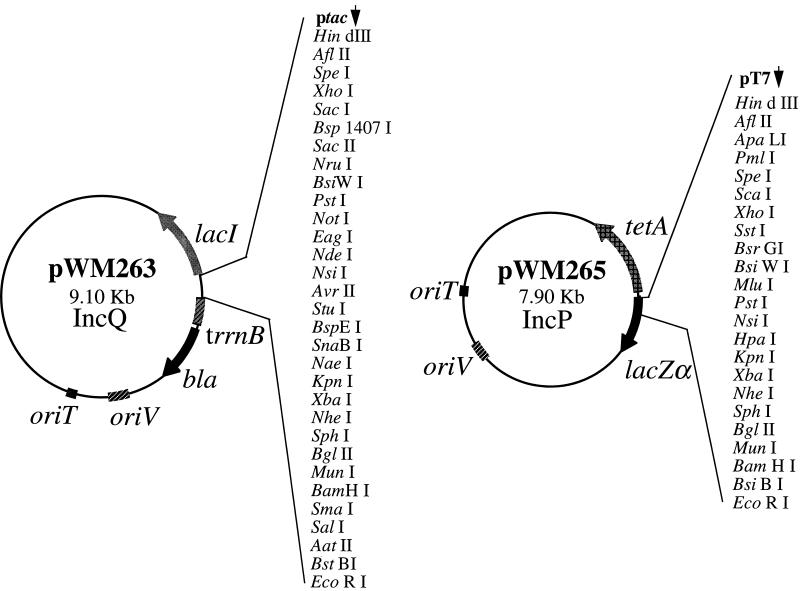

Because of the large number of plasmids constructed during the course of this study, only the basic steps of these constructions are presented here. In many cases the restriction sites found within the polylinker of each vector were used for these constructions (Fig. 1).The first set of plasmids was used in subsequent constructions as vectors or as a source for antibiotic resistance cassettes. The broad-host-range IncQ plasmids pWM263 and pWM264 were constructed by replacement of the EcoRI-HindIII polylinkers of pMMB67HE and pMMB67EH, respectively, with the EcoRI-HindIII polylinker of pSL1180. Similarly, the broad-host-range IncP plasmids pWM265 and pWM266 were constructed by replacement of the EcoRI-HindIII polylinkers of pDN18 and pDN19, respectively, with the EcoRI-HindIII polylinker of pSL1180. Plasmid pJK25, carrying an aph cassette flanked by symmetrical polylinkers, was constructed by insertion of the 1.3-kbp SalI cassette of pUC4K into the SalI site of pBEND2. Plasmid pJK25 greatly simplifies in vitro construction of gene disruptions by allowing isolation of the aph gene cassette (encoding resistance to kanamycin) by digestion with a single restriction endonuclease, chosen from a variety of different possible enzymes.

FIG. 1.

Structures of the broad-host-range plasmids pWM263 and pWM265. The physical maps of the cloning vectors pWM263 and pWM265 are shown. The large number of unique restriction sites in these plasmids greatly facilitates subcloning of DNA inserted into these vectors (see text for details). Only unique restriction sites are shown. Two additional plasmids, pWM264 and pWM266, are similar but with the polylinker in the orientation opposite to that in pWM263 and pWM265, respectively. Genes cloned into pWM263 and pWM264 can be expressed from the tac promoter (ptac) in an IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-dependent manner. The rrnB terminator (trrnB) in these plasmids terminates transcripts originating at ptac. All four plasmids can be mobilized to a variety of recipients from E. coli hosts that carry the tra genes of RP4 in trans. The bla gene encodes resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in pWM263 and pWM264. The tetA gene encodes resistance to tetracycline in pWM265 and pWM266. The lacZα gene of pWM265 and pWM266 is not functional due to stop codons in the large polylinkers of these plasmids.

A cosmid-based genomic library of P. stutzeri WM88 was constructed by ligation of partially Sau3A-digested chromosomal DNA into BamHI-digested pLAFR5. After in vitro packaging of the cosmid library and transfection into S17-1, clones carrying the plasmids pWM234, pWM235, pWM236, pWM237, pWM238, pWM239, and pWM240 were isolated as ones that grew on glucose-MOPS-hypophosphite medium. Plasmid pWM233 is a randomly chosen clone from this library that was used throughout as a negative control for examining growth of various plasmid-bearing strains on hypophosphite and phosphite media.

A set of plasmids carrying various segments of the cosmid clone pWM239 was used as intermediates for subsequent constructions and for testing P oxidation phenotypes in various hosts. Plasmid pWM262 carries the ca. 23-kbp SstI-to-KpnI fragment of pWM239 cloned into the same sites in pTZ18R, while pWM269 carries the ca. 23-kbp SstI-to-KpnI fragment of pWM262 cloned into the same sites of pWM265. Plasmids pWM273 and pWM274 were constructed by cloning the ca. 30-kbp AseI fragment of pWM239 into the NdeI site of pSL1180; the plasmids differ only in the orientation of the insert. Plasmid pWM275 has the XbaI-to-SstI insert of pWM273 cloned into the same sites in pWM265. Plasmid pWM276 has the XbaI-to-MluI insert of pWM273 cloned into the same sites in pWM265. Plasmid pWM277 has the XbaI-to-MluI insert of pWM274 cloned into the same sites in pWM265. Plasmids pWM284 and pWM285 have the 5.8-kbp KpnI fragment of pWM239 cloned into the same site of pWM265 in opposite orientations. A series of deletion derivatives of various plasmids were constructed that removed all DNA between a polylinker restriction site and the most distal site within the inserted region for the same enzyme. These were pWM278 (pWM276 Δ XhoI), pWM279 (pWM275 Δ NsiI), pWM280 (pWM277 Δ NsiI), pWM281 (pWM275 Δ HpaI), pWM282 (pWM279 Δ BamHI), pWM286 (pWM279 Δ NheI), pWM287 (pWM280 Δ EcoRI), pWM288 (pWM277 Δ KpnI), pWM291 (pWM284 Δ ScaI), and pWM292 (pWM285 Δ ScaI).

Another set of plasmids was used for the construction of deletion and insertion mutations in P. stutzeri WM88 as described below. Plasmid pWM296 has the ca. 5.9-kbp XbaI-to-SmaI fragment of pWM284 cloned into SpeI- and SmaI-digested pWM95 (28). Plasmid pWM304 has the ca. 6-kbp AscI fragment of pWM275, made blunt by treatment with deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) and T4 DNA polymerase, cloned into the SmaI site of pWM95. Plasmid pWM305 has the ca. 6-kbp HpaI fragment of pWM275 cloned into the SmaI site of pWM95. Plasmid pWM306 has the ca. 4.5-kbp NotI fragment of pWM275 cloned into the NotI site of pWM95. Plasmid pWM298 was constructed by insertion of the PstI-aph cassette of pUC4K into BsiWI-digested pWM296 after treatment of both vector and insert with dNTPs and T4 DNA polymerase. Plasmid pWM322 was constructed by insertion of the XmaI-aph cassette of pJK25 into the AgeI site of pWM304. Plasmid pWM323 was constructed by insertion of the BamHI-aph cassette of pJK25 into the BglII site of pWM304. Plasmid pWM324 was constructed by insertion of the NheI-aph cassette of pJK25 into pWM305 with its 1.2-kbp NheI fragment deleted. Plasmid pWM326 was constructed by insertion of the NheI-aph cassette of pJK25 into the AvrII site of pWM306. Plasmid pWM260 has the DraI-to-NsiI fragment of pWM239 cloned into PstI- and SmaI-cut pBluescript KS(+). Plasmid pWM261 has the DraI-to-NsiI fragment of pWM238 cloned into PstI- and SmaI-cut pBluescript KS(+). Plasmid pWM338 was constructed by cloning the ca. 1.3-kbp SstI fragment of pWM260 into the SstI site of pWM284. Plasmid pWM340 was constructed by cloning the ca. 5.0-kbp SstI fragment of pWM261 into the SstI site of pWM284. Plasmid pWM342 was constructed by insertion of the EcoRV-aph cassette of pJK25 into pWM338 with an internal ca. 5.0-kbp BsiWI fragment deleted after treatment with dNTPs and T4 DNA polymerase. Plasmid pWM344 was constructed by insertion of the MluI-aph cassette of pJK25 into the MluI site of pWM340. Plasmid pWM346 was constructed by insertion of the ApaI-to-PmlI fragment of pWM342 into ApaI- and SmaI-cut pWM95. Plasmid pWM347 was constructed by insertion of the ApaI-to-PmlI fragment of pWM344 into ApaI- and SmaI-cut pWM95.

The plasmids used for sequence determinations were pWM294 and pWM360. Plasmid pWM294 carries the 5.8-kbp KpnI fragment of pWM239 cloned into the KpnI site of pBluescript KS(+). Plasmid pWM360 was constructed by digestion of pWM262 with XbaI and NheI and subsequent ligation of the compatible XbaI and NheI ends.

Genetic techniques.

In general, conjugation between E. coli donors and P. aeruginosa or P. stutzeri recipients was performed by mixing donor and recipient cells in a 10:1 ratio and incubating overnight on TYE agar. Cells from the mating mixture were then scraped from the surface and resuspended in basal medium, and various aliquots were spread onto selective agar. The genomic library of P. stutzeri WM88 in pLAFR5 was moved into P. aeruginosa PAK en masse by replica plating master plates of the library in E. coli S17-1 onto a lawn of P. aeruginosa PAK. After overnight incubation, these plates were replica plated onto minimal A medium-tetracycline agar to select for exconjugates. In general, the P oxidation phenotypes of various plasmid subclones in P. aeruginosa were examined in strain P. aeruginosa PAK Δpil rif. Plasmids were moved into this strain by conjugation with E. coli BW20767 or S17-1 donors with selection on TYE agar with rifampin in combination with either tetracycline or carbenicillin, as appropriate. Exconjugants of E. coli donors and P. stutzeri WM567 recipients were selected on glucose-MOPS medium with an appropriate antibiotic. Exconjugates of E. coli donors and either WM581, WM688, or WM691 were selected on TYE agar with kanamycin and tetracycline.

In vitro-constructed mutations of cloned genes were recombined onto the P. stutzeri WM567 chromosome as described previously (28). To do this, various segments of the original cosmid clones pWM238 and pWM239 were subcloned into pWM95 (see above). Plasmid pWM95 is a suicide vector that can be transferred to a wide variety of gram-negative organisms by conjugation and carries a counterselectable sacB marker. In vitro deletion and insertion mutations carrying a selectable marker for kanamycin resistance, aph, were made in these clones and recombined onto the chromosome in a two-step process. In the first step, the plasmids carrying the mutations were integrated into the P. stutzeri WM567 chromosome by selection for kanamycin- and streptomycin-resistant exconjugates after mating with E. coli BW20767 donors. In the second step, recombinants that had lost the plasmid backbone were obtained by selection against the plasmid-carried sacB gene by sucrose resistance. Finally, these recombinants were screened for the presence of the desired mutation by scoring kanamycin resistance. The mutant strains reported here and plasmids used for their construction were as follows: P. stutzeri WM581 from pWM298, P. stutzeri WM678 from pWM322, P. stutzeri WM679 from pWM323, P. stutzeri WW680 from pWM324, P. stutzeri WM682 from pWM326, P. stutzeri WM688 from pWM346, and P. stutzeri WM691 from pWM347. Each mutant was verified to have the predicted structure by hybridization of restriction endonuclease-digested genomic DNAs to labeled pJK25 and pWM273, after agarose gel electrophoresis and blotting to positively charged nylon membranes (data not shown).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the P. stutzeri WM88 DNA sequences determined in this study are AF038653 for 16S rDNA, AF061070 for the minimal region required for the oxidation of phosphite to phosphate, and AF061267 for the minimal region required for oxidation of hypophosphite to phosphite.

RESULTS

Isolation of hypophosphite-oxidizing organisms.

All organisms require P in its most-oxidized form, phosphate, for growth. Because of this it is possible to select for organisms capable of oxidizing reduced P compounds to phosphate. Thus, in media containing reduced P compounds as the sole P source, only those organisms capable of oxidizing these reduced compounds to phosphate are able to grow. To enrich for hypophosphite-oxidizing organisms, we inoculated 0.4% glucose–MOPS medium containing 0.5 mM hypophosphite as the sole P source with soil and water samples from a variety of environments. The cultures were incubated aerobically with vigorous agitation at either 30 or 37°C. In every case these enrichments yielded hypophosphite-oxidizing organisms, usually within a few days. The organisms were obtained in pure culture by repeated single-colony isolation on agar-solidified 0.4% glucose–MOPS medium containing 0.5 mM hypophosphite.

Identification and characterization of hypophosphite-oxidizing organisms.

Based on microscopic examination, colony morphology, and growth characteristics, at least 10 different hypophosphite-oxidizing organisms were obtained from these enrichments (data not shown). We chose to concentrate our efforts on one of these organisms that shows particularly robust growth in media with hypophosphite as the sole P source. The doubling time of this isolate is 97 min in succinate-MOPS medium at 37°C with hypophosphite as the sole P source, relative to 75 min in same medium with phosphate as the sole P source. The growth yield is identical in both media. This organism also grows in medium with phosphite as the sole P source and, thus, is also capable of phosphite oxidation (the doubling time in succinate-MOPS medium with phosphite as the sole P source is 120 min). The organism, which was obtained from an enrichment inoculated with local soil, is an oxidase-positive, gram-negative bacterium that forms wrinkled yellow-orange colonies on a variety of media. To identify this organism, we cloned and sequenced its 16S rDNA after PCR amplification. The rDNA sequence was analyzed by using a collection of phylogenetic tools provided by the Ribosomal Database Project (25). These data indicate that the organism is a strain of P. stutzeri, which we designated P. stutzeri WM88. The 16S RNA gene of P. stutzeri WM88 was identical (1,456 of 1,456 bp) to the previously reported sequence from P. stutzeri DSM 50227 (4). This species assignment is fully consistent with a number of other traits, including the classic P. stutzeri trait of denitrification (data not shown).

Oxidation of phosphite and hypophosphite by known bacterial species.

In our original enrichments, P-oxidizing organisms were very similar to P. stutzeri WM88 were isolated from numerous inocula. Our finding that strain WM88 was P. stutzeri led to the question of whether other pseudomonads are capable of P oxidation. We tested the ability of a variety of known Pseudomonas species to oxidize phosphite and hypophosphite as shown by their ability to utilize these compounds as sole P sources. Surprisingly, none of the species tested are able to oxidize hypophosphite, including four known P. stutzeri strains, two strains of P. fluorescens, P. aeruginosa, P. mendocina, P. putida, and three strains of P. syringae (Table 1). Only two, P. stutzeri DSM50227 and P. mendocina CH50, are able to oxidize phosphite. In addition to testing pseudomonads, we screened a large number of common laboratory organisms for use of hypophosphite or phosphite as a source of P. None of these strains are able to utilize hypophosphite, although a few are able to utilize phosphite (data not shown). Among these, only the phenotype of E. coli is relevant to this study. E. coli S17-1 can oxidize phosphite but not hypophosphite. Our finding that E. coli S17-1 is incapable of hypophosphite oxidation is in contrast to that of Lauwers and Heinen, who showed that E. coli 2037 was capable of hypophosphite oxidation (24). These contrasting data may be due to differences in the two E. coli strains.

Cloning of the genes required for hypophosphite oxidation by P. stutzeri WM88.

The genes required for oxidation of phosphite and hypophosphite by P. stutzeri WM88 were cloned by using a strategy similar to that used for the original isolation of the organism. Because E. coli S17-1 is not able to oxidize hypophosphite, it cannot grow on medium with hypophosphite as the sole P source. We constructed a genomic library of P. stutzeri WM88 in the broad-host-range, conjugal cosmid pLAFR5 and tested whether the plasmid clones conferred the ability to grow on medium with hypophosphite as the sole P source upon E. coli hosts. Because we were uncertain whether P. stutzeri genes would be expressed in E. coli, we tested this phenotype in P. aeruginosa PAK as well. Like E. coli, P. aeruginosa PAK is unable to oxidize hypophosphite. After transfection of the cosmid library into E. coli S17-1, individual clones were conjugally transferred to P. aeruginosa PAK by a replica mating technique, as described in Materials and Methods. In all, 2,400 plasmid clones were examined in the two host strains. Seven plasmid clones, pWM234, pWM235, pWM236, pWM237, pWM238, pWM239, and pWM240, that conferred the ability to oxidize hypophosphite upon E. coli S17-1 were isolated; however, 2 to 3 days of incubation on hypophosphite medium was required for this phenotype to be clearly displayed. Five of these seven clones, pWM235, pWM236, pWM237, pWM238, and pWM239, also conferred this trait upon P. aeruginosa PAK. In contrast to that in E. coli, hypophosphite oxidation in P. aeruginosa was quite rapid, with growth on hypophosphite medium occurring within 16 h. No clones that conferred hypophosphite oxidation upon P. aeruginosa and did not also do so for E. coli were obtained.

Restriction analysis of the seven clones that allowed hypophosphite oxidation in E. coli suggests that all carry overlapping fragments of the same chromosomal locus of P. stutzeri WM88 (data not shown). The inability of two of these clones to confer hypophosphite oxidation upon P. aeruginosa can be explained by phenotypic differences in E. coli and P. aeruginosa. Thus, while E. coli S17-1 is incapable of hypophosphite oxidation, it can oxidize phosphite. P. aeruginosa PAK can oxidize neither compound. If hypophosphite is oxidized to phosphate in a pathway that involves a phosphite intermediate, then hypophosphite oxidation in E. coli should require only the genes needed to convert hypophosphite to phosphite. In contrast, P. aeruginosa would require the genes needed to convert hypophosphite to phosphite and those required to convert phosphite to phosphate. In support of this hypothesis, the two clones that fail to confer hypophosphite oxidation upon P. aeruginosa also fail to confer phosphite oxidation upon that host. Each of the five clones that confer hypophosphite oxidation upon P. aeruginosa also confers phosphite oxidation upon that host. Thus, the genes required for phosphite oxidation are also carried on these five clones. Further evidence that hypophosphite is oxidized to phosphate through a phosphite intermediate was provided by a series of subcloning experiments.

Subcloning of genes required for oxidation of phosphite and hypophosphite.

To facilitate subcloning of the genes required for hypophosphite and phosphite oxidation, two sets of broad-host-range plasmids with the polylinker from pSL1180 were constructed (Fig. 1). The polylinker from pSL1180 is comprised of all possible 6-bp palindromes and, therefore, is cut by all known palindrome-recognizing restriction endonucleases. The IncQ plasmids pWM263 and pWM264 are derivatives of the widely used expression vectors pMMB67EH and pMMB67HE with the pSL1180 polylinker. The IncP plasmids pWM265 and pWM266 are derivatives of pDN18 and pDN19 with the pSL1180 polylinker. The large number of unique restriction sites present in these vectors allows removal of DNA from either end of the plasmid insert without the need for rigorous restriction mapping prior to deletion construction. Deletions are easily constructed by digestion with any enzyme that cuts uniquely within the polylinker and any number of times within the insert. After subsequent ligation and transformation, deletion plasmids that lack all DNA between a polylinker restriction site and the most-distal site within the cloned region are recovered. The extent of the deleted DNA fragment(s) is determined subsequently by restriction analysis of the remaining fragment.

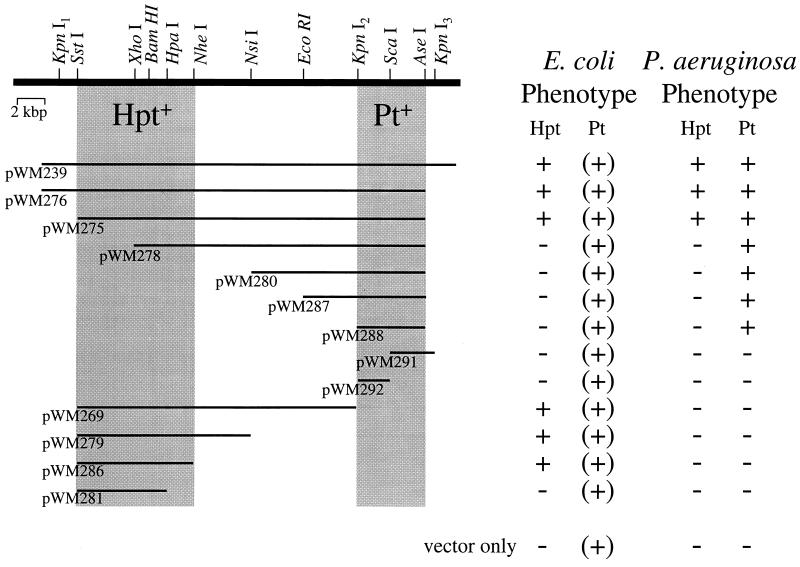

The cosmid clone pWM239 allows hypophosphite oxidation in both E. coli and P. aeruginosa and has an insert of ca. 30 kbp. This plasmid also allows phosphite oxidation by P. aeruginosa. A number of pWM239 subclones with nested deletions were constructed in the broad-host-range vector pWM265 by the method outlined above. These were tested for their abilities to confer hypophosphite and phosphite oxidation upon P. aeruginosa and to confer hypophosphite oxidation upon E. coli (Fig. 2). Because E. coli is a natural phosphite oxidizer, only the hypophosphite oxidation phenotype is relevant in E. coli hosts.

FIG. 2.

Deletion analysis of the hypophosphite- and phosphite-oxidizing functions encoded by the plasmid pWM239. A series of deletion derivatives of the plasmid pWM239 were constructed and tested for expression of the hypophosphite and phosphite oxidation phenotypes in E. coli S17-1 and P. aeruginosa PAK Δpil rif, as described in the text. The ability to confer growth in 0.4% glucose–MOPS medium containing hypophosphite (Hpt) or phosphite (Pt) as the sole phosphorus source is indicative of the ability to oxidize the indicated compound to phosphate. Examination of the P oxidation phenotypes displayed by P. aeruginosa carrying the various deletion plasmids indicates that the shaded region between the KpnI2 and AseI sites is required for Pt oxidation. Further, these data suggest that oxidation of hypophosphite proceeds via a phosphite intermediate. Thus, P. aeruginosa strains carrying plasmids lacking the Pt region are also defective in hypophosphite oxidation. The ability to oxidize Pt in E. coli hosts, indicated by (+), is not related to the plasmids, because E. coli is a natural phosphite oxidizer. Therefore, deletions of the Pt region do not affect hypophosphite oxidation in E. coli, and the minimal region required for this phenotype can be determined by examination of the complementation pattern in this host. Accordingly, the shaded region between the SstI and NheI sites is required for hypophosphite oxidation in E. coli. The thick line at the top represents the cloned region of the P. stutzeri chromosome, with the restriction sites used for construction of individual deletions shown. The flanking restriction sites used for construction of each deletion were provided by the polylinker of the vector pWM265 (Fig. 1). The thin lines represent the remaining insert region of each deletion plasmid. Not all restriction sites within the insert were mapped for each enzyme; therefore, the sites shown are not necessarily unique.

In P. aeruginosa the phosphite and hypophosphite oxidation phenotypes were readily separable. Strains carrying subclones that removed the right end of the pWM239 insert were unable to oxidize either compound, whereas strains carrying subclones that removed the left end of the insert lost only the ability to oxidize hypophosphite (Fig. 2). Clones with large deletions of the left end, beyond the KpnI2 site, are also unable to express phosphite oxidation. These results support the notion that hypophosphite oxidation proceeds through a phosphite intermediate. Further, the data indicate that the proposed gene(s) for oxidation of phosphite to phosphate resides in the right end of the pWM239 insert, between the KpnI2 and AseI sites, and that the gene(s) for oxidation of hypophosphite to phosphite resides in the left end of the insert.

This interpretation is supported by the phenotypes of the same clones in E. coli. Thus, because E. coli is a natural phosphite oxidizer, there is no effect of moderate-sized deletions in the right end of the insert (i.e., the region shown to be important for phosphite oxidation in P. stutzeri). However, plasmids with deletions of the left end (beyond the XhoI site) lose the ability to confer oxidation of hypophosphite. Clones with very large deletions of the right end (beyond the NheI site) are also unable to oxidize hypophosphite in E. coli and delimit the region required for the phenotype. Therefore, the genes required for oxidation of hypophosphite to phosphite in this host are localized between the SstI and NheI sites at the left end of the insert.

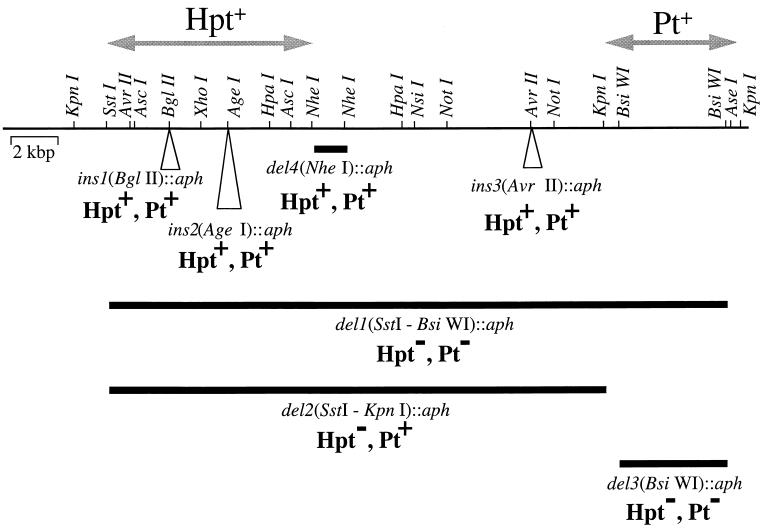

Construction and phenotypic characterization of P. stutzeri WM88 mutants unable to oxidize phosphite and hypophosphite.

To verify that the cloned genes described above are responsible for the observed traits of phosphite and hypophosphite oxidation by P. stutzeri WM88, we constructed a variety of deletion and insertion mutations within these genes and recombined them into the original host as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 3). The observed hypophosphite and phosphite oxidation phenotypes of these mutants are completely consistent with the hypothesis that hypophosphite is oxidized through a phosphite intermediate and verify that the cloned genes were indeed responsible for the ability of P. stutzeri WM88 to oxidize these compounds. These phenotypes also fully support the conclusion from the subcloning experiments as to the locations of the genes required for each trait.

FIG. 3.

P. stutzeri WM88 chromosomal mutations in the region linked to P oxidation phenotypes. The regions of the P. stutzeri WM88 chromosome putatively required for oxidation of hypophosphite (Hpt) and phosphite (Pt) (arrows) were identified by complementation of heterologous hosts (see the text and Fig. 2). Deletion and insertion mutations in clones of this genomic region were constructed in vitro and recombined onto the P. stutzeri WM88 chromosome as described in the text. The P oxidation phenotypes of these mutants were examined by scoring the ability to grow on media containing either Hpt or Pt as the sole P source as described in the text. These phenotypes confirm that the genes carried in this region are responsible for the oxidation of phosphite and hypophosphite by the original isolate (see text for discussion). The thin line at the top indicates the chromosomal region of P. stutzeri under study, with relevant restriction sites shown. Not all sites for each enzyme have been mapped; therefore, the sites shown are not necessarily unique. The thick lines below this represent the extents of the in vitro-constructed deletion mutations. The triangles show the sites of insertion mutations.

Accordingly, a deletion mutation, del1(SstI-BsiWI)::aph, spanning the entire region results in the inability to oxidize either hypophosphite or phosphite. A deletion of just the region thought to encode phosphite oxidation, del3(BsiWI)::aph, also results in the inability to oxidize either compound. This is the expected phenotype of such a deletion if hypophosphite is oxidized via a phosphite intermediate. A mutant carrying a deletion of the region thought to encode hypophosphite oxidation, del2(SstI-KpnI)::aph, retains the ability to oxidize phosphite while losing the ability to oxidize hypophosphite. Other deletion and insertion mutations had no P oxidation phenotypes. This is notable because deletions on both sides of the ins2(AgeI)::aph mutation result in the loss of hypophosphite oxidation when the genes are expressed in E. coli (Fig. 2).

Complementation of P. stutzeri deletion mutants with nested plasmid deletions.

The final verification of the DNA regions required for oxidation of hypophosphite and phosphite was provided by complementation of the del1, del2, and del3 mutations (Fig. 3) in the native P. stutzeri host with selected plasmids from the deletion series (Fig. 2) described above. With the exception of the size of the fragment required for hypophosphite oxidation by P. stutzeri, these data are completely consistent with the results obtained from expression of the genes in heterologous hosts (Table 2).The data with respect to phosphite oxidation are essentially identical for the native and heterologous hosts. Thus, both the del1 mutation, which removes the entire region, and the del3 mutation, which removes only the region implicated in phosphite oxidation, can be complemented for the phosphite oxidation phenotype by pWM288. This plasmid carries the KpnI-to-AseI fragment previously shown to be the minimal DNA fragment capable of conferring phosphite oxidation upon the heterologous host P. aeruginosa. The reason for the slower growth of del1 hosts carrying pWM239, pWM276, and pWM275 in phosphite medium is unclear; however, these strains are clearly able to oxidize phosphite. This effect is not seen with the same plasmids in the del3 host.

TABLE 2.

P oxidation phenotypes of plasmid-complemented P. stutzeri mutantsa

| Plasmid | Phenotypeb of strain:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WM581 [del3(BsiWI)]

|

WM691 [del2(SstI-KpnI)]

|

WM688 [del1(SstI-BsiWI)]

|

||||

| Hpt | Pt | Hpt | Pt | Hpt | Pt | |

| None | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| pWM239 | + | + | + | + | + | +/− |

| pWM276 | + | + | + | + | + | +/− |

| pWM275 | + | + | + | + | + | +/− |

| pWM278 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| pWM280 | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| pWM287 | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| pWM288 | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| pWM269 | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| pWM279 | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| pWM286 | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| pWM281 | − | − | − | + | − | − |

Strains tested were exconjugates of the indicated recipient P. stutzeri strains with E. coli S17-1 donors carrying the indicated broad-host-range plasmid. See Fig. 2 for the physical structure of each plasmid and Fig. 3 for the extents of the indicated deletions.

Oxidation of reduced P compounds to phosphate was scored by testing each strain for growth on 0.4% glucose–MOPS medium with 0.5 mM hypophosphite (Hpt) or phosphite (Pt) as the sole P source. Because all organisms require phosphate, growth on these media is indicative of the ability to oxidize the P compound included as a P source. +, growth within 24 h at 37°C; +/−, growth within 72 h; −, no growth within 72 h. All strains tested grew in the identical medium supplemented with 0.5 mM phosphate.

In contrast, complementation of hypophosphite oxidation requires a smaller DNA fragment in P. stutzeri than is required by heterologous hosts for expression of this phenotype. As was seen for the heterologous hosts, oxidation of hypophosphite in P. stutzeri requires the ability to oxidize phosphite. This ability can be provided either by genes encoded on the complementing plasmid in the del1 host (a situation similar to complementation of P. aeruginosa) or, in the case of the del2 host, by genes remaining on the chromosome (a situation similar to complementation in E. coli). Thus, complementation of the del1 mutation for hypophosphite oxidation requires plasmid-carried genes for oxidation of both compounds and is seen only with plasmids whose right end includes the KpnI-to-AseI fragment required for phosphite oxidation. The left end of these plasmids, which provides the functions required for hypophosphite oxidation, differs from that defined by expression of the phenotype in heterologous hosts. Thus, plasmid pWM278, with a deletion extending to the XhoI site, does not confer hypophosphite oxidation upon E. coli and P. aeruginosa but does complement the P. stutzeri del1 mutation. Therefore, a function encoded in this region is required in the heterologous host but not in the native host. The right end of the region required for oxidation of hypophosphite to phosphite can be defined by examination of the complementation pattern in the del2 host, which carries phosphite oxidation functions on the chromosome. These results are the same as previously seen in E. coli; i.e., deletions of the right end beyond the NheI site abolish complementation of the del2 mutation for hypophosphite oxidation. Thus, in P. stutzeri the minimal DNA fragment allowing oxidation of hypophosphite to phosphite spans the XhoI-to-NheI sites shown in Fig. 2, whereas a slightly larger fragment, SstI to NheI, is required in E. coli.

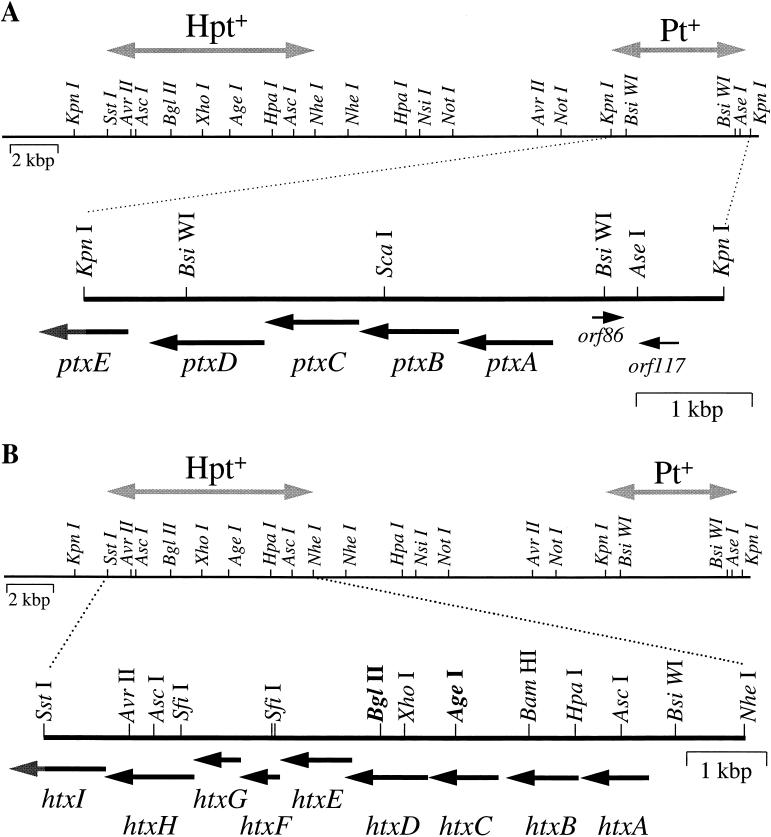

DNA sequence analysis of the minimal region required for phosphite oxidation.

The data presented above demonstrate that the 5.6-kbp KpnI fragment localized to the right end of the pWM239 insert carries the functions required for oxidation of phosphite to phosphate by P. stutzeri WM88. To gain further insight into the nature of these functions, the complete DNA sequence of this region, carried in pWM294, was determined as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 4A and Table 3). Seven open reading frames (ORFs) encoding products with significant homology to proteins in the sequence databases were identified in this sequence. Only six of these ORFs reside within the AseI-to-KpnI fragment shown to carry the functions required for oxidation of phosphite to phosphate. Five of these, designated ptxA to ptxE (for phosphite oxidation) are likely to be involved in oxidation of phosphite to phosphate, because their products exhibit homology to proteins of known functions that suggest functions consistent with roles in P oxidation. Accordingly, PtxA, PtxB, and PtxC are likely to comprise a binding-protein-dependent phosphite transporter. PtxD is homologous to the family of d-isomer-specific 2-ketoacid dehydrogenases (15), suggesting that it may be an NAD-dependent phosphite dehydrogenase. PtxD exhibits 27 to 33% identity to various members of the family, including conservation of the NAD binding site and important catalytic residues (data not shown). The ptxE gene (truncated in this sequence) appears to encode a lysR family transcriptional regulator. The ptxABCDE′ genes probably comprise a transcriptional unit. The genes overlap each other by a few bases (in the case of ptxA-ptxB and ptxD-ptxE) or are separated by at most 8 bp (ptxB-ptxC and ptxC-ptxD). The remaining two ORFs, orf86 and orf117, are homologous to a family of site-specific recombinases (2) and to a protein of unknown function in E. coli, respectively. Orf117 is not required for phosphite oxidation, because it lies outside the required region as defined by heterologous expression. A role for Orf86 in phosphite oxidation is formally possible but seems unlikely.

FIG. 4.

Physical structures of DNA fragments shown to be required for oxidation of phosphite and hypophosphite by P. stutzeri WM88. The complete DNA sequences of both fragments were determined as described in the text. (GenBank accession no. AF061070 and AF061267). (A) Structure of a 5.6-kbp KpnI fragment encoding functions required for oxidation of phosphite to phosphate in P. stutzeri WM88. Seven ORFs, indicated by arrows, were identified within this sequence. The ptxE gene is truncated in this clone, as indicated by the partially shaded arrow. Five of these genes, designated ptxA through ptxE, are likely to be involved in oxidation of phosphite and probably form a single transcriptional unit. PtxABC probably comprise a binding-protein-dependent transport system for the uptake of phosphite. PtxD is probably an NAD+-dependent phosphite dehydrogenase, and PtxE is probably a transcriptional regulator for the ptxABCDE operon. (B) Structure of an 8.9-kbp SstI-to-NheI fragment encoding functions required for oxidation of hypophosphite to phosphite in P. stutzeri WM88. Nine ORFs, indicated by arrows and designated htxA through htxI, are likely to form a single transcriptional unit. Relevant restriction sites used for various plasmid constructions are shown. The BglII and AgeI sites shown in boldface were used as insertion sites for gene disruption experiments (Fig. 3). HtxA is a putative α-ketoglutarate-dependent hypophosphite dioxygenase. HtxBCDE comprise a putative binding-protein-dependent hypophosphite transporter. The remaining genes encode subunits of a putative C-P lyase but are not required for oxidation of hypophosphite. The partially shaded arrow indicates that the htxI gene is truncated in this sequence. See the text and Table 3 for details. Approximately 15 kbp separates the two regions. This 15-kbp region is not required for oxidation of either compound and was not characterized.

TABLE 3.

Putative genes involved in oxidation of phosphite and hypophosphite

| Putative gene | Mol wt of predicted product | Proposed function | Closest homolog (probability)a | Signatureb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ptxA | 29,630 | Binding-protein-dependent phosphite transporter, ATPase component | Rhizobium meliloti PhoC, phosphate transporter subunit (9e − 50) | ABC family, 152–156 |

| ptxB | 31,262 | Binding-protein-dependent phosphite transporter, binding protein component | Escherichia coli PhnD, phosphonate transporter subunit (8e − 13) | |

| ptxC | 29,376 | Binding-protein-dependent phosphite transporter, inner membrane component | Escherichia coli PhnE, phosphonate transporter subunit (8e − 37) | Binding-protein-dependent transport system inner membrane component, 173–201 |

| ptxD | 36,391 | Phosphite dehydrogenase | Escherichia coli putative 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase, o365 (5e − 38) | d-Isomer-specific 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase signature 3, 226–242 |

| ptxE | Truncated | Transcriptional regulator for ptx operon | Methanococcus jannaschii transcriptional regulator homolog MJ0300 (2.1e − 11) | lysR family, 18–48 |

| htxA | 32,482 | α-Ketoglutarate-dependent hypophosphite dioxygenase | Dactylosporangium sp. l-proline 4-hydroxylase (2e − 11) | |

| htxB | 32,702 | Binding-protein-dependent hypophosphite transporter, binding protein component | Rhizobium meliloti PhoD, phosphate transporter subunit (8e − 14) | |

| htxC | 30,804 | Binding-protein-dependent hypophosphite transporter, inner membrane component | Escherichia coli PhnE, phosphonate transporter subunit (3e − 39) | |

| htxD | 37,286 | Binding-protein-dependent hypophosphite transporter, ATPase component | Escherichia coli PhnC, phosphonate transporter subunit (2e − 42) | ABC transporter family, 149–163 |

| htxE | 29,379 | Binding-protein-dependent hypophosphite transporter, inner membrane component | Rhizobium meliloti PhoE, phosphate transporter subunit (6e − 25) | |

| htxF | 16,701 | C-P lyase subunit | Rhizobium meliloti PhnG, putative C-P lyase subunit (0.023) | |

| htxG | 21,082 | C-P lyase subunit | Escherichia coli PhnH, putative C-P lyase subunit (7e − 11) | |

| htxH | 40,300 | C-P lyase subunit | Escherichia coli PhnI, putative C-P lyase subunit (3e − 67) | |

| htxI | Truncated | C-P lyase subunit | Escherichia coli PhnJ, putative C-P lyase subunit (4e − 81) | |

| orf117 | 12,663 | Escherichia coli hypothetical protein o123 (2e − 22) | ||

| orf86 | Site-specific recombinase | Lactobacillus helveticus putative site-specific recombinase (3e − 4) |

Closest homologs were determined by Blast searches against the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant protein database on 24 April 1998. The probability represents the smallest sum score of the closest homolog identified in these searches.

Signature sequences are from the PROSITE database. The numbers indicate the position of the conserved signature sequence for the indicated protein family.

DNA sequence analysis of the minimal region required for hypophosphite oxidation.

The subcloning and complementation experiments outlined above demonstrate that the SstI-to-NheI fragment at the left end of pWM239 encodes genes involved in the oxidation of hypophosphite to phosphite. Therefore, the complete DNA sequence of this fragment, carried in pWM360, was also determined. Nine ORFs, designated htxA, htxB, htxC, htxD, htxE, htxF, htxG, htxH, and htxI (for hypophosphite oxidation), were identified in this sequence (Fig. 4B and Table 3). The nine genes are all transcribed in the same direction and probably form a transcriptional unit. The putative protein products of each of these ORFs display homology to proteins of known functions, suggesting possible roles for these genes in P. stutzeri WM88. The htxA gene is probably required for hypophosphite oxidation, because plasmids lacking this gene (deletion of the HpaI-to-NheI fragment) fail to confer hypophosphite oxidation upon E. coli or P. stutzeri del2 (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Further, this is the only clearly identifiable ORF within the HpaI-to-NheI fragment. HtxA is homologous to a family of α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases that catalyze the oxidation of their respective substrates by using O2 as the immediate electron acceptor (7). Most notably HtxA is 26.2% identical and 33.4% similar to proline hydroxylase from Dactylosporangium. Importantly, the sequence conservation between the two proteins includes regions shown to be important for substrate binding in other members of the family (data not shown). Based on its homology to this family of proteins and on the demonstration that the gene encoding this protein is required for hypophosphite oxidation, it is probable that HtxA is an α-ketoglutarate-dependent hypophosphite dioxygenase.

The roles, if any, in hypophosphite oxidation for the remaining ORFs in this sequence are less certain. The products of the htxB, htxC, htxD, and htxE genes appear to comprise a binding-protein-dependent transporter similar to the PtxABC transporter described above. This transporter is not required for oxidation of hypophosphite by P. stutzeri, as shown by the lack of a phenotype for the ins1 and ins2 mutations in the htxD and htxC genes, respectively. This is also seen by complementation of the del1 and del2 mutations by pWM278, a plasmid that does not carry htxC and htxE (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Despite this, HtxBCDE probably comprise a binding-protein-dependent transporter capable of hypophosphite uptake, because the genes encoding these proteins are required for hypophosphite oxidation in both E. coli and P. aeruginosa; i.e., pWM278 fails to confer hypophosphite oxidation upon these hosts (Fig. 2). A recently constructed plasmid carrying only htxA, htxB, htxC, htxD, and htxE does confer hypophosphite oxidation upon E. coli, demonstrating that the failure of pWM278 to confer this phenotype is specific to loss of the putative transporter and not to loss of the htxF, htxG, htxH, and htxI genes (data not shown).

The htxF, htxG, htxH, and htxI genes are strikingly similar to the phnG, phnH, phnI, and phnJ genes, respectively, of both E. coli and Rhizobium meliloti. This similarity extends to conservation of the gene order as well as protein sequence. These genes are known to be involved in the metabolism of phosphonates and are thought to encode subunits of the enzyme C-P lyase (30). However, C-P lyase activity requires five additional genes that are not present on any of the plasmids characterized in this study. Further, none of the plasmids used in the study are capable of complementing an E. coli C-P lyase deletion mutation (data not shown). Whether the htxF, htxG, htxH, and htxI genes are involved in C-P lyase activity and whether C-P lyase activity is involved in oxidation of hypophosphite are unclear at this time. Despite their homology to subunits of the E. coli and R. meliloti C-P lyases, deletion of the genes encoding HtxF, HtxG, HtxH, and HtxI does not result in the loss of C-P lyase activity in P. stutzeri WM88 (data not shown).

The DNA sequences of both regions have a G+C content of 59.9%, which falls within the widely variable range (60 to 66%) known for species of P. stutzeri. Codon usage in the 16 ORFs identified in these sequences is also typical for P. stutzeri; however, this result must be viewed with caution, because only 44 P. stutzeri protein-coding regions are represented in the standard databases.

DISCUSSION

Relatively few biologically mediated reactions involving oxidation or reduction of P are known. It seems likely, however, that this dearth of knowledge does not reflect the absence of such reactions in nature. On the contrary, reduced P compounds (phosphonates and phosphinates) are known to be common in many organisms (18), and production of the most-reduced P compound, phosphine, in natural systems has been clearly demonstrated (8, 11–14). Further, P-oxidizing organisms have been previously isolated (6, 9, 16). Our own studies suggest that P-oxidizing organisms may, in fact, be quite common. We inoculated numerous enrichments designed to select organisms capable of oxidizing hypophosphite to phosphate by use of this reduced compound as the sole P source. In every case these enrichments yielded P-oxidizing organisms, usually within a few days. Preliminary characterization of these organisms indicated that many species were represented. It must be noted, however, that none of the laboratory strains were tested displayed this phenotype, including several strains known to be of the same species as one of our isolates, P. stutzeri WM88. One of these, P. stutzeri DSM50227, is very similar to P. stutzeri WM88 as shown by its identical 16S RNA sequence. Interestingly, P. stutzeri DSM50227 was one of only two pseudomonads tested that was able to oxidize phosphite, a trait that we showed was essential for oxidation of hypophosphite by P. stutzeri WM88. We are uncertain of the reason that so many laboratory strains were unable to oxidize hypophosphite, while at the same time it was so simple to isolate related strains from nature that could. This is probably a reflection of the power of the enrichment technique used for isolation of these organisms; however, it is not uncommon for laboratory strains to differ from their wild counterparts.

The data presented indicate that P. stutzeri WM88 oxidizes hypophosphite to phosphate in a two-step pathway via a phosphite intermediate. Two lines of evidence support this conclusion. First, all plasmid clones that confer hypophosphite oxidation upon the heterologous host P. aeruginosa also confer the ability to oxidize phosphite. Conversely, all subclones that lack the ability to confer phosphite oxidation also lack the ability to confer hypophosphite oxidation. Second, similar results were obtained for mutants of P. stutzeri WM88. Thus, mutants unable to oxidize phosphite are always unable to oxidize hypophosphite, while mutants unable to oxidize hypophosphite but still able to oxidize phosphite are readily obtained. Complementation of these P. stutzeri mutants with the same plasmids further supports this conclusion.

The available evidence suggests that two novel P-oxidizing enzymes are involved in the process. First, the HtxA protein is likely to be an α-ketoglutarate-dependent hypophosphite dioxygenase, based on its similarity to other known proteins of this type (7). Such an enzyme would use molecular oxygen as the direct electron acceptor for oxidation of hypophosphite by using α-ketoglutarate as a cosubstrate and producing phosphite, succinate, and CO2 as products. Although we have no direct evidence that this reaction occurs, we have recently shown that P. stutzeri is incapable of hypophosphite oxidation when grown anaerobically with nitrate as an electron acceptor. Phosphite oxidation was not impaired under similar growth conditions (data not shown). This datum suggests that oxygen may be required for hypophosphite oxidation and supports the conclusion that HtxA may be a dioxygenase. Oxidation of phosphite is likely to occur by the action of an NAD-dependent phosphite dehydrogenase activity encoded by the ptxD gene. PtxD is highly homologous to a large number of proteins of this general type, most notably those involved in the oxidation of 2-ketoacids (15). This enzyme may be similar to a previously described enzyme from P. fluorescens; however, that enzyme was never characterized in detail with purified protein, nor was its gene identified (27). We have recently demonstrated that PtxD possesses the predicted enzymatic activity and are currently purifying the protein to allow detailed biochemical characterization of this enzyme. These data will be reported elsewhere.

Two binding-protein-dependent transporters are likely to be involved in the oxidation of phosphite and hypophosphite in P. stutzeri WM88. The PtxABC transporter is probably involved in the uptake of phosphite, whereas the HtxBCDE transporter is probably involved in the uptake of hypophosphite. Each of these transporters is homologous to the E. coli PhnCDE transporter, which is responsible for uptake of phosphonates. This is relevant in that phosphonates are structurally similar to both phosphite and hypophosphite. Further, the E. coli PhnCDE transporter is known to transport phosphite in addition to phosphonates (29). Our evidence directly supports the conclusion that the HtxBCDE transporter is involved in uptake of hypophosphite in E. coli and P. aeruginosa. The observation that the genes encoding the transporter are not required for hypophosphite oxidation in P. stutzeri demonstrates that an additional hypophosphite transporter is present in the genome of this organism.

One possible explanation for the ability to oxidize phosphite and hypophosphite is that a broad-specificity C-P lyase may be responsible for the oxidation reactions. Because E. coli C-P lyase has been shown to oxidize phosphite to phosphate (30), it seems possible that other C-P lyases may be capable of oxidizing either phosphite or hypophosphite. Indeed, we demonstrated that genes in the same operon as htxA are highly homologous to E. coli and R. meliloti genes which encode C-P lyase subunits. Although these genes are not required for hypophosphite oxidation in P. stutzeri WM88, a role for C-P lyase cannot be excluded. Despite removal of the htxF, htxG, and htxH genes and part of the htxI gene, the deletion mutants we constructed retain C-P lyase activity and thus carry a second C-P lyase locus elsewhere on the genome. Further, the E. coli and P. aeruginosa hosts used for our complementation studies both contain the genes encoding C-P lyase. Regardless of this possibility, the predicted roles for HtxA and PtxD should be sufficient for hypophosphite and phosphite oxidation without invoking a role for C-P lyase. Unambiguous demonstration of the function of the genes isolated from P. stutzeri WM88 will await the results of studies now under way on the biochemical characterization of the enzymes they encode.

Whether or not C-P lyase is involved in oxidation of reduced P compounds in P. stutzeri WM88, the observed linkage of genes encoding a putative C-P lyase and the P-oxidizing enzymes found in this system is intriguing. C-P lyase is one of the only enzymes known to catalyze oxidation of reduced P compounds. It is capable of catalyzing the production of phosphate from either phosphonates or phosphite (30). Further, phosphonate and phosphinate production are among the few studied examples of biological production of a reduced P compound (34, 36). There is a known linkage between phosphonate production and the production of one of the reduced P substrates oxidized by P. stutzeri WM88, namely, phosphite. The common soil bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus produces the phosphinate antibiotic bialaphos. One of the known intermediates in the biosynthesis of this compound is phosphonoformate, an unstable compound that spontaneously decomposes to CO2 and phosphite (34). Finally, although P. stutzeri PtxD is homologous to a large number of dehydrogenases at the protein level, its gene is not generally homologous to the respective genes at the DNA level (data not shown). One key exception is the homology of ptxD to a gene within a cluster of S. hygroscopicus genes involved in the biosynthesis of bialaphos, encoding a putative dehydrogenase thought to catalyze the oxidation of hydroxymethylphosphonate to phosphonoformate (17). Taken together, these data suggest a connection, albeit of uncertain nature, between the biosynthesis and catabolism of C-P bonds and the oxidation of the reduced P compounds phosphite and hypophosphite.

The isolation of numerous organisms capable of oxidizing reduced P compounds provides new evidence that a P redox cycle exists in nature. The large genomic fragment we isolated from P. stutzeri carries genes that allow assimilation of P from two or three types of reduced P compounds, i.e., phosphite, hypophosphite, and possibly phosphonates. Thus, it represents a chromosomal region largely dedicated to metabolism of reduced P compounds. The finding of genes that appear to be specifically dedicated to this process is a clear indication that these compounds are present in the environment and that it is advantageous for organisms to be able to utilize them. Further, our NMR studies demonstrate that hypophosphite spontaneously oxidizes to phosphite within a few months under aerobic conditions. Therefore, there is a continuous, or at least repetitive, production of these compounds in nature. Oxidation of reduced P compounds may serve two purposes. First, there is a great deal of energy available from these reactions. The ability to harness this energy would certainly be advantageous to an organism that possessed it. Second, phosphate is a limiting nutrient in many ecosystems. Thus, the ability to oxidize any reduced P compounds to phosphate is also of obvious merit.

The source of these reduced P compounds is of great interest but remains unclear at this time. Numerous reports demonstrating the presence of the most-reduced form of P, phosphine, in the environment now exist. We, and others, have shown the production of such compounds under anaerobic conditions; however, these experiments do not always result in the production of reduced P compounds (40). Thus, the environmental conditions resulting in P reduction remain to be determined. The overall importance of P redox cycling in nature is also unclear at this time, although the flux of P through this redox cycle can apparently be quite high, as shown by the loss of up to 45% of the incoming P as volatile compounds in some sewage treatment facilities (8). Further study of this intriguing process is clearly required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Barry L. Wanner, David N. Nunn, Stephen Farrand, and Stanley R. Maloy for kindly providing bacterial strains and plasmids used in the study and Amaya Garcia for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grant GM51334 from the National Institutes of Health. W.W.M. was supported by NRSA fellowship 5 F32 GM16504-3.

Footnotes

Corresponding author. Mailing address: Department of Microbiology, University of Illinois, B103 Chemical and Life Science Laboratory, 601 S. Goodwin, Urbana, IL 61801. Phone: (217) 244-1943. Fax: (217) 244-6697. E-mail: metcalf@uiuc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams F, Conrad J P. Transition of phosphite to phosphate in soils. Soil Sci. 1953;75:361–371. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argos P, Landy A, Abremski K, Egan J B, Haggard-Ljungquist E, Hoess R H, Kahn M L, Kalionis B, Narayana S V, de Pierson L S, et al. The integrase family of site-specific recombinases: regional similarities and global diversity. EMBO J. 1986;5:433–440. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. 1 and 2. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennasar A, Rossello-Mora R, Lalucat J, Moore E R. 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis relative to genomovars of Pseudomonas stutzeri and proposal of Pseudomonas balearica sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:200–205. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brosius J. Superpolylinkers in cloning and expression vectors. DNA. 1989;8:759–777. doi: 10.1089/dna.1989.8.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casida L E., Jr Microbial oxidation and utilization of orthophosphite during growth. J Bacteriol. 1960;80:237–241. doi: 10.1128/jb.80.2.237-241.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Carolis E, De Luca V. 2-Oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase and related enzymes: biochemical characterization. Phytochemistry. 1994;36:1093–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)89621-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devai I, Felfoldy L, Wittner I, Plosz S. Detection of phosphine: new aspects of the phosphorus cycle in the hydrosphere. Nature. 1988;333:343–345. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster T L, Winans L, Jr, Helms S J. Anaerobic utilization of phosphite and hypophosphite by Bacillus sp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:937–944. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.5.937-944.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furste J P, Pansegrau W, Frank R, Blocker H, Scholz P, Bagdasarian M, Lanka E. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene. 1986;48:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gassman G, Glindemann D. Phosphane (PH3) in the biosphere. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1993;32:761–763. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gassman G, Schorn F. Phosphine from harbor surface sediments. Naturwissenschaften. 1993;80:78–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gassman G, van Beusekom J E E, Glindeman D. Offshore atmospheric phosphine. Naturwissenschaften. 1996;83:129–131. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glindemann D, Bergman A, Stottmeister U, Gassman G. Phosphine in the lower troposphere. Naturwissenschaften. 1996;83:131–133. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant G A. A new family of 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;165:1371–1374. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92755-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinen W, Lauwers A M. Hypophosphite oxidase from Bacillus caldolyticus. Arch Microbiol. 1974;95:267–274. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hidaka T, Hidaka M, Seto H. Studies on the biosynthesis of bialaphos (SF-1293). 14. Nucleotide sequence of the phophoenolpyruvate phosphonomutase isolated from a bialophos producing organism, Streptomyces hygroscopicus, and its expression. J Antibiot. 1992;45:1977–1980. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horiguchi M. Occurence, identification and properties of phosphonic and phosphinic acids. In: Hori T, Horiguchi M, Hayashi A, editors. Biochemistry of natural C-P compounds. Shiga, Japan: Japanese Association for Research on the Biochemistry of C-P Compounds; 1984. pp. 24–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iverson W P. Corrosion of iron and formation of iron phosphide by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Nature. 1968;217:1265–1267. doi: 10.1038/2171265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kagami Y, Ratliff M, Surber M, Martinez A, Nunn D N. Type II protein secretion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: genetic suppression of a conditional mutation in the pilin-like component XcpT by the cytoplasmic component XcpR. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:221–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keen N T, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy K E, Thompson G A., Jr Phosphonolipids: localization in surface membranes of Tetrahymena. Science. 1970;168:989–991. doi: 10.1126/science.168.3934.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Zwieb C, Wu C, Adhya S. Bending of DNA by gene-regulatory proteins: construction and use of a DNA bending vector. Gene. 1989;85:15–23. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lauwers A M, Heinen W. Alterations of alkaline phosphatase activity during adaptation of Escherichia coli to phosphite and hypophosphite. Arch Microbiol. 1977;112:103–107. doi: 10.1007/BF00446661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maidak B L, Olsen G J, Larsen N, Overbeek R, McCaughey M J, Woese C R. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:109–111. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malacinski G, Konetzka W A. Bacterial oxidation of orthophosphite. J Bacteriol. 1966;91:578–582. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.2.578-582.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malacinski G M, Konetzka W A. Orthophosphite-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxidoreductase from Pseudomonas fluorescens. J Bacteriol. 1967;93:1906–1910. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.6.1906-1910.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metcalf W W, Jiang W, Daniels L L, Kim S K, Haldimann A, Wanner B L. Conditionally replicative and conjugative plasmids carrying lacZ alpha for cloning, mutagenesis, and allele replacement in bacteria. Plasmid. 1996;35:1–13. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metcalf W W, Wanner B L. Involvement of the Escherichia coli phn (psiD) gene cluster in assimilation of phosphorus in the form of phosphonates, phosphite, Pi esters, and Pi. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:587–600. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.587-600.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Metcalf W W, Wanner B L. Mutational analysis of an Escherichia coli fourteen-gene operon for phosphonate degradation, using TnphoA′ elements. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3430–3442. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3430-3442.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metcalf W W, Zhang J K, Shi X, Wolfe R S. Molecular, genetic, and biochemical characterization of the serC gene of Methanosarcina barkeri Fusaro. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5797–5802. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5797-5802.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller V L, Mekalanos J J. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2575–2583. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2575-2583.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakami T, Anzai H, Imai S, Satoh A, Nagaoka K, Thompson C J. The bialaphos biosynthetic genes of Streptomyces hygroscopicus: molecular cloning and characterization of the gene cluster. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;205:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nunn D, Bergman S, Lory S. Products of three accessory genes, pilB, pilC, and pilD, are required for biogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2911–2919. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2911-2919.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seidel H M, Freeman S, Seto H, Knowles J R. Phosphonate biosynthesis: isolation of the enzyme responsible for the formation of a carbon-phosphorus bond. Nature. 1988;335:457–458. doi: 10.1038/335457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsubota G. Phosphate reduction in the paddy field. I. Soil Plant Food. 1959;5:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wanner B L. Novel regulatory mutants of the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli K-12. J Mol Biol. 1986;191:39–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weimer P J, Van Kavelaar M J, Miller C B, Ng T K. Effect of phosphate on the corrosion of carbon steel and on the composition of corrosion products in two-stage continuous cultures of Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:386–397. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.2.386-396.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]